Asghar Farhadi: A Master of Moral and Aesthetic Ambiguity

Asghar Farhādī was born in 1972 in Humāyūnshahr, also known as Sidah (now called Khumaynīshahr), on the outskirts of Isfahan. He gravitated towards theater and film at an early age despite having no obvious family connection to the arts.1Tina Hassannia, Asghar Farhadi: Life and Cinema (Raleigh, NC: The Critical Press, 2014), 26. He started to write plays and short films at the age of ten and successfully applied, aged eleven, to the government-run Youth Cinema Center (Markaz-i Sīnimā-yi Javān) in Isfahan for support to realize his first screenplay, Rādiyū (Radio). Farhādī continued to make short fictional and documentary films during his teen years but there was little personal or family expectation that he would pursue a filmmaking career until his university entrance exam scores denied him entry to the medical track. The next year, he sat the arts entrance exam and finished eighth nationally. He enrolled at the University of Tehran’s Faculty of Fine Arts in 1991, where he was steered towards a theater concentration because of his past writing experience. Those years spent studying modern realist drama profoundly shaped both his work habits and style as a professional.

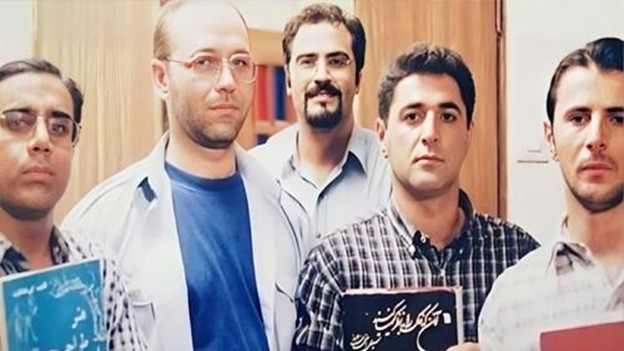

Among his earliest paid work was writing radio plays. During his time at the state broadcaster’s radio drama division, he enrolled in a master’s program in directing at Tarbīyyat Mudarris University in Tehran. By his own admission, his on-the-job training was more valuable than graduate school.2Asghar Farhādī and Esmāʿīl Mīhandūst, Rū dar rū bā Asghar Farhādī, New Edition. (Tehran: Nashr-i Rawnaq, 2016), 20-27. Farhādī soon received an invitation to write for television, first for short and interstitial programs and then for serials. His first major television writing job was for the Shāpūr Qarīb-directed Rūzigār-i javānī (Youthful Days), broadcast on the Tehran Network (Shabakah-i Tehran) in 1998 and 1999.3“Chihil sāl sirīyāl sāzī dar havālī-i tapahʹhā-yi Vanak,” Māhnāmah-yi Sīnimāyī-i Fīlm, no. 245 (December 11, 1999): 106. The series, about a group of university students from different corners of Iran living together in a Tehran rental, undoubtedly mirrored his own recent college experiences. Each episode focused on a single character’s problem that the group would help to solve but, in doing so, also revealed the kinds of personal dilemmas, relationships, and class tensions that characterized contemporary urban life, presaging the social realist themes that would later shape Farhādī’s film narratives. Youthful Days demonstrated Farhādī’s potential to connect with audiences, which encouraged the Tehran Network to give him the opportunity to write, produce, and direct his own series, Chashm bih rāh (Looking Forward, 1998).4“Chihil sāl siriyāl sāzī,” 98. Episodes were set in a maternity ward waiting room and followed the stories of families there—an idea that occurred to Farhādī during his first child’s birth.

Figure 1: A still from Rūzigār-i javānī (Youthful Days, 1998-99), Asghar Farhādī.

The creative inspiration behind his early television work highlights an enduring pattern in Farhādī’s writing process: moving from a single image conjured up or moment experienced in his own life to a fully-fledged story.5Hassannia, Asghar Farhadi, 22. After a number of other writing commitments for the Tehran Network and the programmers at national Channel Three (Shabakah-i Sih), Farhādī had a breakout hit with Dāstān-i yik shahr (Story of a City, 2000-2001), directing and writing the first two seasons. The series, featuring a young television crew who scour the city for stories to capture on video, also examined the challenges of big city life from a variety of class perspectives.6“Chihil sāl sirīyāl sāzī,” 102. A few of its segments never aired because of their controversial content. Bitter experiences with censors helped to push Farhādī towards cinema. Nevertheless, he has continued to face censorship-related issues in this new medium.7Hassannia, Asghar Farhadi, 11, 16-17.

Figure 2: A still from Dāstān-i yik shahr (Story of a City, 2000-2001). Asghar Farhādī, accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q5tGI5q2nFk (00:08:15)

Farhādī’s first film project was co-writing the screenplay for Irtifāʻ-i past (Low Heights, 2002), which became director Ibrāhīm Hātamī Kīyā’s biggest box office success to date. Low Heights represented a major departure for the director in terms of narrative themes, characterizations, and emotional tone.8For criticism of this narrative and stylistic turn, see Mojtaba Jibi, Sī sāl sīnimā-yi difāʻ-i muqaddas (1360-1390) (Tehran: Rūzigār-i Naw, 2016), 214-5. Previously, Hatami Kiya had operated exclusively within the narrative and stylistic conventions of the Cinema of Sacred Defense (Sīnimā-yi Difāʻ-i Muqaddas), a genre primarily concerned with martyrdom, self-sacrifice, and the “mystical” objectives of the Iran-Iraq War.9See Roxane Varzi, Warring Souls: Youth, Media, and Martyrdom in Post-Revolution Iran (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2006). Governmental and quasi-governmental organizations had long funded Sacred Defense productions,10See, for example, “Muʻarrifī-i nahādʹhā-yi sīnimā-yi jang va difāʻ-i muqaddas,” Film 165 (September 27, 1994): 67-70. due in part to their limited theatrical appeal. After the 1988 ceasefire, the collective project to capture on screen the war’s true nature did not end but instead increasingly explored postwar settings in which austere wartime values and the veterans who exemplified them existed uneasily in a society seemingly indifferent or openly hostile to both. Inspired by true events, Low Heights also concerns a war veteran, Qāsim (Hamīd Farrukhnizhād), but one who seeks material gain rather than transcendence by hijacking a plane and taking it abroad to claim asylum and make a fresh start. He boards a flight to Bandar Abbas along with his extended family, to whom he has falsely promised lucrative work and better life circumstances there. However, shortly after takeoff, he instructs the pilot at gunpoint to redirect the plane to Dubai. Two undercover security agents, themselves war veterans, and mutinous family members—most notably his mother-in-law and very pregnant wife—ultimately derail his plans. The final scene depicts the out of fuel plane crash-landing as his wife gives birth but the conflicting opinions of the passengers about where they have landed cast doubt for the audience about their survival. The film won critics’ and audience awards for best film at the 2001 Fajr Film Festival in Tehran, perhaps resonating with a jaded and weary “middle class” that fell outside of those social groups who by way of their sacrifice or opportunism had benefited morally or materially from the war.11For the excluded post-revolutionary “middle class,” see Pedram Partovi, “Martyrdom and the ‘Good Life’ in the Iranian Cinema of Sacred Defense,” Comparative Studies of South Asia Africa and the Middle East 28, no. 3 (2008): 529.

Figure 3: A still from Irtifāʻ-i past (Low Heights, 2002). Asghar Farhādī, accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iyj6Y4tP1cs (00:36:54)

Farhādī’s own family background links him to the urban, educated middle class,12Hassannia, Asghar Farhadi, 15. which had largely acquired its social status in the Pahlavi era and was less likely to support some of the apocalyptic and otherworldly aims of the Islamic Revolution and Iran-Iraq War.13On the apocalypticism of the Islamic Revolution and Iran-Iraq War, see Farhad Khosrokhavar, Suicide Bombers: Allah’s New Martyrs, trans. David Macey (London: Pluto Press, 2005), 70-83. In fact, critics and commentators have often described him as a filmmaker with a special interest in the “values and lifestyle” of the middle class that had historically found expression in popular melodramatic films.14Daniele Rugo, “Asghar Farhadi,” Third Text 30, no. 3–4 (2017): 181-3. His complex engagement with melodramatic modes also sets Farhādī apart from an earlier generation of internationally-known directors who had gained auteur status by explicitly rejecting melodrama as supposedly inauthentic and manipulative of audiences and instead focused on stark depictions of poverty among the rural and urban working classes in postrevolutionary Iran.15For Farhadi’s engagement with tropes from Iranian and Western melodramas, see Pedram Partovi, “The Salesman,” in Lexicon of Global Melodrama, ed. Heike Paul, Sarah Marak, Katharina Gerund, and Marius Henderson (Frankfurt: Transcript Verlag, 2021), 347-51. For the stylistic and narrative preferences of postrevolutionary art film directors, see Richard Tapper, “Introduction,” in The New Iranian Cinema: Politics, Representation and Identity, ed. Richard Tapper (London: I. B. Tauris, 2002), 1-25. Yet, film historians have also claimed that social realism was, even if uneasily, a component of middle class melodramas produced by the commercial film industry since the 1950s and Farhādī’s films have continued that tradition.16Taraneh Dadar, “Framing a Hybrid Tradition: Realism and Melodrama in About Elly,” in Melodrama in Contemporary Film and Television, ed. Michael Stewart (London: Palgrave, 2014), 224; and Saʿid ʿAqīqī, Rāzʹhā-yi judāyī: sīnimā-yi Asghar Farhādī (Tehran: Rawzanah, 2017), 12-13.

Early in his directorial career, Farhādī quite self-consciously adhered to the formula of postrevolutionary realist cinema, with its overwhelming focus on the most deprived classes and settings. His first two films, Raqs dar ghubār (Dancing in the Dust, 2003) and Shahr-i zībā (Beautiful City, 2004), both concern the moral and material dilemmas that spring from abject poverty. Even so, Farhādī’s flair for tortured personal relationships and their attendant emotions was also present in these titles. Dancing in the Dust follows the story of an immature young couple from a poor south Tehran neighborhood whose marriage unravels when scandalous rumors reach the groom, Nazar (Yūsif Khudāparast), about how the bride’s mother has had to make a living. However, unpaid debts keep him from paying the dowry and finalizing a divorce. Nazar seeks refuge from creditors in the back of a snake-catcher’s van but, upon discovery, asks his accidental companion to teach him the trade. The gruff old loner (Farāmarz Gharībīyān), much irritated by the brash young man’s presence, tries to run him off but is unsuccessful. Much of the film’s running time is devoted to Nazar’s contentious relationship with the snake-catcher, which both reveals and obscures aspects of the mysterious man’s past. The narrative technique of slowly parceling out information about key characters and, in the process, disturbing the audience’s moral judgments of them is one that Farhādī has come to use to great effect in nearly all his films. Ultimately, Nazar’s persistence brings the two together but also places him in danger. He succeeds in catching a snake but also suffers a bite on his finger. The snake-catcher saves his life by amputating the finger and rushes him to a hospital for reattachment. He sells his meager belongings to pay for the surgery only to have Nazar run off with the money, leaving the severed appendage behind. The final scene depicts Nazar paying his mother-in-law the dowry. Both plot and resolution underline narrative themes of shame, masculine virtue, and family honor rooted in female chastity, which stand in the way of individual characters’ ‘selfish’ desires and passions. Farhādī’s cinematic oeuvre has frequently drawn on such themes but so has homegrown melodrama since its beginnings.17Partovi, “The Salesman,” 348.

Figure 4: A‛lā’s visit with Fīrūzah to inquire about Akbar. Shahr-i zībā (Beautiful City, 2004), Asghar Farhādī, accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YCVlSKhGLDw (00:15:31)

Beautiful City likewise explores the stifling of young love by social circumstances and, more generally, the impossible moral dilemmas that material deprivation creates. The narrative revolves around the impending execution of recently come-of-age Akbar (Husayn Farzīzād), convicted of killing his girlfriend, presumably after parental disapproval of the match, in a murder-suicide pact gone wrong. A full and accurate portrayal of this tragic incident, like many key plot details in Farhādī’s films, remains inaccessible to the audience. His sister, Fīrūzah (Tarānah ʿAlīdūstī), and fellow inmate, Aʿlā (Bābak Ansārī), join forces to convince Dr. Rahmatī (Farāmarz Gharībīyān), the victim’s father, to forgive Akbar. In the process, love blooms between Fīrūzah and Aʿlā but its consummation is complicated by Fīrūzah’s (unconfirmed) marriage to a neighborhood shopkeeper and opium addict. The victim’s father is equally conflicted. While he has no interest in clemency, the execution would also perversely require him to pay blood money to Akbar’s kin according to Islamic law. Such a payment would make it impossible for his daughter by another marriage, who suffers from developmental difficulties, to receive much needed and delayed medical treatment. Farhādī provides no obvious resolution to these narrative threads, again in line with (Iranian) social realism’s longstanding conventions.18See, for instance, Farah Nayeri, “Iranian Cinema: What Happened in Between,” Sight and Sound 3, no. 12 (December 1993): 28. In fact, narrative irresolution or ambiguity has since become a hallmark of Farhādī’s cinema. The film neither ends with Akbar’s execution nor with Fīrūzah answering Aʿlā at her door. Farhādī even raises the possibility for viewers that Aʿlā will marry Dr. Rahmatī’s remaining daughter, stifling his feelings for Fīrūzah in exchange for Akbar’s life, but he does not confirm it. Interestingly, prerevolutionary social melodramas often employed such bittersweet endings, in which concepts of masculine virtue were affirmed through the personal sacrifice of the young, and often unlikely, hero for the sake of friendship or family.19Pedram Partovi, Popular Iranian Cinema before the Revolution: Family and Nation in Fīlmfārsī (New York: Routledge, 2017), esp. 103-25. Farhādī’s fondness for ambivalent narratives and characters speaks to his uncanny ability to straddle the two (often complementary) worlds of commercially-driven and art cinema.20For a discussion of Farhadi’s narrative restraint and contradictory characters, see Farhādī and Mīhandūst, Rū dar rū bā Asghar Farhādī, 55-8.

Figure 5: A still from Shahr-i zībā (Beautiful City, 2004). Asghar Farhādī, accessed via https://iranianfilmempire.wordpress.com/2017/10/18/the-beautiful-city-by-asghar-Farhādī-2004/

Still, Farhādī has rarely acknowledged in interviews his creative debt to a uniquely Iranian tradition of cinematic melodrama, even when incorporating explicit references to some of its most prominent examples—e.g., the diegetic use of music from M. ‛Alī Fardīn’s Sultān-i qalb’hā (King of Hearts, 1968) in Beautiful City. Critics for their part have especially stressed his early films’ debt to a postrevolutionary art and festival circuit cinema,21Hassannia, Asghar Farhadi, 14. not only because of the narrative choices Farhādī made but also the techniques he employed. The anti-heroes in Dancing in the Dust and Beautiful City were non-professional actors, following the casting practices of auteurs like ‘Abbās Kīyārustamī and Majīd Majīdī (casting non-professionals has also been commonly practiced in the Cinema of Sacred Defense). Likewise, Farhādī relied on simple set design, on-location shooting, and slow-paced, documentary-style editing. In fact, one of the co-writers of Dancing in the Dust had originally intended to make a documentary about the lives of snake-catchers before transforming the script with Farhādī’s help.22“Bīmārī yaʻnī bī-mārī,” Mahnāmah-yi Sīnimāyī-i Fīlm 310 (December 2003-January 2004): 90. Moreover, his own heavy or exclusive involvement in script development along with direction mirrored the predilections of then-established auteurs. While the screenplays were more fleshed out than the Iranian realist school’s bare-bones scripts, aspects of dialogue and acting were similarly worked out on the fly.23Hushang Golmakani, “Yik rūz-i bi-khusūs,” Mahnāmah-yi Sīnimāyī-i Fīlm 344 (March-April 2006): 136-7. However, these two films also bore influences from Farhādī’s television experiences in their ‘videographic’ look—namely minimalist shot framing, depthlessness, lack of wide-angle cinematography, and the heavy use of close-up medium shots.24Farhādī and Mīhandūst, Rū dar rū bā Asghar Farhādī, 64-66. Farhādī’s early films enjoyed some critical success, with Dancing in the Dust winning the best film award at Tehran’s annual Fajr Festival. However, they did not cultivate the audiences that he later became famous for, starting with Chahār shanbah sūrī (Fireworks Wednesday, 2006), in which he made a definitive turn towards middle class melodrama.

To be sure, Low Heights was an attempt at mixing melodrama with middle class concerns and similar plot themes were explored in television series like Tale of a City. These were initial engagements with a now well-established trope in Farhādī’s film narratives of the fragility of intimate relationships, with social, moral, or financial crises revealing the strains within and triggering a reckoning for the protagonists. In fact, a voyeuristic intrusion into characters’ most intimate thoughts and emotions, which in real life would otherwise be carefully hidden from public view, was part of the ‘entertainment’ for fans of Iranian melodramatic cinema from early on.25Partovi, Popular Iranian Cinema before the Revolution, 149. Fireworks Wednesday also concerned the shocking discovery of characters’ hidden lives. However, the facts (in part or whole) are foreshadowed throughout, highlighting another common narrative technique that Farhādī has employed.26Saʿid Qotbizadeh, “Kālbudʹshikāfī-i Ilī,” Mahnāmah-yi Sīnimāyī-i Film 396 (June-July 2009): 106. Farhādī directed the film but co-wrote it with Mani Haghighi, a fellow ‘next-generation’ writer-director who has also managed to successfully work across the boundary between art and commercially-driven cinema. The years between 2006 and 2009 marked a period in Farhādī’s career when he regularly collaborated with other directors as a writer or co-writer. He has since claimed sole responsibility for the script and direction of his productions, which perhaps betrays his mixed experiences during that phase. Fireworks Wednesday was in any case a very successful collaboration, winning the audience award at the Fajr Film Festival and enjoying a ten-week domestic box office run.

While this film marked a career shift for Farhādī in relying exclusively on professional actors for key roles, the cast included several carry-overs from previous productions in which he was involved. Most notably, Tarānah ʿAlīdūstī who played the young domestic Rūhī and has since worked with him on three other productions. Many critics have noted Farhādī’s reliance on a relatively small, semi-regular troupe of actors, a predilection which some have attributed to his theatrical training. His theatrical approach to filmmaking has included an extensive pre-production rehearsal schedule. Farhādī has claimed that his preference for working with the same actors helps to advance the dialogue writing process.27Golmakani, “Yik rūz-i bi-khusūs,” 136. Fireworks Wednesday was also the first time he teamed up with his long-time editor Hāyidah Safīyārī, who would break up the long takes that had characterized Farhādī’s earlier productions with faster pacing and jump cuts more in line with post-classical Hollywood cinema. According to Farhādī, the new editing style signaled a greater emphasis on characters’ emotions at the expense of cinematic realism.28Golmakani, “Yik rūz-i bi-khusūs,” 136. The film also employed a mise-en-scène different from and seemingly more theatrical than his earlier films; specifically cluttered and confined domestic spaces as the chief setting, with the strategic use of mirrors to redouble the chaotic atmosphere.29Golmakani, “Yikrūz-i bi-khusūs,” 142. Darbārah-yi Ilī (About Elly, 2009), Judāyī-i Nādir az Sīmīn (A Separation, 2011), Le Passé (The Past 2013), and Furūshandah (The Salesman, 2016) all incorporate domestic settings in various states of disarray that then serve as a venue for the protagonists’ moments of reckoning.

Figure 6: On Fireworks Wednesday night, Rūhī and Murtizā’s son are in Murtizā’s car. While the son sleeps peacefully, Rūhī anxiously watches the city’s fireworks and chaos. Chahār shanbah sūrī (Fireworks Wednesday, 2006), Asghar Farhādī, accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bMBMlTNtf9E (01:23:04)

In Fireworks Wednesday, Rūhī comes to clean the home of a young middle-class couple in the midst of redecoration right before the New Year’s holiday. She is immediately dragged into the middle of their domestic spat when she is asked by the wife Mozhdeh (Hedieh Tehrani) to spy on her husband Murtizā (Hamīd Farrukhnizhād) and neighbor Sīmīn (Pānti’ā Bahrām), whom she suspects are having an affair. In effect, Rūhī becomes the audience’s proxy for peeking voyeuristically into the private lives of the love triangle’s three legs. Ultimately, Rūhī denies an affair between Murtizā and Sīmīn in order to restore the domestic order and protect the reputation of Sīmīn, with whom she most sympathizes. Farhādī does not place his audience in a starkly drawn moral universe, with obvious protagonists and antagonists more common to the classical Hollywood(-style) melodrama. He instead employs a more nuanced morality familiar to domestic melodramas where irony and cynicism have thrived; thus, he avoids automatically demonizing the ‘homewrecker.’30For a discussion of moral ambiguity in prerevolutionary melodramas, see Partovi, Popular Iranian Cinema before the Revolution, esp. 62-84. The film concludes in a typically bittersweet fashion, establishing an uneasy détente between the couple after Sīmīn ends her relationship with Murtizā while Muzhdah remains doubtful about her husband’s fidelity. The only character seemingly changed by the day’s events is Rūhī, who is about to start her own married life carrying this painful secret. Indeed, characters telling and covering up lies becomes a recurrent plot thread in Farhādī’s melodramas.

Farhādī doubled down on the theme of duplicity and infidelity in his next directorial effort, About Elly, which was not only a smash hit at home but charmed foreign critics too, winning the Silver Bear Best Director award at the Berlin International Film Festival. The film takes as its subject three young couples who travel to the Caspian Sea coast for a vacation with another friend, Ahmad (Shahāb Husaynī), who has just arrived from Germany. The trip’s organizer, Sipīdah (Gulshīftah Farahānī) wants to find the recently divorced Ahmad a new beau and invites her daughter’s teacher, Elly (Tarānah ʿAlīdūstī) to come along, without informing either of the two about her motives. Elly, like Rūhī in Fireworks Wednesday, is suddenly thrown into an intimate middle-class milieu whose cheeky and presuming behavior towards her elicits visible discomfort and regret about agreeing to the trip. Sipīdah nevertheless plots to keep Elly from returning to Tehran by hiding her cellphone. Her lies and deceptions in turn have disastrous consequences, following a now well-established pattern in Farhādī’s work.

Figure 7: A still from Darbārah-yi Ilī (About Elly, 2009). Asghar Farhādī, accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=csfRfEI2uhk (00:51:21)

When Elly disappears after being left by the others to watch over the children playing on the beach, Sipīdah and her companions are whipped into a Hitchcockian frenzy to find her. The director predictably uses this incident to build tension between the remaining characters and uncover the more troubling aspects of their personalities and relationships. With the growing specter of Elly having drowned in the sea, the lies, infidelities, and recriminations pile up. Sipīdah reveals to her shaken friends how she had brought and kept Elly there under false pretenses, enraging her husband Amīr (Mānī Haqīqī) who suspects Sipīdah’s interest in Ahmad’s love life to be far from virtuous. However, as the couples search for clues about her disappearance, they learn of Elly’s own deceptions. Her mother didn’t know her true whereabouts that weekend; neither did her fiancé ‛Alī Rizā (Sābir Abar), who arrives to take part in the search. His revelation of their impending nuptials unsettles the group, who now come to realize Elly’s doubts about him and Sipīdah’s own superficial acquaintance with Elly. Collectively they assume the voyeur role, a character staple in Farhādī melodramas, discovering bit by bit more personal details about the mysterious Elly and in the process becoming party to her secrets. The friends thus conspire to hide from ‛Alī Rizā the reason why Elly was invited to spend the weekend there and why she accepted—not wanting to devastate him further. The seaside setting no longer serves as a calm respite from the turbulent workaday world but a deceit-filled quagmire engulfing them all, with Farhādī depicting their car sunk in the sand while the men fruitlessly seek to free it as a metaphor for their collective dilemma. Like Rūhī, the group is undoubtedly remade by their experiences. However, Farhādī once again offers no clues about where the characters’ new understanding of themselves or their relationships will take them. He leaves the audience to make its own judgments.

A Separation similarly eschews the kinds of narrative resolution familiar to the Hollywood-style melodrama. It nevertheless became Farhādī’s most successful film internationally, grossing nearly $18 million in overseas receipts, while drawing substantial audiences domestically. It also scored with critics around the globe, including multiple wins at the Fajr Festival and Iran’s first Oscar for best foreign film in 2012. The film begins with Sīmīn (Laylā Hātamī) seeking a divorce from her husband Nādir (Paymān Ma‛ādī). There is no infidelity driving a wedge between the two. Rather, filial obligation stands in the way of the couple’s relationship, in line with the melodramatic tradition’s privileging of familial over romantic love and other supposedly selfish impulses. Nādir’s father suffers from Alzheimer’s and needs round-the-clock care, while Sīmīn seeks to leave Iran and her family behind for a new, more hopeful life abroad. The main couple’s teenaged daughter Tirmah (Sārīnā Farhādī) is forced to navigate between these two divergent paths. The Islamic Republic’s legal apparatus has no answer to this ethical dilemma, only introducing further complications as Nādir accedes to divorce but not to his wife’s custody of their daughter. Farhādī ends the film with the court finalizing the divorce and Tirmah left to choose between her parents, but does not reveal her decision. In between these book-end scenes, A Separation (like Fireworks Wednesday and About Elly) pits its middle-class protagonists against working class analogues and, in the process, casts a harsh spotlight on their personal principles and most closely held beliefs.

Figure 8: Nādir and Sīmīn in court; Sīmīn complaining about her life situation to the judge. Judāyī-i Nādir az Sīmīn (A Separation, 2011), Asghar Farhādī, accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bMJ48FeaHxw&t=207s (00:03:28)

Nādir triggers the social and moral crisis in A Separation by hiring a domestic, Rāzīyah (Sārah Bayāt), to help care for his father now that Sīmīn, who has moved out, no longer can. Rāzīyah is concerned about the religious permissibility of such work, since it requires intimate contact with an incontinent old man, but her financial situation and a second child on the way rule out refusal. She nevertheless keeps the details of her job from her hotheaded husband, Hujjat (Shahāb Husaynī), who is unemployed and drowning in debt. Shortly after starting the job, she loses track of the old man who wanders into the street. She manages to chase him down but, during her pursuit, she is apparently hit by a car. True to form, Farhādī’s elliptical storytelling does not show his audience this key plot detail that colors all subsequent events. When Rāzīyah abandons her shift the next day for a doctor’s visit, presumably for the injuries incurred in the accident, she ties the old man to the bed only to have Nādir return home and find him in that condition. Furious, Nādir fires Rāzīyah for her lapse of judgment but she refuses to leave until she receives payment for her work. He accuses her of stealing money from his bedroom and denies any debt to her. Yet, the audience knows that Rāzīyah is innocent as Farhādī’s camera had earlier captured Sīmīn taking money from their bedroom stash. Starting with A Separation, Farhādī increasingly turned the camera into his voyeur character encountering the hidden actions, thoughts, and feelings of his cast.

Figure 9: Nādir takes his father to the bathroom and notices the bruises on his body. Judāyī-i Nādir az Sīmīn (A Separation, 2011), Asghar Farhādī, accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bMJ48FeaHxw&t=207s (00:46:02)

After Rāzīyah repeatedly asserts her innocence, Nādir violently shoves her out of the apartment and she falls down the stairs, another outside-the-camera-frame event. The fall leads to a court case in which he is accused of causing her miscarriage, or more specifically murdering her unborn child. After Nādir (falsely) denies knowledge of her pregnancy, Hujjat has a physical altercation with him. Nādir then files a counter-complaint against Hujjat for assault. Like in Beautiful City, Farhādī explores the complications of Islamic law and its often-perverse effects on the lives of ordinary Iranians. The dueling plaintiffs and their witnesses (including Tirmah) are forced to lie or withhold relevant information in order to survive the byzantine legal system.31Nacim Pak-Shiraz, “Truth, Lies, and Justice: The Fragmented Picture in Asghar Farhadi’s Films,” in Muslims in the Movies: A Global Anthology, ed. Kristian Petersen (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2021), 158-9. Farhādī’s missing scenes sow doubt in the audience’s mind about what actually caused the miscarriage, the car accident, or the fall, which explains if not excuses the main characters’ moral compromises and makes it harder to determine who is in the right. The director’s drip-feeding of the story, despite or because of its pacing, also contributes to the suspense that some critics have compared stylistically to Hitchcock’s cinema.32See, for example, Ann Hornaday, “Oscar-nominated ‘The Salesman’ melds Arthur Miller and Alfred Hitchcock,” Washington Post, February 2, 2017. This Hitchcockian element in Farhādī’s work perhaps took on greater prominence in The Salesman. Ultimately, the tension reaches its peak during a meeting at Rāzīyah and Hujjat’s home where Nādir is expected to pay blood money. However, when Rāzīyah is called on to swear on the Qur’an that he caused her miscarriage, she refuses and essentially returns the story back to its opening premise of divorce and custody. The film’s conclusion leaves the central characters dramatically changed by their experiences but their futures, in particular Tirmah’s, remain unknown.

Figure 10: A film still from Judāyī-i Nādir az Sīmīn (A Separation, 2011). Asghar Farhādī, accessed via https://mubi.com/en/notebook/posts/asghar-Farhādīs-a-separation

The Past and Todos lo saben (Everyone Knows, 2018) likewise traffic in the themes of “family crisis cinema” so common to Farhādī’s oeuvre but now in a non-Iranian setting, France and Spain respectively.33Kamran Ahmadgoli and Morteza Yazdanjoo, “The Politics of Cultural Diplomacy: The Case of Asghar Farhadi’s a Separation and the Salesman,” Quarterly Review of Film and Video 39, no. 3 (2022): 538. With About Elly, Farhādī began a collaboration with the French producer Alexander Mallet-Guy and Memento Films, which signed on as the film’s foreign distributor. Memento Films then expanded its partnership with The Past, which was Farhādī’s first foreign-financed film.34Celestino Deleyto, “Todos lo saben/Everybody knows (Asghar Farhadi, 2018),” Transnational Screens 10, no. 1 (2019): 73. Farhādī has followed a career progression established by previous Iranian auteurs who received funding from foreign production companies specializing in world cinema. In the past, foreign financing provided filmmakers an opportunity to escape censorship at home. However, such films rarely received screening permission in Iran, denying them their biggest potential audiences. Curiously, Farhādī has by and large avoided this dilemma, as only Everyone Knows did not receive screening permission. This exceptional record speaks to his ability to thread the nearly impossible needle of satisfying domestic censors as well as audiences and critics at home and abroad. To wit, Western critics have often claimed him as one of their own, arguing that his directorial style fits comfortably within a supposedly respectable melodramatic tradition represented by the work of directors like Paul Thomas Anderson, Michael Haneke, Mike Leigh, and Michelangelo Antonioni where

…nice, complacent middle-class people tootle along with their lives and then they’re sideswiped by a horrible event—mysterious, anonymous and malevolent—which shatters their calm and cracks open the carapace of their daily routine. It reveals the raw nerve of guilt and shame within.35Peter Bradshaw, “The Salesman Review—Asghar Farhadi’s Potent, Disquieting Oscar-winner,” The Guardian, (March 17, 2017), https://www.theguardian.com/film/2017/mar/17/the-salesman-review-asghar-farhadi-oscar-winner-iran

In The Past, it is a set of compromising emails and in Everyone Knows a kidnapping that brings to the surface secrets and past histories with devastating consequences for the central characters. In both films, the revelation of infidelity (but not its depiction) endangers marriages and lives. While the characters’ relationships in the aftermath of these tragic events remain a mystery, much like in Farhādī’s Persian-language films, a return to the status quo becomes impossible.

Only The Past includes an Iranian character, Ahmad (‛Alī Musaffā), and only then as an audience proxy and observer of the tragic love triangle involving his soon-to-be ex-wife, Marie (Bérénice Béjo). She wants a divorce from Ahmad so that she can begin a new life with Samīr (Tahar Rahim), whose wife is in a coma after a failed suicide attempt that the lovers soon learn may have been precipitated by the emails sent to her revealing the affair. The suicide attempt as the triggering incident is not shown. Similarly, the kidnapping in Everyone Knows, which reveals the victim’s true parentage and roils the marriages of erstwhile lovers Laura (Penélope Cruz) and Paco (Javier Bardem), occurs off-screen. The stories were clearly a continuation of a narrative trajectory that Farhādī had pursued in his Persian-language productions. Still, Farhādī chose France and Spain as settings for these two productions with the declared aim of making French and Spanish films.36Farhādī and Mīhandūst, Rū dar rū bā Asghar Farhādī, 261-3. He engaged in extensive audience testing during the script-writing process to ensure narrative authenticity.37Asghar Farhadi: Interviews, ed. Ehsan Khoshbakht and Drew Todd (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2023), 101. His attempt to reproduce plot, characters, relationships, and dialogue that rang true to European audiences speaks to what critics have claimed to be the simultaneously universal and national character of Farhādī’s films.38See, for example, Rahul Hamid, “Freedom and Its Discontents: An Interview with Asghar Farhadi,” Cineaste 37, no. 1 (Winter 2011): 42.

Figure 11: A film still from Le Passé (The Past, 2013), Asghar Farhādī, accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z2-_lt4kwXE&t=50s (00:01:25).

Farhādī’s oeuvre and its cross-over or international appeal may also serve as evidence of the maturation of Iranian cinema, at least from the perspective of non-Iranian or Western critics and audiences, in that these viewers are now prepared to see Iranians in different and more familiar contexts than they were before. Reviewers have highlighted the shift in Iranian imports that Farhādī’s films represent: from a more ‘exotic’ post-revolutionary art cinema focused on the so-called simple lives and everyday struggles of the poor to a cosmopolitan and worldly middle class whose social existence and moral dilemmas more closely resemble those of middle-class Western audiences.39See Nicholas Barber, “About Elly,” The Independent, (15 September, 2012), https://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/films/reviews/about-elly-asghar-farhadi-118-mins-12a-hope-springs-david-frankel-100-mins-12a-paranorman-chris-butler-93-mins-pg-8142177.html [2] Bradshaw, “The Salesman Review.” A useful comparison to the recent trajectory of Iranian cinema on the global film circuit may be Italian cinema in the 1950s and 1960s, when neorealist depictions of post-war poverty gave way to the more socially and morally nuanced films of the Italian urban middle class that had an extensive pre-war history. The reinvention of filmmakers like Fellini and the emergence of fresh talents like Antonioni propelled Italian cinema in simultaneously new and old directions.

The Salesman continued this cosmopolitan turn in Iranian cinema with its quite pointed engagement with modern Western realist theater, specifically Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman.

In fact, the middle-class couple in the film moonlight as Willy and Linda Loman in a Tehran production of the play. The play highlights the couple’s seemingly subversive cultural and social bent in an Islamic republic whose leadership has long cultivated an anti-Western politics. However, the play’s narrative themes also subtly insinuate themselves into the unfolding crisis that dominates their lives after the wife Ra‛nā (Tarānah ʿAlīdūstī) is sexually assaulted. Neither the husband ‛Imād (Shahāb Husaynī), nor the neighbors, nor the audience witness the attack and a badly shaken Ra‛nā remains less than forthcoming about what exactly happened. Consequently, the full details of the night’s events remain unknown. Nevertheless, the film emphasizes that gossip and rumors about the assault matter more than the facts. Like in Dancing in the Dust, prevailing social mores and the fear of “what will the neighbors say?” push ‛Imād to act in defense of his honor. As one reviewer argues, ‛Imād’s “irrational” reaction to the apparent assault brings into question his modern, worldly facade.40Bradshaw, “The Salesman Review.” Farhādī foreshadows the cracking of ‛Imād’s psyche, and the eventual crumbling of the couple’s relationship, with the cracking of glass and mirror frames in the opening scene when a (likely illegal) construction project next door undermines the foundations of their apartment building. Their relocation to another apartment previously inhabited by a prostitute sets the stage for the assault. Again, the film’s mise-en-scène works to reflect the chaotic mood of the film and its characters, a thread in Farhādī’s films since at least Fireworks Wednesday.

‛Imād’s frenzied search for his wife’s attacker in the film’s second half springs from what Peter Bradshaw implicitly argues are obsolete ideas of masculine virtue. While Bradshaw may believe that such matters are best left to the police, ‛Imād makes no recourse to the law partly because of his (and his wife’s) understanding of family honor as a private matter. Of course, such conceptions of honor had motivated many homegrown melodramas’ protagonists, who also often operated on the margins of the law.41Partovi, Popular Iranian Cinema before the Revolution, 118-25 The key difference between Farhādī’s characterization of ‛Imād and those representations of film heroism from a previous era would seem to be that the character seeking vengeance is not some traditionally-minded lumpen hero but a member of the exemplary modern middle class. However, it was also those from the exemplary middle class who were the most likely audiences of prerevolutionary melodramas, despite their frequent, loud, and continued protestations to the contrary.42For middle-class denialism about their fandom for Pahlavi-era melodramas, see Pedram Partovi, “Reconsidering Popular Iranian Cinema and its Audiences,” Iranian Studies 45, no. 3 (May 2012): 439-447 [5] “Furūshandah rikūrd-i fur Interestingly, The Salesman became Farhādī’s most commercially successful film in Iran to date, ending its cinematic run as the biggest box office hit in history.43“Furūshandah rikūrd-i furūsh-i sīnimā-yi Īrān rā shikast,” Afkār Nīyūz (November 9, 2016) It also won Farhādī’s second Oscar for best foreign film, though with significant controversy. President Donald Trump’s 2016 “Muslim ban” on travel to and resettlement in the United States, which included Iranians, may have inspired some Academy voters to support the film to make their displeasure with this policy known.44Mike Fleming, Jr., “Are Best Foreign Film Nominees Trumped by Politicized Voting?” Deadline, (February 16, 2017), https://deadline.com/results/#?q=%E2%80%9CAre%20Best%20Foreign%20Film%20Nominees%20Trumped%20by%20Politicized%20Voting?%E2%80%9D

Figure 12: Ra‛nā, who was afraid of being alone at home, went to the roof until ‛Imād arrived. Furūshandah (The Salesman, 2016), Asghar Farhādī, accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2RDZKuwFmEA (00:38:46)

The film’s denouement has ‛Imād confronting the street peddler who violated his wife’s honor, seeking to humiliate him in the way that he has presumably been humiliated. ‛Imād in effect tracks down in real life the man that he’s playing on stage. Farhādī has claimed that the film at its center asks a question that Arthur Miller forefronts in his play: Is Biff Loman’s humiliation of his philandering father, leading him to commit suicide, justified? In other words, do two wrongs make a right?45Asghar Farhadi: Interviews, 124. While ‛Imād answers affirmatively and proceeds to torment the man until he suffers a series of heart attacks, Ra‛nā is repulsed by his cruelty. According to Farhādī, Ra‛nā represents a long line of patient, forgiving women in his films who are invariably contrasted with blundering and impulsive men.46Asghar Farhadi: Interviews, 126. Rāzīyah in A Separation or Farkhundah (Sahar Guldūst) in Qahramān (A Hero, 2021) serve as additional examples. The characterization of women as emotionally stable and grounded (and their male reverse images) has its own long history in Pahlavi-era melodramas.47Partovi, Popular Iranian Cinema Before the Revolution, 107. Farhādī doesn’t provide the audience with closure on ‛Imād and Ra‛nā’s relationship status, but the events have certainly not brought them together, as made apparent in the coda where they silently sit beside each other while readying to take the stage.

In his most recent production, A Hero, Farhādī once more mined the rich narrative vein of characters choosing expediency over truth and its attendant costs. The film won the Grand Prix at the Cannes Film Festival and was a moderate commercial success at home. The story itself, like others that Farhādī has developed into film scripts (e.g., Low Heights), was based on true events. Specifically, in 2010 Mohammad Reza Shokri found and returned a bag of cash while on temporary release from debtor’s prison, briefly becoming a media star for his good deed. Similarly, the film’s seeming hero, Rahīm (Amīr Jadīdī) receives a two-day leave from prison to settle an unpaid debt with gold coins that his girlfriend Farkhundah found in a handbag left behind at the bus stop. The debt is owed to his former brother-in-law and antagonist Bahrām (Muhsin Tanābandah). Unlike A Separation or The Salesman where class defines the conflict, the acrimony between Rahīm and Bahrām is rooted in personal history, much of which remains off-screen. When Rahīm learns that the coins’ appraised value does not cover the entire debt, he approaches Bahrām about payment in installments, which he refuses. Rahīm then sets out to find the coins’ true owner, prodded by his sister who discovers them among his things and worries that Rahīm’s ill-gotten gains will only bring the family more shame. Farhādī depicts Rahīm as an unbecoming hero, unsure of himself and his actions. Even on those occasions when Rahīm takes the initiative, he quickly folds at the first sign of adversity, and his tentative and halting physical movements mirror his character traits. Thus, Farhādī’s direction together with Jadīdī’s acting portray him nervously loitering in the background of scenes, hesitating at doorsteps, or entering and quickly reversing out of rooms.

This good Samaritan turn, despite his initial motivations, gains him minor celebrity status on social media. While Bahrām and audience members may have suspicions about his heroism, a local charity and the prison are happy to promote Rahīm’s supposedly selfless act to advance their own interests. Rahīm’s inability to take control of his own narrative allows the prison to use his story to overshadow the news of a prisoner death and the charity to throw a fête in his honor to raise their fundraising profile. He neither takes advantage of a television interview on prison grounds to shine a light on poor prisoner conditions nor does he stop the charity from exploiting his son’s speech impediment to drum up more sympathy and donations. Predictably, events external to Rahīm provide the next twist in his story. Just as he plots his return to normal life, a rumor spreads on social media about his true intentions to keep the coins.

Figure 13: A film still from Qahramān (A Hero, 2021), Asghar Farhādī, accessed via https://vigiato.net/p/227598

The film shines a light on the social media phenomenon in Iran and its role in the making and unmaking of heroes. If neighborhood gossip helped to drive ‛Imād in The Salesman to disastrous ends, then social media seemingly set Rahīm on a similarly dangerous path. Before he can take up his new job arranged by the charity, the prospective employer, concerned about bad publicity, insists that he bring testimony from the woman who claimed the handbag to clear his name. The seeming disappearance of the presumed owner encourages Rahīm, his sister, and Farkhundah to perversely fabricate proof of their good intentions but fruitlessly. When Rahīm violently confronts Bahrām, whom he believes to be behind the rumors, Bahrām’s daughter Nāzanīn (Sārīnā Farhādī) captures it on video and eventually releases it on the internet, further sinking his reputation and souring those who had sought to capitalize on his fame. The charity takes back its donations to pay for the release of a death row inmate but, on Farkhundah’s insistence, they claim in the press release that Rahīm had voluntarily surrendered the money to save a life. A prison official in turn seeks to sanitize their links to Rahīm’s story by producing a video about his most recent so-called act of charity featuring a tearful appeal from his son, Sīyāvush. Finally, Rahīm takes a principled stand to protect his son’s dignity—violently confronting the official to delete the video. A bittersweet conclusion once more resets the puzzle pieces of Farhādī’s narrative. Rahīm returns to prison, putting aside the prospect of a new life with Farkhundah and Sīyāvush. However, he returns with a new outlook, which the character visibly signals with his freshly shaven head.

Figure 14: A film still from Qahramān (A Hero, 2021). Asghar Farhādī, accessed via https://vigiato.net/p/227598

Shortly after the film’s release, Farhādī faced accusations of wrongfully taking credit for A Hero—his protagonist’s reputational crisis now mirrored by his own real-life predicament. Āzādah Masīhzādah, a student who produced a documentary about Shokri after attending a filmmaking workshop convened by Farhādī, claimed that he had not only adapted the story but incorporated scenes from her documentary without proper acknowledgment of her work. Appropriately enough, she used social media to publicize her claims against Farhādī.48Rachel Aviv, “Did the Oscar-Winning Director Asghar Farhadi Steal Ideas?” The New Yorker, (November 7, 2022), https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2022/11/07/did-the-oscar-winning-director-asghar-farhadi-steal-ideas After arbitration failed, Masīhzādah filed a court case against Farhādī to share the credit and revenues for A Hero. As of this writing, a final verdict has yet to be issued. However, the court case and resulting press has unleashed other allegations of Farhādī cheating his collaborators of their fair dues. The now exiled actress Gulshīftah Farahānī described Farhādī as a vasat-bāz, or a shrewd, calculating person who excels at playing the middle against the sides, to explain what she claimed to be his deceitful behavior towards colleagues and associates.49Aviv, “Did the Oscar-Winning Director Asghar Farhadi Steal Ideas?” Farhādī’s preoccupation with characters’ ethical struggles in a hypocritical and stifling social and political setting is even more interesting when considering these accusations. Farahani admits that holding firm to your principles is a costly endeavor in today’s Iran and that distortion and concealment of one’s intentions is necessary for survival—a skill that, according to her, Farhādī has mastered.50Aviv, “Did the Oscar-Winning Director Asghar Farhadi Steal Ideas?”

Indeed, if Farhādī’s true genius is his cross-over appeal with audiences and critics at home and abroad, it is by his own admission rooted in an ability to present himself and his work to different audiences in different ways at the same time.51Hamid, “Freedom and Its Discontents,” 42. In other words, he has successfully incorporated in his films multiple genres, aesthetic sensibilities, and social ideals, which he has revealed selectively and his varied audiences have received selectively. It is the very shape-shifting, chimerical nature of Farhādī’s cinema.

Cite this article

Asghar Farhādī, born in 1972 in Humāyūnshahr, Iran, is one of Iran’s most celebrated filmmakers, renowned for his morally intricate narratives and modern realist style. Beginning his career in theater and television, Farhādī transitioned to filmmaking with Low Heights (2002), co-written with Ibrāhīm Hātamī Kīyā, marking a shift from war-focused cinema to post-war social challenges. His early films, such as Dancing in the Dust (2003) and Beautiful City (2004), explore themes of poverty, family, and ethical dilemmas, gaining acclaim for their narrative depth and emotional resonance. Fireworks Wednesday (2006) solidified Farhādī’s reputation, introducing middle-class melodrama as a focus. This article traces Farhādī’s rise to international prominence, examining his ability to craft universally relatable stories rooted in the complexities of Iranian society.