The Abadanis (1993): A Historical Testimony, Silenced

Leading Iranian filmmakers in both pre- and post-revolutionary stages have been practitioners of reality depiction, the depiction of social realities under silencing restrictions and censorships, through varying degrees of cinematic realism. The majority of Iranian films that have made their ways to international festivals, even the ones categorized as Iranian art films, have been expected to offer a view of the geographical, political, social, and existential realities of contemporary Iran. Iranian national films that succeed it gaining an international identity are expected to project an authentic image of life in Iran in order to function as a window in their border-crossing presence. In the past couple of years, such a reality-based-presumption has played a significant role in the government’s quarantining some Iranian films inside the country because of their dark and critical social approaches while promoting some other films in international festivals for a similar reason. The double-edged concept of realism, both promoting and hindering the passage of Iranian films in their border-crossing journeys, has caused controversies and resentments among film critics and Iranian audiences around the stylistic and cinematic value of the so-called festival films, raising doubts and resentments about their representational faithfulness in depicting and introducing Iranian people and their lifestyles to the global audience.

The available scholarship on the global visage of Iranian cinema has raised pointed questions about the works that have once migrated over the geographical borders and whether they represent the diversity of Iranian films. But to investigate the unreleased potential of the works that were prevented from crossing the borders, from inside or outside, for socio-political, financial or cultural reasons, raising questions about Iranian adaptations’ international anonymity, it is necessary to deal with hypothetical claims, contextual reviews, and many ifs and buts. The historical records do not highlight the fact that three years before Kīyārustamī’s Taste of Cherry’s grand success at the Cannes festival of 1997, which initiated the Palme-d’Or-winning film’s presence at international venues as an authentic cinematic portrait with a poetic exoticism, a cross-cultural adaptation of Vittorio De Sica’s Bicycle Thieves (1948) directed by Kīyānūsh ‛Ayyārī almost made it to the list of Cannes festival’s nominees but was not allowed to attend the festival because of its anti-war point of view and its alleged dark social realism (see figure 1). Today, it is almost impossible to imagine the difference The Abadanis’ presence at Cannes could have made to the general direction of international Iranian cinema, and its boycotted auteur director’s career. But it is possible to reconsider the space the film could open for international cinema’s capacities of border-crossing dialogues by crediting a cross-cultural adaptation of a globally acknowledged Italian neorealist film for its dialogic capacities in mirroring universal human conditions.1This article is based on chapter 4 of my PhD dissertation. See Naghmeh Rezaie, “Cross-Cultural Adaptations in National and International Cinemas: The Case of Iranian Films” (ProQuest Dissertations & Theses, 2021), chap IV.

Figure 1: The Abadanis- Systematically suppressed because of its anti-war tone and alleged dark social realism.

Only three years after The Abadanis’ unrealized attendance at Cannes, The Taste of Cherry (1997) won a Cannes award and officially initiated Iranian cinema’s globalization era. It took two more decades for the Iranian cinema to draw international attention to itself for a cross-cultural adaptation, when Farhādī’s The Salesman, an adaptation of Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman, won an Academy Award even though it was seriously treated as an adaptation.2Farhādī’s cinema is acknowledged for having passed behind a historically established borderline by portraying Iranian middle-class society in his Oscar-winning films and giving a voice and face to them in the global audience’s mindset—an image Iranian middle-class educated adults feel more comfortable identifying with on a global scale. I would argue that Iranian festival films, through historical circumstances and international reception and demand, have given voice to under-privileged groups of people and selected minorities, specifically from rural and poverty-stricken areas, who had not been in the center of the attention of the majority of Iranian cinemagoers until they gained a global voice and became the iconic figure of Iranian identity abroad. This development calls for a comparative analytical study of Hollywood’s’ ongoing struggles with universalizing the films of underprivileged peoples. See Naghmeh Rezaie, “Asghar Farhadi’s the Salesman: A Border-Crossing Adaptation in a Border-Blocking Time,” Literature/Film Quarterly 46, no. 4 (2018). It is a matter of speculation whether an Iranian social realist film of 1990s with distinguishable stylistic and thematic features but a background that included a prominent Italian precursor and repressive governmental forces would be capable of surpassing the temporal restrictions that blocked its way by all possible means, and the priority-posterity touchstones that still exist in adaptation debates, in order to reflect an identity of its own for a delayed reception in the history of the world cinema. The politically suppressed cross-cultural adaptation has always been in danger of being labeled as a shadowing double, or other, to its Oscar-winning Italian counterpart, which stands in a secure position in the global cinema. However, as argued by Thomas Leitch, history itself is also an adaptation, as “all histories are interpretations of earlier histories, [and] there is no such thing as uninterpreted or preinterpreted history”, which means priority does not promise originality.3Thomas Leitch, “History as Adaptation,” in The Politics of Adaptation: Media Convergence and Ideology, ed. Dan Hassler-Forest and Nicklas Pascal (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017), 13. The social realist films that register a historical testimony to their socio-political era, have already rewritten history (which is itself an adaptation) as well as re-adapting and documenting it. As also stated by Hutcheon, in the world of adaptations the second is not necessarily the secondary.4Linda Hutcheon, A Theory of Adaptation (New York: Routledge, 2006), 9. In this view, De Sica and ‛Ayyārī are both observers, narrators and adaptors in a post-war period that connects them in their universal concerns about human conditions.

Although controversies surround the degree of the influence of Italian neorealism on other national and new wave cinemas, including Iranian new wave films before the revolution and the reformist cinema after, the existence of such a link is indisputable.5Pierre Sorlin, Italian National Cinema 1896-1996 (London; New York: Routledge, 1996), 105. “An archetype of the postwar art cinemas around which the term [national cinema] was originally developed,” Neorealism has been readable as a response to the historical call of twentieth century for abandoning the old cause of bourgeois realism and replacing it with the values of social realism.6Mark Shiel, Italian Neorealism: Rebuilding the Cinematic City (London; New York: Wallflower Press, 2006), 6-34. Looking back at the history of Italian national cinema in view of the variations of the works and styles covered by this unifying but undefinable attribution, contemporary critics tend to approach neorealism not as a school or a movement but as “a collection of voices” associated with a specific historical period, nation, or national cinema.7Sorlin, Italian National Cinema, 91. The causes and consequences of Bicycle Thieves’ cinematic adaptation in Iran in 1990s, and the concepts of historical necessity and contextual proximity, direct us from the broad realm of neorealism’s effects on Iranian national cinema in general into a one-on-one comparison emphasizing the motives for the return of neorealism in The Abadanis.

The Abadanis (1993)

Figure 2: : Darvish-Burna-Hasan Khuf triangle- In quest of the stolen car under the skin of the city.

The Abadanis/Ābādānī-hā (1993), produced five years after the 1988 ceasefire agreement between Iraq and Iran, uses a wartime narrative timeline to explore the socio-political implications of the postwar period. ‛Ayyārī regards the last years of war in Tehran with a strongly antiwar critical tone, choosing one of the most memorable portrayals of postwar destitution in cinema as a framework for revisiting universal themes of war’s calamitous effects on human lives which is comparable with Rossellini’s Rome, Open City (1945) as well as De Sica’s Bicycle Thieves (1948). The film narrates the story of a war-refugee family from Ābādān (a southern city of Iran close to Persian Gulf severely affected by the war and evacuated for a period) living in a shelter in Tehran. The under-educated father, unable to read or write, heads his five-member family as a taxi driver, the only profession he can pursue in the metropolitan capital. When the car is stolen from the family who have already lost all their possessions in the war, they lose their last means of financial survival. The father and his son, Darvīsh and Burnā (Sa‛īd Pūrsamīmī and Sa‛īd Shaykhzādah),8The word Darvīsh stands for a man who is happy with poverty in a spiritual manner, and Burnā, which is alliterative with Bruno, means young and fresh. start a quest that takes them to the poverty-stricken suburban areas where stolen goods are stored and cannibalized. They are accompanied by Hasan Khuf (Hasan Rizā’ī), a character without a counterpart in De Sica’s version, who also turns out to be a thief, though a kindhearted one. He is familiar with the secrets of the slums of Tehran and agrees to drive them there in his broken vehicle in return for a daily payment. Together they go through the process of searching and witnessing layers of poverty, destruction and theft under the skin of the city (see figure 2). While the father and the driver are actively engaged in the act of searching, the boy finds himself in the position of a silent witness to what is going on around him, especially after his eyeglasses – his own most precious personal property- are stolen by the driver. Burnā keeps the secret to himself after discovering the glasses at Hasan’s house in the slums. By the end of the movie, Burnā reaches a new way of observing his world through a kind of camera he has created from broken objects he has found on the landfill, after his father has failed in his attempt to steal tires for their finally found but completely cannibalized car. They return from their journey, driving drowsy passengers from the suburbs to Tehran, in an almost undrivable car. The adapted and dramatized southern-theme music celebrates the bittersweet quality of their survival in its most basic terms, echoing the feeling of conclusion to an eight-year war (1980-1988) that left millions of casualties behind.

‛Ayyārī has deliberately avoided Bicycle Thieves’ absolute dark ending which depicts the father and son both stuck in a never-ending dilemma without any solutions. He has put a lens, a new means of observation and reflection, in Burnā’s hand who has reached a new worldview by the closing scene to project and promise a wiser world ahead.9Kianoush Ayari, personal interview by Naghmeh Rezaie, Tehran, Iran, July 29, 2015. The reflection of the drowsy passengers and the fatigued father in Burnā’s little camera with a sparkle of the sunshine, when the damaged car is once more moving, serves as the harbinger of a future to Burnā and his generation despite the density of hardships behind them, a light beam after the darkness (see figure 3).

Figure 3: The Closing scene- Reflection of a light beam after the darkness.

‛Ayyārī: A Resistant Reformist Filmmaker

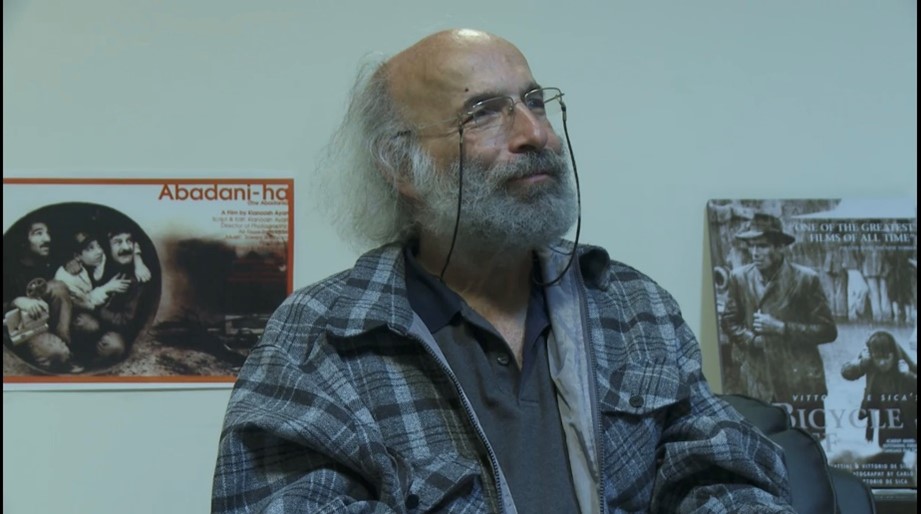

Figure 4: Interview with Kiyanush Ayyari- One of the most frequently restricted filmmakers in the history of Iranian cinema.

Kīyānūsh ‛Ayyārī, born in 1951 in the southern city of Ahwaz, is a prominent figure of the post-revolutionary Iranian films, and one of the most frequently suppressed and banned filmmakers in the history of Iranian cinema. He started his professional cinematic career right after the revolution with Tāzah Nafas-hā (1980), a documentary without any voiceover commentaries that shows the atmosphere of Tehran during the first days after the revolution, providing a distinctive visual testimony on that transitory historical period by witnessing and recording it.10This is ‛Ayyārī’s only released documentary film until today. However, during a phone conversation I had with him on Feb 8, 2019, I learned that he had directed two other short documentaries for TV (“The Pulse of the Train,” about southern trains before the revolution in 1977, and “The Sweet Soil,” about three Iranian villages with peculiar environmental conditions in 1981), both banned and never screened. ‛Ayyārī, one of the first of the celebrated post-revolutionary filmmakers, received Best Director’s awards at the 4th and the 6th Fajr Film festival in Iran for Dust Evil/Tanūrah-yi Dīv (1985) and Beyond the Fire/Ānsū-yi Ātash (1987). He is widely acknowledged by Iranian film critics as an independent auteur director whose films have not been viewed by many local or international audiences because of censorship and other repressive circumstances. He has been the screenwriter of all, and producer and editor of many, of his projects. Out of the thirteen feature films he has made, at least six have gone through extreme censorship during production or post-production, and three of them (Wake Up, Arezoo!, 2004; The Paternal House, 2012; and Canapé, 2016) have yet to receive the official permits allowing them to be shown in movie theatres in Iran. Wake Up Arezoo/ Bīdār shu Ārizū is a semi-documentary filmed in the ruins of Bam after the devastating earthquake of 26 December 2003 in the province of Kerman, Iran. ‛Ayyārī travelled to Bam shortly after the earthquake and made a feature film which documents the harsh realities of the ruinous time and the city, one more significant historical testimony in his filmography. The film has been banned from public show in Iran because of its dark depiction of realities; “I do apologize to the audiences if they find this film as bitter as the earthquake itself. Not hyperbole, this bitterness is simply resulted by the cast and crew’s emotional involvement with that environment. I understand if you feel an urge to leave the movie theater before the film ends because of this bitterness, and I won’t be upset”, these are ‛Ayyārī’s words in a press meeting, after he mentions that one of his local cast members of the film had lost 160 friends and relatives in the earthquake.11“Kīyānūsh ‛Ayyārī, Man na jasūr hastam va na jarīyān’sāz,” Iranian Students’ News Agency, Dec 17, 2017, isna.ir/xd2jLQ.

The Paternal House/ Khānah-i Pidarī (2012), made seven years after the unreleased Wake Up, Arezoo!, is ‛Ayyārī’s most controversial film until today: only shown in selected film festivals, released temporarily with restrictions, and re-banned repeatedly during a decade. ‛Ayyārī’s resistance against cutting one harsh honor killing scene, which is the core of the film’s narrative, has become a history-making resistance against censorship in Iran. The camera shows a teenage girl being brutally killed and buried by her father and brother in the basement of an old house in early twentieth century. The shadow of the murder continues to hunt the family and the house through generations, from the heart of tradition to contemporary Iran. In this elaborately critical and reformist film, ‛Ayyārī deals with the topic of honor killing, giving voice to the unvoiced victims of a socio-historical malaise through centuries, calling for a fundamental socio-cultural change. However, the authoritative figures have accused the film of exaggerated violence, calling it an unrealistic presentation of Iranian culture to local and global audiences, which in this context veils an anxiety over the dogmatist patriarchalism being attacked by the film more than any cultural (mis)representations. Nevertheless, when a new case of honor killing occurs in Iran and (if reported) shakes the media and the nation once again (which has happened a couple of times since the film’s production), the ghost of ‛Ayyārī’s film is resurrected once more, like the memory of the buried body of Molouk (the film’s perished character) in the basement. The silence of the banned film, as a genuine act against domestic violence, has frequently been compared with the silence of its buried character, a hunting shadow chasing the authorities. After a super-controversial release and re-banning in October 2019, ‛Ayyārī gave up on a seven-year long patience and sold the film to online streaming. However, it never reached the wide range of audiences it could potentially have after all interruptions and delays. Comparable with To Be or Not to Be/ Būdan yā Nabūdan (1998), another marginalized film in which ‛Ayyārī introduced and contextualized the concept of heart transplant and brain death for the first time in Iran, The Paternal House has also been about “reconstructing the culture in silence”.12Naghmeh Rezaie, “ū dar sukūt farhang mīsāzad,” Cinscreen, Feb 23, 2014, https://www.cinscreen.com/?c=8&id=4835.

‛Ayyārī is the first filmmaker who openly resisted using the compulsory Hijab in Iranian films even years before the Woman Life Freedom movement of 2023. In his next and most recent banned film, Canapé (2016), he has had female actors wearing wigs instead of head scarves in internal scenes in order to pass the filtering of Islamic hijab, asserting that his growing interest in realism does not allow him to show women with head scarves inside their apartments. This unseen film is the first post-revolutionary Iranian film made in Iran, with a contemporary setting and not a historical one, in which female actors are not wearing headscarves. Not surprisingly, this resistance halted the entire project, putting ‛Ayyārī on a shortlist of the most frequently banned filmmakers of Iranian cinema,13During the phone conversation I had with ‛Ayyārī on Feb 8, 2019, for supplementary details on our 2015 interview, he reviewed the timeline of his films’ screening one after the other, revealing how each single film was systematically restricted and marginalized in its showing seasons. He approved my attitude of introducing him as the most frequently banned filmmaker in the history of Iranian cinema, although with an embarrassment. systematically restricted with no intention of reconciliating with authoritative rules after the high prices he has paid for his career (see figure 4).14In 2022 ‛Ayyārī made a comedy, The Beach House/ Vīlā-yi Sāhilī, mainly for financial purposes. The film has been successful at the box office in Iran (screened in movie theaters in late 2023 and early 2024). Unfortunately, ‛Ayyārī has recently been dealing with medical conditions and cannot enjoy this little break from the habitual restriction and censorship.

The summary above does not include the number of screenplays and pitches rejected in pre-production, or the indirect restrictions imposed on his films shown in slow seasons in a limited number of movie theaters. Among ‛Ayyārī’s screenplays, three are cross-cultural adaptations produced in succession in 1990s: Du nīmah-i sīb/Two Halves of an Apple (1991), based on Lotti and Lisa, written by Erich Kastner; Ābādānī-hā/The Abadanis (1993), based on Bicycle Thieves (the film and the novel); and Shākh-i Gāv/ The Horn of the Cow (1995) based on Emil and the Detectives, written by Erich Kastner (‛Ayyārī’s only film for adolescent audiences). ‛Ayyārī points to the fact that he already had several original screenplays rejected by oversight committees when he started handing them adapted pitches during idle seasons, finding himself running out of obsessions and concerns: “One cannot go shopping for those,” he asserts.15‛Ayyārī, personal interview. Although he has never seen cinema and literature as naturally friendly companions, he believes that in exceptional cases, like Shakespeare’s Hamlet, literature productively merges with cinema.16‛Ayyārī, personal interview. The director’s account of The Abadanis’ emergence outshines the pragmatic reasons for making the other two adaptations (mainly idleness and the quest for box-office success) with an existential background, claiming that the urge to remake the Italian neorealist film in Iran has arisen from the heart of Iranian society rather than the cinematic resource.17‛Ayyārī, personal interview.

An Urge for Border-Crossing Adaptation

To address one of the primary questions of Linda Hutcheon in A Theory of Adaptation—why each new adaptation, especially a cross-cultural one, comes to being —‛Ayyārī identifies common thematic concerns he already had and his constant reflections upon the surrounding society that eventually connected him with De Sica’s film and Bartolini’s novel.18Hutcheon, Theory of Adaptation, 35. In the interview I recorded with him in 2015, he confirms his preoccupation with existential questions that had become like a soliloquy to him during the war and postwar years in a way that no filmmaker with a strong sense of social responsibility could ignore them anymore. He constantly asked himself if human beings were born only to suffer instead of finding some pleasure in their existence in this world. Over two decades after the film’s production, the filmmaker still believes that he made The Abadanis because of a social demand and as an answer to a humane urge rather than because of any attachment to neorealism as a valued artistic genre or as an homage to it, although the film is evidently approachable as one.19‛Ayyārī, personal interview.

‛Ayyārī sketches the lines of an epistemological correspondence between himself, De Sica’s film and Bartolini’s novel through a personal story that guided him step by step towards adapting Bicycle Thieves. He remembers how in the 1990s, when taking taxis late at night in Tehran, he kept thinking about why an old driver should be working in that hour to make a small amount of money instead of being home with his family. The questions were underlined once he accompanied his brother-in-law, an architect whose car had been first stolen and then cannibalized, to the slums to retrieve the trashed car, an unforgettable moment in which he could not stop thinking about how a similar condition could be absolutely devastating to a family whose only means of economic survival would be through the car. Such socio-existential concerns led to an aha moment the day ‛Ayyārī was devouring spaghetti for lunch, cooked by his late wife, and suddenly had a vision of Bruno and his father in the restaurant in De Sica’s film: their poverty in a restaurant that was not necessarily luxurious but still above their financial means and the small celebration of still being together after the fight scene and the mistaken impression that Bruno had been drowned. Before finishing his meal, ‛Ayyārī declared to his wife that he would adapt Bicycle Thieves.20This memory links the filmmaker’s present sense of reality (hunger and a spaghetti dish in front) and his conceptual preoccupation with social realism (centered on poverty, hunger and thievery) with a cinematic reality (the restaurant scene in De Sica’s film) in a way that continued through the production and post-production stages. A week later he made the first pitch for an official permit, which was to be rejected and revised over and over again during several seasons until the anniversary of the first submission, when a review committee member told him in a private conversation that they really did not want the film to be produced because of its antiwar theme and he should forget about it.21Ayari, personal interview. Although the Iraq-Iran war was a war imposed on Iran, and not initiated by it, pacifism was taboo because it could raise questions and doubts about the ideologies that associated defending Iranian soil with defending Iran’s revolution. In addition, there were and are serious concerns about undermining the spiritualism associated with the war, and questioning the sacredness integrated with the concept of martyrdom in Iran, by approaching it from a more existential and materialistic point of view. During the period when ‛Ayyārī’s primary plan for adapting Bicycle Thieves was suspended, a friend handed him an old and tattered version of Bartoloni’s novel translated into Farsi, which quite surprised him, as he found his state of mind even closer to that of the novel. He asserts that the final page(s) of the novel echoed his existential concerns about the never-ending human suffering:

Life consists in looking for what has been lost. It can be found once, twice, three times, as I twice have succeeded in finding my bicycle. But a third time will come, and I shall find nothing. It is like this with all existence, which is like a race through and over obstacles, only to be lost in the end; a race that starts the moment of birth when the infant leaves the womb, weeping for the protection that has been lost.22Luigi Bartolini, Bicycle Thieves, trans. by C.J. Richards (New York: Macmillan, 1950), 149.

Throughout the novel, he recalled, “thievery was described as becoming a national characteristic,” an observation he could identify with his own take on a society marked by repeating patterns of petit theft.23‛Ayyārī, personal interview. During this period ‛Ayyārī initiated a new project, Du nīmah-i sīb/ Two Halves of an Apple (1991), based on Lotti and Lisa, by the German author Erich Kastner, aiming to end his creative idleness and provide some funding for his future films. Although the film was successful at the box office, its own difficulties and obstacles in the production process and censorship and critical opposition afterward mark it as a huge nightmare in the filmmaker’s memories.24‛Ayyārī, personal interview. After this intermediary project, ‛Ayyārī resubmitted a screenplay based on Bicycle Thieves. This time he received a production permit but was heavily censored afterward, He eventually succeeded in bringing the film into being in production but not necessarily bringing it into becoming in terms of local or global reception.

Intertextuality Acknowledged

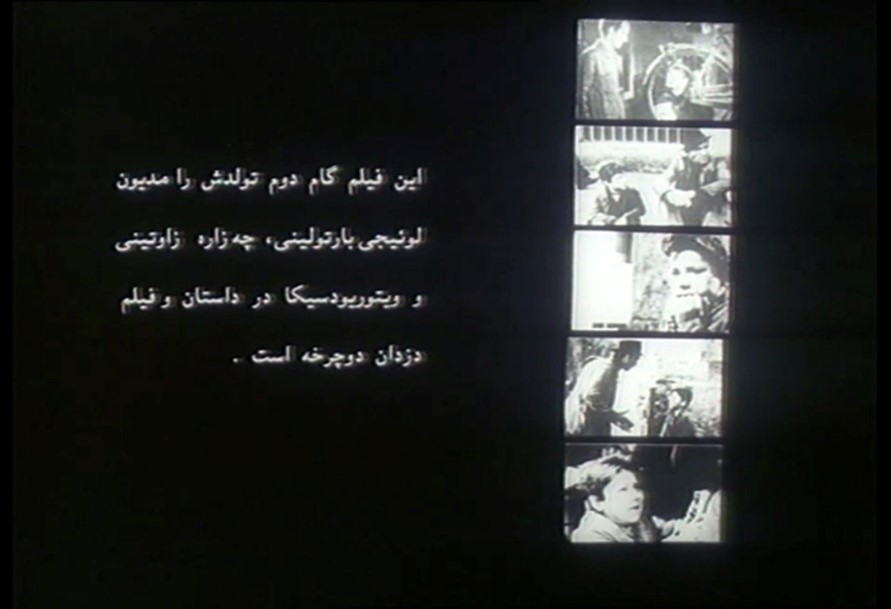

Figure 5: Opening credits- Intertextuality acknowledged.

The opening credits of The Abadanis acknowledge the film’s intertextual bearings in a statement that is both informative and interpretative. On the right hand of the screen, we can see small frames of De Sica’s film as the left-hand side proclaims: “This film owes the second step of its birth to Luigi Bartolini, Cesare Zavattini, and Vittorio De Sica in the story and film of Bicycle Thieves” (see figure 5). This highly responsible and carefully crafted announcement differs from most other films’ way of acknowledging their status as adaptation. The statement first alludes to the filmmaker’s ownership over the epistemological emergence of the work within the contemporary Iran by relating the second, and not the first, step of the film’s delivery to its Italian precursors. Then, by equally distributing the authorship credibility of the second degree among the Italian novelist, screenwriter, and filmmaker, it goes beyond the single-author acknowledgment that usually tag Bicycle Thieves as an item in Vittorio De Sica’s oeuvre. It is significant that ‛Ayyārī, the screenwriter/director/editor of the film with the authorship and authority proper to each role, avoids using the terms “adaptation” or “inspiration” and uses “the second step of birth” instead. The lexical choice embodies his theory of adaptation and authorship in one of those exceptional moments in which he finds himself in the position of an adaptor.

A Historical Testimony

One of the major attributes of neorealist cinema is its functionality as a “visual testimony” concerning the external physical world, registering specific periods and locations through cinematic narratives that develop into historical records.25Shiel, Italian Neorealism, 1-17. In his essay “Bicycle Thieves,” Bazin admires Italian neorealism’s conceptual proximity to social reality undertaken by the filmmakers’ propagandist agreement in producing unembellished scenarios, casting amateurs, and striving for photographic exactness in the absence of studio settings.26André Bazin, What is Cinema?, trans by Gray Hugh (Vol. II. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1967), 47-57. He celebrates Bicycle Thieves, in both scenario and form, as an emblem of neorealist cinema, calling it the only valid communist film” of the decade which “still has meaning even when you have abstracted its social significance,” with a protagonist living in a world in which “the poor must steal from each in order to survive”. 27Bazin, What is Cinema?, Vol II: 51.

Over half a century after Bazin’s perception, iconic neorealist films like Bicycle Thieves and Rome, Open City are still capable of affecting the contemporary global audiences’ conceptual image of postwar Italy. Their status as visual resources about the reality they portrayed makes them seem more of a point of origin than a reflector of those realities. This gradual shift of positions from registering aspects of a social reality toward staking a claim as an origin to those aspects is also detectable in a neorealist film’s border-crossing adaptation with its embodiment of double referential resources. ‛Ayyārī has minimized the communist implications of Bartolini, Zavatini, and De Sica by re-historicizing the story in a very different post-revolutionary and postwar society without forgoing Bicycle Thieves’s involvement in social disorders, and injustices, a society in which the poor still must steal from each other to survive. The neorealist film adapted into a new-neorealist one would embody the adapted resource as one recognizable reference, and its own contextual reality as the other one, with their primary and secondary states at work interchangeably.

The property of being and becoming a visual testimony to a socio-historical reality is detectable in The Abadanis, which can be approached as a new-neorealist film even though its more stylized cinematography and its impressive use of music prevent it from fitting into the exact shape of an unembellished neorealist movie. The audio component of the film is at the service of its thematic notions and visual realism, through a combination of music and sounds from radios and televisions, with a strong socio-critical tone that highlights the social realities of war years in their discordance with the political systems’ propagandic realism advertised by the media. We hear a radio station at beginning of the film with a happy-toned anchor promising the beginning of another beautiful winter day (on a day that will be the gloomiest for the characters), matched with other absurd and unrelatable radio sounds in the café scene and a TV program’s sound at Darvīsh’s home glorifying war and martyrdom (with images of soldiers on the screen). The background media sounds in this film are “real,” with referential realities for national audiences, but unrealistic in their failure to voice the reality of the society and people they are addressing. The musical score, composed by Sa‛īd Shahrām, plays a dominant role in the film’s aesthetics with a hybrid composite that adapts the themes of Iranian southern music to a gloomy wartime Tehran. The merry theme of the Ābādāni percussion songs is artistically dramatized in Shahram’s music, which thematizes Darvīsh’s alienation from his war-torn hometown. In the scene in which Darvīsh is informed that the police have found his car, we hear the original Ābādāni song Ābādān Gulistānah (Ābādān is a garden) played in a cassette player to release the bittersweet quality of the moment, captured in Darvīsh’s tearful laughter, to its full potential. Many of these audio signs are imperceptible to international audiences, at least in the subtitle level, while they have contributed to the film’s restriction within its national borders.

The Abadanis is a formalist-realist film, while the first generation of purely Italian neorealist films did not necessarily embody all the demands of neorealism (such as “the use of nonprofessional actors, the avoidance of ornamental mise-en-scene, a preference of natural light etc.”) within one single work either.28Shiel, Italian Neorealism, 2. In Pierre Sorlin’s words, “as soon as one looks for precise criteria, Neorealism vanishes: its consistency resides in its ability to avoid definitions”. 29Sorlin, Italian National Cinema, 97. The primary concern of neorealism, that is reflecting social reality, attracted filmmakers all over the world as a style more than a genre, echoed in diverse global films that may disregard Italian neorealism’s basic rules. However, not all those rules were observed in every Italian neorealist single work either: “Today, films considered neorealist break these unwritten rules in one way or another, yet, for reasons that remain obscure, still present themselves as neorealist”.30Laura E Ruberto and Kristi M. Wilson, “Introduction,” in Italian Neorealism and Gobal Cinema, ed. Laura E. Ruberto and Kristi M. Wilson (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2007) 7. Ruberto and Wilson identify Bicycle Thieves’ mixed neorealist elements as “the film almost religiously follows the continuity of time and space rule, uses some nonprofessional actors and colloquial speech, and reflects particular historical conditions, it also relies on an intricate and contrived plot, was made with a huge Hollywood-style budget, and avails itself of all manner of movie-making artifice”.31Ruberto and Wilson, “Introduction”, 9-10. In this view, the Iranian adaptation adheres to the basics of neorealism, but it also departs from some traditions and merges the territories of the author and the adaptor.

Figure 6: Alienation- Poursamimi masterfully plays an accented and underprivileged war refugee in Tehran.

While The Abadanis attests to the urge of reflecting social reality as a primary concern, the film’s stylistic composite also accords with some neorealist rules which should be adequate to categorize it as a neorealist adaptation of its Italian counterpart which is arguably not purely neorealist although universally known as such. The colloquial speech in ‛Ayyārī’s film goes through a second level of indigenization, for Darvīsh speaks Farsi in a southern accent that repeatedly highlights both his simplicity and his strangeness in Tehran in contrast with local society, especially Hasan, whose vernacular language and culture of undereducated urban dealers is contrasted with those of more complicated characters. At the time the film was produced, the actors were neither nonprofessionals nor stars but vaguely familiar faces that could keep the story in a close proximity to a documentary, without promising any box office success.32After this film, and in his gradual move towards practices of purer realism, Ayari lost his interest in employing actors/actresses at all familiar to the audience. He replaced the leading role actress of the film To Be or Not to Be/Būdan yā Nabūdan (1997) because she had already accepted another role when they were in pre-production process (Hadīyyah Tihrānī turned overnight into a superstar who could guarantee a film’s box office success). He introduced new faces and talents to Iranian cinema in his quest for nonprofessional actors like ‛Asal Badī‛ī (1977-2013), who replaced Tihrānī. Sa‛īd Pūrsamīmī, the leading actor, had been an admired figure in the theater and onscreen, but his face would not commercialize the film. He masterfully plays an accented and underprivileged war refugee in the alienating capital city who is carrying the burden of his family on his shoulders (see figure 6). Hasan Rizā’ī (Hasan Khuf), an unappreciated actor of many minor roles in pre-revolutionary cinema who later became a favorite of ‛Ayyārī, was nominated for Best Supporting Actor at the Fajr festival—the only nomination the film received in the season of a very cold welcome. Sa‛īd Shaykhzādah (as Burnā) was also an experienced young actor who became better known on television than cinema screens as an adult. All three presented noteworthy performances in The Abadanis without being noted by film critics for this triangular set, which is also a point of departure from the Italian version’s father-son iconic image.

Figure 7: Burnā’s gaze- A close observer and a silent witness.

Jaimey Fisher argues that “De Sica’s Bicycle Thieves deliberately deploys the narrative gaze of the child to subvert the masculine antihero” and that “by introducing the gaze of the son upon the father, De Sica foregrounds the transformation of the traditional male subject of the gaze into a humiliated object of the gaze”.33Jaimey Fisher, “On the Ruins of Masculinity: The Figure of the Child in Italian Neorealism and the German Rubble-Film,” in Italian Neorealism and Global Cinema, ed. Laura E. Ruberto and Kristi M. Wilson (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2007) 36. This reading is even more relevant to ‛Ayyārī’s film, in which the teenage son is not only a close observer of his father’s struggles within the surrounding world but also a silent witness of aspects that are not visible to his father (see figure 7). Although in the fortuneteller’s scene, Burnā does not “see” the figure of their car’s thief in the mirror, as he is supposed to, in two other scenes he catches two actual thieves through observation: first in a café scene (before the fortuneteller’s) in which he sees a thief stealing a bicycle through the window (a direct reference to the Italian version) and quickly informs the owner of the incident, and later when he identifies Hasan as the thief of his own glasses and lets it go in silence. If “Bruno triangulates the relationship of the protagonist to his environment [that] marks Antonio’s transformation into the object of contemplation,” Burnā’s presence in a triangular human relationship, between a thief-seeker and a thief, marks the human condition in which both sides are struggling for survival “into the object of contemplation” in the context of an alienating environment where a thief is not the other.34Fisher, “On the Ruins,” 37. The triangular set of Burnā-Darvīsh-Hasan (see figure 2), however, enhances the sense of what Ruberto describes as a “male-male bond” in Italian neorealist films, which takes into consideration but marginalizes female presences in the social reality depicted by both Bicycle Thieves and The Abadanis.35Laura E Ruberto, “Neorealism and Contemporary European Immigration,” in Italian Neorealism and Gobal Cinema, ed. Laura E. Ruberto and Kristi M. Wilson (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2007) 242.

The Abadanis has been viewed by too few audiences and film critics within or outside its homeland to have been categorized as either a self-sufficient postwar film or a border-crossing adaptation (the film is available with English subtitles on IMVBox).36For the full version of the film with English subtitles see The Abadanis | Abadaniha (آبادانیها) English Subtitles – IMVBox However, two decades after its production, the film reflects the re-historicized resonance of Italian neorealism with postwar Iranian cinema, far from the communist and anti-fascist tensions of postwar Italy but close to its fundamental concerns about social classes, poverty, and human conditions in a dehumanizing postwar urban setting. On the other side of its intertextual relations with De Sica’s film and Bartoloni’s novel, the film offers a high-resolution visual and conceptual testimony on the social conditions of life for lower classes in the postwar years of Tehran, leaving a cinematic mark on the beginning of the reform era in Iran with its rapid changes of socio-economic infrastructures that deepened gaps between social classes. This embodiment of intermingled levels of referential and perceptual realities in relation to the Italian novel, the Italian film of 1950s, and the social conditions of Iran in 1990s marks The Abadanis as a new-neorealist adaptation originating in the hybrid context of historical past and historical present in post–World War II Rome and post–Iraq-Iran war Tehran.

From Rome to Tehran

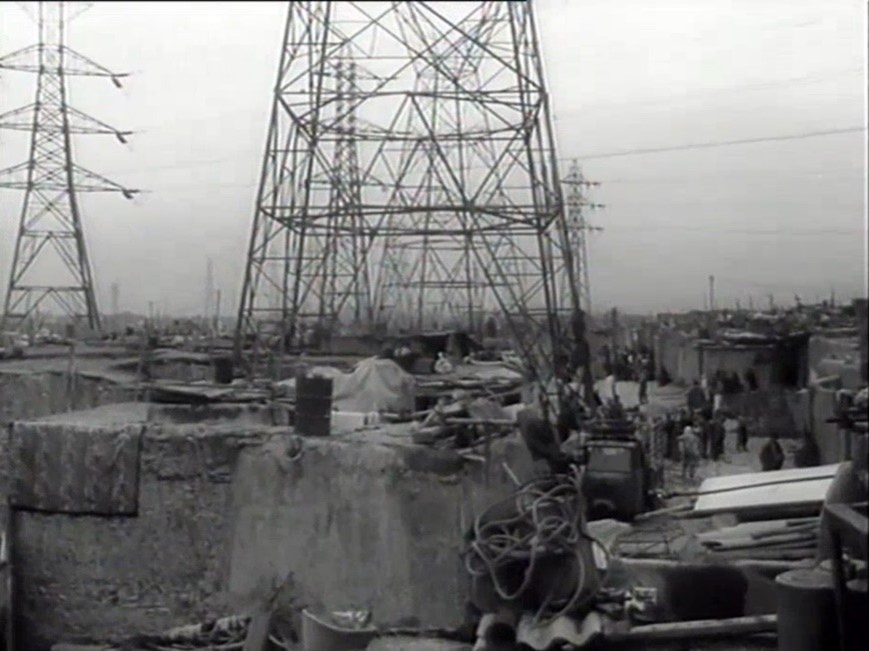

The Abadanis is indeed a visual testimony to the marginalized aspects of the postwar capital city of Iran, as neorealist films have constructed historical windows on postwar Roman societies.37Sorlin, Italian National Cinema, 104. Tehran in this film is remote from a contemporary Iranian audience’s visual expectations, as it has gone through several stages of metamorphosis to exhibit abundant signs of modernity and capitalism. The postwar capital city of Iran recorded by ‛Alī-Rizā Zarrīndast’s camera in the 1990s was in a transitional phase of reconstruction and modernization. Throughout the film, we observe the city’s downtown spotted by construction sites and cranes—foregrounding the high-rises and the raise of a new social class—and its suburban slums scarred by huge hazardous pylons under which marginalized poor families struggle for survival (see figure 8). Before the huge highways have been thronged by luxurious cars (by no means their owners’ only means of survival), Tehran is as nakedly documented in ‛Ayyārī’s film as Rome with its long lines of workers, over-crowded buses, and inter-crossing bicycles and thieves was in De Sica’s. Today, the scenes of the inter-crossing bicycles in De Sica’s film sound more surreal than real, at least to a contemporary non-Italian viewer, as the descriptions of the absolute chaos in stolen goods’ markets in Bartolini’s novel are hard to imagine. Arguably, realism might lose its perceptional assertions by becoming a point of reference to itself, outside its primary historical and geographical context.

Figure 8: Documenting the slums- Marginalized families struggling for survival under hazardous pylons.

Figure 9: Documenting Tehran- The center of capital city in 1990s, by the Sayid Khandan bridge.

‛Ayyārī’s Tehran might not even be recognizable by middle-class and upper-middle-class Iranian viewers who had never had a chance of confronting and observing the spatial manifestations of poverty pushed further and further to the margins. The war refugees’ building in which Darvīsh and his family dwell was in fact a continental hotel before the revolution, located in the center of Tehran by the Sayid Khandān Bridge, which had lost its luxurious aura during the war years by being assigned a utilitarian purpose. After the refugees’ return to their hometowns, the decomposed and destructed building was left evacuated and purposeless for years, with broken windows and empty dark inner space which reflected the recent war history and affected the neighborhood’s civil aesthetics drastically.38As a child growing up in Tehran, I used to gaze through this view over and over again, when passing over the Sayid Khandān bridge by car, trying hard but failing to imagine the empty, poverty-stricken building as a five-star hotel as my parents described it for me. Today the building does not exist anymore, and it might not spark the memories of younger audiences or more recent Tehran residents. The film depicts and records that building from inside, without any embellishments, as a spatial manifestation of an eight-year war that de-located thousands and thousands of people from their hometowns. When I asked ‛Ayyārī if he was documenting the postwar Tehran transition, he agreed that “unintentionally it becomes a document” (see figure 9). 39‛Ayyārī, personal interview.

The city plays an integral role in the existential reality of Italian neorealist films. In the absence of a studio mise-en-scene, the super-ordinary characters—instead of super stars—strive for survival in a postwar city which strives for revival through reconstructions; in other words, the city and the characters reflect each other’s traumatic image in a synecdochic coexistence. Bazin asserts that such a realistic registration and depiction of the postwar society reflected in the postwar urban zones is an essential characteristic that elevates neorealism to the status of pure cinema.40Bazin, What is Cinema?, Vol II: 47. De Sica’s film is a historical document of postwar Rome recorded without any cinematic distortions or make-up, and according to Bazin “it would be no exaggeration to say that Ladri di Biciclette is the story of a walk through Rome by a father and his son”. 41Bazin, What is Cinema?, Vol II: 55. The Abadanis is also the story of a passage through Tehran by a father and his son, who speak the national language with a southern accent (an important characteristic imperceptible to a non-Persian-speaking audience) and consider themselves strangers in the city even though they have been living in it for almost seven years, since the beginning of the war. As refugees, they bear an extra burden of alienation in the traumatic urban space, for they have already been banished from their own city. The fact that they are strangers in Tehran adds to the eccentricities and cruelties of a wartime city that has no ultimate resolutions to offer. Rome and Tehran, in Bicycle Thieves and The Abadanis, are historicized as looming inhuman characters that frame ongoing human struggles for survival.

‛Ayyārī has always insisted that his film is in black-and-white not to imitate De Sica’s film but because he could not see any colors in Tehran in 1990s that would justify shooting in color: “This might not be the impression of De Sica’s film. As in the time I was making this film I perceived Tehran in this way, dark, gloomy and colorless. I believe that all characteristics of Tehran could be exhibited only in a black and white film. Of course, Bicycle Thieves promoted this desire. I also should add that I always wanted to make a black and white film”.42‛Ayyārī, personal interview. When asked if he could have been able to see more colors in Tehran if De Sica’s film had been in color, he replied that he would still have made his film in black and white.43‛Ayyārī, personal interview. This statement cannot be confirmed, as De Sica’s film is famously and classically in black and white, but it demonstrates how the filmmaker describes the adapting process as initiated by an internal demand intersecting with an external solution in the to-be-adapted text that also illuminates the adapted and adapting texts’ non-linear correlations beyond the priority-posterity classifications.

Parallel Mirrors

Bazin, who defends adaptation as a digest as long as it conveys the spirit of the novel, prioritizes the reality of De Sica’s film over the spirit of the novel by attributing it to the reality of the world it reflects rather than the fictional reality of the novel.44Timothy Corrigan, ed, Film and Literature: An Introduction and Reader (New York: Routledge, 2012), 57.64. The spatial reality of Bicycle Thieves, which accords with Bazin’s expectations of cinematic reality, evolves from the fictional realism of Luigi Bartoloni’s text (with its detailed descriptions of postwar social disorders, thievery and poverty) as well as Zavattini and De Sica’s observations of Rome. And the existential reality of The Abadanis evolves from all these texts, which become contexts to ‛Ayyārī’s observations of his contemporary Tehran. According to a linear priority-posterity point of view, Bartoloni/Zavattini/De Sica’s depiction of Rome contextualizes ‛Ayyārī’s Tehran as a secondary spatial entity. The elevated status of Bicycle Thieves in global cinema versus the marginalized status of The Abadanis in Iranian cinema makes the concept of re-contextualization even more complicated, for the second film has never crossed the borders of its geography to showcase its historical exigencies to the world. Thus, the film has more often been contextualized by the one-line-phrase “an adaptation of Bicycle Thieves,” justifying its marginalization to those who have never had a chance of viewing it, before raising serious concerns about how, and more importantly why, it has been re-contextualizing De Sica’s “masterpiece” in contemporary Tehran.

Realism is not only a matter of reference but also a matter of perception. The difference between referential reality and perceptual reality constitutes part of the bifurcation between formalist and realist theory, and as described by Stephen Prince, “a perceptually realistic image is one which structurally corresponds to the viewer’s audiovisual experience of three-dimensional space”.45Stephen Prince, “True Lies: Perceptual Realism, Digital Images, and Film Theory,” Film quarterly 49, no. 3 (1996): 32. In viewing a contemporary adaptation of a highly recognized film like Bicycle Thieves, knowing Iranian audiences who have experienced the postwar years in Iran and are also familiar with Italian neorealism and Bicycle Thieves (the few who have even seen the Iranian version!) would find themselves embracing a combined package of referential and perceptual realities as the projections of De Sica’s world and ‛Ayyārī’s world are involved in a constant interplay, as if the audience for each film is looking through a conceptual prism that constantly reflects the images, moments and incidents of the other film quite apart from the question of its priority or posterity. Narrative parallels between ‛Ayyārī’s adaptation and De Sica’s film, manifested in a few scene-by-scene echoes like the restaurant scenes, complicate The Abadanis’ posture as a social realist film, whose referential reality is rooted in both 1940s Rome and 1990s Tehran.

It turns out to be a challenge to distinguish between referential and perceptual realities in the reception process of unknowing audiences who confront a screen-to-screen adaptation with its complex bearing of visual and thematic intertextuality. In cinematic adaptations—especially in second or third adaptations—each visual signifier could potentially carry a combination of perceptual and referential realities in relation to the other adaptation(s) or the actual three-dimensional world experienced by the audience. Reality itself becomes an even more complicated concept when each audio-visual signifier in one adaptation can embrace a chain of other realities as its possible signifieds who connect multiple adaptations with each other and with the social, cultural and historical context of each single adaptation. This hybrid realism manifests itself more clearly in stylistic and aesthetic parallelisms in film-to-film adaptations of neorealism.

Burnā’s encounter with the other young boy who belongs to a higher social class juxtaposed by his upcoming encounter with slums children in the next scenes, captures faces of class inequality as a social reality in post-war Iran (see figures 10 and 11). On the one hand, the restaurant scenes in Bicycle Thieves and The Abadanis function as mirrors to each other, but it is not easy to decide whether the relation between the Iranian restaurant scene (with Burnā, father and the driver) with the Italian restaurant scene (with Bruno and father) invites the international audience to deal with a referential reality or a perceptual one. The Iranian restaurant in The Abadanis, serving traditional kebabs in its 1990s setting (marked by both spatial and costume design), is immediately associated with its own locally observed, referential reality in the Iranian audience’s mindset independent of De Sica’s word.

Figure 10 – The Restaurant scene- Burnā’s direct and indirect observation of the upper-class boy.

Figure 11: Faces of class inequality- Burnā’s close encounter with slums children.

As De Sica’s globally acknowledged neorealist film institutes an immediate referential reality for ‛Ayyārī’s cross-cultural adaptation, and as it is arguable that the reality of the Italian film is itself a perceptual one, The Abadanis strives for a balance between the two concepts in order to position itself as a nationalized international adaptation. The novel, the Italian adaptation and the Iranian adaptation share an underlying pre-occupation with the act of stealing and theft as a defining social phenomenon in two postwar capitals, with a common concern over human conditions and calamities. The war functions as a unifying historical fact through which the historical necessity for a certain kind of cinema repeats itself.

Bartolini’s Bicycle Thieves (1946)

The Abadanis (‛Ayyārī 1993)

Bicycle Thieves (De Sica 1948) Bicycle Thieves (Luigi Bartolini 1946)

It is hard to argue that The Abadanis is adapted from Bartolini’s novel instead of Zavattini-De Sica’s adapted screenplay because the lower-middle-class-son quest plotline narrated from a third person (camera’s) point of view which takes place on a different social and intellectual level throughout the novel. Still, it is arguable that De Sica, Zavattini and even ‛Ayyārī have stood in a position comparable to that of the novel’s narrator, observing their decaying society and advancing critical commentaries on the human condition. Bartolini’s first-person narrator is an educated man apparently from the prewar middle class who has been downgraded like everybody else during the war. He is a professor, a journalist, a writer, a thinker, and a critical observer of and commentator on socio-political changes who has been kept under control during the war years as an anti-fascist who is now on a quest for his stolen bicycle among people, black markets and the police in all their indecent interrelations. Unlike De Sica and ‛Ayyārī’s protagonists, he has a second bicycle which facilitates his journey to different spots, as he has already gained an expertise in searching for stolen bicycles: “I have found two of the five bicycles that were stolen from me during my three years of residence in Rome”.46Bartolini, Bicycle Thieves, 87. His observations come in the form of detailed descriptions of social conditions in Rome and reflections on the changes in socio-political norms during war and after. This quest gives him another chance to observe and record the realities of chaotic postwar Italy, reminding us of the Iranian filmmaker’s description of how he contemplated his surrounding society in those years, as if Bartolini’s narrator, rather than his narrative, had first found a cross-cultural counterpart:

At the sight of this swarming misery, of these insect-like people with thin swallow faces, I thought of humanity as seen through the eyes of poets and philosophers— poor humanity, seen by us through rose colored glasses, while reality consists at present of a people poor and crafty, people who, astutely and sometimes with real flashes of genius, succeed in assuaging hunger.47Bartolini, Bicycle Thieves, 20.

Bartolini’s text unfolds into a detailed descriptive narrative of an encompassing level of destitution in postwar Rome, “the Rome of thieves”,48Bartolini, Bicycle Thieves, 14. in which any object, as trivial as a soap or a pen, could be stolen and black marketed, and every seller or buyer of those objects would intentionally or unintentionally be involved in theft, deducing that “man is, at best, a thief by nature”.49Bartolini, Bicycle Thieves, 47. Small objects are constantly re-stolen and re-sold in this strange world, diminishing the sense of humanism in the chaotic scenery in which woman sell their bodies for a pair of socks and the policemen exchange justice for cigarettes: “But in these terrible days of anarchy, where could one find a policeman? … A waste of time, for you may be sure that no policeman will look for your bicycle or for the thief”.50Bartolini, Bicycle Thieves, 3. Through such concrete observations over the city’s “anarchy,” the narrator criticizes socio-political establishments remembering their shifting weights within a short period of fascism to anti-fascism. He also shares his serious concerns about intellectual impotency beside intellectuals’ poverty under such circumstances: they cannot steal, they cannot earn money, and they cannot influence the society to change: “The bread ration for intellectuals like us was and is (Germans or Americans make no difference) the minimum. I who earn nothing because I am an intellectual … This is not democracy. This is a farce, a farce that humiliates democracy itself. But we shall see if things can go on in this way”.51Bartolini, Bicycle Thieves, 54. If such a critical undertone has been overshadowed by De Sica’s film’s boldly communist tone, it is still traceable in intellectual causes that have perpetuated the novel’s adaptation for cinema in two countries.

The Land of Stolen Objects

Figure 12: Dehumanization- The land of stolen and war-stricken objects.

The Abadanis may be approached as an adaptation of Bartolini’s novel, alongside De Sica’s film, through its thematic and visual object-oriented body. The three characters of the film, none possessed many belongings, each depend on a single object for survival. Two of these objects go missing, while the third hardly functions: Darvīsh’s 1970 Paykān (already old and malfunctioning, stolen and found scrapped but still put to work), Burnā’s eyeglasses (stolen by Hasan, found but not reclaimed by Burnā, who replaces them by hand-made mirror-lenses he has invented), and Hasan’s vehicle (a wrecked three wheel motorcycle carrying stolen goods and scraps which will be even more damaged in the course of the film). Alongside this single-object-dependency embedded in the story, the film’s visual landscape offers an extended vision of scrap yards, discarded objects, stolen goods and a mélange of fragmented metal pieces far from their utilitarian purposes in both wide and close shots that contextualize the dehumanizing atmosphere of the world in which the characters struggle to survive, as if memorializing war zones in deserted urban slums (see figure 12). ‛Alī-Rizā Zarrīndast’s camera follows Burnā’s hands as the characters search in vain among useless objects stored in Hasan’s motorbike in close shots that match with wide shots portraying scrap yards of endless objects, reminders of war debris and destructions (although not necessarily all damaged by war).

The intercut shots that frame huge pylons (one about to crash down after the bombardment scene) in their realistic composite, and the pylons in the background of several other shots bear symbolic echoes of the three characters affected by shaky industrial infrastructures on the verge of falling apart, and their later visit to Hasan Khuf’s home in a hazardous slum with children playing under the pylons uncovers even more faces of this deprivation and destitution (see figure 13). ‘Ayyārī’s film shows the objectification of human beings under the war’s dehumanizing effects, a theme of both Bartolini’s novel and De Sica’s film, through its visual depiction of human loneliness among endless broken objects, and in the search for objects (see figure 14). This style also resonates with ‘Ayyārī’s materialistic approach to socio-historical phenomena such as a war far removed from spiritual promises, introducing one of the main reasons that his work was discouraged by governmental figures who actively encourage ideological impulses in art products.

Figure 13- Life under the pylons- The echo of shaky industrial infrastructures.

Figure 14: Human loneliness- Among endless broken objects and in search for objects.

Double Marginalization

To the historical stands of The Abadanis one should also add the meta-textual theme of the historical suppression the film has gone through since its production. Out of the entire population of cinemagoers and film scholars and critics, only a few hundred people have ever seen it. The film was shown in a limited number of movie theaters in Iran for only a few days during the slow season; no trailers were produced. It was the first Iranian film admitted to the Cannes film festival, but it did not receive the Islamic Ministry of Culture’s permit to attend the festival. It won the Silver Leopard in the 47th Locarno film festival in 1994, and after its screening that festival it was selected as the first Iranian film to be archived in Cinémathèque Française but was again forced to withdraw from it.52‛Ayyārī, personal interview. The winner of the Golden Leopard 1993 Locarno Festival was also an Iranian film, Khumrah (The Jar), directed by Ebrahim Forouzesh and based on a story by the Iranian writer of young adult fiction Houshang Moradi Kermani. Khomreh was also the winner of the CICAE jury prize and the second youth jury’s prize UBs.

In a 2016 conference meeting in Iran, after The Salesman’s success at Cannes film festival (winning the Best Screenplay and Best Actor awards), Farhādī criticized the label of “dark depiction”, or Sīyāh Namāyī, many social realist Iranian films have been accused of and accordingly banned from attending international film festivals. He referred to Mehrjui’s The Cow (1969) as a treasure and compared it with more recent The Abadanis (1993), as two examples of allegedly dark films in which we can find “shining diamonds”.53“Tamām-i hāshīyah va matn-i nishast-i Asghar Farhādī dar Īrān,” Ensafnews, May 31, 2016, https://ensafnews.com/?p=30290 His bold statement did, however, not arouse any great curiosity about the less-viewed The Abadanis. ‘Ayyārī’s cross-cultural adaptation was suppressed by the direct intrusion of political forces of its time and has remained neglected in local and global criticism and comparative studies to this day.54In the interview Ayari identifies a political figure who had asserted that he would block his own family members from movie theaters if they ever decided to watch this film. Nevertheless, the film has its own ardent proponents among film critics and audiences in Iran who still celebrate it in annual screenings and try to draw new attention to the film’s aesthetic and conceptual significance.

The scholarship on the impacts of neorealism on the post-revolutionary Iranian cinema does not provide us with a deep insight into ‘Ayyārī’s works or this particular adaptation. Over the past two decades The Abadanis has remained an isolated entry in the area of realist Iranian cinema, singled out in only a few marginal references. In his English-language book published in London, Hamid Reza Sadr (R.I.P.) introduces The Abadanis as a film in which “cynicism stemming from the aftermath of war is evident”.55Hamid Reza, Sadr, Iranian Cinema: A Political History (London: I.B. Tauris, 2006), 218. Also, there is a one-line reference in the book Vittorio De Sica Contemporary Perspectives which introduces The Abadanis as “virtually reworking of Bicycle Thieves in contemporary Tehran”.56Stephen Snyder and Howard Curle, Vittorio De Sica: Contemporary Perspectives (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2000),8. The critical studies of realism in Iranian cinema usually revolve around “original films” with already available international profiles, represented by ‛Abbās Kīyārustamī’s works, in order to deal with them in a globally pursuable discourse. Naficy speaks about the hybridity of Iranian neorealism as a genre that subverts both realism and neorealism, and refers to the five “prerequisite characteristics of neorealism”57Geographically bounded, temporally bounded, existence of masters, existence of disciples, and formation of set of rules (qtd. in Naficy, “Social History” Vol IV: 187) defined by Georges Sadoul, to maintain that “the Iranian-style neorealism has not been homogenous, exhibiting itself in two different styles under two different political systems further it has been neither a fully formed film school nor a movement but a moment of convergence in the social history of Iranian cinema”.58Hamid Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema (Durham: Duke University Press, 2011), Vol IV:188. ‘Ayyārī’s filmmaking style may not fulfill the prerequisites of art-house films in Iran, but it speaks to the basics of neorealism. Although ‘Ayyārī announces that he has never been a big fan of Italian neorealism and did not make The Abadanis as an homage to De Sica, the work now functions as one, and ‘Ayyārī’s filmography shows a constant movement towards a higher degree of new realism in Iranian cinema.59In his more recent movies Ayari has been avoiding many technical plays in cinematography and he is not using musical scores. When he made The Abadanis he still indulged in such artistic embellishments.

Whether or not The Abadanis’ announced but unrealized attendance in Cannes could have had a determining impact on the history of Iranian cinema and the international recognition of the director, it is arguable that the experience of watching Bicycle Thieves and the act of analyzing it have not been a genuinely complete act or experience since 1993 when its Iranian counterpart was hindered from speaking back to its historical precursor on a global stage, if such a completeness ever exists beyond hypothesis. As Grossman puts it, “adaptations can change our ways of determining where individual works of art begin and end and shift our ideas about what constitutes art in general”.60Julie Grossman, Literature, Film, and Their Hideous Progeny: Adaptation and Elastextity (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015), 3. She introduces adaptations that are “in dialogue with previous texts and self-conscious of the multitudinous influences on any one work of art … as the new avant-garde”.61Grossman, Literature, Film, 3. Although Abadanis is not an avant-garde film according to Iranian film criticism, its dissonance with other 1990s Iranian films in form and multitude intertextual bearings beside its broken communicative discourse with the world cinema despite the dialogic embodiments may allow approaching it as an unrecognized “new avant-garde” as well.

Hollywood would regard the two cinematic adaptations of Bartolini’s novel as equally foreign; ‘Ayyārī’s cross-cultural one has simply been rejected without ever being allowed to cross over the imposed boundaries to be evaluated. It may be wondered whether there is a third of fourth unknown adaptation somewhere in the world, re-historicizing a history, but too late to be valorized by the early testimony of Andre Bazin, who aimed to “be the one to introduce De Sica to him” and to the world.62Bazin, What is Cinema?, Vol II: 61. I asked ‘Ayyārī if he assumes that the film had an expiration date, as an art product, so that it is too late for it to be reconsidered: “Not at all”, he answered, “this is the film which has burnt my heart and there is no expiration to that”.63‛Ayyārī, personal interview. Then I asked him if he could imagine a time in the future when The Abadanis, called by him “one of the biggest victims in the history of Iranian cinema”, would find its proper place among film critics and audiences, he answered with a tired expression: “I really do not know that. I hope this happens one day”.64‛Ayyārī, personal interview. See https://youtu.be/HvQ5Sp2MFI0?si=L_-jsOWScEf394ff

Cite this article

This article examines Kīyānūsh ‛Ayyārī’s The Abadanis (1993), a neorealist film that reflects the socio-economic aftermath of the Iran-Iraq War. Drawing inspiration from Italian neorealism, particularly Vittorio De Sica’s Bicycle Thieves, the film portrays a war-displaced family struggling to adapt to life in Tehran. The article analyzes how The Abadanis critiques systemic inequalities while illustrating the resilience of its characters. Suppressed for its anti-war sentiment, the film’s limited distribution underscores the impact of censorship on Iran’s cinematic legacy. This study situates The Abadanis as a pivotal work in Iranian cinema, blending local and global cinematic traditions to offer a powerful critique of post-war realities.