The Philosophical Poetry of Makhmalbaf: On Time of Love (1991) and Sex and Philosophy (2005)

Introduction

Many critics believe that there is a poetic dimension to Makhmalbāf’s cinema, especially in the third period of his works, known with films such as Time of Love, The Nights of Zāyandah-Rūd, and Nūn-u-Guldūn (Bread and Vase, more commonly known in English as A Moment of Innocence, 1996).1Muhsin Makhmalbāf, Gung-i khvāb dīdah [The Dumb Man’s Dream: Collected Articles, Interviews and Critiques from 1981 to 1991] (Nay Publication, 1996). This poeticism is manifested in both the content and the form of Makhmalbāf’s films. One can argue that, in the domain of content, characteristics such as the intertextual relations between his films with mythological and psychological texts, the tendency toward symbolism, the movement along the boundary of reality and unreality, and the significance of philosophical conflicts are the characteristics that reinforce the poetic dimension of Makhmalbāf’s films. In terms of form, characteristics such as the deliberate and symbolic use of colors, the significance of objects, resistance against continuity editing, and the least possible use of dialogue make his films imaginative and innovative.

Figure 1 (Left): Poster of the film Time of Love (1991), Muhsin Makhmalbāf.

Figure 2 (Right): Poster of the film Sex and Philosophy (2005), Muhsin Makhmalbāf.

In the present article, we have tried to uncover the poetic aspects of Makhmalbāf’s films with a look at his two romantic films, Time of Love and Sex and Philosophy. To present a general picture of poeticism in Makhmalbāf’s films, we first discuss the themes, visual and symbolic characteristics, and dramatic aspects of Time of Love. Then in Sex and Philosophy, we analyze the themes, the intertextual relationship between the elements of the film with mythological texts, and the character symbolism. In both films, love is a means for posing more essential and ontological questions. Time of Love covers subjects such as judgement, customary and civil law, possessiveness in romantic relationships, and violence. In Sex and Philosophy, love is an excuse for the modern human’s Sisyphean search for meaning. In both films, Makhmalbāf is only trying to pose questions to his audiences and refrains from giving definite answers. In these films, love is a means for Makhmalbāf to present his ideas about human beings and their fundamental concerns, to discard the dominant discourses around these concepts, and to overlay certainties with skepticism.

Time of Love

Time of Love reviews a love triangle three times. In the first and the second times, it changes the situations of the characters and gets the same results. Rather than carrying messages, these changes are meant to create questions in the minds of the audience: is the situation dominating the individual or is it vice versa? If the situation prevails, what is the role of judgement? And finally, are human beings able to dominate the environment? To pose these questions, Muhsin Makhmalbāf uses the context of love and by doing so, he also defamiliarizes love and possessive readings of it.

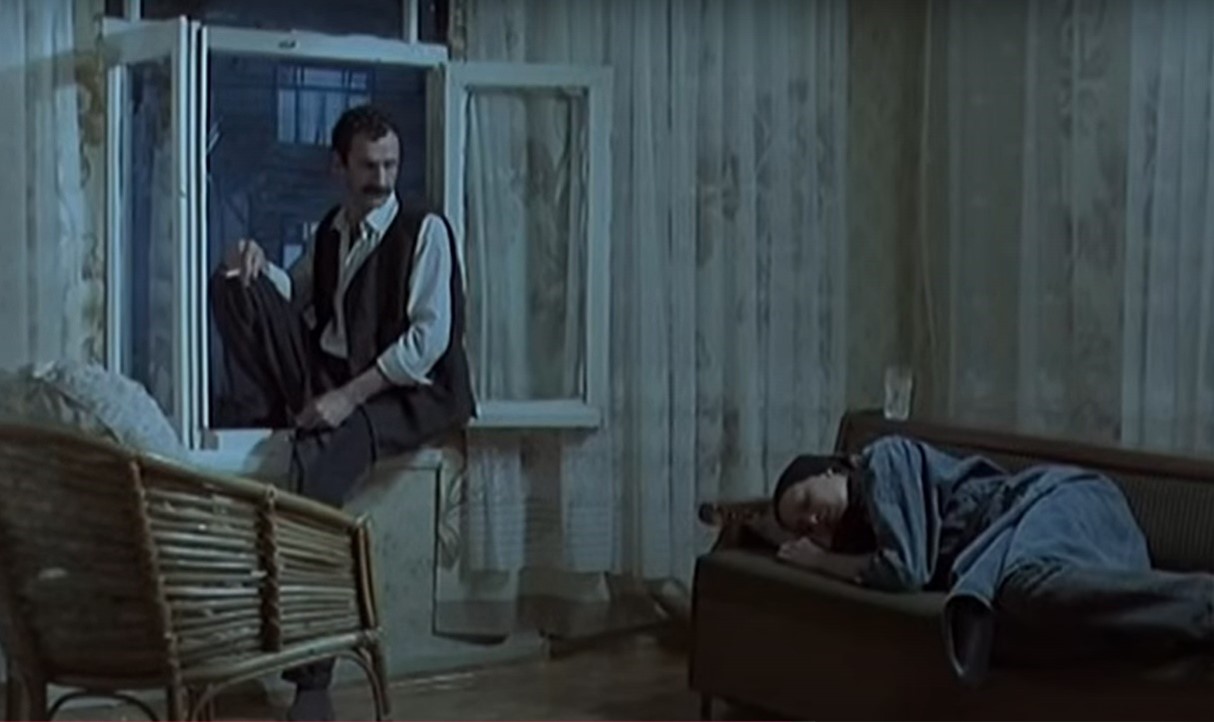

Figure 3: A still from the film, Guzal with her lover, Time of Love (1991), Muhsin Makhmalbāf.

The triangle of the woman, her lover, and her husband is recreated three times and marked with the passing of a train in front of the woman’s house. In the first situation, the woman’s husband, after becoming aware of his wife’s secret relationship, murders his rival, then surrenders himself to the court and is sentenced to death. In this situation, the husband finds his act legitimate as he has defended his nāmūs (sexual honor). In the second situation, in which the actors playing the roles of the lover and the husband have replaced one another, the husband is murdered by the lover who is later sentenced to death. In this situation, too, the lover finds his act legitimate for defending his love. In the third situation, which is an idealistic one, the husband, after finding out about his wife’s affair with another man, divorces his wife, attends their wedding and, finally, gives his taxi to them as a wedding gift and wishes them happiness. This situation portrays the individual’s will and his rebellion against traditional conventions.

Figure 4: A still from the film, the third situation: Guzal’s husband attends the wedding, Time of Love (1991), Muhsin Makhmalbāf. Accessed via: https://www.youtube.com/watch?app=desktop&v=G0jrI_k1RaQ (1:02:31).

There is no definite ending even in the third ideal situation. In the last moment, the woman says that she misses her former husband. This suspense and uncertainty make the audience ask whether it is possible to reach a definite conclusion from these three situations. In the last scene, the woman is standing in front of a moving train that conventionally marks movement between different situations, scenarios, and points of view. This scene creates an expectation for repetition in the plot and, therefore, emphasizes the uncertainty and impossibility of a final judgement. Nevertheless, what is certain in this film is its stand against a possessive notion of love. The writer/director has employed a character to represent this notion: an old man who roams a cemetery with a cage and a tape recorder. In all three situations, it is this old man who tells the husband that his wife is having an affair. The audience never learns about the old man’s background but, in various situations, finds him trying to own and imprison beauty and keep whatever he loves to himself. For instance, he records the singing of birds on a cassette tape, keeps canaries in a cage and cats within the enclosed spaces of his house. He is also the one who admonishes the husband to control his wife and to keep her in his own possession. We encounter the old man for the first time in the cemetery while he is putting a cage in front of a gravestone that has the shape of a book. The associations between being a man, being old, the cemetery, the stone book and the cage evoke the ideas of oldness, patriarchy, possession, tradition, and law. From this perspective, when in the last scene we see the old man walking on the railway tracks into the darkness of the night, it may be safe to assume that the director is reminding us of the progression of history, the rejection of past certainties, and the need for change. This change is also reflected in the old man’s last words, in which he confesses that he, too, has been in love with the woman and the canaries and the cages are all excuses.

Figure 5: A still from the film, an old man with a cage, talking to Guzal’s husband, Time of Love (1991), Muhsin Makhmalbāf. Accessed via: https://www.youtube.com/watch?app=desktop&v=G0jrI_k1RaQ (1:04:44).

It seems that the director forgives the old man in the last scene because the old man too is a lover, but does not know any other way to show his love. He understands love as possession, infected with jealousy. We see in the third situation that, when the husband tells him that he has left his wife so she could follow her passion, the old man takes his hearing aid out of his ears so he would not hear, as change is difficult for him. This forgiveness, however, does not mean that there is no need for change. The train and the ship as well as movements in the carriage and the automobile can be references to the need for motion and the passage of time, a reminder for change and the idea that possessive love has no place in the new world. By putting the audience in three situations, Muhsin Makhmalbāf manages to rebel against the possessive form of love, the certainty in judgement, and the inflexible readings of reality.

Narrative in Time of Love

Time of Love is not committed to a linear narrative or a classic plot. This is indicated by the absence of a single hero, the lack of coherent events that build toward a climax, the unavailability of information about the characters’ pasts, the lack of a resolution or a definite ending, and finally, by the cyclical and repeating form of the film. As Hūshang Hisāmī, journalist, critic, and film and theater director, notes:

In a constant shift between reality and unreality, the film resists turning into the cinematic representation of a dramatic plot in its classic sense. A dramatic plot is based on exigency, whether internal or external, in scenes and characters, and each scene is born from another scene. The most significant aspect of Time of Love is that it does not have a coherent dramatic structure.2Makhmalbāf, Gung-i khvāb dīdah.

In popular and classic storytelling, it is common practice to indulge the audience in the illusion of reality and direct their attention to the flow of the narrative by evoking their sympathy with one of the characters, generally the protagonist. In the narrative of this film, however, the situations are more significant than the plot. The film refrains from creating a coherent and straightforward narrative; for example, it does not show us how the shoeshiner and the woman fall in love or how the old man and the husband are related. It seems that Makhmalbāf has used this narrative style to remind the audience of their role as spectators. Instead of delivering a message, he invites the audience to contemplation and active engagement in a dialectic relationship with the film, instead of a one-way relationship.

Figure 6: A still from the film, Time of Love (1991), Muhsin Makhmalbāf.

This type of narrative (distancing effect narrative) is used by avant-garde filmmakers and writers to remind their audiences that the film is not a reality and should not stop them from critical thinking. This narrative style, by disrupting a coherent story based on a rigorous causal relationship, constantly reminds the audiences that they are watching an unreal work. The use of jumping cuts, handheld shoots even on a carriage, and unusual frames accentuate this deliberate style of representation. This type of composition in cinema emphasizes the unreality of the film, in contrast to continuous editing, which aims at keeping the viewers away from the process of making the film in order to evoke their empathy and acceptance of verisimilitude. Using this style of narrative reveals that the philosophical and intellectual situation is preferred over the story by the filmmaker. Nevertheless, this is a risky style because the audience may not be able to relate to the film, which would then relegate it to the category of artistic and intellectual films. As Jonas Mekas suggests, more than 90 percent of people do not like films, they like stories.3Peter Ward, Picture Composition for Film and Television (Focal Press, 2003), 19.

Despite the emphasis on the human and the complexities of human existence, the characters remain as types and do show complex, paradoxical dimensions, except in the third ideal situation, in which the change is too extreme and black and white. The husband and his choices are typical of a prejudiced traditional man; the woman remains a victim of the situations; the woman’s mother is a simple-minded ignorant woman; the shoeshiner is portrayed as a bold and romantic lover from a nineteenth-century novel; and the old man represents absolute evil and the shadow of oppression over the lover and the beloved. All these characters remain either black or white, and their choices and behaviors are flat and predictable. Only in the third situation, when the woman starts to feel complex romantic feelings for both her husband and her lover, her character bears some resemblance to the contemporary sophisticated human. The film’s disregard for paradoxical emotions and intricate human behavior is what makes the third situation ultimately unrealizable and rather cliché.

Time of Love: The Boundary between Reality and Unreality

Conventionally, a writer of a narrative work allows the audience, at the beginning, to know what type of work they are about to encounter. Amanda Boulter argues in Writing Fiction: Creative and Critical Approaches that the beginning of a narrative work is responsible for determining the type of story from the perspectives of genre, tone, style and language.4Amanda Boulter, Writing Fiction: Creative and Critical Approaches (Bloomsbury Publishing, 2007), 119. Centuries of encounters with narratives and almost a century and half of encounters with cinematic and visual narratives have created a set of implicit agreements between the audience and the writer/director. Disregarding these agreements, whether in their visual forms or in storytelling, could create a sense of frustration in the audience. Peter Ward believes that using alternative techniques in cinema

challenges the ‘realism’ of Hollywood continuity editing and aims for uncertainty, ambiguity, and unresolved narrative. This type of randomness and irrationality may cause an audience conditioned by the language of standard film making conventions to be confused and unresponsive. The film language is simply not one to which they are accustomed.5Ward, Picture Composition, 19.

Therefore, it seems necessary for the writer/director to share with their audience in the first steps the principles of the world they have created. One of the most important elements that should be revealed in the introductory phase is the commitment of the work to reality or its verisimilitude. The audience prepares itself to perceive the type of work it is encountering, whether fantasy, surrealism, realism, black realism, or magical realism. After the audience accepts the genre and the style of work, it could get disappointed or even feel deceived if the rules are broken.

In Time of Love the boundaries between reality/unreality and symbolism/realism are not clearly defined. In some parts of the film, the filmmaker is so committed to the real world that there is no music unless there is a singer or an instrument player in the plot. This commitment to realism signals to the viewers that they are watching a film in which even the addition of music is not allowed by its director. The audience, then, is bound to feel confused when it encounters the scene in which the blond man takes a dead fish from a frying pan and throws it in the sea and the fish becomes alive, as if love has revived it.

Figure 7: A still from the film, the blond man takes a dead fish from a frying pan and throws it into the sea and the fish becomes alive, Time of Love (1991), Muhsin Makhmalbāf. Accessed via: https://www.youtube.com/watch?app=desktop&v=G0jrI_k1RaQ (00:18:59).

Nor can the audience accept the unification of the old man and the husband at the end of the film because it has seen the old man in the real world having a real life. The old man has a body and a house. He follows people and is limited to time and space, because when his shoes are stolen, he cannot continue following the lover and the beloved. The old man, therefore, is not an abstract concept appearing in critical moments and watching from a distance and going away for the audience to think of him as a concept that has been actualized. Therefore, when the film presents a new reading of his existence and connects him with the shadow of the husband, it violates its own rules.

The filmmaker is much more committed to reality in the first two scenarios than in the last scenario. The first two scenarios present earthly events with consequences that go as far as the law and society. Therefore, the film, rather than being a subjective and internal narrative of the lover and the beloved, is focused on the moral and social situations of its characters. The philosophical structure of the film is based on verisimilitude since the film has a social and, in a sense, political philosophy, not a poetic or imaginative philosophy. The audience follows the events to find answers for worldly events. Nevertheless, the film changes tracks in the third scenario and moves away from the social reality toward an ideal reality. This change is so prevailing that it makes the judge in the third scenario confess, “none of us are real characters, you know. No one believes us.” The oscillation between the real and the unreal world can be frustrating to the audience, however, it can also be argued that the filmmaker has used this oscillation intentionally to make a point. Hūshang Hisāmī writes in his analysis, “in Time of Love, Makhmalbāf tries to show the ugly and the beautiful sides of love in both its real and mythological aspects according to an accurate understanding of the oscillation between reality and unreality.”6Makhmalbāf, Gung-i khvāb dīdah.

Characteristics of Framing and Composition in Time of Love

In Time of Love, Makhmalbāf makes use of appropriate cinematography techniques to invoke various feelings. For instance, the scenes that are meant to evoke domination or threat are shot with over-the-shoulder techniques. Two examples are the scene in the cemetery when the black-haired man and Guzal are making love and the old man enters from the left corner of the picture, and in the second and the third scenarios, when the husband enters the house after he has found out about Guzal’s secret relationship. In the latter scene, Guzal is sitting by the window when her husband enters, and the threat that she feels from her husband is shown with an over-the-shoulder shot. In the third scenario, it is exactly in this scene and after evoking this threat and domination that the black-haired man pulls out his belt and attacks Guzal.

Figure 8: A still from the film, the black-haired man pulls out his belt and attacks Guzal, Time of Love (1991), Muhsin Makhmalbāf. Accessed via: https://www.youtube.com/watch?app=desktop&v=G0jrI_k1RaQ (00:53:34).

Additionally, Makhmalbāf manages to create various emotions for an event by changing the angle of the camera, which helps the audience understand the event from different viewpoints. For example, the execution of the black-haired man in the forest is once shot from a high angle, which offers an external perspective on an execution that is void of any type of heroism. The same scene in another scenario is shot from a low angle to represent a sense of courage and bravery in the black-haired man, as though to reveal his internal feelings about being a martyr of love. This contrast in the angle of the camera is also used in a scene in the first scenario, where Guzal, after taking drugs (most likely with the aim of committing suicide) gets in a carriage in which a group of children are playing music. In this scene, the children are shown from a low angle from Guzal’s perspective, which accentuates her low and fragile status, while she is shown in this scene from a high angle. The camera is also placed on the carriage without vibration reduction. The shaking transfers to the audience Guzal’s feelings of imbalance, confusion, and suspense.

Figure 9 (Left): A still from the film, Guzal, after taking drugs (likely in a suicide attempt), sits in a carriage where children are playing music, Time of Love (1991), Muhsin Makhmalbāf. Accessed via: https://www.youtube.com/watch?app=desktop&v=G0jrI_k1RaQ (00:27:29).

Figure 10 (Right): A still from the film, Children playing music, Time of Love (1991), Muhsin Makhmalbāf. Accessed via: https://www.youtube.com/watch?app=desktop&v=G0jrI_k1RaQ (00:27:06).

In addition, Makhmalbāf has made ample use of change in shot sizes to show a specific subject from different dimensions and to give the audience the right to choose. In many scenes, we see one situation several times in long shot and again as close-up. This change in the shot size can be regarded as a means for the audience to have both an external and an internal look at the subject, i.e. from both perspectives of the characters and the external viewer.

Sex and Philosophy

Figure 11: A still from the film Sex and Philosophy (2005), Muhsin Makhmalbāf. Accessed via: https://www.youtube.com/watch?app=desktop&v=xuSOc4aaalo (00:23:39).

Sex and Philosophy is the story of a forty-year-old man who decides to revolt against himself. On his fortieth birthday, he invites his four lovers to a dance hall where he teaches dancing and confesses to them that he has been in a romantic relationship with all of them at the same time. The four women, Maryam, Farzānah, Tamīnah and Malāhat, each have their own color, dance, and symbolism (discussed further). Although it can be assumed from the title and the synopsis that Sex and Philosophy is a romantic film, it is in fact a film about the awareness of death. Love/separation, presence/absence, and birth/death are so intermingled in this film that the presence of one necessitates the presence of the other. It seems that the protagonist of Sex and Philosophy is concerned with lack of love rather than love itself. The film, then, is a journey of the hero from his denial of death and his loneliness to his acceptance of the two. Thoughts of death start with the first frame of the film, where forty candles are lit on the dashboard of the protagonist’s car as he is looking for two strolling musicians who remind him of his parents. During this search, he calls Maryam and asks her to come to the dance hall. The candles are put out and melted during this movement while he is trying to keep them lit.

The film reveals a poetic and imaginative atmosphere from the first scene. The metaphorically lit candles, the movement of the automobile, the protagonist’s attempt to keep the candles burning, and his search for people who revive the memory of his parents indicate an unstoppable instability. Time passes as the automobile moves; decay happens as the candles are put out and melt; and people look for shelter as the protagonist gives a ride to a strolling musician.

Figure 12: A still from the film, a bunch of burning candles inside the Jān’s car, Sex and Philosophy (2005), Muhsin Makhmalbāf. Accessed via: https://www.youtube.com/watch?app=desktop&v=xuSOc4aaalo (00:02:56).

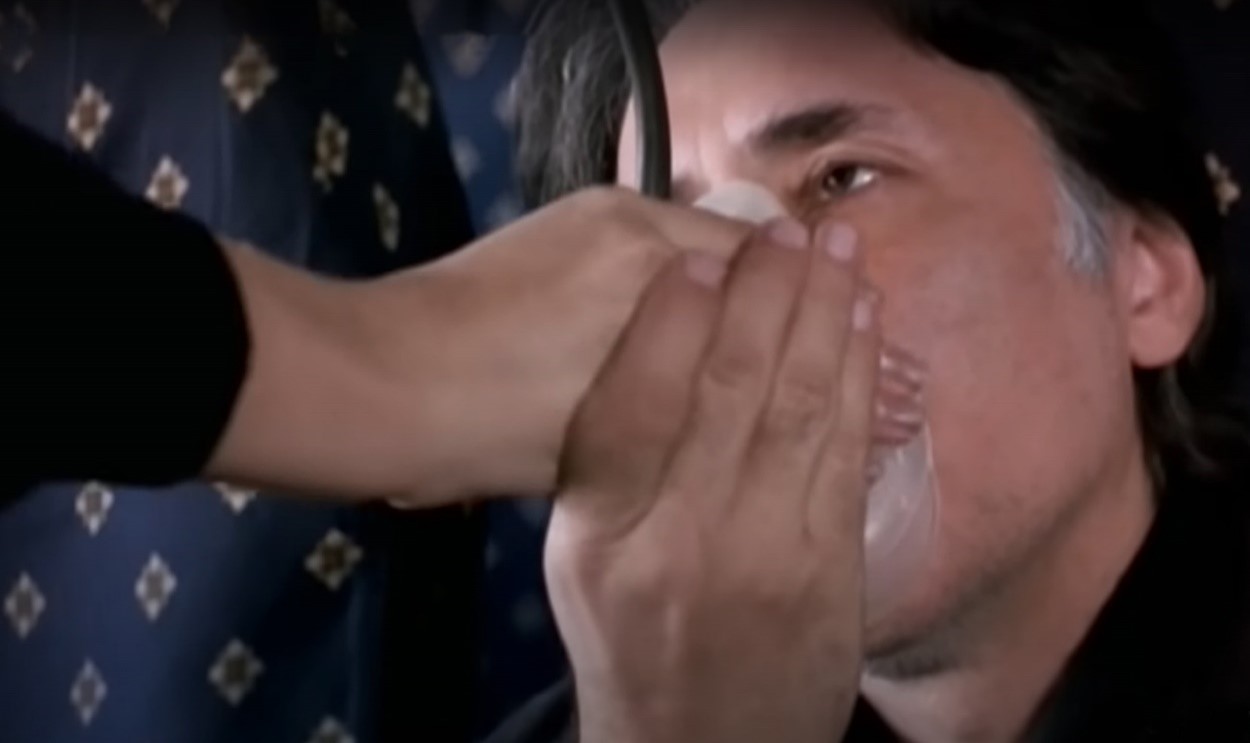

In this film, love is like a shelter in which the protagonist takes refuge from this movement and decay. In each of his love experiences, weakness, decay, and death are standing in the dark and staring at him. In his first love experience, when the protagonist feels suffocated on the airplane and Maryam, the flight attendant, puts the oxygen mask on his mouth, he puts his hand on Maryam’s hand and says, “Take the air from me but not your smile!” In his second experience, he falls in love with Farzānah exactly when his poet friend tells him, “Life is too short. You should not be ashamed of keeping it.” The third time, he is lying on the hospital bed and falls in love with the doctor who has come to treat him. In the fourth experience, we do not see how the protagonist has fallen in love with Malāhat, but we see her tell him in another scene, “You taught me that love is forgetting the sufferings of existence.” It seems that in all four situations, love starts at a point when existence is in danger.

Figure 13: A still from the film, when Jān feels suffocated on the airplane and Maryam, the flight attendant, puts the oxygen mask on his mouth, he puts his hand on Maryam’s hand and says, “Take the air from me but not your smile!”, Sex and Philosophy (2005), Muhsin Makhmalbāf. Accessed via: https://www.youtube.com/watch?app=desktop&v=xuSOc4aaalo (00:26:24).

There are other elements in the film that constantly remind us of the movement toward decay and the protagonist’s attempt to regain the lost time. One of the most significant visual elements is autumn. Throughout the film, the dry leaves not only help create a homogenous atmosphere but also remind us of the last season of life, “the Fall” of man, and decay. There are no images of spring in the film, even in flashbacks, as though the film’s world is entirely a timeless autumn. We see only one green tree throughout the film in a scene in which the protagonist and Maryam are talking about love and the short life span of butterflies. However, even in that scene, when the camera tilts down, we see the ground covered with yellow leaves among which a chronometer is counting the passing of time. This downward tilt, the dry leaves and the chronometer can also be a reminder of “the Fall” of man.

Chronometer is another element that accentuates the awareness of death in the film. The protagonist has a chronometer with which he registers his happy and fruitful moments. The constant presence of the chronometer emphasizes the passage of time and shows the protagonist’s attempts to freeze time and save it. That, however, is not his only attempt to preserve things that cannot be preserved. He not only keeps time in his chronometer and lights the dead candles again but also carves the picture of everyone with whom he falls in love on dried tree trunks. There is an emphasis in this act: taking refuge in love against death, which is represented by the dry tree in the picture.

Figure 14: A still from the film Sex and Philosophy (2005), Muhsin Makhmalbāf. Accessed via: https://www.youtube.com/watch?app=desktop&v=xuSOc4aaalo (00:43:59).

Scrutinizing Jān’s Love: The Mother Complex in Dionysian Men

Somewhere in Sex and Philosophy, Maryam asks Jān: “Is this love? With four people at the same time?” And Jān answers, “This is a quest. With each of you, I found a part of my own heart.”

Figure 15: A still from the film, When Maryam asks Jān: “Is this love? With four people at the same time?” And Jān answers, “This is a quest. With each of you, I found a part of my own heart.” Sex and Philosophy (2005), Muhsin Makhmalbāf. Accessed via: https://www.youtube.com/watch?app=desktop&v=xuSOc4aaalo (00:18:32).

Maryam’s question might be the question of any spectator of the film, since Jān’s romantic passion and poetic behavior with each of his lovers on the one hand, and his unfaithfulness and lack of commitment to them on the other hand, beg the question whether he is a real lover or just a pleasure seeker pretending to be a lover. To answer this question, we can refer to the theory of “love as story” by the psychologist Robert Sternberg in his book, Love Is a Story: A New Theory of Relationships (1998). Sternberg, R. J. (1998). Love is a story: A new theory of relationships. Oxford University Press. Sternberg identifies love as a cultural phenomenon transferred by memes, rather than an instinctive phenomenon passed down by genes.7Robert Sternberg, “A triangular theory of love,” Psychological Review 93, no. 2 (1986): 119–135. We learn how to love through exposure to stories, romantic songs, and romantic movies that are aligned with our identities. Therefore, in order to understand Jān’s love style, we have to identify the Dionysian “identity script” and its psychological complexes. In psychoanalytic texts, especially in the Jungian and Bolenian approaches, the characters of Greek mythology are used to categorize personality types. When a person repeats characteristics which have been associated with one of the Greek gods or other mythological figures, that person is identified with the name of that god; for example, men who are attracted to industrial works and craftmanship are called Hephaestus men, since Hephaestus is the god of craftsmanship in Greek mythology. Likewise, Dionysian men are those who have a strong tendency for mysticism, ecstasy, love, and poetry, since Dionysius is the god of wine, ecstasy and love. Dionysius, also called Bacchus, has intertextual relations in many of his characteristics with Jesus Christ, such as being born from a mortal mother and having a godlike father and sharing the significance of wine in the Lord’s Supper. Dionysius is the son of Zeus and Semele, daughter of Cadmus and Harmonia, and is therefore from the second generation of Olympian gods, like Hermes, Apollo and Artemis.8Pierre Grimal, The Dictionary of Classical Mythology (Blackwell, 1987), 128.

In Greek mythology, Semele, pregnant with Dionysius, is one of the mortal beloveds of Zeus. Hera, Zeus’s wife, tricks her into asking Zeus to appear to her the same way he appears to Hera. When Zeus appears to Semele with his godly image, she as the mortal being is not able to withstand the grandeur of Zeus and collapses on the ground and dies. Zeus immediately takes Dionysius out of Semele’s body and stiches the fetus to his own foot so that Dionysius would be born from his father’s foot in due time. This is why the child is called Dionysius which means “born again.” Although he is Zeus’s son, Dionysius leaves Greece for a long time and travels on earth to be safe from Hera’s wrath. When at last he is accepted as one of the gods and asked to go to Mount Olympus, he rejects the invitation because he is searching the world of the dead to find his mother, Semele, to take her with him to Olympus. Dionysius is always looking for a mother he has never had, therefore, the mother complex is common among the Dionysian men. These men seek in love a mother who has a high position and sanctity, and by finding her, they can distance themselves from this world and its sufferings and attain peace in the realm of gods.

In Sex and Philosophy, it is repeatedly emphasized that Jān is a Dionysian type of man. Poetry, wine, love, dance and ecstasy are all Dionysian motifs which appear everywhere in the film. Jān’s quest is for a return to maternal security, which is reflected in his very first search, i.e. looking for a couple who remind him of his parents. The search for a mother, the ethereal love, and the separation from one’s mother can be observed in his first love experience. The beloved is called Maryam, a name which is associated with the mother of another Dionysian prophet, Jesus Christ. Love happens on an airplane in the sky, reminiscent of ethereal love. In the first encounter, Jān speaks of his mother, “When I was a child, my mother taught me not to accept two things: first, a cold look; second, a cold coffee.”

Figure 16: A still from the film, Maryam brings coffee for Jān. Sex and Philosophy (2005), Muhsin Makhmalbāf. Accessed via: https://www.youtube.com/watch?app=desktop&v=xuSOc4aaalo (00:24:42).

Also, a significant dialogue is exchanged between Maryam and Jān in the dance hall which emphasizes the motherly position of Maryam. Jān says, “You said the flight takes an hour and the passengers are served with cold and hot drinks.” And Maryam responds, “I didn’t say that. It was a recorded message.” In this dialogue, Maryam is pictured in Jān’s mind as a mother who serves. What she serves is a drink, symbolic of the milk that the baby receives from the mother. But Maryam awakens him from the dream of this fake security by reminding him it was not her but a recorded message that made that statement. Where does this recorded voice come from in the symbolic world of the film? Is it a voice deep within the character or the voice that has created life in the beginning of the world? Maryam remains an ethereal love, just like the Holy Virgin, and considers physicality in love as possession.

Like Dionysius, Jān continues his quest for a mythological love but cannot find what he has lost because love for Dionysius has such a high position that cannot be found on earth. He constantly reminds us that his relationships cannot be called love because they are based on ordinary events and causal relationships, “Maryam! All loves are the result of a few mundane events. If I didn’t fly on that plane, or if you weren’t a flight attendant on that plane, this love would have never happened at all and today, two other people were separating from one another. Wait. Listen. I was looking for an earthly love in the sky. But your love stayed heavenly even on earth.”

Character Symbolism in Sex and Philosophy

One of the important points in Sex and Philosophy is that the filmmaker makes constant references to texts outside the film. First, we can focus on the reference to the four elements (air, earth, water, and fire) and their manifestation in the four lovers.

As discussed earlier, Maryam is associated with air, wind, and the sky. Her love is heavenly and ethereal, as signified by her name, which is reminiscent of the Holy Virgin. Jān meets Maryam in the sky and the dance that represents Maryam is light and performed with the movement of hands, similar to the moving of the wings. The use of red fans in her dance is another sign of the significance of the air and the wind. On the airplane, Maryam puts an oxygen mask on Jān’s mouth and practically breathes air into him. Another symbol of air, wind, and the flight in the story of Maryam and Jān is a butterfly that flies away and makes the two lovers talk about butterflies.

In contrast to Maryam, Farzānah is associated with soil and the earth. Jān falls in love with her steps and her most distinguished feature are her shoes. Farzānah wears shoes with different colors of red and white, an indication of her contradictory character. In one scene, she shows her shoes to Jān and asks him which shoe he has come after, the red one or the white one. This contradiction is evident in her moods, too. Farzānah is fluctuates between anger and love, and earthly and heavenly love. She tells Jān that when men are on the other side of the curtain, their hearts beat fast, but when they come to this side of the curtain, their love is subdued. It seems that the curtain which is the symbol of the physical relationship is the boundary between Farzānah’s two contradictory sides. In contrast to Maryam, her love is not thoroughly heavenly. It has come to earth but also misses the sky. Makhmalbāf seems to be identifying the earth with contradiction. Farzānah is hesitant between the desires of primitive physical relationship and ethereal love. When Jān calls her and invites her to the dance hall, he asks her not to bring her dog, as though the dog is the symbol of Farzānah’s violence and primitiveness. Farzānah says about her own contradiction: “I don’t like crying because the colors on my face will melt down and make me ugly. […] I don’t like love. I don’t like men when they are with me. When they leave me, I fall in love with them.” Farzānah’s contradictory character can also be seen in a scene in which Jān and Malāhat are drinking wine. Farzānah intervenes and pushes Malāhat away with violence. Then, she immediately takes Jān in her arms. The dance that represents Farzānah shows this duality, too. In this dance, one hand is toward the sky and the other toward the earth. Also, this dance is performed by stamping the feet on the ground and constant back-and-forth movements that bring to mind the paradox of earthly beings.

Figure 17: A still from the film, Farzānah shows her shoes to Jān and asks him which shoe he has come after, the red one or the white one, Sex and Philosophy (2005), Muhsin Makhmalbāf. Accessed via: https://www.youtube.com/watch?app=desktop&v=xuSOc4aaalo (01:06:04).

While Farzānah is hesitant between earthly/heavenly and physical/ethereal love, Tahmīnah is completely earthly and physical. From the four elements, she represents fire. This is manifested in a scene in which she asks Jān to go to the past and he reminds her that she gave him thirty-nine candles for his birthday last year. Tahmīnah is always pictured with a candle in her hand and is the only woman who is kissed in the film by Jān. In the kissing scene, a flame is leaping behind the lovers and their lips come together exactly where the flame is. Tahmīnah does not perform any dance. She is shown as sitting on the ground, meditating, because she is altogether earthly. She is a physician, a healer of physical pains and illnesses. She and Jān met in the hospital while Jān had been suffering from physical pain.

Figure 18: A still from the film, Tahmīnah pictured with a candle in her hand, Sex and Philosophy (2005), Muhsin Makhmalbāf. Accessed via: https://www.youtube.com/watch?app=desktop&v=xuSOc4aaalo (01:15:27).

And finally, Malāhat is water. She brings a drink to the dance hall. She is flexible and throughout the film, while the other lovers are angry, she keeps smiling. More importantly, she is the reflection of Jān. At the end of the film, when we see that she has also been in four simultaneous relationships with four men, we realize that Malāhat is a feminine picture of Jān and like water, shows him a reflection of himself.

The presence of these four elements accentuates the idea that Jān is looking for something that is not material in these elements, since in ancient Greece, it was believed that different types of matter are made by different combinations of the four elements. Jān looks for love in water, air, earth, and fire while constantly repeating that those experiences are not love but accidents, contracts, escapes, and quests. For him, love is a lost object which he cannot find in matter.

Figure 19: A still from the film, Malāhat in four simultaneous relationships with four men, Sex and Philosophy (2005), Muhsin Makhmalbāf. Accessed via: https://www.youtube.com/watch?app=desktop&v=xuSOc4aaalo (01:31:45).

Objects is Makhmalbāf’s Films

The significance of objects is one of the characteristics which renders a poetic aspect to Makhmalbāf’s cinema and separates it from mainstream popular cinema. The objects and the accessories in his pictures have a function beyond the usual stage props and tools for storytelling, as many of them represent a feeling, a message or an abstract subject; therefore, their presence is accentuated, whether in the screenplay and the dialogues or in the framing and composition of the picture. This emphasis is obvious in frames in which an object is in the middle of the picture or in close-up, such as the scene in Time of Love where a cage is put in front of a stone book, or the scene in Sex and Philosophy where a chronometer is put among leaves under a tree.

In Time of Love, Makhmalbāf pictures the joining of the lover and the beloved with the interweaving of their shawls in the wind. Immediately in the next scene, the husband appears with a steering wheel lock in his hand. This represents the contrast between the soft and flexible objects that symbolize love and the hard, metal, and sharp objects that symbolize prejudice, violence, and inflexible laws. In both courts in this film, we see these objects on the judge’s table and he emphasizes them by picking them up. Also, in the first court, after the judge signs the death sentence, he immediately breaks the pen. The director explains that it is a custom in Turkish courts to break the pen with which a death sentence is signed. While this is an extratextual explanation, in the film itself, breaking the pen might be interpreted as the judge’s uneasiness with the execution or the filmmaker’s outlook on the death sentence.

Figure 20: A still from the film, in the first court, after the judge signs the death sentence, he immediately breaks the pen, Time of Love (1991), Muhsin Makhmalbāf. Accessed via: https://www.youtube.com/watch?app=desktop&v=G0jrI_k1RaQ (00:23:40).

In Sex and Philosophy, the significance of objects is even more highlighted as certain things have a major role in creating the atmosphere of the film, including candles, keys, dried tree trunks, a chronometer, wine glasses, a bottle, roses, an umbrella, yellow leaves, a gramophone, shoes, and a newspaper. Each of these objects has an implication and a role in the film: the chronometer, the lit candles, the leaves, and the dry trees represent the shadow of death, the passage of time, and decay, while roses, shoes, the red coat, and wine emphasize the physical dimensions of love, and umbrella and handing it over by the lover to the beloved evokes feelings of intimacy and support.

There is a well-known phrase that says love means making the world as small as one person and making one person as big as the world. Using a newspaper as the beloved’s towel in a scene in Sex and Philosophy can easily bring this sentence to mind and show how an object is given a role beyond its usual use. The different aspects of a woman are also depicted with the different colors of her shoes. Moreover, the first signs of the acceptance of decay and loneliness is in the scene in the dance hall in which yellow leaves are covering a wine bottle.

Figure 21: A still from the film, Wine glasses, an object repeatedly featured throughout the film, Sex and Philosophy (2005), Muhsin Makhmalbāf. Accessed via: https://www.youtube.com/watch?app=desktop&v=xuSOc4aaalo (00:17:15).

Conclusion

There are characteristics in Makhmalbāf’s cinema that give it poetic and philosophical dimensions and separate it from mainstream popular cinema. In this article, we studied these characteristics from the perspectives of symbolism, composition, editing, storytelling, and philosophy. Arguably, the prominence of myths, unusual compositions, ambiguous uses of objects, the use of dance for showing character traits, the use of circular and episodic plot, the extratextual references, the merging of reality and unreality, the use of open ending and the preference of doubt over certainty are among the elements that separate Makhmalbāf’s cinema from the mainstream cinema in Iran. These characteristics give a poetic and imaginative quality to his films and help categorize him as an avant-garde and innovative filmmaker.

Cite this article

Muhsin Makhmalbāf (b. 1957) is a revolutionary filmmaker in the full sense of the word. At seventeen, he was a political revolutionary and served five years in prison because of it. But Makhmalbāf also made a revolution against himself and his former beliefs and values, as he later broke away from his religious and ideological framework and moved toward human values and ethics. The result of this internal revolution is manifested in his cinema, both in content and form. Shabhā-yi Zāyandah-Rūd (The Nights of Zāyandah-Rūd, 1990) and Nubat-i ‘Āshiqī (Time of Love,1991) were iconoclastic films in the ideological atmosphere of Iran after the establishment of an Islamic state in 1979. Both films were attacked and banned, and since 2001, he has not been able to make films in Iran. Makhmalbāf’s inner journey was reflected in his immigration from Iran in 2005. It is the unconventionality of his films that distinguishes his cinema from the mainstream popular cinema in Iran and enriches his films with poetic and at times Avant-garde aspects. Time of Love (1991) and Siks u Falsafah (Sex and Philosophy, 2005) share the subject matters of love and philosophical questions. The first film was thought to be breaking the moral frameworks in the highly ideological environment of Iran after the establishment of the religious state, and its deep philosophical aspects were overlooked. Sex and Philosophy, on the other hand, was made in Tajikistan and, because Makhmalbāf had turned into an internationally recognized filmmaker at the time of its production, the philosophical aspects of the film were observed more clearly. In this article, the two films are discussed in relation to their dramatic contents as well as cinematic forms. Eventually, we undertake a content analysis of the two films from psychological and existential approaches to clarify the poetic and symbolic aspects of Makhmalbāf’s cinema.