Certified Copy (2010)

Figure 1: Poster for the film Certified Copy, Directed by ‛Abbās Kiyārustamī, 2010.

An English art critic, James Miller, comes to Tuscany to promote the Italian translation of his latest book, Certified Copy. He delivers a frankly uninspiring lecture on the inseparability of the copy and the original to a small audience, who desultorily clap when it is over. While he is talking, an attractive middle-aged woman, whom we only ever get to know as Elle, whispers to the organiser and passes on her details to give to the speaker. After his lecture, James goes to meet Elle in the downstairs cellar from which she runs her antiquities business. After a brief discussion, they decide to drive through the countryside to the nearby town of Lucignano. Elle wants to show James Musa Polimnia, an example of a work of art that was once thought to be original but is now understood as a copy. The painting is housed in a museum near a church, in which newlyweds pose for photos together and later celebrate in a garden. James and Elle then walk to the town square, where there is a much-loved statue depicting a woman leaning her head on a man’s shoulder, which attracts tourists from across Europe. But in between, they have a coffee in a local café, and while James is outside taking a phone call, the elderly woman serving them speaks to Elle as though she and James were married. “He’s a good husband though,” she says to Elle, despite observing James’s typically brusque behaviour. “How do you know?” asks Elle. “I can tell,” replies the woman, offering her opinion based on a lifetime of experience.

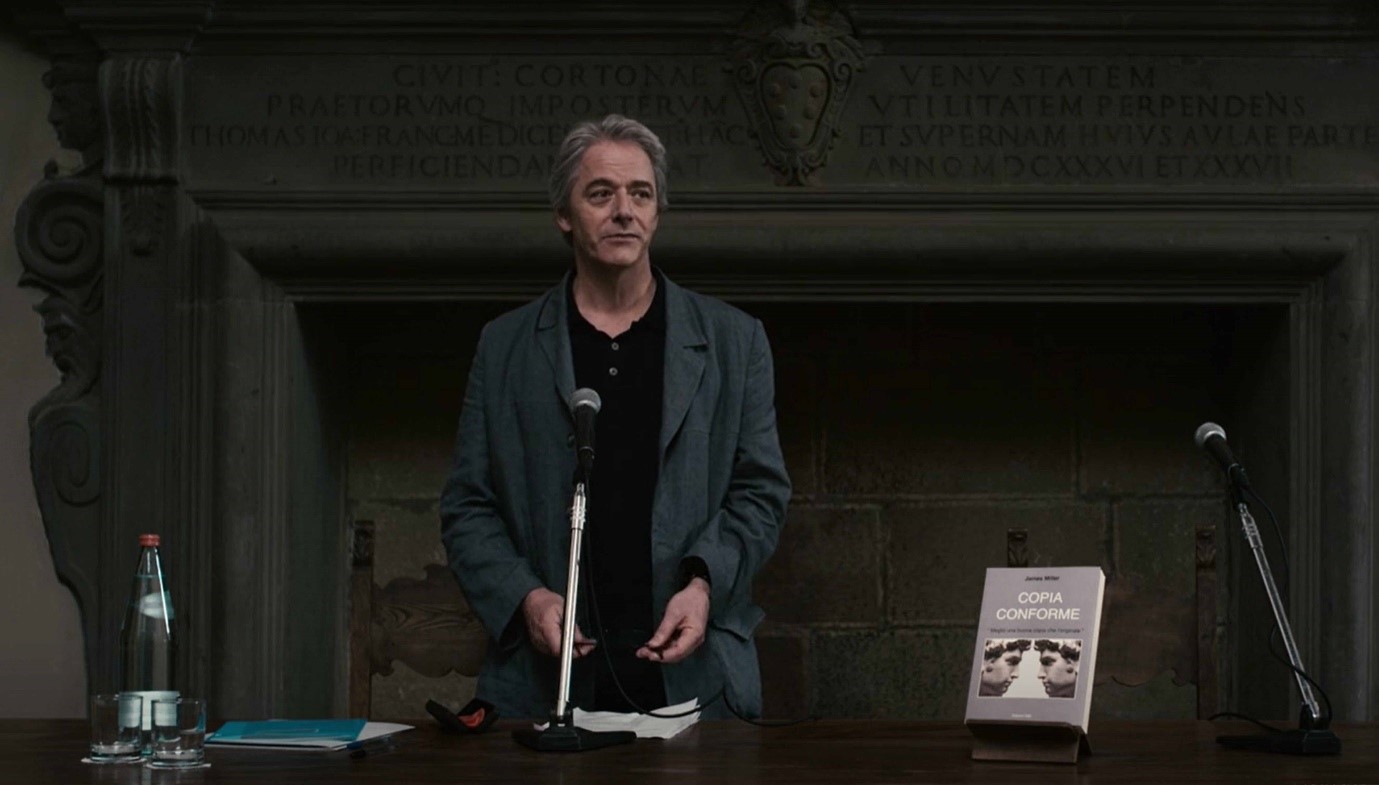

Figure 2: James Miller promoting the Italian translation of his latest book, Certified Copy. A still from the film Certified Copy, directed by ‛Abbās Kiyārustamī, 2010 (00:33:00).

After this small incident, almost inexplicably, James and Elle behave as though they were actually married. We have already heard James tell the story, both in his lecture and in response to a question from Elle, that the inspiration for his book came from seeing a mother and son at the Piazza della Signoria in Florence, where, famously, there is a copy of Michelangelo’s David. We begin to suspect that James is in fact referring to his own wife and child. (We saw Elle with her son at the beginning of James’s lecture, and, in retrospect, we even remember seeing her, James and the boy together at the beginning of the film.) Later, in a restaurant, James, having decided that he does not like the wine, goes outside briefly, then comes back and delivers a lengthy criticism of Elle for having nodded off once in their car, in behaviour that we suspect only a wife would tolerate. Earlier, indeed, we now realise that a pair of French tourists, visiting the statue of the woman leaning her head on the man’s shoulders in the square, had treated them like husband and wife. The man offered James advice as to how to make Elle happy, and they did not correct them. Then, most explicitly, towards the end of the film, while still in Lucignano, Elle asks James to try to remember where they spent their honeymoon. When James says he cannot remember, Elle enters the hotel behind them, asks the clerk for the keys to the room they once stayed in, goes up the stairs with James and lies beckoningly on the bed. She says to him that this was where they spent their wedding night fifteen years ago and asks him to look out the window at the nearby church to remind him. James, for his part, in what we might alternately take to be either a typical expression of his narcissism or a rare moment of self-doubt, stares at his reflection in the bathroom mirror while the church bells ring out, celebrating another marriage.

Figure 3: James meeting Elle in the downstairs cellar where she runs her antiquities business. A still from the film Certified Copy, directed by ‛Abbās Kiyārustamī, 2010 (00:19:20).

Of course, as any number of commentators have remarked, it is difficult, no matter how we understand their relationship, entirely to make sense of events in the film. If the couple is not married, what is it that suddenly makes them pretend they are? There does not appear to be any immediate physical attraction between them. James’s pompousness and occasional flashes of bad temper are not obviously appealing qualities. However, Elle does not seem to be put off by them, and at a certain point, after a particularly unjust outburst from James, she even goes into the bathroom of the restaurant to put on lipstick and earrings to make herself even more beguiling and attractive.1Elle is played by the famously glamorous French actress Juliette Binoche and James by the first-time actor English baritone William Shimell. On the other hand, if they are married, why pretend otherwise? Why does James tell the story of seeing a mother and child at the Piazza della Signoria as though they were anonymous, when it is more than likely that he is referring to his own wife and child? If he is referring to his son, why does he not properly greet him before his talk or ask to meet him as any responsible father would do, even if he is separated from the mother? It seems difficult to explain why they pretend to be married if they are not. Conversely, if they are married and pretend not to be, there are certain aspects of the plot that do not make sense and prevent us from approving of their playfulness and inventiveness as a long-married couple that has resorted to games and pretence to introduce excitement into an otherwise failing relationship. In either understanding, they do not appear to be an immediately likely couple, and it is certainly easier to sympathise with Elle and her situation being with the unbecoming, ungrateful, ponderous and pretentious when he attempts to explain his ideas, James.2Although, as a number reviewers noted, Shimell’s first-time clumsy acting and Binoche’s slightly mannered acting tends to even our sympathies out. See on this, Paul Wood, “Certified Copy,” London Review of Books, October 7, 2010, https://pugpig.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v32/n19/michael-wood/at-the-movies.

Figure 4: Elle applies lipstick and puts on earrings, making herself even more attractive. A still from the film Certified Copy, directed by ‛Abbās Kiyārustamī, 2010 (01:17:30).

In reviews upon the film’s release and in subsequent essays and commentaries, Certified Copy often received a less than positive response. The director, ‛Abbās Kiyārustamī, had previously directed the acclaimed Ta‛m-i gīlās (The Taste of Cherry, 1997) and Bād mā rā khāhad burd (The Wind Will Carry Us, 1999), amongst many others, and the sense of disappointment with his latest film was palpable. Lisa Nesselson wrote after its premiere at the Cannes Film Festival in May 2010 that “while the premise holds promise, the actual execution is painfully awkward, forced and contrived.”3Lisa Nesselson, “Certified Copy Review,” SBS What’s On, May 20, 2010, https://www.sbs.com.au/whats-on/article/certified-copy-review/gighrmr3a. Later, upon its general release, the Guardian’s film critic Peter Bradshaw described it as “persistently baffling, contrived, and often simply bizarre – a highbrow misfire of the most peculiar sort.”4Peter Bradshaw, “Review: Certified Copy,” The Guardian, September 3, 2010, https://www.theguardian.com/film/2010/sep/02/certified-copy-review. In more academic accounts too, the film was not spared criticism. Canadian English Professor Marcus Boon writes that “the movie is set up so didactically – it more or less begins with a ten minute lecture setting out the thesis of the writer’s book – that one is forced to assume that what follows… is also about copying.”5Marcus Boon, “On the Copies in Kiarostami’s Certified Copy,” Marcus Boon, April 27, 2011, https://marcusboon.com/on-the-copies-in-kiarostamis-certified-copy/. While Gönül Dönmez-Colin in her Women in the Cinemas of Iran and Turkey observes of the conversation between Elle and the lady serving her in the café: “Something seems to be missing in these conversations that are rather formulaic and anachronistic in the context of modern women.”6Gönül Dönmez-Colin, Women in the Cinemas of Iran and Turkey: As Images and as Image Makers (London: Routledge, 2019), 319. Perhaps as some kind of a justification for the film, then, commentators have pointed to a number of esteemed European arthouse precursors to Certified Copy, in which we can already see aspects of the film. Hajnal Király notes, along with any number of others, that the idea of a couple driving through scenic Italy while trying to work out the status of their relationship was already to be seen in Roberto Rossellini’s Journey to Italy (1954).7Hajnal Király, “World Cinema Goes to Italy. Abbas Kiarostami: Certified Copy (2010),” Acta Universitatis Sapientiae, Film and Media Studies 5 (2012): 58. Perhaps even more relevantly, Maryse Bray and Angès Calatayud point out that Alain Resnais’ Last Year at Marienbad (1961) features a plot in which a man insists to a woman that they have previously met and had an affair, while the woman for her part, baffled or bafflingly, declares that they have never met.8Maryse Bray and Agnès Calatayud, “The Truth about Lies: The Relationship between Fiction and Reality in Abbas Kiarostami’s ‘Certified Copy’,” New Readings 11 (2011): 96, https://doi.org/10.18573/newreadings.78. Altogether, these kinds of parallels with European arthouse classics are seen not only as part of Kiyārustamī’s general move to Europe – where he came to live and work after difficulties of making films in Iran – but also as indicative of how non-European directors now most profoundly continue the European arthouse tradition in the twenty-first century. As British art writer Paul O’Kane observes, “The aim of Certified Copy… [is] to show Europe to itself as seen by others, while challenging preconceived values and traditions in ways that offer Euro-American art the opportunity of extending its own possibilities.”9Paul O’Kane, “Only a Game?: Abbas Kiarostami’s Certified Copy,” Wasafiri 27, no. 1 (2012): 54-56, https://doi.org/10.1080/02690055.2012.636919.

Figure 5: A still from the film Last Year at Marienbad, directed by Alain Resnais, 1961.

Undoubtedly, the most intriguing attempt to somehow make sense of or justify Certified Copy is the thinking of it in terms of the American philosopher Stanley Cavell’s notion of the filmic genre of the “comedies of remarriage.”10See, for example, Aaron Cutler, “Certifying a Copy: An Interview with Abbas Kiarostami,” Cinéaste 36, no. 2 (2011): 12; Rex Butler, “Abbas Kiarostami: The Shock of the Real,” Angelaki 17, no. 4 (2012): 62, https://doi.org/10.1080/0969725X.2012.747330; and Mathew Abbott, “Certified Copy: The Comedy of Remarriage in an Age of Digital Reproducibility,” chap. 6 in Abbas Kiarostami and Film-Philosophy (Edinburgh University Press, 2016), 110-128. This is Cavell’s identification of a previously unnoticed twist in a number of beloved and often-watched Hollywood comedies of the 1930s and ’40s: the couples in them are not simply falling in love and getting married for the first time, but falling back in love and getting married again after previously separating or getting divorced. Thus, in Adam’s Rib (1949), a middle-aged couple, played by Katharine Hepburn and Spencer Tracy, reunite after originally commencing divorce proceedings. In an even more exaggerated version of this, in Philadelphia Story (1940), Hepburn and Cary Grant actually get remarried again in the last scene of the film at the same ceremony and in front of the same guests who were gathered to watch her marriage to another man. Cavell’s argument is that what this remarriage genre testifies to is the fact that in the modern world where traditional norms no longer unquestioningly apply – for example, women are far more empowered and have more agency than previously – such long-running social customs as marriage can no longer be assumed but must continuously be tested. (Cavell’s analogy is something like the Wittgensteinian conception of language, in which the meaning of words is not fixed but comes about through their use and negotiation in every conversation.11Stanley Cavell, Pursuits of Happiness: The Hollywood Comedy of Remarriage (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1981), 9-14, 74-78, 271. For an essay exploring the connection between Wittgenstein and Cavell’s comedies of remarriage, see David Macarthur, “What Goes without Seeing: Marriage, Sex and the Ordinary in The Awful Truth,” Film-Philosophy 18 (2014): 92-109.) Thus, when the characters in those remarriage comedies get remarried, it is precisely to re-establish a convention that has previously failed, to try to find new forms of connection when nothing can any longer be taken for granted. Indeed, Cavell’s point is that all marriages today are effectively remarriages, that couples must continually renegotiate the terms of their relationship, which cannot be repeated unquestioningly.12Cavell writes, “Without the separation or divorce, the marriage would not be lawful… Marriage is always divorce, always entails rupture from something”, and “only those can genuinely marry who are already married,” see Cavell, Pursuits of Happiness, 103, 127.

Figure 6: A still from the film Philadelphia Story, directed by George Cukor, 1940.

Thus, although it is not perhaps an exact fit, we might understand James and Elle, if we can imagine them as separated or once married, seeking to reconceive the terms of their marriage by pretending to get together for the first time or to be still married. What we are watching is a couple that has either split up or is about to split up, starting over again by acting as though they were married or actually getting remarried (and in this regard that final scene in their original honeymoon suite with the church bells ringing is very revealing).13It is in this regard that we might understand James’s argument that the copy is just as good as the original, or that there is nothing wrong with people regarding a copy as an original. However, as the film goes on, it is Elle, initially sceptical about what James is saying, who seems more able to apply this idea to their marriage. On the other hand, James, who originally proposed the argument, appears more reluctant to apply it to his life and marriage. There have, of course, been any number of essays addressing the relationship between the original and the copy in Certified Copy. Two notable examples include: Zina Giannopoulou, “‘Original Copy’: Inverting Platonism in Abbas Kiarostami’s Certified Copy,” Offscreen 27, no. 8-10 (2023): 1-13; and Marco Dalla Gassa, “Certified Copy: The Thin Line between Original and Original,” in Borders: Itineraries on the Edges of Iran, ed. Stefano Pellò (Venice: Università Ca’Foscari, 2016), 333-352. Of course, this meditation on both the failure of marriage and the necessity to reinvent it is ironic given James and Elle’s presence at the church where couples are getting married, and these couples asking them to pose in their wedding photographs, given their status as an apparently happily married long-term couple. Indeed, Mathew Abbott in his book Abbas Kiarostami and Film-Philosophy makes the further point that the very undecidability of what we are watching, whether it is two unmarried people pretending to be married or a married couple pretending to be unmarried, is the very logic of Cavell’s comedies of remarriage, in which the meaning and status of marriage are never fixed, never determined, always in doubt and dispute. Abbott writes, “The film is so reflexive, so aware of itself as a film, that it puts Cavell’s account into question – and not simply by challenging any particular generic ascription.”14Abbott, “Certified Copy,” 112. Indeed, Abbott comments on the difficulty of determining whether Certified Copy is a comedy of remarriage – James and Elle break up and make up several times throughout the film, and at the end it is unclear whether they have got back together – although this undecidability is also true of a number of the original comedies of remarriage. Although not all of the narrative inconsistencies of the film are resolved – we still cannot understand why James does not recognise his son at the beginning of the film if he is his, or why Elle does not tell him the boy is his son if indeed he is, and in fact children altogether were not part of Cavell’s original conception of the genre – this is perhaps part of the uncertainty of modern marriage, in response to which the remarriage genre arises.

Figure 7: Elle’s son. A still from the film Certified Copy, directed by ‛Abbās Kiyārustamī, 2010 (00:11:14).

There have been any number of essays on how we might understand the genre of the comedy of remarriage continuing on into the present beyond its original moment in Hollywood in the 1930s and ’40s, including those by Cavell himself.15See Stanley Cavell, Cities of Words: Pedagogical Letters on a Register of Moral Life (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2004); and Rex Butler, “An ‘Exchange’ with Stanley Cavell,” Senses of Cinema, 13 (April 2001), https://www.sensesofcinema.com/2001/film-critics/cavell/. (Again, if we follow the argument that it is significant for a non-European director like Kiyārustamī to be seen as continuing the European arthouse heritage, it is equally significant for a non-Hollywood director like him to be understood as continuing the Hollywood genre of the comedy of remarriage.) But if we were to make an unexpected connection to Certified Copy, and one that particularly exhibits the radical undecidability of its couple’s marital status at any moment, or at least its radical reversibility, it would be Daniel Kwan and Daniel Scheinert’s Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022), which is also, among all of the other things it is, an updated version of the comedy of remarriage.16See, for example, Austin Kang, “Balancing Multiple Worlds: The Multiverse and the Fractured Asian American Experience in Everything Everywhere All at Once” (MA thesis, Chapman University, 2023), 45. In Everything Everywhere All at Once, a Chinese-American couple living in California repeatedly get married and divorced according to which multiverse they are in in a science-fiction time-travel story. Even the apparent resolution of the story, which we take to be a restoration of normal reality, and in which the couple is apparently happily reconciled, can be understood to be only another possible reality. As a number of commentators have pointed out, Certified Copy similarly lacks any overall framing device, by which we could definitively judge the truth of what we see. A copy of the Italian translation of James’s book, Copia Conforme, sitting on the desk behind which he will talk and speaking of the indiscernibility between the original and the copy, serves as the credits to the film, suggesting that there will be no external, authoritative directorial voice telling us how to understand what we will see. The daring aspect of Certified Copy is that nowhere does Kiyārustamī indicate the true status of the couple we follow throughout the film, and no matter which way we decide, there are irreconcilable inconsistencies. Yet it must be one of two scenarios (we always do live within one particular universe): either the couple have just met and pretend to others and themselves that they are married, or they are already married but pretend at the beginning and at various points throughout the film that they are not, both to themselves and sometimes to others.

The script by translator Ma‛sūmah Lāhījī – necessary because the two main characters speak in French, Italian, and English – is based on an original scenario by Kiyārustamī. But what, we might ask, originally drew Kiyārustamī to this story of a couple either pretending or not pretending to be married? If we were looking for something similar in another of Kiyārustamī’s films we might perhaps think of his Zīr-i dirakhtān-i zaytūn (Through the Olive Trees, 1994), in which the actor playing the lover of a woman character in a film actually falls in love with the actress playing that character, but because she refuses to speak to him off set he can only declare his love for her using the words of the film. After the film has been shot, we watch him chasing after her through a grove of olive trees to propose marriage, but we never discover the results of his pursuit. (Through the Olive Trees is based on an incident that occurred during the shoot of Kiyārustamī’s earlier Zindagī va dīgar hīch (Life and Nothing More, 1992), where something like this actually occurred.17Kiyārustamī will speak of this aspect of the making of Through the Olive Trees in “Abbas Kiarostami by Akram Zaatari,” in Abbas Kiarostami: Interviews, ed. Monika Raesch (Jackson, Miss.: University Press of Mississippi, 2023), 11-14.) In an obvious way, what Through the Olive Trees demonstrates is that love is not natural but artificial, always taking place, as it were, on a film set or its equivalent. It is inherently theatrical, and those conventions that apparently inhibit it in fact make it possible. The woman only loved the man while they were on set, and the man only had the right words to make her fall in love with him when he was reciting a script. (There is a whole line of other Kiyārustamī films that likewise demonstrate the crossing-over between art and life, the actor and their role, the film and its audience. To take just one example: in Shīrīn (Shirin, 2008), we see not the film based on a famous twelfth-century Persian love poem Khusraw and Shīrīn that Kiyārustamī apparently made, but only a series of women’s faces watching the film, accompanied by its soundtrack. Thus, when a happy moment occurs in the film, we see the women smile, when a sad moment occurs, we see them cry.) If the couple in Certified Copy fall in love again, it is only by acting that they are in love, whether it is a first date and they are pretending to be married, or they are married and are pretending not to be. We can only fall in love for the first time by pretending it has all been written for us, as though we only have to recite our lines, and we can stay in love only by pretending not to be married and going out on a first date. The original, as James says but does not enact, and Elle does not believe but behaves as though it is true, is only a copy; indeed, it is only a copy of a copy. It becomes original only by becoming a certified copy, that is, a copy that people retrospectively treat as original.

Figure 8: James and Elle, a still from the film Certified Copy, directed by ‛Abbās Kiyārustamī, 2010, (01:33:38).

Cite this article

Certified Copy (2010) is the first dramatic feature film Abbas Kiarostami made outside of Iran and the first character-based fiction since Ten (2002). It stars the well-known French actress Juliette Binoche – it is said that her positive reaction to Kiarostami telling her an early version of the story led to him making the film – and the first-time actor opera singer William Shimell – Kiarostami had earlier directed him playing Don Alfonso in a production of Mozart’s Così fan tutte. (And there are a number of intriguing resemblances between Certified Copy and Così fan tutte.) The plot of Certified Copy has engaged and puzzled both critics and the general public continuously since the release of the film. It features a couple – it seems – who, while meeting for a short holiday in Tuscany, pretend that they are not married and are going on a first date. Or it could be a couple who are separated getting back together again. Or it could be a couple going out on a first date pretending at various points that they are married. Kiarostami keeps all of these options open as we watch the film, and at no point is the enigma resolved. In this Certified Copy, as befits its name, offers a profound meditation on what is genuine and what is fictitious in both marriage and human relationships more generally. Indeed, following the arguments of the character played by Shimell, who is meant to be something of an expert on these matters, it is arguable that the fictive and the genuine cannot be entirely separated, that we, like the actor on the stage, can only truly know what we want through a kind of performance. In this, Certified Copy offers a reflection on much of Kiarostami’s previous work, which also addresses in various ways the inseparability of the original and the copy.