Creating the image of “Decent Woman” in Iranian Films (1979-1989)

Figure 1: A screenshot from the film Bugzār Zindagī Kunam (Let Me Live), directed by Shāpūr Qarīb, 1986.

Toward Shaping the Image of Woman Amid the Turmoil of the Revolution

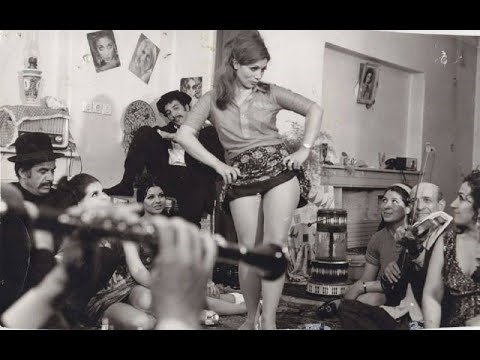

In the thick of the Revolution, 180 theaters from the existing 436, or 451 based on another estimation, were burned down.1Humā Jāvdānī, Sāl shumār-i tārīkh-i sīnimā-yi Īrān (Tīr 1279 – Shahrīvar 1379) [Chronology of Iranian Cinema History (June 1900 – August 2000)] (Tehrān: Qatrah, 2002), 139; Saeed Zeydabadi-Nejad, The Politics of Iranian Cinema: Film and Society in the Islamic Republic (London: Routledge, 2010), 35; Hamid Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema, Volume 3: The Islamicate Period, 1978–1984 (Durham: Duke University Press, 2012), 21–22. More than anything else, the hostilities had formed around the roles of actresses in commercial cinema in the second Pahlavi period, known as Fīlm-Fārsī. In these films, several female stars appeared in roles that were perceived as seductive by audiences, primarily men, with the camera often focusing in a voyeuristic manner on the actresses’ bodies. These actresses’ fame was primarily based on their sexual appeal rather than on other criteria. In this way, the creation of a unified entertainment industry in Iran was facilitated and films became intertwined with popular culture. A number of other actresses were professional singers and dancers who performed for audiences in cafés, bars, and nightclubs and helped to boost the financial success of the films. Despite the social taboos of that period, some of these actresses successfully entered the burgeoning media of radio and television, gaining considerable popularity.2Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema, 207–13.

Figure 2: A screenshot from the film Raqqāsah-yi Shahr (The Dancer of the City), directed by Shāpūr Qarīb, 1970.

Although it was common to censor scenes that were considered “immoral” even before the Revolution,3Censorship had been multifaceted, involving state, religious, commercial, and internal self-censorship. These different forms collectively shaped the film industry, often applied inconsistently and locally. Some films, like Khāchīkiyān’s Qāsid-i Bihisht (Messenger from Paradise, 1958), faced multiple censorship demands despite already having an official exhibition permit. This included removing nudity, dialogues, and scenes that different groups found objectionable, leading to significant delays and financial strain for producers. See: Hamid Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema, Volume 2: The Industrializing Years, 1941–1978 (Durham: Duke University Press, 2011), 259–60. this censorship reached a different level after it. Cinema, along with other Western phenomena such as theater and dancing, was looked at with suspicion and its revision was considered inevitable. Thus, the words of the returned-from-exile leader of the revolution about the reprehensibility of the cinema of the Pahlavi period became a foundation for the later changes: “Why was it necessary to make the cinema a center of vice? We are not opposed to the cinema, to radio, or to television; what we oppose is vice and the use of the media to keep our young people in a state of backwardness and dissipate their energies…. The cinema is a modern invention that ought to be used for the sake of educating the people.”4Ruhollah Khumaynī, Islam and Revolution: Writings and Declarations of Imam Khomeini, trans. Hamid Algar. (Berkeley: Mizan Press, 1981), 258.

Therefore, one of the main concerns—perhaps the most significant—was the need to formulate a new image of women. This image was one of the cornerstones of the new government. Even before the Revolution, the women’s hijab had already been declared a symbol against the West and its manifestations. During the demonstrations leading up to the Revolution, the hijab became a symbol of resistance against a government believed to be promoting the westernization of the country while undermining religious values. For some women, even those who did not usually wear the hijab, donning the chador became a means of stabilizing their cultural and religious identity. Hijab was not just a piece of clothing, but a manifesto against the cultural invasion of the West and a testament to the desire to return to native roots. These ideas not only influenced the traditional Shiite women, but also attracted the attention of educated women through the writings of ‛Alī Sharī‛atī.5Anne H. Betteridge, “To Veil or Not to Veil: A Matter of Protest or Policy,” in Women and Revolution in Iran, ed. Guity Nashat Becker (Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press, 1983), 119–24. Therefore, the roots of this transformation can be found both in religious texts and in Shiite groups that sought political power, as well as in the anti-imperialist ideas of thinkers like Frantz Fanon (1925–1961), the French theorist of the mid-20th century, which were highly influential at the time. In his essay, “Algeria Unveiled,” which was published before the Islamic Revolution in A Dying Colonialism, Fanon suggested that a woman’s hijab is key to understanding the symbolic hegemony of colonialism and the ways to resist it. It was assumed that while colonial powers sought to dominate cultural symbols like the hijab, resistance could create new meanings for the hijab—or its absence—and, in a symbolic battle against the colonizer, fight this hegemony on the battleground of the veiled woman’s body.6Frantz Fanon, “Algeria Unveiled,” in A Dying Colonialism, Trans. Haakon Chevalier, (New York: Grove Press, 1959): 36–37.

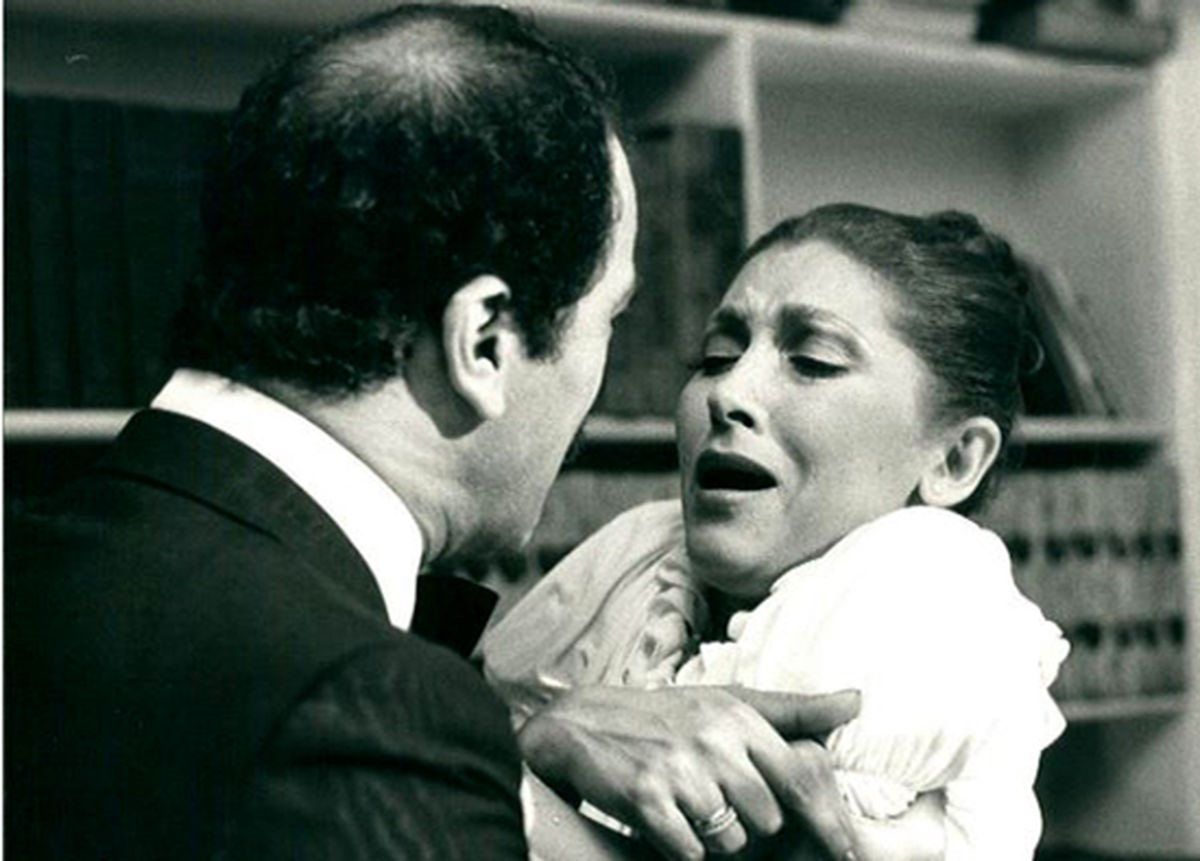

Figure 3: A screenshot from the film Dāyarah-i Mīnā (The Cycle), directed by Dāryūsh Mihrjū’ī, 1978.

In consequence, a change in the image of women, which was created in the Pahlavi period, was thought to be inevitable because the revolutionary discourse defined itself as opposed to all the ideals and norms of the previous regime and aimed at cleaning and reforming everything that was pictured before. These changes were not only necessary for establishing a new political and economic foundation and gaining popular legitimacy through new mechanisms, but also instrumental in the recreation of culture, daily life, and intellectual life, as well as in cleansing it of the ‘contamination’ of Western elements.

Increasing attempts were made around the formation of the image of the revolutionary woman from the very beginning of the Revolution.7After the Revolution, one of the first laws to be annulled was the law supporting families, which had been enacted in 1967. It limited the rights of men for polygamy and divorce upon request and eventually preserved the rights of women for divorce and taking custody of their children. In 1973, these reforms were expanded and strengthened. It was the annulment of this law that sparked protests on Women’s Day. In cinema, too, reflecting society, there was no doubt about the need to change the way women were presented; however, due to the initial chaos, it took a few years to institutionalize this image and formulate detailed regulations on what this image should be and how it should be presented.

A few years after the Revolution, the society was engulfed in chaos. The expansion of parallel powers alongside the established government made it impossible to maintain order.8Among them were revolutionary committees, revolutionary courts of law, the Revolutionary Guard, and many parties and political movements that supported various radical policies. Last but not least, the citizens had military bases, police stations, palaces and ministries under their control. See, Shaul Bakhash, The Reign of the Ayatollahs: Iran and the Islamic Revolution, (New York: Basic Books, 1984), 55–56. In such circumstances, cinema also was in a period of chaos. The purging process began as part of the changes in cinema after the Revolution. Movie theaters were periodically closed and reopened; some were repurposed, while others, like the theater in Rūdakī Hall, were cleansed of previous “immoralities” through religious rituals such as ghusl (a ritual purification in Islam).9Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema, 22. It was unclear which ministry was responsible for handling cinema affairs; therefore, it is not surprising that there was no agreement on how to portray women in films in this chaotic situation. The changes seemed inevitable, but no one knew how necessary these changes were and who was responsible for formulating and implementing them.

This confusion created a constant struggle between film producers, cinema owners and the government. The producers made small changes to the films made before the Revolution in order to escape censorship. Sometimes, only the name of the film was changed, while the content remained the same.10“Sinimā dar vīdīyu: Rāhnamā-yi film-hā-yi mujāz-i vīdīyu (Cinema in Video: A Guide to Permitted Films on Video in Iran),” Māh-nāmah-yi Fīlm 1 (June 1982): 98. Another solution was to cut some scenes that were deemed immoral and to replace them with scenes that were shot anew. Cinema owners also tried to control the ‘damage’ by voluntarily omitting sexual relations, behaviors, and clothing that went against the new ideology. A common practice was to use marker pens on the frames and posters of films to cover the exposed parts of women’s bodies with skirts, shirts, or scarves. However, the government was dissatisfied with these superficial changes and made it mandatory to obtain a movie screening permit. As a result, all the films produced in the previous period, along with imported films, were revised. Many films, not only commercial ones but also those belonging to the New Wave movement or the intellectual cinema of the Pahlavi period, such as Muhammad Rizā Aslānī’s Shatranj-i bād (The Chess of the Wind, 1976), were banned permanently, while others had to endure censorship to become compatible with Islamic values.

Figure 4: A screenshot from the film Shatranj-i bād (Chess of the Wind), directed by Muhammad Rizā Aslānī, 1976.

Radical conservative groups went even further and demanded that the government prevent well-known filmmakers and actors from the pre-revolutionary commercial cinema from working. Even when these filmmakers and actors received official screening permits for their films, their past artistic activities sparked protests. For instance, despite the initial success of Īraj Qādirī’s Barzakhī-hā (The Imperilled, 1980), huge protests erupted against the casting of film stars from the Pahlavi period to play the roles of epic Islamic heroes,11An unknown writer of Kayhān wrote: “Actors whose tasks in the past were to soil the honor of the society are now, with the same appearances and the same trite techniques, playing the roles of revolutionary and Islamic figures, even the role of Imam [Khumaynī]. See: Īraj Qādirī, “Dūzakh-i Ibtiẕāl dar ‘Barzakhī-hā’ (The inferno of Vulgarity in ‘The Imperilled’),” Kayhān (May 30, 1982): 13. which eventually led to the banning of the film. Qādirī’s look toward women in his other film, Dādā (1982), also made him the target of harsh criticism; for instance, an article in Film Monthly (Māh-nāmah-yi Fīlm) read: “now that Qādirī cannot picture women naked, he cannot hide from view the essence of women that he has in mind. From the very beginning, the new bride of Dādā gets raped, which motivates Dādā to take action. In other words, once again, it is an act of dishonor that sets the wheels turning.”12Īraj Qādirī, “Dādā,” Māh-nāmah-yi Fīlm 4 (1983): 48.

In such a volatile situation, filmmakers were also confused in their response to this trend. Many of them omitted the depiction of women from their films altogether, such as Farīburz Sālih in Safīr (Ambassador, 1982) and Muhsin Makhmalbāf in Isti’āzah (Fleeing from Evil to God, 1983). By avoiding stories that needed the participation of women, they sought to appease the new sensitivities. The director of Ambassador opined that “in this confused and chaotic situation” for filmmaking, it is better to “close down cinemas for a while so that the officials and experts could sit down… and prepare the practical guidelines” clearly. He claimed that there actually were some (women) actresses in his film, “but the camera angle was in a way that they were not in the frame.”13“Musāhabah bā Farīburz Ṣālih, Kārgardān-i Fīlm-i Safīr (Interview with Farīburz Sālih, Director of Ambassador),” Māh-nāmah-yi Fīlm 4 (July 1983): 7–12. However, there was still a minority of filmmakers who did not turn away from women. The roles women played clearly changed, though, and there was no more dancing or singing in the films. No agreement had yet been reached regarding the hijab. This is evident in films that addressed the political situation before the Revolution, such as Khusraw Sīnā’ī’s Zindah bād! (Long Live! 1980), Mas‛ūd Kīmiyā’ī’s Khaṭ-i Qirmiz (Red Line, 1982) and Ghulām-‛Alī ‛Irfān’s Āqāy-i Hīrūglīf (Mr. Hieroglyph, 1980), which revolves around the life of a guerilla girl and narrates the story of the armed struggle of leftist movements in 1970s Iran. In the mythological and historical works of Bahrām Bayzā’ī, too, such as Charīkah-yi Tārā (Ballad of Tārā, 1980) and Marg-i Yazdgird (Death of Yazdgerd, 1982), the image of the modest and reticent woman epitomizing the decent woman after the Revolution was not completely formulated yet. Many of these films were made without any official permit and were never screened, or, if they were, they were taken down after a short run.

Figure 5: A screenshot from the film Khaṭ-i Qirmiz (The Red Line), directed by Mas‛ūd Kīmiyā’ī, 1982.

These rather spontaneous and disorganized efforts were approved by neither the new government officials nor by cinema owners and filmmakers, who demanded the organic and full-fledged intervention of the government in the cinema industry.14In December 1980, in a letter to the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance, the Society of Cinema owners criticized the government for its inattention to cinema. It was also announced that, with the help of the government, the private sector would be able to harmonize the cinema industry with “the revolution and the people” in five years. Filmmakers had similar concerns as well. In 1981, they wrote a letter to ‘the people and the government,’ claiming that even two years after ‘the holy and anti-imperialist revolution of the people of Iran,’ the revolution had not yet taken root in the cinema industry and that ‘a kind of dependence’ had emerged there, similar to the dependence of the previous period. The writers asked the government to implement the new law “organically and comprehensively”. See: Hamid Naficy, “Islamizing Film Culture in Iran: A Post-Khatami Update,” in The New Iranian Cinema: Politics, Representation and Identity, ed. Richard Tapper (London: I.B. Tauris, 2002), 35. Therefore, in February 1983, the government passed a set of regulations about the screening of films and videos and assigned its implementation to the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance.15“Niẓārat bar namāyish-i fīlm va islāyd va vīdīy’ū va sudūr-i parvānah namāyish ān-hā,” Markaz-i Pazhūhish-hā-yi Majlis, 23/02/1983, accessed on 10/11/2024, https://rc.majlis.ir/fa/law/print_version/106928. These regulations stipulated that all films and videos screened publicly must have an official screening permit. Additionally, a supervisory committee was made responsible for regulating the presence of women in a way that does not contradict the “human dignity” of women.16This committee consisted of one cleric familiar with artistic fields, three individuals familiar with political, social and Islamic issues as well as film and cinema, and one expert in the field of domestic and foreign film and cinema. This committee should determine and provide the Islamic regulations to be applied in all films, whether Iranian or foreign.

The aim was to represent women as chaste individuals who play essential roles in society and in raising pious and responsible children. Additionally, women were not to be used for stimulating sexual desires. These general and ambiguous guidelines had a deep effect on the presentation of women in cinema.17Naficy, “Islamizing Film Culture in Iran,” 36. The hijab was gradually made compulsory in society, and a law was passed in 1983 regarding women’s clothing.18Article 102 of the Penal Code was about this issue, which was later added as a note to article 141 of the Islamic Penal Code approved in 1996. According to this law, any individual who practically pretends to be doing something illegal in plain sight, public places, and thoroughfares, in addition to being punished for her/his crime, will be sentenced to imprisonment from 10 days to 2 months or a fine of 74 lashes; and if the individual commits a deed that is not punishable itself but violates public morals, he/she is only sentenced to imprisonment from 10 days to 2 months or 74 lashes. The note also says: Women who appear in thoroughfares and in public without Islamic hijab will be sentenced to imprisonment from 10 days to 2 months or a fine of 50 thousand to 500 thousand rials. The pressures, however, had increased even before these laws were approved. Cinema theaters were among the first public places that, since 1981, were forced to prevent women without Islamic hijab from entering.19Jāvdānī, Sāl shumār-i tārīkh-i sīnimā-yi Īrān, 153. Consequently, the rules of “modesty” dominated the actresses’ behavior and affected their attire, their speech, the narrative structure of the film, and also the mise-en-scène and the style of cinematography.

In this research, we will examine how these regulations were institutionalized in films made between 1979 and 1990, which contributed to the construction of the new image of the “decent woman.” This goal will be achieved on two levels: first, we will explore the privative aspect of this image, which aim to diminish women’s sexual drive ⸺that is, the suppression of their desires in order to give cinematic form to the limitations gradually defined by revolutionary ideology. Next, we will explore its affirmative aspect, which seeks to create an otherworldly image of women, formed at an abstract level, and can be explained through the concept of ‘Eternal Feminine.’ These two aspects are examined successively here for the sake of discussion, although in reality, both of these aspects are intertwined, proceed in parallel, and have no temporal precedence. In order to have a more inclusive research sample, we aim to discuss all types of films, including those among the influential works that are considered to have high cinematic value, such as Ballad of Tārā and Dāryūsh Farhang’s Tilism (The Spell, 1986), and popular and commercial films such as Shāpūr Qarīb’s Bugẕār Zindagī Kunam (Let Me Live, 1986). Such a sample can cover a significant portion of the productions, although it is impossible to be fully inclusive, as some films fall outside this pattern. For instance, from the mid-1980s onward, we see examples of different presentations of women in films such as Muhammad ‛Alī Najafī’s Guzarash-i yak qatl (A Report on a Murder, 1986), where a woman is shown as a member of the central committee of the Tūdah Party and plays a central role in the story. Some of these examples are discussed in the final section of this article.

Figure 6: A screenshot from the film Guzarash-i yak qatl (A Report on a Murder), directed by Muhammad-‛Alī Najafī, 1986.

It is also worth noting that Hamid Naficy has made significant contributions to the literature on the changes in the role of women in post-revolutionary cinema through his articles and books, which serve as the primary sources for this article. In his article, “Women and the ‘Problematic of Women’ in the Iranian Post-Revolutionary Cinema,” he argues that after the Revolution, the emphasis shifted to the radical intertwining of women with their sexuality.20Hamid Naficy, “Women and the ‘Problematic of Women’ in the Iranian Post-Revolutionary Cinema,” Nimeh-ye digar 14 (1991), 122–69. This shows that femininity is only defined by sexuality. This is not true about men. Therefore, a woman is attributed with having a powerful influence on stimulating man’s desires. This leads to the development of a supervisory system and a change in the portrayal of women on screen. In “Veiled Visions/Powerful Presences: Women in Postrevolutionary Iranian Cinema,” Naficy examines the changes and expansion of women’s roles in Iranian cinema after the revolution, both in front of the camera and behind the scenes.21Hamid Naficy, “Veiled Visions/Powerful Presences: Women in Postrevolutionary Iranian Cinema,” in Life and Art: The New Iranian Cinema, ed. Sheila Whitaker (London: National Film Theatre, 1999), 44-65. It also discusses how the principles of modesty and sexual segregation shaped the aesthetics of wearing and not wearing the hijab, ultimately influencing the representation of women and the theme of love in Iranian cinema. Also, in “Veiled Voice and Vision in Iranian Cinema: The Evolution of Rakhshān Banī’i‛timād’s Films,”22Hamid Naficy, “Veiled Voice and Vision in Iranian Cinema: The Evolution of Rakhshan Banietemad’s Films,” Social Research 67, No. 2, (2000): 559–576. Naficy outlines the changes in the portrayal of women in post-revolutionary Iranian cinema in three stages: initial absence, limited roles in the background, and finally, powerful main roles, both as actors and directors. He argues that the rules of modesty have played a significant role in driving these changes. Supported by the rise of prominent women filmmakers like Rakhshān Banī’i‛timād, these rules contributed to the creation of a unique cinematic image.

The formation of a Criteria for the Image of Woman: Desexualization and the Principle of Eternal Feminine

In the early years following the Revolution, women were seldom instrumental in the stories and were presented on the screen in particular forms. Sometimes, we deal with what Hamid Naficy calls “absent presence,” which means all the aspects of the woman are not shown in the film: sometimes there is her voice, but there is no image of her; sometimes the image is there, but the voice is not; and sometimes neither the image nor the voice is there, yet her presence is still felt.23Naficy, “Women and the ‘Problematic of Women’,” 141-142. We hear the voice of the mother for a few moments in Ibrāhīm Furūzish’s Kilīd (The Key, 1985), but we only see a distant and blurred shot of her from behind and a medium shot of her hands. After this scene, neither her image nor her voice appears in the film, but her absence influences the story.

And when the woman is present with both her image and voice, the rules of hijab and modesty are dominant over her clothes (long, loose, and dark), her behaviors and actions (demure and avoiding any bodily contact with the unrelated men) and her gaze (avoiding direct and long look). Therefore, we only see some faces whose bodies are wrapped in several layers of clothing, which are described by Hamid Dabashi as “body-less faces”; faces that deny their bodies and testify to the impossibility of femininity in post-revolutionary cinema. Dabashi believes that there is a striking inconsistency between these faces and the clichéd distortion that should characterize their bodies.24Hamid Dabashi, “Body‐less Faces: Mutilating Modernity and Abstracting Women in an ‘Islamic Cinema’,” Visual Anthropology 10, no. 2-4 (1998): 362.

According to the ever-expanding criteria for filmmaking, close-up shots of women’s faces or the exchange of lustful glances between a woman and a man were forbidden. Additionally, women were more often than not shown in long shots and (in) static roles in order to prevent the appearance of their body lines because, as the Islamic law decrees, a woman’s clothing should be in such a way as to “conceal the features and the beauties of her body.”25‛Alī Khāmanah-ī, Risālah-yi Āmūzishī (2): Ahkām-i Mu‛āmilāt (Educational Thesis (2): The Rules of Transaction) (Tehran: Fiqh-i Rūz, 2019), 369. It is only allowed to look at the face and hands of a woman, without any sexual pleasure, provided that these parts are without makeup or jewelry. In this discourse, the woman’s body, its reproductive potential, and its sexual appeal serve both as a symbol and a physical and tangible tool for organizing the world. Being a woman was the principal sign of unity and independence in a changing society and had to be “protected.” This symbology revealed itself in the tendency to limit women’s freedom in choosing their clothing and movements.

As a result, “both women and men were desexualized… Love and the physical expression of love (even between intimates) were absent.”26Naficy, “Veiled Visions/Powerful Presences,” 45. Meanwhile, even marriage was pictured as devoid of desire. Murtazā in ‛Alīrizā Dāvūdnizhād’s Bī-panāh (Exposed, 1986) is an officer who takes it upon himself to marry A‛zam, a lonely woman who has come to him for help. Murtazā doesn’t even know her name, but he is worried that if he doesn’t marry her, she will be “exposed.” After marriage, he assures her that he has taken the vow of marriage so that he could take care of her. There is no desire involved, and he will not approach her unless she wants him to. A‛zam also insists on wearing her chador in his house. After a while, it comes to light that A‛zam is a divorced woman, and, more importantly, a mother. Being a mother has created such a “holiness” for her that she should not be tainted by being touched. A “decent mother” is a woman who is sexually inactive. Well aware of the preference for being a mother over being a wife, Murtazā separates from her at the end so that she can go back to her husband, Ahmad, and raise her child, Rizā. He assures Ahmad that he has treated A‛zam, who is now addressed with her main role as “Rizā’s mother,”, as his “sister,” rather than as his wife.

Figure 7: A screenshot from the film Bī-panāh (Exposed), directed by ‛Alīrizā Dāvūdnizhād, 1987.

This treatment reminds us of the titles for women and men in Islamic leftist political parties. When encountered with the inevitable closeness of the two sexes, these parties used these titles as tools for keeping women away. In order to be separated from their sexual attractions, fighting women are addressed as “comrades” or “sisters” by their peers and are constantly reminded of the prohibition of having sexual relations with them. The imaginative walls of the private world can be extended to eternity. Away from the taboo of incest, a woman can magically turn into a “sister” and a “comrade” and get sexually out of reach. In this way, the imaginative borders replace the real borders.27Farzaneh Milani, Veils and Words: The emerging voices of Iranian women writers (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1992), 27.

The boundary between private and public space is erased. As strangers enter the private space and become ‘brothers,’ the private space of the house is transformed into a public space because of the presence of unrelated spectators. Consequently, women in these films are always covered and obedient, even when they are with their close relatives. Keeping hijab in the presence of intimate ones creates an unrealistic and distant space that presupposes the presence of an unrelated spectator. In this situation, not only does touching each other become a taboo, but also there is a change in the characters’ gaze at each other and the spectators’ gaze at the film because:

“An unveiled woman, like Medusa, should not be gazed at… In a veiled society, seeing, far from being considered a mere physiological process, takes on a socially determined, potentially dangerous, and highly charged meaning. Considered much more than windows to the soul safely concealed, eyes become subject to the strictest regulations for both men and women. Men’s eyes attain phallic power… Men’s forbidden act of seeing thus becomes a violation, a sin, a visual rape.”28Milani, Veils and Words, 24–25.

If women are supposed to cover their bodies, men are also supposed to cover their eyes. Therefore, the film is worried about the gaze of the male spectator. There are complications in the process of this gaze, which is implicated in the nature of the cinematic picture. The most obvious instance of the look in cinema is the one that originates with the spectator, whose gaze is directed at moving images on the screen. But the act of looking in cinema is more complex than this. Cinematic address may also, for example, direct looks toward the spectator. This is particularly clear in the shot/reverse shot structure: the viewing subject, in standing in for the look of a protagonist in the film, becomes the object of the fictional gaze of the other protagonist.29Annette Kuhn, Women’s Pictures: Feminism and Cinema, 2nd ed. (London: Verso, 1994), 56.

This structure of looking and looking back is used abundantly in the scene of arguments between the modest Farīdah and her husband, Manūchihr, in Let Me Live (Shāpūr Qarīb, 1986) about the failures in performing their assigned tasks as wife and husband, and mother and father, and the shrewdness of the women of the family (Figure 8). In a sense, these characters are aware not only of each other, but also of an unrelated man, the spectator of the film, who is required to obey the “rules of looking” just like the characters in the film.30Negar Mottahedeh, Displaced Allegories: Post-revolutionary Iranian Cinema (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2008), 8-9.

Figure 8: Shot/reverse shot of Farīdah and Manūchihr, from the film Bugzār Zindagī Kunam (Let Me Live), directed by Shāpūr Qarīb, 1986.

These rules prohibit men and women from looking lustfully at unrelated persons. Looking at women’s hair is forbidden for men; therefore, women are required to cover it. Looking at unrelated people, whether in person or through a picture (live or recorded, such as a photo), is not allowed if it is accompanied by sexual pleasure and lust. These rules created a certain kind of look, which is called “averted look” by Hamid Naficy: “to satisfy the rules of modesty, a situationist grammar of looking has evolved that ranges from direct gaze to what I have called the averted look. In this case, people avoid looking at others directly…. When meeting each other, they tend to look down or to look at the other’s face in an unfocused way so as to avoid definitive eye contact.”31Naficy, “Veiled Visions/Powerful Presences,” 56.

Nevertheless, every now and then, we encounter a close-up shot, a distinct face, a rather direct look, and a significant role in the story. In these cases, to desexualize women, it is necessary to distance oneself from the tangible facts of life and unique moments, moving toward abstraction, which relies on relinquishing the unique and special aspects of life. This situation can be best explained by the principle of Eternal Feminine. Simone de Beauvoir makes extensive and detailed references to literary works in order to explain what she calls Eternal Feminine, or “that vague and basic essence, femininity.”32Simone de Beauvoir, The Second Sex, trans. and ed. H. M. Parchley, (London: Jonathan Cape, 1956), 214. This myth takes different forms, like the holiness of the mother, the purity of the virgin, the fertility of the earth and the womb; however, in each and every one of these forms, the aim is to negate the individuality of women and to relegate them into the unattainable dreams.

Mythical, ghost-like, and unworldly women permeate the cinema of this period. The most remarkable example is Ballad of Tārā. Tārā is considered “the manifestation of mother earth…, the mythological image of woman that can belong to yesterday, today or tomorrow and always be a woman complete.”33Shahla Lahiji, Sīmā-yi Zan dar Āsār-i Bahrām Bayzā’ī (The Image of Woman in the Works of Bahrām Bayzā’ī) (Tehran: Rawshangarān, 1988), 49. Tārā, or the “mother earth”, falls in love only with an unworldly man; someone who is not bound by flesh and blood, but is an inhabitant of the realm of the dead; a man who cannot gently return to his own world because of his love for her. Tārā finally falls in love with him, reveals her body to him and welcomes him into her arms. Tārā intends to make life and blood flow in the veins of the man who has been living in another world for centuries. In order to come to life, the man asks for the lives of Tārā’s children. Tārā cannot forsake her children, so she gets ready to go with him to the world of the dead. Such a sacrifice breaks the man’s spell. He leaves the earth and returns to his world with both comfort and sorrow. In the real world, each woman manifests herself in different ways; however, each of the myths constructed about her claims to summarize her completely, as each one asserts its uniqueness. Therefore, Tārā “is considered to be a tale in praise of every manifestation of women” (Figure 9).34Lahiji, Sīmā-yi Zan, 49.

It is not only in this period that such an image of women is presented. In the pre-revolutionary Iranian cinema too, similar characterizations can be seen. For instance, Gharībah va Mah (The Stranger and the Fog, 1973), is one of the first steps by Bahrām Bayzā’ī to enter the world of myths. He starts using symbols (in here) that become more unified and understandable in his later films. The character of Āyat is considered a “fugitive from the world of death” who should “return to his home sooner or later”; and the character of Ra‛nā is “an allegory of life and rebirth against death and destruction.”35Lahiji, Sīmā-yi Zan, 43–46. This image of woman can be traced back to fictional literature and the ethereal woman in the first part of Sādiq Hidāyat’s Būf-i Kūr (The Blind Owl), where she is heavenly and her beauty is unrelated to the earth and its belongings. The perfect woman is pictured as follows: “She was not like ordinary people. Her beauty was not ordinary, too. She manifested herself to me like a vision in an intoxicated dream.” For the narrator, she is an inaccessible woman: “I never wanted to touch her. The invisible rays that radiated from our bodies and intertwined with each other were enough.”36Sādiq Hidāyat, Būf-i Kūr (Tehran: Chāpkhānah Sipihr, 1972), 9–10.

Nevertheless, in the post-revolutionary period, this type of characterization became more frequent and more diverse. In the film The Spell, we learn that many years ago, the future lady of a mansion disappeared on her wedding night after entering the mirror salon and since then, no one has ever heard from her. Then, it is revealed that she is imprisoned by the lord’s butler in a cellar, surrounded by chains and gears. For the past five years, everyone thought the lady of the house had escaped; however, she is still wearing her wedding gown, and her hair and face match the color of her dress in the dark cellar, making her look like a ghost. Her memories are also frozen, like her dress on the wedding night, and she has become immortal, existing outside of history and time, as if that night has never ended (Figure 10).

Figure 9 (Left): Tārā calls the other-worldly man to herself. A screenshot from the film Charīkah-yi Tārā (Ballad of Tārā), directed by Bahrām Bayzā’ī, 1980.

Figure 10 (Right): The lady of the mansion is imprisoned in the cellar. A screenshot from the film Tilism (The Spell), directed by Dāryūsh Farhang, 1986.

Khusraw Sīnā’ī’s Hayūlā-yi Darūn (The Inner Beast, 1983) presents another instance of such characterization. A man has gone to a village to escape from his past, while his wife follows him like a ghost without skin and bone (Figure 11), challenging the picture of a real and down-to-earth woman. The woman’s ghost separates him from time and place and takes him to the past. This is the man’s sinful past in which the woman has become immortalized. Each of these women is abstracted from reality in a similar way. They are both “innocent” women who are sacrificed. Being ladies in white, they imply closeness to light and ideas of cleanliness, purity and the principle of Eternal Feminine.

This image of a woman, like other eternal concepts, becomes meaningful in a duality, that of angel/whore.37The Madonna/Whore complex was formulated by Freud. According to this complex, women are divided only in two categories of Madonna, which means she is pure, virtuous and nurturing; or Whore, which means she is sexually active, devious and unruly. Betty Friedan in The Feminine Mystique believes that the most recent representation of the duality of Madonna/whore, which has dictated the dominant image of women from a long time ago, can be seen in the chasm between the housewife and the working woman. See: Janet McCabe, Feminist Film Studies: Writing the Woman into Cinema (London: Wallflower Press, 2004), 5. The Madonna (the angel) is usually represented as a young woman who is as beautiful as she is, chaste and pure, and has an innocent heart. The more she suffers, the purer she becomes. On the other side of the spectrum, there is the woman who reveals herself, breaks all the boundaries, and accepts her role as a sexual object. This reminds us of the fall of the ethereal woman of The Blind Owl to the state of a prostitute who is earthly, wicked, and devious, accessible to all, and “has numerous lovers.”38Hidāyat, Būf-i Kūr, 46. She has her way with everyone except her husband and has gone too far in her debauchery. In The Inner Beast, too, it is only by committing suicide that the woman can escape falling into this state. Simone de Beauvoir explains the principle of the Eternal Feminine in this way:

“There are different kinds of myths. This one, the myth of woman, sublimating an immutable aspect of the human condition -namely, the ‘division’ of humanity into two classes of individuals- is a static myth. It projects into the realm of Platonic ideas a reality that is directly experienced or is conceptualized on a basis of experience; in place of fact, value, significance, knowledge, empirical law, it substitutes a transcendental Idea, timeless, unchangeable, necessary. This idea is indisputable because it is beyond the given: it is endowed with absolute truth. Thus, as against the dispersed, contingent, and multiple existences of actual women, mythical thought opposes the Eternal Feminine, unique and changeless.”39De Beauvoir, The Second Sex, 260.

In this situation, the reality that is directly experienced or conceptualized based on experience dissolves into abstract concepts that, regardless of the specific details of life, are formed around the generalities and the fundamental nature of femininity. Reality and the experiences of women of flesh and blood are replaced by a transcendental, timeless and inescapable idea. The changing and contingent existence of real women is countered by the mythical principle of Eternal Feminine. To create this immortality, the this-worldly femininity should be questioned. De Beauvoir borrows this term from the last lines of Goethe’s Faust:

What is destructible,

Is but a parable;

What fails ineluctably,

The undeclarable,

Here it was seen,

Here it was action;

The Eternal-Feminine,

Lures to perfection.40Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Goethe’s Faust, trans. W. Kaufman, (New York: Anchor Books, 1962), 503.

Figure 11 (Left): The woman’s ghost follows her husband after her suicide. A screenshot from Hayūlā-yi Darūn (The Inner Beast), directed by Khusraw Sīnā’ī, 1983.

Figure 12 (Right): Nāyī’s direct look. A screenshot from the film Bāshū, Gharībah-yi Kūchak (Bashu, the Little Stranger), directed by Bahrām Bayzā’ī, 1989.

The special moments of the woman’s life disappear because, historically, her experiences have turned into private and specific experiences of her own. Just as a wall of cloth covers a woman’s body in Islamic societies, a wall of silence covers the details of her life, too. She is a secret. Like the walls that enclose a house and separate the inside from the outside, the hijab also serves as a clear declaration of the separation of specific feminine experiences from public space. The hijab maintains an order that silences the concrete, specific, and private experience, signifying the power of deindividualization, protection, and secrecy.41Milani, Veils and Words, 23.

In such a situation, it is captivating to witness moments that represent the real experiences of a woman in the rather earthly femininity of Nāyī in Bahrām Bayzā’ī’s Bāshū, Gharībah-yi Kūchak (Bashu, The Little Stranger, 1989). There are, of course, interpretations of Nāyī as a general and non-individual character, and there are implications in the film itself to support such interpretations; for instance, it is believed that “Bashu is the continuation of Ballad of Tārā”; and that Nāyī is “a description of and a gratitude toward motherhood in all its aspects, as an attribute, a characteristic, a virtue that is expanded everywhere.”42Lahiji, Sīmā-yi Zan, 54–55. Here, too, love is desensitized, and “an indirect, complex and ambiguous love comes in.”43Naficy, “Veiled Visions/Powerful Presences,” 59. Nevertheless, there are moments and frames that contain Nāyī’s individual feelings rather than the feeling of a generalized idea. Most remarkable is the sudden close-up of Nāyī’s face, which, while showing her with a white scarf covering her hair and chin, concentrates on her passionate eyes. This is the look that shows us the potential of an earthly and lively look (Figure 12). She creates this moment while covering herself with a scarf, which signifies that the paradox between Nāyī’s modesty and her direct look at the camera is meant to emphasize the conflict between compulsory decency and personal expression. It also shows the simultaneity of accepting the rules and challenging them, which is one of the characteristics of cinema in later years and will be discussed in the final section.

We will end the discussion of the Eternal Feminine by referring to a film that differs from the previous ones in its search for realism: ‛Alī Zhikān’s Mādīyān (The Mare, 1986). The film fails to achieve realism, though, because in many parts, we can see the infiltration of generalizing ideas, such as the innocence of the virgin, and attempts to omit the accidental and “extraneous” elements of a real woman’s life. Rizvānah is a widowed woman struggling to cope with the burden of taking care of her children. Therefore, she intends to exchange her young daughter, Gulbutah, who is meant for a forced marriage, for a mare. It can be concluded that Rizvānah is not the ideal mother but rather an earthly and fragile woman, as we witness moments that show the loving relationship between Rizvānah and her children, as well as the tasks created for her in raising them. But upon closer inspection, we find that all her failures are overshadowed by her role as a mother, in which she occasionally stumbles. Rizvānah’s rebellion and violence are also transcended when she sees Gulbutah in a miserable state and decides not to exchange her. She is the type of mother who could seamlessly adapt to different circumstances:

The film talks about generalities and does not limit itself to specific realities of a specific environment. It goes from part to whole. This poignant story could also take place in a village on the edge of a desert or even in traditional cities beyond that, in places with similar social and cultural conditions to those depicted in the film.44‛Alī Zhikān, Mādīyān (Tehran: Nay, 2010), 128.

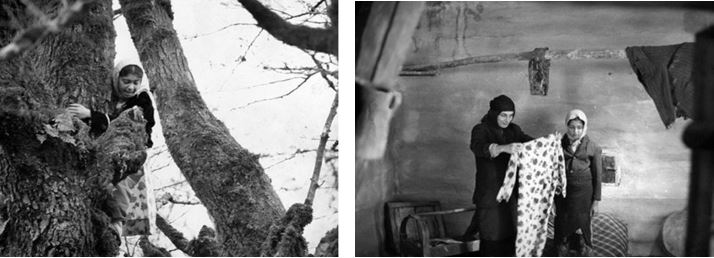

The innocence of the virgin in the film, Gulbutah, underlines this interpretation. Gulbutah is a weak and innocent girl who remains pure and untainted. She seems unattainable: a woman whom men desire, yet her own chastity prevents her from giving in to their advances. In the end, she becomes the sacrificial virgin whose innocence should be taken by force. The scene of her suicide attempt is replete with allusions to the innocence of the immortal idea of the holy virgin (Figure 14):

The sturdy ancient tree…, is rooted in the earth of tradition and the girl is chased by her suitor in it…. In one frame of this scene, we see a sapling emerging from the mud, stubbornly resisting the trampling feet of men and cattle. This sapling is Gulbutah. She is referred to as a sapling in the dialogues, too. Rizvānah says: “My dear Gulbutah, my sapling, my white silk.” And now, this sapling is faced with the ancient tree of tradition. Her failure is inevitable. When she realizes that the tree is not her refuge, she takes the final decision and throws herself down with the intent of killing herself. However, … she is caught in a branch of the tree, or one of the branches of tradition. From here on, the sapling is broken and the time of virginity and natural dignity is over.45Zhikān, Mādīyān, 124–125.

Figure 13 (right): Rizvānah shows Gulbutah the dress presented to her by her suitor. A screenshot from the film Mādīyān (The Mare), directed by ‛Alī Zhikān, 1986.

Figure 14 (left): To escape the unwanted marriage, Gulbutah throws herself down from the tree. A screenshot from the film Mādīyān (The Mare), directed by ‛Alī Zhikān, 1986.

Accepting and Rejecting the Image of “the Decent Woman”: The Appearance of Aspects of Desire

The image of the Iranian woman in the post-revolutionary cinema was fully committed to the idea of modesty. This ideal gradually took root in cinema, grew through many ups and downs and became normalized. Faced with such impositions from above, pressures from some producers and audiences from below, perhaps as a result of their own preferences, filmmakers tried to address or circumvent this issue using fictional and visual techniques to protect the film as a work of art. Beside the main technique discussed earlier, namely depicting an unreal woman, other measures were taken to escape limitations. For instance, it is no coincidence that Nāyī, just like Tārā and Rizvānah, is a woman from the north of Iran wearing traditional dress. Other filmmakers of this period also showed interest in picturing local women in traditional dresses. The frequent portrayal of rural women allowed directors to move away from the capital and the urban hijab (long, loose manteau, chador, and dark scarf).46It should be noted that the small societies had come under attention before the Revolution by Ghulām-Husayn Sā‛idī’s stories, Suhrāb Shāhīd Sālis’s feature films and Hūshang Shāftī’s documentaries. After the Revolution, making such documentaries was in decline; however, perhaps because of the existing limitations, notable films were made about these societies. For further reading about ethnographic cinema, see, Hamid Naficy, “The Anthropological Unconscious of Iranian Ethnographic Films: A Brief Take,” Cinema Iranica Online (2024). https://cinema.iranicaonline.org/article/the-anthropological-unconscious-of-iranian-ethnographic-films-a-brief-take/

These are just examples of suggested “solutions” that, approaching the end of the 1980s and recovering from the initial shock of the revolution and the war with Iraq, were presented with bolder frequency and resulted in modifications in the limitations. Filmmakers’ compliance with realities after the Revolution was predicated on maintaining a balance between obedience and creativity. They found novel ways to tell their stories within the framework of limitations, the general criteria for which had already been established by then. For example, to prevent the banning of his films, Dāryūsh Mihrjū’ī often compromised with the officials and consented to their demands. For instance, he altered the ending of the film Ijārah-nishīn-hā (The Tenants, 1987) due to censorship, while also incorporating critiques of the prevailing situation in the film. This approach let him (to) stay fit within the framework. Bayzā’ī also delicately challenged the limitations; as a result, he was able to continue working for several years after the 3-year banning of his film, Bashu.

Meanwhile, Bahrām Bayzā’ī’s Shāyad vaqt-i dīgar (Maybe Some Other Time, 1988) showed women in more multifaceted roles. Here, too, the development of individual characters is intentionally prevented by a single actor playing the roles of the three women –mother, Kiyān and Vīdā. However, the filmmaker, by disrupting conventional cinematic techniques such as “the interrupted shot–reverse shot…, a visual stutter of sorts,”47Mottahedeh, Displaced Allegories, 52. draws the spectator’s attention to the mediating conventions of dominant cinema and engages them with the narrative, particularly in how women are depicted. Additionally, the character of the woman in this film, besides other characters like Farīshtah in Tahmīnah Mīlānī’s Bachah’hā’yi talāq (Children of Divorce, 1991) attracted the modern middle-class woman to cinema.

Figure 15: A screenshot from the film Shāyad vaqt-i dīgar (Maybe Some Other Time), directed by Bahrām Bayzā’ī, 1988.

Alongside these new trends, the conservative movements underwent changes as well. These changes are nowhere more visible than in Muhsin Makhmalbāf’s films. There is a meaningful break between his initial films and those he made in the late 1980s. As a filmmaker committed to the cause of Revolution, in films such as Tawbah-yi Nasūh (Pure Repentance, 1983) and Isti‛āzah (Fleeing from Evil to God, 1984), he sought the nature of redemption through living an Islamic lifestyle. However, in 1990, he presented Nawbat-i ‛Ashiqī (Time of Love) and Shab-hā-yi Zāyandah-rūd (The Nights of Zayandehroud) in the Ninth Fajr Film Festival, which sparked a great deal of critique. These films focused on the themes of earthly love and the rights of women to choose their life partners. In addition, Time of Love showed extreme close-up shots of Ghazal’s face, such as her lips and eyes, which came as a surprise in a cinema that only accepted depictions of women in long and medium shots. These controversies prompted Murtazā Āvīnī, the journalist and documentary filmmaker, to label Makhmalbāf as a defender of “sexual liberalism” who believes that “the way out of despair” lies in “the sexual attraction between woman and man.”48Murtazā Avini, “Nawbat-i ‛Ashighī va Shab-hā-yi Zāyandah-rūd: Vaqtī Bādkunak Mī-tarakad… (Time of Love and The Nights of Zayandehroud; When the Balloon Pops…),” in Āyinah-i Jādū (The Magic Mirror), vol. 2 (Tehran: Vāhah, 2011), 148–76. Although these films were banned, they clearly show the change in the orientation of their directors. This change was not limited to cinema. One year before, Ahmad Samī‛ī Gīlānī, the translator and writer, wrote about his disagreement with the omission of sexual content in novels and attempted to justify his position by examining ancient Persian literature:

Anyway, if these scenes are included in the novel, perhaps there has been no way to avoid them; as is the case in the discussions of jurisprudence and medical sciences, where there is no way to avoid naked and explicit descriptions and even pictures…. If some scenes of a novel are to be omitted because of protection and chastity, then no small parts from masterpieces of Persian literature should also be omitted; for example, in Kalīlah va Dimnah, the story of the barber’s wife; or the story of a hermit who finds himself in a brothel and has to spend a night in “a wicked woman’s house” who has “such and such concubines” and witnesses obscenities; or in Masnavī-i Ma‛navī, the famous story of the woman who uses the zucchini in a way she should not; or in Sa‛dī’s Gulistān, the story of the judge in Hamedan who has a relationship with a “shoemaker boy”. Anyway, including scenes that are not exactly chaste does not signify preaching and promoting what is going on in them…. It is the nature of a novel to refine them through the sieve of art…. Novel is the creation of beauty; and even when vices are described, the description is still beautiful.49Ahmad Samī‛ī Gīlānī, “Rumān, Dunyā-yi Khīyāl-i ‛Aṣr-i Mā (Novel, the Imaginative World of Our Age),” Nashr-i Dānish 55 (1990): 4-5.

We started the discussion by looking at the character of A‛zam played by Farīmāh Farjāmī in Exposed; and now we will refer to another role played by this actress in Nargis (Rakhshān Banī’i‛timād, 1992) to clarify the changes that happened in these years. Both of these films are about marriages that take place due to an external necessity; the first one was because of the dangers that were threatening A‛zam and prompted Murtazā to take her under his care; and in the second one, it is Āfāq who, in order to support ‛Ādil, makes him marry her. Āfāq is an older woman who married at a very young age and later divorced, resulting in her being separated from her son. This emotional gap with the child was filled with ‛Ādil. But gradually, this feeling results in a one-sided love by Āfāq. Now, while meeting Nargis, ‛Ādil suddenly realizes that he wants an ordinary life with Nargis. The conflict shown in this film is the result of Āfāq standing between ‛Ādil and Nargis. Although a kind of affection –without any sexual desire– was seen in Murtazā in Exposed, he simply and intentionally pulls back, allowing A‛zam and her husband to live together again. But in here, Āfāq doesn’t hold back. The director –indirectly and through signs– emphasizes her desire; for example, when ‛Ādil knocks on Āfāq’s door, we see her in the mirror putting make-up on, which reveals the existence of desire in their relationship.

Figure 16: A screenshot from the film Nargis, directed by Rakhshān Banī’i‛timād, 1992.

We observe in this period that relationships become earthlier and expressions of desire are more direct. This shift in direction was made possible alongside changes in cultural policies. At the end of the 1980s, when the revolutionary discourse was replaced by reformist policies in the political field, cinema started to change as well.50Blake Atwood, Reform Cinema in Iran: Film and Political Change in the Islamic Republic (New York: Columbia University Press, 2016), 4. The year 1989 was a fateful year, as the war between Iran and Iraq ended and the leader of the Islamic Revolution died. These events created an opportunity to challenge the government’s strict rules and its failures in economic and social sectors. The new reformist political party came into being. The Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance, especially under the leadership of Muhammad Khātamī, supported the filmmakers and supervised film censorship. This dual approach created a complicated situation that, to some extent, encouraged filmmakers to work, while simultaneously imposing significant limitations on them. This trend had some ups and downs with the conservatives coming to power, but the changes remained relatively permanent.

The question is, to what extent have these attempts made the limitations more bearable. Is this essentially possible? We attempted to take a small step toward answering this question by showing that, throughout history and in what might today be seen as an inevitable and self-evident experience in post-revolutionary cinema, nothing has truly been inevitable. It is neither an accidental nor a necessary outcome for post-revolutionary cinema to follow a certain path and formulate a specific image of woman; it is actually the result of certain interactions in this specific period of time. The next steps to complete the discussion of this article and find answers to the questions involve delving deeper into the very existence of compulsive and oppressive elements in art, as well as exploring the possibility—or impossibility—of neutralizing them with cinematic techniques in a way that leaves the work of art unaffected. It should be sufficient to point out, in a sense, that the existence of oppressive elements in art can negatively impact the aesthetic of the work in various ways, even if this compulsion remains concealed. This is because the oppressive element creates an “imaginative resistance” that happens when a competent imaginator is asked to participate in an imaginative activity but he/she experiences psychological tension. The difficulty most people have in imagining a subject like the killing of daughters may be explained by the fact that they do not verify this moral judgment in reality.51Joy Shim and Shen-yi Liao, “Ethics and Imagination,” In Oxford Handbook of Ethics and Art, ed. James Harold (New York: Oxford University Press, 2023), 711. This resistance cannot be reduced to something outside the film. This is an aesthetic failure.52Noel Caroll believes that when the audience’s imagination does not accompany the immoral themes and situations, we are dealing with an aesthetic failure:…in order to design various characters and/ or situations in such a way that emotions like anger and indignation will be elicited, those characters and/ or situations must be constructed in such a way that they satisfy the criteria for the emotions that they are intended to elicit. Failure to do so is an aesthetic failure. It is an aesthetic failure because it is a formal failure, since, according to a functional view of form, the formal features of a work are those choices that are implemented or designed with the intention to realize the constitutive purposes of the artwork. If a choice that is designed to realize the constitutive purpose of the work blocks the attainment of the constitutive purpose of the work, that is a formal defect of the work.See: Noel Caroll, “Moralism,” in Oxford Handbook of Ethics and Art, ed. James Harold (New York: Oxford University Press, 2023), 306-307.

This situation also applies to the limitations imposed on the clothing, appearances, and behaviors of women in post-revolutionary cinema. These types of interventions can evoke imaginary resistance, as a sensitive audience is likely to experience it during this encounter. This does not escape his or her attention, even if this image is embedded in the logic of the story.

Cite this article

After the Islamic Revolution in Iran, creating a “decent” image of women was a pervasive concern. Not wearing a hijab was criminalized in 1983, but before this, the emerging norms were met with various reactions. Some filmmakers conformed with them and even cleared the path; some others resisted them in their own ways. Eventually, as a result of the compromise between governmental regulations and limitations and various measures taken by filmmakers and producers, a visual grammar representing the “decent woman” of the revolutionary era was created. This is how the image of women in the cinema of the early 1980s was redefined: she was a woman who was not instrumental in the story and, more often than not, was presented in medium and long shots behind multiple layers of scarfs, large and loose clothes, long skirts and long dark dresses; or, if she had an instrumental role in the story, it was abstracted from reality. In this article, we will explore how the core of this image was formed, expanded, and normalized on screen, and occasionally challenged as well.