Sacred Defense Cinema: From Defense to Intervention

Introduction

Despite having ended nearly 40 years ago, the Iran-Iraq War (1980-1988) still resonates today, at the same time that some of the basic facts of the conflict are still debated. In no way forgotten, the war continues to be conjured for various political agendas, a fact reflected in Iranian media in general and most notably in Iranian films. Cinema related to the Iran-Iraq War began to be created while the war was raging and continues to the current day. It constitutes a vast body of work, some of which is officially recognized in Iran and in the scholarship as its own category or genre under the moniker of “Sacred Defense Cinema.” While the boundaries of Sacred Defense Cinema itself are also blurry and contested, some commonalities emerge from a general view. As a state endorsed phenomenon, Sacred Defense Cinema is of note for what it might reflect about the state’s cultural and political policies and challenges. This is not to say, however, that this body of work is either monolithic or always accepted by the same state institutions or constituents that support it.

Figure 1: A still from Īstādah dar Ghubār (Standing in the Dust, 2016), directed by Muhammad Husayn Mahdaviyān.

Among the hundreds of films and numerous filmmakers affiliated with Sacred Defense Cinema, several figures have received the majority of critical attention. While mostly a genre of cinema in the vein of narrative fiction, the documentarian Murtizā Āvīnī is credited for starting Sacred Defense Cinema as a school of filmmaking.1Pedram Khosronejad, “Introduction,” In Iranian Sacred Defence Cinema: Religion, Martyrdom and National Identity, ed. Pedram Khosronehad (Sean Kingston Publishing, 2012), 1-58. Ibrāhīm Hātamīkīyā is also considered a founding figure, a steadfast director on the narrative side of the genre, with almost the entirety of his oeuvre dedicated to Sacred Defense themes.2Shahab Esfandiary, “Iranian Sacred Defence Cinema and the Ambivalent Consequences of Globalization: A Study of the Films of Ebrahim Hatamikia,” In Iranian Sacred Defence Cinema: Religion, Martyrdom and National Identity, ed. Pedram Khosronejad (Sean Kingston Publishing, 2012), 59-98. Among the younger generation of filmmakers—those born during the war or later but too young to have been a part of the ideological or physical battles of wartime—Muhammad Husayn Mahdavīyān’s narrative and documentary works have broken new ground in Sacred Defense Cinema and Iranian cinema more broadly. Despite the fact that such filmmakers are well-known for their work in this genre—with the latter two receiving a fair amount of attention in the scholarship—the category Sacred Defense itself is not singularly understood by filmmakers, audiences, or even within the state. In addition, even a cursory look across more than three decades of media and cultural production identified under the category of Sacred Defense reveals a shift in accordance to political exigencies. Lastly, and surprisingly, given that most of these works have or continue to benefit from direct state sponsorship or endorsement, these films have also served as a site for critique, albeit an internal critique that positions itself on the side of the Revolution and its ideals.

Before beginning a closer examination, a clarification of terms is necessary. While these terms are sometimes used interchangeably, Iranian war cinema is not coextensive with Sacred Defense Cinema: that is, not all Iranian war cinema is Sacred Defense Cinema and not all Sacred Defense Cinema is war cinema as that category is generally understood. Whereas war films focus on actual warfare, with battle scenes typically at the center of the action, Sacred Defense Cinema has a more expansive understanding of war. While many of the films of Sacred Defense take place on the battlefield, some of the most significant films of the genre do not. Films focused on the lives of veterans, for example, allow for films that take place in all manner of locations and time periods. Indeed, the figure of the veteran permits filmmakers to present a long-passed war in the present tense. The implications of this will be further discussed below in the examination of the political uses to which these films have been put. For the purpose of the point at hand, the ways in which veterans appear in films of Sacred Defense Cinema are in fact one of the indications that Sacred Defense Cinema is not synonymous with war cinema. As Rastegar has pointed out, the concept of Sacred Defense itself

came to be applied more broadly, not only to the work exploring the aftermath of the war, but even to projects that promoted what were considered to be the ideological aims of the war, even if these had little direct bearing on the war and postwar setting.3Kamran Rastegar, Surviving Images: Cinema, War, and Cultural Memory in the Middle East (Oxford University Press, 2015), 124.

Understanding the shifting contours of Sacred Defense Cinema is central to the examinations of this article, which provides a chronological overview from wartime in the 1980s through the early 2010s. As with most accounts of Sacred Defense Cinema, this article begins with the work of the documentarian Murtizā Āvīnī and his contributions to defining the themes and styles of the emergent genre. In this early period, Āvīnī and the state were able to successfully depict a unity of aim and vision, but such assertions become increasingly difficult in post-war Iran. This article examines this fraying discourse of unity by then moving to a discussion of the genre in the 1990s. If Āvīnī is the name that dominates the non-fiction works of Sacred Defense, Ibrāhīm Hātamīkīyā is the best-known director of the narrative fiction side. Looking at his genre-defining work in this period both reflects developments in storytelling as well as cracks in the images of social and political unity presented during wartime. The post-war period enabled stories of Sacred Defense that went beyond the battlefield to examine the lives of veterans; and the ending of the war also meant that Sacred Defense need not be limited to drama: that is to say, comedy could also be a vehicle for carrying the themes of the genre. The paper next moves to the early 2000s, a relatively dull period where regional wars raged in Afghanistan and Iraq, and generational differences in Iran begin to come into greater relief as the Iran-Iraq War receded further into the past. Melodramas examining the lasting physical and psychological damage of the Iran-Iraq War, especially as it impacted younger generations, are a hallmark of the films of this period. The final section of the paper moves into the 2010s when Sacred Defense Cinema saw a revival and several innovations. New filmmakers such as Muhammad Husayn Mahdavīyān and new technologies introduced opportunities for a more action-packed cinema and experiments in the form, while the content of the films of this period reflect attempts to make a case for Iran’s domestic and foreign policies. It is this latter point that makes the Sacred Defense Cinema of this period stand out against the earlier works of the genre: while there are continuities of themes and topics from the inception of the genre that have persisted to the current day, the 2010s marks a shift toward using the language of “defense” in order to justify Iran’s interventionist actions in the region. Nonetheless, like post-war Sacred Defense Cinema, the films of the 2010s also contain internal critiques about contemporary power structures and society in Iran. These periods and what they show about Iranian cinema, state, and culture, are discussed in further detail below.

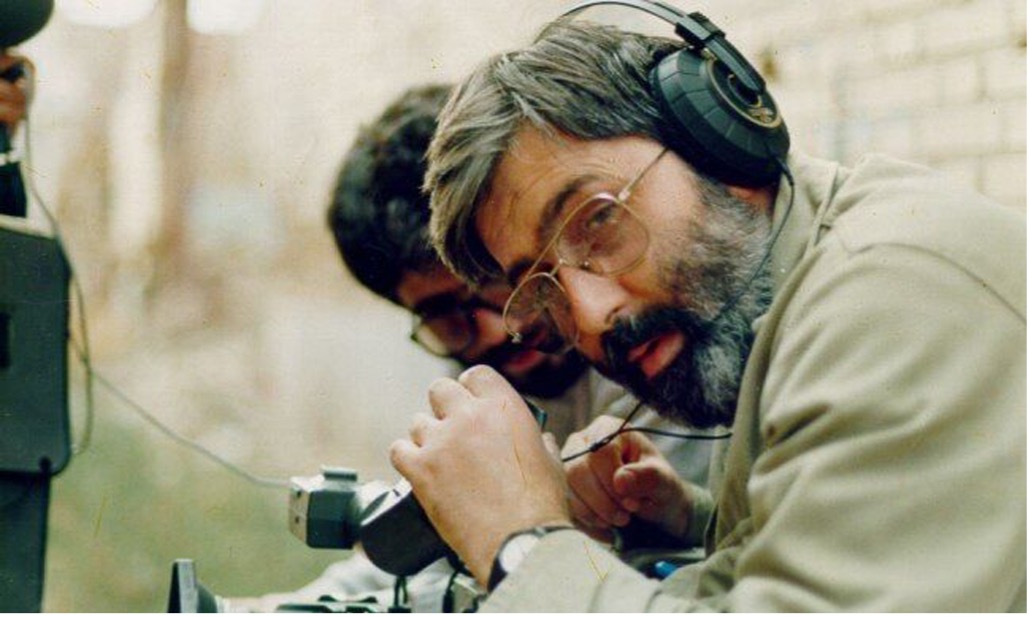

Figure 2: Murtizā Āvīnī on the filming set. accessed via https://irna.ir/xjxPnF

1980s: The Defining Years of a Genre

Perhaps the most written about work in Sacred Defense Cinema, Murtizā Āvīnī’s Ravāyat-i Fath (Chronicles of Victory, 1986-1994), also bears the least similarity to the vast body of work that has subsequently been produced under the umbrella of the genre. Organized into chapters, the sixty-three-episode documentary series is an innovation in form. At times experimental and even poetic with dramatic voice-over narration, it includes extensive footage of the battleground as well as interviews with soldiers, their families, and ordinary people. Production and distribution of the series on state television, however, did not begin until 1986.

Āvīnī’s innovation of a new style was imbricated with an explicit ideology which viewed martyrdom as the “highest degree of human elevation” 4Mehrzad Karimabadi, “Manifesto of Martyrdom: Similarities and Differences Between Avini’s Ravaayat-e Fath [Chronicles of Victory] and More Traditional Manifestoes,” Iranian Studies 44, no. 3 (2011): 383. and claimed the distinctiveness of the Iran-Iraq conflict as a “sacred war.”5Khosronejad, “Introduction.” 14. The series highlighted the selfless and pious defense of the country by the Basīj6The Basīj, established on April 30, 1980, began as an auxiliary military unit composed of everyday citizens which was later employed as part of the front-line forces during the Iran-Iraq War. The term can be translated as “the mobilization,” and while Basīj refers to the entire force, a basījī refers to a single member of the group. volunteers and Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC), and emphasized the war as a conflict that was imposed on the country. Both of these premises aligned directly with the newly formed state’s own rhetoric about the war. Considering himself a seeker of truth rather than deception, Āvīnī did not understand himself to be a propagandist.7Karimabadi, “Manifesto of Martyrdom: Similarities and Differences Between Avini’s Ravaayat-e Fath [Chronicles of Victory] and More Traditional Manifestoes,” 383. Yet Āvīnī was highly selective in editing and he chose his interview subjects so that he could tell a very specific story about the war.8Roxanne Varzi, Warring Souls: Youth, Media, and Martyrdom in Post-Revolutionary Iran (Duke University Press, 2006). The focus on the IRGC at the expense of the army and its role is one of the most obvious indications of this. Thus, contrary to his claims about the search for hidden meaning, there is much that Āvīnī’s work actively hides. The result is a body of work that depicts the war as singular and spiritual, encouraging the audience to support the war effort, and by extension, the state that was leading it.

Works of narrative fiction were also important in setting the standards and image of unity in this period. Like Āvīnī, Hātamīkīyā believed in the uniqueness of the Iran-Iraq War and the experience of brotherhood on the frontlines, and these early films attempted to depict that singularity. As Shahab Esfandiary has noted, “Hatamikia’s two groundbreaking films, The Scout and The Immigrant are largely credited with setting the standards and defining the terms of the Sacred Defence genre in Iranian Cinema.”9Esfandiary, “Iranian Sacred Defence Cinema and the Ambivalent Consequences of Globalization: A Study of the Films of Ebrahim Hatamikia,” 63. Inspired by a true story, Dīdahbān (The Scout, 1989) covers the final few hours in the life of ‛Ārifī, a watchman who is surrounded on the frontlines by Iraqi forces. Signaling his comrades with his walkie-talkie to help them identify his location and thereby the location of the Iraqis, ‛Ārifī sacrifices himself so that the Iranians can bomb the site and be saved from certain death. Hātamīkīyā’s next film, Muhājir (The Immigrant, 1990), is similarly about the self-sacrifice of its protagonist. This time the technology at the center of the film is not a walkie-talkie but a small reconnaissance drone named “The Immigrant.” Stationed at two different locations, the film’s two main characters, pilots Asad and Mahmūd, work together in guiding the drone with the aim of destroying an important target. In the end, Asad, who has infiltrated enemy territory, manages to safely hand over the drone and ensure the success of the mission, but this comes at the cost of his own life.

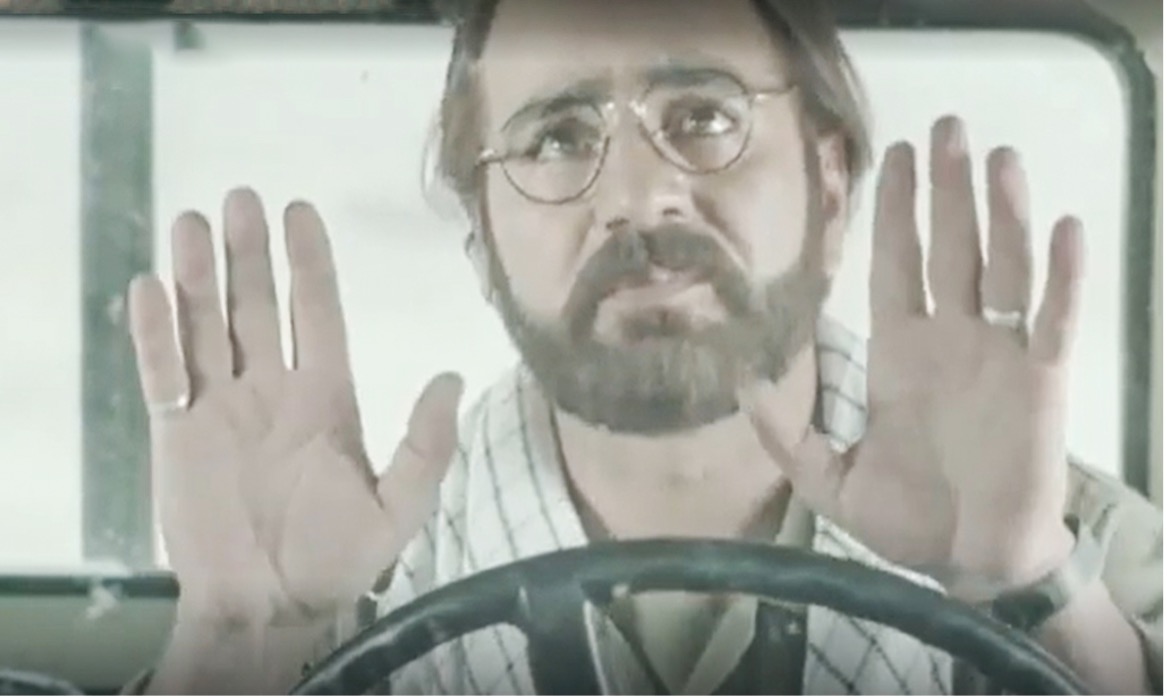

Figure 3: ‛Ālī guiding the drone from enemy territory. Muhājir (The Immigrant, 1990), Ibrāhīm Hātamīkīyā, accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rQMRhHk7FmU (01:24:18).

If in the years since the war’s conclusion the internal tensions around the conflict continue to be revealed, in the midst of the war, it was relatively easy for the state to create and maintain a facade of unity—both in terms of its own rhetoric as well as the cultural productions it supported. The dominance of state broadcasting and the lack of alternate choices for a war-shocked populace, a revolutionary state unifying its forces against an external enemy, and media talent who believed in the state endorsed ideology were all important factors in the ability to craft and present clear messaging about the war. Broadcast on the Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting (IRIB) Channel 1 on Thursday nights at 8:00 PM, Āvīnī’s Chronicles of Victory was able to reach a vast audience and had a central role in crafting a monoculture concerning the war. However, this period of relative harmony was short lived, and the cracks in the Sacred Defense narrative and the political system it buttressed became particularly evident after the war ended and Sacred Defense films moved off of the battlefield. Even Hātamīkīyā, whose films The Scout and The Immigrant were key to defining the contours of narrative fiction in the emerging genre of Sacred Defense, would soon depart from a singular focus on the battlefield, instead largely depicting veterans as a vehicle for probing social and political issues related to the war and beyond.

The 1990s: Beyond the Battlefield: Explorations in Narrative and Genre

Whereas Āvīnī’s name is synonymous with the documentary style of Sacred Defense, his contemporary Ibrāhīm Hātamīkīyā is the dominant name on the narrative fiction side. The familiar themes of ideological purity and sacrifice have remained a mainstay in his works, yet Hātamīkīyā has also broken new ground in Sacred Defense Cinema both in formal terms and regarding the issues broached in his films. Unlike his contemporary Āvīnī, who died when he stepped on an unexploded mine while filming on a former battlefield in 1993, Hātamīkīyā has lived to see the numerous internal crises that have befallen the Iranian state since the end of the Iran-Iraq War, and has been a prolific filmmaker during this entire period. It is impossible to know for sure if Āvīnī would turn against the Iranian state or the ideals of the revolution, but many of his contemporaries have in fact become harsh critics of or outright oppositional toward the regime.10Muhsin Makhmalbāf is perhaps the most notable director whose filmmaking and political views have drastically shifted over the years. His 1989 film, Arūsī-yi khūbān (Marriage of the Blessed), for example, still appears in many “best of” lists of Sacred Defense Cinema. Makhmalbāf left Iran in 2005, and “he became not only a dissident filmmaker but also a political dissident in the aftermath of the 2009 presidential election.” See, Elżbieta Wiącek. “Transnational Dimensions of Iranian Cinema: ‘Accented Films’ by Mohsen Makhmalbaf.” Studia Migracyjne-Przegląd Polonijny 46, no. 3 (177) (2020): 61. Hātamīkīyā, for his part, has remained a steadfast supporter of revolutionary ideals while consistently offering a critical view on how those ideals are not being realized. As such, his films are an instructive case study for examining how the films of Sacred Defense have functioned as sites for both bolstering and critiquing state ideologies.

In the early 1990s, the conflict was still fresh enough for audiences and directors alike to have a visceral sense of the Iran-Iraq War experience, but enough time had passed to allow for critical reflections on the war and its aftermath to emerge. This also meant an expansion of narrative possibilities for Sacred Defense Cinema. More stories could be told off the battlefield, and soldiers no longer were required to represent the majority of characters, which in turn meant there were more ways in which to incorporate women into such narratives. As Esfandiary has pointed out, all of these elements would become evident in Hātamīkīyā’s work in the 1990s, with Az Karkhah tā Rhine (From Karkheh to Rhine, 1993) indicating a “substantial shift, both in Hatamikia’s professional career and within the wider Sacred Defence genre framework.”11Esfandiary, “Iranian Sacred Defence Cinema and the Ambivalent Consequences of Globalization: A Study of the Films of Ebrahim Hatamikia,” 70. Furthermore, Sacred Defense films begin to incorporate references to contemporary regional developments in their narratives, often in the form of documentary footage, such as Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait shown in From Karkheh to Rhine, or the toppling of Saddam’s statue in Mullāqulīpūr’s Mīm misl-i mādar (M for Mother, 2006) which I discuss in a later section.

Figure 4: Doctor removing the bandage from Sa‛īd’s eye after surgery in a hospital in Germany. Az Karkhah tā Rhine (From Karkhe to Rhine, 1993), Ibrāhīm Hātamīkīyā, accessed via https://www.aparat.com/v/f6570w6 (00:33:47).

A recurring theme in Sacred Defense cinema is Saddam’s use of chemical weapons and their long-term consequences. For instance, Hātamīkīyā’s Karkheh to Rhine centers on Sa‛īd, a veteran and chemical weapons victim who travels to Germany for eye surgery. Although he regains his sight at the hands of a German surgeon, he is soon diagnosed with leukemia caused by his exposure to chemical gas and dies before being able to return to Iran. At this point in his filmmaking, Hātamīkīyā’s depiction of the state’s treatment of its veterans is largely positive. After all, Sa‛īd is not the only veteran in the German hospital; there are many others that appear to have been sent there on the government’s dime and for whom additional provisions such as translators are provided. The same cannot be said for the depiction of the veterans themselves, however, marking a quiet but important shift in the claims of unity of purpose and purity of heart that had largely dominated Sacred Defense Cinema. For instance, the film’s condemnation of an unlikeable veteran who decides to apply for asylum is one such example that demonstrates a rift in the depiction of the state’s treatment of veterans vs. the quality or character of the veterans themselves.

Figure 5: Sa‛īd is inside the CT scan machine. Az Karkhah tā Rhine (From Karkheh to Rhine, 1993), Ibrāhīm Hātamīkīyā, accessed via https://www.aparat.com/v/f6570w6 (01:21:44).

Figure 6: Saʿīd’s memories and scenes from the war flash before him with every movement of the machine. Az Karkhah tā Rhine (From Karkheh to Rhine, 1993), Ibrāhīm Hātamīkīyā, accessed via https://www.aparat.com/v/f6570w6 (01:22:25).

Sa‛īd’s sister Laylā, who for reasons not disclosed to the audience is alienated from her family and her past and resides in Germany, also figures in the film. While Sa‛īd dies in Germany without achieving his wish to return to his homeland, his death prompts Laylā to reconsider her relationship to the past and return to Iran at the film’s conclusion. Sa‛īd’s wife also appears at the end of the film with her newborn: Sa‛īd calls her “doctor” and the audience learns that she married him despite his blindness. Whether or not she met him while caring for him medically is unclear, but her status in society and her compassion is indicated by these two pieces of information. Though not exactly at the center of the narrative, both women are part of the storyline and are granted dimensions that go beyond the battlefield. With the further passage of time, women become increasingly incorporated as focal points of Sacred Defense films, such as the protagonists of M for Mother (2006), discussed further below, or Vīlā’ī-hā (The Villa Dwellers, 2017), which was directed by a woman: Munīr Qaydī.

As mentioned earlier, From Karkheh to Rhine engages contemporary developments by incorporating documentary footage of Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait. The use of the footage alongside the film’s emphasis on the damage suffered by Iranian victims of chemical weapons underscores the “defense” element of the Sacred Defense genre while also indirectly condemning a world that not only tolerated but also helped Saddam in his attacks on Iran. In the one rare instance where the Germans are treated with hostility in the film, an Iranian veteran answers a reporter’s question about the war with a retort about how Iranians should be the ones interrogating the Germans about the chemical weapons sold to Iraq. Other than this, however, all of the Germans appearing in the film—the doctors, the police, the priest, and Laylā’s husband—are depicted positively. In fact, after his sight is restored at the hands of a German surgeon, Sa‛īd says that he was born twice: once in Iran and again in Germany. Given that this was the first post-revolution film to be made abroad, Esfandiary notes that Hātamīkīyā had to work with locals and he speculates that this accounts for the film’s more nuanced depiction of the West.12Esfandiary, “Iranian Sacred Defence Cinema and the Ambivalent Consequences of Globalization: A Study of the Films of Ebrahim Hatamikia,” 70.

In addition to enabling the elements discussed above, such as an increase in the number and variety of roles for women, some nuance in the depiction of erstwhile soldiers and their views, as well as engagement with contemporary political developments and their connections to the conflict, the end of the war also allowed the possibility of genre exploration. While Mas‛ūd Dihnamakī’s 2007 film Ikhrājī-hā (Outcasts) has received much attention for its humorous approach to the war, it was Kamāl Tabrīzī’s film Laylī bā man ast (Leili is with Me) which broke new ground in 1996 by making the first comedy about the conflict. The plot centers around Sādiq Mishkīnī, a cameraman with financial troubles who needs money to complete construction on his half-built home. The state-run television station offers loans to employees, and in order to secure one, Sādiq accompanies Kamālī, a reporter, to film Iraqi prisoners of war. The comic core of the film lies in Sādiq’s numerous thwarted attempts to avoid the frontlines, each of which get him closer to rather than further from them. Sādiq’s duplicity is also the source of humor: while he presents himself as a pious warrior whose only wish is to get to the frontlines as quickly as possible, he shows his true self in asides to God as he bargains to be saved from the war and in his direct address to the camera about his situation.

Figure 7: Sādiq praying for a safe return from the war front line. Laylī bā man ast (Leili is with Me, 1996), Kamāl Tabrīzī, accessed via https://www.aparat.com/v/2lZd4 (01:19:33)

This sort of comedic style and the breaking of the fourth wall were major departures from the formal features of documentary and narrative Sacred Defense Cinema created thus far. In comparison, both Āvīnī and Hātamīkīyā did experiment in their storytelling; in the case of Āvīnī, it can be seen in the use of both poetic and dramatic narration, and with Hātamīkīyā, it is evident in his use of flashbacks which would become a hallmark of his style. Yet their experimentation is done with extreme seriousness about the war and the medium of film. In going the comic route where the anti-hero-turned-hero occasionally addresses the audience directly, Leili is with Me treats the medium and subject with a never before seen levity. Nonetheless, it is still in essence a Sacred Defense film insofar as it propagates key ideas about the nature of the war and those who fought in it.

Some of these elements can be seen through Sādiq’s interactions with his fellows on the frontlines. For instance, throughout his journey to avoid the front, Sādiq meets all manner of basījī fighters, including his loan officer and contractor, who are surprised and repentant that they had not judged him as someone who would go to the frontlines. One character he meets more than once is a handsome young man who is desperate to go to the frontlines but is being prevented from doing so by his commander who insists that he return home for his wedding. The range of fighters Sādiq meets—young and old, with a range of accents indicating they have come from many regions of the country, dedicated to the cause, pious, and brotherly—are all familiar archetypes in the work of Sacred Defense Cinema. Many of his encounters with the basījī are imbued with humor, but the sense of the seriousness of the cause and the genuineness of the fighters remain. For example, when the young man yearning to go to the front against his commander’s orders gets hit with shrapnel, Sādiq’s screaming over-reaction aims at garnering laughs; at the same time, it is played against the steady and brave reaction of the basījī who has been hit.

Figure 8: A young man gets shot, and Sādiq screams in fear. Laylī bā man ast (Leili is with Me, 1996), Kamāl Tabrīzī, accessed via https://www.aparat.com/v/2lZd4 (01:01:42).

Furthermore, the film is in essence a conversion narrative, and though the conversion does not happen until the very last ten minutes of the film, it concludes with the protagonist waking up in the hospital with a genuine desire to return to the frontlines. In the entirety of the film, Sādiq’s duplicity brings into relief the authenticity of everyone else. With the exception of the reporter Kamālī, who turns out to have also been putting on an act and simply going to the front because of the job he was assigned, every other person is there to contribute to the cause according to his ability, including an old man who is there to shine the shoes of fighters since he can do nothing else.

Perhaps the best wrap-up to 1990s Sacred Defense films is to return to where this examination began, with Hātamīkīyā, and specifically with what is arguably the most explosive and widely seen film of Sacred Defense Cinema in this period: Hātamīkīyā’s Āzhāns-i Shīshah’ī (The Glass Agency, 1998). The film’s theme and structure mirrors Sidney Lumet’s Dog Day Afternoon (1975), but instead of robbing a bank to pay for a partner’s sex-change operation, the protagonist in The Glass Agency, war veteran Hāj Kāzim, is attempting to secure tickets from a travel agency so that his fellow veteran ‛Abbās may receive urgently needed treatment abroad for a life-threatening war injury. Hāj Kāzim had sold his car to buy the tickets for ‛Abbās’ trip, but when the buyer fails to bring the money in time to the travel agency, Hāj Kāzim asks the agency’s owner if he can put his car up for collateral. The owner refuses, and angered, Hāj Kāzim takes the weapon of a guard. Thus, like Lumet’s film, the circumstance in The Glass Agency escalates into a hostage situation. The film then takes a turn, pitting veterans against veterans. Two other comrades of Hāj Kāzim and ‛Abbās join their side, while another two enter the scene as members of the state security services. Importantly, one of the representatives of the security forces was a comrade of Hāj Kāzim’s on the frontline. In the end, after a long night and the failure of hostage negotiations, Hāj Kāzim prepares to kill the first hostage when they are successfully raided. Yet two plot twists remain: first, executing an order from high ranking authorities a helicopter arrives to take ‛Abbās and Hāj Kāzim to the airport; second, just when it seems that the film may have a happy ending, ‛Abbās dies in the air while the plane is still above Iran.

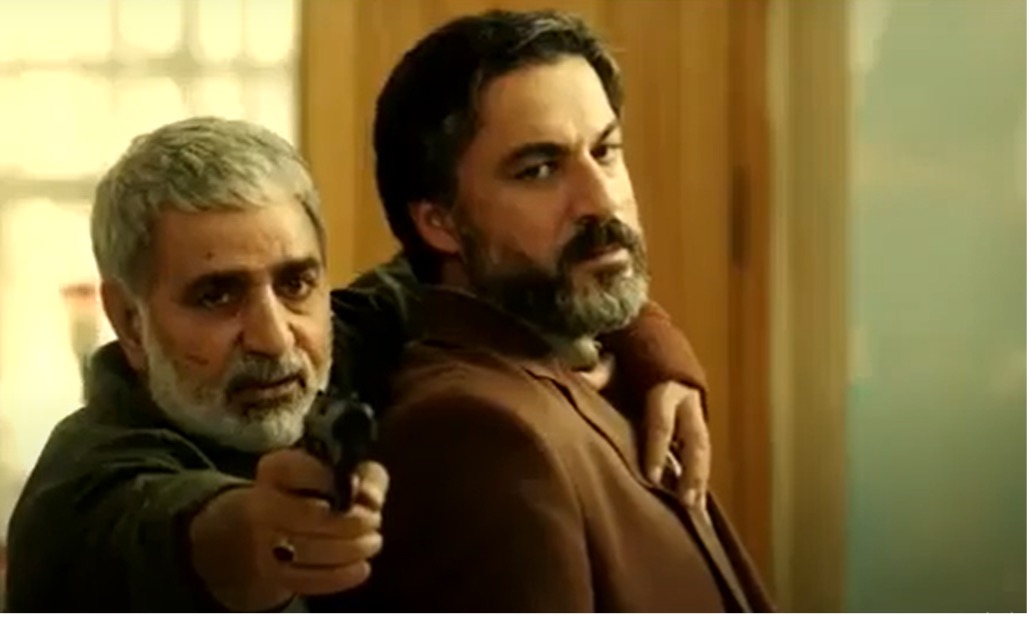

Figure 9: Two officers enter the agency to talk and negotiate with Hāj Kāzim. Āzhāns-i Shīshah’ī (The Glass Agency, 1998), Ibrāhīm Hātamīkīyā, accessed via https://www.aparat.com/v/m453767 (01:11:06).

What was indicated with more nuance in From Karkheh to Rhine about the tensions among veterans, as well as the difficulties faced by individual veterans, becomes explosively evident in The Glass Agency. As Ahmadi has noted,

By 1993, in From Karkheh to Rhine, it is apparent that Hatamikia’s Islamo-Iranian subject struggled for their existence in peacetime Iran. Either cast aside or alienated by society, Hatamikia portrayed the basiji as perpetually doomed to act out rather than work through his trauma.13Shahrzad Ahmadi, “The Basiji Must Die.” Film International 16, no. 1 (2018): 8.

In short, Hātamīkīyā is drawing attention to how quickly the once celebrated fighters have either been forgotten, or worse yet, become objects of contempt. In The Glass Agency, for example, “by using the term ‘witnesses’ to refer to the hostages in the travel agency, Kāzim wants the people to witness the suffering of ‛Abbās and to remember this forgotten generation.”14Shahab Esfandiary, Iranian Cinema and Globalization: National, Transnational, and Islamic Dimensions (Intellect Books, 2012), 167. In so doing, Hāj Kāzim is trying to explain his actions to the hostages themselves. Yet his attempts to justify his actions and connect with the hostages is futile, further underscoring the distance between the veteran and society at large. Hātamīkīyā’s unvarnished depictions of the reality of peacetime Iran for veterans and the cracks within Iranian society gained him praise and drew in a large audience.

Overall, there was a strong output of Sacred Defense films in the 1990s. Depictions on and off the battlefield experimented with narrative, genre, and form, took on serious political and social issues, and began to show the fissures and disagreements within society, even among veterans and the state’s core supporters. The momentum of popular and critically acclaimed (albeit sometimes controversial) Sacred Defense films of this period, however, would not last.

The Early 2000s: Melodrama During Times of Regional Wars

In contrast to the late 1990s and what the genre would see in the second decade of the new millennium, the aughts were a relatively dull period for Sacred Defense Cinema. Indeed, as Kamran Rastegar has pointed out, there was official acknowledgement of the downturn in the genre as early as Muhammad Khātamī’s first administration, with critics pointing out the opportunism and superficiality of new filmmakers in the genre and that “even the annual Sacred Defense Film Festival was canceled several times in the 2000s.”15Rastegar, Surviving Images: Cinema, War, and Cultural Memory in the Middle East, 133. In addition, the back-to-back U.S. invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq dominated world headlines and put the Iranian state in the odd position of having two of its regional enemies taken out by world powers with which it had not had diplomatic relations since 1979. Domestically, the early 2000s also saw a decline in reformist power and popularity, with a surprise election of hardliner Mahmūd Ahmadīnizhād in 2005.

While a relatively slow period in Sacred Defense productions, a few developments merit examination. In keeping with the trend that began in the early 1990s, post-war Sacred Defense directors and films expanded the ways that the war and its aftermath were incorporated into cinema. Films of this period also began to pay more attention to the generational aspect of the war and its impacts, specifically how the children of those involved in the war suffered the mental and physical costs of a conflict now long gone by. In the films of this era, neither the battlefield nor even veterans have center stage; rather it is the family and family dynamics that are a locus for examining the legacies of the war. This includes attention to the experiences of wives and mothers in ways that break the mold of the idealized mother or wife who willingly sacrifices her loved ones to the war.

Rasūl Mullāqulīpūr’s M for Mother (2006) and Ibrāhīm Hātamīkīyā’s Bi Nām-i Pidar (In the Name of the Father, 2006) are useful case studies for understanding the state of Sacred Defense Cinema in this period. Both Mullāqulīpūr and Hātamīkīyā were already established directors in the genre when these films were made. Yet the two films depart from both established tropes in Sacred Defense and from tendencies in their own filmmaking as directors. Indeed, it may be controversial to even claim that these films are part of the Sacred Defense oeuvre. However, the war looms large in both films, and though the moralizing of the films diverge from the usual type that may be found in Sacred Defense Cinema, the focus is not on the faith and dedication of soldiers or veterans, nor are there grand claims about unity. On the contrary, these two films expose the widening cracks within society, among the political class and veterans, and inside families. Finally, both films betray a confusion about not just the legacies of the war but also what filmmaking about that legacy looks like almost two decades after its conclusion.

M for Mother was Mullāqulīpūr’s last completed film before he died suddenly of a heart attack while making his final film, which also dealt with war themes. Significantly, M for Mother begins with a dedication to “all mothers,” immediately signaling a reach beyond the mothers of martyrs. The story centers on Sipīdah, a pregnant classical violinist and former nurse in the war who is currently married to a diplomat, whose marriage and life is upended when a routine screening reveals abnormalities to her pregnancy. In its nearly two hour run time, the film attempts to take up numerous social and political issues, including: a stance against abortion; commentary on the post-war generation of politicians, and diplomats in particular; the sacrifice of mothers; the active participation of religious minorities in the war effort; and the devastating impacts of Iraq’s use of chemical weapons. The latter two issues are standard tropes in Sacred Defense Cinema, but they are diluted against the backdrop of the film’s many melodramatic twists. Thus, although Mullāqulīpūr incorporates the war and its aftermath into his film, the results are mixed.16Critics inside Iran have faulted Mullāqulīpūr’s depictions of post-war urban life, characterizing them as “angry” and contrasting these films with his ability to capture the atmosphere of the battlefront in his war-centered films. Examples of such analyses can be found in Seyed Aria Ghoreishi, “Bi munāsibat-i sālgard-i ikrān-i ‘Qārch-i Sammī’ sākhtah-i Rasūl Mullāqulīpūr [On the Occasion of the Making of Mullāqulīpūr’s Poison Mushroom],” Filimo Shot, April 17, 2022, accessed 3/9/2024, http://tinyurl.com/566c8tz2

Figure 10: Sipīdah and Suhayl waiting in an illegal clinic to see a doctor for an abortion. Mīm misl-i mādar (M for Mother, 2006), Rasūl Mullāqulīpūr, accessed via https://www.aparat.com/v/d11c107 (00:21:45).

Early in the film, sitting before an accusatory panel of medical staff, a doctor asks Sipīdah when she was exposed to chemical weapons and why she didn’t seek medical advice before becoming pregnant. Her husband Suhayl refuses to acknowledge that she is a “shīmīyā’ī” (the Persian word for chemical that has become shorthand for victims suffering from chemical weapons exposure), interrupting the doctor to say that she had been fine a week after the attack. However, he soon becomes intent on forcing Sipīdah to get an abortion. Suhayl’s efforts become increasingly gruesome, first when he takes her to a dark and dirty hospital with hostile staff, and then when he injects her with some kind of medicine to induce pregnancy loss. After both attempts fail, Suhayl pressures Sipīdah to put the baby into a home for the disabled, which she also refuses, prompting Suhayl to leave Sipīdah and the baby. Suhayl is depicted as an unsympathetic character who is driven only by his selfish focus on his career and comfort. Importantly, he is a rising star of a diplomat, and as such, can be a stand-in for the film’s critique of a new political class within the state that is motivated by personal gain rather than revolutionary ideals.17The theme of self-serving individuals in positions of power was present in Mullāqulīpūr’s previous films as well. His 2000 work, Qārch-i Sammī (Poison Mushroom), for example, centers on a former war commander who now heads a construction company but whose actions have strayed far from the ideals of the war period. The film has many subplots and plot holes, but the main emphasis remains on Sipīdah’s suffering and sacrifices.

Unlike most other Sacred Defense films which center the lives of male soldiers and veterans, M for Mother’s protagonist is a woman who served and was injured in the war effort. Her sacrifices as a mother to a disabled child—who she names Sa‛īd—are the focal point of the film. Sacred Defense films—including Mullāqulīpūr’s other works—often include cross-cuts between scenes from the war and a veteran’s current life. M for Mother also uses this method, but is significant in that the flashback scenes are of the female protagonist’s service as a wartime nurse. Notably, the recurring flashbacks pertain to a notorious day in the Iran-Iraq War—June 28, 1987—when the Iraqi Air Force dropped mustard and nerve gas on several residential neighborhoods in the northwestern Iranian city of Sardasht. The film Dirakht-i Girdū (The Walnut Tree, 2019), by Muhammad Husayn Mahdavīyān whose work is addressed further below, is also structured around the consequences of the chemical attacks on this day.

Indeed, the sustained reference to Iraq’s chemical attacks on Iranians is the film’s most direct connection to Sacred Defense tropes which emphasize the injustices suffered by the Iranian populace at the hands of an invading enemy. In one of the later scenes of the film, for instance, Sipīdah’s chemical weapons-incurred illness has greatly advanced and she can barely walk on the street while television screens in the stores she is passing show the toppling of Saddam’s statue. Here the film seems to indicate that Saddam has received his comeuppance for his crimes against Iran but does so without condoning the U.S. invasion of Iraq. While there are other references to the war and its effects, such as in a subplot involving a devout Iranian Christian veteran who acts as a father figure to Sipīdah’s disabled son Sa‛īd, the film is essentially a melodrama preoccupied with the many twists and turns in Sipīdah’s life and relationships.18The film’s many dramatic terms and unconvincing plot-lines were the subject of a number of critiques inside Iran, including claims about the film’s resemblance to “Bollywood Films.” See for example, “‘Mīm misl-i Mādar’ ranj-nāmah-yi mādārān-i fadākār-i sarzamīn-i Irān ast: Guzārish-i naqd va barrasī-yi ‘Mīm misl-i Mādar’ dar Dānishgāh-i Shahīd Bihishtī [M for Mother is the Account of the Suffering of Iranian Mothers: A report on the examination and critique of the film at Shaheed Beheshti University],” Mihr News Agency, November 10, 2006, accessed 3/9/2024, http://tinyurl.com/yc85rb4n. Despite such weaknesses, the film was Iran’s official submission to the Oscars but was not selected for nomination by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.

Figure 11: Sipīdah carrying Sa‛īd, who has stopped breathing, out of the bathroom to perform CPR. Mīm misl-i mādar (M for Mother, 2006), Rasūl Mullāqulīpūr, accessed via https://www.aparat.com/v/d11c107 (01:20:06).

In the Name of the Father provides a more literal depiction of the impact of the war on younger generations who had not experienced the conflict firsthand. The film initially tells two parallel stories. The first follows Nāsir, an engineer and war veteran, who is attempting to register a mine while simultaneously pursued by the people he works for and by his wife, whose calls are going largely unanswered. The second story follows an archeological student dig on a hillside, where a student, Habībah, finds an ancient spear. The happiness of the discovery is cut short when there is an explosion, and the audience soon learns that the student who has stepped on a mine and severely damaged her foot, Habībah, is the daughter of the engineer Nāsir. The ancient spear and the contemporary mine gesture not only to the many wars fought on the same land but speak to the main theme that soon emerges in the film: that the signs and consequences of past wars never truly dissipate, and that warriors are not the only ones who pay the ongoing costs of conflict.

Figure 12: Habībah raises the ancient dagger she found to show it to her professor and classmates. Bi Nām-i Pidar (In the Name of the Father, 2006), Ibrāhīm Hātamīkīyā, accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3sH0w1sTfGc&t=156s (00:02:14).

Nearly one hour into the film it is revealed that, during the war, the Iraqis had advanced to the area of the archaeological dig site, and the mine that injured Nāsir’s daughter had been laid by him. Upon realizing this, Nāsir pleads with God to take his leg instead, crying “I am the one who fought in the war, not her! I am the one who believed, not her!”19In the Name of the Father (00:55:15-00:55:19). In a later scene, Habībah refers to herself as her father’s “bunker mate” and “comrade,” prompting Nāsir to implore her to stop using such terms and telling her that the war is long over. When she responds that the war is still ongoing, he says that perhaps it is for him, but not for her. This and other exchanges between Nāsir and Habībah, as well as a conversation he has with his wife Rāhilah, underscore the unwitting, generational, and overlapping impacts of the war: whereas for Nāsir and veterans like him the war may still not be over, they do not seem to recognize (or want to recognize) the ongoing consequences of the war for younger generations.

In an effort to save their daughter’s foot from amputation, Rāhilah and Nāsir opt for flying Habībah to Tehran for surgery, but Rāhilah suffers a heart attack in the airport before they are able to do so. They return to the local hospital where Rāhilah is saved and Habībah undergoes the operation where her foot is amputated. Two points are important to note about the ending specifically as they relate to Nāsir’s own attitude about the war and its legacy. He observes, for one, that although he lost many friends in the local hospital where his wife and daughter were operated on, the same hospital gave him his wife and daughter back. As well, in the film’s last scene, Nāsir returns to the field where he fought and where his daughter was injured to disarm any remaining mines; as he does so, he looks up to see three presumably U.S. fighter jets flying overhead.

In this way, In the Name of the Father comes full circle in acknowledging the constant state of war that has taken place in the area: it began with Habībah finding the ancient spear and then being injured by a mine, and ends with an effort to find contemporary weaponry as another war rages on. Although more subtle in this regard than M for Mother, both films reference the U.S. military involvement in the region, gesturing toward a continuity of warfare. Both films also focus on the legacy of war in terms of its negative impacts on the minds and bodies of those who fought in them and on the generations after them as well. Critic and writer Soheila Abdohosseini lamented this preoccupation with the generational differences in Hātamīkīyā’s films and the work of other filmmakers in this period, accusing them of repeating ideas that are par for the course in the accounts of “western media and those domestically who have lost their hearts to them.”20Soheila Abdolhosseini, “Nigāhī bi fīlm-i ‘Bi Nām-i Pidar’ [A Look at the Film In the Name of the Father],” Umīd-i Inqilāb, no. 371 (October 2016), accessed 3/9/2024, http://tinyurl.com/yc2vu5p7.

Indeed, it is hard to disagree with Abdohoseeini as, for the most part, Sacred Defense films of the aughts were uninspired works of cinema that neither captured critical regard nor audience attention. One exception is the earlier mentioned Outcasts (2007), in the sense that it was a crowd-pleasing comedy and a calculated attempt to attract younger audiences and to invigorate a new approach to Sacred Defense Cinema.21For more discussion of The Outcasts as a harbinger of new trends in Sacred Defense Cinema, see Narges Bajoghli, “The Outcasts: The Start of New Entertainment in Pro-Regime Filmmaking in the Islamic Republic of Iran.” In Debating the Iran-Iraq War in Contemporary Iran, ed. Narges Bajoghli and Amir Moosavi (Routledge, 2019), 59-75. As addressed in the next section, however, Iranian Sacred Defense works would soon receive a boost in funding and ideological support.

Figure 13: Habībah is in the hospital with her father visiting her. She says to her father, “Am I dreaming?” Bi Nām-i Pidar (In the Name of the Father, 2006), Ibrāhīm Hātamīkīyā, accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3sH0w1sTfGc&t=156s (00:37:18).

The 2010s and Beyond: State Struggles and the Return of Sacred Defense

In contrast to the largely lackluster and directionless cinema of the early 2000s, Sacred Defense works were reinvigorated in the second decade of the new millennium for reasons that can be traced to both domestic and regional developments. Domestically, the Islamic Republic faced its biggest legitimacy crisis following the disputed 2009 election which saw massive demonstrations that lasted for months. In reaction, the Iranian state not only unleashed its repressive arm to quell the protests but also expanded its cultural and media productions as part of a soft power initiative it called “soft war.”22The notion of “soft war” was essentially a rebrand of a longstanding policy of supporting cultural productions that ideologically serve the Iranian state’s agenda. What is significant for the purpose of the examination here is the injection of new funds and ideological fervor into pro-state cultural productions. For further exploration of the evolution of the notion of “soft war” after the 2009 Green Movement and its consequences, see: Niki Akhavan, “Social Media and the Islamic Republic.” In Social Media in Iran: Politics and Society After 2009, ed. David Faris and Babak Rahimi (State University of New York Press, 2015), 213-230. Between 2010-2014, four Iranian nuclear scientists were assassinated and one wounded on Iranian soil. December 2010 was also the start of the Arab Spring, beginning in Tunisia and spreading across the region, most importantly for Iran hitting Syria in March 2011.

Iran’s intervention to help its ally Bashar Assad began not too long after Assad’s rule was challenged, but this involvement had initially been largely downplayed or denied entirely. However, sometime in May 2013, sources in Iran began using the phrase “The Martrys Protecting the Tomb of Zeynab” as an honorific for Iranians killed in Syria as part of Iran’s involvement in the Syrian Civil war. The emergence of the “martyrs” label indicated an important shift. During the early years there were reports of Iran secretly burying those killed in battle in Syria and generally keeping a tight lid on its operations, but thereafter the state began not only to acknowledge its interventions in Syria, but to embrace and cast them as a “defense.”23Evidence that the state’s use of the language of defense in support of intervention was not merely symbolic can be found not only in the formation and recruitment for groups such as the “Protectors of the Tomb of Zeynab,” but also in the media attention given to these efforts. See for example: “Nām-nivīsī i‛zām-e nīrū-yi dāvṭalab bi Sūrīyah [Volunteers Sign Up to Be Sent to Syria],” Mashriq News, May 5, 2013, accessed 3/9/2024, https://shorturl.at/2WjLy The existing discourse and popular culture of Sacred Defense Cinema therefore served as a perfect shell for drawing in this new definition of defense that suited the state’s contemporary foreign and domestic policies.

In short, the Sacred Defense Cinema of this period must be understood in the broader context of these developments, in which the war and post-war stories function as vehicles for justifying Iran’s foreign and domestic policies. At the same time and in continuity with the late 1990s, elements of critique can be seen in the Sacred Defense films of this period, albeit internal critiques that are often in the service of settling scores. In addition, at least two other factors are relevant to understanding the Sacred Defense films of this period. One is the availability of new technologies that allow for cinematography and special effects that are better suited for depicting scenes of conflict.24In addition to examining the interconnected developments in weaponry and media technologies, Paul Virilio’s well known discussions concerning the relationship between war and technology in War and Cinema: The Logistics of Perception also point to how improvements in the cinema apparatus are better able to capture aspects of war such as the speed of bullets, the depth of battlefields, etc. See, Paul Virilio, War and Cinema: The Logistics of Perception. (Verso, 1989). The second is the emergence of new filmmakers who had no personal experience or memory of the Iran-Iraq War.

Two films from this era by filmmakers of different generations and differing filmmaking styles best illustrate the state of Sacred Defense Cinema in this period. The first is Bādīgārd (Bodyguard, 2016) by Ibrāhīm Hātamīkīyā, and the second is Īstādah dar Ghubār (Standing in the Dust, 2016), directed by Muhammad Husayn Mahdavīyān. Both of these works were released in the same year and, notably, both of these films were sponsored by the Owj Arts and Media Organization. This organization is said to have direct links to the IRGC and to have been extremely active in funding and supporting a range of media productions since 2013—from billboards opposing the nuclear deal with the U.S., to documentaries, television serials, and animations, etc. In a mission statement no longer available on its website, Owj notes that its aim is to produce art that promotes “revolutionary discourse.” It is also often explicitly clear (e.g., in the case of billboards against the nuclear deal) that work sponsored by Owj is not only engaging with current social and political developments, but promoting a particular agenda in the face of these developments.25For more information on the OWJ foundation as Iran’s main producer of politicized cultural content in the service of particular state agendas, please see, Moises Garduño García, “The Role of Sazman-e-Honari Rosanai Oax (Owj) During the ‘Maximum Pressure’ Campaign Against Iran,” In Conflict and Post-Conflict Governance in the Middle East and Africa, ed. M.A. Elayah and L.A. Lambert (Cham: Springer Nature, 2023), 19-39.

Hātamīkīyā’s Bodyguard is not a translated title: the English word “bodyguard” is the title of the film even in its Persian version. In fact, that word and concept are themselves points of contention from the outset of the film and become metaphors for a loss that the film is lamenting. The film has a cold open, in which the lead character, Haydar Zabīhī, a war veteran with shrapnel in his head, is having his eyes examined by a doctor who is asking him questions about the nature of his work as part of the process of diagnosis. In the course of this conversation, the doctor asks, “Oh you’re a bodyguard?” but Zabīhī twice repeats that he is not a bodyguard but a muhāfiz, using the Persian word for bodyguard.26The Bodyguard (00:00:55-00:01:00). The emphasis on muhāfiz and its connotation of protection/protector here and throughout the film is important for understanding the lead’s struggle and the kind of revolutionary manhood that the film depicts as slipping away. The protagonist’s inner struggle also overlaps with several external struggles, including struggles with the younger generation—with his own child and the child of a former fallen comrade—and a struggle with the state and the authorities. The film is at once depicting a crisis of the protagonist and the crisis of the state. All of these and other themes in the film—the veteran battling internally and externally with the society he lives in, the veteran with physical remnants of war wounds, the generational struggles, and the ultimate sacrifice of the protagonist—are all familiar motifs in Hātamīkīyā’s oeuvre. What is different here is the orientation the film takes in relation to Iran’s contemporary geopolitical stances and how the film uses familiar Sacred Defense tropes to make an implicit case for those policies.

Figure 14: Haydar, along with several other bodyguards, is waiting in front of Maysam’s house. Bodyguard (2016), Ibrāhīm Hātamīkīyā, accessed via https://www.aparat.com/v/JS16C (01:08:18).

The central plot is essentially as follows: Haydar Zabīhī, a veteran still suffering from the physical and psychological impacts of the war, has been a security officer for high ranking officials for many years. Early in the film, there is an assassination attempt on the VP by an ISIS-type suicide-bomber that Haydar is not able to stop. Haydar starts to have some self-doubts about his inability to stop the attack and later the authorities also cast doubt on his actions that day. He wants to quit but is re-assigned as security for a nuclear scientist who happens to be the son of his comrade killed in the Iran-Iraq War. The movie ends with an assassination attempt on the young scientist which this time Haydar stops, ultimately sacrificing his life to do so.

Between the assassinations that open and close the film, there are many instances where Haydar is ruminating about his role as a security officer for the state but also about the current circumstances of the state. Haydar understands the role of the security agent—a muhāfiz—as a protector whose actions are rooted in deep belief, unlike a bodyguard for whom it is just a job and the work is simply transactional. The centrality of the juxtaposition of a simple bodyguard as opposed to a muhāfiz becomes explicit a little over twenty-five minutes into the film when Haydar is speaking to his superior in the security services. His boss, Ashrafī, is angry with him for not writing a proper report and instead writing a self-flagellating letter about his inability to stop the attack. In this exchange, which is at once about the events that opened the film but also about bigger issues he sees with the state and its supporters, Haydar says that “We are about to become bodyguards.” When his boss says that this “era needs bodyguards” Haydar retorts that “a bodyguard is a mercenary. There is no belief behind his actions.”27The Bodyguard (00:27:49-00:27:56). In other words, Haydar views the state and its supporters as reduced to performative actions for money or position without substantive belief or commitment behind any of it. This is again evident quite late in the film when Haydar is brought to answer before an internal review concerning his actions on the day of the assassination that opens the film. Despite the fact that his immediate supervisor and the VP who was the target of the attack support him, there is a younger official who initially casts doubt on Haydar. After the VP dies of his wounds, this official brings the protagonist in for formal questioning.

Figure 15: Haydar is reconstructing the assassination attempt scene on the vice president, whom he was guarding, in the presence of an interrogator. Bodyguard (2016), Ibrāhīm Hātamīkīyā, accessed via https://www.aparat.com/v/JS16C (01:27:26).

In a tense exchange, cross-cut with scenes of Haydar getting ready for and attending the VP’s funeral as well as scenes from the initial assassination attempt, the inspector accuses him of using the VP as a human shield. Haydar’s boss becomes angry at the inspector and at Haydar for not defending himself, stating that “Haydar is from a generation who doesn’t know fear.”28The Bodyguard (1:32:03). Again, the issue of getting paid comes up, with the inspector accusing Haydar of being an unbeliever in the system. Ashrafī again defends him, but Haydar refuses to defend himself, instead stating: “I fear the day this ship gets holes in it”: an explicit warning about the broken condition of the state.

As mentioned in the earlier plot summary, the film concludes with a second assassination attempt, this time an attempt on the life of the young nuclear scientist. In keeping with how Iranian nuclear scientists have been killed in Iran, the film’s second assassination attempt is a combination of car bombs and a drive-by shooting by assassins on motorcycles. Haydar stops the car bomb on the scientist’s door by motioning him to open the door so that he can drive by with his own car and knock the door off, flipping his own car in the process. Suspecting a backup assassin may be coming, Haydar runs towards the scientist with open arms. The young scientist, thinking Haydar is coming in for a hug, opens his arms and waits for him with a big smile. But Haydar is only approaching him to protect him, and he is the one who is shot in the back by the assassins. Thus the motif of self-sacrifice is once again repeated in this Hātamīkīyā film, but notably the scene is also one of intergenerational reconciliation. The young scientist—the son of Haydar’s former comrade—does not understand what his dad died for or what his dad’s generation is all about, but finally grasps the sacredness of the endeavor due to Haydar’s sacrifice.

Figure 16: Haydar, shot in the neck while protecting Meysam in a tunnel, loses his life. Bodyguard (2016), Ibrāhīm Hātamīkīyā, accessed via https://www.aparat.com/v/JS16C (01:36:52).

Mahdavīyān’s Standing in the Dust (2016) represents another rising sub-genre of Sacred Defense Cinema in this period: the biopic and/or the recreation of notable battles, usually taking place in the early post-revolution and war period. In fact, Hātamīkīyā’s Che (2014), which depicts two days in the life of the revolutionary figure and then defense minister Mustafā Chamrān, is also a film in this sub-genre. Mahdavīyān’s film is focused on Ahmad Mutivasilīyān, a commander during the Iran-Iraq War who has been MIA since he disappeared in Lebanon in 1982. Because such films are set in the past about dead or presumably dead figures, the filmmakers do not have to deal directly with the realities and contradictions of contemporary Iran, and as such, can have an easier time in sculpting the ideal soldier. Mahdavīyān’s film does not have a plot to speak of: as a biopic in pseudo-documentary form, the director frees himself from the conventions of both plot-driven narratives and documentary standards. In addition, in this work and others, Mahdavīyān has—at least in terms of formal film techniques—forged new ground in the ways that his work blurs the boundaries of fiction and non-fiction and, in turn, the ways that the Sacred Defense story can be told.

Standing in the Dust begins with two written textual clarifications for the audience: the first stating that the actual voice of Mutivasilīyān is used and the second noting that none of the images are real. The film is honest with us at the outset about its constructedness and the ways it mixes documentary sound with fictive images. Nonetheless, the use of Mutivasilīyān’s actual voice with a mise-en-scène that carefully recreates the era the film is set in, as well as the sepia color tone the film was shot in, imbue the images with a documentary feel of watching live footage. These formal elements of the film are used to create an authentic feel to trigger a sense of nostalgia not just for those who experienced that era but also for those who were not born or were too young at the time of the actual events (the director himself was born in 1982, the year that the subject of his film disappeared). One can see in this film and in such techniques an attempt to bring in and connect the younger and “revolutionary” generations. Rather than lamenting gaps between the old and the young, Mahdavīyān is in essence using affect to influence a disaffected generation.

Figure 17: A still from Īstādah dar Ghubār (Standing in the Dust, 2016). Muhammad Husayn Mahdavīyān, accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tJwOMi3zipc&t=3392s (01:34:59).

These formal techniques for giving the setting an authentic feel extend to the depiction of the film’s hero as well. While there are many cliché moments to show the positive side of Mutivasilīyān’s character (e.g., he is nice to kids, he carries the wounded, etc.), the director also reveals the negative aspects of his personality (e.g., he fights with comrades, he can be rude and short-tempered, coming off as unpleasant even in scenes telling the story of his engagement). As noted by at least one critic of this film, this is Mahdavīyān’s special way of making the hero believable and acceptable to his audience.29Masoud Ahmadi, “Ustūrā-sāzī dar sīnimā az Qaysar tā Ahmad Mutivasilīyān [Building Myths in Cinema from Qiesar to Ahmad Mutivasilīyān,” July 6, 2019, accessed 3/9/2024, http://tinyurl.com/yvuu2pvw In other words, Mahdavīyān employs these more showy and staged scenes of what revolutionary manhood and heroism look like, but he also provides an antidote to them in the form of glimpses into the hero’s weaknesses in order to soften the audience up to accept the realistic nature of his depiction.

The combination of these heroic strengths and weaknesses reveal how Mahdavīyān’s soldier is driven by belief, is not always likeable or rational, and has a commitment to his local community, his country, and to a broader religious/ideological fight that extends beyond Iran’s borders. Still, the film leaves no doubt concerning his heroism. In this sense he is very similar to Haydar Zabīhī in Bodyguard. If Bodyguard laments this type of hero as being from a generation without fear and also a dying breed, Mahdavian’s hero is a sketch of a generation at a time when that type of heroism was on the rise, at a time when the state had an easier time making heroes of its fallen and disappeared and was not internally ridden with strife among the “revolutionary” ranks.

Mutivasilīyān disappeared in Lebanon, but Mahdavian never shows Lebanon itself. Instead, the last seven minutes in which Mutivasilīyān is seen on film are in Syria as he is leaving the Iranian embassy. The movie ends with a voice-over of Motevasselian’s sister and brothers in the present tense against the backdrop of scenes of the family mourning their disappeared brother. In this voice-over, the siblings say that they eventually went on with their lives but that their mother is still waiting and remains as impacted as ever by her son’s disappearance. The last image of the film is a shaky camera fixed on open doors before fading to text that explains all that is known of the disappearance of Mutivasilīyān and his comrades in Lebanon: “On July 5, 1982, Ahmad Mutivasilīyān was lost somewhere in history.”30Standing in the Dust (2016), 1:34:02. The door that is literally left open seems not only to indicate the lack of closure about Mutivasilīyān and his comrades, but represents the unfinished business in the region. Further, given the current context of Iranian involvement in the region and questions about why Iran is in those countries in the first place, the film makes the case that Iran’s post-revolutionary history has been tied from the outset with events outside of its borders.

To sum up, made in a period in which the state is both involved in conflicts in the surrounding region and internally fractured, both Bodyguard and Standing in the Dust can be seen as attempts to suture the past to the present through their central protagonists. These films can also be seen as attempts to connect the war generation with those that have come after. Bodyguard’s Haydar is a living symbol of the dying ideals of the revolution and the war, and his death at the end symbolically reconciles two generations but does not resolve the problem of a state crumbling from within. Standing in the Dust’s protagonist, in turn, tries to capture that ideal without being caught up in the profound cracks that have become evident in that ideal over time. Both films show a nation under threat: in Bodyguard this is revealed in the form of threats from terrorists on the border and foreign assassins in the capital; in Standing in the Dust the threat is a backwards look at a state in the midst of a full-blown war. While the films themselves do not explicitly make this argument, the threat of violence by outsiders—whether in the case of the Iran-Iraq War or in the current moment—is shown to have become central to the Iranian state’s justifications for its policies, most notably policies of domestic repression. In this sense, both films are reproducing a very familiar state argument.

Conclusion

The trajectory of Iranian state struggles domestically and the state’s global and regional tensions have accelerated in the third decade of this century, and more recent and forthcoming works of Sacred Defense must take these developments into consideration. Iran’s rivalry with Saudi Arabia and the latter’s massive investment in Persian language media, the U.S. withdrawal from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) and the inability of Iran and the U.S. to renegotiate a deal, the Iranian elite’s rapid march toward eliminating all but the most hardline elements of the state, and, perhaps most importantly, the mass demonstrations and ongoing civil disobedience campaigns that followed the death of Mahsa Amini in 2022, are among the most critical factors that will influence the shaping and understanding of Sacred Defense films of this time.

The periods covered above illustrate some of the main trends and developments roughly spanning from the early years of the Iran-Iraq War through 2016. Adequately addressing the vast body of Sacred Defense works requires a longer study, and much remains to be examined even about the films and filmmakers that were covered here. However, it is clear that Sacred Defense works have not been stagnant. This is not a comment so much on their quality but rather a statement about the shifts in the form and content of these films and what they reflect about contemporary Iranian society. More specifically, given that most of these films are beneficiaries of state support, what they show about the state’s cultural policies are also telling. While many of the Sacred Defense works of the last four decades have continued to include familiar themes such as revolutionary ideals and self-sacrifice, the appearance of unity in the state and its cultural productions could not endure following the end of the war. Since then, Sacred Defense films and filmmakers have reflected the internal tensions of the Iranian state and society and are highly revealing cultural artifacts about contemporary Iran.

Cite this article

Sacred Defense Cinema, a genre born during the Iran-Iraq War (1980–1988), has evolved to address broader ideological narratives, from wartime solidarity to critiques of post-war legacies. Through the works of directors like Murtizā Āvīnī and Ibrāhīm Hātamīkīyā, this article traces the genre’s progression across four key periods, reflecting shifts in Iranian political and cultural landscapes. Recent films extend the genre’s scope, justifying regional interventions while engaging in internal critiques of state policies. This article explores how Sacred Defense Cinema continues to serve as a powerful medium for reflecting and shaping Iranian state ideology and public discourse.