Representation of Women in Rasūl Mullāqulīpūr’s Cinema

Figure 1: Maryam’s reaction to the approach of an Iraqi soldier. Still from The Survivors (Nijāt-yāftagān), directed by Rasūl Mullāqulīpūr, 1996.

Introduction

There is always an idea of what the inhabitants of a place should be, as this makes it much easier for the rulers to govern. In the constructed reality of those in power and those who seek to maintain the social and political order in line with their vision of an ideal society, nation, country, or community, such idealized figures are reproduced through official media.

In the Islamic Republic of Iran, representations supported by the regime portray only one ideal type of man and woman. These depictions are especially prominent in genres aligned with official discourse, such as art and cinema related to war. The regime has found in war discourses a means of preserving the notion of exceptional times, referencing the cohesion seen during the Iran-Iraq War, and thus justifying ongoing violations of rights and liberties, particularly against dissenting voices.

This article analyzes the reproduction of Fatīmah and Zaynab as the ideal figures for Iranian women to emulate. It begins by examining how the construction of the ideal woman is justified within the sociopolitical and religious framework of the Islamic Republic. The discussion then turns to the two main figures of emulation, Fatīmah and Zaynab, and the specific contexts in which each is invoked. The final part explores how these figures are represented in war cinema, with a particular focus on two films by Rasūl Mullāqulīpūr.

The production of Mullāqulīpūr has been selected over that of other directors due to his career-long focus on the war genre and his clear alignment with the official state ideology. His films hold significant status within the official cultural sphere; even Ibrāhīm Hātamīkiyā has recognized him as pioneer of Iran’s distinctive war cinema aesthetics and narrative approach to depicting the experience of battle and conflict.

Furthermore, in the post-war period, Mullāqulīpūr was the first director to explore women’s experience of war. However, the female characters in his films are portrayed from a male perspective, often as idealized representations of what women are expected to be, rather than as complex individuals with agency, decision-making power, and personal autonomy.

Idea of Woman

The concept of “woman” is often constructed as singular, allowing for only one acceptable model of womanhood. Occasionally, alternative variations emerge to respond to specific historical moments or exceptional circumstances. However, under most conditions, women are typically presented with a single, prescriptive role to fulfill or aspire to. This is why the rhetoric surrounding womanhood teds to be uniform, pointing to one idealized image of a woman.

This ideal woman is reinforced through constant, often imperceptible, reminders of what women should be and what roles they are expected to play. These reminders permeate daily life through media portrayals of “good” versus “bad” women, or through fictional characters depicted as role models who exemplify the correct way of living. In addition to these subtle influences, there are explicit sources of ideological reinforcement. For example, ‛Alī Sharī‛atī once claimed that “it is natural that the sexual differences cause class differences. Men fall into the class of ruling and owning, and women fall into that of the ruled and the owned.”1‛Alī Sharī‛atī, Fatima is Fatima (IslamicMobility.com, 1971), 99, https://www.islamicmobility.com//pdf/Fatima_is_Fatima.pdf. Similarly, Murtazā Mutahharī argued that while Islam granted women rights and liberty, it never encouraged them to rebel against or become cynical toward men.2Murtazā Mutahharī, Los derechos de la mujer en el Islam (Mexico City: Islamic Republic of Iran Embassy in Mexico, 1985); For its translation in English, see The Rights of Women in Islam, https://al-islam.org/rights-women-islam-murtadha-mutahhari

Figure 2: Maryam walking with the flag of the Basījīs she helps rescue. Still from The Survivors (Nijāt-yāftagān), directed by Rasūl Mullāqulīpūr, 1996.

Although the statements by Sharī‛atī and Mutahharī were made several decades ago, their underlying assumptions remain in the collective mindset of many Iranians, particularly among those aligned with the regime and conservative ideologies. The belief that women belong primarily in the private sphere, and that domestic labor is their principal duty, continues to dominate public discourse. Other roles, whether professional, academic, or political, are generally viewed as optional and secondary to the successful performance of reproductive labor.

A central mechanism for maintaining this ideal is legislation concerning reproduction, especially pronatalist policies. Political control over women’s bodies has been a strategic tool used by the regime for ideological purposes. As documented by Firoozeh Kashani-Sabet in Conceiving Citizens: Women and the Politics of Motherhood in Iran, this tactic predates the Islamic Revolution. Fertility rates have consistently been positioned as matters of political concern, both in times of crisis, when additional citizens are needed to sustain and defend the nation, and in times of stability, when population growth must be controlled.

Fertility control extends beyond reproduction policy. It also encompasses issues of socialization and national education. Women are expected not only to bear an adequate number of children but also to raise them as model citizens. As Kashani-Sabet explains in her concept of “patriotic womanhood,” women are tasked with instilling national identity in the next generation, through instruction, discipline, and personal example, and according to the expectations of the state, the regime, and society.3Firoozeh Kashani-Sabet, Conceiving Citizens. Women and the Politics of Motherhood in Iran (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011), 142.

Within the ideological framework of the Islamic Republic, “giving birth and raising children for the Islamic Iran was the primary duty of every Iranian woman in order to support their vanguard anti-imperialist government.”4Firoozeh Farvardin, “Reproductive Politics in Iran: State, Family, and Women’s Practices in Postrevolutionary Iran,” Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies 41, no. 2 (2020): 32. This responsibility was especially emphasized during the foundational years of the Islamic Republic and the Iran-Iraq War, both of which were framed as periods of national crisis requiring population expansion to defend and establish the regime.

Figure 3: Sipīdah typing, accompanied by her mother. Still from M for Mother (Mīm misl-i mādar), directed by Rasūl Mullāqulīpūr, 2006.

Nevertheless, women challenge these archetypes and make autonomous decisions by working, studying, and entering public spaces to assert themselves as individuals. However, the stagnant regime makes it almost impossible for them to access positions of power, aside from the relatively easier path of promoting of men into such roles.

In almost every society, womanhood or the idea of woman is governed by the mandate of motherhood. Women are permitted to fail in fulfilling this role only in extraordinary situations, and even then, only as a contingency, often requiring some form of compensation for the failure. Those women who do conform to the mandate, whether by choice or imposition, are allowed to take on other roles only as secondary activities and only once reproductive labor has been adequately addressed.

Women around the globe are expected to manage domestic responsibilities, including household duties, family care, child-rearing, social obligations, and personal matters. Meanwhile, men are typically tasked with business, employment, civic engagement, and public affairs.5ʿAllāmah Muhammad Husayn Ṭabātabā’ī, Women in Islam (Light of Islam Books, 2017), 39. As expressed by Elaheh Koolaee “each society expects women and men to play their gender roles and to act according to behavioral patterns or characteristics that seem appropriate to them and fulfill their commitments.”6Elaheh Koolaee, “The Impact of Iran-Iraq War on Social Roles of Iranian Women,” Middle East Critique 23, no. 3 (2014): 285. While gender roles are a shared phenomenon across societies, their specific features vary according to the historical circumstances and societal needs, and these details evolve over time. In post-revolutionary and post-war Iran, official sources and individuals in positions of power have expressed support for maintaining this framework, and many have used their authority to reinforce it. A notable example is the Supreme Leader, who “views women’s issues through a very specific lens that focuses on motherhood, modesty, and the afterlife. He considers everything through the prism of God and God’s reward system for ‘good deeds.’”7Mateo Mohammmad Farzaneh, Iranian Women and Gender in the Iran-Iraq War (New York, Syracuse University Press, 2021), 355.

Figure 4: Sipīdah welcoming Suhayl at home. Still from M for Mother (Mīm misl-i mādar), directed by Rasūl Mullāqulīpūr, 2006.

Access to education and other basic rights are often justified as a means to enhance women’s capacity to educate their children. According to one perspective, “educated mothers not only would ensure the nation’s prosperity through their role as educators of children but also would create families in which loving interaction, pleasant exchanges, helpful kindness, good housekeeping, and religiosity would reign.”8Afsaneh Najmabadi, Women with mustaches and men without beards: gender and sexual anxieties of Iranian Modernity (Berkley, University of California Press, 2005), 189. It is important to note that this perspective is supported by curriculum tailored specifically for women’s education. Within this framework, women are not taught to think freely or to produce knowledge, but rather to be well-prepared for household tasks and for reproducing the appropriate cultural and religious traditions.

The official ideology concerning the role of women in Iran has always prioritized religious obligations that position women as the foundation of the family. They are viewed not only as educators and providers, but also as bearers and transmitters of honor, proper behavior, appropriate knowledge, and the social limits expected of each family member. All of this is accompanied by continual reminders of the roles each person is expected to fulfill. First-born children have different responsibilities and decision-making authority than the second or third-born children, and boys and girls are assigned widely divergent expectations. It becomes the mother’s duty to ensure that these obligations are clearly communicated and fulfilled.

Women are regarded the repositories of the honor and values of the family, and by extension, of society and the nation. Therefore, the nation begins in the wombs of women. Mothers are responsible for imparting ideological, social, and political tools to the next generation so that they may develop in society and contribute to the development of the nation itself. Women are considered as the mothers of the nation because they are responsible for both the bearing and education of future citizens, those men and women who will reproduce and strengthen the system.

The family is considered the fundamental unit of society, and women, as mothers of the nation, occupy a central role within it. Consequently, the state invests significant effort in controlling women and shaping the public and official conception of womanhood. This control is aimed at ensuring that the next generation will preserve the existing system and perpetuate the regime. This is one of the reasons—perhaps the main reason—why women are expected to sacrifice themselves on behave of the nation, which is seen as a higher cause.

Figure 5: Sipīdah hearing the heartbeat of the baby in her womb. Still from M for Mother (Mīm misl-i mādar), directed by Rasūl Mullāqulīpūr, 2006.

To fulfill this objective, the Islamic Republic of Iran has made considerable efforts to shape, reshape, reinforce, and solidify the official idea of womanhood. These efforts are also aimed at limiting women’s opportunities in the public sphere, as “all laws, regulations, and their corresponding politics must be in the direction of facilitating the establishment of the family, the protection of its sanctity, and the maintenance of its relations based on Islamic law and ethics.”9Firoozeh Farvardin & Nader Talebi “(Un)familiar familialism: the recent shift in family politics in Iran,” Third World Quarterly (2024): 6. On one hand, the efforts serve as constant reminders to women of what they are expected to be. On the other, the regime imposes numerous laws to punish any deviation from this prescribed model.

Placing the family at the center of the national identity and defining nationalism through the material role of women represents a direct intervention of the regime into private spaces and individual choices. This constitutes the politicization of everyday life and a demonstration of the Islamic Republic’s power to control even the bodies of the women, not only through hijab policies, but also by restricting their ability to engage in anything beyond motherhood and domestic labor. As Firoozeh Farvardin noted, a “recent shift in reproductive policies eventually pushes more women back into families and care work, defeminizing the labor market while reinforcing the informal sector and family work units, which are mainly female based.”10Firoozeh Farvardin, “Reproductive Politics in Iran: State, Family, and Women’s Practices in Postrevolutionary Iran,” Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies 41, no. 2 (2020): 36. Pronatalist ideology not only manifests in policies encouraging increased fertility rates, but also in the restriction of women’s participation in the labor market.

Being the “mothers of the nation” is not only limited to bearing and raising children. It extends to society as a whole, particularly to the men around them. Women are expected to care for, nurture, serve, and “mother” all those in need. A significant example of this expanded maternal responsibility can be found in the charity organizations that supported vulnerable populations, particularly those considered peripheral to the regime’s vision of ideal society. These organizations were among the first avenues through which woman organized and participated in public life, exercising agency and engaging in political activity. In the 1980s and 1990s, charitable work was the primary means through which women were publicly active, and such organizations are still expected to be managed predominantly by women.

Figure 6: Maryam pulling Rizā’s stretcher. Still from The Survivors (Nijāt-yāftagān), directed by Rasūl Mullāqulīpūr, 1996.

Two Figures

In the case of the Islamic Republic of Iran, the singular ideal woman is Fatīmah al-Zahrā, who is not only the mother of her children (Hasan, Husayn and Zaynab Kubrā ⸺Second and Third Imams, and the other women analyzed in this text), figures of great significance in the history of religion, but also the caretaker of her father (the Prophet of Islam) following the death of Khadījah (her mother). Women are thus obligated to provide care and service both to society and to all family members. In exceptional circumstances, such as war, the figure of Zaynab is invoked as an ideal. She endured extraordinary situations, confronting corrupt governors and even religious leaders who distorted the community’s path. Zaynab was vocal in defending justice and in occupying public space to do so.

The ideological significance of Fatīmah and Zaynab predates both the Revolution and the War, although the latter event marked the intensification of references to these figures and the shaping of the ideal woman. The most prominent and frequently cited effort to remind Iranian women that external role models are unnecessary, given the presence of these exemplary and relatable Muslim women, especially Fatīmah, is ‛Alī Sharī‛atī’s Fatīmah Fatīmah ast (Fatīmah is Fatīmah). The text not only outlines ideals but also explains the expectations placed upon the good Iranian women.

Conversely, references to Zaynab are contextual, linked to the reasons for her prominence in Shi’i Islam. Her actions are recognized as extraordinary and tied to specific historical events. Zaynab has maintained a continuous presence in Shi’i Muslim communities as part of a revered group of transcendent people. As a passive subject, she is the Prophet’s family member who was present at Karbala [Iraqi city known for the battle where Husayn and his 72 companions were assassinated by Umayyad soldiers]—facts that were not her decisions nor acts. As an active subject, however, she warned of incoming soldiers, confronted Yazīd (second Umayyad caliph), defended both her family and the community. She born into importance and chose to exercise her power.

Figure 7: Maryam stopping ‛Abdalrahmān from leaving. Still from The Survivors (Nijāt-yāftagān), directed by Rasūl Mullāqulīpūr, 1996.

Their actions must be understood as consequences of their contexts. Fatīmah was primarily a nursing woman who became vocal only in response to the unjust treatment of her husband, Imam ‛Alī, by the heads of the religious community.11According to Shi’i Islam, ‛Alī should have been the caliph. However, after the Prophet’s death, the political and religious leaders of the community appointed another individual. Her husband was alive and able to speak for himself. Zaynab was vocal because she was the surviving figure. The circumstances were such that she became the spokeswoman of the community, and she proved herself worthy of her family’s legacy. Both were devout women who adhered to religious law and were constrained by their inherent gender roles, yet one took on the responsibility of organizing the community while the other focused on nurturing and caring for it.12Shirin Haghgou, “Archiving War: Iran-Iraq War and the Construction of “Muslim” Women,” (Master’s thesis, University of Toronto, 2014), 34.

Fatīmah is the mother of Zaynab, Hasan and Husayn, the daughter of Muhammad, the wife of ‛Alī and a key member of the founding community. A quintessential mother, she even became, as Sharī‛atī claims, the mother of her father.13‛Alī Sharī‛atī, Fatima is Fatima (IslamicMobility.com, 1971), 137, https://www.islamicmobility.com//pdf/Fatima_is_Fatima.pdf. For this reason, immediately after taking power, Khumaynī changed the date of Mother’s Day to coincide with Fatīmah’s birthday.

Zaynab, on the other hand, is regarded as a courageous figure who cursed her captors in Karbala, accusing them of usurping power after the Prophet’s death and obstructing the creation of a rightful and just Islamic society following the Revelation.14Shirin Haghgou, “Archiving War: Iran-Iraq War and the Construction of “Muslim” Women,” (Master’s thesis, University of Toronto, 2014), 34. The designation of Zaynab’s birthday as Nurses’ Day responds to her suitability as a role model for exceptional times.

The Islamic Republic of Iran has been highly effective in its efforts to encourage and console women through these figures. As Mateo Mohammad Farzaneh notes in Women and Gender in the Iran-Iraq War, women invoke Fatīmah and Zaynab to legitimize their wartime defiance and sacrifice. The propaganda system in Iran recognized early that “the second kind of indirect consequences [of war] are social and they include changes in population, reductions in the level of social services, changes in social movements, the transfer of social responsibilities from one sector to another and declines in various opportunities.”15Elaheh Koolaee, “The Impact of Iran-Iraq War on Social Roles of Iranian Women,” Middle East Critique 23, no. 3 (2014): 277-278. Consequently, the regime used images familiar to the Iranian Shi’i population to manipulate these social changes to fit their conception of nationhood, particularly in their transition from the ideological void of the pre-revolutionary period to a meaningful focus on religious figures.

The distinction between the use of Fatīmah and Zaynab as role models lies in their relevance to official discourse. Since the ceasefire in 1988, mentions of Zaynab in official propaganda have considerably decreased, as a vocal figure organizing the community against injustice is no longer deemed necessary. Instead, the regime now requires obedient women who accept their fate and nurture the nation. As Moallem states, “soon after the revolution, Zeinab was domesticated and marginalized,”16Minoo Moallem, Between Warrior Brother and Veiled Sister. Islamic fundamentalism and the politics of patriarchy in Iran (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005), 93. The Islamic Republic now requires women to remain in the domestic space, allowing men to serve as the public heads of families and to manage all resources.

Figure 8: Sipīdah dreaming of holding a baby during the chemical weapons attack. Still from M for Mother (Mīm misl-i mādar), directed by Rasūl Mullāqulīpūr, 2006.

These figures are not new. Fatīmah and Zaynab have been integral of Shi’i ideology since its inception. However, their prominence during the Sacred Defense [name given by the Iranian regime to the Iran-Iraq War] and its aftermath proved beneficial to the regime by providing role models and consolation to women experiencing martyrdom in an indirect form.

Fatīmah

Fatīmah Zahrā was the daughter of the Prophet Muhammad and Khadījah. After the death of her mother, she became the closest person to her father and played a key role in the formation of Islam and the Muslim community (ummah). As Candace Mixon notes, “Fatima is so highly regarded especially in Twelver Shi’ism because it is no less than the bloodline to the Prophet Muhammad that is preserved through Fatima.”17Candace Mixon, Mother of her father: Devotion to Fatima al-Zahra in contemporary Iran (North Carolina: University of North Carolina, 2019), 9. She was the mother of the second and third Imams, the wife of the first Imam and, as mentioned, the daughter of the Prophet. Thus, she is quintessential to the People of the House (Ahl al-Bayt) because her sons, Hasan and Husayn, were the only surviving male descendants of the Prophet. This makes Fatīmah the “mother of the Imamate,” as she is the link between the Prophet and the Imams.

The Shi’i tradition presents her life as an example of behavior for all Muslims, but especially for women. She consistently served, cared for, nursed, and accompanied her father. She was faithful to the Revelation, followed the Prophet, opposed injustice, and was part of the community, all without neglecting her domestic duties. Her development in the public sphere was always dependent on its development in the private sphere.

Fatīmah was a role model because she unintentionally raised a martyr who died defending Islam. Although she was unaware of her son’s destiny, she prepared him to be capable of sacrifice and martyrdom. For this reason, clerical leaders launched campaigns to honor the role of mothers in raising children ready to sacrifice themselves in the name of religion and nation, with Fatīmah’s figure serving as the primary referent and inspiration.

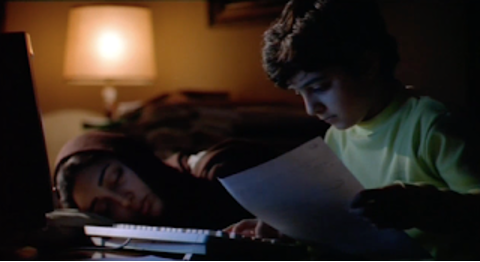

Figure 9: Sa‛īd finishing his mother’s work at night. Still from M for Mother (Mīm misl-i mādar), directed by Rasūl Mullāqulīpūr, 2006.

In summary, Fatīmah’s tireless reproductive labor is generally exalted alongside with her dedication to religious mandates, regardless of the social or economic limitations imposed on women. In addition, she was the spouse of the opponent of those who claimed the political power and religious authority of the Prophet’s heirs. Fatīmah, as Sharī‛atī frequently emphasized, was the ideal woman and example, representing the best qualities a woman can embody. She was the model of a mother, a daughter, a wife, and a pious, modest, and obedient Muslim.

Sharī‛atī describes her as follows:

She is a symbol in all the various dimensions of being a woman.

The symbol of a daughter when facing her father.

The symbol of a wife when facing her husband.

The symbol of a mother when facing her children.18‛Alī Sharī‛atī, Fatima is Fatima (IslamicMobility.com, 1971), 182-183, https://www.islamicmobility.com//pdf/Fatima_is_Fatima.pdf.

Fatīmah is praised not only for being part of the Prophet’s family and the bearer of leaders and interpreters of the Revelation, but also for her daily actions. It is not a specific act that grants her this special place in the memory of the religion, but rather her continuous adherence to religious, political, and social rules. In the context of war, “clerical leaders praised and exalted mothers and launched intensive campaigns to honor women’s role in nurturing Shi’i children, reminiscent of Fatemeh’s unfaltering devotion to her sons, in particular Emams Hussein and Hasan.”19Hamideh Sedghi, Women and Politics in Iran: Veiling, Unveiling and Reveiling (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 93. Fatīmah remains a recurrent role model, but in exceptional times, she is the mother who taught her children that Islam and the Muslim community are more important than individual missions.

Fatīmah was the woman Islam wanted her to be, as Sharī‛atī stated and the Islamic Republic of Iran reproduces. This repeated invocation of her figure can be interpreted as a continuous effort to shape and reshape the idea of womanhood, since her figure epitomizes the life goals a woman is expected to pursue.

Zaynab

The memory of Zaynab’s life centers on her significance after the Battle of Karbala. Her prominence in Islamic history is attributed to her bravery and the pivotal role she played in organizing the community after the assassination of her brother. Although Zaynab’s life is integral to the Shi’i memory, it is important to note that this memory has been predominantly narrated by men. It is not her own voice that recounts the events, but rather the interpretations and narratives of male figures surrounding her.

Figure 10: Maryam and Rizā crossing a field of war. Still from The Survivors (Nijāt-yāftagān), directed by Rasūl Mullāqulīpūr, 1996.

Nonetheless, Zaynab is remembered as a courageous and powerful woman who confronted the unjust governor responsible for the death of her family and the suffering of the community. The significance of the speech in the court of Yazīd lies not only in its content but also in the fact that it was delivered by a woman against a powerful male authority. It is essential to acknowledge that her authority was not derived from an ordinary position; she was the granddaughter of the Prophet Muhammad. However, given the societal perception of women’s inferiority, her boldness is considered even more remarkable. As Nicole Correri affirms, her hagiography is noteworthy for its portrayal of a strong, vocal, and authoritative female figure.20Nicole Correri, “Reconciling Zaynab: Constructions of Femininity in Shī’ī Online English-Language Majālis,” (Master’s thesis, Hartford Seminary, 2018), 1-2. This representation has the potential to shape cultural constructions of female power and leadership, particularly in the contexts of trauma and tragedy. Still, such portrayals are often filtered through the male gaze. Zaynab is largely seen through male-authored narratives and interpretations.

Her most renowned act is the speech that preserved the memory of Karbala. Without Zaynab, the remembrance of this event would have been significantly altered or potentially lost. Even ‛Alī Khāmanah’ī emphasized this point, stating, “Without Zainab Kubra (peace be upon her), that historical event called ʿĀshūrā would not have remained [in the memory of the people].”21Ali Khamenei, The Political and Striving life of Lady Zainab, trans. S. Ranjbar, ed. A. Rezwani (Mashhad, 2017), 12-13. Her actions ensured her place in Islamic history, not solely because of her familial ties to the Prophet, but also because of her own contributions. Karbala elevated her from being merely the Prophet’s granddaughter to a key figure in defending his spiritual heritage.22Ali Khamenei, The Political and Striving life of Lady Zainab, trans. S. Ranjbar, ed. A. Rezwani (Mashhad, 2017), 11. She became the companion of a martyr, the guardian of memory, the mourner, and the voice that carried the events forward. As Khāmanah’ī, the current Supreme Leader of the Islamic Republic, affirms, “The value and greatness of Zainab Kubrā (peace be upon her) is because of her great humanitarian and Islamic stance and movement. Her work, her decision, and her type of movement endued her this greatness.”23Ali Khamenei, The Political and Striving life of Lady Zainab, trans. S. Ranjbar, ed. A. Rezwani (Mashhad, 2017), 11.

Figure 11: Sipīdah looking angrily at Suhayl. Still from M for Mother (Mīm misl-i mādar), directed by Rasūl Mullāqulīpūr, 2006.

As a result of her actions, Zaynab is regarded as a model of courage and a defender of truth and justice. Her story was mobilized during the Iranian Revolution and the Iran–Iraq War as a political symbol to justify and encourage women’s participation. “Zeinab became a political symbol to encourage women’s participation in the events of the revolution [and war]. Zeinab’s story legitimized the participation of masses of young women in the events of the revolution [and war] and prevented their families from forbidding them from taking revolutionary action.”24Minoo Moallem, Between Warrior Brother and Veiled Sister. Islamic fundamentalism and the politics of patriarchy in Iran (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005), 93. The very existence of a sanctified female figure on the front lines in one of Shi’i Islam’s most significant historical moments validated and inspired the involvement of young Iranian women in both the revolution and the war. However, it is important to mention that depictions of Zaynab do not portray her solely as a rebel against tyranny; she is also portrayed as a spokeswoman for justice, a unifier of the oppressed, resilient in the face of loss, yet consistently conforming to her expected gender role as a woman.

This final aspect is particularly significant, as it contributes to the construction of Zaynab as a role model and an ideal figure for emulation. She is portrayed as an exceptional woman who conducted herself with propriety even in extraordinary circumstances. However, despite Zaynab’s strong character, she remains constrained by gender expectations and is presumed to have fulfilled reproductive responsibilities, such as caring for her child even in extremely challenging conditions, and directing her defiance solely toward male enemies, rather than leaders within her own community. This gendered framing is noted by Khāmanah’ī, who remarked that “she was a woman, a woman who was separated from her husband and family for a mission and it was also for this reason that she took her young children along with herself.”25Ali Khamenei, The Political and Striving life of Lady Zainab, trans. S. Ranjbar, ed. A. Rezwani (Mashhad, 2017), 12. This reflects the expectation that, even while defending the community and the revelation on the front lines, Zaynab was still responsible for her children and emotionally burdened by separation from her husband. Despite the recognition of her powerful speech, she is often remembered primarily as the grieving sister, as Sharī‛atī notes, and her leadership is acknowledged only in the absence of male figures, as “She continues the movement at a time when all of the heroes of the revolution are dead and the breath of the forerunners of Islam has ceased.”26‛Alī Sharī‛atī, Fatima is Fatima (IslamicMobility.com, 1971), 32, https://www.islamicmobility.com//pdf/Fatima_is_Fatima.pdf.

Zaynab’s leadership and resistance to the illegitimate authority positioned her as one of the most important symbolic figures during the Revolution and the Sacred Defense. However, he example was primarily invoked during periods of crisis, when such exceptional forms of female leadership were temporarily permissible. References to Zaynab were frequent because she represented the idea Muslim woman, who was vocal against injustice and tyranny, yet faithful, modest, and religious.

As the Prophet’s granddaughter, Zaynab belongs to a sphere of idealized women that serve to construct a particular narrative of feminine conservatism and patriarchal virtue. She is a figure who can be cited for her courage and resistance, while simultaneously representing submission, piety, and modesty. Her presence in religious history has been instrumentalized to justify women’s participation in revolutionary and wartime activities. This narrative was also used to persuade conservative families to support female involvement, and in some cases, families actively encouraged their daughter to support the war effort, either on the front lines or in supportive roles.

Figure 12: Maryam walking through the former frontlines. Still from The Survivors (Nijāt-yāftagān), directed by Rasūl Mullāqulīpūr, 1996.

At the same time, Zaynab’s image was used to inspire women to engage actively in the defense of their community, rather than waiting for others to act on their behalf. However, this inspiration was always framed within the limits of accepted gender roles. Her example served as a discursive tool to suggest an illusion of freedom and space for women in public life, portraying their participation in sociopolitical struggles as validated, while still subordinated to the larger patriarchal order. Like Husayn, Zaynab’s example was also used to encourage acceptance of martyrdom, positioning death in defense of belief as noble and privileged outcome.

Women’s indirect participation in the Iran-Iraq War responded to calls from Khumaynī and other revolutionary figures, who urged women to encourage their male relatives to join the front. They were asked to emulate Zaynab, who came to represent a symbolic encourager of martyrdom and a guardian of the community. At the beginning of the war, women’s involvement was largely confined to supporting male combatants and managing domestic responsibilities to allow men to focus entirely on the battlefield. Women were expected to send their relatives to war, paralleling Zaynab’s role in the martyrdom of Husayn and her sons. This comparison aimed to affirm that only the most devout Muslims are granted the honor of sacrifice, thus rendering martyrdom a beautiful and exalted concept.

Zaynab’s participation extended beyond her speech. She also fulfilled numerous reproductive tasks. She became a model for the ideal wartime woman: a traditional caregiver responsible for domestic duties such as cleaning, cooking, nursing, and emotional support, not only for children but for people of all ages. Her presence outside the domestic sphere was justified only by the exceptional context of war and revolution.

Consequently, following the ceasefire, Zaynab’s public image was domesticated and relegated to symbolic association with nursing. While society tends to revere nurses, this appreciation is generally confined to emergencies, not to everyday life. In a similar way, Zaynab was celebrated during wartime but was once again marginalized in times of peace.

Figure 13: Maryam looking at a high hill. Still from The Survivors (Nijāt-yāftagān), directed by Rasūl Mullāqulīpūr, 1996.

War Cinema

Every war leaves profound effects on the population; all members of society suffer its consequences. Wars are not limited to bombs, frontlines, soldiers. They also involve wounds, aftermaths, absences, grief, and, importantly, discourse and propaganda.

During the Iran-Iraq War, the Iranian state used the violent context as a means of fostering social cohesion. The focus on external threats, posed by an enemy portrayed as intent on destroying the country, the nation, the Revolution, and everything deemed valuable by the Islamic Republic, served to reinforce ideological constructions of masculinity and femininity in accordance with the regime’s political vision of the nation.

Cinema was one of the media tools employed by the regime during the war to convey representations of the battlefield and to articulate expectations of the population. These expectations extended beyond formal citizenship, as participation was not restricted to adult men; rather, it included all individuals who were physically capable and ideologically willing to contribute directly to the war effort or to support it from adjacent spaces. Contrary to retrospective narratives that focus solely on combat, wartime cinema emphasized the broader calls to participation, including support roles and labor near the frontlines.

Figure 14: Sipīdah showing severe symptoms of mustard gas exposure. Still from M for Mother (Mīm misl-i mādar), directed by Rasūl Mullāqulīpūr, 2006.

In the post-war period, the memory of the conflict has been mobilized to justify the continuation of exceptional conditions. Commemoration is not limited to past events but is also used to maintain the sense of persistent external threat. In the cinematic domain, films such as Bodyguard (Bādīgārd, 2016) and Times of Damascus (Bih vaqt-i Shām, 2018), both by Ibrāhīm Hātamīkiyā, attempt to integrate current official concerns within the symbolic framework of the war, reinforcing the idea that war is war, regardless of who the adversaries are.

While the inclusion of women in wartime propaganda began early in the war, their presence in cinema followed a different trajectory. The first films to feature women in main roles, where they possess a discernible voice both diegetically and extra-diegetically, emerged only after the ceasefire. These initial portrayals were crafted by male filmmakers, including The Survivors and Hīvā (1998) by Mullāqulīpūr, as well as Ibrāhīm Hātamīkiyā’s The Scent of Joseph’s Shirt (Bū-yi pīrāhan-i Yūsuf, 1995) and Minoo Watchtower (Burj-i Mīnū, 1996). Prior to these portrayals, women were largely absent from diegetic narratives during the eight years of active conflict. When they did appear, it was solely as supportive characters, included only to enable the development of male protagonists.

This male-dominated construction of female characters is evident in their narrative function. These women exist primarily in the service to men, not only performing domestic tasks such as cleaning, cooking, and serving food, but also resolving all matters in the domestic sphere so that men may fully engage in the public domain. Their existence is justified solely by their capacity to support the male protagonists. Similarly, in religious discourse, female figures are often remembered only through their proximity to male icons such as the Prophet, the Imams or other notable men.

Figure 15: Maryam pulling Rizā through the long way out of the field. Still from The Survivors (Nijāt-yāftagān), directed by Rasūl Mullāqulīpūr, 1996.

The representation of idealized figures is not merely a reproduction of religious or ideological texts. In cinema, these ideals must be translated into the context of everyday life. The incorporation of such ideals into cinematic narratives requires adaptation, and this process is crucial in revealing how the regime shapes notions of citizenship through cultural production. Tracing these cinematic efforts can provide critical insights into the ideological frameworks that govern film production in the Islamic Republic.

These veiled references serve to stereotype ideals with the intention of encouraging spectators to reproduce them in their own lives, and to identify and glorify both everyday and exceptional actions that align with these ideals. Accordingly, propaganda imagery and other representations aimed at shaping society depict stereotypical versions of these ideals. When such stereotypes and referents are used by a regime to mold its conception of citizenship, the effort involves the obligation to serve the nation. The underlying mission is to remind individuals that they are expected fulfill both private and public duties in service of the country. This dynamic is evident in the genre of war films in Iran. The official discourse surrounding the Sacred Defense constructs portrayals of ideal men and women who embody propriety while also serving as exemplary citizens in the public sphere.

Figure 16: Maryam looking at the chaos after the landmine explosion. Still from The Survivors (Nijāt-yāftagān), directed by Rasūl Mullāqulīpūr, 1996.

Films

This section analyzes two films by Rasūl Mullāqulīpūr to exemplify official efforts to shape the concept of womanhood, while also providing insight into the ideology of the regime and its expectations of women.

The first film, The Survivors (1996), and the second, M for Mother (2006), were released a decade apart. Despite the time difference, both films depict strikingly similar female characters who react to their environments in ways consistent with prevailing gender norms. These characters conform to the stereotypes of “good women” and can be ideologically aligned with figures such as Fatīmah and Zaynab.

In The Survivors, the protagonist Maryam, a nurse, emerges as the temporary leader of a small community. She embodies dignity and compassion, prioritizing the care of others despite fear and her initial reluctance. Though she expresses a desire to quit, her sense of duty and moral responsibility prevails, and she ultimately honors the role she has assumed.

Figure 17: Maryam explaining to Rizā that she is allowed to touch him to administer his medical treatment. Still from The Survivors (Nijāt-yāftagān), directed by Rasūl Mullāqulīpūr, 1996.

The film opens with scenes of retreat from the frontlines and a brief overview of the context: Maryam, fleeing bombings, decides to take with her a wounded war volunteer who cannot escape on his own due to severe, though non-life-threatening, injuries. This decision positions her as a leader, but under very specific and exceptional circumstances.

This situation placed her in the role of leader and illustrates how, when, and where a woman can be a leader: when a man is either dependent or incapable of leading, in contexts of emergency, and when an extraordinary woman demonstrates responsibility and respect. To sum up, the representation of Maryam as a leader in exceptional times is a form of typecasting, presenting the only scenario in which a woman can temporarily occupy a leadership role, as the situation is clearly delimited. Maryam’s leadership is framed as permissible solely under extreme and temporary conditions, reflecting a typecasting of female leadership as conditional and limited. Her role is reminiscent of Zaynab’s temporary leadership in the absence of qualified men. Although Rizā, the injured volunteer, is physically incapacitated and unable to lead, Maryam repeatedly emphasizes her respect for him and asserts her need for his protection. Despite his immobilization due to a back injury, she consistently turns to him in moments of fear, crying out for help. From the outset, she declares her inability to use a weapon, refusing to even touch the Kalashnikov, and begs Rizā to accompany her on the journey.

Once the main characters are established, Mullāqulīpūr introduces additional figures, the most prominent being ‛Abdalrahmān, an Iraqi soldier. Initially, threatening to shoot Maryam and Rizā, he soon seeks medical assistance for his already-deceased comrade. They encounter leads to a theological discussion in which ‛Abdalrahmān claims that only Arabs can be Muslim, based on the Prophet’s Arab identity, and denies Iranians the right to visit Karbala. In response, Rizā delivers an eloquent argument asserting that Islam is a religion grounded in belief, not ethnicity.

Figure 18: ‛Abdalrahmān showing a memory he brought from Karbala. Still from The Survivors (Nijāt-yāftagān), directed by Rasūl Mullāqulīpūr, 1996.

‛Abdalrahmān plays a pivotal role in the narrative, serving as a bridge between Iranians retreating from the war and the Iraqi enemy. He is portrayed not merely as combatant but as a human being with beliefs, while simultaneously depicted as a subject of propaganda and manipulation by his leadership. The film clearly distinguishes between Saddam Hussein, who is positioned as the enemy, and individual Iraqis such as ‛Abdalrahmān. Ultimately, ‛Abdalrahmān sacrifices himself to save Maryam and Rizā, emphasizing the notion that it is not the Iraqi people who are the antagonists, but rather Saddam, who assumes the role of the Yazīd figure. He is presented as the one who initiated aggression and forced both nations into conflict, while the shared Islamic faith is emphasized as the deeper connection between individuals on both sides. Maryam, cognizant of her position as a woman, remains in the background during these interactions, allowing Rizā to manage the situation. She only intervenes when personally offended, while the theological debate remains a conversation between men.

Mullāqulīpūr situates the narrative within a specific historical moment, incorporating the announcement of the ceasefire. This point in time is depicted as ideal for exploring the ethics and behaviors of soldiers and civilians alike, amid an atmosphere of uncertainty. Although the Iranian group is portrayed as wounded and vulnerable, they temporarily include an Iraqi soldier, sharing water and food. However, the broader Iraqi forces ultimately attack, violating the implicit trust established. The Iranians are shown as only acting in self-defense and in accordance with orders, whereas the Iraqis exploit their advantage by launching artillery attacks, thereby violating international agreements.

Figure 19: The group being attacked after the ceasefire. Still from The Survivors (Nijāt-yāftagān), directed by Rasūl Mullāqulīpūr, 1996.

A significant philosophical exchange occurs between Rizā and Maryam after they cross a field strewn with Iraqi corpses and encounter ‛Abdalrahmān for the first time. The discussion centers around fate and purpose. Maryam expresses disillusionment, revealing that she initially pursued medical school to escape marriage and help others, never intending to be on the front lines of war. Meanwhile, Rizā articulates a clear sense of purpose, affirming his willingness to become a martyr in defense of the Islamic Republic. Maryam is portrayed as emotional and conflicted, questioning her presence in such a perilous environment. Rizā, however, remains composed and resolute, suggesting that the rationale behind one’s presence is less important than the fulfillment of one’s duty. He is severely injured and may be unable to walk, but he remains in control of his emotions. This contrast reinforces traditional gender stereotypes, portraying women as emotional and men as rational.

Following the announcement of the ceasefire, the main characters focus their efforts on leaving the front and returning to their cities. At this juncture, Maryam “adopts” a group of injured and weakened Basījīs. Despite their physical impairments, they join Maryam and Rizā, recognizing that Maryam’s ability to walk and her medical expertise render her essential to their survival. Mullāqulīpūr repeatedly emphasizes the diegesis that the Basījīs accept Maryam’s leadership due to her physical capability, while also reinforcing her respect for Rizā’s authority and her willingness to follow his instructions.

Figure 20: Maryam sharing food with ‛Abdalrahmān. Still from The Survivors (Nijāt-yāftagān), directed by Rasūl Mullāqulīpūr, 1996.

Maryam’s medical training is central to her presence at the front and to the respect she receives from the male characters. She is not only a nurse but also represents the ideal of a devout Muslim woman. Her decision to include an Iraqi soldier in the group and provide him with care reflects a commitment to the principles of dignity and the unity of the Muslim community over pride, victory, or nationalist sentiment. Even in the context of war, her role as a caregiver transcends national boundaries. Through her actions, she affirms that moral responsibility and compassion are higher values than victory. Above all, she is portrayed as both a competent healthcare professional and, most importantly, a virtuous Muslim.

At the beginning of their journey, Maryam informs Rizā that she is permitted to touch him due to her professional duties, but not by personal choice. She must even compel him to accept medical treatment after he initially refuses on religious grounds. This seemingly minor plays a crucial role in justifying certain diegetic interactions and highlighting that, while Maryam is a devout Muslim, she is also a highly competent healthcare professional who prioritizes her patients’ well-being over restrictive interpretations of religious norms. Her actions are legitimized by a fatwa that permits female medical practitioners to physically attend to male patients when necessary. This conversation functions to rationalize the presence of female medical staff on the front lines. Even in times of crisis, the public sphere remains male-dominated, and the belief that war is an exclusively male domain persists. Maryam and Zaynab are present not by personal choice, but because the extraordinary circumstances demanded it. Both women rise to these exceptional challenges, performing their roles with remarkable competence. Maryam could have fled at the beginning, thereby relinquishing all responsibility, but instead chooses to stay and care for Rizā. In doing so, she assumes an extraordinary role of caring for others and taking the lead, just as Zaynab confronted Yazīd and defended her family and moral heritage.

Maryam is portrayed as Zaynab in multiple capacities: as a leader, a voice against injustice, a healthcare provider, and a devout Muslim committed to the principles of communal care and protection. Though she never verbalizes her religiosity, her actions reflect a lived embodiment of Islamic conviction. She lives as Zaynab would, through deeds, not declarations.

Figure 21: Maryam gazing at an ambulance and a rocket behind it. Still from The Survivors (Nijāt-yāftagān), directed by Rasūl Mullāqulīpūr, 1996.

In M for Mother, the protagonist Sipīdah is constructed through a set of stereotypes shaped by men and designed to instruct women on ideal behavior. She is portrayed as a nurse during the war who selflessly sacrifices herself for the fighters, defies medical professionals and her own family to pursue motherhood, and continues to serve vulnerable populations through her work. In contrast, the main male character, Suhayl, her husband, embodies moral weakness, poor decision-making, and unethical behavior. He functions as a symbolic representation of the perceived flaws within the Islamic Republic. Neither character represents a realistic individual; rather, both are built upon idealized and reductive clichés. They do not depict a real family but instead serve as embodiments of entrenched cultural binaries of virtue and vice.

Figure 22: Sipīdah playing the violin by her baby’s crib. Still from M for Mother (Mīm misl-i mādar), directed by Rasūl Mullāqulīpūr, 2006.

Sipīdah alternates between the symbolic figures of Fatīmah and Zaynab depending on the sociopolitical context of the nation, not her own individual trajectory. She exists in a state of perpetual exceptionality, which requires her to adapt constantly to idealized models of womanhood. During the war, she aligns with Zaynab, present on the front lines due to the emergency, offering support to the community. In this role, she sacrifices herself by giving her gas mask to a soldier during a chemical attack. In the post-war context, she becomes more closely aligned with Fatīmah, embodying the ideal of the domestic woman. Her role shifts to that of a housewife whose sole aspiration is motherhood.

In peacetime, Sipīdah is depicted as an appropriate wife who functions mainly in the domestic sphere. She waits for her husband to return from work, for his decisions about her life, for doctors to tell her what course of action to take. She is portrayed as a passive subject who waits, accepts, and obeys, submitting to a predetermined fate and relinquishing personal agency. Her character represents a vision of womanhood defined by patience, submission, and obedience.

From the outset, it is evident that Suhayl, Sipīdah’s husband, is portrayed negatively, particularly when he denies her the opportunity to become a paid and potentially successful orchestra musician. His refusal to support her career ambitions is framed as a failure to fulfill his responsibilities as a husband and provider. His most egregious act, however, is his attempt to impose an abortion on Sipīdah, an act interpreted as an effort to interfere with divine will. In defiance of both medical authority and patriarchal control, Sipīdah, evoking the symbolic figure of Zaynab, rejects his demand and continues with the pregnancy. Later, when he returns and convinces her to try an alternative medical method, it results in premature labor, leading to the birth of a child with numerous health complications, both anticipated and unforeseen.

Figure 23: Sipīdah and Suhayl looking at the door of the room where an abortion is taking place. Still from M for Mother (Mīm misl-i mādar), directed by Rasūl Mullāqulīpūr, 2006.

Sipīdah’s confrontation with her husband, who represents the family’s authority, serves as a manifestation of her maternal mandate. She chooses to carry the pregnancy to term despite the doctors’ warnings and the potential risks stemming from her exposure to chemical weapons. Her decision is not based on a rational debate over alternatives but rather on an internalized belief that motherhood constitutes a woman’s ultimate purpose. She does not question this belief but rather accepts and embraces it uncritically. As a result, Sipīdah is depicted as a woman wholly defined by her desire to become a mother, willing to sacrifice all other ambitions or interests. This is exemplified in the scene where she abandons her at-home teaching job to comfort her infant. After waiting for some time, the student quietly leaves, once again leaving Sipīdah without an income. This scene reinforces the prioritization of domestic responsibilities over professional aspirations, a narrative emphasized by ‛Alī Khāmanah’ī and other important figures in the Islamic Republic. Although Sipīdah is compelled to undertake work she dislikes due to Suhayl’s irresponsibility and lack of commitment, exemplified by his refusal to allow her to join the orchestra, she is a still portrayed as a morally superior woman, a figure aligned with Fatīmah. Her virtue lies in her willingness to forgo professional fulfillment to uphold her domestic duties, which are depicted as her primary responsibility.

Mullāqulīpūr includes numerous subtle references to the construction of ideal womanhood. These range from grand gestures, such as refusing an abortion or surrendering the last gas mask during a chemical attack, to more domestic and interpersonal moments. For example, when her son Sa‛īd asks about his father, Sipīdah tells him that his father is “untraceable” rather than revealing the truth—that he chose to abandon them. This seemingly minor falsehood emphasizes the expectation that childbearing and child-rearing are entirely women’s responsibilities. She manages the emotional consequences of another’s decisions without exposing her child to the truth, thus preserving the integrity of the household at her own expense. This pattern continues when she flatly refuses to entertain the romantic interest of her employer, who proposes that she meet his mother and consider marriage. Sipīdah rejects the suggestion outright. Her refusal is not portrayed as a personal choice based on emotional or rational considerations, but rather as further confirmation of her identity: she is, above all else, a devoted mother and only that.

Figure 24: Sipīdah and her mother taking care of baby Sa‛īd. Still from M for Mother (Mīm misl-i mādar), directed by Rasūl Mullāqulīpūr, 2006.

To summarize, motherhood is portrayed as the most important role for a woman, one that must be pursued regardless of circumstances, even if the child may suffer from poor health, lack of quality of life, or the family is facing collapse. Moreover, Sharī‛atī’s notion of Fatīmah as the “mother of her father” is echoed in Sipīdah’s role as the caretaker of her mother. Sipīdah assumes full responsibility for her mother’s well-being: she feeds her, plays music for her, and manages her life. In doing so, she becomes the “mother of her mother,” the ultimate embodiment of maternal duty, performing her role without complaint, fully aware of the burden as a natural responsibility.

In addition to this, Sipīdah fulfills the symbolic role of Fatīmah as the mother of a victim, a jānbāz (disabled war veteran), who is doubly victimized: first by Iraqi chemical weapons, and second by his father. Diegetically, Suhayl represents the embodiment of moral failure and malevolence. Each of his appearances serves to reinforce or deepen the viewer’s negative perception of his character. He abandons Sipīdah in the hospital after she again refuses his demands. This time, his insistence on sending Sa‛īd to a sanatorium due to the complications caused by his premature birth. Despite his repeated neglect of familial duties, Suhayl intermittently reappears, further disrupting their lives. Every time he is reintroduced into the narrative, the consequences are destructive, especially for Sa‛īd, whom Suhayl refuses to acknowledge as his son. He attempts to remove the child from their lives while simultaneously expressing a desire to remarry Sipīdah, claiming he still loves her and considers her the ideal wife. However, he makes it clear that he will not accept Sa‛īd as part of that future. True to her symbolic alignment with Fatīmah, Sipīdah refuses this proposition, even though it means continued economic and social hardship.

Figure 25: Sipīdah rejecting Suhayl’s new proposal. Still from M for Mother (Mīm misl-i mādar), directed by Rasūl Mullāqulīpūr, 2006.

Finally, Mullāqulīpūr presents Sipīdah as a model citizen who serves the nation not only by fulfilling her familial duties but also through her public service. She is a mother of her son, a caregiver to her mother, and a helper to anyone within her reach. Her social contribution extends further, as she teaches music to disabled children. Although she enters the public sphere out of necessity rather than choice, her work is rendered honorable precisely because it is rooted in care and service to others.

In conclusion, Sipīdah is portrayed as the ideal Zaynab in moments that demand action and vocal resistance, yet she embodies Fatīmah for most of the narrative. She fulfills stereotypically feminine duties without complaint or hesitation, fully aligning with the Islamic Republic’s expectations for women. Her moral and symbolic perfection is achieved through her consistent actions and sacrificial choices.

Figure 26. Sipīdah rocking Sa‛īd in her dreams. Still from M for Mother (Mīm misl-i mādar), directed by Rasūl Mullāqulīpūr, 2006.

Conclusion

The representation of women in the official and officialist cinema of the Islamic Republic of Iran closely aligns with the stereotypes propagated by religious discourses, which seek to impose these figures as the sole models for emulation. These idealized figures are sometimes veiled but always present, as the regime consistently capitalizes on opportunities to remind the Iranian population of their expected roles and identities.

It is important to note that after the war ended, the reconstruction of Iran encompassed not only cities and infrastructure but also the rebuilding of ideology and a new collective self-understanding within the global context. Official and officialist films serve as significant vehicles for transmitting and shaping the vision of the “new Iran” as a nation and defining the ideal citizen to inhabit the country, not only as a physical space delineated by borders but also as a spiritual homeland for those who embrace their identity as Iranians and loyal members of the Islamic Republic.

Figure 27: Maryam shouting triumphantly after the ceasefire. Still from The Survivors (Nijāt-yāftagān), directed by Rasūl Mullāqulīpūr, 1996.

Since its inception, the war genre has been an ideal arena for constructing this national ideology, as the war represented an exceptional period during which communal unity and prioritization of internal solidarity against external threats were paramount. The war established conditions favorable to a regime that privileges a select few. In the postwar period, the genre has been instrumental in disseminating key regime messages, as evidenced in the analyzed films. The Survivors was produced shortly after the ceasefire, during a moment of reconstruction and redefinition of enemies, contexts, and social realities; thus, Saddam Hussein is explicitly identified as the enemy, while loyal Iranian citizens seek to avoid further conflict and embody the qualities desired by the nation. In contrast, M for Mother was produced several years later amid state concerns regarding declining fertility rates, which explains the exaltation of motherhood and the film’s implicit call for women to embrace motherhood as life’s primary purpose despite any obstacles.

Finally, it must be emphasized that artists shape not only the images but also the behaviors and ideals that citizens are expected to embody and pursue, depicting exemplary individuals who persistently strive toward sanctification. Consequently, films such as M for Mother and The Survivors play a crucial role in maintaining and legitimizing the regime, as characters like Sipīdah and Maryam represent the model women that the Islamic Republic seeks to promote.

Figure 28: Sipīdah saying “M for mother” just before dying. Still from M for Mother (Mīm misl-i mādar), directed by Rasūl Mullāqulīpūr, 2006.

Cite this article

This article critically examines the symbolic use of the figures of Fatīmah and Zaynab, daughter and granddaughter of Muhammad, Prophet of Islam, within the cinematic discourse of the Islamic Republic of Iran, particularly in how these archetypes shape and reinforce ideals of womanhood. The war genre, often serving as a platform for state-sponsored propaganda, frequently invokes these revered figures to promote ideals of women aligned with religious and cultural narratives.

Through an analysis of Rasūl Mullāqulīpūr’s filmography, including M for Mother (Mīm misl-i mādar, 2006) and The Survivors (Nijāt-yāftagān, 1996), this study explores how female characters are constructed in accordance with the archetypes of Fatīmah and Zaynab. These films present women who embody the characteristics of Fatīmah in their daily lives—modesty, devotion, and maternal care—and transform into the Zaynab archetype in moments of national crisis, embodying resistance, sacrifice, and courage. This duality of representation demonstrates the complex interplay between gender, ideology, and political narratives in the cinematic portrayal of women in post-revolutionary Iran.

Key words: War, cinema, women, Fatīmah, Zaynab, Mullāqulīpūr