The Swallows Return to The Nest (1964)

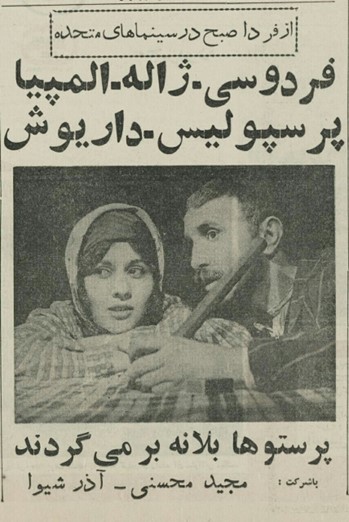

Figure 1: Poster for the film Parastū-hā bih lānah bar-mīgardand (The Swallows Return to Their Nest), Directed by Majīd Muhsinī, 1964.

Introduction

The release of Majīd Muhsinī’s (1923-1980) much-anticipated film The Swallows Return to Their Nest (Parastū-hā bih lānah bar-mīgardand, 1963) was something of a national event in Iran. Moviegoers, my father and I included, flocked to theaters for the film’s opening. The film centers on its protagonist ‛Alī, a simple, hard-working farmer and father, who, along with his wife, compels his son to return to forego the corrosive temptations of the West after he travels abroad to complete his medical degree and to return instead to their village to build his kin a much needed clinic. Through his portrayal of ‛Alī, Muhsinī articulated a powerful critique of Iran’s rapid modernization while advocating for the preservation of pastoral values. If the 1960s witnessed the crystallization of anxieties about Iranian modernization into a call for a return to tradition, then The Swallows Return to Their Nest offered a cinematic meditation on questions of authenticity, tradition, and cultural erosion that had preoccupied Iranian thinkers engaged in a broader intellectual discourse about gharbzadigī (Westoxification).

Majīd Muhsinī, the film’s director as well as its lead actor, was born on May 24, 1923 (2 Khurdād 1302) in Jīlārd, a small town in Iran’s northcentral Damāvand County. Despite his small-town roots, like many other popular Pahlavi intellectuals, Muhsinī successfully climbed the ranks of the midcentury Iran’s growing cultural scene to enter Tehran’s “high society.” Muhsinī’s acting career began as a teenager alongside his older brother Husayn Muhsinī. His first professional acting experience came at the age of sixteen in 1939, when he was cast in a theatrical production Salome. By 1947, Muhsinī had expanded beyond the theater stage to star in his first television advertisement. In 1951, Muhsinī starred in his first feature film, Khāb-hā-yi talā’ī (Golden Dreams), directed by the playwright Mu‛iz-u Dīvān Fikrī. In addition to Muhsinī’s appearances on stage and on camera, he worked simultaneously as one of Iran’s foremost radio actors, creating the radio character ‛Amqulī Samad, a simple-hearted villager with a sing-song accent who featured in satirical comedies broadcast on Iranian radio from 1955 to 1963.

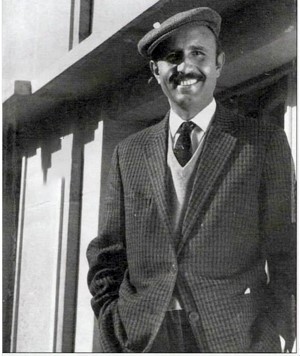

Figure 2: Portrait of Majīd Muhsinī

Muhsinī also forayed into politics, representing the people of Damāvand in Iran’s National Assembly for two terms (the twenty-first and twenty-second terms) from 1963 to 1969, at which point he was appointed cultural advisor to the National Radio and Television Organization of Iran. In addition to his work as a director, film, theater, and radio actor, and civil servant, Muhsinī founded the Mihrigān Film dubbing studio with the cooperation of other artists, including Shukrallāh Rafī’ī and Rizā Karīmī, ‛Azīzallāh Rafī’ī, Ahmad Shīrāzī, and Mahdī Amīrqāsimkhānī. The studio remained active until 1980, at which point Muhsinī, who remained artistically, politically engaged until the end of his days, passed away.

The significance of The Swallows Return to Their Nest lies in large part in its timing and cultural resonance. The 1960s marked a decisive shift in Iran’s developmental trajectory, as rising oil wealth accelerated urbanization and catalyzed profound social transformations and dislocations. These changes prompted intense debate among Iranian intellectuals about the cultural costs of modernization and the necessity of preserving Iran’s disappearing customs. While philosophers like the public intellectual Ahmad Fardīd approached these questions as matters of philosophy, Muhsinī translated these concerns into the accessible medium of popular cinema, crafting a popular narrative that spoke to rural and urban audiences alike about the moral and social implications of subordinating traditional values to modern conveniences.

This article proceeds in three parts. First, I situate The Swallows Return to Their Nest within the transformations of the 1960s, examining how the film responds to and reflects the period’s social and economic changes. Second, I demonstrate how Muhsinī’s cinematic treatment of the pastoral both drew from and contributed to the broader intellectual discourse of gharbzadigī, while offering a distinctively artistic rather than purely philosophical engagement with questions of tradition and modernity in Iran. Lastly, I offer a close reading of the film itself, analyzing the film’s imagery and narrative structure, arguing that its nostalgia for Iran’s pastoral past amounted to a critique of urban alienation, particularly focusing on its representation of the moral corruption and social incoherence endemic to city life.

Context and Conceptualization: The Pastoral and the Many Faces of Gharbzadigī

The sixties were a decade of simultaneities: decolonization and development converged to expand education, national income, and native industries for recently independent countries; yet this attempt to coincided with global rebellion against established powers, culminating, for instance, in the worldwide student and anti-war protests of 1968.1See Chen Jian et. al., ed., The Routledge Handbook of the Global Sixties: Between Protest and Nation Building (London & New York: Routledge, 2018). Iran did not fall outside the global scope of the decade’s transformations. There, a program of top-down land and social reform that aimed to radically transform Iran, known as the White Revolution, and popular opposition to the Mohammad Reza Shah, the modernizing Pahlavi monarch, converged in 1963. In Tehran, as in Tashkent, the Cold War principle of “reform or revolution” coincided with the growing international demand for oil, the formation of OPEC (Organization for Petroleum Exporting Countries), and, eventually, a thawing of US-Soviet as well as Soviet-Iran relations, to make the 1960s, for Iran as elsewhere, not only the development decade but, as Roham Alvandi argues, “the high-point of Iran’s global interconnectedness.”2Roham Alvandi, “Introduction: Iran in the Age of Aryamehr,” In The Age of Aryamehr: Late Pahlavi Iran and its Global Entanglements, ed. Roham Alvandi (London: Gingko Press, 2018), 13.

Released in 1963, The Swallows Return to Their Nest thus coincided at home with the White Revolution, Iran’s most ambitious program of land reform to date and the consequent emigration of rural Iranians en masse to Iran’s cities, and globally with the intensification of capitalism’s capacity for space-time compression, which, as David Harvey has written, “puts the aesthetics of place very much back on the agenda.”3David Harvey, “Time-Space Compression and the Postmodern Condition (1989),” In Postmodernism and the Contemporary Novel, ed. Brian Nicol (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2002).

Figure 3: Promotional poster for the film The Swallows Return to Their Nests, along with the name of the cinemas where it will be screened.

The White Revolution thus epitomized the contradictions inherent in Iran’s modernization project and in the development efforts of the 1960s worldwide. The program’s ambitious land reforms, industrial development initiatives, and social reforms aimed to catapult Iran into modernity through top-down transformation.4Ervand Abrahamian, A History of Modern Iran (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008). Yet these very reforms, designed to eliminate Iran’s backwardness, precipitated massive changes that would fundamentally reshape and fragment Iranian society. The demographic upheaval that followed—with millions of rural Iranians relocating to urban centers—created new social tensions that would find expression in both political movements and cultural productions.5See, for instance, Cyrus Schayegh, Who Is Knowledgeable Is Strong: Science, Class, and the Formation of Modern Iranian Society, 1900-1950 (Berkeley, University of California Press, 2009); Pamela Karimi, Domesticity and Consumer Culture in Iran: Interior Revolutions of the Modern Era (London: Routledge, 2013).

The Swallows Return to Their Nests is thus best understood as an expression of what I have elsewhere termed the “quiet revolution” in the national imaginary of post-coup Iran.6Ali Mirsepassi, The Quiet Revolution: The Downfall of the Pahlavi State (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019). The period after nationalizing Prime Minister Muhammad Musaddiq’s forcible removal from power in 1953 witnessed a dramatic rise in antimodern sentiments among many Iranian intellectuals. As I have argued, Iranian antimodernism of this era should not be understood as the articulation of some congenital tendency toward antirationalism, but as a contingent product of the closure of democratic channels of communication that occurred against a broader global backdrop of authoritarian governance, development theory, and cultural ferment. While the “reform or revolution” paradigm that dominated Cold War thinking continued to influence Iranian policy-makers, at the level of popular discourse, as evidenced by films such as The Swallows Return to Their Nest, a shift was taking place away from the cosmopolitan modernism that had characterized earlier decades.7For more on this paradigm, see, for instance, Eric Hooglund, Land and Revolution in Iran, 1960-1980 (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1982).

Whereas Marxism in Iran had in its heyday between the 1930s and 1940s been staunchly modernist and proudly cosmopolitan, evident, for instance, in the thought of figures like Taqī Arānī and the early Tūdah Party, who affirmed an egalitarian Iran and a liberatory vision of Third World modernization linked through anti-imperial struggle, after the coup, the Pahlavi regime faced a critical choice: to open up, or to concentrate power dictatorially, making the Shah a god-like figure—and they chose the second path. Rather than legitimate state power through democratic power-sharing, the Pahlavi state appropriated ideological components conveniently, and it was in this context that the public space of images and narratives became truly significant and contested. The experience of New Wave cinema paralleled this process, fostering a mixture of hope in “tradition” and Islam, as it rejected the modern and the Western as corrupt.

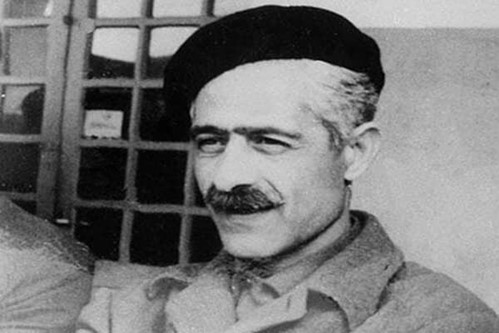

Figure 4: Portrait of Jalāl Āl-i Ahmad.

It was at this same time that former Marxists, of which the schoolteacher turned theorist Jalāl Āl-i Ahmad (1923–69) was the prime example, began to quietly embrace the anti-modern ideologies spreading among Europeans disaffected by the Great Depression and two catastrophic world wars. Simultaneously, a significant attempt was made among Iranian intellectuals to creatively localize Marxism within a new nativist idiom. The notion of gharbzadigī (Westoxification) united different segments of the Iranian intelligentsia through its a critique of the West embedded in which was desire for a “return to the self,” Proponents of gharbzadigī rejected autocratic modernization and championed the “spiritual” or pastoral, envisioning a time before the domination of Western norms and values. In this context, gharbzadigī discourse positioned its own narrative as the “transcendent” alternative to secular and modern Iran.8Mehrzad Boroujerdi, Iranian Intellectuals and the West: The Tormented Triumph of Nativism (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1996).

Jalāl Āl-i Ahmad’s intellectual transformation from leftist to the theorist of Westoxification offers a telling story of a generation of Iranian intellectuals who in the earlier part of their lives enthusiastically embraced socialism as a solution to the ills of their country, only to later abandon this cosmopolitan outlook in favor of a “local” and “authentic” perspective. Āl-i Ahmad was a short-story writer, novelist, essayist, social critic, translator of French literature, and political activist. Although he is best known for popularizing the notion of gharbzadigī or Westoxification, his earlier fictional writings critiqued Iranians’ reduction of religion to a set of blindly followed values and habits. It was only in his later works that he developed a distinct sociopolitical critique of Iran’s relationship to the West, which was also structured, he argued, by a tendency toward imitation. Āl-i Ahmad wrote with a sense of political urgency, rather than with scholarly hesitation, yet he was one of the most powerful critics of Pahlavi rule. In many ways, his fiction offers an autobiographical sketch of a man torn between opposing tensions within himself. Āl-i Ahmad’s mused on his vocation as a teacher, revealing the split he felt between tradition and modernity:

There is a difference between a teacher and a preacher. A preacher usually touches the emotions of large crowds, while a teacher emphasizes the intelligence of a small group. The other difference is that a preacher begins with certitude and preaches with conviction. But a teacher begins with skepticism and speaks with doubt . . . And I am professionally a teacher. Yet I am not completely devoid of preaching either.9Āl-i Ahmad, Kārnāmah-yi Sih Sālah (Tehran: Rivāq Publisher, 1979), 159.

Āl-i Ahmad’s increasing willingness to preach of the pitfalls of modern politics was sparked by his disillusionment with the Tūdah Party’s increasing capitulation to the Soviet Union as well as by the Soviet Union’s failure to come to Iran’s help after the nationalization of the oil industry in 1951 was met with a Western blockade. Āl-i Ahmad theory of gharbzadigī emphasized the complicity of Iranian leaders and thinkers who upheld Western hegemony rather than work to construct an authentically Iranian modernity. Āl-i Ahmad argued that a “return” to “authentic” Iranian-Islamic tradition would be necessary if Iran were to avoid the homogenizing and alienating corollaries of modernization. Yet, the “return” advocated by Āl-i Ahmad was not entirely straightforward. Āl-i Ahmad’s vision of populist Islam did not reject modernization as such, but sought to reimagine it in accordance with Iranian–Islamic tradition, symbols, and identity.

Āl-i Ahmad’s theory of gharbzadigī thus cannot simply be reduced to an anti-Western polemic. Although his writings lacked scholarly sensitivities or even historical accuracy, he nevertheless wrote with personal passion, intellectual sharpness and anger.

Āl-i Ahmad’s return to Islam was a quest to realize a national modernity in Iran. His wife Sīmīn Dānishvar offered an interesting account of Āl-i Ahmad’s intellectual conversion:

If he turned to religion, it was the result of his wisdom and insight because he had previously experimented with Marxism, socialism and to some extent, existentialism, and his relative return to religion and the Hidden Imam was toward deliverance from the evil of imperialism and toward the preservation of national identity, a way toward human dignity, compassion, justice, reason, and virtue. Jalāl had need for such a religion.10Āl-i Ahmad, Iranian Society, ed. Michael Hillmann (Lexington, KY: Mazda Publishers, 1982), xi.

In his pioneering work The Country and the City, the cultural critic Raymond Williams analyzed nostalgic cultural constructions exemplified precisely by gharbzadigī discourse. He argued that nostalgia for a pastoral past often relies on misrepresentations of that very same past.11Raymond Williams, The Country and the City (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1973). For Iranian artists and intellectuals operating under Mohammad Reza Shah and living largely in urban centers, the desire for a “simple” and “authentic” mode of being prevailed despite, or perhaps because of, their very alienation from provincial life. Iranian intellectuals in the 1960s imagined their rural forebears as living in an organic community, continuously linked to an ancient past, from which they had been suddenly and tragically estranged. By attempting to reconcile the pastoral with the modern, The Swallows Return to Their Nest exemplifies thinking about modernity characteristic of late Pahlavi Iran, when many filmmakers and writers, in a display of what the scholar Hamid Naficy calls “salvage ethnography,” traveled to Iran’s villages for inspiration and out of a paternalistic impulse for preservation.12Hamid Naficy, “The Anthropological Unconscious of Iranian Ethnographic Films: A Brief Take,” Cinema Iranica Online, accessed November 14, 2024, https://cinema.iranicaonline.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/Naficy-draft-1.pdf.

These filmmakers infused, through a visual lyricism that valorized the harmony, honesty, and simplicity of rural life, gharbzadigī with a distinctly pastoral element. In the process, filmmakers like Muhsinī expanding the meaning, resonance, and subjects of gharbzadigī to include not just urban Iranians, who traveled to Tehran from their provincial villages only to find unemployment and hunger, but to villagers as well, whose very way of life and with it Iranian identity, as films like The Swallows Return to Their Nest suggested, was under threat. The pastoral genre in Iranian cinema of the 1960s accordingly warrants consideration not merely as an aesthetic choice, but as what Raymond Williams terms a “structure of feeling”—a lived and felt response to social transformation that precedes its formal articulation in political or philosophical discourse.13Aymond Williams, Culture and Society: 1780–1950 (London, 1958).

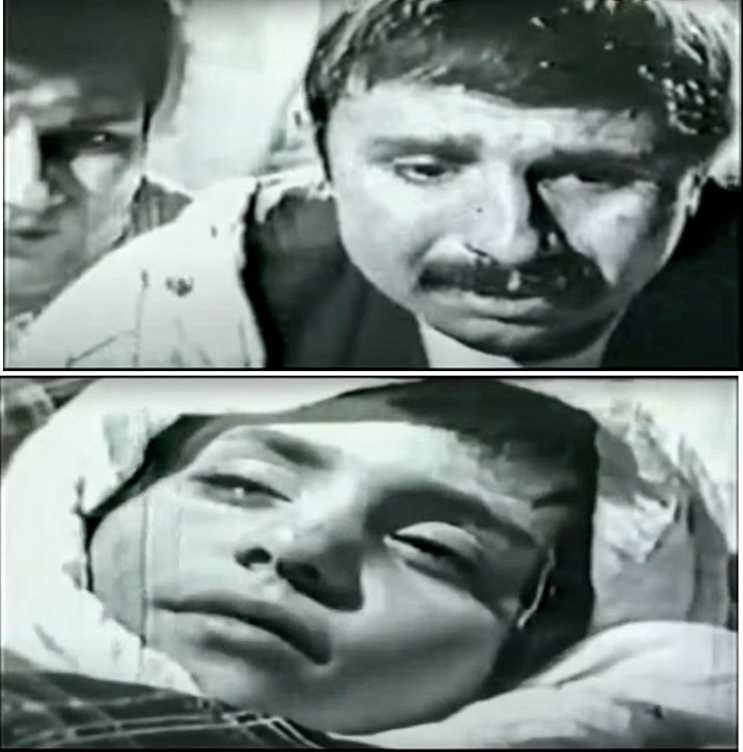

Figure 5: A screenshot from the film The Swallows Return to Their Nest, Directed by Majīd Muhsinī, 1964.

The first successful movies operating in what we might call this pastoral genre centered on the life of Iranian villagers and include works such as Sharmsār (Disgraced, 1950), Mādar (Mother, 1951), and Ghiflat (Neglect, 1953). Across these productions, the purity, decency, and honesty of villagers is favorably contrasted to the sophistication, charlatanry, and corruption of city dwellers. These films were highly successful with impoverished workers and urban migrants living on the margins of growing cities. Social divisions and class struggle were often baked into these romanticized films, which made frequent use of binaries like village-city life, poor-rich, and worker-boss, always grafting these pairings onto the equally universal good-evil dyad.

While these films established formal conventions for representing rural virtue sufficient for attracting recent urban transplants to movie theatres, Muhsinī’s The Swallows Return to Their Nest elevated these same themes and conventions into a cultural critique resonant with a larger cross section of Iranian society, eventually being selected as Iran’s official submission to a foreign film festival in Moscow. Unlike earlier entries into the pastoral genre, which often pitted deceitful city dwellers and admirable village folks in a straightforward battle of good and evil, Muhsinī’s film deploys pastoral imagery and an epic narrative structure to suggest that tradition should not simply overcome modernity but wrestle with it in order to capture its best qualities, such as modern medicine, without trampling underfoot the admirable qualities of authentic Iranians. The Swallows Return to Their Nest thus crucially modifies the pastoral genre to suggest that the benefits associated with the modern world should be embraced if and only if they can be localized to the culturally authentic rural setting.

The film’s seemingly simple story of ‛Alī’s farming family is thus best understood as a complex meditation on the politics of authentic existence—a theme that united otherwise opposed constituencies in the 1960s in an idealization of rural life, tradition, and the poor as repositories of authentic Iranian identity. In translating its concepts into popular cinematic form, the film expanded the parameters of gharbzadigī discourse. While the provocative intellectual Ahmad Fardīd initially coined the term gharbzadigī as a philosophical critique of Western metaphysics, Jalāl Āl-i Ahmad later popularized the term with the publication of his broader sociopolitical critique of Iran’s adoption of Western materialism, which he believed had subjugated man to machine. Muhsinī’s film demonstrates how ideas permeated cultural production in ways that transcended their original theoretical formulations, expanding gharbzadigī from a distinctly philosophical concept to a structure of feeling, in Williams’ sense of the term.

In the close reading of the film’s visual grammar—its lingering shots of traditional agricultural practices, its contrast between urban and rural spaces, its careful integration of modern elements like medicine within traditional settings—that follows, we can trace how gharbzadigī evolved from abstract philosophical concept into a popular feeling and aesthetic practice. This approach reveals how Iranian cinema of this period did not simply reflect existing intellectual debates but actively participated in shaping them, offering what we might call, following Hamid Dabashi, a “visual literacy” of anti-Western sentiment that made complex philosophical critiques accessible to broader audiences while simultaneously enriching those critiques through artistic innovation.14Hamid Dabashi, Close Up: Iranian Cinema, Past, Present and Future (London: Verso, 2001).

The Swallows Return to Their Nest: A Close Reading

The Swallows Return to Their Nest opens with the protagonist ‛Alī performing his prayers outdoors. Behind ‛Alī stand white-capped mountains and a cropping of trees. ‛Alī’s prayers and the natural beauty that surrounds him anoint the story to come, which extols Iran’s God-given beauty and piety as much as it does the people who cultivate these virtues. ‛Alī is in the middle of reciting “Allāh-u Akbar” when his wife, who goes unnamed, breathlessly runs in. She has come to tell ‛Alī that their child’s health has taken a turn for the worse. The film cuts to a group of women seated indoors, all of them in traditional rūsarīs and dress, around a girl bundled in blankets and resting upon the floor of a modest home. One of the women is burning ispand over the ailing child’s body, reciting a prayer in order to break the evil eye that she supposes is afflicting the child. Suddenly, ‛Alī, her father, bursts into the room. He kneels before the blanketed body around which the village women have gathered and calls out, “My daughter!” The girl answers weakly: “Bābā…”15The Swallows Return to Their Nest, 00:04:23. ‛Alī, electrified by her voice, cries out to the women, asking what he should do. One suggests fortifying her with a serving of eggs would fortify her, another exclaims that more ispand should be burned. As if overwhelmed by the meagerness of their recommendations given the gravity of his daughter’s situation, ‛Alī spurns the village women, lifts his daughter into his arms, and declares right then and there that he’s taking her to the doctor.

Figure 6: ‛Alī kneeling before his ailing daughter, screenshot from the film The Swallows Return to Their Nest, Directed by Majīd Muhsinī, 1964, accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xJbn1Sy3oxU (00:04:23-00:04:35).

‛Alī carries his infirm daughter two hours away to the nearest doctor, his worried wife trailing behind him. ‛Alī and his wife enter the doctor’s office and explain, panic-stricken, to the Kafkaesque attendant that their child is gravely ill. But he responds with churlish indifference that the doctor sees patients in order of their appearance and commands them to sit down. ‛Alī and his wife reluctantly sit between a group of old men who moan and grunt in pain. When another attendant enters the sparse waiting room to announce that the next patient will be seen, ‛Alī and his wife rise to beg the man to let their daughter be seen in his place, to which he relents.

Once inside the doctor’s office, ‛Alī lays the child on an examination bed. The doctor asks what is wrong with her, and they explain that she has an illness of the throat. The child’s mother begs the doctor to save their child. But the doctor’s examination takes no more than a minute from beginning to end. He peers into her throat, takes her pulse, and as a final perfunctory gesture, lifts open one her closed eyelids. The doctor asks the mother to step outside, assuring her that nothing is the matter. The doctor explains to ‛Alī once his wife has exited that a father’s capacity to tolerate, presumably the intolerable, is greater. He tells ‛Alī, who is at this point trembling, that his daughter was sick with diphtheria and has passed just two or three minutes ago. The doctor, unsympathetic to the ‛Alī’s shock, reprimands him, asking why he delayed bringing her to the doctor. Had a doctor seen her sooner, he says with muted disdain, the girl would still be alive. ‛Alī meekly explains that he and his family live two hours away from the nearest doctor, before he collects his dead daughter from the examination table and exists the doctor’s office.

In the next scene, we see ‛Alī speaking to a village notable. Two servants wait upon the man, who is perhaps a kadkhudā. The notable’s wife sits beside him, and like her husband, she is conspicuously large. The husband and wife’s rotundity serves to mark their status and wealth, as does the brusque air with which they command the servant to pour them glass after glass of drink. ‛Alī, by comparison a diminutive man, stands hunched before them as he relays his bad news. The village notable responds that his son was once sick with diphtheria. When ‛Alī remarks, “Yes, but your child lived,” the man responds as a matter of fact: “A doctor was by our side, he saved him quickly” (duktur baghal-i gush-i-mūn būd, zūdī nijātish dād).16The Swallows Return to Their Nest, 00:11:40 to 00:11:42.

These words go off in ‛Alī’s head like an explosion. He repeats them aloud to himself as he walks away from the couple mid-conversation, stupefied. The notable quips to his wife that ‛Alī’s lost his wits, but his wife defends ‛Alī, who she reminds him is in a state of mourning.

Meanwhile, ‛Alī continues to wander aimlessly about the village, the words “A doctor was by our side, he saved him quickly” still recurring to him. ‛Alī eventually stumbles into his older son, Jalāl, his only remaining child. The sight of Jalāl lifts the fog from ‛Alī’s head. He grabs Jalāl by the shoulders and proclaims: “You must become a doctor! Be by our side” (bāyad duktur shavī! baqal-i gush-i-mūn bashī).17The Swallows Return to Their Nest, 00:14:48 to 00:14:51.

Figure 7: ‛Alī drifts about the village, the notable’s words recurring to him, when his remaining child, Jalāl, approaches him from behind. A screenshot from the film The Swallows Return to Their Nest, Directed by Majīd Muhsinī, 1964, accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xJbn1Sy3oxU (00:14:32).

In the next scene, ‛Alī has gathered a group of village men to share with them his plan to make a doctor of Jalāl. The village elders are incredulous: What business do we village people, they remark aloud, have becoming doctors? Leave that for the son of the master (arbāb). Besides, others add, there are only ten classes offered in the whole of the village, and his son Jalāl, still a young boy, has already completed two of them.

Figure 8: ‛Alī grabs Jalāl by the shoulders, exclaiming, “You must become a doctor!” a screenshot from the film The Swallows Return to Their Nest. Directed by Majīd Muhsinī, 1964, accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xJbn1Sy3oxU (00:14:43).

But ‛Alī’s mind is made. ‛Alī decides to lease his orchards (bāgh) for the time that he, his wife, and Jalāl move to Tehran, where Iran’s finest schools will educate Jalāl in ways that the village, which offers only 10 classes, could never. The three of them board a bus, where ‛Alī, next to some of the slicker, more experienced passengers, sticks out as a country bumpkin. ‛Alī carries his belongings in a cloth bundle and despite taking his seat toward the front of the bus, he ends up near its rear as new passengers board and find reason to evict him from his row and his seat. ‛Alī eventually settles toward the back of the bus, where he is joined by a trickster of a man. The bus has not left the depot yet, and a village resident shares a parting caution with ‛Alī: Be watchful of the money you’re carrying with you. The trickster overhears this, and for the rest of the ride, he prods at ‛Alī, who is already nervous and fidgeting. He points out Tehran’s wonders, like the office of the Shirkat-i Naft, only to then ask ‛Alī if he happens to have change for twenty tumans, to which ‛Alī responds unconvincingly that he doesn’t have anything on him, even as he shifts in his seat continuously, moving his money pouch from one side of his jacket to the other and back again.

Figure 9: ‛Alī seated on the bus to Tehran next to a pickpocket, an embodiment of the urban hazards to come, a screenshot from the film The Swallows Return to Their Nest, Directed by Majīd Muhsinī, 1964, accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xJbn1Sy3oxU (00:21:33).

When the bus finally arrives in Tehran, the fellow sitting next to ‛Alī bumps into him, making off with his cloth bundle. ‛Alī tells the guy to watch where he’s going and seconds later thinks to check his pocket. ‛Alī has been robbed, but not of his money. The fast-talking passenger confused ‛Alī’s pouch of smoking tobacco with his purse. ‛Alī and his wife share a laugh, their spirits unshaken by the near catastrophe that could have started their life in Tehran. In Muhsinī’s world, seedy characters like the bus thief may populate the big city, but decent folks like ‛Alī always triumph.

We next see ‛Alī settling into his new job in Tehran as a construction worker. ‛Alī’s complaining to one of his coworkers about the tight spot he is in: Jalāl, his son, needs a new set of schoolbooks, since he has a new teacher who has not assigned the same materials as his prior one. The worker tells ‛Alī that he’d make more money performing as Hājī Fīrūz, a folkloric figure who, traditionally with his face painted black and in a red costume and felt hat, sings and beats a drum. ‛Alī is reluctant; playing a public fool would bring his son disrepute. Never mind that, the other coworker responds, you’ll be wearing a costume anyways. And so in the next scene, we see ‛Alī singing and dancing in costume for a group of men, likely drunken, who insult him with one breath then command him to dance with the next. We hear ‛Alī’s inner monologue at this point: He is calming himself against their taunts. Despite their abuses, ‛Alī maintains his cool, thinking about the objective he’s come to Tehran to fulfill.

Figure 10: ‛Alī’s first night working in Tehran as a Hājī Fīrūz street performer. He concentrates on calming himself as a group of audience members taunt him. A screenshot from the film The Swallows Return to Their Nest, Directed by Majīd Muhsinī, 1964, accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xJbn1Sy3oxU (00:29:55).

One night after performing, ‛Alī returns home, the face paint of his Hājī Fīrūz character washed off. He’s speaking lovingly to his wife, professing his indebtedness to the woman who works just as tirelessly as he does, when she notices that his ears are smudged black. She mentions that Jalāl has asked her, “Why are dad’s ears always black when he comes home from work?” It’s either the soot, dust, or dirt of construction, ‛Alī explains with a nervous smile. This dishonestly is not just self-defensive, Muhsinī suggests, since we know that ‛Alī is sparing his wife and son the daily humiliations he encounters by keeping his work a secret.

The film fast forwards a few years. Jalāl is the image of good health. We see him, now a tall athletic young man, finishing up a game of soccer with his classmates. After changing into their street clothes, they head out to continue their evenings, when they chance upon a Hājī Fīrūz performance. Jalāl stands slightly behind his two classmates. His friends laugh at the performer’s song and dance, but whatever smile existed on Jalāl’s face vanishes as he focuses on the performer. Jalāl suddenly calls out from the crowd “Mash ‛Alī.” ‛Alī’s eyes dilate, but he continues singing and beating his drum, when Jalāl calls out again: “Bābā.”

Figure 11: Jalāl at the moment he begins to suspect that the Hājī Fīrūz performer he and his friends are watching is his father, ‛Alī. A screenshot from the film The Swallows Return to Their Nest, Directed by Majīd Muhsinī, 1964, accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xJbn1Sy3oxU (00:34:10).

‛Alī still does not respond, but he suddenly exits the crowd, bringing his performance and the revelry of the viewers who had gathered around him to an abrupt end. ‛Alī spends his days’ earnings on the first taxi he can find, but he does so to beat Jalāl home. He confesses to his wife that he’s been working as a street performer and explains that he’s almost been caught by Jalāl. His wife, a loving and hardworking woman, sees no shame in ‛Alī’s work, but she agrees to go along with ‛Alī’s ruse. Just as ‛Alī sits down to lights his pipe, assuming an image of a man long at leisure, Jalāl walks in, his brows furrowed. He calls out to his mom. When he sees his father seated next to her, his worry quickly dissipates. I thought I saw something horrible, he explains, but it was nothing.

‛Alī and his wife, both committed to maintaining an image of domestic harmony and respectability for their son no matter the personal cost, sit down to dinner with Jalāl. They bless their food with a bismillāh and proceed to eat. But Jalāl soon notices that he’s the only one at the table eating kebab. His mother and father are tearing off pieces of a large flat bread and eating it with cheese. When Jalāl asks where their dinner has gone, ‛Alī explains that they were so hungry that they could not help eating before he arrived. He smiles, telling his son to go on and eat, and Jalāl obliges. Jalāl recounts his day’s events to his mother and father. Speaking of the friends he had been with, he mentions that some of them are going abroad to study medicine. I would too, he adds, were it not for the expense. ‛Alī turns to his wife and asks, what should we do? They go back and forth until ‛Alī puts the matter to rest: We’ll sell our farm (bāgh) and use that money to finance Jalāl’s education abroad. Jalāl interrupt to ask, what are you two talking about? How to make you a doctor, ‛Alī responds, adding that he’ll be going abroad too to study. And so, with this scene, Muhsinī depicts the depths of this mother and father’s devotion. Not only do they forego meat so that their young son might enjoy it, but they are willing to deny themselves their only meaningful possession—the small plot of land that affords them some freedom—so that he might obtain the best education possible too.

We next see ‛Alī and his father together at the airport. With tears in his eye, ‛Alī gifts his son a Quran, reminding him of his guide, and promises to do whatever his son needs in his time away. ‛Alī only asks in return that Jalāl not embarrass (khijil) the family. ‛Alī’s emotional declarations are interrupted by the English announcement that the flight from Tehran to Paris is boarding. Father and son share one last embrace, and with that, Jalāl walks off. Jalāl has already exited the frame, but ‛Alī has more to say: Your mother and I are leaving Tehran; we were only here for you, a confession he seems to make to himself.

‛Alī and his wife return to their village, but with their farm sold, they’ve been reduced to working as laborers (‘amalah) for other farmers. ‛Alī is carrying a huge load, a mass twice his own size perhaps wheat, barley, or some other crop, on his back. He drops the load, under which he was buckling, when another villager approaches to deliver him a letter. It’s from Jalāl, who at this point, the villager adds, has been gone for five or six years. Jalāl and his wife, who quickly joins him, are ecstatic to hear from him. They run frantically around, looking for someone to read them the letter, since they are themselves presumably illiterate. Eventually they find Amīnah who is sitting by a cliff, taking in the tremendous beauty, waterfalls, trees, and, in the backdrop, mountains, that surrounds her.

Amīnah, who we learn in an earlier scene is not only Jalāl’s fraternal cousin (dukhtar-‛amū) but also his fiancé, sits with ‛Alī and his wife. She is just as giddy as they are to see that Jalāl has enclosed with his letter a picture of himself. After the three taking turns kissing and doting upon the photo, Amīnah starts to read the letter. Jalāl expresses his longing to see his mother and father, sings the praises of Paris, a city so beautiful he compares it to heaven (bihisht), and sends his well wishes to Amīnah. He writes that in only four months’ time, he will finish his studies. He adds that it is his hope that in that time, a clinic (darmāngah) might be built for the village, so that he could come and treat his countrymen (ham-vilāyatī).

Figure 12: ‛Alī (left) and his wife (right) sit with their niece, Amīnah (center), who reads Jalāl’s most recent letter home. The use of the waterfall as a backdrop marks what most viewers would consider overwhelming natural beauty as a mundane extension of village life. A screenshot from the film The Swallows Return to Their Nest, Directed by Majīd Muhsinī, 1964, accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xJbn1Sy3oxU (00:54:55).

‛Alī is again transfixed, this time by the word darmāngah. He asks Amīnah hurriedly to reread the sentence in which Jalāl mentions it and continues to repeat it to himself. A clinic, he concludes, must be built. The very next day, ‛Alī visits a village notable to share his proposal for a clinic, but the miserly man has no help to spare; my money is in the hands of the people, he says, which is to say the market, and that is unfortunately tight right now. ‛Alī is, however, undeterred. Perhaps this is a task for the community to take up anyways, he ponders, since it is the community that the clinic will serve. As if confirming ‛Alī’s sentiment, we next see a group of women privately discussing: What good are gold earrings and bracelets if our children are sick? ‛Alī is next standing before an assembly of villagers, included among them the women from earlier, who he has gathered for a meeting. He explains to his fellow villagers that he has devoted his life’s resources, as many of them already know, to making a doctor of his son, and were it not for the fact that the endeavor has left him penniless, he would use his own funds to finance the construction of the clinic. But given the current state of affairs, he beseeches his fellow villagers to pool together their resources so that they might prevent another child from needlessly dying ever again. His emotional appeal, however, is greeted with silence. The group sits motionless until two of the women from the earlier conversation step forward. One of them offers up gold earrings her father had given her, and the other, ‛Alī’s wife, donates three gold bracelets. Their contributions are soon matched. Children, men, and women come forward to donate everything from a goat to whole fruit trees to hundreds of tomans to pounds of apricots to labor are donated toward the construction of the clinic. The villagers erupt into cheers, and already by the next scene we see them happily away at work. Men and women together sing as they shovel dirt, mix concrete, water plants, and slice watermelon to share. They are the image of collective work, action, and happiness. Muhsinī hear notably gives women, in their role as mothers and mourners of the children they have lost to preventable illnesses, pride of place in starting the clinic’s construction, despite his choice of a father as protagonist.

The film abruptly transitions from this utopic image of village life to three men sitting in a dark, smoke-filled café. Leaning again two of the men are two bare-headed women. One of the men accompanied by a woman is none other than Jalāl. The contrast between their sodden indolence leisure and the happy industry of the villagers is stark. Jalāl and the men present with him are deliberating in Persian whether Jalāl should remain in Paris or return home to Iran. Where else are you going to find such beautiful women, one of them asks; no one would fault you for staying, he continues, stopping only to soothe his Parisian girlfriend, who Muhsinī suggests is growing perhaps impatient with the men’s Persian prattling. But the other man interjects, you yourself have a fiancé, and so too does the women who is sitting by your side. Jalāl is torn, but the concluding words of the conversation help his resolve: What more does a parent want than their child’s happiness?

Figure 13: Jalāl (third from the left) deliberates in a café in Paris with his Persian-speaking male friends about whether he should return to Iran, while their French girlfriends drink and smoke. A screenshot from the film The Swallows Return to Their Nest, Directed by Majīd Muhsinī, 1964, accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xJbn1Sy3oxU (01:04:48).

We return in the next scene to the village, where the concrete walls of the clinic have already been erected. ‛Alī and Amīnah stand before the half-constructed clinic. After admiring the village’s accomplishments, Amīnah prepares to read ‛Alī another letter from Jalāl. This time, Jalāl has joyous news to share: He has graduated from medical school and is a doctor at last. But he cautions to add that he also writes to share news that may upset his mother and father. Before declaring exactly what this news may be, he lays out his reasoning: The absence of his mother and father in Paris causes him great unhappiness but leaving Paris at this point would devastate him professionally and personally. Here, he can easily find work, and with his earnings, he could send enough money to his mother and father money to ensure that they are well-provided for. ‛Alī, perhaps anticipating where this is going, cuts Amīnah off. Keep your voice down, he says. The other villagers cannot hear that his son plans to abandon the them just as they are working to build a clinic for Jalāl to return to. ‛Alī takes the letter and walks off, until he comes across two little boys, who he asks to read the letter. Can’t you read? they ask. Of course, but I’m blind, ‛Alī pretends. The children accept this answer and read the part of the letter ‛Alī specifies, one of them more haltingly than the other. ‛Alī learns that Jalāl concluded his reasoning with the suggestion that if he stays in Paris he can marry one of the nice women he’s met there. At this point, ‛Alī has had enough. He yanks the letter from the children and takes leave. ‛Alī wanders the empty, half-constructed clinic, speaking with God. He confides that although his son has broken his heart and committed a great injustice against his father, his family, and his homeland (dīyār), he cannot forsake his son. Instead, he asks God to help return his son to him.

The next scene returns us to Paris. Jalāl is standing beside hist two friends, who are trying to discern the contents of a small box that has just arrived from Iran. What could it be, they wonder? Perhaps a treat from Isfahan? But no, it is for Jalāl. Jalāl opens the box, which contains nothing more than a letter and dirt. His expression taut, he begins to read. I am happy to hear that you have become a doctor at last, his father writes. But woe that you do not know what it took for you to become one. It is time to educate his son in the harsh realities of his education. ‛Alī confesses everything that he worked so hard to conceal: While you ate kebab, he writes, your mother and father ate bread and cheese; while you went to school, I played Haji Firuz, just as you thought and as I denied. Yes, he is disappointed with his son, ‛Alī confesses, but Jalāl is right that a parent wants their child’s happiness. Since I have nothing left with which to buy you a graduation gift, ‛Alī explains, I have enclosed soil from your village, the same soil, he adds, that your “ancestors sacrificed their lives for.” Jalāl looks up and decides right then and there to return to the village, his voice thunders, “I will return to my country (vatanam)!”

Figure 14: Jalāl, with tears in his eyes, proclaims his intention to return home after reading a letter from his father. A screenshot from the film The Swallows Return to Their Nest, Directed by Majīd Muhsinī, 1964, accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xJbn1Sy3oxU (01:17:45).

A caravan of villagers has assembled in the next scene. A band plays festive music in the background while ‛Alī and his wife nervously ask what time it is, noting that Jalāl, the cause of the day’s celebrations, is late. Amīnah, Jalāl’s betrothed, checks in with the nervous pair. “Why aren’t you wearing your dress?” they ask her. “I thought Jalāl would like me more in this,” she responds, gesturing toward her white nurse’s uniform, which she has paired not with a hijab, but a hat. ‛Alī finally arrives. The clamor of the music intensifies and the crowd swarms around him. Amīnah holds out a white lab coat, which he with her help slips into. Amīnah and Jalāl walk side by side into the newly finished clinic, the parade of musicians and villagers following behind them. But we, along with the camera, stay behind with ‛Alī and his wife, who stand sobbing. Their sobs, however, soon yield to an uncontrollable laughter. Their last tears spent, they look into each other’s eyes, lock arms, and follow the crowd that has now receded into the clinic.

Figure 15: ‛Alī and his wife wait impatiently in front of the newly constructed village clinic for their son Jalāl’s bus to arrive. A screenshot from the film The Swallows Return to Their Nest, Directed by Majīd Muhsinī, 1964, accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xJbn1Sy3oxU (01:21:38).

Conclusion

The Swallows Return to Their Nest’s representation of the fragmentations of communal life and family ties associated with Iran’s experience of modernization and rapid urban expansion thus both gave expression to and helped popularize nostalgia for an imagined past of purity and authenticity. The film’s success owed much to its uncomplicated dichotomies: purity versus impurity, spirituality versus materialism, and authenticity versus inauthenticity. The warm reception it received by diverse audiences, from Pahlavi elites to ordinary Iranians to festival judges, indicates that although modernization was arguably the political imperative of the 1960s, it had its emotional-ideological corollary in the quiet pastoralist revolution I have described above.

Muhsinī’s cinematic addition to this quiet revolution is be understood within the broader intellectual landscape of 1960s Iran. While the notion of gharbzadigī had by then emerged as a salient critique of Western materialism, Muhsinī’s film gave it what Raymond Williams has termed a structure of feeling – a lived, emotional response to the profound social transformations precipitated by the White Revolution. By translating the philosophical concerns of intellectuals like Ahmad Fardīd and Jalāl Āl-i Ahmad into the accessible medium of popular cinema, Muhsinī articulated the deep ambivalence surrounding Iran’s developmental trajectory in a manner resonant with a broad swath of Iranian society.

Ultimately, The Swallows Return to Their Nest stands as a critical artifact representing the synthesis of popular pastoralist themes and the more complex sociopolitical critiques intellectual in the sixties offered under the banner of gharbzadigī. Muhsinī’s nostalgic portrayal of pastoral life was not merely a simplistic rejection of progress, but a nuanced meditation on the social and cultural dislocations brought about by rapid urbanization and state-driven development. In doing so, Muhsinī’s work illuminates the emotional landscape of 1960s Iran, where the allure of modernization existed alongside a profound longing for the preservation of cultural authenticity.

Cite this article

This article analyzes Majīd Muhsinī’s 1964 film Parastū-hā bih lānah bar-mīgardand (The Swallows Return to Their Nest) as a cultural artifact reflecting the political climate of 1960s Iran. Scholars tend to remember the sixties as the developmental decade globally, but it was also in those years that a politics of spirituality emerged in Iran response to authoritarian modernization. The Swallows Return to Their Nest, which garnered the director and actor Muhsinī popularity at home and abroad, narrates the story of a devoted farmer who, along with his wife, sacrifices everything in order to educate his son as a doctor after losing his daughter to a preventable illness. By examining the film’s narrative and situating it within the domestic politics of the era, this article suggests that The Swallows Return to Their Nest is best understood as a pastoral articulation of Iran’s “quiet revolution”—a shift in national imagination that valorized traditional authenticity over Western modernity. The film exemplifies the discourse of gharbzadigī (Westoxification) popular among Iranian intellectuals of the period, who idealized an authentic Iranian “self.”

By exploring the film’s treatment of rural-urban relations, tradition versus modernity, and the challenges of uneven modernization, this article illustrates Muhsinī’s attempts to reconcile modernization with a nostalgic vision of rural Iranian life. This article also briefly contextualizes Muhsinī relative to other Western-educated Iranian artists and intellectuals, who similarly romanticized village life. It argues that the film’s success across classes suggests that the modernization policies and land reforms of the 1960s had left Iranians of disparate backgrounds yearning for a return to tradition.

An examination of The Swallows Return to Their Nest contributes to our understanding of how popular directors navigated and narrated modernity in the late Pahlavi era. Ultimately, this article demonstrates that the film helped popularize nostalgia for the pastoral past, a process of historical misrepresentation central to cultural discourse in the decade preceding the Islamic Revolution.