Iran Is My Home (Īrān Sarā-yi Man Ast)

Figure 1: The first poster for the screening of Iran Is My Home (Īrān Sarā-yi Man Ast), directed by Parvīz Kīmiyāvī, 1998.

Introduction

Within the history of Iranian cinema, few films— either before or after the 1979 Revolution —have directly engaged with the complex legacy of Iranian literature or centered their narratives on Iranian poets. Parvīz Kīmiyāvī’s film, Iran Is My Home (Īrān Sarāy-i Man Ast) is a remarkable exception; the film ambitiously seeks to integrate ancient Iranian cultural symbols within the framework of modern and contemporary Iranian society. Its most distinctive feature lies in enabling medieval and premodern Iranian poets to materialize within historical settings such as caravanserais. The central narrative follows a young researcher’s struggle to publish a scholarly work on Iranian literary history, a task complicated by the constraint of state censorship. Yet, the film transcends the mere representation of the protagonist’s recurrent confrontations with the censor. His journey is a hybrid of reality and fantasy – an intellectual and existential odyssey that exposes the audience to the intricate layers of Iranian culture and the existential challenges it faces in the modern era. Kīmiyāvī masterfully constructs this cinematic world through five interwoven thematic pillars:

- Geography and environment (the desert juxtaposed with the city);

- Culture and intellectual heritage (the centrality of poetry);

- Political bureaucracy (the licensing apparatus governing publication);

- Material patrimony (architectural and archaeological heritage such as caravanserais and Persepolis, emblematic of the Iranian plateau’s physical legacy);

- Socioeconomic transformation (from pastoral traditions to nascent capitalism and global modernity, epitomized by the metro).

This deliberate synthesis of motifs underscores the film’s critical function: to serve as an aesthetic warning against the erosion of Iran’s cultural identity under the pressures of modernization and political regulation.

Produced in 1998, the film achieved significant critical recognition, receiving nominations for Best Director, Best Screenplay, and Best Production and Costume Design at the third Iran Cinema Celebration in 1999.1“Īrān sarā-yi man ast (film-i sīnimāʾī),” Wikijoo, accessed November 12, 2025, https://wikijoo.ir/index.php/ایران_سرای_من_است_(فیلم_سینمایی) The Rushd International Film Festival primarily focuses on educational and instructional films. It also won Best Film at the 30th Rushd International Film Festival in 2000. Despite this acclaim the film was never granted authorization for public theatrical release. In an interview conducted two years after the film’s completion, Kīmiyāvī described the experience as profoundly disheartening, attributing the film’s non-release to the instability of managerial positions, inconsistent decision making, and the involvement of inexperienced producers.2“Fīlmfārsī barāyi khudash yak sabk būd; Guftugū bā Parvīz Kīmiyāvī” Fasl’nāmah-yi Fārābī 37 (summer 2000): 212. The production also appears to have been plagued by financial problems. The production manager acknowledged that there had been extensive monetary problems during filming coupled with disagreements regarding the editing process between the producer, Muhammad Rizā Sarhangī, and the director.3“Mudīr tawlīd-i Īrān Sarāy-i Man Ast: Nimīkhāstīm bā Sākht-i īn fīlm bih pāyān birasīm,” ISNA, August 28, 2016, accessed November 12, 2025, https://www.isna.ir/news/Khorasan-Razavi-98627/مدیرتولید-ایران-سرای-من-است-نمی-خواستیم-با-ساخت-این-فیلم Kīmiyāvī himself later identified extensive financial disputes with the producer—in addition to his interference with the editing—as the primary reasons the film was ultimately archived at the Fārābī Cinema Foundation.4Ahmad Tālibī’nizhād, Bih Ravāyat-i Parvīz Kīmiyāvī (Tehran: Hikmat-i Sīnā, 2019), 188. Following its completion the film received invitations from international festivals. However, these screenings failed to materialize due to a lack of coordination between the producer and the director, along with other unresolved issues.5Ahmad Tālibī’nizhād, Bih Ravāyat-i Parvīz Kīmiyāvī (Tehran: Hikmat-i Sīnā, 2019), 192-193. These financial and legal disputes, compounded by the Iranian Cinema Organization’s refusal to grant a release license, resulted in an eighteen-year delay. The film was finally released on a limited basis in 2016.

The prolonged suppression of Iran Is My Home followed by its belated and restricted screening in a handful arthouse cinemas, ensured that the film neither received critical engagement at the time of its production nor appeared in scholarly discourse on Iranian cinema. It was only after these brief screenings that some critics, primarily in online platforms, introduced and reviewed it.6An example of these critiques can be found in this online article: “Nigāhī bih fīlm-i Īrān Sarāy-i Man Ast sākhtah-yi Parvīz Kīmiyāvī; Umīd-i Rastgārī Nīst,” Cinema Cinema, July 23, 2016, accessed November 12, 2025, https://cinemacinema.ir/news/نگاهی-به-فیلم-ایران-سرای-من-است،-ساخت/ Some of these critiques were notably ideological, often framed from an anti-intellectual perspective and, at times, couched in dismissive or derogatory language.7“Sar’gījah hā-yi abtar va rawshanfikrānah; Īrān Sarāy-i Man Ast: Haziyānī kih maʿlūm nīst tārīkh-i adabiyāt ast yā naqd-i sānsūr,” Fardanews, August 13, 2016, accessed November 12, 2025,https://www.fardanews.com/بخش-فرهنگ-96/553119-سرگیجه-های-ابتر-روشنفکرانه The film’s subject matter and subsequent reception suggest its alignment with an elitist strand of Iranian cinema, which helps explain its limited popular appeal. An audience survey reinforces this interpretation: the film earned an average score of just 4.2 out of 10.8“Muʻarrifī va Barrasī-i Fīlm-i Īrān Sarāy-i Man Ast,” Manzoom, accessed November 12, 2025, https://www.manzoom.ir/title/tt2906438/فیلم-سینمایی-ایران-سرای-من-است-1377 Beyond its esoteric theme, the eighteen-year delay in public release likely contributed significantly to this outcome by creating a generational gap between the film and its prospective audience.

Critics generally classify the film Iran Is My Home within the category of “experimental indigenous cinema,” a genre that demands from the viewer an active cognitive engagement rather than passive consumption. In this mode meaning emerges not from a linear narrative but through the interpretive labor of the audience, who synthesize the film’s disparate visual and conceptual elements.9Rasūl Nazar Zadāh, “Būmī’garāyī-i tajrubī, mustanad’garāyī-i zihnī; naqd-i fīlm-i Īrān Sarāy-i Man Ast,” Māh’nāmah-yi Fīlm 512 (2016): 97. After nearly two decades in storage, the film premiered in 2016 through the independent “Art and Experience” cinema initiative. This organization, despite its limited venues, aims to elevate cinematic literacy and promote non-commercial, artistically significant films in Iranian cinema.10Ahmad Tālibī’nizhād, Bih Ravāyat-i Parvīz Kīmiyāvī (Tehran: Hikmat-i Sīnā, 2019), 181.

The absence of an initial public screening, combined with internal disagreements among the crew, left the film vulnerable to criticism and deprived it of timely scholarly defense. When the film finally screened in 2016 across selected Iranian cities for review and critique, during a screening at the Huvayzah Cinema in Mashhad, Marziyah Qurayshī, the production manager, pointed out that the film was reaching audiences long after the death of some of its creators, including the producer, and many of its cast members. She also acknowledged that the filmmakers had anticipated the film’s limited commercial prospects, especially when compared with the popularity of directors like ‘Abbās Kiyārustamī, but had hoped it would resonate with intellectual circles.11“Mudīr tawlīd-i Īrān Sarāy-i Man Ast: Nimīkhāstīm bā Sākht-i īn fīlm bih pāyān birasīm,” ISNA, August 28, 2016, accessed November 12, 2025, https://www.isna.ir/news/Khorasan-Razavi-98627/مدیرتولید-ایران-سرای-من-است-نمی-خواستیم-با-ساخت-این-فیلم

Parvīz Kīmiyāvī’s return to Iran (after leaving the country following the 1979 revolution) was facilitated by political transformations in Iran, following the victory of reformists in the 1997 presidential election (Islāhāt Movement). The monotonous and ideological formulative character of Iranian cinema from the early 1980s prompted the Fārābī Cinema Foundation to initiate a program supporting innovative and diverse works. As part of this project, ten Iranian directors celebrated for their avant-garde approaches – including Kīmiyāvī, Khusraw Sīnā’ī and Muhammad Rizā Aslānī, came forward to develop new films. It was under these circumstances that Kīmiyāvī proposed Iran Is My Home, which was accepted.12Muhammad ‘Alī Razī, “Dar Sitāyish-i Farhang-i Ghanī; Naqd-i Fīlm-i Īrān Sarāy-i Man Ast,” Cinema Fārs, August 30, 2021, accessed November 12, 2025, https://cinema.gamefa.com/121029/در-ستایش-فرهنگی-غنی؛-تحلیل-فیلم-ایران-س/ Although he had visited Iran prior to this project, according to him, he had declined to produce a film due to his awareness of the severe censorship.13“Guftugū bā Parvīz Kīmiyāvī,” Naqd-i Sīnimā 8 (summer 1996): 207. According to Kīmiyāvī, the concept of integrating classical Iranian poets into a contemporary setting originated before his return from France as a means of challenging reductive European perceptions of Iranian history and civilization. In Iran Is My Home, this vision is fused with the realities of domestic censorship and the cultural anxieties of post-revolutionary Iran.14Muslim Mansūrī, Sīnimā va Adabiyāt: Musāhibah bā Dast Andar Kārān-i Sīnimā va Adabiyāt (Tehran: ‘Ilm, 1998): 142. Ahmad Tālibī’nizhād, Bih Ravāyat-i Parvīz Kīmiyāvī (Tehran: Hikmat-i Sīnā, 2019), 185. Finally, this film contains many themes and concepts, perhaps because the director thought it might be his last film in his homeland.15Ahmad Tālibī’nizhād, Bih Ravāyat-i Parvīz Kīmiyāvī (Tehran: Hikmat-i Sīnā, 2019), 183.

The Confrontation of Politics and Culture in Iranian Society

Kīmiyāvī’s film subtly and symbolically depicts the confrontation between culture and politics in post-revolutionary Iranian society. At the center of the narrative is Suhrāb Zamānī, a young researcher determined to publish his extensive research on Persian literature, who encounters a formidable obstacle: the Book Licensing Office of the Ministry of Islamic Guidance. In the 1980s following the Islamic revolution and during the war with Iraq, the government, under the pretext of fostering unity against external threats, imposed strict limitations of social and cultural freedoms, including restrictions on the publication of works deemed critical of or incompatible with official ideology. These constraints persisted for roughly a decade after the war (1988–1997) gradually easing with the rise of the Reformist government under Muhammad Khātamī. For a brief period, the publishing climate became more permissive. It was at the outset of this reformist era that Kīmiyāvī produced his film, reflecting on a recent past whose consequences remained palpable.

In Iran Is My Home Suhrāb seeks to publish his study on the intellectual legacy of major medieval Persian poets. However, the licensing officer at the Ministry of Islamic Guidance, who is effectively a censorship officer and whom we will refer to as such in this text, attempts to persuade him to alter the book’s content to align with state ideology. The film employs a distinctive narrative structure in which three temporal dimensions—historical, psychological, and contemporary—intersect fluidly. Suhrāb frequently becomes disoriented amid these overlapping timeframes during his imagined journeys, making the film’s editing central to conveying this temporal interplay.16Rasūl Nazar Zadāh, “Būmī’garāyī-i tajrubī, mustanad’garāyī-i zihnī; naqd-i fīlm-i Īrān Sarāy-i Man Ast,” Māh’nāmah-yi Fīlm 512 (2016): 96.

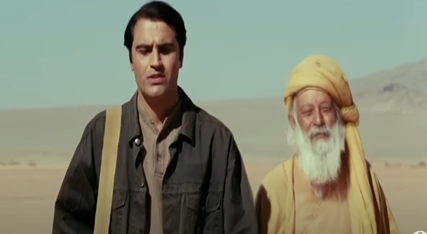

Figure 2: Suhrāb in the film Iran Is My Home (Īrān Sarā-yi Man Ast), directed by Parvīz Kīmiyāvī, 1998.

Within his imagination, rendered through surreal sequences, Suhrāb engages the censor in two major debates: the first concerning wine and the second concerning the concept of women in classical Persian poetry. These themes represent two cultural taboos targeted by the state—the prohibition of wine and the regulation of gender norms. True to the film’s central motif of spatiotemporal fluidity, these debates unfold not in the sterile setting of a government office but in an ancient caravanserai populated by actors portraying medieval poets. In one such scene, Mr. Safī, the censor’s assistant responsible for scheduling appointments, stands before the caravanserai calling out the names of poets, who then enter to recite verses relevant to the ongoing discussion. This creative device transforms an abstract literary debate into a vibrant, performative exchange, drawing the audience into a dynamic cultural dialogue rather than a purely academic discourse.

The first debate between Suhrāb and the censorship officer in the caravanserai centers on the representation of wine in Persian poetry. The censor accuses Suhrāb of neglecting the symbolic dimension of literary language, asserting—consistent with certain scholarly interpretations of the time—that references to wine by poets such as Khayyām and Hāfiz signify spiritual illumination rather than literal consumption. He supports his claim with examples from Sana’ī and Rumi, in whose works wine-drinking is portrayed as morally objectionable. Suhrāb counters with verses by Khayyām, Hāfiz, and Firdawsī, which unmistakably allude to the physical act of drinking. Their exchange, mirroring long-standing scholarly disputes, remains unresolved—yet, predictably, the censor’s interpretation prevails in practice.17For a recent, and relatively collective, discussion on this case, see: Dick Davis, Faces of Love (Hafez and the Poets of Shiraz) (New York: Penguin Books, 2013): xi-lxvi.

During Suhrāb’s second visit to the Ministry of Islamic Guidance, he encounters a young girl accompanied by her mother, seeking approval for her poetry collection. When she reads several of her poems—remarkably mature meditations on life and death—their gravity appears incongruent with her youth, and the unpolished acting lends the scene an air of artificiality. This episode may allude to the prominence of New Poetry in modern Iranian literature, though its purpose within the narrative remains ambiguous. Alternatively, it could underscore the deep-rooted cultural significance of poetry in Iranian identity, or signal the director’s thematic concern with women—a motif that emerges more explicitly in the second debate.

The second debate between Suhrāb and the censorship officer concerns Suhrāb’s chapter on women and their representation in Persian literary history. Drawing upon Firdawsī, Nāsir Khusraw, Sana’ī, Nizāmī Ganjavī, Saʿdī, and Jāmī, Suhrāb delineates the prevailing medieval perspectives on women. The censor, however, contests the claim of consistently negative portrayals, citing poems by modern poets such as Rahī Muʿayyirī and Vahīd Dastjirdī—sources outside the historical scope of Suhrāb’s study. When Suhrāb points out this anachronism, the censor remains unpersuaded, ultimately insisting on “revisions”—a euphemism for censorship—as the condition for granting publication approval.

Integrating classical cultural symbols with contemporary political phenomena

In the film Iran Is My Home, Kīmiyāvī seeks to reconstruct Iranian history, literature, and classical cultural symbols within the framework of modern Iranian society in the late 20th century. Kīmiyāvī’s intention, similar to his film The Mongols (Mughul’hā, 1973)18Javad Abbasi and Ghasem Gharib, “From Mongols to Television and Cinema,” In Cinema Iranica (Encyclopaedia Iranica Foundation, 2025), https://cinema.iranicaonline.org/article/from-mongols-to-television-and-cinema-the-mongols-mughulha-parviz-kimiyavi/, was to draw the past into the present.19Guftugū bā Parvīz Kīmiyāvī” Naqd-i Sīnimā 8 (summer 1996): 207. In this film, he redefines Iranian identity by relying on Persian poetry, incorporating the voices of five canonical Iranian poets, well-known to most Iranians. Poetry occupies a fundamental place in Iranian cultural life. Unlike the Aristotelian definition of poetry, which privileges imagination and emotion, Persian poetry functions as medium of thought, reflection and philosophical inquiry. The “Mushāʻirah” (poetry contest), staged in the film between Suhrāb and his father illustrate the centrality of poetry in Iranian cultural life at the time in which the film was made. Whether the father’s act of shaving his beard during this competition carries hidden significance remains ambiguous.

The choice of poets by the workers is both astute and in line with the views of the majority of experts on Persian literature and poetry, as well as Iranian culture and identity.20One of the most notable of these books is, Muhammad ʿAlī Islāmī Nudūshan, Chahār sukhangū-yi vijdān-i Īrān: Firdawsī, Mawlavī, Saʿdī, Hāfiz (Tehran: Qatrah, 1999). To express Suhrāb’s thoughts and ideas, Kīmiyāvī draws upon the words of Firdawsī, Khayyām, Rumi, Sa‘dī, and Hāfiz. Government censorship, however, compels him into an internal dialogue, where his memory animates the poems and personifies the poets themselves.21Rasūl Nazar Zadāh, “Būmī’garāyī-i tajrubī, mustanad’garāyī-i zihnī; naqd-i fīlm-i Īrān Sarāy-i Man Ast,” Māh’nāmah-yi Fīlm 512 (2016): 97. Alongside the five major figures, Khājū-yi Kirmānī (1290–1352), a celebrated poet from Suhrāb’s hometown, also features prominently. Additional poets appear in exchanges between Suhrāb and the censor, as reflected in the film’s distribution of citations: Saʿdī (14 poems), Hāfiz (14), Khayyām (8), Firdawsī (7), Rumi (7), Khājū (5), Sanāʾī (2), and several others—including Manūchihrī Dāmghānī, Nāsir Khusraw, Niẓāmī Ganjavī, Shaykh Mahmūd Shabistarī, ʿAbd al-Rahmān Jāmī, ʿUbayd Zākānī, Sāʾib Tabrīzī, Īraj Mīrzā, Rahī Muʿayyirī, and Vahīd Dastjirdī—represented by a single poem each.

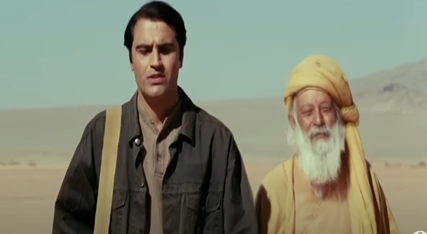

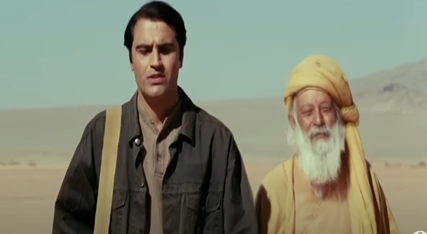

Figure 3: Suhrāb recalls Khayyām. Still from Iran Is My Home (Īrān Sarā-yi Man Ast), directed by Parvīz Kīmiyāvī, 1998.

According to Kīmiyāvī he studied classical Persian literature for three years to write the screenplay and weave the poet’s verses into the dialogue.22Ahmad Tālibī’nizhād, Bih Ravāyat-i Parvīz Kīmiyāvī (Tehran: Hikmat-i Sīnā, 2019), 189. The film’s fluid conception of time, achieved by dissolving temporal boundaries, allows Suhrāb’s recollections of poetry to take shape as physical presences. Each time he recalls a verse, the poet materializes before him—visible only to Suhrāb. Despite its classical foundations, Iran Is My Home engages directly with contemporary issues, most notably censorship. It also alludes to more recent events, such as the Iran-Iraq War. Following the second debate between Suhrāb and the censorship official, on his way back to Kerman, he encounters the corpse of a soldier killed in the Iran-Iraq war, a moment visually reminiscent of the Karbala battlefield, the site of the dramatic martyrdom of the third Shia Imam. This fallen soldier is one of the passengers who was with Suhrāb in his car, and Suhrāb is deeply affected by the scene of his death. In this battle scene, the Iranian national flag, flags bearing the names of Imām Husayn and ʿAbbās ibn ‘Alī – two great martyrs in Shia Islam j – and a Quranic verse about jihad (“Help from Allah and victory is close”, part of verse 13 of Surah Al-Saff), which was widely used during the Iran-Iraq war. In another symbolic scene, the five poets traverse the desert, initially scattered but ultimately converging. Viewed from a distance, their movements evoke the emblem of Allah added to the Iranian flag after the Revolution, symbolizing the convergence of divergent voices into a shared cultural identity.

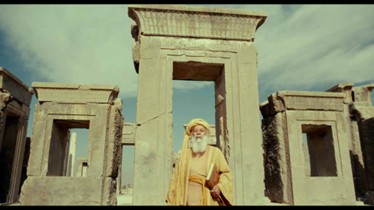

The film’s fluid narrative allows characters to move from one place to another without logical sequencing between scenes. For example, poets suddenly appear at Persepolis during Suhrāb’s desert wandering despite the site’s geographic distance from Kerman-Tehran route. The prominence of Persepolis as a national symbol seemingly compelled its inclusion. Yet the recited poems by Khayyām and Hāfiz emphasize impermanence and the fleeting nature of worldly power rather than grandeur and pride. Strikingly, Firdawsī, whose epic Shāhnāmah celebrates Iran’s heroic past, does not recite verses in this setting, a decision possibly linked to censorship.23“Hamah jā-yi Īrān sarā-yi man ast/chu nīk u badash az barāyi man ast.” The original poem by Firdawsī is as follows: “Kih Pūr-i Farīdūn niyā-yi man ast/hamah shahr-i Īrān sarā-yi man ast.” See Abū al-Qāsim Firdawsī, Shāhnāmah, vol. 2, ed. Jalāl Khāliqī Mutlaq (Tehran: Markaz-i Dāʾirat al-Maʿārif-i Buzurg-i Islāmī, 2012): 92. Since the director has not commented on any potential changes made to the film to obtain a license, we don’t know more about whether this or other instances of censorship or additions have existed. Similarly, in a scene where the censor’s secretary calls out the names of people who have come to the Ministry of Guidance to obtain a permit, they call out the name Hūshang Vazīrī. He was a communist figure from before the 1979 revolution and the editor-in-chief of the London-based newspaper Kayhān after the revolution.

Figure 4: Khayyām represented at Persepolis. A still from Iran Is My Home (Īrān Sarā-yi Man Ast), directed by Parvīz Kīmiyāvī, 1998.

Kīmiyāvī’s intelligence in symbolism is also evident in the casting of the censorship officer. Sa‘īd Pūr-Samīmī is the most well-known actor in this film, playing the role of the censorship officer. It’s interesting to note that at the time the film was made, he was the deputy head of the House of Cinema (under Dāvūd Rashīdī), an institution that acted as a liaison between the government and filmmakers. It’s possible that Kīmiyāvī was aiming for a kind of symbolism with this fact. A key point in the censorship officer’s dialogue is that he considers himself empathetic toward Suhrāb and repeatedly says the common and clichéd phrase in Iran, “I am a subordinate, and I am excused.” In reality, Kīmiyāvī, whether intentionally or not, reminds us that the primary censors in Iran’s cultural institutions are unseen. An individual within the bureaucracy, acting on their behalf, announces the censorship cases—someone who does not believe in what they are doing. This separates most of the people from the government. Furthermore, in the literary debate at the caravanserai, the censorship officer even transforms into a literary figure who passionately delivers the responses of the invisible censors who reviewed the book. Ultimately, the film serves as a cultural odyssey, exploring the long history of cultural censorship in Iran. This deeply rooted issue has historically led to tragic consequences. For example, some of Iran’s most revered mystics and cultural figures, such as Husayn ibn Mansur al-Hallāj, were executed for openly expressing their beliefs and refusing to self-censor.24Ahmad Tālibī’nizhād, Bih Ravāyat-i Parvīz Kīmiyāvī (Tehran: Hikmat-i Sīnā, 2019), 182.

The fluidity of time and space in this film is reminiscent of the concept of “journey through horizons and souls” (sayr-i āfāq va anfus) in Iranian mysticism. This spiritual tradition emphasizes not only a physical journey to achieve enlightenment but also a profound mental and spiritual one for the growth of the human soul. The main character, Suhrāb, who is steeped in the world of Persian poetry, appears to embark on both a physical and spiritual journey. While his physical journey takes him from Kerman to Tehran to obtain a book license, he simultaneously undertakes a spiritual odyssey with great Iranian poets, engaging in a “journey of spiritual wayfaring” (sayr va sulūk) through the desert. Kīmiyāvī’s film is imbued with a sense of mystery, largely due to the skillful use of cinematography and editing that helps convey these complex ideas. For instance, in one scene, poets recite their verses among the ruins of Persepolis, while the camera moves thoughtfully over the historical carvings and crumbling structures. Another example is the camera’s movement from the depths of a Qanāt (underground water channel) toward its opening, revealing an old woman sitting with her back to the light, her veiled figure slowly being enveloped by the darkness of the Qanāt’s entrance.25Rasūl Nazar Zadāh, “Būmī’garāyī-i tajrubī, mustanad’garāyī-i zihnī; naqd-i fīlm-i Īrān Sarāy-i Man Ast,” Māh’nāmah-yi Fīlm 512 (2016): 97.

The documentary-drama style of the film aligns with Kīmiyāvī’s mode in his previous works such as P Like Pelican (P Misl-i Pilīkān, 1972) and The Garden of Stones (Bāgh-i Sangī, 1976) of which he is considered one of the first innovators in Iranian cinema. The main characteristics of docu-drama are the use of non-professional actors (ordinary people), natural outdoor locations, sunlight, and a handheld camera—features that Kīmiyāvī used in both The Mongols and Iran Is My Home. As one of the most significant figures of the Iranian New Wave, Kīmiyāvī often used non-professional actors to express his ideas and influenced famous directors like ‘Abbās Kiyarustamī. Here, as in his other works, despite the importance he places on national and local identity, Kīmiyāvī doesn’t seek to turn his actors into heroes or legends, which is why he chose non-professionals.26Rasūl Nazar Zadāh, “Būmī’garāyī-i tajrubī, mustanad’garāyī-i zihnī; naqd-i fīlm-i Īrān Sarāy-i Man Ast,” Māh’nāmah-yi Fīlm 512 (2016): 96. Kīmiyāvī, in an interview before producing Iran Is My Home, noted that all of his films except Ok Mister (1979) were documentaries.27“Guftugū bā Parvīz Kīmiyāvī” Naqd-i Sīnimā 8 (summer 1996): 200. In the middle of Iran Is My Home he further gives his film a documentary-like, docu-drama feel by bringing up the old custom related to dried-up Qanāts in Kerman.28Rasūl Nazar Zadāh, “Būmī’garāyī-i tajrubī, mustanad’garāyī-i zihnī; naqd-i fīlm-i Īrān Sarāy-i Man Ast,” Māh’nāmah-yi Fīlm 512 (2016): 97.

A further innovation is his casting of the same actors in dual roles, as both classical poets and contemporary travelers. Thus, Firdawsī, Khayyām, and Saʿdī appear simultaneously as passengers in Suhrāb’s car. The director masterfully aligns the personalities of these modern characters with the philosophical content of the poems written by their historical counterparts. This technique is highlighted when the car breaks down on Suhrāb’s return trip. The passengers react in a manner reminiscent of the poets they play. The passenger who portrays Saʻdī in other scenes scolds the driver (who plays Firdawsī), saying, “I told you to check the car before the trip, but you were negligent.” The passenger playing Khayyām calmly counters that such issues are simply a natural part of life and not worth getting worked up over. Through these dialogues the film brings the philosophies of Saʻdī, who emphasized wisdom and caution, and Khayyām, who championed a more carefree, in-the-moment approach to life, into the modern era.

Desert as a symbol of Iran and cultural complications

Kīmiyāvī’s sustained attention to natural landscapes, particularly desert, is evident throughout his films. Iran Is My Home opens in the desert, and through numerous extended sequences, remains in that environment until the film’s conclusion. In the opening scene, the protagonist Suhrāb walks across the desert while chanting verses from five canonical Persian poets, who themselves appear and recite their verses. For Kīmiyāvī, the desert functions as a symbolic space in which human endeavors are rendered futile; the characters’ disorientation within its barren expanse dramatizes this theme. He had earlier employed the same symbolic strategy in The Mongols (1973).29Javad Abbasi and Ghasem Gharib, “From Mongols to Television and Cinema,” In Cinema Iranica (Encyclopaedia Iranica Foundation, 2025), https://cinema.iranicaonline.org/article/from-mongols-to-television-and-cinema-the-mongols-mughulha-parviz-kimiyavi/ At the same time, given that deserts constitute a substantial portion of Iran’s territory, their presence in a film explicitly concerned with representing the nation seems almost inevitable. Kīmiyāvī also foregrounds drought, one of the most persistent natural challenges of the Iranian plateau. In the film, Firdawsī, reimagined as a modern taxi driver, warns that drought has historically destroyed settlements and disrupted the lives of rural and desert communities. Finally, it is not clear if there is any connection between desert and cultural wilderness in the time of production or not.

To foreground Iran’s climatic conditions, Kīmiyāvī situates Suhrāb’s hometown in Kerman, one of the country’s most arid provinces. The protagonist repeatedly travels between Kerman and Tehran in pursuit of a publication license for his book. During these journeys—filmed on desert roads in a dilapidated car with fellow passengers—Suhrāb is accompanied by medieval poets, most notably Khvāju-yi Kirmānī, who embodies the city’s cultural legacy. In one scene, Hāfiz̤ recites poetry at the Bam Citadel, acknowledging his own indebtedness to Khājū-yi Kirmānī.

Caravanserai: From Refuge to Cultural Metaphor

The caravanserai, an enduring feature of Iranian architecture and material culture, acquires special resonance in relation to the desert. Kīmiyāvī highlights this motif in Iran Is My Home just as he had in The Mongols. Their abundance across Iran, their frequent abandonment, and their preservation made caravanserais both accessible and evocative filming sites. Significantly, Kīmiyāvī reused the same caravanserai he had filmed 25 years earlier. By choosing this site to represent the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance, he employs a deliberate metaphor: the caravanserai becomes a symbolic courtroom where debates unfold. More broadly, the caravanserai evokes the Iranian cultural imagination of perpetual transience—an unstable space of arrivals and departures, mirroring the precariousness of cultural life.30Hasan Anvarī, Farhang-i Kināyāt-i Sukhan, vol. 2 (Tehran: Sukhan, 2005): 1222.

Iranian Heritage: From Monuments to Qanāt Rituals

Beyond caravanserais and Persepolis, Kīmiyāvī integrates other iconic markers of Iranian civilization into the film’s geography and locations, especially those tied to Kerman. The Bam Citadel, one of Iran’s world heritage sites, provided him the opportunity to shoot some scenes. Within its walls five great Persian poets recite their poems. Iran Is My Home is one of the last films recorded at the Bam Citadel before the devastating earthquake of 2003 and its widespread destruction, which makes the film a historical document in its own right.

While depicting Suhrāb’s journey, Kīmiyāvī also gives a nod to Iranian music. On his second return journey from Tehran to Kerman, as Suhrāb becomes separated from the other passengers, an old man joins the group. He is a surnā (an ancient wind instrument) player. The surnā is played in various regions of Iran, but the instrument’s features differ from one region to another. The passengers, who have given up hope of finding Suhrāb, ask the old Kermani surnā player to play the instrument, hoping Suhrāb will hear it and appear. The old man plays the surnā, but there is no sign of Suhrāb. The surnā player gets off after a while to go to a village to perform at a wedding ceremony. From here the film takes the audience to another Iranian world heritage site, the Qanāt. It is revealed that the wedding is actually a traditional and lesser-known ceremony carried out in some parts of Iran (including Kerman and Khurāsān). It was held to bring water back to a dry Qanāts, a practice that continued until recently.31Javad Abbasi, Mīlād Parniyānī, Jamshīd Qashang, Tārīkh-i Khushk’sālī dar Khurāsān Razavī (Mashhad: Intishārāt-i Jahād-i Dānishgāhī, 2024): 396. When Suhrāb reaches the Qanāt’s well, in a sequence , local women, gathered there for the ceremony appear in main story, and explained the details to him. The sequence, ethnographically rich, could stand alone as a documentary.32Ahmad Tālibī’nizhād, Bih Ravāyat-i Parvīz Kīmiyāvī (Tehran: Hikmat-i Sīnā, 2019), 184.

Tradition and Modernity: From Qanāt to Metro

In the final stage of his wandering in the desert, Suhrāb encounters women recounting the story of Suhrāb ‘Alī, who has been living inside the Qanāt for seven years and will not come out. The women explain that Suhrāb ‘Alī is a man who was designated the “Groom of the Qanāt” in a ritual that failed to restore water, and has lived reclusively underground ever since. After hearing the story, Suhrāb decides to go into the well and help Suhrāb ‘Alī. It seems that he is manifested as Suhrāb’s doppelgänger at the bottom of the Qanāt.33Rasūl Nazar Zadāh, “Būmī’garāyī-i tajrubī, mustanad’garāyī-i zihnī; naqd-i fīlm-i Īrān Sarāy-i Man Ast,” Māh’nāmah-yi Fīlm 512 (2016): 97. However, the character of Suhrāb ‘Alī is more than just a psychotic person or a doppelgänger for the researcher; other points are hidden in his character, name, and actions. With Suhrāb ‘Alī, Kīmiyāvī attempts to both symbolize the fate of the main character and allude to Iranian mythology. The hybrid name “Suhrāb ‘Alī” fuses pre-Islamic mythology with Shi’i devotion, encapsulating Iran’s cultural contradictions.

The dried Qanāt symbolizes the decline of cultural heritage. It eventually transforms into a metro tunnel, dramatizing the erosion of tradition by modern urban life —a constant concern for Kīmiyāvī. Additionally, the drying up of the Qanāt wells may be linked to censorship, as it represents a departure from the source of ancient Iranian literature and culture.34Rasūl Nazar Zadāh, “Būmī’garāyī-i tajrubī, mustanad’garāyī-i zihnī; naqd-i fīlm-i Īrān Sarāy-i Man Ast,” Māh’nāmah-yi Fīlm 512 (2016): 97. The dried-up Qanāt, which has been converted into a metro, suddenly becomes a symbol of Iranian history and civilization, with symbols visible on the train cars. In this strange scene, the train cars are transformed into the different periods and dynasties that ruled Iran, and the Achaemenid, Safavid, Qājār, and Pahlavī train cars pass in front of Suhrāb. In these fleeting scenes, the director tries to show the audience the most important icons of each dynasty; Achaemenid with the carvings of Persepolis, Safavids with a tār (a musical instrument) and Qizilbāsh, mistakenly wore blue hat instead of red hats. The Qājār train car aims to present a picture of a dark era: Āqā Muhammad Khan Qājār, the founder of the Qājār dynasty, holds two human skulls, while a number of women in black veils (chador) weep for the dead, and other Qājār courtiers burn books and documents. On the Pahlavi train car, a person with their lips sewn shut is visible, which could be a reference to Farrukhī Yazdī and his lips being sewn shut in prison, which may refer to the prevalence of repression and censorship during this era.

The final scene of the film also reflects Kīmiyāvī’s perception of the cultural situation in Iran at the time of the film’s production. Suhrāb, en route to the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance again gets into a taxi, driven by director Kīmiyāvī. As the taxi moves people on the street call out their destination street names, all of which are named after the famous Iranian poets, but the driver does not pick them up. By each street name, a related poet appears in the passenger seat of the taxi. At the same time, a radio broadcaster reporting on Tehran’s traffic announces the street names and describes the heavy traffic as a familiar problem in the city. It seems that the director suggests that, by this time, people remember only the names of historical cultural figures like Ghazzālī, Rūdakī, Abū Sa‘īd Abī al-Khayr, Manūchihrī Dāmghānī, and Khāqānī, while their teachings are largely ignored.

Figure 5: Final shot of the film Iran Is My Home (Īrān Sarā-yi Man Ast), directed by Parvīz Kīmiyāvī, 1998.

Cultural Satire and Economic Constraints

After enduring censorship Suhrāb receives a publication permit but is denied access to government-subsidized paper, forcing him toward the private marketplace. Kīmiyāvī satirizes this final obstacle—the economic barrier to cultural production—through humorous imagery such as poets pedaling on a five-seated bicycle while reciting verses on independence. A meeting with a profit-driven merchant further underscores the conflict between cultural integrity and materialist priorities. The intervention of Khāju-yi Kirmānī, whose poetry stresses divine reliance, and Saʿdī, whose Gulistān criticizes mercantile greed, deepens this critique. Ultimately, despite his efforts, Suhrāb cannot publish his life’s work, and the film concludes with images of futility and despair in the desert—his fate paralleling the tragic Suhrāb of the Shāhnāmah.35Ahmad Tālibī’nizhād, Bih Ravāyat-i Parvīz Kīmiyāvī (Tehran: Hikmat-i Sīnā, 2019), 183.

Conclusion

The central theme of Iran Is My Home is the fate of Iranian culture and civilization amidst the tension between tradition and modernity from an ideological administration. Kīmiyāvī’s cultural concerns, evident since the production of The Mongols in the 1970s, resurfaces here with sharper focus: whereas television once symbolized the encroachment of modernity, now the urban-industrial environment—exemplified by the metro, combined with censorship, threatens to obliterate traditional lifeways, from qanāts to poetry. The film thus situates itself within a larger discourse on Iranian identity, emphasizing Kīmiyāvī’s lifelong commitment to cultural preservation. Laden with layered symbolism, historical allusions, and ethnographic detail, Iran Is My Home emerges as both a cinematic meditation on Iranian identity and a summative work, perhaps conceived by the director as his final contribution to national cinema.

Cite this article

The film Iran Is My Home (Īrān Sarāy-i Man Ast, 1998) stands as one of the most avant-garde and distinctive works in Iranian cinema during the final decade of the 20th century. Like many of Parvīz Kīmiyāvī’s other works, it explores the tension between tradition and modernity, and examines the threats facing Iranian culture amidst government censorship and the transformative forces of the modern world. The narrative follows Suhrāb Zamānī, a young writer from Kerman, who is researching the history of classical Persian poetry for a book he intends to publish. His journey to Tehran to obtain publishing approval takes an unexpected turn when he becomes lost in the desert. During this arduous passage, classical Persian poets—whose verses inhabit Suhrāb’s consciousness—miraculously appear to guide and accompany him. The film’s central tension is the clash between Suhrāb, who represents intellectual freedom and an unorthodox engagement with classical Persian literature, and a Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance official, who embodies the state’s ideological control. The film deliberately disregards historical chronology, gathering eminent Iranian poets within an ancient caravanserai, where they witness the exchanges between Suhrāb and the censor. Throughout his journey Suhrāb is accompanied by the spirits of five canonical poets, whose timeless verses echo in his mind. Kīmiyāvī’s film articulates a profound concern for the erosion of traditional Iranian customs. This anxiety culminates in a symbolic parallel between the Qanāt and the metro tunnel, reinforced by the visual destruction of ancient manuscripts. In its poignant closing scene, Kīmiyāvī himself appears as a Tehran taxi driver, transporting the researcher to his destination. From the director’s perspective, the enduring legacy of Iran’s celebrated poets is often reduced to the naming of streets—an ironic commentary on cultural memory in contemporary society.