Ideological Cinema in Iran

Introduction

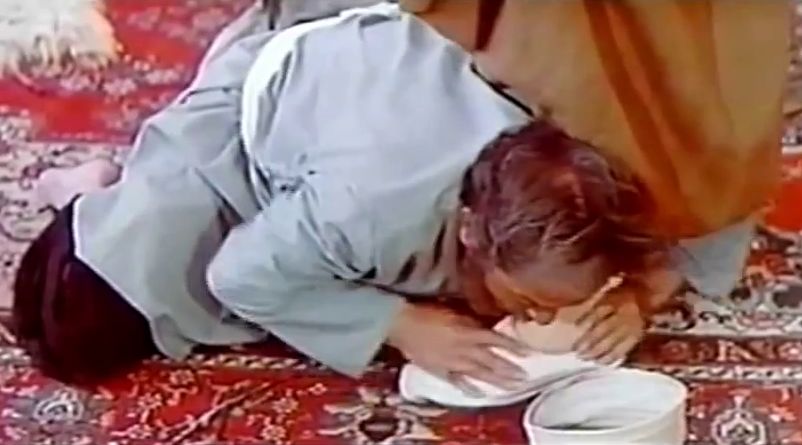

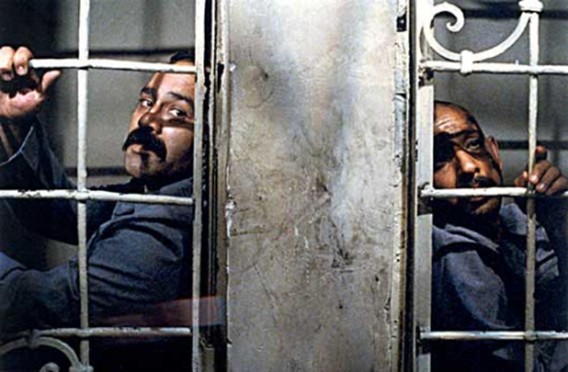

Figure 1: A still from the film Gavazn’hā (The deer), directed by Masʿūd Kīmiyā’ī, 1975.

From the mid-Qājār period in the nineteenth century, both material and immaterial aspects of the modern world began to permeate our social fabric at an accelerating rate. Meanwhile, modern thought and philosophical ideas, including new ideologies, were introduced to Iran. As Iranians became increasingly familiar with these ideologies, some were gradually drawn to them and began to promote and advocate for their adoption. Among these ideologies, Iranians embraced Marxism and nationalism more eagerly. Nationalism gained significance in the contemporary history of Iran as cultural activists from the Constitutional era and its aftermath began to contemplate the establishment of a national government. By referring to Iranian history, they sought to create national legends that could serve as reference points and provide a social glue for the unity of the country. The governments of the first and second Pahlavī eras also adopted nationalism and created the conditions necessary for its development. On the other hand, following the October Revolution of 1917 in Russia (Iran’s northern neighbor), the USSR was established on the basis of Marxist ideology and subsequently sought to export its ideology to other countries in an effort create a new world. This ideology gained widespread popularity in Iran, attracting numerous adherents and leading to the formation of several parties around it. Since ideologies generally claim to be all-encompassing systems of thought, they strive to establish a new world order based on their intellectual frameworks. Consequently, they not only seek to manage society but also propose ideas and patterns in other areas such as politics and economics. The area of culture is no exception to the influence of ideologies. Cinema is one of the most influential cultural domains in the modern world, having entered Iran during the reign of Muzaffar al-Dīn Shah Qājār. In this article, I will explore the influence of ideologies on contemporary Iranian cinema.1I wrote this article upon the suggestion of my dear friend, Dr. Yāsir Farāshāhīnizhād. I want to express my gratitude for his guidance through the writing of the article.

Thesis Statement

It is crucial to examine the imprints of ideologies in contemporary Iranian culture through the lens of the sociology of culture. This approach is particularly significant in assessing the impact these ideologies have had on Iranian culture and its cultural products, how they have shaped thoughts and ideas, the contexts they have provided for the socialization and activities of Iranians, and the direction in which they have steered social and cultural trends. Examining the impact of ideologies is an important topic in sociological research. It is crucial to determine whether these effects have emerged spontaneously from below or if they have been imposed and organized from above. It is also crucial to investigate how factors outside the cultural realm, such as political movements and governmental forces (or, as Pierre Bourdieu puts it, non-cultural fields, such as the political field),2With regard to Bourdieu’s views on how culture is shaped by political and social contexts, see Pierre Bourdieu, The field of cultural production: essays on art and literature (Columbia University Press, 1993). shape the direction of culture according to their intentions and purposes.

Artists and cultural activists have long sought the independence of the cultural sphere and the autonomy of cultural agents, especially in the modern era. On the other hand, governments and political parties have always been interested to use political forces for propaganda, to manipulate public opinion and, even further, to engage in ideological worldmaking. Political powers and especially governments in the modern era intend to control the knowledge system, shape the world’s narrative into their own advantage and deprive individuals of their cultural autonomy by means of ideological manipulations and propaganda. They prefer that people have less intellectual independence, thinking and acting within the world shaped by their own social constructs.. They are generally dissatisfied with the diversity of social and cultural sources. However, controlling public opinion depends on having pervasive power; therefore, the more the dominant power extends its influence within society, the more successful it becomes in controlling public opinion. As a result, governments aim to successfully exercise control, either directly or with the assistance of their dependent forces in other countries. The most effective means to dominate a society is to control education and socialization from within. Therefore, the more ideologies develop indirectly, through mediations and from the bottom up, the more successful and effective their proponents become. Cultural influence is the most effective means for an ideology to shape beliefs within a society. Advocates and proponents of an ideology can shape the ideological landscape through the use of cultural products. When individuals are fully immersed in an ideological framework and perceive it as their own, they are unlikely to question it. Thus, analyzing the presence and influence of ideologies in cultural products is essential, as it provides insight into the characteristics of a social world.

Ideologies shape and define historical narratives by influencing social relationships and power dynamics. Thus, it is important to understand how different ideologies have shaped contemporary Iran, how we have lived under these ideologies, and what their effects have been on our lives. Worldmaking occurs through various dimensions, each of which should be studied independently; one such dimension is the influence of ideologies on cultural products. Based on this assertion, we may inquire: How and to what extent have various ideologies manifested in Iranian cultural works and products, particularly in Iranian cinema? To what extent has cinema, as a modern medium, served to reflect various ideologies in contemporary Iran? Have these ideologies been supported solely by independent social forces, or have they also received governmental backing?

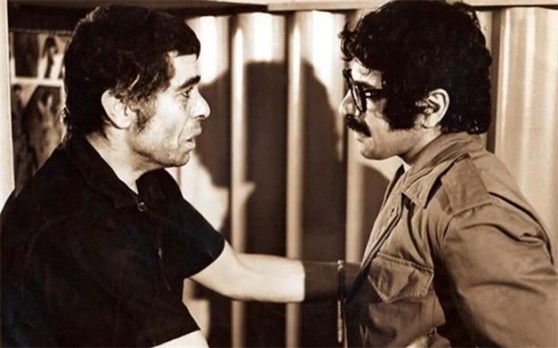

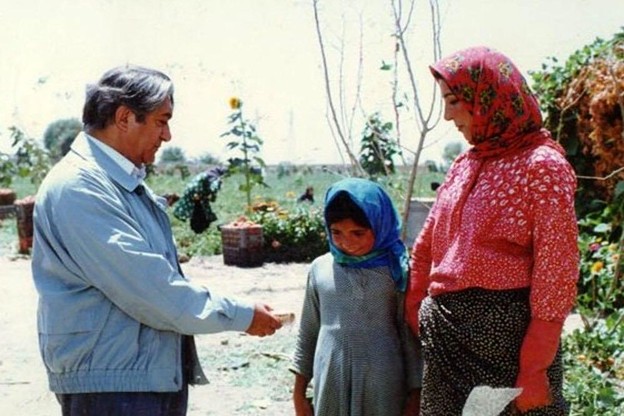

Figure 2: A still from the film Gāv (Cow), directed by Dāryūsh Mihrjū’ī’s, 1969.

Theoretical framework

Some Iranian critics display a noticeable bias in their discussions about the relationship between ideology and cinema in Iran. A number of them have sought to label many Iranian films as inherently ideological. For example, in his Sīnimā va susiyālīsm dar Īrān (Cinema and socialism in Iran),3Ahmad Zāhidī Langrūdī, Sīnimā va susiyālīsm dar Īrān [Cinema and socialism in Iran] (Tehran Nabisht, 2017). Ahmad Zāhidī Langrūdī claims to have identified socialist themes in many Iranian films. ‛Alī Asghar Kishānī identifies most films from the Pahlavī period as ideological and states: “The Pahlavī regime, influenced by the first Pahlavī’s affinity for Nazism, sought to use cinema as a tool to legitimize its governance through the ideology of nationalism.”4‛Alī Asghar Kishānī, Farāyand-i takāmul-i sīnimā-i Īrān va hukūmat-i Pahlavī [The process of interaction between Iranian cinema and Pahlavi government] 1st ed. (Tehran: Markaz-i Asnād-i Inqilāb-i Islāmī, 1386/2007), 344. Another issue in some analyses of cinema and ideology is the failure to distinguish between two types of engagement with cinematic works:

- A negative encounter that seeks to control cinema and censor cinematic works at will, eliminating anything deemed undesirable or unfavorable. There is no doubt that extensive censorship has been enforced across various domains in Iran, including cinema. As Sadr argues, from the very first years of the Pahlavī dynasty, “censorship in Iranian cinema gradually took shape and became established.”5Hamīd Rizā Sadr, Dar’āmadī bar tārīkh-i siyāsī-i sīnimā-i Īrān (1280–1380) [An introduction to the political history of Iranian cinema from 1901-2001], 1st ed. (Tehran: Nay, 2002), 27. Hamid Naficy also writes about the dominance of censorship on Iranian cinema:

During the second Pahlavi period (Mohammad Reza Shah, 1941–79), cinema flourished and became industrialized, producing at its height over ninety films a year. The state was instrumental in building the infrastructures of the cinema and television industries, and it instituted a vast apparatus of censorship and patronage. During the Second World War and its aftermath, the three major Allied powers—the United Kingdom, the United States, and the USSR—competed with each other to control what Iranians saw on movie screens. […] In the subsequent decades, two major parallel cinemas emerged: the commercial filmfarsi movies, popular with average spectators, forming the bulk of the output, and a smaller but influential cinema of dissent, the new-wave cinema.6Hamid Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema, Volume 2: The Industrializing Years, 1941–1978 (Duke University Press, 2011), xxiii.

He adds that “ironically, the state both funded and censored much of the New Wave cinema, which grew bolder in its criticism and impact as Pahlavi authoritarianism consolidated.”7Hamid Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema, Volume 2: The Industrializing Years, 1941–1978 (Duke University Press, 2011), xxiii. It should be noted that censorship in Iran encompasses various aspects and shapes and is not confined to the mere omission of a few scenes from a film.

- An affirmative encounter seeks to employ cinema and cinematic works to advance its own purposes and interests. This affirmative engagement with cinema can be classified into three categories:

- a) Using cinema and cinematic works for advertisement: All forms of media can serve advertising purposes, and the medium of cinema is no exception. Advertising is not necessarily ideological. Governments, like any other organization, engage in self-promotion. Hamid Naficy has brilliantly categorized the films made during the reign of Rizā Shāh with advertising purposes under the label “institutional and industrial films.”8Hamid Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema, Volume 1: The Artisanal Era, 1897-1941 (Duke University Press, 2011), 178.

- b) Using cinematic works to present different values and norms: In cinematic works, as in all other cultural productions, some are regarded as favorable while others are seen as unfavorable; some are embraced and celebrated, while others are rejected and disapproved of. For example, a soldier’s sacrifice for their country might be seen as heroic and honorable. In contrast, dishonesty and infidelity toward a spouse or family might be portrayed as abhorrent, while patriarchy may be presented as prominent and favorable. Individualism may be deemed as an incorrect choice. It is based on this function of the concept of ideology that some have argued for the existence of an “ideological code system” in Iranian popular cinema during a certain period.9‛Abdul-Vahhāb Shahlībar, “Sākhtār’hā-yi rivā’ī va īdi’uluzhīk-i sīnimā-i ‛Āmmah’pasand-i Īrān (1376 –1386)” [Narrative and ideologic structures of Iranian popular cinema (1997 – 2007)], Mutāliʿāt-i farhangī va Irtibātāt [Researches in culture and communications], 7, no. 25 (Winter 2011): 12.

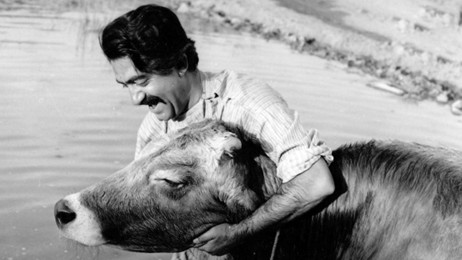

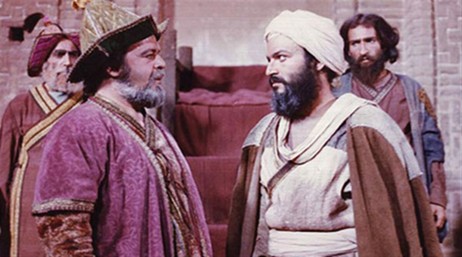

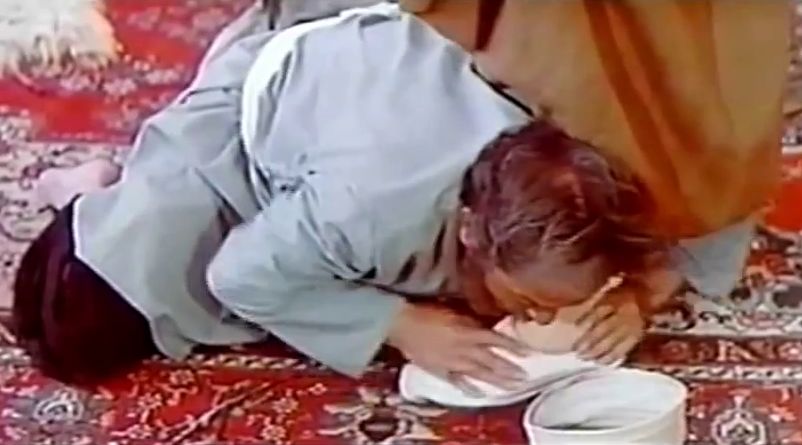

Figure 3: A still from the film Sādiq Kurdah, directed by Nāsir Taqvā’ī, 1972.

However, this view of ideology as something ubiquitous, influenced by the ideas of some Western thinkers, lacks conceptual and methodological nuances. A cinematic work cannot be identified as an ideological work solely based on a few scenes containing social and ideological values. If everything is considered ideological, then ideology must be seen as necessary, inevitable, and intrinsic to a work. This perspective grants ideology significant weight, implicitly elevating it and, in a sense, making it beyond critique. It shifts the focus of critique, directing attention toward the type of ideology and its functions, rather than its nature. Simply put, we must recognize that cinematic works have both value and normative aspects. Then, we can question whether it is reasonable to expect a type of cinema or film entirely devoid of these aspects. If cinema and cinematic works present a narrative of human and social life, can they truly be free of value and normative elements? Therefore, in this context, I use the concept of a value and normative system, rather than the broader definition of ideology found in the works of thinkers like Louis Althusser,10Louis Althusser, “Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses (Notes towards an Investigation),” trans. Ben Brewster, in Lenin and Philosophy and Other Essays (London: New Left Press, 1971), 127–86. Roland Barthes, John Fiske and others, whose ideas have influenced many discussions of ideology and cinema.11For example, see Ihsān Āqā-Bābā’ī and Siyāmak Rafīʿī, Fīlm va īdi’uluzhī dar Īrān: dahah-yi hashtād [Film and ideology in Iran from 2001 to 2011] (Tehran: Ligā, 2023); Sayyid Murtazā Fātimī, īdi’uluzhī bih rivāyat-i sīnimā: mutāli‛ah-yi nisbat-i īdi’uluzhī va zībā’ī’shināsī dar sīnimā-yi fāshīsm va lībirālīsm [Ideology as narrated by cinema: A study of the relationship between ideology and aesthetics in fascism and liberalism cinema] (Tehran: Naqd-i Farhang, 2024). Their perspectives have contributed to viewing ideology as something ubiquitous. It is inevitable for cinematic works to express and reflect different value systems. The filmmakers and directors should not be criticized for expressing their value system in their work, whether explicitly or implicitly.

- c) Gaining credit and legitimacy through cinematic events: this is another way by which ideologies can benefit from cinema. In this case, the focus is not directly on the content of the films, but on their contribution to the cinematic event in the country, which confers legitimacy on both domestic or international scales.

- d) Ideological use of cinema and cinematic works in the true and exclusive sense of the term: in this sense, cinema and cinematic works can be considered ideological only when there is clear and strong evidence for the existence of elements and content derived from an ideological system. Only such films can be labeled as ideological works.

It seems necessary to delve into different meanings of ideology and argue about its meaning and its different definitions. There are at least three traditions in defining ideology:

- A tradition that views ideology as negative, focusing on its harmful functions, such as deception, creating complacency, maintaining existing conditions, and legitimizing the dominant and powerful class, as seen in the Marxist definition of ideology.

- An intellectual tradition that regards ideology positively, recognizing its constructive functions, such as motivating people to act and promoting social and political change, as seen in the Weberian definition of ideology.

- A tradition that seeks to use the concept of ideology in a scientific manner, without judging or labeling it with positive or negative connotations.

I intend to adopt the third approach in this article and use a definition of ideology that is free from normative connotations and serves a descriptive function. However, there is another significant issue: the ubiquitous definition of ideology. As discussed earlier, some define ideology as something that is present everywhere. According to their definition, ideology is inevitably omnipresent in social life, manifesting in various forms. John Fiske refers to Raymond Williams to discuss three main functions of ideology, with the third function being an example of ubiquitous definition of this term:

There are a number of definitions of ideology. Different writers use the term differently, and it is not easy to be sure about its use in any one context. Raymond Williams (1977) finds three main uses:12Raymond Williams, Marxism and literature (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1977).

-

- A system of beliefs characteristic of a particular class or group.

- A system of illusory beliefs—false ideas or false consciousness—which can be contrasted with true or scientific knowledge.

- The general process of the production of meanings and ideas. These are not necessarily contradictory, and any one use of the word may quite properly involve elements from the others. But they do, nonetheless, identify different foci of meanings.13John Fiske, Introduction to communication studies, 2nd ed. (London: Routledge. 1990), 165.

Afterwards, Fisk explains each of these three definitions. Regarding the third definition, he states:

Ideology here is a term used to describe the social production of meanings. This is how Barthes uses it when he speaks of the connotators, that is the signifiers of connotation, as ‘the rhetoric of ideology’. Ideology, used in this way, is the source of the second-order meanings. Myths and connoted values are what they are because of the ideology of which they are the usable manifestations.14John Fiske, Introduction to communication studies, 2nd ed. (London: Routledge. 1990), 166.

Such a definition of ideology makes it a pervasive element in the social world. In effect, this definition, in reality, broadens its meaning, transforming ideology into an overly broad and thus unusable concept. This is why Terry Eagleton critiques certain definitions of ideology, explaining how Michel Foucault, by making power something ubiquitous and pervasive, was forced to abandon the concept of ideology and instead use the concept of “discourse”:

Such charity is a fault because it risks broadening the concept of ideology to the point where it becomes politically toothless; and this is the second problem with the ‘ideology as legitimation’ thesis, one which concerns the nature of power itself. On the view of Michel Foucault and his acolytes, power is not something confined to armies and parliaments: it is, rather, a pervasive, intangible network of force which weaves itself into our slightest gestures and most intimate utterances. On this theory, to limit the idea of power to its more obvious political manifestations would itself be an ideological move, obscuring the complex diffuseness of its operations. That we should think of power as imprinting our personal relations and routine activities is a dear political gain, as feminists, for instance, have not been slow to recognize; but it carries with it a problem for the meaning of ideology. For if there are no values and beliefs not bound up with power, then the term ideology threatens to expand to vanishing point. Any word which covers everything loses its cutting edge and dwindles to an empty sound. For a term to have meaning, it must be possible to specify what, in particular circumstances, would count as the other of it – which doesn’t necessarily mean specifying something which would be always and everywhere the other of it. If power, like the Almighty himself, is omnipresent, then the word ideology ceases to single out anything in particular and becomes wholly uninformative. […] Faithful to this logic, Foucault and his followers effectively abandon the concept of ideology altogether, replacing it with the more capacious ‘discourse’.15Terry Eagleton, Ideology: An introduction (London: Verso, 1991), 7-8.

Here, Eagleton warns against the danger of expanding the meaning of ideology, while also emphasizing the unique significance of the concept of ideology and its distinction from the concept of discourse. He argues that using discourse instead of ideology may involve relinquishing “too quickly a useful distinction. The force of the term ideology lies in its capacity to discriminate between those power struggles which are somehow central to a whole form of social life, and those which are not.”16Terry Eagleton, Ideology: An introduction (London: Verso, 1991), 8.

Therefore, while emphasizing the unique advantage of the concept of ideology and its distinction from the concept of discourse, Eagelton critique the ubiquitous definition of ideology and properly argues that “those radicals who hold that ‘everything is ideological’ or ‘everything is political’ seem not to realize that they are in danger of cutting the ground from beneath their own feet,”17Terry Eagleton, Ideology: An introduction (London: Verso, 1991), 8. because “to stretch these terms to the point where they become coextensive with everything is simply to empty them of force, which is equally congenial to the ruling order.”18Terry Eagleton, Ideology: An introduction (London: Verso, 1991), 8. Eagelton makes a valid observation that ideology should be regarded “as a discursive or semiotic phenomenon. And this at once emphasizes its materiality (since signs are material entities), and preserves the sense that it is essentially concerned with meanings. Talk of signs and discourses is inherently social and practical, whereas terms like ‘consciousness’ are residues of an idealist tradition of thought.”19Terry Eagleton, Ideology: An introduction (London: Verso, 1991), 194. Consequently, “this would need to be so for a discourse to be dubbed ideological,”20Terry Eagleton, Ideology: An introduction (London: Verso, 1991), 202. but each ideology is “primarily performative, rhetorical, pseudo-propositional discourse.”21Terry Eagleton, Ideology: An introduction (London: Verso, 1991), 221.

Based on this insight, I use in this article the term ‘ideology’ in its limited meaning as something identifiable and specific, distinguished from value and normative systems:

- Ideology is a belief system that is created in the modern era and covers three different aspects of human culture: cognitive aspect (by presenting a different outlook to human and its world), expressive aspect or emotions (by evoking motivations and emotions, having psychological effects on humans, and forming the expressive aspect of culture), and normative aspect or the field of ethics and praxis and presenting a type of life-style.22About these three aspects of human and the three fields of culture, see Charles Davis, Religion and the making of society: Essays in social theology (Cambridge, 1994), 49-51.

- Ideology is a belief system for organizing the social world. Ideologies, thus, have the potential to present a framework to organize the social world.

- Culturally, ideologies are omnivorous, drawing from diverse cultural elements, especially myths, and possessing the ability to generate new myths.

- Ideologies can be evaluated both for their internal coherence and their effectiveness. As Jean Baechler argues, “an ideology can be criticized only because of its inefficiency and its incoherence.”23Jean Baechler, Qu’est-ce que l’idéologie? (Paris: Gallimard, 1976), 61.

- Ideologies are connected to tastes and emotions, shaping identities while cultivating a sense of belonging and solidarity.24Jean Baechler, Qu’est-ce que l’idéologie? (Paris: Gallimard, 1976), 59.

Based on above definitions of ideology, they differ from one another in the forms of othering they employ. In this respect, some ideologies have the potential for extreme polarization, dividing the world into opposing extremes like virtue/vice, good/bad and self/other; while others engage in othering in a more nuanced, spectrum-based manner, acknowledging varying degrees of difference rather than absolute oppositions. Therefore, ideologies may be divided into two types of polarizing and non-polarizing. In this article, when I refer to ideologies, I specifically mean belief systems that emerged in the modern world, such as liberalism, fascism, Marxism, feminism, nationalism, and Islamism.

Nationalism in Iranian Cinema

Figure 4: A still from the film Intolerance, directed by David Wark ‘D. W.’ Griffith, 1916. Accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lv6u3d99SKk (01:29:53).

The first ideology to emerge in and influence Iranian cinema was nationalism. This was likely due to two factors, first, cinema was introduced to Iran through the royal court and nobility,25Masʿūd Mihrābī, Tārīkh-i sīnimā-i Īrān: Az āghāz tā sāl-i 1357 [History of Iranian cinema: From the beginning to the year 1979], 7th ed. (Tehran: Nazar, 1992), 15. and, second, cinema began operating publicly in Iran at a time when an outdated nationalist government was in power. However, one should not overlook the influence of nationalistic ideas of Iranian intellectuals during the Constitutional era on the dramatic arts of the period.26Muhsin Zamānī and Farhād Nādirzādah Kirmānī, “In‛ikās-i millī’garā’ī dar adabiyāt-i namāyishī-i rūzigār-i Pahlavī-i avval” [The reflection of nationalism in the dramatic literature of the first Pahlavi period], Hunar’hā-yi zībā – Hunar’hā-yi Namāyishī va Mūsīqī 42 (Fall and Winter 2010), 30. Hamid Naficy introduces the concept of “syncretic Westernization,” which simultaneously advocated promoting pre-Islamic and Zoroastrian cultural traits, modernizing the society, homogenizing the cultural, social, and political fields, and secularizing the society.27Hamid Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema, Volume 1: The Artisanal Era, 1897-1941 (Duke University Press, 2011), 141-142. I find the term ‘syncretic Westernization’ inaccurate because I distinguish between modernization and Westernization. I believe one of the reasons for the downfall of the Pahlavī dynasty and its development project was its failure to make this distinction. The archaism, forced secularization, and Westernization of culture and society during the Pahlavī period all went against Islamic traditions and culture. Additionally, modernization was incomplete and did not entail political development. A combination of these factors formed resistance and ignited protests against the Pahlavī government. Nevertheless, Naficy aptly explains the process of forming an archaic nationalistic ideology and constructing the social world based on it.28Hamid Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema, Volume 1: The Artisanal Era, 1897-1941 (Duke University Press, 2011), 142-147. As Sadr argues, nationalistic ideology in Iranian cinema can be traced back to the early years of the Pahlavī period:

Whenever the name Rizā Shāh was mentioned, it was accompanied by the adjective ‘patriot,’ reinforcing his chauvinistic vision of Iran. He justified his patriarchal sovereignty in the name of the nation. Throughout the Pahlavī period, statements like these were frequently spoken and written: “once again in the ancient history of Iran, an Iranian patriot rose up to protect the country from danger, and Rizā Shāh was such a man.” To justify this perspective, cinema served as a suitable medium, frequently defending the monarchy. In a country like Iran, where literacy rates were low at the beginning of Rizā Shāh’s reign, screening films functioned much like publishing books and newspapers, as they could reach even the illiterate. It was a unique tool used to reinforce the legitimacy of the new dynasty, the mighty Shah and his new regime. In November 1927, the film Cyrus the Great, the Conqueror of Babylon was screened at the Grand Cinema. Some newspapers enthusiastically linked it to the history of Iran, using it as an opportunity to celebrate the current situation: ‘…those who have read the history of Iran know the invaluable services Cyrus the Great, the founder of Achaemenid dynasty and reviver of Iran, rendered to the Iranian nation and the high status he holds in the world. Go to the Grand Cinema to see this Shah, and witness, in this film, the conquests of Cyrus the Great, the King of Babylon and the civilization of Chaldea, as well as the social life of that time.’ The film’s title and these statements functioned as advertisements for Rizā Shāh, drawing a parallel between him and Cyrus, the reviver of Persia/Iran […] However, the film screened at the Grand Cinema was actually a part of the famous film Intolerance, directed by David Wark ‘D. W.’ Griffith, in 1916. An episode of the film titled “The Ancient Babylon” depicted the battle between the peaceful prince Belshazzar of Babylon and the king of Persia (played by George Siegmann), in 539 BC, which led to Belshazzar’s defeat. In fact, the film was not about the Persian Empire, rather, it depicted the innocence being destroyed by the Persians. This plagiarism never subjected to any scrutiny.29Hamīd Rizā Sadr, Dar’āmadī bar tārīkh-i siyāsī-i sīnimā-i Īrān (1280–1380) [An introduction to the political history of Iranian cinema from 1901-2001], 1st ed. (Tehran: Nay, 2002), 26.

Figure 5: A still from the film Intolerance, directed by David Wark ‘D. W.’ Griffith, 1916. Accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lv6u3d99SKk (00:21:54).

Some argue that elements of nationalistic ideology are evident even in the first sound film of Iranian cinema, directed by Ardashīr Īrānī and produced by and starring ‛Abdul-Husayn Sipantā. For instance, the film’s intertitle states: ‘Years passed. Coup d’état of February 2, 1921. The rising sun of prosperity in Iran.’30Ghulām Haydarī, Zāviyah-yi dīd dar sīnimā-yi Īrān [Point of view in Iranian cinema] (Tehran: Daftar-i Pazhūhish-hā-yi Farhangī, 1990), 18. Some have also examined how early Iranian films promoted archaic Iranism: “The earliest films of Iranian cinema indirectly conveyed the ideas of the highest office of the country. These films focused heavily on issues such as security in the country (in Dukhtar-i Lur [Lor Girl]) or the ancient values of Iran (Nādir Shāh’s conquest of Lahore in the film Firdawsī).”31‛Alī Asghar Kishānī, Farāyand-i takāmul-i sīnimā-i Īrān va hukūmat-i Pahlavī [The process of interaction between Iranian cinema and Pahlavi government] 1st ed. (Tehran: Markaz-i Asnād-i Inqilāb-i Islāmī, 1386/2007), 60. The fact that Dukhtar-i Lur has another title, Īrān-i dīrūz va Īrān-i imrūz (The Iran of yesterday and the Iran of today) testifies to the film’s intention of portraying two different Irans: Iran before Rizā Shāh and Iran after his ascension. Hamid Naficy describes this film in terms of “cinematic nationalism based on feminism and anti-Arabism” and argues,32Hamid Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema, Volume 1: The Artisanal Era, 1897-1941 (Duke University Press, 2011), 274

The pair spends years in exile. Reza Shah comes to power in Iran, and a new Iranian flag is raised high, causing the exiles to consider returning. Here, the film shows a modernized Iran, one secure from banditry under the new Pahlavi regime. Under a picture of Reza Shah on the wall in Golnar’s parental home, to which she is now restored, she plays the piano happily. Personal love, love of country, and love of the Shah fuse and become triumphant. Jafar is now dressed in a Pahlavi-dictated suit and cap, while Golnar is without a veil, demonstrating the victory of Reza Shah’s sartorial reforms. As she plays the piano, he sings a patriotic song to the new ruler, whose picture, as a rising star, ends the film.33Hamid Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema, Volume 1: The Artisanal Era, 1897-1941 (Duke University Press, 2011), 234.

Figure 6: A still from the film Dukhtar-i Lur (Lor Girl), directed by Ardashīr Īrānī, 1921.

Some critics talk about political propaganda as well as censorship in Iranian cinema. It seems to be a common practice for all governments to use cinema to promote their goals and agendas, a trend that can be seen in both the Pahlavī and Islamic Republic eras.34‛Alī Asghar Kishānī, Farāyand-i takāmul-i sīnimā-i Īrān va hukūmat-i Pahlavī [The process of interaction between Iranian cinema and Pahlavi government] 1st ed. (Tehran: Markaz-i Asnād-i Inqilāb-i Islāmī, 1386/2007), 61. It is argued that during the early Pahlavī period, ‘documentary films made about various military and non-military ceremonies testify to the court’s strong inclination toward documenting events through cinema.’35‛Alī Asghar Kishānī, Farāyand-i taʿāmul-i sīnimā-i Īrān va hukūmat-i Pahlavī [The process of interaction between Iranian cinema and Pahlavi government] 1st ed. (Tehran: Markaz-i Asnād-i Inqilāb-i Islāmī, 1386/2007), 61. and that “Khān’bābā Muʿtazidī’s documentary films made between 1926-1941, were all sponsored by the court.”36‛Alī Asghar Kishānī, Farāyand-i taʿāmul-i sīnimā-i Īrān va hukūmat-i Pahlavī [The process of interaction between Iranian cinema and Pahlavi government] 1st ed. (Tehran: Markaz-i Asnād-i Inqilāb-i Islāmī, 1386/2007), 67. However, this is something even Iranian do today, and the Pahlavī court cannot be blamed for having done the same. Censorship in cinema is a common practice in totalitarian regimes, though it is highly destructive to the medium, and we cannot expect anything different from such governments.37‛Alī Asghar Kishānī, Farāyand-i taʿāmul-i sīnimā-i Īrān va hukūmat-i Pahlavī [The process of interaction between Iranian cinema and Pahlavi government] 1st ed. (Tehran: Markaz-i Asnād-i Inqilāb-i Islāmī, 1386/2007), 64. The topic of censorship in Iranian cinema has been raised many times but the present article suggests a more complex approach, i.e., a cinema which is in the service of a particular ideology. Nevertheless, what is quoted from ‛Abdul-Husayn Sipantā, the film director during Rizā Shāh’s period, is catastrophic: “In the government system, nothing mattered except money and connections. Hard work, craftsmanship, and art were not valued. They expected Persian films to be produced for the government and thoroughly praise the government. The film Laylī va Majnūn was criticized for not mentioning the Shāh’s name.38”Jamāl Umīd, Tārīkh-i Sīnimā-yi Īrān 1279 – 1357 [The history of Iranian Cinema, 1900 – 1979] (Tehran: Ruzanah, 1995), 76.

Nationalism was present in Iranian cinema during the second Pahlavī period, as well. Traces of nationalism can be found in films made in the mid-twentieth century which, from a political perspective, can be considered the period of both the real and symbolic battle between two types of nationalism: Constitutionalism, which is sometimes called Musaddiqī or Madanī (civil) nationalism, and patriarchal or Pahlavī nationalism. In fact, the real battle between these two forms of nationalism in the political field led to the victory of the Pahlavī regime with a coup d’Etat against Musaddiq’s government. But this victory, in the social-political environment of that period, was interpreted as the failure of the political legitimacy. Consequently, the dominant system sought to recreate this legitimacy in one way or another, and the medium of cinema was one of its tools. Sadr describes the reappearance of patriarchal nationalism in the cinema of the 1950s, “in the age of oppression of nationalistic sensibilities,” through what he calls “making quasi-historical films,”39Hamīd Rizā Sadr, Dar’āmadī bar tārīkh-i siyāsī-i sīnimā-i Īrān (1280–1380) [An introduction to the political history of Iranian cinema from 1901- 2001], 1st ed. (Tehran: Nay, 2002), 125-126. such as Āghā Muhammad Khān Qājār (1954) and ‛Arūs-i Dajlah (Bride of Tigris, 1954) by Nusrat-Allāh Muhtasham, Shāhīn-i Tūs (The Eagle of Tūs, 1954) by Karīm Fakūr, Amīr Arsalān Nāmdār (1955) and Qizil Arsalān (1957) by Shāpūr Yāsimī, Yūsuf va Zulaykhā (1956) by Siyāmak Yāsimī, Bījan va Manīzhah (1958) by Manūchihr Zamānī, Yaʿqūb Lays Saffārī (1957) by ‛Alī Kasmā’ī.

Figure 7: A still from the film Yaʿqūb Lays Saffārī, directed by ‛Alī Kasmā’ī, 1957.

What was lost in reality on the social level was meant to be compensated for on the cinema screen or through other representations. National grandeur, which had briefly appeared in the Iranian political landscape through a social movement, now seemed lost after the suppression of the oil nationalization movement. The social movement that had sparked hope and excitement among the people, for better or worse, ultimately led to a sense of failure and disillusionment. Therefore, it became necessary to reconstruct that nationalistic image for society. “In fact, the Coup shattered down everyone’s hopes for attaining political and social freedom. The government that came to power as a result of the Coup created an environment filled with fear and terror through its constant arrests, bans and executions. This situation had such a profound effect on the Iranian people that, even today, it occasionally reappears in literature.”40Asad Sayf, “Taʾsīr-i kūditā-yi Murdād bar adabiyāt-i Fārsī,” Deutsche Welle, August 19, 2021, accessed on September 6, 2024, https://www.dw.com/fa-ir…/a-58904633 In the years following the coup, state-owned media and its associated or controlled forces portrayed the grandeur and progress of Iran, which was revived under the patriarchy of the Shah. In contrast, independent cultural agents depicted failure, disillusionment, and darkness.41Anūsh Sālihī, “Bāztāb-i kūditā-yi Murdād 1332 dar adabiyāt-i dāstānī-i Īrān,” Tarikhirani, November 13, 2021, accessed on September 6, 2024, http://tarikhirani.ir/fa/news/8712/

With its unique and impactful characteristics, Iranian cinema was inevitably subject to control and censorship; therefore, it was unable to properly reflect independent thoughts and ideas through the medium of cinema. It is argued that Nāsir Taqvā’ī’s film, Ārāmish dar huzūr-i dīgarān (Tranquility in the presence of others, 1970), “the first feature film by Nāsir Taqvā’ī, after many years of being banned, was eventually screened only after 40 minutes were cut, reducing the film to an 80-minute version.”42Masʿūd Mihrābī, Tārīkh-i sīnimā-i Īrān: Az āghāz tā sāl-i 1357 [History of Iranian cinema: From the beginning to the year 1979], 7th ed. (Tehran: Nazar, 1992), 155. If a director intended to convey different and independent thoughts to the audience in their film, they had to employ a form of symbolism that would mostly be misunderstood by the people. However, these independent films needed to be decoded, as this was beyond the understanding of the average cinema-goers of the time. Asrār-i ganj-i darrah-yi jinnī (The ghost valley’s treasure mysteries, 1974), directed by Ibrāhīm Gulistān, was among the films that needed to be decoded.43Masʿūd Mihrābī, Tārīkh-i sīnimā-i Īrān: Az āghāz tā sāl-i 1357 [History of Iranian cinema: From the beginning to the year 1979], 7th ed. (Tehran: Nazar, 1992), 161-162.

Figure 8: A still from the film Ārāmish dar huzūr-i dīgarān (Tranquility in the presence of others), directed by Nāsir Taqvā’ī, 1970.

After the coup, the media, including cinema, were more tightly controlled, and creative and productive artists faced greater limitations than before. Poetry, fiction, and independent cinema increasingly had to employ multi-layered symbolism to reflect the thoughts and emotions of their creators, as well as the social realities of the time. For instance, the audience needed to understand that “night” and “winter” symbolized the injustice and oppression of the government. However, on the other hand, in cultural products that were government-controlled or approved by the government, the condition of society was represented completely differently, almost the opposite of reality. Sadr provides a clear description of these various types of representations in quasi-historical films and reveals how patriarchal nationalistic values and symbols were presented without complex symbolism, using a simple language that was easily understandable to everyone.44Hamīd Rizā Sadr, Dar’āmadī bar tārīkh-i siyāsī-i sīnimā-i Īrān (1280–1380) [An introduction to the political history of Iranian cinema from 1901-2001], 1st ed. (Tehran: Nay, 2002), 126. It is curious, that no film about Cyrus the Great was created in this period, while “the most important subject matter of the plays of this period was the ancient history of Iran.”45Muhsin Zamānī and Farhād Nādirzādah Kirmānī, “In‛ikās-i millī’garā’ī dar adabiyāt-i namāyishī-i rūzigār-i Pahlavī-i avval” [The reflection of nationalism in the dramatic literature of the first Pahlavi period], Hunar’hā-yi zībā – Hunar’hā-yi Namāyishī va Mūsīqī 42 (Fall and Winter 2010), 31. Seemingly, a film on this subject was set to be made and even advertised; however, it was never produced.46Hamīd Rizā Sadr, Dar’āmadī bar tārīkh-i siyāsī-i sīnimā-i Īrān (1280–1380) [An introduction to the political history of Iranian cinema from 1901-2001], 1st ed. (Tehran: Nay, 2002), 131.

Figure 9: A still from the film Asrār-i ganj-i darrah-yi jinnī (The Ghost Valley’s Treasure Mysteries), directed by Ibrāhīm Gulistān, 1974.

Marxism in Iranian Cinema

Marxism is another ideology that had a significant influence on the society of Iran. Despite the formation of various Marxist groups in Iran, multiple factions repeatedly warned against the dangers of such an ideology, to the extent that events like the 1953 coup were justified by the perceived threat. Additionally, hundreds of cultural agents in Iran were under the influence of Marxism. Therefore, it is not unreasonable to expect the emergence of Marxist ideas in Iranian cinema. However, it is necessary to clarify here the difference between two left-wing ideologies, socialism and Marxism. Socialism emerged before Marxism, and at least three phases of it occurred: pre-Marxist socialism, Marxist socialism, and post-Marxist socialism. Zāhidī Langarūdī discusses the relationship between the two ideologies, Marxism and socialism, in Iran:

The emergence of Marxism in the second half of the nineteenth century is a catatonic shift in socialist thought, as since then, nearly all aspects of socialism have been influenced by this idea in one way or another. Since Marxism is grounded in social and historical analysis, aiming to uncover the inevitable laws of history, it is often regarded as scientific socialism. In Iran, socialist ideas emerged shortly before the Constitutional Revolution. Afterward, with the formation of the Tūdah Party, these ideas gained significant popularity. For two decades (in the 1960s and 1970s), Marxism dominated the history of Iran. However, the Marxist-communist branch of socialism, focused on revolution, had always been more popular than other branches. […] In Iran, most Communists and Marxists emphasized the lower-class masses of society and were successful in engaging with them.47Ahmad Zāhidī Langrūdī, Sīnimā va susiyālīsm dar Īrān [Cinema and socialism in Iran] (Nabisht, 2017).

It is important to distinguish between the two left-wing ideologies; however, it is also crucial to ask whether any work that focuses on the lower classes can be considered Marxist or socialist. Can we label any work that draws attention to societal inequality as Marxist or socialist? This is exactly the mistake Zāhidī Langarūdī makes in his book, Sīnimā va susiyālīsm dar Īrān (Cinema and socialism in Iran). He considers many cinematic works as socialist simply because they focus on deprived and disadvantaged people. For example, he writes about Furūgh Farrukhzād’s documentary Khānah siyāh ast (The house is black), which depicts people affected by leprosy: “the film Khānah siyāh ast was not, on the whole, a directly political-socialist film; however, this tendency was evident in many parts of the film.”48Ahmad Zāhidī Langrūdī, Sīnimā va susiyālīsm dar Īrān [Cinema and socialism in Iran] (Nabisht, 2017). He believes that Dāryūsh Mihrjū’ī’s Gāv (Cow, 1969) is also a socialist work. Zāhidī Langarūdī goes as far as calling many films made by the Institute for the Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults [Kānūn Parvarish-i Fikrī] socialist, such as Hayūlā (Monster, 1972) by Farshīd Misqālī, Bad-badah (Bad is bad, 1968) by Muhammad Rizā Aslānī, Ānkih khiyāl bāft bā ānkih amal kard (The one who imagined and the one who worked, 1971) by Murtazā Mumayyiz, Rangīn’kamān (Rainbow, 1973) by Nafīsah Riyāhī, Sāz’dahanī (Harmonica, 1973) by Amīr Nādirī, Bahārak (1976) by Isfandiyār Munfaridzādah, and Dunyā-yi dīvānah-yi dīvānah-yi dīvānah (The mad, mad, mad, world, 1975) by Nūr al-Dīn Zarrīn’kilk.49Ahmad Zāhidī Langrūdī, Sīnimā va susiyālīsm dar Īrān [Cinema and socialism in Iran] (Nabisht, 2017).

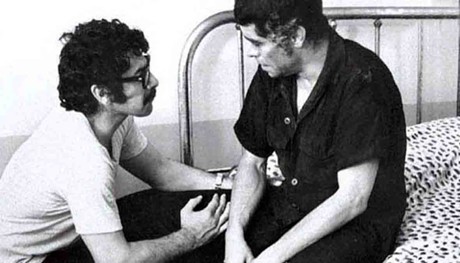

Zāhidī Langarūdī is trapped in viewing cinematic works excessively through the lens of socialism. Hence, it is not advisable to rely on his interpretation and analysis. He also discusses “guerilla cinema in Iran,” and argues that Amīr Nādirī’s Tangsīr (Tight spot, 1973) “praises armed resistance against the ruling power.”50Ahmad Zāhidī Langrūdī, Sīnimā va susiyālīsm dar Īrān [Cinema and socialism in Iran] (Nabisht, 2017). Since Marxism is often referred to as “the science of resistance,” exploring the concept of resistance may serve as a useful key for studying the presence of Marxism in Iranian cinema. Sadr believes that Iranian cinema in the 1970s promoted resistance and “armed struggle,” as seen in films such as Balūch (1972), by Masʿūd Kīmiyā’ī, and Sādiq Kurdah (1972), by Nāsir Taqvā’ī, being notable examples that express this subject matter. A crucial point he adds is the presence of religious elements in this type of film. Can we regard the emphasis on armed resistance in some of the films of the 1970s as the result of a convergence between the two dominant ideologies of the time, Marxism and Islamism? It seems that such an interpretation is not far from truth:

Tangsīr (Amīr Nāderi, 1973) based on the well-known story by Sādiq Chūbak, drew the audience into the turbulent south, turning personal revenge into a full-scale riot, nearly a kind of revolution. The subject of the hardworking men […] who see their efforts wasted by an interconnected chain of statesmen, effectively turns Tangsīr into a political manifesto. Film viewers felt a connection to “Zār-Mammad” (played by Bihrūz Vusūqī) when he cries in the bazar, “what kind of city is this, where everyone is a thief and a liar.” They regarded it as an allusion to the current situation in Iran. The presence of religion was more prominent in Tangsīr than in the previous films. In a scene, when Zār-Mammad’s requests to reclaim his money fail, he loses his composure and suddenly adopts a stern and determined expression, saying, “If it’s going to be with force, so be it!” He stands up and enters the frame from below, now, resembling an invincible man capable of breaking down any obstacle. The film focuses equally on his praying and on him retrieving his gun from the basement. The transformation of “Zār-Mammad” (symbolizing weakness) into “Shīr-Mammad” (symbolizing strength) in everyday conversations, culminating in loud shouts and widespread clashes with government officials, turns Tangsīr into a political film that suggests armed resistance is the only path to freedom.51Hamīd Rizā Sadr, Dar’āmadī bar tārīkh-i siyāsī-i sīnimā-i Īrān (1280–1380) [An introduction to the political history of Iranian cinema from 1901-2001], 1st ed. (Tehran: Nay, 2002), 215.

Figure 10: A still from the film Tangsīr, directed by Amīr Nāderi, 1973.

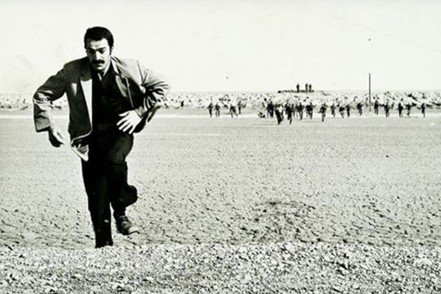

Sadr argues that Khāk (Soil, 1974), by Masʿūd Kīmiyā’ī, also “emphasizes that there is no path other than armed resistance against foreign invading forces.”52Hamīd Rizā Sadr, Dar’āmadī bar tārīkh-i siyāsī-i sīnimā-i Īrān (1280–1380) [An introduction to the political history of Iranian cinema from 1901-2001], 1st ed. (Tehran: Nay, 2002), 216. However, in Sadr’s view, “the most significant political film of the 1970s for proposing armed resistance as the only path for people” is Gavazn’hā (The deer, 1975), by Masʿūd Kīmiyā’ī.53Hamīd Rizā Sadr, Dar’āmadī bar tārīkh-i siyāsī-i sīnimā-i Īrān (1280–1380) [An introduction to the political history of Iranian cinema from 1901-2001], 1st ed. (Tehran: Nay, 2002), 216-218. He states that,

The main theme of Gavazn’hā is the close bond between two friends ⸺one an intellectual guerilla fighter and the other an ordinary man⸺ and the gradual elimination of their initial distance until they unite in the fight against the dominant system. They were portrayed as representatives of the political movements of the 1970s: the guerrilla fighter, symbolically named “Qudrat” (meaning Power), wearing a white shirt, thick moustache, and glasses—clichés of political fighters at the time, typically left-wing—and an ordinary man named “Sayyid,” referred to at one point in the film as “Sayyid Rasūl” (meaning the Prophet), symbolizing the religious beliefs of ordinary people.54Hamīd Rizā Sadr, Dar’āmadī bar tārīkh-i siyāsī-i sīnimā-i Īrān (1280–1380) [An introduction to the political history of Iranian cinema from 1901-2001], 1st ed. (Tehran: Nay, 2002), 216-218.

Can we interpret the union of these two characters in the armed fight against the dominant system in Gavazn’hā as a symbol of the convergence between Marxism and Islamism in the 1970s? Whatever the answer, it seems wiser to view the call for armed resistance in the films of the 1970s as a reflection of the social world shaped significantly by these two ideologies, rather than seeing the frequent repetition of this theme as a direct reflection of the ideologies themselves in Iranian cinema.

Figure 11: A still from the film Gavazn’hā (The deer), directed by Masʿūd Kīmiyā’ī, 1975.

Islamism in Iranian Cinema

The emergence of Islamic ideas and themes in Iranian cinema can be traced back to at least the 1970s. It seems that, in its early phases, the introduction of Islamism to Iranian cinema owes much to ‛Alī Sharīʿatī’s efforts. He brought theater into religious spaces with the goal of modernizing religion, but this was never accepted by traditional religious people. Sharīʿatī’s influence can be seen both directly, in the field of theater, and indirectly through his dramatic works. Perhaps one can regard two theater productions as precursors to the Islamist artistic movement: Abūzar, performed under the supervision of Sharīʿatī himself, first in Mashhad by Dāryūsh Arjmand and later at the Husayniyah Irshād in Tehran, directed by Īraj Saghīrī in 1972, and Sarbidārān, directed by Muhammad ‛Alī Najafī and performed at the Husayniyah Irshād.55“Bā Muhammad ‛Alī Najafī, khārij az gawd-i ‘Sarbidārān’,” ISNA, January 31, 2018, accessed on September 6, 2024, https://www.isna.ir/news/96111006111 As Najafī recollects,

After getting acquainted with Dr. Sharīʿatī, we decided to hold a theater and art class in the Husayniyah Irshād and I was appointed its manager (around the year 1966). In those years, I staged and directed a few plays. First, at the request of Dr. Sharīʿatī, Abūzar was staged, a play which was performed before by Dāryūsh Arjmand in Mashhad; afterwards, Hayʾat-i mutavassilīn bih shuhadā (A group devoted to martyrs) and then Sarbidārān were staged in the Husayniyah Irshād. It is said that one of the reasons the Husayniyah Irshād was closed was the staging of this latter play, which was only performed for one night. I remember that the play had a very fiery booklet that was written by Dr. Sharīʿatī himself, which was later published under the title Tashayyuʿ-i surkh (Red Shiism). In it, he wrote “Shia begins with ‛Alī’s ‘No’; which is a ‘No’ to the ruling government.” Dr. Sharīʿatī wrote much of Sarbidārān. Of course, Fakhr al-Dīn Anvār and I had written it earlier, but when Dr. Sharīʿatī saw the play’s structure, he said, “In this play, the form is stronger than the content.” He then worked on it for 48 hours, creating a version that was very modern in terms of performance. In fact, the actors entered among the spectators, and the stage was set up like a taʿziyah, with the audience seated on three sides of the scene. This play was staged for only one night and the ticket was 20 rials. Usually, tickets were not sold in religious places, but we sold tickets to maintain order and because of the limited space. Sarbidārān consisted of several acts; between them, there was a light which went off and on, through which music was played. It was for the first time that music was played in a religious space. These actions were a form of iconoclasm.56“Bā Muhammad ‛Alī Najafī, khārij az gawd-i ‘Sarbidārān’,” ISNA, January 31, 2018, accessed on September 6, 2024, https://www.isna.ir/news/96111006111

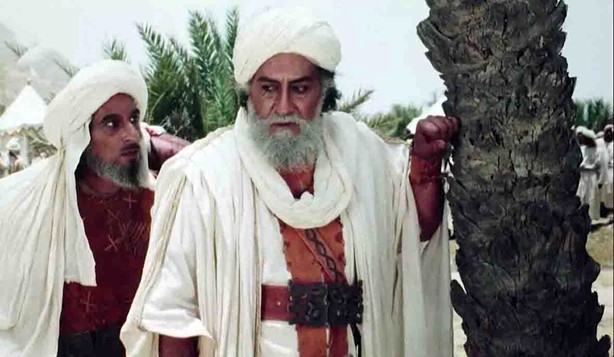

Figure 12: A still from the TV series Sarbidārān, directed by Muhammad ‛Alī Najafī, 1972.

Najafī has frequently discussed Sharīʿatī’s influential character.57Rizā Sāʾimī, “‛Alī Sharīʿatī va sīnimā / Qayar rā dūst dāsht: Guftārī mutafāvit bih bahānah-yi chihil u haftumīn sālgard-i darguzasht-i chihrah-yi farāmūsh’nashudanī,” Asriran, June 18, 2024, accessed on September 6, 2024, https://www.asriran.com/fa/news/975278/ As Sharīʿatī’s student, and with the same Islamist outlook shaped by his teacher’s influence, Najafī adapted Sarbidārān into a TV series after the Revolution. He says, “toward the end of Sarbidārān, I became someone who viewed art through an ideological lens.”58“Bā Muhammad ‛Alī Najafī, khārij az gawd-i ‘Sarbidārān’,” ISNA, January 31, 2018, accessed on September 6, 2024, https://www.isna.ir/news/96111006111 Dāvūd Mīrbāqirī and Hasan Fathī were the two other directors influenced by Sharīʿatī,59Rizā Sāʾimī, “‛Alī Sharīʿatī va sīnimā / Qayar rā dūst dāsht: Guftārī mutafāvit bih bahānah-yi chihil u haftumīn sālgard-i darguzasht-i chihrah-yi farāmūsh’nashudanī,” Asriran, June 18, 2024, accessed on September 6, 2024, https://www.asriran.com/fa/news/975278/ whose influence is evident in Mīrbāqirī’s TV series Imām ‛Alī (1996).60Mīlād Jalīlzādah, “‛Alī Sharīʿatī pusht-i dūrbīn,” Farhikhtegan, May 14, 2020, accessed on September 7, 2024, https://farhikhtegandaily.com/news/41026 Mīrbāqirī says in this regard:

The influence of Sharīʿatī on me stemmed from his new ideas about politics and society, blended with religion. I certainly never claimed that I intended to become like Sharīʿatī in my field, but I believed that the dramatic presentation of such concepts might be even more engaging than Dr. Sharīʿatī’s writings. Drama has an effective and durable impact.”61“Musāhabah-yi khāndanī bā Dāvūd Mīrbāqirī,” Afkar News, March 29, 2012, accessed on September 7, 2024, https://www.afkarnews.com/fa/tiny/news-93617

Figure 13: A still from the film Imām ‛Alī, directed by Dāvūd Mīrbāqirī, 1996.

The influence of religious figures and Islamists in cinema led to the eventual introduction of religion and Islamist ideology into the field. Muhsin Makhmalbāf, the famous director known for creating some of the best religious and Islamist works in Iranian cinema, has been greatly influenced by Sharīʿatī:

In contrast to the clerics who were completely opposed to art or unfamiliar with it, Sharīʿatī in his book, Chih bāyad kard va az kujā shurūʿ kunīm (What to do and where to begin), aimed to harness art and literature for the new movement he had initiated. (Influenced by him, we formed a theater group in Masjid-i Naw and occasionally staged plays in one of the mosques, doing so secretly. I wrote the plays and directed them. In those days, I usually went to work on weekdays and in the evenings, we rehearsed with our group in the library of the mosque).62Muhsin Makhmalbāf, Khātirāt [Memoir], 1st ed. (London: Nīkān, 2023), 129.

Nevertheless, it is necessary to distinguish between Islamic themes and Islamist ideas in cinema. The former is a religion, while the latter is a religious ideology that claims to have the potential to organize the society and to govern it in the modern era. Therefore, I distinguish between cinema that represents Islam and Islamic themes and cinema that introduces and promotes Islamism. It seems that some researchers have not given this distinction the attention it deserves.63For example, see Aʿzam Rāvadrād, Majīd Sulaymānī and Ruʾyā Hakīmī, “Tahlīl-i bāznamā’ī-i guftimān’hā-yi dīnī dar sīnimā-yi Īrān: Mutāliʿah-yi muridī-i fīlm-i Kitāb-i Qānūn” [The analysis of the representation of religious ideologies in Iranians cinema, a case study: The film Book of Law], Mutāliʿāt va tahqiqāt-i Ijtimā‛ī 1 (2012): 71-88; Muhaddisah Sādāt Mūsavī Sāmah & Farshād ‛Asgarī-kiyā, “Mutāliʿah-yi nahvah-yi bāznamā’ī-i aqalliyat’hā-yi dīnī dar sīnimā-yi Īrān baʿd az inqilāb-i Islāmī, bar asās-i ārā-yi Stewart Hall” [A study of the method of representation of religious minorities in Iranian cinema after the Islamic revolution based on Stewart Hall’s ideas], Rahpūyah-i hunar’hā-yi namāyishī 2, no. 4 (2022): 49-58. Cinema depicting Islam64I intentionally do not use the terms “Islamic cinema” and “religious cinema” because in the contemporary Iran, these terms bring different concepts to mind. Nacim Pak-Shiraz points out that “the very definition of what constituted ‘Islamic Cinema’ became fraught with disagreements across the spectrum of filmmakers, critics, religious authorities and those within the industry.” See Nacim Pak-Shiraz, “The Qur’anic Epic in Iranian Cinema,” Journal of Religion & Film 20, no. 1, (2016): 6; About the usage of the term “religious cinema” see, and Islamic themes can be seen as a modern continuation of religious performances from taʿziyah. Some scholars have used the term “religious films”65Anne Demy-Geroe, Iranian national cinema: The interaction of policy, genre, funding, and reception (London and New York: Routledge, 2020), 33. for this type of films, and have also discussed “spiritual films”66Anne Demy-Geroe, Iranian national cinema: The interaction of policy, genre, funding, and reception (London and New York: Routledge, 2020), 34. when referring to them. Films and TV series such as Rūz-i vāqiʿah (The fateful day, 1994) by Shahrām Asadī, Imām ‛Alī (1996), and Mukhtār’nāmah (2009), both by Dāvūd Mīrbāqirī, Tanhātarīn sardār (The loneliest leader, 1996), about the second Shia Imam, and Vilāyat-i Ishq (The reign of love, 2000) about the eighth Shia Imam, both directed by Mahdī Fakhīmzādah, Mulk-i Sulaymān (The Kingdom of Solomon, 2010), by Shahryār Bahrānī, Muhammad Rasūl-Allāh (2014), by Majīd Majīdī, all explore religious subjects but differ from Islamist works. One cannot draw a clear line between works with Islamic themes and Islamist works, as some of the religious works also display some aspects of Islamism. However, cinema that seeks to introduce and promote Islamism aims to present a different version of Islam for the political governance of society and for addressing various issues in our time.

Figure 14: A still from the film Huviyat (Identity), directed by Ibrāhīm Hātamīkiyā, 1985.

Islamist ideology is fully present in some films of post-revolutionary Iranian cinema, with directors such as Ibrāhīm Hātamīkiyā, who has reflected this ideology in most of his works. For instance, some critics have discussed the opposition between the two types of Islamism in Hātamīkiyā’s Huviyat (Identity, 1985): “Islamism based on Islamic law” and “Islamism based on general good.”67‛Abdallāh Bīchirānlū, Muhammad Hasan Hāshim-Khānlū, “Bāznamā’ī-i sīnimā’ī-i bāft-i siyāsī-i Īrān: Tahlīl-i guftimān-i intiqādī-i mawridī-i fīlm-i Huviyat” [Cinematic representation of Iranian political context: A critical discourse analysis of the film Identity], Majallah-yi Jahānī-i Rasānah 13, no. 1 (2018): 184. Hātamīkiyā and directors like him were students and followers of Sayyid Murtazā (Kāmrān) Āvīnī, known for the documentary series Rivāyat-i fath (Chronicles of victory), which began in 1985 and fully embodies Āvīnī’s religious perspective. In addition to Najafī, Makhmalbāf, Āvīnī68To read about Āvīnī’s ideas and thoughts as well as his opinions about cinema, see: Karīm Nīkūnazar, “Shūrishī-i shahīd,” Mihr’nāmah 51 (2016): 220-225. and Hātamīkiyā, there are many other directors who have made Islamist works, such as Faraj-Allāh Salahshūr, Rasūl Mullāqulīpūr, Ziyā al-Dīn Durrī, Bihrūz Afkhamī, Nargis Ābyār, Parvīz Shaykh-Tādī, Amīr ‛Abbās Rabīʿī, Muhammad Mahdī ‛Asgarpūr, Javād Shamaqdarī, Masʿūd Dihnamakī and Jamāl Shūrjah. Some of them belong to a kind of cinema called “sīnimā-yi maktabī” (ideological cinema). At any rate, we can see reflections of Islamism in various works they have made. This period in Iranian cinema is marked by a division of filmmakers into two groups: insiders and outsiders; and many red lines were established for working in cinema.69Anne Demy-Geroe, Iranian national cinema: The interaction of policy, genre, funding, and reception (London and New York: Routledge, 2020), 20. In addition, the eight-year war between Iran and Iraq provided themes and potentials for the Islamic Republic to strengthen Islamist cinema and create a genre of cinema known as “Sacred defense cinema” (Sīnimā-yi Difā‛-i muqaddas).70Anne Demy-Geroe, Iranian national cinema: The interaction of policy, genre, funding, and reception (London and New York: Routledge, 2020), 24.

It is worth noting that Islamism is often depicted positively in many films and TV series after the Revolution; however, it occasionally appears with a negative portrayal as well. In the decades following the Revolution, numerous films and TV series have been created in response to political movements opposing the Islamic Republic. These films affirm Islamism in contrast to the regime’s opponents. Films such as Boycott (Makhmalbāf, 1985), Taʿqīb-i sāyah’hā (Chasing the shadows, 1990), by ‛Alī Shāh-Hātamī, Bih rang-i arghavān (In amethyst color, 2005), by Ibrahīm Hātamīkiyā, Mājarā-yi nīmrūz (Midday Adventures, 2017), by Muhammad Husayn Mahdaviyān, are just a few examples of the many films and TV series produced in recent decades in response to various opposition groups. All the aforementioned directors, who have made films with religious or Islamist themes, have received varying degrees of support from the Islamic Republic, at least for a certain period. The Fārābī Foundation, the Sūrah Cinematic Development Organization, the Awj Cinematic Organization, the Rivāyat-i Fath Foundation, the Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting (IRIB) and many other organizations have taken on the task of supporting these types of films and directors.

Figure 15: A still from the film Boycott (Bāykut), directed by Muhsin Makhmalbāf, 1985.

Feminism in Iranian Cinema

Another ideology that has been prominently emphasized in Iranian cinema and has sparked extensive discussion is feminism.71I am thankful of Dr. Muhammad ‛Alī Alastī, my dear colleague in Islamic Azad University, Central Tehran branch, in conversation with whom I realized the necessity to discuss this ideology. Indeed, this article would be incomplete without discussing the issues related to feminism in Iranian cinema. It is important to highlight the role of women writers and directors in reflecting this ideology through their cinematic works. Hamid Naficy argues that, from the time of Rizā Shāh, women became “cinematic objects.”72Hamid Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema, Volume 1: The Artisanal Era, 1897-1941 (Duke University Press, 2011), 151. Then, he identifies feminist themes in Dukhtar-i Lur and describes it as “cinematic nationalism based on feminism and anti-Arabism.”73Hamid Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema, Volume 1: The Artisanal Era, 1897-1941 (Duke University Press, 2011), 274. However, it’s important to distinguish between feminist films and those that simply portray women, women’s issues, and problems in general. In other words, not all films that feature women or address women’s issues can be considered feminist works. It seems that some critics have made this mistake by tracing feminism back to pre-revolutionary Iranian cinema or by considering the mere presence of themes related to women in any cinematic work as examples of feminism.74Rafīʿ al-Dīn Ismāʿīlī, “Jarayān’shināsī-i fimīnīsm dar sīnimā-yi Īrān” [Understanding feminist movements in Iranian cinema], Khiradvarzī 6 (2021): 17.

Feminist works refer to those that seek to transform social relations and the social world based on woman-centered ideas; therefore, facts such as the kashf-i hijab [the banning of Islamic veil] which was an imposed and mandatory act, or what Naficy refers to as the result of Rizā Shāh’s “sartorial reforms” should not be associated with feminism. The representation of women and women’s issues in cinema goes beyond the mere presence of feminist themes. Some critics have focused on the portrayal of women in Iranian cinema and have examined various aspects of it.75For example, see: Aʿzam Rāvadrād and Masʿūd Zandī, “Taghyīrāt-i naqsh-i zan dar sīnimā-yi Īrān” [The changes in the role of woman in Iranian cinema], Majallah-yi jahānī-i rasānah 1, no. 2, (2006): 23-50; Muhammad Rizā’ī and Sumayyah Afshār, “Bāznamā’ī jinsiyatī-i siriyāl’hā-yi tilivīziyun” [Gender-based representation in TV series], Pazhūhish-i zanān 1 (2010): 133-156; Ārash Hasanpūr and Bihjat Yazdkhāstī, “Prublimātīk-i zan-būdigī: Namāyish-i jinsiyat va barsākht-i klīshah’hā-yi akhlāqī-i zanānah dar sīnimā-yi Īrān” [Problematic of womanhood: Presentation of gender and construction of female moral clichés in Iranian cinema], Mutāliʿāt-i farhang – irtibātāt 16, no. 32 (2015): 33-68; Laylā Shāhrukh and Shahnāz Hāshimī, “Santiz’pazhūhī-i bāznamā’ī-i zanān dar sīnimā-yi Īrān” [A synthetic study of the representation of women in Iranian cinema], Jāmiʿah, farhang, risānah 6, no. 22 (1396/2017): 69-97; Maryam Rizā’ī, “Nigāhī bih bāznamā’ī-i chihrah-yi zan-i Īrānī dar sīnimā va tilivīziyun: Zan, sūzhigī va tasvir” [A look at the representation of the Iranian woman in cinema and television: Woman, agency and image], Radio Zamanah, February 8, 2018, accessed on September 7, 2024, https://www.radiozamaneh.com/380814

Shīvā Pazhūhish’far and Husayn Ghiyāsī, “Mafāhīm-i fimīnīstī dar dah fīlm-i purfurūsh-i sāl-i 87 sīnimā-yi Īrān va taʾsīr-i ān bar mukhātabān” [A study of the feminist concepts in ten best-selling films of Iranian cinema in 2008 and their influence on the audience], Farhang-i irtibātāt 2, no. 5, (2012), 159- 178; Sipīdah Amīrī and Fathallāh Zāriʿ Khalīlī, “Arzyābī-i nimūd-i naqsh-i ijtimā‛ī-i zan dar sīnimā-yi Īrān (Sāl’hā-yi 1390- 1396” [Evaluation of the manifestation of the social role of woman in Iranian cinema (years 2011 – 2017)], Zan dar farhang u hunar 11, no. 3 (2019): 309-324.

Another important point in this regard is the distinction between different types of feminism: feminism as a positive outlook on women and feminine life—one that respects women’s human dignity and is commonly understood by the general public in Iran;76Manīzhah Rabīʿī Rūdsarī, “Sar’anjām-i fimīnīsm dar Īrān” [The story of feminism in Iran], Zamānah 48 (2006), 3-11. feminism as a kind of life-style;77Bell Hooks, Feminism is for everybody: Passionate politics (Cambridge: South End Press, 2000). feminism as a research program and a theoretical vision (the study of the social world and human relations from a women’s perspective with a focus on feminine themes);78Ritzer, George and Stepnisky, Jeffrey, Sociological theory, 10th ed. (Los Angeles: Sage Publication. 2018), 545. feminism as a legal movement (which advocates for structural reforms and the recognition of women’s rights in society and supported by a range of social activists, often including both men and women in Muslim communities);79For an article criticizing this type of feminism, see: Zuhrah ‛Azīz-ābādī and Ārash Haydarī, “Fimīnīsm-i huqūq’garā va masʾalah-yi zan dar Īrān-i mu‛āsir” [Rights-based feminism and the issue of woman in contemporary Iran], Barrasī-i masā’il-i Ijtimāʿī-i Īrān 12, no. 2 (2021): 257-285. feminism as a social movement that calls for changes at various levels of social life;80Sarah Gamble, ed., The Routledge companion to feminism and postfeminism (London and New York: Routledge, 2006). and finally, feminism as an ideology and belief system aimed at reorganizing the social world, negating the superiority of men and the inferiority of women. When viewed as an ideology, feminism can be defined as follows:

Feminist ideology has traditionally been defined by two basic beliefs: that women are disadvantaged because of their gender; and that this disadvantage can and should be overthrown. In this way, feminists have highlighted what they see as a political relationship between the sexes, the supremacy of men and the subjection of women in most, if not all, societies.81Andrew Heywood, Political ideologies: An introduction, 7th ed. (Red Globe Press, 2021), 186.

Therefore, it is important to clarify which definition of feminism we are referring to when discussing feminism in Iranian cinema. In fact, these distinctions are often overlooked in most discussions about feminism in Iranian cinema. If we view feminism as an ideology, we can argue that feminist works in Iranian cinema have primarily emerged over the last three decades, largely as a result of the efforts of women writers and directors. It should be noted that, prior to the Revolution, some Iranian women filmmakers such as Shahlā Riyāhī (Marjān, 1333/1954), Furūgh Farrukhzād (Khānah siyāh ast, 1961) and Kubrā Saʿīdī (Maryam va Mānī, 1978) directed several films.82Rafīʿ al-Dīn Ismāʿīlī, “Jarayān’shināsī-i fimīnīsm dar sīnimā-yi Īrān” [Understanding feminist movements in Iranian cinema], Khiradvarzī 6 (2021): 14. However, after the 1979 revolution, women’s presence in Iranian cinema became more diverse and multifaceted. Some scholars claim that, prior to the Revolution, cinema was “predominantly viewed as a male-dominated medium in the Iranian artistic landscape.83”Nādiyā Maʿqūlī and ‛Alī Akbar Farhangī, “Fimīnīsm dar fīlm’hā-yi Rakhshān Banī-iʿtimād” [Feminism in Rakhshān Bani-eʿtemād’s films], Mutāliʿāt-i ijtimāʿi ravān’shinākhtī-i zanān 7, no. 2 (2009): 59-76. Following the revolution, “the first film directed by a woman was Rābitah (Relationship), made in 1985 by Pūrān Dirakhshandah.”84Rafīʿ al-Dīn Ismāʿīlī, “Jarayān’shināsī-i fimīnīsm dar sīnimā-yi Īrān” [Understanding feminist movements in Iranian cinema], Khiradvarzī 6 (2021): 15. Most notable women directors of this period were Rakhshān Banī-iʿtimād, Pūrān Dirakhshandah, Tahmīnah Mīlānī, Manīzhah Hikmat, Marziyah Burūmand, Tīnā Pākravān, Nīkī Karīmī, Āydā Panāhandah, Munā Zandī and Grānāz Mūsavī. On the other hand, some feminist films in Iranian cinema have been made by men. Barf rū-yi kāj’hā (The snow on the pines, 2011), by Paymān Muʿādī, is an example of a feminist film written and directed by a man:

Besides female directors, some of the male directors and producers of Iranian cinema have played a crucial role in shaping the representation of women, transforming their portrayal from passive and insignificant characters to powerful and significant heroines. Through their films, they have created a platform for amplifying women’s voices. By means of cinematic productions, they have defended women’s positions and critically examined the imbalanced relationship between men and women. Amid changing conditions for women, they challenged the status quo by questioning women’s identity, depicting the economic, physical, and psychological pressures they face, and exploring women’s freedom through cinematic techniques while raising profound relevant questions. Through critical representation, these filmmakers have portrayed a world of women filled with issues, experiences, emotions, thoughts, problems, concerns, and ideas about their environment, thus creating a new image of the Iranian woman. The portrayal of women in Iranian cinema has experienced many ups and downs in recent decades. With few exceptions, the history of Iranian cinema over the past three decades can be seen as a transition from the portrayal of women as silent, seductive, voiceless, and desexualized to a representation of women as critical, active, individual, and independent.85Ārash Hasanpūr, “Man īn hamah nīstam: Bāznamā’ī-i jahān-i zanānah dar fīlm-i ‘Barf rū-yi kāj’hā’” [I’m not all this: The representation of feminine world in The snow on the pines], Vista, accessed on September 7, 2024, https://vista.ir/w/a/21/7l4sk

Figure 16: A still from the film Khānah siyāh ast (The House Is Black), directed by Furūgh Farrukhzād, 1961.

This type of film presents anti-patriarchal arguments, suggesting feminist themes. The portrayal of the husband’s infidelity and the wife’s response highlights a new type of relationship between man and woman, with the woman emerging as a transformative, egalitarian, and active agent. The film Zanān bidūn-i mardān (Women without men, 2009), directed by Shīrīn Nishāt and adapted from a novel by Shahrnūsh Pārsī-pūr, is considered another example of feminist filmmaking in Iranian cinema.86Ihsān Āqā-Bābā’ī and Siyāmak Rafīʿī, Fīlm va īdi’uluzhī dar Īrān: dahah-yi hashtād [Film and ideology in Iran from 2001 to 2011] (Tehran: Ligā, 2023), 124. But it is Tahmīnah Mīlānī who is more often considered a feminist filmmaker. She makes women and their issues the center of attention in many of her films. Three or more of her films are considered feminist works in that they identify the present social structure as patriarchal and oppose it:

Du zan (Two women, 1998) is the first part of Mīlānī’s feminist trilogy, which, as she herself asserts, aims to make women aware of their social conditions and lost rights. The second part of this feminine trilogy is Nīmah-yi pinhān (Hidden half, 2000), which combines a romantic subject with social and political themes. The third and last film is Vākunish-i panjum (Fifth reaction, 2001), which is a feminine reaction against the laws of the patriarchal society. Mīlānī believes that Du zan explains women’s status within the structure of traditional society, which denies any independent identity for women, and that Nīmah-yi pinhān expresses women’s thoughts, hopes and social-political activities, which ultimately result in their oppression by the patriarchal society; and in Vākunish-i panjum, women react and express their resistance to the patriarchal society.87Muhammad Shakībādil, “Trīluzhī-i fimīnīstī-i Tahmīnah Mīlānī az Shuʿār tā vāqiʿiyat” [Tahmīnah Mīlānī’s feminist trilogy, from slogan to reality], Hūrā 3 (2003). https://shorturl.at/daWH1

Figure 17: A still from the film Du zan (Two women), directed by Tahmīnah Mīlānī, 1998.

Some scholars believe that “Milani is very vocal in proclaiming her feminist stance and has paid the price for this.”88Anne Demy-Geroe, Iranian national cinema: The interaction of policy, genre, funding, and reception (London and New York: Routledge, 2020), 52. Mīlānī affirms that she has a feminist outlook and accepts this interpretation of her three films. She states that her ambition is to change the social structure in order to achieve a balance in decision-making between men and women: “I live in a patriarchal society, but, my father, brother and husband do not make decisions for me. Instead, other men do. People like me strive to achieve justice. If feminism means balance, then yes, I am a feminist.”89Ru’yā Karīmī Majd, “Tahmīnah Mīlānī: Balah, man fimīnīst hastam” [Yes, I am a feminist], Radio Farda, June 5, 2017, accessed on September 7, 2024, https://www.radiofarda.com/a/b7-berlin-film-festival-2017/28529699.html In these words, the worldmaking aspect of feminist ideology is clearly evident.

Rakhshān Banī-iʿtimād is another filmmaker whose films, such as Nargis (1991), Rūsarī ābī (The Blue Veiled, 1994), Bānū-yi urdībihisht (May Lady, 1998) and Zīr-i pūst-i shahr (Under the skin of the city, 2000) are considered feminist, although she herself “has expressed disagreement with her films being labeled as feminist,”90Anne Demy-Geroe, Iranian national cinema: The interaction of policy, genre, funding, and reception (London and New York: Routledge, 2020), 53. and has stated that she does not want to be called a feminist.91Anne Demy-Geroe, Iranian national cinema: The interaction of policy, genre, funding, and reception (London and New York: Routledge, 2020), 53. This assertion, in itself, shows that there is no consensus on the meaning and definition of feminism, and that everyone interprets it from a different perspective. Various critics in Iran have discussed different feminist films. For example, in Āqā-Bābā’ī and Rafīʿī’s analysis, many of the films from first decade of the twentieth century in Iran can be labeled as “matriarchal.92”Ihsān Āqā-Bābā’ī and Siyāmak Rafīʿī, Fīlm va īdi’uluzhī dar Īrān: dahah-yi hashtād [Film and ideology in Iran from 2001 to 2011] (Tehran: Ligā, 2023), 124-130.

Figure 18: A still from the film Rūsarī ābī (The Blue Veiled), directed by Rakhshān Banī-iʿtimād, 1994.

Conclusion