Seventeen Days to Execution (1956)

Director: Hūshang Kāvūsī

Year of Release: 1956

Screenplay: Hūshang Kāvūsī

Source Material: Phantom Lady, a novel by Cornell Woolrich (1942)

Music: Vārtān Āzārīyān

Cinematography: Mahdi Amīr Qāsim

Cast: Nāsir Malik-Mutī‛ī, Muhsin Mahdavī, Sūzān, Mahīn Mu‛āvinzādah, Izzatallāh Vusūq

Production Company/Producer: ‛Azīzallāh Kurdvānī, Farajallāh Nasīmīyān

Black and White

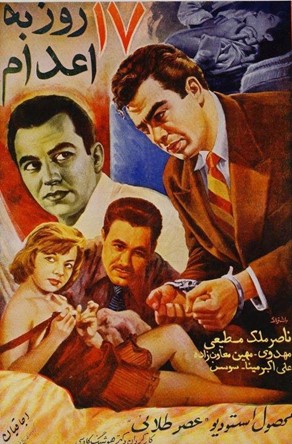

Figure 1: Poster of the film 17 Days to Execution (Hifdah Rūz bi I‛dām), Hūshang Kāvūsī, 1956

A milestone feature directed by an influential film critic, Hifdah Rūz bi I‛dām (17 Days to Execution, 1956) stands among the most notable unseen films of mid-century Iranian cinema.1I use the numerical form of the film title, instead of spelling out “seventeen” because this matches the original film posters and publicity material. It is a noteworthy change from the novel. Woolrich’s chapter titles count down the days before the execution using words instead of numerals. Also all translations are by the author unless otherwise noted. The relentless and fatalistic plot was adapted from Phantom Lady (1942), a novel written by Cornell Woolrich under the pen name William Irish. The setup is the same in both versions. After quarreling with his wife, a man spends an aimless evening with a woman he meets in a café. The two attend a cabaret show together but never exchange names. He returns home to find the police in his home, and a detective reveals to him that his wife has just been murdered. The phantom lady from the café becomes his alibi, but no one with whom they interacted that night seems to remember either of them accurately. The film provoked strong opinions immediately after its release and has continued to do so in the years since—even while it has remained largely inaccessible to viewers.

Amīr Hūshang Kāvūsī, a critic who prided himself on his cultivated taste (evident in his coinage of the pejorative term “fīlmfārsī”), touted this debut feature film as the first true policier made in Iran.2Transliteration of Persian text follows the publication’s standard scheme. Transliteration of names, including “Houshang Kavousi,” follows the person’s own preference wherever possible. He preferred to use the French term for a film based on a police novel. This invited comparison of the film—hinting at superiority—to other examples of crime thrillers or film noir from this period in Iran. Prominent among them was the commercially successful Faryād-i Nīmah Shab (Midnight Cry) directed by his rival, Samuel Khāchīkīyān in 1961. To understand the stakes of this comparison, and the critical controversy that it entailed, it is helpful to consider the institutional life of the crime film during Kāvūsī’s early career. 17 Days, and the genre to which it belonged, linked the critical establishment with the film industry in Iran in the 1950s and 1960s. The film may not have had a blockbuster run or a warm reception by critics, but it illustrates how film noir thrived globally (both commercially and intellectually) due to the way its modernist style was able to cross geographies and construct an imagined cinematic elsewhere.

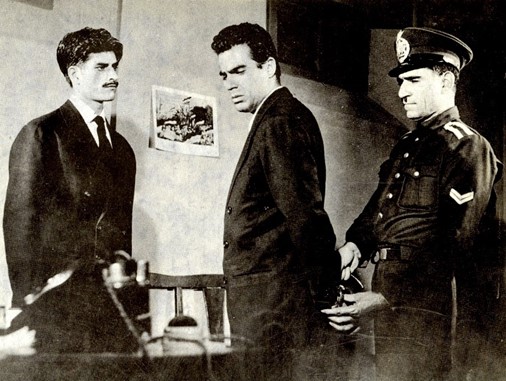

Figure 2: Jamshid Kāvūsī and Hūshang Kāvūsī, along with Naser Malek Motiee and several other actors of the film 17 Days to Execution, 1956

The origin story of 17 Days reflects, in many ways, the transformations in global film education in the decades after WWII. University film education had existed in various forms since the 1910s, but at the time Kāvūsī sought education in France, film schools were beginning to take shape according to postwar internationalist values. They emphasized recruitment of international students and developed a curriculum that continues to influence standards in university film programs. In Italy, the postwar reshaping of the Centro Sperimentale di Cinematographia provided training for filmmakers from around the world. In France, the main film school from 1944 through its restructuring in 1985 was IDHEC, or the Institut des hautes études cinématographiques, and was renamed La Fémis after 1985. Kāvūsī went to France to study law but quickly switched his concentration and joined IDHEC in its early years when the French film director Marcel L’Herbier was working to establish it as a major player in the education of filmmakers from around the world. Kāvūsī was the first Iranian student at the school, and he complemented this specialization with studies of French literature in Paris. Since this time, the school has provided training, and the archive of La Fémis/IDHEC has provided researchers with source material from filmmakers around the world. In the case of 17 Days, the only digital preservation that has been conducted came from material deposited by La Fémis at the Centre national du cinéma et de l’image animée (CNC). The institute provided training for Kāvūsī then. Now, it provides us with access, albeit fragmented, to about a third of the scenes from his film.

Figure 3: Jamshid Kāvūsī and Hūshang Kāvūsī, along with Naser Malek Motiee, Sussan, Vartan, and Gohari, and several other actors of the film. 17 Days to Execution, 1956

Upon completing his education, Kāvūsī set forth as a prolific writer of film criticism and as a filmmaker in Iran in an environment of newly forming film studios and magazines. Not only were film magazines an emergent form at this time, respected intellectual journals were steadily, if sometimes reluctantly, opening space for the discussion of cinema. Kāvūsī, a confident writer with a French education in literature and cinema, helped to temper some of this reluctance. An initial discussion of his connection to early studios in Tehran, a lesser known part of his career, can be found in a feature article on Studio Diana Film in Sitārah-yi Sīnimā. The article discusses the outlay of capital by Sānāsār Khāchātūrīyān, owner of Cinema Diana and Studio Diana, for professional equipment as well as the assembly of personnel involved in the first experimental features of the studio. Worthy of note is the discussion of multi-ethnic and international composition of professionals in directing, editing, cinematography, and makeup coming from Iran, Armenia, Eastern Europe, and South Asia. Kāvūsī’s contribution to the progress of Mājarā-yi Zindigī (Life’s Adventure, 1955) is discussed alongside Samuel Khāchīkīyān’s work on Āyishah, which would eventually become Dukhtarī az Shīrāz (The Girl from Shiraz, 1954). The article highlights Kāvūsī’s expertise, due to his recent education in France, as a bellwether of quality film production. It also promotes Sardar Sager, who had recently moved to Tehran from Bombay where he had worked as a film music director. Sager’s melodrama of young love, Murād (1954), brought a form of filmmaking expertise from Bombay to the fledgling Tehran studio. Overall, the article provides a portrait of three filmmakers at work with the new facilities made available by Khāchātūrīyān.3“Estudio Diana Film: Mujahhazṯarīn Istūdīyu’ī ki ḥanūz yak fīlm-i khūb natavānistah ast tāhīyyah kunad (Studio Diana Film: The Best-equipped Studio Has Yet to Produce a Good Film)” Sitārah-yi Sīnimā 3 (26 Bahman, 1332 [February 15, 1954]): 20-21. These three would go on to establish some of the key parameters of the cinematic output of the coming fifteen years.

Figure 4: Hūshang Kāvūsī speech at the Faculty of Dramatic Arts Hall, Tehran, 1970

At this time in the early 1950s, the crime thriller was among the most adaptable genres for expanding global markets for films and other forms of mass-media entertainment. Crime and detective films spanned popular fiction, radio plays, and other films just as they spanned long distances, seeming to draw energy from crossing the borders of a given medium just as much as they drew energy from crossing national borders. Neil Verma points out how the golden age of American radio drama and film noir overlapped and programs that incorporated noir tropes represented half of American evening radio drama by the 1950’s.4Neil Verma, “Radio, Film Noir, and the Aesthetics of Auditory Spectacle,” in Kiss the Blood Off My Hands: On Classic Film Noir, ed. Robert Miklitsch (Urbana, University of Illinois Press, 2014). Neil Verma, Theater of the Mind: Imagination, Aesthetics, and American Radio Drama (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012), 91–114, 181–202. In Iran, there was an increasing amount of crime fiction available in the 1950s and 1960s in translation, some of it translated in film magazines such as Sitārah-yi Sīnimā. In particular, the late 1950s and early 1960s in Iranian filmmaking marked a heyday for the crime thriller. According to Mas‛ūd Mihrābī, over half of the local film productions deployed crime film conventions.5Mas‛ūd Mihrābī, Tārīkh-i Sīnimā-yi Īrān az Āghāz tā 1357 (History of Cinema in Iran Until 1357 [1978]), 11th printing (Tehran: Nazar, 2016), 111. This included urban thrillers by Khāchīkīyān as well as smuggling films such as Sudāgarān-i Marg (Merchants of Death, directed by Nāsir Malik-Mutī‛ī, 1962), and Mū Talā’ī-i Shahr-i Mā (The Blonde from Our City, directed by ‛Abbās Shabāvīz, 1965). Broadcast networks also contributed to this popularity. Radio detective programs such as Johnny Dollar (a translated version of Yours Truly, Johnny Dollar, 1949-1962) were household names in Iran, and the television networks complemented cinema screenings by replaying dubbed versions of police and detective films in weekly programming.

Figure 5-6: Left: Magazine advertisement for Mū Talā’ī-i Shahr-i Mā (The Blonde from Our City(, directed by ‛Abbās Shabāvīz, 1965. Right: Magazine advertisement for Sudāgarān-i Marg (Merchants of Death), directed by Nāsir Malik-Mutī‛ī, 1962

Figure 7: A Screenshot from the film Mū Talā’ī-i Shahr-i Mā (The Blonde from Our City(, ‛Abbās Shabāvīz, 1965

This phenomenon has a particular life in Iran, but it is important to note the crime film’s global currency. For instance, the industry in Egypt had its share of policiers with Atef Salem as a standout director in the genre, and the Navketan production company in India produced several important crime films starring studio co-founder Dev Anand. Navketan films became staples in cinemas across large parts of Asia and Africa. One particularly interesting overlap is the fusion of the crime thriller with the cabaret dancer plot, which features prominently in popular Iranian cinema as well as mid-century Mexican cabaretera (dance hall) films.6On the cabaretera see Joanne Hershfield, Mexican Cinema/Mexican Woman, 1940-1950 (Tempe: University of Arizona Press, 1996).

Alfred Hitchcock was a household name in many of these local fan cultures as he certainly was in Iran, and many of these directors were compared in their local press, often to their dismay, as the “Hitchcock of ___.” Samuel Khāchīkīyān was the director in Iran for whom this (largely unwanted) association with Hitchcock stuck. He brought an element of Expressionism and gothic horror to the crime genre that propelled him to become one of the most commercially and critically successful directors of the early 1960s. In 1961, Khāchīkīyān made both the number one and the number two box office hits in Iran: Faryād-i Nīmah Shab (Midnight Cry) and Yak qadam tā marg (One Step to Death), both representing the most recognizably film noir productions of his career. It was this combination of popularity and recognizability that fueled the feud between Khāchīkīyān and Kāvūsī, but more on that shortly. For now, it is important to note that 17 Days to Execution came into being in this environment of rich possibility for the crime film.

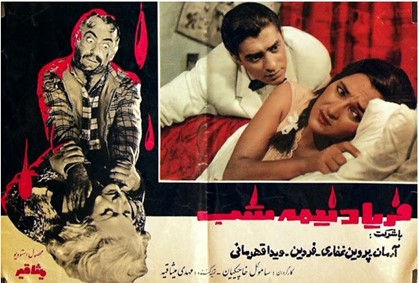

Figure 8: Poster of the film Faryād-i Nīmah Shab (Midnight Cry), Samuel Khāchīkīy, 1961

Kāvūsī drew source material for the film from two of the most prominent figures in the global circulation of film noir at the time: Cornell Woolrich and the German film director Robert Siodmak. The appeal of Woolrich’s Phantom Lady (1942) makes good sense for a critic aspiring to make the first film noir or policier in Iran. Woolrich was one of the most widely adapted writers of hard-boiled fiction globally. His biographer notes, for instance, the translatability of his work in Argentina, the USSR, Japan, France, and Germany.7Frances Nevins, Cornell Woolrich: First You Dream, Then You Die (New York, The Mysterious Press, 1988), 569-575. His presence in Iran thus fits within the context of this broader adaptation of his work into films around the world. At the time that Kāvūsī was working on 17 Days, the most famous film adaptation of Woolrich’s work, Hitchcock’s Rear Window, was making best-of lists in journals including Cahiers du Cinéma and Movie, which were read by critics in Iran. Woolrich’s writing was not always credited in publicity material, but Paramount’s posters and the full-page advertisement that circulated in film magazines in the late summer of 1954 in Iran featured the author’s name.8Examples of journal publications of the poster mentioning Woolrich include Modern Screen, September, 1954, p. 5. and Photoplay, December 1954, p. 5. Sitārah-yi Sīnimā itself published a five-page translated summary of the film in the summer of 1955 and credited Woolrich with the story in the title material for that piece.9“Panjarah rū bi hayāt (The Window Facing the Garden)” trans. Bahrām. Sitārah-yi Sīnimā, 34 (31 Khurdād, 1334 [June 22, 1955]): 34-38.

In addition to the novelist’s undeniable influence in Iran, Woolrich’s novel had been adapted ten years before Kāvūsī by Robert Siodmak and the screen writer and film producer, Joan Harrison. Siodmak’s career in Hollywood helped to define the now well-known narrative of exiled German filmmakers bringing their talents to B-films in 1940s Hollywood. His adaptation of Phantom Lady marked a shift into the full-form film noir style for which he would become known, and it is worth noting that his work was often compared to Hitchcock’s. Harrison, by the time she produced Phantom Lady, had an established career working with Hitchcock, contributing to several of the most successful screenplays that established Hitchcock’s global brand. They proved formidable collaborators, and, thus, the timing was perfect for the young Kāvūsī to take notice of their adaptation of Phantom Lady. He began film school at IDHEC /La Fémis in 1947, the year of the film’s release in France, and was in fact living there, not only during Phantom Lady’s long theatrical run, but indeed during the early French critical discussions of film noir.10See James Naremore, More than Night: Film Noir in its Contexts (Oakland, University of California Press, 2008).

17 Days’ style aligns with iconic scenes from cinephiles’ favorite crime films. It gestures to the famous Austrian-American director Fritz Lang with its iconography of fate on the face of a clock. Its detective is more hard-boiled than Woolrich’s. Its staging recalls Siodmak’s nervous approach to space: both films’ cameras craned around witnesses and challenged continuity norms with eccentric positioning of actors’ heads. The scenes from 17 Days are layered with references to literary and film noir that the director would have known from his education in Paris and his work as a film critic. The film’s interest in not only the unreliability of its witnesses but in their vulnerability is very Woolrichian, and its final sequence in an automobile after we learn the killer’s identity follows Siodmak’s staging of suspense.

Figure 9: A Screenshot from the film 17 Days to Execution (Hifdah Rūz bi I‛dām), Hūshang Kāvūsī, 1956

Woolrich’s stories may have been exciting to adapt, but the specific plot of Phantom Lady presented problems for an adaptation in Iran because the novel flips the usual process of detection and conviction. The courtroom scene ends, with a death sentence, by the end of what would become the screenplay’s first act. Kāvūsī’s title thus references the fatalistic plotting in which each of the novel’s chapter titles counts down to the day of Scott’s scheduled execution (he is named Nāsir in the film and is played by Nāsir Malik-Mutī‛ī). A second detection plot is initiated in the novel by Scott’s paramour, Carol, whose relationship with him was the cause of Scott’s marital spat and subsequently provided the prosecutor with a motive for the murder. The novel thus combines a wrong-man plot with a gaslight plot, with its typical climactic scenes presented out of order. A fan of hard-boiled fiction might find its reversals and restructurings of detection plots inventive, but without such context it is an odd text even before being translated. The negative review of 17 Days in Sitārah-yi Sīnimā mentions specifically that this aspect of the plot pushes the limits of suspension of disbelief.11“Intiqād bar Fīlm-hā-yi Haftah: Hifdah Rūz bi I‛dām (Critique of Films of the Week: Seventeen Days to Execution)” Sitārah-yi Sīnimā 94 (9 Day 1335 [December 30, 1956]): 8-9. Even Siodmak’s Hollywood version had changed the story so that Carol was Scott’s secretary who pined for him but only formed a couple with him after clearing his name. The Hollywood version streamlined many of the coincidences and multiple voices, whereas Kāvūsī chose a more faithful adaptation. As a result, the critics of 17 Days questioned the romantic relationships in the film, struggling to make sense of how Nāsir managed relations with three women simultaneously: his wife, the stranger at the café, and the woman who seeks to clear his name. These relationships were implausible to reviewers, especially considering that the story was meant to portray the main character as a vulnerable and precarious investigator. The circumstances of the protagonist thus misaligned with forms of masculinity that would soon become the norm in popular genre films made in Iran.

Figure 9: A Screenshot from the film 17 Days to Execution (Hifdah Rūz bi I‛dām), Hūshang Kāvūsī, 1956

17 Days might have been more effective had it emphasized the story’s sense of dread and vulnerability, but this adaptation tended to favor the clean precision of a procedural format. The film was a kind of demonstration of mastery, but that did not save it. On the contrary, it was precisely these purist citations, these demonstrations of expertise, that critics targeted. They called the film “just a series of moving theories of filmmaking,” and questioned Kāvūsī’s cavalier use of unusual camera angles and pacing.12“Intiqād bar Fīlm-hā-yi Haftah,” 9. These images created in the film are layered with references to film noir. Knowledgeable as they were, the citations failed to land with Kāvūsī’s fellow critics or with audiences and were thoroughly critiqued when the film was released. Notably, in some reviews the author’s identity is not listed, including the particularly harsh one in Sitārah-yi Sīnimā. According to film historian Ahmad Amīnī, Kāvūsī believed that this article was written by Hazhīr Dāryūsh who wrote a regular column for the magazine.13For a discussion of these various theories, see Ahmad Amīnī, Sad Fīlm-i Tārīkh-i Sīnimā-yi Īrān (A Hundred Selected Films of the Iranian Cinema) (Tehran: Shaydā, 1993), 38. One final point of speculation about this feud: one of the essays strongest terms of criticism, “ideological spasm” (sikti-hā-yi īdi’uluzhīk), was an unusual term that Khāchīkīyān used in his own writing. It is not impossible that he had a hand in writing the essay or at least was in conversation with those who did. For Khāchīkīyān’s use of “ideological spasm,” see Sitārah-yi Sīnimā 29 (23 Farvardīn, 1334 [April 13, 1955]): 6. Even if this cannot be ascertained, Dāryūsh wrote a negative review of the film in the journal Umīd-i Īrān. Other accounts suggest that the article was written collectively by the editorial staff at the magazine and possibly by the editor-in-chief at the time, Robert Ekhart, which may have led to an act of retaliation in which Ekhart’s name was removed from the magazine’s credits on a technicality.14The credit, for more than eighty issues, did not include a name and instead said “in cooperation with our colleague.” Robert Ekhart discussed running into trouble over the fact that someone had reported his disqualifying age to the Ministry of the Interior in “The Story So Far,” Sitārah-yi Sīnimā 101 (28 Bahman, 1335 [February 17, 1957]). Kāvūsī was only one possible suspect, since others were feuding with the magazine’s leadership at the time. The collaborative explanation makes sense given the patchwork structure of the long article, its use of the first-person plural, and the regretful tone at the outset when the author(s) explain the awkwardness of taking Kāvūsī, their fellow critic, to task. Further, Kāvūsī’s own reputation for publishing hot takes in reviews of Iranian films did not do him any favors when it came time to release his own feature. The criticism of his film also clearly illustrates the charged internal politics that characterized the feud-heavy scene of Iran’s film intellectuals at the time.

Figure 10: A Screenshot from the film 17 Days to Execution (Hifdah Rūz bi I‛dām), Hūshang Kāvūsī, 1956

There was something about this genre that seemed to fuel enthusiasm as well as animated disagreement. To see how the crime film functioned for these recurring disputes, let me return to one of the most dramatic points of tension: the public feud between Khāchīkīyān and Kāvūsī. Kāvūsī’s assessments of Khāchīkīyān’s work are summed up in the title of his review for Khāchīkīyān’s Midnight Cry in which he labelled it “a counterfeit film,” attacking the work because it “exudes a foreign smell in the movie theaters.”15These comments are compiled from a series of earlier interviews with the director in Ghulām Haydarī, “Hālā Dīgār Dastam Mīlarzad… Samuel Khāchīkīyān, Nukhustīn, Sābitgadamtarīn, va Mubtakirtarīn Kārgardān-i Fīlm-i Jinā’ī [Now My Hands Are Shaking… Samuel Khachikian first, most steadfast, and most inventive director of Crime Films],” Māhnāmah-ye Sīnimā’ī-i Fīlm 278, no. 19 (November 2001): 40- 42. There were well-worn satires in the press at the time that called out fakers and dandies who were into a modernist style but merely as flashy appropriation, and Kāvūsī’s takedown of Midnight Cry recalls some of that.16For an extensive exploration of the 1950s dandy satirical type, see Jamshīd Vahīdī, Jīgulu: Khāṭarāt-i Mamūsh Pushitīyān [Gigolo: A Memoir of Mamoosh Pochettian, Famous Gigolo of Islambol Street] (Tehran: Intishārāt-i Sipīd va Sīyāh, 1957), 126. Most of Khāchīkīyān’s films from this period included some form of cynical brutality, gramophone jazz, a criminal underworld, femme fatale plots, and location shooting of Tehran at night, and Midnight Cry is saturated with all of these. I did not find an export record for the similarly titled but distinct A Cry in the Night (directed by Frank Tuttle, 1956) in the Middle East distribution records in the Warner Bros. archive, but the film played in Tehran at the Warner-affiliated Cinema Rex in October of 1958. It was billed as a new release in Sitārah-yi Sīnimā, “the latest production about crime and passion by the Warner Bros. Company.”17Advertisement for A Cry in the Night, Setare-ye Cinema 180, 13 Mehr, 1337 (October 5, 1958), 37. Its translated title, Faryād-i Nīmah Shab, was identical.18The plot of A Cry in the Night bears some relation, not to Khachikian’s film of the same translated name, but to Storm in Our City (also directed by Khāchīkīyān, 1956) which was released later that year and plays on a similar terror of a mentally ill and violent man menacing a young woman in a remote building. Midnight Cry’s score is a collage of fragments from mambo albums and Nicholas Ray melodramas (the director of Rebel Without a Cause released the year before in 1955). Khāchīkīyān’s score even borrows music from an LP presented by Alfred Hitchcock titled “music to be murdered by.”19Jeff Alexander, Alfred Hitchcock Presents: Music to be Murdered By, Imperial, 1958. As a film full of allusions, and the top grossing Tehran production of the year, it made for a large target. In addition, Midnight Cry’s characters and its mise-en-scène bear strong similarities to Gilda (Charles Vidor, 1946). The plot’s two triangles each feature the character Zhīlā, a name too close to Gilda to be an accident, who is married to a crime boss (a counterfeiter of US currency himself). These love triangles, and the grand staircase on which they play out, seem to welcome comparisons to Gilda even if the director publicly disavowed them.

Figure 9: Screenshots from the film Faryād-i Nīmah Shab (Midnight Cry), Samuel Khāchīkīy, 1961

It is not just the fact of Gilda being adapted that was the problem, however. It was an issue with Gilda’s provenance that featured in the dispute. After all, Kāvūsī’s film was just as enmeshed in the fabric of crime-film citation and he was taken to task by his own colleagues for this very reason. In his review of Khāchīkīyān’s Midnight Cry, Kāvūsī told his readers that he learned by accident that the producer Mahdī Mīsāqīyyah had the only Tehran print of Gilda, presumably to copy it in detail, in the months during which Midnight Cry was in pre-production and production. Kāvūsī had wanted to program the film for a repertory screening.

About a year ago I visited the owners of the print of Gilda to inquire about showing it in a program at the ciné club. They told me that it was with Mīsāqīyyah. When I asked if it would be possible to show it the following week, they said no, for now it stays there. . . They did not want simply to steal the scenario of Gilda, but to copy directly from the print itself.20Hūshang Kāvūsī [Review of Midnight Cry] in Hunar va Sīnimā 12 (5 Shahrivar, 1340 [August 27, 1961]). Reprinted in Jamāl Umīd, Tārīkh-i Sīnimā-yi Īrān 1289-1375 (Tehran: Intishārāt-i Rawzanah, 1374/1995), 334.

Even decades later, Khāchīkīyān appears to have been sensitive about the accusations of imitating Gilda and other crime films, claiming that his screenwriter had seen Gilda at that time, but he himself had not. But rather than taking a purely defensive posture in this response, he noted these affinities as evidence of his success as a stylist. “I take pride in the fact that the shots of my films are likened to others. . . My shot selection and camera angles were so successful that critics thought they must have been copied from other films.”21Haydarī, “Now My Hands Are Shaking…,” 41. The dispute was about who had a right to a close examination of the reissued print of Gilda: the Ciné Club or the Studio? One form of study was deemed appropriate and the other less so.

Figure 11: Khāchīkīyān behind the scenes of one of his films

The rivalry between Kāvūsī and Khāchīkīyān in the press occasionally took on an almost playful dimension that one hopes to find in a good public feud. In 1958, the investor Sa‛īd Nayvandī attempted to create a forum in which they might settle their grievances in a kind of filmmaking battle. They would each make a short film, which would be placed in competition and judged by a panel of experts. The press around this battle took on an almost comic dimension, with Khāchīkīyān immediately agreeing to the terms of the competition. In contrast, Kāvūsī treaded carefully and wrote a series of lengthy conditions to his participation. He first dismissed the competition and Khāchīkīyān’s status as an intellectual. “As we know in athletic competitions . . . the opponents usually do not face each other unless they are in the same weight class, and so it would be better for Mr. Khāchīkīyān to find a competitor at his level of taste and knowledge.”22“Sa‛īd Nayvandī barāyi tahīyyah-yi yak fīlm-i 5 daqīqah-yi az Khāchīkīyān va Duktur Kāvūsī d‛avat mikunad (Said Nayvandī invites Khāchīkīyān and Dr. Kāvūsī to each create a five-minute film)” Sitārah-yi Sīnimā 166 (1 Tīr, 1337 [June 22, 1958]): 5. Not wanting to be the one to run from the challenge, however, he accepted it provided that he would only be judged on the merits of 17 Days (not a new short, “I do not have this kind of time to waste”), and that the panel must be composed of film critics in France (not Iran).23“Sa‛īd Nayvandī,” 5. He agreed to serve as translator for this enterprise, highlighting his French language skills, but declined to pay the costs. When Khāchīkīyān casually agreed to accept the costs of transporting their prints to France and back, Kāvūsī decided that Khāchīkīyān should also pay for the costs of a new print of 17 Days from the camera negatives. This new condition finally made the competition impossible, and the matter was dropped.24“Dur-u-bar-i Istūdīyu-hā-yi Irān [Around the Iranian Studios]” Sitārah-yi Sīnimā 169 (23 Tīr 1337 [July 14, 1958]): 7. Kāvūsī suggested that the cold reception of his film would be redeemed by French film critics’ ability to distinguish true film noir from mere fīlmfārsī. The saga of this competition, observable over several issues of the publication, dramatizes the magazine’s familiar anxieties and contentious debates about creative origins. Both directors appeared to understand that managing an audience’s ability to see and understand creative work in a film is just as important as the creative choices made during the making of a film.

I close with the story of this feud because it highlights a tension unlike the ones that came later between art films and popular genre films.25See, for instance, Golbarg Rekabtalaei, “Alternative Cinema: A Cinematic Revolution Before The 1979 Revolution,” in Cinema Iranica (Encyclopaedia Iranica Foundation, 2024), retrieved September 11, 2024, https://cinema.iranicaonline.org/article/alternative-cinema-a-cinematic-revolution-before-the-1979-revolution/ This tension was between a purist mode and a collage mode: one leaning toward curation and festival institution building and the other toward an author-centered modernist approach to popular genre films. This contested area of expertise reshaped itself in the waves of the late 1960s and 1970s, but its configuration during this early period of films with festival ambitions helps to make sense of a media ecology that includes such a range of film styles. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, the crime thriller offered a way to consider new possibilities for recently established institutions of film publishing, distribution, and production in Iran. Even when there was little consensus, this stylized genre helped its proponents to imagine the film industry’s place in a kind of modernist cinema, defined not by global art films but rather by global golden ages.

And in fact, this very feud offers a clue to the provenance of the fragments of 17 Days that Ihsān Khushbakht and I worked to preserve in Paris in 2023. The assumption at the archive where the material is housed was that the print was at the school because it was standard for IDHEC/La Fémis graduates to deposit copies of their thesis films—but that can’t be the full story because Kāvūsī made the film after returning to Iran. The fragments that exist at the CNC are from a first-generation exhibition print with signs of having been projected, and it is on film stock imported from the UK and the US. The competition announcement and Kāvūsī’s description of how he would like the print to be evaluated abroad offers a plausible hypothesis for an intention behind the deposit now at the CNC. The hope may have been that future researchers and critics would discover this artifact of expertise and consider it in relation to other crime thrillers made during this period of world popularity. That is happening now. As preservation efforts continue, films like this one may indeed turn out to have been misunderstood.