Accented Cinema: Muhsin Makhmalbāf’s Transnationalism

Introduction

Since the last decade of the 20th century, theoreticians, media experts, and film critics have analyzed movies through the lens of “nationality” and “transnationality.” An increasing number of books discuss this phenomenon: Transnational Chinese Cinemas: Identity, Nationhood, Gender (1997) by Sheldon Hsiao-Peng Lu, Transnational Cinema: The Film Reader (2006) by E. Ezra and T. Rowden, World Cinemas, Transnational Perspectives (2009) edited by N. Durovicová and K. Newman, and Transnational cinema: An introduction (2018) by S. Rawle. The concept began to develop in film studies in response to frequent collaboration between filmmakers, actors, cinematographers, and producers across borders of nation-states. This collaboration is evidenced by the etymology of the term “transnational cinema,” the first part of which derives its meaning from the Latin word trans meaning “behind,” “beyond,” or “from the other side.” Researchers of film transnationality define it based on various aspects: the director’s nationality, sources of production financing, the cast’s composition, and the location of filming.

The prevalence of transnational cinema is closely related to the broader phenomenon of transnationalism, a characteristic feature of globalization. The reduction of the role of state borders created a new social reality. As a result, the concept of “transnationalism” appeared in the lexicon of social sciences. Steven Vertovec defines it as a type of social formation extending beyond borders and a certain type of consciousness: individual, collective, multiplied, and diasporic. It emphasizes the multiple ties and practices connecting people, organizations, and institutions across national borders.1Steve Vertovec, Transnationalism (New York: Routledge 2009), 7.

Researchers studying the mechanisms of transcultural cinema often refer to the influential book Imagined Communities (first published in 1983), where Benedict Anderson defines national identity as a socially constructed community with a shared identity that exists in the minds of its members.2Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism (Verso, 2006). Since Anderson, the study of nationalism has been startlingly transformed in method, scale, and sophistication. In the English language alone, Ernest Gellner’s Nations and Nationalism (1983);

Anthony Smith’s The Ethnic Origins of Nations (1986); Partha Chatterjee’s Nationalist Thought and the Colonial World (1986), and Eric Hobsbawm’s Nations and Nationalism since 1780 (1990) — to name only a few of the key publications — have made the traditional literature largely obsolete. The American political scientist argues that nations are imagined because members of even the smallest nation will never know most of their fellow members, yet in the minds of each lives the image of their common nationality. Pointing at the cultural roots of nationalism, Anderson emphasizes that national identity is created through a shared sense of time, narratives, symbols, and media. All these factors allow people to imagine themselves as part of a larger community. This concept has been foundational in understanding how national identities form and evolve.

The growing number of transnational practices in film financing, production, and distribution has allowed film studies to broaden the definition of the national. “The Limiting Imagination of National Cinema” by Andrew Higson critically examines and analyzes various ways this title term is used. The problem Higson notices is that when describing national cinema there is a tendency to focus only on those films that narrate the nation as a finite, limited space inhabited by a tightly coherent and unified community, closed off to other identities.3Andrew Higson, “The limiting imagination of national cinema,” in Cinema and Nation, ed. Mette Hjort and S. MacKenzie (Psychology Press, 2000), 66. Higson also argues that the traditional notion of national cinema is often too narrow and Eurocentric, used prescriptively rather than descriptively, failing to account for the diversity and complexity of global cinemas. Revisiting Anderson’s idea of a modern nation as an “imagined community,” Higson notes that communities are often dispersed, diasporic, unstable, and changing.4Higson, “The limiting imagination of national cinema,” 63-64.

Is the increasing frequency of applying the term “transnational cinema” as a descriptive marker within film studies a sufficient response to the growing complexity of socio-cultural networks and the hybridization of identities? Will Higbee and Song Hwee Lim explore the evolving concept of transnational cinema, arguing that this theoretical notion also requires a critical approach. They notice that the term “transnational cinema” also tends to be taken as a given—used as shorthand for an international or supranational mode of film production where the impact and reach lie beyond the bounds of the nation. The danger here is that the national becomes negated in such analysis, as if it ceases to exist, when in fact the national continues to exert the force of its presence even within transnational film-making practices. Moreover, the authors point out that the term “‘transnational”‘ often indicates international co-production between technical and artistic personnel worldwide, without any real consideration of the aesthetic or political implications of such collaboration.5Will Higbee, and Song Hwee Lim, “Concepts of transnational cinema: towards a critical transnationalism in film studies,” Transnational Cinemas 1, no. 1 (2010): 10. They highlight the liberating and limiting aspects of the term “transnational cinema” and advocate for a more inclusive approach considering diverse cinematic traditions, for instance from Asia or Africa.

Taking this diversity into account allows us to better appreciate the unique nature of the development of cinema in Iran. In the first decades, domestic cinema developed thanks to the international travel of Persian rulers and representatives of Iranian elites, as well as close contacts with neighboring Indian cinematography. ‛Abdalhusayn Sipantā, the first Iranian director to start making sound films for the domestic market, shot all five of his films in India. Most of the other pioneers of Iranian cinema (Ibrāhīm Murādī, Uvānis Uhāniyān, Ismā‛īl Kūshān) traveled to Europe or Russia, learning the skills of cinematography, directing, or producing. After World War II, many Iranians temporarily migrated to Europe and the United States to study at film schools. A milestone in the transcultural tendency of Iranian cinema was the mass exodus of Iranian directors, actors, and especially actresses after the revolution, during the prolonged war with Iraq (1980–1988). Later migrations occurred as a consequence of the further economic, political, and social difficulties that Iranians experienced under the new regime. The waves of migration resulted in the formation of diasporas of Iranians in their new, adopted homelands.

Contemporary Iranian filmmakers on the new map of world cinema

It is not uncommon for Iranian filmmakers today to work abroad—whether occasionally, or permanently. They often leave their homeland tired of fighting against the powerful (while also often vague) censorship restrictions that apply at every stage of film production. A prime example of such a situation is the creative path of Muhsin Makhmalbāf, a director who initially supported the ideology of the Islamic Republic of Iran, but over time came into conflict with the regime and became an opposition artist. Because the production of his scripts was suspended due to censorship, Makhmalbāf left his homeland in 2000 to continue making films. Since then, he has made films in Afghanistan (Kandahar/Safar-i Qandahār, 2001), Tajikistan (Sex and Philosophy/Siks-u-Falsafah, 2005) and India (Scream of the Ants /Faryād-i Mūrchah-hā, 2006).

Figure 1: A still from Scream of the Ants (Faryād-i Mūrchah-hā, 2006), directed by Muhsin Makhmalbāf. Photo by Marzieh Meshkini, accessed via https://Makhmalbaf.com/?q=Photo-Gallery/scream-of-the-ants-photo-gallery.

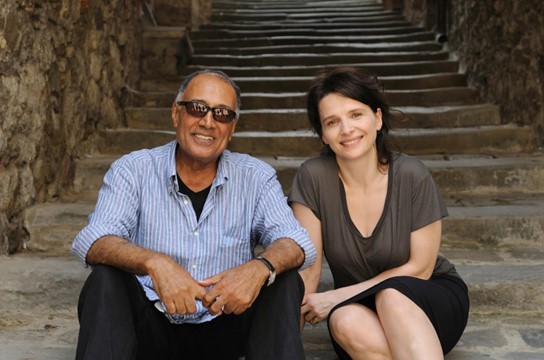

The reasons why Iranian directors make films outside Iran are not always due to censorship restrictions. Sometimes they are looking for inspiration from outside the local cultural circle, e.g. fascination with the Italian landscape in ‛Abbās Kiyārustamī’s film Notes from Tuscany (Copie conforme, 2010), the French-Italian-Belgian co-production. Another example is Kiyārustamī’s interest in Japanese culture in Like Someone in Love (Raiku samuwan in rabu, 2012), a French-Japanese co-production, that takes place in Tokyo. Other examples of non-Iranian settings and actors are found in Asghar Farhādī’s movies. He decided to make Le Passé (The Past, 2013) in Paris, where he found a location where the past feels present in space and atmosphere. Todos lo saben (Everybody Knows, 2018) takes place in Spain because Farhādī was intrigued by photos of a missing boy while traveling in the south of the country.

Figure 2: ‛Abbās Kiyārustamī and Juliette Binoche on the set of the movie Notes from Tuscany (Copie conforme, 2010), accessed via https://www.filmaffinity.com/us/movieimage.php?imageId=946670414.

Figure 3: A still from Todos lo saben (Everybody Knows, 2018), directed by Asghar Farhādī.

Hamid Naficy is reluctant to employ the term “transnational,” preferring to think of these films and filmmakers as “international.” Similarly, when searching for a term to describe the shared aesthetics created by displaced filmmakers, Naficy settles on “accented cinema,” distancing from his earlier formulation of “independent transnational genre.”6Hamid Naficy, “Theorizing” Third-World” Film Spectatorship,” Wide Angle 18.4 (1996): 3-26. Suppose, for example, that the dominant cinema in each country and the dominant world cinema, that of Hollywood, are considered to have no “accent.” In that case, the films produced by displaced directors are considered “accented.” This adjective, however, does not refer to the speech of the diegetic characters but to the narrative and stylistic attributes of such films and their alternative collective modes of production.7Hamid Naficy, An Accented Cinema: Exilic and Diasporic Filmmaking (Princeton UP, 2001), 4. Iranian films made abroad are part of a new global “accented cinema” created by displaced filmmakers. According to Naficy, despite their many differences, such filmmakers’ work shares certain features, which constitute their films’ “accent.”8Naficy, An Accented Cinema: Exilic and Diasporic Filmmaking, 4-5. Writing about the post-revolutionary Iranian filmmakers, he differentiates five types of displaced artists to account for the complexity and nuances of their displacement and the variety of the accented films they produce. He distinguishes the following categories of directors: exilic, diasporic, émigré, ethnic, and cosmopolitan.9Hamid Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema, Volume 4: The Globalizing Era, 1984–2010 (Duke University Press, 2020), 393. As the product of individual filmmakers working under conditions of artistic independence, Iranian accented cinema deals primarily with individual subjectivity often having autobiographical narratives. It explores various identities other than national, including ethnic, cultural, social, gender, and ideological identities. The variety of forms and types of films displaced Iranian makers produce and how these works are disseminated (namely, online), underscore their postmodernity.10Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema, Volume 4, 370-371. This article unpacks the features of “accented cinema” in Muhsin Makhmalbāf’s movies, while also analyzing the transnational storytelling and identity issues that were trademarks of his artistic creativity long before his emigration.

The Belated Sensuality and New Sensibility

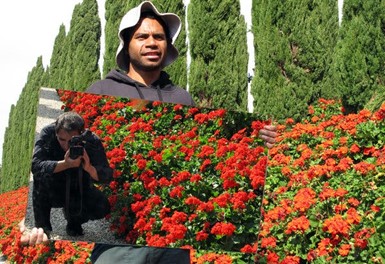

A growing shadow gradually obscures the sun. A group of women in burqas is moving slowly through the vast, barren desert. The silhouette of a rider looms on the slope of the snow-covered hills, and the howl of a wolf pierces the empty, cold space. The babbling stream carries flowers and balls of colorful wool downstream. Colorful carpets dry on dazzling white limestone, and in the background, we hear the sounds of sheep and bells. A blind boy listens to the buzzing of a bee, guessing what it is sitting on. Men gathered in the bazaar tap out the sounds of Beethoven’s 5th Symphony on brass kettledrums. A man holding a large mirror walks across the garden reflecting red flower beds.

Figure 4: A still from Gabbah (1996) by Muhsin Makhmalbāf, accessed via: https://watch.plex.tv/movie/gabbeh.

Figure 5: A still from Kandahar (Safar-i Qandahār, 2001), directed by Muhsin Makhmalbāf, accessed via: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=H_KBdU0lXes.

Sometimes the shots in Makhmalbāf’s movies appeal to senses other than sight. The recipient of such directed shots is certainly not just a viewer; perception also activates other senses. The sensual saturation of these shots intensifies their impact to such an extent that as a viewer I often experience them as autonomous film units, not feeling the need to arrange them in a causal order. The specific independence of these scenes or shots is a bit surprising, given that (as compared to in Europe) visual art did not have a major influence on the development of Iranian film aesthetics.

Verbal narration in the form of naqqalī tradition—one-person recitations of rhythmic prose—had a much greater impact on cinema. This was noticed by Makhmalbāf himself: “We have passed directly from the story to the cinema.”11Nader Takmil-Homayoun, Iran: A Cinematographic Revolution (Iran: Icarus Films, 2006). In the filmmaker’s opinion, it was perhaps this lack of the burden of visual arts tradition that made Iranian filmmakers have a fresh approach and gave them the potential to create simple and at the same time sensual images with a high impact.

In the Warsaw International Film Festival program from 1999, where Makhmalbāf’s fifteenth feature film Silence (Sukūt, 1998) was shown, we read: “There is no more lyrical, poetic and artful voice in cinema than that of Mohsen Makhmalbaf.”12“The Silence,” Warsaw International Film Festival, 10-19 October 2025, accessed December 28, 2024, https://wff.pl/en/film/1999-sokout If one attempted to apply the above statement to the director’s first propaganda films such as Two Feeble Eyes (Du Chashm-i Bīsū, 1984), which promotes Islamic values, or the anti-communist Boycott (Bāykut, 1985), with its ideologically and technically simplified plot, one may get the impression that we are talking about a completely different director.

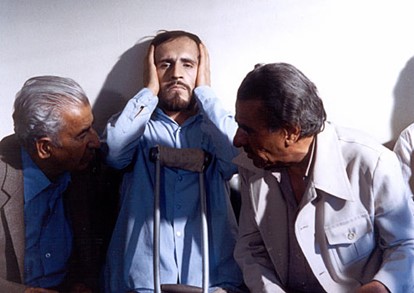

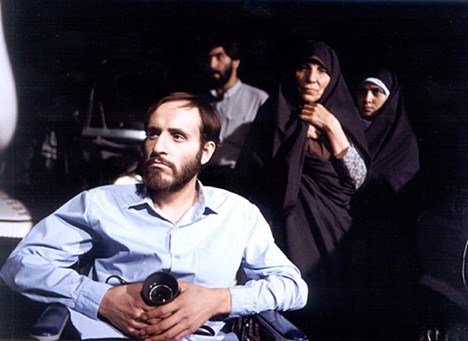

Since the late 1980s, Makhmalbāf has brought in other perspectives within his movies, introduced innovations giving voice to marginalized characters, and moved away from the cause-and-effect narrative in favor of a polyphonic narrative or one based on an aesthetic leitmotif. The movie heralding these changes is Marriage of the Blessed (‛Arūsī-i Khūbān, 1988)—a dramatic portrait of Hājī (Mahmūd Bīgham), a photojournalist and veteran of the Iran-Iraq War, struggling to reintegrate into civilian life. His trauma is vividly conveyed through the film’s aesthetic choices. The director goes beyond the Shiite paradigm of a martyr for the faith (shahīd) promoted by the Islamic Republic of Iran. Instead of following the national rhetoric, the film accentuates a universal theme: a connection between perception, the human body, and “the vision machine” (Paul Virilio’s term) represented in this case by the camera.

Figure 6: A still from Marriage of the Blessed (‛Arūsī-i Khūbān, 1988), directed by Muhsin Makhmalbāf, accessed via https://www.Makhmalbaf.com/?q=Photo-Gallery/marriage-of-the-blessed-photo-gallery.

Despite undergoing treatment in a mental hospital, Hājī is unable to function in the post-war reality. After traumatic experiences, his senses are so overloaded that the most ordinary stimuli come unexpectedly and trigger panic or aggression as a form of self-defense. The prolonged insistent noises of typewriters evoke such strong reminiscences of the Iraqi army attack that Hājī counterattacks the enemy by “shooting” with an orthopedic bullet. The hero’s heightened sensual sensitivity deepens his social sensitivity. The viewer experiences the protagonist’s sensitivity through a combination of intense visual and narrative techniques. The film uses surreal and symbolic imagery to reflect Hājī’s inner turmoil. For example, flashbacks to the battlefield are interwoven with unsettling visuals, such as a typewriter in the foreground of a war scene or dismembered limbs, emphasizing the psychological scars of war. Another example is the scene where Hājī fiancée Mihrī (Ruyā Nawnahālī) walks into a room carrying a plate of pomegranate seeds, and is frightened by a pigeon released in front of her, causing her to spill the tray and triggering a splash of the red color evoking blood and violence. The film juxtaposes moments of clinical realism, such as scenes in a hospital for war veterans, with poetic and symbolic sequences. This contrast draws the viewer into Hājī’s heightened emotional state, oscillating between despair and fleeting moments of hope. His state is also emphasized by dynamic camera work: Makhmalbāf employs wide-angle lenses, moving camera shots, and shifts between color and black-and-white to create a disorienting and immersive experience. These techniques mirror Hājī’s fragmented perception of reality and his struggle to reconcile his past with the present and through them, the viewer is drawn into the veteran’s perspective.

As a professional photographer hired by a local newspaper, Hājī records the grim reality of the poor inhabitants of Tehran, whose existence the editor wants to deny as too pessimistic. Makhmalbāf gestures towards the transnational, juxtaposing images of local poverty with the television’s snapshots of famine in Africa. The director’s storytelling shows the dissonance between the hero’s private experience, based on his senses, and the public space appropriated through visual propaganda and its slogans calling Iranian men to fight.

Figure 7: A still from Marriage of the Blessed (‛Arūsī-i Khūbān, 1988), directed by Muhsin Makhmalbāf, accessed via https://www.Makhmalbaf.com/?q=Photo-Gallery/marriage-of-the-blessed-photo-gallery.

In Makhmalbāf’s early films, made in the early 1980s for the Islamic Art and Thought Center at the Islamic Propaganda Organization, reality is presented from the perspective of an ideologically committed male protagonist. Beginning with Marriage of the Blessed, the filmmaker moved away from theological and nationalistic ideas, instead emphasizing human autonomy within his phenomenological style of viewing and describing what directly appears.13The Greek word phainomenon means “that which appears.” Sensual subjectivity, and the potential deceptiveness of perception, become the main theme of A Moment of Innocence (Nūn va Guldūn, 1995), which is one of the director’s most personal works.

After this breakthrough, a change in narrative perspective took place. It manifested in the transition to alternative perspectives of showing the diegetic world through the prism of women, children, or underprivileged men, such as the poor Afghan refugee Nasīm in The Cyclist (Bāysīkilrān, 1988). Characters’ identities are defined less by specific nationality and its ethos and more by categories such as ethnicity, social class, economic class, gender, generational affiliation, and religion. This change in content is inextricable from the change in filming style.

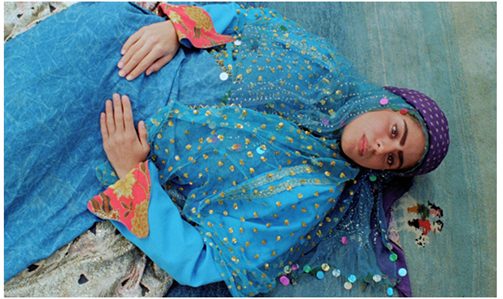

A Diary Written with a Thread of Wool

Makhmalbāf’s poetic and sensual sensitivity manifested with full intensity in his movie Gabbah. The French company MK2, led by Marin Karmitz—a producer and distributor specializing in artistic cinema—participated in its production. The Iranian-French coproduction premiered in 1996 in the Un Certain Regard section at the Cannes Film Festival and subsequently was released in 23 cities in France and Switzerland. It was the first time an Iranian film had such a wide international release. On the official website of the Makhmalbāf family Gabbah is described as a “brilliantly colorful, profoundly romantic ode to beauty, nature, love and art.”14“Mohsen’s Films,” Makhmalbaf Film House, accessed January 03.2025, https://www.Makhmalbaf.com/?q=Mohsen-Films Indeed, the film is primarily a lyrical vision of the nomadic life of the Qashqāʾī people who inhabit the southeastern regions of Iran; most were originally nomadic pastoralists and some remain so today. They migrate over long distances, moving twice a year between winter pastures near the Persian Gulf and summer pastures in the Zagros Mountains.15Lois Beck, Nomad. A Year in the Life of a Qashqa’i Tribesman in Iran (London, 1991), 12. For centuries, these wandering families created unique rugs—gabbah—that served not only as a form of artistic expression but also as autobiographical records of the lives of the weavers.16Due to its unique characteristics, a gabbah is not a typical carpet. It differs in having a smaller size, greater thickness, surface texture, and a manufacturing method based on ancient techniques. Spellbound by the tales behind the gabbahs, what began for Makhmalbāf as a documentary evolved into a fictional love story that uses a rug as a magic storytelling device weaving past and present’ fantasy and reality. The director moves away from the politicized context of Shiism in favor of the multi-ethnic, cultural heritage of Iran and transnational Islamic philosophy. This transgression takes place from the perspective of a young woman—the protagonist of the film—named Gabbah (played by Shaqāyiq Judat) from the Qashqāʾī tribe. The close, almost organic connection of the protagonist with the titular rug is manifested in the way she appears on screen. The woman miraculously emerges from the weaves of the gabbah lying on the ground, freshly washed by an elderly couple, announcing that her father’s name is “Ball of Wool.” The protagonist is thus an anthropomorphization of the gabbah itself, whose name she bears, and at the same time the narrator of the film’s story. The drama of the plot arises from the tension between traditional tribal customs and the romantic love of the protagonist. Gabbah experiences romantic turmoil due to the impossibility of fulfilling her feelings for the mysterious rider on the horizon, who follows her clan. She must wait for the opportunity to marry her beloved until—according to custom—her uncle, who has been living in the city for years, gets married. The separated lovers communicate through the voices of animals.

Figure 8: A still from Gabbah (1996), directed by Muhsin Makhmalbāf, accessed via https://watch.plex.tv/movie/gabbeh.

It is also possible to read the character of Gabbah as a manifestation of color; the significance of color is explicitly expressed not only by the visual aspects of the movie but also by the statements in the dialogue. Weaving girls exclaim: “Life is color! Love is color! Man is color! Woman is color! Love is color! Child is color!”17“Script Gabbeh,” Makhmalbaf Film House, accessed January 03.2025, https://Makhmalbaf.com/?q=node/797/ The director presents the sensual perception of the world as the beginning of everything and the initial condition for the creation process. The indication of this dependency is particularly clear in the scene where the protagonist’s uncle—a wandering teacher—teaches the Qashqāʾī children about the primary colors and then explains the mechanism of creating secondary colors. This performative lesson in the outdoor school also has a supernatural dimension, considering the magical way the teacher’s hands are covered in colors. This scene is also a tribute to God as the creator of reality and the source of colors. It is also worth noting that the word “color” in Persian has another special meaning. The word “rang” usually also refers to “way/style (of existence or behavior).” The Quranic reference to the “color” of God thus denotes the way of God’s existence, His spiritual form.18Shaul Shaked, From Zoroastrian Iran to Islam. Studies in Religious History and Intercultural Contacts, (Aldershot – Brookfield, VT 1995) 41. In seeking God, Makhmalbāf departs from the concept of personal jihad, instead following the perceptible divine signs in nature. He does this by following in the footsteps of Iranian nomads, who—due to their way of life—remain close to the miracle of divine creation.

According to tradition, the patterns visible on a Gabbah depicted specific events from the family’s history. This is also the case here: the rug woven in the film is a main tool of storytelling; it illustrates the story of the main character and reveals its ending. The very first shot is a kind of futurospection, manifested using woollen yarn. A Gabbah flows with the swift current of a mountain stream. The camera focuses on its detail—a woman and a man riding together on a white horse. The waves of clear water flowing over the fabric seem to animate the motionless figures. The significance of this motif is explained only in the film’s ending. The girl wishes to escape with her beloved against her father’s will. The father follows her with a weapon, and when he returns, he announces to the family that he has shot his daughter. However, the rug shows two lovers happily escaping.

The director shows the process of recording important events in statu nascendi through parallel editing of shots leading to the tragic event in the film family’s life and shots in which we see the weaving of subsequent parts of the rug. Shu‛lah—Gabbah’s younger sister—follows a lost goat into the mountains, which she finds on the edge of a precipice. The film does not show the girl’s accident but suggests it through a black ball of wool, which in the next shot flows with the stream and is then thrown onto the loom and incorporated into the fabric as a symbol of death. This sequence is accompanied by dramatic symphonic music using the interval of a minor second, which is usually used to build tension. The mournful female singing we hear while seeing the lonely return of the goat to the herd and the man digging a grave leaves no doubt about the child’s fate. The director’s original form of narration through sensory experiences combines the oldest art of Persia, weaving, with the youngest of the arts, film. The key activity of weaving in Gabbah brings to mind the metaphor of text as fabric and the figure of the weaver, which is almost an emblematic representation of the woman-artist. The film offers an analogy between the act of spinning and female narration, language, and history. Second-wave feminists made weaving more than just another metaphor for writing, transforming it into a kind of genesis myth of women’s art, different from male creation both in terms of inspiration and language of expression. Referring to the myth of Arachne, Nancy Miller adds a sense of nobility to female creative subjectivity and the feminine sources of art. According to Miller, there is a key distinction between weaving—the artistic creation of images—and spinning, which does not entail representation.19Nancy K. Miller, “4. Arachnologies. The Woman, the Text, and the Critic,” in Subject to Change. Reading Feminist Writing (New York, NY 1988), 77-101. In Makhmalbāf’s film, the former model of female expression dominates. The gabbah woven by women are an interesting blend of representations of the external and internal: nature, the life of the tribe, as well as the autobiography and emotions of the weavers.

Figure 9: A still from Gabbah (1996), directed by Muhsin Makhmalbāf, accessed via https://watch.plex.tv/movie/gabbeh.

The dramatic fate of the nomadic tribes in Iran could provide excellent material for a socially engaged and critical film to work against institutionalized centralization. In the early 1900s, as much as 25% of the country’s population consisted of nomadic tribes. Beginning in 1925 the new monarch—Rizā Shah Pahlavī—began to dismantle the centuries-old nomadic communities, prohibiting them from moving between their summer and winter habitats. This led to forced settlement and the decimation of entire tribes. However, despite the extensive historical record concerning the planned extermination of Iranian nomads, Gabbah (unlike the director’s earlier works) is entirely devoid of political accents. Adopting the perspective of the female protagonist, the artist fully devotes himself to meditating on color. The cinematography by Iranian operator Mahmūd Kalārī, through the play of light, brings out and emphasizes the shades, textures of liquid and solid bodies—the softness of animal fur, the fluffiness of freshly cut wool, the roughness of the warp on the looms, the weight of yarn soaked in dye, the violent current of the river, and the cold of snow. The filming technique gives the images a sensual intensity, accompanied by equally intense effects on the viewer’s sense of hearing. Already in the opening credits, attention is drawn to the loud, rhythmic sound of heavy scissors (as it turns out later—cutting wool) accompanying the opening titles.

The lyrical romanticism of Gabbah, distanced from the daily problems still faced by Iranian nomads, met with disapproval from some experts, who stated that the film is far from the realities of tribal life.20Jean-Pierre Digard, and Carol Bier, “Gabba” in Encyclopaedia Iranica Online, Originally Published: December 15, 2000, Last Updated: February 2, 2012, accessed March 17, 2025,

https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/gabba- However, in most cases, the director’s change of strategy, this time focusing on the beauty of nature, human feelings, sensory perception, and creativity, was met with applause. Gabbah received five international awards, among others – Best Artistic Contribution Award at 9th Tokyo International Film Festival (1996) and Best Asian Feature Film at Singapore International Film Festival (Singapore, 1997).21Tokyo International Film Festival – the list of awards, accessed March 19.2025, Tokyo International Film Festival (1996) – IMDb Singapore International Film Festival – the list of awards, accessed March 19.2025, Singapore International Film Festival (1997) – IMDb In 1996, reviewers of the American edition of Times recognized Makhmalbāf’s work as one of the top 10 films of the year.22“Gabbeh,” Makhmalbaf Film House, accessed January 03.2025, https://www.makhmalbaf.com/?q=film/gabbeh

Silence or Symphony of the Senses?

While in Gabbah the essence of life, creativity, and film storytelling is color, in Makhmalbāf’s next film—paradoxically titled Silence (Sukūt, 1998)—the essence is sound. The film is the first work of the director’s private production company, Makhmalbāf Film House, and a renewed collaboration with Marin Karmitz (MK2). Set in Tajikistan, the film tells the story of a blind boy named Khurshīd (interestingly, played by a Tajik girl: Tahmineh Normatova), who is raised by a single mother. The family struggles with financial problems, as the only source of income is Khurshīd’s work in a workshop producing musical instruments. His exceptional sensitivity to sounds, likely resulting from his lack of vision, helps him fulfill his duties as a tuner of instruments, but sometimes gets in the way of his physical movement through space. His love for melodious sounds causes him to follow them and sometimes makes him late for work. For this reason, when he rides the bus, he plugs his ears with cotton balls to avoid being lured by the music and getting off at the wrong stop. Khurshīd primarily lives in a world of auditory sensations, picking up the same rhythmic sequences from various sound sources. Both the knocking on the wooden door by an impatient landlord and the sounds of craftsmen making brass vessels sound to him like music. The movie viewer familiar with classical music will recognize the motif from Beethoven’s 5th Symphony. Khurshīd tries to retain and reproduce the recurring motif in his memory. This piece was, apparently, the first Western composition the director ever heard, which is likely why it features in the soundtrack.23I noted this information during the public meeting with Makhmalbāf in Kraków, which took place in November 2008, as part of the 15th Etiuda&Anima International Film Festival. The dominance of auditory impressions in the protagonist’s perception makes hearing his primary sense, and sounds determine all his choices—from the direction he takes to what he buys to eat—and by extension the film’s storytelling.

Figure 10: A still from Silence (Sukūt, 1998), directed by Muhsin Makhmalbāf, accessed via https://Makhmalbaf.com/?q=Photo-Gallery/silence-photo-gallery.

Figure 11: A still from Silence (Sukūt, 1998), directed by Muhsin Makhmalbāf, accessed via https://Makhmalbaf.com/?q=Photo-Gallery/silence-photo-gallery.

Silence introduces the audience to the perceptual world of the blind protagonist in various ways. One is the noticeable intensification and sometimes even hyperbolization of selected sound effects, such as the buzzing of a bee, which in ordinary perception are relegated to the background and rarely reach the status of stimuli. Another strategy the director uses is apparent in the bus scene. When the boy plugs his ears with his fingers, complete silence falls, only interrupted by the removal of his fingers. Considering that acoustics serve not only as a carrier of information but also—in both a metaphorical and literal sense—as an anchor for the viewer’s body in space, this directorial technique is crucial for any attempts to identify with the protagonist. This scene also proves that the ear allows the film experience to root itself inside the viewer. Moreover, focusing attention on this organ means the viewer cannot be merely a passive receiver of images, but rather an embodied being, acoustically, spatially, and affectively entangled in the texture of the film.

A similar strategy is employed by Makhmalbāf in the scene where Khurshīd’s guide is taken over by the teenage Nādirah (Nadira Abdullaeva). When the boy gets lost while following a melody coming from a tape recorder, the girl tries to find him. When her frantic search in the crowd at the market doesn’t yield results, Nādirah decides to close her eyes, listen to the surrounding sounds, and catch the music. Extending her hands forward, she follows the melody and soon reaches its source: a group of street musicians playing in the square. By doing so, she also finds Khurshīd. This method of sensory navigation further immerses the audience into Khurshīd’s world, highlighting the importance of sound in the film, and creates a deep connection between the audience and the characters.

Filled with the beauty of nature and Tajikistan’s folklore, Silence further emphasize Khurshīd’s perceptual limitations. The viewer is aware that this stunning array of colors and shapes is inaccessible to the film’s protagonist. Nevertheless, Makhmalbāf focuses on exploring the realm of multisensory sensations, both for the viewer and for the protagonist. The inability to see helps to concentrate on being present in the here and now. Rational knowledge, which primarily relies on the eye, gives way to auditory contemplation and experience.

By the 1990s, Muhsin Makhmalbāf was an international director, making films within the framework of the production company he founded in 1996, Makhmalbāf Film House. At the same time, most of his films—such as Kandahar (Safar-i Qandahār 2001)—were made in the Middle East and Central Asia, and still referred to his personal history and experiences. In these films, the artist does not openly question the patriarchal culture, but his characters blur clear boundaries of male and female roles and the categories of childhood and adulthood; these choices raised concerns from the fundamentalist censors. Makhmalbāf’s nuanced approach to challenging traditional roles and exploring diverse models of identity adds complexity to his films and provides a subtle critique of societal norms. For example, in Kandahar, Afghan expatriate Nafas (Nilofer Pazira playing herself), travels from Canada to Kandahar and secretly records commentary on her journey on a dictaphone, which emphasizes the importance of the female narrative.

Figure 12: A still from Kandahar (Safar-i Qandahār, 2001), directed by Muhsin Makhmalbāf, accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=H_KBdU0lXes.

After six of his movies were banned, Makhmalbāf gradually moved beyond mere criticism to actively opposing the regime. In the late 1990s, the rebellious filmmaker gained the status of a political dissident, and in 2005, following Mahmūd Ahmadīnizhād’s election as president, he permanently left Iran.

Transnational par excellence: The Gardener

Muhsin Makhmalbāf broke free from the censorship of the Islamic Republic, and from self-censorship, gaining access to an unlimited array of thematic possibilities, and the ability to push the boundaries of storytelling. The most thought-provoking result of this creative freedom is perhaps his most recent documentary film, The Gardener (Bāghbān, 2012), which combines Makhmalbāf’s strong social commitment and activism with a poetic perception of reality. The choice of location—Israel—is itself a major transgression for an Iranian director. Since 1979, the Islamic Republic of Iran and Israel have had no diplomatic relations. As a result, Iranian citizens are generally not allowed to travel to Israel.24The new Islamic Republic of Iran did not recognize the legitimacy of Israel, which marked the beginning of a period of open hostility between the two countries. Makhmalbāf and his team will be automatically sentenced to five years in prison should they ever return to Iran.

The Gardener is also Makhmalbāf’s most controversial film because of its subject matter. The director and his son Maysam traveled to Israel to investigate the Baháʼí Faith—both its principles, and the current situation faced by its believers.25The Baháʼí Faith is variously described as a religion, sect, relatively new religion, and new religious movement. The world’s youngest independent monotheistic religion, the Baháʼí Faith originated in 1844 in the city of Shiraz in southwest Iran. Just as Christianity grew out of messianic expectations for Judaism, the Baháʼí Faith grew out of tensions in the Islamic world. A merchant named Sayyid ‛Alī Muhammad Shīrāzī, later known as “The Báb” (“the Gate”) took eighteen Shaykhīs Muslims as his disciples. The Báb began preaching that he was the bearer of a new revelation from God. He taught that God would soon send a new messenger, and Baháʼís consider an Iranian religious leader Baháʼu’lláh to be that person. Baháʼu’lláh declared himself the latest in a line of prophets, including Abraham, Moses, Buddha, Jesus, and Muhammad. The movement has faced ongoing persecution since its inception. It has been met with much official resistance from Qājār rulers and clerical authorities, as it recruited new adherents and became a significant insurgency. The initial rise of the movement ended with the Báb’s public execution for the crime of heresy.26Friedrich W. Affolter, “The specter of ideological genocide: The Baha’is of Iran,” War Crimes Genocide & Crimes against Human 1 (2005), 75. The Baháʼí community was mostly confined to the Persian and Ottoman empires until the end of the 19th century, after which it gained followers in Asia and Africa. By the early 20th century, the religion had established a presence in Europe, North America, and other regions.

The Baháʼí teachings emphasize the essential spiritual unity of the world’s major religions. It can be observed that the Baha’i Faith combines, among others, elements of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. Religious history is considered orderly, unified, and progressive from one age to the next.27Peter Smith, An introduction to the Baha’i faith (Cambridge University Press, 2008), 108-109. Three fundamental principles form the foundation of Bahá’í teachings and doctrine: the unity of God, the unity and essential worth of all religions, and the unity of humanity.28Manfred Hutter, “Bahā’īs,” in Encyclopedia of Religion, ed. Lindsay Jones, 2nd ed. (Detroit: Macmillan Reference USA, 2005), 737-740. Other principles advocate “peace, universal education, and equality of all human beings regardless of race, ethnicity, gender, or social class.”29William Garlington, The Baha’i Faith in America (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2008), 24.

These theological, social, and spiritual ideas based on Love and Unity continue to attract followers worldwide. The Bahá’í community continues to grow, with an estimated 5-8 million adherents worldwide as of 2024.30In 1948, the Bahá’í International Community (BIC) was first chartered with the United Nations, and it has since gained consultative status with various UN agencies. The Bahá’í community continues to grow, with an estimated 5-8 million adherents worldwide as of 2024. At the same time, Baháʼís continues to be persecuted in some majority-Islamic countries, whose leaders do not recognize the Baháʼí Faith as an independent religion, but rather heresy. Paradoxically, the most enduring persecution of Baháʼís has been in Iran, the birthplace of the religion.31Paula Hartz, Baha’i Faith (New York: Infobase Publishing, 2009), 11. Since its beginning, the new religious movement has been treated by Iranian religious authorities as an apostasy from Islam and from the state religion of Shiism.32See Peter B. Clarke, ed., “Baha’i,” in Encyclopedia of New Religious Movements (London and New York: Routledge, 2006), 56. In Gardener, Muhsin Makhmalbāf openly points out the contradiction between Article 18 of the Declaration of Human Rights, giving each person the right to choose a religion, accepted by the Iranian government, and its actual policies, which have persecuted the Baháʼí community in Iran before and after the 1979 Revolution.33Shahrough Akhavi, Religion and Politics in Contemporary Iran: Clergy-State Relations in the Pahlavi Period (Albany, NY: SUNY Press, 1980), 76-78. The government claims that the Baháʼí Faith is not a minority religion, but is instead a political organization.34Marc Kravetz, Irano Nox (Paris: Grasset, 1982), 237. As a result, hundreds of thousands of Islamic Republic citizens who have chosen the Baháʼí Faith have been deprived of their rights.35“The Gardener,” Makhmalbaf Film House, accessed January 03.2025, https://www.Makhmalbaf.com/?q=film/the-gardener They are often arrested, sent to prison, and even executed. They are not allowed to gather as a community, receive higher education, and work in government offices. Their cemeteries are destroyed and property has been seized and occasionally demolished.36Friedrich W. Affolter, “The Specter of Ideological Genocide: The Baháʼís of Iran,” War Crimes, Genocide, & Crimes Against Humanity 1, no. 1 (January 2005): 75-114. The rights of Baháʼís have also been restricted (to a greater or lesser extent) in numerous other countries, including Egypt, Afghanistan, Indonesia, Iraq, Morocco, Yemen, and several countries in sub-Saharan Africa.37Peter Smith and Moojan Momen, The Bahá’í Faith 1957-1988: A Survey of Contemporary Developments, Religion (1989): 63–91.

Why did Muhsin Makhmalbāf decide to come to Israel’s third-largest city— Haifa— to make a movie about the Baháʼí community? The city is home to the Bahá’í World Centre, which includes the administrative center for the international Bahá’í community, the Shrine of the Báb, the Terrace Gardens (opened to the public in 2001), and other key sites centered on Mt. Carmel.38Haifa’s connection with the Baháʼí began in the late 1800s. see Jay D. Gatrell and Noga Collins-Kreiner, “Negotiated Space: Tourists, Pilgrims, and the Bahá’í Terraced Gardens in Haifa,” Geoforum 37, no. 5 (2006): 765-778. For the Baháʼís, Mt. Carmel was of singular importance when Bahá’u’lláh—the prophet and leader— stood on its slopes in 1891 and sketched his plans for the development of the spiritual and administrative core of the new religion. At the center of the Mt. Carmel complex, Bahá’u’lláh selected the site for a mausoleum to be constructed to hold the remains of the Báb—the founder of the faith. The original mausoleum was constructed in 1909, and since then, the Bahá’ís have maintained a permanent presence on the mountain. Farīburz Sahbā began working in 1987, designing the gardens and overseeing construction. The terraces were opened to the public in June 2001. In 2008 The Gardener set was recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. It includes not only the gardens but also the Baháʼí World Centre buildings in Haifa and Western Galilee.39“Three new sites inscribed on UNESCO’s World Heritage List,” UNESCO, July 8, 2008, accessed January 03, 2025, https://whc.unesco.org/en/news/452 The Bahá’í connection to Mt. Carmel is based (in part) on the historical narrative surrounding Mt. Carmel and the belief of Jews and Christians that Mount Carmel is the “Mountain of the Lord.” Mount Carmel was known to the ancient Hebrews as a symbol of fruitfulness and prosperity. Following a long period of deforestation, during which it turned into a dry, rocky landscape, it has regained its former verdure and beauty in the form of the Terrace Gardens. Once again, it embodies its Hebrew name, “kerem-el,” meaning “vineyard of the Lord.”

The director intended to come to Haifa with his son to make a movie about the Baháʼí faith and the tragic fate of its adherents in some countries. In his monologue, he expresses hope that this movie will raise awareness about this religious movement and change the situation: “Perhaps our not knowing has contributed to the cruelties committed against Baháʼí.”40Muhsin Makhmalbāf, The Gardener (2012), 0: 2: 03. TIMESTAMP https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LIR3QAkIKT8

The subject of the movie makes the narrative of The Gardener transnational par excellence. The Baháʼí religion is based on global identity, embracing the idea of “a world citizen.” Adherents view themselves as united by the universal belief that transcends national boundaries. The film’s location itself—the Baháʼí Gardens in Haifa and the historic center of Jerusalem—also makes the narrative transnational, as the settings are neither homogeneous in their culture nor ethnicity. Rather, they represent a blending of religion and nationality. However, there is also a difference between these two “zones of diversity.” The diversity of Jerusalem is determined by its turbulent history. Over millennia, the city has been influenced by various civilizations, including the Israelites, Romans, Byzantines, Arabs, Crusaders, Ottomans, and British. These layers of history contribute to its rich and diverse cultural heritage. In the case of gardens on Mt. Carmel, promoting the interconnectedness of all people, was the planned, foundational idea, which is reflected in the gardens’ design and purpose. The very choice of the site was thoughtful; Mount Carmel, where the gardens are located, holds significance in multiple religious traditions and has an interfaith character because of its story. Another important aspect is global collaboration. The construction and maintenance of the gardens involved contributions from Baháʼís and professionals worldwide, reflecting the international nature of the Baháʼí community. Juxtaposing the Old City of Jerusalem and the garden in Haifa, they have something in common: they are both global pilgrimage destinations.

Father-son debate over cinema and devotion

The film adopts an experimental approach of father and son conversing while filming each other, and through this explores how different generations view religion and peace. The pair choose a loose structure to discuss ideas, philosophies, and doctrines. As is typical for Makhmalbāf (for example in A Moment of Innocence), this poetic perception of reality intertwines with fundamentally political remarks, highlighting the ongoing persecution of Baháʼí believers. The father and son declare that they aim to present the Baháʼí faith from two angles: Maysam, with his camera, tries to find the negative points, while his father looks for its positive aspects. There are, however, three perspectives in the movie; the third is another camera that records both father and son. This kind of multilayered viewpoint was also used much earlier in The Cyclist. The complex visual perspective is accompanied by a complex narrative of people from all over the world serving in the Terrace Gardens and fostering peace-loving attitudes through their interactions with nature. Muhsin Makhmalbāf accompanies a gardener (Ririva Eona Mabi) from Papua New Guinea, where Baháʼí is currently the largest minority religion in the country.41The Bahá’í Community of Papua New Guinea is estimated at approximately 60,000 and is representative of the country’s rich cultural and ethnic diversity. See https://bahai.org.pg/baha-i-community accessed January 03.2025. During their conversations, he finds similarities between the teachings of this religion and the positive ideas promoted by figures such as Nelson Mandela and Mahatma Gandhi. Their encounter also provides an opportunity for the director to manifest his concept of cinema. He reminds viewers that the medium began with a focus on real people and real lives. Gradually, it transformed into a film industry that is often called a “dream factory” because it creates and sells fantasies, and fictional stories transport viewers to different worlds, times, and realities, offering an escape from everyday life. Applying the original, documentary approach created by Louis Lumière, the director declares: “I don’t need an actor. The first person who walks by the camera, if it is looked at deeply, has a story to tell, and is suitable for the next film.”

Figure 13: A still featuring Muhsin and Maysam Makhmalbāf from The Gardener (Bāghbān, 2012), directed by Muhsin Makhmalbāf, accessed via https://Makhmalbaf.com/?q=Photo-Gallery/the-gardener-photo-gallery.

Figure 14: A still showing Muhsin and Maysam Makhmalbāf from The Gardener (Bāghbān, 2012), directed by Muhsin Makhmalbāf, accessed via https://Makhmalbaf.com/?q=Photo-Gallery/the-gardener-photo-gallery.

The major difference between the two perspectives—father’s and son’s—lies in their approach to the process of perception. The father believes that perception can be developed through concentration and patient observation: “Cinema is the extension of one’s eye, not the extension of one’s glasses. Better tools are like better glasses.”42Muhsin Makhmalbāf, The Gardener (2012), (0: 12: 38) On the contrary, his son appreciates technology, and short shots (up to 10 seconds) and questions the slow rhythm, finding it boring. While Maysam wants to capture as many places and people as possible, Mohsen is focused on the figure of one volunteer, perceiving his gardening as prayer and meditation: “He is educating himself to be like a gardener of society.”43Muhsin Makhmalbāf, The Gardener (2012), (0: 14: 24) The shots of the resting gardener are combined with dreamlike shots showing a bird’s-eye view of Haifa and the design of the gardens. Camera flight reveals the central axis and the structure of concentric circles that provide the main geometry of the eighteen terraces. The terraced gardens on Mount Carmel conjure up images of the Garden of Eden—paradise described in the Bible, and Qur’an. In the Bahá’í writings, gardens are sometimes used as metaphors for divine revelation and the Manifestations of God referred to as “divine gardeners.”44Bahá’u’lláh, Prayers and Meditations by Bahá’u’lláh (Wilmette: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1987), 160-161.

Muhsin Makhmalbāf wonders whether Iran would still be pursuing nuclear weapons if the Iranian people had adopted a peaceful religion. He shares this idea with his son, who is also investigating religion, but the son strongly believes that all religions tend to bring about destruction. As a result of these arguments, father and son separate and pursue their paths.

Maysam goes to the Old City of Jerusalem. Like most visitors, he visits the most important pilgrimage sites and historical landmarks. He visits the Chapel of Ascension, on the Mount of Olives, the site traditionally believed to be the earthly spot where Jesus ascended into Heaven after his Resurrection. He watches people reaching towards a slab of stone believed to be touched by Jesus’ body and bringing their clothes here to bless them. Maysam notices that Muslims do the same things in Iran: their faith in Muhammad is as strong as these people’s faith in Christ. Then, he visits the Dome of the Rock, the world’s oldest surviving Islamic shrine at the center of the Al-Aqsa Mosque. It is also known as a place where Muhammad is said to have gone to heaven. Maysam, as a cameraman and narrator at the same time, expresses his amazement over the striking proximity of sacred sites important for the believers of different denominations. The Western Wall—the most important site in the world for Jewish people—is located so close to the Al-Aqsa Mosque.45The Western Wall, sometimes also called the Wailing Wall. He walks the city streets carrying the camera, guided by the question: what is religion, a collective spirit or a series of practices? Noticing a bazaar near every sanctuary, Maysam wonders if religion is just a set of traditions and accessories, some of them sold globally, such as rosaries or pictures of saints.

Figure 15: A still showing the sanctuary in Jerusalem from The Gardener (Bāghbān, 2012), directed by Muhsin Makhmalbāf, accessed via https://Makhmalbaf.com/?q=Photo-Gallery/the-gardener-photo-gallery.

Who am I?

In the beginning of the movie, Makhmalbāf takes on the role of narrator through the use of voice-over and defines his identity through negation. The voice from outside the frame declares: “I am not a Christian, not a Muslim, not a Buddhist, not Zoroastrian, not a Jew, nor a Baháʼí. I am an agnostic filmmaker.” The Iranian identity of Muhsin and Maysam manifests through their language. In the conversations between them and in the voice-over, they speak Persian, which is a meaningful choice, considering that all the other characters speak English (however mostly as a second language). The use of Persian breaks the cultural hegemony of the English language and introduces trans-lingual dialogue within the film’s diegesis. This linguistic aspect is significant because it is linked to the question: can transnational film can be truly transnational if it only speaks in English?

The Gardener offers a range of identities as the people the director encounters come from various countries, of different ages and genders. The volunteers come from different countries—Paula Asadi from Canada, Guillaume Nyagatare from Rwanda, Tjireya Tjitendero Juzgado from Angola, Ian Huang from Taiwan and the United States, Bal Kumari Gurung from Nepal. Each volunteer has a unique history behind them, and each of them shares their thoughts on spirituality. The camera close-ups on each face emphasize their individuality.

Figure 16: A still showing the volunteers from different countries from The Gardener (Bāghbān, 2012), directed by Muhsin Makhmalbāf, accessed via https://Makhmalbaf.com/?q=Photo-Gallery/the-gardener-photo-gallery.

Almost every scene in The Gardener shows that identity comes in a variety of forms. The documentary deals with different layers of identity: ethnic, national religious, familial, and professional. It also shows that the sources of identification that ground human beings are immensely diverse. Social, cultural, and other narratives directly impact who we are. Consequently, our identities, as economist and philosopher Amartya Sen (witnessing Indian Muslims and Hindus fighting each other), has noted, are “inescapably plural.”46Amartya Sen, Identity and Violence – The Illusion of Destiny (New York: W.W. Norton, 2006), xiii. The film asks, how do various narratives of identity serve as vehicles of unity?

Muhsin Makhmalbāf is deeply concerned with this question. Maysam’s trip to Jerusalem shows how the sense of belonging to a certain religion brings coherence and direction to the disparate experiences of individuals. Another identity category is profession, which can be seen in the title of the film itself. As all the people working in the Terrace Gardens are volunteers, we may assume they are not professional gardeners. They came here not to do a job they were trained for but were driven by the spiritual motivation to take care of this sacred space. Muhsin’s and Maysam’s identities as filmmakers are marked by the constant presence of their cameras. The cameras they hold function as character-defining attributes, as the image we see is recorded by another cameraman, Mahmūd Kalārī. However, the father and son differ in how they perceive the director’s role and how they use their cameras. Maysam does not stay long in Haifa. Looking for answers to his questions, he soon sets off to Jerusalem, where he visits all the must-sees. He represents the attitude of the ubiquitous reporter, or even tourist. Muhsin stays in one place, focused on meditative contemplation of the Terrace Gardens. This choice brings him to a surprising transformation—he leaves the role of a filmmaker and takes on the role of a gardener. When Maysam returns from his trip, he sees his father in a gardener’s clothes watering the plants and his camera, hoping that it will blossom as well. Already a gardener, Muhsin delivers a reverse of his earlier monologue from the beginning of the film, assuming all the religious identities he denied before. The camera also offers an expanded perspective on consciousness. The camera inches, antlike, close to the ground and then soars birdlike over the grounds, which symbolically joins the spiritual with the terrestrial.

Figure 17: A still from The Gardener (Bāghbān, 2012), directed by Muhsin Makhmalbāf, https://Makhmalbaf.com/?q=Photo-Gallery/the-gardener-photo-gallery.

The Beauty in Diversity

In Makhmalbāf’s value system, cinema experience is what counts the most. The Gardener also reveals the dangers facing documentary film directors. Through his honest, neutral, but still emotional approach (also applied in Salām Sīnimā, 1995), Makhmalbāf proposes its own model of documentary film. Armond White notices The Gardener’s profundity: “It’s a reminder of how Iranians first broke through Western structures of cinematic structure.”47Armond White, “Critic’s Pick of the Week: The Gardener, reviewed by Armond White for CityArts,” NYFCC, August 7, 2013, accessed December 7, 2024, https://www.nyfcc.com/2013/08/critics-pick-of-the-week-the-gardener-reviewed-by-armond-white-for-cityarts/. The personal testimonies of volunteers working in Haifa’s Gardens are shown without judgment. The director listens patiently to the explanation and reasons why they follow the Bahá’í path: “Without religion would I have been able to overcome hatred?”48Muhsin Makhmalbāf, The Gardener (2012), (0:18:29) and “Religion releases the unleashed forces of the heart in the way that science cannot because science addresses the reason and yet the human needs the heart and the reason.”49Muhsin Makhmalbāf, The Gardener (2012), (0:38:21)

This attitude makes a powerful difference from contemporary directors such as Darren Aronofsky, Lars von Trier, and Sacha Baron Cohen, who are known for their critical and spiteful approach to religion in their films. The Gardener seems to be the opposite of the open antagonism in Religulous (2008), for example, a documentary film written by and starring comedian Bill Maher and directed by Larry Charles. The very title of this American production—the contamination of the words “religion” and “ridiculous,” reveals Maher’s skeptical and humorous approach to the subject. The film critically examines organized religion and its impact on society. Like Makhmalbāf, Maher travels to various religious sites such as the Vatican, Israel, and a Creationist Museum in Kentucky. He also engages with adherents of different faiths, including Christians, Jews, Muslims, Mormons, and Scientologists. The documentary addresses topics such as the compatibility of religious beliefs with scientific evidence. However, Maher’s goal is different; he is challenging faith and questioning the role of religion in the modern world. Religulous blends serious discussion with satirical commentary, reflecting Maher’s background in political comedy. It uses humor and pointed questioning to provoke thought. To some extent, his position is similar to Maysam Makhmalbāf’s, who also questions the necessity of religion in contemporary society. Maher states, “I am convinced that organized religions are the source of hatred in this world. What did Al-Kaida do? It turned religion into an engine for terrorism. The Taliban took children into religious schools and taught them how to become suicide bombs.”50Muhsin Makhmalbāf, The Gardener (2012), (0: 57: 36) Muhsin Makhmalbāf takes a different approach. Instead of rejecting all religious beliefs he dwells on their diversity and expresses his respect for the power of religion in shaping human minds and even leading people to die for religious values. Moreover, the experienced filmmaker also challenges new philosophies, as in his replica to his skeptic son: “You’re turning technology into a new religion. You are creating from Steve Jobs a Moses, a Jesus, a Mohammad. Was it not technology that led to Hiroshima?”51Muhsin Makhmalbāf, The Gardener (2012), (0: 57: 42)

Despite so many misuses of religious commitment, Muhsin Makhmalbāf declares his hope in the potential of religion and believes that people can use its power for the promotion of peace and friendship. When we hear his words, the camera spans over the trees, bushes, and flower beds. It reminds the traditional practice of storytellers—pardah-khāns—pointing at the illustrations painted onto a large canvas (pardah). However, the voices from behind the frame do not describe the garden; they refer to the issues of conflicting religious beliefs, intolerance, and possible reconciliation. It encourages the audience to look for deeper connections between the narration and the image. The gardens on Mount Carmel in Haifa illustrate the nexus between human beings and the natural world and symbolize the harmony that occurs when humanity’s actions are based on an awareness of the divine presence in nature. The gardens combine the diversity of gardening practices. They have elements of the Persian gardens of Shiraz, the Nishat Bagh gardens of Jammu and Kashmir in India, and elements of English Gardens. The beauty of the Bahá’í gardens derives from the harmony between different elements and styles, what ‘Abdu’l-Bahá calls “the beauty in diversity, the beauty in harmony.”52Abdu’l-Bahá, Paris Talks: Addresses Given by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá in Paris in 1911-1912 (London: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1995), 52. The terraces embody this principle of unity in diversity in every detail. The cameras show stairs leading up to the Shrine of the Báb, and then to the crest of the mountain, together with the fountains, flower beds, and paths surrounding them. They are symmetrical in design and convey an impression of geometric order. However, as the camera moves outwards, the landscaping becomes increasingly varied and irregular until it merges into the mountain’s natural environment. The paths are winding; wildflowers, bushes, and trees grow in profusion; the impression is one of organic naturalness. The man-made and the natural, the formal and the informal, each have their place here. Within each terrace, too, one finds a union of divergent elements. The steps are made of stone, but along their sides run streams of water whose murmur gives life to the stone. Each garden has a unique design, including a color scheme, and yet is integrated into the whole.

Such harmony between different elements symbolizes the unity in diversity that is the goal of the Bahá’í Faith. In the vision of Bahá’u’lláh, people, lands, and cultures will preserve their unique characteristics while harmonizing together to form a whole greater and more beautiful than the sum of its parts. ‛Abdu’l-Bahá’s explanation of the unity of humankind uses the metaphor of a garden. The diversity of hues and shapes adorns the garden. Similarly, when diverse shades of thought and character are brought together, it enriches the beauty and glory of human perfection.53Abdu’l-Bahá, Selections from the Writings of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá (Wilmette: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1997), 291-92. Amid the Terrace Gardens, Muhsin Makhmalbāf video camera is silhouetted against the sky like a tree, but also like an antenna, sensing mankind’s deepest political-spiritual needs. The father and son cannot come to an understanding about religion.

Mirrors as Portals to the Divine as Symbols of Self-reflection

The Bahá’í teachings explain that spiritual qualities are gifts from God that we may receive by turning the mirror of our hearts towards Him. The Báb was the first to use mirrors to demonstrate unity through truth. He asked his followers to be like a “concourse of mirrors” following the one true God.54Selections from the Writings of the Báb, accessed January 03.2025, https://www.bahai.org/library/authoritative-texts/the-bab/selections-writings-bab/4#850847635. In The Gardener, we can see the exploration of the symbolic meaning of the mirror. Ririva Eona Mabi, as a Bahá’í believer, compares the human heart to a mirror which should be cleaned from the dust. Walking down the avenue, the gardener carries the huge, unframed mirror reflecting red flowers. In the next shot, we can also see Muhsin Makhmalbāf recording the gardener and reflecting in the mirror. Then, he puts aside his camera and holds the mirror. Makhmalbāf and the gardener face each other reflecting in their mirrors, creating a “concourse of mirrors.” They walk together to the seashore, facing their mirrors toward the waves.

Figure 18: A still showing Muhsin Makhmalbāf’s reflection in a mirror held by Ririva Eona Mabi from The Gardener (Bāghbān, 2012), directed by Muhsin Makhmalbāf, accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LIR3QAkIKT8.

Figure 19: A still showing the gardener’s reflection in a mirror held by Muhsin Makhmalbāf from The Gardener (Bāghbān, 2012), directed by Muhsin Makhmalbāf, accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LIR3QAkIKT8.

Mirrors hold multifaceted symbolism in Persian mythology. They represent portals to the divine, tools for self-reflection, symbols of deception and transformation, and instruments of justice and truth. In Persian culture, religious ceremonies and rituals often incorporate mirrors as tools for divination and communication with the supernatural, for instance during weddings, and Nawrūz celebrations. One notable example from Persian mythology is the story of Jamshīd, the legendary king who discovered the mirror, and gained access to the divine realm and obtained knowledge from the gods. Beyond their connection to the divine, mirrors in Persian mythology also symbolize introspection and self-discovery. These examples showcase the mirror as a powerful tool for self-examination, encouraging individuals to delve into their inner depths. Characters such as Zāl and Rustam use mirrors to confront their inner selves, gain wisdom, and understand their true nature. In Muslim mystical symbolism, the mirror is the image of the soul reflecting the supernatural reality, which, for the mystic, is the only real reality.

Figure 20: The poster for the 16th Fajr Film Festival in Tehran, accessed via https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/16th_Fajr_International_Film_Festival.

On the poster of the 16th Fajr Film Festival held in Tehran, in February 1998, a man in white holds a mirror that reflects light. The metaphor of the screen as a mirror is used in Western film theory mainly to represent psychoanalytic reflection. Adopted by the Iranians, this metaphor acquired spiritual and mystical meanings. The screen mirror can serve as a surface reflecting life and a gateway to a higher reality, providing a glimpse into the unseen world.

Conclusion

Makhmalbāf’s films prove the potential to affect, subvert, and transform both national and transnational cinema. By working with international production companies and filming in various countries, the artist has shown the potential of cross-cultural collaboration in filmmaking. Each of his films made abroad has a different transnational trajectory, whether within a film’s narrative or a production process. These differences can also be seen in the reception of his movies. The Gardener gained worldwide attention and acclaim. The film has been shown in more than 20 film festivals and won the Best Documentary award from Beirut International Film Festival and the special Maverick Award at the Motovun Film Festival in Croatia. The film was selected as “Critic’s Pick of the Week” by New York Film Critics Circle in 2013, “Best of the Fest” at Busan Film Festival by The Hollywood Reporter, and “Top Ten Films” at Mumbai Film Festival by Times of India.55For the full list of awards see: accessed December 25, 2025, https://www.Makhmalbaf.com/?q=film/the-gardener Its script was added to the Library of Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.

At the same time, The Gardener became Makhmalbāf’s most controversial film to date. It was the first time since the 1979 revolution that an Iranian filmmaker shot a movie in Israel and posed such radical statements about religion. It should be mentioned, however, that it was not the artist’s first attempt to re-establish a dialogue with Israel. Although he did not travel to the country himself, he had sent his movie Gabbah. He was hoping that this film could change the minds of the Israeli people about the negative image of Iranians. This resulted in an attack by the Iranian media on the director and an interrogation by the secret police.56“Iranian film-maker Mohsen Makhmalbaf on his relationship with Israel,” The Guardian, July 17, 2013, accessed January 03, 2025, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fWYRzSrtofA It should therefore come as no surprise that he committed one of Iran’s gravest sins: visiting Israel. Consequently, Javād Shamaqdarī, the Director of the Iran Cinema Organization, demanded that the Film Museum of Iran (FMI) remove all of Makhmalbāf’s memorabilia from its archives, and erase his cinematic legacy from the country.57“Iran Cinema Organization asks film museum to remove Mohsen Makhmalbaf memorabilia,” Tehran Times, July 15, 2013, accessed January 03. 2025, Iran Cinema Organization asks film museum to remove Mohsen Makhmalbaf memorabilia – Tehran Times He made the demand in response to Makhmalbāf’s presence at the Jerusalem International Film Festival in July 2013, and also due to his remarks in favor of Bahaism during the event. In addition, before the festival, Open letter to Filmmaker Mohsen Makhmalbāf: Please be a Messenger of Freedom for Iranian and Palestinian People was published in the magazine “Jadaliyya” urging him not to attend the festival. A group of prominent Iranian scholars, artists, journalists, and activists expressed their deep concern that Makhmalbāf’s participation directly violates the International call for Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS) of the State of Israel issued by Palestinian civil society in 2005, as well as the specific call for Academic and Cultural Boycott of Israel issued in July 2004. They reminded the director that performing in Israeli is a political statement, condemning his disregard for the global movement for Palestinian human rights and his implicit support for Israel’s apartheid policies. They also pointed out that many international artists already refused to take part in cultural events taking place in Israel and others who had initially accepted this invitation have cancelled their performances, preferring to show their support for the struggle of the Palestinian for their most elementary human rights.58The full text of the letter is available here: https://www.jadaliyya.com/Details/29064 , accessed March 06, 2025. Interestingly, the letter was also signed by Iranian scholars working at European and American universities, sometimes even the researchers in the field of Global and Transnational Studies.

This complex reception of the film and its severe consequences prove that the concept of “transnational cinema” should also consider that border-crossing activities in the film industry are often fraught with power dynamics and politics. These conditions confirm Jean Baudrillard’s observation of the tensions between globalization and universalization. He associated globalization with the spread of technology, markets, tourism, and information, driven by economic and cultural homogenization. Universalization, on the other hand, refers to the Enlightenment ideals of spreading universal values such as democracy, liberty, and human rights. Baudrillard argued that globalization leads to the commodification of universal values, reducing them to mere products or commodities, similar to consumer goods.59Fernanda Navarro, Jean Baudrillard, Power Infierno (Paris: Galilée, 2002), 63-83. In fact, however, the spheres of globalization and universalization are separate. Āyatallāh Khumaynī effectively used cassette tapes as a tool to spread his revolutionary message during his exile in the 1970s. These tapes contained his sermons and speeches, which were smuggled into Iran and widely distributed among his supporters. The cassette tapes allowed Khumaynī to bypass state-controlled media and directly communicate with the Iranian people, rallying them against the Shah’s regime. This innovative use of technology played a crucial role in mobilizing the masses and shaping the Iranian Revolution, however the message spread was promoting neither the dominance of global markets and culture or the Western universal values. Similarly, the fact that directors from all over the world are increasingly using the same technology and are increasingly involved in international co-productions or making films abroad does not mean that the world of values is becoming homogenized. Makhmalbāf’s films are proof of this disjunction. Regardless of the country in which his films are made and with whom they are produced, they all manifest some key aspects of the director’s values. They often focus on the struggles of marginalized individuals, reflecting his commitment to humanistic values and empathy for the underprivileged. His works frequently critique societal and political structures, addressing themes like oppression and personal freedom. Makhmalbāf also celebrates cultural heritage while also questioning traditional norms, and pointing out the power of cinema as a medium tool for challenging authoritarianism. Besides, the case of Makhmalbāf’s family exemplifies that modern nations actually consist of widely dispersed groups of people. If this is the case, it follows that nations are in some sense diasporic.

Cite this article

After his departure from Iran, Mohsen Makhmalbaf emerged as a paradigmatic figure of the displaced filmmaker, producing what Hamid Naficy defines as “accented cinema”—works shaped by exile, identity, and cultural hybridity. However, the aim of this article is not solely to examine his post-emigration phase, but to trace how transnational sensibilities and identity negotiations were already embedded in his aesthetic strategies well before his relocation. Since the late 1980s, Makhmalbaf has consistently challenged dominant narrative conventions and discursive frameworks by foregrounding marginalized voices and moving away from linear, cause-and-effect storytelling. Instead, he employs polyphonic structures and aesthetic leitmotifs that evoke emotional and sensory registers, offering a more nuanced and layered cinematic experience. His innovations have not only redefined narrative form in Iranian cinema but have also inspired a generation of filmmakers grappling with themes of exile, belonging, and cultural displacement. Moreover, through collaborations with international production houses and filming across borders, Makhmalbaf has demonstrated the transformative possibilities of cross-cultural filmmaking as a space of dialogue, negotiation, and resistance