Resistance and Compliance in The Salesman (2016)

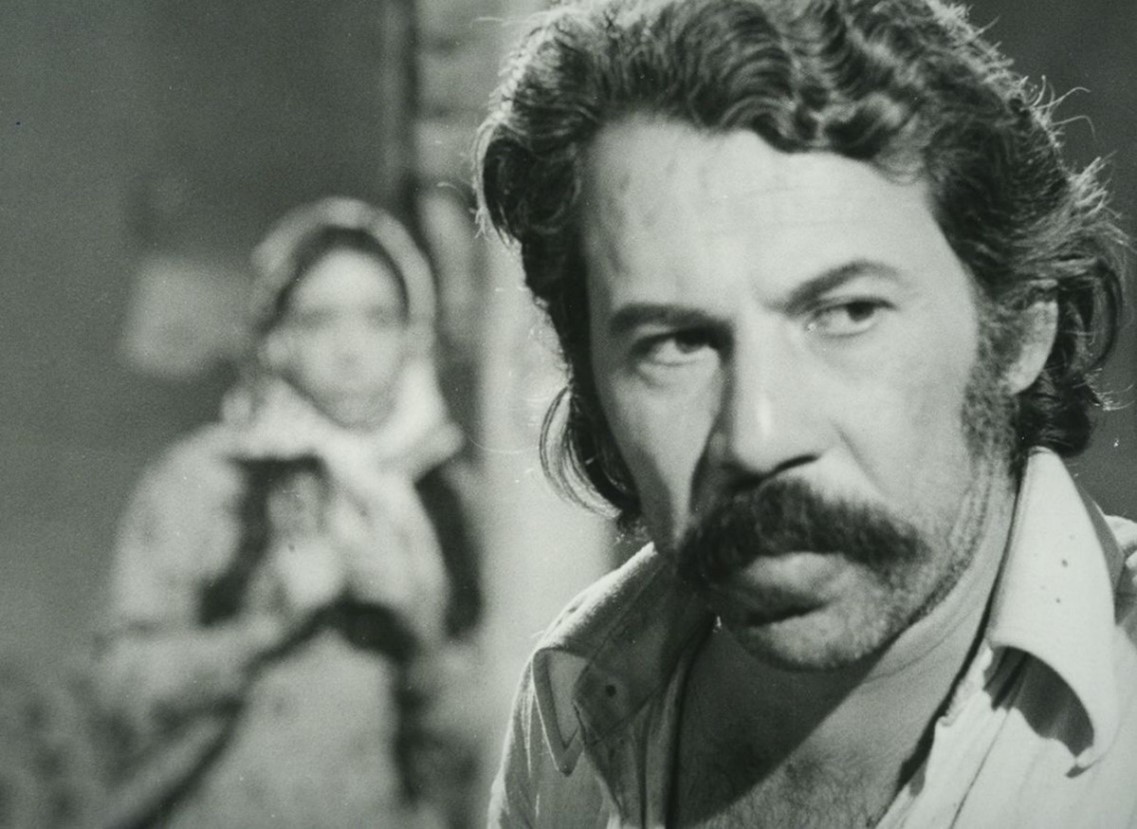

Figure 1: Poster of the film The Salesman, Asghar Farhādī, 2016

The Salesman (2016) is the seventh feature film of Asghar Farhādī, winning many international awards, including the award for Best Foreign Film at the Oscars and the award for Best Screenplay at Cannes. It was also the highest-grossing film in the domestic market.1For more on the film’s awards, see Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, “THE 89TH ACADEMY AWARDS | 2017,” Digital Magazine of the Academy Awards, February 26, 2017, https://www.oscars.org/oscars/ceremonies/2017; and “RETROSPECTIVE Year 2016: IN COMPETITION Feature Films,” Cannes Film Festival, https://www.festival-cannes.com/en/retrospective/2016/palmares/. Regarding its take at the box-office, see Zohreh Fathi and Pante’aa Khamooshi Esfehani, Statistical Yearbook of 1395. (Vice President of Technology Development and Cinematic Studies, 2016). Further, it can be argued that The Salesman is one of the most successful films in Iranian cinematic history, attracting both international and domestic markets. In fact, this new phenomenon of appealing to both markets can be attributed to Farhādī’s cinema in general; the reason for this could lie in the hybridity of his films, combining the aesthetics of Iranian art-house cinema and Hollywood’s more commercially successful melodrama features, as explained by Daniele Rugo.2Daniele Rugo, “Asghar Farhadi: Acknowledging Hybrid Traditions: Iran, Hollywood and Transnational Cinema,” Third Text 30, no. 3-4 (2016): 173-187. https://doi.org/10.1080/09528822.2017.1278876.

The Salesman is a curious case, however, even in Farhādīan hybrid cinema. On the one hand, the film narrates a ghayrat story—that is, a sexual assault-motivated revenge story—coupled with a mainstream plot line with a long history in an equally mainstream genre of film from pre-revolutionary Iranian cinema known as fīlmfārsī. On the other hand, The Salesman also exhibits a subversive attitude in its depiction of ghayrat and takes a critical tone with the genre. However, the film still carries many genre elements that distort or limit this critical or subversive approach. Moreover, the negotiations the film performs with and within the Islamic Republic censorship environment leaves many traces on the body of the film that prevents The Salesman from being read as entirely a critique or a purely subversive rendition of the genre.

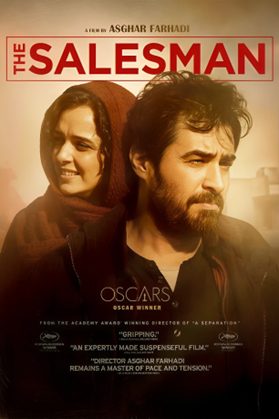

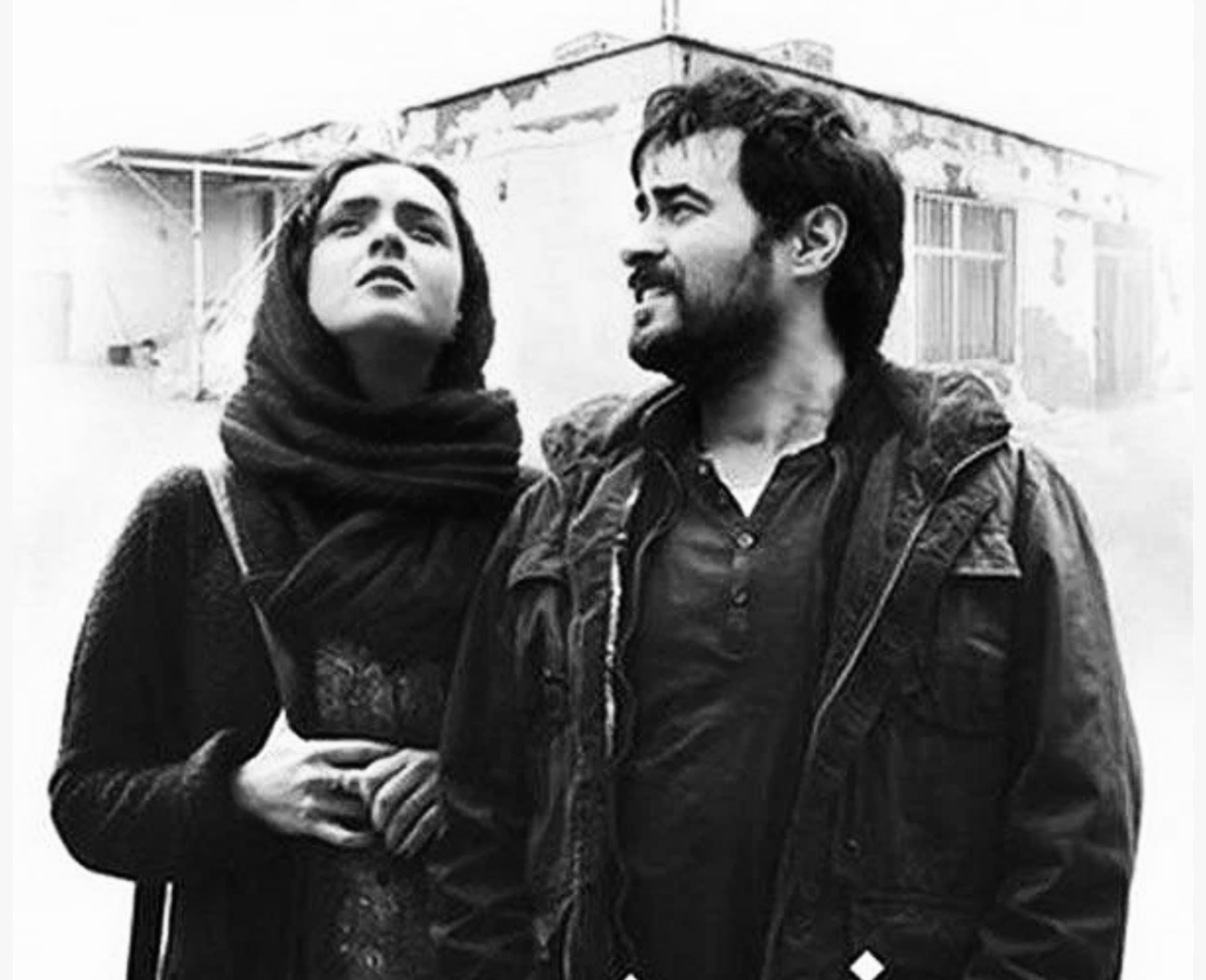

Figure 2: A Screenshot from the film The Salesman, Asghar Farhādī, 2016

In this study, I outline and examine the roots of the hybridity of The Salesman in the ghayrat stories of fīlmfārsī, and discuss how Farhādī simultaneously subverts and reinforces some of the normative notions presented in the genre. Alongside this, I also show how Farhādī’s negotiations with the Islamic Republic of Iran’s censorship systems work against the critique the film presents and reduce the extent of its potentially subversive “resistance.” However, before entering the film analysis, it is essential to discuss what ghayrat is and its significance in Iranian cinema.

Iranian Cinema and Ghayrat

Ghayrat is a broad category in Iranian society that affects Iranian cinema in numerous ways. Ghayrat is usually mistranslated into honour or jealousy but goes far beyond that. Defining ghayrat in all its shapes and forms is no easy task, however, and is out of the scope of this study. In short, “[i]n Iran, gheirat is an important concept in various domains of social life, including romantic relationships, family dynamics, and politics. People often refer to experiencing or expressing gheirat when there is a violation involving people or entities toward whom a person feels a strong connection and a tendency to protect.”3Pooya Razavi, Hadi Shaban-Azad, and Sanjay Srivastava, “Gheirat as a Complex Emotional Reaction to Relational Boundary Violations: A Mixed-Methods Investigation,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, . Ghayrat has numerous targets such as family members, religion, and country, and Iranians “have ghayrat over” these targets and “show, express, or elicit ghayrat” when the target is in danger or hurt. For example, a man has ghayrat over his wife, a sense of protectiveness. If his wife is insulted or hurt, he shows or elicits ghayrat to protect or avenge her. Ghayrat is usually accompanied by negative feelings such as anger.

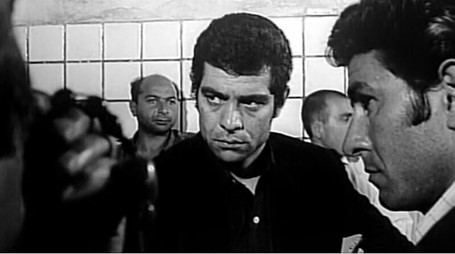

Figure 3: A Screenshot from the film The Salesman, Asghar Farhādī, 2016

For this study, however, distinguishing woman-related ghayrat and other types is important as I seek to narrow down what parts of ghayrat The Salesman comments on.

Following Maryam Falahatpishe Baboli and Farzan Karimi-Malekabadi who proposed modesty as the gendered element of ghayrat, I will specifically consider ghayrat through two of its broadest forms: “modesty ghayrat” and “non-modesty ghayrat.” Modesty ghayrat is the type of ghayrat that is usually aimed at nāmūs (a close female family member such as a mother, sister, or wife) that tries to control and protect her simultaneously. By controlling, a man asks (or demands) his woman family members to follow the rules of modesty and beware of situations in which immodesty can potentially take place. By protecting, the man acts as a bodyguard, fending off mate-poachers or those who would exploit and take advantage of (i.e., assault, often sexually) his women family members, especially in potentially immodest situations. Non-modesty ghayrat, however, is broad and can be elicited in many situations, such as defending the vulnerable, one’s country, religion, etc.

Before the Islamic Revolution, ghayrat, in both its forms, was one of the major, if not the most central, themes of a popular strand of films known as fīlmfārsī. These films emerged in the late 1950s and peaked in popularity in the 1960s and 1970s. The fīlmfārsī protagonists were almost always men, with attributes including javānmardī, an adjective referring to being helpful to others, a willingness to sacrifice one’s self-interests, protecting others, and so forth. Javānmardī can be translated to sportsmanship, and the individual practicing javānmardī is called a javānmard. Fīlmfārsī films with a major javānmardī theme were usually within the realm of non-modesty ghayrat. Because this type of ghayrat aims to protect the vulnerable in these films, it usually has positive outcomes in the stories, such as saving them.

However, modesty ghayrat was also considered a positive attribute in fīlmfārsī stories. The films were full of ghayratī men (that is, men with ghayrat) who helped others and restricted their nāmūs, requiring them to have hayā (that is, modesty). Within the subcategory of modesty ghayrat in fīlmfārsī , modesty and non-modesty ghayrat appear more like an indivisible continuum in a character. To some extent, it was and still is highly irregular to encounter an Iranian male character in a film who is protective of the people around him, takes care of the vulnerable, and is a javānmard but does not ask for modesty from his nāmūs.

This value system in fīlmfārsī was in direct opposition to modernism. As Pedram Partovi states, “filmfarsi titles often endorsed ‘traditionalist’ bourgeois interests, alongside the more ‘desirable’ aspects of the Shah-era modernist project, by depicting the protagonist’s willingness to sacrifice himself or his personal happiness to protect ‘honorable’ women and the ‘inviolable’ bonds of family and friends from morally dissolute and superficially Westernised middle-class antagonists.”4Pedram Partovi, “The Salesman (Forushandeh, 2016),” in Lexicon of Global Melodrama, ed. Heike Paul, Sarah Marak, Katharina Gerund, and Marius Henderson (Bielefeld: Transcript Publishing, 2022), 348. One of the reasons Amīr Hūshang Kāvūsī coined fīlmfārsī as a derogatory term was the genre’s propensity for upholding these values. He also thought these films followed no structure, story, or cinematic form.5Mu‛azizīnīyā, cited in Hamid Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema, Volume 2: The Industrializing Years, 1941–1978 (Durham: Duke University Press, 2011). In many films, ghayrat was defined as the virtue of the poor, who upheld Islamic values against the rich who had forgotten them and become Westernized. Ironically, these films were full of sex and violence, and Muslims and intellectuals such as Kāvūsī opposed them, calling them mubtazal (degrading).

Hamid Naficy categorises fīlmfārsī into two subgenres: the stewpot movie and the tough guy movie.6Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema, Volume 2. Stewpot films feature the javānmard protagonist who helps and saves people. Regarding ghayrat, these films focused on non-modesty situations. The tough guy subgenre featured the jāhil character who sought revenge to regain honor in woman-centered situations such as sexual assault. This second type was more focused on the modesty ghayrat, and jāhils were considered the emblem of ghayratī men.

The name of the stewpot sub-genre comes from a popular film in the era, Ganj-i Qārūn (Croesus’ Treasure, directed by Sīyāmak Yāsamī, 1965), in which in one memorable scene, Muhammad ‛Alī Fardīn, one of the most significant superstars of fīlmfārsī , ate stewpot while singing with other characters. He was the stereotypical fīlmfārsī javānmard who saves a wealthy man from drowning at the start of the film and teaches him the lifestyle of the poor.

Figure 4: A Screenshot from Ganj-i Qārūn (Croesus’ Treasure), directed by Sīyāmak Yāsamī, 1965

Qaysar (1969, directed by Mas‛ūd Kīmīyā’ī) is the most significant example of the tough guy genre. Although this film shares some characteristics with stewpot films, it introduces the jāhil character type. The ideology of these characters, which can be translated as “chivalry,” consists of a code of behavior that appeared in the first century of Islam (622-722 CE) in the Muslim regions of the Middle East. Some of the Muslims diverged from javānmard ideology and “adopted bravery, vigilantism, adventurism, and pleasure-seeking.”7Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema, Volume 2, 266. Therefore, one of the differences between the two main fīlmfārsī genres is the difference between the javānmard character type, as symbolized by Fardīn in stewpot films, and the jāhil character type, as symbolized in the character of Ghaisar.

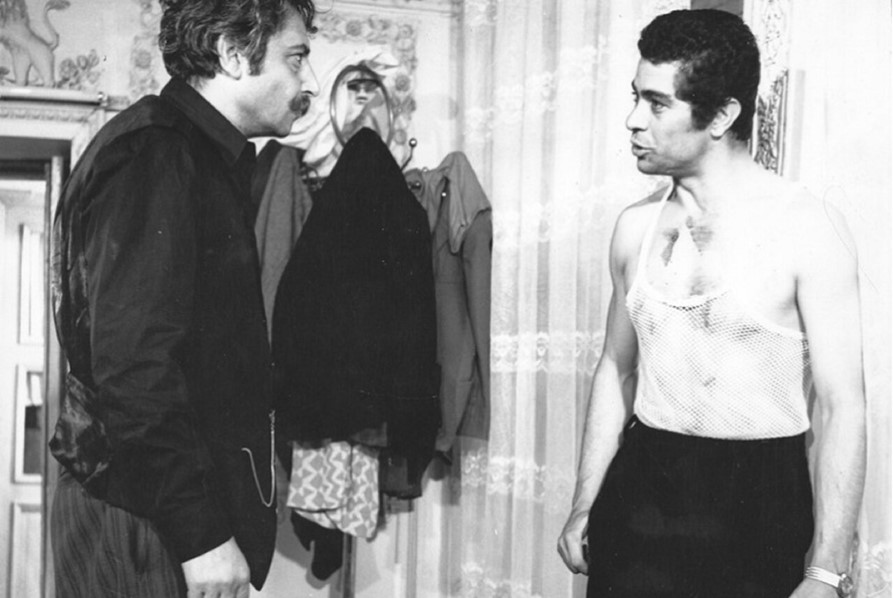

Figure 5: Qaysar (played by Bihrūz Vusūqī) in a screenshot from Qaysar, Mas‛ūd Kīmīyā’ī, 1969

In both these genres, women are portrayed stereotypically and as good women. As Naficy states:

[women] are expected to be self-sacrificing, obedient, decent, and compassionate. In general, they do not have an autonomous identity. Despite their ancillary status, women are the glue that keeps the family together, as they raise the children, manage the household, and forgive their men’s waywardness in the form of drinking, gambling, womanising, and rabble rousing with male buddies. Modernity and individuality, particularly those of women, pose a threat to family integrity, arousing male hysteria and panic.8Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema, Volume 2, 231.

One could argue that fīlmfārsī ’s portrayal of good women was the closest to the ideals of Muslim men in Iran: all sacrifice and no expectations, all submissiveness and no agency. The expectations of the tough guy genre exemplified by the jāhils—radical, male-oriented, honour-bound communities as symbolised in Qaysar—are perhaps as horrifying for women as they ever have been depicted in Iranian cinema to date.

In Qaysar, Fātī, the sister of the eponymous Qaysar, is raped by Mansūr. Mansūr refuses to marry Fātī, and she commits suicide. When Qaysar’s big brother, Farmān (played by Nāsir Malik-Mutī‛ī), comes to learn this, he goes after Mansūr and his brothers for revenge but they kill Farmān instead. Qaysar (played by Bihrūz Vusūqī) returns from a trip, also learns what has happened, and begins to take revenge for his sister and brother (and eventually his mother, too), murdering the three brothers one by one.

Figure 6: Qaysar’s big brother, Farmān (played by Nāsir Malik-Mutī‛ī) in a screenshot from Qaysar, Mas‛ūd Kīmīyā’ī, 1969

What is staggering and reveals its extremes is how modesty ghayrat operates as a justification for the sister’s suicide, considering her death as an act of honor; not because she desired to keep her family’s honor, but because she did not want to force her brother to murder her. In other words, it is normal and expected that if she did not commit suicide, Qaysar was expected to kill her, which would be an added burden to murdering the perpetrators. As Naficy states, “As befits the patriarchal system, the worried mother (Iran Daftari) is less concerned about the fate of her daughter than about the reaction of her sons to the rape, . . . Likewise, after reading the [suicide] letter … [her uncle] implies that had she not committed suicide, the brothers would probably have killed her to remove the dishonor.”9Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema, Volume 2, 186. The positive reactions to the film, not only by general audiences but also by critics, which persist in contemporary Iran today, are a telling indication of how modesty ghayrat continues to influence gender dynamics and operate in Iran. In a recent poll from Iranian film critics, Qaysar ranked as the 11th-best film in Iranian cinema history.10See “Bihtarīn film-hā-yi zindigī-i mā [Best Films of Our Lives],” Māhnāmah-i-Fīlm, https://film-magazine.com/archives/articles.asp?id=74.

Figure 7: A screenshot from Qaysar, Mas‛ūd Kīmīyā’ī, 1969

Further, Qaysar was by no means a single example of this. In fact, Qaysar can be understood as part of a larger, well-established sub-genre of fīlmfārsī in which “a family member (usually female) is wronged, forcing other members (typically male) to embark on a vengeful adventure.”11Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema, Volume 2, 232. Hamīd Misdāqī’s Rape (Tajāvuz, 1972), Nāsir Taqvā’ī’s Sadegh the Kurd (Sādiq Kurdah, 1972), and Sīyāmak Yāsamī’s Tehran Nights (Shabhā‑yi Tihrān, 1953) are significant examples of such ghayrat films. Most of these films, if not all, also depict modesty ghayrat as a specifically male phenomenon. This attitude persists in contemporary Iranian cinema, regardless of empirical data that show ghayrat as gender neutral.12For example, see Rasavi, Shaban-Azad, and Srivastava “Gheirat as a Complex Emotional Reaction”; Farzan Karimi-Malekabadi and Maryam Falahatpishe Baboli, “Qeirat Values and Victim Blaming in Iran: The Mediating Effect of Culture-Specific Gender Roles,” J. Interpers Violence 38, no. 3-4 (Feb. 2023): 2485-2509; and Mohammad Atari, Jesse Graham, and Morteza Dehghani, “Foundations of Morality in Iran,” Evolution and Human Behaviour 41, no. 5 (2020): 367-384. It was perhaps to some extent acceptable before the Revolution since many women were devoid of a voice in smaller Iranian towns and rural society or the downtown and the ghettos of cosmopolitan cities such as Tehran, where many of the fīlmfārsī stories took place. However, its persistence is particularly curious in contemporary Iran.

Figure 8: A screenshot from Rape (Tajāvuz), Hamīd Misdāqī, 1972

Since the rise of fīlmfārsī , Iranian cinema has mainly fixated on male characters in ghayrat-related stories. By male fixation, I refer to reserving the main point of view and the film’s main action for male characters in these stories. This fixation has resulted in the representation of women as marginalized in such narratives, relegated in their representation as saints or sinners in the all-too-common and, unfortunately, polarizing Madonna-whore spectrum. In other words, women characters were granted little to no space in the narrative to go beyond stereotypical representations. I importantly also use male fixation here in the sense that Iranian cinema has not evolved and developed in comparison to the increasing and contemporary agency of women in Iranian society. In today’s Iran, 97 percent of the population is literate, higher education has risen in recent years, and women are being granted more degrees than men. Iran is also one of the world’s leading nations regarding women university graduates in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM).13Atari, Graham, and Dehghani, “Foundations of Morality.” These data provide evidence concerning the increasing extent of women’s agency in Iranian society.

However, it is important to acknowledge that becoming educated and having more agency does not imply a complete break from religious beliefs like modesty ghayrat. In Iranian society, educated women and men might still believe in modesty ghayrat, and these two facts (i.e., education and belief in modesty ghayrat) are not mutually exclusive. In other words, access to higher education in universities granted more agency to women in Iranian society by affording them job opportunities, immigration options, the right to vote, and, consequently, independence; however, it did not necessarily eliminate their own or men’s belief in modesty ghayrat. For example, in the mentioned study about victim blaming and modesty ghayrat, most participants were middle-class (61.6%) and upper-middle-class (27.3%); however, many still believed in modesty ghayrat and blamed the victim in nāmūs killings.14Karimi-Malekabadi and Falahatpishe Baboli, “Qeirat Values.”

Although higher education and agency correlate, modesty ghayrat remains invariant to it. Thus, those with agency are expected to seek to implement and support their beliefs in society. Consequently, women with the belief in modesty ghayrat who did not have the agency to implement their beliefs in the system by finding agency and voice in Iranian society, especially after the Islamic Republic, joined forces with religious men in imposing modesty ghayrat. This might explain the role of women supporters of the Islamic Republic who are usually marginalized in discussions about women in Iran. It is generally assumed that all women are against the restrictions imposed on women in Iranian society. However, this is far from the reality.

In Iranian cinema, however, women are not represented as supporters of modesty ghayrat. Therefore, another issue embedded in the male fixation is that the perpetrators of modesty ghayrat are also mostly men. In this regard, Iranian cinema has, surprisingly and in contrast to its other failures concerning this issue, produced a collectively positive image of Iranian women who take little (if any) part in perpetuating this cultural violence, at least on screen.

After the Revolution, many of the modesty ghayrat storylines of the wronged woman category ceased with the new modesty censorship rules that restricted women’s portrayals. Therefore, considering Naficy’s four phases of the portrayal of women in Iranian cinema, in the first and second phases, ghayrat appeared mostly in non-modesty-related manifestations of it, and significantly in war films about the ongoing Iran-Iraq war where ghayrat was expressed for vatan (the homeland) and Islam. In the third phase, however, directors gradually brought modesty ghayrat back into their stories, specifically in family melodramas.15Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema, Volume 4: The Globalizing Era, 1984–2010 (Durham: Duke University Press, 2012)https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv11smr68. The four phases are “structured absence,” “background presence,” “foreground presence,” and “political criticism.”

Many veterans of Iranian cinema that were the remainder of the pre-revolution Iranian New Wave, such as ‛Abbās Kīyārustamī, Dāryūsh Mihrjū’ī and Bahrām Bayzā’ī, began to portray women with agency. These depictions are of women in control of their own lives who work hard to manage and balance their modern lifestyle with the modesty ghayrat orientation of Iranian society. Films such as Sara (1993) and Parī (1995), directed by Mihrjū’ī, Dah (Ten, 2000) by Kīyārustamī, Bāshū gharībah-yi kūchak (Bashu, the Little Stranger, 1989) and Sag Kushī (Killing Mad Dogs, 2001) by Bayzā’ī are among these films.

Bayzā’ī is a curious case among these filmmakers; two of his films, Ragbār (Downpour, 1972) and Sag Kushī, mark significant departures from the portrayal of modesty ghayrat in Iranian cinema. These two, made in pre- and post-revolutionary Iranian cinema, respectively, unveil two significant features of the treatment of modesty ghayrat in Iranian films through their defamiliarisation in story progression compared to other films.

Ragbār narrates the story of a love triangle between an intellectual, a lower-class woman, and a jāhil character type who, as previously discussed, is the symbol of modesty ghayrat in Iranian cinema. The film starts with a battle of modesty ghayrat as the intellectual falls in love with the jāhil’s lover. Initially, the jāhil character follows the stereotypical path and seeks revenge. However, the story develops so that all three become friends and the love triangle is resolved without violence. In fact, the love triangle is forgotten in the face of a broader dramatic event. Both the female character and the jāhil support the intellectual when the community, seeing danger in a man seeking reform, successfully banishes him. This is a radical approach in the history of Iranian cinema as it prioritises humanity and friendship over revenge and sexual concerns regarding nāmūs. In other words, Downpour exists outside the bounds of modesty ghayrat.

Figure 7: A screenshot from Downpour (Ragbār), Bahrām Bayzā’ī, 1972

Moreover, as mentioned, Bayzā’ī made another film in the post-revolutionary era, Killing Mad Dogs, that exhibits another significant departure from Iranian cinema. In simliar Iranian films that narrate a story of assault or sexual misconduct, if a woman is deemed responsible for the modesty ghayrat-eliciting situation, that woman is often eliminated from the narrative. This device differs from mere moral poetic justice as the elimination does not happen at the end of the story but around the time the “immodesty” has been revealed. For example, in Darbārah-yi Ilī (About Elly, 2009) by Asghar Farhādī, Elly cheats on her fiancé and dies in the middle of the narrative, even before the audience is notified of her cheating. Therefore, the narratives of such films structurally and systematically suppress the “immodest” women characters.

In others, especially films directed by men, if a woman is not directly responsible for a grave modesty ghayrat-eliciting situation, such as rape and sexual assault, again, that woman is often swiftly eliminated from the narrative. The reason could potentially be the Madonna-whore complex prevalent in Iran that blames the victim of modesty ghayrat situations, which turns the victim into an abject object. There is, however, a development in Iranian cinema. In many pre-revolution films, such as in Qaysar, the victim is physically removed from the narrative, either by suicide, murder, or by some other story device. In post-revolution Iranian cinema and specifically in the post-Green Movement, the women victims of modesty ghayrat-eliciting situations live throughout the narrative. However, in many of them, such as The Salesman, as I will discuss later in this paper, the women are not given space for their own arc of development or character growth separate from that of the men in the film and are almost entirely disallowed any sense of agency.

However, in Bayzā’ī’s Killing Mad Dogs, we see a powerful woman who wants to save her fiancée from prison. In the process, she is raped by one of her fiancée’s enemies, but the film remains focused on her and how she deals with the issue. Thus, Bayzā’ī stands alone as an exception to the filmmaking trends in Iran. The reason could potentially be his affinities with ancient Iranian religions and customs as opposed to Islam. Although Bayzā’ī lives in exile in the US, he remains a vocal critic of the Islamic Republic.

The new generation of filmmakers, following the previous generation, created two other strands of modesty ghayrat films in Naficy’s “fourth phase.” One strand can be seen in many mainstream commercial films influenced by Hollywood. These include narratives such as Qirmiz (Red, 1999) and Shām-i Ākhar (The Last Supper, 2002), both directed by Farīdūn Jayrānī, and Shukarān (Hemlock, directed by Bihrūz Afkhamī, 1999). These films deploy modesty ghayrat inside the framework of revenge narratives or stories of crimes of passion, full of hints concerning Islamically inappropriate sexual activities. The moral of these films is usually the same: women, and sometimes even men, who do not follow the rules of modesty must be punished, either logically in the story (e.g., revenge of the wronged) or via an accident interpreted as poetic justice. The Last Supper is a particularly curious case since it is one of the few films in which ghayrat is expressed by a woman. The narrative tells the story of a man who falls in love with his girlfriend’s mother. They marry, the girl expresses ghayrat and takes her revenge, murdering both her boyfriend and her mother.

Figure 8-9: Screenshots from The Last Supper (Shām-i Ākhar), Farīdūn Jayrānī, 2002

In the second strand, directors became critical of modesty ghayrat, viewing it as a means of perpetuating violence against women; a violence structurally embedded in Iranian society more broadly and within the religious modesty laws of the Islamic Republic more specifically.16Some of these films were hybrids of festival and commercial films such as those by Tahmīnah Mīlānī. Films like Tahmīnah Mīlānī’s trilogy, including Du Zan (Two Women, 1999), Nīmah-yi Pinhān (The Hidden Half, 2001) and Vākunish-i Panjum (The Fifth Reaction, 2003), and Dāyarah (The Circle, 2000) by Ja‛far Panāhī depict women who are victims of both patriarchal society and their own families. In these films, husbands and close family members, mahrams, are villainized as the main imposers of the widely accepted ghayrat violence against women.

This fourth phase also brought forth a wave of films about modesty ghayrat that altered the usual stories so that the main characters could now be the women victims themselves. For the first time, a body of films was produced in which stories were told from a woman’s point of view; women’s voices, emotions, thoughts, and experiences were shared on the Iranian screen as protagonists, not merely sidekicks. However, although this was a progressive development in portraying women, another issue was created. The reproduction of the victim archetype in many of these films persisted, especially in festival films but not exclusive to them, turning what should have been a positive development against itself. Ultimately, this unfortunate reproduction of the victim archetype transformed an otherwise progressive trait of these films into victim fetishizing.17This goes beyond the representation of women as victims and can be expanded to other topics such as class issues as well (i.e., fetishizing poverty, etc.). Here, I am referring to portrayals of women as mere victims in Iranian society by those who dismiss the fact that the imposition of ghayrat is not a mono-gendered or even gender-neutral phenomenon. As I have discussed already, those who impose modesty ghayrat in Iran are not only men but are, at least in part, also women.

Asghar Farhādī emerged as a director in the atmosphere of this fourth phase in which these two strands were successful in their own markets. His films, however, blended the features of festival and commercial films to create a hybrid cinema. Important to this discussion, the portrayal of women in this hybrid cinema remains one of its most significant features. On the one hand, unlike previous festival films and in line with commercial cinema, Farhādī tries to avoid fetishizing women as victims. On the other hand, following commercial cinema and contrary to festival films of the era, Farhādī follows the norms and morals of modesty ghayrat in Iranian society.18Note that I do not analyze Farhādī’s other films here, choosing instead to restrict this study to The Salesman in which modesty ghayrat is most evident. More could be said of these other films, of course, but I leave that to others. The following analysis of Farhādī’s film consists of two major parts, both explaining how the film aims to resist the imperatives of modesty ghayrat, yet also how its mainstream tropes and unavoidable negotiations with the system imposed by the Islamic Regime weaken the degree to which such resistance remains possible.

The Salesman and the Demasculinization of ‛Imād

The Salesman begins in an alarming situation. The film’s main protagonists, a married couple both working in the theatre industry, must evacuate their apartment after construction next door seriously damages the foundation of their building, threatening its collapse. Following this unfortunate event, the couple, ‛Imād (played by Shahāb Husaynī) and Ra‛nā (played by Tarānah ‛Alīdūstī), must look for a new apartment to stay in while their old one is being repaired. One of their friends and a fellow actor, Bābak (played by Bābak Karīmī), helps them secure a place on short notice. At one point during the first few days at their temporary accommodation while ‛Imād is out buying groceries, Ra‛nā mistakenly opens the door for someone else, believing it to be ‛Imād. When ‛Imād comes back, he sees drops of blood on the staircase. Ra‛nā is not home, and there is evidence of a break-in. He inquires from his neighbors about what has happened and is informed that Ra‛nā is in the hospital. Gradually, he is further informed by neighbors and hospital staff that she might be the victim of a sexual assault. Ra‛nā returns home with a bandage but is in good physical health otherwise, expressing her desire to forget the traumatic event.

Figure 10: ‛Imād and Ra‛nā in their new apartment, A Screenshot from the film The Salesman, Asghar Farhādī, 2016

However, ‛Imād slowly becomes filled with anger connected to modesty ghayrat and ultimately cannot forget about the incident nor can he let it go. After undertaking a semi-detective approach to what occurred, ‛Imād figures out that their new apartment was previously rented by a sex worker named Sharārah (whom the audience never meets), and that the perpetrator of the assault probably knew her and came to her old apartment for a personal matter. ‛Imād eventually discovers the perpetrator: an older man who is, in fact, a regular of Sharārah’s. Ra‛nā, unaware of ‛Imād’s sleuthing, is again faced with her perpetrator. The older man, the eponymous Salesman, has mistaken Ra‛nā in the shower for Sharārah, and figuring out his mistake, he flees the scene. ‛Imād, whose rage has been increasingly built up by ghayrat, is now faced with the prospect of a weak older man and decides to partially seek his revenge by calling the older man’s family. Ra‛nā disagrees with this plan, but ‛Imād goes through with it regardless. However, when ‛Imād encounters the older man’s family and realizes that they perceive him as a saint, he cannot in good conscious ruin the older man’s life. ‛Imād also learns that the older man suffers from a heart condition. Faced with this unappealing and unsatisfying target of his intended revenge, ‛Imād gives up on his original plan. Instead, he asks the older man to accompany him to a separate room and slaps him. The older man comes out and, facing his family’s surprise at the sound they heard, conceals the matter. However, when he descends the stairs with his family, he falls. His heart stops and—in all likelihood though we do not see this—he dies. Thus, ‛Imād inadvertently kills the perpetrator of his nāmūs. His ghayrat is satisfied, but his conscience and relationship with his nāmūs Ra‛nā are in jeopardy.

Figure 11: The older man with his family, A Screenshot from the film The Salesman, Asghar Farhādī, 2016

The Salesman has a classic plot with a three-act structure in which different forms of violence transform and morph into each other. The overall theme at work in the film centers on the conflict between individualism and collectivism in Iranian society regarding modesty ghayrat. In a society full of danger for women and threats to their privacy, dangers that the patriarchal structure does little to control or protect them against, what happens when a situation arises in which the danger becomes personal? How will society react to such a threat? Can a single person like ‛Imād individualize his reaction to the matter?

Three scenes in the first act specifically foreshadow what comes in the second. In the first scene, when the apartment is damaged by the construction next door and threatening collapse, an unmissable crack can be seen in the wall of the couple’s bedroom, foreshadowing the future attack on their privacy. In the second, ‛Imād sits next to a woman in a taxi who indirectly accuses him of abuse. While it is an accusation with no basis, this moment shows the extent of an understandable and pervasive fear of men by Iranian women. Finally in the third scene, ‛Imād’s co-star, an actress named Sanam, plays the role of a naked sex worker during rehearsal but does so fully clothed and also while wearing a hijab. She is laughed at by other members of the play for this and leaves the rehearsal in anger.

This third scene presents a particularly curious case in which the Madonna and whore archetypes of fīlmfārsī are crystallized together in one character. In ‛Imād’s co-star Sanam, we are shown a modest woman, wearing a hijab and fully clothed, playing the role of a naked sex worker—which sounds absurd to both of the co-stars, especially ‛Imād. This can be considered an indication of the inner psyche of Iranian Muslim men who cannot accept the combination of the whore and the Madonna in one character or person. Thus, if a woman becomes a whore in their eyes, it would be extremely hard for such men to accept her as a Madonna figure again. Importantly, this is exactly what happens to Ra‛nā in later scenes.

Figure 12: Sanam and ‛Imād rehearsing on stage, a screenshot from the film The Salesman, Asghar Farhādī, 2016

In addition to being an actor, ‛Imād is also an intellectual and a teacher. In the film’s first scene, we see him appear as a javānmard as he helps his neighbour’s disabled son out of the apartment building during the evacuation. In the mentioned taxi scene, his attitude is understanding as he explains to his students that women are being poorly treated in Iran and they have a right to be alerted about the possibility of sexual assault. Moreover, in scenes depicting his teaching at the school, he demonstrates his desire for a better type of education for his students by giving them books and films that they might not usually encounter or otherwise have access to in Iran. Finally, he is a radical reformist and tells his friend, Bābak, “I wish they destroyed this city with a loader and rebuilt it all.”19The Salesman, directed by Asghar Farhādī (2016, Filimo) 00:13:58. This and all further quotations from the film a translated by the author. To ‛Imād’s wish, Bābak replies cynically, “They did it once before, and this is the result,” hinting that the Islamic Revolution did nothing for Iran.

Despite all these attributes, after Ra‛nā is assaulted, ‛Imād inevitably—if gradually—becomes ghayrati and takes his revenge, a process thoroughly foreshadowed in the first act as I have described. Alongside his education, radical reformist belifes, and javānmardī attributes, this is also in sharp contrast to his earlier, outward opinions about ghayrat. For instance, when one of his students asks him how a man can become a cow, ‛Imād replies: “Gradually.”20The Salesman, 00:06:06. The student asks this question about the plot line of Gāv (The Cow, 1969) by Dāryūsh Mihrjū’ī, an adaptation of an absurd novella by Ghulām Husayn Sā‛idī wherein this transformation happens. In doing so, Farhādī wants the audience to understand that ‛Imād is saying that a ghayratī person is like a cow—a harsh criticism by the director through his character. Conversely, after the assault, ‛Imād refrains from exhibiting sympathy for his wife, which is unusual for a character introduced to us in the first act as one who helps others, argues for women’s rights, and refers to those who practice ghayrat as cows.21There is only one short scene in which ‛Imād shows sympathy. This is the shifting technique of Farhādī: the director portrays a character with specific characteristics and, in an instant, makes the character do the opposite of what was previously defined.

Figure 13: ‛Imād in his classroom at the school, a screenshot from the film The Salesman, Asghar Farhādī, 2016

In A Separation (2011), for instance, Farhādī introduces Nādir, a husband involved in a divorce and one of the main protagonists, as an honorable, moral person who then lies in the courtroom. The technique is not new; in many melodramas, the good guy turns out to be the bad guy, etc. The difference of Farhādī’s technique, however, is twofold. First, he applies his techniques on his main characters. Second, the shifting does not present itself as a twist in the narrative and begins, instead, as part of a process of moral degradation. To be sure, there is also a cynical undertone to this technique. As many of Farhādī’s protagonists are from an educated middle-class background, this shifting offers a way for Farhādī to critique modern Iranians’ morality as superficial and a sham. Thus, after ‛Imād’s shift in character following the alleged assault, it appears likely that Ra‛nā has become the whore in his eyes. In this way, Farhādī seems to point to a striking difference between theory (i.e., ‛Imād teaching his students that women deserve rights in Iran) and practice (i.e., ‛Imād’s lack of sympathy for Ra‛nā after the assault) among Iranian intellectuals. Although ‛Imād is presented to us at first to be a reasonable person, even a javānmard before Ra‛nā’s assault, afterwards, he gradually becomes filled with ghayrat and forgets his sensitivity. In this way, one could argue that the jāhil archetype of fīlmfārsī is attempting to take him over.

Moreover, in several scenes, their fellow middle-class neighbors push ‛Imād to express and show his ghayrat. In one scene, ‛Imād decides to forget the matter and begins mopping the floor to clean up the blood left after the assault. A woman neighbor sees him and states that she wanted to ask the cleaner to come take care of it, but thought that ‛Imād would want to call the police and use the blood as evidence. ‛Imād shares his desire to forget about the event and says, “Nothing has happened.”22The Salesman, 00:48:07. The woman neighbor informs him that if he had seen his wife naked on the floor, a sight that one of their male neighbors had seen, he wouldn’t say such a thing. This is a particularly interesting scene in which modesty ghayrat, as I have previously mentioned, is reinforced by a woman.23In many Iranian films, family members such as mothers and sisters expect modesty ghayrat but the difference here is that the woman is just a neighbor. In other scenes, ‛Imād’s male neighbors also push him by being overly supportive, promising him that they will give testimony to the police and to the court. One neighbor even promises to take revenge himself if he sees the guy.

The structural aspect of ghayrat (i.e., as a set of ideologies embedded in culturally specific violence in Islamic societies such as Iran) is mentioned in the film as the primary source of ‛Imād’s behavior. Western film reviewers did not understand this culture. According to Partovi, they “puzzled over the narrative focus on Emad’s ‘irrational shame at what the neighbors will say’ (Bradshaw 2017) rather than on his wife’s reaction to the attack.”24Partovi, “The Salesman,” 349. In a significant scene, Ra‛nā expresses regret, saying that if she had not picked up the intercom, these events would not have happened. ‛Imād responds that if it was that simple, Ra‛nā should go and tell this excuse to every neighbor they have. This emotional scene reveals the extent to which modesty ghayrat culture permeates their lives, a culture that pressures ‛Imād specifically and is the primary source of his obsession with the event. He does not want to be considered ghayrat-less and so finds himself stuck between modernity and tradition.

Figure 14: ‛Imād listens to the neighbors as they recount what happened to Ra‛nā, a screenshot from the film The Salesman, Asghar Farhādī, 2016

On the one hand, he is a modern intellectual who agrees with his wife not to prosecute Ra‛nā’s assailant and to forget the matter. On the other hand, the pressure of tradition and honor culture weighs heavily on his shoulders. In this way, the film seems to suggest that ghayrat itself is something that perpetuates violence in Iranian society, and that a person cannot simply just become “modern” and escape it. Farhādī thus points to two aspects of ghayrat in Iran. First, that ghayrat is undesirable and makes men illogical. Second, that ghayrat is embedded in Iranian society and is thus structural. As Akram Jamshidi and Shahab Esfandiary put it, “Farhadi’s protagonist has consistently been put at the junctures of morals and justice, though the significance of The Salesman is the confrontation of the individual ethics in contrast with the social morals.”25Akram Jamshidi, and Shahab Esfandiary, “Critical Readings of The Salesman in Iran,” Observatorio (OBS*) 12, no. 2 (2018), https://doi.org/10.15847/obsOBS12220181176. Even if ‛Imād wants to forget, as Ra‛nā desires, he cannot. He is expected to express and show his ghayrat.26In one scene, ‛Imād draws a cross as the Christians do but it is not clear if Farhādī is hinting that ‛Imād is not a Muslim, or if ‛Imād is joking since his action is followed by his laughter. Either way, it seems that Farhādī is saying that the problem is not the government and is not Islam; rather, society as a whole is the problem.

This bind is an example of “hegemonic masculinity.” In “Hegemonic Masculinity: Rethinking the Concept,” R. W. Connell and James W. Messerschmidt argue that the concept of “hegemonic masculinity” embodies “the currently most honoured way of being a man,” and it requires “all other men to position themselves in relation to it.”27R. W. Connell and James W. Messerschmidt, “Hegemonic Masculinity: Rethinking the Concept,” Gender & Society 19, no. 6 (2005): 832. Thus in Iranian Islamic culture, ghayrat is one of the most significant factors in being a man and upholding the normative structutres of gendered hegemony. Men have a choice to go against it, but they have to accept the consequences of humiliation and emasculation by the culture should they do so. In this sense, ‛Imād seeks to retain his masculinity by eliciting ghayrat. However, this hegemonic masculinity is combined with the concept of cultural, social, and political “schizophrenia,” introduced by Asfaneh Najmabadi.28Asfaneh Najmabadi, “Hazards of Modernity and Morality: Women, State and Ideology in Contemporary Iran,” in Women, Islam and the State, edited by D. Kandiyoti (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Palgrave Macmillan, 1991), 66. Najmabadi defines this schizophrenia as a situation for non-traditional Iranian women that would be labelled ummul (i.e., too traditional and close-minded) if they behaved traditionally, and jilf (i.e., is too loose) if they were modern.

Figure 15: A screenshot from the film The Salesman, Asghar Farhādī, 2016

For male characters that desire a more modern life and set of values such as ‛Imād, this schizophrenia also exists concerning their nāmūs (i.e., close female family members). If men become modern, they will become ghayrat-less. Indeed, “a man without ghayrat” is one of the harshest insults that can be thrown at a man in Iran. And yet, like the schizophrenic extremes for women of being either too closed-minded or too loose, if men uphold the values of tradition instead, they are considered “radicals.” As a result, Iranian men are stuck in the schizophrenic oscilations between tradition and modernity. In the case of the film, ‛Imād desires or must be a conflicted character: he is an actor taking part in a modern play while living in an Islamic culture and upholding its traditional values. This schizophrenia directly influences his doubt and distressed position after Ra‛nā’s assault. As a modern civilised man, should he take revenge as the culture dictates or forget the matter? Ultimately, ‛Imād chooses to be the ghayratī man, not to be modern or forget, and succumbs to hegemonic masculinity—and the film and Ra‛nā critique his actions and his adherence to this tradition. ‛Imād thus “performs” the role of masculine ghayratī to be considered a “man” by the Islamic culture in which he and Ra‛nā live. However, his performance is not convincing to anyone. Not only does he not receive whatever benefit he might have had from the image of being perceived as properly ghayratī because he cannot disclose what happened, but he also loses the respect of his nāmūs. He is not modern or traditional; if he were, one of these communities would respect him. As the Persian proverb goes, he “loses both heaven and earth.”

Figure 16: A screenshot from the film The Salesman, Asghar Farhādī, 2016

While ‛Imād’s predecessors (i.e., Qaysar) gained respect as they expressed and showed ghayrat and became timeless heroes for Iranian audiences when they took their revenge, ‛Imād achieves the opposite. Instead of becoming a hero, ‛Imād finds himself burdened by an accidental assault (and likely the death) of an elderly man; his relationship with his nāmūs is endangered; and his javānmard qualities are seriously questioned. While Qaysar showed his masculine courage by killing those who raped (or failed to prevent the rape of) his sister, ‛Imād is gradually demasculinized in the revenge process as he loses confidence, is unable to satisfy his modern wife, and imposes violence on the weak (such as the elderly man). More importantly, while Qaysar’s news of revenge could make headlines in Iranian Islamic society as a positive act, ‛Imād’s revenge remains a secret. In this way, those who continue to maintain the ideology of the very hegemonic masculinity that drove him to his criminal act in the first place will probably never even know about this traditional “masculine” act, and, consequently, will never accept him as a “man.” In the end, ‛Imād is not a savior but is himself a perpetrator. Thus, in The Salesman, modesty ghayrat as a masculine value is subverted and transformed into a destructive anti-value. In this way specifically, the film can be considered one of the most resistant works to the masculine culture of modesty ghayrat.

There is also another complementary resistance taking place in this film. As Connell and Messerschmidt rightfully state, masculine hegemony “works in part through the production of exemplars of masculinity (e.g., professional sports stars), symbols that have authority.”29Connell and Messerschmidt, “Hegemonic Masculinity,” 846. In Iran, a culture full of war celebrities, masculine sports stars, and cinematic archetypes such as the titular character of Qaysar, The Salesman has found a place in Iranian popular culture with its success in the domestic market. This may explain the anger of the radical right media toward the film. For example, Mas‛ūd Firāsatī, arguably one of the most influential film critics of the right-wing in Iran, attacked the film, stating that “In the final sequence, the camera is looking down [at] the old man (high angle shot), and Emad is standing over him. This means the invader is oppressed and the victim is the oppressor . . . Emad’s slapping on the man’s face makes the audience clap for the movie in Iran and brings Farhadi awards in international festivals because it is a symbol of Iranians’ violence and brutality.”30Mas‛ūd Firāsatī zs quoted in Jamshidi and Esfandiary, “Critical Readings.” From The Salesman onward, the collective cinematic, pop-cultural memory of male youth in Iran continues to carry and transmit modesty ghayrat through two symbols: not only the masculine hero found in Qaysar but also in the demasculinized anti-hero found in ‛Imād.

Figure 17: ‛Imād slaps the old man across the face, causing him to fall to the ground. A screenshot from the film The Salesman, Asghar Farhādī, 2016

The Limits of Resistance: Ra‛nā, Male Fixation, and the Sadomasochism of the Male Gaze

Although Farhādī’s film performs certain acts of resistance concerning the issue of modesty ghayrat, he fails to appreciate or uplift his main woman protagonist in The Salesman. Despite its various modes of resistance, the male gaze that The Salesman adheres to is well-aligned with the Islamic structure of Iran that has been in place since Qaysar. In The Salesman, Farhādī narrates a story of an assault on a woman, yet he does not grant that woman a space independent from her husband, the male and main protagonist. In this way, it is clear that the patriarchal structure of the narrative is chiefly concerned with the husband of the victim and not the victim herself. This is an extreme manifestation of the male fixation in Iranian cinema, which, as I have explained, can be traced back to fīlmfārsī . Ra‛nā’s fears, thoughts, and mixed emotions are only ever mentioned, and only in passing, in the presence of ‛Imād. Her inability to express herself otherwise is structurally limited in the film because she is not given a separate identity or space within the film to do so. ‛Imād and, through their identification with him, the audience, sadistically investigates her through cross-examination in a variety of scenes. Here, sadism can be seen to stem directly from modesty ghayrat, and several sadistic questions abound: Has she been violated? Is she a whore or is she a Madonna?

Ra‛nā hides some facts, is inconsistent in her recollection of events, and exhibits no desire for revenge. Therefore, the gaze that Farhādī exhibits and adheres to in this film is patriarchal, with little regard for Ra‛nā, the victim and the woman character upon whom the entire plot and narrative hinge. Thus, instead of having an active voice in the story, Ra‛nā serves as something more akin to a sidekick in a film that should, by rights, be considered her story. The most significant desire that she manifests is to forget the event—an understandable desire, given her situation. However, even in her desire to forget, she shows little agency. It is also worth noting that she expresses that it is important for her that they move from the apartment in which the assault occurred. However, although she can join the apartment hunting, for some unknown reason, she cannot do so without her husband, and so waits instead for ‛Imād. Between acting and work (and his detective work, hunting down the perpetrator), ‛Imād has little time to attend to the matter, thus lengthening Ra‛nā’s forced occupancy in the retraumatizing space of the apartment.

Figure 18: A Screenshot from the film The Salesman, Asghar Farhādī, 2016

Moreover, in an indirect act to forget the matter—which notably is the only scene when we see her without ‛Imād—Ra‛nā parks the car of her assailant outside their house (which has been kept as something like a hostage). This attempt leads to the perpetrator stealing back his vehicle, which ironically only fuels the modesty ghayrat of ‛Imād and in no way leads to forgetting the assault on Ra‛nā or the ongoing situation. This one, brief scene dedicated to her point of view reminds us that she does not discuss her situation with anyone: not with a friend nor with a close family member. Farhādī has designed the story such that he renders Ra‛nā as both isolated and virtually voiceless in many aspects.

Thus, it seems that the Madonna-whore complex exists here in this film, too, just as in fīlmfārsī. The film treats Ra‛nā as an abject object after the assault, much like Qaysar’s sister Fātī is treated. Although Ra‛nā does not die as Fātī does, her point of view is virtually eliminated from the narrative—a narrative that conceals her point of view from a public male gaze (the male audience). Without a space in the narrative to exhibit her emotions or to offer a rationale for her actions, Ra‛nā’s character is thrown (as opposed to transformed) from a “whore” into a “Madonna.” This can be seen, for instance, during the revenge sequence in which she does nothing to prevent the situation yet seeks to maintain her higher moral ground, judging ‛Imād. While, for example, it would be possible to free the older man or at least attempt to do so, Ra‛nā does nothing and, instead, remains judgmental. The extent to which Farhādī has taken away her agency in a ghayrat-eliciting situation is profoundly striking.

Figure 19: A Screenshot from the film The Salesman, Asghar Farhādī, 2016

This aspect of the portrayal of Ra‛nā that is in line with the male gaze of Iranian Muslims can thus be seen as a negotiation, not only with the Islamic Republic’s radicals but also with the Islamic structure of Iranian society in general. In this way, The Salesman can be viewed as a case of narrative violence, a film aligned, at least regarding Ra‛nā’s portrayal, with the operating sadomasochistic male gaze in Iranian cinema—a gaze that allows women to be touched on screen, but only violently.31For an examination of violence, touch, and gender in Iranian cinema, see Hamid Taheri, “The Pleasure of the Violent Touch in Iranian Narrative Cinema.” Quarterly Review of Film and Video (September 2023): 1-16. The violent Muslim male gaze that is widely in operation and in circulation throughout Iranian audiences that might be dissatisfied with ‛Imād’s actions in the film can thus find satisfaction with the depiction of Ra‛nā.

Cinematic Negotiations with Censorship and the State: The Art of Distancing

In Iranian films, elements of resistance to and compliance with the state—especially with state censorship laws regarding cinema—and the state’s dominant ideology can be found simultaneously. This contradictory presence of resistance and compliance is the result of a number of factors, including censorship notes given to directors and producers by the state, the fear instilled in filmmakers, self-censorship, and so forth.32For more on these factors of censorship in Iranian cinema, see Hamid Taheri, “Censoring Iranian Cinema: Normalisation of the Modest Woman,” Feminist Media Studies (March 2024): 1-14. In negotiations with censors, Farhādī tried to distance the critique of the modesty ghayrat portrayed in the film from controversial and sensitive issues in numerous ways.

First, as discussed, he virtually eliminated Ra‛nā’s, the main woman protagonist’s, point of view, which would have, arguably, made the sexual assault more graphic or at least more tangible. Second, in one scene, ‛Imād draws a cross as the Christians do, but it is not clear whether Farhādī is using this moment to hint that he is not a Muslim or that ‛Imād is joking. Nevertheless, it helps Farhādī to make a case against the claims of the radicals, enabling him to argue that The Salesman does not criticize Islam. Moreover, by avoiding direct depictions of the police and the judicial system throughout the entire narrative, Farhādī also distances the issues presented in the film from those individuals (e.g., police authorities) who embody the Islamic Republic and its laws (an effective but highly unlikely scenario, though it may be).33It must be emphasized how the absence of police and the justice system in the film is highly unlikely. First of all, even if we only examine the “reality” of the film itself, while the main characters may not want to prosecute the assailant, either the neighbors who found Ra‛nā or the hospital staff who treated her—or possibly both—would definitely have informed the police. Second of all, if a similar situation occurred in the real world, the involvement of police and the justice system would also be entirely likely, if not inevitable. Consequently, modesty ghayrat, even in this highly unique situation, is not treated as an issue directly related to the Islamic Republic or Islam. Furthermore, though modesty ghayrat is portrayed as destructive, its destructiveness is restricted to this highly unique situation in which the perpetrator is old and in ill-health (and outwardly respectable to his family and friends). In other words, the film’s approach, especially to modesty ghayrat, cannot be generalized. Finally, Farhādī makes the assault visited upon Ra‛nā so ambiguous that the extent of it is never clarified in the film. Thus, male Muslim censors, or the Iranian audience for that matter, are not provided with enough information to clearly decide whether the extent of pursuing and demanding the consequences of modesty ghayrat by ‛Imād would be acceptable. Taken together, this accumulation of significant and related elements in the film can be considered micro-injections of the Islamic Republic’s ideology into the film, the source of which may be conscious or unconscious on the part of Farhādī.

Figure 20: Asghar Farhādī with Shahab Hosseini behind the scenes of the film The Salesman, Asghar Farhādī, 2016

The combination of these ever-present micro-injections of the Islamic Republic’s ideology in the film, while at the same time maintaining the film’s status as participating in the intellectual cinema of resistance, may well be one of the key factors for The Salesman’s success in both domestic and international markets. However, it’s important to note that Farhādī’s negotiations with the Republic’s censorship system go beyond textual elements and can even be observed in his interviews. For instance, in response to ghayrat-related criticisms, especially by right-wingers (e.g., the Fundamentalists, a political party that Farhādī probably rightfully fears, or at least rightly feared at the time), he stated that “an atmosphere has been created to propose that it seems this film is in defense of not having ghayrat and forgiving a rape. It is not about that at all . . . It is about privacy, and it is discussed many times in the film . . . Here, ‛Imād’s privacy is violated, and ‛Imād tries his best to forget it. Still, he cannot because it is impossible.”34Asghar Farhādī, “Panj Muntaqid – Panj Pāsukh,” [Interview], 1395/2016. Translated by the author. Although, quite understandably, Farhādī clearly had state censors and specific Islamic radicals in mind, his interview is aligned with what is depicted in the film: the assault on Ra‛nā is overwhelmingly presented as a violation of her husband’s “privacy,” not as an attack on Ra‛nā herself as a human being. Interviews such as this one are thus an important part of the negotiations Farhādī had to conduct with and within the larger systems of Islam and the state, a type of negotiation that many festival directors, such as Ja‛far Panāhī and Muhammad Rasūluf, do not usually perform.35Which could potentially explain why their films are censored and they face imprisonment.

Figure 21: Asghar Farhādī with Taraneh Alidousti behind the scenes of the film The Salesman, Asghar Farhādī, 2016

These examples of compliance in the film are significant because numerous Iranian women are victims of modesty ghayrat in real, everyday life as the system and the dominant Islamic culture seek to either eliminate or minimize their presence in Iranian society, much like the male fixation embedded in this film’s narrative that marginalises Ra‛nā. The regime and wider Islamic society attempt to achieve this desire by imposing modesty rules. It thus can be argued that modesty ghayrat is the foundation for the modesty rules that govern women’s lives in Iran. Modesty rules are a set of laws and norms that restrict women’s appearance (e.g., forcing them to wear hijab) and behavior (e.g., expecting them to be good mothers and wives). These rules are so strictly defined that even showing some hair from under the hijab can render an Iranian woman “immodest.” Based on modesty rules, Iranian police and militia members can arrest and fine these “immodest” women. An extreme case in recent years was the murder at the hands of the morality police of Mahsā Amīnī, a twenty-two-year-old woman who showed some of her hair. Notably, this event ignited the Woman Life Freedom movement, which was essentially an uprising calling for Iranian women’s right to be “immodest” and not marginalised. Modesty ghayrat is also responsible for nāmūs killings in Iran (i.e., the killing of close female family members that have engaged in “immodest” acts). Modesty ghayrat culture, as influential as it is, perpetuates violence against women and marginalises them in Iranian society.

Through The Salesman, Farhādī proposes that we consider modesty ghayrat as a destructive set of behaviors and values that are both personal and collective. Yet he demonstrates this through the film without any apparent connection between ghayrat, Islam, and the Islamic Republic. Farhādī also represents this destructiveness of modesty ghayrat to us in a highly unique situation in which the perpetrator is a frail old man near death, the uniqueness of which keeps the narrative from expanding into other ghayrat-eliciting situations and thus keeps the film itself from becoming a commentary on ghayrat in general. Moreover, Farhādī also virtually eliminates the main woman character, emptying her of agency in the process. Taken together, all of these elements and readings of the film can be best understood as an intricate negotiation strategy that allows The Salesman to be considered both a form of resistance in Iranian cinema while at the same time remaining somewhat slippery regarding reactive censorship measures and criticisms of the radical right in Iran.

Cite this article

Abstract: Furūshandah (The Salesman, 2016) by Asghar Farhādī is one of the most successful films in Iranian cinema history, attracting both international festivals and domestic audiences. The film belongs to a strand of films that I call “ghayrat films,” originally emerging primarily in the late 1960s with the popularization of Qaysar (1969, Mas‛ūd Kīmīyā’ī) in Iran. Ghayrat is a broad Islamic concept; one major type being “modesty ghayrat” which primarily manifests in relationships between men and women. Specifically, ghayrat films can be considered a subcategory of revenge stories in Iranian cinema, where the revenge is provoked by the rape or sexual assault of a male character’s nāmūs (a close female family member). In this article, I argue that The Salesman provides an astute critique of modesty ghayrat as, unlike many of its predecessors such as Qaysar, it demasculinizes its vengeful male protagonist, ‛Imād. However, as the film itself is a hybrid, positioned between commercial cinema and art films, it cannot shake certain traditional elements that reduce the extent of this critique and its resistance. In Iranian cinema, there is a fixation on male characters in modesty ghayrat stories, which produces a distinct feature in such narratives. This male fixation renders the victim of the sexual assault—a character who is invariably a woman—an abject object, reducing her space, voice, and agency in the narrative. Thus, in this modern modesty ghayrat film, not only is the presence of Ra‛nā, the female protagonist, minimized in the story of her own sexual assault, but she is also disallowed virtually any type of agency. Thus, The Salesman’s male fixation, which limits the film’s claims of an absolute critique of or resistance to modesty ghayrat, stems at least in part from the negotiations between Farhādī and his film with the Islamic Republic’s male gaze-driven modesty censorship rules.