Film Production at Kānūn-i Parvarish-i Fikrī

Introduction

Non-fiction, sponsored, institutional, and children’s films are integral to the history of Iranian cinema. Iran, like other developing economies in the post-World War II order, was eager to invest in documentary film as a means of communication, education, and promotion of state agendas. Cinema was an exemplary object of modernity, and thus an ideal medium through which to construct new social worlds. Iran’s midcentury production of “useful cinema”1Charles R. Acland and Haidee Wasson, Useful Cinema (Durham N.C.: Duke University Press, 2011). was vast and varied, ranging from dull statist visions to avant-garde interpretations of societal change. These non-fiction films provide a valuable lens through which to understand the Iranian national imaginary. Many of Iran’s best-known filmmakers, such as ‛Abbās Kīyārustamī, began their filmmaking careers making sponsored and non-fiction films. Further, many sponsored and non-fiction films made in the 1960s and 1970s influenced the form of the Iranian New Wave and post-revolutionary art cinema. A focus on institutions illuminates film history and political history together.

This article considers the film output from an institute for children’s media, Kānūn-i Parvarish-i Fikrī. Films produced by Kānūn, such as Davandah [The Runner] (1984), Khānah-yi dūst kujāst [Where is the Friend’s House?] (1987), and Bachah-hā-yi Āsimān [Children of Heaven] (1997),2Davandah [The Runner], directed by Amīr Nādirī (Tehran, Iran: Kānūn-i Parvarish-i Fikrī, 1984); Khānah-yi dūst kujāst [Where is the Friend’s House?], directed by ‛Abbās Kīyārustamī (Tehran, Iran: Kānūn-i Parvarish-i Fikrī, 1984); Bacha-hā-yi Āsimān [Children of Heaven], directed by Majīd Majīdī (Tehran, Iran: Kānūn-i Parvarish-i Fikrī, 1997). stand as some of the most significant and influential works of Iranian cinema. How did Kānūn come to play such a valuable role in Iran’s cinematic history? What factors motivated film production decisions at the institute? To address these questions, this article begins by contextualizing Kānūn within a broader history of sponsored film production in Iran. Initially, Kānūn focused on literary pursuits, but soon founded a film department. Here, I focus primarily on its first decade of film production. Even in these early years, filmmakers at Kānūn produced a diverse body of work, which can be broadly categorized as realist, modernist, or experimental. An examination of the institute’s bureaucracy and structure sheds light on the emergence of these aesthetic modes. The Islamic Revolution of 1979 resulted in sweeping and fundamental changes in governance, and this extended to film production too, though Kānūn remained a prolific and vital production house through the 1990s.

Figure 1: Logo of Kānūn-i Parvarish-i Fikrī (Center for the Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults, 1965), designed by Muhamad Pūlādī.

Sponsored Film in Iran

Iran’s earliest moving pictures are actualities (short non-fiction films) from the court of Muzaffar al-Din Shah. The Shah had ordered court photographer Sanī‛ al-Saltanah to buy two film cameras and film stock while they were traveling through Europe in 1900. The first of these actualities was likely Jashn-i Gulhā (1900), in which al-Saltanah documented Belgian women tossing floral bouquets at the Shah.3Hamid Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema. Volume 1, the Artisanal Era, 1897-1941 (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 2011).The Iranian state would go on to invest more heavily in film—particularly as pedagogical media—in future decades. Reza Pahlavi’s modernization reforms paved a path for the state’s involvement in film production, distribution, and exhibition. The Pahlavi state codified cinema through regulations that governed film distribution and exhibition in the 1930s. This ensured the exhibition of non-fiction films such as newsreels, scientific films, and industrial films. Further, the code both governed children’s ability to see appropriate films and advocated for the screening of educational films in schools.4olbarg Rekabtalaei, “Cinematic Governmentality: Cinema and Education in Modern Iran, 1900s–1930s,” International Journal of Middle East Studies 50, no. 2 (2018): 247-269. These regulations set a precedent for the state’s use of film as a pedagogical tool.

In 1964, Pahlavi’s son, Muhammad Reza Pahlavi, established the Ministry of Culture and Arts (MCA). This organization oversaw all arts production and exhibition in the country. Mihrdād Pahlbud, a member of the royal family, was appointed to run the ministry. He had previously been the head of the Fine Arts Administration, which had housed Iran’s first documentary production unit. During the 1960s, there was a proliferation of government institutions related to arts administration, and many began to sponsor film production with an eye towards social reform and societal modernization. Other film-sponsoring organizations included the National Iranian Oil Company (NIOC), a consortium in which Iran had a majority ownership (foreign oil companies owned shares of it as well); The Red Lion and Sun Society; as well as similar aid, relief, and care organizations. Thus, initially there was no single centralized film production unit, but rather, various interlinked agencies and institutes that were either entirely under state control or received funding, training, or material resources from the state.

Founding the Film Department at Kānūn

This article focuses on influential film production at an institute dedicated to children’s media and culture. Kānūn, or the Center for the Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults, was a nominally independent institution but was entirely funded by state agencies. Lily Amīr-Arjumand had the idea of creating a children’s library and publishing house after seeing similar institutions in European countries. Her childhood friend, Farah Pahlavi, the Queen of Iran, entrusted Amīr-Arjumand first to head the National Iranian Oil Company Library in 1959, and then to found Kānūn in 1965. (In between, Amīr-Arjumand trained as a librarian at Rutgers University in the United States.) According to Farshīd Misqālī, a graphic designer and animator who worked for the center, funds for the organization were determined by board members from the Ministry of Art and Culture, the Ministry of Education, the national airline (Iran Air), the Interior Ministry, the Oil Ministry, the Pahlavi Foundation, and National Radio and Television. Queen Farah Pahlavi led the board of trustees. Misqālī also states that “Board members supported Kānūn through their affiliated organizations,”5Arash Sadeghi, “Institute for the Intellectual Development of Children & Young Adults,” Bidoun 16 (Winter 2009), retrieved 29/08/2024, https://www.bidoun.org/articles/institute-for-the-intellectual-development-of-children-young-adults indicating additional flows of support for the institution. In the same interview, Misqālī says that filmmaker ‛Abbās Kīyārustamī—who, at the time, was a commercial artist—recommended that Kānūn establish a film department. The organization launched this department in 1970 and Ibrāhīm Furūzish became its first director. The department also produced animation films.

Figure 2: Grand opening of a Kānūn-i Parvaresh library with Muhammad Reza Shah Pahlavi and Farah Pahlavi (1965). accessed via https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:KanunShah.jpg

Festivals and Exhibition

Even in its earlier years, the organization was involved in film exhibition: it hosted an international festival of children’s films, with entries from the Soviet Union and the National Film Board of Canada. The International Festival of Films for Children and Young Adults was very popular, running from 1966 until 1977. It was also influential, helping to circulate the best of international film and animation to young Iranians, and providing a platform for nascent Iranian talent.

Kānūn’s exhibition venues for their films included cinemas, schools, state-run film festivals, film clubs, and other institutions. However, they were primarily exhibited in their own libraries, which functioned as local cultural centers. In its first decade, Kānūn established 150 libraries in Iran, in both urban and rural areas; after the Islamic Revolution, this number would rise to over three hundred. These libraries soon expanded to include infrastructure and space for film screenings, theatre, and other cultural activities. Kānūn also provided mobile cinemas and traveling theatre so that they could reach children in more rural and remote parts of the country.

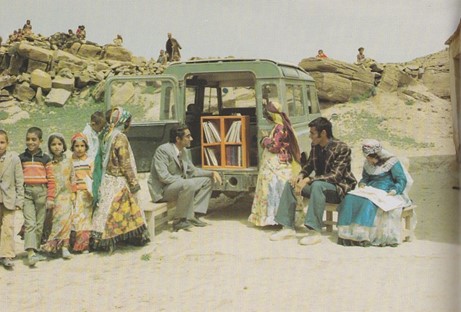

Figure 3: A photo of a mobile library taken in Kurdistan province (1970). accessed via https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:MobLib.jpg

Filmmakers, Genres, Aesthetics

Kānūn’s first films included animations by Misgālī and live-action short films by Kīyārustamī, Muhammad Rizā Aslānī, and Bahrām Bayzāʾī. Indeed, these and several other prominent Iranian filmmakers began their film careers at Kānūn. Associated filmmakers include Suhrāb Shāhīd-Sālis, Amīr Nādirī, Nūr al-Dīn Zarrīnkilk, who is considered the father of Iranian animation.

In Kānūn’s first decade, these filmmakers produced a plenitude of notable, influential, and beloved films. This initial run of production ended with the Iranian Revolution in 1979. After that, the Islamic government imposed a new set of rules to govern film production. These rules advocated for an Islamic “purification” of cinema, in which women on screen were to be veiled at all times. The depiction of physical intimacy was restricted, and rules interfered with how men and women in the cast and crew could interact with one another. However, these restrictions helped to shape a golden age of film production for and about children in the 1980s and 1990s. Filmmakers had more freedom in storytelling about pre-pubescent children, who were not subject to the same regulations. In both periods, Kānūn’s films circulated abroad at festivals, garnering international publicity for the country’s cinema more broadly.

Ibrāhīm Furūzish states that Kānūn’s cinematic stories were told “through the eyes of an ordinary person.”6Kānūn, directed by Khātirah Khudā’ī (2016). Live-action films articulated this through documentary and neorealist aesthetics. Animated films brought a magical realist lens to Iranian history, mythology, and the natural world. Broadly, the first decade of Kānūn productions can be divided into four categories: scientific and educational films; films based on literary or historical sources (poetry, religious texts, mythology); animation (often fantastic or surrealist); and films representing everyday life. There was a general sense among those involved with Kānūn that Iranian children’s media should edify the viewer. As such, these four film types sometimes intersected with another overarching category: the moral tale. Many Kānūn films—operating in diverse genres and formats—demonstrated examples of good behavior, and often illustrated the consequences of poor behavior too.

Kānūn’s live-action films deviated from the “official style” of the state-sponsored non-fiction film. This style defined the dominant strain of film production at the Ministry of Culture and Arts and National Iranian Radio and Television (NIRT). It emerged as a result of training and filmmaking practices under the United States Information Service, which ran a documentary unit in Iran in the 1950s. The official style was characterized by discrete stories told in linear fashion. Their statist ideology (which was pro-modernization and syncretist) was made legible through voiceover narration.7Hamid Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema. Volume 2, the Industrializing Years, 1941-1979. (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 2011).

In contrast, Kānūn films often combined modernist experimentation with social realism. Hamid Naficy uses the term “poetic realism” to describe Iran’s state-sponsored artistic documentaries made prior to the Revolution. He writes that this mode is defined by “various lyrical and symbolic uses of indirection, by contrapuntal strategies of sound and editing, and by poetic narration.”8Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema. Volume 2, 76. “Poetic realism” built on movements in postwar European cinema. In particular, Italian neorealism (which tended to feature more child-centric stories than other art cinema) had a notable impact. Films such as Vittorio de Sica’s Ladri di biciclette [Bicycle Thieves] (1948),9Ladri di biciclette [Bicycle Thieves], directed by Vittoria de Sica (Rome, Italy: Produzioni De Sica, 1948). for example, told minor stories of everyday life without conventional dramatic urgency—particularly in comparison to popular cinema’s fanciful melodramas. Kānūn’s film practitioners also wished to avoid the sensational aesthetics and narrative modes of Iranian mainstream cinema, fīlmfārsī. Furthermore, many Kānūn artists had studied various arts in Europe: for example, animator Nūr al-Dīn Zarrīnkilk studied at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Belgium and performing arts polymath Nosrat Karimi studied at the Academy of Arts in Prague and later worked with de Sica in Rome. Many of them returned with the urge to infuse Iranian cinema with the aesthetic influences acquired through European training and exposure to foreign films.

Social Realism

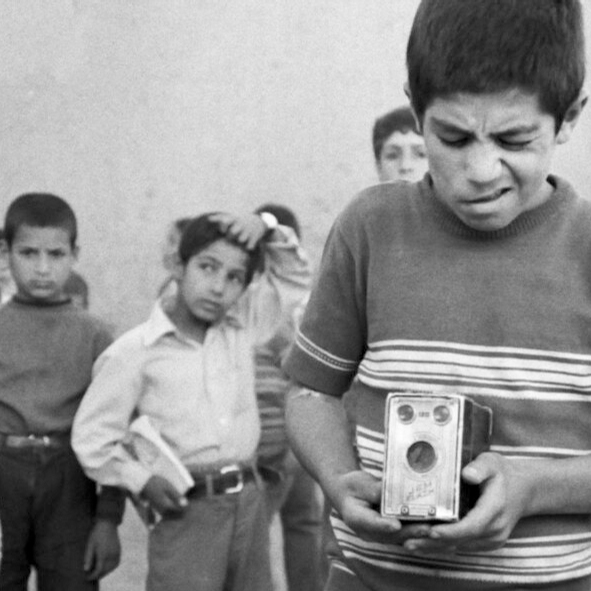

Social realist films echoed cinematic conventions of global postwar cinema. These films had simple subjects, often focusing on marginalized members of society. They were shot on location (rather than in a studio), used natural light, and employed untrained actors. Qualities of social realism formed the basis for many Kānūn films. Nān u kūchah [Bread and Alley],10Nān u kūchah [Bread and Alley], directed by ‛Abbās Kīyārustamī (Tehran, Iran: Kānūn-i Parvarish-i Fikrī, 1970). directed by ‛Abbās Kīyārustamī is widely considered Kānūn’s first live-action film. Nān u kūchah features several of the formal characteristics that populated Kānūn films. In black and white, it features an untrained child actor and is shot on location in Tehran. It eschews any traditional plot or story, focusing instead on a minor moment in a boy’s daily routine. In the film, a young boy carries a sheet of bread, kicking a ball of paper down narrow alleys on his way home. The child is startled by a barking dog who begins to follow him. Frightened, he tries to evade the dog. He tags behind an elderly man, hoping for protection. Ultimately, he must face the dog, and throws him a piece of bread. The dog then joins him as a companion and the two continue their walk. Kīyārustamī spends a considerable amount of time in close-up on the boy’s face, his sweat and anxiety clearly visible to the viewer. This focus on children’s interiority and respect for their seemingly mundane problems shone through in many Kānūn productions both pre- and post-revolution, as evinced by films such as Ibrāhīm Furūzish’s Kilīd [The Key] (1987) and Majīd Majīdī’s globally acclaimed Bachah-hā-yi Āsimān [Children of Heaven] (1997).11Kilīd [The Key], directed by Ibrāhīm Furūzish (Tehran, Iran: Kānūn-i Parvarish-i Fikrī, 1987); Bachah-hā-yi Āsimān [Children of Heaven], directed by Majīd Majīdī (1997).

Other early Kānūn films evinced a more overtly political commitment to social realism. Safar [The Journey]12Safar [The Journey], directed by Bahrām Bayzā’ī (Tehran, Iran: Kānūn-i Parvarish-i Fikrī, 1972). was the celebrated playwright Bahrām Bayzāʾī’s second film. (His first, the comical ‛Amū Sībīlū [Uncle Moustache]13‛Amū Sībīlū [Uncle Moustache], directed by Bahrām Bayzāʾī (Tehran, Iran: Kānūn-i Parvarish-i Fikrī, 1971). from 1971, was also made for Kānūn.) Safar presents two young brothers who face harsh urban conditions while in search of their father. Bayzāʾī shows the impoverished boys moving through Tehran’s upcoming developments and the dust and rubble of poorer and older parts of the city. This critical perspective on modernization contradicts the bright and cheerful symbols of modernity seen in other state-sponsored films, such as new buildings, cars, clothes, and signs.

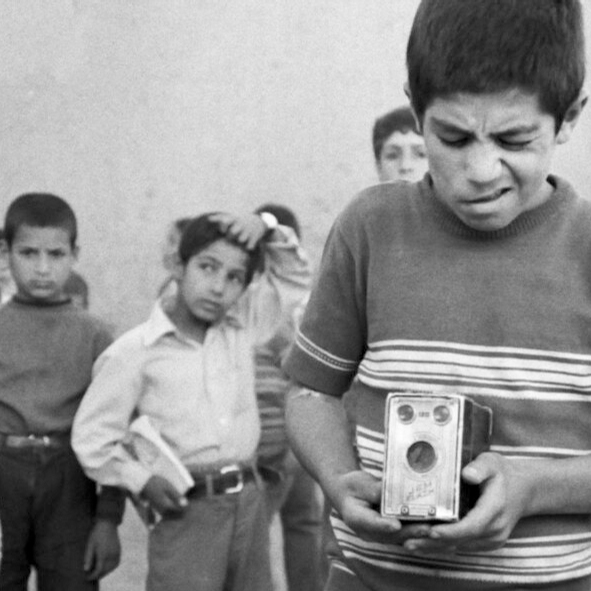

Figure 4: A still from Nān u kūchah (Bread and Alley, 1970). ‛Abbās Kīyārustamī, accessed via https://www.aparat.com/v/pf475 (00:07:48).

Modernism

Some Kānūn films displayed a formal complexity that distinguished them entirely from any popular or mainstream cinematic mode. I define these as modernist because they are characterized by a heightened formalism, responding to (and striving to make sense of) emergent conditions and structures of modernity. As filmmaker Muhammad Rizā Aslānī says, citing European art cinema as an influence, “we made modern films that children could not understand very well.”14Kānūn. directed by Khātirah Khudā’ī (2016).

Tehran’s rapid development created the context and backdrop for Kānūn’s modernist films. Qualities such as abstraction, non-linear editing, contrapuntal sound, and self-reflexivity were present in several films by Kīyārustamī and would later become signatures of his post-revolutionary cinema. Bi tartīb yā bidūn-i tartīb [Orderly or Disorderly], from 1981, is an exemplar of this mode, while also functioning as a light-hearted pedagogical film.15Bi tartīb yā bidūn-i tartīb [Orderly or Disorderly], directed by ‛Abbās Kīyārustamī (Tehran, Iran: Kānūn-i Parvarish-i Fikrī, 1981). The film presents two versions each of four scenarios. In three of these scenarios, schoolchildren must organize themselves neatly within a particular space: descending stairs, boarding a bus, or drinking from the school water canteen. The fourth and longest scenario brings an aerial view to a traffic intersection with crossing pedestrians and vehicles. Kīyārustamī shows us the orderly and disorderly version of each of these scenarios. The film is structured by a voiceover conversation between Kīyārustamī and a colleague. They discuss the scenarios, their editing decisions, and the point of the film. Furthermore, each sequence is separated by a shot of a director calling takes with his clapboard (“Sound! Camera!”). This was one of several Kānūn films by Kīyārustamī which, in some sense, documented its own production, moving between the diegetic world of the film and its construction.

In Bi tartīb yā bidūn-i tartīb, Kīyārustamī foregrounds editing to structure and restructure space and time, and aerial photography in particular presents an image of how spaces of modernity are ordered and organized (for example, by stoplights, road signs, and markings), and simultaneously, how they might be confounded by local interferences. The film reinforces technology’s organizational power by making technology visible in its form and signals the advanced modernity of the Iranian state and its institutions. In a sense, Bi tartīb yā bidūn-i tartīb (and other films) engage in a mimetic mode of pedagogy for urban social life. The film thus provides audiences with a visual and spatial understanding of urban modernity and how it might be negotiated. While Kīyārustamī imbues his interpretation of modern life with a sly sense of humor, his film aligns with the ambitions of the statist documentary.16I expand on this argument in Simran Bhalla, “Modern Time: Abbas Kiarostami’s Immersions, from Sponsored Documentary to Slow Cinema,” JCMS: Journal of Cinema and Media Studies 61, no. 3 (2022): 160–66.

Didacticism in children’s media is not unique to Iran. However, Kānūn films were produced in a historical context where society placed high value on, and expectation for, parental education of children. Parvarish, or moral education, began at home (rather than at school). Parents were responsible for the psychological health of their children.17Cyrus Schayegh, Who Is Knowledgeable, Is Strong: Science, Class, and the Formation of Modern Iranian Society, 1900-1950 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009), 172. Simultaneously, Muhammad Reza Pahlavi’s technocratic state saw a role for itself in guiding modern and civic education for both children and adults. Without overstating the influence of top-down modernization programs within this historical context, Kānūn films emerged in a fertile social and political environment for pedagogical children’s media. Kānūn’s libraries provided a social and educational space outside of school for children and their parents, and the films themselves explored themes of childhood and family, communicating norms and ideals to audiences.

Other realist and modernist18This article uses the term realism in the same sense as postwar realist cinema, and the term modernism for films that use editing, sound, and other cinematic techniques to depart from realist modes of representation. However, the two are often rightly understood as inextricable from one another, and often intersect in their representations and negotiations of modernity. films focused on life outside the metropolis, showcasing rural and regional traditions and social formations. For example, Amīr Nādirī’s Intizār [Waiting] (1974)19Intizār [Waiting], directed by Amīr Nādirī (Tehran, Iran: Kānūn-i Parvarish-i Fikrī, 1974). Waiting was filmed in Bushehr. Nādirī himself grew up in Abadan, a poor port city in southwestern Iran, which is also the site of major oil refineries. takes place in southern Iran, which was an uncommon location for fiction films of the period. A young boy is tasked with picking up ice cubes from a wealthy neighbor. He waits for the neighbor’s hands to emerge from her carved wooden door with fetishistic pleasure. The film, which is nearly without dialogue, follows him as he makes his way through the town. He quietly observes acts of prayer, ritual sacrifice, and mourning ceremonies. He joins the mourning ceremony, an outlet for his inhibited emotions. (The call to prayer and ‛Āshūrā chants are the only voiced words in the film.) At home, he bathes, helps his mother to prepare food, and interacts with local cats and pigeons. Nādirī lingers on hands, bodies, and breathing in close-up. His focus on local Shi’ite rituals and bodily response is rare for a state-sponsored fiction film of this period. The film is also unusual in its ambiguity and reserve in terms of its perspective on children’s behavior: it has no instructional aspect, nor does it model clearly moral actions. Lastly, by eschewing a more urban, industrialized location, it avoids even incidental representations of technology and development—though the film leaves open the question of how the ice is made.

Figure 5: A still from Intizār (Waiting, 1974). Amīr Nādirī, accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jGeZQ5wqMZw (00:07:04).

Experimental and Animated Films

Animated film in Iran also emerged under state-sponsorship. Filmmakers, invigorated by the possibilities and liberatory potential of animation strategies, experimented with graphic and surrealist abstraction. These more experimental and avant-garde films included animations such as Murtizā Mumayyiz’s Yik nughtah-yi sabz [A Green Dot], and Suhrāb Shāhīd-Sālis’s pixilated Sīyāh-u sifīd [Black and White], both from 1972.20Yik nughtah-yi sabz [A Green Dot], directed by Murtizā Mumayyiz (Tehran, Iran: Kānūn-i Parvarish-i Fikrī, 1972); Sīyāh-u sifīd [Black and White], directed by Suhrāb Shāhīd-Sālis (Tehran, Iran: Kānūn-i Parvarish-i Fikrī, 1972). Each filmmaker brought their expertise and interest in other art forms to the practice of film animation and experimental techniques. Mumayyiz was a renowned graphic designer who, like other Kānūn employees, had worked in commercial design and advertising before bringing his talents to the institute. In Yik nughtah-yi sabz, he controls shifting lines and dots, disrupting recognizable shapes and symbols with random movement. Shāhīd-Sālis, meanwhile, began his career in sponsored non-fiction films after studying abroad in Austria and France. He directed four short ethnographic films about regional dances for the Ministry of Culture and Arts before Sīyāh-u sifīd, his sole film for Kānūn. Sīyāh-u sifīd takes place on a set designed to look like a white cube, with actors dressed as mimes in all-black or all-white. It features two fathers and their sons fighting over a striped ball. Like Mumayyiz, Shāhīd-Sālis is more interested in the artificial mechanics of motion he can generate than any story aspect. It is his most playful and comic film in a career of reserved and lonesome works. However, it presages the aesthetic minimalism and austerity that would define his feature-length films.

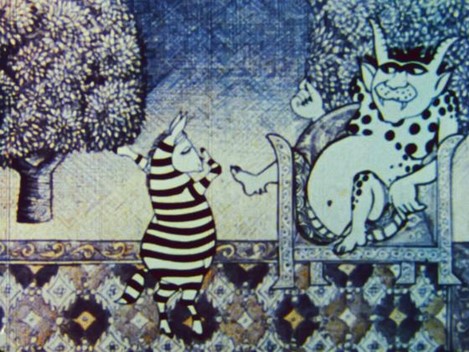

Several Kānūn animators (such as ‛Alī Akbar Sādiqī) also drew on Iranian artistic traditions such as the miniature and Qahvah-khānah painting for their animations, illustrations, and designs. In his film work, Sadeghi is noted for elegant animations of stories from the Shahnameh. Similarly, the acclaimed Nūr al-Dīn Zarrīnkilk drew on Persian carpet motifs for animations such as Amīr Hamzah-yi Dildār va Gūr-i Dilgīr (Amir Hamzeh and Onager, 1977). Zarrīnkilk has a diverse animation style, from the irreverent citation of American symbols such as cowboys, Charlie Chaplin, guns, and the Statue of Liberty in Tadā‛ī [Association of Ideas] (1973) to the whimsical mix of influences on display in the gentle watercolor A Playground for Baboush (1971).21Amir Hamzeh and the Onager, directed by Nūr al-Dīn Zarrīnkilk (Tehran, Iran: Kānūn-i Parvarish-i Fikrī, 1977); Tadā‛ī [Association of Ideas], directed by Nūr al-Dīn Zarrīnkilk (Tehran, Iran: Kānūn-i Parvarish-i Fikrī, 1973); A Playground for Baboush, directed by Nūr al-Dīn Zarrīnkilk (Tehran, Iran: Kānūn-i Parvarish-i Fikrī, 1971).

Figure 6: A still from Amir Hamzeh and the Onager (1977). Nūr al-Dīn Zarrīnkilk, accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Jm6N4hQqx3Y (00:05:46).

Figure 7: Poster for Sīyāh-u sifīd (Black and White, 1972). Suhrāb Shāhīd-Sālis.

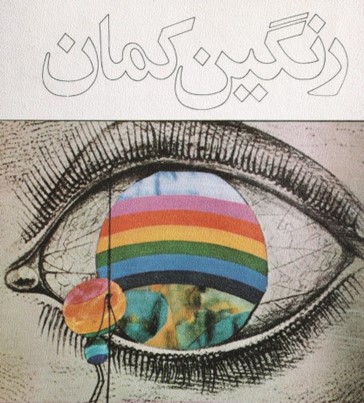

Lastly, while filmmaking at Kānūn was male-dominated, Nafīsah Rīyāhī directed her first animations there, becoming Iran’s first female animator.22While women filmmakers were few and far between in Kānūn’s first decade, the institute did employ women in other prominent roles. Beyond Amīr-Arjumand, this included the composer Shaydā Gharachahdāghī and singer-composer Sīmīn Gadīrī. One of her notable works is Rangīnkamān [Rainbow] (1973), a surrealist cartoon which features a rainbow creature moving through a fantastic landscape.23Rangīnkamān [Rainbow], directed by Nafīsah Rīyāhī (Tehran, Iran: Kānūn-i Parvarish-i Fikrī, 1973). The creature helps seed roses from concrete, and watched a worm consume a giant apple and then transform into a butterfly. Some of Rīyāhī’s imagery, such as the large green apple, seems influenced by Belgian surrealist painter René Magritte. The creature paints a rainbow in a painting of an eye, which resembles Magritte’s artwork The False Mirror (1928) and paints a rainbow-colored visage of Charlie Chaplin over the blank face of a man in a bowler hat, evoking Magritte’s The Son of Man (1946).

Figure 8: Poster for Rangīnkamān (Rainbow, 1973). Nafīsah Rīyāhī.

Figure 9: A still from Rangīnkamān (Rainbow, 1973). Nafīsah Rīyāhī, accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6u87_zLMV8k (00:01:44).

Organizational Structure: Leadership, Funding, and Oversight

A significant number of filmmakers who began their careers in Kānūn’s first decade went on to shape Iranian cinema. They helped build the Iranian New Wave, contributed to Iranian exile and diasporic arts, and brought global audiences to Iranian cinema. Yet their achievements must be contextualized within Kānūn’s bureaucratic structure, which itself was impacted by shifting distributions of political power. Detailing the “state” and adjacent figures involved in state sponsorship reveals a confluence of factors that helped create an exceptional environment at Kānūn in this early period. As Ibrāhīm Furūzish attests, “freedom in both content and production […] led to the establishment of an avant-garde.”24Kānūn, directed by Khātirah Khudā’ī (2016).

This freedom came from generosity in both funding and oversight for Kānūn productions. The head of Kānūn, Lily Amīr-Arjumand, was a close confidante of Iran’s queen, Farah Pahlavi. Pahlavi—who had trained as an architect in France—helped spearhead and direct many of the country’s cultural institutions, appointing loyal friends and family members with shared sensibilities to positions of power. Her bureau and the institutions she helped establish and sustain were funded by petrodollars, which ensured financial liquidity for the Iranian state. A gendered division of power gave her purview over Iran’s state-sponsored cultural realm, while her husband (who was reportedly disinterested in film and fine arts) managed “masculine” spheres such as the nation’s military and economy.25Farshid Emami, “Urbanism of Grandiosity: Planning a New Urban Centre for Tehran (1973–76),” International Journal of Islamic Architecture 3, no. 1 (2014): 69-102. For more on Farah Pahlavi’s artistic ambitions relating to state planning, see Shima Mohajeri, “Louis Kahn’s Silent Space of Critique in Tehran, 1973–74,” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 74, no. 4 (2015).

In addition to Amīr-Arjumand, Pahlavi hired her cousin Kāmrān Dībā, an artist and architect, to build several significant structures including the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art, which he also ran. Her other cousin, Rizā Qutbī, ran National Iranian Radio and Television (NIRT). Farrukh Ghaffārī, the son of a prominent diplomat, was a significant figure in Iranian cinema. He founded an influential film club (the National Iranian Film Center) in Tehran and was selected by Dībā to organize the annual Shiraz Arts Festival, among other activities.26Hamid Naficy writes about nepotism and cronyism in state-sponsored film and cultural production during this period in A Social History of Iranian Cinema. Volume 2. Furthermore, nearly every major filmmaker involved with Kānūn received some training or education in the West, with a few notable exceptions (such as ‛Abbās Kīyārustamī).27In addition to those mentioned previously, other employees of Kānūn who studied in the West (before the Revolution) included Fīrūz Shīrvānlū, Murtizā Mumayyiz, Shaydā Gharachahdāghī, and Nafīsah Rīyāhī. This indicated both a particular class position and a shared set of influences and references that guided taste at the institute. Despite Kānūn’s endeavors to reach other cities and towns, it retained a “Tehran-centric gaze.”28Hamid Dabashi, An Iranian Childhood: Rethinking History and Memory (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2023) 102.

This elite network helped ensure that Kānūn’s creative projects would be produced, published, or performed, and beyond that, circulated outside of Iran. Furthermore, this “second royal court” inoculated the many leftist and dissident voices at Kānūn from censorship and harsh punishment by the state to a certain extent.29See Talinn Grigor, Building Iran: Modernism, Architecture, and National Heritage Under the Pahlavi Monarchs, (New York: Periscope Publishing, distributed by Prestel, 2009), and “A Tribute to the Legacy and Vision of Lily Amir Arjomand and Kanoon,” Asia Society, 2022, retrieved 29/08/2024, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Sj3Cv-LJCb8 Yet the gendered and mercurial nature of the monarchy’s organization meant that Farah Pahlavi’s influence was uneven, and her later statements about her cultural work are inconsistent with the ideological implications of her patronage.30Farah Pahlavi had her own organization, The Special Bureau of Her Imperial Majesty (also known as the Farah Pahlavi Foundation), through which she oversaw cultural endeavors. However, as Laylā Dībā (a curator and relative of the Queen’s) notes, “I found that Iran was full of “courts.” Everybody had their court… whether you were talking about the prince or princess or a major industrialist or a member of an old family.” So it is possible that the commentators and scholars quoted here are referencing either Pahlavi’s actual court or metaphorical court (or indeed conflating them). For more, see “Interview with Diba, Leyla,” Foundation for Iranian Studies, 1984, https://fis-iran.org/oral-history/diba-leyla/ In the first decade of her reign, Pahlavi was able to hand-select the radical writer and artist Fīrūz Shīrvānlū to help build Kānūn.31Shīrvānlū advised Pahlavi in many capacities, including in acquiring a now-famous collection of modern art for the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art. Shīrvānlū also helped found the Nīyāvarān Cultural Center and helped Pahlavi in organizing festivals and exhibitions. This was despite the fact that he had served time in prison after being convicted (as a member of the activist group Confederation of Iranian Students) in a plot to assassinate the Shah.32Sadeghi, “Institute for the Intellectual Development of Children & Young Adults.” Shīrvānlū had worked at the Franklin Book Program, a Cold War American non-profit that facilitated local publishing in developing countries, and after his time in prison, founded a graphic design studio. At Kānūn, he hired young university graduates such as Farshīd Misqālī, ‛Abbās Kīyārustamī, and Amir Naderi to work with him. Shirvanlu was given the position at Kānūn based on his experience in publishing and as the institution expanded into film production, he was able to hire his former colleagues. However, Shīrvānlū and Kānūn as a whole did court controversy. This occurred, for example, with the publication of the children’s book Māhī Sīyāh Kūchūlū [The Little Black Fish], which was seen to present an allegory of the Shah’s repressive regime.33Samad Behrangi, Māhī Sīyāh Kūchūlū [The Little Black Fish] (Tehran: Kānūn-i Parvarish-i Fikrī, 1968).

Kānūn was critiqued in this first decade for its insular administration and ideological position. Critics felt that it was a waste of state funds that did not actually produce films suitable for children. Others theorized that it kept intellectuals and dissidents occupied and placated, thus preventing them from organizing against the state. Some speculated that it was a platform for them to circulate their ideas, particularly to children. Ultimately, what was true was that Kānūn employed several notable members of Iran’s political left, and those who ran it helped prevent some of these artists and writers from being persecuted by the state for a period of time.34See Kānūn, directed by Khātirah Khudā’ī (2016); Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema. Volume 2.

Figure 10: Book cover of Māhi-e siāh-e kučulu (A little black fish, 1968), Samad Bihrangī, illustrated by Farshīd Misqālī.

Transitions Since the Islamic Revolution

After the Iranian Revolution began in 1979, Farshīd Misqālī took over from Lily Amīr-Arjumand as the director of Kānūn during a period of transition. (Amīr-Arjumand moved to the United States.) Like other cultural institutions, Kānūn found itself in a state of flux. In 1980, ‛Alīrizā Zarrīn took over as the head of Kānūn, and remained in this position until 1991. The center produced several films in the early 1980s that were temporarily or permanently banned from exhibition. However, Kānūn adapted to political change. Indeed, in some senses it was able to do so with more ease than agencies such as National Iranian Radio and Television (NIRT) and commercial film studios because its films were (at least on the surface) for and about children. Kānūn’s films thus rarely ran the risk of defying the Islamic regime’s new cinematic production codes. As Zarrīn notes, it met with easy approval from the Revolutionary Council, despite its reputation as a “Communist’s fortress.”35Kānūn, directed by Khātirah Khudā’ī (2016). After the 1980s, Kānūn became a directly state-run institution with a new board of directors.36Kānūn, directed by Khātirah Khudā’ī (2016).

Zarrīn was a good manager—particularly during a turbulent period—and also a strong producer. Kānūn’s revolutionary charter also ensured that it was not ensnared in governmental red tape, and the organization was able to create an internal production council, thus sustaining its environment of artistic freedom. Several of Kānūn’s most notable filmmakers stayed on in Iran and continued to make films with the Institute after the Revolution. This included Bahrām Bayzāʾī, Ibrāhīm Furūzish, ‛Abbās Kīyārustamī, Amīr Nādirī, Nafīsah Rīyāhī, and Nūr al-Dīn Zarrīnkilk. Kānūn’s second decade also saw the release of their milestone cinematic achievements: Nādirī’s Davandah [The Runner] (1985), Kīyārustamī’s Khānah-yi dūst kujāst [Where is the Friend’s House?] (1987), Close-Up [Nimā-yi Nazdīk] (1990), and Zindigī va dīgar hīch [And Life Goes On…] (1992), Furūzish’s Kilīd [The Key] (1987), Bayzāʾī’s Bāshū, gharībah-yi kūchak [Bashu, The Little Stranger] (1989).37Nādirī, Davandah [The Runner] (1985); Kīyārustamī, Khānah-yi dūst kujāst [Where is the Friend’s House?] (1987); Furūzish, Kilīd [The Key] (1987); Close-Up [Nimā-yi Nazdīk], directed by ‛Abbās Kīyārustamī (Tehran, Iran: Kānūn-i Parvarish-i Fikrī, 1990); Zendegi va digar hich [And Life Goes On…], directed by ‘Abbās Kīyārustamī (Tehran, Iran: Kānūn-i Parvarish-i Fikrī, 1992); Bāshū, gharībah-yi kūchak [Bashu, The Little Stranger], directed by Bahrām Bayzāʾī (Tehran, Iran: Kānūn-i Parvarish-i Fikrī, 1989). Kīyārustamī and Bayzāʾī’s films were noted for their sensitive and realist treatment of children’s experiences after the Manjīl-Rūdbar earthquake and Iran-Iraq war, respectively. Zarrīn is credited as a producer on each of these films.

According to Kīyārustamī, Zarrīn resigned after the documentary Mashq-i shab [Homework] (1989) met with censure from the Ministry of Education.38Mashq-i shab [Homework], directed by ‛Abbās Kīyārustamī (Tehran, Iran: Kānūn-i Parvarish-i Fikrī, 1989). For Kīyārustamī’s interview on the subject, see Kānūn, directed by Khātirah Khudā’ī (2016). Since then, six men have held the position of director (now termed CEO in its English translation). Kānūn continues its many activities today, including film production, though in recent decades it has focused more on children’s animated films, producing fewer documentaries and docufiction. Its films continue to be successful, circulating at major children’s film festivals worldwide. Kānūn itself hosts the Tehran Animation Festival. (The Fārābī Cinema Foundation, a major film company, has co-hosted the International Film Festival for Children and Young Adults in Isfahan since 1982, which was established after Kānūn’s original film festival came to an end. Fārābī and Kānūn have co-produced films such as Bachah-hā-yi Āsimān).39Bachah-hā-yi Āsimān [Children of Heaven], directed by Majīd Majīdī (1997). Kānūn’s changes in governance and structure since the 1990s, and resulting shifts in film production and aesthetics, can be credited both to shifts in national politics and technological transformation, with moving images being produced, distributed, and exhibited through new and ever-fluid means. Kānūn’s era of digital film production deserves further research and scholarship.

Cite this article

Kānūn-i Parvarish-i Fikrī (Center for the Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults) has played a foundational role in shaping Iranian cinema since its inception in 1965. Initially focusing on literature, Kānūn expanded into film in the 1970s, fostering the careers of influential directors like Abbas Kiarostami and Amir Naderi. Kānūn films blend modernist aesthetics with moral storytelling, often seen through the eyes of children. Despite the 1979 revolution’s cultural shifts, Kānūn adapted to new state regulations, producing internationally acclaimed works like The Runner (1984) and Children of Heaven (1997). This article explores Kānūn’s unique contribution to Iranian cinema, particularly its impact on the Iranian New Wave and post-revolutionary art cinema.