Abbas Kiarostami as a Universal Filmmaker

Figure1: ‛Abbās Kiyārustamī with the Palme d’Or for Best Director, the Cannes Film Festival, 1997.

Paradoxically, the status of ‛Abbās Kiyārustamī (1940-2016) as a universal filmmaker appears to be one of his most underrated virtues. Iranian friends and colleagues have told me that his so-called “Western” traits are often viewed critically inside Iran, as a form of catering to Western film culture for “Western” rewards, while it appears that much of his reputation outside Iran is predicated on what he has to say or reveal about his home country to outsiders. To my mind, neither position is adequate for understanding and appreciating most of the greatest film artists. Calling Alfred Hitchcock an English filmmaker hardly does full justice to his work in Hollywood, and such major figures as Michelangelo Antonioni, Charlie Chaplin, René Clair, Carl Dreyer, Jean-Luc Godard, Howard Hawks, John Huston, Stanley Kubrick, Akira Kurosawa, Fritz Lang, F.W. Murnau, Max Ophüls, Otto Preminger, Nicholas Ray, Jean Renoir, Eric Rohmer, Roberto Rossellini, Raoul Ruiz, Douglas Sirk, Jacques Tourneur, Maurice Tourneur, François Truffaut, and Orson Welles (among many others) were all globetrotters who made films in more than one country.

It’s my conviction that Kiyārustamī, despite his reputation as an Iranian filmmaker, was a global artist who should be considered alongside the two dozen film directors listed above, and not only because he shot features in Uganda, Italy, and Japan near the end of his career. To my mind, he was a global filmmaker whose observations about the world in general account for much of his greatness and originality, and in the remarks that follow, I’d like to explore these virtues. Due to the lamentable habit of film critics and film teachers of classifying film artists as if they were zoo animals belonging to species that are defined nationally and often housed or caged in what appears to be their “natural” habitats, one could argue that the major figures who can’t be classified in this way are in certain respects stronger because of this multicultural range. Indeed, I’d like to suggest that Kiyārustamī’s value as a world artist exceeds his importance as an Iranian artist, even though his Iranian traits, such as poetry and humanism, clearly contributed to his value.

Indeed, one indication of Kiyārustamī’s strength is the influence exerted on his work by non-Iranian filmmakers including Robert Bresson, Roberto Rossellini, Jacques Tati, and Yasujiro Ozu, as well as by other kinds of artists outside of Iran, diverse figures ranging from Louis Armstrong to The Beatles to Antonio Vivaldi to Pieter Bruegel. It seems pertinent that Kiyārustamī’s very first film, The Bread and Alley (Nān u Kūchah, 1970) uses as its musical accompaniment a jazz performance by alto saxophonist Paul Desmond of the Beatles tune “Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da.” This could be compared and contrasted with certain non-Iranian influences on some of Kiyārustamī’s contemporaries, such as the respective impacts of Alain Resnais and Michelangelo Antonioni on Ibrāhīm Gulistān’s The Crown Jewels of Iran (Ganjīnah-hā-yi Gawhar, 1965) and Brick and Mirror (Khisht u Āyinah, 1965), and of Sylvia Plath on Furūgh Farrukhzād’s The House is Black (Khānah siyāh ast, 1962). But it’s worth mentioning that unlike many of his filmmaking colleagues, Kiyārustamī was not a cinephile.

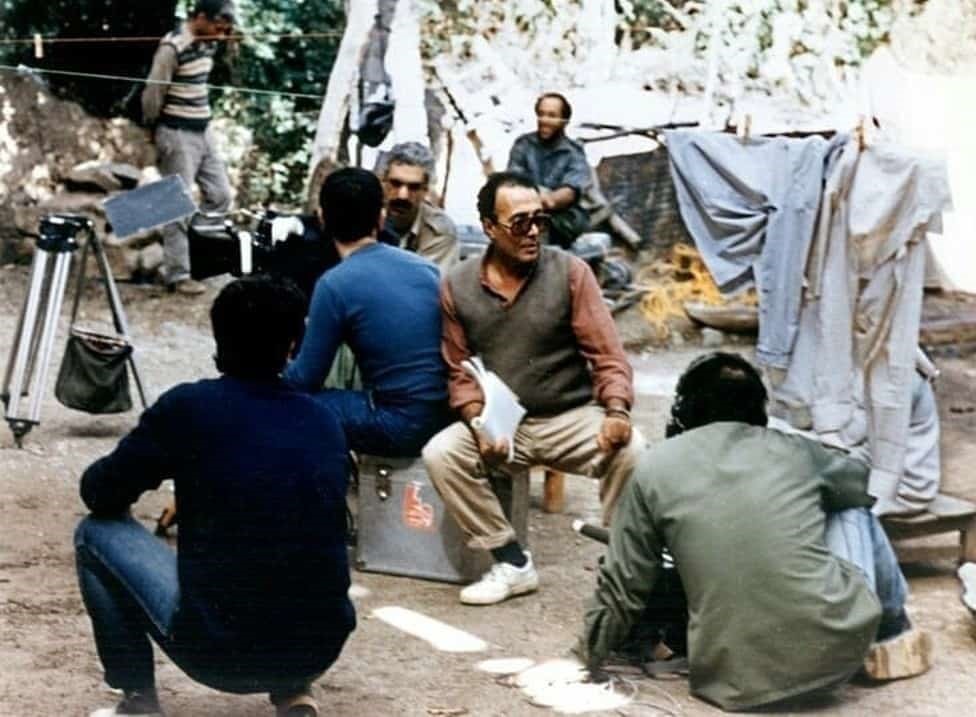

Figure 2: Kiyārustamī behind the scenes of Where Is the Friend’s House? (Khānah-yi Dūst Kujāst), directed by ‛Abbās Kiyārustamī, 1987.

It has long been my contention that some of Kiyārustamī’s late features—most notably Taste of Cherry (Ta‘m-i gīlās, 1997) and The Wind Will Carry Us (Bād mā rā khvāhad burd, 1999), but also Close-Up (1990)—are reports on the state of the world at the time they were made, much like many of Jean-Luc Godard’s films made during the 1960s, such as Une femme mariée (1964), Alphaville (1965), Made in USA (1966), and Weekend (1967). I would also maintain that the growth and development of the global economy between the 1960s and the 1990s may account, in part, for the difference between the urban settings of Une femme mariée and Alphaville and the suburban or rural landscapes of Taste of Cherry and The Wind Will Carry Us. Once multinational corporations start to rule the world, the same manifestations of their presence and control can be felt everywhere, as in the media antennas of Life, and Nothing More… (Zindagī va dīgar hīch, 1992) and The Wind Will Carry Us and in the hero’s mobile phone in the latter film.

The eight short films made by Kiyārustamī between 1970 and 1982 offer an interesting riposte to critics who claimed during those years that they knew what was going on in world cinema. Even in Iran, where the shorts were made, none constituted much of an event. And considering how deceptively modest they are, they probably never would have attracted much notice anywhere if their director hadn’t gone on to make a string of masterful features. Yet, there’s nothing else in cinema quite like them.

All this only confirms that it’s preposterous to pretend that anyone can know the state of world cinema —unless, that is, we reduce “world cinema” to the films that get promoted, most of which are semi-mindless crowd-pleasers. For too long, we have been letting our cultural commissars—producers, exhibitors, distributors, official and unofficial publicists (including critics)—dictate the limited range of choices we’re supposed to want.

Kiyārustamī’s simple yet profound early shorts are a good example of the kind of cinema that typically falls between the cracks. They were all produced by the state-run organization called Kānūn, better known as the Centre for the Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults (Kānūn-i Parvarish-i Fikrī-i Kudakān va Nujavānān), founded by the shah’s wife, Farah Dībā.

Kiyārustamī had been a commercial artist throughout the 1960s, starting out with posters and book jackets before graduating to television commercials and designing films’ credit sequences. He was already pushing thirty when the owner of an advertising agency that he had worked for, now the director of Kānūn, invited him to help set up the organization’s film unit in 1969.

Assigned to make educational films, Kiyārustamī wound up creating a particular kind of pedagogical cinema that was both experimental and playful, though he once said to me in an interview that he didn’t regard himself as a film artist when he made them. They played a substantial role in making films about children fashionable in Iran, although they weren’t always made for children. In fact, the last two films that he made for Kānūn went out into the world in the early 1990s as grown-up art features, Close-Up and Life, and Nothing More… The first of these, Kiyārustamī’s initial calling card in the West, contains no children at all. A few of the shorts—Breaktime (Zang-i tafrīh, 1972), also known as Recess, Two Solutions for One Problem (Du rāh-i hall barāyi yak mas’alah, 1975) and So Can I (Manam mī-tavānam, 1975), Orderly or Disorderly (Bih tartīb yā bidūn tartīb, 1981)—are set wholly or partially inside schools, and nearly all qualify in some fashion as didactic works, comparable to what Bertolt Brecht called Lehrstücken, or learning plays. Working within such a framework, Kiyārustamī could reflect on the advantages of cooperation over conflict (in Two Solutions for One Problem), draw on animation (used briefly in So Can I) or abstraction (as in The Colors [Rang-hā, 1976]), comically raise philosophical questions about order and disorder (Orderly or Disorderly), or formal as well as social questions about sound (in The Chorus [Hamsurāyān, 1982]), simply offer lessons in dental hygiene (Toothache [Dandān-dard, 1980]), and even explore how a man might roll a car’s tire down a highway (Solution [Rāh-i hall, 1978]) or how a little boy with a loaf of bread might get past an unfriendly dog (The Bread and Alley, 1970).

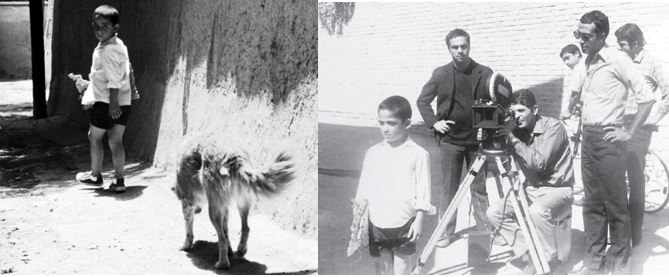

Figure 3 (left): A still from the film The Bread and Alley (Nān u Kūchah), directed by ‛Abbās Kiyārustamī, 1970.

Figure 4 (right): Kiyārustamī behind the scenes of The Bread and Alley (Nān u Kūchah), directed by ‛Abbās Kiyārustamī, 1970.

The latter is the subject of Kiyārustamī’s first film, drawn from an experience recounted by his brother Taqī (who was credited with the script). His second film, Breaktime, follows a boy heading home from school after being ejected from class for breaking a window, and Kiyārustamī’s design background becomes apparent when an early intertitle appears neatly and eccentrically over a wall at the end of a school corridor.

Try to imagine Laurel and Hardy directed by Robert Bresson, and you may get some notion of the hilarious performance style of Two Solutions for One Problem—a syncopated, deadpan grudge match between two schoolboys that ensues after one returns a borrowed book to the other with its cover torn. The camera lingers on the resulting damage, including a broken pencil, a ripped shirt, and a split ruler, while an offscreen narrator explains whose possessions got destroyed. Then, the story begins again with the torn book cover being glued back by the guilty party, proposing a second solution to the problem.

Children imitate the movements of other creatures in matching shots in So Can I; contrasting forms of behavior as seen at a school and a busy traffic intersection are the subject of Orderly or Disorderly. Other kinds of repetitions, parallels and contrasts recur in these shorts (as well as in Homework (Mashq-i shab, 1989), a feature-length documentary made in 16-millimeter for Kānūn in 1988) as formal principles and subjects. In Kiyārustamī’s subsequent features, moreover, where they’re no less central, they often wind up structuring the action.

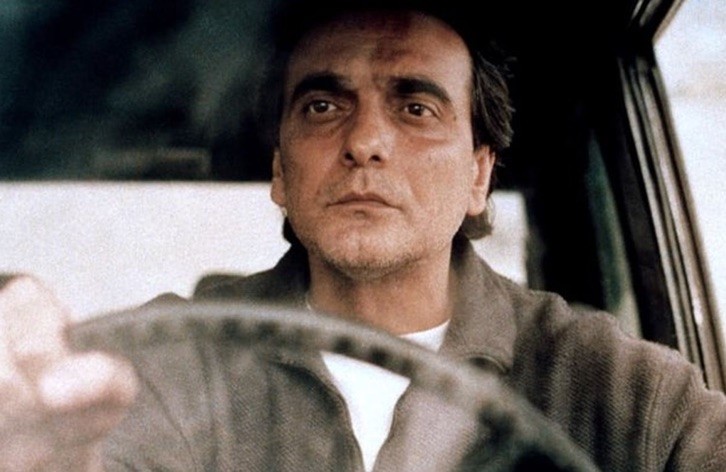

In Where Is My Friend’s House? (Khānah-yi Dūst Kujāst, 1987), this entails running up and down a zigzagging hillside path. In Homework and the fiction film Life, and Nothing More… (1992), it consists partly of asking several people the same questions. In Through the Olive Trees (Zīr-i dirakhtān-i zaytūn, 1994), it involves two amateur actors in a film comically blowing take after take. Taste of Cherry (1997) follows a middle-aged man in a car repeatedly asking strangers to bury him if he succeeds in killing himself. The Wind Will Carry Us (1999) shows a brash media person in a remote Kurdish village repeatedly driving up a hill to receive calls on his mobile phone.

Figure 5: A still from the film Taste of Cherry (Ta‘m-i gīlās), directed by ‛Abbās Kiyārustamī, 1997.

This form of patterning is often a way of posing questions, and I would argue that Kiyārustamī belongs to that tribe of filmmakers for whom a shot is often closer to being a question than to providing an answer. This tribe includes John Cassavetes, Chris Marker, Otto Preminger, Jacques Rivette, Andrei Tarkovsky and, in his last three features, Jacques Tati (all of whom, with the exception of Rivette, were significantly also globetrotters). All these filmmakers confound many spectators by not providing the sort of narrative assurances they expect from cinema, and most of them have a particular predilection for what might be termed philosophical long shots and all the questions these imply.

Figure 6: A still from the film The Wind Will Carry Us (Bād mā rā khvāhad burd), directed by ‛Abbās Kiyārustamī 1999.

The Colors recalls the abstract montages of Hollis Frampton’s Zorn’s Lemma in terms of its color coding, but it also indulges violent fantasies involving cars, guns, little boys, and paint. The Chorus, by contrast, explores sound and its absence in narrative terms, through the story of an old man who escapes urban noise and his granddaughter by turning off his hearing aid. The most remarkable of the shorts, Orderly or Disorderly, shows boys leaving a classroom, heading for a water fountain and getting on a bus, then offers a cosmic overview of adults driving through a busy section of Tehran. Each action is shown twice, with the boys or adults behaving in an orderly or disorderly fashion, though the degree to which this is being staged or documented is teasingly imprecise — a kind of ambiguity that continues in Kiyārustamī’s work thereafter. The difference is that whereas in the 1982 short, Kiyārustamī was playfully foregrounding his work as a director, including his own instructions and comments to his crew in every take, in Ten (Dah, 2002) two decades later, he is avowedly trying to make a film without any direction at all, comparing his own function to that of a football coach, and ringing a bell between sequences as if they were separate innings. In this film, one might alternatively say he is proceeding more like a journalist than like a teacher. But as Close-Up demonstrated, few modern directors handle journalism so artfully and so ambiguously.

While Kiyārustamī was making his original and delightful early shorts, film critics elsewhere in the world were reminding their readers that the important contributions to world cinema all came from the U.S., South America, Europe, and Japan, with a few exceptions (generally one per continent — Satyajit Ray in India, Ousmane Sembène in Africa). China, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Korea, Egypt, and Iran were written off as producing films strictly for their own inhabitants, with little to interest sophisticated cinephiles. Today, when a good many more films are clamoring for our attention, it seems reasonable to assume that we might be missing at least as much. It’s fascinating to consider the ideological factors that influence how film canons are formed, especially when it comes to films that depict unfamiliar cultures. Without thinking much about it, we tend to prefer American movies that suggest either that foreigners are just like us (the liberal approach, as in Samuel Fuller’s China Gate, in which Angie Dickinson is cast as a Eurasian) or that they’re devils from another planet (consider the xenophobic and racist depictions of Viet Cong soldiers in Michael Cimino’s The Deer Hunter). The possibility that they might be neither is often more than the media can handle, with the unfortunate consequence that movies are less likely to succeed commercially when they depict foreigners as complex beings who are not carbon copies of ourselves—movies, in short, that are human in their approach but not necessarily idealistic or sentimental or bourgeois humanist. When it comes to foreign movies that depict their own cultures, the same rules apply but with even greater force.

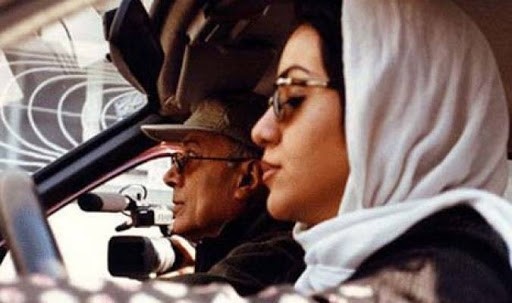

Figure 7: Kiyārustamī behind the scenes of Ten (Dah), directed by ‛Abbās Kiyārustamī, 2002.

As one index of how ill-equipped most of us are to deal with films made in Iran, consider the kind of treatment Iranian or proto-Iranian characters have received in American movies — and it only became worse after the Islamic revolution and the seizure of American hostages in Tehran in 1979, in pictures like Raiders of the Lost Ark. Not surprisingly, we’re often insecure even about the most basic elements of Iranian cinema, such as titles and locations. Consider the title of Life, and Nothing More…, which won the Rossellini Prize at the Cannes Film Festival. It was called Et la vie continue in France and was given an English title that’s a precise translation of that. Yet, I’m told that a more accurate translation of the Iranian title is Life, and Nothing More. But because the latter title might have been confused with Bertrand Tavernier’s Life and Nothing But, Americans were originally stuck with the more sentimental and less accurate And Life Goes On… I first saw this feature at the Locarno film festival, and to me, it was far and away the most exciting new film shown there. Most of the Locarno festival’s main films were projected on an enormous outdoor screen in the town square, where thousands of people watched at once. Kiyārustamī’s film was not one of them, and the festival’s director told me that the only reason for this was that Kiyārustamī himself feared the film wouldn’t “work” on such a grand scale.

Figure 8: Poster for the film Life, and Nothing More (Zindagī va dīgar hīch), directed by ‛Abbās Kiyārustamī, 1992.

When I saw Kiyārustamī’s film a second time—at a retrospective of Iranian cinema at the Toronto Festival of Festivals—the festival program described it as a film dealing with the aftermath of an earthquake in northern Iraq. The earthquake in question—responsible for the deaths of over 50,000 people in 1990—actually took place in northern Iran. Though the difference of one letter could perhaps be excused as a simple typo, I think it also points to a more general misunderstanding.

Consider that during the recent Gulf War, Iranians in this country were widely confused with émigrés from Iraq, despite the fact that the two countries speak different languages and spent the better part of the last decade at war with each other. Formally, the resemblances between Kiyārustamī and Muhsin Makhmalbāf, the best known of his contemporary colleagues, are striking. Both take an almost completely open-ended and serial approach to narrative, allowing an ultrasimple, linear plot with a clearly defined and highly restricted time span to carry the film. Both completely avoid close-ups and show a taste for long shots in which they observe figures moving across vast landscapes. Both employ “comparative” editing that juxtaposes the behaviors of different characters from the same fixed camera setup; and both mix documentary and fictional elements in a manner that’s virtually impossible for the spectator to disentangle.

All four of these formal elements are present in the opening sequence of Life, and Nothing More…, and all but the third are present in the last. The opening sequence is seemingly a documentary record of motorists stopping at a tollbooth, filmed from the fixed vantage point of the tollbooth (with only the forearms of the attendant visible), and edited so that we have the impression of watching a single continuous take. It calls to mind the sequences contrasting the behaviors of various motorists in Tati’s Trafic, though what we hear—over a radio and from drivers and the attendant—is strictly expositional material about the recent earthquake.

The eighth and last of the drivers in this sequence essentially defines our angle on most of the remaining action in the film; practically everything else from here on is from the vantage point of this man or of his little boy. The greatest departure from this convention is the film’s extended final shot — a beautiful, mysterious long shot fully worthy of Tati — and final sequence, which shows the separate progress of the man’s car and of a pedestrian on a road leading in a left-to-right diagonal up a steep hill, and then right to left across a horizontal ridge in the same terrain.

We learn at the outset that the nameless middle-aged man (Farhād Khiradmand) is driving to the earthquake site with his son (Pūyā Pāyvar) in an attempt to find two of the male children who acted in Where Is the Friend’s House? five years earlier. It’s apparent that the man is a sort of stand-in for Kiyārustamī himself, who did spend a morning and afternoon with his son three days after the earthquake driving to villages hit by it. Then he returned five months later to re-create this experience with the real-life participants and two actors to play himself and his son but set the action five days after the earthquake. According to Kiyārustamī, for economic reasons he used his own car in the film.

Figure 9: Farhād Khiradmand and Pūyā Pāyvar in a still from the film Life, and Nothing More (Zindagī va dīgar hīch), directed by ‛Abbās Kiyārustamī, 1992.

Curiously, there’s never any reference to a wife or mother. In some respects, the man and boy call to mind the semi-invisible reporter played by William Alland in Citizen Kane, but with the pertinent difference that implicitly they’re mediators whose middle-class point of view allows us to see the working-class villagers from a safe distance. The periodic use of Vivaldi is crucial too, because this music clearly “belongs” to the father and to the audience in a way it does not to the villagers. The equivalent “elevated” culture for them is the Brazil-Argentina soccer game to be shown on TV—the kind of event usually more available to city people—and it’s one of the film’s key signs of hope and humor that people whose lives have been devastated by disaster can be preoccupied with setting up a TV antenna so they’ll be able to watch the game.

A surprising amount of the film consists of point-of-view shots—from the father’s vantage point driving his car through the ruined area, and from the boy’s, riding in the backseat. When they make an occasional stop along the way, the camera follows each of them separately as they converse with various villagers and records their different degrees of receptivity, without making any judgments about their different characters. Our sense of their open-ended, almost undirected curiosity—reflected in the way they periodically forget about the boys they’re searching for, thereby persuading us to forget the film’s narrative pretext too—calls to mind the extremely long takes of the Egyptian countryside in Jean-Marie Straub and Daniele Huillet’s powerful and beautiful documentary Too Early, Too Late (1981), a film that also returns us at times to a prenarrative Eden, to the innocence of a child’s eye and ear with no story to guide them.

The film’s exquisite sense of reality is, of course, a construction. It’s really nothing more than a profound sense of material presence, a way of placing us as spectators in the middle of an event being reimagined and observed at the same time. Kiyārustamī’s feeling for space and duration allows us to enjoy the unique textures of a place and event and gives us plenty of time to reflect on them. The fact that all of this happens to be taking place in Iran may well end up striking us Westerners as secondary.

At the Toronto Film Festival in 1995, Canadian filmmaker Clement Virgo recalled the memorable response of Winston Churchill to pressure to cut state arts funding during World War II: “If we cut funding for the arts and culture, then what are we fighting for?” A month earlier, while I was in the middle of looking at close to a hundred films as part of the New York Film Festival’s selection committee, I had the rare privilege of being able to fly for a weekend to still another festival, in Locarno, Switzerland, to serve on a panel devoted to Godard’s Histoire(s) du cinéma. Locarno had two ambitious sidebars that year—one devoted to Godard’s video series, the other to Iranian women filmmakers and the first virtually complete retrospective of work by Kiyārustamī ever held anywhere, including an exhibition of his color photographs of landscapes and two very beautiful paintings.

Figure 10: A still from the film Life, and Nothing More, directed by ‛Abbās Kiyārustamī, 1992.

Both Godard and Kiyārustamī could be described as creatures of state funding, hence representatives of what Churchill argued a country should fight for and what Newt Gingrich would contend we can and must learn to live without. Interestingly enough, in a letter to the New York Film Critics Circle the previous January, Godard paid tribute to Kiyārustamī, lamenting his inability “to force [the] Oscar people to reward Kiarostami instead of Kieslowski.”

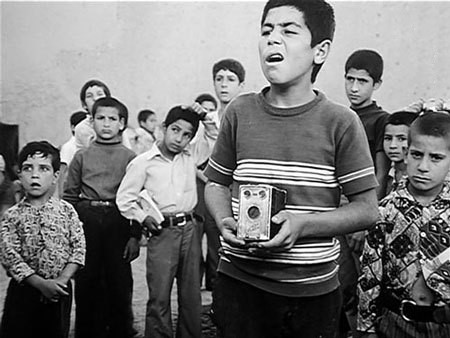

The fact that Kānūn enabled Kiyārustamī to forge a style and method of filmmaking that weren’t dependent on commercial norms for survival is partly what accounts for his originality. But the thematic constant in his work that makes it more universal is an ethical exploration of how a filmmaker relates to the people he films, making much of his work a form of autocritique. Although this preoccupation is especially pronounced in The Wind Will Carry Us, his last feature shot in 35-millimeter, it is already a concern in what can be regarded as his first major work, The Traveler (Musāfir, 1974), about a boy who raises money by pretending to photograph his friends with an empty camera so he can travel by bus to Tehran to attend a soccer match with his favourite team. (Significantly, Kiyārustamī’s only previous short feature, The Experience (Tajrubah, 1973), is about a boy who runs errands for a photography shop.) The fact that the boy winds up oversleeping and missing the soccer match—occasioning the only dream sequence in a Kiyārustamī film, seemingly haunted by his guilt for having exploited his classmates—makes this story one of the first of the absurdist and comic quests favoured by Kiyārustamī in which a monomaniacal hero pursues a single goal, creating a storyline that eventually autodestructs in some fashion.

Figure 11: A still from the film The Traveler (Musāfir), directed by ‛Abbās Kiyārustamī, 1974.

Another near-constant in Kiyārustamī’s work pointing to his ethical concerns is regarding his audience as creative collaborators, aiming to place them on an equal footing. The best expression of this attitude can be found in a statement made by Orson Welles in 1938, before he even started as a filmmaker: “I want to give the audience a hint of a scene. No more than that. Give them too much and they won’t contribute anything themselves. Give them just a suggestion and you get them working with you. That’s what gives the theatre meaning: when it becomes a social act.”

Ironically, it was Kiyārustamī’s sense of filmmaking as a social act that presented the greatest challenge to his commercial status, a challenge that Welles also suffered from. (It seems worth adding that the state support of Welles’s early theater work, like Kānūn’s support of Kiyārustamī, is what made his enlisting of his audience as collaborators possible.) The lack of any conventional narrative closure in Life, and Nothing More…, Through the Olive Trees, Taste of Cherry, Ten (2002), Certified Copy, (2010), and Like Someone in Love (2012), are implicitly invitations to the films’ viewers to furnish their own conclusions, thus refusing the principle of completion deemed necessary for mainstream success. Our difficulty in synopsizing these films stems directly from Kiyārustamī’s insistence that we furnish our own endings. Audience expectations about where the camera goes—and what it finds—are deliberately flouted in these films. Furthermore, these are only some of the conspicuous absences, lacks, or outright deletions to be found in Kiyārustamī’s films. Parts of the soundtrack in some of the latter portions of Homework (1988) and Close-Up, for instance, have been suppressed (openly in the first case, and surreptitiously—by faking a technical glitch—in the second). In most of these cases, these are omissions in which we’re asked to fill in the blanks. Consequently, in the most literal and even trivial sense, we are what Kiyārustamī’s movies are about, and apart from a few notable exceptions—e.g., Shīrīn (2008)— “we” are not necessarily Iranian.

Kiyārustamī’s unusual methodology in shooting these films should also be noted. Most of the dialogue in Taste of Cherry is between a man contemplating suicide and a Kurdish soldier, an Afghan seminarian, and a Turkish taxidermist, yet none of the actors playing these roles met during the shooting. Kiyārustamī himself shot each of these actors in isolation, and only after combining the separate shots did the characters appear to be in proximity to one another. Only in the film’s concluding sequence—a video shot by one of Kiyārustamī’s sons during a break in the film’s shooting—are some of the film’s characters (along with Kiyārustamī and his skeletal crew) seen together in the same space.

In The Wind Will Carry Us, many of the film’s major characters, including the hero’s own camera crew, are systematically kept offscreen, and the 100-year-old Kurdish woman whose death and funeral they’re awaiting is never seen either. Because this film was made in 1999, it’s tempting to interpret the centrality of this century-old character as part of a millennial statement, but if, in fact, the film was conceived in such terms, this could only be done by privileging the Western calendar over the Iranian calendar.

The hero of The Wind Will Carry Us is a man from Tehran named Bihzād (Bihzād Dawrānī), who drives with a camera crew of three to a remote Kurdish village clinging to the sides of two mountains. There they secretly wait for an ailing 100-year-old woman named Mrs. Malik to die, apparently planning to film or tape the exotic traditional funeral ceremony they expect to take place afterward, as part of which some women mourners scratch and scar their faces. Bihzād spends most of the movie biding his time in the village, circulating a false story (involving buried treasure) about the reason for his presence and chatting with a few locals—mainly a little boy named Farzād (Farzād Suhrābī), the old woman’s grandson, who serves as his (and our) main source of information about the village.

Figure 12: Farzād Suhrābī in a still from the film The Wind Will Carry Us (Bād mā rā khvāhad burd), directed by ‛Abbās Kiyārustamī 1999.

Whenever Bihzād’s mobile phone rings, he has to drive to the cemetery on top of a hill overlooking the village to pick up his caller’s signal. (The first call he receives is from his family in Tehran, and we discover that by waiting for the old woman’s funeral, he’ll miss a funeral in his own family; all the subsequent calls are from his producer in Tehran.) At the same location he periodically chats with Yūsuf (another character in the film who is never seen), a young man digging a deep hole for unstated “telecommunications” purposes (most likely an antenna tower). Bihzād tells Yūsuf more than once how lucky he is not to be working under any boss, and after glimpsing the retreating figure of the digger’s 16-year-old fiancée, Zaynab, who brings him tea from time to time, Bihzād endeavors to meet her in the village by asking to buy some fresh milk from her family.

In the seven-minute title sequence, occurring roughly halfway through the film, Bihzād is directed to a cellar lit only by a hurricane lamp, where Zaynab obligingly milks a cow for him. Over the course of a long take from a stationary camera, Bihzād remains offscreen while Zaynab is filmed mainly from behind, though we can see her hands milking the cow. He idly flirts with her and casually remarks, “I’m one of Yūsuf’s friends — in fact, I’m his boss.” He also speaks to her somewhat condescendingly about Furūgh Farrukhzād. In between his comments and questions, to which she makes minimal responses, he recites one of Farrukhzād’s poems in full.

This is a sequence predicated on the arrogance of class privilege and assumed cultural superiority exerted by documentary filmmakers such as Kiyārustamī over his working-class subjects. Even though it’s centered on an Iranian poem, the rift between media and ordinarypeople is a universal theme rather than an Iranian one. The Iranian aspect of this theme, spelled out in much greater detail in Close-Up, is that in a culture without much economic mobility, filmmaking is one of the few professions in which a nobody can become a star. But I hasten to add that Iran is far from being the only country in which such a rift becomes operative. Theuniversality of class privilege is thus far more relevant to the ethics of The Wind Will Carry Us than the singularity of an Iranian poem.

Kiyārustamī’s shift from film to digital video after The Wind Will Carry Us had many ramifications for the remainder of his career. The fact that he was already a gallery artist thanks to his photography and painting made this a logical step and one that further removed his films from the industrial norms of commercial cinema, an arena he wouldn’t return to until a decade later, when he made Certified Copy. Thus, one might argue that the art world became a haven for Kiyārustamī’s experimentation in much the same way that the state funding of Kānūn had protected him earlier, regardless of whether the subject was the AIDS epidemic (in the 2001 ABC Africa) or nature (as in the 2003 Five). Ten (2002), a minimalist feature about a young woman (Māniyā Akbarī) driving in Tehran and her various passengers, was a transitional work insofar as it was both digital and narrative and was shown in some arthouse cinemas, but most of the other works during the first decade of the new millennium were “studies” shown in museums and galleries.

The first Kiyārustamī film to be reviewed in The New Yorker was Certified Copy. It was reviewed favourably by David Denby, who had previously disparaged Kiyārustamī’s work, and I suspect that it was the presence of Juliette Binoche as the female lead that led to this change of heart. It was likely the English dialogue as well as the presence of Binoche (who had already appeared briefly in Kiyārustamī’s 2008 Shīrīn) that made a positive review of a Kiyārustamī film in a mainstream magazine possible, despite the fact that it was in some ways even more radically subversive in its use of fictional narrative than any previous Kiyārustamī feature. Its plot concerns two strangers—an English author (William Shimell) and a French shop owner (Binoche)—meeting in Tuscany and driving to a nearby village, where they inexplicably turn into a quarreling married couple.

Kiyārustamī cast Shimell after having directed him two years earlier in a production of Mozart’s opera Cosi fan tutte in Aix-en-Provence. The fact that he took on such an assignment as an Italian opera already demonstrates the degree to which he had become a universal artist rather than simply or exclusively an Iranian one. Thus, it shouldn’t be too surprising that his oeuvre ends with the not-quite-finished 24 Frames (2017), which opens with the Bruegel painting Hunters in the Snow (1565) and concludes with a woman asleep beside a computer screen that has been showing the William Wyler film The Best Years of Our Lives (1946).

Figure 13: A still from the film 24 Frames, directed by ‛Abbās Kiyārustamī, 2017.

Considering the spread between a Dutch painting and a Hollywood movie four centuries later, or between an Italian village and Tokyo in Kiyārustamī’s last two fiction features, his elected turf was clearly the entire world and its history. Iran obviously was and is part of that world, but to restrict Kiyārustamī’s work to that part alone is to limit its relevance to all of us.

Cite this article

This article examines Abbas Kiarostami’s work through the lens of universality, exploring how his cinema transcends national, cultural, and linguistic boundaries while remaining deeply rooted in Iranian sensibilities. Tracing his evolution from early documentary work to internationally celebrated narrative films, the study highlights Kiarostami’s minimalist aesthetic, ethical ambiguity, and innovative use of non-professional actors as key elements contributing to his global resonance. Drawing on comparative analysis with neorealism, modernist cinema, and contemporary world cinema, the article situates Kiarostami not merely as a representative of Iranian filmmaking, but as an auteur whose thematic concerns—human resilience, moral complexity, the search for truth—speak across cultural divides. Through close readings of films such as Where Is the Friend’s Home?, Taste of Cherry, and Certified Copy, the paper argues that Kiarostami’s cinema constructs a poetic, open-ended form that invites universal engagement while remaining attentive to the textures of Iranian life. In doing so, Kiarostami redefines the possibilities of global authorship and challenges conventional categories of “national” cinema.