Exploiting Sīghah: Gender, Power, and the Marginalization of Women in Iranian Media

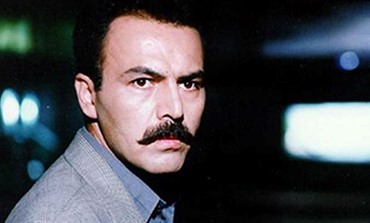

Figure 1: A still from the film Shawkarān (Hemlock), directed by Bihrūz Afkhamī, 2000.

In Iranian films and TV series such as Bihrūz Afkhamī’s Shawkarān (Hemlock, 2000), Muhammad Husayn Farahbakhsh’s Zindagī-yi Khusūsī (Private Life, 2011), and Āydā Panāhandah’s Dar Intihā-yi Shab (In the End of the Night, 2023), the portrayal of Sīghah (temporary marriage) underscores a recurring theme: the exploitation and marginalization of women under the guise of religious legitimacy. Though set in different contexts, these films critique the manipulation of religious practices like Sīghah, exposing underlying gender inequalities. A comparative analysis of Shawkarān and Zindagī-yi Khusūsī highlights the intricate relationship between religion, politics, and gender in Iranian society, with Sīghah serving as a focal point. Dar Intihā-yi Shab extends this discourse through a brief Sīghah, illustrating how in addition to other factors, the practice is often a means of coping with male emotional vulnerability, particularly in the form of a rebound in the aftermath of divorce. Collectively, these works reveal how Sīghah marriages erode women’s rights while reinforcing systemic gender inequality. They further illustrate how state policies promoting Sīghah, particularly post Iran-Iraq War, exemplify government intervention in sexual matters, prioritizing men’s access to heterosexual relationships while restricting women’s agency.1In my book, Temporary Marriage in Iran: Gender and Body Politics in Modern Persian Literature and Film (Cambridge University Press, 2020), I provide an in-depth analysis of the Shawkarān and Zindagī-yi Khusūsī. In this article, I will offer a brief review of these two films before concluding with a final section on the miniseries, Dar Intihā-yi Shab. Sīghah, a legally sanctioned Shia practice, allows men and women to enter a contractual union for a specified duration. While it offers some legal protections for women, men often use it to gain sexual access without committing permanently.

Religious Hypocrisy and Female Victimization

Shawkarān explores the intersection of law, religion, and politics through personal morality.2Bihrūz Afkhamī, Dir. Shawkarān [Hemlock]. Sūrah Cinema, June 12, 2000. The film critiques societal and moral corruption by portraying the eradication of women’s bodies as a symbolic purge of corruption and decadence from the nation. Afkhamī uses Sīghah to reveal conflicts between religiosity and modernity, highlighting the practice’s negative impact on women and society. Key themes include religious manipulation, double standards for women, and the intersection of personal and political issues. Set in 1995 Zanjān and Tehran, the film follows Mahmūd Basīrat (Farīburz ‛Arabniyā), a factory director who engages in a secret Sīghah marriage with Sīmā Riyāhī (Hadiyah Tihrānī), a widowed nurse. Despite the relationship’s complications and Sīmā’s pregnancy and Mahmūd’s resistance to accept paternity, Mahmūd’s life is spared from ruin. Ultimately, Sīmā and their unborn child die in a fatal accident, eliminated from Mahmūd’s life. Mahmūd’s actions underscore the hypocrisy of a society that upholds religious practices like Sīghah as morally righteous while allowing men to exploit and harm women without consequence. Sīmā, a Sīghah wife, is portrayed as both socially marginalized and central to the plot, representing a threat to Mahmūd’s established marriage. The film critiques how Sīghah is manipulated by religiously-oriented men in positions of power to control and dispose of women.

Shawkarān’s release in post-revolutionary Iran in 2000 was hailed as a groundbreaking cinematic achievement, as it openly challenged traditional Iranian morals and ethics in a way no film had before. Following the Islamic Revolution, Iran underwent significant cultural shifts, impacting its film industry. The Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance (MCIG) enforced strict guidelines and censorship. This film therefore marked a turning point, pushing boundaries and sparking important conversations about women’s roles and female sexuality in Iranian society.

Figure 2: Mahmūd Basīrat (Farīburz ‛Arabniyā) and Sīmā Riyāhī (Hadiyah Tihrānī) in a scene from the film Shawkarān (Hemlock), directed by Bihrūz Afkhamī, 2000.

In the early years following the Revolution, Iranian cinema perpetuated idealized female figures, contributing to women’s real-life marginalization. Women were often portrayed as self-sacrificing mothers or obedient wives, reinforcing reductive stereotypes. However, by the late 1990s and early 2000s, the industry began to challenge these portrayals, reflecting more realistic images of women and their lives. Film scholar Mehrnaz Saeed-Vafa notes this shift, writing that films with female characters were portrayed “as selfless mothers, obedient wives and pious daughters,”3Mehrnaz Saeed-Vafa, “Iran Behind the Scenes,” In These Times, 2002. accessed May 11, 2015. https://inthesetimes.com/article/iran-behind-the-screen while Shahla Lahiji observes that the industry that had ignored women’s lives for over 50 years, by the late 1990s and early 2000s, “[started] purging itself of the notions of chaste and unchaste dolls to paint a real and realistic portrait of women and their presence.”4Shahla Lahiji, “Chaste Dolls and Unchaste Dolls: Women in Iranian Cinema Since 1979,” in The New Iranian Cinema: Politics, Representation, and Identity, ed. Richard Tapper (London: I. B. Tauris, 2008), 226. The presidency of Muhammad Khātamī and ensuing political changes allowed for more openness in Iranian cinema, including films addressing previously taboo subjects such as romantic love and sexuality.5See Hamid Naficy, “Iranian Cinema under the Islamic Republic,” American Anthropologist, New Series 97, no. 3 (1995): 548-558; Richard Tapper, “Introduction,” in The New Iranian Cinema: Politics, Representation, and Identity, ed. Richard Tapper (London: I. B. Tauris, 2008), 1-25; and Jean-Michel Frodon, “The Universal Iranian,” SAIS Review 21, no. 2 (2001): 217-224. By the 2000s, even Iranian officials began to embrace a more democratic portrayal of women such as in Shawkarān, despite persistent legal and moral taboos. Shawkarān exemplifies this shift, exploring the conflict between modernity and traditionalism in the context of women’s struggles to balance religious customs with modern rights. The film highlights gendered double standards in Iranian society, where women face stricter controls over their sexuality compared to men. In modern Iranian society, the state’s enforcement of dress codes, gender segregation, and censorship underscores the tension between tradition and modernity. It serves as a microcosm of this divided society, using a love triangle to reflect prevailing sociocultural dynamics.

Figure 3: A still from the film Shawkarān (Hemlock), directed by Bihrūz Afkhamī, 2000.

Set in post-Iran-Iraq war Iran, Shawkarān captures a period of significant political and social change. Following Ayatollah Khumaynī’s death in 1989, the country’s leadership shifted, with ‛Alī Khāmanah’ī becoming supreme leader and Hāshimī Rafsanjānī elected president. This new leadership faced the challenge of transforming the nation amidst global and domestic pressures, leading to the “Reconstruction” period. During this time, Iran focused on rebuilding economic infrastructure, renewing industries, and expanding foreign policy, while privatizing nationalized industries and encouraging foreign investment.6‛Abbās Najafī-Fīrūzjā’ī, “Durān-i sāzandagī; taḥlīlī bar tahavvulāt-i ijtimā‛ī-siyāsī-i pas az inqilāb-i islāmī (1368-1376) [The Reconstruction Period: An Analysis of Sociopolitical Developments after the Islamic Revolution (1989-1997)],” Ma‛ārif 12 (2003), accessed October 10, 2015, https://shorturl.at/0Ggdi The post-war shift from collective values to privatization exposed previously hidden corrupt tendencies, including individualism and self-interest.7Mustafā Karīmī, “Barrasī-yi naqsh va tahavvulāt-i sarmāyah-yi ijtimā‛ī-yi jāmi‛ah-yi Īrān dar durān-i difā‛-i muqaddas [An Analysis of the Role and Developments of Social Capital of Iran During the War],” Nigīn-i Īrān 9, no. 35 (2010): 70-71. Shawkarān portrays characters grappling with the instability and moral corruption brought about by these rapid changes. Mihrzad Dānish notes that the film resonated with audiences who saw their struggles reflected in the characters, particularly Mahmūd, who represents the disillusionment of those seeking to regain lost opportunities.8Mihrzād Dānish, “Yak trāzhidī-i Īrānī [An Iranian Tragedy],” Café Naqd, 2013, accessed May 8, 2015. The author has done all translations of passages from articles written in Persian. Set in 1995, amid Rafsanjānī’s privatization drive, the film centers on Mahmūd, who works for a factory controlled by the Foundation of the Oppressed, which plans to sell the factory. As Mahmūd deals with the fallout of a suspicious accident involving his boss, he is offered a bribe to sell the company to exiled Iranians. The film reveals Mahmūd’s moral compromise and his desire for social advancement, as seen in his accumulation of wealth and luxury. Afkhamī uses Mahmūd’s character to explore the conflict between religious values and personal ambition in a transforming society.

On the other hand, Afkhamī’s portrayal of Sīmā subverts traditional stereotypical representations of Iranian women by depicting her as an active, independent figure who navigates her own life despite external pressures. Sīmā’s modern lifestyle, marked by light-colored headscarves and trench coats, contrasts sharply with Mahmūd’s traditional wife, who conforms to conventional norms, wearing the chador and dark-colored clothing. As a single, widowed professional woman, Sīmā defies earlier cinematic portrayals of the ideal Iranian woman, remaining defiant in the face of social, legal, and religious disapproval.

Figure 4: Sīmā, with her light-colored headscarves and modern demeanor, stands in stark contrast to Mahmūd’s traditionally veiled wife. A still from the film Shawkarān (Hemlock), directed by Bihrūz Afkhamī, 2000.

Initially, Sīmā’s independence gives way to regret and vulnerability after facing the stigma associated with Sīghah. However, the film challenges traditional perspectives by revealing Mahmūd as the disruptor of Sīmā’s life, rather than casting her as the villain. As the film progresses, Sīmā is presented in a new light, grappling with personal challenges like her father’s drug addiction and internal conflict about traditional values. This nuanced portrayal reveals Sīmā as a victim of societal pressures and personal struggles, rather than an inherently immoral person. In contrast, Mahmūd’s devout image is undermined by his actions, exposing his lack of genuine piety. According to Āryā Qurayshī, this complexity forces viewers to confront moral ambiguities within themselves and recognize often-hidden societal evils.9Āryā Qurayshī, “Bih ta’m-i Shawkarān [With the Taste of Hemlock],” naghdefarsi, 2012, accessed May 8, 2015. https://naghdefarsi.com

The film also critiques the controversial nature of Sīghah marriages more broadly, highlighting their complex motivations and consequences. While some women enter these temporary marriages out of economic necessity, Sīmā’s decision is driven by a deep-seated desire for marriage and motherhood, influenced by patriarchal expectations. Her hope that the temporary marriage would evolve into a permanent one is ultimately dashed, leading to profound personal consequences. In contrast, Mahmūd faces no stigma for their Sīghah arrangement, underscoring the gendered double standards in such relationships. Through Sīmā’s character, Afkhamī exposes the cultural and religious constructs that shape female sexuality and societal expectations in Iran, illustrating how her body becomes a battleground for cultural and social control. This reflects broader issues of female autonomy and the negotiation of cultural norms, as Sīmā’s story reveals the ways in which women’s bodies and lives are regulated and controlled by societal expectations.

Mahmūd’s character provides insight into how male viewpoints and societal norms influence and shape women’s experiences. Initially, Mahmūd’s life appears fulfilling, but his dissatisfaction becomes apparent in a conversation with his son about Iran’s educational system, where he criticizes traditional viewpoints, revealing his desire for modernization and progress. This dialogue sets up a contrast between Mahmūd’s public persona and his underlying desires. Through various scenes, Afkhamī subtly unveils Mahmūd’s true nature, exposing his covert sexual desires and hypocrisy. Some of those moments include his lecherous gaze at a woman in a luxury car, his lustful demeanor towards a sex worker, and his similar behavior towards his wife and later Sīmā. These instances reinforce Mahmūd’s egotistical pursuit of sexual gratification, a pursuit that ultimately leads him to sacrifice Sīmā for his own self-serving motives.

The film’s historical context sheds further light on these dynamics. Following the Iran-Iraq War, Sīghah marriages became prevalent as a response to economic and moral issues. The government, under President Hāshimī Rafsanjānī, actively promoted such practices to regulate female sexuality and provide economic relief. This policy exemplifies the state’s intervention in sexual affairs, prioritizing men’s access to heterosexual relationships while restricting women’s autonomy. The state’s promotion of Sīghah and institutions like khanah-yi ‘iffat reflects a broader agenda of controlling female sexuality.10Janet Afary, Sexual Politics in Modern Iran (Cambridge: Cambridge University, 2009), 285–6. This control manifests through policies that impose moral and economic burdens on women, particularly the unmarried or widowed, rendering them powerless and voiceless under strict state surveillance while marginalizing their agency and rights. Set against this backdrop, Shawkarān offers a nuanced portrayal of the consequences of such policies on women’s lives, highlighting the tensions between individual desire and societal expectations.11Janet Afary, Sexual Politics in Modern Iran (Cambridge: Cambridge University, 2009), 345.

Afkhamī’s portrayal of Sīmā embodies the contradictory situation of women in post-revolutionary Iran. Initially desired and objectified by Mahmūd, Sīmā’s transition from a coveted object to a perceived threat highlights the patriarchal control over female bodies and the precarious position of women. Sīghah marriages in Iran are typically discreet, with no formal registration or witnesses, and can be conducted by low-level clerics or the partners themselves. Mahmūd’s secret Sīghah relationship exemplifies the inherent imbalance of power and control within this system. When faced with the choice between his formal marriage (nikāh) and his Sīghah marriage, he opts to maintain the appearance of stability. However, when Sīmā becomes pregnant, Mahmūd is entangled in a dilemma. According to Sīghah rules, a temporary wife cannot prevent pregnancy unless she uses birth control that does not interfere with her husband’s pleasure.12Janet Afary, Sexual Politics in Modern Iran (Cambridge: Cambridge University, 2009), 61; see Shahla Haeri, Law of Desire: Temporary Marriage in Shi’i Iran (New York: Syracuse University Press, 1989), 55. Sīmā, longing for motherhood, chooses not to use birth control, leading to her pregnancy and further complicating Mahmūd’s situation. A pivotal scene shows Sīmā holding a doll in a toy store, placing a pacifier in its mouth – a poignant moment that gains significance once her pregnancy is revealed. When Mahmūd learns of Sīmā’s pregnancy, he demands an abortion. He presumes that managing birth control is Sīmā’s responsibility and insists she terminate the pregnancy, despite it conflicting with his professed religious beliefs. Sīmā requests a birth certificate for the child, which would require disclosing the Sīghah marriage, but Mahmūd refuses, choosing to protect his reputation and marriage over his responsibilities to Sīmā and the unborn child.13Janet Afary, Sexual Politics in Modern Iran (Cambridge: Cambridge University, 2009), 61; see Shahla Haeri, Law of Desire: Temporary Marriage in Shi’i Iran (New York: Syracuse University Press, 1989), 55. In Iran, women cannot acquire a birth certificate for their children without a guardian’s or a father’s presence. So Sīmā needs Mahmūd’s permission/presence to be able to get a birth identification card/birth certificate for the child.

Figure 5: Sīmā, holding a doll in a toy store, places a pacifier in its mouth. A still from the film Shawkarān (Hemlock), directed by Bihrūz Afkhamī, 2000.

Afkhamī’s portrayal of Mahmūd exposes the hypocrisy embedded in his religious and moral principles, which are disregarded when they conflict with his personal convenience. The film critiques the broader societal and legal context where Sīghah marriages are regulated to benefit men while marginalizing women. The stigmatization of Sīghah women and their bodies is central to this critique, highlighting a double standard in how these relationships are perceived. Despite the legality of Sīghah, women face societal condemnation and isolation, while men like Mahmūd manipulate religious norms to continue living as they please. Sīmā’s plight, abandoned by Mahmūd and rejected by her father, illustrates the harsh consequences for women who defy societal expectations. Through Mahmūd’s actions, Afkhamī critiques how Islamic law can be distorted to serve patriarchal interests, illustrating the systemic issues that lead to women’s stigmatization and erosion of autonomy.14Maryam Basīrī, “Talkhtar az Shawkarān [Bitter than Hemlock],” Payām-i Zan, 2014, accessed May 8, 2015, http://payamezan.eshragh.ir/article_50919.html

The film explores the intersections of Iranian sociocultural, religious, political, and economic institutions in shaping women’s experiences, particularly focusing on how female sexuality is regulated within a culture that prioritizes male sexuality. Sīmā’s transformation from a vibrant and courageous woman to a figure of pity illustrates the oppressive nature of societal expectations. Her father represents traditional views, pressuring her to marry and bear children despite her caretaking responsibilities (which include providing him with opium). This pressure reflects the entrenched societal belief that a woman’s worth is tied to her ability to fulfill familial and reproductive roles. Sīmā internalizes these societal norms, leading to feelings of guilt and shame regarding her sexuality and motherhood. The film critiques the double standards in the treatment of women, highlighting how societal expectations force women into roles that often result in stigmatization and marginalization.

The film also represents Iran’s struggles between tradition and modernity through various aesthetic choices and motifs. Afkhamī uses the motif of the traveling car to symbolize Iran’s struggle between tradition and modernity. The car becomes a liminal space where Mahmūd navigates between his traditional life in Zanjān and the cosmopolitan environment of Tehran. His ease in transitioning between these worlds contrasts with the rigidity faced by women, who suffer regardless of their choices. The car represents the male privilege of maneuvering between different spheres with little consequence, while women are bound by stricter societal constraints. Afkhamī uses the car as a metaphor to highlight the lack of agency women possess in navigating between modernity and tradition in a patriarchal society. Both Tarānah (Mahmūd’s nikāh wife) and Sīmā, despite their differing positions and choices, remain victims of a male-dominated system. Tarānah embodies the ideal traditional wife, dedicated to her home and family, primarily depicted within the confines of her house in Zanjān. Her lack of autonomy is emphasized by her absence from driving scenes, and her only appearance in a vehicle is when Mahmūd takes her out, illustrating her dependence. Sīmā, in contrast, is portrayed as an independent woman actively exercising her agency. She is shown driving, symbolizing her mobility and freedom compared to Tarānah. However, Sīmā’s independence ultimately leads to her marginalization and rejection. A poignant scene depicts Sīmā’s anguish as she drives, culminating in a fatal accident. This is juxtaposed with Mahmūd’s indifferent drive to confront her father, emphasizing Sīmā’s victimhood. The film’s final scenes underscore the tragic outcomes for both women. Sīmā, abandoned and pregnant with a stigmatized child, is left to grieve and ultimately die alone. Her sorrowful drive, accompanied by a mournful score, contrasts sharply with the concluding image of Mahmūd and his wife in their car, where Sīmā’s death is reduced to a fleeting, inconsequential event. The camera’s focus on Mahmūd as he drives away reflects how the male perspective remains dominant, with Sīmā’s suffering relegated to the background. The cinematography in the film skillfully illustrates the shifting power dynamics between the two women and Mahmūd. Initially, Sīmā’s independence is highlighted through camera angles that emphasize her autonomy. However, as Sīmā transitions into a Sīghah marriage, her social status and agency diminish. The camera’s focus shifts, portraying Sīmā’s increasing dependence on Mahmūd and her loss of former independence. This visual representation underscores how societal expectations erode women’s agency, particularly when they conform to traditional roles.

Figure 6: Mahmūd driving alone highlights his wife’s absence and lack of autonomy. A still from the film Shawkarān (Hemlock), directed by Bihrūz Afkhamī, 2000.

Afkhamī uses Sīmā’s journey to illustrate how personal choices are heavily politicized within intimate relationships in modern Iran. Sīmā’s efforts to align with traditional ideals highlight how cultural and religious expectations shape and constrain women’s lives. The film concludes with Mahmūd’s unchanged demeanor, symbolizing not just his personal shortcomings but reflecting broader societal issues. Afkhamī’s portrayal of the contradictions and societal expectations surrounding women, particularly in the context of Sīghah, sheds light on the broader issues of gender inequality and societal control.

Political Manipulation and Women’s Disposability

Farahbakhsh’s Zindagī-yi Khusūsī explores the intersection of private and political spheres through the story of Ibrāhīm Kiyānī (Farhād Aslānī), a high-profile Reformist politician struggling with his sexual desires.15Muhammad Husayn Farahbakhsh, Dir. Zindagī-yi Khusūsī [Private Life]. Salām Cinema/ Sūrah Cinema, 10 March 2012. The film exposes the religious and political hypocrisy in Sīghah, highlighting gender-based double standards and the price women pay to conceal male moral failings. Ibrāhīm, a former radical religious zealot turned conservative Reformist politician, initiates a Sīghah relationship with Parīsā (Hāniyah Tavassulī) to fulfill his desires while maintaining his traditional marriage. Like Shawkarān, Zindagī-yi Khusūsī features educated, financially independent woman seeking legitimate means of having children, only to face violent repercussions due to societal and patriarchal constraints. Both films expose how Sīghah serves male desires and maintains social and political power, marginalizing women. Similar to Sīmā’s predicament in Shawkarān, when Parīsā becomes pregnant, Ibrāhīm pressures her into an abortion, and her refusal leads to a violent confrontation, culminating in her murder. The film critiques the hypocrisy in Sīghah through Ibrāhīm’s character, whose engagement in the practice contradicts his proclaimed moderate, reformist views. By using Sīghah to satisfy his desires, Ibrāhīm exemplifies how religious and political leaders manipulate institutions to their advantage while maintaining a veneer of moral integrity. The film contrasts the treatment of male and female protagonists, highlighting the disposability of women within patriarchal structures. Parīsā’s transition from desired lover to discarded victim emphasizes the gendered double standards in Sīghah, where her reproductive capacity becomes a liability, and challenging patriarchal norms proves lethal. Zindagī-yi Khusūsī shares thematic similarities with Shawkarān in its portrayal of the tragic fate of Sīghah women.

Figure 7: Ibrāhīm Kiyānī (Farhād Aslānī) and Parīsā (Hāniyah Tavassulī) in a scene from the film Zindagī-i Khusūsī (Private Life), directed by Muhammad Husayn Farahbakhsh, 2011.

Farahbakhsh’s cinematic portrayal provides a critical lens on the legacies of Iran’s 1979 revolution, addressing political and sexual taboos while presenting a blend of romance and ideological critique. The film explores Iran’s complex political landscape, where the dichotomy between Reformists and Hardliners is not clear-cut. It captures the tensions following Khumaynī’s death in 1989, which saw the emergence of competing Reformist and conservative factions.16Ramin Jahanbegloo, “Pressures from Below.” Journal of Democracy 14, no. 1 (2003): 127–9. This context influenced Iran’s film industry, reflecting the Reformist discourse that sought to reconcile traditional Islam with modern democratic principles. Between 1989 and 2011, Iranian cinema played a crucial role in reflecting and shaping mainstream political discourse. During Khātamī’s presidency, film censorship relaxed, leading to provocative films that sparked early reformist discourses. However, Ahmadīnizhād’s election in 2005 marked a return to conservative censorship, yet factionalism and debates continued to influence filmmakers.17Blake Atwood, Reform Cinema in Iran: Film and Political Change in the Islamic Republic (New York: Columbia University Press, 2016), 14-7.

Zindagī-yi Khusūsī critiques both revolutionary extremists and reformists, portraying Ibrāhīm’s shift from a radical conservative to a reformist politician and highlighting inherent contradictions and hypocrisy in their policies and approaches. By focusing on political factionalism and personal moral failings, the film critiques superficial political transformations and ongoing conflicts in Iranian society. Muhammad Husaynī notes that the film’s exploration of these themes was seen as new and impactful in Iranian cinema, offering a critical perspective on post-revolutionary Iran’s complexities.18Muhammad Husaynī, “Nigāhī bih Gasht-i Irshād va Khusūsī [An Analysis of Gasht-i Irshād and Khusūsī],” Haraz News, May 7, 2012. accessed June 30, 2016. https://haraznews.ir/ Unlike Shawkarān’s post Iran-Iraq War setting, Zindagī-yi Khusūsī explores the 2010s, marked by heightened individualism and political factionalism. The film critiques the attempts to control women’s bodies through legal mechanisms, highlighting Sīghah’s complex role in Iranian society.

Zindagī-yi Khusūsī is set in the era under Mahmūd Ahmadīnizhād’s presidency. This period saw Sīghah become a contentious issue, particularly in 2007, when the interior minister encouraged youth to enter Sīghah marriages without parental consent, sparking public backlash.19Frances Harrison, “Iran Talks Up Temporary Marriage,” BBC, June 2, 2007, accessed June 30, 2016. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/6714885.stm Ahmadīnizhād later clarified that the advice was religious, not state-endorsed.20Marjānah Fātimī, “Buhrān-i jinsī va da‛vā bar sar-i yak rāh-i hall: bāz-khanī-i parvandah-yi izdivāj-i muvāqqat dar bīst sāl-i akhīr [Sexual Crisis and Altercation Over a Solution: Rereading the Discourse on Temporary Marriage in the Past Twenty Years],” Panjarah 27 (2010): 48-49. In 2008, the Iranian Parliament proposed reforms to the Family Protection Law, including Article 23, which would have removed the requirement to register Sīghah marriages, nullifying women’s and children’s legal and financial rights. Women’s rights activists strongly opposed the bill, leading to delays and revisions. Although Article 23 was eventually removed, the debate highlighted the state’s attempts to control women’s bodies through legal mechanisms, underscoring the ongoing struggles for women’s rights in Iran.21Glonaz Esfandiari, “Controversial Family Bill returns on Iranian Parliament Agenda,” Radio Free Europe, August 24, 2010, accessed June 30, 2016. https://www.rferl.org/a/Controversial_Family_Bill_Returns_To_Iranian_Parliaments_Agenda/2136632.html; See also Arzoo Osanloo, “What a Focus on ‘Family’ means in the Islamic Republic of Iran.” In Family Law in Islam: Divorce, Marriage and Women in the Muslim World, ed. Maaike Voorhoeve. (London: I.B. Tauris, 2012), 51-76.

Zindagī-yi Khusūsī critiques the state’s use of Sīghah as a solution to social and sexual problems, illustrating how it marginalizes women and erodes traditional family structures. The film exposes the consequences of Sīghah, particularly for women like Parīsā, who are left without legal and financial protections. It expands on the narrative of Shawkarān, exploring the exploitation of Sīghah by high-profile political figures in the Reformist Islamic Republic. Ibrāhīm, a high-ranking political figure, commits murder to conceal his corruption, illustrating the broader theme of powerful individuals using their resources to escape accountability.

Figure 8: A still from the film Zindagī-i Khusūsī (Private Life), directed by Muhammad Husayn Farahbakhsh, 2011.

The film opens with Ibrāhīm, a bearded cleric, participating in the 1980s Islamic Revolution. He and his comrades attack a cinema, destroying posters and engaging in violence against women deemed improperly veiled. Ibrāhīm’s actions reflect the early revolutionary zeal and desire to purge Iranian society of pre-revolutionary influences.22Hamid Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema, Volume 3: The Islamicate Period, 1978–1984 (Durham, London: Duke University Press, 2012), 16. Ibrāhīm’s pushing the tack might be a reference to Akbar Ganjī, who was nicknamed Akbar Pūniz (Akbar the Tack) for pushing tacks to poorly veiled women’s foreheads in the years after the revolution to hold their hijab in place. While he was a supporter of the Islamic revolution at a young age, in the 1990s, he became disillusioned, protested, published stories about the murders of dissident authors, and consequently spent time in Ivīn Prison from 2001 until 2006. Ganjī has since become an Iranian pro-democracy journalist, writer, and political dissident. Imam Zamān or al-Mahdi is the Twelver Shi’a ultimate savior of humanity who has vanished from the world at a young age but will emerge to bring justice and peace. These acts symbolize the broader conflict between revolutionary ideals and the remnants of the old regime. The film cuts to three decades later when Ibrāhīm has transformed into a sophisticated, suit-wearing government official with a neatly trimmed beard and a standard accent. This change symbolizes his attempt to distance himself from his past and project a new image, despite the superficial nature of his reforms. From a sociolinguistic perspective, accents signify regional, socioeconomic, or ethnic identity. Ibrāhīm’s shift from a regional to a standard accent suggests a deliberate effort to conceal his origins and present himself as part of the elite. However, this transformation ultimately proves to be a façade, highlighting the tension between his revolutionary past and his current persona.

The next scene shows Ibrāhīm resigning from his job amidst accusations of inciting political discord. He threatens to reveal sensitive information. However, his shift to editing Mardum-i Imrūz and role as a reformist critic represents a significant ideological transformation. Ibrāhīm’s critique of conservative fundamentalists and reformists is evident in his exchange with Saffāriyān, a character likely representing Husayn Sharī‛atmadārī. Saffāriyān accuses Ibrāhīm of undermining the regime, while Ibrāhīm counters that Saffāriyān’s accusations are a means of consolidating power and ignoring the populace’s suffering. The dialogue is rich with foreshadowing of Ibrāhīm’s ultimate betrayal of Parīsā, illustrating the film’s exploration of superficial political reform and persistent corruption. Ibrāhīm’s actions underscore the hypocrisy within Iranian politics, where outward reformist stances mask underlying power struggles and personal motivations. The film provides a critical examination of political and personal transformation, using Ibrāhīm’s character to explore themes of superficiality, power, and corruption. His self-righteous condemnation of Saffāriyān, where he accuses him of extremism, unethical behavior, and hypocrisy, reflects a broader critique of the political landscape.

Figure 9: A still from the film Zindagī-i Khusūsī (Private Life), directed by Muhammad Husayn Farahbakhsh, 2011.

Parīsā’s portrayal in Zindagī-yi Khusūsī is complex and multifaceted, challenging the simplistic binaries embedded in the Madonna-whore dichotomy. ‛Alīrizā Pūrsabbāgh argues that “Parīsā’s introduction as an easy-going and unrestrained woman who does not deserve having a family, while also demanding marriage and family from Ibrāhīm in the second half of the film, is also contradictory.”23‛Alīrizā Pūrsabbāgh, “Nigāhī bih fīlm-i ‘Zindagī-yi khusūsī’ [An Analysis of Zindagī-yi Khusūsī],” Tebyan. May 23, 2013, accessed June 30, 2016. https://shorturl.at/lTlqx This shift reflects her evolving desires and the film’s commentary on the limitations placed on women’s autonomy. Parīsā’s character embodies the post-revolutionary generation, shaped by Iran’s social, economic, and political changes. As a member of this generation, she forges a new identity amidst shifting societal norms, asserting her rights and striving for gender equality.24Pardis Mahdavi, Passionate Uprisings: Iran’s Sexual Revolution (Stanford CA: Stanford University Press, 2009), 446. Parīsā and Ibrāhīm’s relationship subverts Sharia law’s norms; they use Sīghah to legitimize their sexual relationship rather than adhering to the broader religious framework. Through Parīsā, the film critiques societal norms that stigmatize women who assert their independence while depicting their struggles for equal rights and personal fulfillment. The film presents Parīsā and Ibrāhīm’s relationship as a microcosm of broader societal conflicts, using Ibrāhīm’s character to challenge viewers to question the authenticity of political reform and its effects on individual lives. It explores the complexities faced by Iran’s younger generation, particularly their struggle for both personal and political autonomy. Ibrāhīm’s suggestion to use Sīghah to legitimize his relationship with Parīsā, a conservative approach to extramarital relationships, highlights his internal conflict, as he privately attempts to break free from those same traditional norms.

The film exposes Ibrāhīm’s contradictions, particularly through his interactions with Parīsā. When she confronts him about his past affiliation with the Islamic Revolutionary Guard (IRGC) and his subsequent critical stance toward former comrades, Ibrāhīm’s dismissive response reveals a power struggle, rather than a genuine ideological shift. Furthermore, Farahbakhsh’s portrayal of Ibrāhīm’s relationship with his wife, Furūgh, reveals the underlying motives behind his decision to engage in Sīghah with Parīsā. This choice stems from his dissatisfaction with his conventional marital life and his desire for sexual variety. Parīsā’s suspicion that Ibrāhīm is more attracted to her for sexual novelty than genuine affection deepens the layers of his hypocrisy. For Ibrāhīm, Sīghah serves as a convenient cover for his extramarital desires.

Figure 10: A still from the film Zindagī-i Khusūsī (Private Life), directed by Muhammad Husayn Farahbakhsh, 2011.

Ibrāhīm’s power play is fully exposed when he accuses Parīsā of infidelity upon learning of her pregnancy, revealing his willingness to manipulate accusations for self-preservation. Although he claims to support a modern, non-violent interpretation of Islam, his actions betray ulterior motives. His immediate reaction is to dismiss their relationship as inconsequential, disregarding the emotional and ethical implications of Parīsā’s pregnancy. His refusal to acknowledge paternity or provide a birth certificate further underscores his attempt to evade responsibility.25Historically, Islam has held a different stance on birth control and abortion compared to Christianity. Medieval Islamic philosophers and theologians, including Ghazali, viewed conception as a contract between a man and a woman, requiring mutual consent. They believed that ensoulment occurs after 120 days (approximately four months). This perspective reflects a relatively permissive attitude toward abortion, allowing it with the husband’s consent prior to ensoulment. Ibrāhīm’s hypocrisy becomes even more apparent when he suggests abortion as a solution, contradicting his previous claims that women should have control over their own bodies. His violent actions against Parīsā and her unborn child, justified under the guise of protecting his reputation, expose the superficiality of his moral stance. The dialogue between them highlights his attempts to reconcile his behavior with religious justification, yet his deceitfulness ultimately lays bare his manipulative tendencies.26Eskandar Sadeghi-Boroujerdi, “‘Zendegi-ye Khosoosi”: The ‘Private Life’ of an Iranian Reformist,” PBS. August 9, 2012, accessed, 30 June 2016. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/tehranbureau/2012/08/cinema-zendegi-ye-khosoosi-the-private-life-of-an-iranian-reformist.html Parīsā’s struggle with Ibrāhīm highlights the precarious legal status of Sīghah unions, where men can easily deny paternity, leaving women to navigate burdensome legal obstacles. Parīsā, however, resists his coercion. Her refusal to undergo an abortion and her direct confrontation with Ibrāhīm challenge the stereotypical portrayal of women as passive or dependent in post-Revolution Iran. The film intricately ties reproductive rights to the archetype of the vengeful “other woman,” with Parīsā’s fight for control over her pregnancy contrasting sharply against societal perceptions of her as mentally unstable. By asserting her right to make decisions about her own body, she embodies strength and autonomy, standing in stark contrast to Ibrāhīm’s outdated and self-serving views. Through Parīsā’s defiance and Ibrāhīm’s deception, the narrative reveals broader issues of gender dynamics and the struggle to navigate personal and political identities within a repressive society. Through these portrayals, the film critiques the constraints placed on women within a patriarchal society and the complex dynamics that shape their autonomy and resistance.

Figure 11: Ibrāhīm lures Parīsā into his car, offers her water, and then fatally shoots her. A still from the film Zindagī-i Khusūsī (Private Life), directed by Muhammad Husayn Farahbakhsh, 2011.

Ultimately, Ibrāhīm acknowledges his paternity but his deceitful pretense of accepting responsibility for Parīsā and their unborn child represents nothing more than a façade of reform. His ultimate betrayal is manifested by luring Parīsā into his car, offering her water before fatally shooting her, and setting her body on fire. This gruesome act shows the lengths he will go to protect his public image and political career, revealing the superficiality of his claims to reform. His hallucinations and emotional breakdown after he shoots Parīsā reveal internal conflict. The film critiques Ibrāhīm’s conflation of personal and political morality. His moral degeneration reflects broader moral decay within the reformist movement and its complicity in systemic violence and injustice. Parīsā’s role as a Sīghah woman illustrates paradoxes and contradictions in gender relations, and the harsh consequences of defiance, as she is reduced to a problem that must be eradicated. Parīsā’s tragic fate symbolizes broader systemic issues faced by women, particularly those in Sīghah unions, who must navigate legal ambiguity and societal prejudice. Zindagī-yi Khusūsī serves as a powerful indictment of personal and political corruption, exposing grim reality of gender dynamics and superficiality of political reformism.

Figure 12: Burning Parīsā’s body and his ensuing hallucinations expose Mahmūd’s inner collapse. A still from the film Zindagī-i Khusūsī (Private Life), directed by Muhammad Husayn Farahbakhsh, 2011.

Secularism, Emotional Vulnerability, and a Shift in Consequences

In Dar Intihā-yi Shab (In the End of the Night, 2023), directed by Āydā Panāhandah, the lives of Bihnām (Pārsā Pīrūzfar) and Māhī (Hudā Zayn al-Ābidīn) are upended by a seemingly minor incident that sets them on a path towards separation. As they struggle with financial, emotional, familial, and sexual issues, Māhī’s confusion and indecision are expertly captured, while Bihnām is portrayed as a complex, middle-aged man entangled in a web of relationships. Interestingly, their divorce is not sparked by physical abuse, infidelity, or addiction, but rather Māhī’s unfulfilled sexual and emotional needs, which render life with Bihnām unsustainable. Following their divorce, Bihnām enters a brief Sīghah marriage with Surayā, his neighbor. Through this narrative, Panāhandah masterfully explores pressing social issues, including the clash between tradition and modernity, women’s rights, unfulfilled desires, Sīghah marriages, and divorce. The series presents a nuanced portrayal of a middle-class family’s struggles, delving into economic concerns, and the darker aspects of relationships and the challenges faced by both men and women post-separation in contemporary Iran.27See Bābak Javād, “Dar Intihā-yi Shab: sabukī-yi tahammul-nāpazīr-i hastī [Dar Intihā-yi Shab: The Unbearable Lightness of Being],” Filmnet, September 12, 2023, accessed February 8, 2025, https://filmnet.ir/news/در-انتهای-شب-سبکی-تحملناپذیر-هستی; Farhād Khālidī Nīk, “Vāqi‛garā’ī-i maḥẓ dar siriyāl-i Dar Intihā-yi Shab [Pure Realism in the Series Dar Intihā-yi Shab],” Filmnet, September 15, 2023, accessed February 8, 2025, https://filmnet.ir/news/واقعگرایی-محض-در-سریال-در-انتهای-شب.

Figure 13: Bihnām (Pārsā Pīrūzfar) and Māhī (Hudā Zayn al-Ābidīn) in a scene from the film Dar Intihā-yi Shab (In the End of the Night), directed by Āydā Panāhandah, 2023.

Dar Intihā-yi Shab breaks away from the conventional portrayals of socioeconomic classes in Iranian television series by focusing on the middle cultural class. The series’ central theme revolves around the characters’ doubts between past and future, leading to indecision. Economic concerns, a pressing issue for contemporary Iranians, erode hope for the future and foster attachment to the past dreams. The series illustrates how during precarious socioeconomic situations, memories and desires anchor individuals to the past, hindering progress.28Parniyān Mustawfī, “Naqd va barrasī-i siriyāl-i Dar Intihā-yi Shab az Āydā Panāhandah [Review of the Series Dar Intihā-yi Shab by Āydā Panāhandah],” Maajara, January 8, 2024, accessed February 8, 2025, https://maajara.com/Blog/158/نقد_و_بررسی_سریال_در_انتهای_شب_از_آیدا_پناهنده In tandem with the economic malaise, the characters in Dar Intihā-yi Shab are haunted by a deep sense of emotional and sexual longing, yearning for past desires that have been left unfulfilled. Dar Intihā-yi Shab demystifies love, moving beyond romantic illusions to pose a profound question: what remains when tradition, God, and love are stripped away? The show presents a dark world where relationships are extinguished, and life becomes a perilous journey. In the series, turbulent relationships, lies, betrayal, and love intertwine, while moments of solitude, shared looks, smiles, tears, and the pain of loneliness are used as ways to mend the lies and betrayals.29Javād Kāshī, “Tahlīl-i yak jāmi‛ah-shinās az siriyāl-i ‘Dar antihā-yi shab’ [A Sociologist’s Analysis of the Series Dar Intihā-yi Shab],” Tabnak, September 10, 2023, accessed February 8, 2025, https://www.tabnak.ir/fa/news/1250122/تحلیل-یک-جامعه-شناس-از-سریال-در-انتهای-شب.

In Dar Intihā-yi Shab, the critique of toxic masculinity is evident through the portrayal of Bihnām as a selfish and neglectful husband. Māhī openly condemns Bihnām’s behavior, highlighting his shortcomings for the viewer. The narrative sheds light on Māhī’s sexual unfulfillment which intensifies the marital conflict. Bihnām’s carelessness and thoughtlessness are starkly contrasted with Māhī’s diligence in managing household finances and her concern for her family’s needs. The conflict reaches a boiling point due to Bihnām’s indifference towards their son’s well-being, who has ADHD, and Māhī’s emotional and sexual needs. The series emphasizes the significance not only of economic security in marriage, but also emotional and sexual rights, positing these issues to be as valid as other legitimate reasons for divorce such as infidelity and physical abuse.

Figure 14: A still from the film Dar Intihā-yi Shab (In the End of the Night), directed by Āydā Panāhandah, 2023.

Focusing on emotional and sexual fulfillment, Dar Intihā-yi Shab diverges from the more typical plotlines found in Shawkarān and Zindagī-yi Khusūsī, reflecting a significant shift in Iranian media. By prioritizing personal desires over traditional societal constraints, the film speaks to a broader historical moment in Iran where individual expression, especially concerning emotions and sexuality, is gaining visibility despite cultural and political challenges. This shift mirrors the evolving discourse around gender, relationships, and personal autonomy, where younger generations increasingly challenge long-held norms. The series’ focus on these themes positions it as a commentary on the tensions between modernity and tradition in a yet again transforming society.

Māhī’s sudden proposal of divorce is met with Bihnām’s calm but enthusiastic acceptance. The film glosses over the court proceedings, instead skipping straight to the aftermath. This unconventional approach bypasses the typical stages of divorce narratives, presenting a rapid and smooth separation process. In contrast, the film delves into the psychological stress that follows separation, particularly for women. Māhī grapples with the emotional fallout, while Bihnām appears unaffected, swiftly entering a Sīghah marriage with Surayā, their divorced neighbor. Bihnām’s brief union with Surayā exposes his insecurities and sense of patriarchal entitlement. Seeking to prove his virility, he uses Surayā to validate his masculinity. When he ends the relationship, he callously remarks, “he doesn’t want to create another Māhī out of her,” revealing his awareness of Māhī’s unfulfilled desires and his determination to avoid empowering another woman. Ultimately, Bihnām emerges unscathed, while Surayā faces the devastating consequences of losing custody of her child, a harsh reminder of the societal penalties imposed on women who assert their desires and needs even under the legally and religiously sanctioned Sīghah.

Figure 15: Bihnām enters into a temporary marriage with Surayā, his recently divorced neighbor. A still from the film Dar Intihā-yi Shab (In the End of the Night), directed by Āydā Panāhandah, 2023.

Another notable deviation in Dar Intihā-yi Shab is the reversal of traditional dynamics seen in Shawkarān and Zindagī-yi Khusūsī, where men, married to conventional wives, lusted after educated and independent women for Sīghah. In Dar Intihā-yi Shab, the opposite occurs: Bihnām, who is married to the independent and educated Māhī, is drawn to the more traditional Surayā after his divorce. This inversion serves as a commentary on the state of progressivism and its potential backlash. This tension underscores a critique of how societal advancements in gender roles and independence are fragile or unsustainable in a shifting cultural landscape. By flipping the traditional female roles, the film explores the complexities of modern Iranian society, where the allure of progress clashes with a longing for traditional values: the past is always in conflict with the present. The contrast between Māhī and Surayā critiques the delay in changing men’s traditional attitudes toward women regardless of claims of progressivism. Surayā serves as a foil to Māhī’s character, highlighting different ways women navigate relationships and societal expectations.30“Āyā ‘Dar Intihā-yi Shab’ rawzanah-yi umīdī mītābad? [Does a Ray of Hope Shine at the End of the Night],” Fararu, September 5, 2023, accessed February 8, 2025, https://fararu.com/fa/news/746716/آیا-در-انتهای-شب-روزنه-امیدی-میتابد.

Figure 16: A still from the film Dar Intihā-yi Shab (In the End of the Night), directed by Āydā Panāhandah, 2023.

Dar Intihā-yi Shab poignantly portrays the decline of moral virtues and social status within the middle class, as the couple’s struggle to maintain their social status and cultural markers amidst economic instability ultimately leads to the erosion of their humanity.31Parīsā Kadīvar, “Tabaqah-yi mutavassit dar intihā-yi shab [The Middle Class in Dar Intihā-yi Shab],” Ketabnews, October 1, 2024, accessed February 8, 2025, https://ketabnews.com/fa/news/22281/طبقه-متوسط-در-انتهای-شب-پریسا-کدیور. The series delves into the struggles of Māhī and Bihnām, an intellectual couple, whose individuality is suffocated by their marriage. Māhī feels trapped and responsible for Bihnām’s failures, while Bihnām feels suffocated by the daily grind and loss of his artistic identity. Panāhandah challenges traditional norms in marital relationships and patriarchal family structures, highlighting the struggle for independence and identity. Māhī represents women seeking dignity and escape from decline, while Bihnām reflects the struggle to maintain social status. The series challenges traditional beliefs about the idea of sacrificing the present for an uncertain future. However, amidst this tumultuous relationship, Surayā becomes a collateral victim, caught in the web of Māhī and Bihnām’s struggles. Her Sīghah to Bihnām serves as a stark reminder of the consequences of patriarchal entitlement and the objectification of women. As the couple’s relationship unravels, Surayā’s character is left to face the devastating consequences of being a pawn in their game of marital discontent.

Conclusion

Zindagī-yi Khusūsī, Shawkarān, and Dar Intihā-yi Shab critically examine identity and societal expectations through relationships, exposing the patriarchal structures that exploit women, particularly through Sīghah. While Shawkarān and Zindagī-yi Khusūsī depict pregnancy as a trigger for violent repression, Dar Intihā-yi Shab portrays Surayā losing the custody of her child due to her temporary marriage, highlighting how women are forced to sacrifice motherhood for fleeting relationships. The films condemn the manipulation of religious practices and political status for male benefit, with Zindagī-yi Khusūsī and Shawkarān featuring independent women who face violence for seeking legitimate motherhood, while Dar Intihā-yi Shab’s Surayā, a traditional woman, loses custody of her child. Shawkarān and Zindagī-yi Khusūsī critique Sīghah as a tool for male dominance, whereas Dar Intihā-yi Shab reflects on broader sociopolitical dynamics, critiquing modernism and secularism. Collectively, they all challenge patriarchal norms, showing how Sīghah enables men to exploit women’s bodies and emotions while reinforcing social power imbalances. Though Surayā, Parīsā, and Sīmā have distinct experiences, they all enter Sīghah seeking fulfillment, only to face further oppression, underscoring how women’s desires are policed and controlled within a society rife with sexual repression and hypocrisy.

Shawkarān, Zindagī-yi Khusūsī, and Dar Intihā-yi Shab share similar themes and critiques of patriarchal norms in Iranian society. However, a notable distinction lies in their direction: the first two films are made by male directors, while Dar Intihā-yi Shab is directed by a woman. This difference in perspective results in distinct portrayals of women’s experiences, particularly their unfulfilled sexual and emotional desires, within romantic relationships. Another significant difference is that in the first two films, the men are more religiously oriented, while in the contemporary series, a highly educated, middle-class, secular, and intellectual man such as Bihnām still perpetuates patriarchal dynamics – this time under the façade of progressivism. Unlike characters in earlier films, Bihnām is neither religiously oriented nor a politically high-profile figure. However, Surayā still suffers albeit a different consequence: loss of her child custody. Despite championing modernity and enlightenment, men like Bihnām leverage temporary marriages to satiate their desires and maintain control over women’s bodies and agency. This disconnect highlights the deeply ingrained nature of patriarchal mindset, which coexists with progressive values and often hides behind intellectualism and secularism. Spanning different periods in Iran’s history, all three collectively reveal a disturbing timelessness in the repercussions faced by Sīghah women. From the post-revolutionary era to the present day, Sīghah women’s lives have been consistently governed by patriarchal norms, leading to similar, and often tragic, consequences. In all three works, Sīghah marriages serve as a reminder of the enduring societal constraints limiting women’s agency, autonomy, and desire.

Cite this article

This article examines the portrayal of sigheh (temporary marriage) in Iranian cinema and television, focusing on Afkhami’s Showkaran (2000), Farahbakhsh’s Zendegi-ye Khosusi (2011), and Panahandeh’s Dar Entehaye Shab (2023). Through these narratives, a recurring theme emerges: the exploitation and marginalization of women under religious structures that claim legitimacy while reinforcing gender inequality.

Showkaran and Zendegi-ye Khosusi portray religiously devout male protagonists who manipulate sigheh for personal gain, ultimately leading to the deaths of the women involved once they become pregnant. In contrast, Dar Entehaye Shab presents a more secular figure, Behnam, whose brief sigheh with Soraya results not in violence but in the loss of her child custody—another form of dispossession.

Together, these works reveal how sigheh, framed as a religiously sanctioned practice, often functions as a vehicle for control, erasure, and gendered harm. Despite their differing contexts, the narratives collectively challenge the socioreligious mechanisms that undermine women’s autonomy in the name of tradition.