Bahram Beyzaie’s Dramatic and Cinematic Oeuvre

Introduction

In this entry, I trace the trajectory of Bahrām Bayzā’ī’s creative impulse and examine his oeuvre to offer an analytical overview of his aesthetic and thematic concerns and innovations. Before embarking on my chronological overview, however, I need to clarify a few general points. In my writing, I pay attention to a number of key ideas and practices which are central to Bayzā’ī’s vision: (1) modernity, modernization, and democracy, (2) marginalization, trauma, and creativity, (3) outsider gaze, epistemic privilege, and epistemic authority, (4) transgressive and emancipatory framing and reframing, (5) redistributing the sensible by introducing new ways of seeing, doing, and understanding, (6) modalities and transformations of personal and collective identities, (7) desire for belonging, recognition, and self-recognition as incentives for change, (8) constructive curiosity, worldliness, and intellectuality, (9) citizenship and leadership, (10) gender relations and hegemonic masculinity and femininity, (11) totalitarianism, patriarchy, and power, (12) sociopolitical and religious surveillance, (13) reformulation of Iranian and non-Iranian dramatic and cinematic forms to create new artistic forms, and (14) yoking these reformulated forms to particular situations to construct his emancipatory aesthetics.

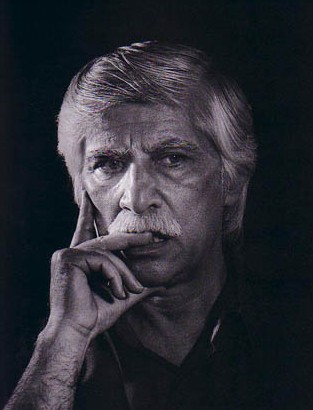

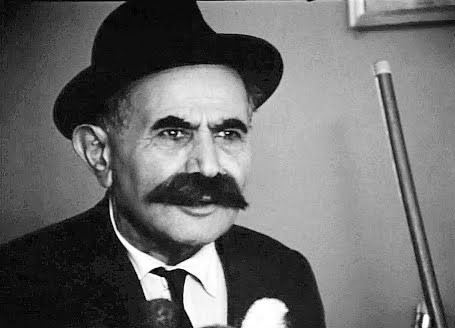

Figure 1: Portrait of Bahrām Bayzā’ī

Some of the terms I have used in this list need further clarification to specify the senses I give them in my writing. For instance, I use the term constructive to denote the range of qualities that facilitate individual and social health and prosperity. Thus, “constructive individuals” are those who lead a life of passion, purpose, and integrity dedicated to make the world a better place without hurting anyone. “Constructive curiosity,” therefore, is a type of curiosity that explores subjects or situations to resolve issues, help others, and prevent problems rather than to undermine or suppress others. Similarly, “constructive worldliness” means focusing one’s energy on the world to create better ways of living rather than, for instance, becoming obsessed with religious ideas. Relatedly, “constructive intellectuality” is the type that introduces new ways or spaces of seeing, learning, and acting in life. It is the type that dedicates its knowledge to solving problems and serving the community and does not obsess itself with criticizing without producing and creating.

Similarly, the idea of framing and reframing in my writing has two interrelated aspects. One is aesthetic and has to do with embedding dramatic rituals, performances, plays, trials or play-like scenes, cameras, or filming or cinema scenes within a play or a film in self-reflexive ways that transform the viewers understanding of rituals, drama, and cinema. The other is sociological and is concerned with how “framing” and “reframing” a social practice in a new situation or along other practices that are not usually associated with it changes its meaning to make the viewer conscious of the need to see certain beliefs, practices, or situations from new perspectives.1For more on framing as a sociological concept, see Erving Goffman, Frame Analysis: An Essay on the Organization of Experience (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1986), 44-46.

To fulfil my plan, I have separated the entry into sections that mark new trends in Bayzā’ī’s oeuvre that have evolved with time. I first examine the origins and evolution of Bayzā’ī’s creativity while introducing a theoretical framework which I continue to refer to in my analytical overview. Then, I go through Bayzā’ī’s works by examining his early years of playwrighting and research before moving to the years in which he added filmmaking to his already rich creative and research profile. The sections engage with the above fourteen key ideas and their subdivisions in different ways and also highlight to different degrees his impact on the rise of Iranian indigenous forms in Iranian cinema and modern drama.

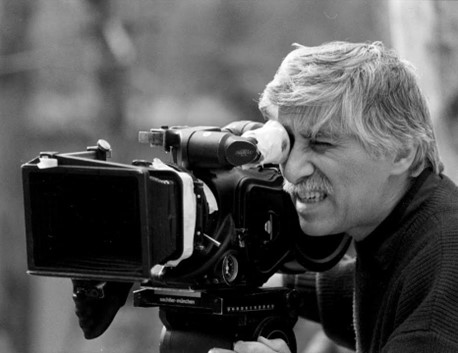

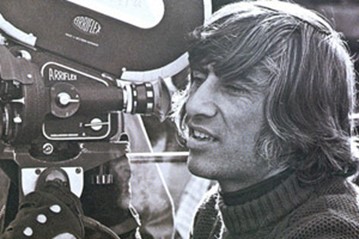

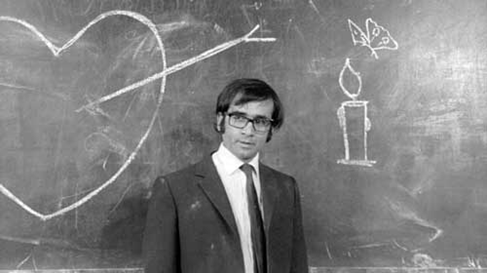

Figure 2: Bahrām Bayzā’ī on the film set.

Marginality, Epistemic Privilege, and Creative Impulse

Any overview of Bayzā’ī’s oeuvre must first examine the sources of his relentless creativity. These originate, from my perspective, in his ability to sublimate his traumatic experiences of marginalization into epistemic authority through dedicated learning, while at the same time maintaining the outsider gaze that has enabled him to explore old and new subjects from fresh perspectives. By “epistemic authority,” I refer to the ability to perceive problems that others neglect and to articulate new standpoints which challenge the cultural and sociopolitical constructs that cause those problems. Epistemic authority is thus rooted in epistemic privilege: the idea that some forms of knowledge are perceivable only by those who are directly affected by them, but not by others. In the context of psychology, this means that only an individual has privileged access to their own thought processes. In the context of the social sciences, however, it entails that those deprived of their rights by sociopolitical or religious centres or majorities apprehend the problems of these systems more acutely than those reaping the benefits of or remaining unharmed by them.2For “epistemic privilege,” see John Heil, “Privileged Access,” Mind 97, no. 386 (1988): 238-251; Bat-Ami Bar On, “Marginality and Epistemic Privilege,” in Feminist Epistemologies, eds. Linda Alcoff and Elizabeth Potter (London and New York: Routledge, 1993), 83-100; and Marianne Janack, “Standpoint Epistemology without the ‘Standpoint’? An Examination of Epistemic Privilege and Epistemic Authority,” Hypatia 12, no. 2, (1997): 125-139. Though similar in its essence, my conception of the term departs from these in how I link it to creativity, how I foreground the psychosocial processes leading to epistemic privilege, and how I emphasize the need to transcend minority and majority perspectives before such a process becomes possible. To clarify this, I usually use a door metaphor. If a door opens, the person leaving or entering a space never thinks of the door’s handle, frame, or hinges. However, if the door does not open, the person automatically scrutinises these parts of the door to find the issue. Thus, our pragmatic and goal-oriented mental processing means that we only notice problems when they affect us, or metaphorically speaking when the doors do not open for us. Rather than calling this state epistemic privilege, however, I call it the standpoint of the marginalized, and argue that epistemic privilege occurs only when such people gain psychological, sociopolitical, and historical self-awareness, exit the limits of their minority or marginalized outlook, and perceive the problems of those in other marginalized positions and that of the centre by understanding the way the system works. Indeed, the initial status cannot be a privilege if it only leads to suffering and pushes the person into self-pity and anger or makes them unable to see how other groups of people may suffer similar situations.

Epistemic authority, then, can only occur if such individuals are not cowed by the centre and thus try to prove that they are in fact more central to their culture than their suppressors by developing qualities that allow them to introduce new ways of seeing, doing, and understanding to confront the centre itself. The process also involves enhancing their ways of seeing with in-depth study or observation of other cultures, equipping them with a status of in-betweenness or an outsider gaze that helps them transcend their own minority obsessions and introduce emancipatory ways of seeing and doing to their wider culture. Further, the experience of marginality, as the initial trigger, does not need to be due to being a member of a marginalized group. Rather, it can result from any form of political, psychological, or social trauma that leads to early self-awareness: the death of a beloved person; a case of abuse; unjust imprisonment; a war or a revolution that deprives the person of a sense of belonging; or the experience of in-betweenness due to being exposed to different cultures at a young age so that the person becomes unable to fit in or accept any of these various cultures in their totality. Nevertheless, what guarantees epistemic authority is that, while identifying with the marginalized, the person rebels against marginalization and develops intellectual or physical qualities (e.g., creativity, knowledge, power, etc.) that make them appealing to the non-totalitarian members of the so-called centre.3For a theoretical analysis of Bayzā’ī’s creativity, see Saeed Talajooy, “Introduction,” in Iranian Culture in Bahram Beyzaie’s Cinema and Theatre: Paradigms of Being and Belonging (London and New York: Bloomsbury/I. B. Tauris, 2023).

Bayzā’ī’s creativity indicates just such a quality in its origin as well as in its focus on marginalization and marginalized artistic forms, social practices, narratives, and people. Bayzā’ī was born in Tehran on 25 December 1938. His father was a poet who organized a poetry group, and his mother and maternal grandmother were strong, intelligent, witty women with a passion for poetry and a treasure of folktales that triggered his early interest in folklore and myths. His forefathers were also among the leading directors of taʿzīyah passion plays in Ārān and Bīdgul County of Kāshān. This already rich cultural origin was further enhanced by his exposure to religious debates and Bahā’ī ideas due to his father’s conversion to Bahā’īsm. Though Bayzā’ī never practised Bahā’īsm as an adult and became an agnostic in his teenage years, he learned a lot from such debates while also suffering the consequences of his family’s religion from an early age. During his adolescence, he was also exposed to various vestiges of how dominant discourses marginalize the people, practices, and beliefs that contradict their reductive narratives of national identity. With the Allies’ occupation (1941-46) already shaking the country’s culture, politics, and economy, Bayzā’ī observed on a daily basis: the consequences of religious, party, and state terrorism of the early 1950s; the conflicts over the nationalization of Iran’s oil industry (1950-53); the suppression and executions of leftist and pro-Musaddiq intellectuals, military officers, and political activists before and after the 1953 coup; and the clampdown on Bahā’īs following the broadcast of Muhammad Taqī Faslafī’s anti-Bahā’ī speech on Radio Iran, the country’s national radio, in 1955.4See Michael Fischer, Iran: From Religious Dispute to Revolution (Cambridge and London: Harvard University Press: 1980), 187; and ‛Alī Davānī, Khātirāt va Mubārizāt-i Hujjat al-Islām Falsafī (Tehran: Markaz-i Asnād-i Inqilāb-i Islāmī, 2003), 200.

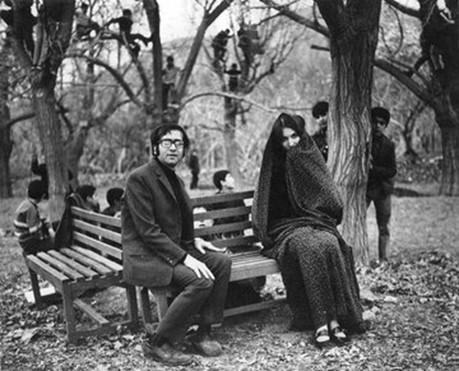

Figure 3: Bahrām Bayzā’ī on the set of Kalāgh (The Crow, 1977).

Growing up in such a tense context, Bayzā’ī developed an interest in cinema in the 1950s, first as a space to escape the violence of his teachers and classmates, and then as a field of interest and research where his evolving creativity identified the means to deconstruct the cultural narratives that justified such forms of violence against anyone who was deemed different.5See Mustanad-i Rīshah-hā (Roots), accessed January 15, 2021 via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xlNdgLRXbEs (00:02:00-00:15:00). Rīshah-hā is a documentary on Bahrām Bayzā’ī, directed by Ahmad Nīkāzar. Following the same path, in 1958, he joined Farrukh Ghaffārī’s Cine Club where he was exposed to art films and began to see and read plays and became interested in the indigenous-style plays similar to those staged by Gurūh-i Hunarhā-yi Millī (the National Art Troupe). These two passions—cinema and theatre—reshaped the young Bayzā’ī’s earlier interests in myths and folk culture to push him towards dedicated research on Iranian and non-Iranian art forms, but since it was not possible for him to make films in these early years, his creativity began to be reflected in writing plays and publishing articles on Iranian performance traditions.6See Talajooy “Chapter 1” in Iranian Culture. See also Saeed Talajooy, “Beyzaie’s Formation, Forms and Themes.” Iranian Studies 46, no. 5 (Autumn 2013): 689-693; as well as Talajooy, “Introduction: Bahram Beyzaie, A Critical Overview.” In The Plays and Films of Bahram Beyzaie: Origins, Forms and Functions, ed. Saeed Talajooy (London: I. B. Tauris, 2024). It will also be useful to look at Muhammad ‛Abdī, ed., Gharībah-yi Buzurg: Zindigī va Sīnimā-yi Bahrām Bayzā’ī (Tehran: Sālis Publication, 2004), 13-32.

Figure 4: Bahrām Bayzā’ī on the set of Kalāgh (The Crow, 1977).

Bayzā’ī’s Rise as a Leading Dramatist (1959-1970)

1959-1961: Theatre Scholarship and Early Plays

Between 1959 and 1961, Bayzā’ī studied Iranian myths, literature, and performance and visual art forms. His intention was to find ways to depict the lives of contemporary Iranians while remaining rooted in Iran’s artistic and material culture. He discovered taʿzīyah passion plays, puppet plays, and taqlīd comedies, and published articles on cinema and then drama in literary journals.7Ta‛zīyah refers to dramatic performances associated with Ashura, the annual mourning rituals commemorating the martyrdom of the Shiite saint, Husayn, and the male members of his family. With the establishment of Twelver Shiism as Iran’s official religion in the sixteenth century, these annual rituals became a locus for the reinforcement of an imagined national identity based on religious cohesion. During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, due to royal patronage, the semi dramatic aspects of these rituals transformed into dramatic forms, creating passion plays about sacrificial figures in Shiite historiography, including plays on Abel, John the Baptist, etc. Ta‛zīyah reached its highest status in the nineteenth century when it gave birth to about 2,000 plays on more than 270 subjects, including secular and comic ones. Ta‛zīyah is a treasure house of dramatic techniques from expressionist and minimalist depictions to grand scale re-enactments. The audience knows the events and outcomes of the plays, which are written and recited in verse. The unities are not observed: the characters might go from one city to another by circling the stage and the time is usually announced in the dialogue. Costume and makeup are essential, but the scenery is usually minimal: a basin of water may stand for the Euphrates, a palm branch in a vase for a grove of palms, a black handkerchief for mourning. Yet during the 1800s it was also possible to see Ta‛zīyah(s) of epic grandeur with hundreds of people performing. Taqlīd (imitating) is a general term used for a range of comic forms which used dance, music, witty dialogue, happy-ending plots and routines, and imitations of accents and typical movements of different types of people to draw laughter. Its different forms originate in the musical plays of pre-Islamic traveling and court entertainers, known after Islam as mutrib(s) (entertainers). From the seventeenth century, due to royal patronage, mutrib(s), who also performed in such carnival forms as Mīr-i Nawrūzī (Lord of Misrule) and Kūsah bar Nashīn (The Ride of the Beardless One), increased the dramatic qualities of their forms and gradually expanded them to create taqlīd plays in the nineteenth century. Up to the early twentieth century, the actors improvised in the fashion of commedia dell’arte to dramatize satirical or folktale scenarios dealing with moral or socio-political issues. These brief descriptions of Ta‛zīyah and Taqlīd have been adapted from Saeed Talajooy, “Indigenous Performing Traditions in Post-Revolutionary Iranian Theatre,” Iranian Studies 44, no. 4 (July 2011): 497-8. For more, see Bahrām Bayzā’ī, Namāyish dar Īrān (Tehran: Rushangarān, 2001 [1965]), 157-204; Willem Floor, History of Theater in Iran (Odenton, MD: Mage, 2005), 13-61. For a year he also studied Persian literature at Tehran University, but when he noticed the lack of interest in his favourite subjects, he left the university to write his book on indigenous performing traditions.8The sections of Bayzā’ī’s Namāyish dar Īrān were originally published as articles in Majalah-i Mūsīqī between 1962 and 1963. Later in 1965 Bayzā’ī republished the revised versions of these articles as a book which has been republished many times ever since. Bayzā’ī refers to this choice as an initially unwanted yet inevitable one which led to a pleasant development in his career. Years later in 1977, when he had already established himself as the most prolific playwright of modern indigenous-style plays and had directed four films, Hazhīr Dāryūsh, a journalist and filmmaker, asked him about the sources of his creativity and why he engaged with indigenous forms. His response revealed an outlook that has remained true:

I did not choose theatre; theatre chose me. When it could not find anyone, it placed itself on my path with the bewildering plays of Shakespeare or Greek or Far East playwrights. I was not tricked until one day theatre revealed its beauty to me in a taʿzīyah play that charmed my soul. This was when cinema had turned its back on me . . . I felt I had to rise to its challenge, find the causes of its enchanting beauty and the reasons for my fascination. It made me aware of my paucity, aware of what I was. Suddenly, I became conscious of the abyss behind me, of the baseless grounds under my feet. I realized that my historical wounds cannot be healed or beautified with cosmetic borrowings from others and that my ancestral treasure had been hidden from me. I studied history and found myself heir to an immense world of atrocity and fear. Yet I gradually began to hear the voices of people, the voices of those who have not been mentioned in history. For four years I wrote exegeses on Iranian theatre tradition. Until that strange day when I realized that I myself had to create . . . I sat down and wrote. It is now twenty years that I have been looking for my lost dreams.9Bahrām Bayzā’ī and Hazhīr Dāryūsh. “Tark-i Ghughā-yi Dukkān-dārān,” in Simia: Vīzhah-yi Bahrām Bayzā’ī va Ti’ātr 2 (Winter 2008): 36-42 (All translations are mine).

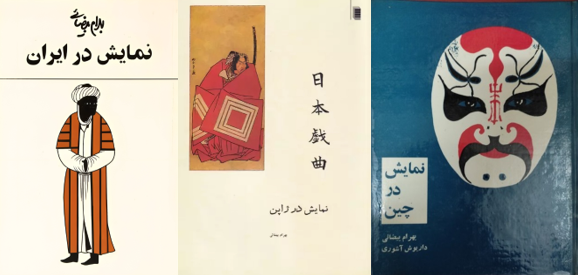

Bayzā’ī’s words suggest some of his main concerns which have persisted across his career as an artist: reformulating Iranian indigenous forms for modern theatre and cinema and rereading Iran’s history and myths—not to glorify kings and heroes but to echo the voices that have been marginalized and find what went wrong to produce the present issues. Bayzā’ī had also noticed that artistic and theatre establishments and even universities tended to deny that Iran had a performing tradition. Thus, he dedicated the first decade of his work to writing about and reviving indigenous Iranian forms and introducing Asian Theatre to Iranian practitioners. The result was the publication of several journal articles which he later published as books, including Namāyish dar Īrān (Theatre in Iran, 1965), Namāyish dar Zhāpun (Theatre in Japan, 1966), and Namāyish dar Chīn (Theatre in China, 1969), or as pamphlets for university teaching such as Namāyish dar Hind (Theatre in India, 1971). These monographs established Bayzā’ī as a leading contributor to the cosmopolitan discourses of Iran’s return-to-the-roots movements. These movements aspired to modernize indigenous Iranian forms and expand the horizons of Iran’s culture by engaging not only with Euro-American art forms but also with Asian and Middle Eastern ones.10Others who contributed to this movement included poets like Suhrāb Sipihrī and Ahmad Shāmlū, theatre practitioners like ‛Izzatallāh Intizāmī and ‛Alī Nasīrīyān, and intellectuals like Dāryūsh Shāyigān and Dāryūsh Āshūrī.

Figure 5-6-7: Book covers (from left to right): Theatre in Iran (1965), Theatre in Japan (1966), Theatre in China (1969).

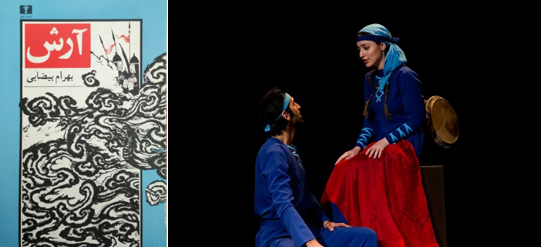

Between 1959 and 1963, Bayzā’ī rewrote his play Ārash (written 1958, revised 1963, published 1977), which he had written earlier in response to Sīyāvush Kasrā’ī’s poem Ārash-i Kamāngīr (written 1954, published 1959).11In this entry whenever I discuss a work in detail, I use bold fonts for its title. Sīyāvush Kasrā’ī (1927-96) was a leftist poet whose modernist epic poem on the mythical archer Ārash depicts him as a proletarian hero of the people and a saviour who shows up in the nick of time to save his people from slavery after the country’s army has been defeated. See below for more on Ārash. He also wrote his own rendition of the myth of Zahhāk in Azhdāhāk (written 1959, published 1966) and a recitation piece about the myth of Jām-i Jam (The World Displaying Chalice) that he later published as Kārnāmah-yi Bundār-i Bīdakhsh (Account of Bundār, the Premier, written 1961, published 1996).12The World Displaying Chalice or The All-Seeing Chalice is a mythical device through which the ideal Iranian Kings could observe the events of the world, predict the future, or find whatever they were looking for. Though the name associates it with Iran’s mythical King Jamshīd, a.k.a. Jam, in the Shāhnāmah, it is only mentioned in relationship with Kaykhusraw, the most spiritual Iranian King, who uses the chalice to find Rustam’s grandson, Bīzhan, who is imprisoned in Tūrān. Some scholars argue that the association of the cup with Jamshīd has its origin in the fact the Muslims began to identify Jam as Sulaymān and thus attributed the chalice to Jam. Some others, however, state that it has been a poetic trope due to the similarities of the terms jām (chalice) and Jam (Jamshīd). Nevertheless, it is very likely that the attribution had more to do with Jamshīd’s mythical role as the civilizational initiator and the person who invented wine. From the twelfth century onward, the poetic interpretations of the chalice became increasingly more mystic, and the chalice came to symbolize the illuminated heart of the Sufi. For more, see Jamīlah Aʿzamīyān Bīdgul, “Jām dar adabīyāt-i fārsī va pīshīnah-yi ān,” Faslnāmah-yi Adabīyāt-i ‛Irfānī va Ustūrah-Shinākhtī, Year 5, no. 17 (Winter 2010): 9-23. These pieces, which function as recitation plays for one, two, or more actors, draw upon naqqālī’s subject matters and narration techniques to deconstruct the king- and hero-centered voice of the omniscient narrator of mythology and call for rereading the past and its narratives of belonging from perspectives that allow for more inclusive understandings of citizenship, leadership, and the location of the other in our social discourses.13Naqqālī (recounting) is an ancient form of dramatic storytelling. Pardah-khān(s) (pictorial recounters) were naqqāl(s) who set up paintings of the key scenes of their narrated legends and used them by moving from one image to another while narrating and performing the scenes. A naqqāl who carried pardah and specialized in religious stories was called pardah-dār. Naqqāl(s) performed on platforms in coffee houses or in bazaars. For more, see Saeed Talajooy, “The Genealogy of Ārash, A Hero: From Naqqāli to Beyzaie’s Recitation Plays and from Mythical Ārash to Beyzaie’s Marginalized Ārash,” in Bahram Beyzaie’s Drama and Cinema: Origins, Forms and Functions, ed. Saeed Talajooy (London: I. B. Tauris, 2024), 25-28. These early works already display Bayzā’ī’s deconstructive vision and his understanding of modernity as a process of facing the worst in ourselves and discarding our illusions of grandeur in order to construct better futures. As discussed below, they also subvert common assumptions about the mythical characters involved.

For instance, in the original myth, Ārash is a born hero, selected by Isfandārmaz, the Iranian Goddess of Earth, and Manūchihr, the king, to fulfil a sacrificial act. After the Iranians have been defeated by the Tūrānians, they are given a binding offer specifying that they may regain their lost land but only to the extent of s single arrowshot. Isfandārmaz advises the king’s craftsmen on how to make the bow and the arrow and helps choose Ārash, who shocks the victors by shooting an arrow that travels from the southeast coast of the Caspian Sea to Transoxiana and perishes in the act. The original mythical Ārash, thus, is a sacrificial hero whose sacrificial act, according to Bīrūnī, was also associated with a purgation festival.14Abū Rayhān Bīrūnī, Al-Āsār Al-Bāqīyah ‛an Al-Qurūn Al-Khālīyah, trans. Akbar Dānāsirisht. (Tehran: Amīr Kabīr, 2007), 334-35. For an analysis of the myth and its reformulations in Iranian cultural products, see Talajooy, “The Genealogy of Ārash,” 23-55. In Bayzā’ī’s play, however, the eponymous Ārash is a shepherd drafted into the army as a horse groom, and he eventually fulfills the heroic feat because he is cornered by both the Tūrānians and by his own people, the Iranians. The Tūrānians, who are following the advice of the defecting Iranian warrior Hūmān, aim to ridicule the Iranians by having a shepherd shoot the arrow that is to determine the border between their two kingdoms. The Iranians, however, assume Ārash has volunteered to shoot the arrow because he is a spy. If he says no to shooting the arrow, the Turānians will massacre the Iranian soldiers; if he says yes, the Iranians will conclude that he is a spy. Bayzā’ī highlights how his frustration with this intense ostracization pushes him to achieve this improbable feat. However, he also reflects the people’s craving for the arrival of a superhuman hero to resolve their issues and presents the arguments put forward by the wise warrior Kashvād to demonstrate that Ārash’s heroic act is likely to lead to nothing but the perpetuation of people’s obsession with messianic saviours that makes people apathetic to their responsibilities and leaves the culture at the mercy of tyranny.

Figure 8 (left): Book cover, Bayzā’ī’s Ārash (1977).

Figure 9 (right): A scene from the 2010 production of Ārash, directed by Gulchihr Dāmghānī.

The case of Azhdāhāk is also similar. In the original myth of Zahhāk, as recorded in the Shāhnāmah, the young prince becomes evil in three steps: (1) Satan incites him to kill his father and replace him; (2) Satan appears as a chef who prepares meat-based foods for him and when Zahhāk wants to reward him for his unique foods, Satan requests to kiss Zahhāk’s shoulders; (3) two snakes grow on his shoulders from the locations of Satan’s kisses causing him intense pain and fear, but Satan appears as a physician and advises him to calm the snakes by killing two young men every day and feeding their brains to the snakes. Bayzā’ī uses the myth as a background for a dramatic monologue that echoes the unheard voice of the demonized king to show how marginalization alienates people and leads to the continuation of vicious circles of violence. Thus, in Bayzā’ī’s Azhdāhāk, Zahhāk’s snakes are made to embody the hate that Jamshīd’s suppression of his non-Iranian subjects planted in him, and he is ultimately shown to be a suffering loner who was only depicted as evil to justify his suppression and enchainment.

Figures 10-11: A scene from the production of The One Thousand and First Night (Shab-i Hizār u Yikum, 2003), directed by Bahrām Bayzā’ī.

The case of Bundār, which I analyse later in this entry when dealing with Bayzā’ī’s rewriting of the play in 1995, is more imaginative as Bundār is an entirely imaginary character. In the play, Jamshīd is not the benevolent initiator of Iranian culture, but instead a paranoid king who claims the scientific achievements of his lead advisor, Bundār, and supresses the people around him so much that Bundār destroys his invention, the “world displaying chalice,” to stop Jamshīd from using the device to find and massacre dissidents.15For more on these recitation plays, see Saeed Talajooy, “Reformulation of Shahnameh Legends in Bahram Beyzaie’s Plays,” Iranian Studies 46, no. 5 (Autumn 2013): 695-719; and Talajooy, “Genealogy of Ārash,”

Figure 12: Hamīd Farrukhnizād and Bahrām Bayzā’ī on the set of the play The One Thousand and First Night (Shab-i Hizār u Yikum, 2003).

1962-1963: Bayzā’ī’s Puppet Plays

Following the publication of his first articles on Iranian theatre, Bayzā’ī, who had been employed as a clerk for a notary public, was transferred to the Office of Dramatic Arts. His experience in the notary office as an institution in which people are reduced to numbers and records is later reflected in some of his Kafkaesque scenes, such as in Ishghāl (Occupation, 1980) or Sag-kushī (Killing Mad Dogs, 2000), but the transfer also enabled him to cooperate with several theatre troupes as a text editor, designer, and assistant director.

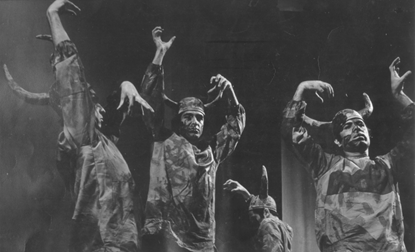

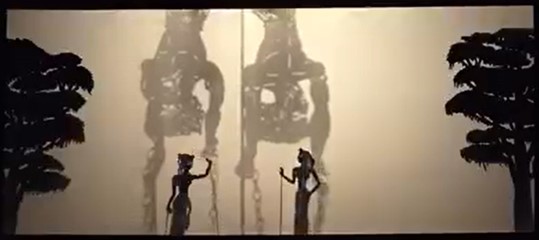

The first products of this cooperation were three puppet plays: ‘Arūsak-hā (The Marionettes), Ghurūb dar dīyārī gharīb (Sunset in a Strange Land) and Qissah-yi māh-i pinhān (Tale of the Hidden Moon) in 1962-63. These three plays reframe the customary metatheatrical dialogue between the narrator/puppeteer and his puppets in Iranian puppet form (khaymah-shab-bāzī) to create an emancipatory aesthetics. The result is that the plays’ form comments on heroism, leadership, demonization, and citizenship by highlighting the impacts of dominant discourses on our minds in a context in which actors who move and talk like puppets begin to act as humans, rebel against the roles imposed on them for thousands of years and initiate new forms of dialogue with each other and the narrator. In the course of the three plays which are separate but have underlying similarities, the Hero realizes that he has been the victim of a culture in which people expect heroes to solve their problems and finds that the so-called Demon is only an oppressed individual. When the Hero and the Demon refuse to fight and the puppeteer destroys them, the Girl and the Black begin to rebel against their roles, think for themselves, and face both the positive and negative impacts of their decisions. The Girl realizes that she has been made to be either an object of desire or a damsel in distress, and the Black, who represents the downtrodden, announces that he wants to be a hero because he is tired of being a jester or being marginalised or demonized if he refuses to do so. Their self-awareness and revolt, however, are shown to be only the first steps which cannot, on their own, end the vicious circle of clichéd social roles, demonization and heroism.16See Talajooy, Iranian Culture, 37-70.

Figure13: Book cover, Bayzā’ī’s Three Puppet Plays (1963).

As reflected above, this period marks Bayzā’ī’s focus on examining and reformulating the ideals of heroism, leadership, and citizenship in response to the centrality of these subjects in the post 1953-coup era in which the tough guys and the military went against the will of the people by supporting the shah’s decision to end Musaddiq’s premiership. Bayzā’ī does this systematically by first examining the world of mythical heroes in Ārash and then reformulating the meaning of heroism in folktales in his puppet trilogy. In his third step, then, he goes to the hero of Zurkhānah and the Iranian javānmardī cults in Pahlivān Akbar mīmīrad (So Dies Pahlivān Akbar, 1963). The play used the linguistic registers, ambiance, and mentalities of the frequenters of the zurkhānah (traditional sport club), folktales concerning javānmardī (chivalry) cults, and their famous role model, Pūrīyā-yi Valī (Pahlivān Muhammad Khvārazmī, 1255-1323), to reconstruct the ideals of heroism. It played a significant role in initiating a new interest in javānmardī and its ideal heroes, pahlivān and ‛ayyār, in contrast with the streetwise tough guy characters that had become central to Iranian cinema since 1958.17Iranian javānmardī cults, which have their origins in ancient Mithraic practices, continued their evolution after Islam with military, physical, and spiritual training programmes for the youth and the practitioners of different crafts. Characterised by seven stages of development in Zurkhānah training, these cults, which were similar in their core practices, used the skills and physical qualities of the trainees to perpetuate three heroic types. Among these, a javānmard is a practitioner who serves his community by being skilled in a profession and adhering to the moral codes of the cult by helping the weak and the poor and joining hands with other javānmard(s) to defend their land, a pahlivān is a leading javānmard, a champion and a warrior skilled in single combat, wrestling and military leadership, and an ‛ayyār is a javānmard who has ninja-like fighting skills, is adapt in a particular type of fighting, or is a master of disguise, climbing walls, making trenches, or saving captives from enemy lands. For more, see Saeed Talajooy, “A Pahlevān’s Failed Quest for Belonging: Reconfiguration of the Ideals of Heroism in Beyzaie’s So Dies Pahlevān Akbar,” in The Plays and Films of Bahram Beyzaie: Origins, Forms and Functions, ed. Saeed Talajooy (London: I. B. Tauris, 2024). It also introduced the possibility of writing and successfully staging a play with a dying hero, a figure who became central to alternative Iranian films a couple of years after the play was staged by ‛Abbās Javānmard in 1965.

The play, which features the last hours of the indomitable wrestler and warrior Pahlivān Akbar, uses his soliloquies to depict a selfless, lonely man. Akbar, who was lost as a boy, grew up among nomads, and was ostracized as impure and kicked out by the nomads when he fell in love with one of their young women, ended up routing bandits and becoming a wrestling champion to prove his value to others. Now tired of leading a loveless life of fighting uselessly in a corrupt world in which officials are more corrupt than bandits and being the only person who stands against the tyranny of the political and religious elites, he faces the challenge of fulfilling the prayer of an old woman who prays for her son’s victory over Pahlivān Akbar. Bayzā’ī thus reformulates the legends of ideal heroes, who are lost or misplaced in childhood—Cyrus, Kaykhusraw, Zāl, Dārā, etc.—to create a play that analyses the traumatic origins, the loneliness, and the consequences of leading a life of selfless heroism and javānmardī ideals in a society fraught with political and religious corruption, opportunism, and exclusionism. Pahlivān Akbar’s captivating soliloquies offer an intensive form of psychological probing and depict selfless heroes as victims of marginalization and exploitation. The play thus reflects on how a marginalized person’s desire for belonging and love may initiate a quest for recognition that sets them on a pathway to becoming an outwardly indomitable hero who remains inwardly broken and lonely. It also examines how this quest for recognition distorts the person’s happiness due to other people’s expectations once the heroic individual achieves unique qualities. Bayzā’ī’s gaze also reflects on the individual’s conflict with his or her psychological shadow. This is seen most vividly, it can be argued, when the Kafkaesque figure uses Pahlivān’s own machete to kill him, representing death at the hands of the manifestation of his own shadow. Indeed, even if one interprets the figure as an assassin or a bandit who is after revenge, it is Pahlivān’s own death wish which makes him set aside his sword and turn his back to the black-wearing man as if surrendering to death. The play thus suggests how the potential of a powerful and responsible individual for creativity and productivity is distorted by the fact that other people remain passive, expect too much from him, and leave him to suffer when he needs help.18Talajooy, “A Pahlevān’s Failed.”

Figure 14: A scene from the 1965 production of So Dies Pahlivān Akbar (1963).

1964-1967: From Sinbad and Mr. Asrārī to The Feast and Four Boxes

Bayzā’ī’s involvement with the National Art Troupe, his trip to France for the performance of his second and third puppet plays Sunset in a Strange Land and Tale of the Hidden Moon as part of the Theatre of Nations Festival in Paris, and his own directorial debut with his first puppet play, The Marionettes, for Iranian television in 1966 established him as a leading voice in Iranian theatre. This position was further established by the plays that he wrote between 1964 and 1967, including Hashtumīn safar-i Sandbād (The Eighth Voyage of Sinbad, written 1964, published 1971), Dunyā-yi matbū‛ātī-i āqā-yi Asrārī (The Journalistic World of Mr. Asrārī, written 1965, published 1966), Sultān-i Mār (The Snake King, written 1965, published 1966), and Zīyāfat (The Feast), Mīrās (The Inheritance), and Chahār Sandūq (Four Boxes), written in 1967, published in 1967. Each of these plays introduced new forms of dramatization and new perspectives on politics, arts, society, and culture which diverged from dominant discourses, ultimately commenting on how individuals fall victim to the machinations of opportunistic elites or inherited narratives that distort their identity. As in So Dies Pahlivān Akbar, a major theme in these plays is human identity and how a person’s understanding of their life may be different from what others assume about that person, and how it is impossible to transform these inflated or distorted assumptions. In The Eighth Voyage of Sinbad for example, Bayzā’ī emphasizes the unreliability of history and how official accounts twist reality for the political or personal gain of ruling elites. Returning after a thousand years, Sinbad finds that the accounts of his life and adventures have been distorted and thus performs the real story of his life in a series of public plays to change the people’s incorrect assumptions about him. While these plays demonstrate how, in their quest for imagined happiness, human beings sacrifice the possibility of the simple happiness of love and productivity, Sinbad’s final failure to change the minds of the populace indicates the impossibility of altering people’s illusions and assumptions once they are trapped by the so-called common sense that dominant discourses have injected into their minds.

Bayzā’ī’s The Journalistic World of Mr. Asrārī was also special in its fast-paced, thriller-like plot that depicted the victimization of talented people in a society obsessed with class, money, and title. Bayzā’ī continued working with such plots in his noire-like city films, but this particular theme evolved in his later works to demonstrate how those who can contribute to the scientific and cultural growth of their society are exploited by those who crave power. It was also one of the earliest of Iranian plays and films that focused on the metamorphosis of the common man in a distorted culture. The machinations of exploitation, which work via the weight of the social gaze, economic pressure, or direct compulsion, pin the individual into a given role to exploit their skills—or derail their progress if they do not comply. The plot of The Journalistic World of Mr. Asrārī demonstrates this theme vividly: the nephew of the chief editor of a failing journal publishes the stories of a young typesetter under his own name; the journal’s readership skyrockets due to the popularity and literary genius of the stories; and the editor uses economic and peer pressure to disrupt the typesetter’s attempt to prove his authorship.

Figure 15: Book cover, Bayzā’ī’s The Journalistic World of Mr. Asrārī (1966).

Another key play, The Snake King, reformulated the techniques of taqlīd improvisatory comedies to recreate several folk narratives, particularly “Mihrīn Nigār and the Snake King” as a folk play commenting on colonialism, leadership, citizenship, and democratic change. While depicting human identity as a process of changing masks, the play uses creative theatricality and role playing as sites of emancipatory revelation. The intelligent daughter of a premier and her beloved, a young prince who has been disguising himself as a snake, revolt against the unscrupulous upholders of the hierarchies of power to help the downtrodden people, the demons, to regain a sense of humanity. However, like the other good rulers in Bayzā’ī’s oeuvre, they relinquish power once they bring justice to the land.

Bayzā’ī’s focus on how arrogant, greedy leaders, tribal and ethnic rivalries, and harmful, cultural obsessions may expose a country to colonial exploitation continued in his one-act plays The Feast and The Inheritance. The first depicts a village community in which the leaders are the real wolves who betray and destroy the cattle for their personal gain. The second demonstrates how the inane squabbles of three brothers leave their inheritance at the mercy of thieves. Four Boxes, written during Mohammad Reza Shah’s coronation in 1967, mixes the taqlīd dance play of four boxes with puppet forms to comment on the political situation of Iran since the early 1940s. As Bayzā’ī’s most political play of the 1960s, it depicts how four characters representing four social types fall victim to a scarecrow that they create to fend off foreign invaders. In a now famous scene, the play features the armed scarecrow ceremonially sitting on a throne after he subdues Yellow (the intellectual), Green (the clergy), Red (the businessman), and Black (the worker) and imprisons them in their boxes. Bayzā’ī directed the first two plays with the National Theatre Troupe, but the political suggestiveness of Four Boxes led to its being banned from formal performances until recently.19Respectively see, Bahrām Bayzā’ī, “Zīyāfat,” “Mīrās,” and “Chahār Sandūq” in Dīvān-i Namāyish 2 (Tehran: Rushangarān, 2002), 1-150. For an analysis of Four Boxes, see M. R. Ghanoonparvar, “Collective Identity and Despotism: Lessons in Two Plays by Bahram Beyzaie,” Iranian Studies 46, no. 5, Special Issue: Bahram Beyzaie’s Cinema and Theatre, ed. Saeed Talajooy (September 2013): 753-64.

Figure 16: A scene from the 1968 production of The Snake King (1968), directed by Bahrām Bayzā’ī.

1967-1970: The End of an Era

The years between 1967 and 1970 mark the final years of Bayzā’ī’s focus on theatre as the sole channel of his creativity. He continued writing plays after this point, but he gradually shifted his focus by writing screenplays from 1967, teaching at the University of Tehran from 1969, and making films from 1970. It was also during this period in 1969 that his performance of The Snake King in Mashhad was disrupted by radical leftists. The event left an indelible mark on Bayzā’ī’s mind to the extent that it further urged him to avoid the intense atmosphere of the theatre and focus on his university job and filmmaking.20Bayzā’ī and Dāryūsh, “Tark-i Ghughā.” During the event, which according to some sources had been organized by Sa‛īd Sultānpūr (1940-81), protesters chanted slogans, threatened to kill Bayzā’ī, and accused him of selling himself to the state even though he had long been involved in the campaign for freedom of speech and was one of the founding members of the Kānūn-i Nivīsandigān (the Writers’ Association, 1968-).21See Mahmūd Dawlatābādī, “‛Abbās Āqā tu Khaylī Shabīh-i Hidāyat Hastī,” in Dīgarān-i ‛Abbās Na‘lbandīyān, ed. Javād ‛Ātifah (Tehran: Mīlkān, 2015), 235; and Bahrām Bayzā’ī, “Āzādī Mīkhāstand barāyi Sānsūr-i Dīgarān: Guftugu bā Bahrām Bayzā’ī kih dar Shab-hā-yi Shi‛r-i Goethe bi Jā-yi Hukūmat Rushanfikrān rā bih Naqd Girift,” Andīshah-yi Pūyā 5, no. 39 (December 2016): 133. According to Bayzā’ī, Sultānpūr was not in Mashhad on the day, but he had visited the city three days earlier. Bahrām Bayzā’ī, interview by Saeed Talajooy, various dates and locations, 2015-2023; further instances in this article referred to as “Interviews.”

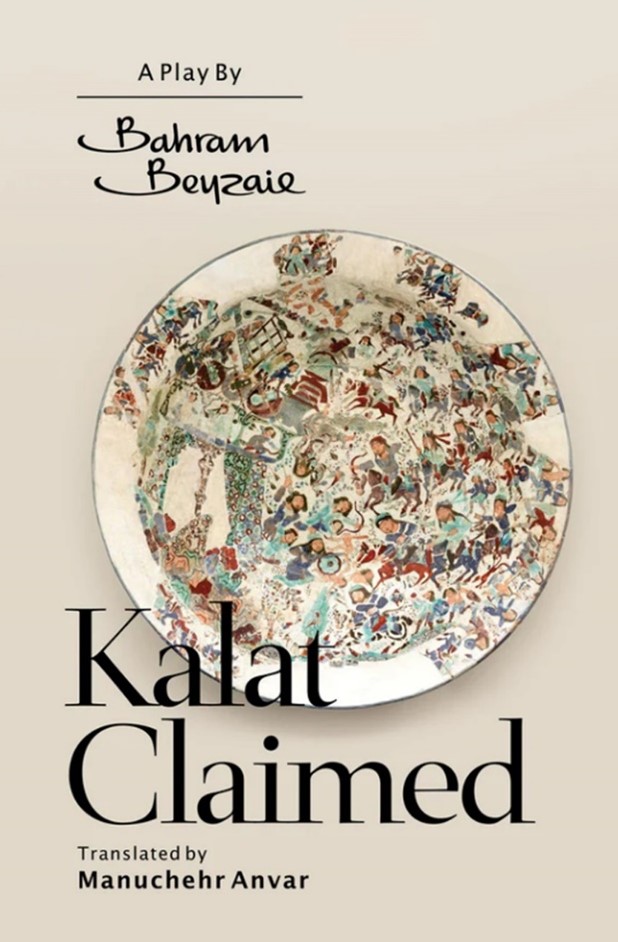

Among the plays written in this period, Dīvān-i Balkh (Court of Bactria, written 1968, published 1968) extended Bayzā’ī’s experimentation in turning taqlīd into a drama of emancipation and cultural resistance against the suppressive and exclusionist attitudes of the state, the clergy, and the radical left in Iran. The play mixes folk narratives of ‛ayyār warriors and historical and folk accounts about the corruption of Bactria’s (Balkh) officials and judges with Iranian comic forms. This mixture of influences and narratives creates an extended taqlīd piece about the resistance of people against unscrupulous rulers and their agents who use their immunity to rob people of their properties, reputations, and lives. If Four Boxes contracts taqlīd into a focused political allegory, Court of Bactria expands it, turning its stereotypical characters into life-affirming individuals facing the ruling elites’ tyranny and hypocrisy through role playing and creative theatricality. In doing so, the play thus turns indigenous dramatic forms into modern sites of resistance against economic, political, and religious opportunism. Bayzā’ī also echoes the special place given to women ‛ayyārs in Iranian romances and women’s agency and quests in his own earlier plays, particularly The Snake King, to construct the character of Marjān, one of his early heroines who engage in direct action against injustice.22Iranian popular romances and ‛ayyāri tales involve quests in which ‛ayyārs and pahlivāns embark on such adventures to fulfil tasks. In many of these, including Arrajānī’s rendering of the Parthian romance, Samak-i ‛Ayyār (ca. 1100s), or Tarsūsī’s Dārabnāmah (ca. 1100s), women ‛ayyārs and warriors play significant roles. The play also comments on social cruelty, including a scene in which a trader requests a handful of flesh from the body of a young man as payment for his debt, and another in which the true sinners engage in stoning an innocent woman to death.23Bayzā’ī, Dīvān-i Namāyish 1, 224-29. The account concerning flesh as payment is present in the original tales, such as Qāzī-i Hums, which predate Shakespeare’s Merchant of Venice. See Mujtabā Mīnuvī, Pānzdah Guftār (Tehran: Tūs, 2004), 181-205.

As Hamid Amjad states, at a metaphorical level, the play also reflects on the conflicts that led to the 1953 coup. Thus, in a scene which mirrors Musaddiq’s talk in Bahāristān Square, just before being ousted by the state opportunists and their thugs, the good judge in the play delivers a talk in “Nawbahār Square” to declare his intention to bring justice to the city.24Hamid Amjad, “Khānish-i Naʿlbandīyān dar Matn-i Zamānah-ash,” Daftarhā-yi Ti’ātr, no. 16 (March 2021): 38-39. As in So Dies Pahlivān Akbar, Bayzā’ī’s success in adding modern dramatic vibrancy to the speech registers of medieval ‛ayyāri tales by combining them with contemporary terms caught the attention of other writers.25‛Ayyāri tales are popular romances in which ‛ayyārs plays central roles. See footnote 22. In a general assessment of Bayzā’ī’s writing, for instance, Mahmūd Dawlatābādī argues that Bayzā’ī is a modern thinker with clear formal and thematic historical awareness. Dawlatābādī goes on even further, however, to compare him with Saʿdī in his versatility and notes how, during a group reading of Court of Bactria, he was impressed with Bayzā’ī’s ability “to revive the language of our ancestors for the stage.”26Mahmūd Dawlatābādī, Mīm va Ān Dīgarān (Tehran: Nashr-i Chishmah, 2014), 110-11. For Hūshang Gulshīrī’s comments on So Dies Pahlivān Akbar, see also Bahrām Bayzā’ī, “Rushanfikr-i Tamām-vaqt,” Andīshah-yi Pūyā, no. 33 (March 2016): 114. Despite these qualities and the impacts it has had on many cultural products that dealt with medieval stories, Court of Bactria was banned from performance at the time and has remained unperformed to the present.

During the same year, Bayzā’ī wrote Gumshudigān (The Lost, written 1968, published 1978), a play that follows some of the ideas he had promoted in Court of Bactria. Having returned from a religious pilgrim, a local ruler has nightmares about his death and resolves to rule fairly but he gets lost in his own inefficiency and the opportunism of the people around him. The peasants, who have suffered the consequences of these failures, are also lost as some of them talk about leaving and some are determined to do things, but when it comes to acting, they get entangled in vicious circles of hypocrisy and fear. Talhak, one of Bayzā’ī’s wise fools, appears for the first time in this play, but Bayzā’ī suggests that he is as lost as the others as Talhak’s idea of justice is distorted by his limitations and personal obsessions. Notably, Bayzā’ī’s experience with the ban on Court of Bactria pushed him towards metaphorical suggestions rather than direct statements, which in this case make the play too vague.

His final play of this important period was Rāh-i tūfānī-i Farmān pisar-i Farmān az mīyān-i tārīkī (The Stormy Path of Farmān the Son of Farmān through the Darkness, written 1970, published 1972). Farmān, the last heir of a feudal family, is in love with a village girl who looks like an ancient queen. The play thus reflects on contemporary Iranian politics by demonstrating how the obsession with an overblown past can distract attention from what is at stake in the present and leave people at the mercy of colonizers and exploiters. The play’s ending is also interesting in that, in a symbolic twist, it reveals the setting to be a mental asylum. This choice echoes Sādiq Hidāyat’s short story Sih Qatrah Khūn (Three Drops of Blood, 1932), which also used the metaphors of love, belonging, and madness to comment on the failure of Iran’s cultural bid for nation building due to obsessive utopianism, psychopathic self-centredness, and lack of pragmatic worldliness.

With the atmosphere of Iranian theatre becoming increasingly polarised under the pressures of state censorship, the militant anti-state, religious, and Marxist movements of the late 1960s, and the leftists’ attacks on the performances that were deemed pro-state or not critical enough, Bayzā’ī ended his theatrical activities without saying goodbye to playwriting. Before making his first film, however, he wrote a children’s story, Haqīqat va mard-i dānā (Truth and the Wiseman, written 1970, published 1972), a tale of initiation which recounts the quest of a child seeking truth. The story contains the philosophical backbone of most of Bayzā’ī’s works: truth is temporary, multisided, contradictory, and ultimately impossible to define. The boy’s quest for truth ends in his return as a middle-aged man to his hometown where his parents no longer recognize him. He thus becomes a recluse that finds truth not in the sky or in great ideas but in the simple relationships and acts of love, work, and production that we take for granted. It is in everything and in nothing, in wandering around, planting, harvesting, and building, in being kind, curious, and soft or hard when the circumstances demand it. It is the reed that grows from the earth and can be turned into a lance, a pen, or a flute, but the ultimate wise person is the one who knows how to turn the lance into a flute, a pen, or a plant again. The book, illustrated by Murtizā Mumayyiz (1935-2005) and published by the Institute for the Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults, became a turning point in Bayzā’ī’s career as the Institute offered him the opportunity to make a film. The result was ‘Amū Sībīlū (Uncle Moustache), whose success meant that from 1970 until 1979 Bayzā’ī’s main preoccupation was making films and writing screenplays.

Figure 17: Book cover, Bayzā’ī’s Truth and the Wiseman (1972), illustrated by Murtizā Mumayyiz.

Bayzā’ī the Filmmaker and Screenplay Writer

1970-1973: From Uncle Moustache to Lonely Warrior, Downpour, and Lost

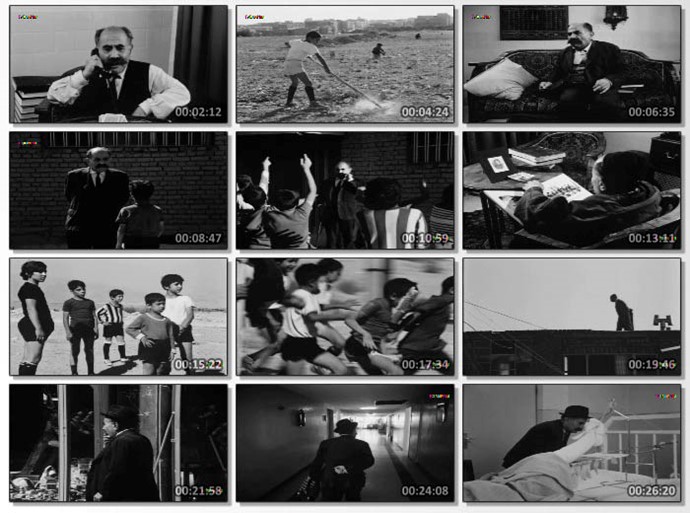

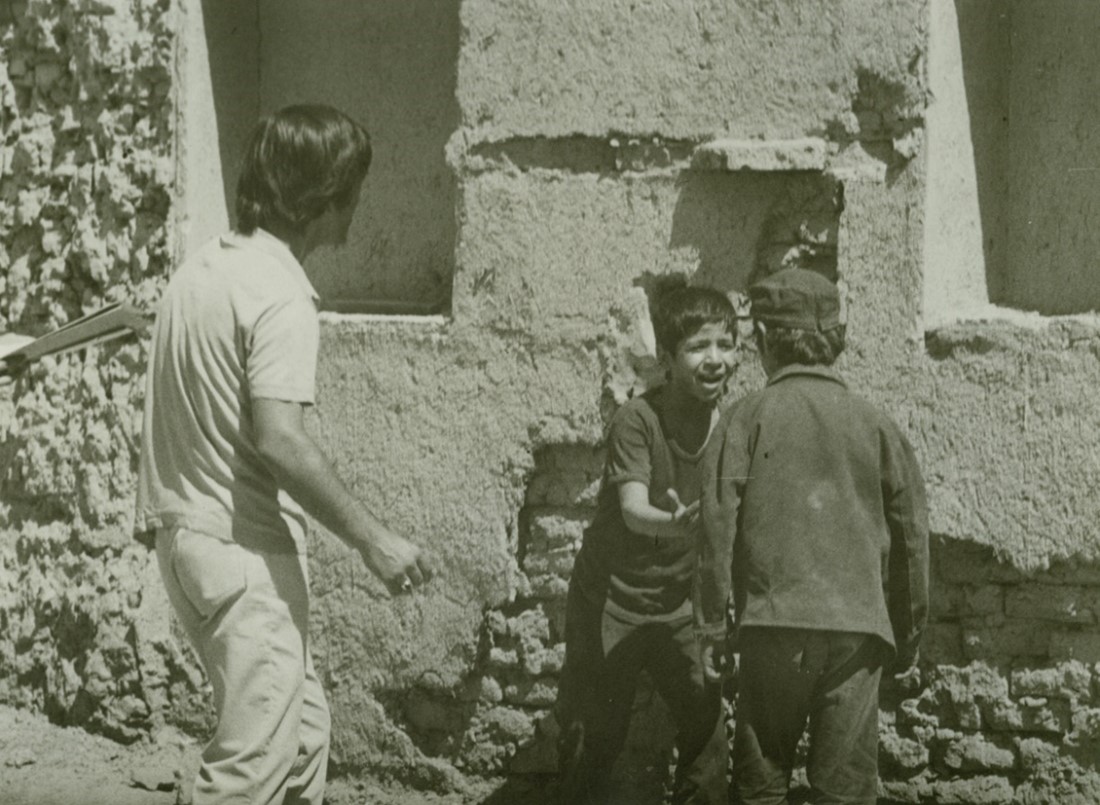

Produced by the Institute for the Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults, Bayzā’ī’s first film, Uncle Moustache (1970), comments on the at first rocky but eventually warm relationship between an old man and a group of local boys who turn the abandoned field in front of his house into a makeshift football (i.e. soccer) pitch. The man’s initial refusal to accept the boys’ rights to play in the field leads to a conflict which culminates in a chase scene in which one of the boys falls from a wall and is badly injured. This leads to the boys’ disappearance, but soon the man realises that he misses them, goes to visit the injured boy in the hospital, reconciles with him and the others, and changes some of his old habits. Thus, the film offers a perspective on the inevitability of change when the world has changed. The man’s frowning moustachioed face and his knife in some scenes, his judge-like religious cloak and cap in others, and his formal statesman-like suit in still others represent three types of violent and authoritarian masculinity which are ultimately replaced with a new one: the old man with hands full of food and a big supportive smile. Similarly, his obsession with the past, closed doors and windows, and old photos and books is replaced with the markers of a modern, polyphonic society: a world of smiles, flowers, food, games, and open doors where children freely move and engage in constructive activities.

Figure 18: Screenshots from the film Uncle Moustache (1970), Bahrām Bayzā’ī.

Notably, Bayzā’ī turns the boys’ refusal to take the man seriously and their demonstrations and actions against him into a carnivalesque site of cultural resistance against suppressive authority. He also uses taqlīd and taʿzīyah elements in his characterization of the old man whose rolling eyes, theatrical shenanigans, moustache, and knife depict him as a comic version of shimr-khān (the murderer) of ta‘zīyah plays or the babrāz-khān (vainglorious braggart) of taqlīd plays.27Babrāz-khān is also a villain in the romance of Husayn Kurd Shabistarī. For a summary of the romance, see Ulrich Marzolph, “Ḥosayn-e kord-e Šabestari,” in Encyclopaedia Iranica Online, https://iranicaonline.org/articles/hosayn-e-kord-e-sabestari. These qualities create a lively ambiance for and juxtaposition with a profound ritual of quest, purgation, and alteration. Bayzā’ī associates these elements with children’s rights and their ability to demand their needs to the ideals of a modern democratic society in which even those in power learn to derive their happiness from cooperating with others to engineer collective happiness, rather than use surveillance and violence to dominate others. The ending of the film, therefore, envisions a society in which “violence no longer determines what is right, and the free movement and the voices of the younger generation no longer annoys the old man.”28For more see Saeed Talajooy, “Bahram Beyzaie,” in Directory of World Cinema, Iran 2, ed. Parviz Jahed (Bristol: Intellect, 2017), 36. See also the chapter on Uncle Moustache in Talajooy, Iranian Culture, 71-90.

Figure 19: A Screenshot from the film Uncle Moustache (1970), Bahrām Bayzā’ī.

Like ‛Abbās Kīyārustamī’s early films, Uncle Moustache functioned as a predecessor for many post-revolutionary films in which children acted as protagonists. Like Bayzā’ī’s later films, Safar (Journey, 1973), Ragbār (Downpour, 1972), and Bāshū, Gharībah-i Kūchak (Bāshū, the Little Stranger, 1985), the film also turned the untamed, resistant gaze of children against undue impositions to reflect on how violence, the normalizing gaze, surveillance, advice, and threats are used to control people’s constructive curiosity and desire for change.

In 1970, Bayzā’ī also wrote Lonely Warrior (‛Ayyār-i Tanhā), his first screenplay on the Mongol invasion. As in his other historical screenplays, his emphasis is not on the evilness of the invaders but on the political and cultural failures, such as apathy, ignorance, hypocrisy, sycophancy, disunity, opportunism, and obsession with power, which leave people at the mercy of external invaders or turn local rulers into megalomaniac oppressors. As in his mythical plays, Bayzā’ī’s historical screenplays also aspire to create a history of unseen people by analogy. Lonely Warrior further employs ritual elements to break several clichés about heroism by recounting a story of fear, transformation, and ultimate determination. The protagonists, the daughter of a man of knowledge and a warrior ‛ayyār, are notably dynamic characters in this regard. In the beginning of the film, traumatized by the violence he has witnessed, the ‛ayyār is not beyond raping women and killing people when angry. He murders the man of knowledge who claims Iran will survive the Mongols’ onslaught and rapes his daughter thinking that she will be raped by the Mongols anyway. But the girl, now pregnant, has a strong sense of doing what needs to be done. Thus, she chases him and uses her resourcefulness to revive the caring man in the beast and turn the man and herself into the types of men and women who may fulfil her father’s prophecy, even though they may die in their encounters with the sandstorm of the Mongol army.

Figure 20: Book cover, Bayzā’ī’s Lonely Warrior (Ayyār-e Tanhā, 1970).

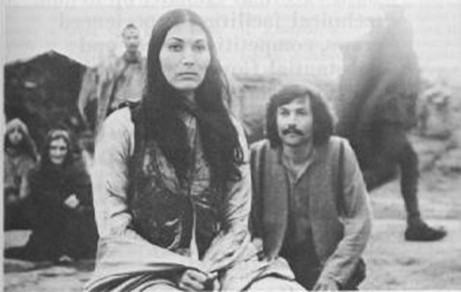

In 1971, having failed to find a producer for Lonely Warrior, Bayzā’ī commenced another full-length project that evolved into his first filmic masterpiece, Downpour (1972). With its length and seeming disunity, the film suggests the directorial position of a young filmmaker who wants to say it all. Despite this problem, however, the film was a brilliant debut which confronted mainstream Iranian cinema by subverting its main clichés. In the film, a well-educated young teacher, Mr. Hikmatī, enters a poor neighbourhood, falls in love with a hardworking young woman, ‛Ātifah, is irritated by his pupils’ unruly behaviour and his colleagues’ nosiness, realizes that his pupils need proper entertainment and cultural facilities, and refurbishes the school hall as a site for his pupils’ cultural activities. Ultimately, however, he is transferred at the request of the jealous headmaster who failed to make him marry his spoiled daughter.

Figure 21: A Screenshot from the film Downpour (1972), Bahrām Bayzā’ī,

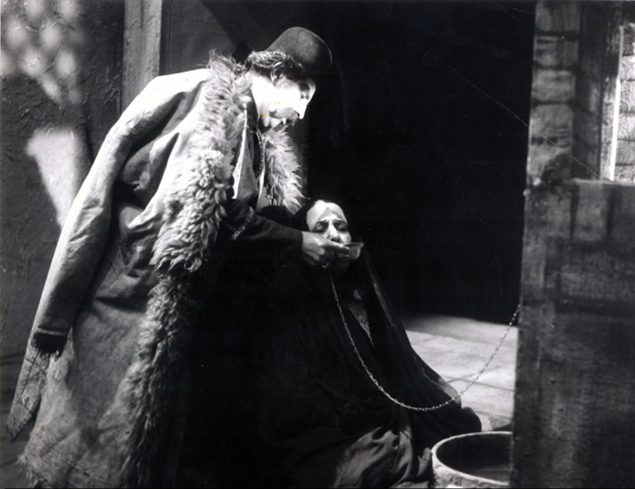

The film depicts the way personally and communally defined historical elements interlace with incidents in an individual’s life to form their identity and introduces the teacher, the prototype of intellectuality, as a protagonist competing with a thuggish butcher for the love of a girl in downtown Tehran. Bayzā’ī punctuates the lively comedy of resilience and hope with Kafkaesque motifs and encounters which gradually take over to create a tragedy of victimization and lost opportunities. This tragedy reflects the impossibility of positive action in a surveillance society where the success of an individual may threaten those who desire control by maintaining the status quo. Thus, the black-wearing man, dressed like a Shi’i mourner but wearing dark goggles, embodies both traditional and modern mercenaries who, like the black-wearing phantom in So Dies Pahlivān Akbar, act as instruments of tyranny and violence. Simultaneously, Bayzā’ī reformulates the tragic vision of ta‘zīyah by depicting Mr. Hikmatī as a sacrificial hero. Vicious cultural, political, or surreal forces distort the life of a creative intellectual who is propelled by his love for his students and a hardworking woman and his attempt to improve the lives of others.29See also Talajooy, Iranian Culture, 91-132.

Figure 22: A Screenshot from the film Downpour (1972), Bahrām Bayzā’ī.

Like Uncle Moustache, in Downpour the protagonist’s journey of individual growth, quest for belonging, and compassionate reconciliation with others occur due to his comically depicted encounters with naughty yet hardworking children who need guidance and facilities rather than punishment. Mr. Hikmatī’s journey is also intensified by his love for ‛Ātifah, a woman whose character suggests that together they can have a high potential for mutual growth, productivity, and constructive intellectuality. The teacher, therefore, comes to realize the important value of dedicated work and love for constructing a sense of identity and belonging. Downpour is also important at a self-reflexive level. For instance, Mr. Hikmatī’s rivalry with the butcher, Rahīm, for ‛Ātifah’s love proposes to replace the stereotypical “tough guy” of mainstream Iranian cinema with new types of protagonists. Indeed, in Downpour we see a female protagonist who is not just a simple love object or challenge for the male hero’s quest of initiation. Indeed, ‛Ātifah’s no-nonsense attitude, her sense of duty as the sole provider for her family, and her ability to choose rather than be won as a trophy play important roles in turning Mr. Hikmatī, a bookish man with little social experience, into a constructive intellectual who aspires to make himself a better person by serving his pupils.

Additionally, the film’s form combines the qualities of Italian neo-realism with taʿzīyah, taqlīd, and Iranian carnivalesque forms such as mīr-i nawrūzī (Lord of Misrule).30For Mīr-i Nawrūzī, see Saeed Talajooy, “Intellectuals as Sacrificial Heroes: A Comparative Study of Bahram Beyzaie and Wole Soyinka,” Comparative Literature Studies 52, no. 2 (2015): 382-83. Though reflected in the film’s general ambiance, this latter quality is central to the school hall scene in which Mr. Hikmatī’s students celebrate him as their champion in defiance of the headmaster who is planning to take credit for rebuilding the hall and organizing the performance. Another interesting quality of the film occurs in how meta-filmic images are produced by turning figures of speech into comic theatrical scenes and combining them with dialogue that reflect the similarity of life and cinema. Important among such scenes include: the boys’ shooting with a rented airgun at a target with Marisa Mell’s image on it; ‛Ātifah and Hikmatī’s date under the pupils’ cinema-like voyeuristic gaze; Hikmatī and Rahīm’s brawls and reconciliation; the dressmaker’s relationship with her imaginary customer; and Hikmatī’s funeral-like final departure which echoes that of “Jesus carrying his cross uphill to an inevitable fate.”31See Talajooy, “Bahram Beyzaie,” 37-38. See also Ragbār [Downpour], 00:21:00-00:22:00; 00:58:00-00:6100; 01:39:00-001:40:00; and 01:54:00-01:58:00. The version of the film I have used is the one renovated by the World Cinema Foundation in 2011, accessed January 15, 2021 via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5l8kLqkBYOo&t=1231s The conscious theatricality of these scenes creates performative Brechtian alienation moments that captivate the spectators and comment on both cinema and life itself as a form of performance.

Figure 23: A Screenshot from the film Downpour (1972), Bahrām Bayzā’ī.

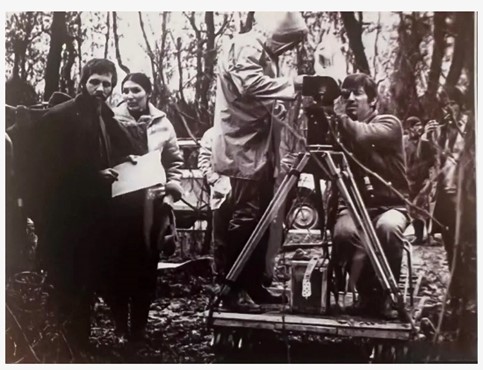

Upon the success of Downpour at the Tehran Film Festival in 1972, the Institute for the Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults approached Bayzā’ī for another film for children. The result was Journey (1972), a mythically charged film depicting two dispossessed orphans—the visionary Tāli‛ and the worldly and practical Razī—on a quest for belonging and identity, or even simply a secure home, a mother, and a family. Here Bayzā’ī’s metaphoric semiotics further evolve to generate a meticulous arrangement of the background images that turn a single journey into a cultural revelation. Like Huck in Mark Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (first published in the UK in 1884 and 1885 in the US) the film deploys Tāli‛’s visionary aspirations and Razī’s down-to-earth practicality to offer an overview of a world in dire straits. The society depicted in Journey is devoid of critical thinking, obsessed with imitating the status quo, beleaguered by cruelty and mass mentalities, apathetic to the fate of the marginalized, and organized by unwritten laws that prohibit the weak from doing things but do not protect them from the tyranny of abusive elites. The film’s background is filled with images of broken arches, sleeping old-fashioned labourers in demolished buildings, marching modern-looking robotic workers, mirrors, eyeglasses, film posters, billboards, scrap yards, and bewildered characters, suggesting a culture caught in the drift of a rapid transition in which imitative modernity is replacing medieval forms of life and art with little attention to the loss of their positive cultural components.32See also Talajooy, Iranian Culture, 133-154. In an era when cinema was preoccupied with lionizing tough guys as champions of heterosexual love and saviours of damsels in distress in films teeming with sexually evocative scenes, Journey offers something quite different and critical of these tropes. For instance, at one point in the film a paedophile thug chases Tāli‛ and Razī in a meta-cinematic scene in which, as they run through an area full of film posters, the paedophile thug literally dives through a poster of a nude actress in order to catch them.

Figure 24: Behind the scenes of the film Journey (1972), Bahrām Bayzā’ī.

Further, Bayzā’ī juxtaposes the realities of child labour and the violation of children’s rights and potential for growth with images of joyful children and women on billboards advertising Western commodities and the cold high-rise buildings that fail to function as a home for the two boys. Though at an archetypal level, this journey depicts a single failed quest in a vicious circle of multiple failing quests, the hardship motifs and the labour-like stages of the quest are orchestrated to critique the contemporary approach to modernization as being more obsessed with appearances than creating the actual necessities of grassroots development. Thus, the boys’ differences, and the vicious circle of desire, hope, action, and failure, generate a symbolic layer that associates their fate with the pitfalls of Iranian modernity. Razī, the craftsman, is swayed by the visionary Tāli‛ to embark on a quest to find Tāli‛’s parents with the hope that, once found, they may give the boys the chance of having a normal life. This dream, however, is doomed to fail. The utopia that they imagine cannot be achieved by top-down development or, even if achieved, the marginalized will not be the ones who reap its benefits. Nevertheless, their futile quest seems to be the only meaningful act in the ritualistically mechanical existence of the people around them. Burdened by ideas that block constructive curiosity, those around the boys allow perversion and violence against the weak and are obsessed with the mundane and imitative repetition of outdated or superficially modern conventions with no clear understanding of their roots. Thus, Bayzā’ī highlights the need for transcending the mundane to be able to examine our lives like a work of art with aesthetic contemplation, to see our past as a construct that must be critically examined. Nevertheless, the boys’ allegorical quest for a lost sense of belonging and a supportive family also suggests that even such visions may turn into fixations of reclaiming a mythic great past or finding saviours.

Figure 25: Behind the scenes of the film Journey (1972), Bahrām Bayzā’ī.

Journey’s technical qualities and dense metaphorical structure play significant roles in echoing Bayzā’ī’s former concerns and predicting the qualities of his later works. In its archetypal form, ritualistic motifs, and regional music, Journey predicts Bayzā’ī’s village trilogy—Gharībah va Mih (The Stranger and the Fog, 1974), Charīkah-yi Tārā (Ballad of Tārā, 1979), and Bāshū, the Little Stranger—which focuses on human experience at archetypal and existential levels but also comments on human relationships with nature, history, race, and nationhood. Journey’s surrealistic urban setting and ambiance, however, also reflect Bayzā’ī’s later use of noir elements in his city tetralogy—Kalāgh (The Crow (1977), Shāyad vaqtī dīgar (Maybe Some Other Time, 1988), Killing Mad Dogs (1999), and Vaqtī hamah khābīm (When We are All Sleeping, 2010).33I group these four films together because in all of them the city itself is a major theme, and they are all characterised by using noir filmic elements to reflect the sociopolitical positions and psychological conditions of middle-class families in a corrupt society. Further, the focus on orphaned children as the ultimate markers of social negligence and marginalization echoes the same theme in So Dies Pahlivān Akbar, in which Pahlivān Akbar’s fate is sealed when he is lost as a boy and suffers a lifetime of traumatic ostracization. However, it also predicts similar situations in The Stranger and the Fog, The Crow, Bāshū, the Little Stranger, and Maybe Some Other Time. In other words, though short, Journey is a key film in Bayzā’ī’s oeuvre and a locus of thematic and formal experimentation for his later works.

1973-1974: The Stranger and the Fog and Experimentation with Forms

In 1973, Bayzā’ī, who had been teaching at the University of Tehran since 1969, became a tenured professor at the University of Tehran where he led the Department of Dramatic Literature for several years. Bayzā’ī himself taught Iranian and Asian dramatic forms, and his presence was inspirational in enhancing his students’ creative potential, but he also invited writers such as Hūshang Gulshīrī and scholars like Shamīm Bahār to join him as contributors to the undergraduate and postgraduate modules on drama, literature, and play and film analysis. As a result, he played an important role in establishing the momentum that has made the department a bastion of creativity for Iranian performing arts ever since.

The following year Bayzā’ī completed The Stranger and the Fog (1974), his first village film. Like an agricultural spring festival, the film focused on the uncanny arrival, passions, and final departure of an agent of fertility while reformulating several Iranian mourning, marriage, initiation, and fertility rituals to create a new template for Iranian cinema. Unlike other village films of the era, Stranger is not concerned with clichés of villagers as innocent victims of cruel feudal lords or brave rebels who confront their rulers. Instead, Bayzā’ī creates a narrative that works at three levels of suggestiveness: realistic, existential, and archetypal.

Figure 26: A Screenshot from the film The Stranger and the Fog (1974), Bahrām Bayzā’ī.

A rough sketch of the plot is helpful here. A boat appears on the shore of a coastal village from beyond the fog. In it, the villagers find an injured man, Āyat, who is suffering from amnesia. Āyat tries to make a place for himself in the village by working hard and marrying Raʿnā, a single mother and the widow of the fishing hero of the village. When hunting a wolf in the forest, Āyat is attacked by and kills a man whom he later finds out to be Raʿnā’s former husband, Āshūb, who was assumed dead but had been hiding in the forest for the past year. He is also warned by two tall, black-wearing men who tell him that he has “been summoned” by the one who owns everything and insist that Āyat himself knows what the summons is for.34I have used a full version of the film which is about 138.5 minutes long. The scene occurs between 1:18:40 and 1:20:30. When Āyat finally feels that he has been accepted, the village is attacked by five towering, black-wearing men like the two who had previously warned Āyat that he had been summoned. Āyat slays all of them in a surrealistic battle scene in which, with each slaying, he also seems to be injured. Ultimately, believing that the village may be attacked again because of him, he decides to leave to discover what is beyond the fog. He gets on the same boat in which he was found and leaves injured and semi-conscious.

At its realistic level, the villagers are shown to be trapped in superstitious beliefs and their obsession with the afterlife and the unknown. Like Mr. Hikmatī in Downpour, Āyat is a stranger who wishes to be recognized for his positive qualities and to achieve a sense of belonging by serving the community. He aspires to be constructive and productive, an agent of fertility, and a reliable husband and father who can fish, plough, plant, harvest, make boats, help the weak, and cut trees to build houses. This realistic aspect reflects the political hierarchies of belonging and power in a microcosm in which tacit rules, surveillance, ostracization, and punishment are used to create docile subjects that must function exactly as the community expects them to. If individuals refuse the community’s rigid categories or try to change the rules, they must either define a major role for themselves by risking their lives and becoming heroes, or they are rejected as villains, idiots, or outcasts.

Figure 27: A Screenshot from the film The Stranger and the Fog (1974), Bahrām Bayzā’ī.

This revelation about Āshūb, and the fact that the villagers never realize that he had escaped and become a mugger, reflect the same template that Bayzā’ī used to question the validity of myths, official histories, or people’s beliefs about who is and who is not a hero in Ārash, The Eighth Voyage of Sinbad, and Journey. Thus Āshūb, whose name means chaos, is comparable to Hūmān in Ārash or the paedophile thug in Journey. Āyat’s encounter with the at first unknown man—the fallen hero, Āshūb—which leads to the latter’s death when he tries to kill Āyat, contributes to the archetypal suggestiveness of the film.

Figure 28: A Screenshot from the film The Stranger and the Fog (1974), Bahrām Bayzā’ī.

At this level of archetypes, Raʿnā can be understood to embody Isfandārmaz, the goddess of nature and fertility, while Āshūb represents a fake agent of fertility who has failed to stand by Raʿnā.35Spenta Armaiti (Isfandārmaz, [ripeness of mind and creative harmony]), is the female divinity associated with earth, mother nature, fertility, farmers and, more interestingly, the resurrection of the dead. For more, see, Mary Boyce, A History of Zoroastrianism. Vol. 1 (Leiden, New York, Köln: E. J. Brill. 1996), 206; Prods Oktor Skjærvø, “Ahura Mazdā and Ārmaiti, Heaven and Earth, in the Old Avesta,” Journal of the American Oriental Society 122, no. 2 (2002): 404-09. Further, Āyat functions like a dying and then resurrecting fertility god whose arrival, actions, and departure occur to end the anomaly that Āshūb’s actions have caused (i.e., his abandonment of his role as an archetypal agent of fertility and provider in the village). Āyat thus fertilizes the goddess (i.e., Raʿnā) and destroys the anomaly, but cannot stay as, like all dying gods, he must return to the unpredictable and unknowable underworld. This archetypal aspect is reflected first in Āyat’s unexpected arrival and the first glimpse that the spectators see of him in the boat. In this moment, Āyat looks reddish gray as if he is a clay effigy like those that were used in fertility rituals to embody Adonis, Attis, Osiris or Tammuz.36James George Frazer, The Golden Bough. A New Abridgement (London and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994), 331-374. Read also the whole section on “Killing the God,” 223-556. This colour symbolism is then reinforced in the fertility, purgation, initiation, marriage, passion, and mourning rituals in which Āyat plays a central role, as well as his white or grey shirt whenever he is in a state of transition. This archetypal function can most especially be seen in the sequence in which Āyat destroys the effigies that represent the villagers’ obsession with the afterlife, breaks the bull-headed scarecrow like a Mithraic hero, beats the ground until his body and face are covered in black mud, and then washes himself in the river to make himself recognizable to Raʿnā just before he discovers that she also loves him in return. Its final confirmation, however, occurs in the battle scene in which every time he slays an invader, he himself seems to be injured, too, and in each case, the villagers ritualistically push down the corpse of the invader into the mud in their farms as if to guarantee the fertility of their land. The same use of colour symbolism and archetypal imagery can also be seen in Bayzā’ī’s depiction of Raʿnā, whose costumes are initially all black but move to appear in shades of red and green when her fertility is highlighted, and white when she is in a state of transition.

Figure 29: A Screenshot from the film The Stranger and the Fog (1974), Bahrām Bayzā’ī.

Despite these archetypal echoes which evolve with the ritualization of action, the film’s realistic narrative problematizes Āyat’s final departure. His return to the fog suggests how an obsession with the unknown, religion, and the afterlife finally takes him over, and how such obsessions deprive people, including Āyat himself, of the chance to lead a positive, worldly life of togetherness and productivity. Simultaneously, these two levels generate a third psychological level, possibly indicated by the shadowy beings who pursue Āyat. Initially only appearing to him, they later invade the village and finally force Āyat to leave despite their deaths, and thus may well represent his Jungian shadows—the sum of the stifled emotions, desires, and traumatic experiences behind his mask of control and positivity.

According to Jung, “the less” the shadow “is embodied in the individual’s conscious life, the blacker and denser it is.” If issues are examined at a conscious level, they may be adjusted by being “constantly in contact with other interests.” However, if they are “repressed and isolated from consciousness,” they “burst forth suddenly in a moment of unawareness.” Thus, the shadow evolves into a pervasive “unconscious snag, thwarting our most well-meant intentions.”37Carl Gustav Jung, Psychology and Religion: West and East: Collected Works of C. G. Jung. Vol. 11, trans. R. F. C. Hull (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1969), 131. Āyat’s amnesia has stifled the shadows of his unknown past, but they finally arise as demonic projections that negatively impact his life and the lives of his loved ones. As in So Dies Pahlivān Akbar, therefore, the arrival of Āyat’s multiple Mr. Hydes, his uncanny doubles dressed in black, suggests that “Āyat’s dreams of belonging are threatened by nightmarish forms of condensation, displacement and secondary revision.”38See Talajooy, Iranian Culture, 133-154. See also Sigmund Freud, The Interpretation of Dreams, trans. James Strachey (New York: Basic Books, 2010), 147-158, 159-186, and 295-362.

Further, Stranger can also be interpreted on an existential level as Āyat, like all of us, comes out of the unknown, is exposed to social norms and pressures, and aspires to belong and to be recognized for his qualities rather than his past. Ultimately, however, he must leave for another unknown as his society and the embodied beliefs surrounding him, in the form of uncanny, black-robed invaders, do not allow him to fulfil his potential. He is disallowed from remaining with the woman he loves and with whom he could have made a better life for himself and others.

Figure 30: A Screenshot from the film The Stranger and the Fog (1974), Bahrām Bayzā’ī.