Ideology and Social Classes in Twenty-First Century Iranian Cinema

Figure 1: A still from the film Crazy Rook (Rukh-i dīvānah), directed by Abulhasan Dāvūdī, 2015.

Abstract

In Iranian cinema, the portrayal of social class is influenced by ideology, as economic interests and cultural values are hidden behind class distinctions. Consequently, the way social classes are portrayed depends on the distribution of wealth in Iranian society and the characteristics of popular culture. The present study employs Antonio Gramsci’s theory of ideology and narrative analysis to demonstrate how ideology influences the representation of social class in twenty-first-century Iranian cinema. The analysis of selected films will demonstrate the existence of at least three distinct ideological orientations in Iranian cinema. Firstly, an anti-bourgeois ideology that opposes the lifestyle of the upper classes. Secondly, a sympathetic ideology that commiserates with the lower classes. Finally, an ideology of interaction-confrontation that pits two classes against each other and supports the values of one class over another. All of these clearly demonstrate that the relationship between ideology and class is both significant and influential in Iranian cinema.

Introduction

The financial crisis in Iran reached its most severe point in the early twenty-first century. The lack of growth in the industry and agriculture sectors, inflation, unemployment, international sanctions, oil rents, and administrative corruption had a deleterious effect on the lives of the general public. This phenomenon served to accentuate the distinction between social classes. In contrast to their predecessors, the younger generation of wealthy Iranians did not hesitate to display their affluence. The possession of foreign automobiles, branded apparel, iPhones, costly watches, and gold jewelry is indicative of a demonstration of social class.1‛Abbās Kāzimī, Amr-i ruzmarrah dar jāmi‛ah-yi pasā-inqilābī (Tehran: Farhang-i Jāvīd, 2016), 209. As studies have shown, even those in the lower socioeconomic classes have not been satisfied with the government subsidies. This is evidenced by the fact that they are not content with the cash subsidies, livelihood packages, and justice shares to which they are entitled. The imposition of economic sanctions and the reliance on a rent-based economy have eroded the purchasing power of the middle class, resulting in a larger disparity between the rich and the poor. This situation is at odds with the values espoused by the Islamic Revolution. In the aftermath of the revolution, the concept of class was regarded as a taboo subject. Islamic fundamentalists sought to construct a society predicated on piety, and the classification of individuals based on wealth was deemed to be a hallmark of the modernity they vehemently opposed. This aversion was further exacerbated by Islamist Marxists in the initial decade following the revolution.

Figure 2: Mahnāz Afshār in a still from the film Honey Venom (Zahr-i ‛asal), directed by Ibrāhīm Shaybānī, 2002.

In the cinema of the 1980s, the upper class represented the aristocracy associated with the Pahlavi government and was consequently condemned. Conversely, the lower class was depicted as espousing Islamic values and revolutionary ideals. In the 1990s, the upper class came to be regarded as a symbol of modernity, while the lower class was increasingly associated with social problems such as addiction, theft, and a range of other forms of deviance. Additionally, the emergence of a new middle class was depicted in cinematic narratives, and their espoused values, including individualism and moral rectitude, were subjected to criticism.2Ahmad Tālibīnizhād, Dar huzūr-i sīnimā: Tārīkh-i tahlīlī-i sīnimā-yi pas az inqilāb (Tehran: Fārābī Cinema Foundation Publications, 1998), 127; Hamid Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema, Volume 4: The Globalizing Era, 1984–2010 (Durham: Duke University Press, 2012). 52; Sareh Amiri & Ehsan Aqababaee, “Tahlīl-i rivāyat-i barsākht-i tabaqah-yi furūdast dar sinimā-yi pas az inqilāb-i islāmī.” Mutāla‛āt-i farhangī va irtibātāt 15, no. 55 (2019): 107-129; Ehsan Aqababaee & Mohammad Razaghi, “Islamic fundamentalism and gender: The portrayal of women in Iranian movies.” Critical research on religion 10, no. 3 (2022): 249-266; Ehsan Aqababaee & Katja Rieck, “The Representation of Social Classes in Iranian Cinema During the Reformist Era, 2001–2005.” Contemporary Review of the Middle East 10, no. 2 (2023): 106-125. From 2000 onwards, a considerable number of movies were produced in the Iranian film industry that explicitly address issues of class. This article, grounded in the theory of Antonio Gramsci, will examine the ideologies disseminated in modern Iranian cinema and elucidate their social and cultural origins.

Figure 3: A still from the film Superstar, directed by Tahmīnah Mīlānī, 2009.

Antonio Gramsci’s theory of ideology, which is pivotal to his concept of cultural hegemony, posits that dominant groups maintain power not solely through coercion but also by shaping societal norms, values, and beliefs in a manner that renders their dominance as natural and legitimate. Gramsci contends that the ruling class employs institutions such as education, media, and religion to disseminate its worldview, thereby ensuring the consent of subordinate classes.3Antonio Gramsci, “Selections from the prison notebooks.” In The Applied Theatre Reader, ed. Nicola Abraham & Tim Prentki (Routledge, 2020), 141-142. Gramsci’s concept of ideological control, or hegemony, is sustained through a combination of coercion and consent, with the latter being more pervasive and effective in maintaining long-term power. Gramsci emphasises the role of intellectuals in this process, as they help articulate and disseminate the dominant ideology. His insights highlight the importance of counter-hegemonic struggles, where marginalised groups challenge and reshape the prevailing ideology to achieve social change. An ideology that has achieved widespread acceptance by society can be regarded as a strategic endeavor on the part of a given social group to advance its interests through hegemonic means. According to Gramsci’s theory, cinema is a medium through which the ideological interests of social classes are expressed, and filmmakers and production agents play the role of organic intellectuals.

This article uses narrative analysis, which is defined as the examination of narrative genres and the systematic study of narrative and plot structure to look at film on two levels: story and discourse.4Luc Herman & Bart Vervaeck. Handbook of Narrative Analysis (University of Nebraska Press, 2019), 19. At the story level, the article examines the representation of place, actions, and characters, and at the discourse level, the film’s orientation towards these two will be described.5Seymour Chatman. Story and Discourse: Narrative Structure in Fiction and Film (Cornell University Press, 1980), 26. Discourse serves as the driving force that directs the narrative, operating under the influence of ideology.6Mike Cormack, Ideology (MI: University of Michigan Press, 1992), 30-33.

Figure 4: A still from the film Mr. Seven Colors (Āqā-yi Haft Rang), directed by Shahrām Shāh Husaynī, 2009.

Characterization is a term used to describe the process by which a researcher constructs a character’s personality by assembling various attributes present throughout the film. According to Rimmon-Kenan, characterization can be classified into three distinct forms: direct, indirect, and allegorical.7Shlomith Rimmon-Kenan, Narrative Fiction: Contemporary Poetics (Routledge, 2003), 61. Direct characterization involves the explicit narration of an individual character’s personality traits by the narrator. In contrast, indirect characterization is derived from the actions, social status, identity, and psyche of the characters, thereby revealing their personality. This article employs indirect characterization through the lens of purpose and action. Action, as defined by Berger, is the actions of the characters.8Arthur Asa Berger, Narratives in Popular Culture, Media, and Everyday Life (Sage Publications, 1996), 52. Place pertains to the determination of location, that is, the specific setting or environment within which the events of the narrative text unfold.

This study focuses on a sample size of forty-six Iranian films, all produced between 2000 and 2023. The selection of these films was purposeful, with a specific criterion guiding the inclusion process. Specifically, the films included in this analysis explicitly address issues of class representation. This selection ensures that the study captures a comprehensive range of perspectives on class dynamics within the context of Iranian cinema during the specified period. By concentrating on films that directly engage with this issue, the study aims to provide a detailed examination of the evolving narratives and portrayals of class within Iranian society over the past two decades.

Anti-bourgeois ideology

From the year 2000 onwards, despite the Iranian fundamentalists’ perception of globalization as an imperialist project, the expansion of the internet and satellite broadcasting had a profound impact on Iranian society, rendering it more susceptible to the forces of globalization. Over time, a number of chain restaurants were established in Tehran, with similar establishments subsequently opening in other cities. Chain stores such as Icepack were well-received in Iranian cities. The government’s increased oil revenue facilitated the introduction of commercial goods such as LED TVs. These developments gave rise to the emergence of a consumer society in Iran. Consequently, the display of wealth increased in urban areas, contributing to the growing opposition to class differences among the population. Moreover, in Iranian popular culture, there was a growing conviction that those of considerable wealth have amassed their fortunes illicitly, and that consuming prohibited substances will result in illness and misfortune for the affluent. The consequence of this process was an increase in the number of movies that espoused anti-bourgeois ideology.

Anti-bourgeois ideology is an attack on the values and interests of the upper classes, including the bourgeoisie, the nobility, and the nouveau riche. The ideology initially presents an opulent portrayal of the status of the upper classes, but then proceeds to delve beneath the surface of their lives, exposing the clandestine corruption that lies at their core. The ideology portrays the class as morally corrupt, exhibiting behaviors such as marital infidelity, promiscuity, rape, alcoholism, and authoritarianism. The family relationships of people belonging to this class are often accompanied by tension, insult, and humiliation. Economic corruption, such as embezzlement and bank debt, is also common. This ideology identifies this class of people as responsible for the crises in Iranian society. Examples include: Astral (2000); The Smell of Roses (Bū-yi gul-i surkh, 2001); Tapster (Sāqī, 2001); Ghazal (2001); A House Built on Water (Khānah-ī rū-yi āb, 2001); Honey Venom (Zahr-i ‛asal, 2002); The Winning Card (Barg-i barandah, 2003); Parkway (2007); Satan’s Impersonator (Muqallid-i shaytān, 2007); Rock, Paper, Scissors (Sang, Kāghaz, Qaychī, 2007); Canaan (Kan‛ān, 2008); Kalāgh Par (2008); Mr. Seven Colors (Āqā-yi Haft Rang, 2009); Doubt (Tardīd, 2009); Superstar (2009); 24th Street (Khiyābān-i bīst u chahārum, 2009); Hello to love (Salām bar ‛ishq, 2010); Crazy Rook (Rukh-i dīvānah, 2015); and Labyrinth (Hazār-tū, 2019).

In Labyrinth (2019), Amīr-‛Alī, the main character, is a member of the upper class. He is a young businessman with a notable goatee. He wears branded clothes, lives in a luxury apartment, and drives a BMW x3 class. Amīr-‛Alī has no control over his emotions and gets angry quickly and acts violently. He consumes alcohol and, while driving intoxicated, he causes the death of his friend Esfandiar, who was seated next to him in the vehicle. The incident prompts him to experience feelings of guilt, which ultimately result in his decision to marry his deceased friend’s wife, Nigār, and assume the role of a stepfather. The relationship between Amīr-‛Alī and Nigār is characterized by a lack of romantic affection and even a lack of a marital relationship. Amīr-‛Alī engages in a secret relationship with Bītā, his wife’s close friend, betraying Nigār.

Figure 5: Amīr-‛Alī and Nigār in Labyrinth (Hazār-tū), directed by Amīr-Husayn Turābī, 2019.

At the time of her first husband’s death, Nigār was pregnant. She disregarded her mother’s counsel to terminate the pregnancy, making motherhood a defining aspect of her character’s identity. She maintains a strained relationship with her new husband, deeming him an inadequate father due to his lack of paternity. This woman’s essentialist personality is evident in her perception of the father-child bond. According to her perspective, the biological father is the de facto father.

Bītā is a young, middle-class woman who engages in the design and production of clothing in her home. In the past, she was in love with Amīr-‛Alī, but she was unable to express her affections to him. Following the marriage of her favored man, she has worked to establish a relationship with him. Bītā becomes pregnant as the result of her clandestine relationship with Amīr-‛Alī; however, she undergoes an abortion in order to ensure the continued secrecy of their relationship. Upon learning that Amīr-‛Alī intends to immigrate from Iran to the United States with Nigār, she devises a scheme to steal Amīr-‛Alī’s son, thereby seeking to avenge Amīr-‛Alī’s perceived unkindness.

The movie’s portrayal of the upper-class couples suggests a lack of warmth and intimacy in their relationships. These individuals are depicted as violent, corrupt, and treacherous. The primary focus of the movie is the disappearance of Amīr-‛Alī and Nigār’s children and the subsequent arrival of the police to investigate the case. This central conflict is ideologically significant in that it presents an obstacle for this couple to migrate abroad. In the aftermath of the incident, the film depicts scenes in which Amīr-‛Alī and his wife hold each other accountable, leading to verbal altercations between the couple. This conflict affects the development of other relationships within the upper-class community. The movie’s title, Labyrinth, is an ideological choice that reflects the tragic complications experienced by the upper class. The resolution of this complex narrative occurs in the final sequence, where the stolen infant is left in a shed and the perpetrator of the crime is also discovered to be deceased. As a result, the shed in question will not be located by the police. The process of untying several knots and retying them reveals the anti-bourgeois ideology. Amīr-‛Alī’s brother-in-law clandestinely exploits this circumstance and extorts a sum of currency from Amīr-‛Alī. Upon the revelation of Amīr-‛Alī’s betrayal, his wife states her intention to divorce him, citing the discovery of a child as the precipitating factor.

Figure 6: Amīr-‛Alī and Bītā in Labyrinth (Hazār-tū), directed by Amīr-Husayn Turābī, 2019.

Overall, the movie can be described as a following an anti-bourgeois ideology, which attempts to portray the upper classes as violent, corrupt, and treacherous. This antagonism is a consequence of the class divide that exists in contemporary Iranian society. The movie’s portrayal of the economic situation in Iran is informed by the windfalls, the use of oil rents, and the unbridled inflation caused by US sanctions. These factors have contributed to a growing dissatisfaction with the status quo, which is reflected in the anti-bourgeois ideology that emerges in the movie.

Sympathetic Ideology

Since 2010, the effects of international sanctions against Iran’s nuclear program have intensified. The government’s ability to control the currency has decreased, and despite the liquidity, inflation has increased. This has led to a change in the economic status of various classes, with some families falling from the middle class to the lower class. While cinema audiences in Iran are typically from the middle class of society, movies depiciting the pooer condition of the lower classes have become popular. Moreover, among Iranians, the value of assisting the impoverished is widely recognized. Throughout history, Iranians have consistently regarded assisting the poor and orphaned as a religious and humanitarian obligation. Consequently, movies have been produced that espouse an ideology of empathy for the disadvantaged.

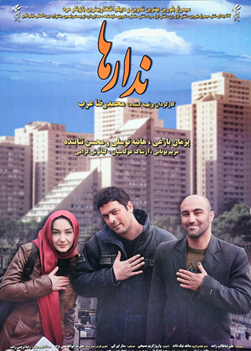

The term “sympathetic ideology” is employed here to describe a movie’s capacity to demonstrate identification with the plight of the impoverished. The intention of the ideology is to evoke empathy in the audience by illustrating the suffering and pain endured by the poor. Accordingly, the lower classes in many Iranian films from the last decades reside in old houses situated on the outskirts of the city. They wear outdated, ill-fitting, and unclean garments, and struggle to maintain their livelihoods. The inability to pay for necessary medical care, housing, and other basic necessities has placed them in a challenging position. The sympathetic ideology necessitates that the audience perceive the lives of these individuals in order to be motivated to provide them with assistance. Some examples include The Wall (Dīvār, 2008); Twenty (Bīst, 2009); Nothing (Hīch, 2010); The Broke (Nadārhā, 2011); Wednesday, May 9 (Chahārshanbah 19 Urdībihisht, 2015); Life and a Day (Abad u yak rūz, 2016); 21 Days Later (Bīst u yak rūz ba‛d, 2017); No Date, No Signature (Bidūn-i tārīkh, bidūn-i imzā’, 2018); 3 Puffs (Sih kām habs, 2023).

The Broke (2011) revolves around the actions of individuals belonging to the lower socioeconomic strata who decide to steal from the upper classes and redistribute the stolen goods to those in need, in a manner reminiscent of the legendary outlaw Robin Hood. The initial success of these actions is, however, short-lived, as the perpetrators are either apprehended by the police or killed.

Figure 7: From left to right, Mihrī, ‛Alī, and Mahmūd in The Broke (Nadārhā), directed by Muhammad Rizā ‛Arab, 2011.

The protagonist ‛Alī, also known as “‛Alī Bīkas” (lonely ‛Alī), was born in Ahvāz, joined the military, relocated to Tehran, and became an apprentice in a repair shop. When the film begins, he operates a motor vehicle, transporting passengers and generating income. Initially, he refrains from stealing from the rich, but eventually joins in. The narrator of the movie is Mihrī. She has lost her father and lives with her elderly mother in a rental property and is employed in a yarn factory. She is content to assist those in need. Mihrī remarks that she has a lot of work to do with these money-laden hyenas, referring to the rich. She is willing to take risks and embark on adventures. The third character is Mahmūd. Although he has a history of imprisonment, he carries a machete and is prone to violence and emotional outbursts, but his deafness, his inability to communicate verbally, and his childlike innocence are all qualities that elicit sympathy from the audience. All three characters rent apartments in old, run-down buildings and wear garments that are no longer in fashion. The living environment of these individuals exhibits their need for housing and medical care, and their lack of hope for any improvement in this situation.

The movie’s title, The Broke (Nadārhā), signifies a group lacking in property. This term functions as a metaphor, drawing parallels with the concept of the impoverished. It encourages the viewer to contemplate their own lives. The narrative begins with ‛Alī losing his job and Mihrī being on the verge of having their household items dumped in the street by the owner of the house. The two issues in question are ideological, as they draw attention to the livelihood issues faced by the lower classes. The resolution of these problems is contingent on the implementation of illicit actions. Furthermore, the movie contains numerous conversations that posit that the root of poverty in Iran is societal injustice. The resolution of the movie’s narrative involves the protagonists engaging in illicit activities, including theft. This include stealing from a construction company that sells housing at high prices, dentists that do not accept insurance, clothing stores, foreign car dealers, carpet sellers, and individuals who are both wealthy and morally corrupt. The stolen property is then distributed to the poor in order to ensure that justice is served. Ultimately, law enforcement officials apprehend the individuals portrayed in the film. The success of the police is guaranteed in many Iranian films. It appears that the filmmakers were compelled to adopt this particular ending due to the constraints imposed by censorship laws. Conversely, the film’s ideological perspective would reveal the filmmakers to be in sympathy with the lower classes as noble individuals who have no alternative but to take practical and, in some cases, illegal measures to escape their circumstances.

Interaction-confrontation ideology

In Iranian urban areas, there is a notable degree of social class diversification, with the exception of certain areas, such as those that are economically prosperous or situated on the periphery of cities. This phenomenon engenders interaction between disparate social classes, which the film industry often portrays. The relationship between different social classes is influenced by both subjective values and the objective reality of life. Similarly, social relationships between these groups are not always harmonious, and at times, they can be quite contentious. Iranian films have frequently depicted these interactions in accordance with a specific ideological framework. This ideology is concerned with the interaction or confrontation of people belonging to two different classes. It encompasses financial assistance from the upper class to the lower class, intellectual assistance from the lower class to the upper class, intermarriage between people from two classes, and the modification of class values. In some cinematic works, the interaction-opposition ideology espouses a position of support for one of the social classes, while simultaneously condemning or remaining silent about the other. In these movies, ideology can be contradictory. In the dialogue, actions, and events, themes such as the corruption of the upper classes, the delinquency of the lower classes, the pride of the upper classes, the regrets of the lower classes, and the moods of the middle class are raised in order to criticize “justice,” “wealth distribution,” and “class morality” in society. See, for example: Seven songs (Haft Tarānah, 2001); The Yellow Rose (Rawz-i Zard, 2002); Fever (Tab, 2002); Iranian Girl (Dukhtar Īrūnī, 2002); Fireworks Wednesday (Chahārshanbah-Sūrī, 2005); Lover (‛Āshiq, 2006); Unfaithful (Bī-vafā, 2006); The Guest (Mihmān, 2008); Western Doll (‛Arūsak-i Farangī, 2005); Distance (Fāsalah, 2010); Two Sisters (Du khvāhar, 2010); Another One’s House (Khānah-yi dīgarī, 2015); Appendix (Āpāndīs, 2017), Axing (Dārkūb, 2018); and, World War III (Jang-i Jahānī-i Sivvum, 2022).

In Appendix (2017), the story unfolds within the confines of a medical facility. Laylā arrives at the hospital to receive the results of her test and encounters their former neighbor, Zarī, and her husband, Rizā. Zarī experiences severe abdominal pain and requires immediate surgical intervention. The surgical procedure is completed, but complications arise, resulting in a Zarī slipping into a state of unconsciousness.

Figure 8: A still from Appendix (Āpāndīs), directed by Husayn Namāzī, 2017, highlighting the contrast between individuals from lower socioeconomic backgrounds, who are more inclined to physical violence, and those from middle-class backgrounds, who typically engage in conversation.

The narrative structure, under the influence of the film’s ideological framework, positions two individuals from divergent social backgrounds in opposition to each other, and the insurance book serves as a catalyst for the interaction between these two classes. Rizā, who has been unemployed for months and is unable to pay for his wife’s appendectomy, requests a health insurance card belonging to Laylā, a woman of middle class status, to provide them with the necessary funds. This interaction allows the audience to gain insight into the challenges faced by individuals from both socioeconomic backgrounds.

The film’s ideological perspective suggests that the male members of the lower socioeconomic class are characterized by a combination of traits, including zeal, helplessness, nervousness, and lawbreaking. For instance, Rizā must circumvent the law to obtain the funds needed for his wife’s surgery. A noteworthy sequence is one in which Rizā attempts to alter the photo of his wife’s insurance book, which has passed its expiration date, and Laylā’s book in the bathroom. He strikes the toilet wall in order to forge the document. This action metaphorically illustrates the misery of the lower class, for whom the taste of life is akin to dirt and excrement of other classes. Lower-class women are similarly vulnerable to the constraints of patriarchy, exhibiting characteristics such as helplessness, timidity, and victimhood. Zarī is so intimidated by her husband that she is unable to inform him that her employer is harassing her. This lack of communication between the couple ultimately results in a problematic situation. Rizā’s suspicion that his wife has betrayed him and subsequent attack on his sick wife are the result of his changing the answers of the two women’s test. Zarī goes into a coma, rendering her unable to defend herself.

The ideological framework of the film portrays middle-class individuals as polite, dutiful, and philanthropic. Laylā’s makes a conscious effort to maintain a polished and composed demeanor in her interactions with others. Despite concealing her pregnancy (and its termination) from her husband, a respectful relationship is evident between her and Muhsin. Muhsin is a courteous individual who endeavors to present himself as a model employee in the eyes of the hospital administrator, but he incurs disciplinary action due to the benevolence of his spouse towards the health insurance card.

The film’s resolution favors the middle classes. In the concluding sequence, the protagonist, a member of the middle class, alters the background image on her phone in order to accept her spouse as her new romantic interest. Concurrently, a male character from a lower socioeconomic background is taken to the detention center, which suggests that his marriage has been dissolved.

Conclusion

Although the concept of class was effectively buried by the fundamentalists following the Islamic Revolution due to its Marxist implications and the priority of religious identity, economic and cultural changes have caused class issues to resurface. The concept of class had been forgotten for an extended period. In other words, it had been buried. In contemporary texts, there appears to be a resurgence. This phenomenon can be likened to the reemergence of zombies from their interment. In place of religious identity, class identity emerged as a subject of interest once more, and began to make an impact in the film industry. The consequence of this was the production of numerous movies in the twenty-first century with a focus on class ideology. These ideologies target the upper class, sympathize with the lower classes, and evaluate the values of each class in the context of their interaction Consequently, the relationship between ideology and class is a profound and efficacious one within the modern Iranian cinema industry.

Cite this article

In Iranian cinema, the portrayal of social classes is influenced by ideology, as economic interests and cultural values are hidden behind class distinctions. Consequently, the way in which social classes are portrayed depends on the distribution of wealth in Iranian society and the characteristics of popular culture. The present study employs Antonio Gramsci’s theory of ideology and narrative analysis to demonstrate how ideology influences the representation of social class in twenty-first-century Iranian cinema. The analysis of selected works will demonstrate the existence of at least three distinct ideological orientations in Iranian cinema: anti-bourgeois, sympathetic, and interaction-confrontation. A thorough examination of the selected works reveals at least three distinct ideological orientations in Iranian cinema. Firstly, an anti-bourgeois ideology that opposes the lifestyle of the upper classes. Secondly, a sympathetic ideology that commiserates with the lower classes. Finally, we see an ideology of interaction-confrontation that pits two classes against each other and supports the values of one class over another. Consequently, the relationship between ideology and class is a profound and efficacious one within Iranian cinema.