Mahdī Ivanov (Rūsī Khan): The Enigmatic Pioneer of Iranian Cinema

Mahdī (Rūsī Khan) Ivanov was born in Tehran on 15 October 1875 of Russian Tatar and British parentage, although historians have provided contradictory accounts of his parents’ nationality.1Some scholars have claimed that his father was Russian Tatar and his mother was British, while others have asserted the opposite. Hamid Naficy has attended to his disputed genealogy in A Social History of Iranian Cinema: The Artisanal Era, 1897-1941 (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011), 63. Yahyā Zukāʾ has also cast doubt on his first name, Mahdī, claiming that fellow historian Farrukh Ghaffārī had wrongly attributed it to him with others in turn following Ghaffārī’s example.2Zukāʾ has suggested that Ghaffārī had mistakenly attributed to Ivanov the first name of Ivanov’s photography studio partner, Mahdī Mirza Musavvar al-Mulk. See Zukāʾ, Tārīkh-i ʿakkāsī va ʿakkāsān-i pīshgām dar Īrān (Tehran: Shirkat-i Intishārāt-i ʿIlmī va Farhangī, 1997), 146. Iranian cinephiles have, in any case, best remembered Ivanov by the laqab or title that Muhammad ʿAlī Shah Qājār (r. 1907-1909) had given him, presumably in reference to his familial and social ties to Russia: Rusī Khan.3Sayyid Kāzim Mūsavī, Farīdūn Jayrānī, and Farrukh Ghaffārī, Asnādī barā-yi tārīkh-i sīnimā-yi Īrān: Guftigū bā Farrukh Ghaffārī, ed. Saʿid Mustaqasi (Tehran: Āgāh Sāzān, 2009), 80n12. Ivanov stamped this title on the back of his photographs. See Zukā’, Tārīkh-i ʿakkāsī va ʿakkāsān-i pīshgām dar Īrān, 146.

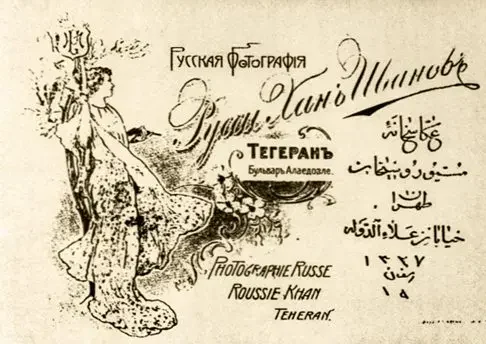

Figure 1: Portrait of Mahdī Ivanov (Rūsī Khan)

Like cinema pioneers Mirza Ibrāhīm Sahhāfbāshī Tihrānī (1858-1921 or 2) and Mirza Ibrāhīm Rahmānī ʿAkkāsbāshī (1874-1915), Ivanov first came to film-making and exhibition via photography. Their knowledge of this earlier and closely associated technology was itself a product of their connections to Qājār court personalities or institutions like the government-run Dār al-Funūn (‘House of Arts and Sciences’) polytechnic. Photography in Iran at the turn of the century had retained strong associations with the Qājār elite. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the royal court would also play a pivotal role in cinema’s arrival and cultivation. There was little in the way of an indigenous middle class that could support a domestic film industry or exhibition infrastructure of any scale. Consequently, early cinema and cinema-going was the nearly exclusive preserve of the Qajar aristocracy and foreign expatriates. Muzaffar al-Dīn Shah (r. 1897-1907) had ordered ʿAkkāsbāshī as his court photographer to purchase a Gaumont motion picture camera during his first trip to Europe in 1900.4Farrokh Ghaffary, “Cinema, i. History of Cinema in Persia,” Encyclopedia Iranica, https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/cinema-i Sahhāfbāshī Tihrānī had likewise received the Shah’s permission to import a film projector from France and, in May 1897, he hosted the first public screenings in the courtyard of his antique shop on Tehran’s Lālihzār Street before opening Iran’s first cinema hall on Chirāgh Gāz (now Amīr Kabīr) Street a few years later in November 1904.5Farrokh Gaffary, “Coup d’œil sur les 35 premières années du cinema en Iran,” in Entre l’Iran et l’Occident: adaptation et assimilation des idées et techniques occidentales en Iran, ed. Yann Richard (Paris: Fondation de la Maison des sciences de l’homme, 1989), 227. Chahryar Adle has disputed this opening date and argued that Sahhāfbāshī Tihrānī’s cinema could have opened no earlier than 1905 and no later than 1908. See Chahryar Adle, “Acquaintance with Cinema and the First Steps of Filming and Filmmaking in Iran,” trans. Claude Karbassi, Tavoos Quarterly 5 & 6 (Autumn 2000-Winter 2001): 184. Sahhāfbāshī Tihrānī’s cinema remained open for only a month, with historians variously attributing the closing to clerical objections to cinema-going (notably Shaykh Fazl-Allāh Nūrī’s famous edict against the cinema), the court’s heavy-handed reaction to Sahhāfbāshī Tihrānī’s support for the constitutionalist movement, as well as more mundane economic troubles.6Jamāl Umīd invokes all three reasons for Sahhāfbāshī’s failure in Tārīkh-i sīnimā-yi Īrān, 1279-1357 (Tehran: Intishārāt-i Rawzanah, 1998), 23. However, Tehran did not remain without a cinema hall for long, with court allies like Ivanov stepping into the fray. Historians have even speculated that Ivanov may have concluded from Sahhāfbāshī Tihrānī’s ill-fated venture that the only way to succeed in the film exhibition business at this time was to cultivate the royal court’s favor.7See, for example, ʿAbbās Bahārlū, Sad chihrih-ʾi sīnimā-yi Īrān (Tehran: Nashr-i Qatrah, 2002), 13.

Ivanov had as a youth become an apprentice to ʿAbd-Allāh Mirza Qājār (1850-1908 or 9), a cousin (once removed) of Nāsir al-Dīn Shah (r. 1848-1896), who served the monarch and his successor Muzaffar al-Dīn Shah in a variety of capacities but mainly as a photographer.8Zukāʾ, Tārīkh-i ʿakkāsī va ʿakkāsān-i pīshgām dar Īrān, 146. Ivanov eventually graduated from darkroom technician to become a court photographer. In early January 1907, Muhammad ʿAlī Shah ascended to the throne and, under the protection of the Cossack Brigade and Russia, sought to undo the recently ratified constitution and re-assert monarchical power. When ʿAbd-Allāh Mirza received the title of ʿAkkāsbāshī from Muhammad ʿAlī Shah, Ivanov soon thereafter struck out on his own and opened a photography studio on Tehran’s ʿAlāʾ al-Dawlah (subsequently Firdawsī) Street.9Umīd has provided an opening date of after the Persian New Year in March 1907 in Tārīkh-i sīnimā-yi Īrān, 1279-1357, 25. Concurrently, and presumably with court approval, he began dabbling in film exhibition. At a ceremony that winter in honor of the crown prince Ahmad Mirza, two unknown Russians had held a two-hour screening of two films (most likely a concatenated series of silent shorts) with gramophone accompaniment at Tehran’s Gulistān Palace.10Umīd, Tārīkh-i sīnimā-yi Īrān, 1279-1357, 25. Naficy has written that Ivanov and Mirza Mahdī Khan Musavvar al-Mulk, also a court photographer and artist, were responsible for the screening held in honor of the crown prince at Gulistān Palace. See Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema: The Artisanal Era, 64; However, the source (Yahyā Zukāʾ) that Naficy has cited for his information does not appear to endorse this claim. The audience gave the screening an enthusiastic reception which inspired Ivanov to purchase a Pathé projector and 15 reels of second-hand films—a mix of comic shorts, actualities, travelogues, and newsreels.11Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema: The Artisanal Era, 65. Historians have disagreed about where Ivanov sourced his equipment and reels from, with Ghaffārī claiming Paris and Adle speculating that Russian ports like Odessa and Rostov were more likely points of origin given Ivanov’s connections to Russia.12Adle has detailed his disagreement with Ghaffārī in “Acquaintance with Cinema and the First Steps of Filming and Filmmaking in Iran,” 184.

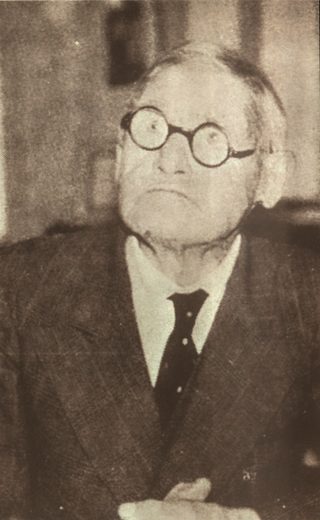

Figure 2: Rūsī Khan photography studio

These early film reels were likely French productions and Zukāʾ has even identified some of them as Pathé comedies starring Max Linder and Charles Prince (Rigadin).13Zukāʾ, Tārīkh-i ʿakkāsī va ʿakkāsān-i pīshgām dar Īrān, 150. However, Ivanov could well have purchased them second-hand from Russian dealers. In fact, Humā Jāvdānī has reported that Ivanov made multiple trips to Russia during his three-year career as a cinema hall operator, returning with a trunk-full of film reels from at least one of them.14Jāvdānī, Sālshumār-i tārīkh-i sīnimā-yi Īrān: Tīr 1279-Shahrīvar 1379 (Tehran: Nashr-i Qatrah, 2002), 19. By February 1907, Ivanov was screening films for the palace household and then in the homes of Tehran’s elite.15Umīd, Tārīkh-i sīnimā-yi Īrān, 1279-1357, 25. Naficy has speculated that these kinds of private screenings at high society events also included gramophone accompaniment. See Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema: The Artisanal Era, 49. Ivanov’s ‘traveling show’ also included a cinematic precursor: the magic lantern, shahr-i farang in Persian, where guests could watch slides of world landmarks, everyday scenes, and fictional narratives through a peep hole.16Umīd, Tārīkh-i sīnimā-yi Īrān, 1279-1357, 36n34. This mixed media program may well have been in imitation of Sahhāfbāshī Tihrānī’s shows of film shorts and magic lantern color plates at his defunct theater.17Adle, “Acquaintance with Cinema and the First Steps of Filming and Filmmaking in Iran,” 187.

Spurred by the success of these private showings, Ivanov purchased additional projection equipment and began in October 1907 (coinciding with the Islamic lunar month of Ramadan) to hold public film screenings every Monday and Friday night at his photography studio.18Bahārlū, Sad chihrih-ʾi sīnimā-yi Īrān, 13. The studio was in an area housing several European diplomatic missions, Qājār nobility, and wealthy merchants and his neighbors came to comprise the bulk of Ivanov’s audience. It was not long before he rented the courtyard next to his studio and installed benches there for screenings, with seating for two hundred (male) patrons.19Scholars have differed on the location of Ivanov’s first public screenings. Ghaffārī has written that the courtyard next to his studio was where he hosted his first audiences in October 1907. See Gaffary, “Coup d’œil sur les 35 premières années du cinema en Iran,” 228; Ghaffārī elsewhere and earlier has also claimed that Ivanov did not have any public film showings until 1908. See Gaffary, Le cinèma en Iran (Tehran: Le conseil superieur de la Culture et des Arts, Centre d’études et de la coordination Culturelles, 1973), 3; However, Umīd has provided evidence of two advertisements in the Habl al-matīn newspaper from October and November 1907, in which Ivanov invited readers to attend screenings in his studio. See Umīd, Tārīkh-i sīnimā-yi Īrān, 1279-1357, 25.

The hour-long courtyard screenings were held nightly. Ivanov also advertised the acquisition of new films, including a Russian propaganda reel on the Russo-Japanese war (1904-5), which Bahārlū has reported had the subtitle “Long Live Russia!”20Bahārlū, Sad chihrah-ʾi sīnimā-yi Īrān, 14. Scholars have argued that Ivanov favored (or came to favor) Russian or pro-Russian films in his cinema programming, with this documentary short presented as prime evidence. His Russian Tatar background and close relationship with Colonel Vladimir Liakhov, Russian commander of the Shah’s Cossack Brigade and frequent patron of his screenings, have also figured into discussions of Ivanov’s preference for Russian fare.21E.g., Gīsū Faghfūrī, Sarguzasht-i sīnimā dar Īrān (Tehran: Nashr-i Ufuq, 2012), 20. However, a lack of Russian productions at the time would have severely limited Ivanov’s ability to put together such a program even if, as scholars have argued, it was his intention. According to Naficy, Ivanov was the first cinema operator to give titles to his film programs in newspaper advertisements.22Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema: The Artisanal Era, 64-65. Bahārlū has even provided some of the program titles but they give the reader no hint of the films’ country or countries of origin.23Bahārlū, Sad chihrih-ʾi sīnimā-yi Īrān, 14. It is likely that Ivanov continued to buy the same kinds of films with which he had already enjoyed success and were plentiful in the resale market—French comedies, newsreels, and documentary shorts. His screening of the Russian propaganda reel could even be explained by his need to shepherd his fledgling business through (or, to put it less charitably, take advantage of) the turbulent politics of the time: the period of the ‘lesser tyranny’ (istibdād-i saghīr), in which the monarch was seeking to overturn the gains of the constitutionalists with Russian backing. In fact, Bahārlū has written that fellow cinema hall owner and Ivanov’s bitter rival, the Caucasian émigré Āqāyuf, had also shown at this time the same pro-Russian film to his Cossack and royalist patrons.24Bahārlū, Sad chihrih-ʾi sīnimā-yi Īrān, 14

Figure 3: Excursion en aéroplan (Travel by plane).

According to Umīd, Ivanov’s competition with Āqāyuf would encourage him during the first half of 1908 to convert the courtyard of Dār al-Funūn’s assembly hall into an open-air cinema. He installed a canopy and benches with space for 150 to 200 people.25Umīd, Tārīkh-i sīnimā-yi Īrān, 1279-1357, 25-6. Umīd has written that Ivanov traveled to Russia in the summer of 1908 after establishing the Dār al-Funūn cinema. Thus, it can be surmised that he carried out the courtyard conversion during the first half of the year. Undoubtedly his close relations with the court and Liakhov smoothed the way for the expansion of his cinema business. Naficy has written that Liakhov even saved Ivanov from paying taxes as well as from police punishment for “other transgressions.”26Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema: The Artisanal Era, 66. When the rivalry between Ivanov and Āqāyuf turned violent, Ivanov called on Liakhov to arrest and imprison Āqāyuf in the Russian embassy. Ironically, Āqāyuf’s counter-complaint briefly landed Ivanov in the same prison!27Umīd, Tārīkh-i sīnimā-yi Īrān, 1279-1357, 26. Despite this hiccup, Ivanov’s business prospects continued to improve. In the second half of 1908, in an unlikely partnership with radical constitutionalist Haydar ‛Amū Uqlī, he rented out the second floor of the Fārūs publishing house on Lālihzār street and converted it into a cinema hall with seating for as many as 600 patrons.28Nasir Habībīyān and Mahyā ‛Āqā Husaynī, Tamāshākhānah-hā-yi Tihrān: Az 1247 tā 1389 (Tehran: Intishārāt-i Afrāz, 2011), 67. According to Naficy, Ivanov introduced a number of film exhibition practices in Iran that outlived his career as a cinema hall operator. Fierce competition with Āqāyuf for a limited customer base likely fueled these innovations.29Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema: The Artisanal Era, 64-5. As previously mentioned, he was the first to place newspaper advertisements with descriptions of his nightly programs, which he changed regularly. Screenings included musical accompaniment, both live and recorded.30Jāvdānī has written that Ivanov hired a pianist and violinist to perform during film showings at the Dar al-Funun cinema. See Humā Jāvdānī, Salshumār-i tārīkh-i sīnimā-yi Īrān: Tīr 1279-Shahrīvar 1379, 19. He would ultimately make musical accompaniment a standard feature in all of his cinema programs. See Umīd, Tārīkh-i sīnimā-yi Īrān, 1279-1357, 25. One film historian has suggested that Ivanov was also the first cinema operator to employ what came to be known as a dilmaj, or screen translator, to aid audiences’ comprehension of his films.31Faghfūrī, Sarguzasht-i sīnimā dar Īrān, 20 He equipped his Fārūs theater, which opened in October or November 1908, with arc light projection, a power generator, fan, and a restaurant-bar where his high-powered patrons, including British and Russian diplomats and members of the Cossack Brigade, supposedly drank alcoholic beverages well into the night.32Umīd, Tārīkh-i sīnimā-yi Īrān, 1279-1357, 26 and 37n41. However, he also came to offer discounted tickets to students,33Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema: The Artisanal Era, 65. perhaps betraying his longer-term understanding of cinema-going as a leisure activity for the masses and especially the youth.

In line with a long-term vision of the cinema as a popular art form, Ivanov also sought to overcome the objections of religious authorities to the medium according to film scholars. After disassociating himself from the Dār al-Funūn cinema in late 1908, he opened a new theater near Darvāzah Qazvin in Tehran’s popular Sangalaj neighborhood. In an interview with Ghaffārī during his final years, Ivanov claimed that he invited Sahhāfbāshī Tihrānī’s one-time bête noire Shaykh Fazl-Allāh Nūrī there to attend a screening, to which the cleric agreed and ultimately ruled the cinema to be permissible.34Gaffary, Le cinèma en Iran, 4. Naficy has written more circumspectly about Nūrī’s reaction. See Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema: The Artisanal Era, 66; Film scholar Muhammad Tahāmī Nizhād has claimed, based on his reading of Ghaffārī’s interview, that Ivanov even accused Nuri of seeking to extort money from him in exchange for his cooperation in advancing the public’s acceptance of the cinema and cinema-going. Adle has referenced Tahāmī Nizhād’s conjecture in “Acquaintance with Cinema and the First Steps of Filming and Filmmaking in Iran,” 210n41. Such examples of friendly engagement with potential political and religious enemies (unlike Ivanov’s treatment of professional rivals) would seem to bring into question an oft-repeated anecdote about armed constitutionalists forcibly taking over his Fārūs cinema to watch and discuss films,35See, for example, Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema: The Artisanal Era, 66. especially when considering the fact that one such radical revolutionary (‛Amū Uqlī) was his business partner there. Indeed, Ghaffārī has written that radical mujahidin militants fighting for the constitution, in the wake of their victory in 1909, became regular attendees at his Fārūs theater.36Gaffary, Le cinèma en Iran, 4. Whatever feelings he may have had for his patrons, Ivanov (knowingly or unknowingly) had taken important steps towards democratizing the cinema.

Figure 4: Fārūs publishing house on Lālihzār street

After constitutionalists on 16 July 1909 deposed Muhammad ʿAlī Shah, who took temporary refuge in the Russian embassy, Ivanov closed his Darvāzah Qazvin cinema.37Bahārlū, Sad chihrah-ʾi sīnimā-yi Īrān, 14. Umīd has written that he made some changes to his Fārūs theater at this time but does not provide specifics. See Umīd, Tārīkh-i sīnimā-yi Īrān, 1279-1357, 26). Historians have speculated that his close relationship with the Qājār royal household, whose future was very much in question with the eleven-year-old Ahmad (r. 1909-25) now ascending to the throne, had prompted Ivanov to scale down his cinema business. He had only recently received the title of ʿAkkāsbāshī as the official court photographer and perhaps felt especially vulnerable to constitutionalists’ retribution against court officials and allies.38Bahārlū has written that Ivanov received this title earlier and after Mirza Ibrāhīm Rahmānī ʿAkkāsbāshī. See Bahārlū, Sad chihrih-ʾi sīnimā-yi Īrān, 13; but his dating conflicts with Umīd’s claim of ‛Abd-Allāh Mirza’s appointment as ʿAkkāsbāshī in 1907. See Umīd, Tārīkh-i sīnimā-yi Īrān, 1279-1357, 25; It is more likely that Ivanov received this title only after his mentor’s passing in 1908 or 9. His role as a royal documentarian may have motivated him on 1 February, 1909 to take up a film camera during the Tehran mourning ceremonies for the third Shia Imam, Husayn.39Adle has suggested that Ivanov had intended for the commercial exploitation of the film rather than making it for the private use of the court. See Adle, “Acquaintance with Cinema and the First Steps of Filming and Filmmaking in Iran,” 200; However, his recent appointment as official court photographer and the film’s subject matter, which had previously been the topic of a court-commissioned film, casts some doubt on his conclusion. In doing so, Ivanov became the second person to make films in Iran after Mirza Ibrāhīm Rahmānī ʿAkkāsbāshī, who had also filmed the Tehran Muharram processions in 1901 (and likely with the very camera that Ivanov used eight years later).40Adle, relying on Ghaffārī’s published account of his interviews with Ivanov, has written that Mirza Ibrāhīm Rahmānī ʿAkkāsbāshī had sold his camera to Ivanov after the death of his patron Muzaffar al-Din Shah. See Adle, “Acquaintance with Cinema and the First Steps of Filming and Filmmaking in Iran,” 200; For details on Mirza Ibrāhīm Rahmānī ʿAkkāsbāshī’s 1901 Muharram documentary film, also see Adle, “Acquaintance with Cinema and the First Steps of Filming and Filmmaking in Iran,” 202. The film he shot, roughly 80 meters in length and known to film historians by the title ʿĀshūrā, was sent to Russia to be developed and received a screening there but deteriorating political conditions made any public showing in Iran impossible.41Umīd, Tārīkh-i sīnimā-yi Īrān, 1279-1357, 26. The chaos of the interregnum would ultimately bring an end to Ivanov’s career in film exhibition and film-making. On the same day as Muhammad ‛Alī Shah’s deposal, constitutionalists had looted Ivanov’s ʿAlāʾ al-Dawlah studio, with his photography equipment, photographs, and thousands of meters of films (including the ʿĀshūrā documentary) destroyed or stolen.42While only the existence of Ivanov’s documentary of the Muharram ceremonies has been confirmed, Ghaffārī has claimed that Ivanov revealed in their interviews that there were two thousand meters or more of film reels in the studio (presumably shot by Ivanov) when it was plundered. See Adle, “Acquaintance with Cinema and the First Steps of Filming and Filmmaking in Iran,” 200, 212n125; Zukāʾ has written that Ivanov’s partner Mahdī Musavvar al-Mulk reopened the studio after the looting and continued to operate it through 1910, when illness forced him to close it for good. See Zukāʾ, Tārīkh-i ʿakkāsī va ʿakkāsān-i pīshgām dar Īrān, 150n6. His royal patron’s departure for Odessa in September 1909 likely put Ivanov’s future in Iran on even shakier ground. By early 1910, he had divested himself of the Fārūs cinema, after supposedly growing tired of mujahidin attendees disrupting his programs with their personal disputes. Umīd has written that Mirza Ismā‛īl Qafqāzī (also known as George Ismā‛īluf), a War Ministry (Vizārat-i Jang) employee, took over the Fārūs theater and bought Ivanov’s projector. In 1911, Ivanov cut his remaining links to the cinema business by selling a second projector and 30 to 40 reels of films to an iron dealer named Amir Khan, who later organized a traveling show in the provinces.43Umīd, Tārīkh-i sīnimā-yi Īrān, 1279-1357, 26. Unfortunately, there is a lack of clarity in the histories about the fate of Ivanov’s assets. Bahārlū, for example, has suggested that Ivanov sold his projection equipment and films in 1910 to Ismāʿīluf and Amīr Khan, who as partners undertook a provincial screening tour. See Bahārlū, Sad chihrih-ʾi sīnimā-yi Īrān, 14; Muhammad Tahāmi-Nizhād has also claimed that an Amir Khan opened a cinema on what is today Bāb-i Humāyūn Street, just south of Ivanov’s photography studio after July 1909 and the end of the ‘lesser tyranny’. See Tahāmi-Nizhād, Sīnimā-yi Īrān (Tehran: Daftar-i Pazhūhish-hā-yi Farhangī, 2001), 20; However, he does not indicate whether this Amir Khan is the same individual who bought Ivanov’s equipment and films. One year later, Ivanov left for Paris in service of the deposed Shah’s wife and remained there until his death on March 15, 1968.44Gaffary, Le cinèma en Iran, 4.

Figure 5: Portrait of Mahdī Ivanov in military uniform (1916)

In summary, Ivanov’s engagements with the cinematic medium were short-lived but eventful. Film historians have generally portrayed Ivanov negatively as a reactionary, with pointed reference to the personal relationships he had cultivated with the Qājār court and the Cossack royal guard. Their hostile profiles of Ivanov have (perhaps unintentionally) underplayed his early and meaningful contributions to cinema in Iran. However, a closer examination of his career would seem to indicate an individual capable of extending himself socially and professionally and even adjusting his political perspectives to secure his interests during a troubled time in modern Iranian history. As Hamid Naficy has written:

Like most secular modernists of the era with roots in traditional and religious cultures, Ivanov had divided loyalties and multiple identities. His mixed background could account for his political conservatism . . . as well as for his professional radicalism . . . That he set up his Farus Cinema with the aid of a revolutionary fighter despite his loyalty to the Shah and to the reactionary Russian forces; that he placed ads for his film programs in both politically radical and pro-constitution papers; and that he attempted to appease clerical leaders gives evidence more of his political flexibility and pragmatism than of his reactionary politics.45Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema: The Artisanal Era, 67.

The benefit of this more charitable reading of Ivanov is that it at least ascribes a logic to his professional trajectory that other histories have lacked.

Cite this article

This article revisits the complex legacy of Mahdī Ivanov, also known as Rūsī Khan, a pivotal yet polarizing figure in the early history of Iranian cinema. Born in Tehran in 1875 to Russian Tatar and British parentage, Ivanov’s mixed heritage and associations with the Qājār royal court and Russian forces have cast him in a reactionary light among historians. However, a nuanced analysis reveals Ivanov’s significant contributions to cinema in Iran, including his establishment of early cinema halls, innovative exhibition practices, and efforts to normalize film-going amidst political and religious resistance.

Ivanov’s career unfolded during a tumultuous period in Iranian history, marked by the Constitutional Revolution and shifting societal dynamics. Drawing on his experience as a court photographer, Ivanov introduced modern cinematic technologies and practices, such as live musical accompaniment, advertisements with program descriptions, and the use of translators (dilmaj) during screenings. Despite his affiliations with the monarchy and Russian authorities, Ivanov collaborated with revolutionary figures, opened cinemas in diverse neighborhoods, and sought to democratize access to film. This article critically examines Ivanov’s political pragmatism and cultural adaptability, arguing that his contributions to Iranian cinema extend beyond the reductive narratives of reactionary conservatism. By reinterpreting Ivanov’s role, the article highlights the intersections of modernity, culture, and cinema in early 20th-century Iran.