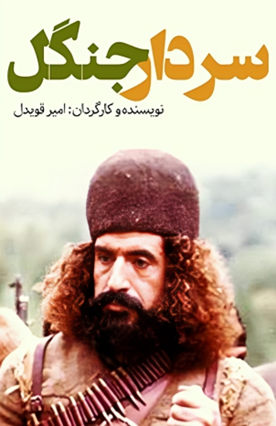

Gilan and the Jangal Movement: On Amir Ghavidel’s Sardar-e Jangal (1983)

Figure 1: Poster for the film Sardār-i-Jangal (1983), directed by Amīr Qavīdil.

Introduction

The Jangal movement is one of the important historical events of the twentieth century Iran, which had a significant impact on the intellectual and social currents of the country, both during its time and afterward. The movement has attracted both support and opposition. However, the Jangal movement should be examined within the context of its time, particularly from the perspective of why it occurred, in order to identify its causes. Iranian Intellectual class of the past century, in the aftermath of this movement, have expressed different perspectives on their approach to it. The Islamic Republic and leftists have viewed the movement positively, adapting its historical developments to align with their own principles, and using it to support their cultural productions. On the other hand, the Pahlavi regime and its supporters, both in the past and today, have depicted the Jangal movement as separatist, retrogressive and dependent on external forces. This perspective is evident in the works of those who supported the Pahlavi era and its advocates. However, from a historical perspective, the Jangal movement was neither a dependent nor a retrograde current, nor an ideological and revolutionary one in the modern sense of the word. The Jangal movement and its leader, Mīrzā Kūchak Khān, were political activists who, after the failure of the Constitutional Revolution—particularly the dissolution of the Second Majlis (Parliament) by the Russians—gathered in Gīlān with the support of the Democrats in Tehran to expel the Russians. They continued on the right path until 1919; however, the movement became entangled in the upheaval of World War I and the emergence of Bolshevism. Although the Jangal movement did not lean towards the Ottomans or Bolsheviks, it did provide an opportunity for the latter. Due to the central government’s weakness and the lack of an agreement with the Bolsheviks, the latter were willing to remain in Iran. However, based on historical documents and sources, it appears that the Jangal movement is better described as a national movement rather than an ideological one. Throughout the various challenges, this movement and most of its leaders, particularly Mīrzā Kūchak Khān, showed a stronger commitment to the principles of nationalism and Iranian identity than to any other ideology.

Figure 2: A photo of Mīrzā Kūchak Khān with his companions.

Following the Islamic Revolution, the Jangal movement emerged as a symbol of revolution and opposition to the Pahlavi regime. Two films were subsequently made as a result: Amīr Qavīdil’s Sardār-i-Jangal and Bihrūz Afkhamī’s television series Mīrzā Kūchak Khān. Qavīdil’s film covers the events of the Jangal movement between May 18, 1920 and December 2, 1921, including the Bolsheviks’ entry into Gīlān, the British retreat from Anzalī and Gīlān, the establishment of the provisional Revolutionary Government, the Red coup against Kūchak Khān, and the betrayal of Ihsānallāh Khān Dūstdār and Khālū Qurbān, as well as Haydar Khān ‛Amū-ughlī’s joining the Jangal movement, the Mullāsarā incident, the entry of Cossacks led by Rizā Khān into Gīlān and the confrontation between government forces and the Jangalīs, Haydar Khān’s execution, the movement’s breakdown and Kūchak Khān’s death from freezing in the Tālish mountains (Gīlvān).1Ibrāhīm Fakhrā’ī, Sardār-i Jangal, 11th ed. (Tehran: Jāvīdān, 1987).

The Background of the Study

Because of the subject’s historical significance, numerous books, articles, and lectures about the Jangal movement have been written and presented in Persian, Russian, English, and even Arabic. The movement’s primary sources and relevant studies are broadly classified into two time periods: prior to and following the Islamic Revolution. The majority of works were censored by the Pahlavi government prior to the revolution, and the topic was hardly ever discussed. This did not, however, prevent books about the Jangal movement from being published. It was during this period that some of the most significant memoirs and histories of the movement were published. Additionally, several memoirs of Jangalī fighters were written and published in well-known magazines during that time. However, until 1979, there were fewer books and articles about it that took an analytical approach. It goes without saying that some intellectuals and political leaders of the Pahlavi period, including Malak al-Shu‛arā Bahār, Sayyid Zīyā’ al-Dīn Tabātabā’ī, Mukhbir al-Saltanah Hidāyat, had a negative opinion of the movement and believed it was against Iran’s national interests, as evidenced by their memoirs and writings.2For Iranian figures’ view on the Jungle movement, see: Sadr al-Dīn Ilahī, Sayyid Zīyā’ al-Dīn, Sayyid Zīyā’, ‛Āmil-i Kūdatā (Tehran: Sālis, 2023), 418-422; Malik al-Shu‛ārā Bahār, Ahzāb Sīyāsī dar Īrān, vol. 1 (Tehrān: Amīr Kabīr, 1992), 159-177; Mahdī Farrukh, Khātirāt Sīyāsī-i Farrukh (Mu‛tasim al-Saltanah): Shāmil-i Tārīkh-i Panjāh Sālah-yi Mu‛āṣir (Tehran: Jāvīdān, 1969), 12-40; Mahdī Qulī Hidāyat (Mukhbīr al-Saltanah), Khātirāt va Khatarāt: Tūshah-ī az Tārīkh-i Shish Pādshāh va Gūshah-ī az Dawrah-yi Zindigī-yi Man, (Tehran: Zavvār, 1996), 318-321. Of course, some non-governmental opponents of the Jangal movement, like the well-known scholar Bahr al-‛Ulūm Qazvīnī, denounced the Jangal movement and Kūchak Khān, whom he described as a rebel with no purpose but to plunder.3Sayyid Muhammad Bahr al-‘Ulūm Qazvīnī, Mahdī Nūr Muhammadī, Tārīkhchah-yi Mīrzā Kūchak Khān: Ravāyatī Naw va Mutafāvit az Qīyām-i Jangal (Tehran: Nāmak, 2017), 45-75. However, following the revolution, the new regime’s emphasis on the Jangal movement and its new interpretation resulted in the release of a large number of written works about it, particularly in well-known magazines.4‛Abbās Panāhī, Ma’khaz Shināsī-i Tahlīlī-i Junbish Jangal (Rasht: Dānishgāh-i Gīlān, 2017), 15-19. Of course, many of these works are poor and superficial, written solely to glorify and promote the Jangal movement.

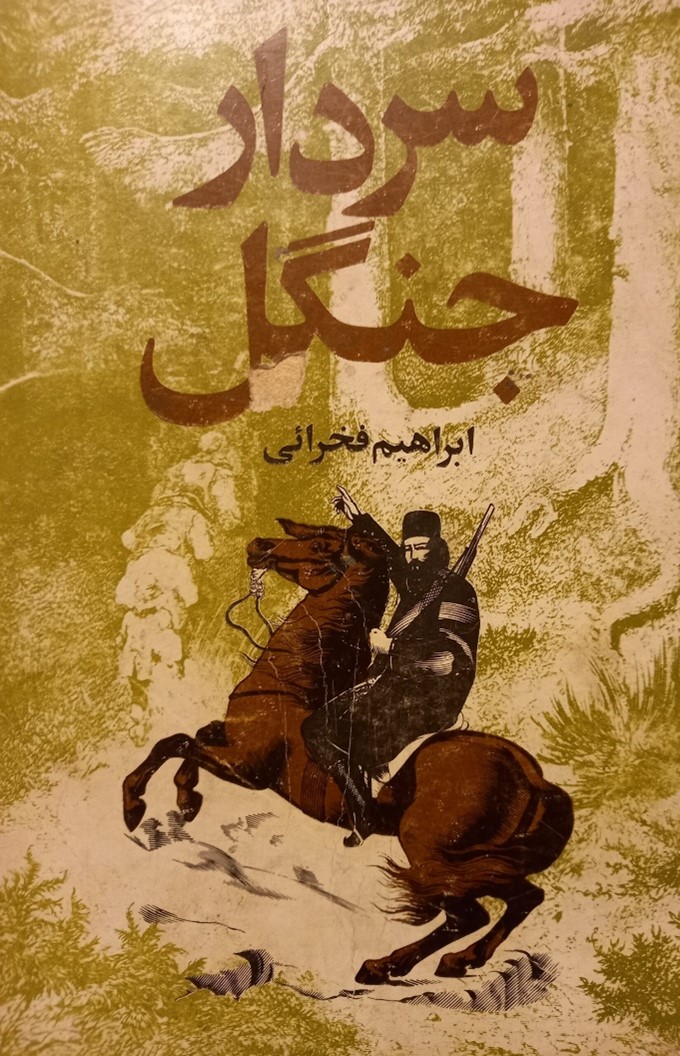

Figure 3: The cover of Ibrāhīm Fakhrā’ī’s Sardār-i-Jangal (1965).

The most famous book that made the Jangal movement well-known in Iran during the Pahlavi era and even after the revolution is Sardār-i-Jangal by Ibrāhīm Fakhrā’ī, which was written in the early 1960s, and was later adapted by Amīr Qavīdil for the screenplay of his film. Fakhrā’ī presents a story-like account of the historical events of the Jangal movement for his audience, using a captivating approach to praise the hero of his work, Mīrzā Kūchak Khān. He attempts to portray Kūchak Khān as a flawless and charismatic leader, without critiquing his behavior, actions, or military and political stances. Another major work that addresses the Jangal movement in the form of memoirs, yet with a modern historical approach, is Shawravī va junbish-i jangal (The Soviet Union and the Jangal movement) written by Grīgur Yaqīkīyān. It explores the developments during the final seventeen months of the Jangal movement, which coincided with the arrival of the Bolsheviks in Gīlān.5Grīgur Yaqīkīyān, Tārīkh-i Inqilāb-i Jangal bih Ravāyat-i Yak Shāhid-i ‘Aynī, ed. Burzūyah Dihgān (Tehran: Nuvīn, 1984). Also, Muhammad ‛Alī Gīlak’s Tārīkh-i Inqilāb-i Jangal (The History of the Jangalī Revolution) is an accurate and reliable account of the Jangal movement.6Muhammad-‘Alī Gīlak, Tārīkh-i Inqilāb-i Jangal (Rasht: Gīlakān, 1992). Among other works, Qīyām-i Jangal (The Jangal Uprising), the memoirs of Isma‛īl Jangalī, also contains valuable insights into the Jangal movement.7Ismā‛īl Jangalī, Qīyām-i Jangal, (Tehran: Jāvīdān, 1979). In addition, numerous scholarly works have been published in recent years regarding the Jangal movement. Khosrow Shakeri’s The Soviet Socialist Republic of Iran, 1920-1921: Birth of the Trauma offers a research-based account of the rise and decline of the Jangal movement.8Khosrow Shakeri, The Soviet Socialist Republic of Iran, 1920-1921: Birth of the Trauma (Pitt Series in Russian and East European Studies 21, Pittsburgh, 1995). In his article “The Populists of Rasht: Pan-Islamism and the role of the Central Powers in World War I Iran,” Pezhman Dailami provides significant analysis of the involvement of Bolsheviks, Ottomans, and Iranian and foreign agents in the Jangal movement. Drawing on important archival documents from various countries, Dailami presents a comprehensive and nuanced account that offers the reader a clear understanding of the role and function of the Jangal movement in modern history.9Pezhman Dailami, “The Populists of Rasht: Pan-Islamism and the role of the Central Powers in World War I Iran,” in Iran and the First World War: Battleground of the Great Powers, ed. Touraj Atabaki (London/New York, 2006), 137-62.

Sardār-i Jangal: A Synopsis

The film begins with the arrival of Bolshevik military and naval fleet at the port of Anzalī on May 18, 1920. The Red Army launched an assault on Anzalī with the objective of apprehending General Anton Denikin and neutralizing the White Russian forces aligned with the Tsarist regime. At the same time, a British army lookout tower is shown, where, despite the bombardment from the Bolshevik flotilla, no response is made, and the British forces ultimately decide to retreat. The Russian ships, however, do not target the British military barracks; instead focusing on destroying the villagers’ homes and other local locations. Subsequently, representatives of the Jangal movement welcome Admiral Raskolnikov and Sergo Ordzhonikidze. Kūchak Khān holds a meeting with them aboard the Kursk ship. During the negotiations, a nine-point agreement is reached, leading to the establishment of a provisional revolutionary republic in Gīlān.10Fakhrā’ī, Sardār-i Jangal, 243; Fakhrā’ī states that Mirza insisted on avoiding Marxist propaganda for some time, and believed that everyone should manage their own affairs independently.

Figure 4: A British army lookout tower from the film Sardār-i-Jangal (1983), directed by Amīr Qavīdil. Accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?app=desktop&v=DVZyozh0VXs (00:03:15).

Figure 5: Arrival of Bolshevik military and naval fleet at the port of Anzalī on May 18, 1920. Screenshot from the film Sardār-i-Jangal (1983), directed by Amīr Qavīdil. Accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?app=desktop&v=DVZyozh0VXs (00:12:15).

Later on, following the Red Coup against Mīrzā Kūchak Khān, he and his followers retreat to the forest. Prior to this, Mīrzā sends two of his associates, Mīrsālah Muzaffarzādah and Gauk the German, to Moscow to brief Soviet leaders on the situation in Gīlān. After the failure of the coup, Haydar Khān ‛Amū-ughlī, who was a member of the Iranian Communist Party, is sent to Gīlān to supervise the situation and assist the Jangalīs, and a new committee is formed.11For the eventful life of Haydar Khān and his role in the Jangal movement, see: Nāsir al-Dīn Hasanzādah, ed., Khāṭirāt-i Ḥaydar Khān ‛Amū-ughlī, bih khatt-i ‛Alī Akbar Dāvar (Tehran: Nāmak, 2019); Ismā‛īl Rā’īn, Haydar Khān ‛Amū-ughlī (Tehran: Badraqah-i Jāvīdān, 2023). However, Ihsānallāh Khān, a close ally of Kūchak Khān, is not involved in this matter. Khālū Qurbān, who had previously cooperated with the movement, turns against Kūchak Khān, marking the beginning of a period of conflict and fratricide.

One of the film’s most dramatic scenes centers around the Mullāsarā incident.12The village of Mullāsarā is currently a part of the central district of Shaft County and is located on the road from Rasht to Fūman. The film portrays that, due to Haydar Khān’s unilateral actions and his attempts to turn the commanders against Kūchak Khān, a meeting is held in Mullāsarā. Attended by Haydar Khān, Khālū Qurbān, and several others from the Jangalī forces, the meeting is soon interrupted when Mīrzā’s followers surround the house and set it on fire. Although the film does not directly mention Kūchak Khān’s involvement, the presence of his close associates among the besieging forces indicates that the attack was likely carried out at his behest. Fakhrā’ī also touches on this point in his book.13Fakhrā’ī, Sardār-i Jangal, 365. Ultimately, Haydar Khān is captured, while Khālū Qurbān is able to escape. This marks the end of the turbulent rise and fall of the Jangal movement. With internal divisions weakening the movement, the Cossack army, commanded by Rizā Khān, enters Gīlān to suppress the uprising. One of the final scenes of the film features Haydar Khān talking about the weapons he had brought with him to Iran. Upon hearing the sound of these weapons, he acknowledges that it was the sound of the guns he had brought from Russia to Iran. This moment highlights the Bolsheviks’ alliance with government forces and their betrayal of the Jangal movement. The final scene of the film depicts Kūchak Khān’s farewell to the Jangalī forces and the end of the Jangal movement. Kūchak Khān and a few of his associates head towards Khalkhāl to seek assistance from the leaders of the Shāhsavan tribe. The guide, Mu‛īn al-Ru‛āyā, surrenders to the government forces, and at the end of the journey, first Gauk and then Kūchak Khān succumb to the snowstorm, blizzards, and extreme cold. After the lifeless body of Kūchak Khān is found, Rizā Skistānī, under the orders of Amīr Muqtadir of Tālish, decapitates his body and first sends it to Rasht and then to Tehran.

Figure 6: Kūchak Khān in the snowstorm, blizzards, and extreme cold. Screenshot from the film Sardār-i-Jangal (1983), directed by Amīr Qavīdil. Accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?app=desktop&v=DVZyozh0VXs (01:13:55).

Depiction of the Jangal Movement and Its Leader, Kūchak Khān

The Jangal movement emerged as a movement aimed at resisting foreign influence and seeking independence in response to the turmoil caused by Russia’s ultimatum to Iran and Russian control over northern Iran, especially Gīlān. It was also a response to the disorder caused by World War I in Iran.14Afshīn Partaw, Gīlān va Khīzish-i Jangal (Rasht: Farhang-i Īlyā, 2012), 91-93. From an artistic perspective, the movement contains all the essential elements for creating and producing cinematic works. Moreover, in terms of narrative, the events that unfolded at each stage of the Jangal movement possess the potential to inspire the production of multiple films. Typically, the narrative of such historical films should be grounded in historical facts to some extent.

After the Islamic Revolution, the Jangal movement was deemed as a revolutionary movement, whose leadership and struggles were endorsed by the ruling power.15The leaders of the Islamic Republic have frequently referred to the Jangal movement as an anti-foreign movement in their speeches over the past four decades. In fact, they have made efforts to link their political, military, and ideological principles with the Jangal movement, while attempting to associate the historical roots of the Islamic movement in Iran with the Jangal movement, thereby creating a sense of ideological continuity. See “Nihzat-i Jangal: Yak Vāhid-i Mīnīyātūrī az Jumhūrī-yi Islāmī,” ISNA, 4/12/2023, accessed 23/12/2024, https://www.isna.ir/news/1402091308947/ Especially since the final months of Kūchak Khān’s life and the Jangal movement were tied to Rizā Khān’s actions in Gīlān, this issue became a significant and compelling matter for the Islamic regime, which opposed the Pahlavis. Furthermore, following the outbreak of the Iran-Iraq War and the escalating turmoil in the country, the need to strengthen the heroic spirit and patriotic fervor among the people and soldiers became more urgent than ever. Therefore, the depiction of national movements and resistance became one of the key themes in 1980s cinema, with the Jangal movement receiving significant attention. As a result, in the early 1980s, Amīr Qavīdil decided to make a film based on Sardār-i Jangal, focusing on Kūchak Khān’s character and the Jangal movement. The film was shot in Gīlān in 1983, depicting the second phase of the movement’s struggles, particularly its final months, from the arrival of the Bolsheviks in Gīlān to the ultimate fate of Kūchak Khān.

Sardār-i Jangal and the Question of Historical Authenticity

One of the key aspects of historical films is the degree of historical authenticity and the fidelity of the film’s script to actual historical events. In historical film projects, “the director’s role in visualizing and portraying events and individuals is much more significant than in other types of films; because the audience has not lived through or directly encountered the historical context or environment being depicted in the film.”16‛Alī Akbar Razmjū and ‛Alī Pāpī Sādiqī, “Bāznamā’ī-i Qīyām-i Tavvābīn dar ‘Majmū‛ah-i Tilivīzīyunī-i Mukhtār-nāmah’,” Faslnāmah-i Rādīyu Tilivīzīyun 22 (1393): 157-196. In the film Sardār-i Jangal, the filmmaker has made an effort to portray the historical events of the movement in a way that closely aligns with reality. However, the historical events depicted in the film are, of course, selective, and the director seeks to portray Kūchak Khān as a charismatic leader, attributing all his failures to the betrayal of other commanders in the Jangal movement. In certain crucial scenes of the film, Qavīdil deliberately avoids focusing on the key causes or individuals who played a role in the events. Instead, he opts to present the events in a more theatrical manner, emphasizing drama over historical accuracy.17One of the ongoing debates regarding the Jangal movement concerns the Mullāsarā incident and the underlying reasons for this event, as examined by opponents/supporters of the movement and scholars alike. Qavīdil despite depicting the event does not provide the motives behind this unrest. For further information on the Mullāsarā incident, see: Gīlak, Tārīkh-i Inqilāb-i Jangal, 493-499. If the director had included more thoughtful or well-developed dialogue in the scenes he focused on, it would have resulted in a more accurate representation of the movement.

In one of the opening scenes of the film, where Kūchak Khān arrives in Rasht, flags are seen waving among the crowd. While the three-colored flag featuring the Lion and Sun emblem was used throughout the movement, in this scene, the flag is shown without any emblem or insignia. Respect for the flag and Iran’s territorial integrity was consistently one of the fundamental principles of the Jangal movement.18Hādī Mīrzā Nizhād, ed., Rūznāmah-yi Jangal (Rasht: Farhang-i Īlyā, 1997), 2-3, 22, 28. One of the major weaknesses of the film is its failure to address some of the pivotal events that took place during the final seventeen months of the Jangal movement. These events include the activities of the Communists in Gīlān, particularly in Rasht, as well as the actions of the ‛Idālat Party against Kūchak Khān and the events that led to the Red Coup, the British conspiracies against the Jangal movement, Rizā Khān’s meetings with the Jangalī representatives, his correspondence with Kūchak Khān, inviting him to cooperate and unify the Jangal forces with the government’s military. The interaction between the Jangalī representatives and Rizā Khān could have constituted one of the key dialogues in the film, a meeting of which Muhammad ‛Alī Gīlak provides an interesting description in his book.19Gīlak, Tārīkh-i Inqilāb-i Jangal, 499. Gīlak refers to Rizā Khān as a strong and respected figure. This image may not have been favorable to the Islamic Republic, given the revolutionary context of the early 1980s in Iran; thus, the director deliberately avoided shooting this scene. In these discussions, Rizā Khān commends the actions of Kūchak Khān and underscores that the efforts of the Jangalī forces were aligned with national interests.20Gīlak was one of the two representatives of Kūchak Khān, who went to the Russian Consulate near Pul-i Īrāq, Rasht, to deliver Mirza’s letter to Rizā Khān. He writes about Rizā Khān’s response to Mīrzā: “Although there were rumors that Rizā Khān used offensive language toward people, no trace of such behavior was observed in his speech or actions. He even instructed his secretary to write the response to Mirza’s letter with a sense of respect and courtesy.” The reply was: “I, personally and on behalf of the Iranian government, affirm that all actions of the revolutionary forces of the Jangal movement have been in the interest of Iran and its people. You have provided valuable support during difficult times, protecting Iranians in your territories and safeguarding their lives and property from foreign interference. While you deserved to take control of the central government, the administration has now been entrusted to me, and I continue the same sacred movement. Therefore, it is necessary for you to transfer your responsibilities to me from this point onward.” See Gīlak, Tārīkh-i Inqilāb-i Jangal, 500-501. Rizā Khān and Kūchak Khān were on the path to a final agreement; however, the attack by the false Jangalī forces on the Cossack troops in Tulim, coupled with the discovery of a forged note from Kūchak Khān, bearing his seal and signature and allegedly intended to assassinate Rizā Khān, shifted the course of negotiations from reconciliation with the Jangalī forces to conflict and their eventual destruction.21Gīlak believes that spies carried out this action using Mīrzā’s seal and signature, seeking a confrontation between the government forces and the Jangalīs. See Gīlak, Tārīkh-i Inqilāb-i Jangal, 501. The film does not address any of these points.

Figure 7: Kūchak Khān arrives in Rasht. Screenshot from the film Sardār-i-Jangal (1983), directed by Amīr Qavīdil. Accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?app=desktop&v=DVZyozh0VXs (01:14:28).

In general, the film Sardār-i Jangal does not seem to meet the expectations of a historical film about a resistance movement and its leadership. While the director acknowledges some historical facts, he refrains from offering detailed insights into the political context, as well as the conditions and dynamics of the Jangal movement. Instead, the film adopts a narrative-driven, almost slogan-like view on the historical events surrounding the movement. This lack of attention to detail is also evident in the characterization of several key figures. The failure to fully develop the crucial characters of the movement prevents the audience from gaining a proper understanding of those characters’ roles, significance, and the unfolding of events.

Among these key and influential figures are Haydar Khān ‛Amū-ughlī and Gauk. The director provides little information about Haydar Khān’s political views and revolutionary background, which leads to this character being poorly understood by the audience. Gauk, on the other hand, suddenly appears in the story, despite his significant role as the last companion of Kūchak Khān during the march that led to his death. The film fails to establish the necessary context for Gauk’s introduction, and his relationship with Kūchak Khān is hastily conveyed through a brief dialogue, leading to Kūchak Khān’s sudden trust in him. The director’s portrayal of Gauk contradicts historical accounts and reflects Kūchak Khān’s naïve trust in him, whereas, in reality, Gauk is a highly complex character, and Kūchak Khān historically did not place much trust in him.22‛Abbās Panāhī, Rūykard-hā-yi Qudrat-hā-yi Buzurg bih Junbish-i Jangal (Rasht, Sipīdrūd, 2021), 65-67; Fakhrā’ī holds an admiring view of Gauk and refers to him as the close companion of Kūchak Khān. See Fakhrā’ī, Sardār-i Jangal, 386. There is no explanation or evidence for how he ultimately became Kūchak Khān’s loyal companion in the final days of the movement.

One of the key figures of the Jangal movement during its second phase is Mu‛īn al-Ru‛āyā (Hasan Khān Ālīyānī).23For more on the character of Mu‛īn al-Ru‛āyā Ālīyānī, see Shāhpūr Ālīyānī, Nihzat-i Jangal va Mu‛īn al-Ru‛āyā (Hasan Khān Ālīyānī) (Tehran: Farshīd, 2007). The significance of this person is comparable to that of Hāj Ahmad Kasmā’ī in the early years of the movement. Hasan Khān played a crucial role in the rise and fall of the movement, overseeing its logistics, securing financial resources, recruiting fighters, and ensuring other necessary supplies for the movement. The village of Zīdah in Fūmanāt, which was a part of Hasan Khān’s territory, played a significant role in securing financial and logistical resources for the movement during this period. Hasan Khān may have been involved in some of the unresolved issues surrounding the movement, such as the Mullāsarā incident, the murder of Haydar Khān, and other events in the final months, although there is little evidence to support these hypotheses. Anyway, aside from a few brief references to Hasan Khān, the film pays little attention to his character and his influence on the movement. In the film’s final scene, Qavīdil aims to influence the audience’s perspective, encouraging them to sympathize with his opinion. In this section, he explicitly attributes the failure of the movement to the negative actions of individuals such as Hāj Ahmad Kasmā’ī, Khālū Qurbān, Ihsānallāh Khān Dūstdār, and Mu‛īn al-Ru‛āyā. The director compares the decapitated head of Kūchak Khān to that of Imam Husayn, equating a highly revered religious figure in Shia Islam with a contemporary warrior and political leader. This comparison would introduce potential heresies into the religious beliefs of Shia Muslims. Despite the director’s attempt to portray the charismatic persona of Kūchak Khān, he consistently alludes to his mistakes throughout the film. Nevertheless, the story generally continues to move forward in praise of the leader of the movement. The final judgment of the film, along with the evaluation of the main characters—whose roles and actions are well-documented in historical records the director could have drawn from—is another flaw.

Figure 8: The moment when the Khān orders Kūchak Khān’s head to be cut off. Screenshot from the film Sardār-i-Jangal (1983), directed by Amīr Qavīdil. Accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?app=desktop&v=DVZyozh0VXs (01:25:12).

Artistic Aspects of the Film

A significant part of the appeal of spectacular cinematic projects, especially historical films featuring battle scenes, lies in the reconstruction of the battlefields. In Sardār-i Jangal, such scenes are all recreated using special effects. Qavīdil attempts to create a vivid and convincing portrayal of the environment for the audience through special effects or artistic techniques. Artistic effects hold a special place in the film industry and play a pivotal role in establishing the connection between the film and its audience. They present events and occurrences in a more realistic and meaningful way to moviegoers. The spectacular sequences in the film, which may include explosions, gunfire, fires, and other action scenes, as well as atmospheric effects like wind, rain, fog, and snow, form the foundation of the film’s visual narrative. These scenes are mainly executed by stunt performers, artists, cameramen, technical specialists, and model-makers.

Figure 9: Intense battle scenes. Screenshot from the film Sardār-i-Jangal (1983), directed by Amīr Qavīdil. Accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?app=desktop&v=DVZyozh0VXs (00:38:50).

Figure 10: Intense battle scene. Screenshot from the film Sardār-i-Jangal, (1983), directed by Amīr Qavīdil. Accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?app=desktop&v=DVZyozh0VXs (00:40:51).

However, the recreation of these scenes does not feel entirely natural or realistic, and in some scenes, viewers encounter weak depictions of war and conflict. This exposes a flaw in Sardār-i Jangal’s special effects, making it difficult for the scenes to fully engage viewers in the story. The natural landscapes in the film are a standout feature, offering a glimpse of the untouched nature and geography of 1980s Gīlān, which, in terms of its surroundings, architecture, and culture, closely resemble the period of the Jangal movement. At the time of shooting, the rural areas of Gīlān had not yet undergone significant changes in terms of architecture, culture, and economy, nor had urban developments expanded. The director, with a limited budget, was able to effectively utilize this geographical and architectural backdrop to produce the film.

Interactions Between the Jangal Movement and Ittihād-i-Islām (The Islamic Union)

One of the key intellectual pillars of the Jangal movement was the Ittihād-i-Islām Committee, which played a significant role in the movement’s intellectual circle. During the first phase of the Jangal movement (during World War I) and prior to Kūchak Khān’s agreement with the Bolsheviks and the establishment of the provisional revolutionary republic of Gīlān, the Ittihād-i-Islām Union, which later changed its name to the Ittihād-i-Islām Committee, was the central force and the mastermind behind the Jangal movement.24Fakhrā’ī, Sardār-i Jangal, 96. Although the Ittihād-i-Islām Committee was dissolved with the arrival of the Bolsheviks, it remained influential within the conservative faction of the Jangal movement and continued to shape part of its leadership. Therefore, since Sardār-i Jangal covers the period from the Bolshevik entry into Gīlān to the end of Kūchak Khān’s struggle, it does not address the interactions and relations between the Jangal movement and the Ittihād-i-Islām Union.25For Ittihād-i-Islām, see Dailami, “The Populists of Rasht,” 144-146, 160-162. Addressing this topic in certain scenes of the film could have highlighted the central role of individuals with this ideological orientation and their impact on the movement’s processes.

Confrontation Between the Jangal movement and British and Government Forces

Given the historical period depicted in the film, three forces were in confrontation with the Jangalī forces: The British, the Cossacks, and the Bolsheviks. The opening scene shows the arrival of the Bolsheviks and their confrontation with the British in the port of Anzalī. However, the film does not explore the British role, either militarily or politically, in much detail. During this period, the British formed a group known as Kumītah-yi Āhan (Iron Committee) with the aim of influencing Iran’s political affairs. This mysterious faction also established a group in Gīlān known as the “False Bolsheviks,” with the goal of discrediting the Jangalī forces and associating their actions with Marxist propaganda.26The Iron Committee (Zargandah Committee) was formed with British support in Tehran, after the dismissal of the 1919 agreement. Sayyid Zīyā’ al-Dīn Tabātabā’ī was its chairman, and its important members included: Mīrzā Mahmūd Khān Mudīr al-Mulk (Mahmūd Jam), Manūchihr Khān Tabīb, Mīrzā Mūsā Khān Ra’īs-i Khālisajāt, Mas‛ūd Kayhān. Malik al-Shu‛arā Bahār, Mīrzā Karīm Khān Rashtī, Mu’addab al-Dawlah, Sayyid Muhammad Tādayyun, Gaspar Īpikīyān. For more information, see Yahyā Dawlatābādī, Hayāt-i Yahyā, vol. 3 (Tehran, 1983), 143-150; Cyrus Ghani, Iran and the Rise of the Reza Shah: From Qajar Collapse to Pahlavi Power (London, 1998), 262-264; Husayn Makkī, Tārīkh-i Bīst-Sālah-yi Īrān, vol. 1 (Tehran, 1980), 81-83, 130-132, 250,295, 419, 498-537. The British actions played a key role in fueling public dissatisfaction with the Jangalī forces. However, in Sardār-i Jangal, this important issue is absent from the story, except in a scene where Mahdī Sarkhush, a commissioner of the Republic of Gīlān, briefly mentions it to Haydar Khān ‛Amū-ughlī.27Fakhrā’ī, Sardār-i Jangal, 332-334; Yahyā Dawlatābādī, Hayāt-i Yahyā, vol. 4 (Tehran, 1983), 152-154, 223-224; ‛Abdallāh Shahbāzī, Zuhūr va Suqūt-i Saltanat-i Pahlavī: Justārhā’ī az Tārīkh-i Mu‛āsir-i Īrān (Tehran: Ittilā‛āt, 2007), 75-85.

The confrontation between the Jangalīs and the government in the film is depicted from the moment Rizā Khān arrives in Gīlān. Consequently, tensions and conflicts between the Jangalīs, Kurds, and Russians reached their peak, and Rasht, along with its surrounding areas, fell into insecurity and chaos. This situation provided Rizā Khān and the government forces with the perfect opportunity to suppress the Jangal movement, which was now at its weakest. Khālū Qurbān, having witnessed the movement’s endless struggles and growing weakness, surrendered to Rizā Khān, along with Husayn Judat and the Kurds under his command.28Khālū Qurbān, along with Hājī Muhammad-Ja‛far Kangāvarī, went to Rizā Khān. See Fakhrā’ī, Sardār-i Jangal, 372. A significant portion of Rizā Khān’s efforts to prevent the outbreak of war is not portrayed in the film, despite being explicitly detailed by Fakhrā’ī in his book.

Additionally, the director does not address the meetings and negotiations between the Jangalī representatives and Rizā Khān, his correspondence with Kūchak Khān, in which he invited him to form an alliance between the Jangli forces and the Cossack troops to capture Tehran and stage a coup against Ahmad Shah Qājār, the 48-hour ceasefire agreement, the confrontation between the government forces and the Jangli forces in Māsūlah during the ceasefire, or, subsequently, Rizā Khān’s order for a large-scale offensive against the Jangalīs.29Fakhrā’ī, Sardār-i Jangal, 375-381.

Figure 11: The confrontation between the Jangalīs and the British and Iranian government forces. Screenshot from the film Sardār-i-Jangal (1983), directed by Amīr Qavīdil. Accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?app=desktop&v=DVZyozh0VXs (00:44:13).

Jangalī Forces and Their Interactions with the Bolsheviks

By watching the film, we can conclude that it is essentially based on the relationship between Kūchak Khān and the Bolsheviks. The nature and details of his interaction with the newly established Soviet government, namely the Bolsheviks, form an important part of the film’s structure. With the arrival of the Red Army in Anzalī on May 18, 1920, and Russian attack on British installations, the British forces withdrew without any resistance.30Gīlak, Tārīkh-i Inqilāb-i Jangal, 267. The Bolsheviks justified their invasion as a response to the presence of the anti-revolutionary forces of General Denikin. However, the British had sent Denikin to Baghdad to avoid Bolshevik attacks, and the Bolsheviks were well aware of this. In fact, this claim was merely a pretext to justify their invasion and occupation of Gīlān.31Nāsir ‛Azīmī, Ravāyatī Naw az Junbish va Inqilāb-i Jangal (Tehran: Zharf, 2015), 75-77; After the Bolsheviks occupied Gīlān, they justified their continued occupation of the region by blaming the ongoing British presence in Gīlān. They left Gīlān only after the British withdrew and when the central government suppressed the Jangalīs. See Ghulām-Husayn Mīrzā Sālaḥ, Junbish-i Mīrzā Kūchak Khān banā-bar Guzārish-hā-yi Sifārat-i Ingilīs (Tehran: Tārīkh-i Īrān, 1990), 2. The actions of the Bolsheviks, especially the Iranian Bolsheviks in the coup against Kūchak Khān, show that they had come to establish themselves there. This indicates that the Bolsheviks, sharing the same goal of global expansion that the Tsars had pursued in Iran, had set their sights on the country. However, this time, circumstances were not in favor of the Russian Bolsheviks. Following the arrival of the Bolshevik forces in Gīlān, Kūchak Khān was informed that the commander of the Red Army in Anzalī had requested a meeting with him in order to secure his approval for cooperation against British influence in Iran.32Aḥmad-‘Alī Sipihr, Īrān dar Jang-i Buzurg (Tehran: Pizhvāk-i Kayvān, 2016), 235. Despite Kūchak Khān’s opposition to the presence of any foreign political or military forces in Iran, he had no choice, as he was faced with a fait accompli. The unwelcome guests had already entered Gīlān by force. Meanwhile, the ‛Idālat Party (the Communist Party of Iran) in Rasht was actively promoting communist ideology.33Partaw, Gīlān va Khīzish-i Jangal, 287-291. Therefore, Kūchak Khān decided to take advantage of this situation for his own goals and benefit from the support of the Bolsheviks against the British and the Cossack forces. Thus, he went to Anzalī and negotiated with the Red Army commanders aboard the Kursk ship. During the negotiations, one of his conditions was the Russian guarantee of Iran’s independence and the Bolsheviks’ commitment to refrain from propagating communist ideology in Iran. The Bolsheviks seemingly accepted his conditions, but in practice, they continued with their own policies. Kūchak Khān’s approach is evident in all the scenes of the film. However, the Bolsheviks’ disregard for Kūchak Khān’s demands, as well as for the Jangalī forces, along with Russian operations to promote Bolshevik ideology in Gīlān, highlights the Jangalīs’ weakness in the face of the Bolsheviks.34Moisi Aronovich Persitis, Jibhah-yi Īrānī-Inqilāb-ī Jahānī (Asnādī darbārah-yi Tajāvuz va Tahājum-i Shawravī bih Gīlān, 1920-1921), transl. Muhammad Nāyib-Pūr, (Tehran: Nigāristān-i Andīshah, 2023), 166. Russian archival documents indicate that Kūchak Khān had significant reservations about collaborating with the Bolsheviks and approached them with caution.

Figure 12: The meeting between the Red Army commander and Kūchak Khān in Anzalī. Screenshot from the film Sardār-i-Jangal, (1983), directed by Amīr Qavīdil. Accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?app=desktop&v=DVZyozh0VXs (00:16:35).

On June 24, 1920, the Revolutionary Committee (REVKOM), composed of Iranian and Russian members, was established in Rasht, and the revolutionary government began its work.35After the initial cooperation between the Jangalī leaders and the Bolsheviks, a delegation with both Iranian and Russian members, called REVKOM (short for Revolyutsionnyy Komitet, meaning Revolutionary Committee), took leadership of the movement in Rasht. In this group, Kūchak Khān held the positions of Sub-commissioner and Commissar of War. See Gīlak, Tārīkh-i Inqilāb-i Jangal, 276-289. After the establishment of the provisional republic in Gīlān, betrayals and conspiracies against Kūchak Khān commenced shortly thereafter. On August 1, 1920, Iranian communists, led and supported by the Soviet Cheka, opposed Kūchak Khān’s views and ideologies, launching a coup against him to take control of the government. Kūchak Khān, who had previously been informed of the plot by his own people, returned to the forests of Fūman after sending two of his representatives to Moscow to meet Vladimir Lenin, in order to voice his protest and inform him of the events that had unfolded in Gīlān. However, his envoys were unable to meet with Lenin. Moreover, all the Bolsheviks who had supported Kūchak Khān, including Kazanov, Ordzhonikidze, Palaev, and Raskolnikov, were recalled. The coup plotters arrested some of Kūchak Khān’s allies and executed others, but their attempts to capture him were unsuccessful. In this part of the film, we witness Kūchak Khān’s passive response to the betrayal by the Bolsheviks, the Iranian communists, and his own companions and close associates.36Gīlak, Tārīkh-i Inqilāb-i Jangal, 307-309.

When the coup plotters’ efforts to arrest or kill Kūchak Khān proved unsuccessful, they changed their strategy. Representatives from the Caucasus and Moscow went to the forest to meet with him. While seeking his opinion on the future of the revolution, they raised the issue of Haydar Khān ‛Amū-ughlī joining the Jangal movement. Kūchak Khān agreed to let Haydar Khān come to Gīlān to resolve the internal conflicts of the movement. The news of Haydar Khān’s arrival scared Ihsānallāh Khān and Khālū Qurbān because they view him as a threat to their positions; therefore, they sought reconciliation with Kūchak Khān and expressed regret and remorse for their past actions. Haydar Khān entered Gīlān with 500 soldiers and a ship full of weapons, and was welcomed by Kūchak Khān. As a result, a new revolutionary committee, with the presence of Haydar Khān, held a meeting, and on June 22, 1921, the first declaration of the Revolutionary Council introduced its members as follows: Kūchak Khān, Haydar Khān, Ihsānallāh Khān, Khālū Qurbān, and Mīrzā Muhammadī Inshā’ī.

However, in the second declaration of the council, published on August 14, the name of Ihsānallāh Khān was removed from the Revolutionary Committee and replaced by Mahdī Sarkhush. Haydar Khān, a staunch communist, raised the issue of the abolition of private property in one of his meetings with Kūchak Khān, who strongly opposed it. The former believed that the abolition of private property would bring them closer to Communist Russia, and that such alignment would require bearing arms and engaging in armed resistance. Dissatisfied and frustrated with Kūchak Khān’s views and decisions, Haydar Khān secretly began promoting his own communist ideology, managing to rally several of the Jangalī commanders to his cause. The news of Haydar Khān’s conspiracy, which risked aligning the Gīlān revolution with the communist world, prompted a reaction from Kūchak Khān and led to the Mullāsarā incident, resulting in Haydar Khān’s arrest and ultimately his death. The director makes no mention of Ihsānallāh Khān’s attempt to invade Tehran in order to capture the capital after his removal from the committee, despite this being one of the significant and decisive incidents in the Jangal Movement, influencing its final days.37Fakhrā’ī, Sardār-i Jangal, 339.

Figure 13: Representatives from the Caucasus and Moscow met with Kuchak Khan in the forest to discuss the future of the revolution and Haydar Khān’s cooperation with the Jangal movement. Screenshot from the film Sardār-i-Jangal (1983), directed by Amīr Qavīdil. Accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?app=desktop&v=DVZyozh0VXs (00:25:22).

The divisions and internal conflicts within the Jangal movement coincided with the policies of the Soviet Union and Britain, both aiming to end the activities of the Jangalīs in Gīlān. On May 26, 1920, Leonid Krasin, the representative of the Soviet government, traveled to London to negotiate an economic agreement with the British government. Following the Anglo-Soviet trade agreement, the two sides agreed that the Bolsheviks would withdraw their support for the Jangalīs, effectively bringing the matter to a close. Theodore Rothstein, the Soviet ambassador to Iran in 1921, sent a letter to Kūchak Khān, urging the disarmament of the Jangalīs and their surrender to the government forces.38Rothstein was tasked with extinguishing the flame of the Gīlān revolution without damaging the reputation or the freedom-loving image of the Bolsheviks. See Fakhrā’ī, Sardār-i Jangal, 364. Following the withdrawal of Bolshevik support for the Jangalīs, Rizā Khān was dispatched to Gīlān to put an end to the movement. Khālū Qurbān surrendered, and Ihsānallāh Khān, along with several other Bolshevik supporters, fled to the Soviet Union.39Gīlak, Tārīkh-i Inqilāb-i Jangal, 515-517. Nevertheless, Kūchak Khān continued to resist and ultimately died from the cold in the mountains of Tālish. The image of the Bolsheviks portrayed by the director in Sardār-i Jangal depicts them as cruel, treacherous, and unreliable allies who spared no opportunity to harm Kūchak Khān and the Jangal movement, and, at critical historical moments, abandoned the movement to the mercy of the government forces. Of course, this characterization of the Russians is not incorrect, as there is no doubt that throughout their five-hundred-year history of relations with Iran, particularly since the Qājār period, the Russians have consistently threatened Iran’s territorial integrity and national interests, while securing their own.

Conclusion

The film Sardār-i Jangal is produced in the historical genre. Amīr Qavīdil created this work in the atmosphere of post-revolutionary Iran on one hand, and the escalation of the war with Iraq and the need to highlight a historical figure on the other hand. The film was created with an anti-foreign perspective that was fully supported by the ruling regime. It seems that the director’s primary goal was to present a charismatic and mythical figure of Kūchak Khān to an audience of the time with limited knowledge of the Jangal movement. In terms of artistic elements, the film has succeeded in portraying a convincing image of Kūchak Khān. The makeup and portrayal of his facial features give the impression of him as a gentle, compassionate, and honorable leader.

However, by closely examining Kūchak Khān’s behavior, the director unintentionally portrays him as a weak and passive leader who, when faced with difficulties, resorts solely to inaction. The filmmaker’s focus is on the character of Kūchak Khān. As the main hero of the film, Kūchak Khān is portrayed as a patriotic individual, religiously devoted and committed to religious rituals, peaceful, emotional, and idealistic. However, the audience perceives a sense of inaction and leadership weakness, as Kūchak Khān is repeatedly deceived by Khālū Qurbān and Ihsānallāh Khān. Although Kūchak Khān is friendly and open to everyone who wants to join his cause, he struggles to enforce a consistent strategy or approach when it comes to dealing with his opponents. The film does not explore the reasons for the movement’s failure, but Kūchak Khān’s own approach becomes the Achilles’ heel of the movement, ultimately leading to his defeat.

Despite Qavīdil’s effort to present a charismatic character of Kūchak Khān, the image portrayed in the film differs. Perhaps the only impactful depiction of Kūchak Khān is during his speech on the deck of the Kursk battleship, where he expresses his views to the Bolsheviks. Of course, this dramatic scene does not align closely with historical facts. There is no historical record or evidence suggesting that he presented the Jangal movement manifesto to the Bolsheviks. This part of the film was likely included to emphasize Kūchak Khān’s anti-Bolshevik stance. Although Kūchak Khān insisted on opposing Marxist propaganda in his joint meeting with Raskolnikov, there is no historical record—nor even in Fakhrā’ī’s book—that mentions such a speech on the deck of the Russian battleship.

In addition, many other historical events addressed by Qavīdil in his film do not align with the historical realities described by other participants in the Jangal movement who were directly involved in those events. The main issue, of course, lies with the historical source of the film, which is Fakhrā’ī’s Sardār-i Jangal. This book is not a reliable source compared to other relevant works. The accounts provided by Yaqīkīyān and Gīlak regarding the final months of the movement are far more trustworthy than the narrative by Fakhrā’ī, which Qavīdil relies on in his film. Yaqīkīyān and Gīlak played active roles in many of the key events of the Jangal movement, while Fakhrā’ī, not being directly involved in much of the movement—particularly in its final months—relied on intermediary accounts to recount many of these incidents. Overall, in terms of both narrative and historical accuracy, Sardār-i Jangal not only suffers from significant weaknesses in its storytelling, but also fails to help the audience fully grasp a movement that had a profound impact on the intellectual and social transformations of contemporary Iran. Instead, it may, to some extent, lead to a misinterpretation of this major historical event.

Cite this article

Sardār-i-Jangal, directed by Amīr Qavīdil and produced in Gīlān in 1983, is based on Ibrāhīm Fakhrā’ī’s book of the same name. The film is a loose adaptation of Fakhrā’ī’s book, so viewers should not expect a purely historical depiction. Although the Jangal movement occurred from 1915 to 1921 in Gīlān, Qavīdil focuses only on the final seventeen months of the movement, starting in May 1920. It seems that the director, in the context of Iran’s post-revolutionary climate, aimed to depict Mīrzā Kūchak Khān Jangalī as a charismatic and revolutionary figure, while connecting the Jangal movement’s struggle against foreign forces to the political developments of the contemporary period and revolutionary slogans.

This article aims to address the following questions: What were the director’s objectives with the production of the film? To what extent was he able to represent the historical realities in his film? Based on the film analysis, as well as a comparison with Fakhrā’ī’s book and other historical sources covering the final months of the movement, the film is not particularly faithful to historical facts. Much of the film’s plot is based on the filmmaker’s assumptions and a fictional narrative. In Sardār-i-Jangal, many historical events do not align with the scenes portrayed by the director. This article, through descriptive-interpretive as well as historical research, attempts to provide appropriate answers to the above questions.