Behrouz Vossoughi: The Cult Star of Failed Rebellious Masculinity

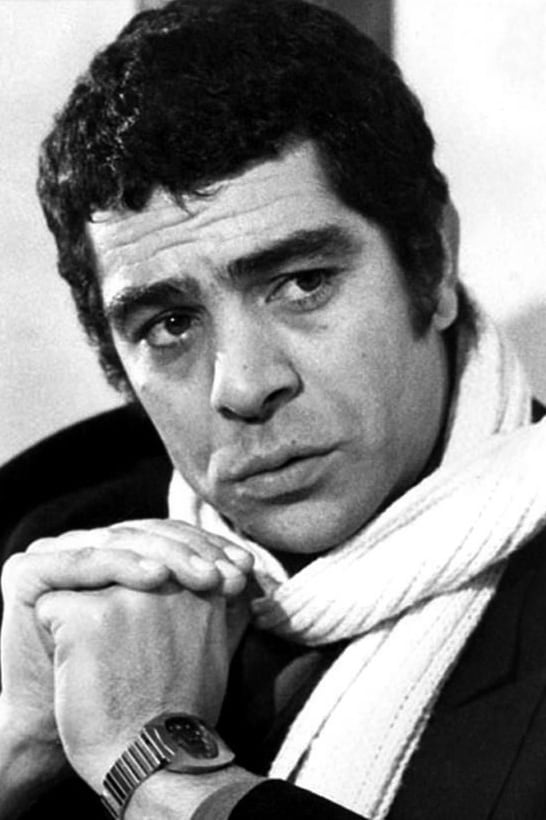

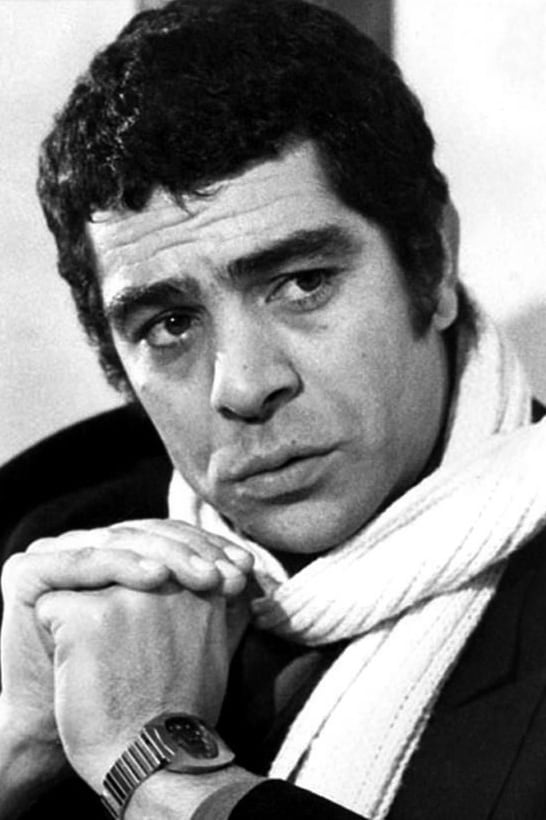

Figure 1: Bihrūz Vusūqī, A screenshot from the film Dashnah (The Dagger).

Introduction

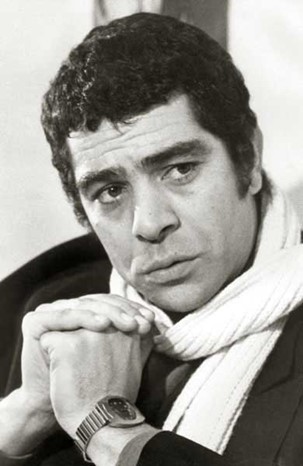

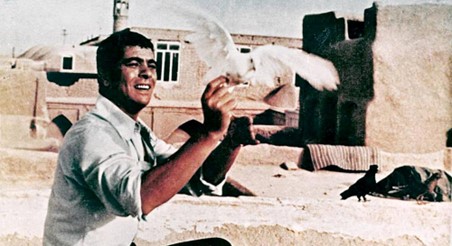

Né Khalīl Vusūqī on March 11, 1938, in the city of Khuy, Bihrūz Vusūqī made his entry into the Iranian film industry as a dub actor for foreign films.1Note on translations and dates: The translation of all Iranian movie titles, publications, expressions, institutions, quotations, and dialogue lines from Persian (Farsi) into English are mine unless suggested by their copyright owners. For converting the dates of events, movie productions, and publications from the Iranian Solar to the Gregorian calendar, I have used Taghvim.com. See “Tabdīl-i tārīkh [Iranian Date Converter],” taghvim.com, accessed July 9, 2024, http://www.taghvim.com/converter/. By the age of twenty-four, he had begun acting in films as well. Between the time of his first major cinematic role in Sad kīlū dāmād (One Hundred Kilos of a Groom, ‛Abbās Shabāvīz, 1961) and his breakthrough performance in Qaysar (Mas‛ūd Kīmīyā’ī, 1969), he had starred in a total of twenty-three other films. Though he had already become one of the most sought-after stars of mainstream cinema, Qaysar made him into a superstar whose fans would watch each of his films religiously and repeatedly for years to come. Over the next ten years, Vusūqī acted in thirty other films. These included some of the most frequently quoted movies from before the Revolution, including Rizā muturī (Reza the Motorcyclist, Mas‛ūd Kīmīyā’ī, 1970), Tawqī (The Ring-Necked Pigeon, ‛Alī Hātamī, 1970), Dāsh Ākul (Mas‛ūd Kīmīyā’ī, 1971), Tangsīr (The Man from Tangistān County, Amīr Nādirī, 1973), Gāvazn-hā (The Deer, Mas‛ūd Kīmīyā’ī, 1974), Ham-safar (Co-Traveler, Mas‛ūd Asadullāhī, 1975), Kandū (Beehive, Farīdūn Gulah, 1975), Malakūt (The Heavenly Kingdom, Khusraw Harītāsh, 1976), and Sūtahdilān (The Heartbroken, ‛Alī Hātamī, 1978), among others. Each of these films enjoys its own fandom, but they are all connected through the strong presence and undiminished reputation of their main actor, Bihrūz Vusūqī, an Iranian cult star par

excellence.

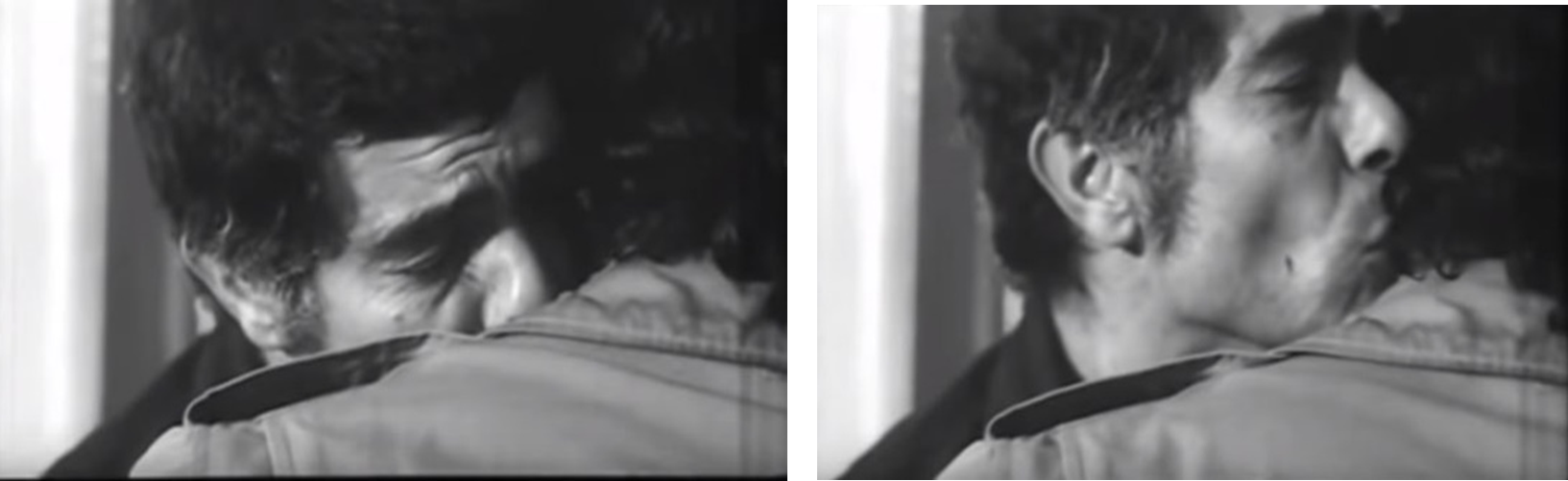

Figure 2: Left: A behind-the-scenes image from the film Ham-Safar (Co-Traveler), directed by Mas‘ūd Asadullāhī (1975). Right: A screenshot from the film Rizā muturī (Reza the Motorcyclist), directed by Mas‛ūd Kīmīyā’ī, (1970)

Cult movie stars are film actors who attract devoted and faithful fans over a long span of time. Cult fans’ passion for engagement with their object of fandom is enduring, interpretive, and productive, and serves the same social, cultural, and political functions as cult movies do. In Cult Cinema, Ernest Mathijs and Jamie Sexton argue that film stardom emerges from a dialogue between the audience’s expectations of the actor based on their chosen on-screen roles, and the actor’s private, off-screen life as publicly observed.2Ernest Mathijs and Jamie Sexton, Cult Cinema (Wiley-Blackwell, Malden, MA: 2011), 76. Moreover, cult reputation may be achieved through a number of different factors, including the longevity of the star’s status, the uniqueness of the movies’ cinematic style or of the star’s method of acting, their reported or rumored unhappiness, a scandal, or a sudden decline or ending of the star’s career, especially due to an untimely death.3Mathijs and Sexton, Cult Cinema, 77-79. In The Routledge Companion to Cult Cinema, Mathijs and Sexton re-iterate the idea that “shortened, abrupt, and fractured trajectories help form cult reputations,” which in turn inspires fans and academics to further inspect the origins of these unusual outcomes in the actor’s performance.4Ernest Mathijs and Jamie Sexton, “Actors,” in The Routledge Companion to Cult Cinema (New York: Routledge: 2020), 432.

We can recognize many of these elements in the life and works of Bihrūz Vusūqī. After more than fifty iconic performances in Iranian films, Bihrūz Vusūqī’s career was cut short due to his permanent departure to the US shortly before the 1979 Revolution. From then on, all of Vusūqī’s pre-revolutionary films have been banned from official distribution in Iran, as are the handful of movies in which he has acted abroad. Despite these circumstances, his fandom has yet to subside. Ask any Iranian, and they will refer you to somebody who can deliver one of Bihrūz’s angry monologues in Qaysar, imitate one of his facial gestures in The Ring-Necked Pigeon, or recite one of his funny quips in Co-Traveler. Even though many fans understood that the oft-quoted “Bihrūz’ lines” were written by different screenwriters and sometimes vocalized by dub actors, they still show their love for the manner in which “Bihrūz” delivered those lines and made them meaningful.5Many of his fans refer to Vusūqī by his first name. Others shorten his last name from Vusūqī to Vusūq—hence, Bihrūz Vusūq. In this article, I mainly use the last name Vusūqī when discussing him. Bihrūz Vusūqī’s adoration by his fans over the past five decades is reminiscent of Kate Egan and Sarah Thomas’s notion that divergent interpretations of “authenticity” act as the main boundary between (regular) stardom and cult stardom: stars convey authentic ordinariness while cult stars lead us to the realm of the extraordinary.6Egan and Thomas argue that while stardom’s authenticity usually conveys ordinariness and naturalness, cult film stardom’s authenticity incorporates “the ironic, the overtly performed, an explicit articulation of labor, the absence of traditional signifiers of emotion or intimacy, the playful juxtaposition between ‘fact’ and ‘fiction,’ the highly controlled, managed, or mediated, and the extraordinary.” See Kate Egan and Sarah Thomas, “Introduction,” in Cult Film Stardom (New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2013), 8. Bihrūz Vusūqī presented the ordinary in an extraordinary way. Thus, he was, and has remained, an authentic cult star in the eyes of his fans.

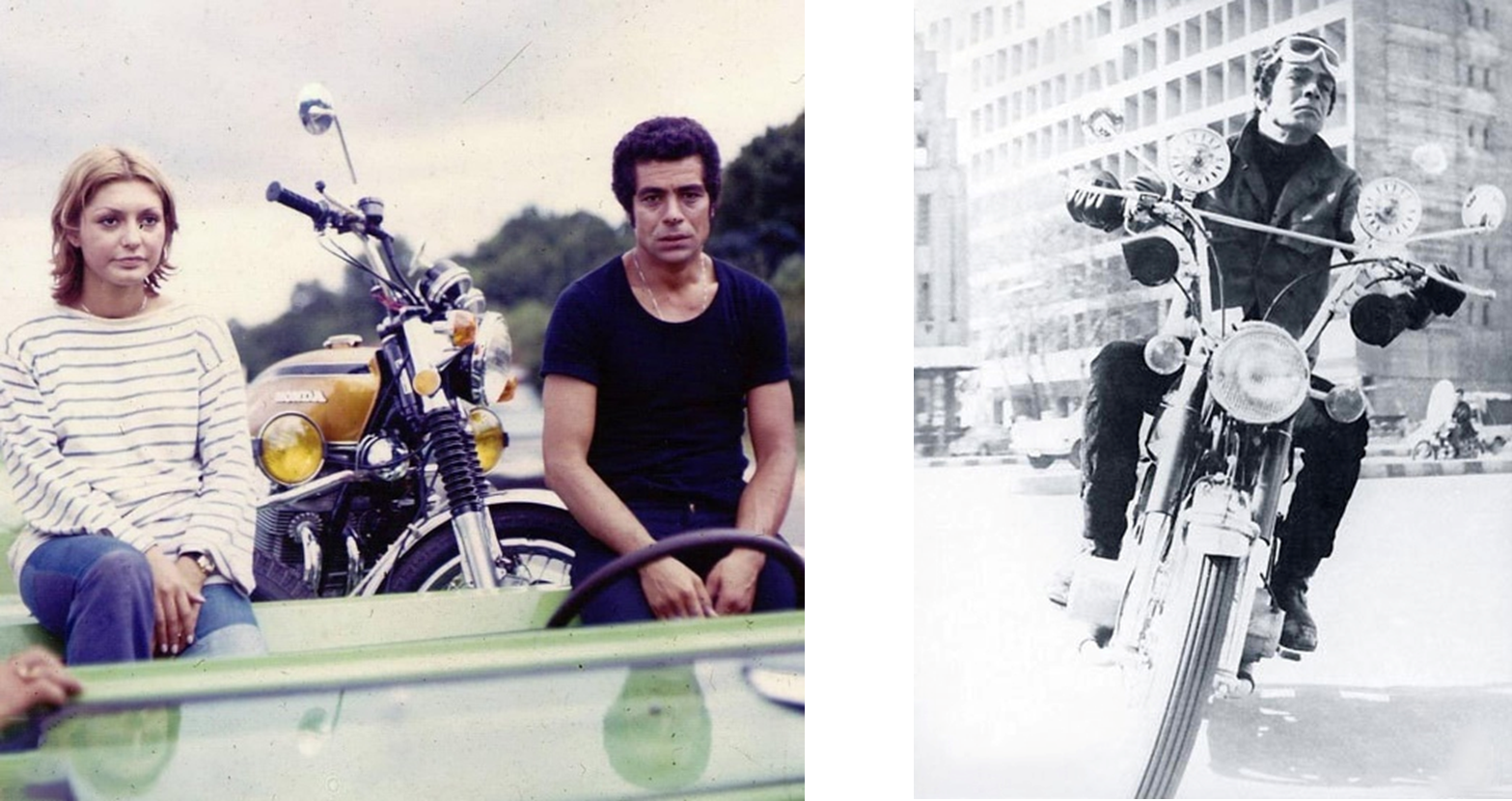

Figure 3: A screenshot from a fan-colored version of the film Tawqī (The Ring-Necked Pigeon), directed by ‛Alī Hātamī, (1970)

In this article, I argue that Bihrūz Vusūqī’s cult star status stems from his authentic representation of the failure of both traditional and transitional modes of masculinity in Iranian cinema and culture. This argument requires a contextualization of Iranian cinema at the time of Vusūqī’s active career. I begin by introducing cinematically mediated modes of hegemonic masculinities as a productive framework for studying Iranian pre-revolutionary commercial cinema, collectively known as fīlmfārsī. Then, I analyze the major elements of Bihrūz Vusūqī’s persona and performance in order to reveal how he was perceived to be a symbol of rebellion against not only other modes of masculinity but also his own rendition of it.7I limit this study to an investigation of Vusūqī’s representation of transitional masculinity through a close reading of his on-screen performance and performance style in several cult movies. However, Janet Staiger’s quadruple consideration for studying star “images” may offer an excellent strategy for advancing this argument further. These include, “(1) the star persona (which may or may not be like the ‘real’ person but which is the intertextually constructed notion of the star through a series of films or television programs and which is known, perhaps, only through watching fictional texts); (2) the star as performer (acting ability or how a star plays the roles he or she is assigned); (3) the star as worker/laborer (the professional life of the individual or how she or he negotiates work situations); and (4) the star in the domestic, private sphere (the so-called off-camera life).” See Janet Staiger, Media Reception Studies (New York: New York University Press, 2005), 116. Emphases are in the original.

As such, he became a symbol of resistance to the abstract concept of patriarchal authority in general. Tracing the discussions of Vusūqī’s stardom before and after the Revolution by focusing on both his publicized off-screen life and the Iranian cultural policies since 1979 can further reveal that Vusūqī has remained a cult star not only because of his curtailed career in Iranian cinema but also because he embodied the culture of rebelling against societal norms without offering a viable alternative, a culture that remains very much alive in the country today.

Masculinity

As the governing style of national film production, fīlmfārsī developed its own aesthetic patterns for survival in its economic battle with foreign imports. One of the most effective strategies of fīlmfārsī involved using male stars who simultaneously represented similar and different conceptualizations of manhood by enacting several modes of differing hegemonic masculinity. R. W. Connell introduces hegemonic masculinity as a culturally honored form of manhood that embodies the norms that a culture idealizes. While hegemonic masculinity is not normal—as few men might be able to enact it—it is certainly normative: it dictates the standards of being a man in society and regulates the power, production, and emotional relations among men and between men and women.8If there is some correspondence between this form of culturally exalted manhood and institutional power, this form of masculinity becomes more likely to be established. Hegemony, in this sense, refers to “ascendancy achieved through culture, institutions, and persuasion.” See R. W. Connell and James W. Messerschmidt, “Hegemonic Masculinity: Rethinking the Concept,” Gender and Society 19, no. 6 (December 2005): 832. Connell states that some of the most visible characteristics of hegemonic masculinity are represented and reinscribed by film stars and their on-screen personas: “They may be exemplars, such as film actors, or even fantasy figures, such as film characters.”9R. W. Connell, Masculinities (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2nd edition: 2005), 77.

The overall hegemonic masculinity represented in fīlmfārsī was what many Iranian critics labeled lumpan (lumpen): a politically charged umbrella term for lower-class urban tough guys abundant in fīlmfārsī.10Originating in the Marxist concept of lumpenproletariat, lumpan was a pejorative title by which intellectuals of the era addressed the dramatic configurations of the jāhil (literally: ignorant) archetype of the era’s urban hoodlums. Lumpans did exist in the margins of society, but it was their dramatization that surfaced and emphasized their rather marginal presence. To read more about different characteristics of lumpans in Iranian society and cinema, see Ali Akbar Akbarī, Lumpanism [Lumpenism] (Tehran: Markaz-i Nashr-i Sipihr, 1973), 147-149; Shahin Gerami, “Islamist Masculinity and Muslim Masculinities,” in Handbook of Studies on Men and Masculinities, eds. Michael S. Kimmel, Jeff Hearn, and R. W. Connell (London: Sage, 2005), 451-452; Farīdūn Jayrānī, “Dahah-yi chihil: Ru’yā-yi shīrīn va shikast [The 1960s: A Sweet Dream and Its Failure],” in Tārīkh-i tahlīlī-i sad sāl sīnimā-yi Īrān [Analytical History of A Hundred Years of Iranian Cinema], ed. ‛Abbās Bahārlū, 79-124 (Tehran: Daftar-i Pazhūhish-hā-yi Farhangī, 2000), 91-103; and, Parviz Jahed, “Lumpanism dar Fīlmfārsī [Lumpenism in fīlmfārsī],” radiozamenh.com, last modified January 29, 2013, https://www.radiozamaneh.com/53023. As a hybrid construct of social and dramatic forces, the lumpan was as much an outcome of several sociocultural processes in Iranian society as it was a result of dramatization in cinema, literature, and theater. The fīlmfārsī of the 1960s and 1970s introduced lumpans as normative: men who were almost unanimously traditionalists, intrepid, tough, sons-of-the-moment, faithful to friendship, and self-assigned and society-assigned protectors of men’s honor in its most patriarchal sense.11For more, see Jamāl Umīd, Tārīkh-i sīnīmā-yi Īrān, jild-i avval: 1279-1357 [History of Iranian Cinema, Volume One: 1900-1978] (Tehran: Rawzanah, 1995), 307; Hamid Dabashi, Close Up: Iranian Cinema, Past, Present and Future (London: Verso, 2001), 26; and, Hamid Reza Sadr, Iranian Cinema: A Political History (London: I. B. Tauris, 2006), 110-112.

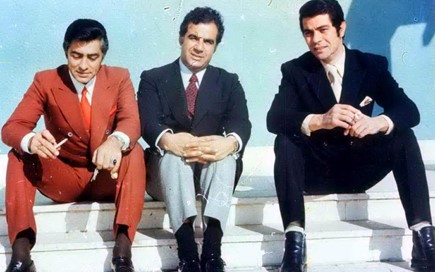

Figure 4: From left: Muhammad ‛Alī Fardīn, Nāsir Malak Mutī‛ī, and Bihrūz Vusūqī

However, the configuration of the fīlmfārsī lumpan shows the co-existence of several overlapping, but still distinct, modalities. Arguably, instead of an unmindful genesis of generic categories, the variety of the hegemonic masculinities represented by Iranian movie stars of the 1960s and 1970s determined the diversification of fīlmfārsī. Benefitting from the advantage of news items about the reception of fīlmfārsī products in pre-revolutionary trade presses as well as the accessibility of many of these films on YouTube in recent years, it is possible to classify the hegemonic representations of masculinity in fīlmfārsī into four categories, each of which can be symbolized by specific stars: the happy-go-lucky fatalist (represented especially by Muhammad ‛Alī Fardīn); the comical action hero (embodied mostly by Rizā Bayk Īmānvirdī); the chivalrous lūtī (represented, first and foremost, by Nāsir Malak Mutī‛ī); and the rebellious young man (whose face was Bihrūz Vusūqī).12Although Hamid Naficy explains the lūtī type in the two forms of the rural dāsh mashtī and the urban jāhil, the critics of the 1960s and the 1970s did not differentiate between different representations of this type, and interchangeably called the character lūtī, lāt, kulāh-makhmalī (velvet-hat), dāsh mashtī, or jāhil. See Hamid Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema, Volume 2: The Industrializing Years: 1941-1978 (Durham, Duke University Press, 2011), 270. Together, these four types and their representative actors were the main forces behind the production of hundreds of films in a little over two decades before the Revolution. And yet, as the following analysis of Bihrūz Vusūqī’s persona and performance shows, his model of masculinity signaled a departure from the previously established norms of on-screen masculinity from the lūtī to an anti-hero (e.g., Qaysar and The Ring-Necked Pigeon), from the happy-go-lucky to a tortured soul (e.g., Reza the Motorcyclist and Co-Traveler), and from the funny action hero to a pathetic loser (e.g., The Deer and Beehive).

The most salient trait of Vusūqī’s persona and performance in personifying this transition was the sense of rebellion that he conveyed to his audience: a rebellion against not only the other forms of manhood, but also different embodiments of patriarchal traditions, authority, and power. Vusūqī’s rebellions can be studied best through his representations of sexuality, the body, and violence. Each of these three attributes contributes to Vusūqī’s embodiment of the failure of manhood, and thus, to the cultification of his image in Iranian cinema.

Figure 5: Left: A screenshot from the film Qaysar, directed by Mas‛ūd Kīmīyā’ī, (1969)

Sexuality

Sexual tensions were among the most recurrent struggles of Vusūqī’s characters. These tensions made themselves evident in three forms: implied impotency, queer-like behavior, and heterosexual temptations—and they began from his very first film. In the comedic One Hundred Kilos of a Groom, Vusūqī played the role of a young engineer pressed with financial hardship. We first see him in a conjugal fight with his wife whom he has already divorced and remarried twice. He threatens to divorce the wife again, which would be an almost unreturnable decision according to Islamic laws.13According to Shi’i jurisprudence, if a man and wife are divorced from each other three times, they cannot remarry unless the woman marries another person, and that person dies or divorces her. This person is called muhallil (the person who makes the ex-wife halal to the ex-husband). Other than this film, the most famous Iranian film which plays with this notion is Muhallil (Interim Husband, Nusrat Karīmī, 1971). The wife, however, teases him by saying “tu aslan mard nīstī! (You are not a man at all!).”14Sad kīlū dāmād (One Hundred Kilos of a Groom), directed by ‛Abbās Shabāvīz (1961; Iran, Tehran, ‛Asr-i Talā’ī, DVD), 00:19:17-00:19:19, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hVTgyno4FcQ Obviously charged with sexual intonations, this line also refers to the common knowledge in Iranian culture that only true men are brave enough to take drastic actions such as permanently divorcing their wives.15In this case, Vusūqī’s character divorces the wife for the third time and then, to be able to remarry her, they find an overweight muhallil; hence the title of the film.

The accusation or implication of impotency or the man’s reluctance to engage in sexual activities with a woman remained with Bihrūz Vusūqī’s characters for a long time. While obviously obsessed with the idea of sex in many of his films, Vusūqī’s characters seem to be constantly fighting their own desires. These internal battles sometimes drove his characters to abstinence, escapism, or different forms of sexual resistance or aberrant behavior. The examples are abundant. In Qaysar, seemingly because of his decision to take revenge for the deaths of his sister and brother, he nullifies his engagement with his fiancée; in Panjarah (The Window, Jalāl Muqaddam, 1969), his girlfriend is pregnant by another man without his knowledge; in Reza the Motorcyclist, the fiancée of Vusūqī’s first character tells him that he is a “khurūs-i bī-buttah (a rooster without balls)”16Rizā muturī (Reza the Motorcyclist), directed by Mas‛ūd Kīmīyā’ī (1970; Iran, Tehran, Payām Cinematic Organization, DVD), 00: 25:011-00: 25:012, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jgMisAgPOoo and that, instead of being called a man, they should call him a chicken with glasses; in Beehive, he seems to suffer from premature ejaculation during his first round of sex with a prostitute and then does not have the money to buy a token for a second round; in Dāsh Ākul, he cannot express his love for a girl because of his promise to her father; and in The Deer, he is totally consumed by his addiction to heroin, and thus, his relationship with his partner has become completely asexual.

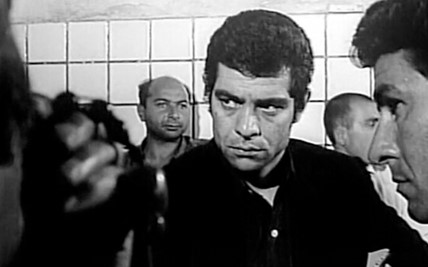

These appearances of sexual shortcomings are sometimes underlined by a variety of male-male relationships with queer undertones or, at least, emphasized bromance. In The Deer, for example, the moment that Vusūqī’s heroin-addicted character meets his friend from high school after several years is punctuated with an exaggerated performance of hugging, smelling, and kissing each other (see Figure 1). An extended queer reading of these moments is beyond the scope of this article. What has been said thus far, however, may suffice to conclude that Vusūqī’s characters seem to be much more at ease during their moments of male bonding compared to their difficult moments of expressing heterosexual connections.

Figure 6. The moment when Sayyid (Bihrūz Vusūqī) and Qudrat (Farāmarz Qarībīyān) meet each other after years of separation. Two enlarged screenshots from Gāvazn-hā (The Deer), directed by Mas‛ūd Kīmīyā’ī (1974; Iran, Tehran, Mīsāqīyah Studio, DVD). Accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q9H_C7NN-EE (00:10:04).

More explicit than the implications of impotency and a proclivity for all-male relationships are the plotlines, sequences, scenes, and shots that represent one of the main dilemmas of Vusūqī’s characters: sexual temptations. These cases clearly point to his struggles with normative masculinities by putting his characters in no-win situations. His resistance against sex equals the failure of the dominant, patriarchal, and sexually active traditional man—he cannot readily act upon his sexual desire. On the other hand, his submission to these temptations implies the failure of the kind of rebellious masculinity that he represents—he fails in resistance. Consequently, his reactions to sex represent both the failure of the traditional man and his alternative.

This situation can be seen in several of Vusūqī-Gūgūsh co-starred movies such as Co-Traveler, in which the plot revolves around his character’s refusal of romantic or sexual engagements with the girl until the turning point of yielding to the temptation.17Fā’iqah Ātashīn (born in 1950), professionally known as Gūgūsh, is arguably one of the most well-known singers, performers, and pre-revolutionary actresses of Iranian cinema. She was briefly, and controversially, married to Vusūqī for fourteen months between 1976 and 1977. One of the best examples of these temptations can be seen in The Ring-Necked Pigeon. In this film, Vusūqī plays the role of a colombophile, Ā-sayd-Murtizā, who is tasked by his lūtī uncle, played by Malak Mutī‛ī, to travel to the city of Shiraz and bring the uncle’s fiancée to their hometown of Kashan. Once in Shiraz, he is struck by her beauty and lasciviousness. Two sequences, in particular, are dedicated to Ā-sayd-Murtizā’s inner struggle to avoid sex with the young woman. The first sleepless night at the fiancée’s house, we see images of her from Ā-sayd-Murtizā’s subjective point of view, followed by a semi-dream shot of her going into a big pool in the yard. Whether in reality or his dream, Vusūqī’s semi-naked character follows her into the pool. He approaches her, but at the last moment, he places his hand on his face—a signature gesture of Vusūqī—and turns his body around (see Figure 2). While this scene has a realistic logic neither in the characterizations nor the plotline of the film, its metaphorical strength is reinforced by the same kind of ambivalent sexuality that the audience expects from Vusūqī’s persona.

Figure 7. Sexual temptation in Tawqī (The Ring-Necked Pigeon), directed by ‛Alī Hātamī (1970; Iran, Tehran, Sierra Film, DVD). Accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Uqu4HIgUpmg (00:21:34).

The next morning, the young man is awakened by the music of diegetic noises: a worker is repairing cotton-field mattresses in the yard by using a traditional cotton-beating instrument that has a rhythmic and musical sound. The girl’s mother is sewing, and the sound of her sewing machine adds to the musicality of the soundtrack. The young man is sweaty and already agitated when the young woman’s vocal improvisation complements the sexual music of the scene. She is doing her makeup in front of a mirror and simultaneously utters meaningless sounds in accompaniment with the seemingly natural music of the ambiance. Either in reality or the young man’s mind, the girl’s voice becomes more and more like sexual moans. The intercut between the image of the girl and Ā-seyd-Morteza’s tossing and turning in bed against the acoustic backdrop of the sex music finally overpowers him. He rushes outside his room while shouting “Oh, God!” Yet, he finally acquiesces and sleeps with her (see Figure 3).

Figure 8. A typical surrender of Vusūqī’s character to his sexual temptations, depicted through five images of the “vocal sex scene” in Tawqī (The Ring-Necked Pigeon), directed by ‛Alī Hātamī (1970; Iran, Tehran, Sierra Film, DVD). Accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Uqu4HIgUpmg (from top and left to right: 00:21:55, 00:22:08, 00:22:26, 00:23:22, 00:18:15).

The Body

Like the ambivalence toward normative sexuality in Bihrūz Vusūqī’s persona, his bodily performance also implies a departure from the hegemonic masculinities of his time. In Masculinity and Film Performance, Donna Peberdy frames gender as an act with a performative nature. The body of the actor, then, becomes not only the means of performing gender but also “an ideological site of naturalized knowledge.”18Donna Peberdy, Masculinity and Fiction (New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2011), 27. This ideological site, however, can perform functions other than conforming with and corroborating the status quo. Russell Meuf and Raphael Raphael, for example, argue that stars’ bodies can also become sites of ideological contestation.19Russell Meeuf and Raphael Raphael, “Introduction,” in Transnational Stardom: International Celebrity in Film and Popular Culture (New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2013), 2. These two functions of stars, especially with regards to their bodies, can be studied in the context of male stardom in fīlmfārsī. If the sportsmanly bodies of sexually active and uncompromising characters of stars such as Malak Mutī‛ī, Bayk, and Fardīn reproduced those conceptualizations of hegemonic masculinity that had become cinematically and culturally exalted in Iranian society, Bihrūz Vusūqī’s body presented an intermediary star who was someplace between traditional heroes and quite average men. His body, therefore, was simultaneously highly celebrated because of his status and very identifiable because of its common characteristics.

By showing off his performative skills despite and because of his non-extra-ordinary body, Vusūqī both repeated the ideological norms of his time and challenged them. In many of his films, Vusūqī’s naked torso carries these dual functions. For instance, let us consider his body in Mamal Āmrīkāyī (Mamal the American, Shāpūr Qarīb, 1975, see Figure 4). In this film, he is playing the role of a small-time crook whose biggest goal in life is to immigrate to the United States to run a gas station. In the sequence from which I have chosen Figure 4, he is doing his routine exercises at his father’s house, instead of a traditional or modern gymnasium. His body is that of an amateur sportsman: he has some muscles in his arms, but not anything comparable to his contemporary superstars who usually had come to cinema after gaining some fame in manly sports such as wrestling. As a result, Vusūqī’s not-perfect posture along with his facial expression makes his body look rather comic instead of heroic.

Figure 9. The semi-comic posture of Vusūqī’s hairless torso simultaneously shows an exalted and common body, Mamal Āmrīkāyī (Mamal the American), directed by Shāpūr Qarīb (1975; Iran, Tehran, Sierra Film, DVD). Accessed via https://www.dailymotion.com/video/x82gpe9 (00:09:57).

Furthermore, his body seems to be completely hairless, which is contrary to the esteemed body of Iranian classic heroes and other male stars of the time, such as Fardīn (see Figure 5). Blake Atwood recognizes Vusūqī’s hairless body as a portent of change in the standards of male beauty, “perhaps inspired by European or American ideals.”20Blake Atwood, Reform Cinema in Iran: Film and Political Change in the Islamic Republic (New York: Columbia University Press, 2016), 152. Connecting the hairless bodies of Iranian men in Qaysar’s bathhouse scene to the historical tradition of equating the lack of body hair in young men with them being objects of homosexual desire for older men, he also acknowledges that “the hairless adult male bodies in Qaysar confound this traditional way of categorizing both sexual maturity and desire, especially at a time when sexual mores were changing.”21Atwood, Reform Cinema in Iran, 153.

Figure 10. Fardīn’s body conformed to the ideals of traditional manhood: physically strong with a hairy chest. Screenshot from Ganj-i Qārūn (Qārūn’s Treasure), directed by Sīyāmak Yāsamī (1965; Iran, Tehran, Pūrīyā Film, DVD). Accessed via https://shorturl.at/qODcm (01:16:02).

Another distinguishing characteristic of Vusūqī’s performance comes from the emphasis that he put on making his acting obvious through his body. Almost all of his pre-revolutionary films are marked with his obvious attempts in showing off the capabilities of his body. His various forms of bodily exaggerations sometimes gave way to the comic (as in Mamal the American or his other Gūgūsh duos) and sometimes led to different forms of physical violence and/or deformations of his body and face (as in Beehive or his Kīmīyā’ī-directed films).

Vusūqī’s overemphasis on performing with his body should be seen as an actor’s attempt to make all his talent and skills visible. At the time that he was active in Iranian cinema, the soundtrack of almost every movie was completely made in post-production. In order to make the production process faster and easier, the studios had long preferred to shoot the movies with no sound recording at all. Iranian sound studios, however, were technologically advanced thanks to the dubbing practices in effect since the mid-1940s. With a booming dubbing industry and a burgeoning pop music scene, reworking the whole soundtrack in Tehran’s numerous sound studios seemed like an ideal solution. It also enabled producers and directors to use the same dub actors who did the popular Persian voices of foreign stars for Iranian actors. For the Iranian actors, however, this meant losing control over the sonic aspects of their performance.

As a former dub actor, Bihrūz Vusūqī was well aware of the power of voice actors in Iranian cinema. Dub acting also helped him closely observe the works of those American actors who followed the Actors Studio style of identification between the actor and the character. In his memoir, Vusūqī stresses how he spent a lot of time researching his characters.22Nāsir Zirā‛tī, Bihrūz Vusūqī: Yak Zindigī-nāmah [Bihrūz Vusūqī: A Biography] (San Francisco: Araan Press, 2004), 250-253. For playing the role of the heroin-addicted Sayyid in The Deer, for example, he tried drugs. He also employed a real addict to be with him on the set of the film for him to imitate his posture and tone of voice.23Zirā‛tī, Bihrūz Vusūqī, 271-274. But, The Deer was only one of a dozen titles of his fifty-five films until 1979 in which he dubbed his own character.24Most of the roles in which Vusūqī dubbed his own performance belonged to his pre-superstar status, with exceptions such as The Deer and The Man from Tangistān County. His other dubbing double for that period was Manūchihr Zamānī who voice-acted for him in ten movies. Vusūqī’s guide to the dubbing industry, Manūchihr Ismā‛īlī, did his voice in fourteen films, some of which were titles that introduced him as a rebellious anti-hero, including Qaysar and Reza the Motorcyclist. Another well-known dub actor, Changīz Jalīlvand, dubbed Vusūqī in sixteen films, especially those with a more comic intonation because they allowed him to make those roles funnier by adding improvised quips. For more on the role of the dubbing industry in shaping the persona of Iranian actors, see Ahmad Zhīrāfar, Tārīkhchah-yi kāmil-i dūblah-yi fīlm bih Fārsī, jild-i duvvum: 1350-1392 [A Complete History of Dubbing Movies into Persian, Volume 2: 1971-2013] (Tehran: Kūlahpushtī, 2013), 726. Therefore, he had to work even harder to show off his acting skills in the films that he knew his voice would be replaced by another man’s in the post-production dubbing studio. To make his performance more visible, then, he both did rounds of pre-production character studies—such as being hospitalized in a mental hospital before playing the role of a mentally challenged character in The Heartbroken—and exaggerated his bodily performance in order to compensate for his lack of genuine voice.25Zirā‛tī, Bihrūz Vusūqī, 313-315. As a result of these exaggerations, Vusūqī’s body either tends toward comedy or toward violence and/or deformity in his more serious films. Figures 6 to 11 exemplify some of the facial deformations and changes that Vusūqī’s face and headwear undertook in some of his performances.

Figure 11. Dāsh Ākul lamenting the loss of his love in Dāsh Ākul, directed by Mas‛ūd Kīmīyā’ī (1971; Iran, Tehran, Rex Cinema & Theatre Company, DVD). Accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2IniV6u55Hw (01:01:49).

Figure 12. Balūch searching for his wife in Balūch, directed by Mas‛ūd Kīmīyā’ī (1972; Iran, Tehran, Mīsāqīyah Studio, DVD). Accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9XZdZ4Ud7Wo (01:36:35).

Figure 13. Peasants arguing over their right to land in Khāk (Soil), directed by Mas‛ūd Kīmīyā’ī (1973; Iran, Tehran, Mīsāqīyah Studio, DVD). Accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-cHUW8O4Tfk (00:38:05).

Figure 14. A heated argument over marital relations and infidelity, from the movie Sāzish (Compromise), directed by Muhammad Mutivassilānī (1974; Iran, Tehran, Payām Cinematic Organization, DVD). Accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=prKFYZuLDPc (00:36:14).

Figure 15. Sayyid (Behrūz Vusūqī) is shot and dying at the end of Gāvazn-hā (The Deer), directed by Mas‛ūd Kīmīyā’ī (1974; Iran, Tehran, Mīsāqīyah Studio, DVD). Accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q9H_C7NN-EE (01:38:44).

Figure 16. Behrūz Vusūqī, portraying a mentally ill character, finds a chain on the street. Sūtahdilān (The Heartbroken), directed by ‛Alī Hātamī (1978; Iran, Tehran, Payam Cinematic Organization, DVD). Accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wsuLNprT1h4 (00:12:17).

Iranian filmmakers made use of Vusūqī’s plasticity as a structural element of their movies. In several films, including Duzd-i bānk (Bank Robber, Isma‛īl Kūshān, 1965) and Reza the Motorcyclist, he played more than one role. In other films, such as Compromise, his character began to pretend to be someone else and thus continued the double act. Furthermore, whenever there was a need for heavy make-up for a character, such as in The Heartbroken, Vusūqī would be among the directors’ top choices. The master of Iranian art cinema, ‛Abbās Kīyārustamī, acknowledged this quality of Vusūqī as a formative element of his films. He was responsible for making the title credits of several Vusūqī/Kīmīyā’ī movies, including Qaysar and Reza the Motorcyclist. For the latter, he used blown-up photographs of the moment of the titular protagonist’s death for the beginning credits. The photos became grainier with each credit shot, so that in the last shot—introducing the director’s name—Vusūqī’s face becomes less visible than ever (see Figure 12).

Figure 17. Stills from opening credits of Rizā muturī (Reza the Motorcyclist), directed by Mas‛ūd Kīmīyā’ī (1970; Iran, Tehran, Payām Cinematic Organization, DVD). Accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jgMisAgPOoo (from left to right: 00:00:58, 00:02:45).

Vusūqī also emphasized the malleability of his body by overacting with his body as well as his eyes and facial gestures. In almost all of his films, there is a scene in which he smashes his hand to his forehead and then covers his face with that drooping hand (see, for example, the snapshots from The Ring-Necked Pigeon in Figures 2 and 3). Another signature gesture of his is the way he abruptly turns away his look from something or someone who is making him angry or tempted. At other moments, he stretches the muscles around his eyes and eyebrows without raising the eyebrow in order to portray a discovery or convey his inner transformation. Similarly, he uses different facial tics to distinguish a character, especially in his comedies. These exaggerations often lead to blemishing the beauty that one expects from a movie star or the naturalness that one expects from a good actor. The critics, therefore, were divided over Vusūqī’s acting style before his superstardom with Qaysar. There was one camp that considered his work only suitable for “panoramic sights such as deserts and streets,” because his “stereotypical gestures and distasteful makeup” would produce “a bad image in close-ups.”26The direct quote is from a review on Zanī bih nām-i sharāb [A Woman Named Sharab {Wine}] (Amīr Shirvān, 1967), written by Mīhan Bahrāmī in Sitārah-yi Sīnimā [Movie Star], no. 601 (January 31, 1968), cited in Umīd, Tārīkh-i sīnīmā-yi Īrān, 400. And there was a second camp that believed “with that flexible face and intrinsic intelligence, with that control over his body and the experience that he surprisingly has acquired from playing in pop movies, he cannot not be a reliable ace for our filmmakers [in the future].”27The direct quote is from a review on Bīgānah bīyā [Come, Stranger] (Mas‛ūd Kīmīyā’ī, 1968) by Parvīz Davā’ī (Payām) originally published in one of the issues of the weekly Sipīd u Sīyāh (Black and White) and cited in Umīd, Tārīkh-i sīnīmā-yi Īrān, 430. Following Qaysar, the second group became dominant and Vusūqī began to comfortably repeat his style in different performances, further generating a following among both other actors and his fans.

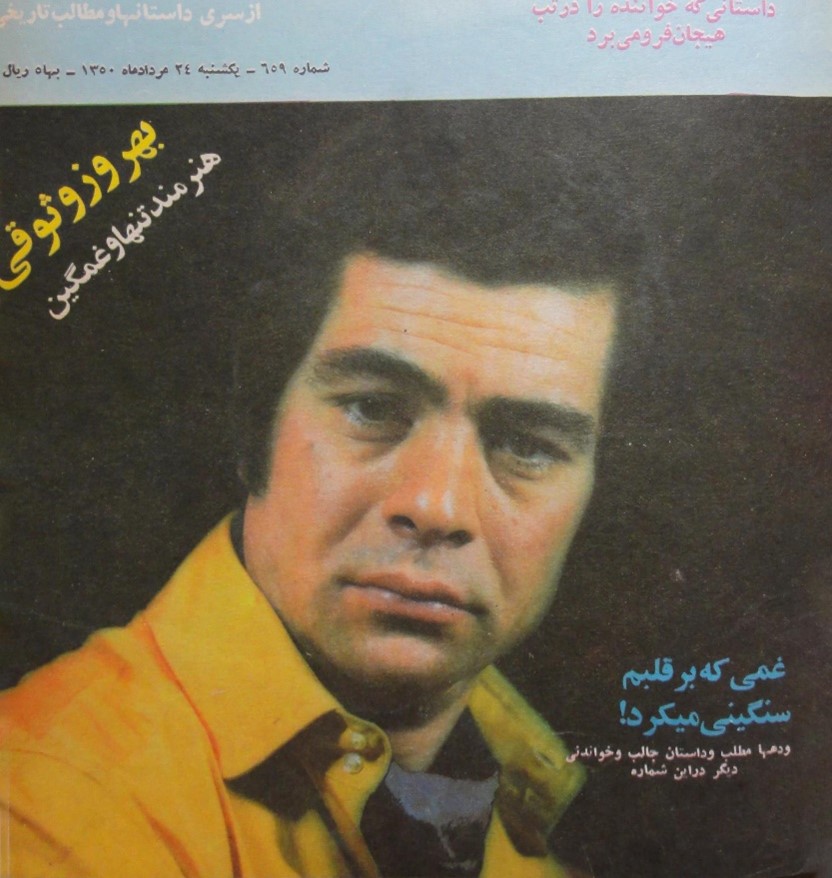

Vusūqī’s reliance on makeup and exaggerated gestures presents us with a body in change, a body in transit. It was also a body of different emotions. This statement might not seem to carry much weight for an actor’s body in performative media today. After all, actors are supposed to be able to transfer different emotions via their physicality. It is their job after all. However, considering the characteristics of Iranian pre-revolutionary cinema that pushed for typecasting and pigeonholing, Vusūqī’s ability to act out a regular spectrum of emotions was considered extraordinary.28A comparison with Nāsir Malak Mutī‛ī might be helpful here. Vusūqī narrates that during filming Bot [Idol] Īraj Qādirī, 1977), the director had a hard time convincing Malak Mutī‛ī to cry in a scene as the lūtī actor believed that a man in uniform—which was the role he was playing—would not cry. See Zirā‛tī, Bihrūz Vusūqī, 300. Figure 13, for example, is the front cover of one of the issues of the magazine Dukhtarān va Pisarān that emphasizes Vusūqī’s image as a “sad and lonely artist,” while his other images in the magazines of the time advertised his image as a mischievous, and later, a rebellious young man.29Dukhtarān va Pisarān [Girls and Boys], no. 659 (August 15, 1971). Thus, Vusūqī’s malleable image was more identifiable than, for example, those of the other stars of his era; an identification that would surprisingly sit comfortably with his status as a celebrity. He had an attainable body similar to the body of his male fans (not too muscular, not too hairy) but it was also the unattainable body of a star par excellence. His fans could identify with the emotions that his body conveyed but he was also occupying a space beyond the regular spectrum of normal emotions because of his exaggerations and the bigger-than-life nature of cinema in general, and fīlmfārsī in particular.

Figure 18. “Bihrūz Vusūqī: A Sad and Lonely Artist.” The front cover image of Dukhtarān va Pisarān [Girls and Boys], no. 659 (August 15, 1971).

Violence

Vusūqī’s pliable body also would welcome violence. The relationship between masculinity, violence, and power further illustrates the transitional role of Bihrūz Vusūqī as a male icon. A leading scholar on masculinity, Michael S. Kimmel sees violence as men’s expression of their powerlessness when feeling entitled to power. In other words, the sense of entitlement (to power) drives powerless men to express forms of anger that are fed by frustration.30Michael S. Kimmel, “Chapter 14: Reducing Men’s Violence, The Personal Meets the Political,” in The Gender of Desire: Essays on Male Sexuality, ed. Michael S. Kimmel (New York: State University of New York Press, 2005), 227-234. This configuration of male violence is completely applicable to almost all of the physical and verbal forms of the cinematic violence that Vusūqī represented. Here, another difference between his comedies and non-comedies emerges. In the comedies, he usually wins his fights (whether verbal or physical), while in non-comedies, he either loses his battles or leaves the audience with a bitter feeling of failure.

The peak of his failed violence is portrayed in Beehive. In this film, Vusūqī plays the role of Ibī, a former wrestler with a silver medal in an important tournament. For unknown reasons, however, he has not continued sports. The film begins with his release from prison following a six-month stint due to committing a small robbery. Not having any specific place to call home once on the outside, like many other lumpans of fīlmfārsī, he frequents a traditional coffee shop (qahvah-khānah) to spend his nights. There, he loses a traditional gambling game to a macho man, a friend from the prison, whose character is a reiteration of the action hero that borrows elements from the lūtī. The winner decrees that the loser must go to the northern district of Tehran and drink in any bar that he orders, but without paying for it. This is only a game, and as the old lumpans in the coffee shop mumble, this decree is not implementable. But then, remembering his defeat in the final match of a wrestling tournament to the same homeless man whom he witnessed die the night before, Ibī changes into the clothes that the man had given him, and chooses to perform the decree. While it is not clearly stated why Ibī does so, his reasons are metaphorically implied: in this sociopolitical climate, the old heroes (i.e., the men) have no future but to get addicted to drugs, end up in places such as the coffee shop, and die. So, to not let heroic behavior (i.e., manhood) die, one must defend his honor even if he knows this defense will end in his demise. This is one of those more explicit messages that are constantly repeated in Vusūqī’s other milestones too, including in his Kīmīyā’ī trilogy, Qaysar, Reza the Motorcyclist, and The Deer. In Beehive, however, this philosophy takes on more crystal-clear imagery through the employment of the metaphors of the city and violence.

The economic and cultural geography of Tehran plays an important role in the progress of the film’s plot. Ibī must go up north on Pahlavi Street (now, Valī-i ‛Asr Street) which runs from the poor southern neighborhood of Rāh Āhan to the rich northern neighborhood of Tajrīsh. The impossibility of social class mobility in this journey becomes obvious in the contrast between Ibī’s clean and rather well-dressed image in the rundown bars of the south of the city at the beginning of his path and his bloody and smashed up face in the chic cabarets of the north of the city at the end of his route (see Figure 14).

|

|

Figure 19. Screenshots from Kandū (Beehive), directed by Farīdūn Gulah (1975; Iran, Tehran, Sierra Film, DVD). The lefthand image shows Ibī at the beginning of his journey in the poor neighborhoods of the south of Tehran. The righthand image shows Ibī at the end of his journey in the rich neighborhoods of the north of Tehran. Accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VZ_vlHsX4SQ (from left to right: 00:46:10, 01:31:17).

Ibī drinks in seven bars and gets beaten in four of them. In this modern play on the seven-stages of ‘irfān or the haft khvān, Vusūqī’s body transforms from that of a clean young man’s to a horribly beaten, bloody, body with a smashed face.31Literally meaning “to know” or “to understand” and variously translated as mysticism, Sufism, gnosis, transcendental awareness, etc., ‘irfān is an Islamic-Iranian religious practice essentially holding that the goal of man must be to reach toward God by completing a seven-stage divine path called soluk (path, behavior). At least in its layering and seven stages, ‘irfān is similar to the pre-Islamic concept of haft khvān, which refers to the seven stages that some of the pre-Islamic heroes or pahlavānān, like Rustam of the Firdawsī’s Shāhnāmah, had to go through. This trajectory occurs with a masochistic pleasure for the protagonist, because he knows he is sacrificing his material body for his abstract but sacred concept of honor. Once, after being beaten and pissed on by a security guard, he confesses to his sidekick that having been beaten all his life, he finds a kind of joy in the process: “Always, after being beaten severely, I feel different. Like a man who’s itching and is scratched properly. I like the pain. It’s like they have signed my leave of absence.”32Kandū (Beehive), directed by Farīdūn Gulah (1975; Iran, Tehran, Sierra Film, DVD), 01:05:25-01:05:39, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VZ_vlHsX4SQ We do not know whether the audience feels connected to this depiction of pain but considering the social origins of this character and the exceptional imagery of the film—a rare color film, an epic song written for the film and performed by a rising star in Iranian pop music during the era also named Ibī, and the meticulous choreography of the fight scenes—the possibility of audience identification is not improbable. Moreover, Vusūqī’s performance of violence ends in nothing but the disintegration of a star’s body on screen and thus becoming more recognizable, or at least earthlier, than ever.

Vusūqī’s violent characters fail in their fights here in Beehive and in many of his other films as well. This model of failure, however, provided a very relatable experience for the Iranian audience, many of whom have witnessed or been engaged in constant battle with various forms of authority and patriarchy over the past half-century. The world of other male stars in Iranian cinema offered the audience a modern avenue for re-experiencing traditional conceptualizations of male heroes: men who would act heroically in everything associated with manhood, from fights to chivalry to sex. The cinematic world of Bihrūz Vusūqī, however, was a bitter, dark, and poisoned environment in which a man got beat up by different forces without being able to do anything about it except to take pleasure in the process of humiliation. Failure, then, could also mean resistance against powers beyond one’s control.

The entanglement of Bihrūz Vusūqī’s persona with violence is not limited to his characters’ bodies. It is also evident in his many verbal attestations to the decline of an era. In particular, we see this in many of his angry monologues. Qaysar, in this sense, is most remembered by the fans who would continue to re-deploy its protagonist’s rant against men of the past in different situations. The film is about a young man from the south of Tehran, Qaysar, who returns home from a temporary job in the city of Ābādān only to find out that his sister, Fātī, has committed suicide after being raped. Furthermore, he finds out that his lūtī brother, Farmān (Malak Mutī‛ī) went to confront and take revenge for the death of their sister from the rapist. The luti was barehanded, but the rapist and his two brothers use a knife to kill Farmān. At the moment of his death, Farmān shouts: “Qaysar, where are you [to see] that they killed your brother!”33Qaysar, directed by Mas‛ūd Kīmīyā’ī (1969; Iran, Tehran, Ārīyānā Film, DVD), 00:20:27-00:20:31, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ahkqef86u4w This scene has a symbolic significance in Iranian cinema, for it connects the failure of one mode of hegemonic masculinity (that of Malak Mutī‛ī’s lūtī) and the birth of another mode (that of Vusūqī’s rebellion). Yet, to make this transition even more clear, the writer/director Kīmīyā’ī embellishes the film with several dialogue-filled scenes about men and manhood. First, when Farmān decides to take revenge for his sister’s death, it is his uncle, a former athlete of traditional zūrkhānah sports, who admonishes him against using a knife:

It is humiliating for a pahlivūn, Farmūn.34Pahlivūn is the colloquial form of saying pahlavān, a traditional male athlete in the zūrkhānah (a traditional martial-arts arena or gymnasium; colloquial: zūrkhūnah) sports. The same goes for Farmūn instead of Farmān. Don’t judge the skin and bone that I am now. There was a time that they rang the bell in any zūrkhūnah that I stepped into. There were times when I would wrestle for two days in a row. But I never touched a knife. Nāmard-hā must fear one’s arm, not a knife.35Nā-mard literally means non-man, and figuratively means a non-chivalrous man. You give the knife to a child, and he can cut his hand. I used to pull a brick out of the wall, but now what? My eyes are watery, and my feet are shaking. How do you think I feel? My heart is coming out of my chest. I feel like my heart is burning because of Fātī. But what can I do? It is like death for a pahlivūn. You had vowed Farmūn. Give me the knife and say a prayer.36Qaysar, directed by Mas‛ūd Kīmīyā’ī, 00:16:26-00:17:23.

Figure 20. Screenshot from A screenshot from the film Qaysar, directed by Mas‛ūd Kīmīyā’ī, (1969; Iran, Tehran, Ariyana Film, DVD). Farmān decides to take revenge for his sister’s death, it is his uncle, a former athlete of traditional zūrkhānah sports, who admonishes him against using a knife. Accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=itYE35x-umQ ( 00:17:04)

Farmān gives the uncle the knife and goes barehanded, resulting in his death. This scene finds a parallel after Qaysar returns home after killing the first of the rapist’s brothers. Reading Firdawsī’s Shāhnāmah, the uncle begins to advise him too: “It’s far from being fair and being a [chivalrous] man [to kill those brothers with a knife and in the surreptitious way that you did].”37Qaysar, directed by Mas‛ūd Kīmīyā’ī, 00:46:14-00:46:16. But this time, Qaysar does not let the uncle go on. Instead, Qaysar begins his diatribe about manhood in modern Iran, which can be read like a manifesto on the form of masculinity that Vusūqī’s persona represented in his following films:

I respect you, uncle, but don’t tell me about [chivalrous] manhood for I am sick of it. Who showed me a speck of manhood so that I can show him plenty? This world has always been full of cheating and nāmardī [unmanly behavior]. Anyone that I respected, betrayed me. Didn’t you see Farmūn? He could displace a whole neighborhood. When he was bothered, he used to drink and yell so that the walls tremble and all those nā-mard [non-chivalrous men] would hide in the gutters like rats. But what happened to him? He went to a pilgrimage and repented. He started to work like a man to have halal [Islamically lawful] bread. But did they let him? This is the system of our time. This is our time, uncle. If you don’t hit them, they hit you. Now, where is brother Farmūn?38Qaysar, directed by Mas‛ūd Kīmīyā’ī, 00:46:17-00:46:59.

Following this angry monologue in which Qaysar vows to kill the remaining two brothers, the uncle closes his extra-large edition of the Shāhnāmah with a sense of symbolic finality. Thus, it becomes clear that Qaysar is not going to walk along the path of the heroes of the Shāhnāmah such as Rustam, traditional athletes and sports heroes such as his uncle, or lūtīs such as his brother Farmān.

The inefficiency of these previous forms of manhood finds other dialogue-based manifestations in Vusūqī’s films, including his next collaboration with Kīmīyā’ī. One of the two roles that he plays in Reza the Motorcyclist is that of small-time crook, Rizā, who has only one attachment in his life: his motorcycle. Rizā is also highly critical of movie heroes such as Fardīn. In a sarcastic exchange of comic lines with his mother, he says: “I have just found out that there is a better kind of life, so why should I say that we’d better remain content and happy just with our bread and yogurt? These are all lies, Mom.”39Rizā muturī (Reza the Motorcyclist), directed by Mas‛ūd Kīmīyā’ī, 00:54:44-00:54:52. Later, the film emphasizes Vusūqī’s transitional model of manhood in another verbal attack on men of the past, this time the lūtīs. Sitting in the neighborhood bakery having his breakfast, Rizā checks out the images of some zūrkhānah athletes on the wall and begins to ask the baker about them:

Rizā (pointing to a picture): Who’s this, Mr. Asghar?

Baker: Husayn Ganjah’ī.

Rizā: What does he do now?

Baker: He’s in jail.

Rizā (pointing to another picture): Who’s this other one, Mr. Asghar?

Baker: Rizā ‛Attār. He could do traditional powerlifting for two full days straight. He’s also in jail.

Rizā (pointing to another picture): Who’s this other one?

Baker: Akbar Khunchah’ī. Everyone in this neighborhood was at his command.

Rizā: What does he do now?

Baker: He’s a heroin addict.

Rizā (pointing to another picture): I know this one.

Baker: Yep. He’s one of those famous traditional heroes. Ahmad Haydarī. He’s now the chauffeur of a rich family. He has a hand-to-mouth income now.40Rizā muturī (Reza the Motorcyclist), directed by Mas‛ūd Kīmīyā’ī, 01:22:52-01:23:34.

Vusūqī’s oeuvre makes it obvious that life in Iran of the 1970s had made the previous hegemonic modes of masculinity either fantasies or the phenomena of a bygone era. Yet, what Qaysar, Beehive, Reza the Motorcyclist, and The Deer present instead does not provide a cohesive ground for a definitive idea of an alternative form of manhood. Vusūqī’s characters in these films vacillate between their distance from both the past and the future. They know what they are not, but they do not know what they are. They do not want to (or cannot) be like Fardīn and Bayk and Malak Mutī‛ī, but they do not know what they can be like. Maybe that is why they have no future but dying in pain in the end.

As a result of such struggles, many of the anti-heroes that Vusūqī portrayed on the Iranian screens were doomed to fail. Among his overall fifty films before the Revolution, Vusūqī’s characters die in fourteen films (25%), are severely wounded in eight films (14%), and are imprisoned by the end of four other films (7%). In these films, his rebellion against the past remains at the level of a rebellion without any fruitful results, which partly explains the frequency of words such as ‛usyān (rebellion), tughyān (revolt), and i‛tirāz (protest) in the reviews written about his works. These failed revolts were specifically appealing to an audience who was witnessing the many revolts against the Shah’s regime at the time, all to no avail until February 1979. Therefore, it may be possible to see Vusūqī’s rebellion as not only against his (and society’s) contemporary modes of manhood, but also against the authoritarian forces that discredited those forms of masculinity by class discrimination and political despotism. Yet, as the bitter ending of many of his films shows, he was, once again, also a failure in many aspects.

A final trope of Vusūqī’s textual failures within the context of Iran is the issue of fatherhood. There is no thorough research on the relation between different modes of masculinity and the conceptualizations of fatherhood among Iranians.41The few monographs on Iranian masculinity have continued to remain rooted in traditional studies of masculinity in Iranian studies. For more recent examples, see Sivan Balslev, Iranian Masculinities: Gender and Sexuality in Late Qajar and Early Pahlavi Iran (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2019); and, Wendy DeSouza, Unveiling Men: Modern Masculinities in Twentieth Century Iran (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2019). Even in Western contexts, the relationship between fathering behavior and representations of manhood is not extensively researched.42Marsiglio and Pleck define fathering behavior based on the male parent’s involvement or investment prior to conception, during pregnancy, and throughout their children’s lives. See William Marsiglio and Joseph H. Pleck, “Fatherhood and Masculinities,” in Handbook of Studies on Men and Masculinities, eds. Michael S. Kimmel, Jeff Hearn, and R. W. Connell (London: Sage, 2005), 249. Yet, in their literature review on the issue, William Marsiglio and Joseph H. Pleck emphasize paternity as an emblem of masculinity in at least one qualitative study on young men between the ages of sixteen and thirty.43Marsiglio and Pleck, Fatherhood and Masculinities, 259. For the referred study, see W. Marsiglio and S. Hutchinson, Sex, Men, and Babies: Stories of Awareness and Responsibility (New York: New York University Press, 2002). I do not have access to the relevant statistics about the percentage of single men or childless married men under the age of forty in Iran of the 1960s and the 1970s. Nevertheless, Vusūqī’s portrayal of manhood in the films of this period does not seem to reflect societal norms. Among his fifty-five cinematic performances between 1961 and 1978, his characters were only fathers in eleven films (20%). In two of these eleven titles, the child turns out to be dead at birth, and in another film, we see him only as a father-to-be. This lack of children can partly be due to the social conceptions about lumpans as people who were unable to commit to their families.44Akbari, for example, states that “due to his life circumstances and his [lack of a] job and his social characteristics, the lumpan is deprived of matrimony and forming a family for good.” See Akbarī, Lumpanism, 49-50.

However, when we consider that Bihrūz Vusūqī also never became a parent in his real life, the rarity of children in his films may find another meaning. As the embodiment of transition and failure, the image of this anti-hero can only be complemented with impenetrable loneliness.45It should also be noted that children have historically been of great dramatic importance to Iranian cinema, and many titles of fīlmfārsī benefitted from the dramatic turns that the existence of a child would bring to their plots.

Conclusion

As noted earlier, abrupt cessation of a star’s career could potentially lead to cult status. This indeed happened to many movie stars of both sexes of Iranian pre-revolutionary cinema. Following the Revolution, the structure and format of the national film industry changed in several significant and related ways. For example, many actors faced legal charges for promoting non-Islamic values and sleaze on Iranian screens. In a series of rounds, tens of actors were summoned to the newly established Islamic Revolutionary Courts in the first two years after the Revolution. In their third official announcement in the newspaper Kayhān, the Revolutionary Court summoned ten new actors and singers to the court branch centered in the infamous Ivīn Prison on March 13, 1980. The title of this announcement highlighted four names among the summoned: Fardīn, Bihrūz Vusūqī, Malak Mutī‛ī, and Bayk Īmānvirdī.46Kayhān Newspaper, no. 10952 (March 12, 1980), 13.

Many of the summoned actors, especially female stars, were permanently banned from appearing on screen and stage. Some, like Vusūqī, had already left the country before the Revolution. Some, like Bayk (as known to his fans), emigrated from Iran after the court order. And some, like Fardīn and Malak Mutī‛ī, remained in the country.47Some of those actors managed to stay in the country and gradually were permitted to make movies or even to appear again on screen as actors. Īraj Qādirī and Said Rad, for example, re-emerged in movies after a period of absence, however, they never enjoyed the same attention and popularity that they had in the past. In fact, their return considerably lowered their chances of becoming superstars or cult stars. The inaccessibility of all these banned actors, however, played an important role in their cultification. Counter-memory and nostalgia can partly justify this process. Developed by Michel Foucault in the 1970s, counter-memory refers to the act of remembering by the broad category of “subjugated knowledges.”48Michel Foucault, Society Must Be Defended (New York: Picador, 2003), 7-9. All authoritarian regimes of power tend to rewrite history in ways that suit their political purposes. Omitting or blemishing the past with politically charged narratives is a part of the political agenda of any new center of power. And yet, the resistive act of remembering against the grain contributes to the insurrection of subjugated knowledge and the production of counter-histories.49For an excellent elaboration of Foucault’s concepts of counter-memory and counter-history, see Jose Medina, “Toward a Foucaultian Epistemology of Resistance: Counter-Memory, Epistemic Friction, and Guerrilla Pluralism,” Foucault Studies no. 12 (October 2011), 9-35. Thus, simple actions such as illegally collecting pre-revolutionary films, talking about them in unofficial gatherings, repeat-viewing them, and quoting them can all be considered subversive acts against hegemonic memory.

If counter-memories of pre-revolutionary films and stars contribute to their maintenance in society’s collective memory, it is nostalgia that endows them with a symbolic value. My use of nostalgia draws on psycho-cultural studies that liberate this concept from both its temporal and spatial boundaries, as developed by Susan Stewart and Svetlana Boym. In her definition of nostalgia as a social disease, Stewart asserts that the craved past has never actually existed; neither for those who have lived in the original time of nostalgia nor for their offspring.50“Nostalgia is a sadness without a cause, a sadness which creates a longing that of necessity is inauthentic because it does not partake in lived experience. Rather, it remains behind and before that experience. Nostalgia, like any other form of narrative, is always ideological: the past it seeks has never existed except as narrative, and hence, always absent, that past continually threatens to reproduce itself as a lack.” Susan Stewart, On Longing (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1984), 23. Similarly, Boym considers nostalgia as nothing but a fantasy: “a longing for a home that no longer exists or has ever existed. Nostalgia is a sentiment of loss and displacement, but it is also a romance with one’s own fantasy.”51Svetlana Boym, The Future of Nostalgia (New York: Basic Books, 2001), xiii. These conceptualizations of nostalgia as factitious memories augment the atemporality of the objects of nostalgia. Thus, it is possible for even the generation born after the Revolution to feel nostalgic toward movie stars of the past and to contribute to their engravement in counter-histories through acts such as writing this essay. To many Iranians, then, each of the banned stars became cultified images of the type of cinema that they represented. The fandom of Malak Mutī‛ī, Fardīn, or Bayk was not merely a star fandom anymore; it was a fannish nostalgia for types of manhood, film style, and cinema experience which would not be possible anymore as they were forbidden. While this argument is also true for the case of Bihrūz Vusūqī, it is important to note that he had already become a cult star after Qaysar in the 1970s.

Vusūqī’s cult status before the Revolution was symbolized in the Qaysar-cut hairdo, the wave of films and film actors imitating Qaysar and Vusūqī’s other performances, and the press hype about whatever he did in his professional or private life.52To read more about the wave of Qaysar, see Parvīz Ijlālī, Digargūnī-i ijtimā’ī va fīlm-hā-yi sīnimā-yi dar Īrān: Jāmi’ah-shināsī-i fīlm-hā-yi ‘āmmah-pasand-i Īrānī 1309-1357 [Social Change and Feature Movies in Iran: Sociology of Iranian Popular Films 1930-1978] (Tehran: Āgāh, 2016), 181-184. To see more about the popularity of the fashion and attire of Behrouz Vusūqī in Qaysar, see Sitārah-yi Sīnimā [Movie Star], no. 788 (July 19, 1972), 43; and, Sitārah-yi Sīnimā [Movie Star], no. 789 (July 26, 1972), 6. While a thorough investigation of Vusūqī’s role as an important contributor to the Iranian pre-revolutionary film industry and his publicized private life has been beyond the scope of this article, it is likely that such research will further distinguish him from the other Iranian stars of the time. The factionalism among film critics over the nature of Vusūqī’s brand of cinema (intellectual or fīlmfārsī), his relationships with female stars (romantic loner or womanizer), and his connections to the centers of political power (a symbol of resistance or an agent of the status quo) each shed light on controversial avenues that further contributed to the appropriable nature of a cult star image at the time of his active career—an image that is far from fading in the long years of his exile.

Vusūqī’s image after the Revolution has been intertwined with different forms of vocal, bodily, and media absence. Being a cult star, however, means occupying a space within resurging subjugated knowledges. This explains why the scope of Vusūqī’s fandom has extended to many unanticipated areas of the public sphere. In numerous post-revolutionary popular films, for example, Vusūqī’s gestures and lines of dialogue are officially quoted, such as in the extremely popular comedies Kulāh-qirmizī va Pisarkhālah (Redhat and Cousin, Īraj Tahmāsb, 1994) and Hizār-pā (Millipede, Abulhasan Dāvūdī, 2017), and even in Iranian politicians’ speeches.53See, for example, “Vaqtī sukhangū-yi dawlat yād-i fīlm-i Qaysar mī-uftad! [When The Speaker of the Government Is Reminded of the Movie Qaysar!],” mashreghnews.ir (July 23, 2019), https://www.mashreghnews.ir/news/977518/. Bihrūz Vusūqī’s forced absence from the lives of Iranians has had a long shelf life. But his absence has also been largely conspicuous. Such felt absence, then, is one of the powers of an original cult star.

Vusūqī’s absence from official Iranian screens has been contrasted with his continuous presence in the lives of Iranians as both a nostalgic icon and as a symbol of resistance. The recent controversy surrounding the movie Āshghāl-hā-yi dūst-dāshtanī (Lovely Trash, Muhsin Amīryūsufī, 2012) provides a cogent example of a cult star’s present absence and clearly denotes the longevity of his influence and its official recognition within Iranian society through to the present day. Banned for more than six years, a censored version of the film was finally granted a limited theatrical release in February 2019.54The story of this version of the film takes place during the 2009 unrest in Iran. An old lady who is living alone becomes fearful that the country’s disciplinary forces may raid her house because she inadvertently let some protesters take shelter in her yard for a few hours. Throughout most of the film, which takes place during the night after this incident, the old woman talks to four framed pictures in her house in order to find out where each of them has stashed their suspicious belongings. These pictures belong to the men in her life: her deceased husband (a former royalist), her executed brother (a communist), her martyred older son (dead in the Iran-Iraq war), and her long-since migrated younger son (the only one still alive out of the four but not in Iran). In the end, the woman gathers everything belonging to these men into a trash bag, including their framed pictures, and throws the bag into a garbage can on the street. Lovely Trash did fairly well in the box-office, ranking seventeenth among the seventy-seven total Iranian films screened that year. See “Furush-i kull-i fīlm-hā-yi ikrān shudah dar sāl-i 1397 [The Overall Sales of the Movies Screened March 2018-March 2019],” cinetmag.com, accessed February 8, 2020, http://www.cinetmag.com/Movies/BoxOfficeYearly.asp?Saal=1397&Locality=240&Open=No. It also garnered fairly positive reviews admiring its social commitment, originality, and surrealistic undertone. See Jahānbakhsh Nūrā’ī, “Taghvīm-i kuhnah-yi tars-u-larz [The Old Calendar of Fear and Trembling],” Film, no. 566 (March 2019), 84-86; Muhsen Ja‛farī Rād, “Dilnishīn ammā talkh [Pleasant but Bitter],” Film, no. 566 (March 2019), 86-87; and, Mustafā Jalālī Fakhr, “Qahvah-yi talkh [Bitter Coffee],” Film, no. 566 (March 2019), 88-89. But the film’s eight-week screening was not the end of the story. In January 2020, director Amīryūsufī announced that he had prepared another version of the film entitled Āshghāl-hā-yi dūst-dāshtanī-i asl (Lovely Trash, the Original). Amīryūsufī stated that this other version was fifty-five minutes longer than the eighty-eight-minute version released in Iran, and thus, according to international standards, it would be considered a whole new film for submission to international film festivals.55Amīr Pūrīyā, “Qadighan-hā-yi dūst-dāshtanī-i asl [The Lovely Forbidden, the Original],” Asoo.org (January 9, 2020), https://www.aasoo.org/fa/notes/2557. More importantly, Amīryūsufī revealed that this version included a new character played by Bihrūz Vusūqī. Consequently, the rumors about the impact Vusūqī’s participation in this film had on its long-standing ban and heavy censorship continued to surge through virtual media.56See, for example, “Bihrūz Vusūqī dar fīlm-i Āshghāl-hā-yi dūst-dāshtanī-i asl [Bihrūz Vusūqī in the Movie Lovely Trash, the Original],” tabnak.ir (December 23, 2019), https://www.tabnak.ir/fa/news/946109/. The omission of Vusūqī underlines the Iranian cultural policymakers’ stringent attitude toward him as a public figure, especially when compared to his counterparts in the fīlmfārsī era. After all, Malak Mutī‛ī did play a small role in a movie before his death—Naqsh-i Nigār (Negar’s Role, ‛Alī ‛Atshānī, 2013)—and Bayk and Fardīn were celebrated in several magazines and books without substantial repercussions.57See, for example, Māh-nāmah-yi Haft Nigāh: Vīzhah-nāmah-yi Rizā Bayk Īmānvirdī [Haft Negah Monthly: Special Issue on Rizā Bayk Īmānvirdī], no. 34 (October 2013); and, ‛Abbās Bahārlū, Sīnimā-yi Fardīn bih ravāyat-i Muhammad ‛Alī Fardīn [Fardīn’s Cinema as Narrated by Muhammad ‛Alī Fardīn] (Tehran: Qatrah, third edition 2014). Vusūqī’s absent presence in Lovely Trash, on the other hand, was deemed unacceptable.

In this article, I explored Vusūqī’s exceptional role in Iranian cinema both before and after the 1979 Revolution by analyzing his cult status and his enduring significance to his fans. I started by contextualizing centrality of male stardom in Iranian pre-revolutionary cinema. Reviewing the variety of hegemonic masculinities in the popular films of the 1960s and the 1970s, I introduced Bihrūz Vusūqī as a superstar whose image paved the way for a transitional masculinity that bridged the fatalist, the chivalrous, and the action hero with the rebellious man. I argued that Vusūqī’s image portrayed rebellions against not only the diegetic representations of power but also against other conventional and popular modes of manhood in fīlmfārsī. He did so by imbuing his on-screen persona and his film performances with a repertoire of repetitive motifs, including his uneasy relationship with sex, his versatile body, and his violent verbal outbursts. While these rebellions signaled the failure of hegemonic masculinities, Vusūqī’s many diegetic failures—including the bitter endings of many of his films—also implied the failure of his particular brand of transitional masculinity. This embodiment of double failure made Vusūqī’s image even more identifiable for a society on the verge of a revolution and, in all likelihood, will continue to do so amid the ever-shifting surges of subjugated knowledges, counter-histories, and inevitable revolts in the years to come.

Cite this article

Appearing in fifty-five films between 1969 and 1978, Behrouz Vossoughi became an enduring emblem of masculine stardom in Iranian cinema, maintaining his iconic status long after his involuntary exile and enforced departure from the national film industry. As a central figure in both the commercial realm of Filmfārsi and the emerging wave of alternative and auteur-driven cinema, Vossoughi’s on-screen persona was defined by a complex performance of rebellion—against patriarchal hierarchies, socio-cultural norms, and state authority. This defiance, however, was marked not by triumph but by inevitable collapse, rendering his characters both relatable and tragic. His roles mirrored a broader societal disillusionment with dominant structures of power, while simultaneously exposing the limits of resistance in the absence of a transformative horizon. This article contends that Vossoughi’s cult status endures not merely because of the abrupt cessation of his cinematic career, but because he came to embody a distinctly Iranian articulation of masculine crisis and existential rebellion—one that captured the contradictions of a generation caught between aspiration and defeat, modernity and tradition.