Home in Cinema and Women at Home (1969–1999)

Introduction

This article focuses on the changes in the cinematic representation of home and how women are represented at home and in relation to home before, during, and after the 1979 Iranian Revolution. Research findings are based on an ethnographic content analysis of thirty post-revolution and thirty pre-revolution films from 1969 to 1999. These films include best-sellers, films made by New Wave filmmakers, films by new revolutionary filmmakers, and films known as Fīlmfārsī. This article illustrates how the cinematic representation of women at home and in relation to home changed by discussing three major themes: the role of class in the representation of women at home, the presence of women in the background and foreground, and women, home, and homeland as objects to be protected. Cinema, as an institution that has a reciprocal relationship with society and state, can demonstrate how changes in society or state are manifested. Also, cinema itself changes as a result of shifts in society and state. I introduce a model to describe this dialectical relationship between the state, cinema, and society based on Griswold’s cultural diamond. The inseparability of social and spatial processes is key in discussing the relationship between home and revolution. Home is constantly in the process of being made, which affects and is affected by social processes.

The relationships between cinema and revolution, and cinema and women, have been discussed in the academic world from different approaches. The question of how the representation of home changes during big social changes, such as revolution, was the starting point of this study. The theme of the representation of women emerged in the early stages of research. Thus, the research scope evolved to foreground analysis of the representation of women at home and how this changed during the revolution. Firstly, this article illustrates the meaning of home. Symbolic interactionists pay attention to the processes of meaning-making and place-making that result in home-making. Therefore, home is a dynamic process, not a static state of being. After discussing home, the relationship between cinema and revolution become the focal point of the discussion.

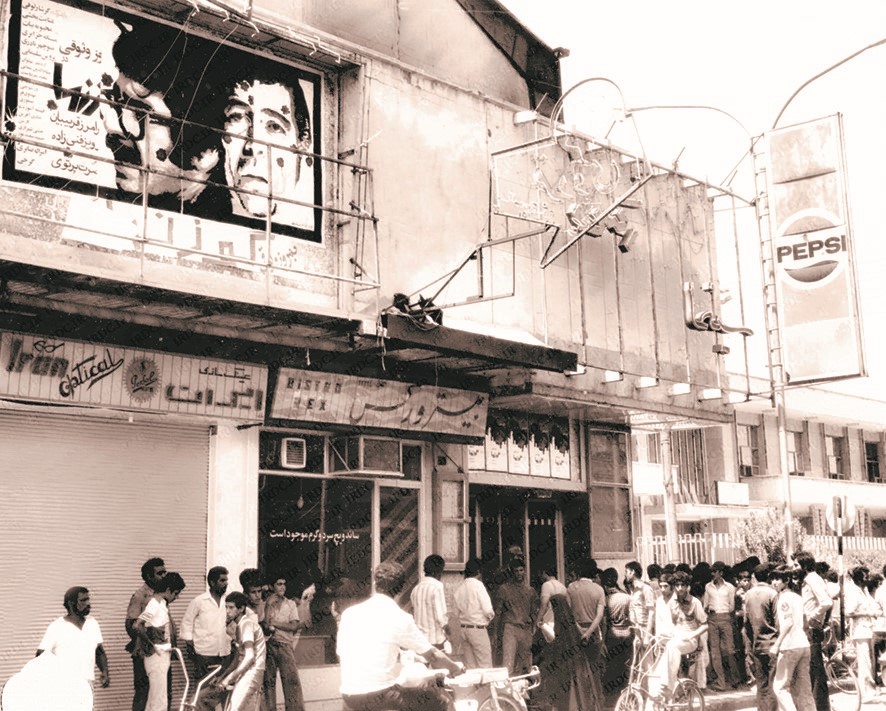

Studying the history of cinema in Russia, Cuba, Algeria, and Iran shows the inseparable connection between cinema and revolutionaries before and after revolutions. In Iran, the Cinema Rex arson triggered the revolution six months before the triumph. This tragedy happened on the twenty-fifth anniversary of the American-British coup while people were watching Gavazn’hā (1974). This film was interpreted in a political way in those days.1This film is about a person, Qudrat, who robs a bank, gets shot, and takes refuge with his old friend, Sayyid, in his old neighbourhood. The popular interpretation of this film is that Ghodrat is a communist guerrilla who fights against the Pahlavi regime and got shot because of it. Mas‛ūd Kīmīyā’ī, the director, claims that a person from SAVAK interfered in the process of producing this film and made them change some scenes, including the final scene, to prevent this political interpretation. Over 377 people died on this day. The revolutionaries blamed the regime and the Intelligence and Security Organization of the Country (SAVAK) for burning the cinema, while the Pahlavi regime blamed the revolutionaries for it. This incident was not the only connection between cinema and revolution in Iran. Khomeini and his supporters considered cinema to be a deceptive medium which corrupts society. He included cinema in his first speech after his return to Iran during the revolution. The extreme supporters of Khomeini lit theaters on fire even after the revolution as they were seen as hubs of depravity. However, some of them became filmmakers in the following years and saw cinema as a revolutionary and educative tool. This research discusses that duality below.

Figure 1: The image of the Cinema Rex with a poster of Gavazn’hā (The Deer, 1974), directed by Mas‛ūd Kīmiyāyī, accessed via https://raseef22.net/english/article/1093599-a-blaze-of-horror-in-iran-the-regions-biggest-act-of-terror-in-the-20th-century.

The development of the male gaze in cinema and its role in Iranian cinema is a key point of this research. Feminist approaches by both male and female filmmakers in Iran influenced the representation of women in Iranian cinema. By using the Ethnographic Content Analysis method in studying sixty films from before and after the revolution, I discuss three major themes regarding the presentation of women at home. I argue that class plays a crucial role in this representation and affects gender roles at home. Then, I investigate the process of representation of women in the foreground and background of films and the changes in their status with respect to hierarchy at home. In the end, I discuss how women and their bodies were represented as objects to be protected by men before and after the revolution. Further, home becomes a place to protect women from the “outside,” which is seen as a masculine space.

What is Home?

Scholars across different disciplines have published copious work on the impact of revolution on society at the macro-level. In this article, I will concentrate more on the changes that revolutions bring to society and everyday life at the micro- and meso-level. As Agnew states, histories of place are the best method for looking at the social bases of response and resistance to institutions, including states.2John Agnew, Place and Politics: The Geographical Mediation of State and Society (Boston: Allen & Unwin, 1987), 1. Scott classifies these resistances and responses in everyday life as “weapons of the weak.”3James C. Scott, Weapons of the Weak (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1985). Home, as a context and also as a site for agential enactment of roles in everyday life, is the core of this discussion. This article explores the concept of home as a place from the symbolic interactionist perspective and bridges theories of home from scholars with different approaches.

Space is not only produced through social relations and structures,4Henri Lefebvre, The Production of Space, trans. Donald Nicholson-Smith (Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 1991). but also affects how social processes work.5Doreen Massey, “Introduction: Geography Matters,” in Geography Matters, eds. Doreen Massey and John Allen (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1984), 1-11. Social processes and space are inseparable. Lefebvre argues that place is where everyday life is situated, and it is not merely an abstract space. It is where we live out basic practices.6Andrew Merrifield, “Place and Space: A Lefebvrian Reconciliation,” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographer 18, no. 4 (1993): 516-531. To illustrate the concept of place, I refer to Gieryn’s work. He sees place as a “space filled up by people, practices, objects, and representations… Everything we study is emplaced.”7Thomas F. Gieryn, “A Space for Place in Sociology,” Annual Review of Sociology 26, no. 1 (2000): 463-496, 466. Geographic location, material form, and invested meaning and value are three elements of recognizing a space as a place. The latter is the key point in my discussions about place and home. Action and intention are the essence of a place,8Edward Relph, Place and Placelessness (Los Angeles: Sage Publications, 1976/2016), 47. and interactions are the roots of the process of meaning-making. The process of meaning-making is crucial in turning a space into the place we call home. The meaning-making process is dynamic, which is linked to the endless place-making process. Therefore, “home is a process rather than a state of things.”9Paolo Boccagni and Margarethe Kusenbach, “For A Comparative Sociology of Home: Relationships, Cultures, Structures,” Current Sociology 68, no.5 (2020): 595-606, 597.

The assigned meaning to a place shapes memory and identity that is connected to that place. It links home and identity.10Lisa-Jo K. van den Scott, “Mundane Technology in non-Western Contexts: Wall-as-Tool,” in Sociology of Home: Belonging, Community and Place in the Canadian Context, eds. Laura Suski, Joey Moore and Gillian Anderson (Toronto: Canadian Scholars Press International, 2016), 33-53. Home is a significant focal point where our thoughts, memories, and dreams get combined.11Gaston Bachelard, The Poetics of Space, trans. M. Jolas. (Boston: Beacon Press, 1969). Our interactions and social life shape these thoughts, memories, and dreams. Cinema comes into this process at a point where it impacts our thoughts, memories, and dreams. We think and dream about what home means to us, in part, through our engagement with cinema. This engagement with cinema impacts our vision and the memories we strive to create at home. As we strive towards this ideal image of home, we are continually making home.12Paolo Boccagni and Margarethe Kusenbach, “For A Comparative Sociology of Home: Relationships, Cultures, Structures,” Current Sociology 68, no.5 (2020): 595-606.

In an ethnography that I did on Boushehri homes, I found that the way people conceptualize of and define home can be extended to a whole neighbourhood or be restricted to a single room or even a rooftop.13Pouya Morshedi, “The Study of Human Communications in Iranian Homes through the Ethnography of the Role of Architecture in Human Communication, A Case Study of Boushehri Homes,” MA Thesis (University of Tehran, 2015). In this research, I argue that the concept of home can be extended to be as large as the homeland. Therefore, references to home in any kind of art, including cinema, could be as small as a room or as big as the homeland. The section on women, home, and homeland further discusses this.

Cinema and Revolution

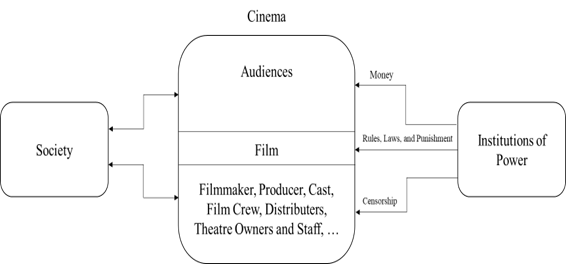

An art world consists of all people who are involved in producing a particular genre of artwork.14Howard S. Becker, Art World (Berkely: University of California Press, 1982). While we see the artist/s in the frontstage, the work is not restricted to the artist. Art is, in fact, a collective action.15Howard S. Becker, “Art as Collective Action.” American Sociological Review 39, no. 6 (December 1974): 767-776. Cinema is not an exemption in this regard. The field of cinema includes filmmakers, actors, actresses, drivers, editors, writers, producers, audiences, and all other people who are involved in producing, screening, and watching a film. To illustrate the relationship between different roles in an art world, Griswold’s cultural diamond is helpful. The cultural diamond has four elements: social world, receiver, creator, and the cultural object itself.16Wendy Griswold, Cultures and Societies in a Changing World (Thousand Oaks: Pine Forge Press, 2004). This diamond helps us to find out how film, filmmakers, audiences, and the social world are connected. We can think about each of these elements in relation to the other elements. However, it is imperative to expand her first element, the social world, to fully discuss how political changes influence the world of cinema. To do so, Huaco’s work on the emergence of cinematic waves in four different countries is useful. Huaco discusses four factors that shape new cinematic waves. He argues that cinematic waves are shaped by a cadre of directors, cameramen, editors, actors, and technicians; the industrial plant required for film production; a mode of the organization of the film industry that is either in harmony with or at least permissive of the ideology of the wave; and finally, a political climate that is either in harmony with or permissive of the ideology and style of the wave.17George A. Huaco, The Sociology of Film Art (New York: Basic Books, 1965), 212. A model that weaves together Griswold and Huaco’s ideas is ideal to account for the last factor, the political climate, in analyzing the way films represent home in the pre- and post-revolutionary eras.

Figure 2: A Model for the Relationship Between Cinema, Society, and Institutions of Power

The role of institutions of power in the field of cinema makes cinema suspect as a tool for domination. In the hands of a state, cinema has the potential to be a tool for dominating, standardizing, and homogenizing societies. The state, through cinema, can then play a powerful role in what Adorno and Horkheimer call the culture industry.18Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer, Dialectic of Enlightenment, eds. Gunzelin Schmid Noerr, trans. Edmund Jephcott (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1944/2007). However, this is not the only way that cinema can influence society. Benjamin discusses the development of methods of artistic reproduction, and claims that technological reproduction is more independent than manual reproduction and can create simulacra that take on a new significance beyond the original work of art.19Walter Benjamin, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.” in Walter Benjamin; Selected Writing 1935-1938, eds. Howard Eiland and Michael W. Jennings, trans. Edmund Jephcott, Howard Eiland and Others (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2002), 99-252. He argues that establishing “equilibrium between the human being and the apparatus” is the most important social function of film. Film not only represents human beings, but also their environment and hidden aspects of familiar objects.20Walter Benjamin, Art in A Technological Age (London: Penguin,1935/2008), 17. It provides the potential to influence society in ways other than standardizing and homogenizing. Indeed, Hansen and Dimendberg find this aspect of film as much cognitive and pedagogical as it is remedial and therapeutic.21Miriam Hansen and Edward Dimendberg, Cinema and Experience: Siegfried Kracauer, Walter Benjamin, and Theodor W. Adorno (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012), 79.

This approach views cinema as having the potential to be a revolutionary field, rather than a manipulative and deceptive tool. The emergence of revolutionary cinema is intertwined with the concept of national cinema. Croft argues that diverse traditions of national cinema identify themselves mostly by determining their relationship with Hollywood. He names seven categories of cinema. First, cinema that differs from Hollywood without any direct competition. Second, cinema that differs from Hollywood and critiques it. Third, European and third-world cinema that struggles against Hollywood without success. Fourth, cinema that ignores Hollywood and is successful in this matter. Fifth, Anglophone cinema that tries to beat Hollywood at its own game. Sixth, state-controlled and state-subsidized cinema. Seventh, regional/national cinema that keep their distance from the nation-state context.22Stephen Croft, “Reconceptualising National Cinema/s,” in Theorising National Cinema, eds. Valentina Vitali and Paul Willemen (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006), 44-58. Each national cinema may fit into one or more of the categories Croft names. In countries that have undergone or are currently experiencing revolutions, the relationship between cinema and Hollywood, and cinema and the state are important in shaping national cinema. This article discusses two examples connected to the case of Iran below.

In the Cuban context, the Cuban Institute of Cinematographic Art and Industry was established less than three months after the 1959 revolution. This demonstrates how the new Cuban regime saw cinema as a revolutionary field. The emergence of Third Cinema in South America influenced Cuban cinema as well. Espinosa introduces the concept of “imperfect cinema,” in which the content takes over the aesthetics.23Julio García Espinosa, “For an Imperfect Cinema,” in Film Manifestos and Global Cinema Cultures, ed. Scott MacKenzie (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1969/2014), 220-229. The new Cuban cinema became a response to the dominance of Hollywood, while it was also a response to the need for commercial cinema. Russia (and later the Soviet Union) had a different story. Russian cinema had a rich history before the revolution. Cuba did not have such a history in cinema before the revolution. The hegemonic role of the United States in cinema in 1917 was not the same as what it had become by 1959. Therefore, post-revolutionary Soviet cinema was confronting and rejecting pre-revolutionary aesthetics more than the hegemony of Hollywood.

Post-revolutionary cinema in Iran was a response to both of the issues Cuban and Russian films faced: responding to Hollywood and rejecting the cinematic aesthetic from before the revolution. However, rejecting pre-revolutionary aesthetics was the primary target. To illustrate the new regime’s perspective on cinema in Iran, we can take a look at what Khomeini, the first leader of the Islamic Republic, said about cinema in his first speech after coming back from exile: “Our cinema is a hub for depravity… We are not against cinema, but we are against depravity… Cinema is a symbol of civilization that must be at the people’s service, at the service of the cultivation of the people…”24Ruhollah Khomeini, Sahīfah-i Imām (Tehran: The Institute for the Compilation and Publication of the Works of Imam Khomeini, 1979/1999), 6: 15. [Translated by the author.]

This quote demonstrates that the perceived deception and corruption of pre-revolutionary cinema were salient qualities to be excised from cinema for the new regime leaders. However, Khomeini’s view of cinema as a symbol of cultivation shows that there is a different kind of cinema that would be acceptable under the new regime. Cinema which is “at the service of the cultivation of the people” would be considered “good cinema.” This implies that the regime leaders ought to promote cinema that embodies a new post-regime narrative of the world and a revolutionary aesthetic. It turns cinema into a tool for the state under the guise of service to the people.

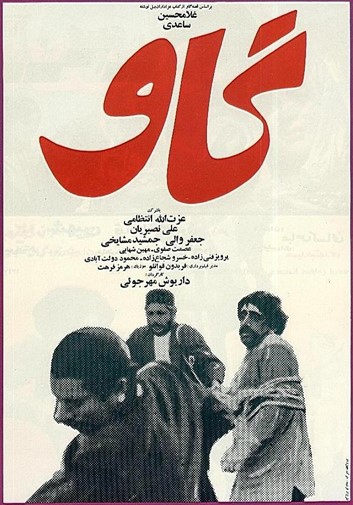

Pre-revolutionary filmmakers, movie-goers, and other groups involved in the field of cinema lost hope for the future of cinema in the post-revolutionary era.25Parviz Jahed, “Kārnāmah-yi 35 Sāl Sīnimā-yi Inqilāb,” BBC Persian. February 5, 2014. retrieved 28/11/2023, https://www.bbc.com/persian/iran/2014/02/140130_l44_cinema_35th_anniversary_iranian_revolution There was no guideline and little description of the “good cinema” which Khomeini and new people in power had in mind. Later, Khomeini mentioned that Gāv (The Cow) was an educative film.26Ruhollah Khomeini, Sahīfah-i Imām (Tehran: The Institute for the Compilation and Publication of the Works of Imam Khomeini, 1980/1999) 12: 292. The Cow was a film by Dāryūsh Mirhjū’ī, a New Wave filmmaker, based on a story by Ghulāmhusayn Sā‛idī, a Marxist writer who had left the country after the revolution. Filmmakers took this as a sign to start again. New Wave filmmakers, such as Bayzā’ī, Taghvā’ī, and others, started to work again. The new social and political atmosphere shaped new rules, laws, and restrictions for filmmakers. Women, their presence, their bodies, and their interactions in cinema were the target of most of these new rules, restrictions, and censorship.

Figure 3: Poster for the film Gāv (The Cow, 1969), directed by Dāryūsh Mihrjū’ī.

Women, Cinema, and Iranian Cinema

When discussing the relationship between the representation of home in cinema and big social changes, gender roles and interactions between people at home arrests our attention. Women and their roles, interactions, presence, and absence play a crucial role in representing the home and are crucial for understanding the social changes caused by the revolution. Women, as objects of spectacle in cinema, have been discussed in many feminist scholars’ work directly and indirectly.27See, for example, Laura Mulvey, “Afterthoughts on ‘Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema’ inspired by King Vidor’s Duel in the Sun (1946),” in Visual and Other Pleasures. Language, Discourse, Society (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1989), 29-38; Teresa De Lauretis, Alice Doesn’t (Bloomington: Indiana Press University, 1984); and Ann Kaplan, Women and Film (London: Taylor & Francis, 2002). However, this conversation is not restricted to feminist theorists of cinema. While Blumer focuses on movie-goers and their reactions to motion pictures,28Herbert Blumer, Movies and Conduct (New York: Macmillan, 1933). his data, while it is not from a feminist theoretical approach, discusses women as being objects of spectacle in cinema.29Patricia T. Clough, “The Movies and Social Observation: Reading Blumer’s Movies and Conduct,” Symbolic Interaction 11, no. 1 (1988): 85-97. Blumer and Clough both discuss cinema as a male-dominated field. Johnston claims that women are presented as what they “represent for man” in a sexist ideology and a male-dominated cinema.30Claire Johnston, “Women’s Cinema as Counter-Cinema,” in Feminist Film Theory: A Reader, ed. Sue Thornham (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1999), 31-40, 34. In all cases, scholars have recognized that cinema has focused on men as agents over time and across different places. Even today, a woman is often not present in a film as a woman, but as an accessory to a man and to how men are represented in cinema. This situation extends from a sexist ideology that puts women as secondary in the gender hierarchy. The concept of the cinematic gaze offers insight into how cinema shapes and orders gendered positions and hierarchy.

Social and cultural context shapes our vision.31Eviatar Zerubavel, Social Mindscapes; An Invitation to Cognitive Sociology (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1997). We are socialized not only in terms of what to attend to, but also how to interpret what we see. Therefore, vision is a “skilled cultural practice.”32Chris Jenks, “The Centrality of the Eye in Western Culture: An Introduction,” in Visual Culture, ed. Chris Jenks (London: Routledge, 1995), 1-25, 10. The gaze as a function of vision follows the same rule. Urry and Larsen define the gaze as “a performance that orders, shapes, and classifies, rather than reflects the world.”33John Urry and Jonas Larsen, The Tourist Gaze 3.0 (Los Angeles: Sage Publications, 2011), 2. While they use this definition to introduce the concept of the tourist gaze, it also helps to expand the concept of the cinematic gaze. The cinematic gaze has been discussed mostly in Lacanian scholars’ work.34See, e.g., Clifford T. Manlove, “‘Visual “Drive’ and Cinematic Narrative: Reading Gaze Theory in Lacan, Hitchcock, and Mulvey,” Cinema Journal 46, no. 3 (2007): 83-108; Todd McGowan, “Looking for the Gaze: Lacanian Film Theory and Its Vicissitudes,” Cinema Journal 42, no. 3 (2003): 27-47. Mulvey explains the cinematic gaze as a male gaze upon females. According to Mulvey, “Playing on the tension between film as controlling the dimension of time (editing, narrative) and film as controlling the dimension of space (changes in distance, editing), cinematic codes create a gaze, a world, and an object, thereby producing an illusion cut to the measure of desire.”35Laura Mulvey, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” Screen 16, no. 3 (1975): 6-18, 17. She argues that women are presented as passive objects of desire for men not only in the story, but also in how the audience is conceptualized, targeted, and treated. Mulvey has concentrated both on the content of films, such as when she wrote “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema” (1975), and the audience, particularly women and their approach to film and the way they watch and interpret film.36Mulvey, “Afterthoughts on ‘Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema’ inspired by King Vidor’s Duel in the Sun (1946),” 29-38 While I agree with her approach, I argue that the cinematic gaze is not restricted to a gendered gaze. It also shapes, orders, and classifies the world regarding the race, ethnicity, class, and other sociological locations of human beings. Further, this research study suggests that the social class of women in their cinematic roles is an important component of the cinematic gaze.

There are several groups engaged in shaping the cinematic gaze: filmmakers, producers, artists, institutions of power that fund, censor, control, and distribute films, and society. We can think back to Griswold’s cultural diamond and the expanded role of the state as part of the element of the social world. Power relations are a key factor that privilege certain social roles as more influential in shaping the cinematic gaze. Here, big social changes, including revolutions, become more important to discuss because new regimes that result from revolutions can play a role in shaping the cinematic gaze through their tools of power. However, all these factors do not mean that audiences are passive in the field of cinema. They interpret what they see, hear, and experience, albeit through the lens of their socialization. As Rancière argues, artists construct their stages to exhibit their artwork, but the effect of their art cannot be anticipated.37Jacques Rancière, The Emancipated Spectator, trans. Gregory Elliott (London: Verso, 2009). Representation entails audiences who are active interpreters and who develop their own translation of the story to make it their own. This may be underestimated by those who use cinema as a tool for domination. While the cinematic gaze shapes, orders, and classifies the world in a film, the interpretation of the audiences affects the resulting vision.

Women in Iranian cinema were not exceptions and have been the object of the male gaze. They have been portrayed in a way that fits within the patriarchal order of Iranian society. There are many scholarly works on how women were presented in Iranian cinema before and after the Revolution. Naficy categorizes women’s roles in pre-revolutionary cinema into nine categories. First, woman as an attractive and termagant being. This woman is usually a dancer, prostitute, or cabaret singer who is sexually alluring. Second, woman as an ethereal being who is unattainable. Third, woman as a mother/angel who sacrifices for everyone. Fourth, woman as a sister who is chaste and virtuous, and who is protected by the men of the family. Fifth, woman as a rural naïve person who has been deceived in town and becomes a dancer/singer/prostitute who will be “redeemed” by a man. Sixth, woman as sexual object and fetish. Seventh, woman as a seductive being who deceives men. Eighth, woman as a witness who is beside a man. Ninth, woman as an independent being who is working in a position which is not a dancer, singer, or prostitute.38Hamid Naficy, “Zan va Mas’alah-yi Zan dar Sīnimā-yi Irān-i Ba‘d az Inqilāb,” Nīmah-yi Dīgar 14, (1991): 123-169. Derayeh categorizes women in pre-revolutionary cinema as positioned in one of two main ethical categories; ma‛sūm (naïve/innocent) and fāsid or gumrāh (corrupted or misguided).39Minoo Derayeh, “Depiction of Women in Iranian Cinema, 1970s to Present,” Women’s Studies International Forum 33, (2010): 151-158, 152. Similarly, Ghorbankarimi asserts that to be a good woman in the first decade of post-revolutionary films, women should be pure, chaste, and untouched. The good woman is the one whom a man will protect.40Maryam Ghorbankarimi, A Colourful Presence: The Evolution of Women’s Representation in Iranian Cinema (Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2015), 192. The more women are portrayed spending their time at home and being restricted to the home, the more positive they are from the patriarchal perspective. Cinema contributes to ordering a world where the home (inside) is where women belong, while outside is a masculine space which is dangerous, deceptive, and corruptive for women. The only way to survive outside the home is for a man to protect and save the woman. I argue that keeping women at home in cinema perpetuates the idea of women as pure, chaste (because they are restricted), and untouched (because strangers are not there).

After the 1979 Revolution, the new regime had a paradoxical perspective toward cinema. On the one hand, cinema was a Western weapon to deceive people and assimilate them. On the other hand, it was an educational medium for “cultivation.” The new regime decided to choose the latter perspective and made cinema “the main art of the new political project.”41Sara Saljoughi, “Seeing, Iranian Style: Women and Collective Vision in Abbas Kiarostami’s Shirin,” Iranian Studies 45, no. 4 (July 2012): 529-535, 522. Women, their images, and their presence were key points in the new regime’s perspective and their goals with cinema. For the post-revolutionary leaders, women were directly related to depravity and corruption in pre-revolutionary cinema. Therefore, cleansing cinema and purifying this medium was intertwined with reimaging women in cinema.

There were different strategies to do this. In the first years of the new regime and during the Iran-Iraq war, women were mostly invisible and absent. Later, women were portrayed, but only as a background for the real story. By the end of the 1980s, women started to be present in the foreground.42See Hamid Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema, vol. 4. (Durham: Duke University Press, 2012); Derayeh, “Depiction of Women in Iranian Cinema, 1970s to Present,” 151-158. Despite new rules and laws restricting women more and more in cinema, women gradually found a space to be more present at the same time. The presence of women as directors, first-role actresses, and producers became possible as long as they were following the Islamic codes of modesty.43Hamid Naficy, “Veiled Voice and Vision in Iranian Cinema: The Evolution of Rakhshan Banietemad’s,” Social Research 67, no. 2 (2000): 559-576. This new presence was not an immediate consequence of the post-revolutionary changes, rather, it was the result of the resistance strategies that women agentically chose in this restrictive situation in cinema and society.

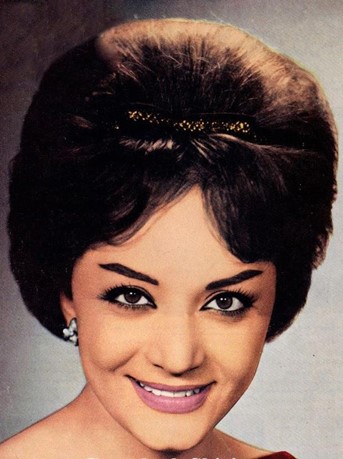

The emergence of female filmmakers influenced the cinematic gaze and its masculine nature. We cannot name many women who made films before the revolution. Shahla Riahi was the first woman who directed a film in 1956. Furūgh Farukhzād made a documentary, In Khanah Sīyāh ast, in 1962 and Shahrzād (Kubrā Sa‛īdī) directed Maryam va Mānī in 1978. They were the only women who directed films in Iran before the revolution. After the revolution, we see more women’s names on screen as the director, such as Rakhshān Banī-i‛timād, Pūrān Dirakhshandah, and Manīzhah Hikmat. This brought women in primary roles to the foreground more and more. Women became the agentic subjects in more stories rather than being represented in relation to other men. This not only happened in women-made films, but also in male-made films in the late 1980s and early 1990s. This change brought women more to the centre, however, patriarchy and the Islamic codes of modesty maintained the dominance of the male gaze in the field of cinema. Women, their presence, and their interactions are still targets of censorship. The new regime wanted the film industry to represent a purified Shiite world.44Negar Mottahedeh, Displaced Allegories: Post-Revolutionary Iranian Cinema (Duke University Press, 2008). They attempted a cleansing process to shift cinema from a site of the profane to the sacred.45Emile Durkheim, The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life, trans. Karen Elise Fields (New York; Toronto: Free Press, 1912/1995). Therefore, codes of modesty that women had to follow in public spaces influenced the image of women in private spaces, which impacted the representation of home and the representation of women at home. The next section explains the research conducted to address the changes in the representation of home and women at home in Iranian cinema.

Figure 4: Shahlā Riyāhī (1926-2019), the first Iranian woman who directed a feature film.

Methodology

This research primarily focuses on the changes in cinematic representation of home and of women at home before and after the 1979 Revolution in Iran. Sociological qualitative research centres the researcher in the process. Throughout the methods section, the first person indicates this centred approach and the reflexivity that is part and parcel of this research. It is important to acknowledge the role of the researcher in the process, and to recognize that different researchers will find various aspects of polysemic meanings. To do so, I conducted a content analysis of sixty Iranian films produced between 1969 and 1999. I chose thirty films from the pre-revolutionary era (1969-1979) and thirty films from the post-revolutionary era (1979-1999). The transition from the previous regime to the new regime did not happen immediately. During the transition time, the number of films that were produced decreased. Also, the Iran-Iraq war was going on between 1980 and 1988. The war influenced all political, economic, social, and cultural aspects of Iranian society. Iranian cinema was not an exemption. Given these historical circumstances, I decided to study two decades of Iranian cinema after the revolution to include films that were produced during a more stable period in post-revolutionary Iran.

Film selection criteria included best-sellers, films made by new revolutionary filmmakers, New Wave films, films made by women, films about different historical eras, and films known as Fīlmfārsī. The diversity in genres, filmmakers, and content allowed for the analysis of the representation of home and women at home from different perspectives. To do so, I chose the Ethnographic Content Analysis (ECA) approach to analyze the chosen films. While this approach is very close to what we know as qualitative content analysis, Altheide and Schneider make this approach different by emphasizing “the description of people and their culture” in the process of ECA, privileging an inductive approach.46David L. Altheide and Christopher J. Schneider, Qualitative Media Analysis, 2nd. ed. (Los Angeles: SAGE, 2013), 24.

At the level of analyzing the data, ”symbolic interactionists often rely on grounded theory when they do ethnography.”47Lisa-Jo. K. van den Scott, “Symbolic Interactionism,” in SAGE Research Methods Foundations, eds. Paul Atkinson, Sara Delamont, Alexandru Cernat, Joseph W. Sakshaug and Richard A. Williams (Sage Publications, 2019), 6. In the first phase, I watched films, took notes, and looked for patterns in dialogue, interactions, and frames in the films. I developed codes from these themes. I applied an inductive approach while coding. This allows the researcher to be systematic and flexible, while avoiding a reductionist approach.,48Margrit Schreier, “Qualitative Content Analysis,” in The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Data Analysis, ed. Uwe Flick (London: Sage Publication, 2013), 170-183. In the second phase, I shaped my preliminary themes based on the codes that inductively emerged in the previous phase. In the last phase, I identified major themes which will be discussed in the next section.

Emergent Themes: Women at Home, Home in Cinema

Three major themes emerged around women and home in this research. These show the representation of home and representation of the relationship between home and women in cinema before and after the 1979 Revolution. The emergent themes below are depictions of social class and women at home; the shift of women from the background to the foreground; and how the protection of women stands in for and expands to the protection of the homeland.

Poor Women vs. Rich Women: The Role of Class in the Representation of Women at Home

The importance of the intersection of gender and class emerged immediately in the data both in pre-and post-revolutionary films. While intersectionality describes how our gender and class (and other aspects of our social location, such as race, ethnicity, dis/ability, etc.) impact our status in social hierarchies, this analysis focuses on how gender and class specifically impact the representation of people in films.

In pre-revolutionary films, most of the women from the upper class do not work at home. They usually have servants who will take care of housework. For example, in Rizā Muturī (1970), we see women at a rich girl’s house who do nothing. They are sitting on fancy couches, resting in open areas of the house, and chatting. They have the privilege of having leisure time and performing their class by showing off their leisure and doing nothing at home. They do not have a significant role at home or in other spaces, which makes them somewhat ornamental or decorative at times. However, there are films that represent higher-class women who have jobs or work outside of home. They usually play roles such as artist (not mutrib),49Mutrib is a word that has been used to downgrade the status a musician. This word does not have a bad meaning itself, but people use it to mention a low-brow musician in contrast with a high-brow musician who is an artist. writer, or poet. We can find the role of Parvānah in Dar Imtidād-i Shab (1978) in pre-revolutionary films and the role of Bānū in Bānū (1992) in post-revolutionary films. In post-revolutionary films, one sees women more often as writers and poets rather than artists (specifically as singers).

In pre-revolutionary films, lower-class women always do the housework. They take care of all the chores inside the home. However, due to their economic status, some of them work outside. Usually, the jobs they take are related to doing housework at others’ homes, and if they are young attractive women, they may work as a dancer, a singer, or an actress at a club. The difference between these two kinds of depictions of lower-class women’s roles is that the latter usually turns out to be a deviant woman or a deceived woman. In post-revolutionary films, we see more of the first type of lower-class women who perform so-called “respectable” work outside the home. The lower-class women are condemned to housework.

Figure 5: The representation of lower-class (left; 00:52:58) and upper class (right; 00:27:15) women in Rizā Muturī (Reza, the Motorcyclist, 1970), directed by Mas‛ūd Kīmiyāyī.

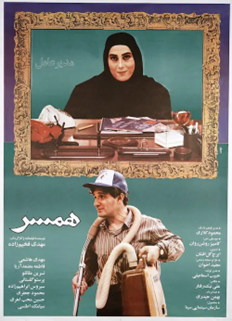

Middle-class women have been pictured in more diverse ways at home. In early pre-revolutionary films, we cannot find middle-class families in films. By the last decade of the Pahlavi regime, we can see narratives of middle-class families in films by the younger generation of filmmakers. This follows from the changes in Iranian society, the rise of oil money, and the birth of new, middle-class, urban families. In post-revolutionary films, middle-class women fall into two main categories regarding their activities at home. The first one is the middle-class woman who works outside in a mid-range job and has a servant or servants at home. We can find an example of this group in Ārāmish dar Huzūr-i Dīgarān (1972). Here, the characters Malīhah and Mahlaqā work at a hospital as nurses while a servant takes care of the chores at home. We can find the second model of the middle-class woman in Guzārish (1977), where a middle-class woman, A‛zam, still does the housework and takes care of the child. She may complain about her husband’s lack of responsibility for housework and childcare, but she remains responsible for them. In post-revolutionary films, we see more and more middle-class women who may or may not work outside. However, we still find them primarily as the person responsible for housework and childcare. The new regime’s perspective on women as mothers and caregivers exacerbated these roles for middle-class women in cinema. For example, in Hamsar (1994), we see how Shīrīn, the woman, is in charge of housework even while she works at the company where her husband works. When the man, Riza, stays at home in protest of his wife’s promotion to the CEO position, he performs housework, but it is represented as an unusual responsibility that affects his manliness. This is even illustrated in the film poster (see figure 6). Housework and childcare are not included in the gender role that a man takes at home. In Khāharān-i Gharīb (1996), man and woman are separated, and each took one of the twins. The man has his mother by his side to take care of the home and the child, while the woman takes on the responsibility herself and remains alone at home caring for her child. Women are expected to do the “second shift” assuming responsibility for all unpaid domestic labor.50Arlie Russell Hochschild and Anne Machung, The Second Shift: Working Parents and the Revolution at Home (New York: Penguin Books, 2012). While we can find this second shift in lower-class families in pre- and post-revolutionary films, the representation of middle-class families and working women made women’s second shift and their double burden bolder in later cinema.

Figure 6: Poster for the film Hamsar (The Spouse, 1994), directed by Mahdī Fakhīmzādah.

Women’s gender role at home and their presence and absence in the job market is not the only manifestation of the intersectionality of gender and class in Iranian cinema. The relation between the hijab and class is another important factor in the representation of women at home. The hijab is intertwined with lower-class lifestyle in both eras. While we can find non-hijab-wearing lower-class women in pre-revolutionary films, it is restricted to women who were considered deviant or deceived by men and who are mostly shown working at cabarets or brothels. It does not matter if the film is about the current (Pahlavi) era or the past (Qājār) era, in either case, lower-class women wear a hijab while middle-class and higher-class women are much less likely to be presented in a hijab. The film Bābā Shamal (1971) is a good example. After the revolution, filmmakers could not show women without a hijab anymore. Still, higher-class women and intellectuals—portrayed as Westernized people—wear a loose scarf in comparison with lower-class women who clearly wear a scarf as a hijab or wear a chador. In post-revolutionary films, particularly in the first two decades, a woman’s hijab instantly communicated to the audience whether she was an outsider or an insider to the dominant discourse of the Islamic Republic. Intellectuals, and Westernized, urban, and rich people, by wearing a relaxed, loose scarf as a hijab are portrayed as outsiders of the regime’s discourse, while lower-class, poor, rural, and religious people are identifiable as insiders by wearing more formal hijab. If we see anyone without a hijab in post-revolutionary cinema of this period, it is a sign that she is a non-Iranian actress, such as we see, for example, in Az Karkhah tā Rāyn (From Karkheh to Rhine, 1992) (see figure 7). There is no place for women without hijab in the definition of being Iranian under the new regime’s discourse.

Figure 7: Iranian and non-Iranian actresses. Az Karkhah tā Rāyn (From Karkheh to Rhine, 1992), Ibrāhīm Hātamīkīyā, accessed via https://www.aparat.com/v/f6570w6 (00:36:56)

Women at Home: From Background to Foreground

The presence of women on the silver screen and their roles in the stories that films narrate changed during both the pre-revolutionary and post-revolutionary periods examined. Both periods had a similar starting point, although post-revolutionary cinema was established based on a history of women’s presence in pre-revolutionary cinema. In both periods, women were portrayed in the background of the stories and played the role of accessory in each scene to make it believable. I call this the first phase. In the second phase, women gained more influential roles in the story, however, they were still depicted as dependent on the man who was the lead character. A woman could be mother, wife, sister, mistress, fiancée, or a love who helps the hero, or fights against him, to advance the story. The third phase was the period when women became the starring roles of the films and the stories were shaped around them.

In the first phase, women did not have a significant role in narrating or even portraying the story. They mostly played a type-role rather than a named or relevant character. In pre-revolutionary cinema, a strong patriarchal culture influenced the traditional perspective towards women. However, in post-revolutionary cinema, the second phase of the portrayal of women was more influenced by the new regime’s discourse and the influence of their interpretation of Islamic laws where women had no agentic role in public space and society. Most of the new revolutionary filmmakers’ films, such as Tubah-yi Nasūh (1982), and most of the films in the Holy Defence genre (related to the Iran-Iraq war in the 1980s), such as Uqāb’hā (1984) and Kānī-Māngā (1987), were produced in this era. In the second phase, women perform complementary roles in films. Most of the pre-revolutionary films included here belong to this phase. Qaysar (1969), Ragbār (1972), and Būy-i Gandum (1977) are some of the many examples these films. Later, in post-revolutionary films, we have a transition from phase two to phase three. While women in many films such as Ādam Barfī (1994) or Mard-i ‛Avazī (1999) could belong to phase two, we can also start to find women in films such as Khāharān-i Gharīb (1994) and ‛Arūs (1990) in between phase two and three. Women play a more important role but are still adjunct to a man in the whole story.

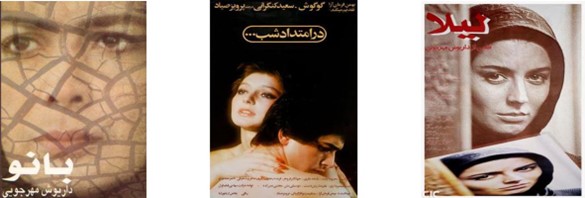

The image of the independent woman takes form in the last years of the Pahlavi regime, but it faded out after the revolution and then gradually faded back in by the end of the first decade of the Islamic Republic. The role of Parvānah in Dar Imtidād-i Shab (1978), in pre-revolutionary cinema, and later Bānū in Bānū (1992), and Laylā in Laylā (1997) are examples of the presence of women in the foreground in the third phase. After the reform era (1997-2005), we can see more women in the center of the story in Iranian cinema. Future research should examine how this continued to develop once film production moved beyond the immediate shadow of the revolution.

Figure 8 (from left to right): Film Posters for Bānū (The Lady, 1992), Dar Imtidād-i Shab (Along the Night, 1978), and Laylā (Leila, 1997).

The representation of women at home developed over time, through these three phases, and yet there are nuances that cannot be captured entirely by conceptualizing the progression of women in film in this way. The more central a woman’s role became (i.e., phase three), the more we would see her with a higher status at home, including challenging the patriarchal structure. However, women are not the head of their household in most of the films in both pre- and post-revolutionary cinema, similar to Iranian society between 1969 and 1999. Women would only be portrayed as the head of the household if they were single moms, grandmothers in the absence of grandfathers, or in comedy films. The latter perpetuates a comedic trope which frames women as cruel, irrational, and as bullies at home. This was a pattern in Iranian cinema. In Rūz-i Bā-shukūh (1989), the mayor tells his wife: “It is not home. You cannot do whatever you want.”51Rūz-i Bā-shukhūh, directed by Kīyānūsh ‛Ayyārī (Hidāyat Fīlm, 1988), 00:35:57 – 00:36:00. The duality between home and workspace becomes a duality between women’s power and men’s power in these kinds of films. Still, workspace is considered a masculine space versus home as a feminine one.

Protection by Men and From Men: Home, Homeland, and Woman

The image of the “good woman,” as discussed above, is a chaste and untouched woman. She should be protected by a man who is a father, brother, husband, son, or a faithful lover. Ghorbankarimi claims that women in pre-revolutionary films are defined by their relationships to these male figures.52Maryam Ghorbankarimi, A Colourful Presence: The Evolution of Women’s Representation in Iranian Cinema (Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2015). It is evident that this representation of women continued after the revolution. Films that belong to the third phase described above are the only cases in the data where women are women without being connected to a man. This shows that in most films women are “someone” to be protected by men. Here, the concept of nāmūs in Iranian culture is useful. Nāmūs is a kind of a male honor that is mostly connected to the women of a man’s family.53Sivan Balslev, Iranian Masculinities: Gender and Sexuality in Late Qajar and Early Pahlavi Iran (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2019). Iranian culture also treats the homeland (vatan) as a part of one’s nāmūs. Man is in charge of protecting his nāmūs. The target of this protection is home, homeland, and women’s bodies. It makes women at home and people from the homeland a symbol of one’s nāmūs. In Ādam Barfī (1994), Isī Khān says: “Turks did not hit you. They hit an Iranian. One of my compatriots. Do you know what it means? It is like someone hit your nāmūs and you say nothing.”54Ādam Barfī, directed by Dāvūd Mīr-Bāqirī (The Artistic Sect of the Islamic Republic, 1995), 00:31:13 – 00:31:17. [Translated by the author.] The process of protecting women is not restricted to the story that a film narrates. The representation of women’s bodies, specifically in sexual scenes, was intertwined with covering bodies and avoiding nudity. This practice did not start with the revolutionary regime.55Ziba Mir-Hosseini, “Negotiating the Forbidden: On Women and Sexual Love in Iranian Cinema,” Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East 27, no. 3 (2007): 673-79. [56] See Negar Mottahedeh, “Iranian Cinema in the Twentieth Century: A Senso This approach, however, changed in the last decade of the Pahlavi regime. The influence of non-Iranian cinema, the image of modern woman, sexual liberation movements around the world, and the changing position of women as a more sexual object in films under the male gaze brought more nudity to Iranian cinema. Dar Imtidād-i Shab (1978) and Shāzdah Ihtijāb (1974) present some examples of this kind of nudity which became one of the main complaints of the new regime about pre-revolutionary cinema. Nudity and exposing women’s bodies was a symbol of depravity and corruption for the Islamic Republic. In both regimes’ perspective, woman’s body was a sexual object that either had to be exposed and perform sexually or had to be covered and protected. This perspective became the major approach of the decision-makers in post-revolutionary cinema in Iran.

The woman’s body had to be protected by a man in the story of the film and from other men who may gaze upon or attack her body. The body and hair should also be protected from male spectators watching the film. This set of practices brought a new representation of women in private spaces, including their own home. Presenting women with a hijab in private spaces became a norm in post-revolutionary films.56See Negar Mottahedeh, “Iranian Cinema in the Twentieth Century: A Sensory History,” Iranian Studies 42, no. 4 (2009): 529-548, and Maryam Ghorbankarimi, A Colourful Presence: The Evolution of Women’s Representation in Iranian Cinema (Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2015). The image of women in private spaces such as a bedroom was eliminated and even if there was a scene about their presence in the bedroom, it would be dark, vague, and blurred (see figure 9).

Figure 9 (from right to left): The Representation of Women in Bedrooms in Laylā (Leila, 1997), directed by Dāryūsh Mihrjū’ī (00:45:52). Mardī Az Junūb-i Shahr (A Man from the South of the City, 1970), directed by Sābir Rahbar (01:11:03).

In the scene from Laylā (1997), we can barely see the woman and space around her. The bedroom became a mysterious space where nothing could be seen vividly. On the other hand, in Mardī Az Junūb-i Shahr (1970), you find the woman in her bedroom with full lighting and even some nudity. The censorship restrictions after the revolution and their focus on women’s bodies and hijabs encouraged filmmakers to represent women in bedrooms in the way we see in Laylā. Women were to be covered and thus “more protected.”

Conclusion

The representation of home in cinema has an unbreakable connection with the representation of women. The gender roles assigned to women and the division of labor that we experienced through the centuries made this connection stronger. However, resistance against these socially constructed gender roles, changes in them, and changes in society influenced the cinematic representation of women at home. This article discussed how these relationships both changed and remained the same in the cinematic representation of women at home as the result of the 1979 Revolution in Iran. This study shows that the revolution influenced these changes, however, they did not happen necessarily in the way expected by the authorities. Some of the changes followed the ideology of the new regime, and some emerged as resistance to that ideology and brought different perspectives to women’s representation at home and outside the home.

Regarding women and their representation in cinema, Naficy argues that the leaders of the Islamic Republic, specifically Khomeini, saw Iranian cinema and its influences on society from the Injection Theory approach. In this view, a film could send a message that would affect the audience directly.57Naficy, “Veiled Voice and Vision in Iranian Cinema: The Evolution of Rakhshan Banietemad’s,” 559-576, 560. Women and their “non-Islamic” representation in cinema could deceive and corrupt society, specifically men. He also believes that by relying on the Realist Illusionist theory, which claims a direct relationship between reality and its representation, the new regime cleansed post-revolutionary Iranian cinema to make the illusion of Islamic modesty the reality. This approach to cinema made women, their bodies, their interactions, and their presence the target of the cleansing process. The new regime’s laws made filmmakers portray the image of women in a way that they could show on the silver screen. Also, they had to manage the interactions between family members, neighbours, and friends to follow the modesty laws that were established by the regime. The main targets of these changes were women, as they were the first to be suspected of depraved and deviant influence. Filmmakers covered women in hijab even when they were at home and in their bedrooms, refrained from showing physical contact between women and men, including any male member of the family (such as father, brother, son, or husband), and made them body-less human beings while their bodies were the target of the male gaze and censorship. The representation of a woman’s body shifted from an exposed sexual object of the gaze to an object to hide and cover. Now, the home was not a private space for women anymore, but it was the extension of the public space where women had to follow the Islamic modesty laws, specifically in covering their bodies.

Cite this article

This article investigates the cinematic portrayal of home and women’s roles within it in Iranian films from 1969 to 1999. Using ethnographic content analysis of 60 films, it examines how sociopolitical changes surrounding the 1979 Iranian Revolution shaped gender dynamics and class structures in domestic spaces. The study identifies three key themes: class-based variations in gender roles, the increasing prominence of women as active subjects in film narratives, and the symbolic connection of women with home and homeland. Drawing on feminist film theory, the article reveals how cinema both perpetuated and resisted patriarchal ideologies, offering a nuanced perspective on women’s evolving representation in pre- and post-revolutionary Iranian society.