Magnificent Productions (Film-ī Fākhir) or Islamic Blockbusters of 2005-2013

Figure 1: A scene from the Fajr Film Festival in Iran

Background

When Mahmūd Ahmadīnizhād returned for another term as president at the disputed 12 June 2009 election, massive protests commenced the day after the announcement of the results. Already in the lead up to the election many in the film industry had been a part of the opposition, representing a cultural site of strong political protest, and they maintained this position in what coalesced into the Green Movement, not quashed until early 2010.1The Iranian Green Movement, often contemporaneously referred to in the West as the Persian Spring, began immediately following the 12 June 2009 presidential election. The incumbent Mahmūd Ahmadīnizhād, who was noted for his severe human rights violations, particularly in relation to the significant increases in the number of political prisoners and in the use of the death penalty, was returned for his second term in a landslide victory. However, the opposition believed that the results were manipulated. On 13 June protests, initially relatively peaceful, broke out. Quickly the protests became larger and more violent, and they spread internationally to become the largest since the 1979 Revolution. The movement fizzled out over the next year.

While the conservative Ahmadīnizhād presidency had begun making clear its goal to establish Iran as the centre for Muslim filmmaking in its first term, not much headway had been made. An internal report, prepared by the Political Division of the IRIB (Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting) shortly after the elections in October 2009, presented this problem from the regime’s perspective (It should be borne in mind that IRIB reports directly to Supreme Leader Āyatallāh ‛Alī Khāmanah’ī). The report stated that,

nowadays Iranian cinema is witness to the production of underground films that are produced outside of the official system and without government supervision. Filmmakers don’t get official permission to get their films produced and create them secretly and find possibilities of showing the film internationally and by doing so, attract foreign capital; to the point where we can now discuss the formation of an underground cinema in Iran. One of the most important characteristics of this Iranian cinema is its lack of regard for official criteria and rules.2“Internal State Document Exposes the Role of the Iranian TV in the Crackdown on Filmmakers,” Center for Human Rights in Iran, September 28, 2011, https://iranhumanrights.org/2011/09/filmmakers-irib/

The policy makers and law enforcers under Ahmadīnizhād’s government now began holistically, if apparently somewhat erratically, to redress this by attempting to re-harness the industry to the government’s own agenda. A range of strategies were devised and implemented to curtail both films that could not be tolerated and filmmaker activism, whilst also creating some incentives to achieve the desired results in acceptable filmmaking. Cultural diplomacy was a part of the solution, with the government concurrently adapting a more aggressive approach to cultural invasion and what it perceived as the soft war from the West.

Figure 2: A display in the foyer of Irshād (23 February 2011) featuring ‛Alī, star of the antisemitic Saturday’s Hunter (Shikārchī-i Shanbah), inside the Star of David. Photo by the author.

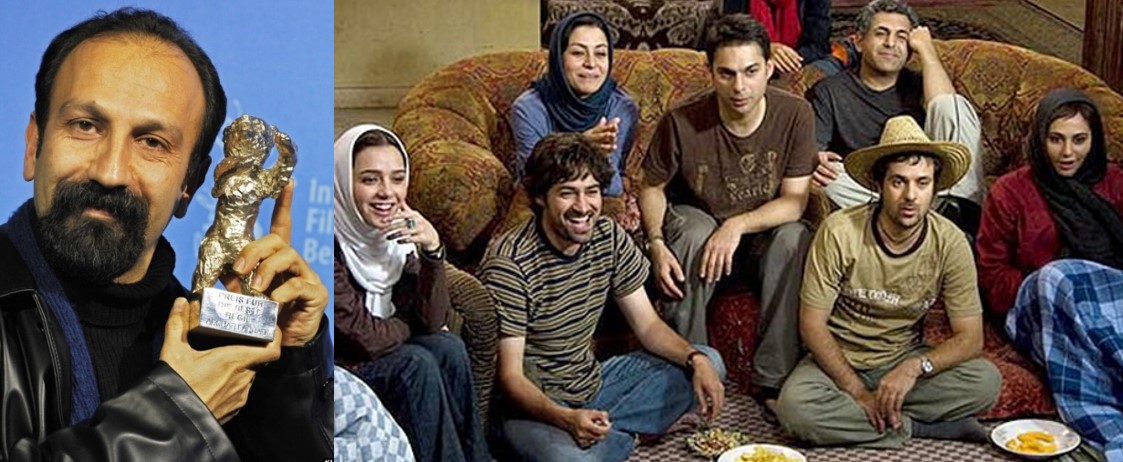

Just days before the election, Asghar Farhādī’s About Elly (Dar bārah-yi Elly, 2009) was released domestically. Here was a film that had already won international critical acclaim with a Silver Bear for Best Director at Berlin some months earlier, was tolerated, although not welcomed, by the government, and gained public approval, achieving number two at the domestic box office that year.3Regarding the Silver Bear, see “Awards, International Jury 2009,” Berlinale, Accessed August 1, 2024, https://www.berlinale.de/en/archive/archive-overview/search.html/s=2009/o=desc/p=1/rp=5; regarding the film’s ranking at the box office, see: “About Elly (2009),” Box Office Mojo, Accessed August 1, 2024, https://www.boxofficemojo.com/title/tt1360860/. A trajectory that embraced both international and domestic success and government acceptance also provided filmmakers with a new model. Some filmmakers began critiquing their world in a different way. These filmmakers began creating (and challenging the regime with) controversial films about corruption and dubious moral practices. Exemplary might be Private Life (Zindigī-i Khusūsī; dir. Muhammad Husayn Farah-Bakhsh, 2012), The Guidance Patrol (Gasht-i Irshād; dir. Sa‛īd Suhaylī, 2012) and Manuscripts Don’t Burn (Dastnivishtah-hā nimīsūzand; dir. Muhammad Rasūluf, 2013). This body of films was coalescing into a kind of independent or ‘outsider’ metanarrative about Iran.

Figure 3: Left: Asghar Farhādī with the Silver Bear award. Right: An image of a scene from the film About Elly (Dar bārah-yi Elly), Asghar Farhādī, 2009

Meanwhile Sayyid Muhammad Husaynī, Minister of Culture and Islamic Guidance for the duration of Ahmadīnizhād’s second term, reminded filmmakers that culture was “not a form of entertainment.”4“Iran Ready to Make Film on Gaza 22-Day War,” Tehran Times, January, 30, 2012. https://group194.net/english/article/27353.

The New Strategies

The government placed renewed emphasis on filmmaking with Islamic values to countermand filmmaker challenges to the regime and introduced new strategies ranging from funding production through to sell through videos at grocery stores. A little-known fact from a reliable but necessarily anonymous source is that the director and screen writer Ja‛far Panāhī rejected a funding offer through the Fārābī Cinema Foundation at the same time (2010) that Muhammad Rasūluf’s Goodbye (Bi umīd-i dīdār, 2011) was supported by Fārābī.5The Fārābī Cinema Foundation was established as a semi-governmental organisation in 1983 to oversee cinema production, funding, and distribution both domestically and internationally. Its role also embraces showcasing Iranian cinema through, amongst others, the major Iranian film festival—the Fajr International Film Festival—and the Isfahan International Festival of Films for Children & Young Adults.

Another funding strategy to ensure appropriate films for both domestic and international consumption was a short-lived and little-known initiative for films referred to as “Fīlm-ī Fākhir.” The term “Magnificent Productions” used here is perhaps the closest translation, although the term “Islamic Blockbusters” might in most cases also be appropriate.

The desire to position itself at the centre of Muslim filmmaking also resulted in funding more closely aligned with its cultural diplomacy strategies. Genres and topics which had been developed for domestic consumption, often national narratives, were re-framed or hybridised for both domestic consumption and international distribution as part of the domestic and international soft war. This will be discussed in relation to individual films further on. The Magnificent Productions, funded and made between 2009 and 2013, with a further two screened at the Fajr International Film Festival in 2014, are best categorised by content, which can be divided, not surprisingly, and with some overlap or hybridization, into five categories or ‘genres’: Religious, Resistance, Sacred Defence, Social Issues, and Foreign Policy.6For more information on Sacred Defence Cinema in Iran, see Niki Akhavan, “From Defence to Intervention: The Iran-Iraq War on Screen and the Evolution of Sacred Defence Cinema,” in Cinema Iranica Online (Encyclopaedia Iranica Foundation), 2024, https://cinema.iranicaonline.org/article/from-defense-to-intervention-the-iran-iraq-war-on-screen-and-the-evolution-of-sacred-defense-cinema/.

The government also sought to make co-productions with Muslim countries and other allies using opportunities and initiatives as they presented themselves. These included the “Hollywoodism” conference introduced in 2009, internationally presented Sacred Defence Festivals, and international Ministerial visits.

Fīlm-i Fākhir: Producing the Magnificent Productions

The “Magnificent Productions,” generally although not always, were bigger-budget films that placed a stronger emphasis than previously on production values, and for the first time in a number of cases used international production support including special effects. They might perhaps be understood as an attempt to create Pan-Islamic blockbusters.

Here it is important to recall Tom O’Regan’s observation that every national cinema has a relationship with Hollywood.7Tom O’Regan, Australian National Cinema (London: Routledge, 1996), 1. In the case of Iran this is a particularly conflicted one. Chris Berry has argued that the originally American owned blockbuster has been appropriated and “de-Westernised” or adapted to local circumstances in Korea and China through the inflection of “native sentiments.”8Chris Berry, “What’s Big about the Big Film?: ‘De-Westernising’ the Blockbuster in Korea and China,” in Movie Blockbusters, ed. Julian Stringer (Abingdon, England: Routledge, 2003), 217–229. He claims that it was not only trade issues but memories of American colonisation that resulted in protectionist measures against Hollywood. Berry also discusses what was described in China as the “giant film” or the epic. This was a cycle of Chinese revolutionary epic and/or historical films, often biographical, with big budgets and spectacular scenes, but embodying a “seriousness of purpose,” made between the late 1980s and 1997. He also emphasizes the “prioritization of pedagogy” over the “emphasis on entertainment” of the Chinese “big film” or blockbuster.

A crucial point here is the Asian modulation on the blockbuster for the purposes of national identity, and the issues and characteristics around the East Asian situation, should be born in mind when examining the Iranian experience. For, indeed, these modulations, issues, and characteristics resonate with the Iranian situation. In Iran, a form of protectionism had already been effected with the establishment of the Islamic Republic, where Iranian rhetoric against Hollywood was always strongly couched around issues of a-territorial colonialism and imperialism in the form of “Westoxification” or “Gharbzadigī.”9See for instance Jalāl Āl-i-Ahmad, Gharbzadigī (Mazdā Publishers, 1982). The Chinese “big film” suggests a model for the Fīlm-i Fākhir from the cinema of one of Iran’s allies.

The “Magnificent Productions” utilized two government bodies, IRIB and Fārābī, in different ways. Although there had been some movement from around 2000, Fārābī was the major government body for funding, production, distribution and exhibition for experienced filmmakers until 2009. Between 2009 and 2013, suggesting a lack of government confidence in Fārābī, there was significant dispersal of their roles to other organizations. But a major feature of this category of films, the Magnificent Productions, was that exceptionally the funding was directly allocated to specific projects by the Guardian Council and then administered by the Fārābī Cinema Foundation rather than from Fārābī’s own budget, leaving Fārābī with administrative rather than creative control.

The other major arm of film production in Iran is the Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting (IRIB), one of the largest media organisations in Asia. IRIB produces both tele-movies and theatrical features with an emphasis on family, religion, and Sacred Defence, and maintains a foreign broadcasting arm. The director is appointed by the Supreme Leader, a regulation enshrined in the Iranian Constitution, and the whole sits under the parliament. IRIB’s structure and size afford it enormous power.

The Magnificent Productions: A Chronology

Individual Magnificent Productions are listed here chronologically with an indication of how the content of each conformed to Islamic values and/or the requisite cultural diplomacy.

The first of the Magnificent Productions to be screened was The Kingdom of Solomon (Mulk-i Sulaymān; dir. Shahrīyār Bahrānī, 2010), premiering at the 28th Fajr International Film Festival (1–11 February 2010). This blockbuster, which recounts the Quranic version of the Prophet Solomon’s life, is a hybrid of both religion and history, with action mixed in, and functions as a kind of back history to the contemporary Israeli/Palestinian conflict.

Figure 4: An image of a scene from the film The Kingdom of Solomon (Mulk-i Sulaymān), Shahrīyār Bahrānī, 2010.

A prominent, almost contemporary production from IRIB in the field of epic religious television series, which began production shortly after Ahmadīnizhād came to power, was the heavily action-based Mukhtārnāmah (dir. Dāvūd Mīrbāqirī, 2010-2011). Comprised of forty-one-hour episodes shot over five years and broadcast in 2010 and 2011, it was based on the life of a Shia Muslim leader who sought to avenge the martyrdom of Imam Husayn. The reception of this series on YouTube from 2010 to 2012, when it was only in Farsi, was not positive. Gradually Urdu and Indonesian versions were uploaded, and possibly others. Its popularity increased enormously when an English sub-titled version was uploaded. This strong international following must have suggested a model for export. However, as must have been also clear to the Iranian authorities, while the format and style appealed, the subject matter concerning the split between Sunni and Shi’ite, and an emphasis on confessional differences within Islam, was not optimal for an international Muslim market. Indeed, the difficulties for Iran in positioning itself as the centre of international Muslim filmmaking become apparent even when just the two major religious divisions, Sunni and Shi’ite, are considered, as will be discussed in relation to Majīd Majīdī’s Muhammad: The Messenger of God (Muhammad Rasūlallāh, 2015), and IRIB appears to have taken this into consideration in planning productions and co-productions for the Muslim world. Thus, The Kingdom of Solomon was a clever choice of subject matter, with King/Prophet Solomon common to the Abrahamic faiths.

Figure 5: An image of a scene from the film Mukhtārnāmah, Dāvūd Mīrbāqirī, 2010-2011.

Oscillating between peaceful landscape scenes focusing on Solomon’s spiritual reflections and big battle scenes, the film features a negative and racist portrayal not only of the Jews, but also of Iran’s (pre-Islamic) Zoroastrians, who are depicted in the prologue as primitive and barbaric, leaping around a fire in a cave rather than inside their famous fire temples. This latter reflects the government’s pains to repress pre-Islamic Iranian traditions and customs, described by Hamid Naficy as “the interplay between Iranian and Islamic philosophies.”10Hamid Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema, Vol. 3: The Islamicate Period, 1978-1984. (Durham: Duke University Press, 2012), xxi.

Iran’s first digital film, The Kingdom of Solomon, set a record in terms of budget for an Iranian film (“About US$5 million” was the comment given in conversation with the author from a Fārābī official at the Fajr International Film Festival that year). In addition, Iran turned to its ally, China, for the special effects. (According to the film’s website, it was [only] recognized for technical awards at the most important annual domestic film awards, Fajr 2010 and the 14th Iranian Cinema Celebration in 2010). Plans for the film included a version dubbed into Arabic to be distributed through iFilm, Iran’s Arabic-language television network. The ideological importance of the film to the Iranian government was underlined by a contemporary statement from the director of iFilm, Katāyūn Husaynī, “The dominance of Hollywood is over and iFilm will demonstrate the power of Iranian cinema in promoting religious themes through broadcast of the film at an appropriate time.”11“Producer Says West Thwarts World Premiere of The Kingdom of Solomon,” Tehran Times, January 4, 2011. https://en.mehrnews.com/news/43908/Producer-says-West-thwarts-world-premiere-of-The-Kingdom-of. However in the same article, the film’s producer, Mujtabā Farāvardah, claimed that international distribution and screenings of the film had been sabotaged by US interests, with pressure exerted on some Arabian festivals not to screen the film because, “The plot of The Kingdom of Solomon is based on Quranic verses, which is at odds with Jewish-held notions. Thus Hollywood, which is ruled by people of Jewish ethnicity, has been outraged by the film.”12“Producer Says West Thwarts.” The film did, however, win the Best Film and Best Director awards at the first Jewar Film Festival held in Baghdad in December 2010.

Figure 6: An image of a scene from the film The Kingdom of Solomon (Mulk-i Sulaymān), Shahrīyār Bahrānī, 2010.

The other Magnificent Production presented at Fajr in 2010 was Saturday’s Hunter (Shikārchī-i Shanbah; dir. Parvīz Shaykh-Tādī, 2009), an improbable and violent melodrama concerning a Jewish sect leader whose goal is to shoot down Palestinian civilians and seize their land. His daughter-in-law is a Christian and he is training his grandson to take over his role. One of his important tenets, based on stereotyping of Jews, is that God will forgive any wrong-doing if a sufficient payment is made to his cause. Contrary to claims by the film director, in the opinion of international guests at Fajr that year the film displays strong antisemitism rather than anti-Zionism.13“Iranian Distributor Has Big Plans for Making Anti-Zionist Films,” Tehran Times, November 16, 2011, https://dagobertobellucci.wordpress.com/2011/12/12/the-saturday-hunter-film-iran-2011/. Saturday’s Hunter was shot partly in Lebanon, in Farsi, Arabic, and Hebrew. It enjoyed a long official exhibition history, screening after Fajr in the 17th International Children’s Film Festival in Hamedan, in competition at the 2011 Roshd International Film Festival, and in 2012 in the Muqāvamat Film Festival. Meanwhile while it was on general release, Muhsin Sādiqī, the managing director of Jibra’īl Film Distributing Company, commented that “[t]he film is still being screened in eight theaters in Tehran and according to a poll conducted by the IRIB, over 40 percent of the film audience called the film excellent.”14“Iranian Distributor Has Big Plans for Making Anti-Zionist Films.” The film aired on Iranian TV Channel 1 on 17 August 2012. The film’s only international outing seems to have been, along with 33 Days, discussed next, at The Days of Resistance Cinema, a film festival in Gaza in December 2012.

Figure 7: An image of a scene from the film Saturday’s Hunter (Shikārchī-i Shanbah), Parvīz Shaykh-Tādī, 2009.

33 Days (Sī-u-sih rūz; dir. Jamāl Shūrjah, 2011), another high-profile Magnificent Production of the Resistance genre, is an Iranian/Lebanese co-production by insider Iranian director, Jamāl Shūrjah, known for his 1993 Sacred Defence film, Majnoon Epic (Hamāsah-i Majnūn). Presented in international competition at Fajr, 33 Days was the recipient of the hastily created Human Rights Award from an all-Iranian jury after it was overlooked by the international jury. It was subsequently screened in the Cannes film market by Fārābī and released widely in Lebanon. The fiction film about the Israeli/Lebanese war was initially scripted by ‛Alī Dādras who claimed in conversation that his even-handed documentary-style treatment was significantly revised to become a heavy-handed commercial propaganda piece.15‛Alī Dādras (director), in conversation with the author, February 2011. That it was intended as an international film is made clear with its use of Arab actors (Egyptian star Hanan Turk, Syrian actor Kinda Alloush, and four well-known Lebanese actors) and apart from ten minutes in Hebrew, the film is in Arabic (not Farsi).

Figure 8: An image of a scene from the film 33 Days (Sī-u-sih rūz), Jamāl Shūrjah, 2011.

These three productions, all focusing on Iran’s relationships with Israel, Palestine, and Lebanon, share something further—their dubious success at the domestic box office. According to press reports and the film’s website, The Kingdom of Solomon took US$2.7 million between its 29 September 2010 release and early January 2011. However, according to various industry figures, the strategy for achieving this box office take involved government departments purchasing and distributing large blocks of tickets. An email to an Iranian distributor about the other two elicited the following response: “Saturday’s Hunter’s box-office was . . . about $100,000 (in official rate) and $62,000 (in free market rate). And 33 Days was . . . $20,000 in official rate and $13,000 in free market rate. So, both films’ grossing were just tragedy!”16Muhammad Atibbā’ī (Iranian Independents), email to the author, June 12, 2013. So while both films fitted the political policy logic quite well, there was some question about domestic box office support.

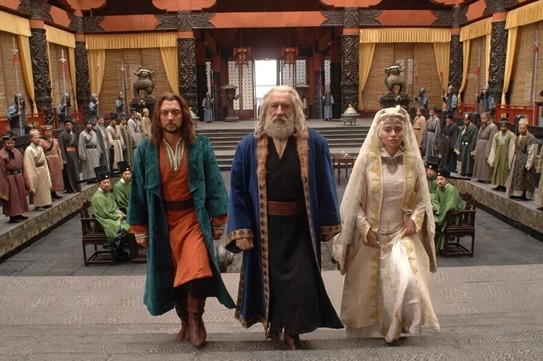

At Fajr in 2011 a very different kind of Magnificent Production was premiered. Maritime Silk Road (Rāh-i ābī-i abrīsham, 2011) from veteran director, Muhammad Buzurgnīyā, fictionalized the first sea trip from Persia over the Indian Ocean to China. The Iranian Sulaymān of Sīrāf, according to historical documents, was the first West Asian trader to cross the Indian Ocean to China, travelling some 500 years before Marco Polo. The US$6 million film is clearly an attempt at a big budget, entertaining film in the adventure genre. While “swashbuckling” is not quite an accurate description of this film, it would be hard to discount the influence of the Hollywood Pirates of the Caribbean franchise.

Figure 9: An image of a scene from the film Maritime Silk Road (Rāh-i ābī-i abrīsham), Muhammad Buzurgnīyā, 2011.

The clever high profile casting shows a concerted effort at commercial appeal. Famous veteran Dāryūsh Arjmand plays the wise, aged Captain Sulaymān, leader of the two ship expedition, a piece of casting which would resonate with Iranians for his titular role in the famous Captain Khurshīd (1987, dir. Nāsir Taqvā’ī). He is supported by Rizā Kīyānīyān as Idrīs, the lustful and greedy old captain of the second ship, and ‛Izzatallāh Intizāmī has a cameo. All, despite their own fame, are almost foils for the younger superstar, Bahrām Rādān, one of the more popular actors and pop singers in West Asia, who plays Captain Sulaymān’s handsome young deputy, Shāzān, who keeps the voyage’s logbook.

Figure 10: Bahrām Rādān in a scene from the film Maritime Silk Road (Rāh-i ābī-i abrīsham), Muhammad Buzurgnīyā, 2011.

Various adventures afford opportunities to invoke the good /evil duality of the two captains and their respective deputies. Along the way Captain Idrīs buys himself a beautiful woman from a slave market but is scorned by the virtuous maiden. When Captain Idrīs dies in a misadventure, the equally virtuous Shāzān offers to marry her to provide her with the protection necessary for her to stay on board, but makes it clear that he does not expect conjugal rights. Nonetheless a touch of romance ensues. Finally, they reach China, where they are welcomed as new trade partners, connecting very neatly with contemporary maritime silk road politics.

One of the initiatives that became characteristic of the Magnificent Productions was to engage international talent for these films. For example, award winning Hong Kong composer Chan Kwong-wing was hired for this film. Some of the filming took place in Kanchanaburi, Thailand, using footage from an abandoned project, Siam Sheikh, offering an opportunity for an exotic wedding.

Figure 11: An image of a scene from the film Maritime Silk Road (Rāh-i ābī-i abrīsham), Muhammad Buzurgnīyā, 2011.

The statement made by Ahmad Mīr-‛Alā’ī, Director of Fārābī, at the film’s Tehran premiere points to an additional benefit!

I am happy to say that the foreigners’ efforts in distorting the name of the Persian Gulf is no longer effective. Anybody in the world who watches the film The Maritime Silk Road needs no explanation about the name of the region, which is quite an admirable effort by Bozorgnia.17“Film Premiers in Tehran,” Maritime Silk Road Blogspot, October 2, 2011, http://maritimesilkroad.blogspot.com/2011/10/film-premiers-in-tehran.html.

The Maritime Silk Road found great favour at Fajr, collecting Crystal Sīmurghs for National Best Film, special effects, and cinematography. It was released into cinemas shortly afterwards on 20 February 2011 and was an early example of a film permitted to advertise through street banners, on which the image of superstar Bahrām Rādān was prominently displayed. Despite its national awards, large budget, and substantial publicity, it ranked 18th at the box office with a gross of less than $100,000 (98,000 attendances). (In the same year Asghar Farhādī’s A Separation was number three.) Nonetheless it had some minor success, aside from an ongoing presence in Iranian government film festivals organised internationally through local embassies, when it was awarded the Silver Sword at the International Historical and Military Film Festival in Warsaw, Poland in 2014.18“‘Maritime Silk Road’ Bags Warsaw Award,” Financial Tribune, September 14, 2014, https://financialtribune.com/articles/art-and-culture/575/maritime-silk-road-bags-warsaw-award.

Maritime Silk Road appears to be a simple and enjoyable historical adventure film with little obvious political or religious baggage. There was however a political agenda—to further diplomatic relationships with China by depicting an historical connection. This was confirmed in October 2013 by the Chinese President Xi Jinping’s public announcement of what has subsequently become a strategic initiative, the 21st Century Maritime Silk Route Economic Belt, intended to boost China’s trade links and increase investment along the historic Silk Road, with the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and other countries in the Indian Ocean. This cultural diplomacy element has been clearly demonstrated in the film’s exhibition history. In August 2018 it received a special screening for the second time by the Iranian Cultural Center in Colombo because, as the Sri Lankan curator, Dhanushka Gunathilake, noted to the author in conversation, Sri Lanka is on the Maritime Silk Road.

Another film intended to advance cultural diplomacy was Reclamation aka. Restitution (Istirdād; dir. ‛Alī Ghaffārī, 2012). The film follows a delegation sent to Russia in 1953 to reclaim a Russian indemnity from World War II, with delivery in gold bars. In the spy genre, involving double- and triple-crossing, a wonderfully treacherous (Iranian) woman, a romantic element, and Nazis, it is a lavish period film. It references damages inflicted through “Operation Countenance,” the British and Soviet Union invasion of Iran in August 1941 to ensure oil supplies for the Soviets then fighting Germany. Its raison d’être can be explained by a contemporary political reference, Ahmadīnizhād’s 2010 call for reparations from the Allies, although in the film this demand seems to be limited to Britain rather than Russia, now Iran’s ally.19Michael Hirshman, “President Demands World War Reparations,” Liberty Iran /Radio Free Europe, January 12, 2010, https://www.rferl.org/a/Iran_President_Demands_World_War_Reparations/1927565.html. The film won best film and best actor awards at Fajr in 2013.

Figure 12: An image of a scene from the film Reclamation aka. Restitution (Istirdād), ‛Alī Ghaffārī, 2012.

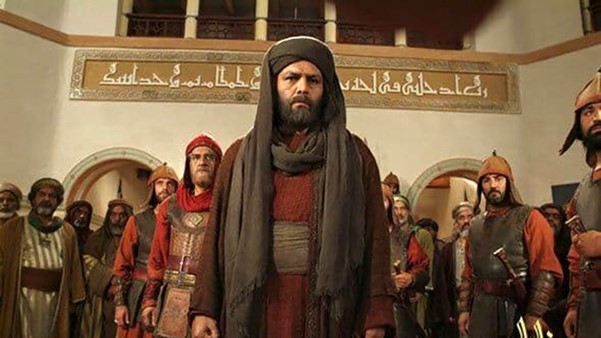

Fajr 2013 featured another religious adventure biopic in the vein of The Kingdom of Solomon. Eagle of the Desert (‛Uqāb-i Sahrā, 2012) by first time feature director Mihrdād Khushbakht, who, like Bahrānī, had come from IRIB, showed all the hallmarks of a director used to making mini-series, particularly in the film’s pacing. Eagle is set in the prophet’s lifetime, prior to the divisions within Islam, making it eminently suitable for a pan-Islamic audience. The film also has strong romantic elements, missing in Kingdom, but a standard trait in these films by now. Although the Fajr catalogue made no mention of this aspect in its chaste summary, clearly the intention was to capture the demographics for both action and romance. The beautiful heroine wears the niqāb or face covering worn in Iran only by the Sunni Muslim minority living round the Persian Gulf, but this potentially broadens its appeal to Sunnis outside Iran.

Figure 13: An image of a scene from the film Eagle of the Desert (‛Uqāb-i Sahrā), Mihrdād Khushbakht, 2012.

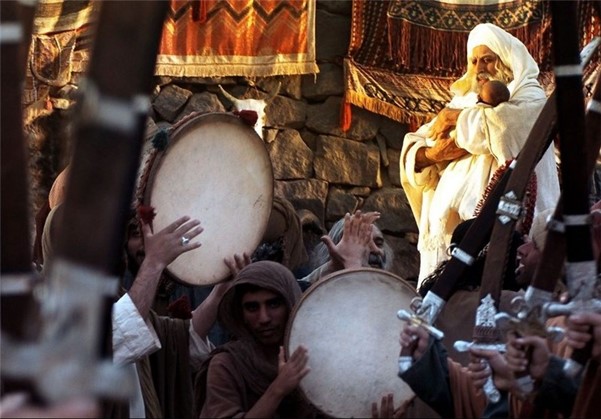

A different approach was taken with the two other Magnificent Productions screened at Fajr in 2013, which were lower budget contemporary melodramas. The Fourth Child (Farzand–i chahārum; dir. Vahīd Mūsā’īyān, 2013) follows the adventures of an Iranian actress volunteering with the Red Crescent (the Muslim version of the Red Cross) in famine-stricken Somalia. Affecting but formulaic, the film shows the idealized, selfless Muslim woman, and advances international outreach and the Iranian concern for peace by depicting its Muslim brothers in Somalia. Fārābī, according to Press TV, organized international screenings sponsored by the UN Children’s Fund (UNICEF), adding the necessary political dimension for a Magnificent Production.20“African Continent to Host Iranian Movie The Fourth Child,” Press TV, August 20, 2013, https://www.theiranproject.com/en/news/45887/african-continent-to-host-iranian-movie-the-fourth-child

Figure 14: An image of a scene from the film The Fourth Child (Farzand-i chahārum), Vahīd Mūsā’īyān, 2013.

For its part, A Cradle for Mother (Gahvārah-i barāyi mādar, dir. Panāhbarkhudā Rizā’ī, 2013) also depicted model Muslim womanhood. A devout female seminarian is determined to return to Russia, where she has studied, as a missionary. When she finally gains the necessary permission from her order, she must forsake the opportunity in order to care for her aging mother. The goal for this film seems to be to make an appealing film with Islamic values suitable for an international audience, achieved when the film premiered internationally at the Moscow International Film Festival in June 2014.

In 2014, two more Magnificent Productions, both in production before the change of government, screened at Fajr. Hussein Who Said No (Rūz-i rastākhīz; dir. Ahmadrizā Darvīsh, 2014) depicts the uprising of Imam Husayn in 680 CE against the caliphs and his subsequent martyrdom. The film apparently took seven years to make and it was announced in November 2012, well before the 2014 premiere, that the film would be dubbed into Arabic and English, indicating a Muslim target audience but also reflecting its unusual production history.21“Ahmadreza Darvish’s New Film on Ashura Uprising to Be Dubbed into English, Arabic,”Mehr News Agency, November 18, 2012, https://en.mehrnews.com/news/52836/Darvish-s-new-film-on-Ashura-to-be-dubbed-into-English-Arabic. This big-budget film was funded by Fārābī but also international companies, as the Tehran Times noted cryptically. It used CGI and also international credits. Post-production was completed in the UK by Academy Award nominated British editor Tariq Anwar and Academy Award winning British composer Stephen Warbeck. The international cast included British, Syrian, Kuwaiti, and Iraqi actors. Although the film fared well at Fajr in early February 2014, winning eight Crystal Sīmurghs including best film and best director, and had ostensibly been made with the necessary fatwa and religious permissions required, there was already protest from a Grand Āyatallāh by mid-February.22“Grand Ayatollah Makarem Outraged Over Depiction of Shia Saints in ‘Hussein, Who Said No,’” ABNA World Service, February 18, 2014, https://en.abna24.com/story/507189. On release in June 2014, the film had further problems. It was significantly cut and was ultimately banned.23Seyyed Mostafa Mousavi Sabet, “Controversial Movie ‘Hussein, Who Said No’ Illegally Uploaded on YouTube, Facebook, EarthLink,” Tehran Times, September 15, 2019, https://shorturl.at/jGML9.

Figure 15: An image of a scene from the film Hussein Who Said No (Rūz-i rastākhīz), Ahmadrizā Darvīsh, 2014.

The second production, Che (2014), is directed by one of the best known of the Sacred Defence filmmakers, Ibrāhīm Hātamīkīyā. Based on an historical figure, it portrays the lead up to and martyrdom of the then Deputy Prime Minister, Mustafā Chamrān, in 1981. He was killed in an attempt to control Kurdish rebels close to the Iraqi border. The film is very nuanced and singles itself out through its unusually sympathetic depiction of one of the main characters, the pre-revolutionary general, and of the Kurds, as well as the importance placed on one of the women. There is also much discussion of Chamrān’s role in Lebanon, giving it its international dimension. The film was under consideration in the Competition of International Cinema, and Fārābī received an unusual award for its support of the film, The Golden Phoenix for National View, which, according to an international jury member in conversation with the author, was created after the international jury could not be persuaded to award it.

Figure 16: An image of a scene from the film Che, Ibrāhīm Hātamīkīyā, 2014.

The funding of the Magnificent Productions ceased with the ending of the Ahmadīnizhād presidency. However, there is one further Islamic blockbuster that cannot be ignored.

Another Kind of Islamic Blockbuster, Majīdī’s Muhammad: The Messenger of God

The above examples show the diversity of content that the government was supporting to create the kind of films that it considered “desirable.” Concurrently, outside the funding model established for the Magnificent Productions, another Pan-Islamic blockbuster of a different order was under preparation. There had long been discussion within government circles as to why Iranian cinema had not produced a challenge to the most famous film to date about the Prophet, The Message (1976), for which Hollywood-based Syrian director, Moustapha Akkad, drew together the talents of Hollywood and the funding and support of sections of the Middle East. In 2008, an Arab production, The Messenger of Peace, with a projected cost of US$131 million. was announced.24Andy Sambidge, “Investors Sought for $131mn Birth of Islam Movie,” Arabian Business, October 30, 2008, https://www.arabianbusiness.com/industries/media/investors-sought-for-131mn-birth-of-islam-movie-83856. In the following year, an article on the website of the Muslim Brotherhood announced that The Matrix (1999) producer Barry Osborne was attached as the producer.25“Oscar Winning Producer Osborne Produces Film About Islam to Bridge Gaps,” Ikhwanweb, August 23, 2010, https://ikhwanweb.com/oscar-winning-producer-osborne/. Both the Arab and the Hollywood connections of these projects would obviously have rankled the Iranian government. After more than thirty years, where was a major film about Muhammad from Iran, ostensibly the centre of Muslim filmmaking?

Figure 17: An image of a scene from the film Muhammad, The Messenger of God, Majīd Majīdī, 2010.

Finally, Majīd Majīdī’s Muhammad, Messenger of God was quietly announced in March 2010 in Screen Daily among other sources.26Jeremy Kay, “Majid Majidi Announces Plans for $30m Mohammad Project,” Screen Daily, March 1, 2010, https://www.screendaily.com/production/majid-majidi-announces-plans-for-30m-mohammad-project/5011348.article. Later it was revealed that the pre-production had begun in 2007, although the film was not completed until 2014. At US$30 million, it would be by far the most expensive and ambitious project ever undertaken inside Iran. (Neither Rizā Tashakkurī, the head of International Affairs in Majīdī’s production company, nor Majīdī was willing to divulge the budget in later discussions, but indications were that it was well in excess of the quoted US$30 million, which Majīdī called “a step forward for Muslim cinema . . . an investment into the development of Muslim cinema,” and figures of US$70 million were circulating at one point.27“Iran’s Premiere of Prophet Mohammed Biopic Reportedly Cancelled,” The Iran Project, February 2, 2015, https://www.theiranproject.com/en/news/149120/iran-premiere-of-prophet-mohammed-biopic-reportedly-cancelled. (There is some difficulty in establishing a figure because some of the infrastructure created specifically for this film, including the construction of a whole town, has been amortised through its use for subsequent productions.)

Figure 18: Majīd Majīdī (with the author) on location near Tehran for the film Muhammad messenger of God.

It is widely believed within the industry that the production money was directly from the Supreme Leader. However Majīdī has stated quite distinctly that the funding source was the Mustaz‛afān Foundation of Islamic Revolution, established after the Revolution with the resources of the Shah’s Pahlavi Foundation.28Majīd Majīdī (director) in interview with the author, February 2014. Maintaining close connections to the Iranian clergy and the Revolutionary Guards, it has assets estimated at around $10 billion. One use of its profits is to “develop general public awareness with regards to history, books, museums, and cinema.”29Paul Klebnikov, “Millionaire Mullahs,” Forbes, July 7, 2003, https://www.forbes.com/global/2003/0721/024.html?sh=527a1b504108. In the 1980s the foundation was producing some seven features a year, including Makhmalbāf’s The Marriage of the Blessed (1989) and an early Banī-I‛timād film, Off-limits (Khārij az Mahdūdah, 1988). Until it backed Muhammad, the Mustaz‛afān Foundation would appear to have had little involvement with cinema production since then. The important point is that the film was funded indirectly from the judiciary, not through the standard Irshād or Fārābī funding channels, or, as were the Magnificent Productions, channeled via Fārābī from the Guardian Council.30Irshād, or the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance (Vizārat-i Farhang va Irshād-i Islāmī), has a brief as wide as its name suggests. In relation to film, it grants the initial shooting permit. It also grants other shooting permits, script approval, and the essential final permit for films to screen either domestically or internationally. Films may receive either or just one of these permits. It is not unheard of for a film to receive an international permit but not a domestic one. The Ministry also approves importation of films into Iran.

Figure 19: An image of a scene from the film Muhammad, The Messenger of God, Majīd Majīdī, 2010.

Producing the film was Muhammad Mahdī Haydarīyān, Deputy Minister for Cinematographic Affairs under the Khātamī government, and before that a senior executive in IRIB. It was Haydarīyān, Nacim Pak-Shiraz has noted, who “first suggested the notion of ma’nagara [or spiritual] cinema.”31Nacim Pak-Shiraz, Shi’i Islam in Iranian Cinema: Religion and Spirituality in Film (London: Tauris, 2011), 55. Little expense was spared. The main set was much more substantial than its Cinecitta or Hollywood equivalents (in Italy and the US, respectively), with craftsmen brought from Italy for its construction. A large contingent of international crew was used. Among the more famous were Indian composer, A.R. (Allahrakka) Rahman, who had won two Academy Awards (and faced a fatwa by an Indian Muslim group for working on the film), Visual Effects Supervisor, Scott E. Anderson, both an Academy Award and BAFTA recipient, production designer Miljen Kreka Kljakovic, costume designer Michael O’Connor, and, most notably, the Italian cinematographer, Vittorio Storaro. All the post-production was completed in Munich.

There was little publicity following the initial announcement in 2010, with articles promoting the film starting to appear in 2014. At this time, Majīdī stated his intention for making the film, perhaps the ultimate attempt to make Iran the centre of Muslim filmmaking: “We’re going to help open your eyes to what Islam really is all about.”32Jeremy Kay, “Majid Majidi Launches Promo for New Film Muhammad,” Iranian Film Daily, March 2, 2010, https://www.screendaily.com/production/majid-majidi-announces-plans-for-30m-mohammad-project/5011348.article.

The film premiered as the opening night film at the Montreal World Film Festival in 2015, where Majīdī’s previous films had premiered internationally. Ostensibly, it also released domestically across the country on more than 320 screens and in cultural centres equipped for the screenings by the Mustaz‛afān Foundation.33Nick Vivarelli, “Iran Picks Rise of Islam Epic ‘Muhammad: The Messenger of God’ for Foreign-Language Oscar,” Variety, September 28, 2015, https://variety.com/2015/film/global/iran-picks-majid-majidis-rise-of-islam-epic-muhammad-the-messenger-of-god-for-foreign-language-oscar-1201603724/.

There were two major issues facing Majīdī in making a film about Muhammad. One was reminiscent of the early days of the Islamic Republic when filmmakers had struggled with the difficulties of infusing films with Islamic values—a lack of precedents. Majīdī has noted that his only precedents were western biblical epics.34Majīd Majīdī (director) in conversation with the author, February 2014. He worked very closely with Storaro for two years of pre-production to develop an appropriate visual model for depicting religious or spiritual material. Storaro was strongly influenced by the Mannerist artist Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio with his use of chiaroscuro, and Majīdī noted his ability “to help make the depiction [of Muhammad] possible . . . using ‘various combinations of light and darkness.’”35Ishaan Tharoor, “Iran’s Most Expensive Film is About the Prophet Muhammad, But He Won’t Get Screen Time,” Washington Post, January 30, 2015, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/worldviews/wp/2015/01/30/irans-most-expensive-film-is-about-the-prophet-muhammad-but-he-wont-get-screen-time/. The film’s visually stunning aesthetic references central and southern European Renaissance painting. Yet despite this and its significantly better production values, the film remains consistent with Iranian religious drama.

Figure 20: An image of behind the scenes of the film Muhammad, The Messenger of God, Majīd Majīdī, 2010.

It has been criticized by one Arab writer as inappropriate, “conceptually and culturally clash[ing] with what Islam stands for, where geometric ornamentation has reached a pinnacle in the Islamic world that stresses the importance of unity and order through the use of geometric patterns along with calligraphy, and vegetal patterns encompass the non-figural design in Islamic art.”36Yousef Linjawi (Saudi graduate student) in an essay submitted to the author in 2019. This suggests a more confronting problem—reconciling the film to the various branches of Islam. Majīdī had stated, “this film contains no controversies and no differences between the Shia and the Sunni points of view.”37Kay, “Majid Majidi Launches Promo for New Film Muhammad,” 2010. To ensure its suitability for a Sunni market, Majīdī had consulted some forty Shia and Sunni experts. He conformed to the obvious—he avoided showing the Prophet’s face by using chiaroscuro, shooting from behind, or showing body parts only. Nonetheless he received queries, threats, and fatwas from other Muslim nations, including fatwas from Indian Muslims, the Saudi Grand Mufti Shaikh Abdul Aziz Al Shaikh, and Egypt’s Grand Imam of al-Azhar, Sheikh Ahmed al-Tayyeb, indicating the substantial problems facing Iranian productions for an international market.38Nada Ramadan, “Controversial Iranian Film on Prophet Muhammad Set for Premiere,” The New Arab, August 27, 2015, https://www.newarab.com/opinion/controversial-iranian-film-prophet-muhammad-set-premiere.

Figure 21: An image of the Prophet’s childhood in the film Muhammad, The Messenger of God, Majīd Majīdī, 2010.

Although Majīdī claims he portrays only the commonalities between the different branches of Islam, he does take considerable artistic licence to weave his tight script with interconnecting plot points and effective foreshadowing that one might expect in an epic. Also notable is that Majīdī embraces the Abrahamic faiths with story lines relating to both Jews and Christians. The Christian storyline, just a short incident in the concluding section of the film, tells of Muhammad’s encounter with Bahira, a Christian monk, who recognises him as the messiah when the young Muhammad is travelling with his uncle in Syria. This is perhaps legendary, appearing in only two books of the Hadith, but its function in a film designed to have a multi-faith application is obvious.

There is a much lengthier narrative line about a Jewish merchant often trading in Mecca. Witnessing the light that appeared in the sky on the night of Muhammad’s birth and, disbelieving that the saviour he has been awaiting can be born outside of the Jewish faith, he begins a long search. After years of searching, the merchant recognises Muhammad when he witnesses a miracle—Muhammad, intercepting a human sacrifice performed to propitiate the gods of the sea, causes fish to be thrown from the sea onto the shore for the starving people.

Figure 22: An image of a scene from the film Muhammad, The Messenger of God, Majīd Majīdī, 2010.

The miracle is a particularly interesting addition. While Muhammad’s miracles do include the multiplication of food, this seems more aligned to the loaves and fish miracle performed by Jesus, while also recalling a visually striking scene in Majīdī’s Song of the Sparrows (Āvāz-i gunjishk-hā, 2008), where the young children spill hundreds of goldfish on a pavement. Moreover, Majīdī features other incidents with animals in Muhammad. The 105th Meccan Surah of the Quran describes the unsuccessful attack on the Quraysh, the Arab merchant tribe (into which Muhammad was born) which controlled Mecca, by Abrahah al-Ashram, Christian viceroy of Yemen. His war elephants refused to enter Mecca. The extreme low angle shots employed by Storaro to film this sequence very dramatically capture the huge elephant feet, particularly after Abrahah has fallen from his elephant to the ground. Abrahah’s final defeat, delivered by a swarm of barn swallows pelting his army with stones, is achieved through special effects and supported by equally dramatic music. There were difficulties finding a location to shoot the elephant scene. India refused permission for fear of upsetting its Muslim population, but finally South Africa was used. Elsewhere there is a fictional incident involving a camel that escapes being slaughtered by running amok till it reaches the house where the baby Muhammad is resting.

Figure 23: An image of a scene from the film Muhammad, The Messenger of God, Majīd Majīdī, 2010.

Despite the epic scope of the film, Majīdī still manages a number of beautiful metaphorical scenes that bring an occasional lightness of touch. Exemplary is one where Muhammad’s gown catches on a bush. Storaro makes the most of the light in a spectacular shot and music draws our attention to this as a significant moment. As Muhammad detaches the thread of his gown from the bush a host of seeds are released, floating through the air, some kind of metaphor for Muhammad’s teachings, and reminiscent of scenes in other Majīdī films, perhaps the famous ending of Bārān (2001), where the departing beloved’s footprint is washed away by the rain.

An aspect worth mentioning is Majīdī’s deliberately careful representation of women, to underscore his stated aim to show “what Islam is about.” In what seems like a quiet rebuke to the opening scene of Ja‛far Panāhī’s The Circle (Dāyirah, 2000), a character very early in Muhammad states, “The holy prophet said, ‘An infant girl is a heavenly door opened before you. Her birth is an auspicious occasion.’” The representation of Muhammad’s mother and his wet-nurse, in line with Iranian Islamic values, foregrounds their self-sacrificing natures as mothers.

What the film does share with The Kingdom of Solomon is the condemnation of the worship of objects and idols. Where that film condemned Zoroastrian fire worship, in Muhammed there is a scene where the pre-Islamic gods of Mecca literally crash to the ground. Later a pagan healer is called to attend to Muhammad’s dying Bedouin wetnurse. When he arrives, he removes the amulets from her body—signs of superstition—before restoring her to health, inducing great fearfulness among those present.

Majīdī had given much thought to the language issue and in 2013 was already trying to determine how to launch the film internationally. His expressed intention was to create Urdu and Arabic dubbed versions, as well as sub-titled versions for the Western market.39Majīd Majīdī (director) in an interview with the author, February 2014. This indicates clearly how he saw the production—for the Muslim world it would be an accessible spiritual/religious piece; for the West a major spiritual arthouse production which would inform western audiences about Islam. It has subsequently been subtitled in English and dubbed into a number of languages.

Domestic box office receipts totalled 70 billion rials (about US$2 million) in the first month of Muhammad’s release in Iran. Anecdotally, the film is not considered to have been a box office success, and possibly the same strategy used with the Magnificent Productions, the purchase and distribution of tickets by government departments, was employed. The film screened in Lebanon (where Shiites constitute 7% of the population) and Turkey (where Shiites constitute 16.5%), where according to Box Office Mojo it took nearly US$1.5 million. Aside from its Montreal premiere, it was shortlisted for the Asia Pacific Screen Awards in 2015. However, the film remained controversial—in late 2018 the International Film Festival of Kerala was refused permission for a single screening of the film in a festival context and in the presence of the director. There has been no recent mention of the two sequels which were discussed in earlier pre-release publicity.

Conclusion

In 2002 Agnes Devictor had written that “the main goal of the IRIB’s policy on cinema [was] neither artistic nor economic, but rather the achievement of an ideological project.”40Agnes Devictor, “Classic Tools, Original Goals: Cinema and Public Policy in the Islamic Republic of Iran (1979–97).” in The New Iranian Cinema: Politics, Representation and Identity, ed. Richard Tapper (London: Taurus 2002), 66. Under the previous president, Muhammad Khātamī, there had been a lesser emphasis on the ideological and an attempt to align cinema with audience taste. Comparatively, the new policies and strategies behind decision-making relating to cinema under Ahmadīnizhād’s presidency, particularly during its second term, were apparent through both the presidency’s rhetoric and events. Along with the increased constraints on filmmakers, they showed a marked return to the ideological project of Muslim filmmaking, with the Magnificent Productions a key strategy. This new initiative for funding of bigger-budget films that were in line with the government’s cultural diplomacy aims and that might compete domestically with international blockbusters and unacceptable films, however, was short lived. The strong thread of historical subject matter running through most of these productions suggests a desire to create definitive popular versions of Iranian history both near and far. In terms of content there was a dominance of history in the new category of the Magnificent Productions, most of which assert themselves as having a non-fiction basis while providing an emphatically Iranian/Muslim point of view of world events.

Cite this article

During Mahmūd Ahmadīnizhād’s second presidential term (3 August 2005-3 August 2013), the government placed an emphasis on re-harnessing the film industry to its goals. One (little known) strategy was the funding of a small slate of films known as the “Fīlm-i Fākhir,” translated best as “the magnificent productions,” but also suited to the term “Islamic blockbusters.” This entry investigates the films, their content, their reception, and how they conform to what the government desired and to government policy.