The Seed of a Sacred Art: Muhammad Rasūluf Dreams for All

Prologue

By the time Muhammad Rasūluf’s film The Seed of the Sacred Fig (2024), after making its way through multiple festivals and a few public screenings, arrived at the small, independent, and well-supported Lüneburg’s SCALA, I had assumed there would be very little left in the film to surprise me. Considering the number of interviews with Rasūluf and his cast I had watched and read, I had naively assumed we should know a lot about the film by now. This was proved otherwise. Even more was revealed to me five months later, in the summer of 2025, during a brief conversation I had with Muhammad Rasūluf in Berlin. That was when I realised that, the thought processes behind his mode of seeing is indeed the apparent reason for the ‘simple complexity’ of his storytelling. Meeting with Sitārah Malikī (Sanā – younger daughter), Mahsā Rustamī (Rizvān – older daughter), and Niyūshā Akhshī (Sadaf – classmate) also revealed the secret behind their dedication to make this impossible film possible. I wish I could interview Mīsāq Zārah (Īmān – the father and the Investigating Judge) and Suhaylā Gulistānī (Najmah – the mother) to ask about their embodiment of the dilemma of being human in the entanglement that Rasūluf’s screen foregrounds. Alas, at the time of this writing, they still remained under the scrutiny of the Islamic Republic regime. Those conversations and the analysis of audience participation, therefore shaped the structure of the present research. As they complemented the aesthetic and structural exploration of the film. Therefore, this essay aims to provide a wholesome approach towards the type of independent and underground cinema that Iranian filmmakers like Rasūluf are its pioneers.

In his unadulterated honesty, apparent in the script, the selfless acting he gets from Sitārah Malikī, Mahsā Rustamī, Mīsāq Zārah, and Suhaylā Gulistānī, the impeccable cinematography, witty and symbolic location scouting, piercing close-ups, immaculate framing, and arresting mouvement – apparent in both camera and editing, especially the final scene—Rasūluf makes the ordinary extraordinary in The Seed of the Sacred Fig. Artistic choices made by Rasūluf and his cast and crew alike—Andrew Bird (editor) and Karzan Mahmoud (composer), for example—allow for a composition that entices spectator’s curiosity, excitement, thrill, sympathy, and fear all at once. Lighting, defined by the imposed production limits –due to “illegal” shooting—next to the peeping camera that captures chilling frames while bypassing security measures, hand in hand with the well-thought-out mise-en-scène, bring the surveilled outside inside. These are as much artistic choices as they are cunning solutions to the state-imposed restrictions that Rasūluf had to resort to.

Audience Reception of the Sacred

The Seed of the Sacred Fig is a Gestalt that could easily entertain the spectator who may simply watch it for the thrill, with a touch of humanity. Yet it opens a goldmine of palimpsests of meanings and secrets to a mesmerized lover of this magic lantern, risen from the dust of a land that once was ours, with a breath of fresh air.

In December 2024, in a restored medieval building in the well-preserved medieval city of Lüneburg, a glimmer of hope emerged once again for Iranian cinema. A cinema that not only entertains but can so innately and honestly be Iranian, unapologetically ancient and contemporary at once, so near, and yet out of reach. A new chapter of Iranian cinema was being written on the silver screen. “Rasūluf has arrived”, I thought.

Both screenings I attended entertained spectators—barring four on the second night—who were entirely non-Iranian. For the 167-minute runtime, they remained engaged and impressed. The film succeeded in communicating with its foreign audience. These were spectators who had never lived under circumstances portrayed by the gripping storytelling of The Seed of the Sacred Fig. The impact was so intense that the person seated next to me on the second night experienced an involuntary seizure following the sequence of IRGC1National Counterterrorism Center (NCTC) gives the following definition of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC); “The IRGC is the Iranian state’s armed force charged with defending Iran’s regime [It is separate from Iran’s conventional military force] … The IRGC-QF is one of the Iranian regime’s primary organizations responsible for conducting covert lethal activities outside Iran, including asymmetric and terrorist operations…,” see “Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC),” Counterterrorism Guide, accessed October 29, 2025, https://www.dni.gov/nctc/terrorist_groups/irgc.html. attacks against peaceful protestors during the early days of Mahsā Jīnā Amīnī’s Woman, Life, Freedom movement in 2022.2On 16 September 2022, 22-year-old Iranian Kurdish woman Mahsā Jīnā Amīnī died in the custody of the Morality Police in Tehran, sparking a nationwide uprising that was immediately named after the Kurdish-origin slogan “Woman, Life, Freedom” (Jen, Jian, Azadi). SCALA paused the film. The patient was revived and taken to a medical facility. The pause created an opportunity to engage with the audience, revealing how deeply they had connected with the film up to that point. The screening resumed with the scene in which Sadaf, a university student and friend of Rizvān, the older daughter of the family, was revived by Najmah, the mother, who was removing lead pellets out of her blood-covered face.3These are pellets from the use of shotgun shells. Evidence of birdshot was present in the victims of attacks by IRGC during the Woman, Life, Freedom uprising. For further information, see Mahsa Alami Fariman and Ahmadreza Hakiminejad, “Woman, Life, Freedom: Revolting Space Invaders in Iran,” European Journal of Cultural Studies 27, no. 4 (August 14, 2024), https://doi.org/10.1177/13675494241268101. Sadaf, however, unlike the German spectator, was not taken to a medical facility. Later in the film, it is revealed that she was arrested by plainclothes agents. By witnessing an incident commonly experienced by Iranians, the German audience appeared visibly affected—stressed, albeit compassionately. Their sympathy was deeply moving to a Persian viewer them watching them watching the film. This moment recalled the emotional charge carried by those who have actually lived (and are still living) that story. This film is proving to be gripping in the honesty of its storytelling.

Unraveling the Gestalt: Rasūluf’s Sacred Dream

Rasūluf’s gaze onto the life of a lawyer and his family turns a deceptively ordinary domestic life into an extraordinary political power struggle between genders, mythologies, and desires, with patriarchy and tyranny at the heart of it. Īmān, the protagonist played by Mīsāq Zārah,4This is not Mīsāq’s first collaboration with Muhammad Rasūluf. He has previously appeared in Rasūluf’s films, as listed on IMDB. https://www.imdb.com/name/nm3885117, accessed September 18, 2025 is a judge at the service of the Islamic Republic penal court, assigned to death penalty cases. He is introduced in the opening sequence when leaving work and driving past a series of tall concrete walls. There is a striking similarity between this sequence and one previously seen in Rasūluf’s There Is No Evil (Shaytān vujūd nadārad, 2020).5A Golden Bear at the 70th Berlin International Film Festival in February 2020 and Sydney Film Prize at the Sydney Film Festival in November 2021. Either Īmān (who signs the execution order) is connected to Hishamt (who presses the execution button), or he is an extension of him—an evolved version of Hishmat. Either way, Rasūluf’s camera treats them in similar ways.

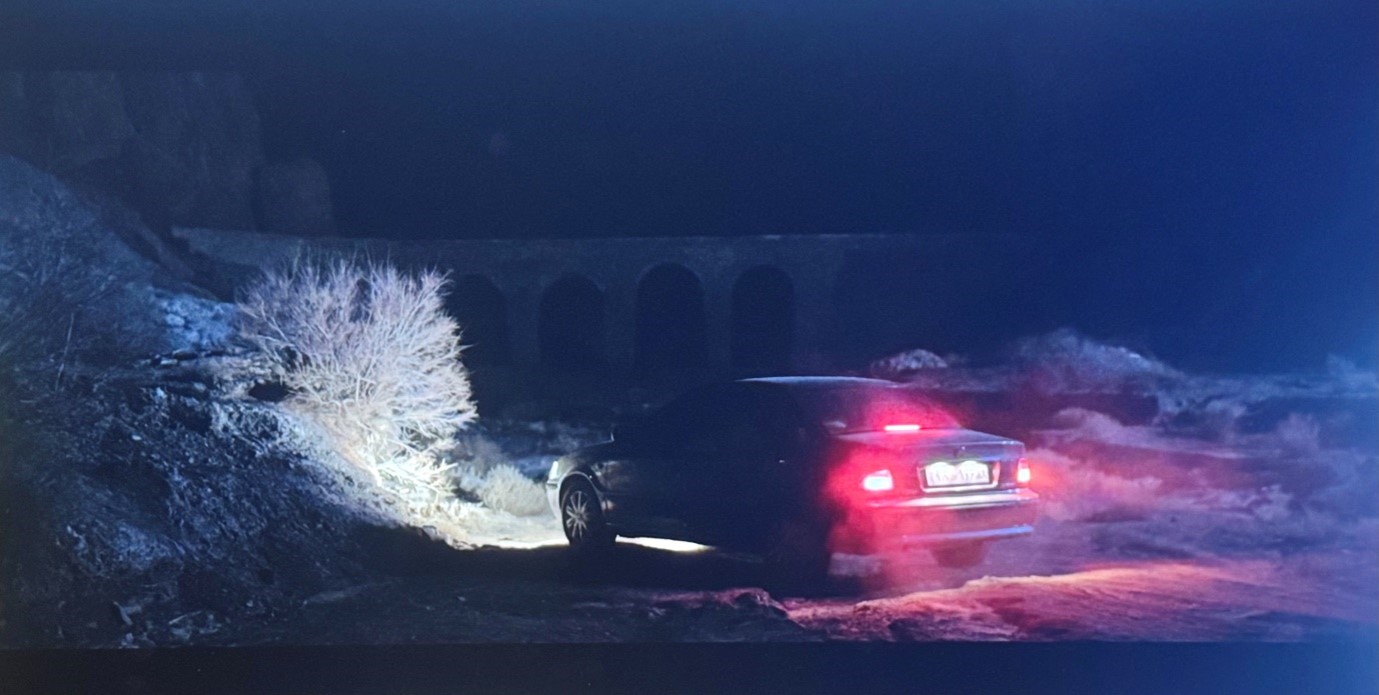

Īmān continues to meander through the city until he enters a valley in the dead of night. The close-up of his face while driving reveals a pair of kind eyes. When his car stops at the bottom of the valley, behind him looms the shadow of an ancient bridge that connects two sides of the landscape, overwhelming the dimly lit frame. On one side stands the magnificent ruins of an ancient city called Kharanaq Old Castle (also known as the City of the Sun),6

For more information, see Mojgan Aghaeimeybodi and Elham Andaroodi, “Cultural Landscape and Typology of the Khranaq Village in Iran,” Space and Form 47 (2021): 204, https://yadda.icm.edu.pl/baztech/element/bwmeta1.element.baztech-6b9c7b34-fc42-4208-bc19-a295e2bfaa96/c/DOI10_21005_pif_2021_47_E-01_Aghaeimeybodi_Andaroodi.pdf.

“Kharanaq village is located about 79 km. northeast of Yazd city, in a mountainous area at the edge of the desert […]. The primary core of this village-castle rarely has no separate governmental facilities and structures. The body of the castle which was constructed around a central core based on a coherent plan has been occupied by people for over 1,000 years. According to historical texts, this village was built in pre-Islamic periods and was first inhabited by Zoroastrians (Shahzadi,1995, 15). The existence of Chak Chak fire temple, which is one of the most famous Zoroastrian temples of Iran near Kharanaq is the evidence for this claim. The archaeological researches and findings have also proved the Sassanid foundations of Kharanaq village-castle between 2nd to 6th centuries AD.”

Kawarnaq (also spelled Xawarnagh) is the name of a Sassanid-era palace near Hira, built during the reign of Yazdigird I (399–420 CE) by the famed Byzantine architect Senemar for King Numan (403–431 CE). Beyond legends, little is known about Kawarnaq. Encyclopedia Iranica provides several references such as: “King Yazdegerd I, instructs Noʿmān to host and educate his son, Bahrām, in Ḥira. Bahrām mainly distinguishes himself in hunting. Two of his hunting exploits are painted in the hall of Ḵawarnaq at the instigation of Noʿmān’s son, Monḏer (Ṯaʿālebi, pp. 543-44).” Elsewhere in the same entry it is stated that “F. C. Andreas reconstructed old Iranian huvarna or χuvarna and interpreted it as a compound in the literal sense of ‘giving good refuge’ or ‘having a beautiful roof.” Phonetically closest to ḵawarnaq is Avestan xᵛarənah ‘glory’.” See Renate Würsch, “Ḵawarnaq,” in Encyclopedia Iranica online, accessed 29 December 2024, https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/kawarnaq/.

The significance of the location is not just being a ruin. The palimpsest of history, environment, and identity this location offers is the key point to the Gestalt that I argue is at the core of Rasūluf’s aesthetics.

which dates back to the Sassanid Empire. It serves as a reminder of the pre-Islamic Zoroastrian culture of Yazd province, where the city is located. Īmān appears insignificant in the vastness of the valley.

Figure 1: Īmān drives by prison walls. Still from The Seed of the Sacred Fig (Dānah-yi Anjīr-i Ma‘ābid), directed by Muhammad Rasūluf, 2024. 00:02:10

Figure 2: Īmān stops at the Kharanaq aqueduct bridge. Still from The Seed of the Sacred Fig (Dānah-yi Anjīr-i Ma‘ābid), directed by Muhammad Rasūluf, 2024. 00:03:18

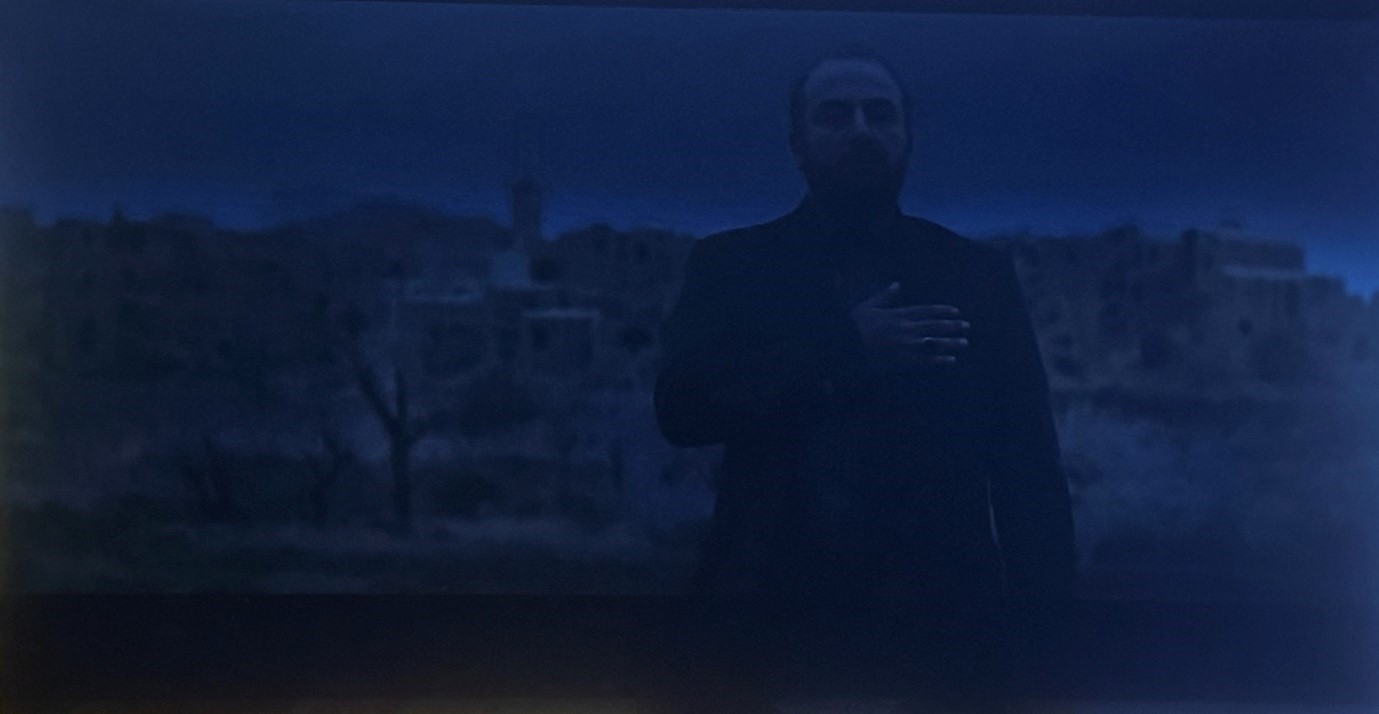

Figure 3: Īmān backs to Kharanaq facing the mausoleum. Still from The Seed of the Sacred Fig (Dānah-yi Anjīr-i Ma‘ābid), directed by Muhammad Rasūluf, 2024. 00:03:35

Figure 4: Īmān enters the mausoleum of Imāmzādah Sayyid Muhammad. Still from The Seed of the Sacred Fig (Dānah-yi Anjīr-i Ma‘ābid), directed by Muhammad Rasūluf, 2024. 00:03:44

The next long shot shows the lit windows of a newly built mosque flickering on the dark canvas of night, directly opposite the City of the Sun. The contrast is stark. A close-up of Īmān’s face holds Kharanaq in the background, as if he is standing against the ancient identity, looking only toward the new faith. Is he turning his back on what he is? The frame becomes a narrative in its own right. The following sequence shows Īmān in prayer inside the mausoleum. This valley is revisited later in the film, by which point Rasūluf’s sharp editorial choices have already cut through the palimpsest of this family, their story, and shared history.

Meandering through seemingly mundane day-to-day life of a family, the film invites spectators into a domestic life that Iranian cinema has not been able to portray since the establishment of the Islamic Republic and the formation of the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance (CIG).7

Since its establishment in 1980, CIG, according to its official website (www.farhang.gov.ir), has been responsible for enforcing a range of regulations that have effectively granted the state broad authority to impose various restrictions, surveillance, bans, and limitations on filmmaking activities. Under these regulations, any production requires a permit issued by the CIG; otherwise, it is deemed illegal. According to the official mandate:

“introducing the basis, manifestations and ideal of the Islamic revolution to world community through art, audio/visual means, books, publications, arranging of cultural gatherings and other possible activities within the country and abroad with collaboration of ministry of foreign affairs and other concerned authorities [emphasized added]… Issuing license of banning the activities of cultural, press, news, art, cinema [emphasized added], audio-visual, publications and propagation institutions in the country… Leading and supporting film making centers, script writing, movie theaters, film screening centers,… issuing licenses and withdrawing them for such institutions and foreseeing their activities. Foreseeing the cultural, art, propagation activities of expatriates residing in Iran through cooperation of other concerned authorities.” See, www.farhang.gov.ir, accessed December 29, 2024.

Throughout the film, the audience is made aware that this is a devout family, adhering not only to Islamic practices, but also to the laws instituted by the Islamic regime. Yet, for the first time, spectators see the three women (the mother and two daughters) at home without headscarves. We see them as they are, within the privacy of their home. We see the daughters doing their nails, listening to music, hanging out with their friend, like any other teenagers.

Figure 5: Breakfast. Still from The Seed of the Sacred Fig (Dānah-yi Anjīr-i Ma‘ābid), directed by Muhammad Rasūluf, 2024. 00:08:35

Figure 6: Mother, daughters and their friend, doing their nails and eyebrows. Still from The Seed of the Sacred Fig (Dānah-yi Anjīr-i Ma‘ābid), directed by Muhammad Rasūluf, 2024. 00:20:14

The spectator lives with them as they go through their ordinary day-to-day lives. Their public appearance in full Islamic hijab is contrasted with how they live in private, a lived dichotomy. This image in itself, other aspects of the filmmaking aside, is a breath of fresh air. This truth on the Iranian screen has not been seen for the past forty-five years. Simply for this, and for showing what is real; the embedded contrast in the ordinary, this honest domestic scene, Rasūluf and his crew took life-threatening risks. This is an aspect entirely strange and intangible to non-Iranian viewers and filmmakers who are not familiar with the duality of this profession. Domestic honesty had rarely found a suitable cinematic frame in Iranian cinema. Even in Hamoun (Hāmūn, 1989), Mihrjūyī had to resort to showing Bītā Farrahī, playing Mahshīd with her head covered by a large white bath towel—implying she had just washed her hair. Working with such limiting regulation that is imposed on Iranian filmmakers, Kiyārustamī famously stated that he prefers to avoid domestic private scenes because he refuses to let his camera lie.8Ali Akbar Mahdi, “In Dialogue with Kiarostami,” The Iranian, August 25, 1998, accessed December 29, 2004, https://www.iranian.com/Arts/Aug98/Kiarostami/; See also, Geoff Andrew, interview with Kiarostami, “Abbas Kiarostami,” The Guardian, April 28, 2005, accessed December 29, 2024, https://www.theguardian.com/film/2005/apr/28/hayfilmfestival2005.guardianhayfestival.

Rasūluf does not stop there. He did not seek official CIG permission for shooting the film. Within the first thirty minutes, it becomes apparent to the spectator that this group of brave artists—cast and crew included—decided to take serious risks for their collective artistic endeavour.

In a video released soon after leaving Iran, Rasūluf briefly explained his decision and the future he had envisioned for the film. In a series of subsequent interviews, he provided more details about the process of making this “underground” film and the conscious decisions he and his cast and crew made, fully aware of the potential consequences. On May 13, The Hollywood Reporter published a report with a full statement by Muhammad Rasūluf:

…actors and agents of the film are still in Iran and the intelligence system is pressuring them. They have been put through lengthy interrogations. The families of some of them were summoned and threatened. Due to their appearance in this movie, court cases were filed against them, and they were banned from leaving the country. They raided the office of the cinematographer, and all his work equipment was taken away. They also prevented the film’s sound engineer from traveling to Canada. During the interrogations of the film crew, the intelligence forces asked them to pressure me to withdraw the film from the Cannes Festival. They were trying to convince the film crew that they were not aware of the film’s story and that they had been manipulated into participating in the project.9Maya Galuppo, “Dissident Iranian Filmmaker Rasoulof Flees Country: ‘With a Heavy Heart, I Chose Exile’,” The Hollywood Reporter, May 13, 2024, accessed December 29, 2024, https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/news/general-news/mohammad-Rasoulof-flees-iran-cannes-1235897525/.

It is not merely the decision to forgo the official permission that makes Rasūluf’s decision noteworthy. The Seed of the Sacred Fig is also uncensored. Rasūluf, in addition to bypassing the constraints of mandatory hijab, exercised the freedom to tell his story as he envisioned it, as he intended it, and as he wished it to be seen. The film joins a select few pioneer in Iranian cinema, where women can finally see the light of the projector without a head cover or the blade of censorship. Films produced with official approval and under the supervision of a representative from CIG are subject to state censorship and, consequently, are inevitably altered. This is a topic that warrants its own dedicated space beyond the scope of the present study. Nonetheless, the film is filled with symbolic and lyrical notions, this time serving the storytelling rather than functioning solely as a means of circumventing state-imposed regulations.

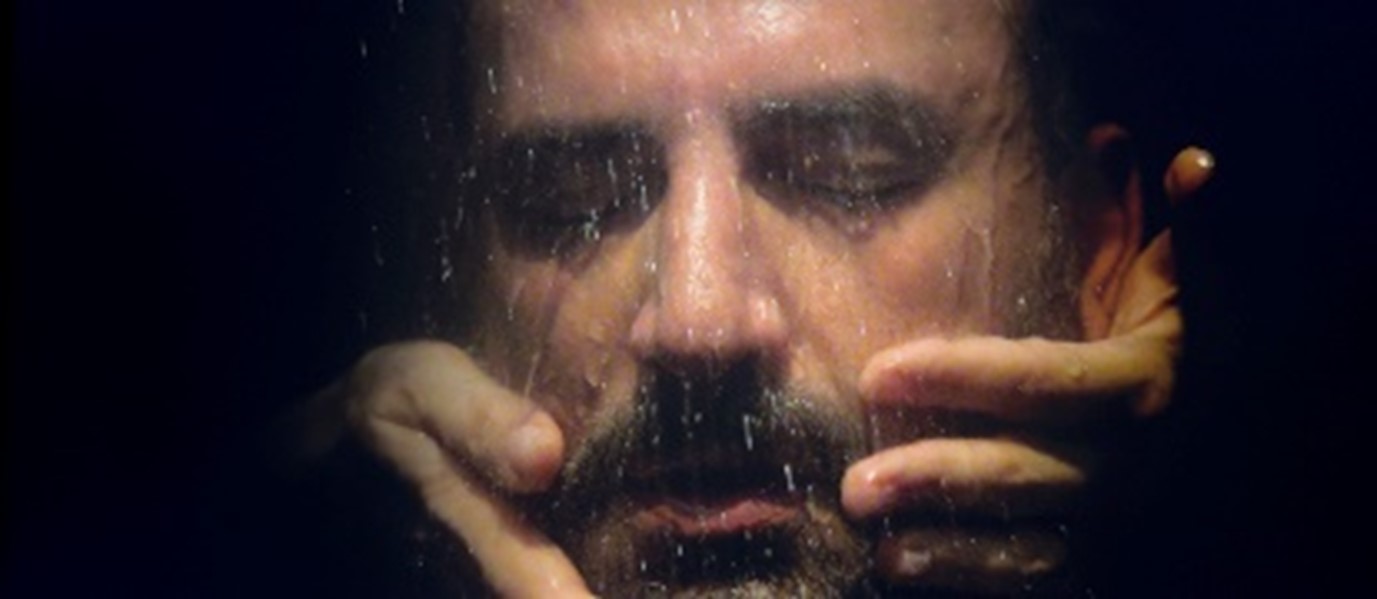

Upon Īmān’s arrival home, the camera follows his wife into their bedroom as she brings him a tray of bread and cheese, prepares morsels for him, and feeds him while sitting together on the bed, in a medium shot of a tightly arranged mise-en-scène. As they talk about Īmān’s promotion to Revolutionary Court Investigating Judge, he reveals a handgun assigned to him for protection. Najmah expresses discomfort with it. Īmān places the gun in the drawer of the bedside table. There is love and affection in their look, emphasised by the warm lighting of the mise-en-scène. The spectator learns learn about their dreams of moving into a three-bedroom apartment, where the two daughters could each have their own room. The desire for that which could be had signals a lack. That lack represents something that Īmān had to work hard to get closer to. The tenderness in Najmah’s acting foregrounds the notion of desire slightly stronger.10There are numerous tightly-designed frames that show them in very intimate settings, including a shower scene that shows her hands on his face and hair, supposedly trimming his hair and beard. Besides the symbolically sensual nature of these frames, their appearance on the screen of an Iranian film, written, directed, acted and shot by Iranian artists, make them even more significant. Suhaylā Gulistānī and Mīsāq Zārah delicately portray this loving couple, at this intimate moment, with an acting that is as “true” as Najmah’s uncovered hair, when she is sitting next to Īmān, tending to him.

Figure 7: Najmah puts Īmān to bed. Still from The Seed of the Sacred Fig (Dānah-yi Anjīr-i Ma‘ābid), directed by Muhammad Rasūluf, 2024. 00:07:48

Figure 8: Gun in bedroom, between Najmah and Īmān. Still from The Seed of the Sacred Fig (Dānah-yi Anjīr-i Ma‘ābid), directed by Muhammad Rasūluf, 2024. 00:06:30

Figure 9: Close-up of the Gun. Still from The Seed of the Sacred Fig (Dānah-yi Anjīr-i Ma‘ābid), directed by Muhammad Rasūluf, 2024. 00:06:38

Yet there is a gun in their privy. Rasūluf leads the audience through dialogues he has written for Najmah and Mīsāq to realize that the gun is necessary for their protection. This notion of “protection” keeps coming back in upcoming dialogues. Īmān’s colleagues, too, remind the spectator of this a few more times through the film. Nonetheless, cutting between Najmah’s worry face and the close-up of the gun turns it into a third person in their bedroom. The Desire that has always been allegorically and symbolically shown in a rather cloak-and-dagger storytelling style, is now unapologetically seen on the screen of Rasūluf. He, Suhaylā, and Mīsāq have dared, and dared openly.

Figure 10: Najmah and Īmān in bed planning their future. Still from The Seed of the Sacred Fig (Dānah-yi Anjīr-i Ma‘ābid), directed by Muhammad Rasūluf, 2024. 00:37:16

Figure 10-a: Najmah washes Īmān. Still from The Seed of the Sacred Fig (Dānah-yi Anjīr-i Ma‘ābid), directed by Muhammad Rasūluf, 2024. 00:57:50

Dialogues written for Īmān and Najmah are meant to reveal the trust they have in each other, foregrounding their close relationship. Their comfortable acting captured in a series of medium close-up frames, shot in a bedroom set, lit with a warm color composition and always with an alarming red bedside lamp, complement Rasūluf’s layered symbolic storytelling. The audience learns about their secrets and lies, hopes and ambitions, as well as their internal conflicts, through sequences shot in that same bedroom. Īmān, as previously seen at work in the courthouse, is going through a personal conflict, struggling between his ethical convictions and what is asked of him as a Revolutionary Court Investigating Judge. His predecessor lost his job due to some such similar conflicts. He discusses this with Najmah. She wants that three-bedroom flat. The theme of desire claims a presence in most bedroom scenes. The “desire” always justifies their moral conflict.

Evil Has Arrived

Īmān is compelled to sign an execution order hastily, without reviewing the convict’s file. This dilemma is shared with his superior—a friend, apparently—across a series of sequences: Īmān walks through a prison corridor lined with life-size cardboard cutouts of Qāsim Sulaymānī on both sides,11Qāsim Sulaymānī was killed on January 3, 2020, at Baghdad International Airport. Alongside him, the Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF) deputy commander, ‘Abū Mahdī al-Muhandis, and five others were also killed when a U.S. launched missiles at their convoy. Sulaymānī was an Iranian major general and commander of the Quds Force (1997/98–2020), a branch of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) responsible for IRGC foreign operations. while a line of prisoners in blue-striped uniforms passes behind him. Upon entering the office of his colleague Qādirī and protesting the legality of the order, Rizā Akhlāqīrād is introduced, seated against a wall covered with images of Khāmanah’ī12‘Alī Khāmanah’ī, the current leader of the Islamic Republic. and other figures of the Islamic Republic, all shown in a tightly framed medium shot. A close-up of their engaged faces cuts to an extreme close-up of a table calendar on which Qādirī writes: “bugged”.13The Seed of the Sacred Fig, directed by Muhammad Rasūluf (France, Germany, Iran, 2024), 00:12:05. This leads into a sequence of reverse medium shots of Qādirī and Īmān, presumably in the prison canteen, where Qādirī informs Īmān that refusal to sign would cost him his position, as it did his predecessor. Īmān is framed within lines of rods and the blurred forms of barred doors and windows behind him.

Figure 11: Īmān at Qādirī’s office. Still from The Seed of the Sacred Fig (Dānah-yi Anjīr-i Ma‘ābid), directed by Muhammad Rasūluf, 2024. 00:11:25

Figure 12: Īmān at the canteen. Still from The Seed of the Sacred Fig (Dānah-yi Anjīr-i Ma‘ābid), directed by Muhammad Rasūluf, 2024. 00:13:09

The shot is powerfully symbolic, particularly when juxtaposed with intimate conversations between Najmah and Īmān about the three-bedroom government housing or the dishwasher that Najmah requests so innocently. “Desire begins to take shape in the margin in which demand rips away from need.”14Jacques Lacan, “The Subversion of the Subject and the Dialectic of Desire in the Freudian Unconscious,” in Écrits, trans. Bruce Fink (New York: W. W. Norton, 2006), 689. Lacan calls this object objet petit a that is the unattainable object-cause of desire. In other words, the leftover of the real that cannot be symbolized. This “margin”, both literally—as in the bedside drawer—and theoretically, is the one, the presence, that demands something, by opening up “the guise of the possible gap need may give rise to.”15Jacques Lacan, “The Subversion of the Subject and the Dialectic of Desire in the Freudian Unconscious,” in Écrits, trans. Bruce Fink (New York: W. W. Norton, 2006), 689. Dialectically, the gun—its location, its disappearance, and the pseudo-need to justifying its presence—foreshadows the crack that shall eventually become the hole swallowing Īmān at the end.

That twenty-year-old man’s death sentence is signed. Īmān suffers under the weight of his moral dilemma. Observing the German audience at the Lüneburg’s Scala, unfolded a moment of unsettling complexity. Against the power of skilful filmmaking, it becomes possible for the execrator to feel a degree of sympathy for this troubled judge. But only just. He is not yet fully evil. Najmah too, in her absolute trust, belief, and support, justifies his decision. She reminds him of the promised three-bedroom apartment. They must now be more vigilant, given the importance of protecting his position. She becomes his minion in exerting control over their daughters at home. The desire reigns.

Īmān’s character bears an uncanny resemblance to the protagonist in the first episode of Rasūluf’s There Is No Evil. In thirty-three minutes, Hishmat is portrayed as a caring husband, father, and son, a good neighbor, and someone who is attuned to gender-based social injustices (as illustrated in his conversations with his wife in the car). He even dyes his wife’s hair in preparation her for an upcoming wedding.16Najmah does this in The Seed of the Sacred Fig in a minimalist and deeply sensual sequence that suggestively stands in for a love-making scene. The fact that his wife and daughter wear their head coverings loosely also signals that he is a seemingly ordinary man, free from any religious prejudice. The spectator perceives him as kind. Yet he, too, emerges from depths of an underground parking garage to navigate the city during the day, only to return to that Hades, where it is revealed that he is, in fact, an executioner—a chilling revelation for the spectator. Like Īmān, he drives past imposing concrete prison walls, while traffic and streetlights reflect on his face. Hishmat, unlike Īmān, stares at flickering green and red lights of a pharmacy or traffic light near the prison, on his way to work at the crack of dawn. He appears numb, lifeless, and dissociated. Īmān though, turns his back to any alarming signs: his ancient identity, or the warnings of his conscience, surrounded by bars, door frames, and closed windows at his work. Rasūluf arranges his mise-en-scène meticulously, to show how Īmān has become an evolved version of his former protagonist. Evil has arrived.

Īmān’s Lacanian tragic fall is justified through the Aristotelian arc of Rasūluf’s character building, that transforms from a paranoid government judge to a detached father, from a loving husband with full trust in his wife to a monster who becomes the prosecutor and prison guard of his own family, to become a creature who is consumed from within by the desire—symbolized by the gun and its disappearance—which informs his fear and mistrust. His downfall is thus justified.

The gun in The Seed of the Sacred Fig becomes Īmān’s objet petit a—it is the symbolic authority and paternal protection. The missing gun destabilizes Īmān’s authority His position fractures. Īmān’s obsessive interrogation of his family—searching their phones, turning them against one another, coercing confessions—reveals his identification with the regime, now displaced onto the domestic space. He invokes the symbolic order of the state power through patriarchal policing. What is out there is in here now. The boundary has collapsed, as Lacan points to the symbolic failure of order, and how what was assumed “real” or true, slides into psychosis. “The Lacanian object a” [the gun] is “that which causes [the notion of] desire… it is the pure semblance, the empty place which designates the structural lack.”17Slavoj Žižek, “How Did Marx Invent the Symptom?” in The Sublime Object of Ideology (London: Verso, 1989), 87–93. The fear that informs Īmān’s erratic behaviour—resorting to his colleague’s interrogation of mother and daughters—as the signifier of lack of power, is defined by the missing gun (objet petit-a / the object cause of desire).18Jacques Lacan, “The Subversion of the Subject and the Dialectic of Desire in the Freudian Unconscious,” in Écrits, trans. Bruce Fink (New York: W. W. Norton, 2006), 689.

The chorus of the three women leading to Īmān’s downfall also functions symbolically, representing three generations and their respective relationships to the ideologue, the patriarch, the oppressor into which Īmān has transformed. His ultimate undoing, however, comes at the hands of the youngest, the one who steals the object that embodies desire, the symbol of what is lacking, the power that is drifting away. “The objet a is, so to speak, the embodiment of the lack, the positivization of a void around which desire turns.”19See above Slavoj Žižek, “How Did Marx Invent the Symptom?” in The Sublime Object of Ideology (London: Verso, 1989). This is a film with a strong script which needed other elements of filmmaking to come together to turn the magic lantern on. Hence the necessity of making it without any interference from CIG.

So far, Rasūluf’s film has proved to fit the golden parameters of Aristotelian tragedy in its plot, characters, and thoughts/psychology that lead the plot to the fall and, the climax of the story. What is left to unravel is rhythm, what the Greeks called music, and I call the mouvement–in both camera and editing. It is often said that those in the performing arts are resourceful, and so too are Rasūluf and his cinematographer, Pūyān Āqābābā’ī, whose work would determine the challenges that Andrew Bird, the editor, could expect on the editing table. “They move from the very confined space of the apartment in Tehran to the outside world,” Andrew recalls, “but it’s ultimately an equally confined space in this garden, in this house, and even in the ruins where they end up at the end of the film.”20Jillian Chilingerian, “The Seed of the Sacred Fig–Interview with Editor Andrew Bird,” Offscreen Central, January 3, 2025, accessed March 30, 2025, https://offscreencentral.com/2025/01/03/the-seed-of-the-sacred-fig-interview-with-editor-andrew-bird/. The Seed of the Sacred Fig Tree was not the first time he collaborated with Rasūluf. Speaking on the conditions of editing the film in secret he commends and testifies that what held this film together was the immense sense of trust existing in the entire group. The exact lack of which brought the downfall of Īmān. “I was constantly amazed at the thought of how trust works between people,” Andrew comments.

How to Shoot a Sacred Film?

This is not Rasūluf’s first “underground” film. He is also banned from any filmmaking activities based on previous sentences he had received.21“Before being forced into exile, I was already banned from working,” Rasūluf said in an interview with Deadline. Zac Ntim, “Mohammad Rasoulof on His “Anguishing” 28-Day Journey to Escape Iran,” Deadline, May 23, 2024, accessed March 15, 2025, https://deadline.com/2024/05/mohammad-rasoulof-the-seed-of-the-sacred-fig-cannes-iran-germany-1235928308/. Therefore, the traditional route of working with a producer, open auditions and the like does not apply here. Between the interior, exterior, and car sequences, shooting involves varying degrees of complexity, knowing this is an “underground” production. “Whenever the location allowed, I would come on set. It really depended on the location. But I directed often from a certain distance, without being physically present,” Rasūluf tells The Interview Magazine.22Daniel Schindel, “How Director Mohammad Rasoulof Made One of the Year’s Defining Films in Secret,” Interview Magazine, December 3, 2024, accessed March 30, 2025, https://www.interviewmagazine.com/film/how-director-mohammad-rasoulof-made-one-of-the-years-defining-films-in-secret. Car rides are nuanced by sparingly used location shots of the streets of Tehran-a cunning move to bypass surveilling eyes of the authorities. Rasūluf has proven a formidable storyteller with car rides. Agnès Varda occasionally uses the car as a platform for looking outward, not inward. For example, in Les Glaneurs et la Glaneuse (2000), she films roadside scenes from inside the car, using it as a mobile frame for personal reflection. For both Varda and Rasūluf, the car becomes a cinematic lens on the world, viewed by the protagonist (Hishmat staring at the flickering pharmacy sign. Īmān’s paranoia of the motorcyclist following him). He stages conversations there to which he draws his viewer’s attention (revealing intimate, warm and kind family relations, as oppose to Najmah’s with Fātimah in a car that eventually leads to their interrogation at an IRGC’s safe house). What distinguishes Rasūluf as a remarkable filmmaker is the condition under which he creates his film. “There was another problem with making the film in a clandestine way; you have to make everything very quickly or you get exposed” he adds.23Daniel Schindel, “How Director Mohammad Rasoulof Made One of the Year’s Defining Films in Secret,” Interview Magazine, December 3, 2024, accessed March 30, 2025, https://www.interviewmagazine.com/film/how-director-mohammad-rasoulof-made-one-of-the-years-defining-films-in-secret. Yet the precision he is after (and often manages to produce) speaks to well-rehearsed scenes and well-thought-out mise-en-scène. We can see this in the frame compositions of Rasūluf’s films.

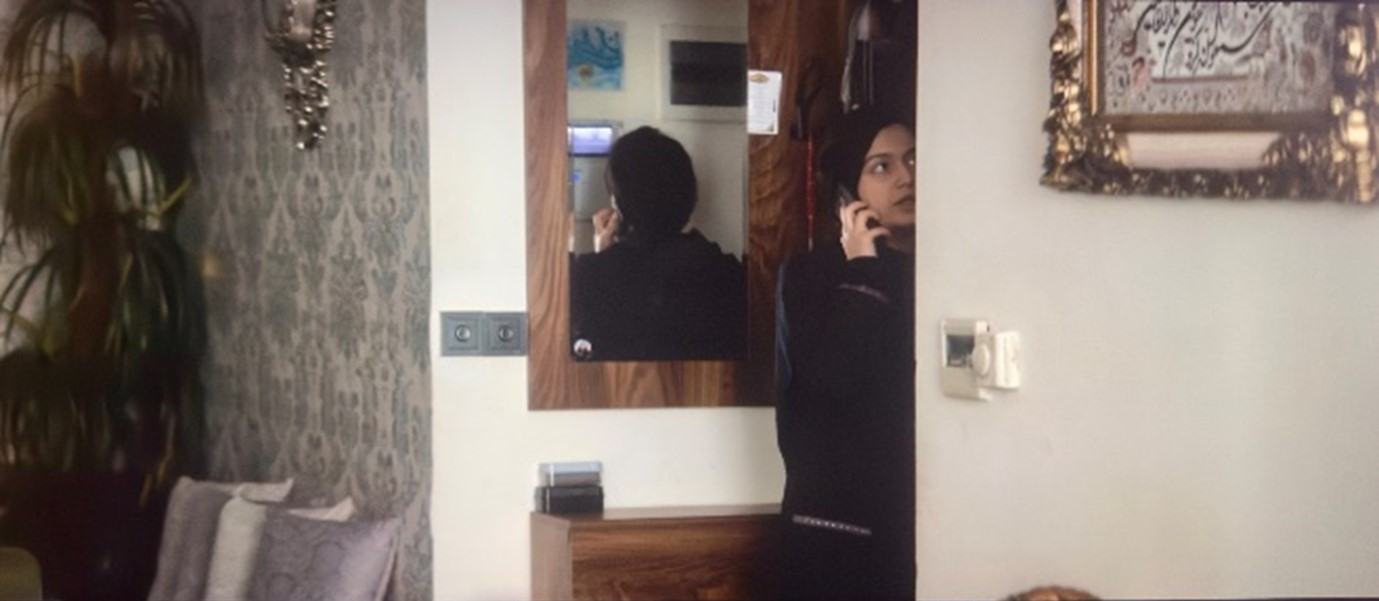

The composition of frames makes the viewer an accomplice in this covert operation, especially in some of the well-thought-out interior sequences. One of the best examples is at the beginning of the rising tension of the film when the spectator, as dose the camera, peeps through a narrow opening of a window half-covered by a curtain, watching Sadaf being led to cross the street by Rizvān. Quick-witted Sanā fakes menstrual pain to send her mother on a fool’s errand to fetch some pads from the pharmacy. In a series of well-edited sequences, along with Sanā, we/camera secretly look through the railings, the bars and half-open windows to sneak in the girls. We, the crew, and Rasūluf avoid being caught by the authorities. This is a palimpsest of vison and feeling, collapsed through time, cinematography, and the realities of underground filmmaking in precarious times. The secretly placed camera leads us into the vision-world of Rasūluf’s dream. ‘Secretly looking’ creeps into the imaginary of the viewer.

Figure 13: Sanā spying on her mother. Still from The Seed of the Sacred Fig (Dānah-yi Anjīr-i Ma‘ābid), directed by Muhammad Rasūluf, 2024. 00:45:43

Figure 14: Sanā keeping an eye on Sitārah and Rizvān. Still from The Seed of the Sacred Fig (Dānah-yi Anjīr-i Ma‘ābid), directed by Muhammad Rasūluf, 2024. 00:46:01

Figure 15: Sadaf and Sanā through the opening of the stairway. Still from The Seed of the Sacred Fig (Dānah-yi Anjīr-i Ma‘ābid), directed by Muhammad Rasūluf, 2024. 00:46:26

Eventually, the mother has to be let in, and what follows is a series of medium to extreme close-up shots of her hands treating Sadaf’s wound. An extreme close-up of her hand holding a tweezer—the same hand that earlier was plucking her daughter’s eyebrows with the same tweezer—now removes bloodied pellets out of Sadaf’s face. The music score is a Kurdish tune. Mahsā Jīnā Amīnī was a Kurdish girl. It is not revealed whether Sadaf is from Kurdistan or not. We cannot tell. Like Mahsā, she is not from Tehran and now cannot go back to the dormitory, for she might be abducted by the plainclothes agents. Najmah, in fear of the threat Sadaf’s involvement in protests may cause to their security, does not agree to her stay. Previously in the film, when Sadaf first came to their house, Najmah had reluctantly agreed to let her stay for the night, but hidden in the girls’ already small bedroom, when Īmān comes back home. By then secrets had already begun to grow, and so had the divide between the girls, their mother, and Īmān. Abandoning Safad seems to have widen the gaping hole of chaos that would eventually engulf them. The threat of the outside is now inside their domestic space. The sense of house arrest creeps in. As the divide expands, Rasūluf’s Aristotelian ascend towards the climax begins.

Figure 16: Pellets. Still from The Seed of the Sacred Fig (Dānah-yi Anjīr-i Ma‘ābid), directed by Muhammad Rasūluf, 2024. 00:51:29

Amidst all these secrecies, one morning Īmān cannot find the gun. His mental anguish plays out through a series of sequences that follow. Editing of the sequences that show his searches and interrogations of his own flesh and blood allow a visible change to the mouvement of the film and with it the psychology of it too.

At the 77th Cannes Film Festival press conference,24Festival de Cannes, “The Seed of the Sacred Fig by Mohammad Rasoulof – Press Conference,” Festival de Cannes, May 25, 2024, accessed March 25, 2025, https://www.festival-cannes.com/en/medialibrary/the-seed-of-the-sacred-fig-by-mohammad-Rasoulof-press-conference/. Mahsā, who plays Rizvān, the older sister, speaks about the tension they would experience during the few months of intense shooting. She recalls a day, when they were warned the regime agents might be nearby and they needed to strike the set. Her immediate worry was not for her own safety, but rather for the completion of the film project. For, she too has been amongst many brave women participating in the Woman Life Freedom uprising who, as a result have been attacked and were injured. That is the fierce energy she brings into her acting when interrogated by her own father in their ancestral rural house near Kharanaq. Sitārah, who plays Sanā, the younger sister, stated in the same press conference that when she was offered a role in a clandestine project, with no knowledge of the director or other details, she accepted without question. In a conversation held in Berlin, she shared with me that she had already decided not to accept roles that would force her to lie in front of the camera by submitting to an imposed head covering. Both women embody courage rarely seen before Woman Life Freedom movement. When Rasūluf directs them undercover, from a distance, often not on location, what he directs is a convergence of immense energy, will, enthusiasm, and might, made possible by a single force: trust. The trust in each other, in the art, in the project, in the future of Iranian cinema, and in their director, made the impossible possible. This stands in stark contrast to the world of Īmān and what he represents, a universe governed by mistrust and fear.

In the cinema hall in Lüneburg, the spectators around me sat at the edge of their seats, while I frantically took notes in the dark. Rasūluf had kept them in constant anticipation; he is a classic filmmaker, I told myself, while listening to the Kurdish music moving the scene forward. Karzan Mahmood’s sensitive choice of music has already earned him a nomination for “Best Original Score – Independent Film (Foreign Language)” by the 15th Hollywood Music in Media Awards.25He lost it to A.R. Rahman, an extremely formidable contender. Losing to him is an honour in its own right. In a conversation we had, Mahmood explained the meticulous process of composing the sound for the film, in addition to selecting the music.26Based on a personal conversation with Karzan Mahmood, conducted by the author in Berlin, June 2025. He too had to work in relative secrecy over a few weeks, communicating with Rasūluf or his team by virtual means. He also spoke of the trust and mutual understanding that had already been established between them.

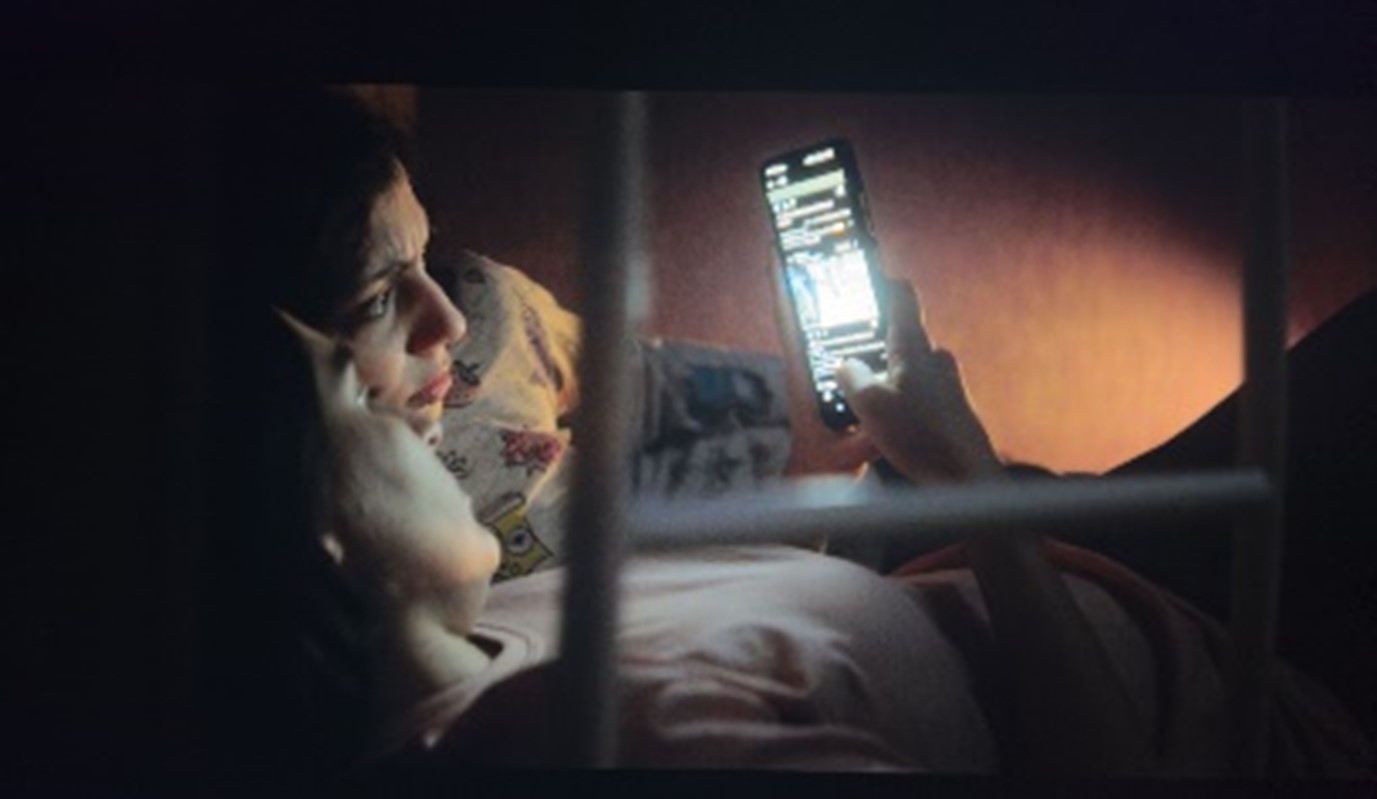

In tightly composed frames, two sisters are shown watching the events of Mahsā’s movement unravelling on the streets of Iran on their phones. The light from the screen of their mobile phone illuminates the close-up of their faces. They are watching in secret, at home, in their bedroom, away from the prying eyes of Najmah and Īmān. As protests escalate, Rizvān and Sanā consume protest footage via social media—immersing themselves in the Real that Īmān cannot integrate.

Figure 17: Sisters watching protest footage on a mobile phone. Still from The Seed of the Sacred Fig (Dānah-yi Anjīr-i Ma‘ābid), directed by Muhammad Rasūluf, 2024. 01:01:16

Figure 18: Sisters watching protest footage on a mobile phone. Still from The Seed of the Sacred Fig (Dānah-yi Anjīr-i Ma‘ābid), directed by Muhammad Rasūluf, 2024. 01:01:22

Īmān projects imagined enemies onto his daughters: he envisions them complicit with protestors, even picturing his eldest daughter driving a car with her hair uncovered,27Roxana Hadadi, “Review: ‘The Seed of the Sacred Fig’ Wants You to Be Furious,” Vulture, November 27, 2024, accessed October 29, 2025, https://www.vulture.com/article/review-the-seed-of-the-sacred-fig-wants-you-to-be-furious.html. makeup, and tattoos—symbols of defiance. These projections fracture the imaginary unity of the patriarchal family, rendering the daughters as uncanny doubles. Alongside the girls, spectators watch actual footage of the uprising. Andrew Bird’s navigation through 400 different clips seems to have led to a decisive choice made on behalf of non-Iranian viewers: “We didn’t want [the film] to feel like a film that was shot under the circumstances it was being shot in, and I proposed using these [clips] when the girls are in the room and they’re looking at their cell phones using that as a kind of springboard to moving into the original footage that they were watching.”28Jillian Chilingerian, “The Seed of the Sacred Fig–Interview with Editor Andrew Bird,” Offscreen Central, January 3, 2025, accessed March 30, 2025, https://offscreencentral.com/2025/01/03/the-seed-of-the-sacred-fig-interview-with-editor-andrew-bird/?utm_source=chatgpt.com.

In a series of conversations I held with Rasūluf on the topic, he explained the meticulous care he took to direct Bird for this part of the film.

The idea of using documentary footage came to me while I was writing the screenplay. I was telling the story of a family whose life had been disrupted by public protests. But the question was: how could I, while making an underground film, go out into the streets and recreate scenes of those protests the way I wanted? That was impossible. So, I thought of using real documentary videos instead.

I told Andrew that we already had this footage; we could include it during editing, and if the result didn’t feel right, we would remove it. At first, I thought the limitations of underground filmmaking were reason enough to use documentary footage. But later I realized that the power of reality in these images is something that simply cannot be recreated—and that turned out to be the more important point.29From personal conversations with Muhammad Rasūluf (messaging, email and interview), 2025.

This seems to have allowed Andrew Bird “to choose elements from those clips that maybe have a more universal feeling to them…an awareness”30Jillian Chilingerian, “The Seed of the Sacred Fig–Interview with Editor Andrew Bird,” Offscreen Central, January 3, 2025, accessed March 30, 2025, https://offscreencentral.com/2025/01/03/the-seed-of-the-sacred-fig-interview-with-editor-andrew-bird/?utm_source=chatgpt.com. that he claims to have brought into the editing process as a viewer from the West who may not be fully familiar with the background culture.

Exterior shots are limited in the first two-thirds of the film. Besides the car sequences with Najmah, navigating tight and congested city streets and alleyways, when the camera is installed in the interior of the car, capturing reverse shot of the passengers against the backdrop of the streets, there are only a handful of scenes in which the camera, and along with it the spectator, looks out onto the streets. Going through a randomly normal day of their life, the camera follows the girls walking down the street after getting fitted for their school uniforms at the local tailor, chatting with the woman about the chest measurements. When Sanā, Rizvān, and her classmate Sadaf next appear on the streets in a long shot—not quite a crane shot—we can still hear their chatter continuously, observing them losing themselves in a crowd of passers-by and cars. And I wonder where the cameraman was hiding to shoot the scene, safely, without the risk of giving away the cover of an underground film. The transition in the sequence is seamless, which says a lot about the critical work of the sound department.

Moving from urban to suburban, from the contemporary to antiquity, from modern interiors to rustic rural locations, juxtaposes the accidental discovery of the garden shed. That is when after Sanā runs away from the dungeon of this newly risen domestic menace, the dictator-patriarch, Īmān, she finds old cassette tapes of Marziyah31Marziyah (née Khadījah Ashraf al-Sādāt Murtazā’ī), a famous and popular Iranian traditional singer, 22 March 1924 – 13 October 2010. and Qamar32“Qamar’s first formal performance as a vocalist took place at Tehran’s Grand Hotel in 1924. The first public appearance of a Persian female vocalist without the obligatory veil (ḥejāb) signalled an immensely significant development in Persian music. It was an event that set a precedent and affected the musical life of future generations of Persian female vocalists prior to the Revolution of 1979 and eventual establishment of the Islamic Republic of Iran.” See Erik Nakjavani, “QAMAR-AL-MOLUK VAZIRI,” Encyclopaedia Iranica online, accessed February 3, 2025, www.iranicaonline.org/articles/qamar-vaziri/. next to Ta‘ziyah props, all belonging to her grandfather. She designs a sound trap filled with memories of the past. It is the editing and the work of the sound department that turns this garden sequence into a chilling pivotal scene. In There Is No Evil, the spectator must travel to the underground to uncover the truth about Hishmat. In The Seed of the Sacred Fig, Rasūluf takes us to the past, to the pre-Islamic, to antiquity, to Kharanaq of the Sassanids, to our past, to where it all began. The tension is the same and Rasūluf’s aesthetic choices attest to it. Andrew Bird’s editing is as layered as the palimpsest of history at the location where the film ends. With Īmān’s fall, women inhabit Kharanaq, once again.

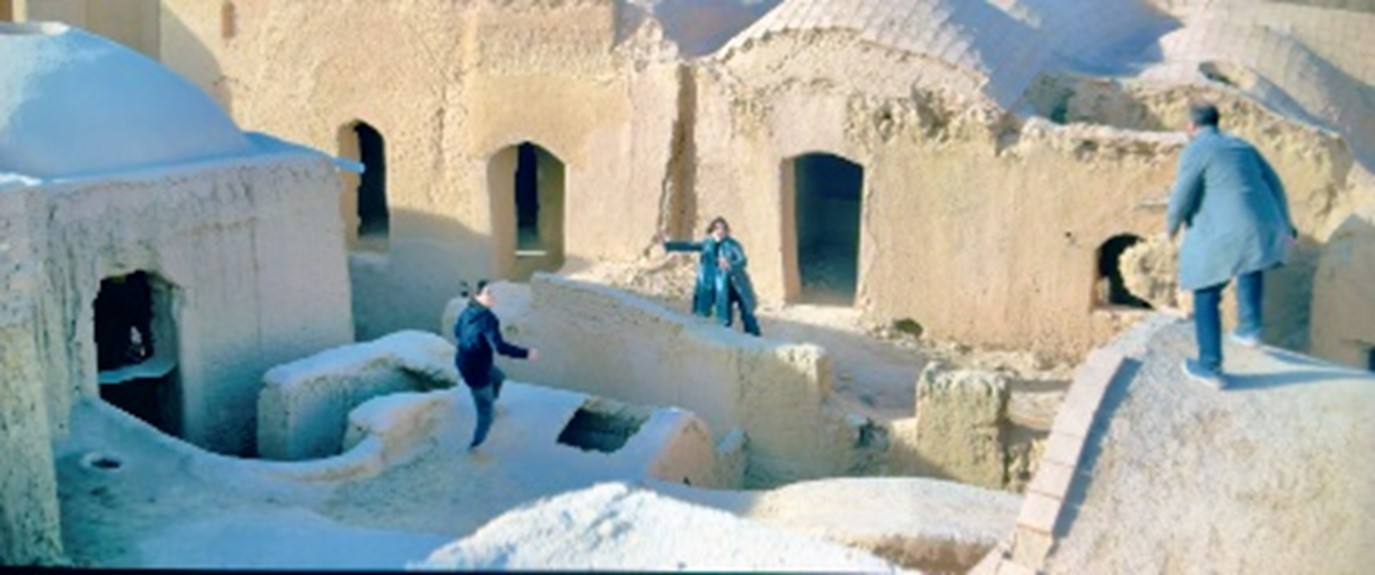

At the climax, Sanā raises the gun at her father but shoots the ground beneath his feet. This hesitation captures Lacan’s idea that jouissance risks the destruction of the symbolic father, yet dilemmas emerge when that symbolic rupture threatens the symbolic order entirely.33Jacques Lacan, “The Subversion of the Subject and the Dialectic of Desire in the Freudian Unconscious,” in Écrits, trans. Bruce Fink (New York: W. W. Norton, 2006), 689–728. Her action collapses the fig metaphor. Rasūluf notes that filming in the ruins was one of the most challenging parts of the shoot. The crew’s extended presence at the site was beginning to attract attention from locals, increasing the risk of discovery. Mindful of the sanctity of the site and to avoid any damage to the ruins, he decided to build a fake roof for the final scene. Rasūluf tells me that since they had no stunt actor, Mīsāq chose to perform the stunt himself. This meant that the scene could only be shot once, and it had to work perfectly, so that the crew could wrap and leave immediately.

Figure 19: Īmān chases his family at the ancient ruins of Kharanaq. Still from The Seed of the Sacred Fig (Dānah-yi Anjīr-i Ma‘ābid), directed by Muhammad Rasūluf, 2024. 02:39:04

Figure 20: Īmān drags Najmah over the ruins. Still from The Seed of the Sacred Fig (Dānah-yi Anjīr-i Ma‘ābid), directed by Muhammad Rasūluf, 2024. 02:40:11

Figure 21: Sanā aims at Īmān. Still from The Seed of the Sacred Fig (Dānah-yi Anjīr-i Ma‘ābid), directed by Muhammad Rasūluf, 2024. 02:40:49

Rasūluf’s film choreographs the collapse of the symbolic through patriarchal paranoia, trauma, and female jouissance. The missing gun operates as objet petit-a; protest footage invokes the traumatic Real; the daughters’ rebellion challenges patriarchal authority. The film is both cinematic text and political catalyst. It articulates how trauma—individual, familial, social—resists symbolic containment, and how resistance emerges from the very site of rupture.

Epilogue; a personal note one year later

Muhammad Rasūluf and I meet one year later in Berlin, after the second night of his debut play at the Haus der Berliner Festspiele. He is gracious, kind, welcoming, and calm. We sit on a bench at the back of the festspielhouse, near the stage door, next to a construction site and a large truck. Although not a comfortable setting, he agrees to be interviewed and permits to be recorded. His familiar and relaxed mannerism makes one forget the awkwardness of the situation. Listening to him I realize that I am at the presence of a storyteller. It is easy to listen to him. He has a lot to tell. While the years spent in the Islamic Republic’s prison may be behind him, he is not finished with that experience. Much of the breath of his storytelling swells from that not-too-far past. It is easy to lose track of time listening to him, but I wish not to pry. Walking back to Savignyplatz, I think, he has just started telling stories about what he has lately discovered. Something he did not know he had. Something that began with daring to make an underground film. And that is “not being home”!

Cite this article

This research paper critically examines the artistic and thematic significance of Muhammad Rasūluf’s film The Seed of the Sacred Fig (Dānah-yi Anjīr-i Ma‘ābid, 2024) within the context of contemporary Iranian cinema. In his unadulterated honesty, impeccable cinematography, witty location scouting, piercing close-ups and framing, and arresting movement, I argue that Rasūluf makes the ordinary extraordinary on the screen of The Seed of the Sacred Fig. Exploration of the representation of domestic life in the film, and the risks taken by the filmmakers to present an authentic portrayal of Iranian lives, is another aspect of my analysis. Meandering through the day-to-day life of a family, Rasūluf invites his spectators into a domestic space that has not been seen the screen of an Iranian film, since the establishment of the Islamic Republic in Iran. Rasūluf’s gaze onto the life of an Investigative Judge and his family turns a deceptively ordinary domestic life into an extraordinary political power struggle between genders, mythologies, and desires with the patriarchy and tyranny. His creativity allows for a composition that entices spectator’s curiosity, excitement, thrill, sympathy, and fear all at once. Lighting and cinematography create chilling frames that bring the surveilled outside inside. By juxtaposing the protagonist’s moral dilemmas with the oppressive environment of the Iranian judicial system, the film serves as a poignant commentary on the intersection of personal and political struggles. Ultimately, Rasūluf’s work is positioned at a pivotal moment in Iranian cinema, offering a platform for unfiltered storytelling and challenging censorship norms, thus paving the way for a new chapter in the exploration of Iranian identity.