Poetic Minimalism of Iranian Cinema: Pre-Revolution to New Wave

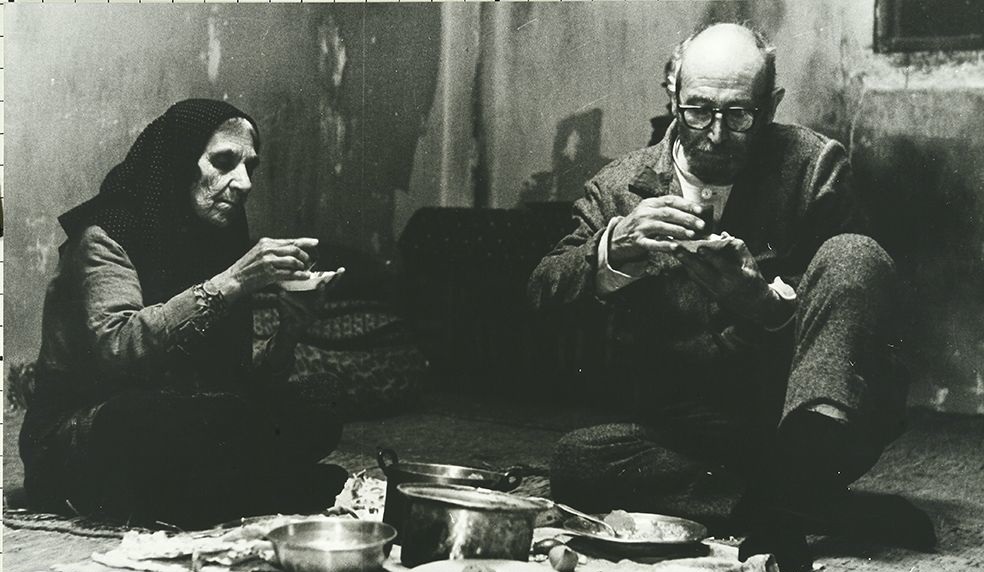

Introduction

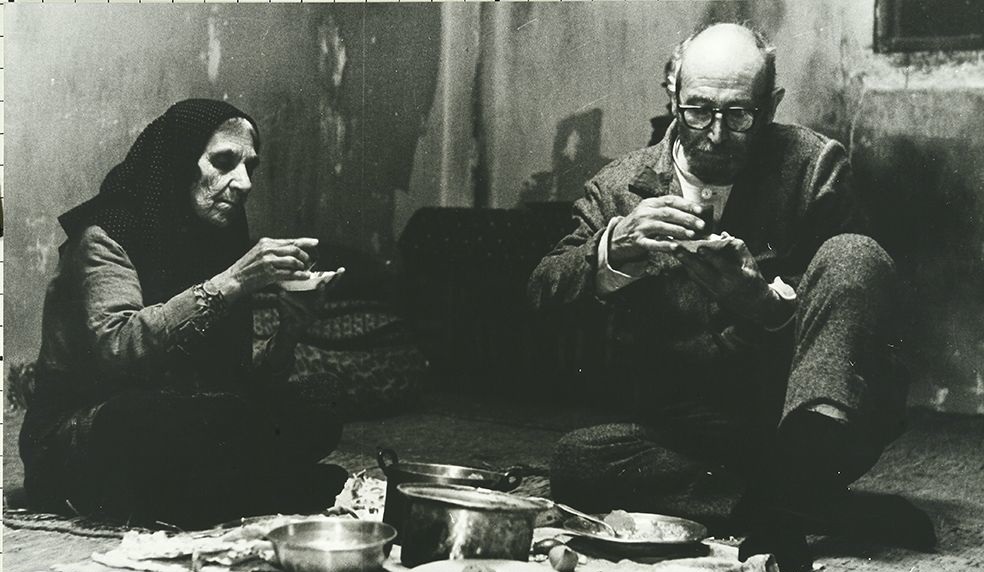

Figure 1: A still from the film The Cow (Gāv), directed by Dāryūsh Mihrjū’ī, 1968.

The capacity of Iranian cinema to combine aesthetic minimalism with deep socio-political and philosophical depth has earned it a unique and esteemed position on the international scene. Iranian filmmakers have created a distinctive narrative style that mostly depends on subtlety, lyrical realism, and an immersive depiction of daily life, in contrast to Western mainstream cinematic traditions that frequently place a higher priority on spectacle or linear storytelling. This method is distinguished by its deliberate simplicity, which communicates closeness and authenticity. It frequently uses amateur actors, has little conversation, and uses ordinary surroundings. However, Iranian films often function as multi-layered critiques of social issues, existential quandaries, and cultural identities, revealing a profound social richness underlying this aesthetic simplicity.

In general, Iranian cinema is notable for its inventive use of poetic minimalism, a style that combines metaphor with realism to offer an allegorical viewpoint on contemporary situations. Within the limitations of story and censorship, this technique enables filmmakers to investigate philosophical issues of life, identity, and morality. Many Iranian films use symbolism and allegory in place of direct confrontation, drawing viewers in and revealing the richness of meaning hidden beyond the surface of seemingly straightforward imagery. Directors such as ‛Abbās Kiyārustamī, Suhrāb Shahīd-Sālis, Furūgh Farrukhzād, Muhammadrizā Aslānī, Dāryūsh Mihrjū’ī, Nāsir Taqvā’ī, Ja‛far Panāhī, Asghar Farhādī, Rakhshān Banī-I‛timād, and Muhsin Makhmalbāf have used metaphors to create films that quietly touch the intricacies of Iranian society while encouraging viewers to consider common human experiences. Iranian cinema has gained a distinct character and a devoted following in the global film industry thanks to this combination of depth and simplicity.

From its pre-revolutionary origins in the 1960s and 1970s to its changes after the Islamic Revolution of 1979, this article explores the history of Iranian film. I will examine how filmmakers overcame societal constraints and constrictive political environments to produce a picture that is both local in its concerns and universal in its resonance by following the development of aesthetic minimalism and socio-political depth.

The Early Years of Pre-Revolutionary Filmmaking

Early Iranian mainstream film, before the Islamic Revolution of 1979, was heavily influenced by a complex interplay of social pressures, political constraints, and Western influences. The Iranian film industry started to expand in the 1930s, but it wasn’t until the 1960s that Iranian cinema began to take on a distinct voice. The prevailing trend of commercial and escapist movies defined the era preceding the Revolution. The government’s aim for cultural “modernization,” which frequently involved supporting Western-style films that prioritized amusement over politics, and consumer demand, both contributed to this tendency. Films that mirrored the Western cinematic style, especially in terms of narrative and visual presentation, became increasingly popular in the 1960s and early 1970s. In order to appeal to a broad audience rather than provoking critical thought, several films adopted melodramatic stories, extravagant set designs, and commercial themes that were influenced by American and Indian cinema. These films, which were a kind of escape that let viewers temporarily forget the sociopolitical difficulties they encountered in real life, frequently focused on romance, adventure, and light comedic themes. The tastes of a government that saw films as a means of amusement and social harmony rather than as a platform for philosophical investigation or social critique were also reflected in this trend towards commercialism.

Notwithstanding these limitations, a few filmmakers such as Mihrjū’ī, Ghaffārī, Gulistān, Rahnamā, Sālis, Farrukhzād, Kiyārustamī, started to explore novel formats and subjects, challenging the function of film in Iranian culture. By exploring more intricate stories that mirrored the realities of Iranian life, these directors aimed to depart from the prevailing commercial approach. Thus, even if the mainstream business mostly continued to concentrate on trivial amusement, the first seeds of a socially conscious film were planted. A few trailblazing filmmakers started introducing Iranian viewers to a new kind of filmmaking in this setting, which would later serve as the foundation for a more reflective cinema. The wider socio-political changes in Iranian society were in line with this new cinematic movement. Iran saw substantial economic growth and pronounced social inequality throughout the 1960s as a result of the Shah’s economic policies and fast modernization. Despite urgent problems, poverty, class inequality, and gender inequality were rarely discussed in public because of political persecution and censorship. However, several filmmakers used their skills to quietly address these concerns, employing symbolism and metaphor to avoid censorship.1Hamid Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema, Volume 1: The Artisanal Era, 1897–1941 (Durham: Duke University Press, 2011), 37.

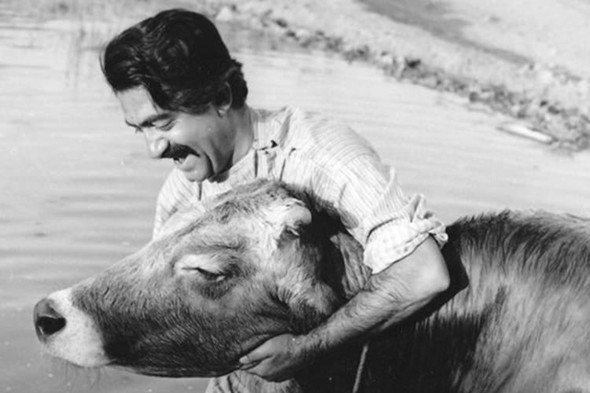

Figure 2: A still from the film The Cow (Gāv), directed by Dāryūsh Mihrjū’ī, 1968.

The Cow (Gāv, 1969), which was directed by Dāryūsh Mihrjū’ī, is a landmark film that perfectly captures this change. The Cow broke with the escapist films of its day, and is widely considered the beginning of the Iranian New Wave of cinema. Hasan, a poor peasant who owns the lone cow in his community, is the protagonist of the movie. The emotional and psychological reliance of the rural poor on their meagre resources is reflected in Hasan’s affection for the cow, which he loves like a child. Hasan’s identity and mental health start to fall apart once the cow dies, sending him into a depressed state that results in a tragic metamorphosis. The Cow stands out for its unique combination of symbolism and realism, which enables it to serve as a social critique as well as a psychological drama. The movie portrays a profoundly human tale of identity and loss on one level. On a deeper level, it offers a potent indictment of the poverty and class inequality that characterized Iranian rural life—problems that were frequently ignored in the government’s official narratives of modernization and growth. Mihrjū’ī avoids censorship by criticizing the Shah’s regime’s economic policies using the metaphor of the cow, which stands for economic dependency, without directly expressing political opinions. As a result, The Cow is not just a seminal film in Iranian cinema, but also a groundbreaking example of a film that uses symbolism and allegory to tackle socio-political concerns in a constrained Political climate. The Cow’s popularity encouraged other filmmakers to explore related subjects, including the cultural limitations experienced by women, the alienation of metropolitan life, and the hardships of the lower classes. For Iranian filmmakers, this new wave of socially conscious filmmaking paved the way by emphasizing socio-political critique, realism, and humanity over the previous commercial formulas. These films concentrated on the lives of common Iranians and their hardships, tapping into the communal consciousness of a population caught between tradition and modernization.

This pre-revolutionary era established the foundation for what would later be referred to as “poetic minimalism” in Iranian cinema. The distinctive form of poetic minimalism, which originated in Iranian cinema, combines realism with allegorical storytelling. Iranian poetic cinema is distinguished by a softer, more reflective style that blends the natural beauty of the Iranian environment with intensely personal, human tales, in contrast to the hard-edged realism present in some Western films. Using characters who are regular individuals in exceptional situations, this approach enables filmmakers to examine existential and philosophical concerns through the prism of daily life. Films that employ poetic minimalism rely on long takes and silences as strategies to fully immerse the audience in the film’s universe. The early work of filmmakers such as Furūgh Farrukhzād, whose 1962 documentary The House is Black (Khānah siyāh ast) is regarded as one of the first instances of Iranian poetic minimalism, demonstrates this aesthetic. The House is Black is a documentary, but it does more than just capture a situation; it paints a vivid, poetic picture of life in a leper colony. The film uses the reality of illness and loneliness as a metaphor for more general existential topics, presenting a brutal yet compassionate portrayal of suffering and resiliency through its poetic narration and striking cinematography.

Figure 3: A still from the film The House is Black (Khānah siyāh ast), directed by Furūgh Farrukhzād, 1962.

The 1974 work Still Life (Tabī‛at-i Bījān) by Suhrāb Shahīd-Sālis is another illustration of poetic minimalism prior to the Islamic Revolution.is an elderly railway worker whose lonely and mundane life turns into a meditation on life, ageing, and the silent dignity of human labor. Silence becomes an expressive instrument that shows the character’s inner life and, symbolically, the existential loneliness inherent in the human condition because of the slow, reflective tempo and lack of language, which foster a sense of silent introspection. By using silence to highlight the character’s unsaid struggle, Sālis encourages viewers to consider more general social and philosophical issues. The work of Sālis and her peers contributed to the development of a cinematic language that would subsequently be improved and expanded by filmmakers like Muhsen Makhmalbāf and ‛Abbās Kiyārustamī. These directors created visually minimalist films that were rich in metaphorical substance by adhering to the ideals of poetic minimalism. By giving New Wave filmmakers the aesthetic and philosophical means to examine the human condition in the face of political repression and cultural change, the pre-revolutionary filmmakers established the groundwork for a cinematic movement that would flourish in the post-revolutionary era. Iranian cinema had already started to establish itself as an art form of reflection, metaphor, and resiliency by the time of the Revolution; this would prove to be a vital basis in the years that followed.

Figure 4: A still from the film Still Life (Tabī‛at-i Bījān), directed by Suhrāb Shahīd-Sālis, 1974.

Post-Revolutionary New Wave Film, Artistic Restrictions, and Censorship

An important turning point in Iranian history, the Islamic Revolution of 1979, drastically altered the country’s sociopolitical environment and, consequently, its creative and artistic output. Iranian film was now subject to intricate new regulations. Wide-ranging changes in a variety of cultural domains resulted from the Revolution’s attempt to restructure Iranian society in line with Islamic precepts. The new administration put stringent rules on filmmakers that limited their ability to depict some issues, especially those that were considered too Western or un-Islamic, such as overt social or political criticism, sexual depictions, and romantic renderings. Women’s representation became especially delicate; new censorship regulations that dictated women’s behavior, dress, and interactions on screen required a level of conservatism that fundamentally changed the way films were made. Iranian filmmakers needed to be creative and resourceful in order to adjust to these developments. They were forced by the censorship regulations to develop a style of filmmaking that used metaphor, symbolism, and allegory to subtly express meaning. Since it was now illegal to criticize the state directly, filmmakers used poetic and complex visual language to subtly address socio-political themes. In addition to being a survival tactic, this adaptation marked a sea change in Iranian filmmaking. The use of metaphor and allegory became crucial for filmmakers who wanted to tackle difficult subjects without drawing attention to themselves. Changing their emphasis from the obviously political to the existential and philosophical was one way in which directors accomplished this. By making this change, they were able to construct stories that subtly alluded to socio-political themes while addressing larger human experiences and moral quandaries. As a result, there were a lot of subtexts in the film, with stories centered upon moral dilemmas and everyday hardships. In methods that seemed apolitical or universal, filmmakers frequently portrayed humans battling personal struggles that mirrored more general societal problems like poverty, gender inequity, and repression. The films of ‛Abbās Kiyārustamī provide an illustration of this adaptive storytelling. Kiyārustamī, who is renowned for his minimalist style, explored issues like personal responsibility, bereavement, and the pursuit of meaning through open-ended storylines, natural landscapes, and scant speech. A young boy’s attempt to return his friend’s notebook in Where is the Friend’s House? (Khānah-yi dūst kujāst? 1987) is a straightforward tale that delicately explores themes of loyalty, social duty, and ethical obligation. Kiyārustamī was able to create art while adhering to post-revolutionary censorship because of his emphasis on such universal topics.

Figure 5: A still from the film Where Is the Friend’s House? (Khānah-yi dūst kujāst?), directed by ‛Abbās Kiyārustamī, 1987.

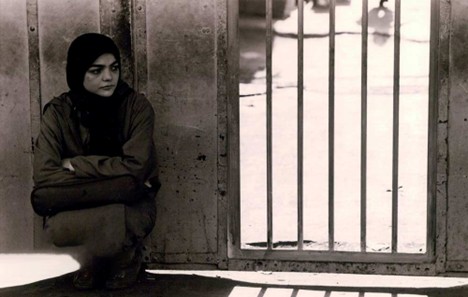

The measured approach taken by filmmakers to represent women was another crucial element of the new wave era. Due to limitations on the representation of women, filmmakers started creating female characters whose fortitude and tenacity were expressed through nuanced facial expressions and gestures. In post-revolutionary Iranian cinema, female heroines frequently exhibited silent resistance, perseverance, and moral integrity in place of overt conflicts with patriarchal structures. Rakhshān Banī-I‛timād’s 1995 film The Blue-Veiled (Rūsarī Ābī) for example, examines women’s lived experiences inside constrictive social structures, emphasizing their emotional and psychological landscapes in lieu of overt acts of rebellion. With this strategy, filmmakers were able to discuss women’s difficulties without openly questioning social standards.

Figure 6: A still from the film The Blue-Veiled (Rūsarī Ābī), directed by Rakhshān Banī-I‛timād’s, 1995.

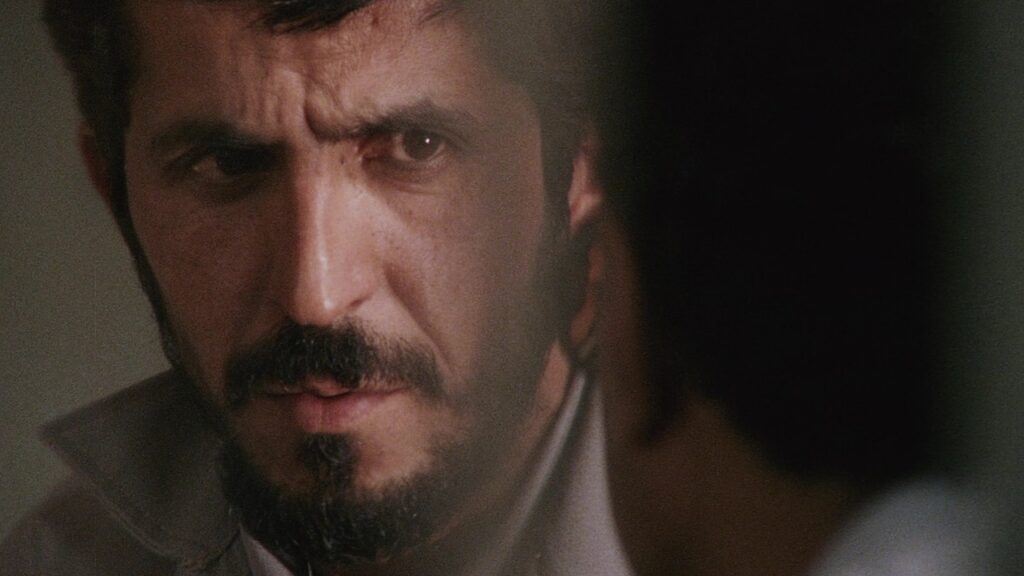

In a similar vein, the intellectual and moral conundrums that Iranian society confronted were central to Muhsin Makhmalbāf’s films. The Cyclist (Bāysīkilrān, 1987) by Makhmalbāf examines the tenacity and desperation of an Afghan refugee who competes in an endurance cycling competition to raise money for his wife’s medical care. Despite having a straightforward premise, the movie offers a powerful critique of exploitation, poverty, and the resiliency of the human spirit. By emphasizing the moral and psychological challenges faced by his characters, Makhmalbāf was able to effectively criticize the sociopolitical circumstances that marginalized populations in Iran face. The utilization of naturalistic performances was another characteristic of the Iranian New Wave. Iranian filmmakers frequently use amateur actors in their productions because they think this will result in more realistic and genuine performances. In Iranian New Wave films, this naturalistic aesthetic contributes to a feeling of closeness and immediacy that made it easier for audiences to empathize with the characters. The story of Samīrā Makhmalbāf’s 1998 film The Apple (Sīb) centers on two young sisters who are kept inside their house by their father. Makhmalbāf creates a story that feels genuine and unadulterated by using amateur performers, providing insight into the difficulties women have in traditional cultures. The choice to use amateur actors strengthened the sociological and psychological reality of the characters’ experiences while also giving the movie a starkly realistic foundation.

The Iranian New Wave became known for its philosophical storytelling, with many of its films using allegorical tales to examine existential issues and moral quandaries. Filmmakers created profound narratives by examining larger human and societal themes via the internal struggles of their characters. For example, Kiyārustamī describes a man who drives about Tehran looking for someone who will bury him after he commits suicide in Taste of Cherry (Ta‛m-i Gīlas, 1997). The film’s existential topic and minimalist aesthetic encourage spectators to consider issues of mortality, meaning, and the worth of life. Instead of offering definitive answers, Taste of Cherry lets the protagonist’s trip develop in an ambiguous manner, enabling viewers to interpret the significance of his quest for themselves.

Figure 7: A still from the film Taste of Cherry (Ta‛m-i Gīlas), directed by ‛Abbās Kiyārustamī, 1997.

Following the Islamic revolution, the Iranian New Wave—influenced by the sociopolitical climate of post-revolutionary Iran—developed a unique voice that distinguished it in the world of film. Within this movement, filmmakers used nuanced yet profound cinematic techniques to tackle difficult subjects including gender dynamics, personal identity, and societal roles.

Identity, Gender, and Society in Poetic Minimalism

New Wave films encourage viewers to decipher meaning beyond what is directly depicted by incorporating allegorical themes into realistic settings. Iranian poetic minimalism tries to create a meditative ambiance, focusing on the interior, emotional journeys of characters, in contrast to Western cinematic reality, which frequently emphasizes realistic images of life’s challenges. Iranian New Wave filmmakers frequently employ silence and allegory as potent narrative techniques. This method responds to Iran’s censorship restrictions while also being in line with the philosophical aspects of Islamic mysticism and Persian literature. In this sense, silence is not just the lack of word or sound; rather, it is a purposeful void that allows viewers to decipher hidden conflicts, tensions, or underlying emotions.

The Silence (Sukūt, 1998) by Muhsin Makhmalbāf is a prime example of this method. Khurshīd, a young blind youngster with a special sensitivity to sound, is the subject of the movie. The sounds Khurshīd hears as he moves through his environment influence his perception, making it harder to distinguish between the imagined and the actual. Since Khurshīd finds solace and meaning in rhythms that others might ignore, music itself here becomes a metaphor for his inner world. The film examines topics of perception, fragility, and the fight for independence in a constrictive culture through Khurshīd’s aural sensitivity. Makhmalbāf’s poetic use of sensory elements to communicate emotional landscapes and existential questions is highlighted by the interplay between sound and quiet in The Silence, which symbolizes how people see and internalize the world around them.

Additionally, the Iranian New Wave provides a sophisticated examination of society and personal identity, with a focus on gender roles and family relations. Iranian filmmakers frequently examine and analyze the larger sociocultural issues impacting individuals and groups in Iranian society through intimate character studies and personal storylines. Through these tales, New Wave filmmakers show how people’s lives are shaped by cultural norms, legal constraints, and conventional expectations.2Richard Tapper, ed. The New Iranian Cinema: Politics, Representation and Identity (London: I.B. Tauris, 2002), 91. The Circle (Dāyirah, 2000) by Ja‛far Panāhī is a pioneering illustration of this strategy. The movie tells several interrelated tales of Iranian women who challenge the country’s repressive social and legal systems. The Circle highlights the difficulties women encounter in a culture that limits their freedom and establishes their positions. Panāhī weaves the stories of several female characters together to create a tapestry of survival, resiliency, and subdued resistance to a system of oppression. A metaphor for the cyclical nature of systematic oppression is provided by the narrative framework, which frames each woman’s tale as a part of a broader, cyclical journey. A strong critique of gender discrimination in Iran is provided by the film’s unapologetic depiction of female characters negotiating a constrained culture, which also adds to the rising conversation about women’s rights in Iranian cinema.

Figure 8: A still from the film The Circle (Dāyirah), directed by Ja‛far Panāhī, 2000.

The Blue-Veiled (1995) by Rakhshān Banī-I‛timād offers yet another illustration of how Iranian New Wave filmmakers tackle issues of gender, identity, and society. The protagonist of the movie is a middle-aged male manufacturing owner who develops feelings for a female young, destitute factory worker. Banī-I‛timād examines the connections between love, social expectations, and class inequality through this relationship. The film highlights the emotional complexity of people who, despite social restraints, seek fulfilment and individuality while discreetly criticizing the gender and economic forces that drive Iranian culture. Banī-I‛timād humanizes her characters’ hardships by concentrating on their inner life, creating a sympathetic yet critical portrayal of Iranian society. Furthermore, the New Wave’s emphasis on social and psychological reality is reflected in Asghar Farhādī’s films, especially in About Elly (Darbārah-yi Ilī, 2009). In About Elly, a vacation takes a terrible turn when one of friends on the trip disappears. By analyzing the layers of societal expectations and individual accountability that influence the characters’ behavior, Farhādī uses this premise to investigate themes of truth, guilt, and collective responsibility. The movie offers a microcosm of Iranian culture through its portrayal of human relationships and ethical dilemmas in a collective context, illuminating the ways in which social norms and cultural expectations mold people. Farhādī’s intricate character interactions and meticulous attention to detail help to create a nuanced depiction of the social forces that influence moral decisions and personal identity.

These instances demonstrate how personal narratives are used as vehicles for broader social critique in the Iranian New Wave following the Islamic Revolution. These films give viewers a chance to reflect on the complexities of family responsibilities, social conventions, and personal agency in Iranian society by emphasizing commonplace events and close character analyses. With this method, filmmakers can examine gender, identity, and social expectations in poetic and philosophical ways.

Iranian New Wave Film’s Minimalism Following the Islamic Revolution

One distinctive element of Iranian New Wave filmmaking is minimalism, which heightens realism and establishes a direct line of communication between the viewer and the characters. Iranian filmmakers create a subtle authenticity that captures the simplicity of daily life by eschewing complex narratives, lavish visual effects, and copious amounts of dialogue. Subtle emotional responses are made possible by this minimalist approach, where every gesture, pause, and conversational sentence acquires meaning. ‛Abbās Kiyārustamī’s films are among the best representations of minimalism in Iranian cinema. Kiyārustamī’s use of lengthy takes is a prime example of minimalist filmmaking. The lengthy shots in Close-Up (1990) serve as both stylistic decisions and narrative elements that create a meditative ambiance. These extended moments are used by Kiyārustamī to depict the complex responses of his characters, especially in the courtroom sequences where Sabziyān faces the family he deceived. Long takes transform even the most basic motions into potent representations of vulnerability, regret, and guilt, allowing the viewer to feel the emotional strain uninterrupted. As the movie examines identity and the human yearning for acceptance and understanding, the individuals’ inner lives continue to be the main focus. Here, Kiyārustamī’s minimalist style eliminates superfluous distractions to highlight the unadulterated, emotional core of interpersonal relationships. The sparse use of language is another crucial element of Iranian cinematic minimalism. Kiyārustamī uses quiet and nuanced character interactions in films like The Wind Will Carry Us (Bād mā rā khvāhad burd, 1999), letting the stillness itself convey spoken feelings and ideas. The dialogue in this movie is sometimes brief and disjointed, which illustrates the gap between the protagonist, an urban outsider, and the people of the rural town. Their different worlds and points of view are symbolized by the absence of direct verbal communication. Silence becomes an active narrative technique as a result of this constrained use of words, which compels the spectator to focus on the emotional and physical cues. These films’ constrained speech and economical use of visuals also bring forth the intricacy and beauty of commonplace environments. In order to increase the realism of their stories, Kiyārustamī, Makhmalbāf, and other New Wave filmmakers place a strong emphasis on using natural settings, such as villages, city streets, and ordinary interior spaces. These commonplace locations, which are devoid of ornate lighting effects or set designs, become essential to the narratives and help to anchor the protagonists’ experiences in Iranian society.

Figure 9: A still from the film The Wind Will Carry Us (Bād mā rā khvāhad burd), directed by ‛Abbās Kiyārustamī, 1999.

Iranian New Wave directors frequently use metafictional devices to gently remind viewers that films are manufactured. Ja‛far Panāhī expands on this idea in The Mirror (Āyinah, 1997) by breaching the fourth wall halfway through the movie. By leaving the set, the young actress who is portraying the lead role essentially blurs the line between truth and fiction. Viewers are compelled by this sudden change to reevaluate the nature of narrative and the filmmaker’s influence on reality. Panāhī challenges viewers to consider the artificiality of cinematic traditions and the stories they consume by bringing attention to the production process. Iranian New Wave film’s non-linear and open-ended storytelling promotes a contemplative viewing experience in which viewers actively participate in the meaning-making process rather than being passive recipients of a predetermined narrative.3Hamid Reza Sadr, Iranian Cinema: A Political History (London: I.B. Tauris, 2006), 42. The philosophical foundations of Iranian film, which frequently use Persian poetry and Sufi mysticism to examine themes of self-discovery and the pursuit of truth, are consistent with this participatory approach. These films respect the complexity of the human experience by allowing for interpretation and admitting that there are some questions that cannot be answered with certainty. By highlighting the viewer’s responsibility to interpret and derive meaning from each story, these stylistic choices subvert conventional narrative structures.

The Iranian New Wave’s Legacy Following the Islamic Revolution

Both Iranian and worldwide cinema have been profoundly impacted by the Iranian New Wave, leaving a legacy that continues to influence filmmaking today. This cinematic movement, which arose under stringent political, social, and cultural constraints, demonstrated the potential of minimalism, poetic approach, and philosophical investigation to strike a profound chord with viewers worldwide. Iranian New Wave cinema has influenced filmmakers not just in the Middle East but also in Europe, Asia, and the Americas, demonstrating its cross-border effect. Iranian filmmakers’ minimalist, poetic, and philosophical approach provides a distinctive contrast to the prevalent cinematic languages of European art cinema. Iranian New Wave cinema has influenced filmmakers worldwide to investigate minimalism, character-driven storylines, and the symbolic possibilities of ordinary life by focusing on straightforward yet deep stories.

The presence of Iranian New Wave cinema at important film festivals is among its most noteworthy global accomplishments. ‛Abbās Kiyārustamī, Ja‛far Panāhī, Muhsin Makhmalbāf, and Asghar Farhādī have all received some of the most coveted accolades at cinema festivals like Cannes, Venice, and Berlin. For example, the 1997 Cannes Palme d’Or winner of Kiyārustamī’s Taste of Cherry signaled a shift in the world’s perception of Iranian film. These honors brought the intricacies and complexity of Iranian narratives to a wider worldwide audience while also validating Iranian cinema’s distinctive storytelling style. This recognition paved the way for other Iranian filmmakers and brought attention to a cinema industry that, until the late 20th century, was mainly unknown outside of Iran. Filmmakers in Asia and Europe have been especially impacted by Iranian New Wave cinema, which has inspired them with its emphasis on character-driven narrative, utilization of authentic settings, and use of ambiguity.

Figure 10: A still from the film Close Up, directed by ‛Abbās Kiyārustamī, 1990.

Iranian film has influenced the work of directors like Japan’s Hirokazu Koreeda and Taiwan’s Hou Hsiao-Hsien. Like their Iranian counterparts, they place a strong emphasis on quiet, simplicity, and subtle emotional changes. The realism and emphasis on marginalized lives of the Iranian New Wave have also been incorporated by European filmmakers such as the Belgian Dardenne brothers. A sense of intimacy that appeals to viewers from all cultural backgrounds is produced by the Dardennes’ use of handheld cameras, natural light, and everyday settings, which are stylistic choices reminiscent of Iranian New Wave directors. Academic interest in Iranian cinema’s distinctive stylistic features and philosophical foundations has increased as a result of its widespread recognition. Critics and academics such as Laura Mulvey have examined how Iranian filmmakers employ minimalism to delve into existential topics, transforming seemingly insignificant, ordinary situations into meaningful meditations on freedom, identity, and life. ‛Abbās Kiyārustamī’s Close-Up (1990), for instance, has been the subject of much research due to its creative fusion of fiction and documentary, which examines identity and reality in ways that defy accepted narrative structures. The impact of this film can be observed in the emergence of “hybrid” cinema, a movement that has gained popularity in art-house circles throughout the world and blends fictitious and real-life components to explore deeper realities.

Despite having had a huge influence on international film, Iranian New Wave cinema is still developing in Iran, where modern filmmakers are expanding on the New Wave’s ideas to tackle fresh sociopolitical and cultural issues. The movement’s emphasis on moral ambiguity, realism, and character-centered storytelling has been carried further by these directors, who have modified these approaches to better represent contemporary Iran. They deal with problems including generational disputes, gender inequality, class inequality, and individual liberty under social constraints and despite censorship. One of the most well-known modern Iranian directors, Asghar Farhādī, has built on the New Wave’s tradition by examining difficult moral conundrums within the context of Iranian culture. Internationally acclaimed, his 2011 film A Separation (Judā’ī-i Nādir az Sīmīn) explores the moral and interpersonal tensions in a divorcing family. Farhādī exposes the larger conflicts between tradition and modernity, as well as between individual desire and social duty, that are fundamental to Iranian life by concentrating on the personal struggles of his characters. By winning the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film, A Separation strengthened Iranian cinema’s standing internationally and emphasized the potency of narratives grounded in psychological nuance, realism, and ethical analysis. A development in the portrayal of Iranian women is also evident in Farhādī’s work. The female characters in Farhādī’s films are given agency, voice, and complexity, in contrast to the older New Wave films that frequently portrayed them as silent symbols of sorrow or resiliency. For example, Sīmīn, a character in A Separation, is battling for her daughter’s freedom and right to a better life in addition to custody of her daughter. Both Iranian and foreign audiences find resonance in Farhādī’s subtle depiction of women battling with both personal goals and societal expectations, as they recognize themselves mirrored in his characters. The work of female directors like Rakhshān Banī-I‛timād demonstrates another intriguing development in the heritage of the Iranian New Wave. Films by Banī-I‛timād, including Under the Skin of the City (Zīr-i pūst-i shahr, 2001), explore the lives of marginalized Iranians, especially women, as they deal with social pressures and financial difficulties. Banī-I‛timād’s emphasis on common people carries on the New Wave’s dedication to realism while contributing a distinctively female viewpoint to Iran’s sociopolitical environment.4Laura Mulvey, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” Screen 16, no. 3 (1975): 12.

Figure 11: A still from the film A Separation (Judā’ī-i Nādir az Sīmīn), directed by Asghar Farhādī, 2011.

To portray the realities of Iranians living abroad, contemporary Iranian filmmakers also examine problems of migration, exile, and diaspora. Iranian cinema is viewed through a diasporic lens by filmmakers such as Maryam Kishāvarz and Bahman Qubādī, who concentrate on the ways that Iranian identity is reinterpreted internationally. A Time for Drunken Horses (Zamānī barāyi māstī-i asb-hā, 2000) by Qubādī explores the struggles of Kurdish families along the Iran-Iraq border, illustrating the grim reality of Iran’s ethnic minorities. Circumstance (2011) by Kishāvarz, on the other hand, tackles the lives of young Iranians who are struggling with repression and sexuality in a way that is both globally relevant and particular to Iran’s own social fabric. As modern filmmakers tackle the unique problems of the twenty-first century while embracing the movement’s emphasis on lyrical realism, ethical investigation, and narrative innovation, the legacy of Iranian New Wave cinema lives on. These directors have preserved Iran’s impact on international cinema by striking a balance between the New Wave’s methods and their own distinctive voices, proving that the Iranian New Wave’s tenets remain ageless and flexible.

Conclusion: Iranian Film’s Development and Prospects

Iranian cinema has changed dramatically throughout the years due to its distinct cultural, social, and political influences. The 1960s and 1970s pre-revolutionary era was characterized by a separation of popular escapism from a few films that made critical social commentary. Filmmakers like Suhrāb Shahīd Sālis, ‛Abbās Kiyārustamī, Dāryūsh Mihrjū’ī, Nāsir Taqvā’ī, Parvīz Kīmiyāvī, Ibrāhīm Gulistān, Furūgh Farrukhzād, and others started to pave the way for change by defying commercial trends and utilizing a distinctly Iranian visual and narrative style to explore intricate social themes. The foundation for poetic minimalism, a distinctive characteristic of Iranian New Wave film, was established by this early attempt to combine realism with symbolic narrative.

Iranian cinema experienced significant changes after the Islamic Revolution of 1979 as a result of stringent new censorship laws that forbade specific portrayals and stories. Both Iranian and foreign audiences found great resonance in the new, introspective style that was cultivated by such limitations and depended on metaphor and inference. The emergence of the Iranian New Wave was characterized by its emphasis on moral ambiguity, everyday struggles, and the investigation of identity under sociopolitical restrictions. This movement was spearheaded by filmmakers like as ‛Abbās Kiyārustamī, Ja‛far Panāhī, and Muhsin Makhmalbāf, who produced films that not only questioned established narrative frameworks but also encouraged audiences to reflect philosophically on issues of freedom, death, life, and individual choice. Technological and socio-political developments present Iranian film with both opportunities and problems as it develops. A number of possible paths for Iranian cinema’s future are suggested by the rapid development of digital media, changing social environments, and growing interest in a variety of cinematic voices worldwide.

Iran’s sociopolitical environment continues to have a big impact on its filmmaking. Censorship and content restrictions continue to influence the themes and methods used by filmmakers, frequently encouraging them to come up with fresh approaches to sociopolitical criticism. However, as evidenced by the work of younger filmmakers who employ ingenuity and technology to overcome constraints, these difficulties have also fostered an atmosphere that promotes innovation. For example, the covert filmmaking stylistic innovations, which frequently address the status of personal freedom and civil rights, demonstrate the flexibility and tenacity of Iranian filmmakers in the face of political hardship. Iranian filmmakers will probably keep using allegory, metaphor, and other oblique techniques to tackle current concerns in the future. Issues like economic inequality, freedom of speech, and gender equality may gain prominence in Iran due to the country’s growing social consciousness, representing the worries of a younger, more connected generation.

Digital technology’s introduction has drastically changed how films are made and seen, giving Iranian filmmakers new ways to connect with viewers around the world. Iranian filmmakers now have more options than only traditional distribution channels thanks to digital platforms like Netflix, YouTube, and smaller international film streaming services. These platforms give filmmakers the opportunity to get around some government restrictions and present a greater variety of stories that might not otherwise be viewed. Because of its accessibility, Iranian cinema may feature a wider variety of viewpoints and views by promoting innovation with form and substance. Additionally, the cost of filming has decreased due to digital technology, democratizing the Iranian film industry. With the use of inexpensive equipment and digital editing techniques, aspiring filmmakers who might not have access to substantial funding or other resources can now produce and release films. This change could allow for a more varied portrayal of the Iranian experience by introducing new voices to Iranian cinema. Furthermore, the emergence of virtual reality and mobile filmmaking presents intriguing opportunities for fresh storytelling styles that can enhance Iranian cinema’s traditional focus on intimacy and realism.

As more filmmakers consider how the environment and climate affect people’s lives, environmental themes are becoming more prevalent in Iranian filmmaking. Filmmakers now have a new way to examine how individuals interact with their surroundings in light of Iran’s environmental problems, which include desertification, air pollution, and water scarcity. Iranian film is ideally adapted to tackle environmental issues in a complex and powerful manner because of its distinctive emphasis on the natural world as a mirror of human experience. Future Iranian films might potentially start addressing international issues more directly, such as social justice, globalization, and the role of technology in society, adding a new level of significance and resonance with viewers throughout the world. Iranian filmmakers may work with foreign directors more frequently as their reputation grows, producing cross-cultural productions that broaden Iranian cinema’s appeal and impact.

Inspired by digital technology and the Iranian New Wave, younger filmmakers are starting to push the limits of documentary and narrative filmmaking by further experimenting with form. Iranian film is renowned for its hybrid style, which can develop further to include elements of interactive narrative, virtual reality, and avant-garde aesthetics. These developments enable Iranian filmmakers to keep providing viewers with an introspective, engrossing experience that conflates fiction and reality. As Iranian filmmakers experiment with new technologies, experimental cinema—which subverts established storytelling conventions and employs sound and visual symbolism in novel ways—may become increasingly well-known. This strategy would guarantee the ongoing relevance and development of Iran’s cinematic voice by enabling them to explore even more deeply the existential and philosophical topics that have characterized Iranian New Wave cinema.

Iranian film is at a turning point in its history, ready to continue the New Wave’s heritage while negotiating new artistic, technological, and social environments. Its focus on realism, reflection, and philosophical depth has struck a chord with viewers all across the world, inspiring filmmakers from a variety of backgrounds and winning praise from critics at important film festivals. Iranian cinema continues to be a potent voice in global cinema thanks to its tenacity, inventiveness, and dedication to examining the human condition. It tells stories that are both intensely personal and engrossing to all audiences.

Cite this article

This article offers a critical analysis of the evolution of Iranian cinema, with particular attention to the transition from pre-revolutionary film culture to the emergence of post-revolutionary and New Wave movements. It investigates how Iranian filmmakers have forged a unique cinematic language—one that blends aesthetic minimalism with layered socio-political critique—through techniques such as poetic realism, allegorical narrative, and philosophical abstraction. Drawing on the works of key auteurs, the article examines how Iranian cinema has consistently negotiated themes of existential anxiety, identity formation, and sociocultural constraint under conditions of censorship and ideological surveillance. Through close textual and formal analysis, the article highlights how New Wave directors utilize character-centered storytelling, sustained silence, metaphorical imagery, and spatial symbolism to articulate universal human concerns within the specificities of the Iranian experience. Ultimately, this study situates Iranian cinema as a paradigmatic example of how national film traditions can serve as enduring platforms for philosophical reflection and global cultural engagement, despite—or perhaps because of—political and artistic limitations.