Armenian Architects and the Pahlavī Movie Theater

Introduction1With changes and additions, this essay is a section from my articles, published under the title “Leisure Architecture and the Aesthetics of the Pahlavi ‘Modern Middle Class’,” in Political, Social and Cultural History of Modern Iran: Essays in Honour of Ervand Abrahamian, ed. Houchang Chehabi (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2025), Chapter 15, 378-398.

“In early nineteenth-century Iran, classes existed in the first, but not the second, meaning of the term,” writes Ervand Abrahamian in his seminal Iran Between Two Revolutions.2Ervand Abrahamian, Iran Between Two Revolutions (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1982), 33. By the time of Rizā Shah’s exile and the founding of the Tūdah Party in 1941, Iran’s “modern middle class” not only distinguished itself from the Qājār “traditional middle class” but also managed to create what Abrahamian demarcated, employing Marx, as “a class ‘for itself’ as well as ‘in itself’.”3Ervand Abrahamian, Iran Between Two Revolutions (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1982), 33. Focused on edifices in Tehran, this essay explores the role of architecture in shaping a modern-class discourse in Pahlavī Iran. It argues that the tectonic and stylistic language of modernist architecture in general, focused here on the leisure architecture of movie theaters, was instrumental in shaping the parameters of the collective identity of Abrahamian’s class category: the “salaried middle class” and, to some extent, the “urban working class.” Other processes of modernization, including secular education, the women’s movement, the tourist industry, modern sports, scouting, mass media, and a secularist cosmopolitan ethos of the healthy and fashionable body politics, were embraced by the modern middle class to define its image as a distinct and separate sociocultural class. As scholars of modern Iran have demonstrated, these tropes pivoted on broader global discussions about progress, leisure, health, and hygiene, informed by modernist aesthetic sensibilities.4In addition to works cited and quoted below, see H. E. Chehabi, “Mir Mehdi Varzandeh and the Introduction of Modern Physical Education in Iran,” in Culture and Cultural Politics under Reza Shah, ed. Bianca Devos and Christoph Werner (London: Routledge, 2014), 55-72; H. E. Chehabi, “The Juggernaut of Globalization: Sport and Modernization in Iran,” The International Journal of the History of Sport 19, no. 2-3 (July 2002): 275-294; Sivan Balslev, Iranian Masculinities: Gender and Sexuality in Late Qājār and Early Pahlavī Iran (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019); and Stefan Huebner, “Iran and the Indian Ocean Region Project: The Great Persian Empire, Oil Wealth, and the Seventh Asian Games (1-16 September 1974),” in Pan-Asian Sports and the Emergence of Modern Asia, 1913-1974 (Singapore: NUS Press, 2018), 230-260. As one of the most pervasive and porous among them, Pahlavī architecture was not only integral to the secular systems and strategies that gave birth to the modern middle class “for itself” and “in itself” but also sheltered and shaped its lifestyle; it was the infrastructure upon which that class molded its unique identity. However, when that very lifestyle was contested, its matching architecture of movie theaters came under violent attack.

Adhering to the principles of the canonical architectural style from the 1920s to the 1970s, the International Style and its subsequent offshoots, Pahlavī leisure architecture between the mid-1930s and 1979 was entirely novel in form and function, radically breaking with either the Qājār eclecticism of the nineteenth century or the Persian Revival style of the first three decades of the twentieth century.5See Talinn Grigor, The Persian Revival: The Imperialism of the Copy in Iranian and Parsi Architecture (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2021). In form, its large-scale street elevations with minimal ornamentation, its flat roofs and elongated openings, its receding and projecting oblong blocks, its all-glass transparent public facades, its oversized Latin inscriptions, its obsessive use of concrete, glass, and steel, as well as its exaggerated and asymmetrical volumes enabled new kinds of sociocultural activities and relations. In lived experience, to look and act fashionable meant being modern; and in the case of the 1930s to 1970s Pahlavī modern middle class, this sense of fashionability was primarily grounded in the aesthetics of that experience rather than the upholding of progressive socio-political convictions—at least for those who belonged to the apolitical stratum of Pahlavī society. These disciplinary techniques, through architecture, were intended to maintain the class status quo. Unlike Safavid and Qājār sites and practices of leisure, therefore, the claim of Pahlavī leisure architecture was utopian in form and spirit.6See Rudi Matthee, The Pursuit of Pleasure: Drugs and Stimulants in Iranian History, 1500-1900 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005); and Farshid Emami, “Coffee Houses, Urban Spaces, and the Formation of a Public Sphere in Safavid Isfahan,” Muqarnas 33 (2016): 177-220. Despite its unavailability to many outside urban centers due to economic, geographical, or sociocultural obstacles, it was for “everyone” to aspire to, regardless of income and taste. The king’s discoursed life—and by extension, the king’s discoursed body—was the ultimate model of this aesthetic sensibility, often against the backdrop of modernist architecture.7On the king’s two bodies in European history, see, for instance, Alexandra Ion, “And Then They Were Bodies: Medieval Royalties, from DNA Analysis to a Nation’s Identity,” in Premodern Rulership and Contemporary Political Power: The King’s Body Never Dies, ed. Karolina Mroziewicz and Aleksander Sroczyñski (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2017), 321-352.

Cinematic Pleasure, “Healthy” Leisure

From the outset, the Pahlavī state cultivated a modernist ethos of the healthy national body. The commissions of sporting, scouting, and later on other leisure infrastructure in Tehran benefited from this ideological priority that it conferred on health leisure architectural commissions. Known as Manzariyah, one of these major complexes was officially named the Garden of Scouts and Athletes of the Capital (bāgh-i pīshāhangān va varzishkārān-i pāyitakht).8See Īsā Sadīq, Yādgār-i umr, 4 vols. (Tehran: Dihkhudā, 1959–74), 2:169-70; Pīshāhangī va tarbiyat-i badanī 1 (4 Ābān 1319): 47; and Sayfpūr Fātimī, “Jashn va ‛āmaliyāt-i pīshāhangān dar manzariyah,” Ittilā‘āt (27 August 1935). In 1938, the project of turning several former royal lands into a modernist scouting and sporting complex was commissioned to Roland Dubrulle (1907-83), a young French citizen and a 1931 École des Beaux-Arts graduate who, before departing for Iran, had fallen in love with the Armenian-Iranian student Serpuhi Achik Voskanian.9See Bīzhan Shāfi‘ī, Nāhīd Biryānī, and Nigār Mansūrī, Mi‘mārī-i Rulān Dubrul / Roland Dubrulle: Architecture (Tehran: Rahsipārān, 2021), 13, 34-35, 48-49, 142-43. Their marriage and move to Tehran in August 1935 jump-started Dubrulle’s prolific career. During the same years, four large pieces of land were purchased by the Ministry of Education to serve as sporting grounds for the general public and public schools: Amjadiyah was located “outside Dowlat Gate” in what was then the north of Tehran, while Akbarābād Dūlāb was in eastern Tehran, Bāgh-i Shāh in western Tehran, and the Bāgh-i Firdaws in southern Tehran. Numerically labeled, Amjadiyah, the first and the largest, was named “Sports Complex Number 1.”10See “Amjadieh,” Ittilā‘āt 3352 (7 Day 1316/28 December 1937); “Ā’īn-i gushāyish-i istakhrhā-yi shinā,” Ettelā‘āt (21 Khurdād 1320/11 June 1941): 1; Hekmat, Sī khātarah, 76-77 and 81-82; and Bīzhan Shāfi‘ī, Nāhīd Biryānī, and Nigār Mansūrī, Mi‘mārī-i Rulān Dubrul / Roland Dubrulle: Architecture (Tehran: Rahsipārān, 2021), 50-51, 98-99, and 14856; and Viktor Daniel, Bīzhan Shāfi‘ī, and Suhrāb Surūshiyānī, Mi‘mārī-i Nīkulāy Mārkuf / Nikolai Markov Architecture (Tehran: Dīd Publications, 2004), 96-99.

In tandem with these sport-scouting megaprojects, such as Amjadiyah and Manzariyah complexes, Tehran and other cities began to see the mushrooming of small-scale culinary and recreational sites, intended to support a modern middle-class consumerist lifestyle. While these were a byproduct of the organic growth of the economy, the state forced modern reforms by lowering taxes on such leisure industries as film, while at the same time levying heavy fines on “cinemas, cafés, and hotels, if they discriminated against women.”11Ervand Abrahamian, Iran Between Two Revolutions (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1982), 144. On taxation on cinemas, see Hamid Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema, vol. 2, The Industrializing Years, 1941-1979 (Durham: Duke University Press, 2011), 158. On the architecture of cafés, bars, bowling allies, and to some extent, movie theaters, there was very little or no academic work that I could find. I am grateful to my parents, Moneh and Greg Der Grigorian, for their enormous help and incredible memory to start collecting some information about them. Playing an “extraordinarily significant role in the emancipation of Iranian women” and, thus, the modern middle class, movie theaters, hotel restaurants, delicatessens and diners, cafés, bars, cabarets, and casinos slowly pushed out from urban centers the once-popular tea and coffee houses wherein naqqālī (story-telling) and pardah-khvānī (canvas reading) were popular forms of entertainment and provided a sense of belonging.12Shireen Mahdavi, “Amusements in Qajar Iran,” Iranian Studies 40:4 (2007): 483–99; Hamid Dabashi, Close up: Iranian Cinema, Past, Present, and Future (London: Verso, 2001), 21; and William H. Martin and Sandra Mason, “The Development of Leisure in Iran: The Experience of the Twentieth Century,” Middle Eastern Studies 42:2 (2006): 239-254, at 245-46. Other recreational loci such as the zūrkhānah and takkiyah (structures for the performance of Shiite passion play, ta‘ziyah) were supplanted by these new forms and functions of leisure. Although lacking a modernist architectural character, new public venues such as Café Nādirī (1947, on Nādirī Avenue) and Café Shimīrān (ca. 1950, on Firdawsī Avenue) served Western-style food and deserts, held alcohol licenses, and brought live music bands; many of the early pop signers such as Vigen, Artush, and Wilson debuted here.13Another important site of intellectual and artistic gatherings was Café Firuz (on the southeastern crossing of Nādirī and Qavām al-Saltanah Streets), which was housed in the former stables or auxiliary structures of the Golestan Palace complex, large sections of which were destroyed during Reza Shah’s urban reforms in the late 1920s. The interior consisted of a ceiling of smaller domes with hanging fans, recreating a North African and Moroccan vernacular style, and recalling the images in such Hollywood movies as Casablanca (1942). Café Fīrūz was demolished sometime around 1965 when the wood furniture factory cut fire, and Eiffel Cinema eventually replaced the entire corner block. During the free political period between 1941 and 1963, Café Fīrūz served as the pātuq (hangout) of Sādiq Hidāyat, Nīmā Yūshīj, Manūchihr Shaybānī, Jalāl Āl-i Ahmad, and Jalīl Ziyāpūr. See Ahmad Karimi-Hakkak, “Protest and Perish: A History of the Writers’ Association of Iran,” Iranian Studies 18, no. 2/4 (1985): 193. By the mid-1960s, Tehran boasted a lively and diverse nightlife in Café Chattanooga (1966, owned by Johnny Lucas on Pahlavī Avenue), Café Brazilo (in Hāfiz and Simi intersection), Café Riviera (on Qavām al-Saltanah Street), Café Firdaws (on Istanbul Street), Cabaret Shukūfah Naw (adjacent to the Red District in southern Tehran), Cabaret Copacabana (on Takht-i Jamshīd Avenue), Cabaret Mayāmay [Miami] (on Pahlavī Avenue), Cabaret Ufuq-i Talā’ī (on Lālahzār Street), Café Jamshīd (on Manūchihrī Street) to name a few. In the mid-1960s, the youth of the modern middle class enjoyed outdoor minigolf and indoor bowling. On Old Shimirān Road, the recreational complex of ‛Abduh Bowling (1964) featured an automated bowling hall adjacent to a movie theater and an indoor pool. Owned by the CRC company with ‛Alī ‛Abduh, Commander of Airforce Muhammad Khātamī, and Princess Fātimah Pahlavī as its principal shareholders, it was also the owner of the famous soccer team Persepolis.

However, the movie theater was the most striking coupling of modern middle-class leisure and modernist architectural aesthetics. The modernizing effects of cinema are well established in the history of Pahlavī Iran; in fact, the rich and robust history of Iranian cinema is one of the few visual disciplines that has been accepted into the mainstream of Iranian Studies. However, despite its richness, few authors address the importance of the spaces in which movies were experienced as a form of modernity. In Iranian cities, movie theaters sprung up in abundance during the decades between Rizā Shah’s abdication and Muhammad-Rizā Shah’s exile. Their numbers jumped from fifteen to 122 in Tehran and 432 in other cities by 1973.14See Hamid Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema, vol. 2, The Industrializing Years, 1941-1979 (Durham: Duke University Press, 2011), 158-59; and Shahin Parhami, “Iranian Cinema: Before the Revolution,” in Early Cinema in Asia, ed. Nick Deocampo (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2017), 257. “[M]oviegoing” was the “cheapest form of mass entertainment,” and the halls were packed.15Hamid Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema, vol. 2, The Industrializing Years, 1941-1979 (Durham: Duke University Press, 2011), 159. At the dawn of the anti-Pahlavī revolution in 1977, vis-a-vis a total population of 39.9 million Iranians, 110 million cinema tickets were sold.16“Between 1963 and 1977 … the number of cinema tickets sold rose from 20 million to 110 million.” Ervand Abrahamian, Iran Between Two Revolutions (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1982), 428.

At the start of each film session, the audience rose to the national anthem while watching the moving images of the royals. “Cinematic modernity” was contingent upon the theater because “screening spaces were implicated in a temporality that … propelled into the future.”17Golbarg Rekabtalaei, Iranian Cosmopolitanism: A Cinematic History (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019), 1. Like the stadium and its diving tower, the movie theater was quintessentially modern as a formal typology and, thus, both in the West and in Iran, those architects who identified with the Modern Movement sought out their commissions. Leading architectural journals published floor plans and photographs of new movie theaters designed by pioneering architects globally.18See, for example, the special issues or multiple articles on movie theaters in L’Architecture d’aujourd’hui 7 (September-October 1933): 24-119; L’Architecture d’aujourd’hui 2 (February 1936): 26-27 and 44-45; L’Architecture d’aujourd’hui 7 (July 1937): 38-40; and L’Architecture d’aujourd’hui 9 (September 1938): 2-12 and 51-75. By the end of World War II, when the first International Style theaters were erected by well-known Iranian architects, the modern middle class, “whose members not only held common attitudes toward social, economic, and political modernization” but also held “similar relationships to the mode of production, the means of administration, and the process of modernization,” was ready to consume them as their own.19Ervand Abrahamian, Iran Between Two Revolutions (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1982), 145-146. Movie theaters were conducive to an image of a secular class “for itself” and “in itself.” Moreover, they provided a completely novel physical environment wherein to perform the rituals of bourgeois sociability: dating, consuming, and ceding to the pleasure of narcissism and scopophilia.20See Laura Mulvey, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” in Feminisms Redux: An Anthology of Literary Theory and Criticism, ed. Robyn Warhol-Down and Diane Price Herndl (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2009, first written in 1975), 432-442. Requiring specialized architectural expertise, their tectonic nature enabled modernity’s alluring tensions: public yet informal, classy yet non-elitist, artsy yet accessible, dark yet visible, hi-tech yet familiar, enclosed yet transparent, subversive yet apolitical, globally-connected yet intensely local and intimate. The private clientele enabled the architect to experiment with modernist principles free from the heavy demands of the state; the location and scale of the projects facilitated creativity with large street façades as well as complex interior morphologies.

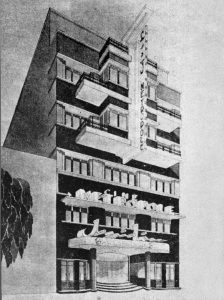

Unlike its socio-cinematic history, scholarship on the architecture of Iranian movie theaters is scarce and patchy. In this brief study, I consider a dozen edifices with available visual evidence to me and erected by known Iranian architects who adhered to the tenets of the Modern Movement and its later offshoots. Many were ethnic Armenians involved in various aspects of Iranian modernism, particularly the movie industry.21On the Armenian role in the Iranian cinema, see Naficy, Social History, 2:54, 153, 170, 239, 253, 320, 334, and 341. For Abrahamian’s discussion of the role of ethnicity in the formation of the modern middle-class see, Ervand Abrahamian, Iran Between Two Revolutions (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1982), 383-415. “Indeed,” as Houchang Chehabi argues, “one of the characteristics of the modern middle class was that it included Baha’is, Christians, Jews, and Zoroastrians, who commingled more easily with their Muslim compatriots,” and they did so in these new modernist spaces.22H. E. Chehabi, “The Rise of the Middle Class in Iran before the Second World War,” in The Global Bourgeoisie: The Rise of the Middle Classes in the Age of Empire, ed. David Motadel, Christof Dejung, and Jürgen Osterhammel (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2019), 43-63, 61. Two of the earliest movie theaters in a sober Art Deco that incorporated the International Style were the work of the most vocal advocate of the Modern Movement in Iran: Armenian-Iranian architect Vardan Hovhannisian (1896-1982), whose prolific career after his 1935 return from Paris helped shape the leisure and tourist infrastructure of the middle class, including Darband (in Darband, 1938), Lāleh (on Lālehzār Street, 1945), and Ferdowsi (on Ferdowsi Avenue, 1949) hotels. In 1942, Hovhannisian was commissioned to design Metropole Cinema on the western side of Lālehzār Street among the range of other early theaters such as Iran (1940), Crystal (1945), and Rex (1945).23On Khachaturian, see Naficy, Social History, 2:169-70. They all shared the eye-catching, vertically tall, narrow street façades, demarcated by an inviting deep central entrance. Metropole’s façade looked like a cubist sculpture with receding and projecting blocks of the top three floors that housed the various production and distribution of films, dubbing, camera repair, and other cinema-related administrative offices. A protruding structure suspended from the third- to fifth-floor balconies carried the letters M E T R O P O L E as an integral part of the avant-garde design (figs. 1-2).

Figure 1: Rendering of Metropole Cinema by Irano-Armenian architect Vardan Hovhannisian, Tehran. Photo: “Paydāyish-i mi‛mārī-i mudirn dar Īrān: Yādnāmah-yi Vārtān Huvānisiyān 1275-1361,” Nashriyah-yi Jāmi‛ah-yi Mushāvirān-i Īrān 1 (Spring 1983): 9.

Figure 2: Façade of Metropole Cinema, designed by Irano-Armenian architect Vardan Hovhannisian, located on Lalahzār Street, Tehran, 1946. Photo with copyright: Talinn Grigor, 1999.

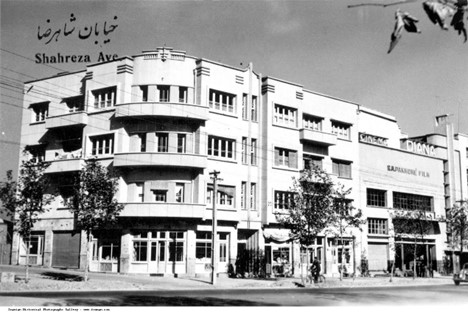

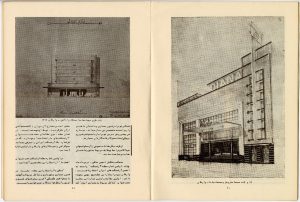

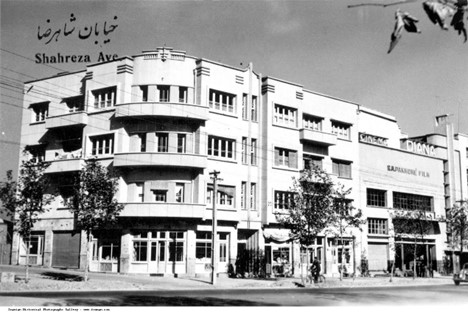

The main theater was accessed through the central doors into a large lobby, ticketing, and concession area with a balconied second floor visible from below. Once inside the hall, the ground floor accommodated 650 spectators on large, padded armchairs, while the mezzanine accommodated 250 spectators. Tehran’s Armenian-language daily, Alik‘, depicted Metropole in 1946 as an expression of “rhythm, modernity, harmony, and simplicity.”24lik‘ (23 November 1946), n/p; quoted in Suhrāb Surūshiyānī, Viktor Daniel and Bīzhan Shāfi‘ī, Mi‘mārī-i Vārtān Huvānisiyān / Vartan Hovanesian Architecture (Tehran: Dīd Publications, 2008), 98, see also 97-101. Four years later, Hovhannisian’s Diana Cinema (1950, owned by a female Armenian producer, Sanasar Khachaturian who also owned Diana Film, figs. 3-4), on Shah Rizā Avenue, wedded middle-class values to the same aesthetic sensibility of deep horizontal lines and openings, the use of bold Latin inscriptions, and a transparent glass wall on the façade.

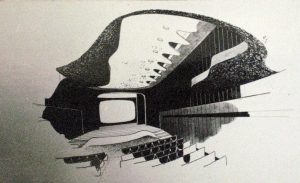

Figure 3: Renderings of Cinema Diana and the Train Station by Irano-Armenian architect Vardan Hovhannisian, Tehran. Photo: “Paydāyish-i mi‛mārī-i mudirn dar Īrān: Yādnāmah-yi Vārtān Huvānisiyān 1275-1361,” Nashriyah-yi Jāmi‛ah-yi Mushāvirān-i Īrān 1 (Spring 1983): 10-11.

Figure 4: A postcard depicting Cinema Diana by Irano-Armenian architect Vardan Hovhannisian adjacent to a modernist residential building on Shāhrizā Avenue, Tehran, ca. 1950s. Photo: Public domain.

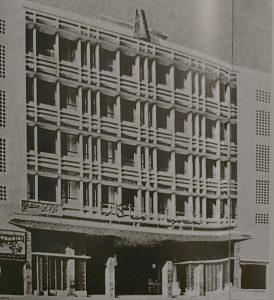

The mid-1950s and the end of the 1960s saw a bourgeoning of modernist theatres that dominated the visual and urban landscape by their sheer size and aesthetics, among them Firdawsī and Universal (on Shah Rizā Avenue, 1963), and Atlantic (on Pahlavī Avenue, 1964). The Iranian brand of the International Style came to its own in 1957 with Armenian-Iranian architect Paul Apcar’s (1909-1970) Niagara Cinema (owned by ‛Alī Hātamī or “Mr. A. Hūmanī” and actor Muhammad ‛Alī Fardīn, inaugurated on 29 April 1958, fig. 5). A massive block on Shah Avenue, its street façade consisted of a lattice structure, crowned cone, assembled of reinforced and exposed concrete, a material Le Corbusier had dubbed béton brute (bare concrete) and which was a quintessential signifier of modernity. Having returned to Iran from Paris and Brussels in 1936, Apcar took inspiration from Le Corbusier’s Chandigarh and from Brasilia in its unapologetic and rationalist use of béton brute, steal, and glass. Described as “one of the most modern cinemas in the capital,” the all-glass entrance wall introduced visual transparency between the sidewalk and the lobby. The floor plan, too, pioneered an innovative scheme, where the trapezoidal theater hall of 950-seat was nested into the outer shell, lodging the auxiliary facilities.25Bīzhan Shāfi‘ī, Suhrāb Surūshiyānī, and Viktor Daniel, Mi‘mārī-i Pul Ābkār (sic) / Paul Apcar Architecture (Tehran: Abyānah, 2015), 36; see also 302-315. The six pairs of doors lined the two long sides of the hall, allowing the smooth and safe circulation of the audience: through the lobby, they came into the hall via the western doors and exited, first into a long corridor onto the main façade (fig. 6). The first to include rocking chairs, the tactile expressiveness of Niagara Cinema conveyed contradicting regularity, harmony, brutality, and pleasure.

Figure 5: Façade of Niagara Cinema by Irano-Armenian architect Paul Apcar, located on Shah Avenue, Tehran, inaugurated on 29 April 1958. Bīzhan Shāfi‘ī, Suhrāb Surūshiyānī, and Viktor Daniel, Mi‘mārī-i Pul Ābkār (sic) / Paul Apcar Architecture (Tehran: Abyānah, 2015), 302-303.

Figure 6: Architectural drawings of the ground and mezzanine level floor plans and section for Niagara Cinema by Irano-Armenian architect Paul Apcar. Photo: Paul Apcar Private Collection in Bīzhan Shāfi‘ī, Suhrāb Surūshiyānī, and Viktor Daniel, Mi‘mārī-i Pul Ābkār (sic) / Paul Apcar Architecture (Tehran: Abyānah, 2015), 306.

Two other Beaux-Arts-educated architects embarked on movie theater design during this time. On the northwestern corner of Shah and Pahlavī avenues, Baha’i-Iranian architect Hūshang Sayhūn’s (1920-2014, returned to Iran in 1949) Asia Cinema (1958) incorporated an uninterrupted glass wall wrapped around that entire corner, rendering the interior visible to passersby.26See Sīrūs Bāvar, Nigāhī bih paydāyī-i mi‘mārī-i naw dar Īrān (Tehran: Fazā, 2009), 111; and Vahīd Qubādiyān, Sabkshināsī va mabānī-i nazarī dar mi‘mārī-i mu‘āsir-i Īrān (Tehran: ‛Ilm-i Mi‘mār, 2013), 238 and 242-243. Raising to five stories, the floor-to-roofline glass facade was supported with a set of loadbearing columns, right behind the glass wall. Structurally and visually novel, Asia Cinema was outdone by Sayhūn’s other contribution to the tourist industry; the network of national mausolea he designed, including Ibn Sīnā (Avicenna) (Hamadan, 1952), Nādir Shah (Mashhad, 1959), the painter Kamāl al-Mulk, and Omar Khayyam (Nishapur, 1962-63). Returning in 1954, Shiite-Iranian architect Haydar Ghiyā’ī (1922-85) designed Moulin Rouge Cinema (on Old Shimīrān Road, one of the five chain theaters owned by the Akhavān Brothers, 1956), Radio City Cinema (on Pahlavī Avenue, 1958), and Tehran Pars Casino and Drive-In Cinema (1960), to complement his icon of streamlined modernity, the Royal Tehran Hilton Hotel (1962).27See Heydar Giai [sic], “Cinéma en plein air à Téhéran,” L’Architecture d’aujourd’hui 93 (December 1960): 20-21. Designed by Shiite-Iranian architects Yūsuf Sharī‘atzādah (1930-2001) and Husayn Mīr Haydar (no dates), Rivoli Cinema (on Old Shimīrān Road, 1962) introduced an updated modernist vocabulary by rejecting the formal rigidity of the International Style and incorporating a massive curvilinear volume on its façade. It has been described as “the first theater where the facade had a direct relation with the interior function.”28Sīrūs Bāvar, Nigāhī bih paydāyī-i mi‘mārī-i naw dar Īrān (Tehran: Fazā, 2009), 132, see also 131-34.

The 1960s closed with the appearance of another massive and striking edifice on Takht-i Jamshīd Avenue: Tabriz-born architect from a Russo-Armenian family, Yougenia Aftandilians’s (1914–1998) Golden City (1039-seat, 1969, fig. 7) successfully pulled the stylistic history of Iranian movie theaters into the second half of the century.29In his private papers, Aftandilians spells his first and last name in various ways in different documents produced in various stages of his career, including “Y.” “Yougenia,” “Aftandilians,” and “Aftandilianz.” In Armenian and Iranian circles, he was known as “Zhenia” or “Genia” (the Russian pronunciation of Eugene) or “Zhenik” (the Armenian version of the Russian Eugene with the added Armenian diminutive “ik”). See the Aftandilians Private Collection of Roubik Aftandilians, Glendale, California. Hovering over an all-glass lobby, a massive, tilted cube rose to mimic the screen of a movie theater as if a semiotic game. The morphology of the edifice was carved so that the building stood like a gigantic sign: I am a movie theater! This solid frame that formed the cube on the northern façade upheld a three-story glass wall that flaunted an innovative truss system, stretched over the lobby, and attached to the mezzanine floor. On its eastern elevation, the structure follows the outline of the spectator’s gaze, starting from the metaphoric glass screen on the northern elevation, through the mezzanine, straight to the actual movie screen in the southern interior elevation. The movie industry’s more playful and daringly experimental modernist aesthetics was restrained and veiled in a Classical architecture language in Aftandilians’ state commissions with the design of the Rūdakī “Opera House” (1967, fig. 8) and the Ministry of Arts and Culture’s amphitheater (1977, fig. 9).30In his resume, it is listed as “Principle Building, Ministry of Art and Culture,” Yougenia Aftandilians, “Personal Resume,” in the Private Collection of Roubik Aftandilians, Glendale, California, undated, 1-2. Still, with the opening of Rūdakī, Aftandilians finally materialized Rizā Shah’s wish for an “Opera House” in Tehran, a scheme first proposed in as early as 1933 (model, fig. 10) by the first representative of the International Style in Iran: Istanbul-born, Tehran-raised, and Vienna-educated Armenian architect Gabriel Guevrekian (1900-1970).31See Talinn Grigor, “Mi‛mārī dar siyāsat va siyāsat dar mi‛mārī: Aqaliyyat-hā-yi mazhabī va bahs-i mi‛mārī-i naw-garā dar Īrān-i qarn-i bīsṭum,” trans. Greg Der Grigorian, the Persian-language Payman: Cultural Quarterly Magazine 79 (Fall 2017): 18-53; and keynote at the Fifth Biennial Conference of the Historians of Islamic Art Association, the Courtauld Institute of Art, University of London, London under the title “Modernism as (a)Politics: Religious Minorities and Discourse on Architecture in Pahlavī Iran” on October 22, 2016; on YouTube at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CpsXGqCMdhA.

Figure 7: Golden City Cinema by Irano-Armenian architect Yougenia Aftandilians, located on Takht-i Jamshīd Avenue, Tehran, 1969. Photo: Mahmūd Pākzād, in Old Tehran: Photography by Mahmūd Pākzād (1941-1975) (Tehran: Dīd Publications, 2003), 314.

Figure 8: Rendering of the Ministry of Arts and Culture’s amphitheater by Irano-Armenian architect Yougenia Aftandilians, Tehran, 1977. Photo with copyright: Private collection and courtesy of Grigor Nazarian. Reproduced with permission.

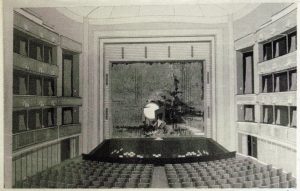

Figure 9: Rendering of the stage of Rūdakī Concert Hall by Irano-Armenian architect Yougenia Aftandilians, Tehran, 1967. Photo with copyright: Private collection and courtesy of Grigor Nazarian. Reproduced with permission.

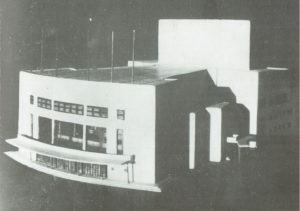

Figure 10: Model proposal for a state theater or an “Opera House,” by Armenian architect Gabriel Guevrekian, unrealized, 1933. Photo credit: Elizabeth Vitou, Dominique Des Houliers, and Hubert Janneau, Gabriel Guévrékian: Une autre architecture moderne (Paris: Connivences, 1987), 97.

Perhaps encouraged by the success of the leisure industry, particularly the cinema, or perhaps to bolster the bread and circus strategy, the government authorized in the 1960s, the launching of a series of recreational hubs (in effect, billiard rooms) for teens, called the Club of Healthy Leisure (bāshgāh-i tafrīhāt-i sālim). While these centers turned out to be a disaster as they contributed to the increase in teen gambling addiction and drug abuse, the campaign of visual hygiene burgeoned. Muhammad-Rizā Shah and Empress Farah Pahlavī continued to embody the image of a nation that was already modernized. Western and Iranian official publications, as well as tabloids like Life Magazine, continued to disseminate photographs of the royal couple engaging in various sporting and leisure activities, including skiing, waterskiing, horseback riding, and riding a Harley. While casually standing in the perfect posture of ski aesthetics and no longer needing the support of architecture, their healthy, fit, and beautiful bodies depicted the fulfilled project of modernity. As a telling sign, when “the massive dams … proudly named after his relatives” broke in 1978, the Pahlavī leisure architecture was the first target of revolutionary iconoclasm.32Ervand Abrahamian, Iran Between Two Revolutions (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1982), 496.

Elsewhere I have argued that the Iranian Revolution of 1977-79 is considered one of the mildest in terms of widespread people-inflicted violence towards architecture and cultural heritage among the major political revolutions of the modern era, including in particular the French and the Russian revolutions, notorious for vandalism and destruction of royal and church property.33See Talinn Grigor, Building Iran: Modernism, Architecture, and National Heritage under the Pahlavi Monarchs. (New York: Periscope, 2009), Epilogue, 202-222; and Talinn Grigor, “The Thing We Love(d): Little Girls, Inanimate Objects, and the Violence of a System,” in The Destruction of Cultural Heritage in the Middle East: From Napoleon to ISIS, The Aggregate Architectural History Collaborative, eds. Nasser Rabbat and Pamela Karimi (Cambridge: MIT, 2016), https://we-aggregate.org/piece/the-thing-we-loved-little-girls-inanimate-objects-and-the-violence-of-a-system. The statues of Pahlavī royalties, along with movie theaters, were an exception. Many cinemas were attacked and burned down—most prominently, Ābādān’s Cinema Rex was set ablaze by Islamist extremists on August 19, 1978, trapping 377 moviegoers in an inferno. Like Pahlavī cinema architecture, the king’s body, which had stood as the symbol of the nation’s health, had also been under attack since 1973 when he was diagnosed with cancer. After the revolution, these sites of middle-class cosmopolitan lifestyle were themselves supplanted by new modalities of class ethics and their corresponding aesthetics. During the decades between the Iran-Iran War (1980-88), the Cultural Revolution (1982-84), and today, Iran has also lost not only ninety percent of its Armenian population but also, with some exceptions including outstanding monographs on Guevrekian, Hovhannisian, and Apcar, the history of their significant contributions to Iranian modern architecture and the Iranian modernization process. This “minor” history is important because, unlike its rivals with significant Armenian populations, the Ottoman and Romanov empires, the Iranian ruling dynasties since the Safavids have recognized the importance of their religious minority communities in their imperial structures, in great part, due to the long and rich tradition of Persianate cultural erudition.34My current book projects, entitled The Hyphenated Architect, aims to recover the lost history of the contribution of Iran’s religious minorities, particularly Armenians, to Iranian cultural modernism. In this book as well as my recent coauthored book, we make this same argument. See Houri Berberian and Talinn Grigor, The Armenian Woman, Minoritarian Agency, and the Making of Iranian Modernity, 1860–1979 (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2025).

Cite this article

Focused on the leisure architecture of movie theaters in Tehran, this essay explores the role of architecture in shaping a modern-class discourse in Pahlavī Iran. It argues that the tectonic and stylistic language of modernist architecture was instrumental in shaping the parameters of the collective identity of Ervand Abrahamian’s class category of the “salaried middle class” and the “urban working” classes. Movie theaters, many of which were designed by Irano-Armenian architects, played a crucial role in shaping the secular, cosmopolitan ethos of healthy and fashionable body politics, thereby defining a middle-class image as a distinct and separate sociocultural class.