Alternative Cinema: A Cinematic Revolution Before 1979

Iranian pre-revolutionary cinema has been characterized by different cinematic trends. While distinct in their modes of production, cinematic grammar, means of circulation, and reception, these cinematic trends were connected and overlapping. Starting in the late 1950s and early 1960s, a new cinematic movement grew in Iran that drew on some of the tropes of the extant post-WWII popular film industry while also distancing itself from it. Iran’s popular film industry, commonly known as “Film-Farsi” (Persian-language-films), was disparaged by film critics, cultural thinkers, actors, and directors as producing commercial, cheap productions that lacked serious artistic value. In an era defined by left-leaning political ideologies, third world nationalisms, and new artistic movements, a group of young Iranian filmmakers embarked on a journey that fostered a new cinematic movement aligned with new cinema trends and political ideologies around the world. This artistic and politically inclined filmic trend came to be regarded as an “alternative cinema” at the time—also recognized as Iran’s pre-revolutionary New Wave cinema, in retrospect. While grounded in Iranian traditions and practices, the films of alternative cinema can be regarded as vernacular-cosmopolitan offerings by virtue of their engagement with global ideological currents and artistic trends. The film directors of this alternative movement took their cameras to the streets (both physically and metaphorically) and recorded the Iranian quotidian in artistic and internationally informed forms that spoke to the local and global anxieties of the period.

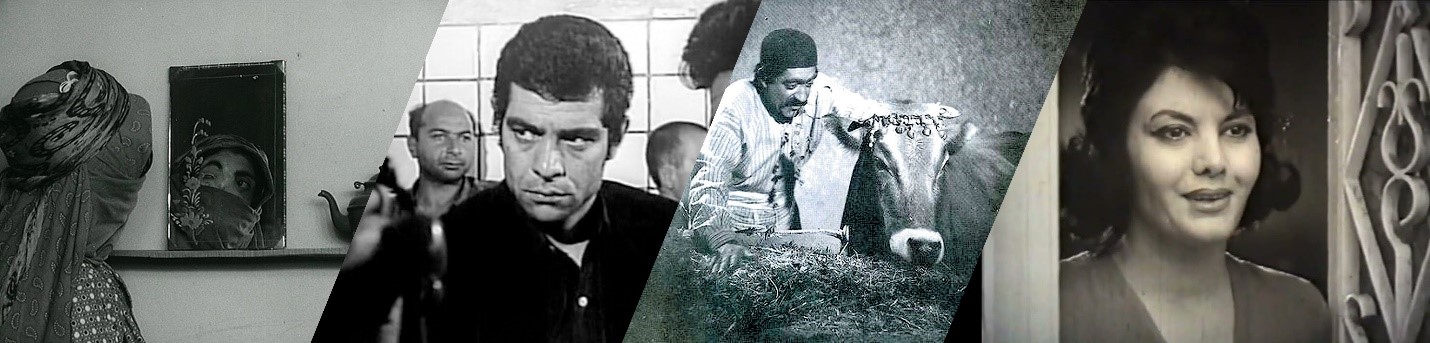

Figure 1 (from left): A still from Khānah siyāh ast (The House is Black, 1963), directed by Furūgh Farrukhzād. Qaysar (1969), directed by Mas‛ūd Kīmiyāyī. Gāv (The Cow, 1969), directed by Dāryūsh Mihrjū’ī. Junūb-i shahr (South of the City, 1958), directed by Farrukh Ghaffārī.

In 1967, the Iranian filmmaker, poet, and critic, Farīdūn Rahnamā, criticized Iranian cinema by saying, “Today we are submerged in imitation.” “If imitation is our role,” he continued, then “that role must not be.” “In the past, our noble deeds, which have sometimes appeared as miracles to outsiders . . . have been due to our combining seemingly incommensurable elements.” Such combining of forces, a blending of imitation and innovation, a fusion of global cinematic insight and local Iranian vision, Rahnamā believed, could ignite the Iranian “spiritual force” in filmmaking. “In this combinatorial path, we will be inevitably informed of the efforts and rectitude of all countries,” Rahnamā stated; what was unnecessary, however, was to follow other societies’ “dead-ends, crises, and extremes” in cinema. By implementing a combinatorial spirit in filmmaking, Rahnamā believed that Iranians could expose unexplored openings in culture that Westerners had also been waiting for.1Farīdūn Rahnamā, “Cinematic Insight,” Sīnimā-yi Āzād, Kitāb-i Duvvum [Free Cinema, Book Two] (Tehran: Sīnimā-yi Āzād Publishing Center, 1351 [1972]), 11-12. Translated by the author. While this piece was published in Free Cinema in 1972, the text was part of a speech that Rahnamā was supposed to deliver five years earlier at a cinema seminar which was to be broadcast on the radio. Such a cosmopolitan vision of filmmaking that drew on global cinematic experiences to foreground an Iranian cinematic imagination came to characterize a national filmmaking movement prior to the 1979 Revolution.

Iranian pre-revolutionary cinema has been defined by different artistic trends. While distinct in their characteristics, modes of production, means of circulation, and reception, these cinematic movements were connected and overlapping. Starting in the late 1950s and early 1960s, a new cinematic movement grew in Iran that drew on some of the tropes of the extant popular film industry, while distantiating itself from it. Iran’s post-World War II (WWII) popular film industry, usually regarded as “Film-Farsi” (Persian-language-films), was strongly criticized and disparaged by film critics, cultural thinkers, actors, and directors as producing commercial and cheap productions that lacked serious artistic value. In an era defined by a global counterculture movement, left-leaning political ideologies, third world nationalisms, and new wave cinematic movements, a young group of Iranian filmmakers embarked on the creation of a socially committed and realist cinematic movement that aligned with new waves around the world. As discrepancies emerged between this artistically and politically inclined trend and Iran’s mainstream films, some critics adopted the term “Alternative Cinema” for this movement. Iranian alternative films can be considered as vernacular-cosmopolitan productions. By virtue of their engagement with global ideological currents and artistic trends through their directors, producers, writers, actors, and global networks that circulated film culture, these productions had a cosmopolitan colour that appealed to an educated middle-class. On the other hand, alternative filmmakers looked to the Iranian past and traditions to shape a collective consciousness through film and imagine a new Iran that was free from tyranny and imperialism. It is not surprising, then, that this movement emerged while a collective political consciousness was taking shape in Iran before 1979.

Laying the Groundwork for Alternative Cinema

While cinema in Iran had become popular among the public by the 1930s, and while Persian language films were produced in Iran and India, the onset of WWII and the invasion of Iran by Allied forces gave rise to a hiatus in narrative feature filmmaking. This pause, however, did not mean the ceasing of cinematic activities as movie theaters still showcased international films and magazines published articles about world cinema. After the end of WWII and the withdrawal of the Allies from the country, a sustained film industry emerged in Iran. Despite just a few years of operation, however, this burgeoning popular film industry came under severe criticism and scrutiny from film critics, directors, actors, and cultural thinkers. Commercial films were reprimanded for their popular cultural tropes, lack of technical quality, mimicry in borrowing storylines from international commercial cinemas like Hollywood and Egyptian cinema, and their concern with profit-making.

Hūshang Kāvūsī, a pre-revolutionary filmmaker and critic who first coined the term “Film-Farsi” for Iranian post-WWII popular films, did not regard Iran’s popular cinema as part of the canon of Iranian cinema. He considered these visual offerings as films that “spoke in the Persian language” but, from a technical perspective, were not worthy enough to be included within the annals of a national cinema.2Hūshang Kāvūsī, “Sīnimā-yi bī-sāmān [Disorderly Cinema],” Nigīn, no. 34 (Isfand 1346 [March 1968]), 9. Translated by the author. Writing in Firdawsī magazine in 1955, Kāvūsī criticized the seven years of sustained film production after WWII as possessing no “cinematic value.”3Hūshang Kāvūsī, “Fīlm-Fārsī bi Kujā Mīravad? [Where is Film-Farsi Going?],” Firdawsī, no. 144 (Tir 18, 1333 [June 29, 1954]), page number not clear. Translated by the author. In the 1960s, he continued his battle with Film-Farsi when he wrote that “from twenty years ago hundreds of thousands of kilometers of film have been utilized, millions of Tomans have been spent, thousands of hours have been wasted, and the result, which is the current Farsi cinema, has not been able to find a place for itself in global cinema.”4Kāvūsī, “Sīnimā-yi bī-sāmān [Disorderly Cinema],” Nigīn, no. 34 (Isfand 1346 [March 1968]), 8. Translated by the author. Similar to Kāvūsī, Farhang Farahī also found it pitiful to call Film-Farsi “a filmmaking industry.”5Farhang Farahī, “Jumʻah Bāzār-i Sīnimā-yi Fīlm-Fārsī” [The Friday bazaar of Film-Farsi], Nigīn 44 (Day 30, 1347 [Jan. 20, 1969]): 25. Translated by the author. Farahi was especially frustrated that Film-Farsi would remain on screens for more than two or three weeks and competed with expensive commercial international productions, while grade A outstanding and meaningful international films were either never showcased in Iran or were screened for only one week.6Farahī, “Jumʻih Bāzār-i Sīnimā-yi Fīlm-Fārsī,” 26. If Film-Farsi was “worthless and vulgar,” it was not because it was part of a “young Persian Iranian industry” or because it did not receive the attention of the government, the critics held; it was because “a group of profit-seeking and greedy merchants” guided the industry.7Farahī, “Jumʻih Bāzār-i Sīnimā-yi Fīlm-Fārsī,” 26. Detecting a grave “danger” associated with the strong “disposition” of the Iranian public for “the bazaar of vulgarism,” Kāvūsī called for “an artistic revolution.”8Hūshang Kāvūsī, “Gandāb-i Rūbirū [The Wasteland Ahead],” Nigīn 44 (Day 30, 1347 [Jan. 20, 1969]), 6.

Through criticism, Kāvūsī believed, “a path would automatically be shown”; however abstract, this path could be teased “out of the heart of words” of cultural thinkers.9This is taken from an interview with Hūshang Kāvūsī and other filmmakers and film critics. See “Mīz-i Gird-i Sīnimā-yi Irān 1 [Roundtable on Iranian Cinema I],” Farhang va Zindigī [Culture and Life] (Tābistān 1354 [Summer 1975]), 55. Translated by the author. As criticisms aimed at Film-Farsi increased in the 1950s, the roots of a filmmaking industry grew stronger and deeper. The number of movie theatres in Tehran and provincial cities multiplied. Film magazines and cultural periodicals that wrote about Iranian and international films, actors and actresses, and the industry boomed in number. Journals such as ‛Alam-i Hunar (Hollywood, The World of Art), Sitārah-yi Sīnimā (Cinema Star), Payk-i Sinimā (Cinema Courier), Fīlm va Hunar (Film and Art), Nigīn (Jewel), Bāmshād, Sipīd va Sīyāh (White and Black), Rushanfikr (Intellectual), and Tihrān Musavvar (Tehran Illustrated) published articles and posters that represented the latest films and screenings in international movie theatres, film reviews, cultural essays, and biographies of movie stars and directors, in addition to the latest fashion of Hollywood, French, Italian, Danish, and later German and Russian cinemas. New film studios began operating, while more and more artists entered the world of cinema. Meanwhile, with the heightened flow of capital after WWII and Iran’s increased integration into the world economy during the Cold War, an increasing number of international mainstream and arthouse films were featured in movie theatres. While increasingly connecting Iran to the world, the wide circulation of such cultural productions aroused anxieties about “Westoxification.”10Westoxication (also referred to as Occidentosis) is a term that was coined by writer and cultural critic, Jalāl Āl-i Ahmad, in his 1962 book by the same title, Gharbzadigī. Westoxification refers to the encroachment of Western cultural imperialism by the pervasive adoption of Western lifestyles, values, and consumerism, which lead to the erosion of Iranian norms and culture.

Figure 2: Iranian Film magazines, from left to right: Sitārah-yi Sīnimā (Cinema Star), Bāmshād, Fīlm va Hunar (Film and Art), Sipīd va Sīyāh (White and Black).

To add to such tensions, the 1953 CIA- and MI6-engineered coup against Mohammad Mosaddeq’s government deepened apprehensions about American imperialism, Iranian despotism, and political suppression in the Iranian consciousness. Mohammad Reza Shah’s revolution from above, or the White Revolution of 1963, added to this growing social angst. Consisting of a series of education and land reforms that aimed to fulfill “the expectations of an increasingly politically aware general public,” and prevent the danger of “a revolution from below,” this revolution posed the Iranian monarchy “as the lynchpin of Iranian state and society.”11Ali M. Ansari, “The Myth of the White Revolution: Mohammad Reza Shah, ‘Modernization’ and the Consolidation of Power,” Middle Eastern Studies 37, no. 3 (2001): 2. With “modernism” at its central ideology, the revolution led to rapid modernization, urbanization, and a growing wealth gap that stirred anxiety among various sectors of society, but especially the poor and conservatives.

It was within these conditions that a group of young Iranian filmmakers, who heeded the criticisms aimed at the popular film industry, and who were now increasingly linked to global visual, literary, and political circuits, embarked on the crafting of a new cinema movement. Many of these young filmmakers had received their education in film, art, or other fields outside Iran. To name a few: Suhrab Shahid Sales (1943–98) studied cinema in both Vienna and Paris; Kāmrān Shīrdil (b. 1939) studied architecture and urbanism at the University of Rome, film at the Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia in Italy, and worked under the mentorship of directors such as Nanni Loy (1925–95) and Michelangelo Antonioni while he engaged with Italian neorealism; Dāryūsh Mihrjū’ī (b. 1939) studied at the Department of Cinema at UCLA under the instruction of directors such as Jean Renoir (1894–1979); Farīdūn Rahnamā studied and wrote poetry in France; and Parvīz Kīmīyāvī (b. 1939) also studied film and photography in France. Many others were well-informed of cinematic activities in Iran and around the world, had watched Iranian and international films, and were already familiar with film magazines and publications in and beyond Iran. In the years and decades that followed WWII, numerous associations formed that organized international film screenings or film festivals. The National Film Association established in 1949 (later changed to the National Film Archive of Iran), the National Art Association and Cine Club established in 1954, and the Pahlavi University Film Association were some of the groups that organized cultural and film events. In addition, beginning in the 1960s, numerous film festivals were convened in Iran that served as artistic hubs and brought together actors, directors, artists, and films from around the world. Tehran International Festival of Films for Children and Young Adults (starting in 1966), Shiraz Persepolis Arts Festival (starting in 1967), Sipās (Gratitude) Film Festival (starting in 1969), Free (Azad) Cinema Film Festival (starting in 1970), Tehran International Film Festival (starting in 1972), and Tūs Festival (starting in 1975) showcased international films and linked the global cinematic imaginarium to an Iranian one. The films that were made by alternative filmmakers were informed by these cosmopolitan experiences, as well as dynamic national debates during which they were produced. The films of this movement can arguably be considered as cosmopolitan vernacular visual offerings in that they drew on global artistic and political trends to speak about the contemporary Iranian experience.

Thematically and textually, Italian neorealism made significant contributions to the new culture of filmmaking in Iran. Like Italian neorealist films, alternative films used realism and surrealism, an invisible style of continuity in filming and editing, camera movements and positions, minimal artificial lighting and natural light in exterior locations, non-professional actors in addition to professional ones, and “moral poetics” to evoke a collective ethical commitment to social issues that gripped the world.12Hamid Naficy, “Neorealism Iranian Style,” in Global Neorealism: The Transnational History of a Film Style, ed. Saverio Giovacchini and Robert Sklar (Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, 2011). This shared moral commitment was expected to, as Naficy argues, “eliminate filmmakers’ individual, personal, and authorial differences and unite them on larger social issues.”13Naficy, “Neorealism Iranian Style.” Rather than studio sets, the streets and alleyways of metropolitan cities such as Tehran took centerstage in many of these films, not too dissimilar to the status of Rome in Italian neorealism. The pace of earlier films gave way to more observation and contemplation. The characters were more nuanced and flawed, with many films paying particular attention to antiheroes, inviting the audiences to explore more philosophical and existential questions. French Nouvelle Vague, Third Cinema, and other emergent new wave cinemas were also of significance to the shaping of this film movement.

Thematically, inspired by Italian neorealist films, filmmakers focused on aspects of everyday life that were sidelined or suppressed in Iran’s post-WWII visual culture. The quotidian lives of people from lower socio-economic classes became the subject of many social realist films of this ear, including: the working-class; those living in the outskirts of the city; the unemployed; impoverished villagers; the overlooked terminally ill; marginalized small-time thieves, petty criminals, and the formerly imprisoned; restless youth in an unstable society; and socially scorned women like cabaret dancers and sex-workers. While popular films also attended to many of the same topics, the subjects of alternative films were approached from a more humanist sensibility; their stories were told in more unorthodox narrative structures, and the films were aesthetically distinct and at times modernist. Exploitation was a common trope in many of these films. Overall, the collection of alternative films from this era worked to engender a new national culture and a collective consciousness. Noting the distinction in filmmaking in a 1996 retrospective, Farrukh Ghaffari, an influential critic and director of the pre-revolutionary era, proposed “Alternative Cinema” (sīnimā-yi mutafāvit) as an accurate term for this movement in filmmaking.14Farrukh Ghaffārī, “Sīnimā-yi Īrān az Dīrūz tā Imrūz [Iran’s cinema from yesterday to today],” Irān Nāmah 14, no. 3 (Tābistān 1375 [Summer 1996]): 350. Translated by the author. These films, while not cohesive in terms of their texts, themes, style, or the social background of their directors, were taken as alternatives to (even if overlapping with) the visual offerings of the popular film industry and those of the Pahlavi state.

It should be noted that the economic conditions of Iran permitted for the emergence of a somewhat niche market for intellectual and arthouse films. As Iran was increasingly integrated into the world economy, especially due to its oil production in the 1960s and 1970s, a social stratification of cinema and theatre viewers also emerged that allowed for arthouse and less commercially successful films to find their target audience. Since this was not an audience that developed into a distinct entity overnight, a lot of times filmmakers drew on commercially popular tropes in their films to attract spectators and showcase their films in movie theatres for longer periods of time. Alternative films often came under a barrage of criticism from film critics and arthouse film enthusiasts for indulging in the song and dance numbers and fight scenes that defined Film-Farsi.

The Emergence of Alternative Cinema, 1950s-1960s

Directed by Farrukh Ghaffārī, Junūb-i Shahr (South of the City, 1958) was one of the earliest films that blurred the distinction between Film-Farsi and alternative films. It drew on some of the tropes of popular film while also distancing itself from them by taking a more neorealist approach to societal issues such as urban moral disintegration and unemployment. The director shot many of the film’s scenes in real spaces in the south of Tehran that conveyed the film’s urban atmosphere and the poverty associated with this area. The film was banned by the government after a few nights of screening and released again in 1964 under the title Riqābat dar shahr (Competition in the City).15Some attribute the banning of the film to its depiction of the south of Tehran and some to the rumours surrounding the film, including its funding by the Soviet Union. For example see, Hamid Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema, Volume 2: The Industrializing Years, 1941-1978 (Duke University Press, 2011), 188-189. To release it, Ghaffārī had to re-edit the film and incorporate new scenes of singing and dancing to divert the focus away from the impoverished neighbourhood where the film was shot and towards two men’s competition for a woman’s affection.16Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema, 190.

Figure 3: Poster for Junūb-i shahr (South of the City, 1958). Farrukh Ghaffārī

The opening shots of the re-edited film depict different parts of Tehran which set the stage for the narrative. The film tends to the life of Iffat, a widower who works at a cabaret to take care of her young, orphaned son. ‛Iffat (played by Fakhrī Khurvash) tells her story in a voiceover which highlights her perspective and expresses her frustration with men corrupting destitute women and with the image associated with “a woman of the café.” Iffat’s account depicts issues faced by women of her strata, especially as an unemployed single mother. She eventually meets and falls in love with Farhād, a kulāh-makhmalī (velvet-hat-wearing) man of virtuous character, who must contend with Asghar, a vile jāhil, over ‛Iffat’s affection (jāhil is a term that refers to tough guys, often of the ignorant type). The juxtaposition of the two men works to foreground Iranian customs and traditional virtues such as justness and righteousness; scenes of traditional cafes, minstrel music, and Naqqali (Iranian dramatic storytelling) also loom large in the film. Despite the vile jāhil’s efforts, ‛Iffat and Farhād finally triumph over the trials and tribulations created by Asghar. The film ends with the couple depicted in their new lives as a middle-class family; Farhad has become a white-collar worker and Iffat a housewife. The last scenes of the film depicting the social mobility of the couple and their residence in one of the more affluent parts of Tehran were reportedly added by the director in order for the state to lift the ban on the film. It is worth remembering that South of the City was released after the White Revolution, which promised progress and modernization to the people.

Figure 4: A still from Junūb-i shahr (South of the City, 1958). Farrukh Ghaffārī, accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9ii3KKJb6V8 (00:13:56)

Following early films such as South of the City, the 1960s was a formative decade for the crystallization of Alternative Cinema. For instance, Furūgh Farrukhzād’s Khānah sīyāh ast (The House is Black, 1962) portrays a neorealist depiction of a leper community at the Bābā-Bāghī hospice in Tabriz. Commissioned by the Society for the Assistance of Lepers and produced by an alternative cinema filmmaker, Ibrāhīm Gulistān, the documentary is a poetic film essay that aims to humanize a forgotten and marginalized community. Beginning with close shots of young lepers, the film compels the viewer to face the brutal reality of a people inflicted by this contagious disease—a disease commonly found among the poor in urban areas. By engraving the deformed faces of her subjects on celluloid and in the viewer’s mind, Farrukhzād urges her audience to remember the fragility of the human body and society’s responsibility to the most vulnerable. Farrukhzād’s poetry, which she recites over scenes of the quotidian in the leper colony, foregrounds her perspective, gives expression to the lepers’ misery, and highlights their dreams of rehabilitation and return. With her effective use of light and moving shots, Farrukhzād opens the viewer to a sense of beauty that the leper community is conventionally deprived of. “Leprosy is not an incurable disease,” the narrator states, calling the viewer to arms in a humanist spirit.

Figure 5: A still from Khānah sīyāh ast (The House is Black, 1963). Furūgh Farrukhzād, accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xFe_Y4btwWs (00:02:02)

Similar to Farrokhzad’s The House is Black, Shīrdil’s three social documentaries made in the 1960s also attended to the lives of society’s marginalized. In his late teenage years, Kāmrān Shīrdil moved to Italy to continue his education first in architecture at the University of Rome and then in cinema at Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia. He learned filmmaking under the instruction of notable directors such as Nanni Loy, while benefitting from a vivacious cinematic culture in post-WWII Italy that encompassed the contributions of Michelangelo Antonioni, Pier Paolo Pasolini, and Roberto Rossellini. When Shīrdil returned to Iran in the mid-1960s, he was almost immediately employed by the Pahlavi Ministry of Culture and Art to make a series of documentaries about the humanitarian work of the Women’s Organization (Sāzmān-i Zanān). Informed by the cinematic idiom of Italian neorealism, Shīrdil’s documentaries provided a social realist portrayal of everyday life that directly questioned state policies, challenged the Organization’s efforts, and thus faced censorship.

For instance, while Shīrdil’s Zindān-i Zanān (Women’s Prison, 1965) was commissioned to attend to the educational and training activities of the Women’s Organization in prison, it instead shed light on the despairing lives of poverty-stricken women who were forced into criminal activities, drug-trafficking, and murder. Taking a bolder approach, Shīrdil’s Women’s Quarter (1966) concentrated on the desperation, deception, and dispossession of sex workers in Tehran’s red-light district, with some attention to their supposed rehabilitation through education and training by the Women’s Organization. Due to the film’s dark portrayal of life in Tehran, the film was banned by the government before shooting was completed and was only finished after the 1979 Revolution, when Ibrāhīm Gulistān’s photos of the red-light district—ten years after the film was originally shot—were used. The superimposition of the voices of women narrating their firsthand accounts of hardship and despair over photos of sex workers in the district provide a compelling image of a dystopic Tehran in the 1960s and 1970s. Shīrdil’s Tihrān pāytakht-i Īrān ast (Tehran is the Capital of Iran, 1966) likewise addressed the impoverishment of the Khazānah neighbourhood in the south of the city. Shots and images of the destitute residents of Khazānah who did not have access to clean water, garbage collection, or other facilities expected in a modern city directly challenged the Shah’s reforms through his White Revolution. In the film, a teacher’s dictation to students enrolled in the Organization’s adult classes includes sections from a textbook about the success of the Shah’s White Revolution and the government’s attempts at modernization. The teacher’s voice projected atop the images of a deprived neighborhood serve as a clear objection to the Shah’s modernizing campaign. Taken together, the films of Farrukhzād and Shīrdil arguably can be understood as militant documentaries that implored a collective consciousness by representing neglected sectors of society, appealing to a shared humanity that called for socio-political action.

The Global 1960s: Key Films in Alternative Cinema

The years 1967 to 1969, significant in global social and political affairs, were at the crux of Iran’s alternative filmmaking trend. Of note, Farīdūn Rahnamā’s Sīyāvash dar Takht-i Jamshīd (Siavash in Persepolis, 1967) marked a significant turning point in filmmaking. The juxtaposition of real and fictional, concrete and imaginary, which characterized some of Shīrdil’s work, also took centre stage in Rahnamā’s films. Siavash in Persepolis is based on the epic story of Siyavash in Firdawsi’s epic poem, Shāhnāmah (Book of Kings) produced in the eleventh century. In Shāhnāmah, Sīyāvash is a warrior prince who attempts to bring peace to Iran, the land ruled by his father. A victim of lies and schemes begun by his stepmother, Sīyāvash is put to the test of fire to prove his innocence. Walking out of the fire alive, a triumphant Sīyāvash is then entrusted with the task of engaging in battle with the land of Tūrān. After a falling out with his father over a peace treaty offered by the Tūrāni King, Sīyāvash flees to Tūrān and marries a Tūrāni princess. While taking refuge there, he arouses the jealousy of some members of the royal family, which eventually leads to Sīyāvash’s execution.

Figure 6: A still from Sīyāvash dar Takht-i Jamshīd (Siavash in Persepolis, 1967). Farīdūn Rahnamā, accessed via https://www.aparat.com/v/n89px9c (00:51:18)

Rahnamā’s film was shot in the ruins of Persepolis, staged without much glamour and glory. Including documentary-style footage, modern-style dances, and tourists visiting the ruins, Rahnamā brilliantly mixes fact and fiction to allude to the pseudo-historical origins of a nation. Collapsing boundaries of time, the film brings the past into the present to make Siyavash relevant to the modern-day Iranian. The message is even more forceful when considering that the film was released in the same year that Mohammad Reza Shah coronated himself in a lavish ceremony in Tehran. In a way, Mohammad Reza Shah revealed himself to be far from the admirable and justice-seeking Sīyāvash of Firdawsī’s epic poem.

In a film essay on Siavash in Persepolis, film critic and director Nasīb Nasībī proclaimed Rahnamā as the “only cinematographer in Iran who carries the weight of Iranian thought and spirituality,” one whose film is a “totality about the human.”17Nasīb Nasībī, “Sīyāvash dar Takht-i Jamshīd [Siavash in Persepolis],” Sīnimā-yi Āzād, Kitāb-i Avval [Free Cinema, Book One] (Tehran: Sīnimā-yi Āzād Publishing Center, 1350 [1971]), 63. Translated by the author. Rahnamā’s films, in Nasībī’s opinion, would one day turn into a school of filmmaking, and this film in particular, due to its reach into the past, “is connected to a thousand years later.”18Nasībī, “Sīyāvash dar Takht-i Jamshīd [Siavash in Persepolis],” 63. For, as Nasibi argues, Rahnamā showed the relationship between the mythical Sīyāvash of Shāhnāmah and “today’s humans,” to say “that today, too, Siyavash exists,” but perhaps not in the form of the incumbent king, Mohammad Reza Shah.19Nasībī, “Sīyāvash dar Takht-i Jamshīd [Siavash in Persepolis],” 63. The film’s story and setting, as well as Rahnamā’s modernist approach to collapsing time and space, were innovative for this time period.

Also from the late 1960s, Qaysar (Mas‛ūd Kīmīyāyī, 1969) was one of the formative films of Iran’s alternative cinema, one that similarly drew from Film-Farsi tropes to address the anxieties that gripped the Iranian underclass. Qaysar tells the story of a man trapped in a transitional society that treads between modern values and traditional-familial morals. Upon arriving in Tehran from the booming, oil-producing Abadan where he is employed, Qaysar discovers that his sister committed suicide after being raped and that his brother was killed while defending his sister’s honor. In reaction to this news, Qaysar sees no choice but to take matters into his own hands. Learning the names of the perpetrators of the crime, Qaysar avenges both the lives of his sister and brother and the memory of a forgotten underclass in an almost epic fashion. Qaysar was praised by film critics for its representation of “the blind rebellions and pervasive dead-ends” in the dark underbelly of Iran’s conservative lower classes.20‘Alī Hamadānī, “Hamāsah-i Qaysar va Sīm-i Ākhar” [The Epic of Qaysar and Madness], Nigīn, no. 56 (Day 1348 [December 1969]), 69. Translated by the author. Despite its success at the box-office, Hūshang Kāvūsī censured the film for its connection to Film-Farsi in its depiction of traditional coffeehouses, bath houses, fight scenes, and folkloric elements.21Hūshang Kāvūsī, “Az ‘Dāj Sītī’ tā Bāzārchah-i Nāyib Gurbah” [From “Dodge City” to the Bazaar of Nāyib Gurbah], Nigīn, no. 56 (Day 1348 [December 1969]), 23-24. Translated by the author. Regardless of such criticisms, however, Qaysar staged on the silver screen a neglected community that sought solace in traditional values to combat the annihilation brought about by modern times.

Figure 7: A still from Qaysar (1969). Mas‛ūd Kīmīyāyī, accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=itYE35x-umQ (00:59:57)

Figure 8: A still from Qaysar (1969). Mas‛ūd Kīmīyāyī, accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=itYE35x-umQ (00:38:04)

Another significant film from this period—and perhaps the most well-known of the alternative trend—is Dāryūsh Mihrjū’ī’s Gāv (The Cow, 1969), based on a short story by Ghulām-Husayn Sā’idī, a leftist writer and psychiatrist. At a time when pastoral life and the incorruptibility of peasants was romanticized by alternative and popular filmmakers alike in reaction to rapid urbanization and growing social divides, The Cow’s poetic pessimism about village life was a subversive act against Pahlavi claims to progress and modernization. Mashdī Hasan, a poor villager who lives in a remote and impoverished area, is over-reliant on a single cow as a means for his subsistence. The cow’s mysterious death sparks a psychotic episode in which Mashdī Hasan loses contact with reality—the boundary between human and animal is disrupted and Mashdī Hasan metamorphoses into a cow. Screened at Berlin, Cannes, and Moscow film festivals, the film was praised for its critique of capitalism and imperialism and their alienating effects. Mihrjū’ī saw the demise of his protagonists in films such as The Cow, Āgāy-i Hālū )Mr. Halu, 1971), and Pustchī (The Postman, 1972) to be in reaction to their environments and informed by “historical and social factors.”22Hasan Qulī-Zādah, “Gāv, Hālū, va Pustchī va Sīnimā-yi Mu’allif [The Cow, Halu, and The Postman, and Auteur Cinema],” Sīnimā-yi Āzād, Kitāb-i Duvvum [Free Cinema, Book Two] (Tehran: Sīnimā-yi Āzād Publishing Center, 1351 [1972]), 30. Translated by the author. The absence of the cow, according to Mihrjū’ī, led to the collapse of the boundary between lover and beloved, or signaled a return to the “mother’s womb.” In that sense, Mashdī Hassan’s transmutation can be regarded as a journey towards “perfection” and “transcendence,” or a shift towards “self-reliance” for salvation—an essential third world nationalist response to imperialism.23Qulī-Zādah, “Gāv, Hālū, va Pustchī va Sīnamā-yi Mu’allif [The Cow, Halu, and The Postman, and Auteur Cinema],” 30.

Figure 9: Mashdī Hasan has taken the cow to the river and is washing it with love and enjoyment. Gāv (The Cow, 1969), Dāryūsh Mihrjū’ī, accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d7hTfaEY0lA (00:08:25)

The alternative films of the era were specifically commended for their close connection to Iranian society, culture, and history. Shab-i Qūzī (The Night of the Hunchback, 1965) by Farrukh Ghaffārī was acclaimed in the Free Cinema journal for its similarities to the works of Hitchcock, also praising the film’s “perfect proximity” to “Iranian life.”24Sam (no last name), “Shab-i Qūzī [The Night of the Hunchback],” Sīnimā-yi Āzād, Kitāb-i Avval [Free Cinema, Book One] (Tehran: Sīnimā-yi Āzād Publishing Center, 1350 [1971]), 90-91. Translated by the author. Similarly in Arāmish dar huzūr-i dīgārān )Tranquility in the Presence of Others, 1970), Nāsir Taqvā’ī was commended for having “accessed the culture of his society,” a culture that had “polluted” urban dwellers and convicted them to “a state of dreadfulness.”25Gītī Vahīdī, “Ārāmish dar Huzūr i Fāji’ah” [Tranquility in the Presence of a Catastrophe], Nigīn, no. 96 (Urdībihisht 1352 [April 1973]), 56. Translated by the author. Bahman Farmānārā’s Shāzdah Ihtijāb (Prince Ejtejab, 1974) was also noted for its reliance on Iranian history to narrate “the decline of an aristocratic family in the context of an end of an era,” perhaps signifying the collapse of Iran’s monarchy.26Jamshīd Akramī, “Mīrās-i Tabāh-kunandah” [Corrosive Legacy], Rūdakī, nos 37-38 (Ābān-Āzar 1353 [October- November 1974]), 21. Translated by the author.

A prime example of such close connections was Farīdūn Gulah’s Zīr-i pūst-i shab (Under the Skin of the Night, 1974) which, as the title suggests, delved into the underbelly of Tehran, ripe with desire, crime, and lust for life. In the film’s opening scenes, Gulah compares a beetle’s efforts to make a home in the wild to a man’s attempt at life in Tehran, while an establishing wide shot of Tehran sets the stage for this tale. Under the Skin of the Night follows a day in the life of Qāsim Sīyāh (Qāsim, the Dark), unemployed and homeless, to expose the hardship faced by a young man in a harsh, modernizing city. His austere life is filled with a thirst for living, continuously reflected through sexually evocative scenes quite out of place in a conservative society. Qāsim is reproached by everyone: he is reprimanded by his mother for his unemployment; chastised by other mothers for playing soccer with their kids (and unintentionally injuring them); chased by men for harassing their wives or sisters; pursued by big name criminals for hustling in the streets he grew up in; and beaten up by affluent men who deride him.

Figure 10: A still from Zīr-i pūst-i shab (Under the Skin of the Night, 1974). Farīdūn Gulah, accessed via https://www.radiofarda.com/a/movie-under-the-skin-of-the-night-fereydun-gole/31331680.html

While feeling invisible in the busy streets of Tehran, Qāsim is spotted by a foreign young woman, Sūsan, who seems to be escaping from her past—a relationship perhaps. Despite facing a language barrier, the two strike a friendship and agree to spend Sūsan’s last night in Tehran together. Qāsim looks for a place where they can be sexually intimate but to no avail. In the absence of an actual erotic tryst, they smoke marijuana together and use the respite to imagine their sexual encounter. In the darkness of night, Qāsim and Sūsan cross paths with two affluent young men, whose family employs Qāsim’s mother as a servant. Invited to a villa by the wealthy duo, Qāsim’s jealousy flares as he watches one of them swim alongside Sūsan in the pool. Feeling impotent in front of the upper-class, an enraged Qāsim is eventually beaten up by the two men. Qāsim and Sūsan then leave the house and begin wandering through the streets again.

Scenes of Qāsim’s sobs, accompanied by the loud background noise of the city, highlight his atomization in this unjust society. Only in a few tender moments when the two lovers make out does the uproar of the city quiet—at least until the two are arrested by the police. Adding to his pain, Qāsim is kept in prison while Sūsan is put on her flight back to New York. Finally, in the early hours of the morning when Sūsan is on the plane, Qāsim finds solace in self-pleasure to alleviate the erotic tension and the social and cultural distress that he faced throughout the day. Gulah’s subject matter, techniques of filmmaking, and dream-like sequences were viewed as unprecedented and avant-garde. His depiction of the neglected underclass, antiheroes in their flaws and despair, challenged the Pahlavi state’s propaganda and social taboos, calling for a collective national consciousness for rebellion.

Alternative Cinema and the Rumblings of Revolution

As Iranian discontent with the regime of the Shah became more pronounced, films also became more conspicuously political, and at times religiously-attuned. As political activism and protests thrived in the streets of Tehran, films grew more revolutionary, and sometimes rife with religious undertones that paralleled the religious underpinnings of revolutionary activism. Tangsīr (1974), Sāyah-hā-yi buland-i bād (Tall Shadows of the Wind, 1978), and O.K. Mister (1979), were some of the films that grasped the collective angst and revolutionary spirit of their era. Based on a novel of the same title by Sādiq Chūbak, Amīr Nādirī’s Tangsīr portrays the battle of Zā’ir Muhammad, an honest veteran from Tangistān city of Bushehr province, against the corrupt, wealthy elite in southern Iran. The affluent nobility, who symbolize an unjust capitalist social system, have stolen Zā’ir Muhammad’s life savings. Outraged by the injustices he is subject to, he decides to pursue justice through violent retribution. Before setting out on his vendetta, he pays a visit to the local mosque and shrine to receive the blessing of the village’s religious superior. Zā’ir Muhammad drinks water from the mosque’s water reservoir and hesitates over a painting of the Shi’ite saint, Imam Hussein, which conjures an analogy to the events of Karbala. He then digs out his gun and axe and takes revenge against those who have oppressed him and other members of his community. Zā’ir Muhammad’s courageous acts inspire other villagers to also rise up and demand justice from the village nobility in the form of a cinematic rebellion.

Bahman Farmānārā’s Tall Shadows of the Wind also tells the story of a young man in a village who fights against injustice, this time imposed by a self-made cult. The people in ‛Abd-Allāh’s village have longed for a saviour to deliver them from their problems. To that end, the superstitious residents prop up a scarecrow at the village’s entrance for protection. While initially valorized, the scarecrow gradually unleashes a reign of terror upon the villagers who become consumed by fear. Arguably standing in for Mohammad Reza Shah, the scarecrow has supernatural powers that violently pound the people of the village, not unlike what SAVAK (a secret police, security, and intelligence service of the Shah) did to political activists. Strange and mysterious encounters with the scarecrow lead variously to psychosis, death, and, at one point, an unwanted pregnancy experienced by ‛Abd-Allāh’s sweetheart, Nargis. After speaking with a few other villagers, ‛Abd-Allāh takes up his plow, representing peasant valor, to battle the scarecrow.

Figure 11: A still from Sāyah-hā-yi buland-i bād (Tall Shadows of the Wind, 1978). Bahman Farmānārā, accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bfisG2HDaLc (01:34:45)

After he is fatally injured by the scarecrow, ‛Abd-Allāh imagines, and perhaps leads, a revolution against the tyranny of the scarecrow in his mind. In his hallucinatory dream, villagers dressed in red follow ‛Abd-Allāh and set fire to scarecrows of varying sizes. ‛Abd-Allāh smiles after this dream-like sequence to signal a victory before he passes away. The village’s headmaster, Muhammad, is deeply moved and inspired by ‛Abd-Allāh’s self-sacrifice. Later in his classroom, he writes the last verse from Ahmad Shāmlū’s 1969 poem, “An Anthem for a Luminous Man Who Went to the Shadows,” which reads “The sea is jealous of the sip you took from the well,” hinting at ‛Abd-Allāh’s greatness.27Ahmad Shāmlū, “Surūd barāy-i mard-i rawshan ki bi sāyah raft [An Anthem for a Luminous Man Who Went to the Shadows],” The Official Website of Ahmad Shāmlū, accessed 19 May, 2024, http://shamlou.org/?p=167. Translated by the author. Taken together, the film’s numerous symbolisms allude to the multifaceted revolutionary zeitgeist in the streets of Tehran at that time. The colour red worn by the film’s rebels denote socialist undertones that were prominent among many of the cultural thinkers and activists of the period, and the moustaches sported by both ‛Abd-Allāh and Muhammad arguably point to the leftist backgrounds of these two young men. On the other hand, the names of the two men have religious implications as ‛Abd-Allāh was the name of the father of the Prophet of Islam, Muhammad.28In a question and answer after the screening of Tall Shadows of the Wind at Museum of Modern Art (New York), on 11 November 2023, Farmānārā specifically indicated his intentional use of these names for his film’s heroes. In that sense, ‛Abd-Allāh’s sacrifice inspires Muhammad’s calling for a new order against tyranny. In this light, the film’s religious symbolism served as a nod to political Islam as a means to break free from a tyrannical monarchy and imperialism.

Conclusion

By the late 1960s and early 1970s, the films of Iran’s alternative filmmakers were screened at prominent international film festivals such as Cannes, Berlinale, and Tehran International Film Festival. Applauded and recognized by film critics, some alternative films also won international awards. Mihrjū’ī’s The Cow, ‛Abbās Kīyārustamī’s Tajribah (The Experience, 1973), Bahram Bayzayi’s Gharībah va Mih (The Stranger and the Fog, 1974), and Bahman Farmānārā’s Prince Ehtejab (1974) and Tall Shadows of the Wind were among alternative films showcased at Cannes, while Suhrāb Shahīd Sālis’s Yik Itiffāq-i sādah (A Simple Event, 1974) and Tabī‛at-i bī-jān (Still Life, 1974) and Parvīz Kīmīyāvī’s Bāgh-i sangī (The Stone Garden, 1976) were screened at the Berlinale. The connection between Iranian and global arthouse films did not go unnoticed, prompting the British film critic John Gillett to compare the alternative films of Iran to those of François Truffaut and Akira Kurosawa.29John Gillett, “Dar Hāshīyah-i Jashnvārah-i Kan: Dar Intizār-i Zuhūr-i Āsārī Buzurg az Sīnimā-yi Īrān” [On the Sidelines of the Cannes Film Festival: In Anticipation of Great Works from Iranian Cinema], Sīnimā 54 [Cinema 54], no. 18 (Murdād-Shahrīvar 1354 [August-September 1975]), 60. Indeed, in the eyes of international film critics, the works of Shahid Sales were reminiscent of Truffaut, Mihrjū’ī’s films were likened to those of Luis Buñuel, while Parvīz Kīmīyāvī’s films such as Mughulhā (The Mongols, 1973) were thought to be informed by Godard’s cinema.30Bengt Forslund, “Matbūʻāt-i Jahān va Sivvumīn Jashnvārah-i Jahānī-yi Fīlm-i Tihrān” [World Press and the Third Tehran International Film Festival], Sīnimā 54 [Cinema 54], no. 18 (Murdād-Shahrīvar 1354 [August-September 1975]), 68-69. Following the “combinatorial spirit” that Farīdūn Rahnamā had encouraged in the late 1960s, Iranian filmmakers engaged with the works of prominent international filmmakers and foregrounded the Iranian experience—a predicament that was informed by domestic conditions and international politics.

Further, alternative filmmaking in Iran had different trajectories that at times turned into distinct filmmaking trends. While some focused their visual offerings on films that traversed between popular and realist cinema, others concentrated on making arthouse films that catered to a limited audience, while still others engaged in experimental filmmaking that was supported by the art community. Thus, the combination of Iran’s contentious love affair with cinema and film experimentation, a boom in state, international, and private funding for filmmaking in the 1960s and 1970s, and familiarity with global cinemas that spoke to current socio-political struggles and trends paved the way for the crafting of alternative films in Iran.

Informed by criticisms aimed at popular films, alternative cinema filmmakers functioned to distance themselves from charges of imitation and mimicry. Stirred by third world nationalist and leftist debates that called for struggle against imperialism and reliance on the self, the filmmakers of this era looked to their own history, culture, and society for inspiration. However, the struggle of these filmmakers was not that different from fellow filmmakers in other parts of the world, especially at a time when art, history, and politics were closely intertwined. Alternative films engaged with post-WWII ideological trends in filmmaking that showcased the poor, marginalized, and fallen. Hence, alternative films became vernacular-cosmopolitan offerings that not only looked to the past, but also investigated and questioned it in order to imagine a new horizon of expectation, a new future for Iran.

Cite this article

This article explores Iran’s alternative cinema movement of the 1950s–1970s, which emerged in response to the commercial dominance of “Film-Farsi.” Filmmakers like Dāryūsh Mihrjū’ī and Bahman Farmānārā drew on global cinematic trends, including Italian Neorealism and French Nouvelle Vague, to create socially conscious films that addressed class struggles and cultural tensions. The article highlights the movement’s vernacular-cosmopolitan nature, situating it as a precursor to the revolutionary spirit and a transformative force in Iranian and global cinematic discourse.