Circumventing Censorship in Iranian Cinema: On Unruled Paper and What Time Is It in Your World?

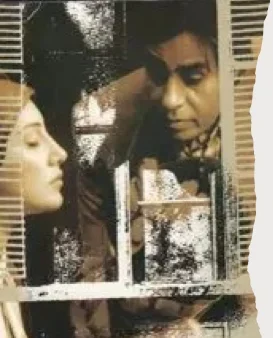

Figure 1: Poster from the films Kāghaz-i bī’khat (Unruled Paper, 2002) and Dar dunyā-yi tu sā‛at chand ast (What Time Is It in Your World?, 2014), directed by Nāsir Taqvā’ī.

Introduction

This paper examines the concept of censorship, its historical evolution, and its current practice in Iran, highlighting its role as a mechanism for controlling expression and maintaining power. Tracing the ongoing conflict between authority and creative freedom from the persecution of Socrates in ancient Greece to modern-day Iran, the study emphasizes how censorship shapes media and daily life. Iranian filmmakers like Nāsir Taqvā’ī and Safī Yazdāniyān navigate stringent censorship by employing visual metaphors and subtle storytelling, illustrating how art can subvert restrictions.

I have selected the films Unruled Paper and What Time Is It in Your World? as they represent two distinct subjects. The first engages with political and social issues, while the second explores romantic and poetic themes. Despite navigating different domains, both films grapple with the pervasive impact of censorship.

Building on Kierkegaard’s philosophy of indirect communication, the paper argues that art’s capacity to convey truths indirectly is particularly potent in censored environments. Kierkegaard believed that art guides individuals toward self-discovery rather than directly imparting knowledge, a concept that resonates in societies where direct expression is suppressed. The study categorizes three key ways visual art serves as a tool for circumventing censorship:

Silent Language: Visual art communicates significant ideas and emotions that cannot be explicitly stated, evoking deeper reflections and feelings that words may fail to capture.

Active Role in Narrative: The integration of visual art into storytelling transforms it into a dynamic element that merges character and artwork, making it central to the narrative and enhancing audience engagement.

Dialogue Between Artworks: The interaction among paintings creates an ongoing narrative that influences viewers’ perceptions, inviting them to connect with the film on a more abstract level and perceive meanings beyond the surface.

This study highlights the paradox of censorship: while intended to suppress, it often enhances creativity, pushing artists toward innovative and abstract forms of expression. Through the lens of Kierkegaard’s ideas, the paper demonstrates that art under censorship does not merely survive but thrives, transforming limitations into opportunities for deeper reflection and engagement. Ultimately, it affirms the enduring power of art as a vehicle for exploring complex truths, resisting oppression, and fostering personal and societal discovery.

The methodology of this paper combines theoretical analysis, film case studies, and cross-cultural comparisons to explore how visual art, particularly film, circumvents censorship in Iran. It begins by defining censorship and framing the discussion through Kierkegaard’s philosophy of indirect communication, highlighting how art conveys truths subtly. The paper examines two films, Unruled Paper and What Time Is It in Your World? to analyze how visual metaphors and symbolism bypass censorship. Additionally, it compares Iran’s censorship practices with those of other totalitarian regimes, like China and Russia, to highlight the broader global context of artistic suppression and creativity.

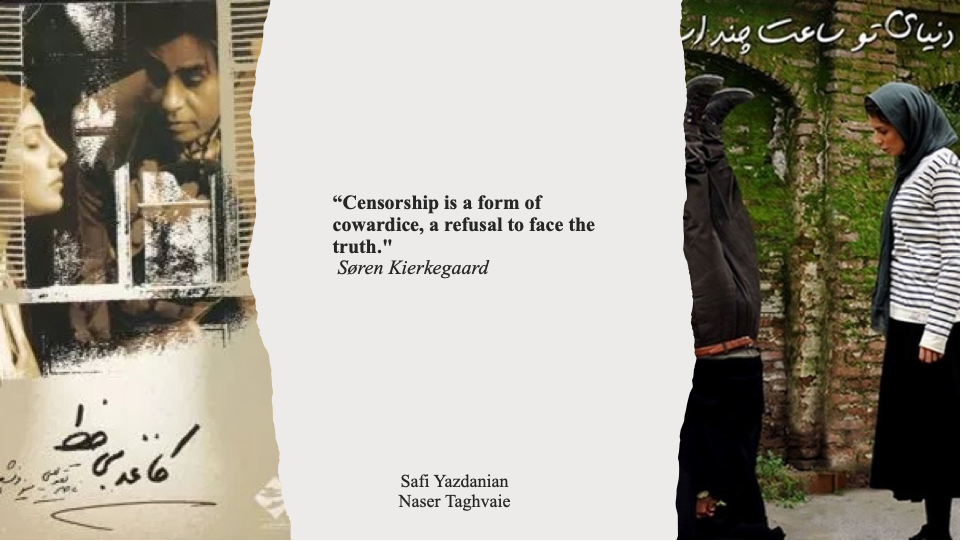

Figure 2: Mary Cassatt at the Louvre, by Edgar Degas

Understanding Censorship: A Definition and Its Practice in Iran

According to the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU),1The American Civil Liberties Union is an American nonprofit human rights organization founded in 1920. The organization strives “to defend and preserve the individual rights and liberties guaranteed to every person in this country by the Constitution and laws of the United States.” censorship is defined as: “The suppression of words, images, or ideas that are “offensive,” happens whenever some people succeed in imposing their personal political or moral values on others. Censorship can be carried out by the government as well as private pressure groups. Censorship by the government is unconstitutional.”2“What Is Censorship?” ACLU, August 30, 2006, accessed January 8, 2025, https://www.aclu.org/documents/what-censorship.

The root of censorship goes back to 399 B.C.E. Socrates, the philosopher of the time, was accused of impiety and corrupting the youth (Phaedo).3Plato, Apology, trans. G.M.A. Grube (Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company, 2000), 24b-25c. Although Socrates was killed so his ideas could be exterminated, we know of no other philosophers of his time more than him as it was the beginning of the dissemination of his ideas thanks to his student Plato. Censorship has been an issue since the dawn of human thought. Socrates was one of its first known victims, and Galileo Galilei was its most famous.4Dava Sobel, Galileo’s daughter: A Historical Memoir of Science, Faith, and Love (New York: Walker & Company, 1999). Throughout history, governments have controlled human expression, prioritizing and restricting potential creative outputs. The mind is a powerful realm with endless possibilities, yet every government has rules to maintain its power, requiring compliance from its citizens. Creativity, however, is the mind’s ability to transcend these boundaries and explore new possibilities. This innovation potential threatens established power, which is why it is often suppressed. Amputating an idea has always had a reverse relation with its dissemination. It sprouts, grows, and blossoms in many ways. The more dictator a country is, the tighter its frame is and, therefore, the stricter censorship it implies.

In the Islamic Republic of Iran, censorship has been a way to suppress people in every possible way, control them, and ultimately govern them. In Iran, many quotidian activities that people do every day in their lives have been long censored in all the media to shrink the legal abilities that are allowed to be seen in public to its lowest possible level. In this situation, most of the concepts would be abstract rather than concrete. Take the example of hugging (all three forms of the action, the written, the showing, and the verbal ways), which is banned on screen. This abstract can be delivered through different abstract arts that have autopsied the very idea of these concepts.

It is interesting that although visual art could always be a solution to represent what has always been missed on the screen, it had the least role in it. Analyzing the reason for that needs more research and, consequently, another article.

What if we use the already-made content and feelings to develop an image that should be censored in the media? Are these representing the same idea every time and in every context they are being used? Or, in specific realms of design and dialogues, do they act as mediators to extract the targeted concept? Do they help to bring out more, or do they repeatedly go on?

Visual Art as a Catalyst for Creative Freedom

These films, made in 2002, were produced when Iran was facing simultaneously both cultural growth and inner suppression of the intellectuals. Iran’s film industry continued to receive significant international acclaim. Filmmakers like ʿAbbās Kiyārustamī, Majīd Majīdī, Jaʿfar Panāhī, and Muhsin Makhmalbāf were celebrated for their works.5Geoff Andrew, “The New Iranian Cinema: A Conversation with Abbas Kiarostami,” Senses of Cinema 20 (June 2002), https://www.sensesofcinema.com/2002/feature-articles/new_iranian/. Filmmakers often had to navigate strict censorship rules imposed by the Iranian government. Topics related to politics, religion, and gender were particularly sensitive. Despite these restrictions, many directors found creative ways to address social issues and critique the status quo subtly.

Art has always been a medium for discovery. From Plato to the present, this role has been recognized, whether by those who sought to harness its power for good or those who wished to suppress it. The core of the matter has always been art’s profound influence. Visual art, particularly contemporary art, is an indirect form of communication. It expresses emotions, unexplored scenes, and the untrodden paths of philosophy and science in ways that remain unstandardized and, therefore, undiscovered. Visual art doesn’t just communicate what words cannot; it engages through other modes like seeing, associating, and feeling, creating a silent dialogue that reaches deeper parts of the mind and memory. This interaction creates a parallel understanding as if entering another dimension beyond the familiar three-width, length, and depth formed through the interplay of these dimensions. This aligns with Kierkegaard’s belief that art does not teach us truths directly but rather guides us toward our own discoveries, which are beneficial rather than demerits.6Antony Aumann, “Kierkegaard on the Value of Art: An Indirect Method of Communication,” In The Kierkegaardian Mind, ed. Adam Buben, Eleanor Helms, and Patrick Stokes (London: Routledge, 2019), 166-76. Socrates’s metaphor of midwifery, or maieutic, illustrates the role of a teacher as one who helps learners ‘give birth’ to their own knowledge, much like a midwife assists in delivering a child. Rather than directly imparting information, the maieutic teacher guides learners to discover lessons independently. This approach allows us to focus on overlooked considerations and reshape our understanding of the world in ways we might not have conceived independently.7Plato, Theaetetus, trans. M.J. Levett, revised by Myles Burnyeat, In Plato: Complete Works, ed. John M. Cooper (Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing, 1997), 157–234.

This piece explores the Iranian film industry in 2002, a period marked by both cultural growth and the suppression of intellectuals. Despite facing stringent censorship, filmmakers like ʿAbbās Kiyārustamī and Jaʿfar Panāhī received international acclaim by subtly addressing sensitive social issues. This context underscores the broader role of art as a medium for discovery and communication. Contemporary visual art serves as an indirect form of communication that transcends verbal expression, engaging with emotions and philosophical ideas in ways that words often cannot. This perspective aligns with Kierkegaard’s belief that art does not provide direct truths but guides us toward personal discoveries. Furthermore, Socrates’s concept of maieutic-where teaching is seen as helping learners ‘give birth’ to their own knowledge-emphasizes the importance of fostering independent thought and deeper understanding. Through this lens, art and teaching both emerge as powerful tools for exploring and understanding the complexities of human experience.

Unruled Paper

Amidst the strict censorship of the time, Nāsir Taqvā’ī produced a film in 2002, that encouraging women to understand themselves and pursue their dreams in the modern world. In the harrowing context of the chain murders of authors in Iran during the 1990s, making a film about a woman striving to become an author was akin to “biting the bullet,” which he did with notable courage.

In Unruled Paper, Ruyā, mother of two children, tries to follow her dream of becoming a writer, while her life and relationship with her shady architect husband Jahān, gets into some serious drama, which leads to the question of whether everything is really what it seems to be.”8“Kaghaz-e Bikhat,” IMDb, accessed August 7, 2024. https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0317794/.

Taqvā’ī masterfully incorporates visual art throughout the film, much of which unfolds in a confined apartment setting, to convey nuanced messages about the complexities of modern womanhood. The paintings and sculptures serve a dual purpose. First, they communicate what cannot be explicitly stated or the ideas that, though significant, would lose their impact if merely spoken. These artworks act as a silent language, evoking emotions and thoughts that words might not fully capture.

Nāsir Taqvā’ī skillfully integrates these visual elements to deepen the audience’s engagement, drawing viewers into a more intimate connection with the characters and the narrative. Instead of remaining passive, the audience is encouraged to reflect on the subtle messages the art conveys, long after the film ends. Colors, lines, and forms from the paintings linger in the viewers’ minds, provoking a journey into deeper, often uncharted, layers of thought.

The second aspect of how visual art functions in the film is its dialogue with itself. The paintings not only speak to the audience but also interact with one another, creating an ongoing narrative that quietly influences the viewer’s perception. This interaction between artworks evokes a metaphorical “fourth dimension”9Albert Einstein, Relativity: The Special and General Theory (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1920), 20. of engagement, inviting viewers to perceive beyond the conventional cinematic experience and connect with the film more abstractly.

The screenshots from Unruled Paper, paired with descriptions of each scene and artwork, effectively highlight the dual roles that visual art plays in Taqvā’ī’s film. These elements help clarify how the artwork both communicates unspeakable ideas and engages in a silent dialogue with itself, elevating the viewer’s experience beyond mere observation. Through this approach, Taqvā’ī’s use of visual elements becomes an integral part of the storytelling, allowing the art to subtly influence the narrative and engage the audience on a more profound level.

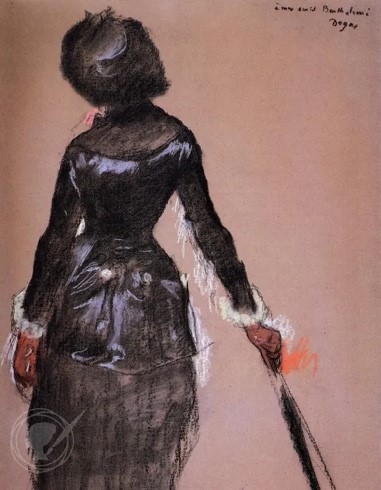

Figure 3: Screenshot from the film Unruled Paper, directed by Nāsir Taqvā’ī (Tehran, 2002).

The painting on the wall features a unique composition in which a single plant grows from two distinct containers: a traditional clay flowerpot and a repurposed tin of cooking oil, a familiar household item in many Iranian kitchens during that period. This juxtaposition of the pots invites reflection on the transformation and resilience embedded in everyday objects.

The clay pot represents the conventional, unchanging vessel, while the tin, having served its original purpose, has been given new life as a plant holder. This transformation symbolizes the adaptation and recycling of materials, a narrative of renewal and reinvention. The fact that the same plant thrives in both pots emphasizes the continuity of life, regardless of the vessel, underscoring themes of resourcefulness and the blending of tradition with modernity.

The painting speaks to a broader cultural practice of reusing objects, highlighting the beauty and potential in the ordinary. It captures the quiet, often overlooked poetry of domestic life, where even a simple tin can find a second purpose, nurturing growth and sustaining life. The artwork resonates with the idea of resilience, where the past and present coalesce to create something enduring and meaningful.

Figure 4: Screenshot from the film Unruled Paper, directed by Nāsir Taqvā’ī (Tehran, 2002).

The image shows a character ironing while facing a painting of a distorted figure who is also engaged in ironing. The abstract nature of the form-seemingly human yet distorted-reflects a struggle with inner turmoil or a feeling of deep, unspoken sorrow. The muted, almost washed-out palette intensifies the feeling of desolation as if the figure is trapped within its own despair. The painting captures the figure in a melancholic state, its posture slumped and weary. This parallel between the real and the painted figure highlights the emotional weight of the mundane task. The distortion in the painting emphasizes the fatigue and burden often associated with repetitive, everyday chores. The scene blurs the line between the character and the painting, creating a quiet reflection of the exhaustion and monotony embedded in routine activities. This piece, through its stark minimalism and distorted anatomy, seems to channel a silent scream, a visual echo of the alienation and helplessness often felt in the face of overwhelming emotional or existential crises. The viewer is drawn into this void, left to confront the unease and introspection the painting demands.

Figure 5: Screenshot from the film Unruled Paper, directed by Nāsir Taqvā’ī (Tehran, 2002).

This is the scene I admire in Nāsir Taqvā’ī’s work: Jahān is bowing to find something, and the frame is composed to show him before a traditional statue, likely of a skilled woman with many hands, balancing everything she carries above her head—symbolizing the burden of managing multiple aspects of life. To his right, a modern painting features a red flower, newly placed in a common household object—not a vase, but a repurposed Coke bottle, transforming it from an everyday item into something that not only serves a purpose but also adds beauty and function. The room, bathed in natural light, harmoniously blends the traditional presence of the statue with contemporary artwork, creating a striking contrast that enhances the scene’s visual and symbolic depth.

Figure 6: Screenshot from the film Unruled Paper, directed by Nāsir Taqvā’ī (Tehran, 2002).

The statue represents a multi-armed deity, a prevalent motif in Hindu iconography. The multiple arms symbolize the deity’s omnipotence, with each arm often holding different objects that represent various aspects of life or cosmic principles. In Hinduism, multi-armed deities signify their ability to perform numerous tasks simultaneously, reflecting their vast powers. For example, the goddess Durga is frequently depicted with multiple arms, each holding a weapon given by different gods to combat the buffalo demon Mahishasura. Similarly, the god Vishnu, when shown with multiple arms, typically holds a conch, discus, mace, and lotus flower, each symbolizing different aspects of his divine attributes. This tradition of depicting deities with multiple arms dates to ancient Hindu art, particularly during the Gupta period (circa 4th to 6th century CE), when this artistic style became prominent, allowing worshippers to visually grasp the immense power and responsibilities of the deity.10NAME OF THE AUTHOR“Multi-Armed Deity in Hindu Iconography,” In The Art of Hinduism: Symbolism and Significance, ed. Jaya Sharma (New Delhi: Art Publications, 2023), 45-67.

Figure 7: Screenshot from the film Unruled Paper, directed by Nāsir Taqvā’ī (Tehran, 2002).

In this image, the woman sits at a kitchen table, deeply absorbed in her thoughts. The scene is intimate and quiet, yet it carries a weight of unspoken emotions. Her hands are clasped as if in prayer or contemplation, suggesting she is grappling with something profound, perhaps the complexities of her life, the burdens of her problems, or the elusive nature of her dreams. On the wall behind her hangs a striking portrait painted in dark, intense colors. The portrait’s expression is enigmatic, a mix of a smirk and sadness. The artist has obscured half of the face with heavy brushstrokes, making it partially hidden, much like the layers of the woman’s inner world that remain unspoken or suppressed. This obscured face mirrors the woman’s own experience, where societal expectations have buried parts of her true self, her aspirations, and her dreams beneath the surface. The interplay between the woman and the painting creates a dialogue within the image. The sharp, almost harsh colors of the portrait contrast with the softer, more muted tones of the kitchen, emphasizing the tension between the woman’s inner world and the external reality she faces. The painting reflects her inner turmoil, the conflicting emotions that swirl within her: half-dream, half-reality, half-visible, half-hidden. The setting, with its everyday objects and warm light juxtaposed against the dark tones of the painting, underscores the dichotomy between the ordinary and the profound in her life. This moment captures a deeply human experience: the struggle between the self that conforms to tradition and the self that dreams of breaking free.

Figure 8: Screenshot from the film Unruled Paper, directed by Nāsir Taqvā’ī (Tehran, 2002).

The painting appears to depict a man from whom a ladder is growing, symbolizing the idea that, in traditional societies, a man is often perceived as the “stairway” for a woman to achieve her ambitions, but within certain constraints. In the context of the film, this painting plays as a visual metaphor for the relationship between Jahān and Ruyā. Jahān represents a man who, due to his traditional upbringing in a patriarchal society, wants to be supportive but is limited by his ingrained beliefs. He encourages Ruyā to pursue her interest in writing by attending classes, but he still views domestic chores as her primary responsibility. This duality reflects Jahān’s internal conflict between his desire to support Ruyā’s aspirations and his inability to fully embrace the idea of a woman having a career independent of household duties. The displacement of the painting within the film is particularly symbolic. By moving the painting, especially placing it near the kitchen, the film visually emphasizes the role Jahān believes he plays in Ruyā’s life, he sees himself as the enabler of her success, though only within the limits he sets, shaped by his traditional views. The positioning of the painting in front of the kitchen might symbolize how he ties Ruyā’s success to her domestic role, suggesting that her achievements are only possible if she fulfills her duties as a homemaker. Overall, the painting and its replacement within the film show Jahān’s constrained support for Ruyā, reflecting the broader societal expectations and limitations placed on women.

Figure 9: Screenshot from the film Unruled Paper, directed by Nāsir Taqvā’ī (Tehran, 2002).

In the image Jahān is depicted in a workspace, deeply engrossed in reading or working on something. The setting is simple yet telling, with a lamp providing focused light, and a statue of a thinking reminiscent of Rodin’s famous “The Thinker”, prominently displayed on the desk. The presence of the “thinking man” statue is significant in how it reflects Jahān’s character. The statue symbolizes contemplation, intellectual depth, and the traditional association of masculinity with rationality and thoughtfulness. In the context of the film, Jahān is portrayed as someone who is thoughtful and wants to be supportive of Ruyā, reflecting his desire to engage with and understand the world around him, much like the way the “thinking man” contemplates deeply. However, this association with deep thinking also ties into the limitations of his support. Just as the “thinking man” is frozen in a posture of contemplation, Jahān’s support is similarly constrained by his traditional mindset. His contemplation does not necessarily lead to action that breaks free from traditional expectations. He is thoughtful, but his thoughts are still grounded in a patriarchal framework where his role as the “thinking” or “supporting” man does not translate into a full acceptance of Ruyā’s independence or the possibility of her pursuing a career beyond the confines of traditional domestic roles. This statue, much like the ladder in the previous image, serves as a visual metaphor for Jahān’s internal state. While he embodies the traits of a traditional man who contemplates and supports, these traits are rooted in a conventional understanding of gender roles. His thinking is deep but not transformative, indicating how his support for Ruyā is ultimately limited by his inability to break away from the traditional expectations placed on both men and women in his society. The “thinking man” statue reflects Jahān’s intellectual side and his desire to support Ruyā, yet it also symbolizes the limitations of his support, which is bound by the traditional roles he has internalized. This creates a nuanced portrayal of a man who wants to be progressive but is hindered by the traditions that define him.

What Time Is It in Your World?

The film, directed by Safī Yazdāniyān, opens with Gulī (Hātamī) arriving at Tehran airport for her first visit to her hometown, Rasht, in two decades. Having lived in France, she seems to have built a stable life, as suggested by a phone conversation with her presumed partner, Antoine, about her sudden change of plans. A lively, semi-acoustic guitar soundtrack sets the tone for what feels like the start of a road trip. In many ways, What’s the Time in Your World? is just that a journey through memories. At the Rasht bus terminal, Gulī is greeted by the local frame-maker, Farhād (A. Musaffā), who helps her into a taxi. Although he clearly knows her (they share a peculiar window tap greeting), Gulī is bewildered, certain that she has never met Farhād before. He leaves her to go about her day, but soon he starts appearing wherever she goes -the market, her favorite diner, random streets. This triggers Gulī’s deeper investigation into her memory and identity.11“Dar donya ye to saat chand ast?,” IMDb, accessed September 9, 2024, https://www.imdb.com/title/tt4108894/. The film reflects on how Gulī, upon returning to Rasht after twenty years, is forced to confront her past through the memories that resurface. These memories are woven together by a painting she both receives and reenacts. Farhād gives her a replica of a painting of Mary Cassatt, originally painted by Edgar Degas in 1880. Safī Yazdāniyān once mentioned: “I was captivated by the idea of a woman’s face being hidden when viewing Edgar Degas’s paintings. We chose a version from his series “Mary Cassatt at the Louvre” with no background, allowing us to reconstruct the central figure of the woman in any space or environment.”12“Dar donya ye to saat chand ast?,” Farhangland, accessed September 22, 2024, https://shorturl.at/OUJ55. Mary Cassatt, an American painter, often modeled for the French artist Edgar Degas.

Throughout their careers, they mutually inspired and challenged each other, occasionally collaborating. Neither Degas nor Cassatt ever married, sparking speculation about their relationship.13Abigail Yoder, “The Artistic Friendship of Mary Cassatt and Edgar Degas,” Saint Louis Art Museum, April 20, 2017, accessed September 9, 2024, https://www.slam.org/blog/the-artistic-friendship-of-mary-cassatt-and-edgar-degas/. Degas perhaps offered the best description of their bond, stating, “There is someone who feels as I do.“14Achille Segard, Mary Cassatt: Un Peintre des enfants et des mères (Paris, 1913); quoted in Amanda T. Zehnder, “Forty Years of Artistic Exchange,” in Degas/Cassatt, ed. Kimberly A. Jones (Washington: National Gallery of Art, 2014), PAGE NUMBERS This feeling between these two, represented by the painting can also tell us more about a relationship which is led by Farhād, which is an inconvenient one. The recurring presence of this painting in the film extends beyond the canvas. Gulī cross-dresses in her late father’s suit, transforming the artwork into a liminal space where she attempts to reconnect with memories she cannot fully grasp -memories she cannot hug, touch, or kiss. In Iran, where censorship limits physical expression, the painting provides a way to bypass these constraints, expressing emotions that cannot be openly displayed.

In a film where time feels subjective, the use of visual art helps bridge the gap between the abstract concept of time and the audience’s understanding. The artwork serves as a visual metaphor, deepening the audience’s connection to the film’s temporal and emotional layers. The presentation of the paintings in this film functions as a deliberate strategy, enabling the director to transcend conventional depictions of time and memory, and instead engage in a more nuanced exploration of memory and the process of recollection. In Yazdāniyān’s film, physical spaces and objects serve as metaphors for different experiences of time, where time is not merely a chronological sequence but an emotional or mental journey. In this movie paintings, frames, and the curatorial of the paintings’ representation in their frames are mediums that approach time as a layered, non-linear construct. The way visual art is presented in this context contrasts with Nāsir Taqvā’ī’s subtle approach. In Taqvā’ī’s films, the artwork functions more like a foil character, influencing the flow of scenes indirectly and emphasizing themes without being the center of attention. It complements the narrative, playing a supportive yet essential role in shaping the film’s deeper meanings.

Here, however, the painting itself becomes central. Rather than subtly guiding the action from the margins, it takes on a more active, transformative role. The main character, Gulī, animates the artwork by physically embodying the posture of the portrait, bringing it to life and making the visual art an integral part of the narrative. This shift moves the painting from a background element to the forefront, merging the lines between character and art in a way that directly drives the story forward.

Figure 10: Screenshots from the film Mary Cassatt, directed by Safī Yazdāniyān (Tehran 2014).

The portrait depicts a solitary, abstract figure, whose anonymity conveys a universal, timeless quality. In the film, this ambiguity ties into the exploration of time and its impact on personal identity and memory. The figure may symbolize Gulī’s reflection on her own identity, distorted by time, emotions, and memories, much like how the audience is prompted to reconsider their relationship with time. Gulī’s act of holding the artwork suggests a connection to the past—revisiting a memory, relationship, or part of herself preserved within the portrait. Her gentle grasp reflects a longing or careful engagement with what the artwork represents. This gesture mirrors the film’s broader exploration of how individuals cling to past fragments as time progresses. Both Gulī and the viewer are invited to reflect on how they “hold” their own past—whether through objects, memories, or emotions. The framed portrait emphasizes art’s role as a tangible object that holds memory and meaning. While time in Yazdāniyān’s film is fluid and subjective, objects like artworks anchor it, providing physical representations of otherwise abstract experiences. The artwork becomes a container for memory, preserving moments that can be revisited through touch and reflection. This tactile interaction suggests that memory, like art, can be held, revisited, and reinterpreted over time.

In this fragmented, subjective portrayal of time, the hand touching the portrait symbolizes an attempt to reconnect with the past. Yet the frame’s boundaries and the figure’s distortion suggest the complexity of such efforts. Time blurs the edges of memory, making it difficult to hold onto any single version of the past. The distorted figure may signify the erosion of memory and identity over time. In What’s the Time in Your World?, characters experience time in disjointed, subjective ways. The ambiguity of the figure reflects the loss or fragmentation of personal identity as memories fade and identities shift. This figure could represent someone from Gulī’s past, a reflection of herself, or a symbol of a changing or lost identity. This carefully held portrait underscores the emotional and philosophical exploration of time in the film. The artwork bridges Gulī’s personal reflection and the film’s meditation on how individuals experience and interact with time. Through memory, identity, and the physical interaction with art, Yazdāniyān invites viewers to consider how they hold onto their past, how time distorts identity, and how art serves as a vessel for emotional and temporal experiences.

Figure 11: Screenshots from the film Mary Cassatt, directed by Safī Yazdāniyān (Tehran, 2014).

The use of frames throughout the film also can act as a metaphor for how people frame their own experiences of time. Just as the artwork is encased in a frame, memories and identities are shaped and contained within the frames we impose on them. The image in the painting may be distant or faded, much like how memories blur over time. The frame here becomes significant, acting as a boundary for the image it contains. The frame shop of Farhād in Rasht seems to preserve the memories of many as if freezing time to when Gulī was still in town. This boundary symbolizes the limitations people face when trying to understand or recall the past. No matter how much one may long to return to a specific moment, the frame of memory restricts how clearly or fully that time can be remembered. The artwork serves as a reminder that while the past can be revisited, one can never completely step outside the frames that shape their perception of time. This image also could be analyzed as an expression of time’s fluidity in a visual, curatorial sense. The film, which explores subjective perceptions of time, could be reflected in the visual density of this wall, where various artworks from different periods coexist in one space. This arrangement could symbolize how time in the film isn’t linear but layered, with past, present, and future interwoven, much like the artworks seen here.

The urban landscape painting at the bottom left is a frozen moment in time, evoking nostalgia or memories, while the abstract pieces might symbolize the timelessness of emotions or concepts that escape concrete representation. These contrasting styles reflect the film’s thematic exploration of how people experience and interpret time in different ways, some through memory, and some through abstraction. Each artwork can be seen as a temporal marker, a fixed point in a fluid continuum. The overlapping of paintings in this image could then signify how different moments or experiences blur together, much like how the characters in the film may experience overlapping memories or emotions that transcend a linear understanding of time. The frames themselves become crucial to this interpretation. Frames, like the structure of time, offer boundaries and constraints; they frame how we perceive an artwork just as time frames our perception of events. In the context of the film, frames can be seen as symbolic of the limitations placed on the characters’ perception of time—each character has their own “frame” of reference, but stepping beyond these boundaries could lead to new, expanded understandings of time, much like stepping outside of one artwork to observe the entire wall reveals the multiplicity of time periods and artistic styles present. This image may serve as a metaphor for how Yazdāniyān visualizes time in his film: fragmented, layered, and multi-directional. Just as this wall brings together artworks from different genres and eras, the film’s narrative structure may layer different times, places, and emotional states, offering the viewer a more complex, nonlinear understanding of the passage of time. The eclectic art collection might be seen as a visual parallel to the film’s fragmented storytelling or its exploration of how time is perceived differently by each individual, influenced by their memories, emotions, and subjective experiences. Just as the film challenges the viewer to consider time through different lenses—memory, experience, emotion—this wall of artworks invites a reflection on how different moments in time (and different artistic expressions) can coexist, creating a complex, multi-dimensional experience for the observer.

Overall, Gulī’s interaction with the artwork, particularly her holding of the portrait, underscores the film’s thematic focus on the intersection of memory and identity. The portrait’s abstract, solitary figure symbolizes the universal and timeless nature of personal reflection, inviting both Gulī and the viewer to reconsider their relationship with the past. The frame shop, and the act of framing itself, further represent how memories are constrained and shaped by the boundaries we impose on them. What Time Is It in Your World? challenges conventional depictions of time by layering visual and narrative elements that reflect the fragmented, subjective nature of human experience. The film uses art as a vessel to navigate the complexities of memory and identity, allowing the audience to engage with the temporal dimensions of the story in a deeply personal way. Through its innovative use of visual metaphors, the film not only portrays the erosion of memory over time but also invites viewers to reflect on how art can serve as a tangible connection to the past, reshaping our understanding of who we are across different moments in time.

How can contemporary art be more helpful in circumventing radical censorship?

Contemporary art, engaged with the present moment, acts as a liminal space that bridges the gap created by censorship, transforming abstract concepts into innovative modes of presentation. This space allows for the fluid negotiation of cultural and personal histories. Rather than merely producing new objects, contemporary art offers fresh perspectives, serving as a crucial medium for understanding and connection in a world where traditional communication often fails to capture the complexities of modern life.

Visual art, particularly contemporary, transcends language, expressing emotions and untold narratives in innovative ways. It communicates significant ideas and emotions that cannot be explicitly stated, evoking deeper reflections and feelings that words may fail to capture, effectively functioning as a silent language. Furthermore, the integration of visual art into storytelling transforms it into a dynamic element that merges character and artwork, making it central to the narrative and enhancing audience engagement, thereby highlighting its active role in narrative. Moreover, the interaction among paintings creates an ongoing narrative that influences viewers’ perceptions, inviting them to connect with the film on a more abstract level and perceive meanings beyond the surface, illustrating the dialogue between artworks. This engagement fosters a parallel dimension of understanding, allowing individuals to navigate the meanings concealed beyond censorship. Ultimately, contemporary art’s ability to create silent dialogues that penetrate memory and mind emphasizes its potential as a powerful tool for circumventing radical censorship, transforming limitations into opportunities for deeper reflection and engagement with complex truths.

Censorship as a Tool of Power in Totalitarian Regimes: China and Russia Controlling Cinema Through Suppression

Censorship in cinema is a common tactic employed by totalitarian regimes, exploiting its potential as a potent medium to shape public opinion and control societal narratives. As a powerful and almost magical tool, cinema can profoundly influence public perception and insight. Recognizing this, those in power strategically wield it to manipulate the minds of their citizens, thereby consolidating and maintaining their authority. Like Iran, in countries like China and Russia, this practice is marked by a combination of state-imposed restrictions, self-censorship by filmmakers, and informal regulatory pressures. Government authorities frequently ban films that critique the state, address politically sensitive issues, or challenge official narratives, ensuring that cinema aligns with the regime’s ideological goals.

In China, censorship is strict and systematically enforced, with films that critique the government, such as those dealing with issues like Tiananmen Square, Tibet, and Taiwan, routinely banned. Filmmakers often engage in self-censorship to avoid potential repercussions, altering narratives to comply with official guidelines. At the same time, there is a significant industry of censorship within the film industry itself, where filmmakers avoid controversial subjects even without explicit government orders.15Biltereyst, Daniel, and Roel Vande Winkel, eds. Silencing Cinema: Film Censorship Around the World (New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2013), PAGE NUMBERS

In Russia, the censorship landscape is shaped by both formal regulations and informal, self-imposed restrictions. Before the war in Ukraine, there was a clear but flexible boundary for filmmakers: it was unsafe to directly criticize the leadership, but one could still address issues relating to lower-level bureaucracy or broader social problems with caution. However, the onset of the war has led to a more unpredictable environment, where self-censorship has intensified, and even seemingly apolitical projects have faced significant delays or cancellations. Both China and Russia exemplify how totalitarian regimes use cinema as a tool for propaganda while stifling dissent through a combination of direct censorship, self-regulation, and fear of retribution, severely limiting the freedom of expression in the arts.16Ivan Filippov, “Censorship in Russian Cinema Isn’t What You Think,” The Moscow Times, October 2, 2023, accessed January 8, 2025, https://www.themoscowtimes.com/2023/10/02/censorship-in-russian-cinema-isnt-what-you-think-a82633. Russian directors, like Andrey Zvyagintsev (Leviathan), use metaphors to critique corruption and systemic problems, subtly pushing back against government narratives.

Directors in these countries often attempt to circumvent censorship through the use of metaphors, symbolism, and allegories, tools that have historically allowed censored subjects to be addressed indirectly. While some choose to voice their concerns openly using foreign platforms, others resist being silenced or forgotten under oppressive regimes. Despite the risks, they refuse to conform entirely. Through art and literature, these filmmakers find subtle ways to communicate with their audience, igniting a spark of awareness, however small or fleeting.

Conclusion

This paper has examined the multifaceted nature of censorship, tracing its historical lineage and highlighting its contemporary practice in Iran, particularly within visual and cinematic arts. Censorship, as articulated by the ACLU, represents more than just the suppression of words, images, or ideas; it embodies a broader imposition of power where political, moral, or personal values are enforced upon society by authorities. From the execution of Socrates in ancient Greece to the present- day restrictions faced by Iranian artists, censorship has long served as a means for those in power to shape and control public discourse, often at the expense of creativity, dissent, and independent thought. The persistence of censorship across history underscores a fundamental tension between authority and the human desire for freedom of expression. This dynamic is evident in Iran, where government-imposed censorship has permeated every aspect of life, particularly in media and art. Filmmakers like Nāsir Taqvā’ī and Safī Yazdāniyān have had to navigate these constraints by embedding subtle critiques and layered narratives within their works. Through the clever use of visual metaphors, symbols, and abstract representations, these artists circumvent overt censorship, providing audiences with alternative ways to engage with complex and often controversial subjects.

Visual art, particularly in its contemporary forms, operate as a powerful tool for exploring and communicating ideas that censorship seeks to suppress. This aligns with Kierkegaard’s philosophy, which emphasizes the indirect communication of truths and the importance of personal discovery. Kierkegaard argued that art does not convey truths directly but rather invites individuals into a process of introspection and self-discovery. This maieutic approach, akin to the Socratic method of guiding individuals to “give birth” to their own knowledge, allows art to function as a silent provocateur, engaging viewers in a dialogue that transcends the immediate constraints of language and censorship.

Kierkegaard’s concept of indirect communication is particularly relevant in the context of censorship, as it highlights how art can bypass direct confrontation and instead engage with audiences on a deeper, more personal level. In environments where open expression is curtailed, art’s capacity to evoke emotions, prompt reflection, and provoke thought becomes a critical avenue for exploring suppressed ideas. The layered, often ambiguous nature of visual art allows it to operate in a liminal space, one that resists definitive interpretation and thus escapes the rigid binaries of censored versus uncensored content.

In Iran, where censorship not only shapes what can be seen but also dictates how it is perceived, contemporary art functions as a vital medium for preserving the nuances of human experience. The visual dialogues embedded within films like Unruled Paper and What Time Is It in Your World? reveal the potential of art to transcend conventional boundaries and engage with themes of memory, identity, and resistance. These artworks do not merely represent forbidden concepts; they act as catalysts for broader reflections on freedom, personal agency, and the resilience of the human spirit.

Kierkegaard’s belief that art guides individuals toward self-discovery resonates deeply in the context of Iranian art under censorship. Just as Kierkegaard’s maieutic approach encourages learners to uncover their own truths, art under censorship compels viewers to look beyond the surface, engaging with the hidden layers of meaning that defy simplistic interpretation. This process of discovery mirrors the broader struggle against censorship itself: the more an idea is suppressed, the more it proliferates in unexpected and resilient forms.

The interplay between art and censorship illustrates a profound irony: while censorship aims to confine thought, it often spurs greater creativity and deeper engagement. In suppressing direct expression, censorship inadvertently pushes artists toward more innovative, abstract, and symbolic forms of communication, enriching the cultural landscape rather than diminishing it. This paradox highlights a critical truth: the mind’s capacity for creativity cannot be fully constrained, and art, in its myriad forms, continues to carve out spaces for free thought and expression.

Ultimately, censorship is a reminder of the enduring power struggle between authority and the creative impulse. Despite efforts to silence dissent, the human drive to explore, question, and express remain irrepressible. Through the lens of Kierkegaard’s philosophy, we see that art does not merely survive censorship; it thrives within it, transforming limitations into opportunities for deeper engagement and personal revelation. In this sense, art becomes more than a mode of communication, it is a testament to the unyielding nature of human creativity and the relentless pursuit of truth, even in the face of suppression.

Cite this article

This article examines how Iranian filmmakers navigate state censorship by embedding visual art and metaphor within cinematic narratives, focusing on Unruled Paper (2002) by Nāṣer Taqvā’ī and What Time Is It in Your World? (2014) by Safī Yazdāniyān. Drawing on Kierkegaard’s philosophy of indirect communication, the study argues that visual art functions as a silent yet subversive language, allowing artists to evoke censored ideas, explore complex truths, and foster introspection. Through detailed visual analysis, the paper identifies how artworks in film operate on three levels: as silent language, as active narrative agents, and as dialogic elements within the frame. The article situates these cinematic strategies within broader comparative contexts, such as China and Russia, and concludes that censorship, while intended to suppress, paradoxically drives innovation, transforming artistic constraint into a space of resistance, reflection, and resilience.