Marvā Nabīlī: Woman, Rebel, Artist, Exile

Marvā Nabīlī is one of the three pioneering women filmmakers of feature films in the history of pre-revolutionary Iranian cinema, along with the two successful commercial actors turned filmmakers, Qudratzamān Vafādūst (1926 or 1927-1919), artistic pseudonym Shahlā Riyāhī, who made Marjān (1956), and Kubrā Saʿīdī (1946 or 50-2025), artistic pseudonym Shahrzād who followed her short film Ārizū’hā-yi Buzurg-i Maryam (Maryam’s Great Dreams) with the feature fiction Maryam va Mānī (Maryam and Mani, 1979), which she also wrote and for which she took charge of the cinematography. Nabīlī shot only one film inside Iran, Khāk-i Sar Bih Muhr, also known as Muhr va Khāk and Khāk-i Muhr Shudah (The Sealed Soil, 1977) and left the country with the negatives during the turbulent years of Muhammad Rizā Shah’s regime, which led to the 1978-79 Revolution.1Muhammad Rizā Pahlavī (1919-1980) was the son of Rizā Shah, who established the nation state, emerged during the post-constitutional period (1911–25). He replaced the Qājār Dynasty, crowned himself Shah in 1925 and ruled until 1941. With the outbreak of World War II and the Allied occupation of Iran, he abdicated to be replaced by Muhammad Rizā Shah Pahlavī who withstood the nationalist movement headed by the Prime Minister Muhammad Musaddiq in 1953 and reigned until 1979, when he was toppled by the Revolution masterminded by Ayatollah Rūhallāh Khumaynī (1900-1989). He died in exile in Egypt. She has never returned. The Sealed Soil has never been publicly screened in Iran, nor has it been acknowledged in the “official” histories of Iranian cinema. Outside its country of origin, however, the film has received acclaim at prestigious film festivals as a provocative meditation on female vulnerability in patriarchal cultures that also holds a mirror to the violence and turmoil of a crucial period of transition in Iranian history.

This article focuses on three aspects of the life and work of Marvā Nabīlī, who has received considerable, though sporadic, international attention over the years depending on the political and artistic trends that shape global film industries: a) her trajectory from an aspiring young painting student in pre-revolutionary Iran to a self-exiled filmmaker in the United States; b) an analysis of her most renowned work, The Sealed Soil with the purpose to explore the film’s aesthetics and filmic style within the context of the film practices of its day and almost half a century later; and c) her niche within the context of Iranian and global cinema, leaving the last word to Nabīlī herself. The article benefits from a private interview with Marvā Nabīlī, conducted by the author at the residence of Nabīlī’s niece in London, on August 20, 2017, following the screening of The Sealed Soil at the BFI (British Film Institute).2All quotations from Nabīlī are drawn from this interview. I wish to thank Mania Akbari, Iranian filmmaker in exile, actor, and visual media artist for introducing me to Marvā Nabīlī and arranging this interview and to Marvā Nabīlī for her hospitality inviting an absolute stranger to her private family domain, and her openness, patience and generosity in sharing valuable details of her life and art.

Figure 1: Marvā Nabīlī in London in 2017 at the house of her niece (photo by Gönül Dönmez-Colin)

- From Pre-revolutionary Iran to California: A Rebel with a Cause

Marvā Nabīlī was born in Iran in 1941 to an open minded, progressive family and raised as a Bāhā’ī, “a religion that was not so discriminated against then as now,” as she recalls.3The Bahā’ī Faith is a universalist religion, originating with the Bāb’s declaration in 1844 and founded by Bahā’u’llāh in the 19th century. After the Bāb’s incarceration and subsequent execution in 1850, one of his disciples, Husayn ‘Alī Nūrī (known as Bahá’u’lláh, meaning “Glory of God” in Arabic) declared himself the Messenger of God. The religion advocates the unity of all religions and the unity of humanity. Believers are devoted to the abolition of racial, class, and religious prejudices and to the affirmation of the innate nobility of the human being. Under the Islamic Republic regime, an estimated 300,000 Bāhā’īs face systematic state-sponsored persecution in Iran. See: “Bahāʾī Faith,” Encyclopaedia Britannica, accessed November 6, 2025, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Bahai-Faith. Distinguished Iranian filmmaker Muhammad Rasūluf (b. 1972) was severely reprimanded by the authorities for his award-winning film, Lerd (A Man of Integrity, 2017), which exposes the persecution of the Bāhā’īs in present-day Iran. Her father was mostly absent, living in India and Afghanistan. He died when Nabīlī was two years old. Widowed at the age of twenty-seven, her mother decided to raise her three children alone rather than marry a suitable man for support. Initially, she opened a kindergarten; she later worked as a secretary for the railroads. She sent her son to a British school in India when he was eleven years old. The boy continued his studies in London and eventually settled in the United Kingdom. As a very independent woman, her mother became Nabīlī’s “role model,” as she underlines.

The beginning of the 1960s when young Marva was a student at the Decorative Arts Faculty of the University of Tehran was a period of rapid changes in Iran. After the 1953 coup d’état, which, with the aid of the United States and the United Kingdom, overthrew the legally elected government of Prime Minister Muhammad Musaddiq4Muhammad Mussaddiq (1882-1967) was the 30th prime minister of Iran (1951-53) best known for his social security measures, land reforms and the nationalization of the Iranian oil industry. and brought back Muhammad Rizā Shah Pahlavī from his temporary exile, the monarchy became more authoritarian. The networks of the bazaar and the clerics constituted the heart of civil society but there was no autonomous political society since the banning of all major parties after the 1953 coup.5Kevan Harris, “A Martyrs’ Welfare State and Its Contradictions: Regime Resilience and Limits through the Lens of Social Policy in Iran,” in Middle East Authoritarianisms, Governance, Contestation, and Regime Resilience in Syria and Iran, ed. Steven Heydemann and Reinoud Leenders, (Stanford: Stanford University Press. 2013), 61–80; and Cihan Tuğal, The Fall of the Turkish Model: How the Arab Uprisings Brought Down Islamic Liberalism (London and New York: Verso, 2016), 46. In 1958, the Shah established the brutal secret police, SAVAK. In 1961, he dissolved the 20th Majles, the legislative assembly, and subsequently passed the land reform law. The White Revolution, ratified in 1963 with the aim of industrializing the country while weakening the privileges of the landlords, merchants, and the clergy, was a turning point. The republican development models of Turkey and Egypt, which the Shah took as a model produced similar results as in those countries benefiting the urban regions more than the rural, and formal employees more than informal employees. The outcome was an exclusionary corporatism that left large parts of society outside the formal sectors of production and protection, paving the way for Ayatollah Khumaynī, a dissident cleric, to seize the opportunity to lead the dissatisfied masses.6Michael M. J. Fischer, Iran: From Religious Dispute to Revolution (Cambridge: Harvard University Press,1980). He masterminded a major uprising in June 1963, which was brutally crushed, and Khumaynī was subsequently exiled to Turkey and then to Iraq.

Encouraged by Suhrāb Sipihrī her professor in painting, and supported by her brother, who offered her the train ticket but no other assistance, twenty-two-year-old Marvā headed for London in 1963 to escape the present social and political uncertainties and to search for better possibilities to accommodate her artistic talents.7Suhrāb Sipihrī (1928-1980), a prominent modernist poet and painter from a family of artists and poets, traveled widely, studied art in Tokyo and Paris. His work reflects a synthesis of Eastern philosophies and Western artistic techniques. Although her original idea was a short trip to visit relatives, when she found a job as an au pair with a friendly family in the affluent Hampstead neighborhood, she stayed until 1966.

Nabīlī was always interested in cinema, although initially she studied painting. Upon her return to Tehran, Farīdūn Rāhnamā, her professor in film aesthetics, who had just returned from studying in Paris, offered her the job of script assistant on his film in preproduction, Siyāvash dar Takht-i Jamshīd (Siyavash in Persepolis, 1965), as well as the opportunity to play one of the main characters.8Farīdūn Rāhnamā (1930–1975), a filmmaker and poet, first drew attention with Takht-i Jamshīd (Persepolis, 1960). Marvā Nabīlī dedicated her first film, The Sealed Soil, to Rāhnamā. For more on Rāhnamā, see Hamid Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema. Volume 2 The Industrializing Years, 1941–1978 (Duke University Press. Durham and London: 2011), 93-5. Nabīlī recalls: “I played Sūdābah. Based on Firdawsī’s Shāh’nāmah (The Book of Kings) (980-1010), it was a very avant-garde film. In several episodes, the main character walks around Persepolis introducing other characters.” In retrospective, the film has come to be recognized as a forerunner of the formal asceticism of the post-revolutionary Iranian cinema.9Siyāvash dar Takht-i Jamshīd (Siyavash in Persepolis, 1965) is available on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=82vN0CTQBrs (Accessed, November 7, 2025) Just like Sipihrī, Rāhnamā also encouraged Nabīlī to leave the country and study cinema abroad.

A new opportunity arose when a family living on the outskirts of New York needed an au pair and were willing to pay the transatlantic fare. After two years of working for them, young Nabīlī moved to the center of New York, where she supported herself by modeling and waiting tables while studying French cinema at the New York University. During this period, she was deeply influenced by Robert Bresson and his style, which she aspired to follow.10Robert Bresson (1901–1999) was a French filmmaker whose aesthetics—the ellipses, the use of non-professional actors, the avoidance of non-diegetic music, and on-location shooting—and minimalist style have influenced filmmaking practices globally. Among his most renowned works are Pickpocket (1959), Au hasard Balthasar (Balthasar, 1966), and Argent (Money, 1983).

As a student, in New York, and later in California, Nabīlī experienced the 1960s cultural revolution, “the political awakening, the counterculture, and the psychedelia.” She described herself as a “hippie.” However, in 1975, at the age of thirty-four, she decided it was time “to be real,” to return home and capture the reality that had been omitted from the popular fare inundating Iranian screens. In the atmosphere of increased political repression, the Shah’s cultural policies became more lenient toward Indian-style song-and-dance films, one-dimensional melodramas modeled on Egyptian or Turkish trends, and Persianized versions of popular Western movies. What eventually came to be known as Fīlm-fārsī exploited the female body in films targeting the young working-class single male audiences or migrant workers separated from their families, banking on their suppressed sexual drives.11See Gönül Dönmez-Colin, Women in the Cinemas of Iran and Turkey: As Images and as Image-makers. (London and New York: Routledge, 2019), 43.

The male-dominated atmosphere of the pre-revolutionary Iranian film industry was not conducive to the participation of women. The New Wave (mawj-i naw) movement of the 1960s and 1970s helped shape the Iranian public’s perception of the Westernization process in the name of modernization and contributed to a broader cultural transformation. However, it continued to relegate women to the margins, despite ongoing social reforms and the increasing recognition of women’s rights in certain sectors. The movement itself was initiated by a woman, Furūgh Farrukhzād (1934-1967), who subverted male-defined aesthetic standards of beauty in cinema by offering a different representation of the female body and its beauty in Khānah Siyāh Ast (The House is Black, 1962), a rare documentary on disability that she scripted, directed, and edited. Nevertheless, several talented and qualified women filmmakers remained largely confined to television productions.12A number of well-known women filmmakers of today, including Pūrān Dirakhshandah (b. 1951) and Rakhshān Banī-Iʿtimād (b. 1954), began their careers in the television sector prior to the revolution. (From the unpublished interviews with Dirakhshandah and Banī-Iʿtimād in Tehran on 24 April 2017 during the 35th Fajr International Film Festival and published interview with Banī-Iʿtimād. See Gönül Dönmez-Colin, Cinemas of the Other: A Personal Journey with Film-makers from Iran and Turkey, 2nd ed. (Intellect. Bristol and Chicago: 2012), 15-25.

While waiting for an opportunity to shoot her own film, Nabīlī began collaborating with her cousin, Bārbad Tāhirī, who had been commissioned by the Iranian National Radio and Television (NIRT) to produce a twelve-episode television series titled Afsānah’hā-yi kuhan-i Īrānī (Ancient Fairy Tales, also known as Old Persian Legends, 1977–8).13Bārbad Tāhirī (1942–2010) was an Iranian filmmaker known for his multifaceted contributions to cinema as a director, co-director, producer, and cinematographer. He directed Suqūt-i 57 (The Fall of 57, 1979); co-directed the television series Samak-i ʿAyyār (1975) alongside Vārūzh Karīm’masīhī and Muhammadrizā Aslānī; co-produced Khudāhāfiz Rafīq (Goodbye Friend, 1971), directed by Amīr Nādirī, in collaboration with ʿAbbās Shabāvīz; and served as cinematographer for Ragbār (Downpour, 1972), directed by Bahrām Bayzāʾī. She worked on the series for approximately one year, directing some of the episodes alongside Malik-Jahān Khazāyī (b. 1949), another talented young woman who had served as the set and costume designer for the historical TV series Samak-i ʿAyyār (directed by Vārūzh Karīm’masīhī, Muhammadrizā Aslānī and Bārbad Tāhirī, 1975). The money Nabīlī earned was allocated to the production of her film, which would also serve as her master’s thesis.

In the village of Qalʿah Naw’askar, near Abadan in the south of Tehran where her sister worked as a schoolteacher, Nabīlī was deeply troubled by the story of a fifteen-year-old girl about to be married without her consent. As a young woman, she also resisted pressures to marry and stayed single to pursue her studies and career possibilities. “I did not marry until I was 35”, she admits. Having experienced the cultural revolution of the 1960s in the West, she “could not remain silent in the face of the oppression of women.” However, she did not have the necessary permit to shoot a film. Tāhirī suggested that they present the project as part of the television series. He offered to be her cinematographer, while his wife, Filurā Shabāvīz, who was already acting in the TV series, agreed to play the female lead. Thus began the lengthy process of writing the script, which took over two months and involved several visits to the village, including a month-long stay with Shabāvīz to observe daily life.14In 1979, Filurā Shabāvīz and her husband, Bārbad Tāhirī, relocated to the United States; according to Marvā Nabīlī, she never acted again.

Figure 2: Still from The Sealed Soil (Khāk-i Sar Bih Muhr), directed by Marvā Nabīlī, 1977.

The shooting, which took only six days, went smoothly, as Nabīlī recalls, “with the collaboration of the villagers, including those who took part in the film and without any unpleasant incidents despite the dominance of men in the industry,” which she attributes to the “broadmindedness” of her producer, Tāhirī. “It was a different kind of relationship. I was the boss,” she adds.

Once shooting was completed, Nabīlī placed the 16mm negatives in her suitcase and traveled to New York, where she edited the film and dubbed it using the voices of local professional Iranian dubbers. “It was low budget, and it had a lot of flaws,” she comments. “The word got around that I ‘smuggled’ the film. I don’t know, and I don’t mind, as I do not intend to go back to Iran, and nobody is inviting me anyway. I wonder if they know about me and my film over there, which is fine.”

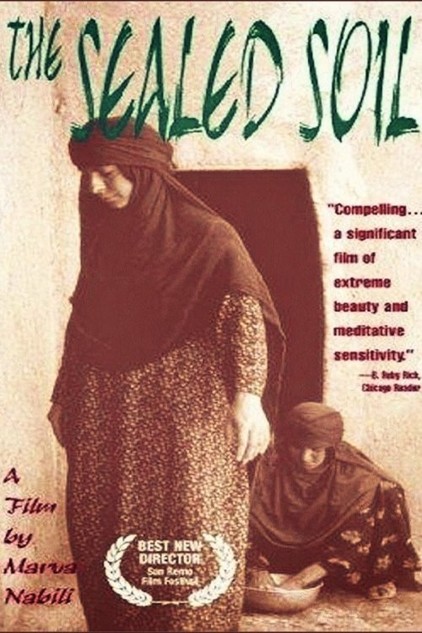

The film, which had never been publicly screened in its country of origin, began its festival journey at the Berlinale Film Forum in 1977 during the 27th edition, and received the Best Newcomer Award at the San Remo Film Festival the same year. Its U.S. premiere took place on January 25, 1978.15A New York Times article dated June 9, 1978, “Mideast Feminism: Views of Female Film Makers” by Barbara Crossette narrates an interview, conducted with three women filmmakers from the Middle East, “Layla Abou‐Saif, an Egyptian; Edna Politi, an Israeli, and Marva Nabili, an Iranian” on the occasion of the Middle East Film Festival taking place in New York with a simultaneous panel on “Women, Cinema and the Middle East” at the New York University. Crossette states: “Miss Nabili, 37, a pioneering woman in Iran in both television and film, have made what might be called feminist films.” She quotes Nabīlī saying, “Anyone working with me took me right away as a joke…There I was, a tiny woman. I couldn’t be gentle: I’ll tell you, I really had to be a bitch” adding, “What you create is something different from how you approach it. Work may change your method, but it never changes your personality.” See Barbara Crossette, “Mideast Feminism: Views of Female Film Makers,” New York Times, June 9, 1978, https://www.nytimes.com/1978/06/09/archives/mideast-feminism-views-of-female-film-makers-feminist-films-trying.html. Subsequently, it was invited to the London Film Festival and was also screened during the first edition of Festival des 3 Continents (3 Continents Festival) in Nantes, France, in 1979. After a long hiatus, it was featured in the “Women Filmmakers from Iran and Turkey” section of the Brisbane Film Festival in Australia in 2006, curated by this author. When Nabīlī arrived at the London Women’s Film Festival in 2017 for the 40th-anniversary screening, “the reel box still had the labels from Brisbane,” she commented, drawing attention to another long period of obscurity.

International attention was revived following the digital restoration from the original A/B 16mm negatives in 2024 by the UCLA Film and Television Archive. Screenings at the New York Film Festival, London Film Festival, the Valladolid International Film Festival, and others took place the same year and reviews in well-known publications followed.16“The Sealed Soil: Modesty and Its Discontents,” New York Times, May 28, 2025, accessed November 11, 2025, https://www.nytimes.com/2025/05/28/movies/the-sealed-soil-bam.html; Matt Zoller Seitz, “Reviews: The Sealed Soil,” Roger Ebert, accessed November 11, 2025, https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/the-sealed-soil-1977-4k-rerelease-film-review-2025, are two examples. Numerous additional international festival invitations have ensued, as the Zan, Zindagī, Āzādī (Woman, Life, Freedom) movement, triggered by the death of Mahsā Amīnī at the hands of Iran’s morality police in 2022 for defying the mandatory hijab regulations, has gained momentum, and female resistance against patriarchal authority, a central concern of the film, has begun to resonate globally, particularly among younger generations.17Restored by UCLA Film & Television Archive in 2024 with funding provided by Golden Globe Foundation, Century Arts Foundation, Farhang Foundation and Mark Amin, from the 16mm original A/B negatives, color reversal internegative, magnetic track, and optical track negative. Laboratory services by Illuminate Hollywood, Corpus Fluxus, Audio Mechanics, Simon Daniel Sound with the collaboration of Thomas A. Fauci, Marvā Nabīlī, and Garineh Nazarian.

Nabīlī’s second feature, Nightsongs (1984), was made in the United States. It emerged from a workshop she attended in 1982 with five other screenwriters at the Sundance Film Festival, where she also received financial support. The film centers on a young Chinese-Vietnamese woman who arrives in New York to live with the relatives of her husband while working in a clothing sweatshop in Chinatown. She finds solace in writing Chinese poetry as she misses her family. In the film, her internal soliloquies (vocalized in English) are superimposed over her image.

The central theme parallels that of The Sealed Soil, depicting the shift in society from traditionalism to modernity through the struggles of a young woman. Silent resistance of the oppressed female is again a strong trope for disempowerment and resistance to authority. As Kaplan argues, silence is “a political resistance to male domination,” a manner for women to find “ways to communicate outside of, beyond, the male sphere,” through a “politics of silence that at once exposes their oppressed situation as women within patriarchy and suggests gaps through which change may begin to take place.”18Ann E. Kaplan, Women and Film: Both Sides of the Camera (London & New York: Routledge, 1983), 9.

Nabīlī directed Nightsongs and also served as its cinematographer, an example of accented filmmaking, according to Hamid Naficy, who recalls Nina Menkes, another accented filmmaker, who viewed this practice of “multifunctionality [as] a proactive strategy” rather than merely “a form of victimization and poverty.”19Hamid Naficy, An Accented Cinema: Exilic and Diasporic Filmmaking (Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2001), 49. The film was produced for PBS’s American Playhouse series by Nabīlī’s husband, Thomas A. Fucci, screenwriter, director and producer. “By performing multiple functions, the filmmaker is able to shape a film’s vision and aesthetics and become truly its author,” Naficy claims, although “multiple involvement in all phases and aspects of films is not a universally desired ideal; it is often a stressful condition forced by exile and interstitiality.”20Hamid Naficy, An Accented Cinema: Exilic and Diasporic Filmmaking (Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2001), 49.

Nightsongs is a “nuanced and emotionally involving study of the traumatic effects of cultural displacement”, claims Christopher Gow. As the group of immigrants “are of Chinese origin rather than Iranian, the film, directed by Iranian émigré Marva Nabili, also significantly hints at the emergence of a pan-diasporic dimension to Iranian émigré cinema, although this dimension does not yet manifest itself as such with the diegetic world of the film,” as the characters form a distinct diasporic community in the Chinatown of New York City where they live and work. Their community is “fractured along generational lines,” as Gow underlines. What distinguishes the film slightly from other émigré films, according to Gow, is that despite her use of common émigré film tropes such as having the teenager Tak Men wander around the streets of New York City to show his alienation, Nabīlī does not offer colorful images of those streets. “There is no cultural allure or hidden delights on the lonely, bleak streets of Nightsongs’ New York City.” On the other hand, there is “a gritty, desolate beauty” to those images “reminiscent of Chantal Akerman’s News from Home (1977) and which when combined with the ‘authentic’, premodern, almost ethnographic quality of the traditional Chinese music playing on the soundtrack – which clashes noticeably with the film’s contemporary urban setting – serves to enhance Tak Men’s gradual withdrawal from the world around him.”21Christopher Gow, From Iran to Hollywood and Some Places in-Between: Reframing Post-revolutionary Iranian Cinema (London & New York: I.B. Tauris, 2011), 90-1.

Reception within the Chinese community, particularly among Asian-American filmmakers, was not favorable to a film featuring a Chinese narrative made by an Iranian, despite the substantial involvement of a Chinese crew and the film’s universal theme, which, according to Nabīlī, is “the alienation of a young person cut from her roots.” For Naficy, this is another example of “intraethnic controversy,” which he describes as “integral to the politics of postcolonial identity cinema”22Hamid Naficy, An Accented Cinema: Exilic and Diasporic Filmmaking (Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2001) 73. and “another aspect of the ‘politics of hyphen,’ confining filmmakers to their own ethnic boundaries and encouraging ethnic essentialism.”23Hamid Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema. Volume 4: The Globalizing Era, 1984–2010 (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2012), 438.

Nabīlī has made her home in the United States as an émigré, but, as a free spirit, she has “eluded being part of the Iranian diaspora.” She has kept a close eye on the contemporary Iranian “art cinema through the opportunities offered by film festivals, following the works of masters such as ‘Abbās Kiyārustamī and Ashgar Farhādī, always staying away from the commercial fare.”24Internationally renowned Iranian filmmaker ‘Abbās Kiyārustamī (1940–2016) won the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival for Ta‘m-i Gīlās (Taste of Cherry, 1997), among numerous other prestigious international awards. Asghar Farhādī (born 1972) is another internationally renowned Iranian filmmaker and the recipient of two Academy Awards, in 2012 and 2017, for Judā’ī-i Nādir az Sīmīn (A Seperation, 2011) and Furūshandah (The Salesman, 2016) respectively, among other distinguished awards. She spent fifteen years working as an editor in the Hollywood film industry before retiring. Although she wrote several screenplays, she never made another film.

Figure 3: Poster of The Sealed Soil (Khāk-i Sar Bih Muhr), directed by Marvā Nabīlī, 1977.

- The Sealed Soil

The Sealed Soil tells the story of a young peasant woman caught between the conventional values of her environment and her yearning for freedom during a period of transition from traditionalism to state-imposed modernization—associated with land redistribution, hygiene, literacy and education programs, and new housing developments.

Although Nabīlī focuses on the disruptive effects of the modernization initiatives imposed by the Shah’s White Revolution on the village life, at the heart of the film lies patriarchal oppression that is manifested in various forms, including male domination within the microcosm of the family, the community, and society at large, as well as top-down oppression imposed by the ruling elite. This is conveyed through the experiences of an eighteen-year-old peasant woman named Rūy-bih-khayr (Filurā Shabāvīz), who is expected to marry a suitable provider according to local customs. As she silently struggles for independence and self-identity, refusing all suitors, she is reprimanded by her uncle, the village chief, who reminds her that she is better off than the previous generation. Her mother had been married off at the age of seven, and by eighteen, she had already given birth to four children. “Today, you can’t force a girl to marry a man,” laments the chief.25The Sealed Soil, directed by Marvā Nabīlī (Iran/USA, Venera Films, 1977), 01:00:51.

Figure 4: Family consultation with the village chief. Screenshot from The Sealed Soil (Khāk-i Sar Bih Muhr), directed by Marvā Nabīlī, 1977.

For Rūy-bih-Khayr, who is secretly attempting to learn to read, even the possibility of being mistaken by the schoolteacher for the mother of one of her sister’s classmates constitutes an offense. She withdraws from her environment, avoiding the gossipy village women while doing the family laundry by the river and finding solace in daily walks through the woods. These are accompanied by a non-diegetic sound, a Kurdish folk song. When she is pressured to accept a man whose primary asset is that he “owns a TV set,” she suffers from a nervous breakdown, lashing out in frustration and kicking the perpetually peeping chicks in the yard.26The Sealed Soil, directed by Marvā Nabīlī (Iran/USA, Venera Films, 1977), 01:05:20.

Figure 5: Rūy-bih-khayr in her sanctuary. Screenshot from The Sealed Soil (Khāk-i Sar Bih Muhr), directed by Marvā Nabīlī, 1977.

Women pass burning lead over her head to expel evil spirits. She is locked in a room away from a child, as she is believed to be “possessed.” A procession of villagers of all ages, including children and the elderly, take her to the local exorcist to cleanse her soul. With her head down, she follows their footsteps—a scene not unlike early practices in Western societies, where women who did not confirm to patriarchal norms were sent to asylums.

In retrospective, this episode could also be considered as a premonition for what happened later in Iran with the Revolution, when “the people turned to the person whom they took to be a harmless old healer, Ayatollah Khomeini, and expected him to cure the country’s ailments with some tried-and-true traditional medicine.” Not unlike the Iranian nation, “Ruy Bekheir […] does not react so well to the traditional medicine” as Pardo underlines, “In her weakness and perplexity, she displays strong resistance to the system that wants to co-opt her into the patriarchal way of life. Her solution is disintegration and being cleansed by the rain.”27Eldad J. Pardo, “Iranian Cinema, 1968‑1978: Female Characters and Social Dilemmas on the Eve of the Revolution,” Middle Eastern Studies 40, no. 3 (May 2004): 47.

The village of Qalʿah Naw’askar resembles the leper colony in Farrukhzād’s The House is Black, constructing a potent trope for the socio-political atmosphere of the period through the central motif of claustrophobia induced by confined spaces. Nabīlī’s camera captures a village in which ordinary people repeat daily routines of their lives, mostly in silence. Under the heavy hand of the state, men have little control over the course of their lives, and women even less—confined to dark places, perpetually hiding their faces, their lips “sealed” except for the occasional outburst at the communal fountain, the women’s space: “We live in a strange world!”28The Sealed Soil, directed by Marvā Nabīlī (Iran/USA, Venera Films, 1977), 00:37:15.

The visual patterning of the film is designed to alternate the narrative between two oppositional cinematic spaces that are performative in shaping its context. The primitive village, with its mud huts, dirt roads, arranged marriages, exorcists, and women who live in the shadows, is juxtaposed with the new settlement, shahrak (literally, small town), characterized by its concrete dwellings, a school with a teacher in Western clothes (played in the film by the actual teacher who was Nabili’s sister), representing the Shah’s Literacy Corps, Sipāh-i Dānish (Army of Knowledge), an educational program which emerged during the White Revolution employing young urban Iranians to educate the illiterate peasants. The asphalt road with motorized vehicles renders the occasional horse and rider anachronistic.

The emancipatory reforms promoted by the Shah stop at a symbolic border, marked by a red-and-white line and a physical barrier. Neither side crosses to the other—except for the children who are eager to learn to read and write despite daily reprimands from the condescending urban teacher. The teacher scolds them for not washing their hair with shampoo every day, despite the reality that soap is rationed, and the village lacks water, as evidenced by earlier images of women washing clothes in the river or lining up to fill buckets from a single source—a direct reference to the unrealistic policies of the Shah.

“The ‘forced time’ imposed by the government aims at destroying the village and its mud-brick houses to cram the unwilling inhabitants into concrete apartment buildings—an architecture that is not conducive to the hot climate,” Nabīlī explains. Agribusiness companies are taking over the land that the villagers once cultivated. Unlike earlier times, when private landowners would share a portion of the crop with farmers to store for winter, they now offer cash to be spent at government shops. “What about our cows?” one peasant asks the chief. “You won’t need your cows,” he is told. “You’ll buy milk from the store.”29The Sealed Soil, directed by Marvā Nabīlī (Iran/USA, Venera Films, 1977), 00:28:41. Those who do not have enough cash migrate to the cities.

An act of “state violence” is enacted through the erasure of the land’s memory.30Vivian Sobchack, “11. The Change of the Real: Embodied Knowledge and Cinematic Consciousness,” in Carnal Thoughts: Embodiment and Moving Image Culture (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004), 281. The confused villagers are reluctant to accept top-down changes that threaten their customs and traditions. Under the circumstances, the brief encounter with the village chief, who has already assimilated into the new way of life and now acts as a mediator, gains affective significance. This is the same chief who had lectured Rūy-bih-khayr earlier in favor of child brides and arranged marriages. He is an apt trope for the modernization and Westernization ideologies of the Pahlavī regime, which were laden with dichotomies regarding the modern versus the traditional. As Minoo Moallem comments:

While modernist forms of femininity were disciplined by the state through national performance, modernist education, and print and media representations, it was family and community members who policed the so-called world of tradition, the world confined to the private sphere (the household, community spaces, neighborhoods, particular urban spaces). Modernization and Westernization neither challenged patriarchy in Iran nor changed it. Indeed, they merely divided patriarchy into hegemonic and subordinated semiotic regimes positioned to compete for control of women’s bodies and minds.31Minoo Moallem, Between Warrior Brother and Veiled Sister Islamic Fundamentalism and the Politics of Patriarchy in Iran (Berkeley: University of California Press. 2005), 3.

Rūy-bih-khayr, who sends her younger sister to fetch water from the construction site to avoid crossing the demarcation line, is not entirely bound to the old ways of life, but the new one fails to serve her needs. “In her search for an identity, she is caught in the middle,” Nabīlī emphasizes. As the quotation from Albert Camus during the opening sequences foreshadows, “But before man accepts the sacred world and in order that he should be able to accept it—or before he escapes from it and in order that he should be able to escape from it—there is always a period of soul-searching and rebellion.”32Albert Camus, The Rebel: An Essay on Man in Revolt, revised and complete translation of L’Homme Révolté by Antony Bower (New York: Vintage Books, 1956), 21.

Societal violence against the female body reaches its climax when Rūy-bih-khayr stops at her usual sanctuary in the forest while gathering wood. In a cathartic moment underscoring women’s agoraphobia, claustrophobia, and spatial confinement, the body takes over the narrative. She sheds her clothes under the pouring rain and offers her naked body in ecstasy to nature as to a lover. The camera, which has previously favored dark corners and uncanny spaces, now focuses on the rays of the sun falling on her bare back. Although the moment is open to interpretation as erotically charged, Nabīlī does not agree: This is a symbolic act of the release of tension from oppression. Rain cleanses her. Then she has a nervous breakdown because she can’t take it anymore. She is told to put [on] her best dress and get ready, “they are coming to take a look at you” as if she is a piece of meat. In her defiance, she goes out and hits the chicks.33The Sealed Soil, directed by Marvā Nabīlī (Iran/USA, Venera Films, 1977), 01:05:20.

Upon reflection, almost five decades and several civil movements later, Rūy-bih-khayr’s shedding of her garments can be viewed as a precursor of the acts of courageous women today who risk their lives to liberate themselves from the hijab and other symbols of patriarchal oppression. The fact that the next sequence in the film shows happy children returning home from school in full sunlight can be interpreted as a ray of hope for the future.

The Sealed Soil, is a compelling example of “slow cinema,” decades before the term was allegedly coined by Michel Ciment (1938-2023), the French film critic, and the editor of the film journal Positif, who employed it in his “State of Cinema” speech in 2003 at the 46th San Francisco International Film Festival.34“Michel Ciment: The State of Cinema,” San Francisco International Film Festival, 2003, accessed November 4, 2025, https://web.archive.org/web/20040325130014/http://www.sfiff.org/fest03/special/state.html. Its commitment to realism and authenticity in its depiction of local settings and traditions, the stillness of diegetic action, the use of a stationary camera, and its transgression of the boundaries between fiction, documentary, and experimental cinema align it with the works of Lav Diaz of the Philippines35Lav Diaz (b. 1958) is the recipient of numerous prestigious international prizes, including the Golden Lion for Ang Babaeng Humayo (The Woman Who Left, 2016) at the 73rd Venice Film Festival. The film was based on Leo Tolstoy’s novel, God Sees the Truth but Waits. Norte, Hangganan ng Kasaysayan (Norte, The End of History, 2013) adapted from Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s Crime and Punishment, a film running 250 minutes with very few camera movements was screened at the Cannes Film Festival’s Un Certain Regards section to critical acclaim. and the early works of Nuri Bilge Ceylan of Turkey.36Nuri Bilge Ceylan (b. 1959), recipient of multiple prestigious awards at the Cannes Film Festival, among which, the Golden Palm in 2014 for Kış Uykusu (Winter Sleep, 2014), has been considered as one of the followers of “slow cinema” aesthetics starting with his first films, among which Kasaba (Small Town, 1997), Mayıs Sıkıntısı (Clouds of May, 1999), Uzak (Distant, 2002) and İklimler (Climates, 2006) could be considered as prominent examples. For more on Ceylan, see: Gönül Dönmez-Colin, ed. Re:Focus; The Films of Nuri Bilge Ceylan (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2023). Its cinematic stillness also resonates with the work of Apichatpong Weerasethakul of Thailand.37Apichatpong Weerasethakul (b. 1970) is the recipient of the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival for Lung Bunmi Raluek Chat (Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives, 2010), among several other prestigious awards. All of them are considered contemporary masters of “slow cinema.”38Recent research has begun to examine The Sealed Soil as an example of Slow Cinema. See: S. Amiri, “Marvā Nabīlī’s The Sealed Soil as Slow Cinema,” Cinema Iranica, Encyclopaedia Iranica Foundation, https://cinema.iranicaonline.org/article/marva-nabilis-the-sealed-soil-as-slow-cinema/. At the same time, The Sealed Soil’s slowness echoes the works of several avant-garde filmmakers of its period, many of whom turned to slow pacing, most likely “as [a] reaction against the increasing speed of mainstream movies, whether it was intended or unintended.”39Peter Wollen, Paris Hollywood: Writings on Film (London and New York: Verso, 2002), 270. Nabīlī also asserts that shooting The Sealed Soil in real time was “a small revolution for Iranian cinema of the period that was occupied with imitating the fast-shooting cowboy films of Hollywood.”40For more on “slow cinema,” see: Tiago de Luca and Nuno Barradas Jorge, eds., Slow Cinema (Traditions in World Cinema) (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2015), particularly chapters 6 and 7 on Weerasethakul (pp. 99–111) and Diaz (pp. 112–122).

The slow tempo of the narrative and the aesthetic features of the film also serve as a form of resistance against the accelerated tempo of modernity that infringes upon the lives of the villagers. The premeditated long takes that stretch time and space disrupt the conventional figure-ground relationship to express temporality, or “time-image,” as defined by Gilles Deleuze.41Gilles Deleuze, Cinéma 2: L’image-temps (Paris: Les Éditions de Minuit, 1985), translated by Hugh Tomlinson and Robert Galeta as Time-Image (London & New York: The Athlone Press, 1989). Nabīlī emphasizes stillness and the everyday. The spiral lingers on images of people entering or leaving the village through the frame of a wooden arch, and on the detailed, cyclical repetitions of daily chores—such as women picking stones from rice or turning dough, or the repeated “peep, peep” of chicks—challenging the notion of a hypothetically “homogeneous empty time” of historical progress.42Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism, revised ed. (London and New York: Verso, 2006), 24, 26.

Nabīlī is cautious about identifying herself as a political filmmaker, despite the film’s evident political undertones. At its core, the narrative centers on the oppression of women by retrograde customs. This theme is rendered through her cinéma vérité style, which captures the transition in the lives of ordinary people from traditional practices to state-imposed, unrealistic modernity, often accompanied by moments of comic relief that arise from the irony of the situations depicted. The refrain of the “peep, peep, peep” of the chicks, heard at regular intervals and a source of mounting frustration for the protagonist, becomes a powerful leitmotif that reminds the audience of the monotony of her restricted existence, while also serving as comic relief in a somber narrative of entrapment.

The subjectivities of modernity, time, and history are further challenged in several instances, including through the medium of the exorcist’s body, which contests the assumption that such traditions are embedded in an atemporal modernity.43For further discussion on this subject, see Laura Kendall, Shamans, Nostalgies, and the IMF: South Korean Popular Religion in Motion (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2009). At the same time, a spiritual man endowed with the power to purify the wayward woman—thereby disempowering her to ensure obedience to patriarchal authority—functions as a precursor to the religious leaders in contemporary Iran who seek to suppress women’s resilience in their struggle to break the yoke of patriarchy and express their individuality and identity.

- Nabīlī’s Legacy

Focusing on a female character and highlighting her tribulations under the yoke of the patriarchal traditions, The Sealed Soil is unconventional for the pre-revolutionary Iranian cinema, including the New Wave, which was dominated by male filmmakers whose privileged perspectives seldom placed women at the center of the narrative, except to expose their bodies for the benefit of male viewers. With a few notable exceptions—such as Dāvūd Mullāpūr’s Shawhar-i Āhū Khānum (Mrs. Ahu’s Husband, 1968), Ibrāhīm Gulistān’s Khisht va Āyinah (Brick and Mirror, 1965), and the works of Bahrām Bayzāʾī such as Charīkah-yi Tārā (Ballad of Tara, 1978)— the formal elements of these films, including the mise-en-scène, composition, costume, gesture, facial expression, focus, and lighting, often reinforced entrenched ideologies regarding women. Significant New Wave films, such as Qaysar (1969) by Masʿūd Kīmiyā’ī, endorsed patriarchal values marginalizing women and presenting distorted representations.44Gönül Dönmez-Colin, Women in the Cinemas of Iran and Turkey: As Images and as Image-makers (London and New York: Routledge 2019), 45-6, 62, 147. The testimony of twenty-five female icons interviewed for the documentary Razor’s Edge: The Legacy of Iranian Actresses (2016) further confirms that pre-revolutionary Iranian cinema was, in essence, a patriarchal cinema that mirrored the country’s patriarchal culture, positioning women as inferior subjects devoid of agency. The films predominantly emphasized male experiences and perspectives.45Bahman Maghsoudlou, Razor’s Edge: The Legacy of Iranian Actresses (USA, International Film and Video Center, New York, 2016), documentary film.

Hamid Naficy describes The Sealed Soil as “consciously experimental, influenced by the austere aesthetics of the Japanese director Kenji Mizogouchi, by the tableau-like Persian miniature paintings, and, most important, by Bertolt Brecht’s ‘alienation effect.’”46Hamid Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema. Volume 2: The Industrializing Years, 1941-1978 (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2011), 376. Distinguished films journals such as Sight and Sound and Cahier du Cinéma have compared Nabīlī’s stylistic approach to that of Chantal Akerman’s in Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975), particularly in terms of merging the quotidian with the cinematic and employing a gaze that is both intimate and distanced. The aesthetics of both films are unquestionably revolutionary.

For Saljoughi, The Sealed Soil as “a meditation on the politics and aesthetics of refusal.” She argues that the film articulates a politics of refusal that emerges on three registers: The first refusal is thematic; Rūy-bih-khayr refuses to marry or disclose her reasons for doing so. A parallel refusal of narrative is the villagers’ refusal to forgo their traditional ways and accept the state-imposed changes to their lives. The second refusal is embedded in the film form-fixed camera, long shots, avoidance of close-ups- as a resistance to mainstream cinematic conventions. By distancing her camera, Nabīlī initiates the modesty act, the so-called “distanced look” generally attributed to postrevolutionary Iranian cinema by the scholars.47See: Negar Mottahedeh, Displaced Allegories: Post-Revolutionary Iranian Cinema (Durham: Duke University Press, 2008). Her camera “refuses to satisfy the desires of the spectatorial gaze.” The third refusal is the camera’s distance from Rūy-bih-khayr’s face and body, which separates the film from the mainstream Iranian cinema, particularly the Fīlm-fārsī, which thrived on exposing women, particularly their bodies.48Sara Saljoughi, “A Cinema of Refusal: The Sealed Soil and the Political Aesthetics of the Iranian New Wave,” Feminist Media Histories 3, no. 1 (2017): 81-82.

During the Q&A session following the screening of the Sealed Soil in 2017 at the BFI, a member of the audience pointed to certain parallels she identified between The Sealed Soil and Gāv (The Cow, 1970) by the distinguished Iranian filmmaker Dāryūsh Mihrjūyī (1939-2023), particularly in the depiction of the underdeveloped rural life. Nabīlī’s response was that she did not see The Cow until several years later in the United States admiring the film as she admires other films of Mihrjūyī. Comparison could also be drawn with the early works of Suhrāb Shahīd Sālis (1944-1998), a master of minimalist slow cinema who reacted against cinematic conventions prevalent during the Iranian New Wave with his first two films, Yak Ittifāq-i Sādah (A Simple Event, 1973) and Tabiʿat-i Bī’jān (Still Life, 1974), before relocating to the West to pursue a more independent career. Elements such as the stillness and loneliness of daily life observed in real time, the impassive Bresson-like performances, the rhythmic, distant sound of drums propelling the narrative in Still Life, and the refrain of the “peep, peep, peep” of the chicks in The Sealed Soil, connect these contemporaries, even though it is unlikely that the two filmmakers were aware of each other’s work at the time.

One may question how unbiased the gaze of a young, urban, Western-educated middle-class filmmaker can be—a follower of Brecht and Bresson—returning from the free-love, anti-establishment socio-political milieu of the 1970s New York and California to immerse herself in the life of a traditional village confronted by modernizing measures imposed from above by a Shah soon to be deposed. Nabīlī was an outsider and a nonparticipating observer who, had a script to follow and instructed the villagers “what to do, rehearse briefly and then shoot.” She notes that they were “cooperative, including those who acted in the film,” although they were not aware of the content of the script. A further concern is how one avoids the temptation to self-Orientalization—a particular risk for filmmakers in similar circumstances, accentuating the issues of their developing or under-developed countries in films that will eventually reach audiences in developed Western countries.

Nabīlī acknowledges that her engagement with the emerging feminist movements in the West influenced her decision to explore the subject of women’s oppression in so-called “primitive” cultures⸺ “women practically sold for a TV set.” The empathy she felt for the constrained choices available to villagers trapped in cyclical, limited lives was genuine, and she adopted an ethnographic approach to convey her narrative.

She admits that she had been away from Iran for extended periods since 1963 and had not viewed Iranian films prior to shooting The Sealed Soil. Reflecting on her intentions as both a filmmaker and an observer of cultural realities, Nabīlī offers a lucid articulation of her aesthetic decisions and theoretical influences, explaining the visual and narrative strategies she employed in The Sealed Soil:

In terms of its style, The Sealed Soil may not fit the expectations of the audience as an Iranian film. For example, framing the village activities through open doors is Bresson. I also avoided close-ups and zooms to remind the audience that this was a staged play, to force them to make their own decisions. I combined Brecht’s approach with my own culture of Persian poetry and miniature painting adapting how the second incorporates the background, the landscape, and the dwellings. I minimized the dialogue and the camera movements, preserving a tempo of action, inaction, action, which is my preferred style. I thought life in the village was so still, it did not need any camera movements, or dialogues. There was nothing to be said. Only the chickens were driving her nuts. In terms of its subject, the film is extremely Iranian. I wanted to show that life. The repetition, everyday-ness. What you see in the film is the real life. The title The Sealed Soil represents the film. It is a sealed deal. The title matches the situation.49Marvā Nabīlī, interview by the author, 2017.