Beyond Stories and Facts: On Abbas Kiarostami’s ‘Documentary Objects’

Figure 1: Portrait of ‛Abbās Kiyārustamī.

‛Abbās Kiyārustamī’s work has often been praised for displaying at once formal simplicity and sophisticated emotional registers. This simplicity can be observed both in Kiyārustamī’s acclaimed narrative work and in the relatively less known documentary films that he has produced throughout his career, from Homework (1989) all the way to 24 Frames (2017), released just after his untimely death. Precisely because of the trademark combination of formal austerity, mundane subject matters and restrained plot structures, Kiyārustamī’s narrative filmmaking has been variously described as having a documentary quality,1Hamid Dabashi, Masters and Masterpieces of Iranian Cinema (Mage Publishers, 2007); Alberto Elena, The Cinema of Abbas Kiarostami (Saqi Books, 2005). and is at times associated with the stylistic manner of Italian neo-realism.2Bert Cardullo, André Bazin and Italian Neorealism (Bloomsbury, 2011); Stephen Weinberger, “Neorealism, Iranian Style,” Iranian Studies 40, no. 1 (2007): 5-16. This is certainly the case if one looks at his so-called “Koker trilogy,” which includes Where Is the Friend’s Home? (Khānah-yi dūst kujāst? 1987), Life, and Nothing More (Zindagī va dīgar hīch, 1992) and Through the Olive Trees (Zīr-i dirakhtān-i zaytūn, 1994). Set in and around the small village of Koker (Kukir), in the northwest of Iran, the three films deliberately intertwine fictional moments and factual elements, including the 1990 Manjīl–Rūdbār earthquake, which provides the impetus for the second chapter of the trilogy, Life, and Nothing More (1992). In his film-philosophical analysis of Kiyārustamī’s work, Mathew Abbott emphasises the Iranian director’s play between simplicity and reflexivity. Commenting on Where Is the Friend’s Home?, Abbott writes: “the simplicity of the film is part of its appeal, but it prefigures the crucial problem of Kiarostami’s later cinema: the question of the real and its relation to the fake (a relationship complicated by the film’s ending, in which Ahmad gets Mohammad off the hook by copying his own work into his book).”3Mathew Abbott, Abbas Kiarostami and Film-Philosophy (EUP, 2018), 3. Audiences worldwide have come to associate Kiyārustamī precisely with this intertwining of expressive dimensions. Departing somewhat from this framework, this article contends that it is possible to push the analysis even further, in order to detect in this trajectory further transgressions of the dichotomy between documentary and fiction. Expanding on and moving beyond the critical framework that describes Kiyārustamī’s cinema in terms of simplicity and documentary aesthetics, this article reads his work in light of the role played in his films by what I will call ‘documentary objects.’ These everyday presences—from the notebook in Where Is the Friend’s Home, to the rolling spray can in Close-Up (1990), to the football in the short Take Me Home (2016) and the various animals and objects of Five (2003) and 24 Frames (2017)—appear in the director’s narrative and documentary work alike, but do perform radically different roles depending on their placement and the film’s context. The argument developed here is therefore twofold: on the one hand in Kiyārustamī’s narrative work, ‘documentary objects’ pull the films towards the factual mode, connecting with the idea of cinema as expressing our sheer interest in the world’s ordinary manifestations, thus interrupting narrative and dramatic constructions. On the other hand, the insistence on ‘documentary objects’ in films such as Five (2003) or Take Me Home (2016) and 24 Frames (2017) produce a leap beyond the factual register, projecting the idea of cinema as a perceptual exercise, a form of re-enchantment and magic that transfigures the world of the everyday.

Objects of Cinema

Objects have been a primary concern for film ever since its inception. Born out of the desire to achieve technologically a full (or at least as full as possible) rendering of the world (what Bazin used to call “the myth of total cinema”), the cinema has never stopped animating our craving to see things as they are, at times also to see them abandon their functional roles to emerge in their scintillating autonomy. The early film theorists devoted a great deal of attention to this, which they considered to be one cinema’s greatest assets (in some cases its essence). As Stern writes, “the cinema, since its inception, has always had a curiosity about the quotidian, a desire to scrutinize and capture the rhythms and nuances of everyday life, to capture (or be captured by) things. This is what Jean- Louis Comolli refers to as ‘the force of things.’”4Lesley Stern, “Paths That Wind through the Thicket of Things,” Critical Inquiry 28, no. 1 (2001): 324. However, Stern notes that at the same time, the cinema has been driven by a tendency to theatricalization, “by stylization, by processes of semiotic virtuosity.”5Lesley Stern, “Paths That Wind Through the Thicket of Things,” Critical Inquiry 28, no. 1 (2001): 324. Writers from Béla Balázs and Vachel Lindsay to Walter Benjamin, Jean Epstein and Sergei Eisenstein, all emphasised this ability of cinema to bring us into a renewed, mechanical contact with things. In her volume Savage Theory, Rachel Moore offers an overview of early film theory fascination with objects:

In one of Lindsay’s enthusiastic reviews of cinema, he remarks, “Mankind in his childhood has always wanted his furniture to do such things [to move on their own accord].” This “yearning for personality in furniture” is a theme throughout early film theory. Balázs finds that in cinema things are as expressive as faces. Siegfried Kracauer sees the surface attraction of cinema’s mass ornament as a thing, but a thing that resonates with people’s thinglike experiences, and is therefore attractive; it draws the spectator toward it. It is a very lively thing.6Rachel Moore, Savage Theory: Cinema as Modern Magic (Duke University Press, 2000), 8.

Filmmakers have often centred objects in their work, in ways that have turned the least remarkable everyday commodities into the very building blocks of film history. From Chaplin’s boiled shoe, to Welles’ sledge and Bogart’s cigarettes, from De Sica’s bicycles to Panāhī’s white balloon, from Hitchcock’s rope to countless other cursed things in the films of Italian horror masters Bava and Argento. Objects are often projected beyond their immediate function into a broader context to serve as narrative devices. A great deal of emotional investment is projected onto them: characters cannot leave them behind, but neither can they completely possess them, or if they do, their possession is the cause of much suffering. In other genres, specifically, but not only science fiction, objects become so completely intertwined with humans as to become part of the human body (or the human becomes part of a technological assemblage). At least since Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927) then, the history of cinema is replete with objects that have human features, possess human-like intelligence, behave and move like humans. As Elizabeth Ezra aptly writes, these human objects and techno-natures are regarded with a mixture of awe and horror, precisely because their independence is both formidable and sought after.7Elizabeth Ezra, The Cinema of Things: Globalization and the Posthuman Object (Bloomsbury, 2018), 27.

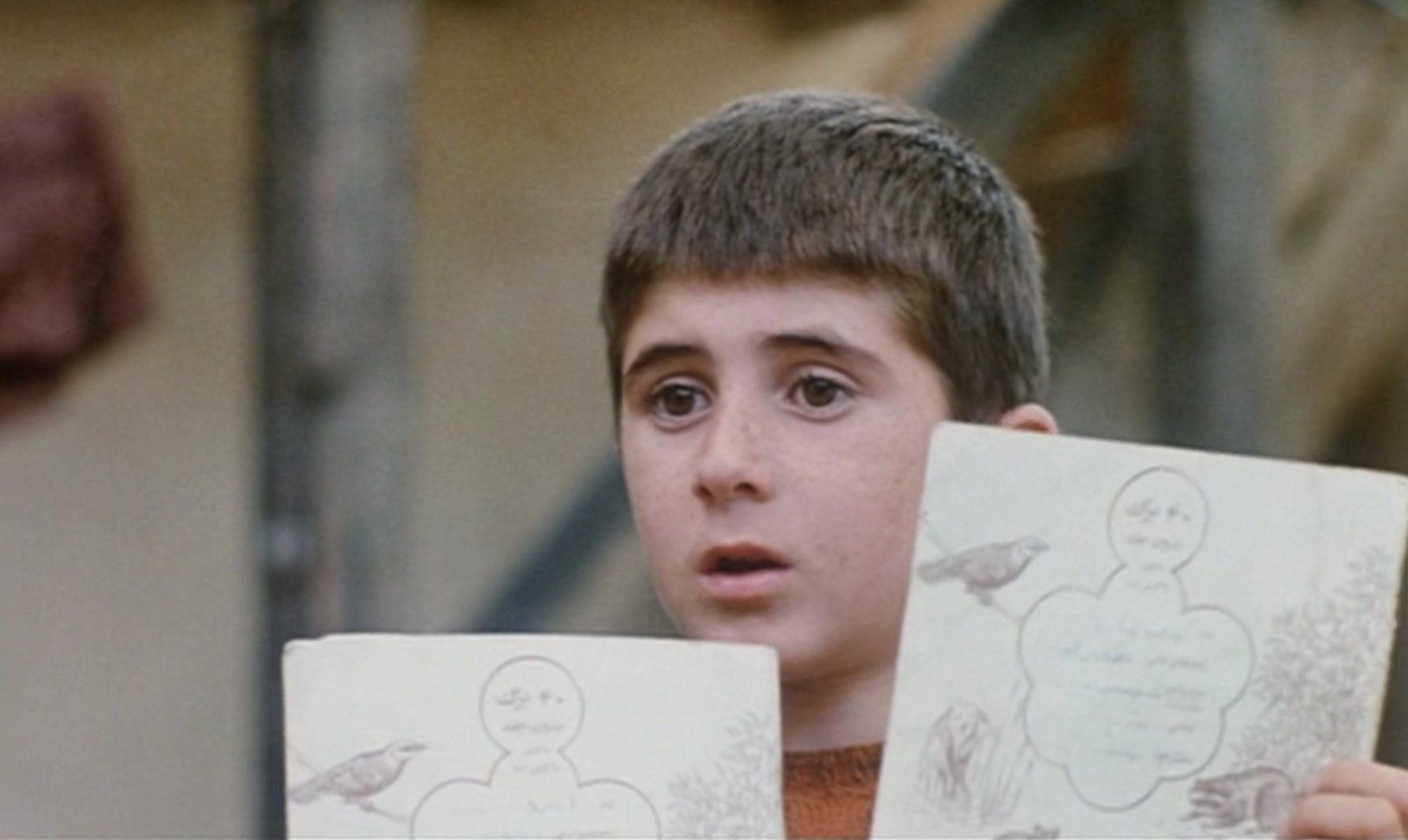

Figure 2: Ahmad showing his mother the two identical notebooks in Where Is the Friend’s Home? (Khānah-yi dūst kujāst?), directed by ‛Abbās Kiyārustamī, 1987.

Kiyārustamī’s Objects

‛Abbās Kiyārustamī’s cinema is full of objects, starting with the nearly omnipresent football of The Traveler (Musāfir, 1974), his first feature film. In a number of his works, objects perform a more traditional narrative role. As mentioned, the history of cinema is partly also the history of objects that have offered the occasion for stories and narrative excuses. Stern offers a taxonomy of such objects, citing Aragon on cinema’s ability to “raise to a dramatic level a banknote on which our attention is riveted, a table with a revolver on it, a bottle that on occasion becomes a weapon, a handkerchief that reveals a crime, a typewriter that’s the horizon of a desk.”8Lesley Stern, “Paths That Wind Through the Thicket of Things,” Critical Inquiry 28, no. 1 (2001): 334. This function of the object is one that Kiyārustamī also makes use of. The notebook that Ahmad has taken accidentally from Muhammad Rizā in Where Is the Friend’s Home? is a perfect example of objects’ narrative function. The misplaced notebook sets off Ahmad’s journey and becomes the engine of the plot. Returning the object to its owner is of primary importance for the conscientious Ahmad, and so the notebook becomes the narrative device for his adventure. In order to overcome his mother’s reluctance to let him go on his quest, Ahmad shows her the two identical notebooks. The two objects, however, fail to move her, and she remains firmly opposed to Ahmad’s plans. As his mother leaves the scene, Ahmad manages to sneak out of the house, not after having once again taken the wrong notebook. The fact that the two objects are identical—and that they can so easily be confused and so swapped—is a well-known narrative trope as is the motif of the mistaken identification of something.

However, I contend that there is more to Kiyārustamī’s objects than their mere narrative function, and this ‘more’—this surplus—is worthy of attention for at least two reasons. On the one hand, it offers the opportunity to analyse something of critical importance to Kiyārustamī’s filmmaking, and on the other, it also allows us to look once again into the relation between cinema and objects. In the following pages, I will consider a number of other objects that appear in Kiyārustamī’s films and analyse their function in fictional and documentary work.

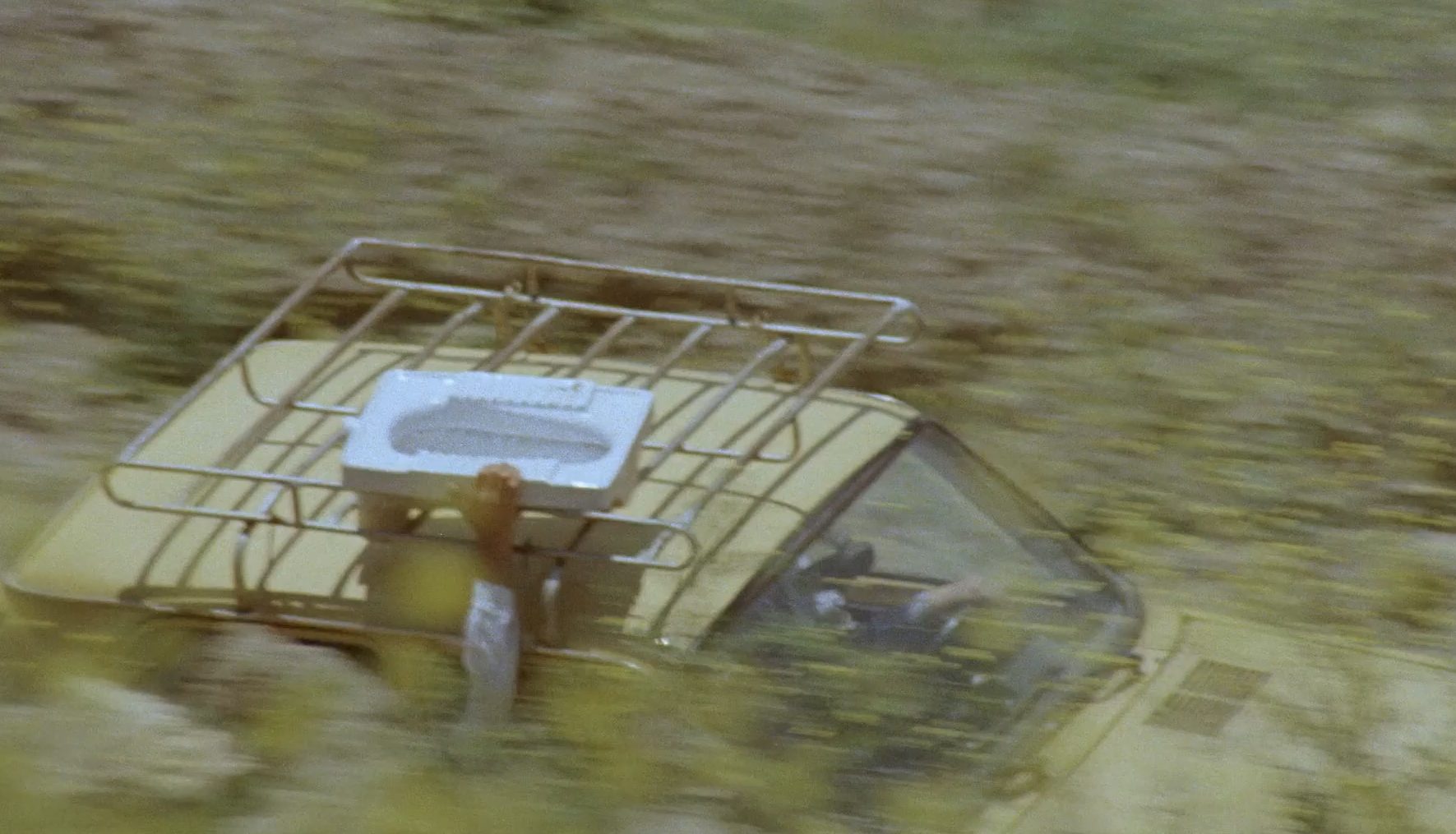

Figure 3: The squat toilet on the roof of the car in Life, and Nothing More (Zindagī va dīgar hīch), directed by ‛Abbās Kiyārustamī, 1992.

A Piece of Porcelain

Discussing his film Five, Kiyārustamī has articulated an approach to ordinary things, a way of looking at them: “I think we should extract the values that are hidden in objects and expose them by looking at objects, plants, animals and humans, everything.”9Around Five, directed by ‛Abbās Kiyārustamī (2005; London: BFI), DVD. There are many instances of objects taking centre stage in Kiyārustamī’s work, and these are often filmed following recurring compositional strategies. As Donna Honarpisheh acknowledges, “films in Kiarostami’s cinematic oeuvre such as Close-up (1990), Taste of Cherry (1997), and The Wind Will Carry Us (1999), to name a few, incorporate the long take to follow the movements of small objects as they traverse the earth’s windy landscapes. In these instances, our perception is oriented towards objects that would otherwise occupy the narrative’s background.”10Donna Honarpisheh, “Waves of Stasis: Photographic Tendency and a Cinema of Kindness in Kiarostami’s Five (Dedicated to Ozu),” Iran Namag 2, no. 4 (2018): 52-53. In Life, and Nothing More, we have various paradigmatic instances of this, with Kiyārustamī using the car, among other things, as a device to transport objects. In the first third of the film, as the director and his son try to find the way to Koker among the roads destroyed by the earthquake, they meet a group of women and children who are proceeding on foot. The two stop the car to ask for directions and end up loading a gas cylinder on the roof of the vehicle. Kiyārustamī cuts from a medium to a wide shot, showing the object travelling through the landscape on top of the car, before it is left by the side of the road, as requested by the owner. Shortly after, the two meet a man, who is walking and holding on his shoulders what remains of a squat toilet. The man loads the toilet onto the car’s roof and enters the vehicle. As the conversation progresses, we learn that the gentleman is familiar with the director, for having been involved in the shooting of Where Is the Friend’s Home. We also learn that he has lost everything in the earthquake, apart from the toilet that he carries with him. The dialogue then focuses on the object. As the director asks the reason why the man is carrying this object, his answer is as follows: “It is not polite to say, but it is obvious what it is used for! Everyone knows what its job is. The ones who died are gone, but those who are alive need this valuable piece of porcelain.” As the conversation continues, the shot remains on the porcelain, which becomes very much the visual focus of the sequence, as the car once again cuts the landscape diagonally, from the bottom-left corner to the top-right corner of the frame. At some point, the hill cuts off the bottom of the car, so that only the roof is visible, and for a few seconds, we get the impression of a porcelain toilet travelling on its own through the hilly landscape. This sequence contains in a nutshell much that will be developed in this article: a mundane object is isolated by the visual composition and brought to prominence, in a way that disrupts the narrative in favour of a focus on the factual register, here exemplified by the object. The latter’s relative autonomy, emphasised by the framing, brings it to our attention in ways that force us to shift attention away from the story and its development, in favour of its presence.

Figure 4: The rolling spray can from Close-Up, directed by ‛Abbās Kiyārustamī, 1990.

A Rolling Can

Close-up is arguably one of Kiyārustamī’s better known and most widely seen films. One could even go so far as to say that its peculiar blend of documentary interviews, reenactment and fictional elements has become exemplary of Kiyārustamī’s filmmaking. The film has inspired various other directors, who more or less explicitly have sought to revive its formal strategies,11The Italian director Nanni Moretti has released a short film, The Opening Day of Close-up (La Sera della Prima di Close-up (1996)), which is in many ways an homage to Kiyārustamī’s film. and has contributed a great deal to cement Kiyārustamī’s reputation outside of Iran as one of the most significant directors of his generation. The film’s main narrative is well known: Husayn Sabziyān, a man of poor means but with a great passion for cinema, passed himself off for the real film director Muhsin Makhmalbāf. The imposter managed to convince a family (the Āhankhāh) that they were the actors of his new film and even began rehearsing in their living room. Once the imbroglio is discovered, Sabziyān is jailed and trialed for fraud. When he is finally freed, he is picked up outside the prison by the real Makhmalbāf, who gives him a ride back to the Āhankhāh’s house. The film is structured like a fairly conventional narrative film, and despite the documentary elements (Kiyārustamī obtains permission to film the actual trial and at some point interviews the fake director in jail in a setup that is reminiscent of traditional documentary interviews), it has the structure of a fiction. The film opens with a journalist travelling in a taxi to the Āhankhāh family home. As he arrives at his destination, the taxi driver waits outside the house. At some point, the latter gets out of the car and he begins to look into a pile of dry leaves, from which he picks wild flowers. He also notices a green object, which turns out to be a spray can. As he lifts one of the orange and red flowers, the can falls from the pile and rolls onto the street. At this point, the driver’s attention turns to the can, which he kicks away from the bush. The camera seems to hesitate for a moment, before turning away from the man and following the can as it rolls, now the sole subject of the camera’s attention and isolated from everything else. After a second, we would expect the camera to move away from the apparently uninteresting object and its motion, back to the man and his flower arrangement. However, Kiyārustamī stays with the camera, disrupting the narrative flow, diverting the audience away from the plot and the events of the film, to witness the rolling of the can. The camera stays with the can; it pans slightly to make sure that the object remains in the frame, very clearly visible, until this ends its run against the raised footpath. Confirming the narrative suspension in favour of the factual register operated here by Kiyārustamī, French philosopher Jean-Luc Nancy, in his magisterial text on the director, writes: “like a movement that would exit from the film properly speaking (from its script, from its topic), but concentrate the property of kinematics or kinetics in its pure state: a little bit of motion in its pure state, not even to ‘picture’ motion pictures, but rather in order to roll up or unwind in them an interminable driving force.12”Jean-Luc Nancy, The Evidence of Film: Abbas Kiarostami, trans. Christine Irizarry and Verena Andermatt Conley (Yves Gevaert Éditeur, 2001), 26-28.

A similar occurrence happens in The Wind Will Carry Us (Bād mā rā khvāhad burd, 1999), where a green apple fallen from the hand of the main character, who had just finished washing it, begins to roll on the ground. Kiyārustamī deliberately follows its random rolling, including a change of direction, and once again, one experiences a suspension of narrative momentum.

Figure 5: The rolling apple from The Wind Will Carry Us (Bād mā rā khvāhad burd), directed by ‛Abbās Kiyārustamī, 1999.

Interruptions

A number of preliminary conclusions can be drawn from this first part of the analysis. There are two ways in which we tend to encounter objects in so-called fiction/narrative films. Objects can be part of the decor, props that increase the realism of a scene. They are not meant to be acknowledged; they are self-evident, so they are seen in an implicit, intuitive way. They corroborate, lend verisimilitude and give substance to the mise-en-scène, and might even become part of the iconography of a genre (this is true for genres as different as melodrama, horror and noir). For some directors, this has to be done in very specific and most literal ways. We know, for instance, that the Italian director, Luchino Visconti used to fill drawers with real things (bed linens, towels and so on) even if it was clear that these drawers would never be opened nor become part of the scene.13Alexander Garcia Duttmann, Visconti: Insights into Flesh and Blood, trans. Robert Savage (Stanford University Press, 2008), 113. More generally, objects remain invisible until they become narrative elements. In his examination of objects, Stern writes that the Maltese Falcon of the eponymous film “is a thing that makes other things (things of a different order) happen; that is to say, its value is functional, and its function, inflected within an emblematic or hermeneutic register, is primarily narrative.”14Lesley Stern, “Paths That Wind Through the Thicket of Things,” Critical Inquiry 28, no. 1 (2001): 318. This is how we encounter most objects in narrative films. They become part of the story being told. In the case of the Maltese Falcon, they become even the fulcrum of that narrative. But the object, as Stern says, continues to have “both a fictional and documentary identity.”15Lesley Stern, “Paths That Wind Through the Thicket of Things,” Critical Inquiry 28, no. 1 (2001): 318. Kiyārustamī is very much aware of this and uses this ambivalence to great effect. There is a subversiveness to his use of objects in fictional film that finds a parallel of sorts in his factual and experimental work. The choice of objects is also peculiar. Kiyārustamī’s objects, for instance, do not seem the kind of objects that Stern calls “cinematically destined,”16Lesley Stern, “Paths That Wind Through the Thicket of Things,” Critical Inquiry 28, no. 1 (2001): 335. and include “telephones, typewriters, banknotes, guns, dark glasses, coffee cups, raindrops and teardrops, leaves blowing in the wind, kettles, cigarettes.”17Lesley Stern, “Paths That Wind Through the Thicket of Things,” Critical Inquiry 28, no. 1 (2001): 335.

It is not about objects as narrative devices, but rather objects as pure factual presences, with a life independent of that of the camera and, therefore, capable of attracting our interest, regardless of and beyond our investment in the narrative. Rather than producing or supporting a narrative movement, the objects suspend the narrative’s momentum and divert our attention. This is a narrative cinema that is moved by the world’s presencing, and that, therefore, builds moments within the narrative that move beyond storytelling, that fixate us onto the life of objects.

Figure 6: Ducks walking from Five, directed by ‛Abbās Kiyārustamī, 2003.

Ducks in a row

The second part of this article considers Kiyārustamī’s explicitly factual work—films that present no explicit or recognizable narrative elements and seem closer to the documentary mode. Here, I will analyse the role played by everyday documentary objects in Kiyārustamī’s factual corpus, starting with Five (2003). This is a deceptively simple film that takes place around water, each section, however, presenting a slightly different focus. Five is also a film of recurring compositional strategies, perfectly exemplified by the first fragment: here, Kiyārustamī divides the screen horizontally into three areas—the sea at the top, the wet sand in the middle, and the dry sand at the bottom. In this fragment, a piece of wood, possibly a branch, rolls on the waves of the sea until a segment is detached. At this point, Kiyārustamī keeps both pieces within the frame, until only the smaller part of the branch remains, whilst the larger segment drifts into the water. Part 2 focuses on a boardwalk overlooking the waves. The frame is again divided into a series of horizontal strips (sky, water, and boardwalk), where men and women, singly, in pairs, and in groups, cross the frame from right to left or left to right. Parts 3 and 4 focus, respectively, on a group of dogs and a number of ducks and geese that move from left to right though the frame in single file. In the final segment, Kiyārustamī stands close to the water’s edge and tracks the reflection of a full moon on the surface of the sea. Alberto Elena calls this film “radical,”18Alberto Elena, The Cinema of Abbas Kiarostami (Saqi, 2005), 183. and in many ways, that is the right word to describe it. There is no narrative, no character, no theme, and no reflection on modern-day Iran. In fact, there is absolutely no development in the film. Kiyārustamī seems intent only on capturing, as factually as possible, the situation that unfolds in front of the camera. The fact that the film is dedicated to the Japanese master filmmaker Ozu is perhaps telling in that Kiyārustamī is situating his work within a tradition of minimalist compositions, but also within what one could call a contemplative approach to cinema. As Abbott recalls, “Kiarostami himself makes a few connections when asked about this in Around Five: the use of the long shot; simplicity; respect for the audience and its intelligence, which in Kiarostami’s terms means something like restraint, the avoidance of emotional manipulation.”19Mathew Abbott, Abbas Kiarostami and Film-Philosophy (EUP, 2018), 80. It is not surprising then to read Scott McDonald calling Five “a series of perceptual experiences” and writing of Five as Kiyārustamī’s film “that most resembled the tradition of landscape filmmaking epitomized by Larry Gottheim’s early films, and much of the work of James Benning, Sharon Lockhart, and particularly, Peter Hutton.”20Scott MacDonald, The Sublimity of Document: Cinema as Diorama (OUP, 2019), 207.

Figure 7: The rolling football from Take Me Home, directed by ‛Abbās Kiyārustamī, 2016.

Errant footballs

Take Me Home (2016) is perhaps even simpler than Five, since the action all takes place in one setting and focuses on one object: a rolling football set against the stark black and white contrast of a village in southern Italy. Kiyārustamī here films a football that drops and rolls through what seems like an endless set of stairs and alleyways. On the way, the ball encounters three cats, a dog, and two birds. By the directness of the light and the sharpness of the shadows, we can deduce that most of the filming would have taken place late morning early afternoon, somewhere in the south of Italy. The village is deserted, but for the above-mentioned animals, who react in different ways to the passage of the ball. Kiyārustamī uses visual effects and even incorporates his own photographs, which are then blended with live footage. The edits—mostly match-on action cuts—are minimal and almost all coincide with the ball moving out of the frame and then reappearing. The film is bookended by the owner of the ball, a child who first positions the ball on his doorstep before this starts its descent and, at the end of the film, picks it up and walks away, holding it under his arm.

The interplay of chance and predetermination, the trajectory of a moving object within a static shot, makes it so that Take Me Home can be seen almost as an extension of the rolling aerosol can fragment in Close-up. However, here the role played by the ball is, in a sense, the opposite. Whilst the rolling can in Close-up brings the viewer back to the non-teleological movement of the real, away from the story and the fictions created by the pseudo-Makhmalbāf, here the errant football creates almost a fairy tale. Like in fairy tale, the object seems enchanted and is afforded its own will. It descends and enters into a strange conversation with cats and the walls of this deserted village. The ball is not an excuse to show the village, but rather seems to be our host, showing us around the place where it lives, much like how in fairy tales we are at times introduced to otherworlds (or, as Cavell would have it, our world othered by our interest in it) by spirits or nonhuman creates. If not within fiction, the ball here brings us to the threshold of an experience.

Figure 8: Frame 6 from 24 Frames, directed by ‛Abbās Kiyārustamī, 2017.

Moving stills

In 24 Frames, Kiyārustamī again uses digital compositing and various forms of manipulation to bring to life a series of photographs he took over the years. The film is made of 24 stills, to which motion is added. There are no characters, dialogue, or narrative, at least in the usual senses of these terms. The card at the beginning of the film reads as follows: “For ‘24 Frames’ I started with famous paintings but then switched to photos I had taken through the years. I included about four and half minutes of what I imagined might have taken place before or after each image that I had captured.” The subjects are extremely simple, and—apart from the first frame, based on Bruegel’s painting Hunters in the Snow—they are taken from everyday moments. The film seems to constitute a sustained meditation on the making of images, and despite its origin in photography, the film is particularly relevant for our discussion. The subtle and slow movement, more perhaps than in any other film by Kiyārustamī, pushes the 24 four-and-half-minute vignettes into a unique dimension. One has the impression of finding oneself in front of a material, yet spiritual exercise, echoing Kiyārustamī’s words: “The calling of art is to extract us from our daily reality, to bring us to a hidden truth that’s difficult to access.”21Maya Jaggi, “A life in cinema: Abbas Kiarostami,” The Guardian, June 13, 2009, https://www.theguardian.com/film/2009/jun/13/abbas-kiarostami-film But he also adds, “I’ve often noticed that we are not able to look at what we have in front of us, unless it’s inside a frame.”22Andrew Pulver, “Interview: Abbas Kiarostami’s best shot,” The Guardian, July 29, 2009, https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2009/jul/29/photography-abbas-kiarostami-best-shot 24 Frames is both marked by the specificity of the places and times it offers to the audience’s attention (we see mostly daytime scenes, with a variety of meteorological conditions—rain and snow in particular—in very precise locations, along with recurring interiors, open windows, and seaside locales), and capable of using the specific material conditions of our shared world to cast an almost divinatory spell. Take Frame 6, for instance (and its companion piece, Frame 21). The composition is clearly organised between foreground, middle ground and background. The foreground is occupied by an open window, whilst in the middle ground, the wind agitates the leafy branches of a tree. In the background, clouds move quickly from the left to the right of the screen, in a movement that produces a natural choreography with the leaves. At some point, a crow walks into the shot (crows are a recurring feature in 24 Frames; they appear again in Frame 7, 12, 20, 21, and so do deer, seagulls, and cows) and then another. A plane, with its distinctive sound, crosses the screen from the bottom right to the top left. Before the sequence ends, the crows fly away, both at the same time. The scene is utterly mundane, and the movement is similar to many we have seen. The only element that confers dramatic intensity to the scene is the operatic music. And yet, the sequence, like many others in 24 Frames, is far from having the character of the documentary. The composition has the sobriety and simplicity of a landscape shot, with the camera seemingly left to record what is in front of it. There seems to be no other intention than to capture a moment of the world revealing itself to the camera. However, there is something hypnotic about the joint movement of the leaves and the clouds, something mysterious, but not in the sense of an impending danger or the pressure of occult forces. It is rather the surprising and endless attraction of the familiar, of a world becoming present to us. We see something similar in Frames 7 and 9 (and to a lesser extent in Frames 13 and 16), which deploy a similar framing composition, with a screening element in the foreground, respectively a metal balustrade in the first, a stone one in the second and the movement of the waves in the middle ground. Here again, we are pulled towards the image and kept in relation with it by a subtle and yet powerful attraction that comes from both recognizing what we see and acknowledging its aesthetic (and existential) significance, as if for the first time.

The factual as perceptual experience

As Bilge Ebiri writes, this film’s very conception is structured around “the conflict between control and expansiveness.”23Bilge Ebiri, “24 Frames: The World Made Visible,” The Criterion Collection, January 8, 2019,https://www.criterion.com/current/posts/6132-24-frames-the-world-made-visible It is precisely in this unresolved dialectic between letting the world show itself and channelling this presence that 24 Frames produces perhaps the best illustration of the “documentary object” in Kiyārustamī’s films. Here, the purely factual recording of a presence, transcends the confines of the documentary’s search for objectivity or its grounding in analysis and argument. In this sense, Kiyārustamī’s documentary work connects his filmmaking to a different tradition and trajectory.

The principles of documentary filmmaking (at least a certain understanding of it) presuppose a sober detachment from the object under scrutiny, so that this can be properly observed and placed in the appropriate context. This tradition of documentary film is one that anchors its formal solutions to the development of an argument or thesis. The object becomes the basis for a truth claim or the cornerstone of an argument (consider, for instance, how in true crime films, objects anchor the filmic narration to an extra-filmic, juridical truth). However, film historian Scott MacDonald reminds us that the documented object can also play a different role. MacDonald traces an alternative history of the factual mode (which he calls the “avant-doc”) and writes

the camera’s ability to document the world has generally been understood as an obvious and mundane dimension of cinema— something virtually automatic, barely worthy of our attention […] in a wide range of instances, inventive, often courageous, filmmakers have turned the camera’s facility with documenting reality into something remarkable, amazing, awe inspiring, sometimes almost too beautiful, sometimes terrifying, often powerfully educational.24Scott MacDonald, The Sublimity of Document: Cinema as Diorama (OUP, 2019), 14.

This seems to be exactly what Kiyārustamī is aiming for with films such as Five, Take Me Home and 24 Frames. These are works of documentary, but in which no argument takes place; therefore, they depart significantly from the way documentaries have been theorised by the likes of Bill Nichols and Michael Renov. To this effect, MacDonald writes that precisely the lack of thesis or argumentation “allows filmmakers to believe that carefully representing the way certain places, animals, people, and activities look (and sound) might be of value for a wide range of spectators, regardless of particular attitudes or political beliefs.”25Scott MacDonald, The Sublimity of Document: Cinema as Diorama (OUP, 2019), 11.

The fascination that ‘documentary objects’ evidently hold for the director is dependent on their ability to exercise a certain endlessly attractive independence. Here, the object plays a completely different role from the one it plays in much documentary cinema: it is not the object observed in order to be analysed, dissected, manipulated, and put to use. Here, it is the object liberated, presencing as an address that re-enchants the world, producing a leap beyond the factual register, connecting with the idea of cinema as a spiritual exercise.

Figure 9: Frame 8 from 24 Frames, directed by ‛Abbās Kiyārustamī, 2017.

Conclusions

The analyses of ‘documentary objects’ in the context of Kiyārustamī’s narrative and factual films offered here aimed to show how Kiyārustamī moves constantly between two registers: objects disrupt stories and the narrative momentum, but also the factual register of analysis and pure observation. In this, Kiyārustamī seems to be acutely aware of the earliest film experimentations. As Comolli writes, “… in the first Lumière films, it was already the force of things that captured cinematic representation; this force was equal to that of the form of representation that claimed to capture those things; it was this force of things as they assert themselves. For people were wonderstruck by the trembling of leaves on the trees.”26Jean-Louis Comolli, “Documentary Journey to the Land of the Head Shrinkers,” trans. Annette Michelson, October 90 (1999): 36-49, https://doi.org/10.2307/779079. Stern captures something similar, which also seems true of Kiyārustamī, when he invokes cinema’s unique ability “to register a world as if caught ‘off-guard, unposed.’”27Lesley Stern, “Paths That Wind Through the Thicket of Things,” Critical Inquiry 28, no. 1 (2001): 339. In her work on Chantal Akerman, Margulies writes that in Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman, objects have a certain animism—a material order’s seeming resistance to being tamed that produces an intrusion into the rigidity of form and points to the world’s disruptive autonomy.28Ivone Margulies, Nothing Happens: Chantal Akerman’s Hyperrealist Everyday (Duke University Press, 1996), 89. The cinema is particularly apt at registering and even channelling this autonomy precisely because cinema’s “capacity to render the phenomenal world (or to enact, as Kracauer put it, ‘the process of materialization’…) is equalled only by film’s capacity to also unhinge the solidity and certainty of things.”29Lesley Stern, “Paths That Wind Through the Thicket of Things,” Critical Inquiry 28, no. 1 (2001): 334.

By ‘unhinging’ we can read the ability of film to at once record our material world (with all the limitations that this involves, starting with the necessity to always only frame a certain portion of it at a given time and thus be limited in the amount of control we have over it), whilst at the same time transcend these limitations by connecting us with the idea of the world’s presence to us, of its becoming visible and audible to us despite our absence from the scene. What I have called Kiyārustamī’s documentary objects—far from simply adding documentary value to a narrative film or presenting a factual argument on the world—reignite our interest in the world and bring us into a renewed and mature (in the sense of not primal and innocent) intimacy with this world here. If Epstein could write that “if we wish to understand how an animal, a plant or a stone can inspire respect, fear and horror, those three most sacred sentiments, I think we must watch them on the screen, living their mysterious silent lives, alien to the human sensibility,”30Jean Epstein, “On Certain Characteristics of Photogénie,” trans. Tom Milne, in French Film Theory and Criticism: 1907-1939, vol. 1 (1907–1929), ed. Richard Abel (Princeton University Press, 1988), 317. this is because the cinema has the capacity to express to us something that we might otherwise be unable to see or at least to acknowledge (to see more than in passing). Jean-Luc Nancy, writing on Kiyārustamī, speaks of this as the interminable driving force of the world and also discusses cinema in terms of releasing the world as evidence that cannot be exhausted. It is worth here quoting the passage:

Before, after the film, there is life, to be sure. But life continues in the continuation of cinema, in the image and in its movement. It does not continue like an imaginary projection, as a substitute for a lack of life: on the contrary, the image is the continuation without which life would not live. The image, here, is not a copy, a reflection, or a projection. It does not participate in the secondary, weakened, doubtful and dangerous reality that a heavy tradition bestows on it. It is not even that by means of which life would continue: it is in a much deeper way (but this depth is the very surface of the image) this, that life continues with the image, that is, that it stands on its own beyond itself, going forward, ahead, ahead of itself as ahead of that which, at the same time, invincibly, continuously, and evidently calls and resists it.31Jean-Luc Nancy, The Evidence of Film: Abbas Kiarostami, trans. Christine Irizarry and Verena Andermatt Conley (Yves Gevaert Éditeur, 2001), 62.

Kiyārustamī’s documentary objects exemplify and give form to this operation: the camera opens our eyes, once again, onto the very world that we know and live in. It produces what one could even call a form of re-enchantment, but an adult version of it —a re-enchantment that is fully aware that there is also a non-poetic way of looking at the world, a disinterested way, but chooses interest instead (say poetry). One can call this a fully modern, materialist enchantment, fully aware that we lack a teleology, a happy ending and yet, or because of this, we continue to live in this world here.

Cite this article

This article offers a critical reexamination of ‛Abbās Kiyārustamī’s cinema through the lens of “documentary objects,” challenging conventional readings that focus primarily on his formal simplicity and documentary aesthetics. While Kiyārustamī’s work—spanning from Homework (1989) to 24 Frames (2017)—has often been situated at the intersection of fiction and documentary, this study argues that his strategic deployment of everyday objects not only disrupts narrative momentum but also transcends traditional dichotomies between fiction and factuality. Drawing on examples from key films such as Where Is the Friend’s Home?, Close-Up, Five, and Take Me Home, the article traces how objects such as notebooks, footballs, spray cans, and elements of the natural world move between narrative propulsion and perceptual meditation. Engaging with theories from early film studies, phenomenology, and contemporary philosophy, the analysis highlights how Kiyārustamī’s cinema stages a subtle interplay between the factual presence of objects and their capacity to re-enchant the ordinary. In doing so, Kiyārustamī’s “documentary objects” invite a reconsideration of the role of materiality in cinema, shifting the focus from storytelling toward an experiential and affective engagement with the world. The article situates Kiyārustamī within broader debates on the ontology of the cinematic image and proposes that his work constitutes a distinct contribution to the lineage of contemplative and perceptually-driven filmmaking.