Speaking through Pain: Feminist Testimony and Diasporic Resistance in Born in Evin

“When you are near, the winds carry away my loneliness and

winter flowers begin to bloom in my heart.”1From the song “Gole Yakh” by Kūrush Yaghmāyī, translated by Tania Ahmadi.

Introduction

Born in Evin2Born in Evin, directed by Maryam Zaree (Germany: Tondowski Films, 2019), documentary film. unfolds as a poignant confluence of personal memoir and political inquiry, following filmmaker Maryam Zaree’s courageous pursuit to uncover the concealed truths surrounding her birth within the walls of Iran’s infamous political prison, Ivīn Prison. Born in 1985, during Ayatollah Khumaynī’s regime, Zaree entered the world in the shadow of state violence and repression. The details of her early life remain shrouded in secrecy. As an infant she was separated from her imprisoned mother and sent to live with her grandparents; years later, following her mother’s release, the two of them fled to Germany in search of safety and freedom. It was not until the age of twelve that Zaree discovered the truth about her birthplace. Now, at thirty-five, she embarks on a deeply personal and politically charged journey to confront the silence that has long defined her life. In doing so, she not only engages with the emotional legacy of her family’s trauma, but also questions the broader historical amnesia surrounding Iran’s political prisoners. By returning to the literal and symbolic walls of the prison that once shaped her family’s fate, Zaree transforms her search for answers into an act of resistance, challenging both personal denial and collective forgetting. Her journey becomes a remarkable effort to reclaim agency, restore memory, and illuminate a suppressed chapter of history, the effects of which continue to echo across generations.

Figure 1: Zaree as a child in a home video recorded in 1991. Still from Born in Evin, directed by Maryam Zaree, 2019.

This urgent act of remembrance evokes the words of political activist Angela Davis, who writes, “pernicious examples of state violence that produce (and reproduce) collective trauma also generate demands for memorialization that can imprint the memory of trauma on the historical record.”3Angela Davis, foreword to Voices of a Massacre: Untold Stories of Life and Death in Iran, ed. Nasser Mohajer (New York: Oneworld Publications, 2020), xii. Davis emphasizes the importance of remembering state-sanctioned atrocities—not only to honor the lives that were lost or irrevocably altered, but also to support those who continue to resist oppression. As history has shown, in the aftermath of atrocities there have been numerous innovative efforts to memorialize the victims whose lives were systematically, ruthlessly, and often covertly extinguished by the Islamic Republic. What must be remembered is that history, despite its wrenching pain, cannot be unlived. Yet with courage, one can confront it—pushing against forced silences and boundaries to uncover the truth. In this context, Born in Evin stands as a powerful act of unveiling, transforming personal inquiry into a collective confrontation of suppressed history.

In this essay, I examine two key ways in which Born in Evin dismantles power hierarchies, state violence, and political persecution. First, by breaking three decades of silence and situating her personal narrative within the broader landscape of state-sponsored repression, Zaree destabilizes the conventional boundary between private memory and public history. Her testimony operates as a profound act of resistance, directly confronting the systematic and gendered violence perpetrated by the Islamic Republic of Iran. In reclaiming this silenced past, Zaree not only asserts her individual voice but also organizes a collective gesture of solidarity with others whose experiences have been marginalized or erased. This intervention powerfully evokes the feminist axiom that “the personal is political,” a slogan popularized during the second-wave feminist movement of the late 1960s to emphasize the entanglement of individual experiences with broader structures of power. Zaree’s act of remembrance thus moves beyond personal catharsis, contributing to a collective oral history that transforms trauma into political agency.

Second, Zaree calls attention to and denounces the roles she has played as an actress within contemporary German cinema,4Maryam Zaree has appeared in numerous German cinema and television productions, including Christian Petzold’s Transit (2018) and Undine (2020), Nora Fingscheidt’s Systemsprenger (System Crasher, 2019), as well as the series Doppelhaushälfte (2021–present) and Legal Affairs (2021). Born in Evin (2019) is her directorial debut in documentary filmmaking. specifically those that reduce refugee identities to simplistic tropes of victimhood and suffering, thereby asserting narrative agency and reclaiming control over how diasporic identities are represented on screen. Her directorial debut functions as a feminist, political intervention, disrupting dominant narrative conventions, deconstructing representational hierarchies, and resisting the cultural politics of erasure. Drawing on Hamid Naficy’s concept of accented cinema,5Hamid Naficy, An Accented Cinema: Exilic and Diasporic Filmmaking (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2001). which encompasses the work of exilic, diasporic, and postcolonial filmmakers negotiating hybrid identities, Zaree’s film inhabits a space of liminality—a condition of in-betweenness that destabilizes fixed boundaries between self and other. The film reimagines identity beyond imposed binaries, contributing meaningfully to ongoing discourses on agency, memory, and the ethics of representation. Through this dual intervention—both cinematic and autobiographical—Born in Evin not only unsettles entrenched structures of cultural power but also provides a new framework for historical reckoning and transnational storytelling.

The Personal is Political: Memory as Resistance

The film opens with a home video in which a young Zaree briefly recounts the story of her life. The year is 1991; she is in the second grade, and her mother is pursuing a master’s degree in psychology. It is revealed that the footage is meant for her father. His whereabouts remain unknown, a mystery that casts a long shadow and immediately captures the audience’s attention. In the following scene, we see Zaree at age 35, parachuting. Upon landing in a barren farm field, Zaree becomes entangled in the equipment. As she struggles to free herself, a voiceover reveals that her father too was imprisoned in Ivīn. It’s a clever cinematic image that draws a powerful parallel between her current struggle and his emotional and political confinement. After a brief pause, she adds, “I also know I was born in Evin, and that’s basically everything I know.” The camera then cuts to a long shot of the desolate landscape—vast, empty, and uncertain. Zaree enters from the right side of the frame, literally stepping into this unknown space to chart her own path. At this moment her narration grows resolute. She states that she is no longer willing to hide behind fragmented memories and unanswered questions—she is ready to confront the past and uncover the truth. Here, the visual and narrative elements converge powerfully, signaling the beginning of a deeply personal and political journey of reclamation and self-discovery.

Figure 2: Zaree is entangled in parachuting equipment in a barren field. Still from Born in Evin, directed by Maryam Zaree, 2019.

The film employs silence, ellipses, and non-linear storytelling to reflect the fragmented and often elusive nature of memory. Through a blend of home videos, archival footage, and old photographs, it constructs a partial yet evocative historical record of Zaree’s family. Accompanied by her voice-over narration, these materials reveal that her parents were vocal critics of the Pahlavī monarchy. Despite certain civil liberties—such as freedom of dress—they viewed the regime as deeply unequal, where a privileged minority lived in luxury while the majority endured widespread poverty. Like many in their generation, her parents were revolutionaries, influenced by Marxist ideology and Western counterculture, including the music of John Lennon. The film shifts rhythmically between archival footage and contemporary narration, presenting an oral history of Iran in the 1970s, with a particular focus on the fervor surrounding the 1979 Revolution. Scenes of mass demonstrations, chaotic streets, and the burning of the Shah’s image portray the collapse of the monarchy. In the end, the hopeful vision of the just and egalitarian society that Zaree’s parents fought for quickly unravels. With the rise of the Islamic Republic, the film depicts the rapid transformation of Iranian society. Women are now subjected to compulsory hijab laws, and tens of thousands of political dissidents face persecution, imprisonment, torture, and execution. In 1983, while Zaree was still in utero, her parents were arrested. What followed remains largely unknown to her. This absence—marked by a prolonged narrative pause—represents the central mystery in both the family’s history and the documentary itself. It is the missing piece that Zaree seeks to uncover, not only to understand her origins but to confront a silenced past that continues to shape the present.

Zaree’s quest to uncover the truth about her life unfolds in three distinct phases. The first begins when she initiates a conversation with her mother, asking about the circumstances of her birth in Ivīn Prison. As film critic Nuzhat Bādī writes, “Spanning two generations of imprisoned mothers and their children, [the film] tells a story of resistance that begins with the mothers and is carried on by their daughters.”6Nuzhat Bādī, “Rāvī-i yak sarguzasht-i jam‘ī,” [Narrator of a Collective History],” Cahiers du féminisme, accessed October 2, 2025, https://cahiersdufeminisme.com/%d8%b1%d8%a7%d9%88%db%8c-%db%8c%da%a9-%d8%b3%d8%b1%da%af%d8%b0%d8%b4%d8%aa-%d8%ac%d9%85%d8%b9%db%8c/. [translated by Tania Ahmadi]. This intergenerational silence, however, is not easily broken. At first, Zaree’s mother resists engaging in the conversation. Despite what Zaree describes as a close and affectionate relationship with her mother, the past—particularly their time in Ivīn Prison—remains an unspoken subject. For over three decades, they have avoided confronting the traumatic memories associated with this time. This silence begins to shift during a summer holiday, when Zaree musters the courage to reveal her intention to make a documentary about their shared history. In a pivotal and intimate scene, the two women float on rafts in a swimming pool, captured in a medium shot from above. The camera’s perspective, coupled with the serene setting, emphasizes their closeness and establishes a safe, private space for them to begin addressing their long-suppressed past. This moment marks the tentative opening of a dialogue that has been avoided all of Zaree’s life.

Following this declaration, Zaree shows her mother a short trailer she created for the film, hoping it will serve as a catalyst for dialogue. In the subsequent shot, her mother is seen in tears. Despite her efforts to articulate supportive and encouraging words, her emotional response reveals a profound internal conflict. Her tears betray unspoken anguish, and the conversation quickly lapses into silence. The scene subtly conveys her mother’s discomfort, who shifts frequently in her chair and poses seemingly redundant questions— “What is the trailer for? For a film? What film?”—suggesting an attempt to delay or deflect the emotional weight of the subject. Her visible unease underscores the difficulty and pain associated with revisiting a traumatic past that has long been suppressed. This moment highlights the fragility of memory as well as the intergenerational struggle to articulate trauma, even within intimate family spaces.

This scene can be understood through Manijeh Moradian’s book This Flame Within: Iranian Revolutionaries in the United States. She conceptualizes memory as “individual explorations of a larger phenomenon: the complex and unpredictable interaction between dramatic historical events and the intimate experiences of everyday life that shape people into political subjects.”7Manijeh Moradian, This Flame Within: Iranian Revolutionaries in the United States (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2022), 34. This framing emphasizes that Zaree’s mother’s memories are not merely personal, but are shaped by—and reflective of—broader historical forces. Moreover, Moradian introduces the concept of “revolutionary affects,” which she defines as “those visceral intensities generated by experiences of repression and resistance that remain latent within the body.”8Manijeh Moradian, This Flame Within: Iranian Revolutionaries in the United States (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2022), 7. In the context of Zaree’s mother, these affects manifest as the embodied residue of dictatorship, imprisonment, and diasporic displacement, shaping both her visible unease and her silences. The scene thus exemplifies how personal memory and historical trauma are interwoven, and how revolutionary affects continue to resonate within the intimate spaces of familial interaction.

The next phase of Zaree’s journey toward self-discovery unfolds through psychoanalysis, long-awaited conversations with her father, and visits to family friends and relatives who may be able to reveal fragments of the past. What begins as a search for the facts surrounding her birth gradually reveals itself to be something much broader and more politically charged. Her story is not unique, and like so many children born into political violence she has been shaped by silences, ruptures, and inherited trauma. In a way the truth of her birth is not a singular experience, but one of many embedded within collective histories of repression and resistance.

A central element of this investigation is Zaree’s reunion with her father, a former political prisoner who served his sentence under the constant threat of execution. Zaree meets him in Europe, and together they revisit the letters he wrote while in prison and look at old photographs. In one intimate and emotionally restrained scene, father and daughter sit side by side on the ground, captured in a static shot that emphasizes the stillness and weight of the moment. As her father reads aloud, Zaree listens with intense concentration, her gaze fixed not only on the text but on his face, examining the traces of a past she never fully knew. Her quiet observation becomes a form of reading in itself: an attempt to decipher memory from gestures, expressions, and pauses. In this act of witnessing, Zaree begins to piece together a fragmented history, forging a deeper understanding of her father’s experiences and their shared legacy.

Figure 3: Zaree and her father look through family photo albums. Still from Born in Evin, directed by Maryam Zaree, 2019.

In her critical essay, Bādī underscores the importance of preserving letters, photographs, and audio recordings, asserting that such materials are essential for documenting both personal and collective histories.9Nuzhat Bādī, “Rāvī-i yak sarguzasht-i jam‘ī,” [Narrator of a Collective History],” Cahiers du féminisme, accessed October 2, 2025, https://cahiersdufeminisme.com/%d8%b1%d8%a7%d9%88%db%8c-%db%8c%da%a9-%d8%b3%d8%b1%da%af%d8%b0%d8%b4%d8%aa-%d8%ac%d9%85%d8%b9%db%8c/ [translated by Tania Ahmadi]. According to Laura U. Marks’ concept of “sense memories,”10Laura U. Marks, The Skin of the Film: Intercultural Cinema, Embodiment, and the Senses (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2000), 258. personal memorabilia are not merely evidentiary, but may also function as sensory portals through which exiled individuals reconnect with the people, places, sounds, and tastes of a lost home. Rather than affirming the existence of what has been lost, these materials raise awareness for the gradual erasure of lives and histories. Letters, in particular, serve as both intimate and historical archives, giving voice to the silence adopted over years of political and personal upheaval. Through them, Zaree uncovers a critical yet forgotten moment in her past: a brief but powerful visit she and her mother made to her imprisoned father following her mother’s release. It was during this encounter that her father saw and held her for the first time. This recollection emerges not as a complete narrative but as a fragmented memory—one that enriches the emotional fabric of the film. The documentary further reveals the painful decision made by Zaree’s parents to send her to live with her grandparents while her mother remained incarcerated for two additional years. Physical and emotional separation becomes a central motif in the film’s exploration of disrupted familial bonds and the intergenerational transmission of trauma. The film’s formal strategies—its deliberate use of mise-en-scène, static compositions, and narrative ellipses—mirror this emotional fragmentation. In this way, the film constructs a counter-history to official narratives, reclaiming memory as both a political and personal act.

Building on this sense of emotional and narrative fragmentation, the film also eschews linear storytelling in favor of a spiral structure that reflects the recursive nature of trauma and memory. The narrative does not move forward in a straight line but instead circles back on itself, revisiting people, places, and images in a rhythm that mimics personal recollection and the repetitions of traumatic experience. Early in the film, Zaree introduces her stepfather, Kurt, a psychoanalyst and the son of Holocaust survivors. His research on intergenerational trauma profoundly shapes Zaree’s own interpretive lens, expanding on the intergenerational dimension of and adding a transnational dimension to the story. Kurt’s understated presence reminds viewers that personal and political trauma can transcend disparate historical contexts. Adding further dimension to the familial dynamic is the presence of Zaree’s disabled sister, born of her mother’s second marriage. Her inclusion subtly broadens the film’s scope, reminding viewers that the aftermath of trauma is not limited to a single historical rupture but is lived through the everyday realities of caregiving, identity, and responsibility. The sister’s presence introduces a quieter, embodied experience of marginalization—one that is not explicitly narrated but remains visually and emotionally resonant, reinforcing the film’s attention to the unspoken and the peripheral. Here the film not only documents the past but also interrogates how individuals continue to live with it—how they talk about it, represent it, and grapple with the parts of it that resist articulation.

This concern with how memory is reconstructed—both individually and collectively—is further explored in Zaree’s conversation with Shādī Amīn,11Shādī Amīn (she/they), a pioneering Iranian LGBTI activist and writer, is the coordinator of the Iranian Lesbian and Transgender Network (6Rang). a prominent human rights activist and researcher who has conducted extensive interviews with hundreds of former female political prisoners. In one evocative scene, Amīn brings out a basket filled with small dolls and invites Zaree to reenact her birth in the Ivīn prison cell. The camera shifts to a medium close-up, focusing on Zaree’s hands as she carefully places a small doll inside the clothing of another, symbolizing her pregnant mother. Amīn gently prompts her for further details, asking whether others were present in the cell. In response Zaree arranges dolls and wooden blocks to recreate the setting—an unexpected accomplishment, considering it is very rare to remember one’s own birth. These images, though not fully formed, seem to persist in her memory in fragmentary, affective ways. As Moradian writes, “The movement of memory, its selectivity, changeability, erasures, and disjunctures may be all the more apparent for the exile or the refugee who cannot return to the places that are being remembered, who can only conjure up the past that was home from the ongoing displacement of diaspora.”12Manijeh Moradian, This Flame Within: Iranian Revolutionaries in the United States (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2022), 34.

This act of imaginative reconstruction aligns with Bill Nichols’ understanding of reenactment in documentary film. Nichols argues that “[r]eenactments occupy a strange status in which it is crucial that they be recognized as a representation of a prior event while also signaling that they are not a representation of a contemporaneous event.”13Bill Nichols, “Documentary Reenactment and the Fantasmatic Subject,” Critical Inquiry 35, no. 1 (Autumn 2008): 73. In this context, Zaree’s use of dolls functions not as an attempt to replicate historical accuracy but as a form of emotional and psychological engagement with a traumatic experience she cannot fully recall. As Nichols notes, “the reenacted event introduces a fantasmatic element that an initial representation of the same event lacks.”14Bill Nichols, “Documentary Reenactment and the Fantasmatic Subject,” Critical Inquiry 35, no. 1 (Autumn 2008): 73. The mediated act of reenactment allows Zaree to externalize a deeply personal trauma and make visible the affective traces of a silenced past. Through this stylized performance of memory, the documentary foregrounds the ways in which trauma resists linear narration and instead emerges through embodied, symbolic, and often nonlinear forms of expression.

Figure 4: Zaree uses dolls to reenact a memory. Still from Born in Evin, directed by Maryam Zaree, 2019.

Figure 5: Zaree depicts her pregnant mother using dolls. Still from Born in Evin, directed by Maryam Zaree, 2019.

Amin finally encourages Zaree to place herself in her mother’s position, prompting a deeper emotional engagement with her mother’s experience of imprisonment. It becomes evident that Zaree harbors a sense of frustration and incomprehension toward her mother’s long-standing silence. In Amīn’s presence, she begins to visualize her mother as a pregnant prisoner—isolated from her loved ones, emotionally burdened, and physically responsible for the life growing inside her. The camera lingers in a close-up on Zaree’s face as she struggles to hold back her tears, eventually overcome with emotion. This moment marks a turning point in the film: an instance where empathy and imagination converge to bridge the generational gap between mother and daughter, allowing Zaree not only to witness but also begin to embody the unspoken trauma of her family’s past.

The third phase of Zaree’s journey of discovery unfolds as she travels to France to visit her aunt and her mother’s former cellmate. It is through these encounters—and her subsequent attendance at a feminist conference in Florence—that the fragmented pieces of her personal history begin to cohere. Each person she meets contributes a detail to the evolving mosaic. Her aunt, for instance, admits that she never found the courage to ask Zaree’s father about the torture he endured in prison, while her mother’s former cellmate, who witnessed Zaree’s birth, recalls the entire cell erupting in tears and applause on that unforgettable night. These memories, though partial and subjective, become essential threads in the reconstruction of Zaree’s past.

A key figure in this chapter of piecing together her past is Chahla Chafiq,15Chahla Chafiq is an Iranian sociologist and writer. She participated in the 1979 Revolution but went into exile following the rise of the Islamic regime. Now based in France, she writes in both French and Persian on gender and political Islam. a sociologist and scholar who studies Iran’s oppressive social norms, including its prison system. In an intimate and visually poetic scene, the two women sit together in a warmly lit café, their chairs bathed in tones of orange and brown. As Chafiq holds Zaree’s hand, the moment is brimming with cinematic intimacy and emotional depth. Chafiq speaks about the difficulty of survival, the weight of tragedy, and the enduring impact of silence. Her most powerful insight comes when she advises Zaree not to be discouraged by her mother’s secretiveness, suggesting that silence is in fact a part of Iran’s historical condition—a form of testimony shaped by trauma and fear. Chafiq’s perspective reframes Zaree’s narrative. She emphasizes that Zaree’s story is not unique but rather embedded within a broader social and political context shared by many others who have lived through repression and exile. It is Chafiq who introduces Zaree to the annual feminist conference for Iranian women in exile in Florence, a space for solidarity building and intellectual exchange. The conference becomes more than a destination—it is a catalyst, drawing Zaree ever closer to the closure she seeks and affirming the political and emotional significance of remembering.

In another chapter of her book, Moradian defines “affects of solidarity” as the embodied, emotional connections that motivated Iranian student activists in the United States during the 1960s and 1970s to engage in anti-imperialist and anticolonial struggles. Moradian asserts that the activists’ personal experiences of repression and resistance in Iran fostered their solidarity with other marginalized groups, including those associated with the Black liberation movement and Palestinian resistance. She notes that “affective attachments to the liberation of others are necessary for the emergence and sustainment of mass movements seeking systematic change.”16Manijeh Moradian, This Flame Within: Iranian Revolutionaries in the United States (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2022), 134. The Florence conference scene exemplifies this dynamic: by encountering other Iranians born in prison, Zaree situates her personal experience within a collective, transnational network. Diaspora, in this context, becomes not only a condition of displacement but a site of solidarity—a political community that transcends national borders. Affects of solidarity allow individuals to empathize with each other’s losses and to act collectively, producing “a collective expression of melancholia.”17Manijeh Moradian, This Flame Within: Iranian Revolutionaries in the United States (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2022), 140. For Zaree, these affects provide a profound sense of belonging within a community that recognizes and validates her pain.

At the conference, Zaree presents her documentary project, explaining that she is searching for individuals who, like herself, were born inside Ivīn Prison. Following her talk some attendees approach her to share their own experiences of incarceration or memories of children being born in prison. Miraculously, a few people who had also been born in captivity agree to meet with her for the sake of the documentary. However, a few of these individuals later cancel, saying they cannot bear the emotional weight of revisiting the trauma. Zaree is ultimately able to have conversations with several individuals, including Chowra Makaremi,18Chowra Makaremi is an anthropologist and researcher at the CNRS in Paris. Her work focuses on state violence—both judicial and everyday—and the experiences of those subjected to it, particularly in exile. She is also the director of Nothing: An Iranian History, a documentary that explores her family’s memories and personal history as the daughter of an Iranian dissident killed after the Islamic Revolution, interweaving biography with the political history of Iran. Nīnā Zandkarīmī,19Nīnā Zandkarīmī is a psychologist based in London who, as a child, was imprisoned alongside her mother in Ivīn Prison. and Sahar Dilījānī.20Sahar Dilījānī is an Iranian author whose internationally acclaimed debut novel, Children of the Jacaranda Tree, draws heavily on her personal experience. Born in Ivīn Prison, her novel spans the years 1983 to 2011, culminating in the Iranian Green Movement, and reflects the struggles and hopes of young Iranians making history today. All three share traumatic histories involving state violence, with parents who had been imprisoned or executed. Among them, Dilījānī’s experience most closely mirrors Zaree’s—she, too, was born inside Ivīn Prison.

The meeting with Dilījānī is pivotal, as it brings together two women bound by a traumatic past they can scarcely remember—one that is shrouded in silence, as both their mothers are too pained to speak of it. Their conversation becomes an act of mutual recognition. They share fragments of memory, moments of laughter, and periods of quiet reflection. In this intimate exchange, Zaree’s suffering is no longer hers alone. Through her dialogue with Dilījānī, the weight of her trauma is acknowledged, mirrored, and, to some extent, alleviated. This act of witnessing and emotional reciprocity becomes a subtle yet powerful gesture of solicitude. It signals a political and personal intervention—a quiet, effective resistance against erasure and a contribution to the slow labor of healing and historical reckoning.

Figure 6: Zaree and Dilījānī by the sea following their conversation. Still from Born in Evin, directed by Maryam Zaree, 2019.

Zaree’s cinematic language renders this emotional arc with gentle visual poetics. The motifs of compassion and emotional resolution are articulated through formal strategies that emphasize intimacy and reflection. In a contemplative medium shot, Zaree and Dilījānī stand side by side before the sea, their bodies framed against the horizon as the ambient sound of waves underscores a moment of stillness and introspection. They exchange glances before walking out of the frame, giving way to an evocative image of the sea—a recurring visual metaphor for memory, time, and emotional depth. A subsequent long shot shows the two from behind, talking and laughing as they play in the sand. This use of the long take and diegetic sound emphasizes their shared vulnerability and the slow unfolding of trust. Overlaying this scene is Zaree’s voiceover, in which she reflects that the issue was never truly her mother’s silence but rather the way Zaree herself had been framing her questions. This realization marks the culmination of Zaree’s journey—a narrative and emotional closure that affirms the transformative potential of dialogue, memory, and cinema and their status as tools for self-discovery and intergenerational healing.

Figure 7: Zaree and Dilījānī are seen framed against the horizon, looking out over the sea. Still from Born in Evin, directed by Maryam Zaree, 2019.

Accented Cinema and the Representation of Displacement

In an early scene in Born in Evin, a medium shot captures Zaree preparing for a scene in a German television series. Another woman, most likely an assistant on set, carefully wraps a tight hair covering around Zaree’s head, pulling in every strand of hair to ensure that none remains visible. She then drapes a chador over Zaree, at which point Zaree’s facial expression becomes tense—she freezes, visibly uncomfortable. Breaking the silence, she assertively tells the assistant that there is no way she can wear the costume, emphasizing that it conveys a distorted and unrealistic image of refugees: “No one arrives dressed like this on a boat,” she insists. The camera then cuts to a semi-long shot, centering Zaree in the frame, now fully costumed in an exaggerated, hyper-conservative outfit. She glances behind her to ensure no one is around, then points toward her own camera, stating: “This is just badly researched, crappy German television. It is totally clueless and stupidly racist.” This moment powerfully exposes the persistent misrepresentation of refugees in mainstream Western media and highlights Zaree’s strong disapproval of reductive, orientalist narratives that erase complexity and individual agency.

Figure 8: Zaree prepares for a scene in a German television series, portraying a Middle Eastern Refugee. Still from Born in Evin, directed by Maryam Zaree, 2019.

Figure 9: Zaree’s facial expression grows tense in her hyper-conservative outfit. Still from Born in Evin, directed by Maryam Zaree, 2019.

Naficy’s theory of “accented cinema” offers a useful lens for understanding Zaree’s critical intervention. The term refers to the filmmaking practices of exilic and diasporic directors—often those who have migrated from the Global South to the West—whose work is marked by a condition of displacement and cultural in-betweenness. For Naficy, a film is not “accented” simply because its maker speaks with a linguistic accent; rather, a film’s accent emerges from conditions of deterritorialization, fragmented narrative structures, and artisanal or independent modes of production that reflect the filmmaker’s marginal status.21Hamid Naficy, An Accented Cinema: Exilic and Diasporic Filmmaking (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2001), 4. These films often inhabit liminal spaces, navigating competing ideologies, languages, and identities. Born in Evin exemplifies this in-betweenness, both aesthetically and thematically. Zaree speaks several languages—including German, Persian, and English—which draws attention to her complex diasporic identity. In one of the film’s aforementioned archival segments, a family video recorded in Frankfurt in 1991 and intended for her father in Iran, a young Zaree, then in the second grade, looks into the camera and begins introducing herself. Mid-sentence, she abruptly pauses and asks whether she should continue speaking in German. This moment captures a profound instance of linguistic and cultural dislocation, emblematic of the internal negotiation between inherited and adopted languages that defines much of Zaree’s work.

This early moment of identity negotiation foreshadows a broader strategy that runs throughout Born in Evin. Rather than remaining confined by the tensions of her diasporic condition, Zaree transforms them into a critical vantage point—one that enables her to challenge clichéd representations and resist reductive portrayals of exile, displacement, and trauma. In doing so, she articulates a distinctive voice that moves fluidly between personal testimony and political critique. Her shift between languages, cultural references, and visual modes is a deliberate strategy of self-definition and resistance, not a marker of confusion or fragmentation. In this way, Born in Evin demonstrates the transformative potential of accented cinema, where personal and cultural dislocation are not merely narrated but reworked into new forms of aesthetic and political agency.

Building on Naficy’s framework, Pinar Fontini introduces the concept of “accented feminism” to account for the gendered dimensions of diasporic filmmaking often overlooked in existing scholarship. In her analysis of works by Kurdish female filmmakers, Fontini argues that while accented cinema offers a compelling model of cultural hybridity, it can fall short in addressing how gender mediates experiences of displacement, authorship, and belonging.22Pinar Fontini, “Her Resistance Is Many: The Accented Filmmaking Practice of Mizgin Müjde Arslan,” Feminist Media Studies 23, no. 5 (2023): 2270. Her framework is particularly productive for understanding Born in Evin, which foregrounds Zaree’s self-reflexive authorship as both filmmaker and subject. Zaree provides voice-over narration, in which she reflects on her past roles as an actress, noting that she is skilled at telling others’ stories but eventually reached a point when she could no longer hide behind them. This turn toward self-authorship became, in effect, a radical act of resistance. As Bādī puts it, “This young woman’s refusal to conform to her assigned cinematic role and her decision to act as herself marks a prelude to stepping into the real world of her own life.”23Nuzhat Bādī, “Rāvī-i yak sarguzasht-i jam‘ī,” [Narrator of a Collective History],” Cahiers du féminisme, accessed October 2, 2025, https://cahiersdufeminisme.com/%d8%b1%d8%a7%d9%88%db%8c-%db%8c%da%a9-%d8%b3%d8%b1%da%af%d8%b0%d8%b4%d8%aa-%d8%ac%d9%85%d8%b9%db%8c/ [translated by Tania Ahmadi]. Indeed, Zaree’s dual role in the film intensifies its emotional and political impact by blurring the boundaries between testimony, performance, and authorship.

Fontini introduces the term “accented feminism” as a critical alternative to the problematic notion of the “Third World.” She criticizes the term “Third World” for implying a hierarchical global structure—one that presumes the existence of a “First” and “Second” world, thereby positioning the third as inherently dependent, underdeveloped, and less civilized.24Pinar Fontini, “Her Resistance Is Many: The Accented Filmmaking Practice of Mizgin Müjde Arslan,” Feminist Media Studies 23, no. 5 (2023): 2277. By contrast, “accented feminism” emphasizes that differences are not deficiencies but rather nuanced markers of identity and cultural specificities. The “accent” here signals both a departure from dominant norms and a disruption of the supposed purity of mainstream, universalist feminism. It breaks the illusion of standardization and questions the hegemony of Western feminist discourse by introducing alternative voices and epistemologies.25Pinar Fontini, “Her Resistance Is Many: The Accented Filmmaking Practice of Mizgin Müjde Arslan,” Feminist Media Studies 23, no. 5 (2023): 2277. In Born in Evin, Zaree embodies this notion by offering a dual critique. On the one hand, she confronts the Iranian regime’s role in perpetuating a legacy of trauma and silence across the generations; on the other, she challenges the Eurocentric narratives prevalent in German and broader Western portrayals of refugees. Rather than accepting the reductive role of victimhood often imposed on displaced individuals, Zaree reclaims agency for herself and for other Iranian voices. She courageously uncovers her personal history, regains her memories, and, as a filmmaker, constructs a space in which others can speak for themselves—unmediated, complex, and fully human. In doing so, she enacts an accented feminism that resists both political repression and cultural simplification.

The film frequently foregrounds the cinematic apparatus, making the presence and positioning of the camera explicitly visible. In one scene, for example, Zaree is shown walking through the streets of Paris on her way to interview her aunt and her mother’s former cellmate. The handheld camera follows her movements, drawing attention to its own mobility and mediation. These self-reflexive moments invite viewers to reflect on the constructed nature of the documentary and on Zaree’s exploration of her dual role as both filmmaker and subject. Her physical presence both behind and in front of the camera becomes a powerful symbol of reclaiming narrative control: she not only revisits inherited trauma but also actively shapes how the story of it is told. The camera, in this context, becomes more than a recording device—it is an extension of Zaree’s agency and authorship.

Crucially, her ownership and control of the camera mark a visual and narrative departure from her earlier on-screen appearances, where she is seen cast in clichéd refugee roles shaped by externally imposed narratives. In Born in Evin, Zaree asserts control over the storytelling process, shifting the gaze from one placed upon her to one she actively constructs. This act of reclaiming visual and narrative authorship resists reductive portrayals of refugee identity and challenges the politics of representation. Her refusal to perform a simplified or fabricated identity is not merely an aesthetic choice but a political one—an act of self-determination within a cinematic landscape that often marginalizes diasporic women. Through her presence behind the camera, Zaree offers a more layered exploration of trauma, inheritance, and agency, speaking both with and through the cinematic form on her own terms.

The experience of border crossing and the strategic use of language play a critical role in shaping the diasporic identity of the film. At the intersection of personal memory and national trauma lies the transnational journey Zaree undertakes across various European countries, where she meets with individuals whose lives echo aspects of her own history. This movement is accompanied by frequent shifts in language, embodying what Fontini aptly describes as “linguistic liminality.”26Pinar Fontini, “Her Resistance Is Many: The Accented Filmmaking Practice of Mizgin Müjde Arslan,” Feminist Media Studies 23, no. 5 (2023): 2275. Among these languages, Persian holds particular significance. For instance, when Zaree introduces her project at the conference in Florence, she chooses to present in Persian despite her lack of fluency, signaling a deliberate return to her linguistic roots. Similarly, her conversations with her father are conducted primarily in Persian, reinforcing a deep emotional and cultural connection.

As Naficy argues, the accented filmmaker’s insistence on using her native language—even at the risk of limited accessibility across borders—can be interpreted as a conscious effort to preserve the bond between herself and her native cultural heritage.27Hamid Naficy, An Accented Cinema: Exilic and Diasporic Filmmaking (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2001), 24, 122. This emotional attachment to Persian is further underscored by the recurring use of the song “Gole Yakh” (“Ice Flower”) by Kūrush Yaghmāyī. Composed in 1973, the song explores themes of love, loss, loneliness, and lost youth, using the “ice flower” as a metaphor for emotional fragility. Heard in fragmented pieces throughout the film, the song not only honors the Persian language and culture but also resonates with the historical and political realities of the era and mirrors the hearts of Zaree’s documentary subjects—former political prisoners whose lives and youth were shaped by loss and exile.

As an undeniably “accented” documentary, Born in Evin is intentionally rooted in the experiences of refugees and immigrants. From Zaree’s mother, who was forcibly displaced, to her father, to Zaree herself and the many people who support her throughout her journey, the documentary traces a collective narrative shaped by migration and exile. What stands out is the way these individuals are portrayed—markedly different from the ignorantly simplified and dehumanizing depictions of immigrants commonly seen in German and other Western media. As Edward Said observed in his theory of Orientalism, refugees and people from the Middle East are frequently rendered as exotic or othered beings.28Edward W. Said, Orientalism (New York: Pantheon Books, 1978), 1-28. By contrast, Zaree presents them as complex, fully human subjects engaged in struggles for justice, respect, and equality. Many of the film’s subjects are highly accomplished. Zaree’s mother became the first female migrant candidate for mayor in Germany; Zaree herself is a successful filmmaker and actress; and the rest are anthropologists, psychologists, lawyers, and other professionals in various fields. By showing these individuals as they truly are, Zaree widens perspectives and opens hearts, challenging and dismantling stereotypical portrayals of immigrants. Ultimately, she offers a nuanced and empowering representation that asserts immigrants’ agency, intellect, and humanity.

Conclusion

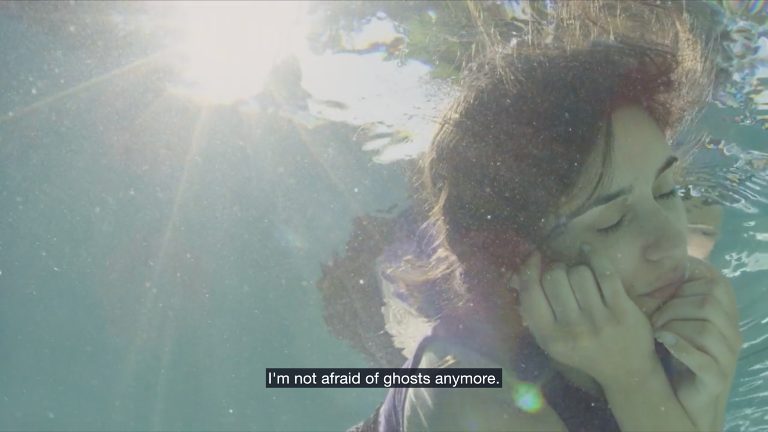

In the final moments of Born in Evin, Zaree jumps into a swimming pool, mirroring an early scene in the film in which she informs her mother of her intention to make the documentary. This parallel emphasizes a cyclical narrative structure that underscores a sense of both return and transformation. The camera, positioned underwater, captures her descent in slow motion. Once submerged she holds her breath and curls into a fetal position—a visual evocation of confinement, gestation, and emotional entrapment. Surrounded by rising bubbles, this image becomes a powerful metaphor for the inherited trauma of her mother’s past and the silence that shaped her identity. A subsequent close-up lingers on Zaree’s face beneath the surface—her eyes closed, with light streaming down from above—suggesting a state of vulnerability and the possibility of transcendence and renewal. In the next shot, Zaree floats in the center of the frame, a tree in the background, in a symbol of growth, continuity, and rootedness. Over these clips Zaree delivers a voice-over that takes the form of direct questions to her mother: “Is it true you gave birth to me blindfolded? Did they really kick you in the stomach? Did you wonder if I might be dead? Did you talk to me while I was in your belly?”

Figure 10: Zaree assumes a fetal position after jumping into a swimming pool. Still from Born in Evin, directed by Maryam Zaree, 2019.

Figure 11: Zaree remains underwater, voice-over narration revealing her thoughts on her experience. Still from Born in Evin, directed by Maryam Zaree, 2019.

Figure 12: Zaree finally finds the right words to express to her mother. Still from Born in Evin, directed by Maryam Zaree, 2019.

These questions, posed without hesitation, mark a turning point in Zaree’s narrative stance—from suppressed uncertainty to open confrontation. The fear that once surrounded the past is replaced with clarity and emotional courage. In the final shot of the sequence, the camera lingers in a close-up of Zaree as she remains suspended in the water. Her voiceover concludes with a simple, profound statement to her mother: “I’m sorry for all you had to go through.” In speaking aloud these powerful words, Zaree experiences a moment of emotional catharsis. Her on-screen emergence from the water can be read as a symbolic rebirth—this time not into a prison cell, but into her true, self-authored identity, liberated from the silence that has shaped her family history. In this moment Zaree embodies the feminist principle that the personal is political, transforming her exploration of private pain into an act that resonates beyond her individual experience, inviting others who share similar histories of silence and trauma to confront their own stories and join a broader act of resistance.

In the following scene, Zaree’s mother finally opens up to her—not by directly answering Zaree’s questions about the past, but by offering a perspective that deepens our understanding of her character. Rather than a candid tell-all, her words reveal an internal struggle to cope with the psychological aftermath of imprisonment and the lingering trauma that endures despite her physical freedom. Her long-held silence, as Laura Pottinger describes, embodies a form of “quiet activism,” comprising “small, everyday, embodied acts, often making and creating, that can be either implicitly or explicitly political in nature.”29Laura Pottinger, “Planting the Seeds of a Quiet Activism,” Area 49, no. 2 (2017): 215, https://doi.org/10.1111/area.12318. The film positions her not as a passive victim but as a resilient figure whose refusal to narrate directly is a conscious act of defiance. In this sense, her body becomes a vessel of memory, transmitting trauma and resistance across time and context. As Moradian observes, “history is mapped into bodies, which register the sensations and moods of a certain time and place and then keep going, bringing affects and emotions from one context to another, offering up a new interpretation of the past from the always shifting vantage point of the present.”30Manijeh Moradian, This Flame Within: Iranian Revolutionaries in the United States (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2022), 21.

Through Zaree’s mother, the documentary resists the simplistic equation of silence with oppression. Instead, it portrays both Zaree’s curiosity and her mother’s guardedness as distinct forms of agency. The film’s emotional climax does not come in the form of a resolution but in the act of questioning itself, affirming inquiry as a step toward reclaiming one’s voice and identity. The process of questioning one’s history, and at the same time the history of one’s country, underscores how deeply intertwined the personal and political are, especially for those shaped by state violence, exile, and silence. Through this exercise, Zaree begins to move beyond the categorization imposed by the state, forging a counter-narrative that honors the complexity of diasporic and dissident identities.

Toward the end of Born in Evin, Zaree and her mother are seated on a couch in a warm, intimate medium shot, with her mother reciting a verse from a collection of poems by the Persian poet Hafez. In a gesture that honors the Iranian tradition of divining one’s fortune through a poet’s words, Zaree opens the book at random, and her mother reads aloud: “The good news is that sad days will be over, cherish the moment we have. Because these times will not last forever.”31This translation of Hafez’s poem is taken from the documentary’s subtitles. Surrounded by candles, flowers, and family photographs, the scene radiates tenderness and a sense of reconciliation. In this moment, Zaree seems deeply connected to both her mother and their shared past, signaling a shift toward inner peace and acceptance. This emotional resolution is not merely personal but politically resonant. As Bādī argues, “By erasing stories and suppressing historical narratives, dictatorial regimes impose their own false versions of events, constructing a fabricated history.”32Nuzhat Bādī, “Rāvī-i yak sarguzasht-i jam‘ī,” [Narrator of a Collective History],” Cahiers du féminisme, accessed October 2, 2025, https://cahiersdufeminisme.com/%d8%b1%d8%a7%d9%88%db%8c-%db%8c%da%a9-%d8%b3%d8%b1%da%af%d8%b0%d8%b4%d8%aa-%d8%ac%d9%85%d8%b9%db%8c/ [translated by Tania Ahmadi]. Born in Evin counters this erasure by positioning documentary filmmaking as a tool of resistance—one that challenges state-imposed silences and constructs a bridge between generations. Zaree’s film rejects reductive portrayals of refugees and resists binary identity categories, instead embracing the complexity of liminality—the in-between space of exile, memory, and belonging. In doing so, it affirms the enduring power of documentary not only as a medium for truth-telling, but also as a vehicle for healing, political critique, and intergenerational dialogue.

Figure 13: Zaree and her mother seated on a couch, as her mother recites a verse from Hafez. Still from Born in Evin, directed by Maryam Zaree, 2019.

In her essay “The Generation of Postmemory,” Marianne Hirsch defines postmemory as the phenomenon whereby “descendants of survivors of massive traumatic events connect so deeply to the previous generation’s remembrances of the past that they need to call that connection memory and thus that, in certain extreme circumstances, memory can be transmitted to those who were not actually there to live an event.” Born in Evin illustrates this dynamic in Zaree’s reconstruction of her mother’s imprisonment and her own birth within Evin Prison—a narrative absent from official archives. Working in exile, she draws on memory, testimony, and imaginative reenactment, demonstrating Hirsch’s assertion that the generation after trauma can form connections to a past they did not directly experience. Her postmemorial strategies—such as the use of dolls to restage her birth and the parachute as a metaphor for entanglement—transform silence into embodied acts of remembrance. Framed as a memoir-documentary hybrid, the film situates itself within the prison memoir genre33The prison memoir genre in cinema foregrounds narratives of incarceration as sites of political resistance, identity formation, and socio-political critique. It often transcends carceral settings to interrogate colonial legacies, militarized regimes, and systemic injustice. In Iranian cinema, particularly in the post-1979 period, the genre functions as a vehicle for exposing state violence, ideological repression, and the endurance of dissenting voices. A diasporic film such as Women Without Men (dir. Shirin Neshat, 2009) interweaves testimonial modes with aesthetic strategies to reflect both personal and collective trauma., tracing the psychological aftershocks of incarceration within a diasporic and feminist framework, and functions simultaneously as an act of witnessing and as a reflective archive of intergenerational trauma.

The documentary advances the ongoing struggle of Iranians to reckon with the legacy of political persecution by harnessing the distinctive capacities of film—reenactment, affective imagery, and fragmented narrative—to render silence and trauma visible in ways that surpass memoir or testimony alone. From the vantage point of diaspora, where distance from the homeland both circumscribes and enables creative intervention, Zaree aggregates fragments, mobilizes transnational solidarities, and resists both Western misrepresentations and the erasures imposed by the Iranian state. Informed by the logic of postmemory, her cinematic practice transfigures personal and familial recollection into collective testimony, demonstrating how imaginative reconstruction can retrieve histories otherwise inaccessible. The film thus positions diaspora as a transformative site for rearticulating silenced narratives, highlighting the capacity of cinema to not only document absence and trauma but to mediate historical and ethical witnessing, offering a crucial mode of engagement with the unresolved violence of Iran’s recent past.

The film concludes by returning to the desolate opening scene, where Zaree, having finished her parachute jump, finds herself entangled in the very equipment that allowed her to land safely. This striking visual serves as a potent metaphor for her psychological and emotional state: suspended between past and present, agency and constraint, and yearning for freedom while still ensnared by the weight of inherited trauma. Yet, unlike in the opening, this time she frees herself, symbolizing the transformation she has undergone. By confronting a past that was once thought unapproachable and unspeakable, Zaree affirms that healing and political resistance are not mutually exclusive, but profoundly intertwined. The film ultimately asserts that healing does not require forgetting. By speaking through pain, in whatever capacity, one may reclaim authorship over one’s own story.

Figure 14: Zaree has freed herself from the parachuting equipment. Final image from Born in Evin, directed by Maryam Zaree, 2019.

Cite this article

Born in Evin, directed by Maryam Zaree, is a feminist documentary that follows the filmmaker’s quest to uncover the circumstances surrounding her birth inside Iran’s infamous Ivīn (Evin) Prison. This essay argues that Zaree’s work functions as both a personal act of testimony and a political intervention against collective amnesia, substantiated through her investigation into the deep intergenerational trauma caused by political imprisonment. Through a non-linear narrative structure, reenactment, and self-reflexive authorship, the film also challenges dominant representations of refugee identity and memory often found in Western media. Drawing on Hamid Naficy’s concept of accented cinema and Pinar Fontini’s theory of accented feminism, this essay situates Born in Evin within broader conversations on diasporic resistance, feminist filmmaking, and the ethics of memory. Ultimately, Zaree reclaims narrative agency by transforming silence into resistance, personal pain into collective reckoning, and private memory into public history.