Film Adaptations and Narrative Change in Persian Fiction

Imagine living in the 18th or 19th century, before the advent of cinema and the introduction of movies into our lives. What was it like to be a reader, or a writer? How were stories told, listened to, and written? Stories were created in the imagination of writers and for the most part told in a linear or chronological form. In other words, the events that were envisioned as occurring first were presented first, and they were followed in the same order by other events, more or less in chronological order. This order was also what the listener or reader expected. Of course there are exceptions.

With the advent of motion pictures, and once the potential for storytelling of this new medium was understood, filmmakers’ attention was largely focused on the work of fiction writers (and, of course, playwrights); many novels and short stories were adapted to films. In its early years, cinema was dependent on the printed word. Early Iranian filmmakers, perhaps emulating their Western counterparts, were no exception to this rule. ‛Abdalhusayn Sipantā’s pioneering efforts in Iranian cinema began in conversation with classical Persian literature in his film about Firdawsī, in which he uses segments of the Shāhnāmah (1934), followed by his adaptations of Nizāmī’s Shīrīn and Farhād (1934) and Laylī and Majnūn (1936).1For a history of Iranian cinema, see: Mohammad Ali Issari, Cinema in Iran, 1900-1979 (Metuchen and London: Scarecrow, 1989). Also see: Hamid Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema, vols. 1-4 (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2011-2012). Not only was the adaptation of literary works an inevitable practice but it was also deemed desirable and was advocated by critics. Even as late as 1949, the cinema correspondent of Kayhān newspaper stated that a “film must be the adaptation of a great book by a famous writer.”2Kayhān, no. 1503, 15 Farvardīn 1327 [3 April 1948], 2, cited in Shahnāz Murādī, Iqtibās-i Adabī dar Sīnimā-yi Īrān (Tehran: Intishārāt-i Āgāh, 1368/1989), 21-22. In the same vein, Parvīz Khatībī’s 1951 film, Parīchihr, was an adaptation of Muhammad Hijāzī’s popular 1929 novel by the same name.3For a brief discussion of the popularity of Hijāzī’s novel and similar works, see: Hasan ‛Abidīnī, Sad Sal Dāstānnivīsī dar Īrān, vol. 1, 2nd ed. (Tehran: Nashr-i Tandar, 1368/1989), 33-45. Also see: Hassan Kamshad, Modern Persian Prose Literature (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1966), 73-84.

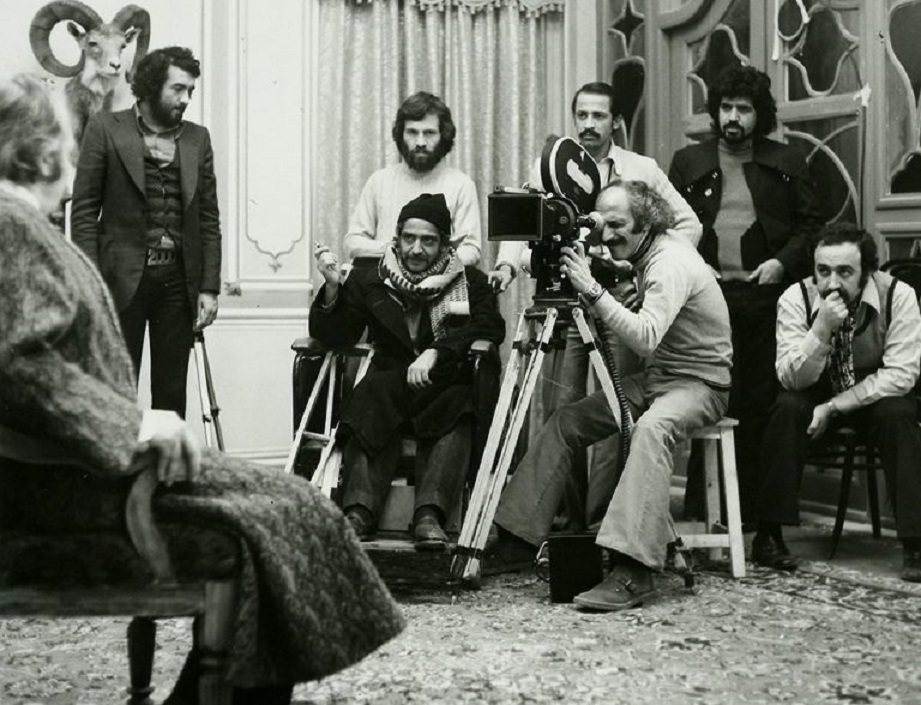

While a pioneer of Iranian cinema such as Sipantā could be described as a self- taught amateur filmmaker during the early decades of the 20th century, in the second half of that century, among an increasing number of filmmakers who were professionally trained and produced popular movies that appealed to general audiences, a smaller number of them started to look at cinema not merely as a commercial craft but as a distinct art form—albeit, similar to Persian literature at the time, an art form at the service of social and political criticism. A larger number of films continued to be made by talented directors, many of which were adaptations of literary works.4On the social and political aspects of modernist Persian literature, see: M. R. Ghanoonparvar, From Prophets of Doom to Chroniclers of Gloom (Costa Mesa, CA: Mazda Publishers, 2021), and Kamran Talattof, The Politics of Writing in Iran: A History of Modern Persian Literature (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2000). Among them, Dāvūd Mullāpūr’s 1968 adaptation of ‛Alī Muhammad Afghānī’s popular novel, Shawhar-i Āhū Khānum (Āhū Khānum’s Husband);5Shawhar-i Āhū Khānum, published in 1961, won a royal prize, which contributed to its popularity. The novel is discussed by M. A. Jamālzādah in Yadname-ye Jan Rypka (The Hague, Paris: Mouton, 1967), 178, and also by Ghanoonparvar in From Prophets of Doom to Chroniclers of Gloom (Mazda, 2021), 120-121 (see Note 5 above). Dāryūsh Mihrjū’ī’s 1969 film, Gāv (The Cow), based on Ghulāmhusayn Sā‛idī’s book, ‛Azādārān-i Biyal (The Mourners of Biyal, the film script of which was a collaboration between Sā‛idī and Mihrjū’ī), the first Iranian film to attract international attention;6For a translation of the screenplay of Sā’idī’s The Cow, see: The Cow: A Screenplay, translated by Mohsen Ghadessy, Iranian Studies 18 (1985):257-323. Mihrjū’ī’s Dāyirah-yi Mīnā (The Cycle), based on Sā‛idī’s short story, “Āshghāldūnī;”7“Āshghāldūnī” has been translated into English as “The Trash Heap” by Robert Campbell, Hasan Javadi, and Julie Scott Meisami in Dandil: Stories from Iranian Life (New York: Random House, 1981). For reviews of the film, see: Nāsir Zirā’atī, compiler, Majmū‛ah-yi Maqālāt dar Naqd va Mu‛arrifī-i Āsār-i Dāryūsh Mihrjū’ī (Tehran: Intishārāt-i Nāhīd, 1375/1996), 308-355. Nāsir Taqvā’ī’s 1970 adaptation of Sā‛idī’s story, Ārāmish dar Huzūr-i Dīgarān (Calm in the Presence of Others);8This story appears in: Ghulāmhusayn Sā‛idī, Vāhamah-hā-yi Bīnām va Nishān (Tehran: Intishārāt-i Nīl, 2535/1976), 137-236. Mas‛ūd Kīmiyā’ī’s film based on Sādiq Hidāyat’s well-known short story, “Dāsh Ākul,” in 1973;9The translation of “Dāsh Ākul” by Richard Arndt and Mansur Ekhtiar appears in Sadeq Hedayat: An Anthology (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1979), 41-52. For an enlightening discussion of the differences between Hidāyat’s short story and Kīmiyā’ī’s film, see: Hamid Naficy, “Iranian Writers, Iranian Cinema, and the Case of Dash Akol” in Iranian Studies 28, nos. 2-4 (Spring, Fall 1985):231-251. Amīr Nādirī’s 1973 Tangsīr, based on Sādiq Chūbak’s novel of the same title;10Tangsīr was translated by Marzieh Sami’i and F. R. C. Bagley as “One Man and His Gun” in F. R. C. Bagley, ed. Sadeq Chubak: An Anthology (Delmar, NY: Caravan Books, 1982), 13-181. For an interesting discussion of the novel, see: Muhammad Mahdī Khurramī, “Tangsīr, Bāzsāzī-i Ustūrahgūnah-yi Dāstānī Vāqi‛ī” in ‛Alī Dihbāshī, comp. Yād-i Sādiq Chūbak (Tehran: Nashr-e Sālis, 1380/2001), 127-136. Mas‛ūd Kīmiyā’ī’s 1973 Khak, based on Mahmūd Dawlatābādī’s Awsanah-yi Bābā Subhān (The Legend of Bābā Subhān);11See: Mahmūd Dawlatābādī, “Bābā Subhān dar Khāk,” in Zāvin Qūkāsiyān, Majmū‛ah-yi Maqālāt dar Naqd va Mu‛arrifī-i Āsār-i Mas‛ūd Kīmiyā’ī (Tehran: Intishārāt-i Āgāh, 1369/1980), 278-318. and Bahman Farmānārā’s 1974 adaptation of Hūshang Gulshīrī’s Shāzdah Ihtijāb (Prince Ihtijāb) and his 1978 film, Sāyah’hā-yi Buland-i Bād (The Long Shadows of the Wind), an adaptation of another story by Gulshīrī,12For a discussion of the adaptation of these two stories, see: Hamid Dabashi, Close Up: Iranian Cinema, Past, Present and Future (London, New York: Verso, 2001), 112-155. are a few examples.13Some of these adaptations have been discussed in Murādī’s Iqtibās-i Adabī dar Sīnimā-yi Īrān (see Note 3 above). To this partial list, three adaptations of the best internationally known modern Persian novel, Sādiq Hidāyat’s Būf-i Kūr (The Blind Owl), should also be added. These films are by Kiyūmars Dirambakhsh (1974), Buzurgmihr Rafī‛ā (1973), and Rizā ‛Abduh (1992).14The standard translation of Būf-i Kūr is D. P. Costello, trans., The Blind Owl (New York: Evergreen, 1969).

At first glance, this list indicates a continuation of the dependence of at least some of the notable filmmakers on the work of literary artists. But while this may be true, cinema’s dependence on literature is no longer one-sided. Rather, the relationship has become interdependent. Earlier filmmakers’ adaptations were often based on traditional narratives, which were by and large linear; the filmmakers would attempt to maintain this linear form, which was often challenging in this new medium, and usually failed to fully capture the entire story. The task of many later filmmakers mentioned in the above list, however, was different, since the literary works they adapted had themselves undergone certain inevitable changes as a result of the ever increasing influence of cinema. In other words, the adaptations early filmmakers made to literature began to shape fiction itself, which in turn changed cinematic adaptations.

Modern Persian fiction has often been described as experimental in form and presentation;15See, for instance, “Experimentation in Kind and the Function of Form” in M. R. Ghanoonparvar, From Prophets of Doom to Chroniclers of Gloom (Costa Mesa, CA: Mazda Publishers, 2021), 82-101. this innovation, I argue, is in fact experimentation in narrative devices, structure, and strategies, which subsequently brought about changes in fiction and storytelling.16Although numerous studies in the West have addressed the issue of the changes that have occurred in fictional narrative as a result of the influence of cinema, including Robert Richardson’s Literature and Film (Bloomington, IN: University of Indiana Press, 1969) and Seymour Chatman’s Story and Discourse: Narrative Structure in Fiction and Film (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1978), little attention has been paid to such changes in Persian fictional narrative strategies. Contrasting late 20th-century Persian fiction with the works of earlier writers such as Muhammad ‛Alī Jamālzādah, Sādiq Hidāyat, Buzurg ‛Alavī, and Mahmūd Bihāzīn, among others, well-known writer and critic Jamāl Mīrsādiqī argues that recent novels and short stories have become more tasvīrī, or pictorial.17Speech at The University of Texas at Austin, 1992. Also see: Jamāl Mīrsādiqī’s ‛Anāsur-i Dāstān (Tehran: Intishārāt-i Shafā, 1364/1985), 273-274, and Adabiyyāt-i Dāstānī: Qissah, Dāstān-i Kūtāh, Rumān, 2nd ed. (Tehran: Mu‛assisah-yi Farhangī-i Māhūr, 1365/1986), 301-304. In other words, in contrast to the often character-based or event-based earlier stories—which mostly “tell” about the characters’ personality traits, such as most of Jamālzādah’s work, or the internal workings of a character’s mind, such as a number of Hidāyat’s stories, including The Blind Owl—more recent novelists and short story writers attempt to “show” the characters through their behavior and actions. Indeed, if we consider the major difference between the written form and the visual form of stories, that is, fiction and cinema, it is clear that traditionally fiction writers had to generally rely on “telling” their stories whereas filmmakers inevitably have to “show” their stories. Early filmmakers’ attempts at adapting novels and short stories were impeded by trying to follow the written narrative techniques that were used for “telling” a story. Filmmakers are generally more successful in the reproduction of scenes and events in their adaptations of written stories than in the less visual aspects of a written narrative, such as a character’s thought processes.18Although this is true from the perspective of the filmmaker, as Seymour Chapman demonstrates in his article “What Novels Can Do that Films Can’t (and Vice Versa)” in Leo Braudy and Marshall Cohan, eds., Film Theory and Criticism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999), 435-451, the viewer is generally unable to take notice of all the visual details of a scene. In his words, “Film narrative possesses a plenitude of visual details, an excessive particularity compared to the verbal version, a plenitude aptly called by certain aestheticians visual ‘over-specification’ (űberbestimmtheit), a property that it shares, of course, with other visual arts. But unlike those arts, unlike painting or sculpture, narrative films do not usually allow us time to dwell on plenteous details. Pressure from the narrative component is too great. Events move too fast” (438-439). As this paper will explore, this technique begins to become evident in the latter part of the 1960s.

Mīrsādiqī’s observation that recent Persian fiction has become pictorial or visual merely touches the surface of the changes that have occurred in fiction writing. Modern fiction writers, of course, continue to draw on traditional, narrative models, genres, and subject matter, but for many authors today, movies and other forms of visual storytelling are just as influential as written work. Moreover, the books they may read are often written by other contemporary authors who are influenced by film and television, thereby perpetuating the narrative techniques borrowed from audio-visual media. Many modern authors make use of, consciously or subconsciously, such cinematic practices as shots, cutting, lighting, depth of picture, and so forth in their descriptive narratives of scenes. Nāsir Taqvā’ī, for instance, begins his short story, “Āqā Jūlū,” with the following visual narrative:19The short story appears first in the journal Ārash, 2:1 (Tīr 1343/June-July 1964): 84-94.

The sea, which is neither blue nor green, has pushed the town back, halfway up the mountains. At high tide the waves’ white froth sinks in the sand at the threshold of the first houses. The waves beat against the dykes between the stone wall that circles the low land and the dock. Behind the wall built along the dock are a few shops and a shellfish cleaning factory, and the shade cast by the wall is the porters’ hangout.20All translations from this story are from Minoo Southgate, ed., trans. Modern Persian Short Stories (Washington, DC: Three Continents Press, 1980), 89-103. This quote, 89.

The opening paragraph of the story begins with a panoramic view, or a long shot, showing the sea, the town, and the mountains. The point of view is that of a camera that is located some distance from the shore in the sea, capturing the waves, the sand, the houses, and the dykes. In the next paragraph, the camera moves to a different spot, as we see:

Dark, patternless brown mountains hump behind the town, curl around the bare sandy hill, and disappear into the sea, except for a few scattered rocks jutting out of the water here and there. The beacon blinks a bit farther away in the sea. At night, the moon shines into the rooms through open windows. On the water, the beacon fuses its red beams with the moonlight each time it flashes.21Minoo Southgate, ed., trans. Modern Persian Short Stories (Washington, DC: Three Continents Press, 1980), 89.

The next picture is of the same view, but this time just before sunrise:

At dawn, when the moon grows pale on the mountains, the long distant line between the sea and the sky casts a white gleam. You can hear the fishermen’s voices and the sound of their oars as their boats approach the horizon, black against the silvery glitter of the water.22Minoo Southgate, ed., trans. Modern Persian Short Stories (Washington, DC: Three Continents Press, 1980), 89.

The camera turns toward the town; but now it is just before sunset:

When the white line in the horizon turns yellow and the sun reaches the high ventilation towers of the houses and the dome-like covers of the tanks, the fishermen return. The sun looks from above.23Minoo Southgate, ed., trans. Modern Persian Short Stories (Washington, DC: Three Continents Press, 1980), 89.

The camera this time begins to zoom in, and we see a closer shot of the beach and the inhabitants of the town:

On the sandy beach, old men shade their eyes from the sun, watching the boats anxiously. Once fishermen, they now weave fishing nets and wait for the boats, hoping to make a few pennies by repairing the nets torn by sharks. The women wear loose gowns with embroidered skirts. They watch the boats through the two holes of their black veils, anxious to get the fish in time for their husbands’ meals. Naked children stand beside a mound of colorful loincloths, ready to jump into the water when the boats get nearer. Farther away, the porters sit in the shade, leaning against the wall, waiting for a boat—or a ship, if it has been a few months since the last one’s arrival.24Minoo Southgate, ed., trans. Modern Persian Short Stories (Washington, DC: Three Continents Press, 1980), 89-90.

In the last paragraph of the opening section of the story, the camera is located somewhere inside the town, showing us medium and close shots of various structures and scenes, ending with a shot of a broken window:

From the tops of the ventilation towers, the sun penetrates the rooms through the colored glass windows, painting rainbows on the plaster walls. The large house facing the children’s playground never catches the sun in its windows. The townspeople have broken the glass with stones.25Minoo Southgate, ed., trans. Modern Persian Short Stories (Washington, DC: Three Continents Press, 1980), 90.

What is linguistically noteworthy in this opening segment of “Āqā Jūlū” is that, while the rest of the story is narrated in the past tense, in this segment, Taqvā’ī has chosen the present tense to describe the scene, in other words, employing the here-and-now effect of the cinema experience. Nāsir Taqvā’ī of course eventually became a filmmaker, and this penchant for the cinema certainly influenced his writing. This type of cinematic description can be seen, however, in the works of many 20th- and 21st-century Iranian authors, including Sādiq Chūbak and Mahmūd Dawlatābādī, and in more recent works by Ghazālah ‛Alīzādah and Munīrū Ravānīpūr, among others.

In addition to the visual or pictorial impact, another perhaps even more important influence of the audio-visual media in general and cinema in particular on the work of modern fiction writers is the non-linear and fragmented mode of presentation, which has become a distinguishing feature of modern fiction. Fragmented, non-linear stories often cause tremendous confusion and frustration for casual readers, those who generally read as a pastime, and often results in the book being tossed aside and accusations being made against the writer for having produced an incoherent work. I have even observed such reactions among my students when they first read Hūshang Gulshīrī’s Prince Ihtijāb (discussed below) before watching its film adaptation. Many such readers, by way of contrast, have no problem following and understanding the same kind of non-linear and fragmented sequences of events when watching a film; they have learned how to follow cinematic narrative structures and techniques, such as flashbacks, while written fiction that uses the same techniques appears enigmatic and confusing. This type of modern fiction is what Roland Barthes calls “writerly” as opposed to “readerly” texts. While “readerly” texts essentially are the production of storytellers and are generally entertaining and serve to fill the leisure time of the reader, “writerly” texts require partnership and participation by the reader in the process of the production of meaning.26Roland Barthes, S/Z, transl. by Richard Miller (New York: Hill and Wang, 1974). This participation partly involves decoding, as it were, the fragmented non-linear narrative, a process during which the reader’s interpretation contributes to enhancement of the story semantically and adds to the multiple layers of meaning. One such example that demonstrates the influence of cinema on fiction and contributes to a revision of narrative strategies is Hūshang Gulshīrī’s Shāzdah Ihtijāb.27Hūshang Gulshīrī, Shāzdah Ihtijāb, 7th ed. (Tehran: Intishārāt-i Quqnūs, 1357/1978). This novel was first published in 1969.

This short novel is puzzling to many readers because of its recurrent flashbacks, constant change of scenes, and frequent point-of-view shifts—all techniques borrowed from cinema—which produce a fragmented narrative. These elements are employed by Golshiri from the first pages of the novel. The novel begins with a third-person narrative, mostly in the past tense, describing Prince Ihtijāb sitting in his comfortable armchair, suffering from fever and coughing, and rejecting any assistance from his wife and maid. The second paragraph describes the Prince’s recollection of earlier that evening, when he meets Murād in his wheelchair pushed by his wife, Hasanī, and asking for money, which the Prince gives him. Then the Prince arrives home, kisses his wife Fakhr al-Nisā’ and goes upstairs to sit in his chair in the dark in the same room we find him in the opening scene. In the same paragraph, we find the maid, Fakhrī, in the kitchen; then, worried about the Prince, she goes upstairs, but is scared off by the Prince thumping the floor with his feet. She goes back to her room, and sits in front of the mirror listening for an order from her master:

“Fakhrī!”

In order for Fakhrī to get up, toss on her headscarf, tie her apron on, and set the table. When the Prince would wash his hands, dry them, and shout:

“Fakhr al-Nisā’!”

She would put the headscarf in the pocket of Fakhrī’s apron, change her dress, sit down before the mirror, put on some makeup in a hurry, comb her hair, go to the dining room and sit across from the Prince, have her dinner, and once the Prince went upstairs, Fakhrī would clear the table and wash the dishes, and Fakhr al-Nisā’ would put on her makeup and go to the bedroom until the Prince would show up sometime in the middle of the night and whisper:

“Are you asleep, Fakhr al-Nisā’?”28Hūshang Gulshīrī, Shāzdah Ihtijāb, 7th ed. (Tehran: Intishārāt-i Quqnūs, 1357/1978), 6. Although two English translations of this novel are available, in order for the rendition to adequately reflect my argument, I have retranslated all the quoted passages from the original novel.

Are Fakhrī and Fakhr al-Nisā’—the maid and the wife—the same person, the reader wonders? Is there a fusion of two characters? If so, which one is real and which one imaginary? Readers will later learn of the death of Fakhr al-Nisā’ sometime in the past, and also that the Prince has forced the maid to assume a double identity, to fulfill his aspirations of not only flirting with the maid, but also his desire to dominate a pretend duplicate of his wife, who was intellectually superior to him.

The following paragraph describes a large room in which the Prince has been sitting, now almost empty because he has sold nearly all his antiques to pay his gambling debts. He is tormented by the scolding gazes of parents, grandparents, and Fakhr al-Nisā’ (we assume, from their photographs), as well as his own sense of inferiority. The third-person narrator continues:

A musty smell had filled the room. The carpet was under his feet. The Prince’s entire body only filled a corner of that ancestral chair. And the Prince felt the gravity and weight of the chair beneath his body. The chirping of the crickets was an endless thread, an entangled skein that extended to the entire expanse of the night.

Perhaps they were in the weeds in the flower garden, or… I said, “Fakhrī, close these curtains tightly. I don’t want to see any of those damn streetlights.” Fakhrī said, “Dear Prince, won’t you at least give me permission to open the window to let in some fresh air?”

And the Prince shouted:

“You shut up! Just do what I told you to do.”29Hūshang Gulshīrī, Shāzdah Ihtijāb, 7th ed. (Tehran: Intishārāt-i Quqnūs, 1357/1978), 7.

Whereas in the first paragraph of this segment we still have a third-person narrator, after the first sentence of the second paragraph there is a sudden shift to a first-person narrator, obviously the Prince, who reports on what he told Fakhrī and Fakhrī’s response (both placed in quotation marks). The narrative then shifts back and the third-person narrator reporting on the Prince shouting at Fakhri and provides a description of her appearance.

While readers of Gulshīrī’s Shāzdah Ihtijāb may find the novel confusing, Bahman Farmānārā’s film is a suitable medium to help decipher the written story for such readers, even though the narrative of the film sometimes deviates from that of the novel. Although the film stands on its own artistic merits, Gulshīrī’s collaboration with Farmānārā in writing the script can be considered a way of clarifying the complex hybrid literary text and a sort of explanatory addendum. Various deceased ancestors and relatives of the Prince populate the novel and, as if their ghosts have been summoned from their photographs, they appear before the Prince, as an example of a cinematic device which Golshiri uses effectively in his novel. The use of this device is much more effective, however, in its natural environment of Farmānārā’s film.30The use of film adaptation of literary works, of course, cannot be extended to other adaptations of Persian literature for cinema or even Ibrāhīm Gulistān’s “novelization” of his film, Āsrār-i Ganj-e Darrah-yi Jinnī [The Secrets of the Treasures of the Haunted Valley] (1971), interestingly the only Iranian film which was made before the publication of the printed work, in this case, Gulistān’s novel by the same name, and which is a true fusion of both media. For an examination of this story, see: Paul Sprachman, “Ebrahim Golestan’s The Treasure: A Parable of Cliché and Consumption,” Iranian Studies 15, nos. 1-4 (1985):155-180.

The inevitable use of cinematic techniques in modern fiction writing has become predominant in the work of Iranian novelists and short story writers. Some of these devices, such as flashbacks and shifts in point of view, have certainly helped writers enhancing their storytelling. At the same time, however, the use of some of these techniques has limited the potential reach of their readership, and has also displeased traditional literary critics.31For the reception of such stories, see: Ghanoonparvar, “Literary Ambiguity” in From Prophets of Doom to Chroniclers of Gloom, 118-140 (see Note 5 above). Many critics, for instance, consider point of view as an important tool that an author uses to immerse readers in a work of fiction. By focusing only on the protagonist’s viewpoint, the writer creates an experience in which readers can submit to the illusion that they are not merely reading but are involved in the story. Shifting point of view in the middle of the narrative, such critics argue, breaks this illusion and the readers’ trust in the author and their work. Perhaps one important reason for and an appealing aspect of writers’ attempts to emulate cinematic narrative technique is that in film, except when voiceovers are employed, it is often difficult if not impossible for the viewers to learn what the protagonist is thinking or feeling. After all, cinema is a better medium for shifting point of view and switching, sometimes within seconds, between various scenes. These cinematic techniques, as mentioned earlier, are familiar and therefore create suspense and appeal for movie audiences, whereas they can be disrupting and annoying to readers of written fiction.

The interrelationship of cinema and fiction has been ongoing for over a century, and will surely continue. The early cinematic adaptations of literary works resulted in many failures, such as Sipantā’s Firdawsī, and few minor successes, such as his Shīrīn and Farhād.32According to Hamid Reza Sadr, when Firdawsī was screened commercially, “it ran for a mere three nights and was a total flop.” See: Hamid Reza Sadr, Iranian Cinema: A Political History (London and New York: I.B. Tauris, 2006), 34. Even direct collaborations between fiction writers and filmmakers faced challenges. While cinema has gradually claimed more independence from the written word, it has established itself as an audio-visual medium that tells stories through sound and pictures. With cinema’s influence on the older medium of writing, the tools of which are essentially silent words printed on paper, despite its contributions, it has also taken away some of the possibilities of fiction writing and deprived both the writers and readers of the power of imagination, to some extent. It is becoming more and more difficult to read or write a story without picturing some well-known movie actor as the protagonist. The question remains: Will fiction writers in the future be able to claim some independence from cinema, as filmmakers have tried to do by distancing themselves from written fiction in the past? If we remember that the aesthetic enhancement of literary texts has traditionally been accomplished through the linguistic features and literary devices employed by writers, we can have some assurance that, despite the impact of cinema and audio-visual arts in general on all of our imaginations, many writers will still prefer to use the power of language to “tell” their stories.