Iranian Poetic Cinema: Historical Perspectives and Reflections

Figure 1: A still from the film Where Is the Friend’s House? (Khānah-yi dūst kujāst?), directed by ‛Abbās Kiyārustamī, 1987.

Introduction

Poetic cinema and film poetry are significant in global cinema history, especially in Europe. These ideas express different aspects of processing poetic material and developing narrative themes. They also propose new methods for expressing ideas in cinematic language to create innovative artistic forms. Exploring the connections among poetry, literature, and film can uncover new opportunities for structuring narrative information, examining linguistic variations, and grasping the contemporary essence of film as a multimedia system. Since poetic cinema has faced numerous verbal equivalents in studies since the 1950s, it is evident that a clearer understanding of the historical developments of this concept and its reflection in contemporary world cinema is especially significant. This study initially explores the historical evolution of this concept and its diverse lexical forms during the turbulent rise and decline of European cinematic style trends. These historical insights will offer a theoretical roadmap for suggesting the factors and methodological model of analysis for the Iranian films explored. The concept of poetic cinema will be introduced through scholarly discourse, focusing on its historical evolution in European film studies. The article then categorizes and presents Iranian poetic cinema’s key criteria and indicators. This allows readers to gain a deeper understanding of the requirements and methods for addressing this concept within Iranian cinema while also considering the historical context of the discussion from a global perspective. Next, the article will explore the historical context of Iranian cinema over the last fifty years by categorizing Iranian films and presenting a conceptual map based on four factors: verbal and written expression, visual and observational expression, emotional-sensational expression, and cinematic perception. In the next stage, several notable films in Iranian cinema will be analyzed, including the poets’ discourse on the text, dialogues, poetic content, cinematic images, and poetic subgenres. Evidence and examples will be provided for each film and filmmaker mentioned, and the concept of poetic cinema within them will be explored.

Poetry and Prose in the History of Cinema

Figure 2: A still from the film Water, Wind, and Dust (Āb, bād, khāk), directed by Amīr Nādirī, 1985.

In the 1920s, French cinema began to explore new ideas, while scholars from the Russian formalism school were already examining the connections between film and poetry. Notable critics such as Boris Eichenbaum and Viktor Shklovsky emphasized the symbolic nature of cinema, drawing on their literary knowledge and poetic techniques. Their ideas were first published in Russian in the Poetics of Cinema (1927), which examined the symbolic relationship between film and poetry. In his article “Problems of Cine-Stylistics” (1927), Eikhenbaum defines the concept of the Cine-phrase as a group of elements clustered around an accentual nucleus, perceivable as segments of moving materials, whether verbal or musical. He defines a Cine-phrase as a shot that can be lengthened or shortened, with longer shots creating the impression of a slowly developing narrative. Eikhenbaum explores the potential for meaning within a film’s linguistic structure, stating that filmic expressions arise from visual, audio, and movement signs. The transfer of concepts between viewpoints occurs through what he terms spatio-temporality, or the Cine-Period.1Boris Eikhenbaum, “Problems of Cine-stylistics,” In Russian Poetics in Translation, vol. 9: The Poetics of Cinema, ed. Richard Taylor (Oxford: RTP Publications, 1982), 22-25.

In “Poetry and Prose in Cinema” (1927), Shklovsky highlights the poetic potential of visual signs in film, paving the way for the reader-response studies in cinematography that would emerge in the 1960s. He examines the creative techniques of Dziga Vertov, comparing the arrangement of various shots to how a poet combines words and sounds to evoke an unfinished concept in the reader’s mind. Viktor Shklovsky argues that cinema employs poetic techniques to express its aesthetic values. He believed that the key difference between poetry and prose lies in the “greater geometricality” of poetic devices. In his view, a series of arbitrary semantic interpretations is replaced by a formal geometric resolution. Furthermore, he explained that poetry and prose in cinema are distinguished by rhythm. Poetic cinema prioritizes technical and formal elements over semantic ones, which shape the overall composition.2Viktor Shklovsky, “Poetry and Prose in Cinema,” In Russian Poetics in Translation, vol. 9: The Poetics of Cinema, ed. Richard Taylor (Oxford: RTP Publications, 1982), 88-89.

Dziga Vertov viewed himself as a poet, using poetry to influence his films instead of traditional scripts. He stated, “I am a film poet. However, instead of writing on paper, I write on the film strip.”3Germaine Dulac, “The Essence of the Cinema: The Visual Idea.” In The Avant-Garde Film: A Reader of Theory and Criticism, ed. P. Adams Sitney (New York: Anthology Film Archives Series, 1987), 38. He regarded film as a visual poem, utilizing techniques to evoke emotional and intellectual responses. As Eugene McCreary notes, when Dulac referred to the film as “Visual Poetry,” he highlighted the creative act of isolating and stylizing significant details. Despite drawing inspiration from poetry, however, Dulac firmly believed that cinema should break free from the constraints of literature and verbal processing patterns and instead discover new ways to comprehend the unique visual language of film: “Every cinematic drama […] must be visual and not literary […] A real film cannot be able to be told since it must draw its active and emotive principle from images formed of unique visual tones.”4Germaine Dulac, “From Visual and Anti-Visual Films,” In The Avant-Garde Film: A Reader of Theory and Criticism, ed. P. Adams Sitney (New York: Anthology Film Archives Series, 1987), 31, 35.

Man Ray, an American photographer is the first artist to suggest that “a series of fragments, a Cine-poem with a certain optical sequence make up a whole that remains a fragment. […]. It is not an ‘abstract’ film nor a story-teller; its reasons for being are its inventions of light-forms and movements, while the more objective parts interrupt the monotony of abstract inventions or serve as punctuation.”5Man Ray, “Emak Bakia,” Close-Up 1, no. 2 (August 1927): 44-45. Susan McCabe considers Man Ray’s works to be very close to Gertrude Stein’s poetic style and compares the characteristics of their verbal or visual data organization. “The kinship between modern poetry and film […] hinges upon the subordination of plot to rhythm, but also upon a montage aesthetics that privileges the fragment and its abrasion of other fragments” […] “Like Stein’s writing, Man Ray’s film denies a stable subjectivity.”6Susan McCabe, “Delight in Dislocation: The Cinematic Modernism of Stein, Chaplin, and Man Ray.” Modernism/Modernity 8, no. 3 (2001): 431.

On October 28, 1953, a seminar focused on poetic film, gathering critics, writers, playwrights, and filmmakers. Maya Deren, an American experimental filmmaker, focused on capturing the pure essence of cinematic expression and eliminating non-cinematic elements. She insisted on avoiding literary adaptations, abstract animation, or imitating reality in film. In ‘Anagram,’ poetry is the only art form from which Deren permits borrowing creative methods without her usual warnings against misappropriation.7Renata Jackson, The Modernist Poetics and Experimental Film Practice of Maya Deren (New York: Edwin Mellen Press, 2002), 111.

Poetry is defined by its construction, Deren argued, and “the poetic construct arises from the fact that it is a ‘vertical’ investigation of a situation, in that it probes the ramifications of the moment, and is concerned with its qualities and its depth so that you have poetry concerned in a sense not with what is occurring, but with what it feels like or what it means.”8Maya Deren, speaking in Willard Maas, “Poetry and The Film: A Symposium,” Film Culture 29 (1963): 56. Deren then adds, “just as the haiku consists not of the butterfly but of the way the poet thinks and speaks of the butterfly, so my filmic haiku could not consist of movements of reality but had to create a reality, most carefully, out of the vocabulary and syntax of film image and editing.”9Willard Maas, “Poetry and The Film: A Symposium,” Film Culture 29 (1963): 56. Although this core principle remained, Deren encountered various issues with the comparison, mainly regarding how to structure her film haikus. She argued that “one has random access to a book of haiku… but a film made up of haiku would necessarily be in an imposed sequence,” bringing up the question of “what is the principal, the form which would determine such a sequence? […] Common locales? […] Increasing intensity? Contrast? Perhaps like the movements of a musical composition?”10Maya Deren, “On a Film in Progress,” Film Culture 22-23 (1961): 161.

Evolution of Poetic Films

Poetic film emerged in European cinema studies after World War II and has evolved significantly over the past century. Initially labeled as film poem, film poetry, poetic avant-garde film and similar terms, these often-overlapping concepts have changed meaning over time. From 1965 to 1975, new descriptive combinations arose in modern cinema. Today, advancements in media technology have led to various innovative forms of documentary films, referred to as ‘poetry films,’ ‘video poems,’ ‘e-poetry,’ and ‘screen poetry.’ Filmmakers often blend verbal, auditory, and visual elements to evoke emotions. This fusion of poetry and cinema forms the two-way interaction known as poetic cinema, which continues to evolve.

The development of ‘Poetic Cinema’ can be divided into three periods: the ‘formation’ period, the ‘conceptual maturity’ period, and the ‘multiplicity of genres’ period. This classification clarifies conceptual and aesthetic complexities while adopting a perspective of evolution. From 1925 to 1950, the Moscow literary movement and the European avant-garde shaped poetic filmmaking. Key figures such as Shklovsky and Mayakovsky and filmmakers such as Vertov, Pudovkin, and Eisenstein played a pivotal role in the development of poetic film. During this formative period, there was a strong emphasis on originality and unique cultural expression through the language of cinema. Vertov called this an experiment in communicating visible events without intertitles or theatrical elements. His goal was to develop a universal language of cinema, distinct from theatre and literature.11See Dziga Vertov, dir. The Man with a Movie Camera. 1929, Moscow, VUFKU & Dovzhenko Film Studios.

Artists’ early efforts to outline poetic cinema simplified its structure, aligning it with visual arts such as painting and graphics. French abstract cinema and Dadaist experimentalism removed verbal elements, creating a stylized form that was often challenging for audiences. This avant-garde approach transformed cinema into a more elite visual experience, distancing it from mainstream entertainment and creating a divide between “film as entertainment” and “film for film’s sake.”

The intentional pacing of images in film led to the creation of a visual poem that expressed human instincts and emotions through visual harmonies rather than facts.12Germaine Dulac, “The Avant-Garde Cinema.” In The Avant-Garde Film: A Reader of Theory and Criticism, edited by P. Adams Sitney (New York: Anthology Film Archives Series, 1987), 47. Filmmakers did not differentiate between poetic and musical languages, focusing on form over content in their non-narrative art. Dulac claims, “Just as in a symphony, each note contributes its vitality to the general line, each shot, each shadow moves, disintegrates or is reconstituted according to the requirements of a powerful orchestration.”13Eugene C. McCreary, “Louis Delluc, Film Theorist, Critic, and Prophet,” Cinema Journal 16, no. 1 (Autumn 1976): 23.

Between 1955 and 1975, poetic cinema advanced significantly alongside the evolution of film studies. This established cinema as an independent language that interacts with other art forms, such as poetry, novels, and painting and music. The term “Poetic Film” emerged to describe this interdisciplinary approach. Abel Gance noted, “…the marriage of image, text, and sound is so magical [here] that it is impossible to dissociate them in order to explain the favorable reactions of one’s unconscious.”14Anaïs Nin, “Poetics of The Film.” Film Culture 31 (1963-64): 14.

Prominent European filmmakers such as Michelangelo developed personal artistic expressions reflecting their own cultural and sociological variations. The universal significance of transcendental themes gradually diminished, blending film and poetry with various conceptual approaches. For example, Antonioni’s narrative, editing, and long takes blend rationality and emotion in marriage conflicts.15Peter Brunette, The Films of Michelangelo Antonioni (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), pp 1-27. In Antonioni’s style, poetry minimizes dialogue, utilizes extended frames to enhance visuals, and portrays unstable love relationships portrayals.16Matilde Nardelli, Antonioni and the Aesthetics of Impurity: Remaking the Image in the 1960s (Edinburgh University Press, 2020), p 161. Alain René’s work explores connections between places, fluid memories, and trauma from separations. This modern cinema era links to writers of the new novel who crafted unique cinematic narratives language.17Griselda Pollock, & Max Silverman, ed. Concentrationary Cinema: Aesthetics as Political Resistance in Alain Resnais’s Night and Fog (Berghahn Books, 2012), p 178.

Ingmar Bergman explored sensitive themes from Christian teachings, using light and striking mise-en-scène to examine humanity’s relationship with death, sacredness, and hope salvation.18Jesse Kalin, The Films of Ingmar Bergman (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), pp 1-33. In Persona (1966), he revealed the magic of enclosed shots, especially in intimate dialogue scenes centered on women, poetically and sometimes sorrowfully portraying the dark shadows of female identity. Bergman’s poetic narrative of human experiences uniquely blends emotion and intuition in cinema Bergman.19Geoffrey Macnab, Ingmar Bergman: The Life and Films of the Last Great European Director (London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2009), p 175. Andrei Tarkovsky’s Mirror (1975) is also a nostalgic and poetic reflection of the filmmaker’s childhood.20Andrey Tarkovsky, Sculpting in Time: Tarkovsky, The Great Russian Filmmaker Discusses His Art, transl. Kitty Hunter-Blair (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1989), pp 231-238. It depicts his experience reading his father’s poems and discovering his mother’s femininity. The film features unique visuals, poetry readings, and the interplay of past, present, and future through dreams. Likewise, Nostalgia (1983) conveys the sorrow of exile and distance from home through a blend of images, movements, and voice whispers.21Nariman Skakov, The Cinema of Tarkovsky: Labyrinth of Space and Time (London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 1989), p 167.

The film-poetry hybrid has evolved significantly since the late 1980s, with the influence of postmodernism and the technological advancements of the early 1990s. The third stage integrates intellectual and psychoanalytical frameworks of human experience with artists’ emotional creativity. Over the past thirty years, advancements in digital communication, internet connectivity, video gaming, and the proliferation of virtual networks have contributed to a redefined understanding of the relationship between reality and the virtual. William Wees’s term ‘poetry film’ is now less commonly associated with poems. Wees noted that these designations indicate different genres: filmmaker Ian Cottage uses “poem film,” while poet Tony Harrison prefers ‘film poem.’22William Wees, “Poetry Film,” in Poem Film Film Poem, ed. Peter Todd, Newsletter 4 of the South London Poetry Film Society, March 1998, 5. Robert Speranza, who has studied the work of Harrison and the British film-poem, suggests that the new poets and filmmakers that came together “attempted spontaneous creation of film and verse (within reason), calling the results ‘film/poems’ or ‘film-poems.’” 23William Wees, “Poetry Film,” in Poem Film Film Poem, ed. Peter Todd, Newsletter 4 of the South London Poetry Film Society, March 1998, 5; Robert Scott Speranza, “Verses in the Celluloid: Poetry in Film from 1910-2002, with Special Attention to the Development of the Film-Poem” (PhD diss., University of Sheffield, 2002), 119. I use the hyphen to distinguish these from other types of film poems.

Iranian Poetic Cinema: Methods and Factors

Iranian cinema’s growth stems from diverse experiences of filmmakers, shaped by political trends and social movements, particularly between 1946 and 1996. Cinema has become vital to Iran’s sociopolitical landscape, reflecting the desire to merge tradition with modernity while promoting freedom of expression. This success has been achieved by blending poetry and visual arts to revitalize national identity and showcase modern Iranian complexity and richness.

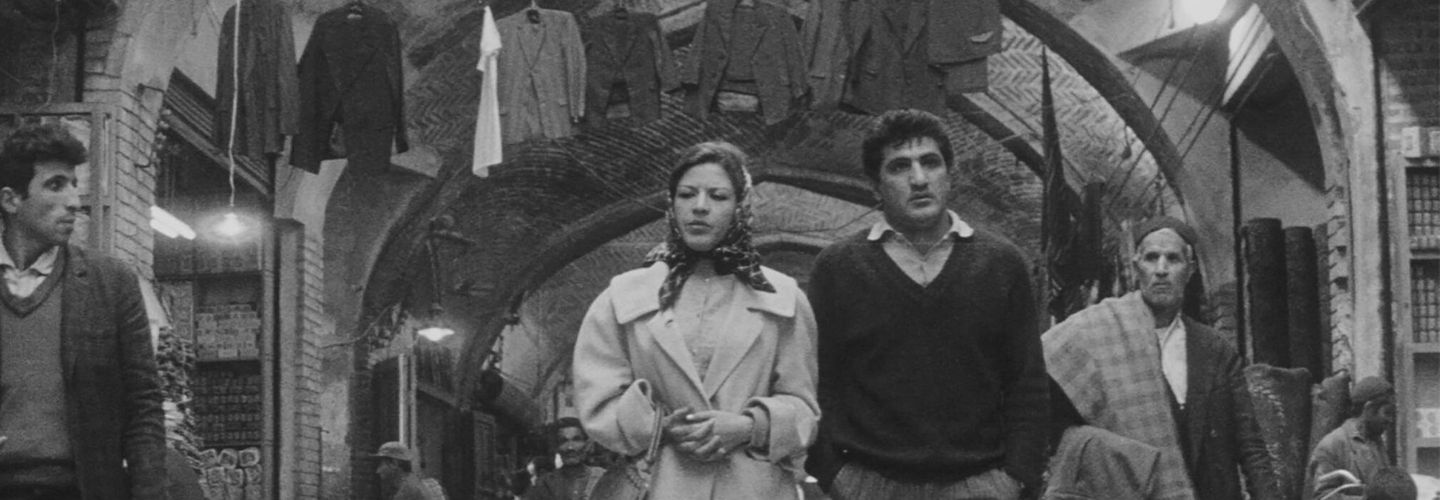

The relationship between cinema and literature in Iran began with ‛Abd al-Husayn Sipantā and Ardashīr Īrānī, who adapted themes from classical poetry to film. From 1956 to 1978, Iranian cinema changed significantly due to socio-political movements, reflecting public expectations. Until the mid-1960s, films resembled popular Indian romantic tales, incorporating poetry and music to appeal to the middle and working classes. Successful films thrived through foreign investments, resonating with audiences via romantic protagonists and local references. This era shifted towards one of independent cinema, driven by critical discourse and analysis.24Khatereh Sheibani, The Poetics of Iranian Cinema: The Aesthetics of Poetry and Resistance (London and New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2016), 16.

In 1953, Amīr-Hūshang Kāvūsī, a French-educated critic from the Institut des Hautes Études Cinématographiques (IDEC), coined the term Fīlmfārsī, which became the dominant label. He claimed that the only element these films inherited from Iranian culture was their Persian language; otherwise, they were “formless, structureless, and storyless.”25Hamid Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema. Vol. 2: Industrializing Years, 1941-1978 (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2011), p 149

In the 1950s-60s, as Fīlmfārsī rose, alternative currents influenced Iran’s art cinema and New Wave. Since the 1920s, Iranian poetry has evolved through formalism, surrealism, and symbolism. This transformation aligned literature with drama and cinema. Prominent poets expanded literary circles, enhancing linguistic artistry—metaphor, metonymy, allegory, and irony—in Iranian drama. Post-1950s efforts revived classical techniques and modernized poetic language, merging poetry with storytelling through film. The return of educated intellectuals from France brought avant-garde movements to Iranian cinema. The New Wave rose to prominence in the mid-1960s during a 15-year cultural renaissance, highlighting Iranian identity in film. Much of Iranian avant-garde cinema’s poetic essence stems from the strong ties between poetry, storytelling, playwriting, and art films. This aesthetic interaction continued for at least 20 years after the 1979 Islamic Revolution, with many films achieving international recognition due to the filmmakers’ sustained efforts and dedication.

Since the 1960s, three genres—documentary, fiction, and docufiction—have emerged. Iranian documentary cinema has been influenced by experimental trends from France and Germany, with filmmakers pursuing innovative ways to connect cinema with visual arts, literature, and narrative poetry by extracting themes into abstract ideas. Ethnographic documentaries showcasing Iran’s beauty and culture offer new opportunities for artists. They explore Iranian identity using poetic methods, develop new storytelling techniques, and enhance the narrator’s role in voice-over, achieving unique expression documentaries.

In the 1970s, the Institute for the Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults (Kānūn) produced educational films to promote literacy and encourage poetic experimentation. Fiction films explored new ways to depict human emotions, often adapting modern Iranian novels and short stories. Fīlmfārsī cinema dominated Iranian filmmaking, while avant-garde art cinema attracted a smaller audience. Nevertheless, it earned recognition and praise from the educated elite and critics in literature and art. A thorough examination of the developments in Iran’s alternative cinema between 1960 and 1975 shows that the most important poetic elements in documentary, docufiction, and fictional films can be analyzed across four dimensions: Verbal-inscriptional Presentment, Visual-observational Presentment, Sensational-emotional Re-presentment, and Filmic-perceptional Re-presentment.

By “presentment,” I refer to the explicit articulation of poetic experience within the film’s narrative—anything that can be articulated, heard, or seen. Presentments are defined by their clarity. Conversely, “re-presentments” involve implicit relationships between signs, including subtleties and connotations. While presentments are pure experiential data, re-presentments capture our sensory and emotional responses to poetic meanings in the narrative and the filmmaker’s artistic use of plot, cinematography, mise-en-scène, and editing.

Consequently, poetic re-presentments are primarily a form of meaning evocation or an analytical interpretation by the audience of the combined relationships between sensory, emotional, and kinetic signs within the filmic world. Unlike overtly visible and tangible poetic presentments, poetic re-presentments are often interpretative and vary based on the aesthetic literacy or cinematic receptivity of viewers and film critics. This conceptual relationship can be applied to analyzing shots, scenes, or sequences in the films discussed below and can be hypothetically and experimentally illustrated as follows.

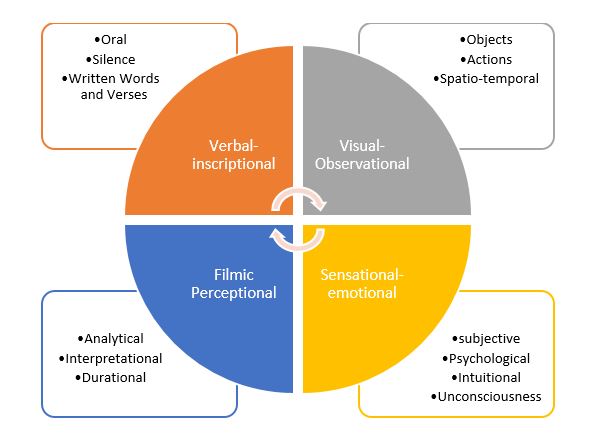

Chart 1: Poetic Elements in the World of Film; Explicit Presentments and Interpretative, Implicit Re-presentments (by the author).

Selected film scenes can combine all four dimensions from Chart 1. Nevertheless, a singular aspect typically prevails within the film’s poetic realm, known as ‘the dominant face of poetry.’ For instance, poetic dialogues or monologues signify the verbal expression of poetry. Similarly, silence, which signifies an emotional void between a husband and wife following a painful separation, clearly manifests their circumstances. A poem recitation, a zoomed photo, or a famous quote is a transparent poetic element in a film, allowing viewers to immediately grasp its expression and meaning. Whether the director’s approach is creative or clichéd, it enriches the film’s world with varied verbal, written, or visual elements. Additionally, the set design, the arrangement of objects, and the creative use of time—illustrated through the depiction of daily life—enhance the audience’s understanding of the film’s poetic qualities.

Visual elements shape the audience’s perceptions of hallucinatory scenes, nightmares, and tumultuous dreams in cinematic works. Key factors include lighting style, the pace of camera movement, shot duration, image rhythm, and character interactions. Skillful editing can evoke moods and enhance the narrative atmosphere through shot combinations, decoupage patterns, and alterations of actors’ movements, adhering to mise-en-scène principles. Each element can lead to various interpretations, reflecting the cinematic world and the characters’ emotional depths. Grasping these interpretations requires aesthetic literacy and critical sensibility, allowing the recognition of new combinatory logic in the film’s signifying relationships. Such representations enrich cinematic language, deepening meanings and interpretations for audiences, ultimately revealing the film’s essence poetically.

Poetic Effects in Iranian Cinema

This section highlights the unique artistic methods and styles that enhance the aesthetic appeal of Iranian cinema. Poetic films use distinct elements to convey the filmmaker’s vision and enrich the cinematic atmosphere. Despite the sometimes-amorphous principles, specific characteristics have evolved over time, influenced by artists’ and audiences’ preferences. Thus, poetics is evaluated using specific analytical criteria. As Khatereh Sheibani notes, “crucial changes took place both in fiction and documentary films made by Iranian filmmakers and cultural activists in the 1960s, inspired by literature and the dramatic arts. The impact of literature on cinema was mostly through a few poets and writers such as Forough Farrokhzad and Ibrahim Golestan, who were also filmmakers.”26Khatereh Sheibani, The Poetics of Iranian Cinema: The Aesthetics of Poetry and Resistance (London and New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2016), 18.

Narration and Poetic Narratives

In the late 1950s, filmmakers aimed to show innovative realities through unique editing techniques that went beyond representation. They employed harmonious language to deepen the audience’s comprehension of the images. The intricate coordination of cross-cutting shots and accompanying narration in the brief industrial and educational documentaries of the period gave viewers insights surpassing those of conventional realistic films. One of the first Iranian documentaries, Wave, Coral, and Rock (Mawj u Marjān u Khārā, 1957-1961), by Ibrāhīm Gulistān, poetically explores nature and human attempts to control it. This 40-minute film illustrates Khārk’s evolution into a crude oil port. The narrative thematizes the struggles between humanity and nature in the pursuit of energy resources. The film’s creative, poetic imagery endures as a significant work.

Figure 3: A still from the film Wave, Coral, and Rock (Mawj u Marjān u Khārā), directed by Ibrāhīm Gulistān, 1957-1961.

The opening scene displays a quality that, even after sixty years, still competes with the best nature films. Gulistān addresses the fish, an ancient inhabitant of the region, by inquiring, “What do you seek? The essence of a secret about today, or perhaps a seed for the genesis of tomorrow?” While fish function through instinct, humans must elevate their gaze from the water to fully perceive their surroundings. Next, the camera shifts to portray the person reflecting on the scene. The Film suggests that grace touched this island. This insightful film explores oil as a cultural and life force. It artfully weaves together various elements in a poetic documentary format. The tension between tradition and modernity emerges with the arrival of industrial machines, illustrated by massive stones being shifted by colossal rakes. Wave, Coral, and Rock is a living document of a pivotal moment in Iran’s history, presented poetically by a thoughtful writer and filmmaker.

The House is Black (Khānah siyāh ast, Furūgh Farrukhzād, 1962), which was made in collaboration with Ibrāhīm Gulistān, is a pioneering Iranian documentary offering a poetic perspective from a female filmmaker. Furūgh Farrukhzād’s 1964 poem, Another Birth (Tavalludī Dīgar), marks a milestone in modern Persian poetry. She became the leading voice for generations of Iranian women facing oppression in a patriarchal society. More than just a brilliant voice, Farrokhzad symbolizes the suffocated feminine presence in Iranian poetry.27Hamid Dabashi, Close Up: Iranian Cinema, Past, Present and Future (London and New York: Verso, 2001), 28. Her film depicts the lives of leprosy patients in a nursing home, isolated from society. Utilizing visual strategies like repeated movements and long shots of characters, the film conveys their daily suffering. It blends literary text and poetic expression to engage the audience emotionally. “The world contains much ugliness, but blindness to it exacerbates the issue. People can be solution-makers. This film reflects ugliness and pain to help remedy suffering and invoke awareness and compassion.”28Forugh Farrokhzad, The House is Black, 1963. 00:02-00:12. The film’s intelligent use of still shots and dynamic movements, combined with narration, captures the audience’s interest beyond the images.

One of the peculiar features of the inorganic intellectual is an affinity for metaphor and allegory. By transforming social realities into poetic parables they sustain the illusion that they have in fact launched a political struggle. This is principally the reason why Golestan’s influence on The House Is Black has been instrumental in creating a weak political reading of that film as a metaphor of the nation at large, rather than allowing its own dark vision—contemplating the long shadows of a colonially mediated modernity—to come true. In Golestan’s own documentaries, this tendency toward aesthetic metaphor was sometimes highly effective and resulted in brilliant works of art.29Hamid Dabashi, Masters and Masterpieces of Iranian Cinema (London and New York: Mage Publishers, 2007), 79.

Figure 4: A still from the film The House is Black (Khānah siyāh ast), directed by Furūgh Farrukhzād, 1962.

In the 1960s, Albert Lamorisse traveled to Iran, invited by the Ministry of Culture and Arts to create a film highlighting Iran’s historical and cultural heritage. The Lovers’ Wind (1978) illustrates the country’s diverse landscapes, including cities, villages, paddy fields, pastures, the sea, and the desert. Its richness lies in the poetic, bird’s-eye view narration, enhanced by literary text and the narrator’s voice. In one part of the film, the narrator says, “[…] the land of Isfahan where works of art and gardens intertwine,”30Albert Lamorisse, dir. The Lover’s Wind (1978), 00:21:26. in another part,

This hill called Susa is made out of cities we had buried. Recently, some people took a fancy to this to find these cities. They had to dig very deep so thoroughly had we done the job. The first city stood here thousands and thousands of years ago. Here, generation after generation people have toiled and rejoiced. We have buried everything, and the nomads have come roaming about the remains. But the city rose again, then broke in, and we buried everything. Thus, spread over uneven periods of time fifteen cities have grown and died here. Each had her great scholars, her great politicians, her great warriors, her great artists, each claimed to be not only the most beautiful city on earth, but also the mightiest and the wisest. Fifteen times we have overlaid them with dust and sand, and each time the nomads would come back.31Albert Lamorisse, dir. The Lover’s Wind (1978), 00:11:28-00:12:42.

Poetic Dialogues

Before the Islamic Revolution, the impact of literature on Iranian cinema’s international success was significant. In the 1960s and 1970s, cinema integrated narrative poems, theatrical stories, and cinematic scripts, with poetic dialogues. These concepts, rich in similes and metaphors, resonated as melodious poetry, embodying the essence of Iranian cinema across social statuses.

Figure 5: A still from the film The Lovers’ Wind, directed by Albert Lamorisse, 1978.

- 1-Hātamī and Poetic Language

‛Alī Hātamī was a prominent Iranian New Wave filmmaker. His films highlighted Iranian culture and literature with poetic dialogue that celebrated Persian language. Hātamī combines visual elements (stage design, costumes, architecture) and auditory components (dialogue, music, sound) to express Iranian cultural identity. His stories merge history and tradition, offering a unique literary voice. His cinematic work is akin to painting with music and words. Hātamī constructs lyrical tableaux that draw inspiration from Iran’s rich cultural heritage, skillfully integrating the vernacular of everyday individuals into his scripts. Describing his own particular film language, he stated:

Since starting to write scripts, I have sought a unique language that reflects our characteristics. I realized we often fail to express our intentions clearly. Irony permeates our speech; we frequently use proverbs, sayings, or references from religious texts. This tone resembles storytelling. To support our arguments, we reference ancient poems, and itinerants often sell their wares with rhythm and rhyme. We also use rhythm to express social and political messages. Thus, this language embodies our people’s mood and culture.

The title “Iranian Cinema Poet” aptly characterizes ‛Alī Hātamī. His dialogue embodies Iran’s vibrant cultural and historical legacy, weaving in elements such as Gulistān Palace, Takyah Dawlat, and traditional Persian artifacts to define their identity. His films combine Persian miniatures with music, costumes, and editing, helping to preserve Iran’s ancient culture. However, the local nuances can present challenges for translation while attempting to preserve their essence.

Sūtah-Dilān (Desiderium, 1977) is one of Hātamī’s critical films from this period; the film’s scenes exemplify literary and poetic depth in storytelling and dialogue. In a powerful monologue, the protagonist laments: “Everyone claims a liar is God’s enemy […] How many enemies do you have, God! Your friends are us! A group of helpless, mentally ill individuals You turned into enemies!”32‛Alī Hātamī, dir. Sūtah-Dilān (Desiderium, 1977), 00:11:56.

Figure 6: A still from the film Sūtah-Dilān (Desiderium), directed by ‛Alī Hātamī, 1977.

Hātamī’s dialogues often serve as moral insights, reflecting their origins in classic Iranian literature. In Sultān-i Sāhibqirān (1975), Amīr Kabīr states: “Dying is a right; dying at your hands is bitter. However, a desire to leave eases death. I am destined for new clothes today. Please wash away my pain and sadness.”33‛Alī Hātamī, dir. Sultān-i Sāhibqirān (1975), 01:04:22-01:06:27

In the Hizār Dastān TV series, which is a historical account of the role of Rizā Tufangchī in the Punishment Committee of the Ahmad Shah Qājār period, the hero of the story (Rizā Khushnavīs) says:

Eventually, this house of lovers, our beloved prison, has demanded us. Ibrāhīm and Ismā‛īl lived in the same body within me, so I said, ‘Ibrāhīm! Sacrifice Ismael, for the time, is right for sacrifice. I sacrificed him in front of this altar, and the ink of this writing comes from the blood of Ismā‛īl, the son we never had. Alas, the sheep did not reach us from the unseen world. For slaughtering, a reed pen had come from the reedbeds instead; the reed pen flowed smoothly in my palm; it was my inhalation, not a blow, but it had its exhalation. I was blowing into it, steadily blowing, breathing in, and then breathing out.34‛Alī Hātamī, dir. Hizār Dastān (1979-1987), Episode 11, 25:52- 26:32.

The character’s linking of his biography to a religious event is skillfully crafted with literary language. In Hātamī’s cinema, an example of poetic form appears during the ‛Ayd al-Azhā (‛Ayd-i Qurbān) scene in Hājī Vāshīngtun (Hajji Washington, 1983). The exiled diplomat sacrifices a sheep, expressing his desires and regrets about national identity with sharp, ironic remarks on the country’s political and social state. He states, “O sheep, you will not become a deer. Commitment to the light means not remaining off. The one sacrificed does not fear death; it is destined. You grew fat in vain; if you ate less, you would last longer. How clean is this white fawnskin, the sacrifice! Happy ‛Ayd al-Azhā.”35‛Alī Hātamī, dir. Hajji Washington (1982), ) 00:51:43-00:57:14

Figure 7: A still from the film Hājī Vāshīngtun (Hajji Washington), directed by ‛Alī Hātamī, 1983.

In Kamāl-al-Mulk (1984), Nāsir al-Dīn Shah’s talks with the Iranian painter, illustrating the chaotic state of art and honor. Kamāl al-Mulk remarks: “The world’s work leans towards moderation. We are all what we deserve… I make my wishes! The domain of art here has been poisoned, from Hafez to now!” Similarly, the king’s words resonate with the current cultural realities: “Nāsir al-Dīn Shah: The art school is not a cornfield with better crops yearly. Among the stars, only one shines brightly; the rest flicker.”36‛Alī Hātamī, dir. Kamāl al-Mulk (1984), 00:53:55-00:57:35

Figure 8: A still from the film Kamāl-al-Mulk, directed by ‛Alī Hātamī, 1984.

Hātamī’s film Dilshudigān (1992) expresses nostalgia for Iran through themes of love for the motherland, cultural experiences, and history. The film highlights sentiments like, “Love is a shield against adversity, and the mother’s gaze resembles a lover’s, hoping for reunion tonight.” Hātamī’s work captures melancholic themes and genuine emotions that resonate with Iranians, transcending mere storytelling to embody the Persian poetry and literature that serves as a basis of Iranian identity. This is vividly illustrated in the symbolism of Iranian artists in Europe: “With all my height, my hands have never reached my dreams. When fame feels unwanted, it is a blessing to have a home where its walls are missed. I wish the world were a music box, where all sounds are melodious, and words are songs.”37‛Alī Hātamī, dir. Dilshudigān (1992), 01:12:23

- 2- Bayzā’ī and Archetypes of Mythopoetic

Bahrām Bayzā’ī’s dramatic works (1950s-1990s) employ fictional languages and historical narratives in a literary manner. He appreciates the rich heritage of Persian literature, and the themes found in indigenous oral myths, which are reflected in his plays, scripts, and films—all infused with rhythmic language. His sorrowful reflections on ancient cultural traditions and ethnic customs are consistently apparent. His deep connection to Persian literature has fostered a unique language that transcends standard norms, capturing the poetry behind the myth. Myths serve as metaphors for timeless concepts passed orally through generations, depicting the compelling speech of heroes and narrators. This mythological influence shapes Bayzā’ī’s narratives, dramatic scenes, and characters’ wise, melodious dialogue.

Over the years, Bayzā’ī’s films have evolved, integrating poetry through minimal expressive forms such as spoken word and character narration. The interplay of words, literary arts, and linguistic creativity has added poetic depth to characters’ speeches, monologues, and dialogues. His works exemplify an eclectic approach to these discourses, focusing on modernizing Iranian artistic forms rather than imitating Western ones. He emphasizes identifying failures that allow internal tyrants and external invaders to thrive instead of blaming others for Iranian culture’s shortcomings.38Saeed Talajooy, Iranian Culture in Bahram Beyzaie’s Cinema and Theatre: Paradigms of Being and Belonging (1959-1979) (London and New York: I.B. Tauris, 2023), p 6.

Figure 9: A still from the film Ballad of Tārā (Charīkah-yi Tārā), directed by Bahrām Bayzā’ī, 1979.

Ballad of Tārā (Charīkah-yi Tārā, 1979) illustrates Iranian cinema’s frequent blend of myth, history, love, and poetry. Like many of Bayzā’ī’s works, it features a story rooted in myth—of a woman entangled in unrequited love with a warrior. Men and women from different backgrounds engage in a lyrical dialogue of forgetting and remembering as their survival and destruction intertwine:

Historical man: My descendants see me now, and I cannot return; I am ashamed! My wounds trouble me!

Tārā: You should have treated them!

Historical man: These wounds cannot heal! Do you hear? They are old but not hopeless; new blood flows from them!

Tārā: Since when?

Historical man: Ever since I saw you! […] This is where our conquest’s flag was raised; this is the division’s base that marched over our fallen. What rivers flowed from our blood? In temptation and anxiety, we were deceived! They testified to God’s word and sold their oaths for coins. The cry rose from the heart like blood! How can anyone escape this desperate war? I am leaving. […] Tārā! Your look is all I take! Alas, why must I die again? Show me a battlefield; I will be the soldier! This war is unfair; you are more robust, and this fallen sword signifies surrender. My wounds bear no honor! Your life was carefree; what have I given you? Only my bleeding wounds! I regret it!39Bahrām Bayzā’ī, dir. Ballad of Tārā (Charīkah-yi Tārā, 1979), 00:25:30-00:26:50

The Death of Yazdgird (Marg-i Yazdgird, 1980) is a notable adaptation of one of Bayzā’ī’s plays, offering a unique perspective on the Persian king’s refuge with a miller post-defeat. The narrative follows Yazdgird, the monarch of Iran, who fled to Marv, one of the prominent metropolitan areas of ancient Iran, during the Arab conquest in the seventh century. It unfolds through the voices of the miller, his wife, their daughter, and others, each presenting distinct viewpoints. The characters’ dialogue is rich and poetic:

The Miller: What did the elders say about the king fleeing in his land?

Woman: Nothing important!

The Miller: I run from house to house, feeling like a stranger. No table to host me, no bed to sleep in. My hosts are fleeing, too. Instead of leading me to battle, the warhorses took me away. Shame on me!

Woman: We have never killed a guest!

The Commander: We hunted for death unknowingly. The Day of Judgment is not over. Watch as the judges arrive, a vast army. They do not say hello or goodbye; they ask nothing and listen to no answers. They speak the sword’s language.40Bahrām Bayzā’ī, dir. The Death of Yazdgird (1980), 00:10:43-00:14:16

Figure 10: A still from the film The Death of Yazdgird (Marg-i Yazdgird), directed by Bahrām Bayzā’ī, 1980.

In Passengers (Musāfirān, 1991), the filmmaker blends epic and dramatic effects. The story carries mythological qualities, infused with symbols like mourning, weddings, and mirrors, which reflect good news in Iranian culture. A family misses their wedding celebration while the mother awaits the symbolic arrival of travelers on an endless road. The elderly mother’s account of the accident is both bitter and poetic: “Curse the roads if they lead to separation!” 41Bahrām Bayzā’ī, dir. The Passengers (1991), 001:25:34

Another example of literary speech processing appears in Pardah-yi Ni’ī (1986): “We taught you what we knew, but we do not know a cure for grief.”42Bahrām Bayzā’ī, Pardah-yi Ni’ī (Tehran: Rawshangarān, 2003), p 35. Similarly, Siyāvash-Khvānī (1993) features Siyāvash’s speech, which combines myth and melody, showcasing the rhythm between film language and poetry.

Siyāvash: What happened to our relatives that we shed blood? You suggest killing him, my grandfather. The Javelin has a hold on your father’s brother! What do we lack in today’s world? Are sickness, old age, and pain not enough? Is debris, shaking ground, rushing water, and hail insufficient? Is drought and strong wind not enough? Are predators and killer horns not enough? Are we not left broken and blind? Losing teeth, gaining white hair, weak bones, and sagging limbs? Is it not enough that night and day sleep are lost, limiting our short lives?43Bahrām Bayzā’ī, Siyāvash-Khvānī (Tehran: Rawshangarān, 1996), p14.

- 3- Kīmiyā’ī and the poet-like Lutis

Mas‛ūd Kīmiyā’ī’s narratives demonstrate the poetic processing of words and spoken language in Iranian films. His depiction of lower-class protagonists highlights their connections to crime and street culture. Alongside themes of love and betrayal, Kīmiyā’ī’s films critique traditional Iranian values rooted in prejudice, honor, and male loyalty. The lute’s masculine discourse connects to the growing consumer economy and Iran’s relationship with the West during this period.44Hamid Reza Sadr, Iranian Cinema: A Political History (London: I.B. Tauris Publishers, 2006), pp 111-114.

From the 1960s to the 1990s, Kīmiyā’ī’s films centered on male protagonists struggling against societal norms. These characters rise up and seek revenge for their violated rights and often resort to violence. Despite coming from lower-middle-class backgrounds with limited education, they convey depth through pseudo-poetic language and spaces of solitude. Often depicted as poets, they reflect Iranian men over the past fifty years. Throughout his career, Kīmiyā’ī focused on marginalized male voices, highlighting their loyalty—whether as thieves or brave men—and expressing humanity and self-sacrifice.

The Deer (Gavazn-hā, 1974) exemplifies the challenges in Iranian society. An educated man, seeking to help others, becomes involved in political conflict against the ruling power and ultimately resorts to theft. His childhood friend, now addicted and poor, supports him out of loyalty. Ultimately, he suffers because of his friend’s ideals, all for the sake of friendship.

Figure 11: A still from the film The Deer (Gavazn’hā), directed by Mas‛ūd Kīmiyā’ī, 1974.

Sayyid’s speech in the film, performed brilliantly by Bihrūz Vusūqī, reflects these values:

Sayyid: When you left, I did not know who was going. Now, I see who has returned. You remain quiet, still astonished, but love glimmers in your eyes like a dove on my shoulder. I cherish you; you are like a flower that brings me joy.

Sayyid: My misery was my right. If not for this woman, I would have killed myself ten times during a hangover. What do you think? I embraced life. Have I lost my mind? No, I know my challenges. Sadness overwhelms me. My grief differs from yours. It is all about begging. Curse the hangover from begging. When I cry, I know I am alive. […] Theft is theft, even by clerics. They say we are not in a good mood! Has anyone taught us about goodness, and we did not understand? […] My life is begging; curse this hangover. […] We survived until we were shot. […] Better to die from a bullet than in an alley under the bridge.45Mas‛ūd Kīmiyā’ī, dir. The Deers (1974), 00:17:25-00:18:36

The film’s hero merges street language with his experiences, creating a strong emotional bond. His empathy towards disadvantaged communities softens their rhetoric. Qaysar (1969) stresses the presence of humanity despite anger within families, portraying a society filled with oppression and corruption:

This is our time, dear uncle. If you do not hit them, they will hit you. What did you think, Mom? Does anyone care when we die? No, let the sun set three times… Everyone will forget who we were and why we died, just as we forget others. In this era, no one has patience for others’ stories.46Mas‛ūd Kīmiyā’ī, dir. Qaysar (1969), 00;13;26-00:15:17

Figure 12: A still from the film Qaysar, directed by Mas‛ūd Kīmiyā’ī, 1969.

Kīmiyā’ī’s heroes thus employ a poetic style of language to illustrate a unique class of individuals.

Poetic Content and Storyline

In Iranian poetry and folk tales, love stories are central. This reflects the collective spirit of Iranians, shaped by mystical teachings and Oriental romanticism. Themes of longing for reunion and the pain of separation are prevalent in both written and oral narratives. From the 1960s to the 1990s, Iranian cinema crafted diverse narratives centered on profound love and the impacts of secret romances. Poetry often influences these love stories, typically featuring love triangles among family or friends. Many documentary-style tales from this era highlight heroes’ failures and tragic endings.

Unlike Persian cinema, which mirrors Bollywood patterns with happy endings, Iranian films often depict emotionally painful endings and unwanted separations of lovers. Many poetic Iranian films focus on romance but depict unexpected deaths or deep sorrow. Themes of failed affection, delayed love confessions, murder, and envy shape the narratives. Typically, lovers do not reunite or do so too late. The romantic themes in Iranian new-wave cinema center on tragic heroes and have a nostalgic tone. They are often influenced by a historical perspective that illustrates a struggle to attain truth due to Islamic mysticism, which contributes sadness and social injustice to the romance.

In Brick and Mirror (Khisht u Āyinah, 1964), Gulistān highlights the futility of fulfilling social responsibilities amidst widespread suffering through a recurring narrative pattern. The film, styled like a neorealistic documentary, tells the story of a taxi driver who unwittingly brings an unexpected passenger into his life. A young woman enters the taxi and leaves her baby behind, hoping to provide it with a better destiny. Reluctant to accept emotional responsibility, the driver resolves to leave the baby at an orphanage, while his girlfriend wishes to keep it to strengthen their relationship.

Figure 13: A still from the film Brick and Mirror (Khisht u Āyinah), directed by Ibrāhīm Gulistān, 1964.

Gulistān presents a naturalistic view of poverty, illustrating his hero’s struggles with decision-making and his passivity. The film ends with the driver watching a veiled woman, likely with a child, enter another taxi, reflecting a semi-open narration in Iranian cinema. While portraying the harsh realities of 1960s Iran, the film prompts audiences to reflect and seek solutions. The filmmaker enhances the plot by emphasizing the central incident and imbuing the cinematic content with poetic expression.

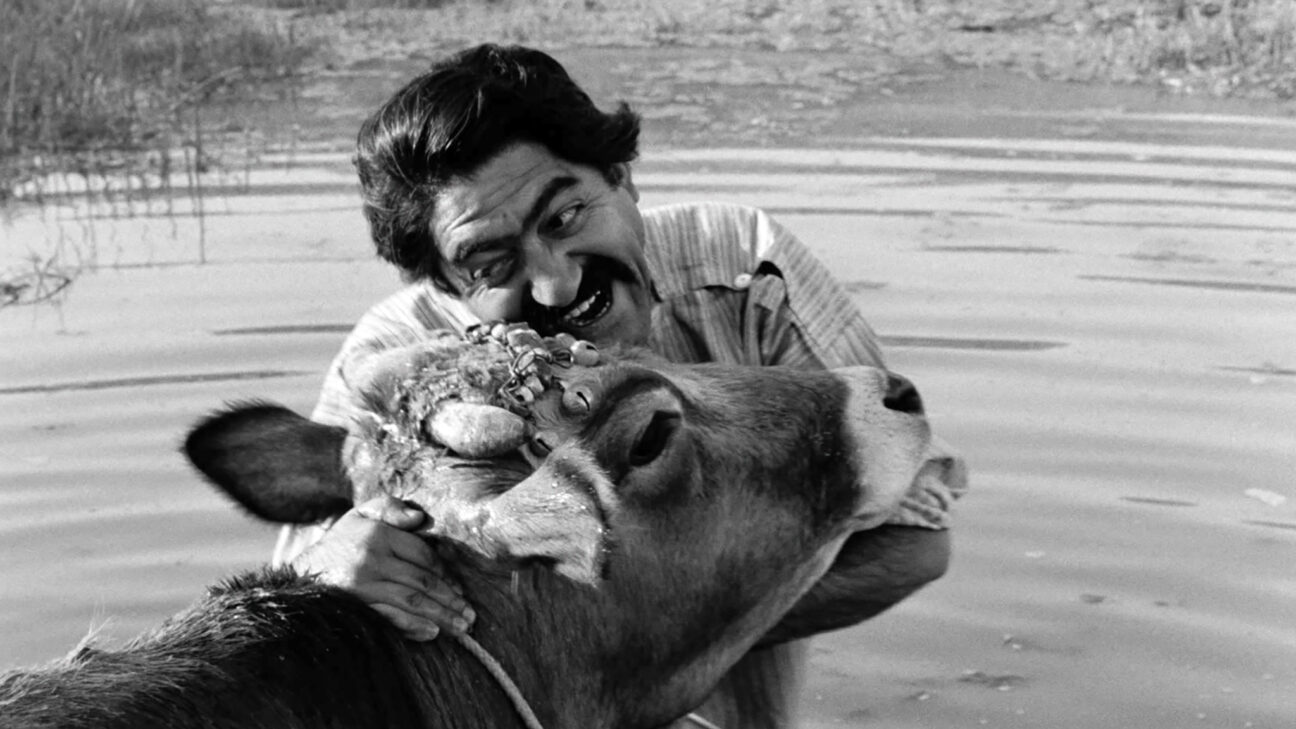

Some of the essential Iranian screenplays based on love triangles, tension, unity, and the lover’s sacrifice for the beloved can be found in the films Come Stranger (Bīganah Biyā, Kīmiyā’ī, 1964), The Cow (Gāv, Mihrjū’ī, 1968), Tawqī (Hātamī, 1970), and Dāsh Ākul (Kīmiyā’ī, 1971). These films portray dramatic intensity and vulnerability. The transformation of the lover into the beloved, as a process of destruction in the object of affection, can be considered a kind of poetic treatment of the story’s content, which is perhaps most evident in The Cow (1969). The film’s hero becomes so attached to his cow that he does not accept its absence. The cow plays existential role in his rural life to guide him from madness to illness, neurosis, and finally, death.

Beyond the visuals, strong performances, and notable mise-en-scène, the storyline is engaging and reflects the poetic spirit of Iranians. The cow exemplifies semantic slippage through Mash Hasan, where new meanings replace original ones. This presents an innovative twist on allegorical personification, reversing anthropomorphism. Personification here conveys abstract concepts through human figures, while anthropomorphism gives human traits to non-human entities.47Michelle Langford, Allegory in Iranian Cinema: The Aesthetics of Poetry and Resistance (London and New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2019), 33.

Figure 14: A still from the film The Cow (Gāv), directed by Dāryūsh Mihrjū’ī, 1968.

Tawqī and Dāsh Ākul gently depict a man’s love for a teenage girl, exploring complex family dynamics. Their relationship, between uncle and niece, reveals emotional ups and downs. The complex affection culminates in a painful conclusion that emphasizes morality. Hātamī’s Sūtah-Dilān exemplifies the challenges of expressing love in a society bound by shame and ethics, where the protagonist’s confession meets the harshness of fate. This poetic exploration of human relationships, emotional turmoil, and tragic endings creates an intense atmosphere that places characters in complex, often impossible, situations.

Figure 15: A still from the film Dāsh Ākul, directed by Mas‛ūd Kīmiyā’ī, 1971.

Cine-Poetic Images

Poetic cinema, and many experimental Iranian filmmakers, make unique use of image language. However, the desire to express facts visually and tell stories that resonate with audiences on this level has dimmed. Films exploring these themes are often labeled intellectual and considered a distinct and sometimes challenging art form. However, there remains a strong desire among filmmakers to express unique image arrangement and poetic composition.48Its example can be seen in the style of filmmaking and the poetic language of unique images and camera movements, which compose cinematic poems, as seen in the works of Terrence Malick. In a paper published in Iran Nameh’s film issue (2008), director Bahram Bayzā’ī claims that a century of cinema in Iran proves that “the image” is now “the language of the people.”49Negar Mottahedeh, Displaced Allegories: Post-Revolutionary Iranian Cinema (London and New York: Duke University Press, 2008), 42.

Before the revolution, Iranian cinema was seen in Suhrāb Shahīd-Sālis’s film Still Life (Tabī‛at-i Bījān, 1974), which is marked by long shots depicting cold faces and strained family relations. It depicts exhausting survival instincts against plain backgrounds such as bare walls and railways.

Figure 16: A still from the film Still Life (Tabī‛at-i Bījān), directed by Suhrāb Shahīd-Sālis, 1974.

The city’s bleak atmosphere reflects the elderly protagonist’s impending retirement, beautifully framing existence’s challenges with slow rhythms and dull expressions, revealing a poetic beauty in life’s ugliness. In Still Life, poetry transcends traditional storytelling, subtly hinted by its plot, which emerges through visual elements intrinsic to Iranian film poetry. Parvīz Kīmiyāvī’s film Mongols (Mughul-hā, 1973) explores collective memory through minimalistic symbols. Conceptual images represent pure cinematic art, transforming subjects into thoughtful concepts. They invite audiences to uncover hidden truths in a world of illusions and dreams. These images engage the mind with cinematic language beyond the conventional storytelling.

Figure 17: A still from the film Mongols (Mughul-hā), directed by Parvīz Kīmiyāvī, 1973.

Amīr Nādirī (b. 1946) was the first post-revolution Iranian filmmaker to create cinematic poems, sparking Western interest in Iranian cinema. His notable films, The Runner (Davandah, 1984) and Water, Wind, and Dust (Āb, bād, khāk, 1985), simplify narratives to depict longing and the complexities of life in Iran. The Runner follows teenage Amīru, who dreams of traveling across the Persian Gulf while collecting and selling bottles and shining shoes for a living in Abadan, attending night classes to learn the alphabet.

Figure 18: A still from the film The Runner (Davandah), directed by Amīr Nādirī, 1984.

This storyline forms the foundation of a poetic narrative that transcends time while emphasizing the importance of learning and self-improvement. Instead of cause-and-effect logic, The Runner uses a unique arrangement of small narrative fragments that visually depict the struggle for survival, awareness, and respect. The film features stunning shots, especially during the climactic ice race, contrasting flames from oil rigs in southern Iran with the reward of ice, which symbolizes a teenage quest for knowledge. These elements secure The Runner’s unique place in Iranian cinema; the film continues to be celebrated for its poetic imagery.

Water, Wind, and Dust is about a teenage hero battling a land overtaken by dust. This mythic struggle aims to preserve national identity. The film uses visuals and metaphors to highlight human resilience against nature. Powerful final scenes show water erupting from the Iranian desert—where survival seems impossible—and, combined with Beethoven’s fifth symphony, create a lyrical exploration of the eternal struggle among these elements of existence.

Figure 19: A still from the film Water, Wind, and Dust (Āb, bād, khāk), directed by Amīr Nādirī, 1985.

Personal Style in Cine Poetry

‛Abbās Kiyārustamī’s unique style is evident in an early scene in Close Up (1989), when a reporter and soldiers enter a house to arrest Husayn Sabziyān, who falsely claims to be the filmmaker Makhmalbāf. Rather than focusing on Sabziyān’s arrest, Kiyārustamī highlights the taxi driver, who is sitting outside and smoking. He depicts the driver waiting for the reporter while soldiers prepare for the arrest, as Sabziyān wanders nearby. The driver sees autumn leaves and attempts to take a branch of dried flowers, placing it on the taxi’s dashboard. A spray paint can unexpectedly slip, rolling under his feet and down the alley until it comes to a stop near a stream. This subplot, which may initially seem insignificant, unfolds humorously until the group accompanies Sabziyān to the police station.

Figure 20: A still from the film Close Up, directed by ‛Abbās Kiyārustamī, 1990.

Husayn Sabziyān’s arrest unfolds through the Āhankhāh family’s legal proceedings. The filmmaker uses narrative pauses to evoke tenderness, creating a media frenzy around an unemployed individual, all set amid larger social conflicts. Kiyārustamī’s style merges violence and delicacy, complicating moral judgments on civil rights and goodwill. Thus, Close-up prompts viewers to confront the challenges of judgment and humanity amidst dreams, regrets, and the harsh realities of life.

Under the Olive Trees (Zīr-i Dirakhtān-i Zaytūn, 1994) depicts subtle satire within a romantic story. In the final scene, the male protagonist gazes at olive trees, searching for his distant lover. Their conversation flows with the wind rustling the branches, yet the audience is oblivious to the words. The young man’s excitement and uplifting music evoke a sense of freedom and longing. This approach introduces a lyrical element to the film, similar to Close-up where the conversation between Makhmalbāf and Sabziyān is interrupted. They are to visit Āhankhāh’s family to seek forgiveness. Cutting off their voices creates a distancing effect that encourages viewers to reconstruct the conversation, filling gaps in the film’s soundtrack with their interpretations. This method was frequently used in Kiyārustamī’s films, such as Life and Nothing More… (Zindagī va dīgar hīch, 1992), Taste of Cherry (Ta‘m-i gīlās, 1997), and The Wind Will Carry Us (Bād mā-rā khvāhad burd, 1999).

Figure 21: A still from the film Under the Olive Trees (Zīr-i Dirakhtān-i Zaytūn), directed by ‛Abbās Kiyārustamī, 1994.

Poetic sub-narratives

After the 1970s, world cinema embraced new narrative patterns influenced by postmodern literature. Filmmakers explored innovative storytelling, moving from traditional plots and cause-and-effect logic to unstable, anti-plot experiences. Hero-centered characterization dissolved, giving way to intersecting sub-narratives. Filmmakers combined narrative layers and negative spaces—such as off-screen voices—to create ambiguity. Many films from this era are deliberately incomplete, inviting viewers to construct their own narratives. The main storyline often fragments, with sub-narratives woven into the structure.

Kiyārustamī’s continued prominence, even posthumously, is due to personal, historical, and institutional factors. His biography highlights the evolution of Iranian cinema’s quest for modernity, authenticity, and identity. His unique style influences art cinema. In the 1990s, he showcased Iranian cinema globally by entering Art-House Cinema 179 festival circuits. No Iranian filmmaker gained more acclaim in the West than Kiyārustamī, whose image graced the July-August 1995 issue of Cahiers du Cinema with the caption “Kiarostami le Magnifique.”50Hamid Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema. Vol. 4: The Globalization Era, 1984-2010 (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2012), 178-179.

The Wind Will Carry Us (1999) is a complex narrative by Kiyārustamī that poetically explores life and death. The film documents a filmmaking team’s efforts to portray the end of life of an elderly woman with cinematic objectivity. It intertwines real and fictional elements, showcasing young love and the struggle against death, intensified by a devastating earthquake in northern Iran—a recurring theme in Kiyārustamī’s work.

Figure 22: A still from the film The Wind Will Carry Us (Bād mā-rā khvāhad burd), directed by ‛Abbās Kiyārustamī, 1999.

The plot of The Wind Will Carry Us follows Bihzād, Kayvān, ‛Alī, and Jahān, who are part of a filmmaking group documenting a mourning ceremony in Tehran. Working for a certain Ms. Gūdarzī, they travel to Kurdish villages, waiting for the death of an old woman to film for their project. The villagers think they seek treasure, and Bihzād stays silent. He climbs rooftops to visit the older woman and often talks on his mobile from the cemetery on a nearby hill, where a young man is digging. As his companions grow weary and depart, the pit collapses, injuring the digger and resulting in the woman’s death. Bihzād returns to Tehran after witnessing the villagers’ despair. Before leaving, he throws a bone he found in the cemetery into the water, revealing that another Bihzād, a young man from the city, died in that village, which offers fresh insights on life death.

Kiyārustamī opens the film with a straightforward narrative. He gradually enriches the plot’s secondary elements, shifting attention from the documentary team’s mission to more profound themes. Through repetitive actions, like trips to the cemetery for phone calls, he weaves narratives about heaven and hell, life and death, via the village teacher’s dialogue. This focus on off-screen dialogue transforms the film, positioning these subtler themes as the core storyline.

The film’s narrative reveals a sub-story of emotional ties between a village gravedigger and a girl, highlighted by Furūgh Farrukhzād’s romantic poetry that connects to feelings to death. The title evokes modern Iranian poetry, specifically Suhrāb Sipihrī’s Where Is the Friend’s House? (Khānah-yi dūst kujāst? 1987). The filmmaker explores love poetically, contrasting the cemetery’s light with the grave’s darkness. Their bond is expressed through song, as the gravedigger notices the food the girl leaves next to her digging site. Their tender relationship, both searching for love and a future, starkly contrasts the themes of death and mourning in the main storyline. This contrast mirrors the metaphors in Farrukhzād’s poem Another Birth (1950), which reflects, The Wind Will Carry Us:

Just a moment

And nothing then

Behind this window,

The night is shaking

And the earth

Stops rotating

Behind this window,

There is an unknown person who is worried about you and me.

O, You! You, all the green!

Like a burning memory, put your hands in my hands

Moreover, leave your lips to the caresses of my loving lips, like a warm feeling of existence.

The wind will carry us.

The wind will carry us.51Furūgh Farrukhzād, Tavallodi dīgar (Another Birth) (Tehran, 1950), pp 31-32.

Kiyārustamī depicts life and death’s complexities through layered narratives, capturing nuances beyond mere words.

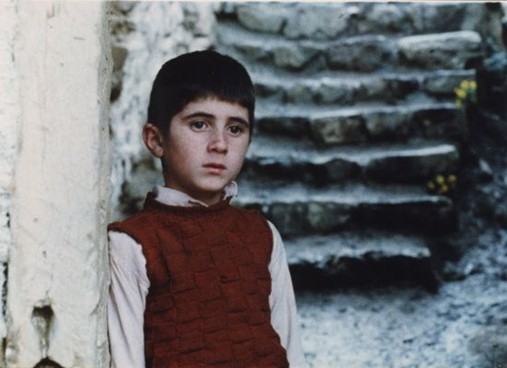

Figure 23: A still from the film Where Is the Friend’s House? (Khānah-yi dūst kujāst?), directed by ‛Abbās Kiyārustamī, 1987.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this article presents a compilation of evidence and poetic influences that highlight the significance of discussing Iranian poetic cinema. Understanding Iranian cinema’s conceptual and expressive complexities is crucial for fully appreciating it, particularly given its reliance on specific cinematic techniques. The evolution of the poetic film concept in contemporary world cinema has provided Iranian filmmakers with innovative techniques, both before and after the Islamic Revolution, enabling them to effectively express the unique characteristics and poetic narratives of Iranians through their cinematic works.

Cite this article

This article examines the evolution of Poetic Cinema as a film language that conveys meaning through lyrical and artistic expression—melding literary rhythm and dialogue with visual techniques such as mise-en-scène, lighting, and camera movement. Originating in post–World War II European cinema, the concept has since expanded across forms including poetry films, video poems, and screen poetry. The study outlines three phases of Poetic Cinema’s development—formation, conceptual maturity, and genre diversification—while identifying four modes of poetic representation in film: verbal, visual, emotional, and perceptual.

Focusing on Iranian cinema, the article traces the influence of modern poetic movements and classical Persian literature on cinematic style, especially during the New Wave period. It argues that Iranian filmmakers have long integrated poetic devices—metaphor, allegory, irony—into narrative and visual form. Key works by Sohrab Shaheed-Salles, Ali Hatami, Dariush Mehrjui, Masoud Kimiai, Bahram Beyzaei, and Abbas Kiarostami are analyzed as foundational expressions of Poetic Cinema in Iran