A Historical Wound: The Role of Ta‘ziyah as a Theater-Ritual in Iranian Cinema

In the collective memory of Iranian society, the events of Karbala are not merely remembered as a historical tragedy; they emerge again and again as a living, affective force, a wound that speaks, a site where resistance, sacrifice, and mourning converge. At the heart of this emotional landscape lies the ta‘ziyah.

Ta‘ziyah is not merely a theatrical reenactment, but also a ritualized performance that transforms grief into presence, absence into community, and history into immediacy. For centuries, ta‘ziyah has not only been a devotional act but a performative system—a sensory and semiotic field through which culture explores its identity between loss and endurance, rupture and continuity. As a ritual theatre embedded in Shi’i collective memory, it articulates a symbolic language of grief and justice that not only reflects but also responds to social and political tensions. The ethical structure of ta‘ziyah—rooted in witnessing, sacrifice, and resistance—offers a framework through which communities negotiate historical trauma, challenge hegemonic narratives, and shape collective aspirations. It unites body and voice, performer and spectator, memory and politics into a shared space of ritualized becoming —a transitional zone in which participants collectively enact and transform grief, identity, and historical consciousness through embodied repetition and symbolic performance.

This article investigates how the dramatic and symbolic system of taʿziyah has shaped Iranian cinema from the 1960s onwards—a period marked by political rupture, artistic experimentation, and the negotiation of cultural identity under the pressures of modernization and Western influence. In response to state censorship and the suppression of direct political expression, filmmakers turned to indigenous, emotionally charged forms such as taʿziyah. They drew upon it not only as a cultural archive of resistance, but also as a performative and affective matrix—a structure in which memory, ritual, and embodied experience generate cinematic meaning. The stylized gestures, heightened moral intensities, and spatial poetics of taʿziyah constitute what I describe as a “grammar of witnessing”: a mode of aesthetic testimony that resists Western cinematic conventions and reclaims narrative, voice, and subjectivity on locally situated terms.

By engaging with performance theory and ritual studies, this article situates taʿziyah not merely as a historical referent but as an active structure of feeling—a living aesthetic and ethical system that continues to shape Iranian cinematic expression. Through close readings of selected films by directors such as Bahrām Bayzā’ī and ‛Abbās Kiyārustamī, the study demonstrates how the aesthetics and ethics of taʿziyah animate recurring themes of martyrdom, memory, and resistance in Iran’s modern cinematic landscape. In doing so, the essay provides a deeper understanding of how ritualized performance sustains cultural memory—functioning as both a mirror and a mechanism of reflection, resilience, and subversion in Iranian film.

Theoretical Framework: The Evolution of Ta‘ziyah and Its Role in Iranian Cinema

Figure 1: Hur-Ta‘ziyah, Isfahan, 2011.

Taʿziyah, a ritual deeply embedded in Iran’s cultural and religious fabric, has been interpreted through multiple lenses over the centuries. Its trajectory — from a fragmented symbolic practice to a powerful collective narrative resonating across religious and political spheres — parallels the broader evolution of Iranian cinema. To trace the history of Taʿziyah is, in many ways, to trace the evolving cultural, social, and political consciousness of Iran itself.

Historically, Western scholars often described taʿziyah in fragmentary and reductive terms—isolated performances tied to religious festivals, detached from their broader cultural and political contexts. Such readings were shaped not only by orientalist paradigms, but also by the historical conditions of taʿziyah itself, which only began to cohere into an institutionalized form with the consolidation of Shi’ite rule under the Safavīds (1501–1722). During this period, taʿziyah evolved into a dynamic medium of collective expression, as the entanglement of religion and politics intensified and Shi’ism was installed as the state’s ideological foundation. This transformation laid the groundwork for taʿziyah to emerge as a cultural and aesthetic system—ritual, performance, and politics becoming mutually constitutive.1Kathryn Babayan, Mystics, Monarchs, and Messiahs: Cultural Landscapes of Early Modern Iran (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2002), ch. 5–6. She argues that Western scholarship historically described taʿziyah in fragmentary terms and that the ritual cohered into a cohesive institutional form with the Safavīd consolidation of Shi‘ite rule.

The first major Western account of taʿziyah appears in Die heutige Historie und Geographie oder der Gegenwärtige Staat vom Königreich Persien (1737) by Salmons and Van Goch. In this text, the authors describe the “Passion of the Saint and his followers” staged on grand, theatrically adorned chariots—an early observation of symbolic performance in which antagonists are faceless, representing abstract forces rather than individualized figures. Although lacking in ethnographic detail, this account reveals that early Western observers recognized the ritualistic and allegorical dimensions of taʿziyah.

As Parvīz Mamnūn notes, such accounts challenge dominant scholarly assumptions by suggesting that the roots of Persian Passion Plays may predate their formal institutionalization by over half a century. This early recognition affirms taʿziyah not merely as a liturgical custom but as an emergent performative structure—already shaped by symbolic abstraction and public ritualization—long before it became codified under Safavīd state ideology.2Parvīz Mamnūn, Ta‘ziyah dar Īrān [Ta‘ziyah in Iran] (Tehran: Nashr-i Markaz, 1991), 154-166.

Carsten Niebuhr’s Reisebeschreibungen nach Arabien und Anderen umliegenden Ländern (1765–1766) further advanced Western understanding by documenting a taʿziyah performance on Khārk Island in the Persian Gulf. In contrast to earlier symbolic modes, Niebuhr’s account describes a ritual in which formerly allegorical antagonists like Yazīd and Shimr appear as dramatized characters with distinctive traits and recognizable identities. This shift—from abstract embodiment to narrative individuation—marks a significant transformation in the performative structure of taʿziyah.

The transition reflects a broader socio-political dynamic: as public rituals increasingly served to articulate communal identity under Safavīd and post-Safavīd rule, taʿziyah developed into a theater of historical presence. It no longer merely referenced sacred events symbolically; it staged them with psychological and dramatic immediacy, giving political charge and moral depth to its protagonists. In this way, the ritual began to echo contemporary anxieties, social ruptures, and the lived experience of authority and martyrdom.

The development of taʿziyah during the Safavīd and Qājār periods reflects a gradual transformation from modest processions into complex theatrical performances. Under Safavīd rule, particularly during the 17th century, processional mourning rituals began to incorporate performative and spatial elements, eventually evolving into fully staged spectacles. This evolution culminated in the architectural emergence of Takiyahs—dedicated venues designed for ritual drama.

By the mid-19th century, during the reign of Nāsir al-Dīn Shah, Tehran alone hosted between 40 and 45 such structures, with the Takiyah Dawlat serving as a central space for court-sponsored taʿziyah. These spaces were not only physical sites but symbolic centers where religious devotion, political spectacle, and cultural aesthetics converged. As taʿziyah performances grew in scale and complexity, the antagonists (like Yazīd or Shimr) began to receive dramatic attention nearly equal to that of the protagonists—a shift already noted by 18th- and 19th-century observers such as William Franklin.3‛Ināyatallāh Shahīdī, Pazhūhish-i dar taʿziyah va taʿziyah-khvānī: az āghāz tā pāyān-i dawrah-yi Qājār dar Tihrān [A Study on Taʿziyah and Taʿziyah Performance: From the Beginning to the End of the Qājār Period in Tehran] (Tehran: Institute for Humanities and Cultural Studies, 2002), 172.

Figure 2: Husayn and Shimr, representing the protagonist and antagonist roles.

Figure 3 (right): The figure of Husayn, the protagonist.

Figure 4 (left): The figure of Shimr, the antagonist.

Figure 5: Shimr killing Husayn.

Figure 6: Shimr standing over the body of the slain Husayn.

In this article, I draw on Sigrid Weigel’s notion of figuration to explain how martyrdom and sacrifice function not merely as narrative elements but as culturally coded, affective forms. In Weigel’s use, figuration refers to a mode of representation that binds visual, textual, and ritual expressions to culturally embedded structures of meaning—particularly those surrounding violence, memory, and the sacred.4Sigrid Weigel, Märtyrer-Porträts: Figurationen des Opfers (Munich: Wilhelm Fink, 2008), ch. 3. This transformation of Taʿziyah’s performative nature—from a localized ritual act to a complex, semi-public theatrical practice—coincided with Iran’s broader cultural and political shifts. During the Qājār period (1785–1925), new socio-political dynamics, such as the rise of urban centers and encounters with modernizing forces, profoundly shaped Iranian cultural production. As a consequence of urbanization and modernization, traditional and modern forms of expression began to merge. This fusion paved the way for a cinematic grammar in which the depiction of martyrdom, sacrifice, and the figure of the hero-as-sacrifice—a character whose ethical stance is defined through voluntary suffering or death for a collective cause—reveals the aesthetic and ethical dimensions of Taʿziyah. In such representations, resistance and memory are not only thematized but cinematically enacted.

Historical Foundation and Internal Iranian Context

The evolution of taʿziyah is not simply a matter of linear historical continuity; it is also a dynamic process of aesthetic and formal transformation embedded in shifting religious and political structures. While its early instances during the Būyid dynasty (930–1062) manifest as communal processions and ritual lamentations, taʿziyah had not yet crystallized into a structured, codified form of performance. These early practices, as documented in sources such as Ahsan al-qisas by Ahmad ibn Abū al-Fath, reveal the emergence of key elements—public grief (collective mourning enacted in communal space), embodied memory (ritual actions that encode historical suffering in physical gestures),5Erika Fischer-Lichte, The Transformative Power of Performance: A New Aesthetics, trans. Saskya Iris Jain (London: Routledge, 2008), esp. 143–70. and symbolic acts (such as the carrying of water vessels to signify Husayn’s thirst). However, they lack the formalized dramaturgy, spatial arrangements, and character configurations that would later define taʿziyah as a theatrical ritual—a process explored in more depth in the following sections.6Ahmad ibn Abū al-Fath, Ahsan al-Qisas, as cited in Bahrām Bayzā‘ī, Namāyish dar Īrān [A Study on Iranian Theatre] (Tehran: Rushangarān, 1991), 115.

Under the Safavīds (1501–1722), taʿziyah evolved from disparate communal practices into a consolidated performance system, anchored in the state’s adoption of Shi’ism as both religious doctrine and political identity. This transformation affected not only the scale and institutionalization of taʿziyah but also its internal form. That is, the ritual developed into a structured theatre-ritual, encompassing defined roles—protagonists (muvāfiq-khvān), antagonists (mukhālif-khvān), and witnesses—choreographed spatial settings (takiyah), and a dramaturgy grounded in moral contrasts and emotional intensification. The Safavīd era thus marks the moment when taʿziyah shifted from processional movement to staged embodiment, from symbolic circulation to performative figuration.

The Qājār period (1785–1925) marked a significant expansion in the formal and narrative complexity of taʿziyah. With the construction of dedicated Takiyahs, ritual spaces were architecturally designed to intensify the emotional and aesthetic impact of the performances. Beyond its traditional focus on the events of Karbala, taʿziyah began to incorporate non-Islamic stories, thereby broadening its repertoire and challenging established boundaries of ritual tradition. This expansion not only diversified the thematic content but also tested the limits of what could be considered part of the ritual framework.

Concurrently, the formal grammar of taʿziyah — characterized by the use of doubling, direct address to the audience, stylized gestures, and non-linear temporality — became increasingly sophisticated, producing a distinctive theatrical vocabulary that blurred the lines between sacred ritual and public spectacle. Crucially, these formal developments were not isolated aesthetic innovations; they were shaped by — and responded to — shifting political and social pressures. The form of Taʿziyah evolved not only because artists sought new expressive techniques, but because taʿziyah’s very function within Iranian society changed from state-affirming ritual to a site of communal reflection, cultural negotiation, and at times, subversive political commentary.

Political History of Taʿziyah in the 20th Century: From the Constitutional Revolution to the Islamic Republic

The 20th century intensified these dynamics. The Constitutional Revolution (1905–1911) reframed Taʿziyah’s dramaturgy of martyrdom and resistance, aligning it with contemporary political struggles. The ritual’s moral binaries became were invested with new meanings, mapping onto real-world conflicts over justice, tyranny, and reform. Under Rizā Shah (1925–1941), Taʿziyah faced suppression. However, its formal elements survived, migrating into unofficial, provincial, or underground performances, where they assumed a more oppositional, even dissident function.

The early 20th century brought significant political upheaval to Iran, and with it, new interpretations and functions of taʿziyah. The Constitutional Revolution of 1905–1911, which sought to establish a parliamentary democracy, marked a pivotal moment in Iran’s modern history. Although ultimately suppressed by military force, the revolution’s ideals — justice, freedom, and resistance against tyranny — found symbolic resonance in the evolving dramaturgy of taʿziyah. Its moral binaries — the struggle between right and wrong, justice and oppression — were reactivated within the context of modern political discourse. The figure of the martyr, traditionally associated with Husayn of Karbala, came to represent broader national aspirations and political sacrifice — embodying not only religious virtue but also civic resistance and the quest for reform.7On the transformation of the martyr figure as a cultural and political construct, see Sigrid Weigel, Märtyrer-Porträts: Figurationen des Opfers (Munich: Wilhelm Fink, 2008), esp. ch. 1. Weigel describes the martyr not merely as a religious figure, but as a culturally coded embodiment of suffering, agency, and symbolic power within collective memory.

Under the Pahlavī dynasty, particularly during the reign of Rizā Shah (1925–1941), taʿziyah faced systematic suppression as part of the state’s top-down modernization and secularization policies. Rizā Shah’s government sought to curtail the influence of the Shi’i clergy, diminish public expressions of religious devotion, and recast Iran as a modern, centralized nation-state grounded in secular ideals. In this context, taʿziyah — a ritual theater deeply embedded in Shi’i religious memory and collective mourning — was perceived as incompatible with the new national image. Its performative structure, based on emotional intensity, historical lamentation, and mass participation, conflicted with the regime’s drive for order, discipline, and cultural Westernization.

As a result, taʿziyah performances were prohibited in urban areas, especially in Tehran, and gradually pushed to the margins — to provincial towns and villages, where they continued unofficially, often with reduced visibility and under threat of censorship. This marked a critical transformation in taʿziyah’s cultural function: from a state-affirming ritual with institutional backing, it became a form of subcultural resistance. Even under suppression, its formal strategies — symbolic abstraction, ritual repetition, and embodied memory — endured. These elements provided a persistent performative language through which the tensions of forced modernization, loss of religious identity, and political authoritarianism could be encoded and enacted.

The 1953 CIA-backed coup, which reinstalled Muhammad Rizā Shah, intensified this dynamic. In a political environment marked by censorship, surveillance, and repression, taʿziyah assumed renewed significance as a vehicle for both symbolic and political expression. The ritual’s core themes—martyrdom, sacrifice, and moral confrontation—resonated deeply with oppositional movements and intellectuals, connecting taʿziyah’s semiotic language to a broader cultural discourse of resistance and dissent. By the 1960s and 1970s, as Iranian cinema emerged as a major arena of aesthetic innovation and political reflection, the formal legacy of taʿziyah found new life on screen. Filmmakers such as Bahrām Bayzā’ī, Nāsir Taqvāʾī, and ʿAlī Hātamī did not merely draw on its thematic motifs—martyrdom, resistance, justice—but engaged directly with its performative structures. They appropriated taʿziyah’s non-linear temporality, stylized repetition, symbolic doubling, and direct audience address as cinematic strategies, translating its theatrical grammar into a visual idiom. This transposition underscores that the enduring power of taʿziyah lies not only in its religious or historical content, but in its formal plasticity—its capacity to migrate, transform, and regenerate across media while preserving its affective and ethical resonance. In these films, the moral and aesthetic tensions of taʿziyah were not archived as cultural relics, but reanimated as dynamic frameworks for reimagining national history, political trauma, and collective identity.8See Negar Mottahedeh, Representing the Unpresentable: Historical Images of National Reform from the Qajars to the Islamic Republic of Iran (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 2008), ch. 4.

The Islamic Revolution of 1979 marked the moment when taʿziyah ’s formal and symbolic logics were once again reinscribed into the national political imagination, not as a frozen religious artifact but as a living, adaptable performative grammar — that is, a set of embodied expressive conventions and symbolic forms shaping how meaning is enacted in performance. Revolutionary discourse drew deeply on the language of martyrdom, sacrifice, and righteous struggle, infusing political mobilization with the ethical significance of taʿziyah. Post-revolutionary Iranian cinema, shaped by both the upheavals of the revolution and the enduring legacies of taʿziyah, inherited not only the latter’s themes but also its performative strategies: the layering of presence and absence, the tension between historical memory and contemporary urgency, and the continual refiguration of sacrifice as both loss and agency. The cinema that arose from this period continues to explore questions of justice, resistance, and martyrdom identity. These themes resonate not only with Iran’s current political situation but also with the timeless ethical and affective power embedded in the taʿziyah tradition.

Political Change and Taʿziyah: Reception in the Pre- and Post-Revolutionary Era (1979)

In the later Pahlavī era, specifically in 1976, the Shiraz Arts Festival emerged as a significant platform for reviving both scholarly and artistic interest in taʿziyah by showcasing it as a vibrant, living cultural form. Although the festival was initially conceived to celebrate the heritage and artistic achievements of the pre-Islamic Persian Empire, it unexpectedly became a site for renewed engagement with Islamic ritual performance. This paradoxical focus brought together theater practitioners, scholars, and diverse audiences in a shared exploration of taʿziyah ’s performative and cultural significance. Iranian filmmaker and cultural organizer Farrukh Ghaffārī played a pivotal role by organizing a dedicated symposium on taʿziyah within the festival framework, during which prominent taʿziyah troupes presented fourteen performances that attracted international scholars and local spectators alike.

This moment of cultural discovery, however, was marked by significant misunderstandings. Much of the early Western academic engagement with taʿziyah relied heavily on comparative frameworks that failed to capture its unique formal and cultural complexity. Scholars often likened it to European Medieval Passion Plays or interpreted its emotional impact through the lens of Aristotelian concepts such as “catharsis.”9Richard Schechner, Performance Theory (London: Routledge, 1988), esp. on comparative models; Peter J. Chelkowski, Ta‘ziyeh: Ritual and Drama in Iran (New York: New York University Press, 1979), Introduction. However, these comparisons were rarely based on rigorous structural analysis or situated within the broader context of Persian artistic and literary traditions. Rather, they reflected superficial analogies driven by a tendency to fit the unfamiliar into familiar Western categories and hierarchies.

What was systematically overlooked was the multi-layered artistic nature of taʿziyah. In other words, early interpretations failed to recognize taʿziyah ’s integration of poetic forms, musical systems (dastgāh), performative codes, visual aesthetics, and philosophical dimensions—all of which are deeply woven into Persian cultural life.10Maryam Palizban, Performativität des Mordes: Aufführung des Märtyrertums in Ta‘ziya als ein schiitisches Theater-Ritual (Berlin: Kadmos, 2022), ch. 3. Understanding taʿziyah requires not only knowledge of Shi’a religious ritual or theater history but also familiarity with Persian literary intertextuality, miniature painting traditions, calligraphic symbolism, and the emotional registers of mourning (sūg, mātam) that permeate Iranian cultural expression. Without this integrated perspective, many interpretations reduce taʿziyah to an “exotic” religious spectacle or a primitive precursor to European dramatic forms. In doing so, they overlook its sophisticated synthesis of artistic, social, and spiritual elements.11Maryam Palizban, Performativität des Mordes: Aufführung des Märtyrertums in Ta‘ziya als ein schiitisches Theater-Ritual (Berlin: Kadmos, 2022), ch. 4, on the interweaving of music, poetry, and visual culture.

As I have argued elsewhere12Maryam Palizban, Performativität des Mordes: Aufführung des Märtyrertums in Ta‘ziya als ein schiitisches Theater-Ritual (Berlin: Kadmos, 2022), ch. 5, on the critique of epistemic asymmetries in Western reception., this interpretive negligence led to a form of epistemic reduction: taʿziyah was persistently framed through the lens of Western comparative aesthetics, without being understood as a living, internally coherent system of meaning embedded in Iranian cultural life. This distortion did more than flatten taʿziyah ’s complexity — it reproduced the deeper structural hierarchies of cultural authority, in which non-Western artistic forms were not only misread but systematically positioned as derivative, incomplete, or primitive in relation to an unmarked Western norm.

After the 1979 revolution and the establishment of the Islamic Republic (confirmed through a referendum in 1980), Shi’a Islam was not only reaffirmed as the state religion — it became the symbolic foundation of the nation’s reconfigured identity. This transformation unfolded most visibly during the eight-year Iran–Iraq War (1980–1988), which provided a historical and ideological stage on which the figures and narratives of Shi’a history were reactivated and repurposed. Although the conflict unfolded within the geopolitical tensions of the Cold War, its internal narration in Iran assumed a different register: it was framed as a defensive and existential war — not merely a matter of territorial integrity, but of spiritual survival. This framing was not without external corroboration. A United Nations report from December 9, 1991 (S/23273) explicitly identified Iraq as the initial aggressor, citing violations of international peace and security.13United Nations Security Council, “Report on the Situation between Iraq and Iran,” S/23273, December 9, 1991. Similarly, The Economist published on May 30, 1987 detailed the stark imbalance in military capacity between the two nations, indirectly reinforcing the perception of Iran’s isolation and victimhood.14The Economist, September 19–25, 1987. These documents, though politically neutral, lent unintended legitimacy to the Islamic Republic’s narrative: a nation under siege, resisting annihilation.

Within this framework, the war was not simply a military confrontation — it was sacralized, absorbed into the dramaturgy of Taʿziyah. Soldiers were no longer combatants in a conventional sense; they were cast as innocent martyrs, enacting a contemporary Karbala. The battlefield became a ritual space, and the fallen were transfigured into aesthetic-political figures of redemption. This cultural transformation — the transposition of sacred history into modern war — will be further explored in the next section.

Although the Islamic Republic defines its national and religious identity through Shi’a history and symbolism, the position of taʿziyah within this framework has remained paradoxical. Clerical and political authorities have repeatedly criticized or marginalized the ritual as an emotionally excessive and theatrically embellished distortion of Shi’a history. ‛Ināyatallāh Shahīdī, in his Taʿziyah va Taʿziyah-Khvānī, briefly acknowledges this tension, though it is not the central concern of his research.15‛Ināyatallāh Shahīdī, Pazhūhish-i dar taʿziyah va taʿziyah-khvānī: az āghāz tā pāyān-i dawrah-yi Qājār dar Tihrān (Tehran: Institute for Humanities and Cultural Studies, 2002), 63-69, 120-123. The stance of any political system toward a mass-moving performance practice is inherently fraught, and the Islamic Republic is no exception. While taʿziyah’s deep-rooted connection to revered Shi’a figures prevents its outright suppression, its imaginative and affectively charged reframing of sacred narratives continues to provoke ambivalence. It is precisely this capacity—to move between commemoration and reinterpretation, between devotion and theatricality—that renders taʿziyah a powerful but contested cultural form in post-revolutionary Iran.

Far from disappearing, taʿziyah continues to thrive in spaces beyond the gaze of state institutions and cultural authorities. Although it has been increasingly relegated to smaller towns and rural provinces, its social vitality remains unmistakable. When I visited a village near Isfahan in 2011, I encountered a newly built open-air arena dedicated exclusively to taʿziyah — a space with the capacity of a sports stadium. This encounter, striking in its scale and intentionality, revealed how taʿziyah endures not merely as a relic of the past but as a living cultural form that continues to shape communal identity, religious emotion, and aesthetic practice. It reminded my research team and me that taʿziyah persists not through official endorsement, but through grassroots devotion and affective memory — often in spaces that remain peripheral to the centralized cultural imaginary of the Islamic Republic.

Taʿziyah as Performance Practice16Here, “performance practice” refers to the collective, ritualized enactment of taʿziyah as a living tradition that integrates historical narrative, religious meaning, and social engagement.

At its core, taʿziyah stages the departure, resistance, and uprising of marginalized communities—key motifs deeply rooted in Shi’a history. The “departure” signifies exile or forced displacement, a rupture that initiates ongoing struggles for justice and recognition. These themes are not mere abstractions but lived experiences that shape collective memory and identity.

Approaching taʿziyah as a performance means engaging with it not simply as historical content but as a dynamic, communal practice. As Rainer Forst argues in The Right to Justification, human practices are inseparable from the justifications their participants make—to themselves and others—for their actions, whether explicitly stated or implicitly felt.17Rainer Forst, Das Recht auf Rechtfertigung (Berlin: Suhrkamp, 2007), 9. Each taʿziyah enactment thus functions as a communal assertion of legitimacy, embedding itself within a continuous chain of political, cultural, and religious contexts extending from early Shi’a Islam to the present day.

Building on earlier research, my analysis demonstrates that the moment of performance is a crucial space where history, ritual, and social practice intersect and interact. This intersection is not static but an evolving process through which collective identity and memory are continuously reinterpreted and reaffirmed. Understanding taʿziyah in this way moves beyond seeing it as a fixed religious or theatrical relic; instead, it reveals a living tradition that negotiates questions of power, justice, and belonging within the contemporary Iranian socio-political landscape.

Conceptual Framework on Taʿziyah

The concept of Taʿziyah presents fundamental challenges to theater studies. Since the 1960s, scholars have grappled with how to categorize it. On one hand, the absence of dramatic illusion combined with the intense audience engagement in taʿziyah has led to comparisons with the Brechtian Verfremdungseffekt and the Greek notion of catharsis; on the other hand, its deep ritual roots complicate these alignments and resist straightforward theatrical classification.18Parviz Mamnoun, “Ta‘ziyeh from the Viewpoint of the Western Theatre,” in Ta‘ziyeh: Ritual and Drama in Iran, ed. Peter J. Chelkowski (New York: New York University Press, 1979), 154–166; M. J. Mahjub, “The Effect of European Theatre and the Influence of Its Theatrical Methods upon Ta‘ziyeh,” in Ta‘ziyeh: Ritual and Drama in Iran, ed. Peter J. Chelkowski (New York: New York University Press, 1979), 137–153. Persian-language scholarship has likewise struggled with the terminology, oscillating between namāyish (“presentation,” “performance”) and broader concepts like āyīn-i namāyish (“ritual performance”), as used by figures like Bahrām Bayzā’ī and ʿInāyatallāh Shahīdī.19‛Ināyatallāh Shahīdī, Pazhūhish-i dar taʿziyah va taʿziyah-khvānī: az āghāz tā pāyān-i dawrah-yi Qājār dar Tihrān (Tehran: Institute for Humanities and Cultural Studies, 2002), 27.

The interdisciplinary nature of Taʿziyah—encompassing religious practice, literature, anthropology, and performance studies—makes it resistant to reductive definitions. Scholars such as Peter Chelkowski and Richard Schechner have emphasized its hybrid status, highlighting how Taʿziyah blurs the boundaries between ritual and theater. Complementing this view, Jalāl Sattārī argues that Shi’ism uniquely developed a form where ritual transforms into theater, coining the term “national drama.”20Jalāl Sattārī, Zamīnah-yi ijtimā‛ī-i ta‛ziyah va ti’ātr dar Īrān [The Background of Ta‘zieh and Theatre in Iran], (Tehran: Nashr-e Markaz 2008), 89. However, earlier Eurocentric frameworks often failed to grasp its embeddedness in Persian poetic, musical, and visual traditions, misreading it either as a primitive counterpart to Christian Passion Plays or isolating it as an “exotic” form of theater.21Maryam Palizban, Performativität des Mordes: Aufführung des Märtyrertums in Ta‛ziya als ein schiitisches Theater-Ritual (Berlin: Kadmos, 2019), 41–63.

To address these conceptual tensions, this article draws on ritual theory, particularly the work of Catherine Bell, and performance studies as discussed in Matthias Warstat’s works, to understand Taʿziyah not merely as a belief system materialized in performance, but as a cultural system in its own right; that is, as a processual, dynamic space where aesthetic, political, and ethical dimensions converge.22Catherine Bell, “Ritualkonstruktion,” in Ritualtheorien: Ein einführendes Handbuch, ed. Andréa Belliger and David J. Krieger (Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, 2008), 37; Matthias Warstat, “Beitrag zu Ritual,” in Metzler Lexikon Theatertheorie, ed. Erika Fischer-Lichte, Doris Kolesch, and Matthias Warstat (Stuttgart/Weimar: J. B. Metzler, 2005), 275. Rather than focusing on distinctions between “ritual” and “theater,” I argue that Taʿziyah operates precisely at their intersection, where belief, embodiment, and historical memory are performatively woven together.

The historical roots of Shi’ism are central to understanding Taʿziyah. Arising from disputes over succession after the death of the Prophet Muhammad, Shi’ite identity was profoundly shaped by the martyrdom of Husayn at Karbala in 680 CE — a foundational narrative of resistance against illegitimate power. From the early schisms to the formulation of the doctrine of the Twelve Imams and the long-standing marginalization of Shi’ite communities, the Karbala paradigm crystallized into both a spiritual and political template.23Moojan Momen, An Introduction to Shi‘i Islam: The History and Doctrines of Twelver Shi‘ism (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1985); Julius Wellhausen, Die religiös-politischen Oppositionsparteien im alten Islam (Berlin: Weidmann, 1901); Navid Kermani, “Martyrdom as a Trope of Political Self-Representation in Iran,” in Figurative Politics: On the Performance of Power in Modern Society, ed. Hans-Georg Soeffner and Dirk Tänzler (Opladen: Leske +Budrich, 2002), 89–100. It is within this framework that Taʿziyah emerged — not simply as a commemorative ritual, but as a reiterated act of embodied memory and protest, a theater-ritual whose aesthetic intensity remains inseparable from the historical wound it continually reinscribes.

The Aftermath of Karbala and the Ritualization of History as Political-Theological Paradigm

The aftermath of the Battle of Karbala in 680 CE marks a pivotal moment not only in Islamic political history but also in the formation of Shi’ite religious identity and ritual expression. After the brutal killing of Husayn ibn ʿAlī — the Prophet’s grandson — and his companions on the plains of Karbala, the surviving members of his camp, mostly women and children, were taken captive.24Farhad Daftary, The Ismāʿīlīs: Their History and Doctrines (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990), 101–110. They were paraded through the streets of Kufa and Damascus, the seat of the Umayyad Caliphate, in a deliberate display of imperial power. This coerced procession, intended as a performative assertion of Umayyad hegemony, was later reappropriated within Shi’ite ritual culture as a symbol of resistance — reenacted in passion plays and mourning ceremonies that transform defeat into defiance.

Among the captives, Zaynab, the sister of Husayn, emerged as a central figure of spiritual and political resistance. Her defiant speech in Yazīd’s court — delivered not with submission but with moral authority — has since been canonized as a founding moment of Shi’ite political theology.25Moojan Momen, An Introduction to Shiʿi Islam: The History and Doctrines of Twelver Shiʿism (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1985), 132–145. In this oration, she directly confronted tyranny and articulated a vision of justice rooted in the memory of Karbala, initiating a performative tradition in which speech, grief, and protest are inextricably linked.

The historical event of Karbala was gradually re-inscribed in Shi’ite collective memory as a mythic and sacred narrative, transforming a political and military defeat into a timeless paradigm of moral struggle. What had initially been a violent episode of suppression — the killing of Husayn and his followers by the forces of the Umayyad caliph Yazīd — was ritualized through oral transmission, poetic lamentation (mars̱iyah), and dramatized reenactments. Through these performative acts, Karbala was embedded into a sacred temporality that transcended historical contingency and became a cornerstone of Shi’ite communal identity.

The communalization of grief — that is, the transformation of personal mourning into a shared ritual practice — began in private settings but gradually evolved into public expressions of remembrance and protest. These developments were shaped by broader political conditions: the ʿĀshūrā commemorations gained increased visibility particularly during periods of relative tolerance or support for Shi’ism — for example, under the Abbasids in the eighth century and especially during the rule of the Būyid dynasty (tenth–eleventh centuries), which actively patronized Shi’ite institutions. Nevertheless, such commemorations remained deeply entangled in political tensions and power dynamics, often subjected to control, appropriation, or suppression by reigning authorities.

The institutionalization and aesthetic elaboration of taʿziyah reached its apogee during the Safavīd dynasty (1501–1722), when Shi’ism was enshrined as the official religion of Iran. In the process of consolidating political power and forging a unified Shi’ite identity, the Safavīd rulers strategically co-opted the narrative of Karbala as a legitimizing and mobilizing tool. Amidst the complex sectarian and geopolitical landscape of the early modern Middle East, the ritual culture of taʿziyah—encompassing mosque sermons, public processions, and dramatized commemorations—became central to both statecraft and religious life. The figure of the suffering Husayn, who resists unjust authority, was elevated as an archetype embodying moral-political resistance and spiritual sovereignty. This symbolic mobilization served not only to reinforce the divine right of the Safavīd rulers but also to embed a collective ethos of resistance and communal solidarity among Shi’ite subjects, thereby shaping a distinct socio-political consciousness.

Within Shi’ite theological discourse, Husayn’s martyrdom is not understood as a mere defeat, but as a deliberate, redemptive act of self-sacrifice in defense of divine justice (haqq). This refiguration casts martyrdom as an active ethical praxis—an existential stand that undergirds Shi’ite notions of cosmic order and moral agency. The ritual remembrance of Karbala during the month of Muharram, and especially on the tenth day—ʿĀshūrā, which is dedicated to Husayn’s martyrdom—serves as a performative re-enactment in which historical time collapses into ritual time. Unlike other days of mourning, which commemorate additional martyrs of the Karbala narrative, ʿĀshūrā is marked by the full dramatic rendering of Husayn’s final stand. In this commemorative frame, a liminal temporality emerges: a charged in-between space where the historical and the sacred interpenetrate, allowing participants to embody the events not as distant memory, but as present, living truth.26Mahmoud Ayoub, Redemptive Suffering in Islam: A Study of the Devotional Aspects of Ashura in Twelver Shiʿism (The Hague: Mouton, 1978), especially 142–153. See also Victor Turner, From Ritual to Theatre: The Human Seriousness of Play (New York: PAJ Publications, 1982), for his theorization of liminality in performance contexts.

This temporal and performative collapse is among the most distinctive features of taʿziyah, enabling an embodied and affective mimesis that differs fundamentally from Western theatrical paradigms. As Peter Chelkowski observes, the ritual does not merely represent historical events; it actualizes them. The stage becomes the space of Karbala itself, and the performers are not actors in the conventional sense but vessels through which the Imams and martyrs become present.27Peter Chelkowski, “Taʿziyeh: Indigenous Avant-Garde Theatre of Iran,” in Taʿziyeh: Ritual and Drama in Iran, ed. Peter Chelkowski (New York: New York University Press, 1979), 1–11. This form of sacred performance emphasizes presence over illusion, and spiritual immediacy over aesthetic distance, allowing the spectators to engage in a mode of witnessing that is both emotional and participatory.

Erika Fischer-Lichte’s concept of the “autopoietic feedback loop” is particularly germane here: through the dynamic interaction between performers and audience, taʿziyah generates a heightened, co-created reality in which ritual identification fosters profound communal and religious experience. This reciprocity effectuates a dissolution of conventional spectator-performer dichotomies and engenders a collective effervescence that reinforces Shi’ite communal bonds and sustains the socio-political paradigms encoded in the martyrdom narrative.28Erika Fischer-Lichte, The Transformative Power of Performance: A New Aesthetics (New York: Routledge, 2008), 83–90. While conventional performance theory often builds on binary oppositions such as performer/spectator or presence/representation, taʿziya challenges these categories by generating a ritual space in which such distinctions are suspended or transgressed. Rather than organizing the analysis around fixed dichotomies, this article seeks to reflect the fluid, affective, and co-constitutive logic of taʿziya itself.

Theatrical Structure and Ritual Function of Taʿziyah

Taʿziyah refers to a highly developed Iranian theater-ritual centered on the events of Karbala, with the figure of Husayn at its focal point. Over centuries, taʿziyah has evolved not merely as an extension of Shi’ite religious mourning but as a unique Iranian cultural form, intertwining epic storytelling (naqqālī), religious recitation (rawzah-khvānī), visual symbolism, and traditional musical forms. I use the term “theater-ritual”29Maryam Palizban, Performativität des Mordes: Aufführung des Märtyrertums in Ta‛ziya als ein schiitisches Theater-Ritual (Berlin: Kadmos, 2019), 29–33. here not in a generalized anthropological sense but to signal a hybrid form that fuses aesthetic performance and religious enactment—one that both stages and sacralizes. Taʿziyah thus stands apart from broad categories such as “Islamic performative practices,” which often fail to account for its specifically Iranian aesthetic, ritual lineage, and historical situatedness.

Figure 7: Battle of Karbala, by ‛Abbās al-Mūsavī (19th century). Brooklyn Museum, New York.

Unlike Western or Aristotelian dramatic forms, taʿziyah unfolds within a cyclical, ritual structure. The events of Karbala are not presented as a closed past but are ritually summoned into an ever-recurring now. This temporal reactivation collapses historical distance, drawing both actors and spectators into a participatory field where memory becomes affective encounter. The performance engenders a shared experiential space—not merely through representation, but through embodied witnessing—where the ethical stakes of Husayn’s stand against tyranny are collectively reinhabited. The outcome—the death of Husayn—is foreknown, yet its repetition intensifies, rather than diminishes, the emotional and spiritual charge: historical memory is not recited, it is relived as presence.

A notable dimension of taʿziyah is its moral structure: Husayn and his companions represent truth and justice, while Yazīd’s forces embody oppression and betrayal. This polarity is articulated not only narratively but also through a system of codified visual and sonic signs: the figures of righteousness appear in white or green, accompanied by lamenting melodies; the antagonists wear red or black, underscored by harsh, discordant sounds and exaggerated, violent gestures. These aesthetic elements function not as neutral theatrical devices but as carriers of ethical meaning, enacting a sensory grammar of virtue and transgression that is immediately legible to the community of spectators. In taʿziyah, form is never separate from ethical force—performance becomes an embodied ethics.

Women occupy a central symbolic position within taʿziyah, despite being traditionally portrayed by male actors (zan-pūsh). These portrayals are not attempts at imitation, but rather deliberate stagings that transform female figures—especially mothers and sisters—into ethical and affective icons. Characters such as Zaynab, Husayn’s sister, emerge as powerful voices of remembrance and resistance after the events of Karbala, embodying moral testimony rather than gendered realism. Their presence marks a sacralized and desexualized space, shaped by gestures of mourning, veiling, and ritualized speech. This symbolic order, often reinforced by the presence of children and animals on stage, reflects a broader “aestheticization of the real,” wherein family structures and social taboos—particularly around incest and martyrdom—are transfigured into theatrical and ethical forms.30Maryam Palizban, Performativität des Mordes: Aufführung des Märtyrertums in Taʿziya als ein schiitisches Theater-Ritual (Berlin: Kadmos, 2022), 68–75.

Figure 8: The figure of Zaynab, Husayn’s sister, featured in a ta‛ziyah performance.

Figure 9: Children participating in a taʿziyah commemorating the martyrdom of Husayn.

What makes taʿziyah particularly distinctive is its capacity to integrate a wide array of stories and historical settings while remaining anchored in the Karbala paradigm. Even when narratives unfold in other temporal or geographic contexts, the Karbala story is invoked and woven into the fabric of the performance. This demonstrates the integrative and adaptive power of taʿziyah, allowing it to respond to contemporary social or political concerns without ever relinquishing its foundational symbolic structure centered on martyrdom, sacrifice, and moral struggle. While these concerns are relevant, they should be addressed in other studies, as they fall outside the scope of the present article.

The spatial configuration of taʿziyah performances plays a crucial role in shaping the ritual experience. Traditionally performed in open, circular spaces (maydān), often in public squares or courtyards, the stage is surrounded on all sides by the audience. There is no separation between stage and spectator, no proscenium arch, no darkened auditorium. Spectators are free to move, to change their position, or even to leave the space during the performance. This openness creates a fluid and participatory atmosphere, where the audience is not passively seated in fixed rows but is dynamically engaged, both physically and emotionally, in the unfolding of the ritual drama. The absence of spatial separation amplifies the collective dimensions of grief and ethical reflection, reinforcing the shared nature of the experience.

This article asserts that taʿziyah should not be understood merely as a passion play or a fixed religious theater form, but rather as a dynamic, evolving ritual-theatrical system. It mobilizes multiple layers of Iranian cultural expression—poetic, musical, visual, and embodied—and inscribes them into a space of communal ethical encounter. By “communal ethical encounter,” I refer to the performative creation of a shared realm in which spectators and performers alike engage in mourning, remembrance, and moral reflection. Through its formal flexibility, profound moral resonance, and intimate spatial dynamics, taʿziyah functions as a potent medium for transmitting collective memory, shaping communal identity, and articulating political and ethical concerns across generations.

One of the most profound dimensions of taʿziyah lies in its ritual manipulation of time. The events of Karbala are not staged as distant historical occurrences, but as events unfolding in the immediate present. Within the performative logic of taʿziyah, the past is not represented but re-enacted, re-lived. For the spectators, this is not a symbolic remembrance of something that has passed, but a direct encounter with a recurring, lived present. This ritual presentism collapses historical distance and transforms the audience into witnesses rather than mere observers—a shift that is not only emotional but also epistemological, as it produces embodied historical knowledge.

Such a temporal structure carries far-reaching implications. It produces a cyclical vision of history, in which martyrdom is not framed as final defeat, but as a constantly renewed testimony to divine justice. Each year, Husayn’s death is not merely commemorated, but ritually re-lived—an act through which the longing for a just world is once again collectively affirmed. In this way, taʿziyah operates both as an open wound and as a healing gesture: it keeps the trauma alive, but precisely in doing so, it turns the wound into a source of communal resilience and spiritual endurance.

Crucially, taʿziyah achieves this not only through ritual temporality but also through the way it frames the sacred figures: as a family. The saints are not remote icons but fathers, mothers, sons, daughters, brothers, whose bonds mirror those of the spectators. This familial framing deepens the emotional connection between stage and audience, collapsing not just historical, but existential distance. It is here, in this intimate proximity, that we can begin to trace the resonances between taʿziyah and cinema — between ritual theater and filmic representation — and ask how both forms build their power on the dynamic interplay of memory, affect, and embodiment.

Between Ritual and Screen: Taʿziyah and the Question of Cinema

What becomes of taʿziyah’s capacity to transform historical trauma into a living, cyclical presence when it enters the medium of cinema? How can a ritual-theatrical form—rooted in bodily co-presence, collective mourning, and temporal repetition—be translated into a cinematic language shaped by framing, montage, and mediated time?

At first glance, ritual performance and cinema might appear as opposing modes of expression: one grounded in immediacy and shared space, the other unfolding in the dislocated temporality of recorded images. Yet they are united by a deeper logic of affect and spectatorship. Both activate the body of the viewer, both mobilize memory through form, and both draw their power from transforming spectators into witnesses.

In taʿziyah, the portrayal of the sacred as familial—not as distant religious abstraction, but as embodied figures of fathers, mothers, and children—creates an intimate relational field. It binds the audience emotionally and ethically to the suffering enacted before them. The spectators are not merely watching; they are drawn into the drama as mourners and co-witnesses. This affective logic reverberates in Iranian cinema, where the influence of taʿziyah can be traced in the ways films construct familial and historical relationships, inviting the viewer into a space of shared remembrance and emotional re-experiencing.

This section will explore how the structures of taʿziyah — its ritual temporality, its affective force, and its emphasis on familial connection — have shaped the aesthetics and narrative strategies of Iranian cinema. By examining specific films, we will ask: How does cinema inherit, transform, or even betray the ritual logic of taʿziyah? And how does this ongoing negotiation reveal deeper tensions between tradition and modernity, between collective memory and individual spectatorship?

Among the filmmakers most deeply engaged in the project of aesthetic de-westernization, Bahrām Bayzā’ī stands out as a central figure. As both playwright and filmmaker, Bayzā’ī developed a highly distinctive style that draws on pre-Islamic myth, Persian epic traditions, and indigenous performance forms—particularly naqqāli (storytelling) and taʿziyah. For Bayzā’ī, these elements are not cultural quotations, but formal reservoirs: they offer alternative dramaturgies, temporalities, and modes of spectatorship that resist dominant cinematic conventions.

His film Marg-i Yazdgird (Death of Yazdgerd, 1982) exemplifies this approach. While set in the pre-Islamic Sasanian era and revolving around the mysterious murder of the last Sasanian king, the film eschews linear historical reconstruction. Instead, it unfolds as a ritualized investigation: a courtroom of memory, composed of testimonies, re-enactments, and ever-shifting versions of the same event. The circular structure destabilizes chronology and draws the viewer into a temporality of repetition and uncertainty. This is where the resonance with taʿziyah becomes palpable—not because the content mirrors Karbala, but because the film enacts a similar dramaturgy of collective witnessing, ethical interrogation, and the endless re-staging of a trauma that refuses closure.

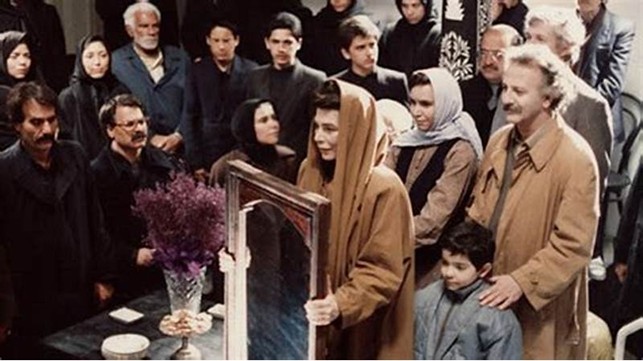

Figure 10: Still from Marg-i Yazdgird (Death of Yazdgerd), directed by Bahrām Bayzā’ī, 1982.

These strategies are already present in Bayzā’ī’s earlier works. In Qarībah va Mih (The Stranger and the Fog, 1974), the arrival of a nameless stranger in a fog-shrouded village triggers a series of symbolic confrontations between past and present, community and outsider, memory and forgetting. The film’s slow, ritualized pacing and its charged visual atmosphere recall the processional quality of taʿziyah, where every gesture and movement acquires symbolic weight.

Figure 11: Still from Qarībah va Mih (The Stranger and the Fog), directed by Bahrām Bayzā’ī, 1974.

In Kalāq (The Crow, 1976), Bayzā’ī stages an allegorical narrative in which the figure of the crow functions as both omen and witness—echoing the doubling of roles and the symbolic condensation characteristic of ritual theater. The story follows a woman whose fiancé has disappeared under mysterious circumstances; her search for the truth is interwoven with dreamlike sequences in which the crow appears repeatedly, blurring the line between memory, hallucination, and fate. The crow, as an ambiguous figure, serves both as a harbinger of loss and a silent observer of unfolding events, embodying a presence that is both external and internal to the characters’ psyche. Here, too, Bayzā’ī resists Western narrative closure, opting instead for an open-ended, mythic structure that invites reflection rather than resolution.

Finally, Charikah-yi Tārā (Ballad of Tara, 1979) weaves together historical legend and contemporary rural life, focusing on a woman who inherits a sword from an ancient warrior. As Tara navigates between the everyday and the mythic, the film a space where past and present, legend and lived experience, ritual and realism constantly intersect — again recalling the temporal layering of taʿziyah, where the Karbala events are not confined to history but enacted anew in each performance.

Near the end of Charikah-yi Tārā, a striking moment crystallizes this intertwining of history, myth, and emotional wound. An army of the dead rises from the sea, and among them is the fallen hero with whom Tara has fallen in love. Yet instead of fulfilling the promise of union or resolution, the warrior disappears, leaving Tara alone — wounded not just by personal abandonment, but by the deeper historical betrayal embodied in the figure of the dead soldier. This moment transforms the mythical encounter into an allegory of historical rupture: Tara’s wound is not merely romantic, but becomes a symbol of the unhealed, cyclical wounds that run through Iranian history, where the past continually returns, yet never offers closure.

Figure 12: Still from Charikah-yi Tārā (Ballad of Tara), directed by Bahrām Bayzā’ī, 1979.

Here, the emotional landscape of the film converges with what I call the performative logic of taʿziyah—that is, the way in which ritual repetition, embodied affect, and present-tense enactment allow historical wounds to be relived rather than resolved. The dead are not gone, the past is not past, and every attempt at reconciliation reopens the trauma. The viewer is drawn into a space where the private and the collective, the intimate and the historical, become indistinguishable — echoing the way taʿziyah binds individual grief to communal mourning, personal loss to the cosmic drama of injustice.

Perhaps the most haunting of Bayzā’ī’s meditations on time, death, and narrative is Musāfirān (The Travelers, 1991), a film that opens with a family preparing for a wedding celebration. What they do not know — and what the viewer gradually comes to understand — is that the expected guests have already died in a car accident on their way to the ceremony. The house fills with anticipation, ritual gestures of hospitality and joy, while the specter of death quietly occupies the frame, never fully seen, yet always present.

What makes Musāfirān so powerful is not merely its tragic premise, but its intricate layering of temporal and emotional registers. The dead and the living coexist in the same cinematic space; moments of celebration are shadowed by mourning. The viewer, knowing what the characters do not, becomes a kind of ritual witness, drawn into a liminal temporality where catastrophe unfolds not once, but continually. This slow, ceremonial pacing echoes the temporal logic of taʿziyah, where the death of Husayn is not a singular historical moment, but a recurring enactment — a wound re-entered through each performance. In Musāfirān, the characters seem to drift through a world suspended between awareness and unknowing, their movements shaped less by narrative cause and effect than by the gravity of mourning itself.

Figure 13: Still from Musāfirān (The Travelers), directed by Bahrām Bayzā’ī, 1991.

With Musāfirān, Bayzā’ī brings his earlier engagements with myth and historical memory into a sparse, ritualized cinematic language. This is not a cinema of resolution, but of deferral — where storytelling itself becomes a gesture of remembrance, and loss is performed rather than narrated. Across these films, Bayzā’ī’s work might be described as a form of ritual modernism: a cinematic practice that draws less from Western avant-garde aesthetics than from the embodied traditions of Iranian performance. By working with repetition, symbolic condensation, and cyclical time, Bayzā’ī constructs a cinematic space that resonates deeply with the structures of taʿziyah, even when the films themselves are not explicitly religious.

While Bayzā’ī’s cinema draws its strength from overt invocations of myth, epic, and theatrical ritual — weaving dense symbolic tapestries that directly confront cultural memory — ‛Abbās Kiyārustamī approaches the question of ritual from another angle. His minimalism, observational precision, and the porous boundary between fiction and documentary might seem far removed from the heightened theatricality of taʿziyah or its allegorical forms in Bayzā’ī’s films. Yet Kiyārustamī, too, is deeply invested in similar questions: How do we witness suffering? How does repetition, reenactment, or even the smallest performative gesture shape our perception of reality? And how might cinema — like taʿziyah — call upon its audience not simply to watch, but to become ethically and emotionally involved?

Where Bayzā’ī reactivates historical and mythical trauma through spectacle and symbolic condensation, Kiyārustamī stages a quieter kind of ritual: one built on minimal variation, careful repetition, and a continual unsettling of the line between performance and life. In both bodies of work, however, we encounter a cinema that resists linear resolution and clear closure — a cinema that invites the viewer to participate in the very unfolding of the experience. This active engagement with the artwork — the insistence that viewing is never neutral — is what both filmmakers inherit, in different registers, from the structure of taʿziyah. The audience is not a mere observer, but an emotionally implicated witness.

At first glance, minimalism and ritual may appear to stand at odds: the one strips away ornamentation, paring down to essentials; the other is often associated with symbolic excess, repetition, and heightened affect. And yet, the two converge in their temporal and attentional structures. Ritual is not only a matter of spectacle — it is a disciplined form, grounded in repetition, embodied rhythm, and the slow unfolding of meaning over time. In this light, minimalism can be understood as a ritual of reduction: a practice that hones perception, calibrates attention to subtle shifts, and invites the viewer into a durational experience where meaning is never given all at once, but emerges through sustained engagement.

In cinema, minimalism often foregrounds slowness, silence, and open-endedness, drawing the viewer into a meditative state that parallels the reflective space of ritual. The sparse aesthetic is not a withdrawal from meaning, but an invitation to participate more actively — to become attuned to subtle shifts, to fill in gaps, to confront the uncertainties that underlie the visible world. Like ritual, minimalist cinema creates a heightened awareness of presence and absence, of what is shown and what is withheld, and thus positions the viewer not as a passive recipient but as a co-creator of meaning.

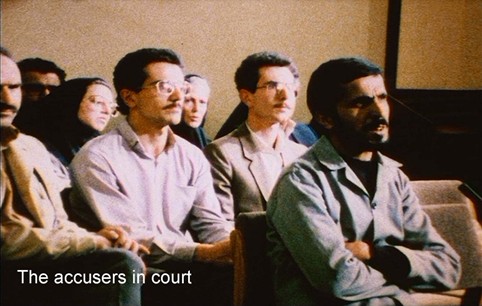

Among Kiyārustamī’s mature works, Close-Up (1990) stands as perhaps the most direct cinematic parallel to taʿziyah’s ritual logic. The film restages the real-life trial of Husayn Sabziyān — a man who impersonated filmmaker Muhsin Makhmalbāf, was taken in by a middle-class family, and later arrested. Yet instead of documenting the case as a linear narrative, Kiyārustamī invites those involved — Sabziyān, the family, the judge — to re-enter their own memories and re-enact their roles on screen. In doing so, Close-Up transforms testimony into performance, history into ritual: the trial is not only recounted but re-lived, not to determine guilt, but to probe the emotional and ethical ambiguities beneath the surface of truth. This gesture — of returning to a wound, of embodying memory — echoes the structure of taʿziyah, where the past becomes present not through representation, but through its affective repetition.

Figure 14: Still from Close-Up, directed by ‛Abbās Kiyārustamī, 1990.

Here, the resonance with taʿziyah becomes unmistakable: Close-Up collapses historical distance, turning the viewer into a witness of a moral and existential drama that is both lived and staged, present and past. As in a taʿziyah performance — where the trauma of Karbala is not narrated but re-experienced — ‛Abbās Kiyārustamī’s film does not depict a closed episode of deception and humiliation, but reopens it, charges it with immediacy, and transforms it into a shared emotional space. Re-enactment here is not simply a formal strategy, but an ethical gesture: a refusal of closure, a way of holding open the wound so that it may be witnessed rather than silenced. In this gesture lies the film’s quiet radicalism — its insistence that cinema, like ritual, can carry memory not through explanation, but through affective presence.

This ritual dimension deepens in Ta‛m-i Gīlās (Taste of Cherry, 1997), a spare, meditative film about a man, Mr. Badī‛ī, who drives through the dry hills outside Tehran, searching for someone willing to bury him after his planned suicide. The film unfolds like a pilgrimage stripped to its essentials — not towards redemption, but toward silence. Along the way, Badī‛ī meets a series of men — a soldier, a seminarian, a taxidermist — each encounter echoing the previous one, each response subtly shifting the emotional register of the film. These repetitions do not build toward a conventional climax, but accumulate into a rhythm of listening and refusal, of presence and withdrawal. When the final man accepts Badī‛ī’s request, the moment brings not resolution but a fragile, suspended openness — a gesture that neither affirms nor negates the will to die, but holds both possibilities in tension.

Here, too, Kiyārustamī constructs a kind of secular taʿziyah: a ritual journey centered on death, loss, and the search for meaning, where the audience is invited not to judge or resolve, but to accompany, to witness, to inhabit the space of uncertainty. The minimalism of the film, its long takes and silences, functions like a meditative frame, opening up a contemplative space akin to the ritual temporality of taʿziyah, where what matters is not the plot, but the emotional and ethical weight carried by each moment, each repetition, each encounter.

Figure 15: Still from Ta‛m-i Gīlās (Taste of Cherry), directed by ‛Abbās Kiyārustamī, 1997.

In both Close-Up and Taste of Cherry, Kiyārustamī crafts a cinema of active witnessing, where the viewer is drawn into an unfolding drama that resists closure and demands ethical engagement — much like the spectator in a taʿziyah performance, who is not merely watching, but sharing in the collective re-experiencing of human vulnerability, moral failure, and the ever-repeating question of redemption. Kiyārustamī’s cinema, particularly from the late 1980s onward, marks one of the most radical shifts in Iranian narrative tradition, bringing minimalism and reflexivity to the center. While his films may, at first glance, seem worlds apart from the ceremonial intensity of taʿziyah, they are guided by similar structural and temporal logics: repetition, the dissolution of boundaries between fiction and reality, and the transformation of spectatorship into a form of participatory witnessing.

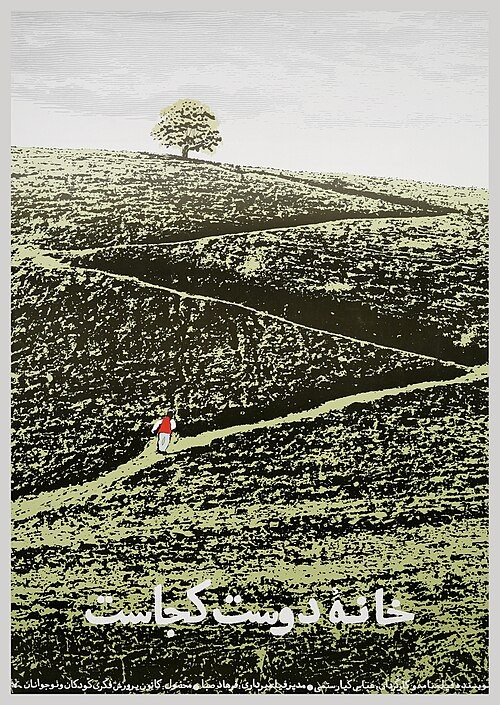

Figure 16: Film poster for Khānah-yi dūst kujāst (Where Is the Friend’s House?), directed by ‛Abbās Kiyārustamī, 1987.

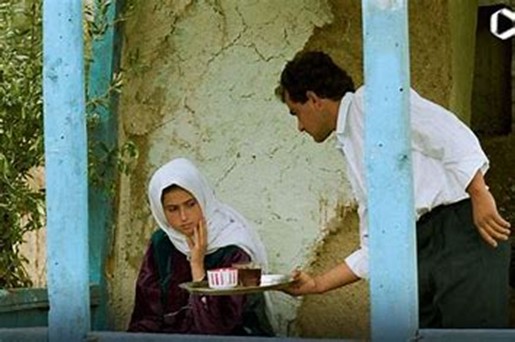

Figure 17: Still from Zīr-i dirakhtān-i zaytūn (Through the Olive Trees), directed by ‛Abbās Kiyārustamī, 1994.

In Khānah-yi dūst kujāst (Where Is the Friend’s House? 1987), Zindagī va dīgar hīch (Life, and Nothing More, 1992), and Zīr-i dirakhtān-i Zaytūn (Through the Olive Trees, 1994), ‛Abbās Kiyārustamī constructs a loose trilogy that returns again and again to the same village, the same earthquake-stricken landscape, the same constellation of human encounters. Rather than providing narrative closure, each film reopens the questions posed by the previous one. The trilogy functions less as a linear sequence than as a layered ritual: it circles back over sites of loss, gestures of survival, and the fragile continuity of life in the wake of disaster. This structure parallels the cyclical temporality of taʿziyah performances, which do not “resolve” historical trauma but continually re-enact it, keeping its emotional and ethical stakes alive. In both cases, repetition is not redundancy but a mode of ethical presence — a way of insisting that certain wounds cannot be closed, only carried forward. Kiyārustamī’s self-reflexive cinematic strategies — his frequent acknowledgment of the camera, the porous boundary between actors and non-actors, and the visible presence of the filmmaking process itself — resonate with the meta-theatricality of taʿziyah. Just as performers in taʿziyah oscillate between sacred role and embodied presence, so too do Kiyārustamī’s films continually remind the viewer that they are watching an act of staging, of re-presentation. The viewer is thus not a passive observer but an implicated witness.

Kiyārustamī’s minimalism, far from being an aesthetic of absence, becomes a ritual practice of attention. By paring down cinematic elements to their essentials — gesture, gaze, landscape, silence — he sharpens the viewer’s awareness of repetition, variation, and affective resonance. The everyday becomes saturated with historical weight. In this light, Kiyārustamī’s cinema transforms the act of looking into a ritual of witnessing. Like the taʿziyah stage, where every gesture and every disruption of illusion bears the imprint of collective memory, his films invite the audience into a space where the visible world becomes charged with invisible histories — a sacred dramaturgy of the ordinary.

Yet ritual and theatricality in Iranian cinema take many forms — not all of them follow the path of minimalist reflection or mythic gravity. Farrukh Ghaffārī’s Zanbūrak (The Falconet, 1975), for instance, engages with historical and performative traditions in a radically different register. Where Kiyārustamī distills narrative into meditative slowness, Ghaffārī amplifies artifice: his mode is one of exaggeration, irony, and farce. Zanbūrak stands out precisely because it draws not only on historical legend but also on the popular aesthetics of theatrical play. Characters shift allegiances with puppet-theater-like abruptness; battles unfold in grotesquely stylized rhythms; and the titular zanbūrak — a small falconet cannon — functions less as a weapon of war than as a theatrical prop, unleashing narrative chaos instead of heroic resolution. This dramaturgy echoes forms such as shadow play and traditional puppet theater (khaymah shab bāzī), where exaggeration, playfulness, and artificiality are not only accepted but celebrated — and where moral or historical reflection is inseparable from stylized, performative excess.

Unlike Kiyārustamī, Ghaffārī does not seek ritual solemnity or ethical minimalism. Instead, he stages history as grotesque farce — revealing the absurd machinery of power, corruption, and betrayal. And yet, even in this satirical mode, Zanbūrak retains a logic of theatrical self-awareness that resonates with taʿziyah.31Michelle Langford, Allegory in Iranian Cinema: The Aesthetics of Poetry and Resistance (London: Bloomsbury, 2019), 45–60. Like taʿziyah, it foregrounds the act of performance itself: spectators are reminded that what they watch is a constructed spectacle, not a transparent window onto the past. Performance here becomes a reflexive space, in which the theatrical representation of history — even through parody — invites ethical reflection and collective awareness.

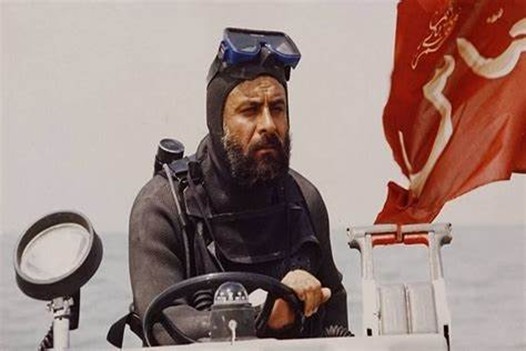

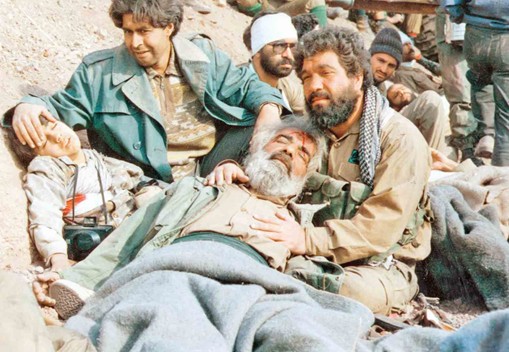

Beyond the experimental works of Bayzā’ī, Kiyārustamī, or Ghaffarī, another crucial strand of post-revolutionary Iranian cinema engages with taʿziyah not through its formal or ritual structure, but through narrative thematics. With the outbreak of the Iran–Iraq War (1980–1988), a new cinematic genre emerged — the so-called “Sacred Defense Cinema” (sīnimā-yi difāʿ-i muqaddas) — which reactivated the martyrdom narratives at the core of Shi’i religious imagination. In these films, themes of sacrifice, loyalty, and resistance are transposed directly onto the contemporary battlefield: soldiers become modern-day shuhadāʾ (martyrs), their deaths reverberating with the echo of Husayn and his companions at Karbala. Yet unlike the formal, performative logic of taʿziyah-inflected art cinema, this reference remains largely textual and allegorical — used to frame present-day events within a sacralized narrative of loss and redemption. These films, often state-sponsored or ideologically aligned, functioned as instruments of wartime propaganda: reaffirming religious ideals, national identity, and the sanctity of the ongoing conflict.

Figure 18: Still from “the Sacred Defense” film Ufuq (Horizon), directed by Rasūl Mullāqulīpūr, 1989.

Figure 19: Still from “the Sacred Defense” film Safar bih Chazzābah (Journey to Chazabeh), directed by Rasūl Mullāqulīpūr, 1996.

And yet, beyond their ideological function, these films contributed to an ongoing process of actualization: the continuous re-embedding of the Karbala paradigm into the lived and dying bodies of a new generation. In this sense, the war films of the 1980s and beyond extended the reach of taʿziyah’s martyr narratives, transforming them into cinematic myths that speak not only of historical grief, but of immediate, contemporary sacrifice. These war films, then, operate almost like taʿziyah performed on a sealed stage — oriented in one direction, filmed for the camera rather than enacted for a living community. Crucially, they forgo one of taʿziyah’s most vital theatrical principles: the dialectic of “playing” and “letting play,” the spatial openness that invites the spectator into the unfolding ritual. In their unidirectional form, they lose the carnivalesque disorder and archaic multiplicity that animate the ritual. What remains is no longer taʿziyah, but a fixed cinematic allegory — one that severs the performative core of the theater-ritual and replaces it with monumental myth.

What, then, does taʿziyah offer to the cinema — and why has its echo endured so persistently across decades of Iranian filmmaking?

At its heart, taʿziyah is not merely a story of martyrdom; it is the ritual reopening of a historical wound. Each performance does not close the wound of Karbala but insists on keeping it raw, exposed, and unresolved. It transforms grief into an active, public practice — turning private loss into a space of communal endurance and shared affect. Taʿziyah does not mourn in solitude; it collectivizes pain, brings familial intimacy into the realm of the political, and turns memory into motion.

In Iranian cinema, this ritual impulse has taken many forms. Filmmakers like Bayzā’ī and Kiyārustamī have explored it as a formal tension: how can the screen carry the weight of suspended time, of layered histories, of masks and echoes and the silent presence of the spectator? Others, especially in the Sacred Defense films, channel the wound more directly into national allegory, where the Karbala paradigm is mobilized to sanctify contemporary violence — transforming religious grief into state ideology. Yet even this binary — between formalist abstraction and ideological instrumentalization — proves unstable. In recent decades, a younger generation of filmmakers has approached taʿziyah not as a structure or doctrine, but as a dispersed aesthetic force: a grammar of doubling, absence, symbolic fracture.32Max Bledstein, “Allegories of Passion: Taʿziyeh and the Allegorical Moment in Shahram Mokri’s Fish and Cat,” Monstrum 4 (2021): 104–21; Khatereh Sheibani, The Poetics of Iranian Cinema: Aesthetics, Modernity and Film after the Revolution (London: I.B. Tauris, 2011), 85–106. In their work, the ritual does not appear as direct citation but as spectral trace — in broken timelines, haunted domestic spaces, suspended endings. Taʿziyah survives here less as iconography than as atmosphere, less as representation than as performative residue.

What emerges across these varied expressions is a cinematic landscape shaped by a deep, often unhealed memory — a historical wound that cinema, like taʿziyah, cannot resolve, but can re-enact, make visible, and keep alive. Here, the theater-ritual becomes not a fixed form, but a restless force, shaping how Iranian cinema imagines time, community, and the fragile line between remembering and reliving.

But taʿziyah is, ultimately, also a performance — and like any performance, it can succeed or fail. There are strong ensembles and weak ones; powerful stagings and hollow ones. The ritual’s transformative potential only unfolds when all elements — gesture, music, voice, atmosphere, and presence — converge into a living totality.33Peter Chelkowski and Hamid Dabashi, Staging a Revolution: The Art of Persuasion in the Islamic Republic of Iran (New York: New York University Press, 1999), 42–53. It is precisely this fragility, this dependency on the moment of enactment, that ties taʿziyah so intimately to the theater — and that marks its most fertile legacy for cinema. For both are time-based arts that depend on the balance between form and fracture, between intention and event. Taʿziyah reminds us that not all rituals function, but when they do, they produce something more than narrative: they become happening.34ichard Schechner, Performance Theory (New York: Routledge, 2003), 123–150. See also Erika Fischer-Lichte, The Transformative Power of Performance: A New Aesthetics (London: Routledge, 2008), esp. on the concept of the “happening” as an emergent, communal event.

This logic of repetition resists finality. Just as taʿziyah insists on mourning again and again — never the same, always re-entered through loss — so too does Iranian cinema return to its dead not to resolve the past, but to remain proximate to what has been extinguished. The cinematic afterlife of taʿziyah is thus not simply historical reference, but ontological stance: a way of inhabiting time, of confronting unfinished histories, of holding space for what cannot be closed. Ultimately, taʿziyah lives on in Iranian cinema not merely as a thematic residue, but as a mode of perception — a structure of feeling that binds the present to a wound that refuses to fade. This is its deepest cinematic gift: not catharsis, not redemption, but the insistence that some losses must be carried — through performance, through gesture, through repetition — until the very act of bearing becomes its own kind of resistance.