Ana Lily Amirpour’s A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night (2014)

A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night (2014) is the debut feature of Iranian-American director Ana Lily Amirpour. Amirpour, whose family left Iran following the Revolution, was living in California at the time of filming after studying scriptwriting at the UCLA School of Theater, Film and Television. She had earlier made a short version of the film in 2011 and then begun a crowd-funding campaign to make a longer, full-length version. The film ended up being shot over some twenty-four days on a budget of only a little over $50,000. The film was first screened in the “Next” program of the 2014 Sundance Film Festival and was an immediate success. Amirpour won the Breakthrough Award at the Gotham Independent Film Awards in 2014, a distributor picked up the film, and it ended up taking over half a million dollars at the domestic box office alone. The initial reviews of the film praised it in the highest terms. The critic Nate von Zumwalt wrote soon after the end of the Festival of an “assured new female film-making voice.”1Nate Von Zumwalt, “A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night, Vampire Lovers, and Warpaint Close Out NEXT FEST,” Sundance Institute (blog), August 11, 2014, https://www.sundance.org/blogs/a-girl-walks-home-alone-at-night-vampire-lovers-and-warpaint-close-out-next-fest/ Sheila O’Malley at RogerEbert.com spoke of the way that the film “launches itself into a dreamspace of its own that has a unique power and pull,” and Peter Bradshaw of the Guardian remarked that Amirpour had “found her own funny, smart expression for teenage-bedroom loneliness, romantic isolation, and a kind of perpetual emotional exile.”2See: Sheila O’Malley, “A Girl Walks Home at Night.” RogerEbert.com, November 21, 2014, https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/a-girl-walks-home-alone-at-night-2014 Peter Bradshaw, “A Girl Walks Home Alone Review–Vampire in a Veil Stalks Iran.” The Guardian, May 22, 2015, https://www.theguardian.com/film/2015/may/21/a-girl-walks-home-alone-at-night-review In subsequent years the reputation of the film has only continued to grow, with any number of academic articles, chapters in books on such things as horror and feminism, and even an entire 2021 monograph by Iranian Studies scholar Farshid Kazemi devoted to the film.3Farshid Kazemi, A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2021). Today it is frequently spoken of as a “contemporary classic” and one of the most important examples of Iranian feminist cinema, and if this is not enough, commentators often point out that the film rates some 95% on the Rotten Tomatoes film review website.4As of 24 April 2024, the website’s review-aggregation or Tomatometer lists the film as “Fresh” at 96%. See: Rotten Tomatoes, “A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night,” April 24, 2024, https://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/a_girl_walks_home_alone_at_night

Figure 1: A still from Dukhtarī dar shab tanhā bi khānah mīravad (A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night, 2014). Ana Lily Amirpour, accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=js2R8b6_giY (00:00:41)

A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night is a vampire film. Set in an anonymous town in Iran referred to by its characters as Bad City (Shahr-i Bād)—in fact, the film was shot in the town of Taft in Southern California—it is the story of a young woman, known simply as Girl, whom we see kill and suck the blood of three men. The first is Sa‛īd, a pimp and drug dealer, who early on in the film takes Girl back to his house to have sex with her, but instead Girl sprouts fangs, bites off his finger, and kills him by piercing his neck. We then see in the middle of the film—from a distance and in a much less intimate way—Girl kill and drink the blood of a sleeping street person. Finally, towards the end of the film, we again see in a more detailed and confronting manner Girl kill Husayn Ārash, the father of the other main character in the film, the young man Ārash.

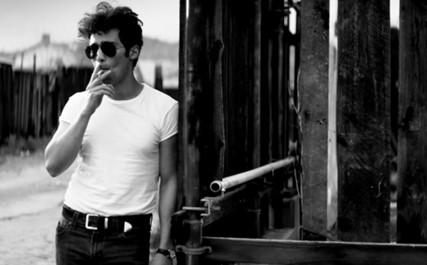

Figure 2: A still from Dukhtarī dar shab tanhā bi khānah mīravad (A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night, 2014). Ana Lily Amirpour, accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=js2R8b6_giY (00:04:20)

Notably, the audience witnesses both Sa‛īd and Hossein mistreat women before Girl kills them. Sa‛īd cheats one of his sex workers, ‛Attī, refusing to give her the money she has earned, and then extorts sex from her in the front of his car. Hossein, a drug addict, has previously been observed smashing up his bedroom, throwing a photo of his wife and Ārash’s mother to the floor, and then making ‛Attī dance for him, forcing drugs upon her and then lying down on a bed next to her after taking drugs himself. As these events play out, we see Girl and Ārash gradually fall in love after they first meet at a fancy costume party at which Ārash dresses up as Dracula. At the end of the film, after Girl kills his father—eventually Ārash will realize it was her—they leave Bad City in Ārash’s car, repossessed from Sa‛īd, driving off into the night and an uncertain future together.

Figure 3: A still from Dukhtarī dar shab tanhā bi khānah mīravad (A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night, 2014). Ana Lily Amirpour, accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=js2R8b6_giY (00:01:27)

There are many surprising and extraordinary things about A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night for both Iranian and Western audiences. For Iranian audiences, there is the obvious “Americanism” of the look of a film notionally set in Iran.5Joanna Mansbridge writes: “The film itself is an American film disguised as an Iranian film.” See: Joanna Mansbridge, “Law of Extraction: Transcultural Environments, Uncanny Subjects, and the ‘Unresolved Question of Pleasure’ in Ana Lily Amirpour’s A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night (2014),” The Journal of Popular Culture 54, no. 4 (August 2021): 813. Ārash resembles James Dean in his sunglasses and white T-shirt, and Girl has short clipped hair, a striped T-shirt, and black pumpernickel ankle boots. The Persian Farsi dialogue apparently reads as though filtered through the linguistic conventions of English. The soundtrack features a number of songs by Western rock bands and Girl’s bedroom walls are covered with posters of such 1980s pop-cultural icons as Madonna, the Bee Gees, and Michael Jackson, which were specially fabricated for the film.

Figure 4: A still from Dukhtarī dar shab tanhā bi khānah mīravad (A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night, 2014). Ana Lily Amirpour, accessed via https://www.cinemaldito.com/tag/a-girl-walks-home-alone-at-night/

But perhaps most notably and provocatively, there is the whole question of the empowering of women and the depiction of their sexuality in the film, and whether Girl’s killing of bad men is to be seen as an act of “feminist” revenge. Kazemi notes in his book that A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night received overwhelmingly negative reviews upon its release in Iran and was soon after banned, and goes on to argue that this was because the film upset religious sensibilities in the country.6Farshid Kazami, A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2021), 28-29. However, almost as a complement to this, we could equally say that the film also offends Western sensibilities, but this time because it overturns Western preconceptions about Iranian culture. There is much commentary, for example, on the way that the film features a queer character—the scarf- and lipstick-wearing Rockabilly, who operates as something of an outside observer throughout the film and whose gender is hard to determine—and on the empowerment of a chador-wearing female vampire who has been given the life-or-death ability to judge men in an apparently masculinist, Islam-dominated Iran.7Shadee Abdi and Bernadette Marie Calafell, “Queer Utopias and a (Feminist) Iranian Vampire: A Critical Analysis of Resistive Monstrosity in A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night.” Critical Studies in Media Communication 34, no. 4 (2017): 363-364. Also note that a chador, commonly worn by Muslim women, is an item of clothing derived from wrapping a large piece of cloth around the head and body, leaving only the face exposed.

The other aspect of the film that surprises and perhaps discomforts Western critics is the thorough immersion of A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night in long histories of Western culture. First of all, there is Amirpour’s desire to make a film about a vampire, which takes us back at least to Bram Stocker’s 1897 novel Dracula. Stoker’s film was the inspiration for Tod Browning’s classic Hollywood film of the same name (1931), starring Bela Lugosi in one of the most iconic cinematic performances of all time, but was also inspiration for Friedrich Murnau’s Nosferatu (1922) and Carl Dreyer’s Vampyr (1932). And then there are the endless kitsch remakes such as Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein (1948), the English Hammer Horrors, arguably Werner Herzog’s 1979 version of Nosferatu, all the way up to Tomas Alfredson’s Let the Right One In (2008).

Figure 5: A still from Dukhtarī dar shab tanhā bi khānah mīravad (A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night, 2014). Ana Lily Amirpour, accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=js2R8b6_giY (00:04:57)

Second, there are the other genres of Hollywood film that A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night clearly plays on. As previously suggested, the opening of the film with its English-language credits and the entrance of the handsome young actor Ārash Marandī with T-shirt and sunglasses walking down an empty main street with oil jacks pumping in the background is much like James Dean in a film like Giant (1956) or Rebel without a Cause (1955). Further, the idea of a justice-dispensing vigilante meting out punishment to bad men—even if she happens to be a female Iranian vampire—as much as anything draws on the conventions of Westerns, whether it be the Hollywood version by John Ford or the Italian spaghetti version by Sergio Leone.

Figure 6: A still from Dukhtarī dar shab tanhā bi khānah mīravad (A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night, 2014). Ana Lily Amirpour, accessed via https://www.pinterest.com/pin/545076361129979200/

Finally, and perhaps less obviously, such commentators as Barbara Creed and Lindsey Decker want to see the film as part of a feminine new wave horror film genre.8See for instance: Barbara Creed, “5. Vampires, Feminism and Ethnicity: A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night.” In Return of the Monstrous-Feminine: Feminist New Wave Cinema (New York: Routledge, 2022); and Lindsey Decker, “The Transnational Gaze in A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night.” In Women Make Horror: Filmmaking, Feminism, Genre, ed. Alison Peirse (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2020), 170-82. So too others both want to see it as a continuation of the Iranian New Wave and such directors as Ja‛far Panāhī and Husayn Shahābī, and view the film as marking the arrival of a new Iranian feminist cinema alongside such artists and directors as Shirin Neshat and Marjane Satrapi. And still other commentators, like Shadee Abdi, Bernadette Calafell, and Miriam Borham-Puyal, even see the film as part of a whole “queer” cinema movement due not only to such characters as the cross-dressing Rockabilly, but as well the androgynous haircut sporting, and T-shirt and ankle boots wearing actress Sheila Vand who plays the, one now realizes, ironically named Girl; the almost feminine beauty of the actor Ārash who plays her lover; and the very different, and undoubtedly non-conformist, love that develops between them, which is, after all, between a human and a vampire.9See for instance: Miriam Borham-Puyal, “2. Female Vampires on the Threshold of Time, Space and Gender,” In Contemporary Rewritings of Liminal Women: Echoes of the Past (New York: Routledge, 2020). For another example of the “queerness” of vampires, and Stoker’s Dracula in particular, see the recent edition of his book with a new Introduction by Silvia Moreno-Garcia and with a Forward by Alexander Chee: Bram Stoker, Dracula (Brooklyn, NY: Restless Books, 2023). Also see Chee’s related article concerning Stoker’s own alleged queerness: Alexander Chee, “When Horror is the Truth-Teller,” Guernica, October 2, 2023, https://www.guernicamag.com/when-horror-is-the-truth-teller/

The other principal way the film has been read is as an expression or even an allegory of Amirpour’s own situation as a diasporic Iranian. In interviews, Amirpour often speaks of the way that, despite moving from Iran when she was a child, much of the history and customs of the country remain with her through her family.10Amirpour says in an interview: “It’s a weird thing about Iranian culture. We’re one of those cultures like Italian or Jewish, we have very strong families, aggressively imposing families, in an awesome way . . . So I always had my Iranian-ness in that way, my grand-mother and mother and my aunt and everybody, and the dinners and the noises and everything.” Cited in Amanda Howell and Lucy Baker, “7. A Badass in Bad City: The Interstitial Artist and Monstrous Self-Fashioning in A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night.” In Monstrous Possibilities: The Female Monster in 21st Century Screen Horror (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2022), 121. She also speaks about the uncanny aspect of trying on a chador herself in America and wearing it when she visited Iran, insofar as it was at once strange and familiar. As it turns out, the chador was key for Amirpour in explaining her original inspiration for the film; it reminded her, of all things, of a vampire’s black cloak. She further recalls, while making a short film at UCLA, seeing an extra walking through the set wearing a chador and then asking to try it on: “Looking at herself in the mirror, she felt like a bat. She immediately thought ‘Iranian vampire’ and wondered why no one else had thought of it before.”11Kaleem Aftab, “Ana Lily Amirpour Has Created a Completely New Film Genre – The Iranian Vampire Western,” Independent, May 20, 2015, https://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/films/features/ana-lily-amirpour-has-created-a-completely-new-film-genre-the-iranian-vampire-western-10265538.html And all of this hybridity or in-betweenness, this belonging at once to two cultures or states of being, is absolutely to be seen in the character Girl in the film. Girl can very much be understood as Amirpour’s stand-in: at the same time human and vampire, kind and a killer, dead and alive (and in the backstory Amirpour sketched for the character, she was born in a Persian town in 1880, became a vampire in 1899, and it seems died in 1979). In all of this again, A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night can be seen as a signal example of what has been called a “post-colonial”—and is today called an “accented” or “transnational”—cinema.12For an essay on the “hybrid” nature of the film, see: Hoda Sabrang, “Shattered Identity of Immigrant Artist and Creation of Art in a Hybridized Space: The Case Study of A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night,” CINEJ Cinema Journal 8, no. 2 (December 2020): 45-61; On the film as an example of “accented” cinema, see: Zahra Khosroshahi, “Vampires, Jinn, and the Magical in Iranian Horror Films,” Frames Cinema Journal 16 (Winter 2019). http://framescinemajournal.com/article/vampires-jinn-and-the-magical-in-iranian-horror-films/ And on “accented” cinema in general, see: Hamid Naficy, An Accented Cinema: Exilic and Diasporic Film-Making (New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2001). The situation of Amirpour as an unnoticed expatriate Iranian in America is altogether given allegorical expression in a living dead female vampire wandering a generic and characterless street in Iran in a chador on a dark and foreboding night.

Figure 7: A still from Dukhtarī dar shab tanhā bi khānah mīravad (A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night, 2014). Ana Lily Amirpour, accessed via https://www.vox.com/2016/10/25/13175536/foreign-horror-films-streaming-netflix-amazon-shudder

But perhaps the film is a brilliant allegory of something else as well. For, beyond all of these particular ways of reading the film, there is the general question of why so much has been written about it, why it appears such an irresistible topic for critics and commentators, both academic and popular (e.g., if one goes online, one will find dozens of amateur attempts to explain the film, pointing out both the intricacies of its plot and the literary and philosophical sources it draws upon). What is it about this first-time, low-budget, black and white horror film that keeps people wanting to engage with it? How it is that it can be seen to be speaking of such a wide range of issues a contemporary audience is interested in (e.g., the liberation of women in Iran, the Americanization of Iranian culture, the misunderstanding of Iranian culture by the West, the situation of diasporic Iranians, post- or transnational cinema)?

Might we say that the embrace between Girl and Ārash we see towards the end of the film—after she falls in love with him while he is dressed up as Dracula at the party and after he realizes that she is an actual vampire—is like the one that the film and its audience find themselves in at the end of A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night? That each is at once the succubus of and host for the other? Critics use the film as a reflection of their concerns, drink its blood, extract its benefits like a vampire with humans or indeed like those oil jacks we see pumping away throughout the film. But at the same time the film also benefits from us, sucking out and extracting our good ideas and claiming them for itself (and it is revealing that the first time we see Girl in the film it is in a mirror, as opposed to the usual conventions of vampire films).13That is to say, the film claims it is against the logic of “extraction” but it is fair to say that it is also part of it. See: Mansbridge, “Law of Extraction: Transcultural Environments, Uncanny Subjects, and the ‘Unresolved Question of Pleasure’ in Ana Lily Amirpour’s A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night (2014),” 816. To my mind, one of the things A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night is both about and plays out is how “great” works of art are about their future reception, at once taking this reception into account and making it their subject. Like some kind of “mash-up” or “patchwork monster,” a great work of art can appear to embody all kinds of divergent and even opposing interpretations and “reconcile” them or at least put them together in the same place.14Howell and Baker, “7. A Badass in Bad City: The Interstitial Artist and Monstrous Self-Fashioning in A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night,” 120 and 123.

Figure 8: A still from Dukhtarī dar shab tanhā bi khānah mīravad (A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night, 2014). Ana Lily Amirpour, accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=js2R8b6_giY (00:09:51)

A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night certainly does this. It is both a critique of certain aspects of Islamic culture and of the West’s misunderstanding of Islam, about Islam’s repression of women and its empowerment of them, about Girl’s seduction and domination of Ārash and her opening up and becoming vulnerable to him. It is all of these things at the same time and that is why it will live on forever, undead. It is at once the vampire that sucks our blood and it is us. Or to put it another way, we are the vampire that we feed. This is Amirpour in an interview speaking of what, for her, is the message of the film:

In this world with all these people and all these countries and all these places, we come up with systems on how to exist as people, the clothes people wear, the bumper stickers on cars saying ‘This is who I am’, ‘This is what I believe in’. But with all of us, if you start peeling it back like an onion, there’s weird, weirdo, weird shit inside all of us.15Virginie Selavy, “A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night: Interview with Ana Lily Amirpour,” Electric Sheep, May 19, 2015, http://www.electricsheepmagazine.co.uk/2015/05/19/a-girl-walks-home-alone-at-night-interview-with-ana-lily-amirpour/

A female/feminist Iranian vampire is this “weird shit” inside all of us. She is us, and when we watch A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night we are both the killer and the ones she kills.

Figure 9: A still from Dukhtarī dar shab tanhā bi khānah mīravad (A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night, 2014). Ana Lily Amirpour, accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=js2R8b6_giY (00:08:03)

Cite this article

This article explores Ana Lily Amirpour’s A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night as a transnational feminist vampire film. Set in the fictional Iranian town of Bad City, the film critiques gender dynamics while blending Iranian cultural elements with Western genre conventions. By analyzing its feminist symbolism, hybrid identity, and commentary on diaspora experiences, the article positions the film as a groundbreaking work that challenges cinematic and cultural norms.