Iranian Cinema and Fīlm-Fārsī: Filming Locations as a Defining Feature of the Pre-Revolutionary Era (1930–1978)

The choice of location was a crucial aspect in the creation of most Iranian films from the 1930s to the end of the 1970s. These locations depicted in Iranian cinema become significant parts of the story in and of themselves, offering unique windows into the everyday life and culture of the pre-revolutionary period, as well as the richness and significance of Iranian history and culture overall. Film locations provided backdrops and shelter, served as sites for rituals, and were more often than not integral to the story, representing specific aspects of Iranian society and culture. As well, given their ubiquitous if non-speaking presence in Iranian cinema, film locations were not only physical spaces but also symbols of social interaction, religious practices, and familial dynamics, all of which added depth and intrigue to the narrative.

Over time, the locations used in the pre-revolutionary Iranian cinema have become vital elements in the films themselves, as important as the directors, producers, actors, and others involved in their creation. Indeed, it is impossible to watch a movie from the period and not mention one or more of these locations, including:

- Qahvah’khānah (coffeehouse or teahouse), representing socio-cultural life,

- Zūr’khānah (traditional place for sports), representative of social and physical life,

- Hammām (bathhouse), indicative of communal bathing and socializing,

- Ziyārat’gāh (places of worship, mosques), depicting religious and spiritual significance,

- Khānah (family home), the place of gathering, refuge, love, and stability, and

- Qabristān (cemetery), representing the end of life, and the fragility and decadence of material life.

In what follows, I attend to each of these important types of film locations in this vibrant period of cinema in Iran. I showcase each type and their various aspects (especially concerning the khānah), through examples with still images from relevant films of the era. I also employ insights and observations drawn from travellers, historians, and others who have recognized the vital import of these various spaces to Iranian society and culture through the ages into the pre-revolutionary period. In so doing, this article offers an overview of the important roles and influences that these particular locations, settings, spaces, buildings, and architecture—and the symbolic, social, cultural, and even political meanings attached to them—have had and continue to play in Iranian cinema.

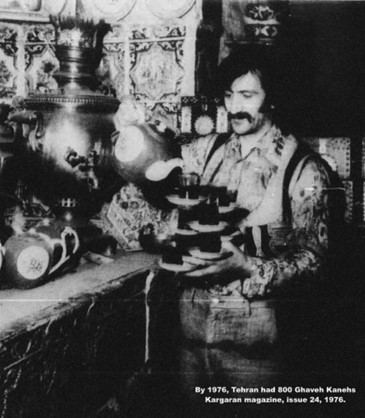

Qahvah’khānah: The Typical Filming Location in Iranian Cinema

Iranians’ most popular amusement spots of the 19th century were the Qahvah’khānahs, which were situated in the gardens and provided tea and narghile. In the summer, ice cream was also sold… A basin was located in the center of the Qahvah’khānah, and people would sit on coffee house beds surrounding the pool… An open space was provided for artists to practice and perform their dance, singing, drama, or poetry reading. The Naqqāls, who were storytellers, were also present. Thus, the Qahvah’khānahs were the first places where people gathered and expressed themselves through oral and artistic means.1Hamīd Shuʿāʿī, Sadā-yi pā…: Nazarī guzarā bih tafrīh va sargarmī-i mardum va tārīkhchah’ī az fīlm-i Īrānī va sīnimā dar Īrān (The Sound of Footsteps…: A Brief Overview of Iranians’ Recreation and Entertainment and a History of Iranian Film and Cinema in Iran) (Tehran: Sipihr, 1973), 18-19. Note that naqqālī is a narrative form of performance art which combines storytelling, acting, and singing and is one of the oldest forms of traditional Iranian theatre. Thus, a Naqqāl is a performer of naqqālī who, as a kind of “one man show,” narrates, performs the roles of various characters, and sings for the live audience. As further noted by Shuʿāʿī:

“The Naqqāls were well-versed in the poems of the Shāh’nāmah (The Book of Kings) and could recite or sing them without fail. Religious Naqqāls [called also pardah-khānī], included those who quoted and spoke about religious events, such as the Karbala tragedy. The Naqqāls had a significant impact on the people. The Qahvah’khānah, which had a skilled Naqqāl, were consistently filled with people. […] The Naqqāls performed all the characters in the story on their own and relied heavily on human emotions, able to make the audience laugh or cry with ease.” See Shuʿāʿī, Sadā-yi pā…, 8-9.

The first Iranian film, Dukhtar-i Lur (Lor Girl, 1932), marked the beginning of the Qahvah’khānah’s role in Iranian cinema. This historical landmark, with its unique architecture and cultural significance, soon became a popular and often-used filming location. Further, its presence in early Iranian films set a precedent for its continued use, establishing it as a symbol of Iranian cinema’s connection to its cultural roots.

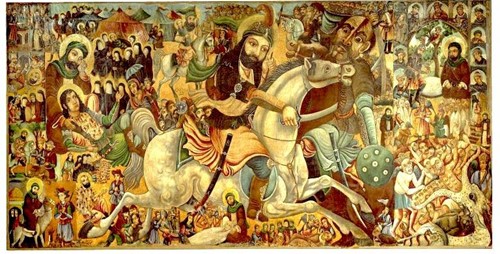

Figure 1. A painting of naqqālī depicting the story of Rustam and Sohrāb from the Shāh’nāmah (The Book of Kings).

Figure 2. A painting of pardah-khānī illustrating ʿAbbās ibn ʿAlī at the Battle of Karbala, by the Persian painter ʿAbbās al-Mūsavī.

At first, this place was a traditional gathering and gossip spot for men, where they would smoke hookahs and drink coffee. Over time, coffee was replaced by tea, but these locations continued to be referred to as the House of Coffee (i.e., Qahvah’khānah). These coffee-turned-tea houses are glowingly described by the seventeenth- and eighteenth-century French traveller Jean Chardin in his book Voyage en Perse (Travels in Persia): “The most stunning places in towns are usually Tea Houses that are large, spacious and have elevated drawing rooms of varying shapes. They serve as meeting points and entertainment venues for the locals.”2Jean Chardin, Voyage en Perse (Travels in Persia) (Phébus, 2007), 142.

The Qahvah’khānah has been a male space in Iran since the beginning of the seventeenth century, and it has not changed much since then.3Initially, women did not express an affinity for this male locale and sought to make their displeasure known in a rather forthright manner. A comparison of the testimonies of Orsolle, Wills, and Edward Browne in 1888 with those of the Iranians suggests that the closure of cafes at the end of the 19th century was due to a protest by Iranian women against the idleness of men (idleness and, implicitly, the widespread consumption of opium and its harmful effects). See Aladin Goushegir, “Le café en Iran des Safavides et des Qājār à l’époque actuelle” (Coffee in Iran from Safavid and Qājār to the Present Day), in Contributions au thème du et des Cafés dans les sociétés du Proche-Orient (Contributions to the Theme of Coffee in Middle Eastern Societies), ed. Hélène Desmet-Grégoire (Aix-en-Provence: Institut de recherches et d’études sur les mondes arabes et musulmans, 1992), 67. As noted by Aladin Goushegir: “Cafes are permanently present in Iran as a masculine public area. Women have only been able to enjoy public spaces since the second half of the twentieth century, when cafe-restaurants or cafe-pastries were introduced, particularly in Tehran.”4Goushegir, “Le café en Iran des Safavides et des Qājār à l’époque actuelle,” 69.

While undeniably restricted in terms of gender, the Qahvah’khānah was a unique space for conversation, a place where any thought could be expressed without fear of embarrassment. In an era before the press or radio, the Qahvah’khānah stood as the sole arena for exchanging, communicating, and receiving information, where free expression was not just exceptional, but a rare and cherished privilege. As Chardin further remarks, “There is conversation because that’s where the news is spouted, and where politicians freely criticize the government.”5Chardin, Voyage en Perse, 142. In addition, and again from Goushegir, it is clear that these establishments drew the ire of authorities who sought to control those who employed them as spaces of communication, critical thought, and discussion. As Goushegir writes, “Tavernier mentions political discussions in Isfahan cafes during the seventeenth century. A situation that was managed by the authorities. Following the king’s directive, a cleric was to come and deliver a speech, and at the end, encourage customers to leave the cafe and go to work.”6Goushegir, “Le café en Iran des Safavides et des Qājār à l’époque actuelle,” 70.

These gathering places were also hotbeds of art and popular culture, particularly in the latter half of the nineteenth century and the start of the twentieth century. As noted in the opening epigraph to this section by Hamīd Shuʿāʿī, one of the most significant cultural phenomena was naqqālī (storytelling). In this way, one can understand how the Qahvah’khānah, a type of cafe theater, emerged as a precursor to the cinema—no doubt due in part to the fact that Naqqāls, the storytellers, often used images as one of their primary tools of narration (see Figures 1 through 4). These elaborate oil paintings, sometimes spanning up to ten meters, served as visual aids for their tales; while the Naqqāl would narrate the story, they would use the appropriate picture to enhance the narrative.7The traditional art of “storytelling,” known in shows such as naqqālī or pardah-khānī, has been an essential factor in the integration of cinema in Iran since the very beginning of motion-picture production in the era of silent films. Iranian audiences liked their films told to them by a narrator (storyteller), so there was always one in the screening room. This person did not only translate the commentary of the silent movies, but he also went further—for instance, in foreign movies, the narrator would give Persian first names to the characters or change the stories altogether. However, while very popular in their time, these performances could not resist the invasion of cinema, and especially television, into the cultural lives of Iranians. With the advent of television in particular, the Naqqāl was gradually replaced by these electronic devices.

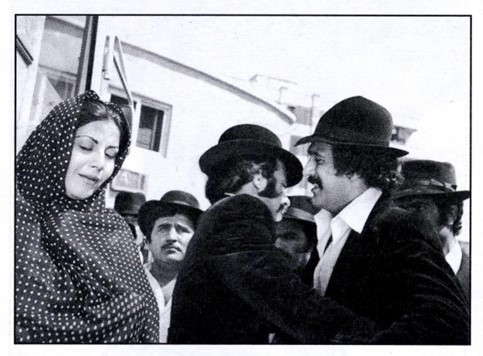

Figures 3. The advent of the Tus Festival (Jashnvārah-yi Tūs, 1975) saw a resurgence in the popularity of naqqālī in the Qahvah’khānahs. Photo from the newspaper Rastākhiz-i Kārgarān 24 (1975): 31.

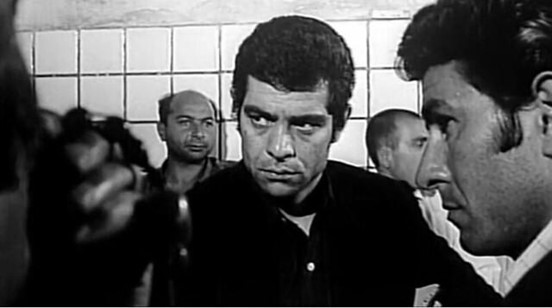

Figures 4. Naqqālī in Riqābat dar shahr—also called, Junūb Shahr (South of the City, 1958) directed by Farrukh Ghaffārī.

Figure 5. An article in the Rastākhīz newspaper about Qahvah’khānah, published in 1978, and titled “The Youth Are Fond of Qahvah’khānah.”

The Modern Café

In Iranian cinema, two types of café can broadly be distinguished: the traditional café serving tea (e.g., the Qahvah’khānah) and the modern café serving alcohol. The Second World War and the subsequent entry of the British and Russian armies into the country necessitated the adaptation of the Qahvah’khānah to the preferences of foreign soldiers, their new “clientele.” Traditional cafe proprietors began modernizing their establishments in response to the influx of these new “guests” (i.e., foreign soldiers). This entailed a change in décor, the substitution of tea for alcohol, the addition of music and dancers, and other modifications. Over time, these establishments gained in popularity. Even after the foreign clientele (i.e., the invaders) had departed, people continued to frequent these places. As noted by Caroline Gazaï and Geneviève Gaillet, “Cabarets were inaugurated in major hotels, along with several nightclubs (cafes), which were replicas of establishments in the West.”8Caroline Gazaï and Geneviève Gaillet, Vacances en Iran (Vacation in Iran) (Berger-Levrault, 1961), 70.

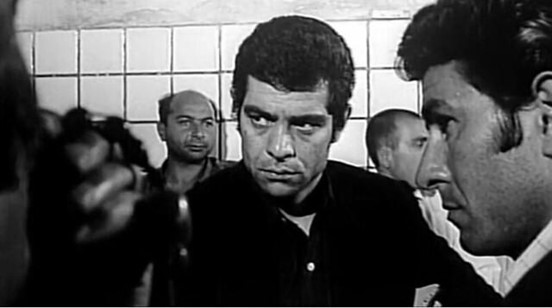

These new, distinctly masculine spaces of indulgence are strikingly similar to the saloons depicted in classic Western films. These locales where individuals imbibe alcohol, engage in gambling, attend live musical performances, procure the services of sex workers, and engage in physical altercations—all hallmarks of saloons in Western films—play almost a similar role in Iranian films. They serve alcohol, particularly vodka (known as ‛araq), accompanied by yogurt with cucumber, pickles, or fruit (mazzah). Male patrons frequent the establishment to consume alcoholic beverages, listen to music, and observe women performers engaged in a semi-nude, erotically charged dance reminiscent of the Oriental style. Other options are available, and may seem more enticing than dancing, for those who possess the appropriate funds.9A concoction of these elements can be discerned in the film Riqābat dar shahr, also called Junūb Shahr (South of the City, 1958), directed by Farrukh Ghaffārī. However, it is worth noting that the aforementioned cafés with their saloon-like atmospheres and disreputable indulgences bear no resemblance to the authentic and traditional “café” (i.e., Qahvah’khānah). Still, the term “café” in the Persian language is known to have a pejorative association, even in the present day, as it is utilized to designate a place of indulgence in alcohol and sexual pleasures.

That said, both types of cafés are present in Iranian cinema, and indeed a transition can be observed from the traditional café (Qahvah’khānah) to the alcohol-infused, carnal pleasures of the “modern” café. This transition and the typical elements associated with these two types of café have greatly influenced directors and Iranian cinema at large. For instance, the choice of location for a movie’s setting is an important element of Iranian filmmakers’ styles as it is used to convey specific narratives or themes. Thus, when depicting characters who embody traditional values, filmmakers often utilize traditional cafés and their numerous glasses of tea as a setting, symbolizing a sense of community and tradition (see Figures 8 and 12). Conversely, when portraying characters with less favorable traits, such as those who are deceitful or violent, filmmakers tend to shoot their scenes in modern cafés, symbolizing a departure from traditional values and a shift towards modern vices (see Figures Annex, A6).

Notable Examples of Qahvah’khānah in Iranian Cinema

Figure 6. Tanhā Mard-i Mahallah (The Only Man in Town, 1972) directed by Dāvūd Ismāʿīlī. Qahvah’khānah is the place where chaos begins.

Figure 7. A snapshot from Rastākhīz-i Kārgarān 24 (1978): 30, a reflection of Qahvah’khānah’s widespread popularity.

Figure 8. In a Qahvah’khānah, Qaysar (or Gheisar, from the eponymously named film, 1969), directed by Mas‛ūd Kīmiyāʾī, decides to take revenge and find his sister’s killer. One of the film’s highlights comes at the end of this sequence when Qaysar pulls on his shoes to get ready to run fast and take action.

Figure 9. Gulparī jūn (Dear Gol Pari, 1974) directed by ʿAzīzallāh Bahādurī. The Qahvah’khānah was chosen as the main location in this film.

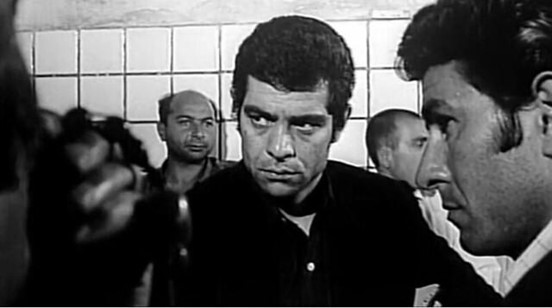

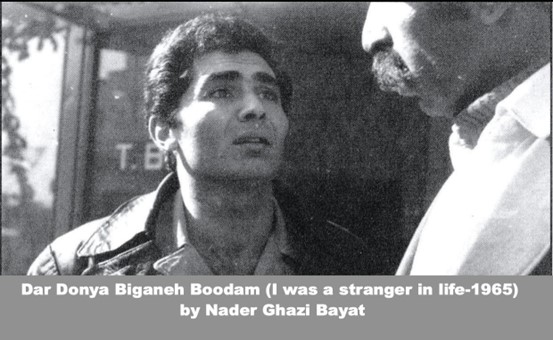

Figure 10. Dar dunyā bīgānah būdam (I Was a Stranger in Life, 1965), directed by Nādir Qāzī Bayāt. Qahvah’khānah represents a place of comfort and refuge for the character unfairly marginalized by society.

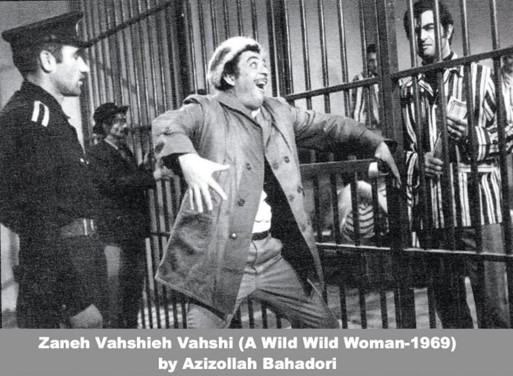

Figure 11. Zan-i vahshī-i vahshī (A Wild Wild Woman, 1969), directed by ʿAzīzallāh Bahādurī. Qahvah’khānah is a delightful family-owned establishment where the characters come together.

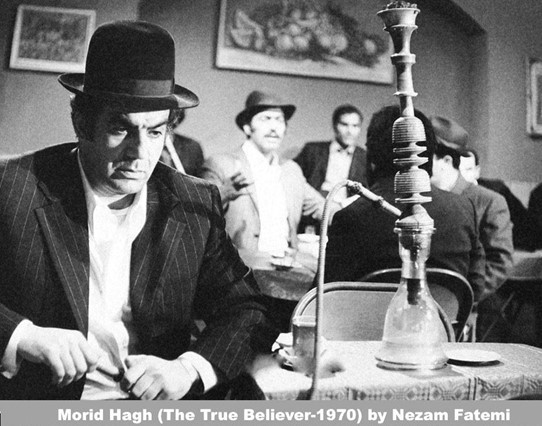

Figure 12. Murīd-i haqq (The True Believer, 1970), directed by Nizām Fātimī. Qahvah’khānah is a place where all the news, from the latest events to the most intriguing rumors, circulates throughout the town, often causing conflict and tension among the residents.

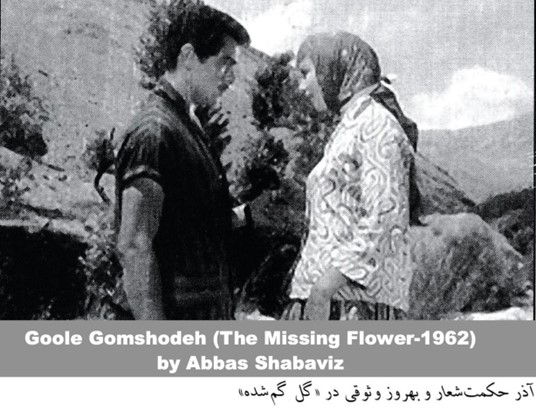

Figure 13. Gul-i gumshudah (The Missing Flower, 1962), ʿAbbās Shabāvīz. Upon the desert dunes, Qahvah’khānah stands as a meeting place for the characters.

Zūr’khānah (The House of Strength): The Traditional Place for Sports

The most remarkable and beautiful form by which the moral spirit of the Persian people was realized in life is the well-known Persian education, which entered into the soul of the person at an early age, planting in the young Persians the mentality that the good man in everyone should guide his actions, and which prepared the body and strengthened it so that he could one day be a good citizen. This education, which already existed at the time of the Medes at the court of the Persian prince (Pasargada) and was maintained by the Persians during their rule, is unique in the Orient. The Greeks were also aware of it since Herodotus. He reports that the Persians taught their sons only three things from the fifth to the twentieth year: to ride, to shoot a bow, and to speak the truth (Herod. I, 136).10Adolf Rapp, Die Religion und Sitte der Perser und übrigen Iranier nach den griechischen und römischen Quellen (The Religion and Customs of the Persians and Other Iranians According to the Greek and Roman Sources) (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, 1866), 103-104.

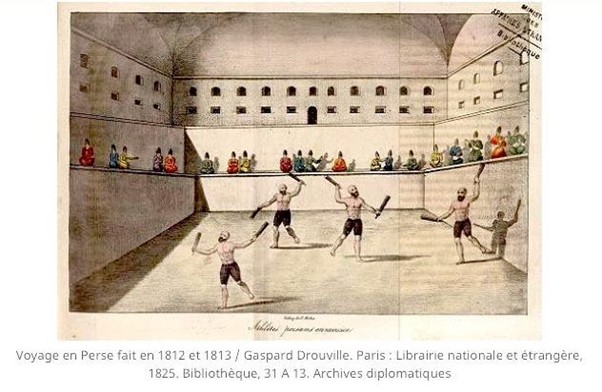

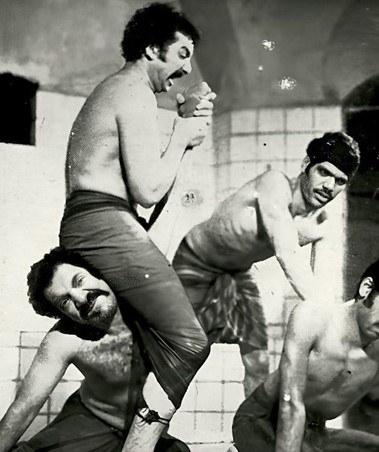

Figure 14. This captivating image offers a glimpse into the ancient tradition of Zūr’khānah in Iran, showcasing its historical significance and enduring cultural legacy.

Another location prominently featured in the films of this period is the Zūr’khānah (the House of Strength), a gymnasium for training and competing in traditional sports.11Zūr’khānah and Qahwah’khānah were incredibly popular gathering places where people and culture blended harmoniously. The Zūr’khānah shares certain traits with the café: first and foremost, it is a place for meeting and discussion. It is also where Firdawsī’s epic poems were sung (reminiscent of naqqālī in cafés) and where, in particular, the panegyric poems of Imam ʿAlī, the father of Imam Husayn, were recited. Like the café, the Zūr’khānah is therefore a space where pre-Islamic mythology and Iran’s post-Islamic religious history meet. As early as 1765, Carsten Niebuhr spoke of the “zur-xāneh” (Zūr’khānah) of Shīrāz as a place frequented by important personalities and merchants, where coffee was served, and hookah was smoked. See Goushegir, “Le café en Iran des Safavides et des Qājār à l’époque actuelle,” 72. Charles James Wills also documented the popularity of Zūr’khānah during his travels to Persia between 1866 and 1881. He wrote: “In each gymnasium (Zūr Khana, literally “house of force”) the professional “pehliwan” or wrestlers, practise daily; and gymnastics, i.e. a course of attendance at a gymnasium, are often prescribed by the native doctor. Generally, an experienced and retired pehliwan acts as “lanista,” and for a small fee prescribes a regular course of exercises. Dumb-bells are much used; also a heavy block of wood, shield-shape, some two feet by three, and three inches thick, with an aperture in the middle, in which is placed a handle. The gymnast lies on his back, and holding this in one hand makes extension from side to side; a huge bow of thick steel plates, with a chain representing the string, is bent and unbent frequently… Every great personage retains among his favoured servants a few pehliwans or wrestlers; and among the artisans many are wrestlers by profession, and follow at the same time a trade.” See Charles James Wills, In the Land of the Lion and Sun, or Modern Persia: Being Experiences of Life in Persia from 1866 to 1881 (London: Ward, Lock & Co., 1891), 98- 99. Historically, as noted in the epigraph of this section by Adolf Rapp, Iranians have always valued and participated in physical exercise as an important component of civic life since, if Rapp is to be believed, at least the time of Herodotus. Although the precise origins of this practice and the valuation of exercise in Iran remain unspecified, the purely symbolic (especially the distinctive clothing) and historical (e.g., Murshid’s poetic references) elements suggest that the Zūr’khānah tradition has been deeply embedded in Iranian culture for centuries, not merely decades (see Figure 14).12Henry Corbin mentioned a historical connection between Zūr’khānah and the Zoroastrian religion in Iran. See “Les zourhânés (interview de Henry Corbin),” YouTube, accessed January 9, 2025, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RhLDhyd_1Ws. Also Jambet writes, “Henry Corbin was often present at more or less ritualistic ceremonies such as those of Zur Khaneh, of Zoroastrian origin, in which the athletes, after a solemn kiss to the earth, performed difficult exercises and were accompanied by a reciter of poems.” See R. de Boyer Sainte Suzanne, “À Téhéran,” in Henry Corbin, ed. Christian Jambet (Paris: L’Herne, 1981), 288. According to Hossein Kohandani, Zūr’khānah is one of Iran’s most ancient sports. As he observes, “There is no valid written record of the sport of Zūr’khānah in pre-Islamic Iran, not in inscriptions, not on stones, not on the facades of historical monuments, not even on the various objects that have been discovered during archaeological excavations … However, there are indications that this sport already existed in the mentioned period, albeit for war preparation and unit conditioning.” See Hossein Kohandani, “Le zourkhâneh: Historique d’un sport traditionnel (The Zūr’khānah: The History of a Traditional Sport),” La Revue de Téhéran 9, August 2006, http://www.teheran.ir/spip.php?article509#gsc.tab=0. Goushegir notes that Zūr’khānah was highly regarded in ancient Iran and was a common meeting place for merchants and the people of the bazaar. see Goushegir, “Le café en Iran des Safavides et des Qājār à l’époque actuelle,” 72. In 1970, Roger Wood shared his experience of visiting Tehran, offering a captivating and insightful portrayal of the Zūr’khānah. He notes, “In steamy gymnasiums of Tehran, or glimpsed through basement windows in fusty provincial bazaars, the members of the Houses of Strength perform their rituals. Here is something strange and striking. Dressed only in bright knee-length trousers, a dozen large sweating men do peculiar exercises in a pit, to the beat of a drum and the chanting of epic verse. They leap. They spin. They juggle unliftable clubs. They do push-ups on the floor, and gyrate with shields and iron bows. They throw themselves grunting upon one another in wrestling contests. And when the drumbeat ends, the poetry subsides, and the last wrestlers disentangle themselves exhausted from the clinch, they resume their sober brown suits and unobtrusive ties, pick up their briefcases or their workboxes, and step outside into the ordinary world as though they have merely been having a haircut.” See Roger Wood, James Morris, and Denis Wright, Persia (New York City: Universe Books, 1970), 19.

The Zūr’khānah remains, even today, a purely male space with its own codes and secrets.13Chehabi observes this point in “The Juggernaut of Globalization: Sport and Modernization in Iran:” “What the vast majority of the national, regional, and local games and contests have in common is that they involve only men. This made physical education for women a major item on the agenda of modernizers, who faced daunting obstacles in a country whose Islamic culture mandated (albeit to various degrees in different regions) veiling and gender segregation.” See H. E. Chehabi, “The Juggernaut of Globalization: Sport and Modernization in Iran,” in Sport in Asian Society: Past and Present, ed. in J.A. Mangan and Fan Hong (London and Portland, OR: Frank Cass, 2003), 276-277. These sporty, Asian-like gymnasiums focus not only on physical training but also on spiritual development. To gain acceptance into the Zūr’khānah, one must respect all the established codes concerning honor, religion, friendship, family, and homeland.14Jaʿfar Shahrī underscores the pivotal role of Zūr’khānah’s remarkable and traditional architecture, enlightening the audience about its essential connection to the location’s core values: “The Zūr’khānah’s small door, a feature of profound cultural significance, plays a key role in fostering humility and respect. Its compact size compels athletes to lower their heads as they enter, symbolizing the importance of these virtues. This architectural design is a constant reminder for the athletes to cultivate modesty and avoid arrogance and vanity, which are detrimental to both personal growth and the communal spirit of the Zūr’khānah. This communal spirit, fostered by the shared experience of bowing their heads each time they enter, reinforces the virtues of humility and respect, foundational values in their training and discipline.” See Jaʿfar Shahrī, Tihrān-i Qadīm (Old Tehran) (Tehran: Mu‛īn, 1992), 1:165.

Pahlavānī Rituals

These traditions hold immense significance for Iranians. The individual who enters this arena and becomes its champion, or Pahlavān (literally, hero, or champion), is highly respected. For example, Ghulāmrizā Takhtī (1930-1968) is still revered as a hero and a saint, even many decades after his passing (see figure 26). As noted by Fariba Adelkhah,

Takhtī was frequently victorious in his competitions, commonly raising his head to the sky in triumph. He became a highly regarded and respected figure in the world of sports. However, it was his qualities as a hero, as a javānmard, and his simplicity that set him apart and gave him his authenticity. The qualities that distinguish a hero or sportsman from other individuals are not limited to physical attributes such as a muscular physique or a large frame. Rather, it is the individual’s ethical and human qualities that set them apart.15Fariba Adelkhah, Être moderne en Iran (Being Modern in Iran) (Karthala, 1998), 204. Concerning the concept of javānmardī, which can loosely be translated as “spiritual chivalry,” Lloyd Ridgeon notes: “Javanmardi is one of the most significant components in the identity of Persians and those who have lived and live in areas where Persianate culture has been and remains strong. This essay argues that the ethic of javanmardi demonstrates a high level of cultural continuity. The difficulty of defining this concept is partly resolved by relying on seminal texts from the medieval period and referring to important historical figures from early Iranian history. A taxonomy of types, the felon, the faithful and the fighter, are utilised in this article to provide a bricolage of characters who demonstrate that javanmardi is just as important in modern Iran as it was in medieval Persia.” See Lloyd V. Ridgeon, “The Felon, the Faithful and the Fighter: The Protean Face of the Chivalric Man (javanmard) in the Medieval Persianate and Modern Iranian Worlds,” in Javanmardi: The Ethics and Practice of Persianate Perfection, ed. L.V. Ridgeon (London: Gingko Library, 2018), 1.

To this day, he is still highly respected, to the point of becoming the subject and main character of a movie entirely devoted to him: Jahān Pahlavān Takhtī (Takhti the World Champion, 2004), directed by Bihrūz Afkhamī.

As noted by Adelkhah, Takhtī continues to be loved not only because he was physically powerful or possessed great athletic prowess, but because he also had the “ethical and human qualities” that raised him above other athletes to the status of “hero” (i.e., a pahlavān). As mentioned, these ethical qualities and the spiritual elements of the Zūr’khānah are of great significance, setting the House of Strength apart from any ordinary gym and elevating those who train and compete there. As noted by Hossein Kohandani, “The space of Zūr’khānah is reserved for the pure, the generous, the dignified, the polite, the modest, the believers, the practitioners; in short, for the irreproachable among the irreproachable.”16ee Kohandani, “Le zourkhâneh: Historique d’un sport traditionnel.”

All of these important qualities are recalled and repeated by the Murshid (literally, director, master, or guide) during the physical exercises. As in the café, a Naqqāl (also called a Murshid) recites and sings the words of the poets or prophets. As Kohandani notes, “The ‘Morched’ sings old poems out loud and encourages the athletes during the entire session. The athlete must ask permission from the elders before the Morched allows him to begin performing in the center of the track.”17See Kohandani, “Le zourkhâneh: Historique d’un sport traditionnel.” Jaʿfar Shahrī also underscores the esteemed status of the pahlavāns and the profound faith people have in their spiritual and physical strength. He writes, “The pahlavāns, held in such high regard, are often asked to pray for the recovery of sick relatives, a testament to people’s faith in their spiritual and physical strength. In a unique twist, some even seek the Murshid’s assistance in obtaining the pahlavāns’ sweat, believing it possesses healing properties.” See Shahrī, Tihrān-i Qadīm, 170. Shahrī also observes: “They also organized a ceremony called Gulrīzān (falling flowers), where they invited neighbors, particularly the wealthiest members of the community, to contribute. This event aimed to gather support for people facing various difficulties, such as illness, financial hardships, or the needs of orphans. Being invited to a Gulrīzān was a significant honor for the affluent merchants, who would strive to demonstrate their generosity and social standing by making substantial donations. This practice provided essential aid to those in need and reinforced the communal bonds and the values of charity and solidarity, fostering a sense of unity within the society.” See Shahrī, Tihrān-i qadīm, 179.

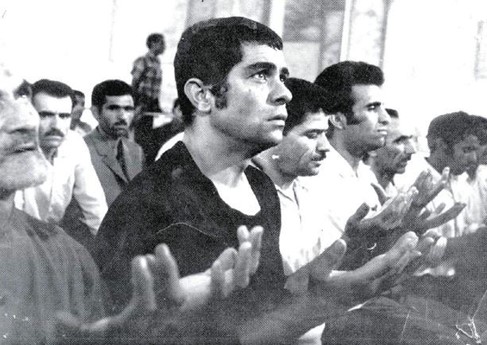

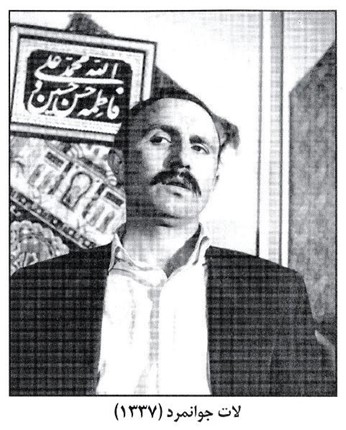

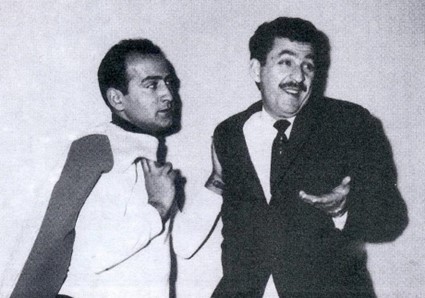

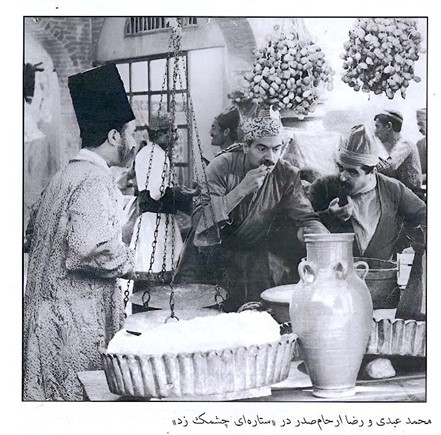

Once or twice a week, the men gather at the Zūr’khānah to practice their sports and listen to the Murshid’s recitals. Of course, as in all meeting places, there is always a highly respected champion (Pahlavān) who is held in high esteem both in the Zūr’khānah and the neighborhood or even the entire city. Its importance has been compared to the ‘Lattes’18“Luti [i.e., Latte] leaders were generally self-interested individuals looking to enhance their personal esteem, as well as gain the patronage of powerful political and religious leaders… they were often regarded as free spirits who were sometimes the local strongmen (wrestlers and weightlifters associated with local gymnasiums (i.e., ‘Zūr’khānah’), self-selected to protect the weak and uphold community morality.” See Stephan C. Poulson, Social Movements in Twentieth-Century Iran: Culture, Ideology and Mobilising Frameworks (Lexington Books, 2005), 84. It is important to note that the roles played by the “Lattes” and their politico-religious commitments also have dark and negative sides, much like those of the American “mobs.” For example, as Poulson writes, “… ethnic groups, mobilized by “mob” leaders in major American cities raised crowds quickly and engaged in some of the same behaviors that the Luti [i.e., Latte] leaders did in Iranian cities…” (the coup against Iran’s popular prime minister, Muhammad Musaddiq in 1953). See Poulson, Social Movements in Twentieth-Century Iran, 88. This was one of the reasons that Majīd Muhsinī, the director of Lāt-i Javānmard (The Noble Rogue, 1958), regretted the title of his film. He later told his son, “I should have just called it ‘Javānmard’ (chivalrous youth) and removed the word ‘latte.’ Lāt-i Javānmard was not an appropriate title.” See Farīd Muhsinī’s interview published in Sīnimā-yi Īrān, rūzigār-i naw (Iranian Cinema, The New Era), ed. Saʿīd Mustaghāsī (Tehran: Alast-i Fardā, 2002), 112. There were several reasons for using this character (e.g., jāhil, lūtī, lāt) in Iranian cinema of that period. Some critics think that the most important reason was censorship, which greatly influenced the choice of the characters. For example, as Amān Mantiqī remarks, “The only professions without any syndicate are those of the jāhil (literally, ignorant, or ill-mannered) and the prostitute. They have nobody to protect them. That is why the majority of Iranian pictures are about them.” See Amān Mantiqī, “Mīz-i gird-i sīnima-yi Īrān (Round Table on Iranian Cinema),” Farhang va Zindagī 18 (1976): 81. as they are often the same people that come to the sports “Mecca” (Zūr’khānah). The master stands at the top, and his disciples gather in a circle, then take their place in the middle to wrestle. Of course, that emblematic location (Zūr’khānah) plays a positive role in Iranian cinema so that whenever the camera is in that place, we know in advance that we are dealing with positive, respected, and respectable characters.19In Gharīb (Stranger, 1973), directed by Ghulām Rizā Sarkūb, the film opens in a Zūr’khānah. The Murshid’s song fills the air as men engage in physical exercises, while two young brothers are watching all this with joy. It is a happy scene before the drama unfolds. In the same film, the camera takes us to another type of house, also coveted in Iranian cinema: the “brothel.” I will discuss this highly coveted location, as well as the bazaar and prison, in a forthcoming article. This symbol is used not only in cinema but also in literature (e.g., by the author Sādiq Hidāyat) and theater (e.g., by the playwright and famous filmmaker Bahrām Bayzāʾī). It has even been used by those in power, including the Shah himself. Nonetheless, the excessive use of the Zūr’khānah by the political elite has undeniably had a negative impact.20The Pahlavānī tradition, a pillar of Persian culture, was deeply affected when the Shah, in a controversial move, placed Shaʿbān Jaʿfarī, also known as the ‘Brainless,’ at the helm of the Pahlavānī Federation. As noted by Philippe Rochard and Denis Jallat, “Shaʿban Jaʿfari remained a despised symbol of the close relationship between the zurkhaneh and the former regime.” See Philippe Rochard and Denis Jallat, “Zurkhaneh, Sufism, Fotovvat/Javanmardi and Modernity: Considerations about Historical Interpretations of a Traditional Athletic Institution,” in Javanmardi: The Ethics and Practice of Persianate Perfection, ed. Lloyd Ridgeon (London: Gingko Library, 2018), 235. Numerous well-known Iranian actors of that era emerged from Zūr’khānah. The foremost among them was Muhammad ʿAlī Fardīn, Iran’s most celebrated actor. He exuded good looks, stature, kindness, generosity, and honesty, embodying exactly what audiences anticipated from a pahlavān.

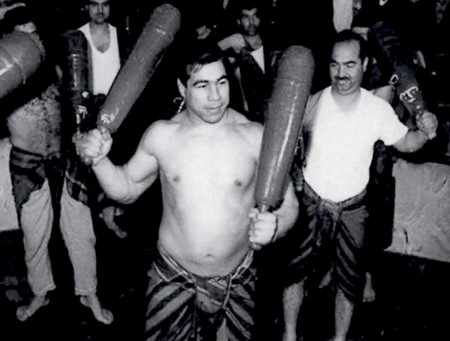

Notable Examples of Zūr’khānah in Iranian Cinema

Here are some exceptional examples that showcase the influence of the Zūr’khānah in pre-revolutionary Iranian Cinema (see Figures 15 to 26):

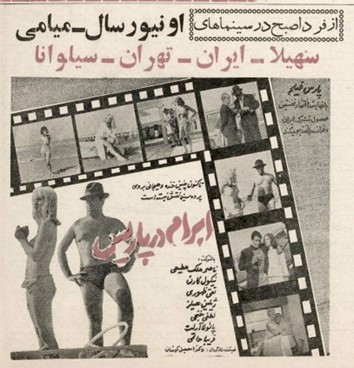

Figure 15. Abrām dar Pārīs (Abraham in Paris, 1964) directed by Ismāʿīl Kūshān. The film opens with scenes of a Zūr’khānah, where the Murshid sings and athletes exercise, including the main character, Abrām, played by Nāsir Malik-Mutīʿī. Through this opening, the director portrays his character, Abram, as a positive and righteous man.

Figure 16. Kūchah-yi Mardhā (Alley of Valiants, 1970), directed by Saʿīd Mutallibī, tells the story of ʿAlī, who seeks solace in a Zūr’khānah after feeling heartbroken and being far from his best friend. In the Zūr’khānah, he finds comfort and is able to regain strength.

Figure 17. Pahlavān Mufrad (The Hero Mufrad, 1971), directed by Amān Mantiqī. The movie centers around Zūr’khānah and its characters. Pahlavān Mufrad (played by Nāsir Malik-Mutīʿī) is a highly esteemed trainer in a Zūr’khānah. The codes of honor and javānmardī that are promoted in the Zūr’khānah are the main themes of this movie.

Figure 18. Jahān Pahlavān (The World Champion, 1966), directed by Ismāʿīl Riyāhī). The movie is focused on the javānmard attitude of the hero of the movie, Akbar Jahān Pahlavān (played by Muhammad ʿAlī Fardīn).

Figure 19. Qaysar (Gheisar, 1969), directed by Masʿūd Kīmiyāʾī. Isfandiyār Munfarid-zādah composed the soundtrack of Qaysar, which was inspired by the Murshid’s Zarb-i Zūr’khānah (Drum of the Zūr’khānah).

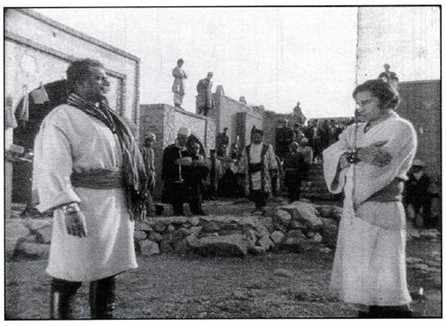

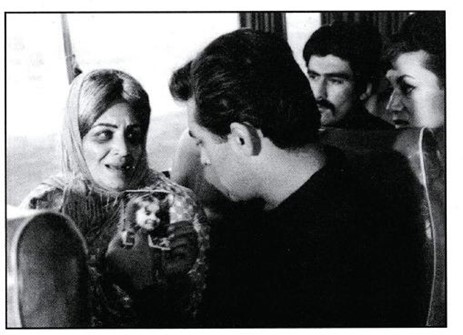

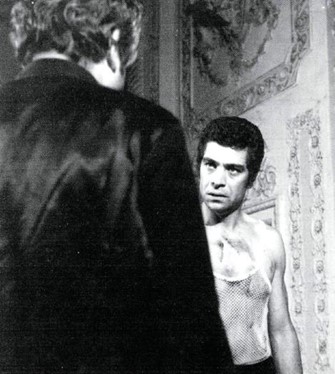

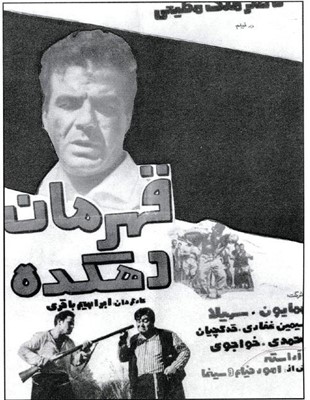

Figure 20. Qahramān-i Dihkadah (The Champion of the Village,1966), directed by Ibrāhīm Bāqirī. A pahlavān comes to save the village.

Figure 21. Gharīb (Stranger, 1973), directed by Ghulām Rizā Sarkūb. The film boldly opens at a Zūr’khānah, a symbolically important location for the protagonist, the sole individual prepared to combat injustices.

Figure 22. Mardān-i Sahar (Men of the Dawn, 1971), directed by Ismāʿīl Nūrīʿallā. In each Zūr’khānah, a greatly esteemed master (pahlavān) resides. He commands not just respect but deep reverence from the neighborhood. However, when love enters the picture, the town’s two most renowned pahlavāns compete fiercely for the beloved’s affection. The dramatic final fight of this timeless tale of love’s triangle unfolds within the distinctive setting of Zūr’khānah.

Figure 23. Jāhil va Raqqāsah (The Thug and the Dancer, 1976), directed by Rizā Safāyī. Faithful to the principles and traditions of Pahlavānī and Zūrkhānah, upholding their rules and values.

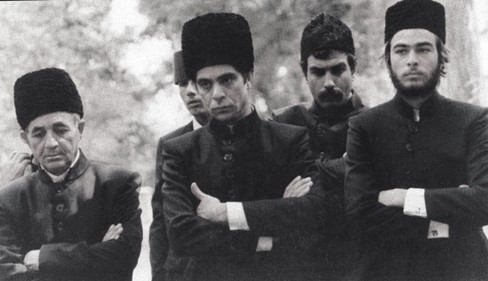

Figure 24. Qalandar (1972), directed by ʿAlī Hātamī. Pahlavānī and Zūr’khānah rituals are once again highlighted in this movie, emphasizing their cultural and spiritual significance.

Figure 25. Hasan Kachal (Hasan the Bald, 1970), directed by ʿAlī Hātamī. Everyone wants to be a Pahlavān.

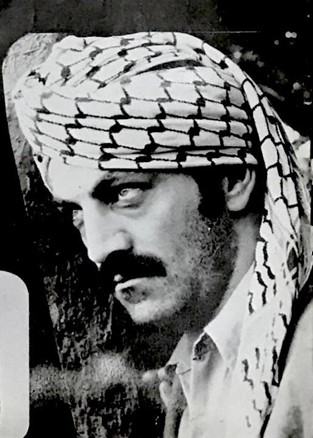

Figure 26. The one who enters this place and becomes its champion achieves immortality, exemplified by Ghulāmrizā Takhtī. Even decades after his passing, he remains a revered hero and saint, his legacy enduring through the passage of time.

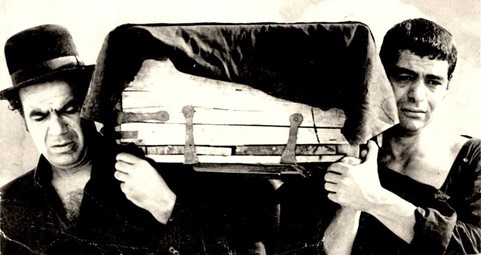

Hammām (Bathhouses): Communal Bathing and Socializing

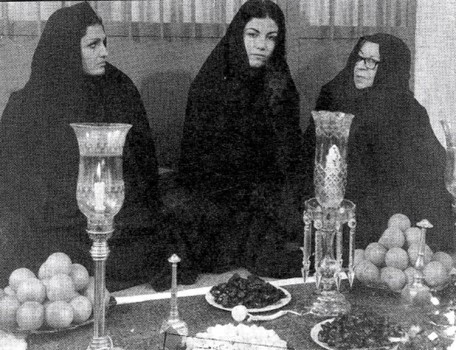

Hammāms, or bathhouses, are places for communal bathing and socializing. While hammāms are intended for both men and women, representations of women in Iranian and Arab cinema and art are rare compared to their Western counterparts. In Western art, painters such as Dominique Ingres and Jean-Léon Gérôme freely depicted women in hammāms,21Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres painted The Turkish Bath (Le Bain turc) between 1852 and 1859, and Jean-Léon Gérôme painted The Moorish Bath (Le Bain turc) in 1870. Both depict scenes inspired by hammāms. while in Iranian cinema, women’s spaces remain largely unexplored. Conversely, male sections of the baths, including nudity, are often captured on camera; but again, women’s areas are rarely featured. Indeed, in Iranian cinema, the portrayal of the women’s hammām is a mysterious and seldom explored subject, with only a few glimpses presented in fleeting moments.22This rare use of women’s hammāms and the restrictions around depicting them with accuracy lead to some strange filmic choices. For example, in Guzar-i Akbar (The Passage of Akbar, 1972), directed by Muhammad ʿAlī Zarandī, there is a sequence in which a group of women sit in the foyer of a hammām. Strangely enough, they are covered with towels, and we can only see their heads.

Despite the gender imbalances in filmmakers’ depiction, the hammām serves as a crucial gathering place, much like the Qahvah’khānah, bringing people together for conversation and interaction. Men gather here to bathe and socialize, while women have their own separate space. They drink tea and smoke, often in the dressing rooms, and discuss a wide range of topics, from national and international politics to the current market price of onions. In addition, the hammāms are bustling hubs for various business activities such as marriages, sponsorships, rentals, sales, and purchases.23As Gaspard Drouville recounts in his Journey to Persia during the early 1800s, the hammāms functioned as important location for the middle classes to mingle with traders from other lands, mixing business with relaxation. He notes how, even then “The public baths (hammāms) still serve as a meeting place for the middle class. Foreigners and merchants also gather there. They come to make acquaintances or talk business. Everyone smokes a pipe or a caillian, drinks coffee, and spends a few hours each day. During this time, they make or learn some news that they take with them elsewhere.” See Gaspard Drouville, Voyage en Perse, pendent les années 1812 et 1813 (Journey to Persia in 1812 and 1813) (Paris: Masson et Yonet, 1828), 1:83. Drouville further elaborates on the historical value of the hammāms for women in particular: “But it’s the women, above all, who use these places as a meeting place. They visit each other; each niche has its own society, and it’s always full. It is here that they deal with everything that concerns the affairs of their families, and since there are few among them who do not have some cause for jealousy and, consequently, for complaint, it can be said that this place is a women’s court, presided over by the old women, who decide in the last resort on all offenses within their jurisdiction… After exhausting this subject and consoling each other for their disgrace, they inquire about planned marriages, which provides an opportunity for a rigorous investigation of the unfortunate fiancées.” Gaspard Drouville, Voyage en Perse, 1:83-84. Interestingly, although women are not often depicted in films, in reality, they frequent the hammāms far more than men. Furthermore, there are occasions when the hammāms are exclusively reserved for women, sometimes for an entire day, creating a unique and vibrant atmosphere. The Feast of Hannah is one such occasion during which this occurs. As Hamīd Shuʿāʿī writes, “One of the most important celebrations for women was the feast of Hannah. It began after the months of Muharram and Safar, and since women did not often leave home during these religious months, they would all gather at the hammām afterward. To make Hannah more colorful, they would spend all day and would have lunch.”24Shuʿāʿī, Sadā-yi pā…, 34-35. It is worth noting, as observed in the writing of C. J. Wills in the mid to late nineteenth century, that not everyone frequented the baths, especially if they had their own at home. His observations on the minutiae of bathing practices are also of great interest, emphasizing the communal or collective nature of the experience and the best practices of that time. Wills observes: “As for the wealthier, they have baths in their own houses, and use them almost daily. The middle classes make parties to go to the hammam, and assist each other in the various processes of shampooing, washing with the “keesa,” or rough glove, and washing the hair with pipe-clay of Shiraz—a plan, by the way, which it is worthwhile to follow, for the hair is rendered thereby cleaner than when eggs are used. The pipe-clay is made up in little round cakes much resembling biscuits.” See Wills, In the Land of the Lion and Sun, 98- 99.

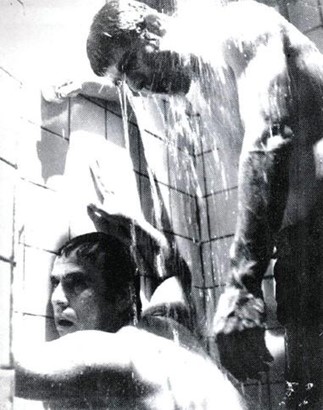

The bathhouse has been featured in numerous movies (figures 27 to 30), increasing cinema’s popularity and creating a captivating atmosphere on the screen. One of the most notable examples is Qaysar (1969), directed by Masʿūd Kīmiyāʾī, in which the murder scene in the hammām became so iconic that it was replicated in other movies (see Figure 30). This interest comes from the fact that the hammām, like other popular locations (e.g., Qahvah’khānah and Zūr’khānah), has always been full of stories and secrets. Towns and villages in Iran are often surrounded by walls as long and wide as those of a fortified castle. Public spaces are rare, and there are stories—or, more accurately, secrets—behind every wall. In this very discreet and closed society, for a moment amid the steam and conviviality of the baths, it is possible to cross human borders, to communicate, to speak and to be heard.

Importantly, the public baths in Iran are not merely physical spaces, but social equalizers. They are the places where all strata of society converge, where stories are shared and connections are forged. Filmmakers, recognizing the universal appeal of these spaces, often set their stories and characters in popular and underprivileged neighborhoods, using the familiarity of the public baths to reach wider audiences. C. J. Wills, for instance, notes the broad and economically balancing, if not entirely equalizing, appeal of the baths due to their affordability. Wills states: “These public baths are open free of charge and without distinction to rich and poor. A few coppers are given to the ‘delaks,’ or bath attendants, male and female. These pay for fuel, hot water, etc.… The whole bath can be always exclusively hired for a few kerans (shillings).”25See Wills, In the Land of the Lion and Sun, 334.

That said, in much the same way as the Naqqāls were pushed out by the advent of television and cinema, with the arrival of modernity and the inclusion of bathrooms in every home, the significance of the public hammām has diminished. As a result, many hammāms have closed down. Nevertheless, even in the face of financial constraints, residents of the southern working districts of Tehran or other cities (figure 27), have continued to maintain their hammāms, and some are still operational today.

Notable Examples of Hammām in Iranian Cinema

Figures 27 to 34 include specific examples of the influence of the hammām as an ideal setting and film location in the cinema of pre-revolutionary Iran.

Figure 27. Hammām-i Bāzār-i Qom is one of the oldest and most rare hammāms still used today. Photo Vali Givehchi. 2023.

Figure 28. Janūbī (Southern, 1973), directed by Muhammad Rizā Fazīlī.

Figure 29. Janūbī (Southern, 1973), directed by Muhammad Rizā Fazīlī. Figures 28 and 29 present rare and captivating stills from the film, offering a glimpse into the intriguing world of a women’s hammām. They highlight the timeless rituals, distinctive architecture, and serene ambiance of this culturally rich space.

Figure 30. Qaysar (1969) directed by Masʿūd Kīmiyāʾī. The murder scene at the hammām became so iconic that it was replicated in several movies.

Figure 31. In Shādī’hā-yi Zindagī-i Mā (Our Joys of Life, 1976), directed by Mahmūd Kūshān, a gripping encounter unfolds as a policeman comes face to face with a determined stalker he has been tirelessly searching for over the course of several months. This suspenseful encounter takes place in a hammām, adding an additional layer of intrigue to the story.

Figure 32. Khurshīd Mīdarakhshad (The Sun is Shining, 1956), directed by Sardār Sākir. The first character in the movie changes his identity by stealing clothes from a dressing room in a hammām.

Figure 33. Jāhil va Raqqāsah (The Thug and the Dancer, 1976), directed by Rizā Safāyī. Whether it is discussing sports, news, or personal experiences, this space offers a comfortable environment for relaxation and camaraderie.

Figure 34. Pakhmah (The Dullard, 1972), directed by Māziyār Partaw. The captivating performances at this location have caught the attention of a broader and more diverse audience, bringing together people from various backgrounds and interests.

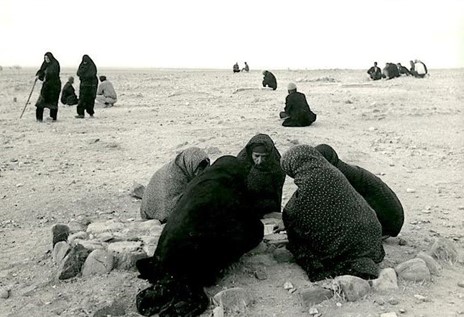

Ziyārat’gāh (Places of Worship, Mosques): Religious, Spiritual, and Political Significance

In addition to specific cinematic settings, Iranian culture is also characterized by a strong association with Ziyārat’gāh, a term referring to various religious sites and places of worship, including mosques (masjids).26“In Shiʿism, another category of pilgrimage is designated as ‘ziarat.’ These practices involve a pilgrimage, or ‘visiting,’ to the gravesites of revered Islamic figures.” See Dejan Bogdanovic and Jean-Louis Bacqué-Grammont, Iran, les sept climats (Iran, The Seven Climates) (Orientalistes de France, 1972), 37. “The term masjid (pl. masājid), which is translated as ‘mosque,’ is derived from the root sajada, which means ‘to prostrate oneself,’… As a result, it primarily denotes the location where the faithful prostrate themselves during ritual prayers.” Ismaël Kadaré et al., Dictionnaire de l’islam: Religion et civilisation (Dictionary of Islam: Religion and Civilization) (Paris: Encyclopaedia Universalis – Albin Michel, 1997), 598. As observed by Louis Massignon, the mosque itself is architecturally oriented toward Mecca. Massignon describes, for instance, how “the faithful, arranged in parallel rows, must maintain their gaze fixed on a single point during prayer, namely the axial niche, or ‘qibla,’ which marks the direction of Mecca, the site of the annual propitiatory sacrifice to the God of Abraham. In contrast to the bell tower, the minaret, where the human voice itself emerges, replaces the inanimate bronze, for the daily call to prayer.” See Louis Massignon, En Islam, jardins et mosquées (In Islam, Gardens and Mosques) (Paris: Le Nouveau Commerce, 1981), 12-13. Rather than, though not always, particular locations for filming, these sites have served more as backdrops for Iranian cinema writ large and have become inextricably intertwined with the nation’s film industry. Such locations are renowned for their status as places of meditation and prayer where devotees engage in various religious practices, and they are particularly prevalent in Muslim-majority countries with significant Shi’ite communities.

The grandeur of these locations, their magnificent architectural structures, and their historical significance were not just a product of their time but were further enhanced during the rule of Persian monarchs. The contributions of Shah ʿAbbās and Fath-ʿAlī Shah in particular have left an indelible mark on Iran’s religious and cultural landscape. As noted by Yann Richard, “He [Fath-Ali Shah] reinforced the religious character of his kingdom. Furthermore, he commissioned the construction of numerous mosques and embellished the domes of tombs belonging to Shiite Imams and saints in Qom and Mashhad.”27Yann Richard, L’Iran de 1800 à nos jours (Iran from 1800 to the Present Day) (Paris: Flammarion, 2009), 43.

Figure 35. The sanctuary in Qom is notable for containing the tomb of a woman, Fātimah al-Maʿsūmah, sister of Imām Rizā. Photo: Aghdas Baghaei, 2024.

The Imāmzādahs (or, Imamzadehs),28Geneviève Gobillot helpfully defines what is meant by this term (i.e., Imamzadeh): “The term Imāmzādah, used to refer to both the descendant of a Shiʿite Imām and their tomb . . . It seems plausible to suggest that the first Imāmzādahgān settled in Persia around the time of the caliph al-Maʾmūn (m. 833). The rituals of these pilgrimages are similar to those of Mecca, with processions around the tomb in a counterclockwise direction. Pilgrims touch and kiss the flesh and recite litanies specific to each Imāmzādah . . . A visit to the tomb of one of the Imāms is considered to be of equal significance to a visit to the Prophet’s tomb in Medina.” See Geneviève Gobillot, Les Chiites, fils d’Abraham (The Shiites, Sons of Abraham) (Brepols, 1998), 140. as well as the mausoleums and great mosques associated with them, are worthy of mention. The most frequently visited of the latter are Imam Rizā in Mashhad and Maʿsūmah in Qom.29Religious pilgrimages and other forms of frequenting religious sites are a long-standing and diverse custom in Iran. Offering some examples of these, Joanna De Groot describes the importance of connections between “locality” and “shared rituals” in Shi’a faith. She writes, “The custom of visiting shrines associated with Imams, their relatives, or other holy persons, included weekly visits by groups of women to local imamzadehs (shrines) and long-distance journeys to major shrines like those at Mashad [sic] and Karbala. Local shrines were the focus for ceremonials celebrated by particular communities or occupational groups. Linking attachments to locality or occupation with affirmations of Shi’a commitment, and creating shared rituals, they were established and regular popular religious activities.” See Joanna De Groot, Religion, Culture and Politics in Iran: From the Qajars to Khomeini (I. B. Tauris, 2007), 26. Further, De Groot also observes and provides evidence of ongoing “expressions of personal and communal commitment and identity” of Shiʿa faith in Iran and the popularity of Mashhad and Qom as sites of pilgrimage. De Groot writes: “Among industrial workers surveyed in 1970s, those who were able to take holidays used them predominantly for pilgrimage trips to Mashad and Qum. Bazaris and the newly migrated slum and shanty dwellers of Tehran participated in the rituals of Muharram and Ramadan. Families attended mosques, hay’ats and huseiniyehs to undertake religious duties while making sociable and communal contacts. This evidence of persistent cultural energy in the established practices of Shi’a Iranians indicates continued support for such expressions of personal and communal commitment and identity.” See De Groot, Religion, Culture and Politics in Iran, 57. The pilgrimage to Mashhad is a profoundly significant tradition for Iranians, underlined by an account (hadīs) from Prophet Muhammad himself: “It was remembered that Mahomet had said: ‘A part of my body is to be buried in Khorosan, and whoever goes there on pilgrimage Allah will surely destine to paradise, and his body will be haram, forbidden, to the flames of Hell: and whoever goes there with sorrow, Allah will take his sorrow away.’” See Robert Payne, Journey to Persia (New York: E.p. Dutton & CO., INC., 1952), 181. Qom is a remarkable pilgrimage destination known for a tomb dedicated to a woman, which adds a unique and distinctive element to the site. “The sanctuary in Qom is notable for containing the tomb of a woman, Fātimah al-Maʿsūmah, sister of Imām Rizā… In 816 CE, this revered woman, on her way to visit her brother, fell ill in Sāvah. She was subsequently taken to Qom, where she died and was buried.” See Bogdanovic and Bacqué-Grammont, Iran, les sept climats, 37-38. Other noteworthy examples include the smaller places of worship located in the districts designated Saqqā’khānah (literally, the house of the fountain) and Shamʿ’khānah) (literally, the house of candles). Mohammad Ali Amir-Moezzi offers a vivid description of such sites by drawing on the impression of foreign visitors such as Chardin: “Western travelers, such as Chevalier Chardin, who visited Isfahan in 1665, described Qom, where they made a stop, as a flourishing market surrounded by a verdant oasis with intricate gold and silver decorations, fine wool and silk carpets, and continuous chanting of the Koran throughout the night and day.”30Mohammad Ali Amir-Moezzi, Lieux d’Islam, cultes et cultures de l’Afrique à Java (Places of Islam, Cults and Cultures from Africa to Java) (Autrement, 1996), 61. Amir-Moezzi’s depiction of Chardin’s impression highlights how such sites’ rich and immersive quality has left a lasting impact in Iran for centuries.

These religious cities in Iran, beyond their religious connotations, have also importantly played a pivotal role in shaping Iran’s socio-political landscape. They are not just places of worship, but also the foundation for vital elements of Iran’s socio-political movements. Joanna De Groot underlines this in her summary of several religiously inflected events which occurred in the year before the 1979 Revolution. She writes, for instance, how “The January 1978 confrontation of the Qum tullab [religious students] with the regime as they protested the attack on Khomeini in the establishment press segued into ‘mourning’ protests in other centres which in turn led to demonstrations fuelled by news of violence . . . Marches and shootings in Tehran in early September fuelled the spread of strikes and street protests.”31See De Groot, Religion, Culture and Politics in Iran, 243. These sites and, indeed, cities possess and represent both deep religious meaning as much as they represent and possess deep political import. Thus, it is not surprising that they should equally and deeply influence Iranian cinema.

Notable Ziyārat’gāhs in Iranian Cinema

In the vast majority of Iranian films, regardless of the specific narrative context, one can consistently observe the inclusion of places of worship in pivotal sequences where characters often make significant references to them. This cinematic motif is employed with such frequency that it ultimately becomes the hallmark of Iranian cinema, particularly within the context of Fīlm-Fārsī.

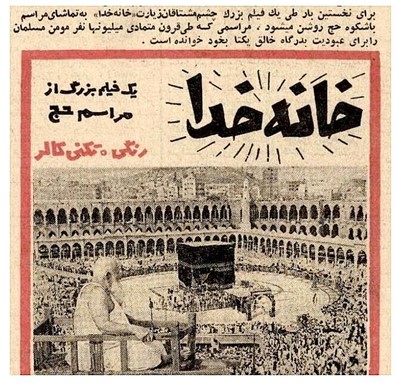

Some critics trace early cinematic representations of religion to Qaysar. Others consider Majīd Muhsinī’s Lāt-i Javānmard (The Noble Rogue, 1958) a relevant example of depicting the important religious location of Mecca. The Noble Rogue (figure 42) tells the story of a father’s journey to Mecca and his duty to leave his daughter in the care of a local nobleman. Undoubtedly, The Noble Rogue holds significant ground in this context. However, Qaysar truly stands as a historical milestone, establishing religious representations as a prominent and significant aspect, both visually and orally. The film’s narrative is enriched by numerous illustrations of the Imams, their tombs, and dialogue that references them. In Qaysar, religion and its places of worship are not mere pretexts, but integral narrative elements reinforced by their visual presence.32Images such as the prayer scene of Khān Dā’ī’s wife at the beginning of the movie and photos of the prophets in various scenes are shown during the movie. In another scene, Qaysar speaks with reverence about his brother Farmān, recalling, “He undertook Imam Rizā’s pilgrimage, a sacred journey of seeking forgiveness and finding righteousness. During the holy month of Ramadan, we would venture onto the streets with my brother (Farmān), who would selflessly spend all his savings on food for the less fortunate.” He concludes, “I have only two things left to do: Take Nān-i Mashadī on pilgrimage to Mashhad (the holy city) …” Qaysar, directed by Mas‛ūd Kīmiyā’ī (1969), 00:46:00.

Subsequently, other filmmakers extended this approach even further by incorporating mosques and other such places into their films. In Rafīq (Friend, 1975), directed by Īraj Qādirī, for example, the film opens with an impressive image of the Great Mosque of Mashhad. At the film’s outset, we witness two friends, Rizā and Zabīh, arriving at the Mosque of Mashhad where they intend to request pardon before the tomb of the revered Imam Rizā.33Regarding the significance of the pilgrimage to Mashhad in Iranian Shiʿa culture, Richard states: “The eighth Imam, Rizā, is a prominent figure in Shiʿism, particularly venerated in Iran where he is interred in a mausoleum. The shrine of Imam Rizā, since the 14th century, has been a focal point for Shiʿite piety. This was largely due to the conversion of the Mongol ruler (Uljāytū) to this branch of Islam, a pivotal event in the shrine’s history. From the 16th century onwards, pilgrimage to this site represented an alternative to the pilgrimage to Mecca or Najaf and Karbala, which were in enemy Sunni territory.” See Yann Richard, L’Islam Chi’ite (Shiʿite Islam) (Paris: Fayard, 1991), 56-58. Notably, the protagonist in this film shares the same first name as the positive character, “Rizā.” The film features numerous scenes of different mausoleums or places of worship (e.g., Saqqā’khānah), with particular emphasis on the courtyard of a mosque at the film’s conclusion. One particular scene depicts the death of Zabīh, a friend of the protagonist, who is stabbed in the stomach and dies in the courtyard of the Mosque.

In Tawqī (Wood Pigeon, 1976), directed by ʿAlī Hātamī, one of the film’s characters (Sayyid Murtazā) enters a mosque and subsequently conceals himself among worshippers engaged in prayer (see Figure 36). First and foremost, the Mosque represents a refuge for him, as it holds a certain reverence and respect among the local population. As a result, the Mosque’s importance serves as a deterrent to potential assailants, dissuading them from causing harm. Later in the film, Sayyid Murtazā takes refuge in an Imāmzādah. As a matter of protocol, the assailants must wait for him to emerge; they cannot act until he has departed. Respecting this rule is essential, even for those with negative characteristics. Failure to do so leads to being seen as malevolent and deserving punishment.

Similarly, in Mihmān (Guest, 1976) directed by Kāmrān Qadakchiyān, a man delegates the care of his daughter to the film’s protagonist, ʿInāyatallāh, for the purpose of undertaking a pilgrimage to Mecca. And in Mard (Man, 1972), directed by Farīdūn Zhūrak, the transformative power of a sacred site is vividly portrayed. One of the film’s characters, an alcoholic, is locked in an Imāmzādah by his companion in a desperate attempt to curb his addiction. Despite enduring numerous hardships, this character’s unwavering belief in the sanctity of the place is a testament to the profound influence of these sites. After a brief period of abstinence, he successfully overcomes his addiction.

The cultural significance of the narrative and its characters, particularly those from urban or impoverished areas, is deeply intertwined with the visibility of the locales in question. This connection is not coincidental. The attachment of these neighborhoods and cities to specific locales is a palpable phenomenon. It would be a challenge to find a neighborhood downtown (bazaar) without a mosque, an Imāmzādah, or a Saqqā’khānah, underscoring the cultural fabric of these areas. Groot highlighted the bazaar’s prime location in the city center, right alongside the bustling mosque, emphasizing the convenience for the mass population.

In nineteenth-century Iranian towns, religion was physically present at the very centre of urban life. That centre was the bazar, where most manufacturing and commerce took place. It was the location not only for workshops, business premises, warehouses and shops, but also for places of worship (mosques and shrines) and other places for religious gatherings (tekkiehs, huseiniyehs), or centres for education (colleges, schools), which were under mainly religious control… This proximity of workshop and mosque, of commercial premises and religious buildings was not just picturesque or coincidental, but expressed significant personal and institutional connections between those involved in manufacturing or trade and religious specialists.34De Groot, Religion, Culture and Politics in Iran, 63-64.

Including sacred sites in portraying these neighborhoods and their characters is a matter of cultural authenticity and a narrative necessity. Filmmakers who neglect these sites risk compromising the integrity of their narratives and potentially alienating their audience. The presence of these sites is thus not only a backdrop but a crucial element that enriches the narrative and enhances the audience’s engagement. However, this raises questions about the balance between aesthetic choices and narrative coherence, as the way filmmakers present these revered locations does not always align with their stories or make logical sense.

The presentation of religious elements in a movie sometimes turns out to be highly inappropriate, the pretext of presenting a mosque at the end of the movie sometimes becomes an easy way to end the story. For example, in a trendy movie called Raqqāsah-ʼi Shahr (The City Dancer, 1970) directed by Shāpūr Qarīb, the main character, Ghulām, who is married and has several children, falls in love with a dancer named Parī and decides to leave everything for her. However, at the end of the movie, after listening to his father’s advice, he comes to his senses and decides to get rid of Parī. In the movie’s final sequence, he is happy to be reunited with his family, with whom he pilgrimages to the tomb of Imam Rizā. These cobbled-together, happily-ever-after endings are frequently accompanied by a pilgrim’s journey such as the one undertaken by Ghulām to bring the “wicked” characters back to the straight and narrow path. No matter how slap-dash their presentation may be, the right elements—such as establishing or background views of the mosque, which becomes more and more visible as time goes by—have to be found within the world of the film to win over the audience. From 1970 to 1979, this element appeared in almost all of the films made during these years. For example, in one of Īraj Qādirī’s movies, Barādar-kushī (Fratricide, 1978), the mosque is an integral part of the plot.35t is notable that this movie was prohibited for more than thirty years and was only screened in 2011.

In addition to their pervasive presence, these sacred places also serve as emotional landmarks. When a film’s main character can no longer find solace in the chaos of the world, they often seek refuge in a mosque. In these places, the characters frequently pour out their hearts to God or to themselves, expressing their deepest fears and desires. In so doing, these scenes humanize these solitary, complex characters, making them more relatable and endearing to the viewer. Characters who, in the outside world, previously seemed invincible, come to appear vulnerable once inside the mosque, lost in the vastness of the building’s architecture. For example, in Nuqrah-Dāgh (The Burning Diamond, 1971) directed by Īraj Qādirī, one character’s (Tāhir) ability to regain their composure in the presence of a ‘Saqqā’khānah and by drinking holy water from its well is significant. This brief scene immediately introduces one of the film’s protagonists as a morally upright individual, sparking intrigue about his character development.

In another film, Ustā Karīm Nawkaratīm (God, We Are at Your Mercy, 1974) directed by Mahmud Kushān, the main character’s transformation is crucial. Initially a violent and authoritative figure, he experiences a turning point when he is disappointed by his lover. He then decides to go to the mosque in Mashhad to mourn his misfortune. The breathtaking sight of the massive domes and towering minarets completely dominates the scene, almost entirely overshadowing the movie’s main character, making him appear diminutive and insignificant in comparison. This overwhelming architectural grandeur echoes Sir Aurel Stein’s description of Mashhad during his visit, where he noted: “The principal mosque, still an imposing building in spite of far-advanced decay, has three wide vaulted halls facing a quadrangular court lined on the other sides…”36Sir Aurel Stein, Old Routes of Western Iran, Narrative of an Archaeological Journey Carried Out and Recorded by Sir Aurel Stein (London: Mac-Millan Edition, 1940), 93.

Notable Examples of Ziyārat’gāhs in Iranian Cinema

Figures 36 to 42 feature further interesting and iconic examples of images of Ziyārat’gāhs in Iranian films of the pre-revolutionary period.

Figure 36. Tawqī (Wood Pigeon, 1976), directed by ʿAlī Hātamī. Sayyid Murtazā enters a mosque and hides among worshippers praying, deterring potential attackers due to the mosque’s significance.

Figure 37. Khānah-ʼi Khudā (The House of God, 1966) directed by Jalāl Muqaddam. The movie’s religious theme deeply resonated with Iranian audiences, attracting many to experience the magic of cinema for the first time.

Figure 38. A scene of a Shamʿ’khānah in Shārlūt bih bāzārchah mī-āyad (Charlotte is Coming to Market, 1977), directed by ʿAbbās Jalīlvand.

Figure 39. Shīrbahā (Bride Price, 1972), directed by Robert Ekhart. Gul-Bānū seeks solace and shares her deepest thoughts, fears, and hopes with a trusted confidant in the intimate setting of a shamʿ’khānah.

Figure 40. Qiyāmat-i ʿIshq (Hell of Love, 1973), directed by Hūshang Hisāmī. The main character, deeply devoted to his faith, tragically meets his end in a saqqā’khānah.

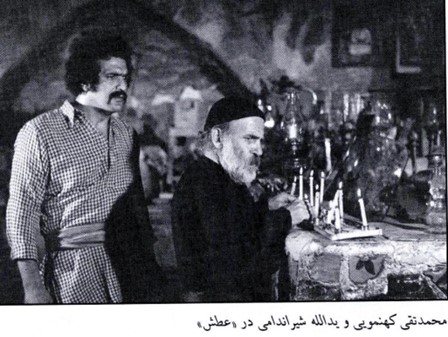

Figure 41. ʿAtash (Thirst, 1972), directed by Īraj Qādirī. The main character and his beloved partner are willing to face any danger, even risking their lives, to establish a shrine (zarīh) in their village.

Figure 42. Majīd Muhsinī’s Lāt-i Javānmard (The Noble Rogue, 1958). The narrative of the film revolves around a father’s pilgrimage to Mecca and his responsibility to leave his daughter in the care of a local nobleman.

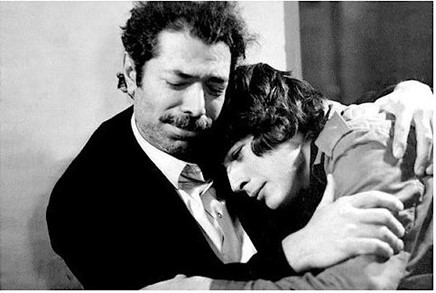

Khānah (The Family Home): The Place of Gathering, Refuge, Love, and Stability

The khānah, an iconic symbol of the family home, holds a significant place in Iranian national cinema. These modest brick houses,37As noted by Henri Stierlin, brick has long been a material of choice in Iran. Stierlin observes, for instance, how “For as long as we can remember, the great works of Iranian architects and builders, whether for dwellings, sanctuaries, or palaces, have been made of brick. Such is the case with the Ziggurat of Tchoga-Zambil (built in the 13th century BC).” See Henri Stierlin, Ispahan, image du paradis (Ispahan, the Image of Paradise) (Lausanne-Paris: La Bibliothèque des Arts, 1976), 85-86. Gaspard Drouville, in his observations of life, describes a striking feature of the homes in urban areas, noting that “in urban areas, homes are frequently enclosed by tall walls, hiding their fronts in spacious courtyards set back from the streets.” See Drouville, Voyage en Perse, pendent les années 1812 et 1813, 1:95. often portrayed as characters in their own right, are not just architectural elements.38A memorable example of one of these houses taking up the role of character can be seen in Amīr Shirvān’s Dirakhtān Istādah Mīmīrand (Trees Die Standing, 1971), set in a wealthy woman’s home, which takes center stage as the film’s primary setting and location. The lavish house and its decorations play an essential and unmissable role throughout the film, adding to the captivating atmosphere of the story. Rather, they serve as narrative devices, reflecting each film’s social and historical context. The khānah symbolizes the gathering place, refuge, love, and stability for the characters of a film. It is a source of reassurance and secrets, and above all, it represents the family. Scholars, such as Parvīz Ijlālī, have highlighted this vital element of traditional familial connection, especially in Iranian cinema, arguing that “The importance of family and its great role in individual life is one of the main traditional aspects of Iranian society. This characteristic was very well shown and highlighted in the popular Iranian films of these years (pre-revolutionary periods) … Even the lonely hero, like the one in Qaysar, revolted only because of family matters (the rape of his sister).”39Parvīz Ijlālī, Digargūnī-hā-’i ijtimāʿī va film-hā-i sīnimāyī dar Īrān (Social Changes and Feature Films in Iran) (Farhang va Andīshah, 2004), 408.

Traditionally, the khānah is so deeply rooted in Iranian society that its presence is as sacred as places of worship such as a mosque. In Iranian Cinema, it is the place that all the main characters must return to at some point or another. Of course, this place must also be protected. No intruder is allowed to cross the boundary, or he will be severely punished. The house also represents the place where women are protected from the gaze of men, and thus where they can finally be free, even more so than the hammām. They can take off their chadors and headscarves and even bathe naked in the courtyard pool (like Zarī in Tawqī). These elements of social life make this place not only as sacred, but also just as crucial as the mosque. Indeed, exploring Iranian sociology and culture is incomplete without delving into this unique and pivotal place within Iranian society. Further, and in this way similar to hammām, the khānah is also the hub where numerous crucial decisions are made, including social, commercial, and political matters, and where marriages (frequently), religious ceremonies, national holiday celebrations, and funeral wakes are held.

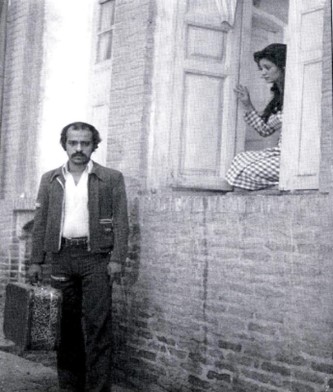

Khānah: The Place of Refuge

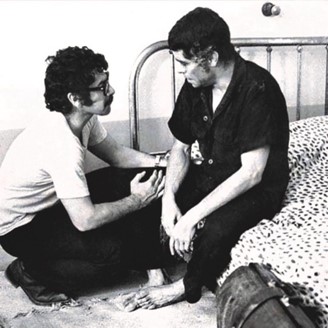

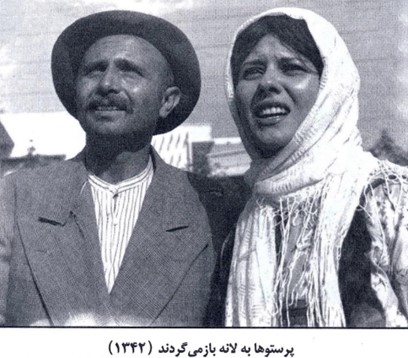

Home is, first and foremost, a safe place—the location where a protagonist first seeks refuge from the police just as readily as the fugitive returns to in order to find sanctuary (see Figure 43). For example, in Subh-i Rūz-i Chahārum (The Morning of the Fourth Day, 1972), directed by Kāmrān Shīrdil, Amīr finds no other place of safety besides his mother’s house after his accident and the crime he has committed. As well, in Nākhudā (The Captain, 1973) directed by Amīr Shirvān, one of the characters, Muslim, hides in the titular Captain’s house to escape the police who have falsely accused him of having killed a fisherman. These are only a few of many examples. As noted by Robert Graham, in a life filled with many obstacles, dangers, and violence, “the family is still regarded as the only effective bulwark against the hostile outside world.”40obert Graham, Iran: The Illusion of Power (London: Groom Helm, 1979), 197. On this subject, it is worth mentioning the following movies which share this thematic motif: Parastū’hā Bih Lānah Barmīgardand (Birds Will Return to Their Nests, 1963), directed by Majīd Muhsinī, Gavazn’hā (The Deer, 1974), directed by Masʿūd Kīmiyāʾī, Tangnā (Impass, 1972), directed by Amīr Nādirī, and Mādar (Mother, 1990), directed by ʿAlī Hātamī.

Figure 43. In Gavazn’hā (The Deer, 1974), directed by Masʿūd Kīmiyāʾī, Qudrat, a fugitive, seeks refuge in the house of his friend Sayyid Rasūl.

Figure 44. Parastū’hā Bih Lānah Barmīgardand (Birds Will Return to Their Nests, 1963), directed by Majīd Muhsinī. Through its storytelling and evocative portrayal, the film captures the essence of finding solace and safety within one’s homeland.

Khānah: The Place of Weddings

Iran, a country deeply rooted in its religious beliefs, strongly emphasizes the sanctity of marriage, and relationships outside of this institution are often viewed with disapproval. Therefore, including wedding scenes, a cultural cornerstone, is necessary to ensure that a film resonates with the audience. In fact, over time, the wedding scene became increasingly important for a movie’s success, and, slowly, such scenes began appearing at the film’s beginning. For instance, in Bar Farāz-i Āsimān’hā (Beyond the Heavens, 1979), directed by Muhammad ‛Alī Fardīn, the hero swears in front of God and a mullah that he will be a good and faithful husband to his wife. Thus, from the movie’s very beginning, his relationship with his girlfriend becomes halāl (legitimate). Indeed, finding a pre-revolutionary movie without a wedding ceremony in the hero’s or lover’s house is almost impossible. These easily understandable “happy endings” were nearly always at the end of the films made in that period (if not, as mentioned, planted firmly at their very opening).41Examples of films which conclude with a wedding include Dar Justujū-yi Dāmād (In Search of a Groom, 1960), directed by Ārāmāʾīs Āqāmāliyān and Gidāyān-i Tihrān (The Beggars of Tehran, 1966), directed by Muhammad ʿAlī Fardīn.

The wedding ceremony as representative of the strength of familial bonds is another crucial factor in the success of these movies. The Iranian audience’s choice to watch a national film is thus a function of a film’s ability to represent their ideas and values. One of these values is the family but even more importantly the bonds of kinship and loyalty that familial ties represent. It is no coincidence that many movies end with the hero getting married, like in Ganj-i Qārūn (Qarun’s Treasure, 1965) and many others.42The film Ganj-i Qārūn (Qarun’s Treasure, 1965) and other films in this genre depict a very positive and admiring view of family and family homes. In Iranian cinema, it is rare to find a movie in this category (Fīlm-fārsī) that does not give the family the key role in the story. Even in the Iranian New Wave generation, where a different kind of cinema emerged, the family remains central to the story. In Qaysar, for example, the rape of the sister and the tarnished honor of the family are the triggers of the story. In a decidedly less bleak fashion, in Ganj-i Qārūn, all of the movie’s happy scenes take place in a home: parties, weddings, reunions, meals. Like Shīrīn’s father, the men who look happy and prosperous are married men who spend their time at home with their wives and children. To be happy again, Qārūn must return home to his wife and son, ʿAlī. The movie ends with him bringing his wife to their son’s wedding. Finally, the smile returns to his face. The main character, ʿAlī Bīgham, also marries a wealthy merchant’s daughter and inherits Qārūn’s money, a happy ending that appeals to many spectators. The formula “they got married and had many children” is almost the final goal of all these films, where the hero, despite all his affairs with various women, finally marries only one to settle down and start a family. Thus, the hero becomes a respectable married man and, later, a good father and citizen. He gives the image of a perfect character in harmony with society and the people (i.e., the spectators).

The power of the connection between the audience and Iranian cinema of this period, through a film’s ability to represent traditional, “respectable” bonds of family, cannot be overemphasized. As with other locations that represented the experiences of an average citizen (e.g., the hammām), depictions of weddings held in khānah spoke to the majority of the population who were not wealthy. This was far different from today’s substantial ceremonial events in hotels and palaces designed for such occasions. In the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s, most weddings occurred in people’s homes (i.e., the khānah), especially in the working-class neighborhoods where most movies were shot.

Indeed, there is a wide range of films depicting family wedding ceremonies taking place within a household setting such as this. Some of these include:

- Mihmān (The Guest, 1976), directed by Kāmrān Qadakchiyān.

- Mard (The Man, 1972), directed by Mahdī (Farīdūn) Zhūrak.

- Gidāyān-i Tihrān (The Beggars of Tehran, 1966), directed by Muhammad ʿAlī Fardīn.

- Sih Qāp (Knucklebones, 1971), directed by Zakariyā Hāshimī.

- Ganj-i Qārūn (Qarun’s Treasure, 1965), directed by Siyāmak Yāsamī.

- Mahdī Mishkī Va Shalvārak-i Dāgh (Mehdi the Black and Hot Mini Pants, 1972), by Nizām Fātimī.

- Pāshnah Talā (The Golden Heel, 1974), directed by Nizām Fātimī.

- Kūchah-yi Mardhā (Alley of Valiants, 1970), directed by Saʿīd Mutallibī.

- Laghzish (Instability, 1953), by Mahdī Raʾīs-Fīrūz.

- ʿAyyūb (1971), directed by Mahdī (Farīdūn) Zhūrak,43The houses in the film play a crucial role in setting the stage for almost all scenes, providing a significant backdrop to the story. and

- Taʿassub (Intolerance, 1975), directed by Taqī Mukhtār.44Other examples include: Mast-i ʿIshq (Drunk of Love, 1951), directed by Ismāʿīl Kūshān, Yak Nigāh (A Look, 1952), directed by Hāyk Gārāgāsh, Vilgard (The Wanderer, 1952), directed by Mahdī Raʾīs-Fīrūz, Rūz-hā-yi Tārīk-i Mādar (Mother’s Dark Days, 1967), directed by Muhammad ʿAlī Zarandī, Mādar dūstat dāram (Mother, I love you, 1975), directed by Dāryūsh Kūshān, Mujāzāt (Punishment, 1975), directed by Mahdī Fakhīm-Zādah, Ghayrat (Honor, 1975), directed by Jahāngīr Jahāngīrī, Shab-hā-yi Tihrān (Tehran Nights, 1953), directed by Siyāmak Yāsamī, and Āqā-yi Jāhil (Mr. Jahel, 1974), directed by Rizā Mīrlawhī. For an example of a film that depicts the celebration of a child’s birth at home, see Jūjah Fukulī (Baby Dandy, 1974), directed by Rizā Safāyī.

Figure 45. Murakhkhasī-i Ijbārī (Mandatory Leave, 1965) by Rizā Karīmī. A wedding ceremony held at home serves as the perfect conclusion.

Figure 46. Dukhtar Talā (Golden Girl, 1967) directed by Sardār Sāgir. The movie comes to a close with a somewhat unconvincing wedding celebration taking place at the characters’ home.

Khānah: A Place of Intimacy