Apartment Dramas in Iranian Cinema (2009-present)

Figure 1: A screenshot from the film Judā’ī-i Nādir az Sīmīn (A Separation, 2011), directed by Asghar Farhādī.

The turbulent events that unfolded during the Green Movement in Iran—ignited by the disputed results of the 2009 presidential elections—had a lasting impact on the country’s social and political fabric. The middle class, closely associated with the movement’s ideals, notably found expression in the rise of apartment dramas in Iranian cinema from the late 2000s to the mid-2010s.

This article examines the occurrence of apartment dramas following the Green Movement, analyzing the convergence of socio-political changes, economic factors, and strategic choices made by filmmakers. This analysis delves into key factors which influenced the emergence of this cinematic trend, followed by a comprehensive examination of notable films released after the Green Movement, such as A Separation (2011),1Asghar Farhādī, dir. A Separation [Judā’ī-i Nādir az Sīmīn] (Tehran: Asghar Farhādī Productions, 2011). Felicity Land (2011),2Māzīyār Mīrī, dir. Felicity Land [Sa‛ādat Ābād], (Tehran: Humāyūn As‛adīyān, 2011). Melbourne (2014),3Nīmā Jāvīdī, dir. Melbourne (Tehran: Qāb-i Āsimān Productions, 2014). and Blind Spot (2017).4Mihdī Gulistānah, dir. Blind Spot [Nuqtah-yi Kūr], (Tehran: Mantra Film Productions, 2017). Within the context of these films, themes such as the portrayal of isolated characters, socio-economic class disparity, marital problems, and character development are scrutinized. Ultimately, the essay concludes with an analysis of the factors that have contributed to the decline in the production of apartment dramas in Iranian cinema since the mid-2010s. This exploration reveals the intricate correlation between Iranian cinema and societal shifts following the Green Movement.

What is Apartment Drama?

The production of films centered on a residential complex has a significant historical background in Iranian cinema. Some of these works have been narrated in apartments. However, this criterion alone is insufficient to classify a film as an “apartment film,” or more specifically, an “apartment drama.”

In her book titled The Apartment Plot: Urban Living in American Film and Popular Culture, Pamela Robertson Wojcik examines the characteristics of American apartment films, which can also be applied to Iranian cinema’s apartment films and dramas. Generally, an apartment film can be defined as a cinematic work in which an apartment figures as more than just a setting. What is called “the apartment plot” revolves around the central device of the apartment, which plays a vital role in shaping the narrative.5Pamela Robertson Wojcik, The Apartment Plot: Urban Living in American Film and Popular Culture, 1945 to 1975 (Durham: Duke University Press, 2010), 3, https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822392989. Apartment buildings may encompass high-rise structures with or without doormen and can be constructed in various styles.6Wojcik, The Apartment Plot, 3. An apartment is thus visually distinct from constructions such as suburban houses or communal residences.

The second characteristic of American apartment films is that apartments are generally considered as the residence of the working or middle class.7Wojcik, The Apartment Plot, 3. However, workers in Iran are generally regarded as part of the lower socio-economic class. Therefore, in Iran, when we encounter a film that combines the lives of workers and apartments, a common inference arises in the viewer that one is watching a film centered on individuals striving to attain middle-class amenities, rather than individuals who have a stable position in the middle class. In a more general sense, according to Wojcik, apartment films are differentiated by their embodiment of the ideology of urbanism.8Wojcik, The Apartment Plot, 7.

When discussing “apartment dramas,” it is necessary to consider an additional criterion beyond those generally considered for apartment films. Apartment dramas explore the daily lives of individuals from the middle class, expressing concerns and issues that numerous members of the middle class are grappling with. This genre encompasses a broad range of issues, spanning from financial crises to moral dilemmas.

Figure 2: A screenshot from the film Judā’ī-i Nādir az Sīmīn (A Separation, 2011), directed by Asghar Farhādī.

The Middle-Class Critique in Pre-Green Movement Apartment Films

Prior to the Green Movement, apartment films were not absent from Iranian cinema. The proliferation of apartment culture in the 1980s was accompanied by the production of the film Tenants (1987; figure 3).9Dāryūsh Mihrjū’ī, dir. Tenants [Ijārah-nishīn-hā], (Tehran: Pakhshīrān Corporation, 1987). Tenants experienced considerable commercial and critical success, which led to the emergence of multiple social-themed apartment films in the latter part of the 1980s.

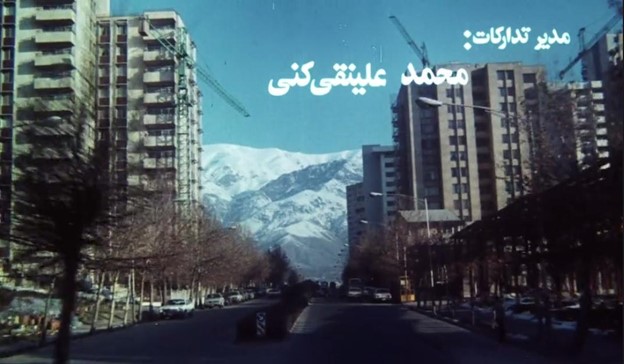

Figure 3: Mihrjū’ī repeatedly highlights apartments that have been built or are currently under construction in various areas of the city in the title sequences of Tenants, aiming to illustrate the expansion of apartment living in Tehran. Ijārah-nishīn-hā (Tenants, 1987), Dāryūsh Mihrjū’ī, accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MEcVGVWcpEw (00:00:54).

Tenants is a comedic narrative that explores the challenges faced within a four-story apartment building situated beyond the urban boundaries of Tehran. The structural integrity of this apartment building is in a precarious state, necessitating the collective effort of all its residents for its restoration. However, the constant conflicts among these neighbors hinder the renovation of the apartment to the extent that the building eventually collapses (figure 4).

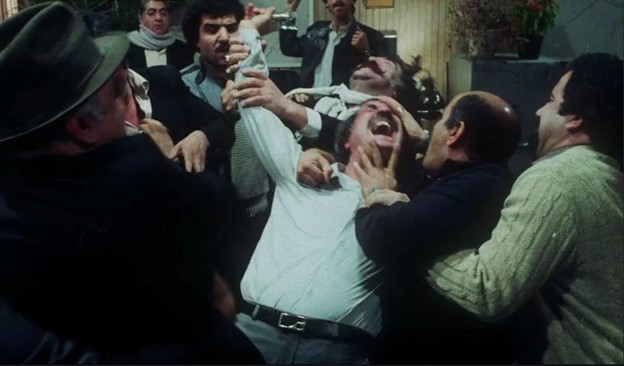

Figure 4: A recurring motif in the film Tenants is the portrayal of a large number of individuals involved in debates or conflicts. Ijārah-nishīn-hā (Tenants, 1987), Dāryūsh Mihrjū’ī, accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MEcVGVWcpEw (00:20:18).

Mihrjū’ī directed his attention towards the incompatibility of individuals residing within this apartment complex, offering an analysis of a middle class that has lost its footing and is grappling to preserve its fragile status. The individuals within this class encounter conflicts amongst themselves in different circumstances, resorting to reconciliation solely when all other alternatives have been exhausted.10Hamidreza Sadr, Darāmadī bar Tārīkh-i Sīyāsī-yi Sīnimā-yi Īrān [An Introduction to the Political History of Iranian Cinema], (Tehran: Nay, 2006), 285-286. Mihrjū’ī thus offers a sarcastic critique of the lifestyle of the Iranian middle-class apartment dwellers in Tenants.

Subsequent apartment films, following the success of Tenants, have maintained this particular attribute. Apartment No. 13 (1990)11Yadallāh Samadī, dir. Apartment No. 13 [Āpārtimān-i Shumārah-yi 13], (Tehran: Hamrāh Film Production Group 1990). is a case in point. The storyline of this film revolves around a modest rural individual who owns an apartment in Tehran. In order to raise funds for his wedding, he heads to Tehran to sell his apartment. However, the apartment’s visual conditions are inadequate, and the residents’ behaviors hinder the success of the protagonist in selling the property. In Apartment No. 13, similar to Tenants, we encounter a community of middle-class individuals residing in an apartment complex. However, it seems that they do not possess the culture associated with middle-class apartment dwellers. Thus, in films such as Tenants and Apartment No. 13, the portrayal of chaotic relations of urban life becomes a pretext for emphasizing the shortcomings and problems of the aspiring middle class. This approach bears resemblance to that adopted in the subsequent wave of apartment dramas following the Green Movement, albeit with notable distinctions.

The Reforms, the Green Movement, and the New Wave of Apartment Dramas

As the trend for producing satirical apartment comedies diminished in the early 1990s, Iranian filmmakers gradually refrained from delving into the production of apartment films. Instead, the production of apartment-themed works in the 1990s gained more traction within television series. However, these television series can hardly be categorized as apartment dramas. Despite addressing the lives of individuals belonging to the middle class, one can rarely find explicit engagement with specific middle-class issues in these works. These series typically focused on common attributes observed across various socio-economic strata, without being restricted to the middle class.

The state of Iranian cinema during the late 1990s and early 2000s was intertwined with the broader societal changes marked by the unexpected victory of Sayyid Muhammad Khātamī, a reformist candidate, in the 1997 presidential election. This win signaled growing concerns within the urban middle class, transcending mere material issues. The formation of the reformist movement was driven by multiple factors, including urbanization, the rise of the middle and educated classes, a communications revolution, and the embrace of human rights and democratic values as cultural norms.12Akbar Ganji, “Qatl-hā-yi Zanjīrah-i, Intikhābāt, va Tahdīd-hā,” [“Chain Murders, Elections, and Threats”] in ‛Ālījināb-i Surkhpūsh va ‛Ālijinābān-i Khākistarī: Āsīb-Shināsī-i Guzār bi Dawlat-i Dimukrātīk-i Tusi‛ah-garā [The Red Eminence and the Gray Eminences: Pathology of Transition to the Developmental Democratic State], (Tehran: Tarh-i Naw, 2000), 218. These societal shifts found resonance in Iranian cinema of the period, which produced films closely aligned with middle-class concerns. However, the apartment, as a cinematic motif, did not prominently symbolize the middle-class lifestyle during this era.

However, the articulation of civil and political demands by the middle class following 1997 led to two notable social movements in 1999 and 2009, where the middle class assumed a pivotal position.13Parviz Sedaqat, “Bast va Qabz-i Tabaqah-yi Mutavasseṭ dar Īrān” [“The Expansion and Contraction of the Middle Class on Iran”], Radio Zamaneh, February 24, 2021. https://www.radiozamaneh.com/584759/ The widespread protests against the results of the presidential election in 2009 became widely recognized as the Green Movement. Shortly after the Green Movement, a new wave of apartment dramas emerged in Iranian cinema.

Catalysts Behind the Rise of Apartment Dramas

The onset of the post-Green Movement era of apartment dramas can be traced back to the year 2010. During this year, the film A Separation was made and was first screened at the twenty-ninth Fajr Film Festival for an Iranian audience. The film was instantly met with widespread critical acclaim. Shortly thereafter, the Iranian audience was inundated with a series of apartment dramas that can be characterized by their shared themes of the middle class, familial struggles, and moral dilemmas.

Besides the critical success generated by A Separation, several other factors affected the boom of apartment dramas. The first issue relates to the budget of film productions. Iranian cinema experienced an economic crisis during the late 2000s and early 2010s. Annual cinema audiences dropped significantly from over 81 million during the period spanning March 1990 to March 1991 (equivalent to the year 1369 Sh.)14Zohreh Fathi and Pante’a Khamooshi Esfahani, “Sālnāmah-yi Āmārī-yi Furūsh-i Fīlm va Sīnimā-yi Īrān Sāl-i 1369” [“Statistical Yearbook of Iranian Film and Cinema Sales in 1369”], Iranian Organization of Cinema and Audiovisual Affairs (2016): 2. https://apf.farhang.gov.ir/ershad_content/media/image/2017/09/531239_orig.pdf to less than 11 million between March 2010 and March 201115Zohreh Fathi and Pante’a Khamooshi Esfahani, “Sālnāmah-yi Āmārī-yi Furūsh-i Fīlm va Sīnimā-yi Īrān Sāl-i 1389” [“Statistical Yearbook of Iranian Film and Cinema Sales in 1389”], Iranian Organization of Cinema and Audiovisual Affairs (2018): 2. https://apf.farhang.gov.ir/ershad_content/media/image/2018/08/655213_orig.pdf. and less than 10 million between March 2013 and March 2014.16Zohreh Fathi and Pante’a Khamooshi Esfahani, “Sālnāmah-yi Āmārī-yi Furūsh-i Fīlm va Sīnimā-yi Īrān Sāl-i 1392” [“Statistical Yearbook of Iranian Film and Cinema Sales in 1392”], Iranian Organization of Cinema and Audiovisual Affairs (2018): 2. https://apf.farhang.gov.ir/ershad_content/media/image/2019/12/922290_orig.pdf. Considering the significant role of the government in the production and distribution of films in Iran, it was possible for films with government support to still be produced with facilities similar to those of the Iranian cinema boom period. However, films lacking the intervention of government institutions were unable to achieve this standard during the economic crisis.

During Muhammad Rizā Ja‛farī Jilvah’s term as Cinematic Deputy Minister of Culture and Islamic Guidance (2005-2009), the budget for Iranian cinema experienced a notable increase. However, a decision was made to allocate this budget towards the production of a few larger-scale films, deviating from the usual productions in Iranian cinema.17Babak Ghafoori Azar, “Raft-u-Āmad dar Imārat-i Khīyābān-i Kamāl-al-Mulk” [“Commuting in the Building on Kamal-ol-Molk Street”], 24 Monthly 36 (2010): 25. Given the circumstances, filmmakers who received limited government support found that restricting locations, reducing the cast, and cutting costs on equipment and facilities rental were among the few remaining strategies to minimize film production expenses.

Figure 5: A screenshot from the film Judā’ī-i Nādir az Sīmīn (A Separation, 2011), directed by Asghar Farhādī.

The filmmakers also took into consideration the concerns of the middle class in Iran. The 2009 Green Movement was instrumental in driving societal shifts. It is widely believed that the movement was led by the urban middle class. As an example, Kevan Haris points out that, “while a broad cross-class coalition of individuals participated in the Green Movement at its peak, the core of the movement was located in the country’s middle classes.”18Kevan Haris, “The Growing Social Power of Iran’s Middle Class,” UC Press Blog, August 14, 2017. https://www.ucpress.edu/blog/29179/the-growing-social-power-of-irans-middle-class Mahmood Monshipouri also points to the resemblance between the Green Movement and the 1999 student protest movement: “The 1999 student protests were followed by yet another round of protests a decade later in 2009, also known as the Green Movement, both of which were led by the urban modern middle class.”19Mahmood Monshipouri, “What Is Different about These Protests in Iran?,” Center for Middle Eastern Studies: UC. Berkeley, November 9, 2022, https://cmes.berkeley.edu/what-different-about-these-protests-iran As mentioned before, the 2009 movement can be seen as one of the culminations of a path that began in 1997 with the widespread participation of the urban middle class in that year’s presidential election and the beginning of the so-called reform era.

Considering the significance of the urban middle class’s concerns during that time, the emergence of apartment dramas appears to be well-founded. The concept of an apartment implies a specific constraint on space. Consequently, despite the transformation of numerous buildings in prosperous regions of prominent Iranian cities into luxury apartment complexes in recent decades, the general perception of the audience does not associate apartment living with the upper classes. Further, when examining the architectural contrast between middle-class neighborhoods and impoverished areas in cities such as Tehran, considering that neighborhoods in impoverished areas have not developed as much as middle-class neighborhoods and primarily consist of modest homes or aging complexes with less visually striking exteriors, it becomes apparent that the prevailing perception of an apartment in Iran implies a baseline provision of essential living facilities. Given this cultural imaginary, filmmakers could easily convey the economic and social class of the characters by simply selecting an average-sized apartment.

The Solitude of Characters

The emerging trend in apartment dramas after the Green Movement involved films that exhibited substantial differences in nature compared to previous examples. During the late 1980s, Iranian apartment comedy-dramas revolved around the interactions of neighbors residing in an apartment complex. However, in apartment dramas following the Green Movement, the focus shifted towards a smaller group of individuals and families, sometimes solely highlighting the challenges faced by a couple. Rather than attempting to depict the various dimensions of the relationships between characters, the narrative revolved around one or two specific crises. Further, these crises often possessed a prominent moral dimension, with economic matters also being predominantly viewed through a moral lens.

The focus on select characters and the reduced involvement of neighboring characters in driving the narrative has led to the portrayal of individuals in post-Green Movement apartment dramas as socially isolated. The apartment comedy-dramas of the 1980s depicted members of the middle class as individuals who, despite numerous partial differences, shared significant collective concerns. However, regarding characters in apartment dramas post-2010, it seems that they reside in secluded islands, disconnected from their neighbors. These individuals have become deeply engrossed in their own spheres, and their interactions with other members of their social class appear to be restricted. While the apartment films of the 1980s were filled with bustling scenes depicting people’s engagements (figure 4), post-Green Movement apartment dramas present settings that emphasize the separation among individuals (figure 6).

Figure 6: Asghar Farhādī repeatedly emphasizes the personal solitude of characters in A Separation through elements such as framing and the bars of windows. Judāyī-i Nādir az Sīmīn (A Separation, 2011), Asghar Farhādī, Accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bMJ48FeaHxw&t=207s (00:47:59).

A Separation and the Ethical Concerns of the Middle Class

One common aspect found in numerous apartment dramas after 2009 is the focus on the emergence of moral dilemmas within the middle class. The film A Separation held great significance during that period as it established a paradigm for Iranian filmmakers in depicting such challenges.

It is worth noting that Asghar Farhādī had portrayed the ethical crises faced by the middle class in Iranian society in his film Chahār’shanbah-sūrī (Fireworks Wednesday, 2006) before the Green Movement. The film introduces us to the marital challenges faced by a middle-class couple named Muzhdah (Hadīyah Tihrānī) and Murtizā (Hamīd Farrukhnizhād) through the viewpoint of Rūhī (Tarānah ‛Alīdūstī), a working-class individual working as a maid in their home. However, ethical interactions between characters from the middle and lower economic classes were infrequent in Fireworks Wednesday. Rūhī’s portrayal primarily revolved around her role as an observer. Instead, Farhādī preferred to concentrate on the marital crisis of the middle-class couple.

That Farhādī briefly references Fireworks Wednesday in the opening of A Separation establishes a connection between the ethical dimensions of both films. The opening scene of A Separation depicts the act of duplicating documents from various individuals to fulfill administrative procedures such as divorce. Among these, there are images of the initial pages of the identification cards belonging to Muzhdah and Murtizā from Fireworks Wednesday. This reference may suggest that they are undergoing divorce proceedings.

Figure 7: A screenshot from the film Chahār’shanbah-sūrī (Fireworks Wednesday, 2006), directed by Asghar Farhādī.

A Separation is an extension of Farhādī’s focus on the familial issues of the middle class. In a manner reminiscent of Fireworks Wednesday, the arrival of a working-class individual into the residence of a middle-class couple allows us to become more acquainted with the challenges of their marital life. However, the distinction lies in the fact that in A Separation, the socio-economic disparity of the main characters assumes a more crucial role in the progression of the narrative.

The film’s storyline revolves around two families. The first family, comprising Nādir (Paymān Muʿādī), Sīmīn (Laylā Hātamī), and their daughter Tirmah (Sārīnā Farhādī), belongs to the middle class, while the second family, consisting of Rāzīyah (Sārah Bayāt), Hujat (Shahāb Husaynī), and their daughter Sumayyah (Kīmīyā Husaynī), belongs to the lower class of society. Nādir and Sīmīn are experiencing a conflict with one another and seem to be on the brink of separation. Sīmīn’s departure from their home leads Nādir to hire Rāzīyah (who, due to Hujat’s unemployment, needs to seek income) in order to take care of his father (‛Alī-Asghar Shahbāzī). However, when it seems that Rāzīyah has not taken the matter seriously and her negligence has resulted in the injury of Nādir’s father, Nādir becomes entangled with her and forcefully throws her out of the house. Following this confrontation, it becomes evident that Rāzīyah has suffered a miscarriage. This incident marks the beginning of a crisis that greatly impacts the lives of all the primary characters.

As the storyline of A Separation progresses, it extends beyond the boundaries of Sīmīn and Nādir’s apartment; however, the apartment plays a crucial role in shaping the narrative and enhancing our comprehension of the characters. Therefore, A Separation can be regarded as an exemplification of an apartment drama. A significant portion of the film’s introduction takes place within Sīmīn and Nādir’s apartment. In this introduction, we observe a series of parallel events that establish the narrative framework of the film. The sequence of key events in the initial minutes of the film begins with the depiction of the conflict between Nādir and Sīmīn, and subsequently progresses with the introduction of Rāzīyah. The display of Rāzīyah’s religious concerns is a key concept of this expansion. Despite her financial need for the income, she is deeply troubled by the requirement of being alone with a strange old man in his house each day and having to physically assist him with bathing. The conflict between Nādir and Rāzīyah also stands out as another significant aspect of this development.

A Separation begins by depicting the marital crisis of a couple but gradually involves numerous other characters besides them in their own crises. This is a distinguishing feature that sets A Separation apart from Fireworks Wednesday. In Fireworks Wednesday, Rūhī essentially holds the position of an observer. However, characters like Hujat and Rāzīyah in A Separation face different crises compared to the problems of Nādir and Sīmīn. The film equally focuses on their life crises as it does on the middle-class couple. This approach allows Farhādī to perceptibly expand the initial story and address a spectrum of social problems. Several other Iranian filmmakers of apartment dramas post-2009 have utilized a similar pattern, starting with depicting a couple’s issues and then introducing new characters with their own crises to portray a diverse range of societal dilemmas within the cinematic narrative. This framework is integral to how A Separation has contributed to shaping certain patterns within Iranian apartment dramas after 2009.

Class Disparity in A Separation

A Separation transcends the mere portrayal of class issues and raises the question of class disparity. As mentioned before, of the two main couples in the film, one appears to be part of the middle class, while the other couple originates from the lower class. Not only do these two couples clash with representatives of the other class throughout the film, but they also have disagreements amongst themselves. An important aspect to consider when comparing the two couples is the disparity in the origins of their conflicts.

The fundamental conflict between Hujat and Rāzīyah throughout the film is related to financial matters. Rāzīyah is compelled to work as a housekeeper for Nādir due to a financial crisis, despite this conflicting with her religious beliefs and Hujat’s opposition. At one point in the film, Rāzīyah mentions that she cannot continue working in Nādir’s house, but the ongoing economic problems and Hujat’s unemployment force her to return. It is during this period of return that the miscarriage occurs.

Even in the final scene featuring Hujat and Rāzīyah, the emphasis is placed on the role of economic problems in their conflict. This scene is where Hujat, due to his financial circumstances, agrees to drop the complaint against Nādir in exchange for receiving some money as compensation. In the last moment, Nādir requests Rāzīyah to take an oath affirming that the miscarriage she suffered was the result of the blow delivered by Nādir. As per Nādir’s statement, if Rāzīyah were to take the oath, he would provide compensation to both her and Hujat for the damages incurred. Hujat wants Rāzīyah to compromise her beliefs and take the oath. However, Rāzīyah remains unconvinced of Nādir’s culpability and therefore refrains from swearing.

Figure 8: A screenshot from the film Judā’ī-i Nādir az Sīmīn (A Separation, 2011), directed by Asghar Farhādī.

In contrast, while representatives of the middle class are not immune from financial difficulties, non-material concerns such as conscience, morality, and reputation remain fundamental to this social group. If the financial difficulties are what pressures Rāzīyah to compromise her beliefs throughout the film, Nādir’s problems arise from non-material issues. Nādir mentions several times throughout the film that he is not unable to pay the fine, but he is reluctant to do so until he is sure of his guilt in the case. Moreover, the disagreement between Nādir and Sīmīn, unlike the final conflict between Hujat and Rāzīyah, stems not from financial considerations but from fundamentally ethical concerns. Nādir’s inability to leave his father and go abroad contrasts with Sīmīn’s decision to immigrate, driven by her concern for her child’s well-being in a chaotic environment. Farhādī himself explained this conflict by citing an example:

During Sīmīn’s initial appearance following the credits… Sīmīn comes up the stairs; we see two workers carrying a piano and blocking her way. She comes up the stairs and an argument breaks out between them over the amount of the fee for an extra floor; whether they are right or wrong, Sīmīn says, “I’ll give you this money. Open the way.” If Nādir had been in Sīmīn’s place in this scene, it was impossible that he would have given this money; and this is the difference between Nādir and Sīmīn.20Esmaeil Mihandoost, Rū-dar-rū bā Asghar Farhādī [Face-to-Face with Asghar Farhadi], (Tehran: Chatrang, 2021), 215-216. Translated by Aria Ghoreishi.

By depicting these conflicts between the two main couples in A Separation, Farhādī effectively communicates a comprehensive representation of the concerns specific to each social class, while also highlighting the individuality of each character and the differences among the members of each of these social classes.

Despite the differences between the main characters of A Separation, a recurring theme is their reliance on deception or concealment to pursue their objectives. This pattern is notably illustrated in the actions of Nādir and Rāzīyah. For instance, Nādir conceals his knowledge of Rāzīyah’s pregnancy, while Rāzīyah delays disclosing the accident until later in the film. Furthermore, Rāzīyah keeps her occupation as a maid in Nādir’s household hidden from Hodjat.

Nevertheless, the internal conflict highlighted in A Separation is between personal principles and the desire to conceal information. Despite their different social backgrounds, Nādir and Rāzīyah appear to have the closest bond among the characters in the film. They both have personal principles that they try to uphold under any circumstances. In the film, both characters deviate from those principles on occasion due to personal or family reasons. However, ultimately, both characters prioritize their moral convictions over their immediate concerns. Regarding Nādir, one aspect of this decision becomes evident when, in response to Hujat and Rāzīyah’s complaint against him, he decides to file a counter-complaint against Rāzīyah. From Nādir’s perspective, Rāzīyah’s absence from the house during working hours leads to Nādir’s father falling from the bed. Since Rāzīyah (to prevent Nādir’s father, who suffers from Alzheimer’s, from leaving the house) has tied his hands to the bed, this negligence had resulted in Nādir’s father getting injured. However, at the last moment, Nādir prevents the doctor from examining the bruises on his father’s body due to uncertainty regarding Rāzīyah’s negligence. Similarly, Rāzīyah refuses to take an oath at the film’s conclusion. Instead of making a decision for immediate undeniable benefits, both Nādir and Rāzīyah choose to take an action they deem right from their perspective, even if it leads to short-term losses for them.

Marital Turmoil and Striving for Upward Mobility

The issue of social class disparity and the combination of material and moral concerns was also seen in other apartment dramas in the late 2000s and early 2010s. For example, in the film Blind Spot,21The film Blind Spot was produced in 2015 but premiered on screen with a two-year delay in 2017. we face the story of a couple named Khusraw (Muhammad-Rizā Furūtan) and Nāhīd (Hānīyah Tavassulī). Their financial situation is unstable. Khusraw is forced to work in the demanding job of underwater welding to earn a small income to keep their lives going. Meanwhile, Nāhīd is forced to prepare a complete financial report for Khusraw every month to quell Khusraw’s constant and insane doubt and assure him that the household’s money is being spent in the right place. The combination of unstable economic conditions and Khusraw’s moral uncertainty about his wife leads to a crisis that ensues during the gathering of Khusraw and Nāhīd’s relatives in their house for a birthday party.

While Khusraw and Nāhīd live neither in an impoverished neighborhood nor on the outskirts of the city, the film’s focus on their financial challenges indicates that they are struggling to maintain a middle-class lifestyle. During the birthday celebration, we realize that the supporting characters of Blind Spot also exhibit a combination of material and moral concerns. For example, Khusraw’s sister, Parvānah (Shaqāyiq Farahānī), who has a narcissistic personality, sells her jewelry despite the financial crisis that has occurred to her family, in order to buy an expensive gift for her niece that she cannot afford and thereby to project a deceptive representation of her economic status. Conversely, Parvānah and Khusraw’s brother, Nādir (Muhsin Kīyā’ī), is initially not concerned with his social standing and has a carefree nature. However, upon discovering Parvānah’s generous gift, he becomes embarrassed and then wishes to contribute a larger sum as a birthday present. In this manner, the makers of Blind Spot try to address the problem of keeping up with the Joneses.

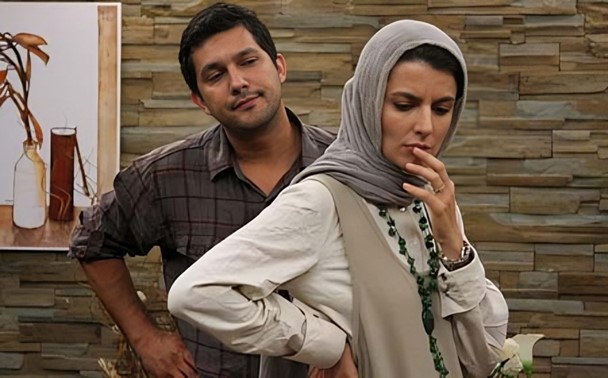

Like Blind Spot, the film Felicity Land is another post-2009 apartment drama that takes into account social class mobility. The film narrates the tale of a gathering where three couples are in attendance. These couples maintain a close friendship and appear to enjoy a standard of living that slightly exceeds the middle-class threshold. At the onset of the event, everything seems to be in order. Apparently, all of those individuals have established positive relations with one another, and we can perceive a sense of intimacy among them. However, gradually,long-standing disparities among them become apparent. Similar to Blind Spot, Felicity Land revolves around the integration of material challenges and ethical predicaments, portrayed through the perspective of striving for upward mobility. Additionally, a pattern is utilized in Felicity Land that we noticed in A Separation and Blind Spot. It involves starting the story by depicting the marital issues of a couple, (in this case, Muhsin, played by Hāmid Bihdād, and Yāsī, played by Laylā Hātamī), and then expanding it to include their acquaintances. Despite the absence of explicit reference to the couple’s problems in the early minutes of Felicity Land, there are indications implying suboptimal living conditions for them (figure 9).

Figure 9: In the initial minutes of Felicity Land, there are indications that the marital conditions of the characters are not as desirable as they try to pretend. The broken mirror in Yāsī and Muhsin’s room subtly suggests that the two have recently had a conflict. Sa‛ādat Ābād (Felicity Land, 2011), Māzīyār Mīrī, accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bIjeDU7nQBg (00:03:30).

Felicity Land can be regarded as a film about an emerging class that does not know its place properly. In an interview during the public screening of Felicity Land, director Māzīyār Mīrī provided a description of how the middle class is dealt with in this film:

Lying and deception are completely institutionalized in our society; and that is by the newly emerged middle class. Fifteen or twenty years ago, or much earlier, we had a middle class that was rooted, had authenticity, and it was clear where it belonged. A middle class has emerged after that that has no roots and is very dangerous, because it crushes everything, puts its foot on the shoulder of wife and children and friends and everything, and goes up, because its intention is only to go up and it does not have a concern for culture and these things either.22Nima Abbaspoor, “Man subh-i-zūdi hastam! Guft-u-gū bā Māzīyār Mīrī darbārah-yi Sa‛ādat Ābād,” [“I am an Early Riser! A conversation with Māzīyār Mīrī about Felicity Land”], Film Monthly 434 (2011): 15. Translated by Aria Ghoreishi.

The characters in Felicity Land adopt the pose of stable people, when in fact either their living conditions are not as sustainable as they pretend, or they take on ambitious financial endeavors that they cannot afford.

As Felicity Land progresses, our awareness of hidden truths about the relationships between the main characters grows. For instance, Muhsin has imported a significant quantity of goods from overseas, necessitating his borrowing a substantial sum of money from Bahrām (Husayn Yārī). Additionally, Bahrām has loaned this money despite the fact that all of his possessions are actually owned by his wife, Tahmīnah (Hingāmah Ghāzīyānī), and he has no personal savings. Also, ‛Alī (Amīr Āqā’ī) and his wife Lālah (Mahnāz Afshār) have recently moved into a new house, despite already being under financial pressure. Thus, the common point between Muhsin, Bahrām, ‛Alī, and Lālah is the difference between their real economic class and their lifestyle, and this point intensifies the dramatic conflict.

The director and screenwriter of Felicity Land, Māzīyār Mīrī and Amīr A‛rābī respectively, skillfully intertwine financial concerns with moral conflicts by creating subtle backgrounds for the characters. For example, when Lālah and Ali are on their way to the party, Lālah, in a mockery of ‛Alī’s slow driving, tells him, “Don’t go too fast. It is considered Harām,”23Māzīyār Mīrī, dir. Felicity Land [Sa‛ādat Ābād] (Tehran: Humāyūn As‛adīyān, 2011), 00:08:57. (which means it is banned in Islam). Lālah’s joke about the prohibition of speed due to the orders of Islam implicitly refers to ‛Alī’s religious roots. ‛Alī’s appearance and modern lifestyle do not provide a clear understanding of this aspect of his identity. Later we witness ‛Alī’s sometimes harsh and fossilized behavior with Lālah in the middle of the party, and as his restrictive behavior towards his wife is revealed, the recollection of Lālah’s joke in the earlier driving scene subtly signals the conservative roots of ‛Alī’s behavior.

Figure 10: A screenshot from the film Sa‛ādat Ābād (Felicity Land, 2011), directed by Māzīyār Mīrī.

We are also introduced to Muhsin in a similar fashion when he jokes about the prevalence of Chinese goods. Muhsin emphasizes that purchasing Chinese goods is now the only viable option due to their global dominance. He humorously suggests that marrying a Chinese woman, who might not understand your language, could simplify life by removing complexities like dowries. According to him, one of the advantages of Chinese women is that they can be easily replaced. Muhsin’s statements shed light on two issues affecting the emerging middle class. Firstly, there is a blind conformity to external conditions—Muhsin implies that buying Chinese goods is a necessity due to their market dominance. Secondly, there is a tendency towards diversity and evasion of responsibility, as reflected in Muhsin’s comment about Chinese wives.

In the original version of Felicity Land, we discover that Muhsin has been cheating on his wife with their child’s nanny. Muhsin’s earlier comment about the benefits of having a Chinese wife, particularly the notion that she can be easily replaced, serves as a foreshadowing of his later betrayal and underscores the ethical crisis faced by the film’s characters. This conclusion was omitted from the version aired on the home video network. This scene illustrates the moral and financial challenges faced by the aspiring middle classes. We are faced with people whose pretense is significantly different from their true selves.

Consequences of Concealment

Melbourne is another important Iranian apartment drama from the 2010s that portrays an ethical dilemma within the middle class. In contrast to previous examples, the financial issue does not contribute to the progression of the story, as the focus solely lies on an ethical dilemma. The film narrates the story of a couple named Amīr (Payman Muʿādī) and Sara (Nigār Javāhirīyān) who are preparing to travel abroad for a long period. As they are preparing, they agree to take on the responsibility of babysitting one of their neighbors’ infants for a few hours. The crisis begins when the child, for unknown reasons, dies, and Amīr and Sara, with only hours to go before leaving the country, must manage this tragic situation. A significant part of the film revolves around the question of whether to always be honest or whether it is possible to resort to concealment to achieve personal goals.

Figure 11: A screenshot from the film Melbourne (2014), directed by Nīmā Jāvīdī.

It is clear that the concept of concealment is one of the common points that connects many of the Iranian apartment dramas after 2009. However, the creators of each film have employed distinct approaches to the notion of concealment. In A Separation, the two main secretive characters (Nādir and Rāzīyah) ultimately sacrifice their short-term interests for their principles and moral beliefs. In Blind Spot, the main character’s doubt about the possibility of concealment by his wife is depicted as a kind of pathological obsession that puts their lives in crisis. In Felicity Land, the characters’ efforts to conceal their intentions, cognitive processes, and professional actions are unsuccessful and they are caught—making their efforts to conceal seem like a complete failure. However, in Melbourne, the two main characters continue to conceal to a horrific point. At the end of the film, Amīr and Sara decide to go on their important trip abroad under any circumstances, and so they entrust the child (without mentioning it’s death!) to another of their neighbors, so that the burden of the child’s death falls on the shoulders of a person who is entirely unaware of what is happening. However, it is evident that both individuals are internally broken because of the events that have happened and their ruthless decision, and they can no longer go back to being the people they were before the incident (figure 12).

Figure 12: At the conclusion of Melbourne, Amīr and Sara have achieved their initial goal of continuing their migration journey. However, there is no longer any sign of the initial enthusiasm and excitement in them, and their faces have sunk into darkness. Melbourne (2014), Nīmā Jāvīdī, accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M5RW3OQxzDc (01:27:16).

Personal Progression

In addition to common themes, the type of conflict generated can also be considered as a relatively prevalent structural pattern in Iranian apartment dramas after 2009. While it is natural for films set in a single location with limited characters to focus on personal conflict, such as family relationships or friendship, a location-based drama can also be centered on either extra-personal or inner conflict. That dramas centered on a specific location focus on personal conflict is not something limited to the cycle of apartment dramas produced in Iranian cinema after 2009. However, what is noteworthy about this specific cycle of apartment films is the outcome they attain by centering on this type of conflict.

As mentioned earlier, in A Separation, we are faced with the conflicts of two couples. The story of Felicity Land revolves around three couples who gather at one house for a birthday, only to gradually find themselves in disagreement. A similar family pattern is evident in Blind Spot, in which the members of a family gather for a birthday party and a crisis ensues. In Melbourne, a couple is faced with an unexpected crisis on the eve of a journey, leading to the emergence of numerous personal conflicts, both within their relationship and with others.

In such conditions, it is natural for the creators of apartment dramas to pay attention to a technique for advancing the story known as personal progression. This technique is one of the four that Robert McKee mentions when discussing progression in a story.24Robert McKee, Story: Substance, Structure, Style, and the Principles of Screenwriting (New York: Regan Books, 1997), 294-301. The focus on personal progression, which means driving actions deeply into the intimate relationships and inner lives of the characters,25Robert McKee, Story: Substance, Structure, Style, and the Principles of Screenwriting, 295. seems to be both more appropriate and less risky for apartment dramas. In this technique, the screenwriter, realizing that he cannot logically go wide, goes deep. Such a screenplay begins with a personal or inner conflict that seems solvable and gradually moves towards the underlying layers and hidden secrets of the character.

But why is the use of this technique more appropriate than other methods of showing progressive movement for most apartment dramas? The obvious reason is the limitation of space and number of characters. For example, the social progression technique (which means widening the impact of character actions into society)26Robert McKee, Story: Substance, Structure, Style, and the Principles of Screenwriting, 294. requires the gradual introduction of more affected characters, which is not that simple for an apartment drama. Also, the symbolic ascension technique (to build the symbolic charge of the story’s imagery from the particular to the universal, the specific to the archetypal)27Robert McKee, Story: Substance, Structure, Style, and the Principles of Screenwriting, 296. mainly requires the expansion of images (and places) that are also difficult to access in an apartment drama. However, the social and even symbolic aspects of apartment dramas in Iranian cinema during the 2000s and 2010s are often achieved without the need to expand images and locations, as McKee suggests is a requirement for the symbolic ascension technique. This particular feature may be more readily available in films originating from lands of small power.

Figure 13: A screenshot from the film Melbourne (2014), directed by Nīmā Jāvīdī.

Before delving into the analysis of the symbolic aspects of characters in Iranian apartment dramas post-Green Movement, it is essential to consider a significant distinction in the definition of “lands of great power” and “lands of small power.” A great power is a state that possesses the capability to exert its will upon a smaller power. However, this relationship is not reciprocal in the sense that a small power cannot assert its will against a great power.28Christine Ingebritsen, Iver Neumann, Sieglinde Gstöhl, and Jessica Beyer, eds., Small States in International Relations (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2006), 17. The exercise of will extends beyond matters such as deploying military force during times of war; indeed, the cultural impacts of asymmetrical power relations are significant. Events in lands of great power can affect individuals in lands of small power. The likelihood that familiarity with the lifestyle of the inhabitants of great power territories will influence the way of life and thinking of people in small power territories is considerably more pronounced than the reverse scenario. Iraj Karimi discusses the influence of the general conditions of a country in portraying stock characters in cinematic works in a way that can be helpful for understanding the impact of apartment dramas in Iranian cinema. He highlights the challenge faced by the Iranian audience in comprehending and internalizing the notion of individuality, both in daily life and when exposed to dramatic works. Moreover, he notes that even when a filmmaker creates individual characters, they tend to see them as social types and manifestations of a social class or stratum. Karimi attributes this aspect to various factors, with one of them being the general conditions prevailing on the artist and the audience.29Iraj Karimi, “Dark-i Najvā dar Hayāhū-yi Bāgh” [“Understanding the Whispering in the Bustle of the Garden”], Film Monthly 234 (1999): 68-69.

When discussing this reason, Karimi cites a quote from Friedrich Dürrenmatt quoted by George Wellwarth. According to Wellwarth (via Dürrenmatt), all the events that take place in the lands of the great powers (even the everyday lives of citizens) are important to everyone because any event that occurs in those countries automatically affects the rest of the world. However, in other countries, issues such as family life are rarely important to audiences from other countries (and even many audiences from the same country). In such conditions, filmmakers working in the lands of small power are more likely to turn to typical faces (symbolic characters).30Karimi, “Dark-i Najvā dar Hayāhū-yi Bāgh,” 69. With this explanation, it is not surprising that the creators of Iranian apartment dramas showed an interest in creating symbolic characters, and that critics have assessed apartment dramas in this frame. For example, despite Farhādī’s efforts to portray the existing differences among the characters of each economic class in A Separation, Mustafa Jalali-Fakhr, in his article about the film, implies that due to Farhādī’s greater emphasis on the social aspects of the characters, there were limited chances to delve into their inner complexities. From his perspective, in A Separation, the compulsory presence of class conflict, as one of the driving forces in the drama, places individuals within the boundaries of these relationships and social equations. This, in turn, significantly impacts their individuality under the influence of social realism clichés.31Mustafa Jalali-Fakhr, “Dar Just-u-jū-yi Elly” [“In Search of Elly”], Film Monthly 426 (2011): 20.

Similar arguments concerning the symbolic or social dimensions of Melbourne have also been raised. For instance, in his review, Peter Debruge notes that the actions of Amīr and Sara in Melbourne might carry different meanings for foreign audiences compared to Iranian viewers. An Iranian viewer might interpret Amīr and Sara’s behavior through the lens of cultural factors. This audience understands well the significance of migration to Australia for individuals of the middle class. In contrast, for a foreign viewer, Melbourne might appear as another complex thriller where if the characters simply reported the story to the authorities, the resolution could have been much simpler.32Peter Debruge, “Film Review: Melbourne,” Variety, November 18, 2014. https://variety.com/2014/film/festivals/film-review-melbourne-1201358221/ Amin Azimi, referring to Debruge’s explanation, suggests that Sara and Amīr may be regarded as representatives of the middle class in Iran at the time when the film was produced. Considering the importance of the migration issue for individuals in that social group, the Iranian audience, in its ultimate judgment about the characters, views their decision to shirk responsibility in order to preserve their chances of immigration as a fundamental external and socio-economic factor. However, for a Western audience with limited knowledge of the necessity and significance of migration to Australia, this decision will appear more psychologically complex. Nīmā Jāvīdī, the director and screenwriter of Melbourne, acknowledges that although his main objective was to create an engaging story, an Iranian viewer tends to initiate conceptualization and interpretation when faced with a film like Melbourne.33Amin Azimi, “Hamīshah bi Dāstān Īmān Dāshtah-am: Guft-u-gū bā Nīmā Jāvīdī” [“I have Always Believed in the Story: A Conversation with Nima Javidi”], Filmnegar Monthly 146 (2015): 85.

These examples suggest that despite a filmmaker’s efforts to develop unique characters, a segment of Iranian audiences and critics tend to analyze the characters as societal archetypes when they encounter works that reflect the broader concerns of the middle class.

Conclusion

During the first half of the 2010s, a significant number of apartment dramas emerged, depicting economic struggles among middle-class characters, their isolation, aspirations for upward mobility, and the heightened interpersonal conflicts within families and friend groups. Nevertheless, there has been a decline in the production of apartment dramas in recent years. There are multiple factors that can be deemed influential in this regard.

If, as mentioned, the emergence of an audience crisis in Iranian cinema in the late 2000s and the need to reduce the cost of film production are considered to be one of the factors that led to the rise of apartment dramas, the relative economic boom in Iranian cinema in the mid-2010s can also be considered to be effective in reducing the production of apartment dramas. The total number of tickets sold from March 2016 to March 2017 reached over 25 million (nearly three times the ticket sales figure between March 2013 and March 2014).34Zohreh Fathi and Pante’a Khamooshi Esfahani, “Sālnāmah-yi Āmārī-yi Furūsh-i Fīlm va Sīnimā-yi Īrān Sāl-i 1395” [“Statistical Yearbook of Iranian Film and Cinema Sales in 1395”], Iranian Organization of Cinema and Audiovisual Affairs (2018): 2. https://apf.farhang.gov.ir/ershad_content/media/image/2019/12/922299_orig.pdf. Prior to the outbreak of the COVID-19 virus and the subsequent closure of cinemas, the rate of ticket sales consistently remained above 20 million annually. Therefore, filmmakers had the opportunity to come out of the narrow confines of homes and make films with more diverse locations and characters.

The nature of the concerns that were perceptible in society also underwent a gradual transformation. The movement at the end of 2017 and the beginning of 2018 in Iran marked the first major wave of protests after the Green Movement. This movement took place during the month of Dey according to the Persian calendar, which is why it is commonly referred to as the Dey protests. While the primary spectrum of protesters in the Green Movement were middle-class individuals seeking political liberalization, the main social class involved in the Dey protests was the lower class, focusing on economic concerns and demanding social justice.35Ali Fathollah-Nejad, “The Islamic Republic of Iran Four Decades On: The 2017/18 Protests Amid a Triple Crisis,” Brookings, April 27, 2020. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/the-islamic-republic-of-iran-four-decades-on-the-2017-18-protests-amid-a-triple-crisis/. Consequently, starting from the mid-2010s, we are witnessing a shift towards the portrayal of social dramas by focusing on the experiences of the lower economic classes, rather than the concerns of the middle class.

Another factor contributing to the decrease in apartment dramas can be attributed to the gradual decline of the middle class subsequent to 2009. Although the middle class had demonstrated its influence during the Iranian Revolution of 1979—and due to this influence, was always considered a potential threat to the central government—after the rise of the Green Movement the government realized the need to eradicate the middle class.36Muhammed Al-Sulami, “Iran’s Middle Class Marginalized by Regime,” Arab News, July 12, 2021. https://arab.news/8gefb. This organized effort, coupled with the house arrest of Green Movement leaders (Mahdī Karrūbī and Mīr Husayn Mūsavī), led to a surge of disillusionment among some protesters. In addition, the onset of the economic crisis and the sharp fall in the value of the Iranian national currency in 2011 led to the decline of many former members of the middle class to lower-middle-class or even lower-class status during the 2010s. In such conditions, economic concerns gradually gained a more prominent role than non-material and moral concerns in the lives of wider groups of Iranians.

The production of the film Life and a Day (2016)37Sa‛īd Rūstā’ī, dir. Abad va Yik Rūz [Life and a Day], (Tehran: Fīlmīrān, 2016). not only depicted these societal changes but also influenced the trajectory of Iranian cinema. Life and a Day narrated the story of a family from the lower-class involved in a set of crises (unemployment, poverty, addiction, family issues, and forced marriage). The manner in which problems were presented and the socio-economic focus in this film diverged from previous social dramas. The comprehensive success of Life and a Day in Iran, both in terms of critical acclaim and box office revenue, paved the way for the emergence of a new wave of social dramas set in the impoverished areas of the country. As a result, dramas that focused on the middle class became increasingly marginalized.

Nevertheless, apartment dramas, which can be considered to have peaked between 2010 and 2015, hold great significance as a testament to the filmmakers’ perspectives on the class crisis that prominently shaped social transformations in Iran, at least from 1997 through the following two decades.

Cite this article

This article explores the rise of apartment dramas in Iranian cinema following the 2009 Green Movement, analyzing their role in portraying the moral, social, and economic struggles of Iran’s middle class. Films such as A Separation and Melbourne use confined apartment settings as microcosms to reflect personal and societal crises, exploring themes of isolation, class disparity, and moral ambiguity. The article examines the factors contributing to the genre’s decline after the mid-2010s, such as shifts in societal concerns and industry dynamics, while highlighting its cultural significance as a reflection of a turbulent political and social era.