The Garden of Earthly Utopias: On Shirin Neshat’s Women Without Men

How might we imagine a utopian space in a past saturated by political trauma without assuming it can be fully recuperated? The question takes on particular urgency when we confront moments like the 1953 CIA-engineered coup in Iran—an event so thoroughly marked by imperial violence that any attempt to envision alternative possibilities appears foreclosed by the sheer weight of this historical impasse. Against the sense of foreclosure, Walter Benjamin insists otherwise: traumatic histories are not to be discarded as irredeemably spent but engaged as contemporary concerns, their unrealized potentials rescued from oblivion. Not all past is past. It is that image of the past, “not recognized by the present as one of its own concerns,” Benjamin writes, “that threatens to disappear irretrievably.”1Walter Benjamin, “Theses on the Philosophy of History,” in Illuminations: Essays and Reflections, ed. Hannah Arendt, trans. Harry Zohn (New York: Schocken Books, 1968), 255. Even if resurrecting the utopian imaginaries buried by catastrophe is neither viable nor politically generative, and risks regression, what should stop us from threading into that history moments of utopian imagination? These are moments that, had they taken hold, could have bent our future (this present?) otherwise, flickering as possibility before the trauma of the conjuncture reasserted itself, closing them down and leaving us suspended between the thin satisfactions of reform and the seeming impossibility of structural change. What I argue in this essay is that Shirin Neshat’s film Women Without Men (2009), in its deliberate departures from Shahrnūsh Pārsīpūr’s novella, threads a utopian interval into the history of 1953. Rather than a sovereign rewrite of national history, the film routes counterfactual pressure through intimate intervals—looks, touch, shared dwelling—at the scale of bodies and bonds. In doing so, it reimagines (and reimages) 1953 so that a trauma-laden past can be reinscribed as possibility rather than foreclosure.

The armature for Shirin Neshat’s cinematic adaptation is Shahrnūsh Pārsīpūr’s 1989 novella Women Without Men (Zanān bidūn-i mardān), a parabolic text in which a garden in Karaj, a city on the outskirts of Tehran, figures as a homosocial refuge, bringing together the lives of five women who move toward that shared space during the summer of 1953 (figure 1). Translating Pārsīpūr’s parable to the screen, Neshat braids the coup’s public tumult with quietly magic-realist intervals of intimacy, staging a provisional refuge that tests the heteronormative order. Seen in comparative relation to its literary source, which was composed in the turbulent post-revolutionary decade that intensified patriarchal structures, Neshat’s film points to the urgency of imagining a space for “women without men.” Despite shared motifs, the works diverge sharply in Neshat’s regimentation of historical evidence and her foregrounding of referential detail. Such signals of historical specificity are largely absent, or only legible between the lines, in Pārsīpūr’s novella, particularly for readers outside the Persian-language context. At the same time, Neshat presses beyond Pārsīpūr’s heteronormative reproductive logic, reconfiguring desire and kinship, another decisive point of contrast.

Figure 1: Two women on the road to the Karaj garden. Still from Women Without Men, directed by Shirin Neshat, 2009.

Women Without Men recounts the lives of five single women. Women who are not single—such as Farrukhlaqā Sadr-al-dīvān Gulchihrah, married to an army general—but singular in their collective search for a space of togetherness outside the heteronormative calculus that opposes “single” only to “married.” As Gayatri Spivak asks in a brief and touching memoir: “When, and indeed how, are women not single? Do we need a special analytic category for female collectivities? For lesbian couples? For single lesbians? Is the antonym of single—double? Multiple? Or always–married?”2Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, “If Only,” The Scholar and Feminist Online 4, no. 2 (Spring 2006) https://sfonline.barnard.edu/if-only/(accessed: October 1, 2025). Spivak’s question brings into focus what I mean by the singularity that binds Pārsīpūr’s women. It allows us to understand their apparently utopian space as entangled with a politics of singularity, in which reproductive heteronormativity appears not as the governing norm but as only one case among many, “like a stopped clock giving the correct time twice a day, rather than a norm that we persistently legitimize by reversal.”3Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, “If Only,” The Scholar and Feminist Online 4, no. 2 (Spring 2006) https://sfonline.barnard.edu/if-only/(accessed: October 1, 2025). The garden in Karaj where Pārsīpūr’s women ultimately gather, envisions a space in which heteronormative logic no longer constitutes the dominant mode of being, so that other forms of singularity may emerge and take shape.

Pārsīpūr’s women set out for the garden in Karaj not to dismantle patriarchy wholesale but to negotiate alternative ways of being—“to reap the benefits of [their] toil and get rid of the men who control [them],” as Fā’izah puts it in the novel.4Shahrnush Parsipur, Women Without Men, trans. Kamran Talattof and Jocelyn Sharlet (New York: Feminist Press, 2009), 78. While Neshat’s vision of the garden resonates with the political and conceptual energies of the novel, her intervention shifts the space from an imaginary homosocial enclave to a marginal refuge, historically removed from Tehran’s tumult during the 1953 coup d’état, and imbues it with homoerotic dimensions that move beyond the politics of “women without men” toward a space where women desire one another.

Pārsīpūr’s bāgh-i Farrukhlaqā (Farrukhlaqā’s garden) mirrors many of the internal dynamics of a harem, with one crucial difference: the women choose to inhabit this homosocial space on their own terms. Even the gardener, whose absence of libidinal interest recalls the figure of the eunuch in orientalist depictions, underscores the structural echo of the harem. This may be read as a literary prefiguration of a more progressive conception of homosocial space, a conception Leila Ahmed began to theorize in the early 1980s in her writings on the harem:

The very word “harem” is a variant of the word “harem” which means “forbidden” (and also “holy”), which suggests to me that it was women who were doing the forbidding, excluding men from their society, and that it was therefore women who developed the model of strict segregation in the first place. Here, women share living time and living space, exchange experience and information, and critically analyze—often through jokes, stories, or plays—the world of men.5Leila Ahmed, “Western Ethnocentrism and Perceptions of the Harem,” Feminist Studies 8, no. 3 (Autumn 1982): 529.

Ahmed’s claim challenges the dominant myth of the harem as a space of female isolation and victimhood, calling instead for a more nuanced, historically situated reading. Yet her theorization leaves unexplored the complexities of sexual and homoerotic desire that may circulate within homosocial space.

Teresa de Lauretis’s critique of feminism’s tendency to collapse homosexual desire into homosociality is particularly salient here. In “When Lesbians Were Not Women,” de Lauretis outlines an alternative mode of subject formation, an “eccentric subject” that does not “center itself in the institution of heterosexuality,” a structure she argues has also shaped key feminist frameworks, including Ahmed’s reading of the harem and Kaja Silverman’s theorization of homosexual maternal fantasy.6Teresa de Lauretis, “When Lesbians Were not Women,” Labrys, Études Féministes (September 2003)https://www.labrys.net.br/special/special/delauretis.htm (accessed Oct 1, 2025). For Silverman’s writing on homosexual maternal fantasy see Kaja Silverman, The Acoustic Mirror: The Female Voice in Psychoanalysis and Cinema (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1988). For de Lauretis, the notion of “woman-identified female bonding” evacuates the question of desire between women and, in doing so, fails to disrupt the hold of heteronormativity, leaving no real space for the emergence of a new mode of subjectivity.7Teresa de Lauretis, The Practice of Love: Lesbian Sexuality and Perverse Desire (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1994), 120. It is precisely in the absence of homosexual desire—in moments such as Mūnis’s transformation into a beast who haunts the other women in the garden, or Zarrīn’s final heterosexual pairing with the gardener, culminating in pregnancy—that Pārsīpūr’s text remains bound to the logic of heteronormativity. And it is, again, through her reworking of the story, by foregrounding a homoerotic charge, that Neshat moves beyond homosociality and opens the garden into a space of homoerotic desire. I turn to two instances in Neshat’s rendering of bāgh-i Farrukhlaqā that can be read as gestures toward homoerotic desire.

Figure 2: Fā’izah stands before a mirror and gazes at her own body. Still from Women Without Men, directed by Shirin Neshat, 2009.

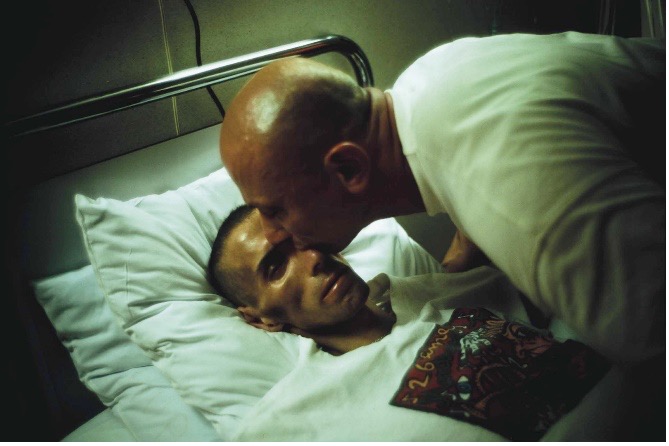

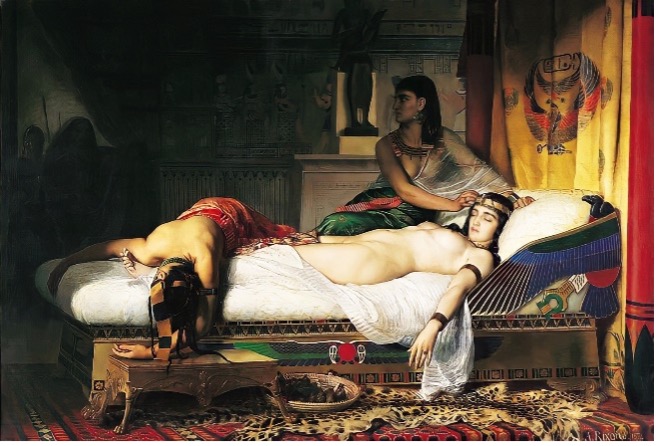

The eroticism becomes most apparent, beyond the sexual charge that shades even the women’s ordinary dialogue in the garden, when Fā’izah, anxious about her sexuality and virginity, stands before a mirror and gazes with intense curiosity at her own naked body (figure 2). In this moment, Fā’izah turns her body into both the object of desire and the site of libidinal anxiety, refusing the position of passive object before the camera’s lens and redirecting the gaze into something averted, creating space for a homoerotic (or perhaps autoerotic) reading. A second, more explicitly homoerotic moment comes in the scene of Zarrīn’s death: Farrukhlaqā, in mourning, rests her head upon Zarrīn’s torso and remains in that intimate pose through the night until sunrise (figures 3–4). This tender, sexually charged image, more photographic than cinematic in its stillness, lingers for several seconds and evokes art-historical precedents of mourning and same-sex desire. Its semantic weight recalls Nan Goldin’s Gotscho Kissing Gilles (deceased) (1993), a portrait of erotic intimacy and grief (figure 5). Formally, however, the image perhaps most closely aligned with Neshat’s scene is Jean-André Rixens’s The Death of Cleopatra (1874), whose composition and lighting resonate with the tableau of Zarrīn’s death (figure 6).

Figures 3-4: Farrukhlaqā rests her head upon Zarrīn’s torso in mourning. Stills from Women Without Men, directed by Shirin Neshat, 2009.

Figure 5: Gotscho kissing Gilles in a hospital bed. Nan Goldin, Gotscho Kissing Gilles, Paris, 1993, dye-bleach print, 68.6 × 101.6 cm.

Figure 6: Composition and lighting echoing the tableau of Zarrīn’s death. Jean-André Rixens, The Death of Cleopatra, 1874, oil on canvas, 199 × 290 cm, Musée des Augustins, Toulouse.

If we take these cinematic moments to mark Neshat’s departure from a space of homosociality toward a garden shaped by homoerotic charge, where even the gardener, in contrast to the novella, is stripped of his reproductive function, then we must ask what keeps this attention to female desire from slipping into the aesthetic circuits of trend, marketability, or commodified “global queer.” What protects Women Without Men from being absorbed into the broader cultural economy that capitalizes on the visibility of same sex desire while neutralizing its political force? Or does Neshat’s film, as de Lauretis warns, become an accomplice to a postmodern culture in which lesbian visibility is heightened at the risk of blurring lesbian specificity, turning lesbian desire into a desire like any other—a move that reduces it to the “incidental, private, and thus […] politically inconsequential”?8Anat Pick, “New Queer Cinema and Lesbian Films,” in New Queen Cinema: A Critical Reader, ed. Michele Aaron (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2004), 109-110. Any answer may lie less in the film’s title, or in its investment in a politics of singular women alone, than in its formal strategies—in the ways its visual construction and narrative architecture work together.

Fredric Jameson’s formulation of magic realism proves especially instructive, not just because Pārsīpūr’s writing and Neshat’s film have been linked to the genre,9See the afterword of Women Without Men written by Persis Karim, or Asghar Ma‘sūmbaygī’s review of the book published in 2001. but because his account clarifies how form negotiates the tension between political rupture and aesthetic absorption. For Jameson, magic realism provides “a possible alternative to the narrative of contemporary postmodernism.”10Fredric Jameson, “On Magic Realism in Film,” Critical Inquiry 12, no. 2 (Winter, 1986): 302. The latter, he suggests, is exemplified by the nostalgia film, which seeks to “generate images and simulacra of the past […] producing something like a pseudopast for consumption as a compensation and a substitute for, but also a displacement of, that different kind of past which has (along with active visions of the future) been a necessary component for groups of people in other situations in the projection of their praxis and the energizing of their collective project.”11Fredric Jameson, “On Magic Realism in Film,” Critical Inquiry 12, no. 2 (Winter, 1986): 310. Where nostalgia film encourages surface-level engagement and aesthetic consumption, magic realism—whether in Pārsīpūr’s prose or in Neshat’s visual grammar—disrupts narrative expectation and resists turning the past into commodity form.

Neshat’s use of magic realism enacts what Jameson calls a “visual spell”: an image-world that captivates without flattening, anchoring viewers in the sensory present of the frame while withholding the interpretive closure typical of mainstream narrative cinema.12Fredric Jameson, “On Magic Realism in Film,” Critical Inquiry 12, no. 2 (Winter, 1986): 303. This spell first takes hold in the film’s opening sequence, when Mūnis, filmed in slow motion, leaps from the rooftop and descends not with the blunt finality of death but with the suspended grace of dance. The moment delivers what Jameson might call a “shock of entry,” staging what he elsewhere describes as “the body’s tentative immersion in an unfamiliar element.”13Fredric Jameson, “On Magic Realism in Film,” Critical Inquiry 12, no. 2 (Winter, 1986): 304. It is a scene that resists linear progression, rendering the trauma of historical rupture as an immersive visual event that refuses the narrative protocols of beginning, development, and resolution (figures 7–8). This refusal of narrative resolution recalls what de Lauretis describes as a challenge to “lawful narrative genre”—dominant structures such as the romance which regulate identification and development through heteronormative logics.14Teresa de Lauretis, The Practice of Love: Lesbian Sexuality and Perverse Desire (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1994), 122. Women Without Men unsettles these generic expectations, not only through its disruption of narrative progression but also through its resistance to systems of identification that collapse homoerotic possibilities, or other modes of alternative female subjectivity, into the inconsequentiality of the apolitical.

Figure 7: Mūnis leaps from the rooftop in the film’s opening sequence—a “shock of entry” that stages the body’s tentative immersion in an unfamiliar element. Still from Women Without Men, directed by Shirin Neshat, 2009.

Figure 8. Mūnis’s suspended fall, returning in the film’s closing sequence. Still from Women Without Men, directed by Shirin Neshat, 2009.

What at first might seem a narrative flaw in Neshat’s film, illustrated by the stark disjunction between the events unfolding in Tehran and the sudden, unmotivated convergence of the women in the Karaj garden, produces a rupture in linearity that serves as a defamiliarizing force. It unsettles the conventions of heterosexual cinematic narrative, most clearly codified in genres such as the romance or the Western, and enables another mode of spectatorship to emerge. By disrupting the linear unfolding of events, Neshat loosens the film from the authoritative cadence of History, capital H, as a structuring narrative force. In so doing, she resists the allegorical framing often imposed on “Third World Cinema,” unsettling the phallic logic of narrative progression that rests on beginnings, developments, and resolutions. This is not to suggest, however, that Women Without Men abandons historical narrative altogether; on the contrary, the film sustains a deliberate engagement with history. I will return to this point later.

Figures 9–10: Exterior scene saturated with light. Stills from Women Without Men, directed by Shirin Neshat, 2009.

The question of narrative surfaces here in its uneasy relation to the visual register. Rather than abandoned or subverted, narrative is, in Jameson’s phrase, “effectively neutralized”15Fredric Jameson, “On Magic Realism in Film,” Critical Inquiry 12, no. 2 (Winter, 1986): 321. by the intensity of the visual: shadow-drenched interiors and overexposed exteriors (figures 9–10), the stark chromatic separation of Mūnis from the street protests (figure 11), the painterly and photographic inflections of Neshat’s framing (figure 12), and the raw, stylized violence of sequences such as the army’s intrusion into the Karaj garden or Zarrīn’s ritualistic bathing scene. This visual override, in turn, opens onto what Jameson describes as “a seeing or a looking in the filmic present,” a mode of durational attention unbound from the demands of narrative causality.16Fredric Jameson, “On Magic Realism in Film,” Critical Inquiry 12, no. 2 (Winter, 1986): 321.

Figure 11: The stark chromatic separation of Mūnis from the street protests. Still from Women Without Men, directed by Shirin Neshat, 2009.

Figure 12: Painterly and photographic inflections of Neshat’s framing. Still from Women Without Men, directed by Shirin Neshat, 2009.

Echoing Jameson’s readings of A Man of Principle (1984, dir. Francisco Norden) and Fever (1981, dir. Agnieszka Holland), Women Without Men displaces “a whole range of narrative interest and attention, which classical film laboriously acquired and adapted from earlier developments in the novel,” leaving behind only skeletal traces of plot held together by the sustained intensity of a visual spell and stylized violence.17Fredric Jameson, “On Magic Realism in Film,” Critical Inquiry 12, no. 2 (Winter, 1986): 320. As if triggered by a psychological rupture, Zarrīn, an emaciated sex worker, begins to perceive her clients as faceless figures. This uncanny vision first appears in the brothel, where the gardener, not yet disclosed as such, presents himself as a faceless client (figure 13). This sequence culminates in a moment of purification (pāk’shudan barāyi namāz) and salvation for Zarrīn, as she escapes the brothel and enters a public bath whose atmosphere recalls orientalist depictions of harem baths. The phantasmagoric bath is almost immediately unsettled, both by the camera’s altered perspective and by the grotesque violence of Zarrīn’s obsessive scraping of her skin, which draws blood from her every pore and displaces any libidinal fantasy with visceral discomfort (figure 14). The image’s surface becomes strikingly inconsumable, resisting commodification. It offers neither visual pleasure nor narrative coherence. Instead, it stages an aesthetic of rupture, resisting consumption and unsettling the spectatorial gaze.

Figure 13: The gardener appears as a faceless client in Zarrīn’s vision. Still from Women Without Men, directed by Shirin Neshat, 2009.

Figure 14: Zarrīn’s obsessive scraping draws blood from her every pore, displacing visual pleasure with visceral discomfort. Still from Women Without Men, directed by Shirin Neshat, 2009.

The visual intensity of Neshat’s film introduces another generative layer of meaning. It makes room for history-telling in the pauses, when the image withdraws just enough to allow historical consciousness to surface. If the opening of the film privileges visual intensity as a mode of utopian imagination, then this moment stages a reversal: history returns not as a distant backdrop but as an active interlocutor. Here, historical accounts are interwoven with the visual rhythm of utopia, not to neutralize the brutality of imperial violence but to sustain a dialogue between what is remembered and what is imagined. Women Without Men is, then, also an imagining of “us without them”: a vision of a nation resisting Western patriarchy and placing its utopian garden within a shared anti-colonial horizon. Neshat’s juxtaposition of this perforated history with the utopian imagination of “women without men” unfolds not as a pastiche tailored for consumption but as a deliberate formal permutation that insists on the political urgency of aesthetic form.

Where Pārsīpūr’s novel makes only a fleeting reference to the political upheaval of 1953, Neshat’s Women Without Menis deeply invested in staging the political and historical specificity of that moment. By reanimating the desires of a nation within the narrative frame, Neshat foregrounds the urgency of attending to the nation as a site of resistance, not least because the democratic polity emerging under Musaddiq was crushed by the coup. As Timothy Brennan has aptly noted:

There is only one way to express internationalism: by defending the popular sovereignty of existing and emergent third-world polities. And part of that defense is to preserve an ideological space where they can exist in the face of futurist prognoses that they have ceased existing. Crippled, vexed by the dangers of excess and exclusion, smothered by the weight of ethereal images from afar, the nation is a precious site for negotiating rights and for salvaging communal traditions. Nationalism of this type took centuries to forge and its resilience in the face of the universalizing myths of U.S. benevolence is hopeful.18Timothy Brennan, At Home in the World: Cosmopolitanism Now (Cambridge, MA and London: Harvard University Press, 1997), 316.

It is in this light, understanding the nation as a possible force against the homogenizing logics of imperial domination, that Neshat’s effort to re-center the nation within her utopian vision gains its critical urgency and should be read as a deliberate political gesture.

Yet even as Women Without Men foregrounds the nation as a site of anti-colonial resistance, it remains complicit in reproducing entrenched orientalist stereotypes of Iran, especially when the film turns to narrate the nation. Neshat’s broader oeuvre has long been entangled with the politics of national representation, most visibly in her Women of Allahseries, which helped establish her international reputation. Women Without Men risks reproducing the same iconography of exoticism, violence, and female oppression readily absorbed by the global art world’s appetite for legible signs of Middle Eastern alterity. Despite its compelling portrayal of a nation resisting colonial forces, the film fails to address the very people whose stories it recounts, relying instead on static, stereotypical images of Iranian women that circulate easily within dominant visual economies. This dynamic suggests that Neshat’s primary interlocutor remains the West, which may account for the absence of locally grounded cultural references and the presence of stylized distortions of “tradition.”

By contrast, Pārsīpūr’s Women Without Men draws its power from a richly contextualized narrative that gradually envelops the Persian-speaking reader in the world the novel constructs. Her novella is at once rooted in a local context and open to broader international resonances, yet many of its cultural and historical references are lost in translation, which flattens the specificity of the original. For instance, in the story of Māhdukht, who plants herself in the garden and gradually transforms into a tree, Pārsīpūr writes that the music emanating from the tree immersed the entire garden in a “vahm-i sabz.” The term evokes Furūgh Farrukhzād, one of the pioneers of Iranian feminist poetry, and her poem of the same title, but in translation it becomes “green illusion,” stripping away its intertextual resonance. In the original Persian, Pārsīpūr sets the term in quotation marks, underscoring its specificity and signaling a deliberate invocation of Farrukhzād’s poem, which resonates thematically with Māhdukht’s act of planting herself in the garden.

Neshat’s Women Without Men constructs a cinematic utopia that unsettles heteronormative desire and complicates the contours of political subjectivity. Yet while it employs elements of magic realism to craft a generative cinematic space for critically examining desire, it also relies at times on reductive, readily legible orientalist imagery to secure its legibility and legitimacy within the global art market. In this way, Neshat’s film both challenges and reinforces narrow representations of the Iranian nation. Even so, embedded within its aesthetic and narrative structure are moments of imaginative divergence—fleeting scenes of refuge, care, or collectivity—that unsettle the broader political impasse the film depicts. These micro-utopian moments, dispersed across the film’s visual and spatial register, can be read through Deleuze and Guattari’s concept of micropolitics, where desire functions not merely as personal or psychological but as a political force operating in the smallest units of social life.19For a discussion of desire as a micropolitical force, see Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, trans. Robert Hurley, Mark Seem, and Helen R. Lane (London: Continuum, 2004), 35, 288, 373; and A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, trans. Brian Massumi (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987), chap. 9, “1933: Micropolitics and Segmentarity.” See also Christian Gilliam, Immanence and Micropolitics: Sartre, Merleau-Ponty, Foucault and Deleuze (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press,2017), chap. 4. The garden in Karaj, for example, is not only metaphorical but a micropolitical zone where women imagine modes of life outside the phallocentric state and colonial violence. In this way, Women Without Men inserts a utopian impulse into history, not as its suspension but as a quiet refusal of its foreclosure.

If, as Fredric Jameson writes, the concept of utopia is “indistinguishable from its reality,” its ontology coinciding with its representation, then the work of Women Without Men resides in the images themselves: where form enacts refusal.20Fredric Jameson, “The Politics of Utopia,” New Left Review 25 (January–February 2004), 35. The garden scenes, rather than offering escape from history, stage a loosening of its grip, even as the film persistently returns to the named violences and street textures of the 1953 coup. While Jameson famously locates the utopian moment in the “suspension of the political,” Neshat complicates this by suturing micro-utopian intervals into a landscape saturated with political trauma.21Fredric Jameson, “The Politics of Utopia,” New Left Review 25 (January–February 2004), 43. Her cinematic retelling shifts Pārsīpūr’s homosocial refuge toward homoerotic potential, allowing desire, rather than institutional decree, to become the medium of historical negation. This is not merely an adaptation but a radical elaboration: a micropolitics of utopian imagination that unsettles heteronormative paradigms and intervenes in history without disavowing it. Utopia, here, is not retrospective but insurgent, a visual and affective proposition against the foreclosure of political possibility.

Cite this article

This article asks how a utopian interval might be imagined within a past saturated by political trauma—without presuming that the past can be fully redeemed. Taking the CIA-engineered 1953 coup in Iran as a scene of historical foreclosure, it draws on Walter Benjamin to argue that unrealized potentials from such moments remain legible to the present and can be threaded back into history without regression. It reads Shirin Neshat’s Women Without Men (2009)—precisely in its departures from Shahrnūsh Pārsīpūr’s novella—as staging such an interval. Rather than sovereignly rewriting national history, the film channels counterfactual pressure through intimate scales—glances, touch, shared dwelling—reinscribing 1953 as possibility rather than closure and configuring the garden not as an escapist sanctuary but as a heterotopic commons.

Formally, the film’s magic-realist “visual spell” (Jameson) suspends linear narrative and sustains a durational attention that opens onto micropolitics: fleeting scenes of refuge, care, and homoerotic charge that unsettle heteronormative paradigms and rehearse alternative kinships. In foregrounding historical specificity largely absent from the novella while pushing beyond its reproductive logic, Neshat reframes the nation as a contested site of anti-colonial desire—even as the film risks legibility within global economies of orientalist visibility. The result is a situated, insurgent utopianism in which form enacts refusal: a cinema that sutures micro-utopian moments into the landscape of traumatic history