The Morning of the Fourth Day: The Iranian New Wave and its À Bout de Souffle

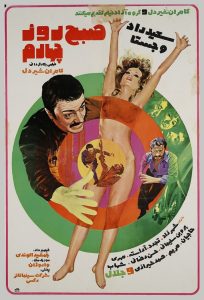

Figure 1: Poster for the film The Morning of the Fourth Day (Subh-i Rūz-i Chahārum), directed by Kāmrān Shīrdil, 1972.

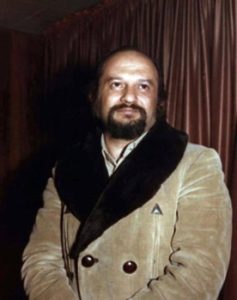

Figure 2: Portrait of Kāmrān Shīrdil, Iranian filmmaker.

Revolutionary for its time, Jean Luc Godard’s À Bout de Souffle (Breathless, 1960) is by all accounts considered a cornerstone of the modern cinema. It also initiated a historical rejuvenating movement in the French cinema (Nouvelle vague/The French New Wave) which left a worldwide impression. Godard’s debut feature spurred filmmakers of various nations to rally and concert their efforts around the similar notion of breathing a new life into their national film industries. It is no wonder that Godard’s film has been subject to adulation through cinematic remakes. Cinephiles are probably better acquainted with Jim McBride’s American remake (Breathless, 1983), which carried the English title of Godard’s film. Fewer of them have heard of a similar undertaking that preceded McBride’s film by a decade, when a young Iranian filmmaker named Kāmrān Shīrdil offered his own version of À Bout de Souffle set in contemporaneous Iran. For all its faithfulness the film titled Subh-i Rūz-i Chahārum (The Morning of the Fourth Day, 1972) also exhibited patent links to the local cinematic traditions. As with many other pictures from the pre-1979 revolution era, The Morning … has been shrouded in relative obscurity due to limited access, especially by non-Persian speakers, despite the well-established reputation of its helmer as a documentarist.

When viewed in the broader context of Iranian national cinema, Shīrdil’s remake exhibits itself as a fascinating case to study. This film is often associated with the Iranian New Wave (Mawj-i naw-i sīnimā-yi Īrān). This movement, whose nomenclature unmistakably harkens to inspirations by the French model, was indeed at its peak when the film was made. The film, therefore, seems to have been doubly inscribed with links to The French New Wave on both textual (as a remake of a film associated with it) and contextual levels (as representative of a film movement inspired by it); it effectively acts as a direct point of comparison between the two national film movements in France and Iran.

Figure 3: Amīr played by Sa‛īd Rād in a scene from the film The Morning of the Fourth Day (Subh-i Rūz-i Chahārum), directed by Kāmrān Shīrdil, 1972.

Indeed, The Morning…, as I will show in my following examination of the film, very much characterizes the Iranian New Wave, its influences and artistic mission and various tendencies running through it. More than a mere exemplar of a transnational transformation of a cinematic text, The Morning… also reflects the heterogeneity of a larger cinematic movement to which it belongs; a movement whose existence and definition have remained a bone of contention due to this very heterogeneity. My main goal in this article is to examine The Morning … and identify the heterogeneity of its elements and influences, which, in a synecdochical sense, also applies to the Iranian New Wave. To this end, I will begin by overviewing some issues and doubts surrounding the general notion of the Iranian New Wave, leading to denial of its existence or a call for its redefinition. I will then move on to examine and analyse The Morning… as one representative of the movement with patent ties to the French New Wave. Putting Shīrdil’s version next to the original film, I will show to what degree the so-called deviations of the Iranian remake can be explained by influences from local conventions and practices, including commercial cinema. Showing the transformation of Godard’s original in the context of the Iranian New Wave into something different from an arthouse film affair, my intention is to suggest that this heterogeneity could be appreciated as the distinct taste of this movement, rather than something delegitimizing this designation or a cause for not applying it in its original meaning.

The Iranian New Wave and the challenges to its definition

Despite its common use in film literature, the Iranian New Wave seems to have remained a somewhat slippery concept. Far from being unanimously acknowledged, its existence as a bona fide cinematic movement has been contested. In a revisionist fashion some critics and scholars have questioned the benefit of applying such a designation altogether.1For example: Hasan Husaynī in a series of lectures recorded and released as a DVD boxset titled Fīlmfārsī (Tehran: Sāqī, 2013). Meanwhile there seems to be some implicit efforts to redefine it in a way that would fit the international arthouse cinema.2The Iranian New Wave 1960–1970s programme, organized by Asia Society and Museum in 2013, appears to have been influenced by this tendency, resulting in major exclusion of a key title of the Iranian New Wave with more commercial leanings, i.e. Mas‛ūd Kīmiyā’ī’s Qaysar. This in turn provoked an open letter from Ibrāhīm Gulistān, the director of one of the selected films, Khisht va Āyinah (The Brick and the Mirror, 1964), in which he expressed his objection to this curating choice: see “Nāmah-yi Ībrahīm Gulistān bih Anjuman-i Āsiyā’ī,” Radio Zamaneh, 5 October 2003, accessed 31/05/2025, https://www.radiozamaneh.com/102330/. Some objections originate from this presumption that the term ‘New Wave’ is tantamount to a particular quality and orientation in filmmaking and must be uniformly manifested across various national filmmaking traditions. In this vein Taqī Mukhtār, who as a former critic and editor-in-chief of Māh-i Naw magazine had once participated in the promotion of the Iranian New Wave, retrospectively calls the legitimacy of this naming into question.3Taqī Mukhtār, “Mawj-i Naw-yi Sīnimā-yi Īrān; Nustālzhī-i yak maghlatah-yi tārīkhī – bīsh az hamah mā khushhālīm,” Māh’nāmah-yi Sīnimā’ī-i Fīlm 37, no. 562 (October 2019), 25. His motivation in doing so is the Iranian New Wave’s lack of full alignment with the arthouse cinema. On the other hand film researcher Hasan Husaynī has stressed on several occasions the commonalities between the New Wave films and the rest of Iranian cinema.4Including his recorded lectures in Fīlmfārsī DVD boxset. Husaynī’s view is undergirded by an observation of the great scheme of the Iranian film industry: the development of Iranian cinema can be better explained in terms of various generic or thematic cycles of films, to which many of New Wave films can be assigned. In line with other revisionist views,5For instance, Sabereh Kashi. See: Parviz Jahed, The New Wave Cinema in Iran: A Critical Study (New York: Bloomsbury Academics, 2022), 7. Husaynī questions the legitimacy of this designation, noting that the directors had not premeditated launching a movement.

Husaynī rightly defines the Iranian New Wave as a construct of Iranian film critics and a projection of their desire for identifying and proclaiming a local equivalent of the French New Wave. Both Mukthār and Parviz Jahed – who is still a proponent of the legitimacy of the Iranian New Wave – have indicated the Iranian filmmakers’ lack of a solid background in movie criticism as a remarkable difference between the French New Wave and its Iranian namesake.6Taqī Mukhtār, “Mawj-i Naw-yi Sīnimā-yi Īrān; Nustālzhī-i yak maghlatah-yi tārīkhī – bīsh az hamah mā khushhālīm,” Māh’nāmah-yi Sīnimā’ī-i Fīlm 37, no. 562 (October 2019), 21; Parviz Jahed, The New Wave Cinema in Iran: A Critical Study (New York: Bloomsbury Academics, 2022), 8. In other words, the concept of the Iranian New Wave did not emerge from a well-developed theoretical foundation.

Husaynī describes a persevering attempt by Iranian critics, since the early ’60s, following their initial complete dismissiveness of local cinema, to recognize films with standout qualities that would merit their support and could be touted in analogous terms to the French movement.7Hasan Husaynī, Rāhnamā-yi Fīlm-i Sīnimā-yi Īrān (Tehran: Rawzanah-kār, 2021), 290. Nevertheless, until wide critical and commercial success of Gāv/The Cow (Dāryūsh Mihrjūyī, 1969) and Qaysar (Mas‛ūd Kīmiyā’ī, 1969), the two pictures commonly seen as the instigators of the Iranian New Wave, this desire to identify a local movement kept being frustrated.8Hasan Husaynī, Rāhnamā-yi Fīlm-i Sīnimā-yi Īrān (Tehran: Rawzanah-kār, 2021), 96. Husaynī goes as far as viewing Parvīz Davā’ī’s review of Bīgānah Biyā/Come Stranger (Mas‛ūd Kīmiyā’ī, 1967) – which seems to have guided the filmmaker towards his following hit, Qaysar – as the Iranian New Wave’s manifesto,9Hasan Husaynī, Rāhnamā-yi Fīlm-i Sīnimā-yi Īrān (Tehran: Rawzanah-kār, 2021), 290. ironically not issued by the filmmakers, but a patron movie critic. That is not to completely invalidate a sense of a movement amongst the Iranian New Wave filmmakers or, for that matter, awareness of their position vis-à-vis the mainstream cinema. This self-awareness however appeared after the fact and by formation of Kānūn-i Sīnimāgarān-i Pīshru (The Progressive Filmmakers’ Cooperative) in 1973, at least two years after the term Iranian New Wave seems to have gained currency, reputedly following a note by Jamshid Akrami in Fīlm va Hunar magazine.

Figure 4: Behind the scenes of the film The Morning of the Fourth Day (Subh-i Rūz-i Chahārum), directed by Kāmrān Shīrdil, 1972.

The origins aside, one big challenge in discussing the Iranian New Wave is the wide heterogeneity of the films placed under this rubric. It is in fact one reason that prompts writers like Husaynī to raise doubts over the usefulness of such categorization, compared to examining films through the lens of thematic or generic cycles. In its diversity of style and voices, the Iranian New Wave – probably more than any other national film movement – looks amorphous and difficult to define. The challenge of narrowing down the stylistic features of Iranian New Wave films manifests itself in Hamid Naficy’s chapter on this topic in his four-volume book, where in describing the movement he has to attribute to it a broad range of stylistic choices, which are often polar opposites (for instance, realism and surrealism).10Hamid Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema. Volume 2: The Industrializing Years, 1941–1978 (Durham: Duke University Press, 2011), 340-345.

Additionally, the Iranian New Wave – or simply New Wave- is not the only title applied in cinematic literature to this motely group of films and filmmakers. For example, Jamāl Umīd, a pioneer in writing a tome on history of Iranian cinema, avoids using this term altogether.11Jamāl Umīd, Tārīkh-i Sīnimā-yi Īrān (Tehran: Rawzanah, 1995). His historical chronicle divides Iranian cinema from 1969 until the 1979 revolution into three main groups: the commercial cinema, the intellectual cinema, and what he refers to as “sīnimā-yi jibhah-yi sivvum” (third front cinema).12Jamāl Umīd, Tārīkh-i Sīnimā-yi Īrān (Tehran: Rawzanah, 1995), 522. This last group, the naming of which seems to be coming from ‛Abbās Shabāvīz- the producer of Qaysar, who had proclaimed himself the engineer of the “third front,”13Quoted in Hasan Husaynī, Rāhnamā-yi Fīlm-i Sīnimā-yi Īrān (Tehran: Rawzanah-kār, 2021), 344. — was apparently conceived as a type of cinema that could reconcile popular appeal with technical quality and proficiency, while also offering some intellectual content.14Hasan Husaynī, Rāhnamā-yi Fīlm-i Sīnimā-yi Īrān (Tehran: Rawzanah-kār, 2021), 307 & 344. Indeed, this conceit seemed to be the whole driving force behind the formulation of a New Wave in Iranian cinema. Slightly prior to the release of The Cow and Qaysar and their recognition as inaugurators of the Iranian New Wave, another noteworthy article entitled “Mawj-i naw dar sīnimā-yi Īrān” (The New Wave in Iranian Cinema) published in Fīlm va Hunar magazine. In lieu of a revolutionary approach – after the manner of La Nouvelle Vague – this article prescribed a reforming movement that could “extricate Iranian cinema from repetitive and pedestrian subjects” through making space for “fresh and young voices.”15Quoted in Hasan Husaynī, Rāhnamā-yi Fīlm-i Sīnimā-yi Īrān (Tehran: Rawzanah-kār, 2021), 289.

It seems that the exact relation between what could be described as the Iranian New Wave and arthouse cinema has remained murky and hard to delineate. Despite formulating three categories, Omid’s year-by-year review of Iranian cinema – with the exception of 1972 – groups together films belonging to ‘intellectual cinema’ (sometimes labelled “sīnimā-yi nā-muta‘ārif” or “Unconventional cinema”) and ‘third front cinema’ and never presents a clear example of their differences.16From some point on, he labels this combined group “sīnimā-yi mutavāfit” (‘Different cinema’ or ‘Alternative cinema’). Essentially adhering to a bifurcated model, he simply puts this combined group in opposition to the mainstream commercial cinema that, in his view, continued plunging down into the depths of execrable taste.17Jamāl Umīd, Tārīkh-i Sīnimā-yi Īrān (Tehran: Rawzanah, 1995), 522. On the other hand, Jahed identifies a more commercially viable tendency within The Iranian New Wave owing to “shared commonalities” with the commercial cinema,18Parviz Jahed, The New Wave Cinema in Iran: A Critical Study (New York: Bloomsbury Academics, 2022), 68. thus suggesting that Omid’s combination of two categories- intellectual and third front cinema- virtually refers to the New Wave’ as a whole, without it being explicitly named.19Jahed, however, in keeping with his attempts to stake out the beginning of the movement in earlier, more rarefied films, interprets the existence of this third front as some sort of “infiltration” into the mainstream cinema by the New Wave filmmakers: see Parviz Jahed, The New Wave Cinema in Iran: A Critical Study (New York: Bloomsbury Academics, 2022), 38. Tellingly, almost two years after writing the note that proposed “the Iranian New Wave,” Akrami uses the announcement of the formation of the Progressive Filmmakers Cooperative as an opportunity to express his disenchantment with the previous naming and suggest the alternative title Sīnimā-yi pīshru (Progressive Cinema).20Jamshid Akrami, “Yāftam…Sīnimā-yi Pīshru,” Fīlm va Hunar 442 (19 July 1974): 4. The earlier designation however seemed to have already cemented itself in the vocabulary of film criticism and could not be easily dislodged, no less by a title lacking the same prestigious evocation.

Ironically, while the founders of the French Nouvelle Vague were inveighing against what could be translated as the “Tradition of Quality,” the Iranian New Wave was first and foremost about infusing quality into the national cinema.21Tradition de la qualité, mostly composed of the literary adaptions which dominated the French cinema in the post-World War II and were directly targeted in Francois Truffaut’s polemic piece, “Une Certaine Tendance du Cinéma Français.” See François Truffaut, “A Certain Tendency of the French Cinema,” Cahiers du cinema 31 (1954), https://www.newwavefilm.com/about/a-certain-tendency-of-french-cinema-truffaut.shtml. For all their disparities, though, both movements came to pass as reactions to the mainstream cinema. The Iranian New Wave, as formulated by movie critics who put their weight behind it, was not based on a total break from the mainstream cinema. Rather than alienating the masses, this new cinema aimed to ameliorate mainstream via higher quality pictures.22No wonder that those critics like Hūshang Kāvūsī with their unforgivingly contemptuous view of mainstream Iranian cinema couldn’t approve of this compromise and refused to apply the adapted moniker. Corresponding to this broad desire, the mixed bag of films placed under the banner of the Iranian New Wave exhibits their directors’ pursuit of cinematic reform in a variety of styles, some of which coming across less radical than what would be expected from a supposedly avant-garde movement.

An Iranian À Bout de Souffle

Figure 5: A still from the film The Morning of the Fourth Day (Subh-i Rūz-i Chahārum), directed by Kāmrān Shīrdil, 1972.

Fewer similarities can yet be found between the respective careers of the helmers of À bout de souffle and its Iranian remake. Just as Godard’s film, The Morning… happened to be the debut feature of its Italian educated director, Kāmrān Shīrdil. Nonetheless, it also remains the sole feature-length fiction film in a filmography, which in contrast to Godard’s feature-heavy career mostly consists of documentaries of various lengths. In retrospect, The Morning… stands out like something of an oddity in its filmmaker’s career.

A more significant difference between the two films concerns their position in the respective movements they are associated with. While Godard kickstarted the French New Wave by making À bout de souffle, Shīrdil simply seems to have jumped on a bandwagon which had already departed, even though his own actual filmmaking career predated the production and release of The Cow and Qaysar.23In point of fact, Shīrdil started his filmmaking career with documentaries, despite allegedly having not been trained particularly for that in the film school. See: ‛Alīrizā Arvāhī, ed. Kāmrān Shīrdil; Tanhā dar Qāb (Tehran: Khūb, 2021), 36. One might speculate that the director had taken advantage of the title tagged on the films of the young directors of his generation and used this remake as an opportunity to strengthen their association with French New Wave. Shīrdil identifies À bout de souffle as one of three impressionable films that led him to study cinema.24‛Alīrizā Arvāhī, ed. Kāmrān Shīrdil; Tanhā dar Qāb (Tehran: Khūb, 2021), 29. This personal attachment could have been a sufficient motivation for Shīrdil to conceive a remake, rather than an original concept, as an “ideal project” for his debut feature.25Ārash Sanjābī, Hastī-i Āyinah: Guftugū bā Muhammad Rizā Aslānī (Tehran: Nashr-i Akhtarān, 2018), 129-130. Regardless of his true motivation, by reimagining his adored film in the context of a flourishing film movement, Shīrdil, and his collaborators, allowed distinguishing elements of the Iranian New Wave filter through the film and leave their marks on it.

Figure 6: Behind the scenes of the film The Morning of the Fourth Day (Subh-i Rūz-i Chahārum), directed by Kāmrān Shīrdil, 1972.

Being an adaptation, The Morning… points at a major difference between the French New Wave and its Iranian counterpart. Unlike the French filmmakers who basically rebelled against the tradition of literary adaptation in French cinema, the Iranian New Wave did not shape in opposition to the literature; on the contrary, literary adaptation emerged as one prominent trends among Iranian New Wave films.26Parviz Jahed, The New Wave Cinema in Iran: A Critical Study (New York: Bloomsbury Academics, 2022), 122. In this regard, The Morning… occupies a position in between; it is an adaptation and yet not relying on the written material (even though its scriptwriter, Muhammad Rizā Aslānī wrote the script based on Shīrdil’s own translation of Godard’s script). Indeed, some Nouvelle Vague filmmakers were consummate cinephiles and as such did not shy away from showing nods to films that inspired them, especially American films. Shīrdil’s feature can be received in the same spirit. It’s also worth mentioning that while The Cow was based on a short story by an Iranian writer, the narrative of Qaysar was allegedly patterned after Nevada Smith (Henry Hathaway, 1966). Hence Shīrdil’s cinematic referencing was not without precedent in the Iranian New Wave. Interestingly though and despite Shīrdil being open about doing a remake, the opening credits of The Morning… make no mention of the original source.

Parallels and Divergences

Even without an open acknowledgement The Morning… comes across as a more or less loyal adaptation of Godard’s film in its overall narrative. As in À Bout de Souffle, a petty thief, named Amīr and played by Sa‛īd Rād, steals a car and unintentionally commits a crime on route to the capital city. He desperately tries to contact his trusted friend to borrow some money and make his escape. In the meantime, he gets together with his girlfriend Zarī, apprises her of what happened, and takes her along in his hide-and-seek game, while the police are on his tail. Eventually on the morning of the fourth day of his fugitive life, his girlfriend snitches on him, leading to his death.

Figure 7: A still from the film The Morning of the Fourth Day (Subh-i Rūz-i Chahārum), directed by Kāmrān Shīrdil, 1972.

The parallel between the two films goes beyond the similarity of the overall plot and main characters and at times entails replication of minor events, even if in a different point in the narrative. The two thefts committed by Amīr – the wallet and the car key – constitute such narrative parallels with Godard’s film. Another comparable scene is Amīr’s attempt to sell a car, which culminates in a physical brawl—much like the scene with Godard’s protagonist, Michel (Jean-Paul Belmondo). The difference is that in The Morning… Amīr takes the car to a car junkyard, which allows the director to picture him amidst scrapped cars. This creates an image that also metaphorically – and in tune with the bitter tone of the film- emphasizes Amīr’s position as an outcast.

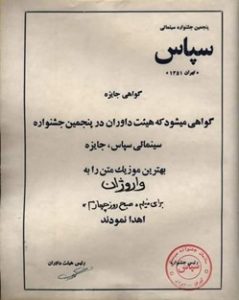

All the same, The Morning… asserts its difference from its very outset. Narratively speaking, The Morning… begins with a similar sequence of events: stealing a car, a road trip, and an accidental murder. Yet instead of casualness and the reserved, distanced and often ironic tone of the French film, it opts for a completely dramatized approach. Shīrdil chooses to treat everything in a suspenseful manner and maintains this feel from stealing the car all the way to the murder scene. Vārūzhān’s score for the film pulls in the same direction and deepens this mood and emotional engagement; it has little in common with the light-heartedness of jazzy music in Godard’s film.27Despite boasting an original score like most other Iranian New Wave films- as opposed to the tradition of scoring films with stock music, which was still a common practice in Iranian mainstream cinema of the time – The Morning… at least at one scene uses a pre-existing score – belonging to I giorni dell’ira (1967) – which feels like a holdover from the commercial cinema traditions.

Figure 8: Portrait of Vārūzhān, film composer.

Figure 9 (right): Certificate of Appreciation for Best Original Score awarded to Vārūzhān for The Morning of the Fourth Day (Subh-i Rūz-i Chahārum), directed by Kāmrān Shīrdil, 1972.

Figure 10 (left): Sipās Film Festival award.

Considering the strict censorship of the period, it comes as no surprise that the victim in Shīrdil’s remake was changed from a police officer to a tough guy, who indeed provokes the violent act by not letting Amīr pass his car. However, this character switch seems to have created a pretext for the filmmakers to enlarge this violent episode into a full-blown physical brawl. In comparison, there is no real build-up to violence in the French film; it happens instantly and on the spur of the moment. What’s more, even the actual moment of violence- shooting the police- is elided: there’s only a close-up of the gun in Michel’s hands followed by a shot of already fallen and dead police officer. Shīrdil on the other hand goes as far as revisiting the murder scene during the fight at the junkyard; by throwing in quick shots from the earlier scene he both intensifies the tempo and creates a visual parallel in physicality. Stylistically speaking, The Morning… demonstrates in its opening part even more signs of proximity with the commercial cinema: the quick and crushing zooms, often maligned by Iranian critics as some blatant contrivance, are deployed here together with high and low angle shots and flashing shots of the sunlight to intensify the excitement. The sunlight shots are also meant to pictorially convey the unbearable sun heat which the anti-hero blames for pushing him over the edge and into committing a violent act with a murderous outcome.

Figure 11: A still from the film The Morning of the Fourth Day (Subh-i Rūz-i Chahārum), directed by Kāmrān Shīrdil, 1972.

The emphasis on heat as the trigger for an impetuous and accidental crime is peculiar to the Iranian version. It corresponds to the scorching climes from which Amīr sets off on his trip. However, it also signals influences from Albert Camus’ L’Étranger, an influential French literary work in which another pointless crime is committed under the influence of the maddening heat. Widely discussed in connection with existentialist philosophy L’Étranger was also well-known amongst Iranian intelligentsia. Speaking of The Morning… retrospectively, Aslānī makes multiple hints at existentialism as the philosophical undercurrent of the film, without explicitly naming Camus’ book.28Ārash Sanjābī, Hastī-i Āyinah: Guftugū bā Muhammad Rizā Aslānī (Tehran: Nashr-i Akhtarān, 2018), 130, 135. Shīrdil himself recognizes a possible influence from L’Étranger on Godard and his film. It seems that his awareness brought this connection even more visible in his own version.29‛Alīrizā Arvāhī, ed. Kāmrān Shīrdil; Tanhā dar Qāb (Tehran: Khūb, 2021), 64.

The less tension-laden car trip to Paris in À bout de souffle is accompanied by Michel’s monologues whereby he expresses his thoughts; it even entails breaking the fourth wall and talking to the camera. Godard later almost abandons this device, especially after Michel arrives in Paris and is pictured in company of other characters. In The Morning… Shīrdil’s means to express Amīr’s thoughts on the road -and prior to confrontation- are purely visual: brief shots of erotic nature pop up during the driving scene, before the vexatious driver spoils Amīr’s daydreaming. In so doing, the film presents Amīr as a less sophisticated version of Michel and lays stress on the carnal aspect of his character, which also accords with physicality of the ensuing fight.

Male/female dynamics

Placing the two films side by side show an evident unbalance between the male and the female characters in the Iranian film. Granted, Michel is still the principal character in À bout de souffle whose actions shape the main thrust of the narrative, but before long he meets Patricia, the American girl (played by Jean Seberg) who becomes equally instrumental to the plot. For one thing, the encounter of Amīr and his girlfriend Zarī in Shīrdil’s film is deferred on the excuse of her avoiding Amīr. This in turn brings the frustrated Amīr to join his friends and spend more time in their company, resulting in expansion of the screen time assigned to him, at the cost of Zarī ’s role in the narrative. Such scenes also bolster the homosocial undercurrent of the film which is non-existent or at most remain understated in Godard’s film (Michel, too, depends on his male friends and seeks help from them, but he is never shown participating in an all-male group revelry). Aslānī’s script for The Morning… was supposed to give even further prominence to Amīr by expanding the road trip, which was to contain more encounters and adventures and could have produced more originality, but those extra scenes are eventually put aside by Shīrdil.30Ārash Sanjābī, Hastī-i Āyinah: Guftugū bā Muhammad Rizā Aslānī (Tehran: Nashr-i Akhtarān, 2018), 130. It is though clear that the makers of The Morning… conceived their film from the outset with Amīr as the fulcrum of the narrative, hence pumping up the masculine energy of the film.

As with Michel, there is more than one woman in Amīr’s life. The scene with the first of them that Michel calls on and steals money from is repeated in The Morning…: a young woman nicknamed Parvā whose coquettishness is amplified in part thanks to the casting choice (the actress, Shahrzād, often appeared as cabaret dancers or similar characters with unmistakeable salaciousness). Both these characters have connections to the world of cinema; the French girl used to be acting for films, but due to inappropriate behaviour on the set has switched to becoming a script girl. Parvā on the other hand is an inspiring actress, who is preparing for an audition. Her conversation with Amīr conveys a similar caddish and exploitive attitude governing the local film industry, but apparently it is also formulated in a way to obliquely poke fun at one of Shīrdil’s colleagues in particular.31The US-educated director that Parvā is going to audition for seems to be an implicit reference to Dāryūsh Mihrjūyī who is rumoured to have advised the producer against an earlier feature project pitched by Shīrdil. See Hasan Husaynī, Rāhnamā-yi Fīlm-i Sīnimā-yi Īrān (Tehran: Rawzanah-kār, 2021), 503. In the writer’s correspondence with Taqī Mukhtār, he who had been offered the lead role in this project confirmed the story behind its cancellation and revealed the name of the producer (Hūshang Tabībiyān).

Figure 12: Parvā in a still from The Morning of the Fourth Day (Subh-i Rūz-i Chahārum), directed by Kāmrān Shīrdil, 1972.

The main female character of The Morning… is nevertheless Zarī (played by Vajistā). Comparing her cinematic image with Patricia can be even more instructive as to a transformative context which impacted the Iranian New Wave cinema. Unlike Patricia in À bout de souffle who is an American expat living in Paris, Zarī is neither a foreigner, nor does she seem to be an outsider. That said, she is still given a foreign and western air by being played by a blonde actress who had even gained a reputation for her western physical attributes.32Hasan Husaynī, Rāhnamā-yi Fīlm-i Sīnimā-yi Īrān (Tehran: Rawzanah-kār, 2021), 532. The exact function of this similitude of foreignness remains a matter of conjecture. Could it be that the director simply tapped into the Iranian cinema’s convention of using a blonde woman as an embodiment of treachery? Curiously though in her workplace, Zarī is shown wearing a black wig. According to the director this was supposed to signal her capricious character and tendency to look different and “change colours”, so to speak, as some means of survival;33From the author’s correspondence with Kāmrān Shīrdil. it could also be seen as presaging her unreliability and eventual betrayal.

Figure 13: Zarī and Amīr in a still from The Morning of the Fourth Day (Subh-i Rūz-i Chahārum), directed by Kāmrān Shīrdil, 1972.

All in all, Zarī is given less prominence in the plot relative to Patricia. What’s more, she is depicted less independent and less intellectual than the American girl. The way the audience first encounters them is telling in this respect: while Patricia is introduced as hawking newspapers on the streets, Zarī is first shown just having arrived home. True enough, she had a job which halfway through the film she returns to and seems to fend for her aunt as well, but this still doesn’t put her on the same level of independence akin to that of assertive American Patricia. This difference can also have something to do with Patricia’s area of activity, which is directly linked to the media and the news.34This is also harmonious with the omnipresence of media in Godard’s film which in various shapes – newspaper, electric signs – remind the viewer of an ongoing hunt for Michel, something absent from The Morning…. In addition to selling the newspaper, Patricia is dabbling as an aspiring journalist.35The scenes of her rendezvous with the editor-in-chief and her attendance of an interview both expand her screen presence – comparable to what Shīrdil does by assigning extra time to Amīr and his friends – and shore up her seminal position in the narrative, while drawing a complex and multi-dimensional picture of her. Together with other hints dropped here and there – like a Faulkner book in her room, which she is supposedly reading – this confers on her character an intellectual edge that Zarī seems to be devoid of. Accordingly, Patricia’s relationship with Michel is treated with more complexity; she is not simply dragged into her boyfriend’s misadventure (which appears to be the case with Zarī). The spectator indeed gets the feeling that she is gradually getting some kick out of this new adventure herself. She gives the police the slip to join Michel and even later in the film is shown driving Michel in a stolen car. This happens despite the fact that, unlike Zarī, Particia is a foreign citizen and therefore holds a parlous situation in her host country. All this make deciphering her true emotions not an easy task. Throughout À Bout de Souffle Patricia remains almost an ambiguous character, very much like the last image of the film which – notably- shows her reaction to Michel’s lifeless body. That Godard chooses to end his film with Patricia’s image says much about her narrative weight.

The Morning … on the other hand leaves Zarī behind after she confesses to informing on Amīr, which leads to the man leaving off. Unlike Godard’s film which intercuts between shots of Michel and Patricia running on the street, Zarī is absent from the last moments of The Morning…. Instead, Shīrdil chooses to finish his film with an image of Amīr. True enough, the disparity between the two female characters to some extent correlates to the social realities of time and the position of women in the respective countries. All the same, it seems that The Morning… in pushing the female lead away from the spotlight reiterates its connection to the existing traditions of the local cinema. Additionally, it connects to a general tendency in the Iranian New Wave cinema, which with few exceptions such as Bahrām Bayzā’ī’s films, was dominated by male characters and proved less amenable to presenting women’s subjectivity. It can even be claimed that despite being a progressive movement aesthetic-wise, a discernible streak of misogyny in varying degrees was running through films affiliated with the Iranian New Wave.

Despite assigning women to play the second fiddle in the narrative, so to speak, The Morning … surprisingly presents a more diversity of female roles in form of Amīr and Zarī’s close relatives. Once again, this can be justified as a consequence of a social context in which the traditional family life and family values still profoundly coloured the individuals’ life, even if, as the films were insinuating, families were on the brink of a crisis. In a clear deviation from the French model, the first place Amīr visits is his family home, where he is received with open arms by his mother (played by Mihrī Vadādiyān) who goes as far in pampering him like a spoiled child as giving him a wash and scrub. The scene’s function as local flavour aside, the mother and son relationship was amongst well-known stock-in-trades of the predominantly melodrama-oriented commercial Iranian cinema, milked to the full in money-spinners such as Ganj-i Qārūn/Qarun’s Treasure (Siyāmak Yāsamī, 1965). Once the connections between the Iranian New Wave and commercial cinema – collectively, albeit pejoratively, termed fīlmfārsī – are acknowledged, it will come to no surprise to identify commonalities in dramatic elements.

The neorealist inclinations

As far as the style is concerned, The Morning… takes a far less radical approach compared to the revolutionary aesthetics of Godard’s. This directly corresponds to different aspiration of the Iranian New Wave, or in other words the different mission sought by the patron critics for their championed cinema: polished filmmaking combined with accessibility and public appeal. The latter aspect inevitably limited the scope for taking a more radical approach, something that Shīrdil had proved himself capable of in his highly acclaimed Ūn shab kih bārūn ūmad (The Night it rained, 1967) which balanced an enquiry into the truth with subversive humour. Emblematic of this more conservative use of cinematic tools in The Morning… is the scene of the couples’ conversation in the car. For Godard, it is one occasion amongst several others in À bout de souffle to apply his- then- revolutionary jump cuts to condense the conversation.36It must be stressed that even though Godard has habitually been credited as a pioneer of using jump-cuts, there are precedents of this aesthetic technique; one such example is Seijun Suzuki’s Rajo to Kenjû, see Peter A. Yacavone, Negative, Nonsensical and Non-conformist: The Films of Seijun Suzuki (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2023), 47. In the comparable scene in The Morning… Shīrdil also elects to trim down the scene; yet his chosen device for connecting the snippets is the more traditional transition of a wipe. Sure enough, by the time Shīrdil made his feature the novelty of jump cut had been worn off; yet in comparison with a film that preceded it by over a decade, the aesthetic choices in The Morning … hardly strike as innovative.

Another marker of Shīrdil’s more traditional approach and commercial considerations can be sought in the film’s erotic content.37The commercial concerns of the film make additional sense in the light of the fact that the film was self-financed by Shīrdil. See: ‛Alīrizā Arvāhī, ed. Kāmrān Shīrdil; Tanhā dar Qāb (Tehran: Khūb, 2021), 63. Even though in Godard’s film an entire rather lengthy scene is devoted to Michel and Patricia in the girl’s apartment, the film doesn’t go much far in terms of visualizing their intimacy. On the other hand, the physical attraction of the couple in Shīrdil’s film is treated conventionally in a rather elaborate lovemaking scene. At the time The Morning … was made, Iranian cinema was opening itself to more explicit imagery and the New Wave directors were amongst the first to embrace it due to its habitual association with European arthouse cinema and as a marker of prestige (though the mainstream cinema was quick to follow suit and bank on more risqué content).

The less stylized approach in The Morning… – probably barring the first part – in favour of a more gritty, matter-of-fact presentation can be imputed to the Iranian New Wave’s influence by Italian neorealism. The neorealist impulse has been described as one of the two “general trends within” the Iranian New Wave.38Parviz Jahed, The New Wave Cinema in Iran: A Critical Study (New York: Bloomsbury Academics, 2022), 185. This influence was itself part of the constant push for realism as a benchmark and a dominant element of critical discourse amongst the cultural elite. This was partly due to the purchase of leftist ideologies on Iranian intelligentsia and partly in reaction to the denigrated escapism of fīlmfārsīs. The neorealist inclinations can be as well studied as a part of the larger picture of the impact of Italian cinema, owing to the popularity of the Italian films with Iranian cinemagoers and its big share of imported films in Iran.39Hasan Husaynī, Rāhnamā-yi Fīlm-i Sīnimā-yi Īrān (Tehran: Rawzanah-kār, 2021), 331. It might be safe to claim that despite its name, the Iranian New Wave was formally in proximity of neorealism (which was also a source of influence for La Nouvelle vague and somehow viewed as its precursor). Evidently in pursuing the neorealist impulses, the Iranian New Wave directors could not go all the way and risk a confrontation with a system which was not much tolerant of an unvarnished image of realities.40Hamid Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema. Volume 2: The Industrializing Years, 1941–1978 (Durham: Duke University Press, 2011), 351.

Figure 14: Zarī and Amīr in an erotic sequence from the film The Morning of the Fourth Day (Subh-i Rūz-i Chahārum), directed by Kāmrān Shīrdil, 1972.

What makes The Morning… even a more interesting case in terms of the movement’s link with neorealism is Shīrdil’s own background. Not only was he familiar with Italian neorealism and wrote criticism about it even before studying cinema formally,41‛Alīrizā Arvāhī, ed. Kāmrān Shīrdil; Tanhā dar Qāb (Tehran: Khūb, 2021), 20. he even received his education in Italy and studied directing under the tutelage of Nanni Loy, who had directed one of the later landmarks of neorealism, Le Quattro Giornate di Napoli (1962).42‛Alīrizā Arvāhī, ed. Kāmrān Shīrdil; Tanhā dar Qāb (Tehran: Khūb, 2021), 30. Putting this next to Shīrdil’s earlier career of making documentaries, including socially-conscious titles, can explain how Shīrdil’s reimagination of a French New Wave film was imbued by the older Italian film school.43Shīrdil also mentions that one of his earlier ideas for a feature film was an adaptation of James M. Cain’s story, The Postman always rings twice, which was already adapted by Luchino Visconti into Ossessione (1943), generally seen as one of beginning points of Italian neorealism, see ‛Alīrizā Arvāhī, ed. Kāmrān Shīrdil; Tanhā dar Qāb (Tehran: Khūb, 2021), 64. Also interesting in terms of the French-Italian connections of The Morning… is Aslānī’s speculation that the script of À bout de souffle which he received was translated by Shīrdil from Italian, see Ārash Sanjābī, Hastī-i Āyinah: Guftugū bā Muhammad Rizā Aslānī (Tehran: Nashr-i Akhtarān, 2018), 130.

Connection with ‘Street Films’ and ‘tough guy’ traditions

The Morning… can be categorized as belonging to a group of Iranian films from the 70s often described by Iranian film critics as Fīlm-hā-yi Khiyābānī (Street Films). Bleak in tone and featuring down-and-out heroes who are eventually vanquished by their sordid (urban) environment, these films demonstrated an affinity with neorealist tendencies.44“Street film” is an even less-theorized and more ambiguous term than ‘the Iranian New Wave’ and its definition is somehow left open to critics’ interpretation. ‛Abbās Bahārlū, the film historian, for example declares Gorji (George) Obadiah’s child-centred melodrama Bīm va Umīd (Fear and Hope, 1960) as the first genuine street film, since traversing the streets of Tehran by the film’s little heroine is central to its plot and makes up a considerable part of it. All the same, he acknowledges that the rather sanguine picture of urban life presented in Obadiah’s film is poles apart from the bleakness habitually associated with and characterising most Iranian film to which this term has been applied, see ‛Abbās Bahārlū, “Khiyābān’hā-yi bī-rahm,” Sāl’nāmah-yi Fīlm 27 (March 2018), 61-62.

More commonly the origins of streets films have more been traced to the Iranian New Wave film, Rizā Muturī/Reza, the Motorcyclist (Mas‛ūd Kīmiyā’ī,1970). See: Tahmāsb Sulhjū, “Dūrbīn-i Vilgard: Khiyābān-i Sarnivisht,” Sāl’nāmah-yi Fīlm 27 (March 2018), 84. “Street Films” – some of which are classified as belonging to the Iranian New Waves – also present a continuity with fīlmfārsīs, from which they borrowed certain elements and redeployed them in a more realistic set-up or premise. The genealogy of the bitter anti-heroes of “Street Films” can indeed be traced back to the ‘tough guy’ of the fīlmfārsīs.45The film researcher Sa‛īd Nūrī suggests a genealogical connection between the aimless wandering of protagonists of these films and the scenes in the Iranian films from the 1950s devoted to show the city life and the attractions of the capital city; moments which particularly in earlier films might not feel dramatically or narratively motivated. See: Sa‛īd Nūrī, “Bād nām-i farāmūsh-shudagān rā mīkhānd,” Māh’nāmah-yi Fīlm-i Imrūz 37, no. 50 (May 2025), 99. Having been cast in a negative light, they correspond to the ‘lout’ side of the Janus-faced image of cinematic “tough guy,” as defined by Naficy.46Hamid Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema. Volume 2: The Industrializing Years, 1941–1978 (Durham: Duke University Press, 2011), 277. The migration of these characters from fīlmfārsī to the New Wave films can be also explained by the representational restrictions – not only imposed by the government, but even sought by trade unions – both groups of films were faced with. To both camps of filmmakers, selecting characters from people on the fringe of the society could run the least risk of raising objections to their cinematic portrayal. In case of the New Wave filmmakers, focusing on the so-called refuse of the society and their milieu could also potentially lace the films with the flavour of social consciousness.47Shīrdil allegedly intended to tone done the nihilism colouring À Bout de Souffle in favour of more sociological depth, see ‛Alīrizā Arvāhī, ed. Kāmrān Shīrdil; Tanhā dar Qāb (Tehran: Khūb, 2021), 64. The total downbeat air enveloping characters of “Street Films,” who often sounded already submitted to their inextricably tragic destiny, distinguished them from the earlier generation of cinematic tramps with their devil-may-care attitude and was perceived as a reaction to escapism of fīlmfārsī.48Tahmāsb Sulhjū, “Dūrbīn-i Vilgard: Khiyābān-i Sarnivisht,” Sāl’nāmah-yi Fīlm 27 (March 2018), 84.

Amīr is better adapted to the image of stereotypical lout, compared to his French model: unlike Michel who used to be a steward with a supposedly adventurous past – he claims having worked in Cinecittà – Amīr’s earlier life is mostly kept in the dark. The way he is received by his mother gives the idea of him being raised as a pampered child and grown into a carefree and irresponsible young man. As a plain thief, Amīr is nothing but an anti-social and unproductive character whose only contribution to his family is his troubles. Both Michel and Amīr verbalize their resignation to stop evading their fate – the former does so by addressing the camera, as befitting the avant-garde spirit of the film – and refusing to use the gun to defend themselves; yet the bitterness of Amīr’s fate feels even more profound, since he is somehow bereft of Michel’s mischievous charm. It could also be due to the overall more sombre mood of Shīrdil’s film, which is consonant with the street film traditions.

The more explicit violence of The Morning… can accordingly be attributed to its links and affinities with “tough guy” films and their conventions, which as well spread into “Street Films.” The lengthy fight in the beginning of the film can be sensed as the first occasion where Shīrdil’s film seems to have been falling back on the traditions of “tough guy” films in Iranian cinema with fisticuffs and physical brawls being amongst their staples. Choosing an actor often typecast as the bad tough guy – Jalāl Pīshvā’iyān – to play the victim’s role strengthens this link.

The ending of The Morning… best crystallizes its association with the “Street Films.” It removes the woman from the final chase and dilutes her agency in the manner of tough guy films.49Hamid Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema. Volume 2: The Industrializing Years, 1941–1978 (Durham: Duke University Press, 2011), 290. The Morning … ends on the freeze-frame of Amīr who, after being hit by a bullet, takes a leap into the air with raised hands. The jump and the bullet impact are in fact shown repeatedly and from multiple angles before turning into a still image. In its iconography, this frozen picture is consistent with a notion of protest or resistance which the Iranian New Wave films, even regardless of its relevance to their diegetic world, tended to conjure up.50Shīrdil uses the freeze frame technique in an earlier scene, but to a totally different effect: The image freezes when Amīr, impudently refusing to respect Parvā’s call for privacy, shows an excited reaction to her undressing and creates one of the rare comic moments of the film. It must be added that, unlike some other “Street Films,” The Morning … does not feature a non-diegetic song with politically-interpretable lyrics.51This is a convention probably set, or popularized, by Reza, the Motorcyclist and can be viewed as a highbrow alternative to diegetic song (and dance) numbers, common to fīlmfārsīs. In this respect, Shīrdil’s film represents a deviation from the norm, which probably speaks to the filmmaker’s more artistic ambitions.

Figure 15: The film ends on a freeze-frame of Amīr, who, after being hit by a bullet, leaps into the air with raised hands. A still from the film The Morning of the Fourth Day (Subh-i Rūz-i Chahārum), directed by Kāmrān Shīrdil, 1972.

Political undertones

Leaning towards a neorealist style – including adopting the street film format – seemingly was one tactic for the Iranian New Wave filmmakers to make- or pretend to make- a political point. Though some French New Wave filmmakers – Godard being the most notable of them – demonstrated a consistently keen interest in politics, the political stance seems to have gained more significance in identification of the Iranian New Wave. It seemed to be essential for films to strike a note of dissent in one form or another in order to qualify “the new wave” stamp, to the degree that it has been perceived as one main unifying feature of the movement.52Parviz Jahed, The New Wave Cinema in Iran: A Critical Study (New York: Bloomsbury Academics, 2022), 117. In Shīrdil’s case, the anecdotal notes from his professional life point to his leftist tendencies and unflagging non-conformity, which resulted in being laid-off by the ministry of art and culture, to say nothing of his clashes with the censorship system over documentaries with controversial subject matters.53‛Alīrizā Arvāhī, ed. Kāmrān Shīrdil; Tanhā dar Qāb (Tehran: Khūb, 2021), 54.

This deep commitment to politics however doesn’t shine through in The Morning…, despite the potentials of a “Street Film” format. It can come from the fact the film does not suggest much on Amīr’s background, hence picturing him more like a stereotypical lout. Nonetheless there are occasions in the film, where Shīrdil’s preoccupations and his background come closer to the surface. One such scene – which is peculiar to Shīrdil’s remake – is when Amīr and his friends, throw a prostitute out of their car, ostensibly after having their way with her, leaving her on the street fuming and cursing. Digressive in nature, this brief scene can be seen as harking back to Shīrdil’s documentary project about the pleasure district of Tehran and its women, titled Qal‘ah, which due to confiscation of its footage got released only after the 1979 Revolution. Similar claim can be made for Zarī’s aunt, another original character of The Morning…, who is pictured as helplessly flirtatious and struggling with serious drinking habits. Though the film is not explicit about it, she gives off an air of a fallen woman. Seeing her drinking and breaking into tears while surrounded by photos from her past, the audience is invited to commiserate with her perhaps in the same way as with real-life female characters of Shīrdil’s earlier documentaries. Such added details could as well make up for film’s relative less sensitivity towards its female lead.

An unofficial trilogy: alliances within the New Wave

As a debut feature of a filmmaker who was, then, fascinated with American cinema, À bout de souffle is marked all over with undisguised cinephilia, demonstrating itself amongst other things in Michel’s visits to movie theatres. In The Morning… there is only one movie theatre scene, but rather than making a nod to his sources of inspiration – à la Godard – Shīrdil takes this as an opportunity to somehow valorize his peer New Wave filmmakers by showing a poster – belonging to ‛Alī Hātamī’s Qalandar (1972) – as well as an excerpt of their films.

The film shown at the movie theatre, Amīr Nādirī’s Khudāhāfiz rafīq (Goodbye Friend, 1971) gains additional relevance to discussions of The Morning…. Retrospectively, some textual and intertextual connections between the two films, as well as with Nādirī’s next feature film Tangnā (Straits, 1973),54Also translated as Impasse. can be observed. Released one year apart from each other, the three films constitute something akin to an unofficial trilogy of “Street Films,”55Bahārlū is of the opinion that Goodbye friend should be seen as the vanguard of “low budget street films,” a phrase Nādirī himself used in an interview vis-à-vis his film. See: ‛Abbās Bahārlū, “Khiyābān’hā-yi bī-rahm,” Sāl’nāmah-yi Fīlm 27 (March 2018), 62. and provide an example of collaborative endeavours in the Iranian New Wave cinema which have often been considered uncommon compared to La Nouvelle Vague.56For instance, see: Parviz Jahed, The New Wave Cinema in Iran: A Critical Study (New York: Bloomsbury Academics, 2022), 12. All three film to varying degrees deviate from a traditional dramatic structure in favour of charting their hopeless character’s ill-fated schemes and futile wanderings, treated in a matter-of-fact manner. Even more, the films share amongst them some of their creative team members.

Shīrdil and Nādirī came to know each other during the time the former was making commercials and before either of them ventured into making their debut features.57‛Alīrizā Arvāhī, ed. Kāmrān Shīrdil; Tanhā dar Qāb (Tehran: Khūb, 2021), 61. The connections between The Morning … and Goodbye Friend were noted by critics during the screening of Shīrdil’s film and is most obvious in casting choices.58Hasan Husaynī, Rāhnamā-yi Fīlm-i Sīnimā-yi Īrān (Tehran: Rawzanah-kār, 2021), 504. Sa‛īd Rād, Vajistā and Mihrī Vadādiyān play similar roles in Goodbye friend, with the character impersonated by Vajistā likewise informing the police on her boyfriend, while Jalāl Pīshvā’iyān is cast as another bad guy who would make the things sour for everyone and get slain. Unlike the narratives of The Morning… and Straits which are formed around a solo anti-hero, Goodbye Friend portrays a disintegrating male friendship using a trio of tough guys. The film’s focus on male friendship leaves even less room for female characters compared to the two later titles. Aside from the movie theatre scene, Shīrdil directly cites Goodbye Friend on another occasion in his own feature, where Amīr whistles the main theme song of Nādirī’s film.

The Morning…’s parallels with Straits are broader. In both films Sa‛īd Rād plays a character who goes on the lam after an accidental murder and desperately seeks money to escape to safety (though his situation in Nādirī’s sophomore – as suggested by the title – is even more dire, since he is also rabidly chased by his victim’s vengeful relatives). Just as Amīr, ‛Alī Khushdast in Straits goes back home after committing murder, but the distress he stirs up is immediate and more serious; he basically uproots his family. ‛Alī Khushdast’s affections are also divided between two women, the more sensual type of whom is again placed by Shahrzād. This time around, she is pictured in a more sympathetic way, yet her sincere attempt to help out Ali backfires and instead leads him into a mortal trap. The other young woman, to whom Ali shows more romantic attachment similarly shows more devotion than Zarī in The Morning…; she joins Ali on the street on pain of being fired and disowned by her family. Overall, Straits is far gloomier and more hopeless in tone in than The Morning … in every respect. In fact, Shīrdil’s film even feels like a dress rehearsal for its bitterness.59Tangnā was initially used as the working title for The Morning… see Hasan Husaynī, Rāhnamā-yi Fīlm-i Sīnimā-yi Īrān (Tehran: Rawzanah-kār, 2021), 503.

Both The Morning… and Strait were lensed by Jamshīd Alvandī, a cinematographer who built a reputation for using handheld camera and its attendant sense of immediacy. A more significant shared creative element between the two film that can explain their deeper connection should be sought in the figure of their scriptwriter, Aslānī. As a fellow filmmaker whose filmography, fiction and documentaries alike, shows a strong penchant towards arthouse cinema and a spirit for experimentation with cinematic form, Aslānī might sound like an unexpected contributor to these projects which had some commercial bent. Indeed, he even sounded to have been opposed to the down-and-out tough guy characters of Iranian cinema, including those pictured in the Iranian New Wave films.60See: Ārash Sanjābī, Hastī-i Āyinah: Guftugū bā Muhammad Rizā Aslānī (Tehran: Nashr-i Akhtarān, 2018), 135. However he claims to have been motivated for these collaborations, despite his fundamentally different taste, by sharing with Shīrdil and Nādirī the goal of reforming the mainstream cinema;61Ārash Sanjābī, Hastī-i Āyinah: Guftugū bā Muhammad Rizā Aslānī (Tehran: Nashr-i Akhtarān, 2018), 133. in other words the same agenda envisioned for the Iranian New Wave by its patron critics. The participation of an artist with a strong faith in an esoteric style of cinema in production of a film whose characters shows commonalities with the mainstream cinema of the time encapsulates in a single film the very hybrid essence of the phenomenon called the Iranian New Wave.62The Morning… is not the only film featuring a collaboration between Shīrdil and Aslānī. Later, when Shīrdil’s adaptation of Gogol’s The Government Inspector for Kānūn, titled Dūrbīn/Camera – which was supposed to be his next feature-length film – was aborted after shooting roughly 25-minute’s worth of footage, Shīrdil handed over the script – cowritten with Ismā‛īl Nūrī‛alā – to Aslānī, which he made it into Chunīn Kunand Hikāyat/Therefore Hangs a Tale (1973), see ‛Alīrizā Arvāhī, ed. Kāmrān Shīrdil; Tanhā dar Qāb (Tehran: Khūb, 2021), 74-75; Shīrdil believes that no part of the footage for this unfinished project was used in Aslānī’s version.

Conclusion

The Iranian New Wave, as it was generally understood and defined, was not merely an unadulterated arthouse cinema phenomenon, but rather a hybrid and non-homogenous movement, presenting different formal orientations.63Parviz Jahed, The New Wave Cinema in Iran: A Critical Study (New York: Bloomsbury Academics, 2022), 185. Likewise, a pure ‘arthouse’ status cannot be claimed for Shīrdil’s only feature-length directorial attempt, as I tried to illustrate in my examination of the film throughout this text. Through its link to the existing traditions in local filmmaking and its refrainment from formal audacity, The Morning… exhibits a conscious and unequivocal desire for public reach and accessibility, while its referencing of Godard’s highbrow film hints at a different level of aspirations. It is as if the film is pulled by different ambitions. In his review of The Morning… Jamshid Akrami opines that the film is marred by what he perceives as inconsistency in treatment of its material.64Quoted in: Ahmad Amīnī, Sad Fīlm-i Tārīkh-i Sīnimā-yi Īrān (Tehran: Muʾassisah-yi Farhangī Hunarī-i Shaydā, 1993), 164. The inconsistency can also be defined as a feature of the Iranian New Wave as a whole. In effect The Morning… in its combination of various cultural influences consciously aligns itself with the prescribed agenda for the Iranian New Wave. As such, it virtually encapsulates the entire movement in its diversity and heterogeneity. Patterned after a Nouvelle Vague relic, The Morning of the fourth day at once asserts the inspiration behind the Iranian New Wave and reveal its fundamental difference from similar movements.

Cite this article

This article studies Subh-i Rūz-i Chahārum (Kāmrān Shīrdil, 1972), an Iranian remake of À Bout de Souffle (Jean-Luc Godard, 1960), which is also seen as belonging to the “Iranian New Wave.” Commonly referred to in the literature on the pre-revolutionary Iranian cinema, the ‘Iranian New Wave’ has been subject to review and reinvestigation in recent years. Questions have been raised about its existence as an authentic cinematic movement due to a fixed interpretation of the ‘New Wave’ brand, which presupposes an aesthetic alignment with the French New Wave. By directly referencing the kickstarter of the French New Wave, Shīrdil’s film presents itself also relevant to such re-evaluations. Examining Shīrdil’s film as an exemplar of the Iranian New Wave, this writing compares it with the original model, while also considering its links with other local films and traditions and clarifying the transformative context of the Iranian New Wave. In doing so, it aims to reconfirm the heterogeneity of the Iranian New Wave and its influences as a characteristic of the movement.