Representations of the Child and Childhood in Iranian Artistic Cinema for Children and Young Adults (1960–1979)

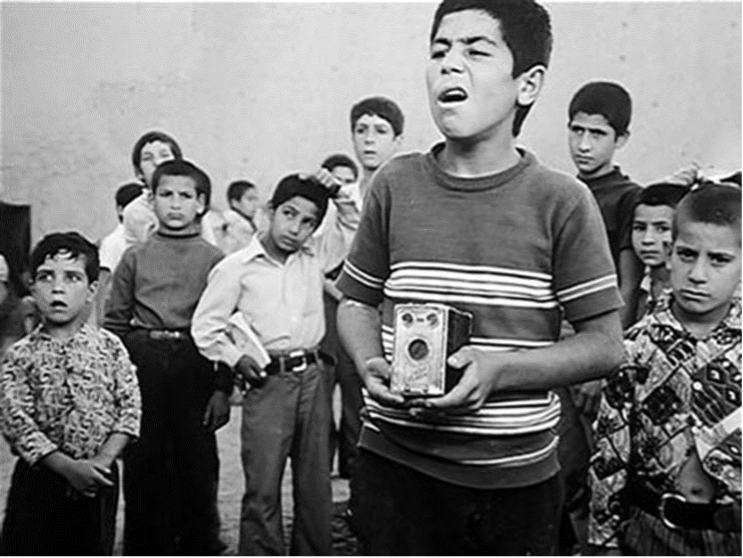

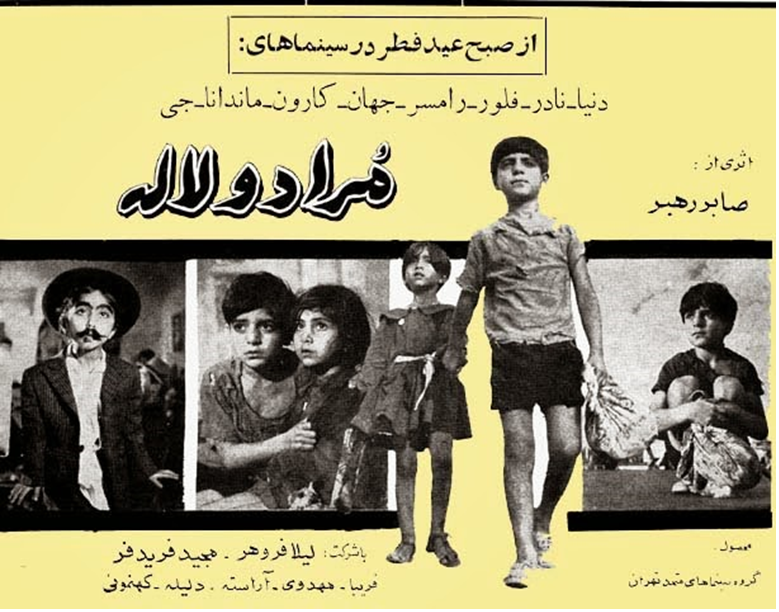

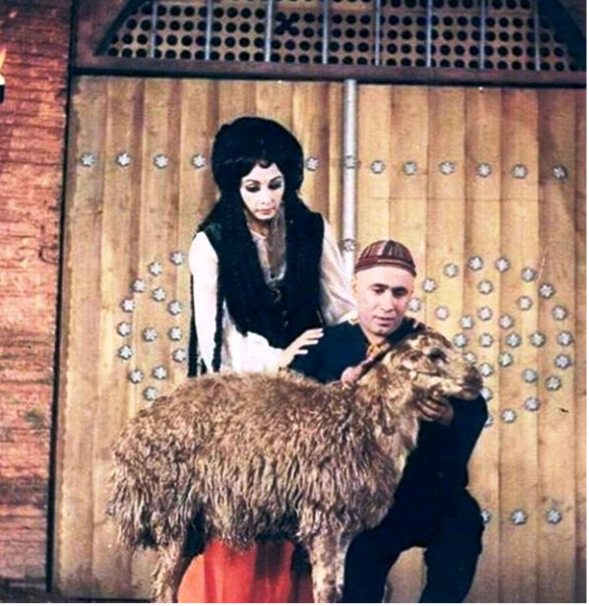

Figure 1: Still from the film Murād va Lālah (Morad and Laleh), directed by Sābir Rahbar, 1965.

Introduction

This article examines the aesthetic and social representations of the child and childhood in the period leading up to the 1979 Revolution. The research specifically focuses on feature-length narrative films aimed at children and adolescents up to the age of eighteen, which were screened in cinemas.

The relationship between childhood and cinema is interactive, rather than one-sided. Cinema does not merely reflect childhood; it also has the power to reshape and redefine societal notions of childhood, often challenging prevailing expectations. In other words, children’s cinema, or films for a general adult audience featuring children, presents an ‘ideal image of the child,’ one that both parents and children may adopt as a model to emulate. This dynamic gives rise to two distinct types of childhood: the actual and the ideal.

Throughout its 120-year history, Iranian cinema has frequently explored themes of children and childhood. However, due to the scope and limitations of this study, the focus is specifically on the emergence of artistic children’s cinema, which, from the author’s perspective, began in 1960. This research is both historical and analytical in nature, with sources gathered through library-based methods, including written documents and the analysis of over seventy extant films.

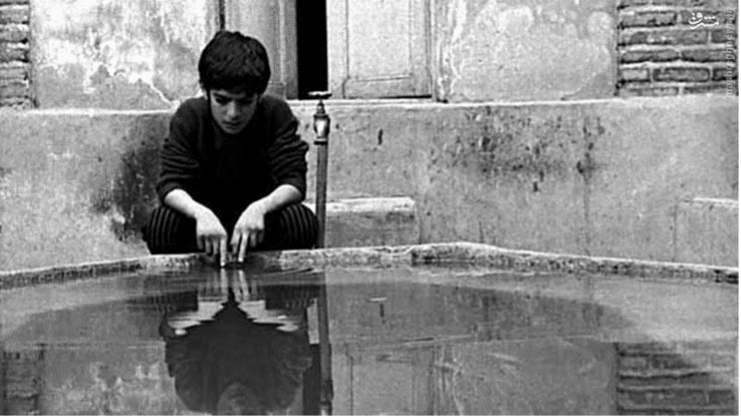

Figure 2: Still from the film Musāfir (The Traveler), directed by ʿAbbās Kiyārustamī, 1974.

General Considerations

1. Research Type

The research is historical and analytical in nature, with sources gathered through library-based methods, including written documents and the analysis of feature-length narrative films screened in Iran for children and adolescents up to the age of eighteen.

2. Research Questions

This article aims to address three key questions:

a. What is the analytical framework for Iranian children’s and adolescents’ cinema?

b. How are the produced works related to changes in social conditions?

c. In what ways have the concepts of the child and childhood been represented across different periods?

3. Significance of the Topic and its Application

In his essay “The Age of the World Picture,” Martin Heidegger highlights one of the defining characteristics of the modern era, distinguishing it from earlier periods like the Middle Ages or Antiquity: the transformation of the world into an image. He writes:

[…] world picture, when understood essentially, does not mean a picture of the world but the world conceived and grasped as picture […] the fact that the world becomes picture at all is what distinguishes the essence of the modern age [der Neuzeit].1Martin Heidegger, “The Age of the World Picture,” in Science and the Quest for Reality, ed. A. I. Tauber (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1997), 81.

Children’s initial connection to the world is primarily mediated through vision. For young children, who have not yet developed reading skills, images serve both as a support and a vital supplement, facilitating the development of literacy. Their inherent fascination with images plays a crucial role in sparking interest in picture books and, more broadly, in cultivating a reading habit. Clearly, the earlier visual communication and literacy are fostered, the more enduring their impact will be. Children are naturally more open and responsive to their surroundings than adults, who often become desensitized through repetition.

The influence of narrative cinema exceeds that of educational media because it engages audiences through art and its various elements: beauty, creativity, innovation, imagination, emotion, and indirect expression. Cinema’s ability to evoke mental pleasure and connect with the unconscious ⸺free from the constraints of practical gain or loss⸺ highlights the importance of visual literacy and imagery.

Similarly, Heinz Werner has explored children’s capacity for ‘physiognomic perception,’ contrasting it with ‘geometric-technical perception.’ He notes that when children say the sun is happy, the tree is sad, or a cup lying on its side is tired, they are not making secondary inferences; rather, they are directly perceiving these qualities in the objects themselves.2Brady Wagoner, “The Organismic Theory of Development: Romantic Roots of a Vital Concept,” Theory & Psychology 34, no. 1 (2024): 136-37.

Ian Verstegen, in his article “The Politics of Physiognomic Perception,” argues that “Werner clearly had what could be characterized as romantic beliefs that children and ‘primitive’ peoples perceived the world in a more expressive way. He called this “physiognomic perception,” and contrasted it with the perception of ‘geometrical-technical qualities.’”3Ian Verstegen, “The Politics of Physiognomic Perception,” Gestalt Theory 44, no. 1-2 (August 2022): 187.

It is clear that a significant part of human perception of film and artistic imagery is sensory and intuitive. In this regard, children and adolescents possess abilities in this area that may have diminished or been entirely lost in adults.

4. Background and Sources

To identify and assess existing sources on the history of Iranian children’s cinema and the representation of childhood, the Cinema Iranica bibliography was consulted. The search yielded a variety of materials, including articles, interviews, reports, conference papers, and press notes, though none directly or comprehensively address the specific focus of this study. Additionally, the search also resulted in the discovery of two Persian-language books, 20 non-Persian books, 14 university theses, two tertiary sources, and six non-Persian websites, four of which are anonymous. With the exception of two books and one article, none of these sources directly engage with the core subject of this research.

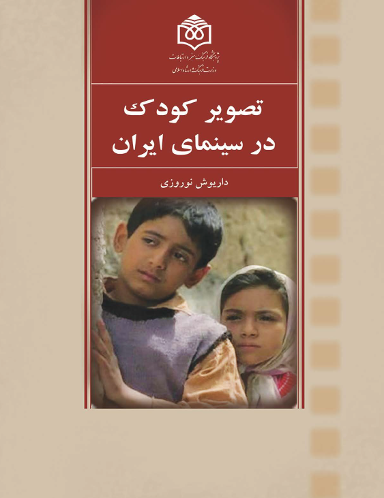

The first book is Tasvīr-i Kūdak dar Sīnimā-yi Īrān (The Image of the Child in Iranian Cinema) by Dāryūsh Nawrūzī(2013). The significance of this work lies in its research-oriented structure, balanced perspective, comprehensiveness, and the importance of the sources it references. However, like any book, it has its limitations. For instance, it occasionally repeats discussions without systematic organization, does not fully address the topic of children’s literature, concludes abruptly without a proper closing section, and lacks a thorough analysis of the decline of children’s cinema.

Figure 3: Book Cover of Tasvīr-i Kūdak dar Sīnimā-yi Īrān (The Image of the Child in Iranian Cinema), by Dāryūsh Nawrūzī, 2013.

The second book is Farhang-i Fīlm’hā-yi Kūdakān va Nawjavānān az Āghāz tā Sāl-i 1367 (Encyclopedia of Children’s and Adolescents’ Films from the Beginning to 1988), compiled by ‘Abbās Jahāngīriyān (1988). The author provides a concise analytical introduction to the history of children’s cinema, followed by a presentation of the films, including production details and brief plot summaries, organized alphabetically rather than chronologically. Given that the work was published in 1988—during a pivotal period in the development of children’s cinema—it inevitably omits certain key developments and information.

Figure 4: Book cover of Farhang-i Fīlm’hā-yi Kūdakān va Nawjavānān az Āghāz tā Sāl-i 1367 (Encyclopedia of Children’s and Adolescents’ Films from the Beginning to 1988), by ‘Abbās Jahāngīriyān, 1988.

The only article that provides a review of the history of children’s and young adult cinema in Iran is ʻAlī Dādras’s “Tārikhchah-yi Sīnimā-yi Kūdak va Nawjavān dar Īrān” (The History of Children’s and Young Adult Cinema in Iran).

In addition, there are books on Iranian cinema that contain limited and often insufficient sections on children’s cinema; these sources have been cited in the present study where applicable. However, this article explores a subject that has not been examined in such depth before.4For information regarding film awards, the comprehensive database of Iranian cinema was consulted: www.sourehcinema.com.

5. Scholarly Approaches of the Article

The central theme of this article revolves around the concepts of the ‘child’ and ‘childhood.’ A key point raised is the lack of consensus regarding the definition of the child. There is no single, unified understanding of what constitutes the child or childhood; rather, these concepts are interpreted in various ways. Childhood studies have yet to be established as a distinct academic discipline like psychology or economics. Instead, they remain part of the broader humanities, intersecting with a wide range of fields. As a result, childhood studies are inherently interdisciplinary. While they maintain a degree of autonomy, they are closely connected to other domains such as art, literature, linguistics, psychology, education, sociology, religion, and philosophy. This article places particular emphasis on the psychological and sociological perspectives within the diverse approaches to studying childhood.

5.1. The Psychological Approach

Our psychological approach draws on selected theories of Jean Piaget, Laura E. Berk, and Gareth B. Matthews. Jean Piaget demonstrated that the cognitive systems of children function independently from those of adults. He maintained close engagement with children and approached them with deep respect. Central to Piaget’s theory is the notion that children’s ways of thinking and acting are logical and meaningful within the framework of their own developing logic, rather than being measured against adult standards. His insights, along with those of his followers, significantly advanced the principles of child-centered education.

Building on and at times moving beyond Piaget’s foundational work, psychologists such as Laura E. Berk have offered more nuanced accounts of cognitive development. Berk, in particular, has advanced the view that children possess greater cognitive capacities than Piaget originally proposed.5Laura E. Berk, Development Through the Lifespan, 7th ed. (SAGE Publications, 2022), 491.

According to more recent theories advanced by scholars such as Gareth B. Matthews, a specialist in the philosophy of childhood, children engage with complex concepts—such as philosophy, ethics, death, literature, and art—to a far greater extent than traditionally acknowledged in developmental psychology. Indeed, Matthews contends that certain artistic creations by children, such as their drawings, should be regarded as genuine works of art, deserving a place alongside those of adult artists in museums, rather than being treated merely as data for psychological analysis or reflections of a child’s inner world.6Gareth B. Matthews, The Philosophy of Childhood (Harvard University Press, 1996), 39–48, 61–86, 95–117.

To outline the characteristics of adolescence, this article draws on Erik Erikson’s theory of psychosocial development. Erikson identifies adolescence as a particularly critical and formative stage of life, during which individuals confront the fundamental question of identity. Adolescents strive to define their place in the world with respect to occupation, social roles, sexuality, and interpersonal relationships. This identity-seeking process is inherently challenging and often accompanied by significant anxiety. In attempting to forge a coherent identity, adolescents frequently experiment with a range of roles, perspectives, and belief systems. Erikson refers to this period of exploration as a “moratorium.”7James E. Côté, “Identity Formation and Self-Development in Adolescence,” in Handbook of Adolescent Psychology, vol. 1, ed. Richard M. Lerner and Laurence Steinberg (New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, 2004), 269.

Those who successfully navigate this complex developmental stage—achieving a well-integrated and stable sense of self—entering adulthood with competence, confidence, and self-assurance. In contrast, failure to establish a coherent identity may result in a prolonged identity crisis.8Fātimāh Kiyānpūr, Jamāl Haqīqī, Husayn Shikarkan, and Bahman Najārriyān, “Rābatah-yi haft marhalah-yi avval-i nazariyyah-yi rushd-i ravānī-ijtimā‘ī-i Erikson bā marhalah-yi hashtum-i ān (kamāl dar barābar-i nā’umīdī) dar sālmandān-i ustān-i Khūzistān [The Relationship of the First Seven Stages of Erikson’s Theory of Psychosocial Development to its Eighth Stage—Integrity vs. Despair—among the Elderly in Khuzestan Province],” ‘Ulūm-i Tarbiyatī va Ravān-shināsī 3, no. 9, issue 1-2 (2002): 18, 21. According to Erikson, the central developmental task of adolescence is to answer the existential questions: “Who am I?” and “What am I doing?” He emphasized that occupation and ideology play decisive roles in shaping adolescent identity. As such, Erikson viewed identity formation as encompassing group affiliation, gender, culture, religion, and ideological orientation.9James E. Côté, “Identity Formation and Self-Development in Adolescence,” in Handbook of Adolescent Psychology, vol. 1, ed. Richard M. Lerner and Laurence Steinberg (New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, 2004), 269.

Figure 5: Still from the film Musāfir (The Traveler), directed by ʿAbbās Kiyārustamī, 1974.

Adolescent psychological disorders are closely related to the confusion or uncertainty around an individual’s sense of purpose or identity. Questions about one’s place in the world or the meaning of life become central concerns during adolescence, and it is during this stage that individuals begin to seek general answers to these questions. The formation of the ‘self’ during these years is both complex and fragile. Adolescents often feel lonely, and this feeling, along with other psychological symptoms, comes from focusing inward. Feelings of being misunderstood and occasional self-centeredness in adolescence stem from this process of development.

The stage prior to assuming employment or adult responsibilities is characterized by a persistent uncertainty regarding one’s identity. An adolescent vacillates between roles of a child and an adult. During this time, they often identify with various figures of admiration, such as athletes, friends, or teachers. Unlike in childhood play-acting, these identifications are no longer merely symbolic; the adolescent’s experiences and actions in these roles are profound and impactful. Many of these roles are experienced in extreme forms, as the adolescent attempts to explore and solidify their evolving sense of self.10Husayn Lutfābādī, Ravān-shināsī-i rushd, nawjavānī, javānī, buzurg’sālī [Developmental psychology, adolescence, youth, adulthood] (Tehran: Samt, 2005), 134.

5.2. Sociological Approach

Let’s briefly review some of the definitions proposed for the concept of a child: One definition suggests that a child is a member of society who has not yet acquired the social skills required to fulfill societal roles, and as a result, is not yet able to play an active or effective role within the social organization.11Allison James, Chris Jenks, and Alan Prout, Theorizing childhood (Teachers College Press, 1998), 7. This definition of the child has served as the basis for many studies of childhood, and it implies that children are expected to learn and internalize social skills. Article 1 of the Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989) defines a child as any individual under the age of 18.

Karin Lesnik-Oberstein, in her book Children in Culture, offers an alternative definition of childhood. She views ‘childhood’ as a constructed identity that varies across cultures, historical periods, and political ideologies.12Karin Lesnik-Oberstein, Children in Culture: Approaches to Childhood (London: Macmillan Press, 1998), 2. In classical sociology, the child was viewed as an underdeveloped being—dependent, immature, and incapable—regarded as merely a brief stage in human life. Today, however, the perception of the child has changed. The child is now understood as a member of society with distinctive characteristics, an active agent, and a subject capable of making choices.13Allison James, Chris Jenks, and Alan Prout, Theorizing childhood (Teachers College Press, 1998), 23; For further discussion, see, Mehdi Hejvani, Arkān-i Adabiyāt-i Kūdak [The Elements of Children’s Literature] (Tehran: Fātimī, 2023), chaps. 2-3.

6. Limitations of the Article

6.1. The Presence of Mediators

One essential aspect of children’s cinema is the unavoidable presence of intermediaries—namely, adults—who produce the films intended for young audiences. Adults may censor a movie, take children to see films of their own choice, or prevent them from watching certain works. Thus, children’s films invariably reach their audiences through various mediators, including screenwriters, directors, actors, producers, licensing authorities, parents, teachers, and school administrators. At times, we assume or anticipate that children have fully comprehended the message of a film, while, in reality, such judgments are made in their absence. Although some festivals employ children as jurors to select outstanding works, this method may not be entirely effective, as it is constrained by two factors: first, the number of children involved is typically small; and second, it is still adults who select children with specific characteristics to serve as judges.

Figure 6: Still from the film Murād va Lālah (Morad and Laleh), directed by Sābir Rahbar, 1965.

6.2. Scope Limitations

The concept of the child and childhood has been a recurring theme throughout the history of Iranian cinema, a topic that merits a thorough study. Due to scope limitations, however, this article focuses exclusively on the period between 1961 and 1979, which, in the author’s view, marks the emergence of a serious and intellectual children’s cinema. This cinema, emerging from the ‘formal recognition of childhood,’ developed in contrast to the commercial and melodramatic children’s films of the time.

- Scope of the Study

The works analyzed in this article can be categorized as follows:

- Feature films, and, in exceptional cases, medium-length and short films (but not television series);

- Fiction films, though semi-documentary works are included in rare instances;

- Films made explicitly for child or adolescent audiences;

- Works produced in live-action, puppet, or animation formats;

- Films screened in cinemas.

Accordingly, purely documentary (non-fiction) works about children—which are more relevant to inquiries about childhood—may reflect aspects of the child and childhood, but do not fall within the scope of this article.

In 1973, Hādī Payām introduced the distinction between films for children and films about children in an article titled “Children’s Cinema and the Question of the Film for the Child and about the Child.”14Hādī Payām, “Sīnimā-yi Kūdak va Mas’alah-yi Fīlm barāyi Kūdak va Darbārah-yi Kūdak [Children’s Cinema and the Question of the Film for the Child and About the Child],” Farhang va Zindagī 13-14 (1973–1974): 32-36. Later scholars expanded on these categories and identified additional types. In general, the following classification can be outlined:

—Films for children: Works explicitly produced by filmmakers with children as their intended audience.

—Films about children: Works created with the intention of deepening adults’ understanding of the world from a child’s perspective, rather than being intended for children themselves. Nevertheless, children may enjoy these films, as they see their own image reflected in them.

—Films under the pretext of the child: Works in which the child assumes a symbolic or allegorical role, rather than representing an actual or conventional childhood. The filmmakers’ intent may be to provide an indirect or aesthetic expression, or to veil political or protest-oriented discourse.

—Films featuring the presence of a child: Works in which the child plays no significant role, appearing only to enhance the story’s setting and contribute to its realism.

Figure 7: Still from the film Sāz’dahanī (The Harmonica), directed by Amīr Nādirī, 1973.

The author proposes a fifth category—multi-audience film: Works that do not target a specific age group, as their characters are mythological, legendary, or archetypal, with no real-world counterparts. Although the characters may appear physically adult, the mythical and adventure-driven structure of these films appeals equally to children and adolescents. Similarly, certain adaptations of classic novels—such as Les Misérables or Gulliver’s Travels— though not originally intended for young audiences, they often resonate with children due to the simplicity of their story structure, accessibility, or adventure-oriented themes.

From a different standpoint, it is important to note that the selection criteria for films in this article are based on a combination of four elements: the scholarly approaches adopted in the article, the reception of the films among children and the general public, their recognition at festivals featuring award-winning works, and the author’s own assessment.

The Representation of the Child and Childhood in Cinema

Children’s cinema in Iran, from 1961 to 1979, can be broadly divided into two distinct periods:

1. The First Period (1961–1971): The Birth of Artistic Children’s Cinema in Contrast to Commercial Cinema

1.1. The State of Iranian Society

—Economic conditions, including the sharp increase in oil revenues, the rise of welfare and consumerism, the development of assembly industries (including the cinema industry), and the growing demand for labor.

—Social conditions, such as migration to major cities, population growth—particularly the increase in the child population—and the expansion of the middle class.

—Cultural conditions, such as the spread and dominance of Western culture, particularly that of the United States; the introduction of television in Iran (1958); and the circulation of various foreign films and television series, which shaped part of childhood within the middle class; the expansion of public and private education and the press; the founding of the Children’s Book Council (1962) as Iran’s representative to IBBY, which promoted reading and selected outstanding works for children and adolescents; the establishment of the Center for the Production of Reading Materials for New Literates (Markaz-i tahiyyah-yi mavādd-i khāndanī barāyi nawsavādān) in 1964,15This center has now been renamed the Office of Educational Assistance. which launched the Paykmagazine series for different age groups; the founding of the Institute for the Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults (Kānūn) in 1965, which became the largest state institution dedicated to the production of cultural, artistic, and literary works; and the inauguration of the International Festival of Films for Children and Young Adults by Kānūn, whose influence gradually manifested from the end of the 1960s up until the Revolution.

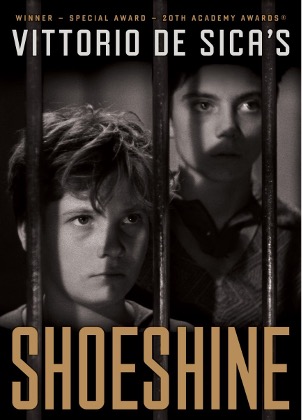

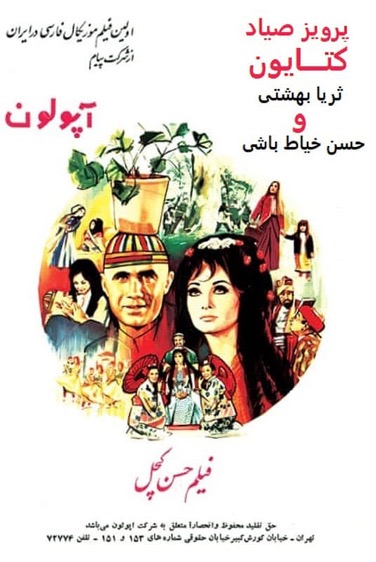

1.2. The Dominance of Commercial Cinema

The production of commercial and melodramatic films, which began in the 1950s, continued into the 1960s. The quantitative dominance of popular works over artistic productions is a typical pattern across time and place. Examples of commercial and melodramatic films from this period include the following: Murād va Lālah (Morad and Laleh, 1965), Yak Qadam tā Bihisht (One Step Then Heaven, 1966), ʿIshq-i Kawlī (Gypsy Love, 1969), Hasan Kachal (1970), Āftāb Mahtāb (1970), Zilzilah-yi Mahīb (Terrible Earthquake, 1970), Zībā-yi Jībʹbur (The Beautiful Pickpocket, 1970), Māh-Pīshunī (1971), Murgh-i Tukhm-talā (The Golden Egg-Laying Hen, 1972), Shahr-i Qissah (The Tale Town, 1973), and Rāndah Shudah (The Outcast, 1975).

Just as the development of modern Persian fiction began with the translation movement and was later followed by the creation of original works, the trajectory of Iranian cinema started with the importation and dubbing of foreign films, eventually leading to the production of indigenous works modeled after them. For instance, the story of the film Murād and Lālah, written and directed by Sābir Rahbar in 1965, was based on Vittorio De Sica’s Shoeshine (1946).

Figure 8: Film poster for Shoeshine, directed by Vittorio De Sica, 1946.

Murād va Lālah (Morad and Laleh, 1965)

Writer and Director: Sābir Rahbar

A brother and sister lose their parents in an accident and are separated. A wealthy family adopts the girl, while the boy befriends an old peddler. The old man encounters the girl and later takes the boy to see her as she prepares to leave on a journey with her adoptive parents. The old man and the boy rush to the airport, and at the last moment, the siblings are reunited. From that point on, they live together under the care of the wealthy family.

This film focuses more on children than earlier films did. In some cases, the child seems to understand more than the adults—witty, eloquent, charming, quick with responses, and seemingly all-knowing, like a wise figure. This perspective appears to be influenced by modern education; as schooling expanded, children often became more literate than their parents, which led to greater respect for them. The renowned singer Gūgūsh, for instance, had already embodied such a role in the film Bīm va Umīd (Fear and Hope, 1959), while another popular singer, Laylā Furūhar, played similar roles in Charkh u Falak (The Ferris Wheel, 1967) and Sultān-i Qalb’hā (The King of Hearts, 1968). These films suggest that the more a child acts like an adult, the better they are perceived; otherwise, they are seen as incomplete adults, becoming fully human only when they grow up.

Figure 9: Film poster for Murād va Lālah (Morad and Laleh), directed by Sābir Rahbar, 1965.

1.3. A Cinema Hall Dedicated to Children

In 1966, a movie theater named Cinémonde was established in Tehran. Located at the intersection of Takht-i Jamshīd Street (now Tāliqānī) and Pahlavī Avenue (now Valī-ʿAsr), it was dedicated specifically to screening films for children and adolescents. The theater was designed with a child-friendly atmosphere and smaller seats. These initiatives reflect a growing recognition of the importance of children and childhood in society.

2. The Second Period (1971–1979): The Emergence of Artistic and Intellectual Cinema

The social, economic, and political circumstances in Iran during this decade gave rise to intellectual and religious protest movements.

2.1. The Conflict Between Artistic and Commercial Cinema

Figure 10: Logo of the Institute for the Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults (Kānūn-i Parvarish-i Fikrī-i Kūdakān va Nawjavānān)

As mentioned earlier, following the establishment of Kānūn in 1966, the Kānūn Film Festival for Children was also founded in the same year. From 1966 to 1970, only foreign films were screened at the festival. In 1969, the Kānūn Film Center was established under the supervision of Fīrūz Shīrvānlū and ʿAbbās Kiyārustamī.

Masʿūd Mihrābī argues that the Pahlavī regime, through this initiative, aimed to create a kind of ‘showcase’ and ‘festival commodity.’ He also suggests that the government sought to distract dissatisfied intellectuals with non-political artistic projects. Regardless of the initial intent, during Kānūn’s years of cinematic activity, more than sixty films were produced, some of which are now considered among the most outstanding legacies of Iranian cinema.16Masʿūd Mihrābī, Tārikh-i Sīnimā-yi Īrān [The History of Iranian Cinema] (Tehran, 1989), 352. Evidence supports Mihrābī’s analysis

In fact, Kānūn, while in pursuit of the Pahlavī regime’s vision of Iran as the ‘Gateway to the Great Civilization,’ faced a shortage of filmmakers, writers, illustrators, and musicians specializing in works for children and adolescents. As a result, they invited artists who were unwilling to produce commercial works—and who had no prior experience in creating films for children—to work in this field. Perhaps, at that time, there was no other alternative. Therefore, artists such as ʿAbbās Kiyārustamī, Amīr Nādirī, and Bahrām Bayzā’ī engaged with children’s cinema, producing films despite their lack of prior experience in the field, primarily through experimentation. Some of their works, while rich in artistic value, also served as a reaction against the commercial, market-oriented art of the period. However, due to their experimental nature, these works sometimes diverged from the lived experiences of children and even adolescents. Moreover, their approach was occasionally instrumental: children were used as a pretext to express adult concerns, abstract ideas, frustrations, protests, or political disillusionments within works ostensibly made for young audiences. In fact, some of these productions might be better understood as films, stories, or poems ‘pretending to be for children.’

Nūraldīn Zarrīnkilk—filmmaker, illustrator at Kānūn during this period, recognized as the father of Iranian animation, and president of ASIFA International (the International Animated Film Association) from 2004 to 2006—outlined several key points, summarized as follows:

—Since filmmakers at the Kānūn Film Center were not burdened by financial concerns, they were able to indulge in creating intellectual and avant-garde subjects as a counter to Fīlmfārsī (the popular, melodramatic, commercial cinema). As a result, their films were so complex and abstract that both young and old audiences had trouble grasping them. In fact, precisely because they were unconcerned with box-office returns, they paid little attention to audience reception.

—In some cases, filmmakers addressed adults under the guise of creating films for children.

—The government aimed to produce ‘festival films’ and build a cultural showcase.17Masʿūd Mihrābī, Tārikh-i Sīnimā-yi Īrān [The History of Iranian Cinema] (Tehran, 1989), 356.

Figure 11: Postage stamp commemorating the 10th Children and Youth Film Festival organized by Kānūn.

Nevertheless, after four consecutive years in which the Kānūn Film Festival for Children and Young Adults screened only foreign productions, the establishment of the Kānūn Film Center in 1969 brought about a remarkable transformation in film production in Iran. Between 1969 and 1978, a total of 115 films were produced in three categories: fiction, animation, and educational. Among the short films produced by Kānūn, one can mention the following examples:

‘Amū Sībīlū (Uncle Mustache, 1969)

Writer and Director: Bahrām Bayzā’ī

Children play in a vacant lot next to the house of a lonely, reclusive old man, disturbing his peace. One day, the children’s ball breaks one of his windows. Fearful, the children stop visiting the lot, and a hush falls over the area. The old man suddenly becomes aware of his solitude, feels it deeply, and eventually approaches the children to reconcile with them. The story of this film is reminiscent of The Selfish Giant (1888) by Oscar Wilde, in which the giant frightens the children away, causing spring to refuse to come to his garden. In the end, he repents and befriends the children.18Oscar Wilde, “The Selfish Giant,” in The Happy Prince and Other Tales (London: David Nutt, 1888), 23–34. The central conflict and crisis in both works are fundamentally adult in nature. However, the twelve-minute film Bread and Alley presents something altogether different.

|

|

Figure 12 (Left): Character of Uncle Mustache from the film ‘Amū Sībīlū (Uncle Mustache), directed by Bahrām Bayzā’ī, 1969.

Figure 13 (Right): Book cover of The Selfish Giant by Oscar Wilde (first published in 1888).

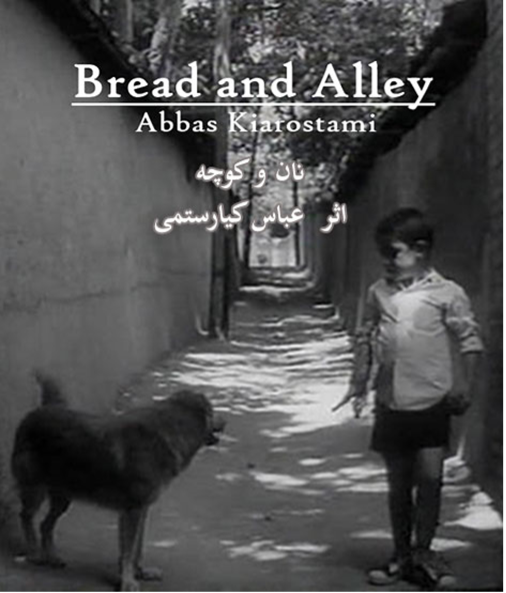

Nān va Kūchah (Bread and Alley, 1969)

Writer and Director: ʿAbbās Kiyārustamī

A young boy, having bought bread, returns home only to find a stray dog blocking the doorway. The dog barks, and the frightened child dares not move forward. In the deserted alley, no adult comes to his aid. At last, despairing of help, the boy tosses a piece of bread toward the dog. The animal calms down and follows him. Once the boy enters his home, the dog resumes its place outside the door. Another child then enters the alley, this time carrying a bowl of yogurt, and recoils at the dog’s barking. Now, it is his turn to resolve the dilemma. The subject of the film is entirely child-centered. Moreover, through its deliberately long takes and slow rhythm, the film conveys a sense of stark realism. Bread and Alley exerted considerable influence on many later works, even those produced after the 1979 Revolution. Kiyārustamī himself admitted that the film was experimental, confessing that he was unsure whether he had made a good film.19Jamāl Umīd, Tārikh-i Sīnimā-yi Īrān [The History of Iranian Cinema], vols. 1–2 (Tehran: 1995), 1028.

With the exception of four feature films, nearly all of the films produced by Kānūn were short films and, as such, were never screened in theaters. The four notable feature-length films are The Harmonica, The Traveler, Summer Vacation, and The Singer, which will be discussed below.

Figure 14: Film poster for Nān va Kūchah (Bread and Alley), directed by ʿAbbās Kiyārustamī, 1969.

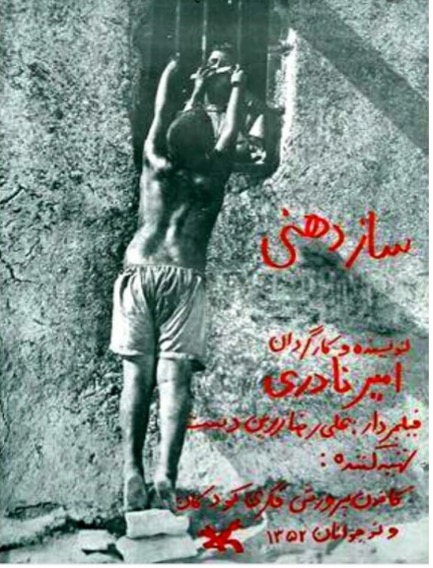

Sāz’dahanī (The Harmonica, 1973)

Writer and Director: Amīr Nādirī

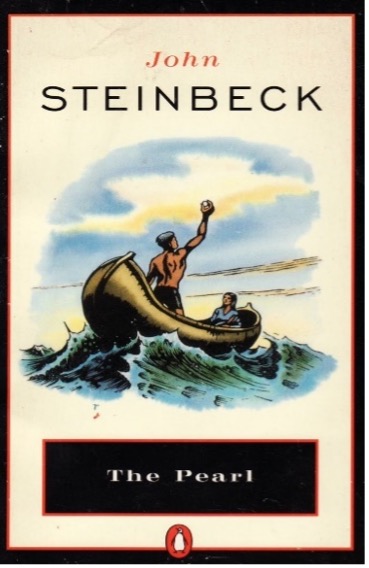

A teenage boy owns a harmonica that is coveted by the poor children in the neighborhood. For a small fee, they are allowed to play it briefly. Among them, a boy named Amīru is especially enchanted. He carries the harmonica’s owner on his shoulders so frequently that his skin becomes blistered. Amīru’s mother grows increasingly upset, and eventually, the children rise up against the harmonica’s owner. In the final scene, Amīru throws the harmonica into the sea. While The Harmonica follows a realist narrative structure, it also holds allegorical significance. On one level, it teaches children to preserve their dignity and avoid becoming anyone’s pawn. On another, it serves as a political allegory of cultural imperialism, conveying a distinctly adult-oriented message. The film thus appeals to dual audiences. The Harmonica also shares similarities with John Steinbeck’s novella The Pearl (1947).

|

|

Figure 15 (Left): Film poster for Sāz’dahanī (The Harmonica), directed by Amīr Nādirī, 1973.

Figure 16 (Right): Book cover of The Pearl by John Steinbeck (first published in 1947).

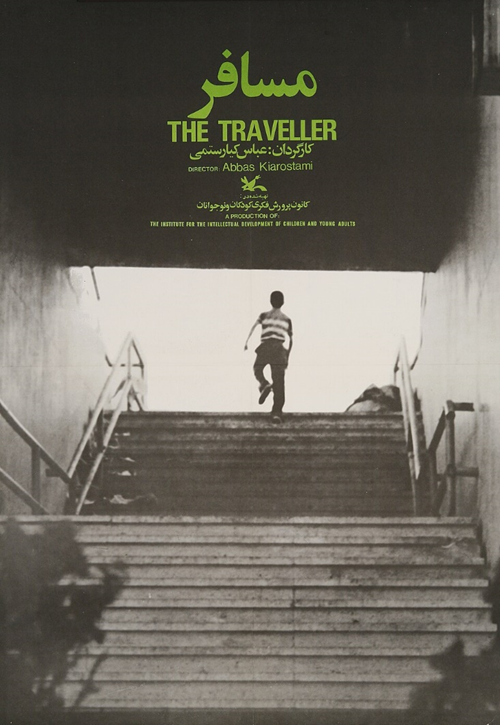

Musāfir (The Traveler)

Writer and Director: ʿAbbās Kiyārustamī (based on a story by Hasan Rafīʿī)

Winner of the Special Jury Prize and the National Iranian Television Prize at the 9th Tehran Film Festival for Children’s and Young Adults (1974).20See Comprehensive Iranian Cinema Database: www.sourehcinema.com. The film tells the story of a twelve-year-old boy obsessed with football, who resorts to trickery and petty theft to raise the money needed to travel to Tehran, the capital, in order to watch an important match. Just before the game, he buys an overpriced ticket on the black market and enters the stadium. While waiting for the match to begin, he lies down outside among a group of people resting and falls into a deep sleep from exhaustion. When he finally wakes up, the match is long over, and he finds himself in an empty stadium, surrounded by heaps of litter.

The Traveler introduces adult disillusionment into an adolescent world. However, its somber ending should not be viewed as a flaw. First, adolescence is distinct from childhood; it is a time when individuals must begin confronting life’s disappointments. Second, the boy funds his journey through theft and deceit, so, from a moral standpoint, the ending serves as a form of punishment and retribution. However, the film has a credibility issue: it seems implausible that a football-obsessed boy—who went to such lengths, even committing transgressions, to attend the match—would fall asleep amid the excitement and miss the very event he sacrificed so much to see.

Figure 17: Film poster for Musāfir (The Traveler), directed by ʿAbbās Kiyārustamī, 1974.

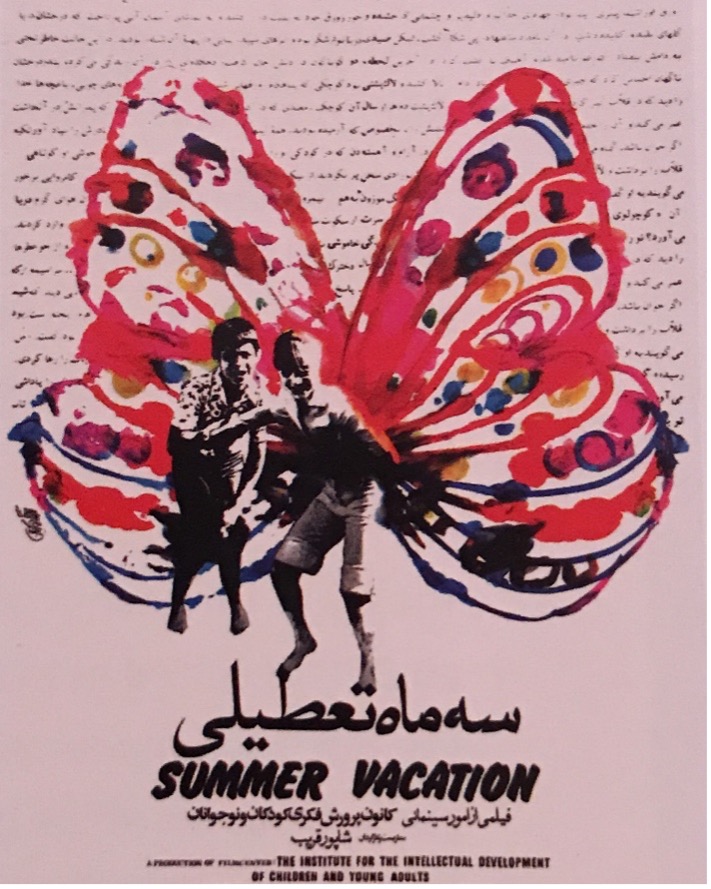

Sih Māh Taʿtīlī (Summer Vacation, 1977)

Writer and Director: Shāpūr Gharīb

As summer arrives, a group of schoolchildren at a summer retreat begins their long holiday, filled with play and amusement. Gradually, however, everything becomes monotonous, and the children, seeking to relieve their idleness, each take up some form of work. Among them, one boy makes friends with a girl who’s come to the countryside with her family for the summer. When the holiday ends, so does their short-lived friendship.

Figure 18: Film poster for Sih Māh Taʿtīlī (Summer Vacation), directed by Shāpūr Gharīb, 1977.

Āvāzah’khān (The Singer, 1979)

Director: Kayūmars Pūrahmad

Winner of the Best Professional Live Film Award at the Tehran International Film Festival for Children and Youth (1979) and the Honorary Diploma for Best Direction from the Faculty of Dramatic Arts.21See Comprehensive Iranian Cinema Database: www.sourehcinema.com. The story of the film revolves around a boy who aspires to become a singer, but his father opposes the idea, emphasizing only his son’s academic success. Eventually, despite his declining grades, the boy’s persistence and passion reveal his true talent. In the end, the father agrees to let him pursue music, on the condition that he improves his school performance.

The advantages of this film, along with the other three mentioned, can be summarized in four key points:

—Attention to the child, positioning them at the center of the film’s narrative;

—Focus on the issues and challenges faced by children;

—Involving the child in finding solutions to their own problems;

—An ethical perspective;

—Professional construction and execution of the films by accomplished filmmakers.

2.2. Nihilism

Another noteworthy film is titled A Simple Event:

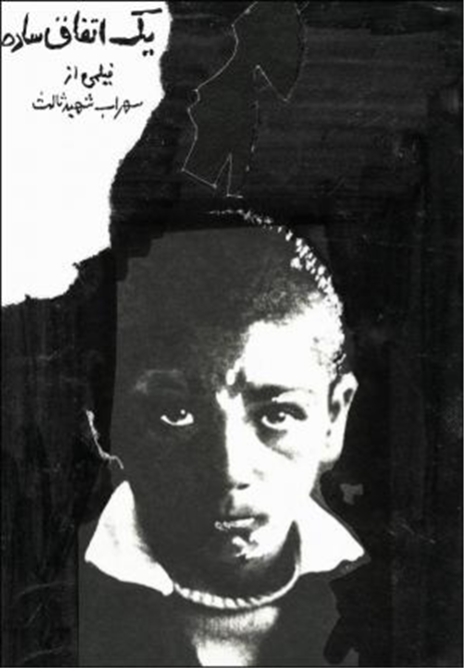

Yak Ittifāq-i Sādah (A Simple Event, 1973)

Writer and Director: Suhrāb Shahīd Sālis

Winner of the International Critics’ Prize at the 2nd Tehran International Film Festival, the Interfilm Award, and the Catholic Jury Prize at the Berlin Film Festival.22See Comprehensive Iranian Cinema Database: www.sourehcinema.com. The story follows Muhammad, a schoolboy from Bandar Turkaman, who lives with a father involved in illegal fishing and a sick mother who dies during the course of the film. The film portrays the ordinariness and monotony of daily life, with the filmmaker intentionally avoiding traditional storytelling techniques to give the work a documentary-like feel.

Figure 19: Film poster for Yak Ittifāq-i Sādah (A Simple Event), directed by Suhrāb Shahīd Sālis, 1973.

Suhrāb Shahīd Sālis is a significant and influential director in Iranian cinema. He never claimed that A Simple Eventwas made specifically for children. Moreover, the film was not produced at the Institute for the Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults, which primarily focused on producing films aimed at children and adolescents as the target audience. However, due to Muhammad’s central presence in the film, one could interpret his role either as a purely physical presence—aimed at enhancing the realistic aspects of the scenes—or as a symbolic device. Shahīd Sālis’s realism goes beyond conventional realism. The film takes on the qualities of a documentary for several reasons, including: a focus on the lives of the underprivileged and their harsh conditions; the use of long takes and slow pacing; static long shots; silences and prolonged pauses; an emphasis on ‘dead time’ and empty moments; a narrative rhythm that mirrors or approximates calendrical time; the repetition of motifs and monotonous daily routines; the use of cold and lifeless colors; the absence of music in favor of sound effects to create a distinct atmosphere and convey inner turmoil; the employment of non-professional actors; a focus on anti-narrative structures; and a deliberate distancing from melodramatic climaxes intended to manipulate the spectator’s emotions.

In this film, Muhammad is depicted as constantly running—at times appearing to have no clear direction or purpose, as if he’s not actually moving forward—reflecting the director’s bleak and despairing worldview. The author believes that Shahīd Sālis is the Sādiq Hidāyat of Iranian cinema.

2.3. Protest Films

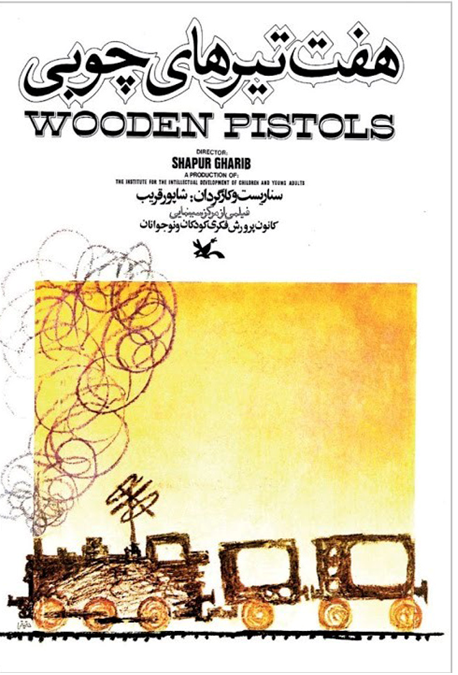

As previously mentioned, during this decade, waves of dissent gradually gained force in the cultural milieu. Among these artistic expressions was a film produced in protest against the introduction of television to Iran, titled Wooden Pistols.

Haft’tīr’hā-yi Chūbī (Wooden Pistols, 1975)

Director: Shāpūr Gharīb

Winner of the Golden Award for Best Short Film at the First Cairo International Film Festival (1976); recipient of two first prizes from the Youth Jury and the Children’s Jury at the First Lausanne International Festival of Films for Children and Adolescents (1977); and winner of the Golden Plaque for Best Actor at the 10th Tehran International Film Festival for Children and Adolescents (1975).23See Comprehensive Iranian Cinema Database: www.sourehcinema.com.

The story takes place near a railway station, where children, living in a traditional setting, are depicted as close friends who go to school, play games together, and spend their evenings listening to their grandmothers’ tales. However, everything changes when television arrives. Families begin gathering in one house to watch action-packed Western movies. These films inspire the children to imitate the heroes they see on screen, occasionally staging mock hostage situations. Not surprisingly, such behaviors often lead to adverse outcomes.

Figure 20: Film poster for Haft’tīr’hā-yi Chūbī (Wooden Pistols), directed by Shāpūr Gharīb, 1975.

2.4. Adaptations from Folk Culture

Another stream in Iranian cinema—though apparently not as prominent as its commercial or intellectual counterparts—is filmmaking based on adaptations of folk tales, such as Mullā Nasr al-Dīn (1954). Initially, these films were not made for children; however, given the growing emphasis on children in the 1960s and 1970s, certain childlike elements were incorporated, though not to the extent that the works could be considered true children’s films.

Figure 21: Film poster for Hasan Kachal (Hasan the Bald), directed by ʿAli Hātamī, 1970.

In 1970, ʿAli Hātamī directed a film titled Hasan Kachal (Hasan the Bald), based on a traditional folk and children’s tale. Film critic and sociologist Dāryūsh Nawrūzī argues that Hātamī blended a folkloric story with adult themes, noting that the long songs, which would not appeal to children, and the modifications to the story (such as Hasan Kachal falling in love) caused the film to lose its childlike charm. As a result, it is not regarded as a children’s film. Nawrūzī asserts that the era of such tales has ended, and today’s urban children no longer connect with them. Nevertheless, the film was a commercial success, yet Nawrūzī does not address why it succeeded despite these shortcomings.24Dāryūsh Nawrūzī, Tasvīr-i Kūdak dar Sīnimā-yi Īrān [The Image of the Child in Iranian Cinema] (Tehran: Pazhūhishgāh-i Farhang, Hunar, va Irtibātāt, 2013), 169–170.

The author of this article argues that, on the contrary, folk tales are appealing to both adults and children. If screenplays based on folk tales are well-written and well-directed, they can resonate with audiences, as demonstrated, to a significant extent, by Hātamī’s film. The success of Hasan Kachal can undoubtedly be attributed to the public’s enduring affection for folk stories. It seems unlikely that urbanization, whether affecting children or adults, would distance them from films rooted in folk culture. On the contrary, the monotony of urban life might lead the audience to find comfort and escape in the freshness and imagination of folk or fairy tales.

Figure 22: Still from the film Hasan Kachal (Hasan the Bald), directed by ʿAli Hātamī, 1970.

2.5. The 1979 Revolution

From a socio-political perspective, the artistic atmosphere of the 1970s was strongly shaped by the rise in political protests from Islamic, communist, and nationalist groups against the Pahlavī regime. These protests later culminated in the Islamic Revolution of 1979. Although the early years after the revolution focused on the number of productions and slogan-driven works, this open environment eventually led to the creation of original works in many areas, including children’s cinema—a subject that deserves further research.

Conclusion

This article has aimed to evaluate the representation of the child and childhood in the emergence of serious children’s cinema, considering the relevant social conditions and contexts. It has sought to address three key questions: (a) What is the analytical framework of Iranian children’s and youth cinema? (b) How are the works produced related to social changes? (c) How has the concept of the child and childhood evolved across different periods?

First, the importance of the ‘image’ was explored along the following axes: the role of images in modern life as indicators of the modern world; the impact of visual communication on child development as a primary connection to the outside world; children’s affinity for imagery; their greater susceptibility to images compared to adults; the capacity for intuitive perception in children; and the greater influence of cinema as an artistic medium compared to educational media. Subsequently, the psychological and sociological approaches outlined in the article were discussed. Based on these approaches, a relative definition of the concept of child was provided. The following section has outlined the limitations of the research, including the role of intermediaries in children’s arts, such as children’s cinema, and the influence of personal biases. Furthermore, the scope of the research and the types of films are also discussed.

Children’s cinema from approximately 1961 to 1979 can be divided into two main periods. The first period (1961-1971) saw the emergence of cultural transformations in opposition to popular and commercial cinema. During this time, a confluence of economic, social, and cultural factors shaped society, including:

—A massive influx of oil revenue, which fueled widespread consumerism and increased public affluence.

—The expansion of assembly-based industries (including film production) and their growing demand for labor.

—Accelerated rural-to-urban migration, driven by the pursuit of higher wages and better educational opportunities.

—A significant increase in the child population.

—The launch of television in Iran in 1958 (later, Iranian National Television was inaugurated in 1967) and its extensive broadcasting of numerous foreign films and series, primarily American.

—Developments within the national education system.

—A growing press sector.

—The continued popularity of and affinity for Western lifestyle.

— The founding of the Children’s Book Council (1962), which served as the Iranian national section of IBBY.

—The founding of the Center for the Production of Reading Materials for New Literates in 1964, now known as the Office of Educational Assistance.

—The establishment of the Institute for the Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults (1965).

One of the most significant cinematic initiatives by Kānūn was the establishment of the International Film Festival for Children and Young Adults, whose influence gradually became evident by the end of the 1960s and into the following decade. From 1966 to 1970, only foreign films were screened at the festival. In 1969, the Kānūn Film Center was founded. The Pahlavī regime’s objectives behind these initiatives were to officially recognize and emphasize the importance of children and childhood, to create showcase-oriented products for festivals, and to redirect dissatisfied intellectuals toward artistic and apolitical work. Meanwhile, the production of commercial and melodramatic films, which had originated in the 1950s, persisted throughout the 1960s and 1970s.

Just as the development of fictional literature in Iran began with a wave of translations and was later accompanied by the creation of original works, the Iranian cinema industry was inaugurated through the importation and dubbing of foreign films, followed by the production of domestic films. The child of the 1960s held a more prominent role in narratives—both qualitatively and quantitatively—than the child of the 1950s. However, representations of children and childhood in the 1960s were predominantly conveyed through melodramatic works. The changes and transformations that began in the early 1960s gradually became more visible in the latter part of the decade and continued throughout the 1970s.

In the second period (1971–1979), the movement that Kānūn had initiated in the 1960s—through the establishment of the International Film Festival for Children and Young Adults and the Kānūn Film Center—fully came to fruition in the 1970s. Over several years of activity, Kānūn produced more than sixty films, some of which are considered enduring landmarks of Iranian cinema. The organization invited intellectual, often dissident artists—many of whom were unwilling to engage in commercial filmmaking and had no prior experience creating content for children—to contribute to this emerging field. It appears that, at the time, there was no viable alternative. As a result, artists such as ʿAbbās Kiyārustamī, Amīr Nādirī, and Bahrām Bayzā’ī ventured into the realm of children’s cinema, using it as a space for creative experimentation.

The works of these artists were, first and foremost, an extreme reaction against the commercial and market-driven art of the era. Secondly, because their work was experimental and not influenced by the need to make money or achieve financial success, they sometimes created films that did not closely reflect or relate to the everyday lives, experiences, or concerns of children or even adults. Thirdly, in some cases, their portrayal of children served as a pretext to introduce their own abstract, protest-driven, bitter, and political adult ideas and frustrations into works intended for children and young adults.

It seems that the unique perspective of a director like Suhrāb Shahīd Sālis—who did not work mainly in children’s cinema—or works like The Little Prince (1943) by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry—which is not really a children’s book and has mystical ideas that don’t quite fit with children’s experiences—influenced the way Iranian intellectual artists thought during that time. As a result, during the 1970s, two dominant yet conflicting and parallel currents emerged in Iranian cinema: commercial and popular cinema, and artistic, protest-driven, intellectual cinema. Ultimately, the 1960s can be regarded as the birth era of serious artistic children’s cinema—a cinema that recognized children and childhood, created various works, and continued to evolve in the subsequent years.

Cite this article

This article examines the representation of children and childhood in Iran’s artistic and intellectual cinema for children and adolescents during the formative period from 1960 to 1979. Throughout these two decades, cinema not only portrayed childhood but also played a pivotal role in shaping its cultural and societal perceptions. The article’s theoretical framework for defining ‘the child’ and ‘childhood’ is grounded in psychological theories of Jean Piaget, Laura Berk, Gareth Matthews, and Erik Erikson. In the sociological domain, it draws on the perspectives of Karin Lesnik-Oberstein, Allison James, Christopher Jenks, and Alan Prout. Consequently, the article examines, on the one hand, the aesthetic dimensions of the films, and on the other hand, how they are influenced by the social conditions of each period.

Before this period, childhood was not formally recognized in cinema; children were viewed as incomplete adults and were largely absent from Iranian films. In the years that followed, children typically appeared in marginal roles, with their innocence often employed to evoke emotional responses from adults or to convey messages about the importance of family preservation. From around 1961, childhood began to receive more recognition, driven by economic and cultural developments—including the establishment of institutions such as the Institute for the Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults (Kānūn-i Parvarish-i Fikrī-i Kūdakān va Nawjavānān), the organization of film festivals, the expansion of public education, the founding of national television, and the growth of the press. However, representations of childhood were still primarily found in foreign films and domestic melodramas, rather than in Iranian artistic cinema. From 1971 to 1981, a unique artistic and intellectual cinema for children emerged, distinguishing itself from both commercial films about children and the melodramas of the era. While intellectual cinema occasionally used the child as a metaphor for adult disillusionment and political dissent, this shift paved the way for the emergence of important works in children’s cinema in post-Revolutionary Iran.

Key Words: Childhood, Children, Adolescents, Young Adults, Image, Iranian cinema, the 1979 Revolution.