Marvā Nabīlī’s The Sealed Soil as Slow Cinema

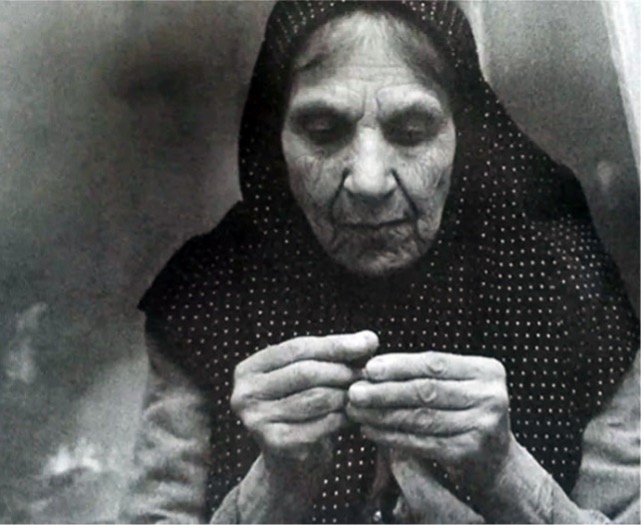

Figure 1: Still from The Sealed Soil (Khāk-i sar bih muhr), directed by Marvā Nabīlī, 1977.

Introduction

In the 1970s, when Iranian cinema was largely dominated by male filmmakers and women played a marginal role behind the camera, Marvā Nabīlī (b. 1941) made the film The Sealed Soil (Khāk-i sar bih muhr, 1977). Nabīlī shot this film over six days, with a small crew, in the village of Qal‛ah Nūr-‛Asgar in southwest Iran. After finishing, she left Iran, and the work was never screened inside the country.1Hamid Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema. Volume 2: The Industrializing Years, 1941–1978 (Duke University Press, 2011), 374-375.

This film holds a special place in the Iranian New Wave. With it, Nabīlī not only emerged as a female director but also brought a female character to the center of the narrative—a rare subject for that period—while simultaneously embracing formal experimentation and moving away from classical narrative structures. This experimental approach is evident in her adoption of Slow Cinema’s characteristics, a style that enabled her to develop a new cinematic language.

Slow Cinema is a stylistic current within experimental cinema that contrasts with the fast-paced rhythm and quick tempo of mainstream cinema.2The term “cinema of slowness” was first used by the French film critic Michel Ciment in 2003. He identified filmmakers such as Béla Tarr, Tsai Ming-liang, and ʿAbbās Kiyārustamī as prominent examples of this movement. The term was later discussed theoretically by Matthew Flanagan in 2008, gaining broader recognition in film studies. This mode of narration emphasizes stillness and contemplation and has become more prevalent in the works of filmmakers in recent decades, with a familiar set of shared formal features: Long takes, simple narratives, and a focus on silence and everyday life. Matthew Flanagan, one of the first scholars to study Slow Cinema, regards slowness as a key feature that shapes a unique aesthetic through the repetition of these stylistic elements. From his perspective, Slow Cinema provides a visual experience that disconnects the viewer from fast-paced culture, refreshes narrative expectations, and aligns the body and senses with a slower rhythm. In the absence of rapid images and sudden stimuli, which dominate much of commercial cinema, the viewing experience becomes akin to a calm and panoramic reception. Long takes allow the viewer to move freely within the frame, making it possible to observe details that, in faster-paced narratives, are often overlooked or conveyed only implicitly.3Matthew Flanagan, “Towards an Aesthetic of Slow in Contemporary Cinema,” 16:9, no. 29 (November 2008), accessed August 29, 2025, www.16-9.dk/2008-11/side11_inenglish.htm.

Flanagan’s definition of Slow Cinema and the aesthetic features he describes form the basis of this article. However, to develop and complete our argument, we will also incorporate the views of others—those who move beyond aesthetics. This article argues that The Sealed Soil fits within Slow Cinema and uses its features to offer a unique experience of narration and time. By downplaying classical narrative tools like dialogue, dramatic acting, and close-up shots, the film diminishes linear and causal storytelling. Instead, by focusing on long takes and the detailed depiction of the main character’s daily life as a rural woman, it highlights moments that are often seen as trivial and overlooked. By shifting attention from dramatic elements to non-dramatic shots, the spectator is able to experience the life and struggles of the main character from a fresh perspective.

Figure 2: Marvā Nabīlī (director) and Filurā Shabāvīz (actress portraying Rūy’bakhayr) during the production of The Sealed Soil (Khāk-i Sar bih Muhr), 1977.

The Sealed Soil and Slow Cinema (in the Iranian New Wave)

In the 1970s, a group of directors from the Iranian New Wave began experimenting with a distinct style and approach, which can be identified within the framework of Slow Cinema. This style distinguishes itself from the dominant current of commercial cinema, as well as from other works of the New Wave, through features such as a slow rhythm close to real time, the use of long and often static shots, an emphasis on ordinary moments and details of everyday life, the reduction or removal of dialogue and complex or suspenseful narratives. Among the directors of this style are Suhrāb Shahīd-Sālis and ʿAbbās Kiyārustamī, each of whom played an important role in expanding it. As this article argues, Marvā Nabīlī, with her film The Sealed Soil, also stands among the filmmakers of Slow Cinema.

According to Hamid Naficy, Suhrāb Shahīd-Sālis’s forced exile, his long, dark, and dystopian films, his strict personality and working style, and the Eurocentrism in film studies during the 1980s and 1990s, all prevented him from being recognized as one of the pioneers of Slow Cinema today. Nevertheless, he includes Shahīd-Sālis in the large group of filmmakers associated with this style.4Hamid Naficy, “Slow, Closed, Recessive, Formalist and Dark: The Cinema of Sohrab Shahid Saless,” in ReFocus: The Films of Sohrab Shahid Saless – Exile, Displacement and the Stateless Moving Image, ed. Azadeh Fatehrad (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2020), 8-9. Shahīd-Sālis’s films often display features typical of Slow Cinema: a slow rhythm, a static camera with long takes and wide shots, and a focus on everyday lives of ordinary people. The setting or environment feels limited or confined, and time seems to move very slowly or feel stagnant. His first feature film, A Simple Event (Yak ittifāq-i sādah, 1973), explores the daily life of a schoolchild in Bandar Shah, with early signs of his realist-minimalist and slow style. In his next film, Still Life (Tabīʿat-i bījān, 1974), this style becomes more pronounced and is evident through a precise focus on the details of an old switchman’s life and that of his family. Time unfolds at a slow pace, with minimal dialogue and modest set design, complemented by repetitive shots, collectively establishing the filmmaker’s distinctive style. Extended and meticulously crafted scenes, such as the nine-minute sequence depicting the daily life of the elderly couple—including actions like eating, drinking tea, smoking, clearing the table, spreading bedding, turning off the lamp, and going to sleep—encapsulate all the defining features of this style. The same style can also be observed in Shahīd-Sālis’s films from his exile period, although in a darker atmosphere. For example, in Far from Home (Dar qurbat, 1975), the film focuses on the daily life of a Turkish migrant worker in Germany, showing ordinary activities like working in a factory and living in a shared house. With limited dialogue and a simple story, it creates a minimalist and calm mood. The long takes and slow rhythm of the film reveal distinctive features of Iranian Slow Cinema.

Figure 3: Still from the film Still Life (Tabīʿat-i bījān), directed by Suhrāb Shahīd-Sālis, 1974.

Although Shahīd-Sālis never attained the fame and recognition he deserved, his filmmaking style influenced a new generation of filmmakers such as ʿAbbās Kiyārustamī. He paved the way for notable global examples of slow cinema, several of which Kiyārustamī later produced. In Kiyārustamī’s view, the significance of this type of cinema, which stretches time, is that it encourages the viewer to actively engage with the film. Kiyārustamī states: “I believe in a cinema which gives more possibilities and more time to its viewer; half-fabricated cinema, an unfinished cinema that is completed by the creative spirit of the viewer, [so that] all of a sudden we have a hundred films.”5Mehrnaz Saeed-Vafa and Jonathan Rosenbaum. Abbas Kiarostami: Expanded Second Edition (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2018), 28-29. Therefore, rather than focusing on dramatic events, Kiyārustamī creates a space where the audience can pause and observe details.

The traces of this tendency can be seen in his 1970s films, such as The Passenger (Musāfir, 1974), with its focus on everyday life and the use of non-professional actors. This approach gradually matured, manifesting in long, non-dramatic shots and a reduction in narrative action, as seen in Taste of Cherry (Taʿm-i gīlās, 1997), where the characters’ movement and the narrative are slow and limited. The main character is seen mostly driving or sitting still, and there are only few dramatic movements or external actions. Life and Nothing More (Zindagī va dīgar hīch, 1992) also focuses on daily life in a region damaged by the earthquake and displays it through long takes and a slow rhythm. One of the most striking examples of Slow Cinema in Kiyārustamī’s work is Five Dedicated to Ozu (Panj bardāsht-i buland taqdīm bih Ozu, 2003), which consists of five long, static takes, each lasting several minutes. In these shots there is no linear narration, no character development or dialogue, and the main focus is on the direct experience of space and time. The takes show simple and everyday images of a natural environment and the shores of the Caspian Sea: the film begins with a shot of a piece of wood that the waves carry away and eventually break, and ends with the reflection of the moon in the water and the sound of frogs and rain. In this world, all elements—sea, wood, dogs, ducks, and even humans—stand on an equal level, and humans appear only in passing, without a superior position compared to other creatures. A key feature of these takes is the absence of cuts, which in turn reduces the filmmaker’s direct intervention. Each take, with its length and pause, provides an opportunity for the viewer to observe and experience the details of the environment and the calm flow of the shots.

Figure 4: Still from Five Dedicated to Ozu (Panj bardāsht-i buland taqdīm bih Ozu), directed by ʿAbbās Kiyārustamī, 2003.

It is worth noting that some argue films from the late 1970s marked a shift in the New Wave towards symbolism, distancing themselves from social issues and creating a gap between the film and its audience, as discussed in an article in Farābī Film Magazine about the films of this period:

“…The New Wave represents a period of artistic maturity in Iranian cinema, quickly gaining cultural credibility over five to six years. It moved towards more contemplative aspects, distancing itself from the mainstream of Iranian cinema… With a shift towards symbolism, these filmmakers replaced the explicitness of the earlier period with more introspective approaches. Some works from the later years, such as Still Life (Tabīʿat-i bījān), The Stranger and The Fog (Gharībah va mih), and The Mongols (Mughūlhā), despite their artistic value, lose their audiences due to their sense of distanciation and allegorical treatment. The primary audience for these films consisted of critics and festival goers…”6Rizā Durustkār, “Mawj-hā va Jariyān-hā-yi Aslī-yi Sīnimā-yi Haftād-Sālah-yi Īrān [The Waves and Main Currents of Seventy Years of Iranian Cinema],” Fārābī Magazine 37 (Summer 2000): 28-29.

Such criticisms overlook the fact that filmmakers of Slow Cinema observe local and global issues with obsessive precision, but never offer simple, ready-made, and formulaic interpretations. Instead, they patiently and attentively observe everything—whether important or trivial. This slow style challenges not only established cultural values—what is worth showing and how much—but also asks what deserves our attention and patience as spectators and humans, and what our time and how we spend it truly mean.7Tiago de Luca, and Nuno Barradas Jorge, “Introduction: From Slow Cinema to Slow Cinemas,” in Slow Cinema, ed. Tiago de Luca and Nuno Barradas Jorge (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2016), 14.

At its core, Slow Cinema redefines what should be shown, how it should be shown, and for how long. This redefinition is evident in the films’ focus on marginalized individuals and themes: by bringing them to the center of the frame and employing long takes with meticulous detail, the films invite the viewer to engage with the images through sustained attention and patience. As Flanagan argues, the unique style of Slow Cinema often emerges from places impacted by globalization, or from those that have not kept pace with its rapid changes. These filmmakers’ works mostly focus on marginalized people living in remote or overlooked places. According to Flanagan, these films emphasize aspects of life and activities that have been overlooked or suppressed as a consequence of significant economic and societal changes.8Matthew Flanagan, “‘Slow Cinema’: Temporality and Style in Contemporary Art and Experimental Film” (PhD diss., University of Exeter, 2012), 118. One might analyze the portrayal of migrants and villagers in Shahīd-Sālis’s works, nature in Kiyārustamī’s films, and, following the same logic, rural women and domestic activities in Marvā Nabīlī’s The Sealed Soil. In these works, individuals and objects are depicted as having remained outside the major currents of modernization. In Slow Cinema, characters who are often overlooked or deemed insignificant in commercial and classical films are brought to the forefront, presented with precision and over extended periods of time.

1. Decentralization of Narrative

The film tells the story of Rūy’bakhayr, an eighteen-year-old girl from a village called Qal‛ah Nūr-ʿAsgar. The time of her marriage has come, and though suitors arrive, she refuses to accept them. At the same time, the village faces change as an agricultural company plans to buy the villagers’ homes, forcing them to sell their livestock and relocate to a newly built township. Rūy’bakhayr’s sister and other children of the village go to school in the township, and their lifestyle has changed. Rūy’bakhayr faces increasing pressure from her family and the villagers to get married soon and accept the new way of life. Under pressure, Rūy’bakhayr is overwhelmed and reaches the breaking point. The villagers, thinking she is possessed, hold an exorcism ceremony for her. In the end, Rūy’bakhayr yields to the wishes of the villagers.

The film begins after Rūy’bakhayr has already rejected her suitors, and this is widely known. Through brief dialogues, past events are revealed, gradually unfolding the plot, which can be summarized as follows. In the opening shots, we see Rūy’bakhayr at home, surrounded by her family, which helps the viewer understand both her character and her environment. The focus then shifts to her relationship with her younger sister, Gulābatūn, and the modern lifestyle that has entered her life through education. We also learn about Rūy’bakhayr and the issue surrounding her marriage. Although marriage is expected at this stage of her life, she refuses to conform to this expectation, turning down the men who propose to her. In the following scenes, as the kadkhudā arrives in the village, we learn more about the events that begin to unfold. Along with the villagers, we learn that an agricultural company plans to purchase their homes and that modernization is sweeping through the village. We also witness Rūy’bakhayr’s resistance to these changes. As the story unfolds, the pressure on her marriage intensifies, and her withdrawal from the community culminates in a nervous breakdown and tears, ultimately leading to an exorcism ceremony. In the final stage of the film, Rūy’bakhayr, together with the women of the village, burns her former clothes in the tanūr (furnace). This act marks the end of her personal rebellion against the village’s traditions, after which she submits both to her suitor and to the modernizing forces sweeping through the village.

This film presents a duality. On one hand, the official narrative follows a deterministic causal framework, where Rūy’bakhayr’s resistance falters, and her suppressions lead to the expected outcomes. On the other hand, as we will explore, the film shifts focus away from the central narrative and its triumphant characters, directing the camera instead to scenes featuring Rūy’bakhayr that are stripped of dramatic weight. It is through these scenes that her character gains significance, overshadowing both her failure and her doomed fate.

At the level of the plot, therefore, the suppressors are powerful: they exert pressure on Rūy’bakhayr, succeed within the narrative, and ultimately break her resistance. But on a visual level, they seem almost insignificant. Nabīlī doesn’t grant them real presence—meaning continuous visibility, sensory weight within the shots, or any notable attention from the camera. The villagers, like secondary characters in the plot, pass through the frame, but they are not central to the film’s cinematic experience.

To achieve this, Nabīlī employs the techniques of Slow Cinema. First, the centrality of the narrative—comprising two key elements: social pressures for marriage and the compulsion to embrace a modern lifestyle—is diminished, reducing their influence on the film. This is achieved first through the use of long and full shots, as well as by obscuring the characters’ faces. Second, the exaggerated, emotional acting typical of narrative-driven films is eliminated. Dialogue, which typically conveys the plot alongside acting, is also significantly reduced, allowing the audience to focus more on the visual experience and the mise-en-scène.

In scenes with multiple characters, the film uses group shots, avoiding close-ups and shot/reverse shots.9These are all characteristics of Slow Cinema: editing or cuts are typically minimal in these films, reducing temporal and spatial disruptions, while long shots often take precedence over close-ups. See Ira Jaffe, Slow Movies: Countering the Cinema of Action (New York: Wallflower, 2014), 3; Flanagan, “‘Slow Cinema’: Temporality and Style in Contemporary Art and Experimental Film” (PhD diss., University of Exeter, 2012), 63. As a result, not all characters are clearly visible. In classical cinema, all characters are typically in focus, with their faces clearly visible to convey the story’s details and relationships. In contrast, this film obscures many characters’ faces, disrupting the conventional approach to character presentation. Moreover, despite living in a shared space, Rūy’bakhayr remains distinct from the others, who are portrayed as secondary figures with minimal cinematic presence.

An example of this approach is seen in a wide shot where Rūy’Bakhīr and three village women are washing dishes in the river, discussing how Rūy’Bakhīr’s time for marriage has passed. Three women are grouped together in the background, dressed in identical dark red clothing, the uniformity of which diminishes their presence. Their role is more that of background figures than active characters with cinematic presence. Rūy’bakhayr, on the other hand, is placed in the foreground, positioned on the left side of the frame, separate from the group. Her position gives her a stronger cinematic presence (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Rūy’bakhayr and the village women washing dishes in the river. Still from The Sealed Soil (Khāk-i sar bih muhr), directed by Marvā Nabīlī, 1977.

In another shot, the kadkhudā arrives at the parents’ request to pressure Rūy’bakhayr into marriage. Although these characters hold power or authority within the story, their visual presence on screen—through how they are placed, framed, or shown in the mise-en-scène—does not emphasize that power. Their faces are either turned away from the camera or shown in profile or three-quarters, with low visual clarity. Visually, they appear almost insubstantial. In contrast, Rūy’bakhayr takes center stage in the frame, with the cinematic focus shifting to her. The parents, dressed in light and earth-toned clothing, blend into the clay-colored background of the house, while the kadkhudā, in his white shirt and dark trousers, sits at the edge of the frame. Their colors neither contrast with nor stand out against the background. Rūy’bakhayr, however, is positioned at the center of the frame, her red scarf contrasting sharply with both the background and the others’ clothing. This distinction, coupled with the relative clarity of her face, allows her visual presence to dominate the scene (Figure 6). Therefore, in the story, those who collectively oppose Rūy’bakhayr occupy a distinctively lower position at the visual level.

In addition to the pressures of marriage, she is also under pressure to follow a modern lifestyle. This pressure is also evident in the story itself, driving the plot and shaping her struggles. However, in the film’s visual presentation they are portrayed in a restrained, distanced, or understated manner, rather than being forcefully thrust into the viewer’s eyes. The long shots of the school and the township convey this logic. In the story, the establishment of the school and the township, along with the arrival of the teacher, marks a turning point, illustrating how state-backed modernity enters the village and ushers in social and gender changes. Yet, on the visual level, the film deliberately suppresses the dramatic potential of this event. The camera maintains its distance: children rushing toward or returning from the school in the township are captured in static, long shots that withhold any narrative intensity. These frames are set against a simple, carefully controlled backdrop: a small structure resembling a guardhouse or official gateway, a barrier demarcating the township’s boundary, a handful of concrete buildings in plain modernist style, and electricity poles strung with wires—all signs of state and industrial infrastructure placed in the heart of the village. The camera’s perspective is restricted, never showing beyond the boundary of the township. Rūy’bakhayr’s movements are consistently directed away from the township, toward the forest. Even at the end, when she finally heads towards the township, the camera remains behind, preventing the viewer from witnessing her entry. Choosing the forest path represents a deliberate escape from the chaos of modern life, highlighting a space that feels calmer and less influenced by its rush and distractions.

Moreover, the performances, instead of merely advancing the narrative, take on a different function, serving to diminish the narrative’s centrality. The actors avoid dramatic performances, with their faces and bodies often displaying minimal expression.10This is also a characteristic of Slow Cinema: the main characters are typically emotionally restrained, or at least limited in terms of expression and movement. See Ira Jaffe, Slow Movies: Countering the Cinema of Action (New York: Wallflower, 2014), 3; Matthew Flanagan, “‘Slow Cinema’: Temporality and Style in Contemporary Art and Experimental Film” (PhD diss., University of Exeter, 2012), 63. As a result, the audience experiences the scene through silences, the surroundings, and the unfolding of long takes, rather than through the characters’ emotions or dramatic reactions. The actors’ performances emphasize the spatial and compositional design of the scene—through camera placement, movement, and the use of the environment. These cinematic and spatial elements become the audience’s primary focus, shifting attention away from the characters’ inner emotions or dramatic actions. This neutral and understated style of acting, in contrast to the passionate and energetic performances typical of conventional cinema, makes the portrayal feel distant and controlled, lending the scene a cooler, more measured tone. Nabīlī uses non-professional or inexperienced actors (with the exception of Filurā Shabāvīz) to capitalize on “the naturalness” of their gestures and behaviors, reducing the artificiality often present in professional acting. For example, in the shot of the kadkhudā speaking, the audience can clearly see that the teacup is empty as he lifts it to his lips.

Figure 6: Kadkhudā urging Rūy’bakhayr to marry. Still from The Sealed Soil (Khāk-i sar bih muhr), directed by Marvā Nabīlī, 1977.

It is clear that Nabīlī was influenced by Robert Bresson, a pioneer of slow cinema, who avoided exaggerated emotions, theatrical looks, and flashy effects in his films.11From an interview with Marvā Nabīlī by Yaldā Ibtihāj, published in Cahiers du féminisme.

Instead of relying on extended shots, Robert Bresson employs editing and short takes. The slowness in his films thus emerges not from shot duration, but from rhythm, silence, stillness, and the actors’ restrained performances. This means that quantitative measures like the average shot length (ASL) cannot explain the slowness in Bresson’s cinema; his slowness is a qualitative aspect shaped by the visual style and the structure of the film. See Tiago de Luca, and Nuno Barradas Jorge, “Introduction: From Slow Cinema to Slow Cinemas,” in Slow Cinema, ed. Tiago de Luca and Nuno Barradas Jorge (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2016), 6. The conventional acting style, in which performers rely on exaggerated emotions to “become” a character, is deliberately set aside. Instead, non-professional actors are employed, simply living the scene rather than performing theatrically. By removing exaggerated gestures and artificial acting, the film aims for authenticity and simplicity, so the characters appear natural on camera rather than performing for an audience. As a result, this type of cinema gradually distances itself from classical narrative storytelling: “No actors. (No directing of actors). No parts. (No learning of parts). No staging. But the use of working models, taken from life. BEING (models) instead of SEEMING (actors). HUMAN MODELS.”12Robert Bresson, Notes on the Cinematograph, trans. Jonathan Griffin (New York: Urizen Books, 1977), 1-2.

Dialogue, which in classical cinema is an important tool for conveying the narrative and revealing relationships and motivations, is marginalized in this film. The characters’ speech is severely limited or entirely omitted, so that narrative information is conveyed less through conversation. With less dialogue, the audience shifts focus from the story to the images themselves—such as the film’s atmosphere, camera movement, silence, and the details of the scene. The film’s power doesn’t primarily stem from dialogue or narration. Instead, it arises from the duration of scenes (time) and how characters and their surroundings are portrayed within the space (spatial presence). In other words, the viewer experiences the story more through visual and spatial elements than through words or direct storytelling.

In one scene, Rūy’bakhayr and her mother are seated in the yard, engaged in daily chores. The mother then gets up and goes inside. In the subsequent medium shot, the father and mother appear together, yet neither of their faces is visible: the father looks down while smoking a cigarette, and the mother turns toward him with her back to the camera. The way these characters are presented—slouched and with their faces hidden—makes it difficult for the audience to connect with them directly. Nevertheless, their body language and the scene itself convey that a serious conversation is taking place. The mother closes the door, and Rūy’bakhayr, working outside, seems to realize that the conversation is about her. We understand this as well, but remain outside with her, unable to hear what the parents are saying. Like many other scenes, the film keeps conversations brief and minimal.

In this section, we have primarily discussed the film’s negative aspects. On a more positive note, we see that, instead of relying on engaging dialogue or a linear narrative, long, non-dramatic shots take center stage. Just as Rūy’bakhayr opts for the quiet forest path over the town, Nabīlī, deliberately eschews speed and haste in her filmmaking. In contrast to films structured around the fast pace of modern life, she embraces slow time, a temporality freed from the pressures of modernity. This creates an experience that resists the conventional urge to rapidly follow the unfolding narrative. The film isn’t about hurrying through events or rushing the story forward. Instead, it’s about experiencing and appreciating time itself. The long, serene shots of Rūy’bakhayr clearly illustrate this: rather than emphasizing movement or dramatic action, the film makes time the central focus, allowing the audience to feel its passage and presence.

2. Long Non-Dramatic Shots

As previously noted, the film’s narrative is diluted through the marginalization of classical acting and staging, the reduction of dialogue, and the de-emphasis of characters who ultimately “succeed” in the story. One of the key reasons the film deviates from a traditional, story-driven approach is its use of long shots depicting Rūy’bakhayr engaging in everyday tasks. These shots don’t push the plot forward, so the audience’s attention shifts from following the narrative to observing daily life and the visual composition of the scene. This situation can be understood through the concept of “undramaticness.”

The idea of “undramaticness” comes from André Bazin’s analysis of Vittorio De Sica’s Umberto D. (1952). According to Bazin, the film’s story isn’t built around events or characters, but through a series of everyday moments. None of these moments is more important than the others, and this equal treatment weakens traditional drama: “The narrative unit is not the episode, the event, the sudden turn of events, or the character of its protagonists; it is the succession of concrete instants of life, no one of which can be said to be more important than another, for their ontological equality destroys drama at its very basis.”13André Bazin, What is Cinema? volume II, trans. Hugh Gray (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005), 81.

Flanagan highlights Bazin’s concept of “undramaticness” in slow cinema. According to Flanagan, when dramatic storytelling is pushed aside, things like careful observation, showing everyday life, and creating a sense of time take its place. Classical drama, which focuses on key moments and cause-and-effect stories, is set aside, and cinema shifts to showing everyday life and real-time experiences; moments that gain meaning not from dramatic events, but through their immediate presence and the act of sustained observation.14Matthew Flanagan, “‘Slow Cinema’: Temporality and Style in Contemporary Art and Experimental Film” (PhD diss., University of Exeter, 2012), 99-104.

In The Sealed Soil, many shots extend beyond the narrative framework. While the storyline conveys the events, these shots reveal the nature of the world Rūy’bakhayr inhabits and her existence within it. In these scenes, time feels elongated, and the space in which the action unfolds becomes more perceptible, because long shots capture non-narrative actions or events from beginning to end. By avoiding repeated cuts, these shots allow viewers to observe the full progression of ordinary situations, emphasizing temporality and process over narrative development. This approach breaks events down into smaller sub-events—even micro-events—thereby fully engaging the audience’s perception of real time.

This process begins with the very first shot of the film, which lasts approximately two minutes. In this shot, Rūy’bakhayr awakens and performs a series of routine actions—combing her hair, wrapping a scarf around her head and forehead, putting on her shoes, and leaving the room—all captured in a single, stationary shot. Each of these actions is further subdivided: the movement of the hands through the hair, repeatedly wrapping the scarf around the forehead, and other small details. This layered subdivision allows the viewer to experience each part independently and in real time, transforming the scene from a mere narration of the story into a tangible experience of presence and the passage of time. In this shot, and in similar ones, the film operates in contrast to the “art of ellipsis” in classical cinema,15For the art of ellipsis, see André Bazin, What is Cinema? volume II, trans. Hugh Gray (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005), 81. where portions of narrative or event time deemed “unnecessary” or “repetitive” are cut or omitted, leaving only the key moments essential for advancing the story. The Sealed Soil, as a film within the slow cinema tradition, dwells on moments that are often omitted in other films. The film repeatedly captures Rūy’bakhayr’s walks as she performs her daily tasks through the use of long takes.16Flanagan has termed films that emphasize ordinary moments—particularly the walking of characters—rather than classic plot complication and resolution, as “walking films” (Cinema of Walking). This approach represents a form of slow cinema and de-dramatization rooted in European modernism of the 1950s and 1960s. In such films, the extended duration devoted to the simple movement of characters disrupts the traditional dramatic structure and directs the viewer’s attention to the experience of time and space. Long takes that accompany characters, capturing subtle changes in their bodies, lighting, and environment, transform time into a central element of the narrative, creating a sensory and contemplative experience. See Matthew Flanagan, Matthew Flanagan, “Towards an Aesthetic of Slow in Contemporary Cinema,” 16:9, no. 29 (November 2008), accessed August 29, 2025, www.16-9.dk/2008-11/side11_inenglish.htm.

In a five-minute scene, she leaves a room, and the camera—which remains mostly stationary throughout the film—follows her with a pan. She moves from one room to another within the courtyard, carries rice, and sits in the yard to prepare it for cooking. Then, she rises and balances a tray on her head as she walks towards the village gate. In the next shot, the camera is positioned outside the village gate, and Rūy’bakhayr slowly approaches from a distance and passes through it. The use of long takes and minimal cuts in these shots—and similar ones—creates a slow rhythm and continuity of real time, compelling the viewer to pay attention to small details in her movements, sounds, and environmental changes (Figures 7-8).

Figure 7: Rūy’bakhayr sitting in the yard, preparing rice for cooking. Still from The Sealed Soil (Khāk-i sar bih muhr), directed by Marvā Nabīlī, 1977.

Figure 8: Rūy’bakhayr passing through the village gate with a tray on her head. Still from The Sealed Soil (Khāk-i sar bih muhr), directed by Marvā Nabīlī, 1977.

Her path after leaving the gate takes her to the forest on the edge of the village, where she collects branches and leaves. In this space, the film introduces moments that don’t necessarily advance the narrative but are among the most striking. These scenes transform the long shot into a sensory and contemplative experience, drawing the viewer into the atmosphere. She returns repeatedly to the forest by the river to gather branches and leaves, and with each visit, the film offers a chance to observe the subtle details and the natural passage of time and life.

The first time, she is working, but along the way, she loosens her head scarf, sits briefly, and takes a short moment of reflection—a minor pause in the regular rhythm of her actions. She then carries the leaves on her shoulder, walking past vehicles along the roadside, before returning to the village in a long take, passing through the gate once more. (minutes 31–35).

After becoming aware of a new suitor, she angrily ties her scarf around her waist and leaves the village again to gather branches and leaves. Her departure from the house is captured in a long take. Upon reaching the forest, she removes her headscarf (Figure 9) and tosses it aside, letting her hair fall free. This moment marks a clear rupture in her daily rhythm, becoming more pronounced (minutes 42–45).

Figure 9: While working in the forest, Rūy’bakhayr removes her headscarf, letting her hair fall free. Still from The Sealed Soil (Khāk-i sar bih muhr), directed by Marvā Nabīlī, 1977.

The climax of these ruptures comes when the pressures of marriage intensify. Rūy’bakhayr lies in nature, feeling the rain. She raises her hands, removes her scarf, and lets her hair fall free. She takes off her long, heavy dress, becomes bare, and moves her body gently under the rain (minutes 53–57). Up to this point, Rūy’bakhayr has always been seen in long, loose clothing that conceals the shape of her body. The cinematography, maintaining distance, highlights this sense of coverage. In the scene where she removes her clothes, however, we are confronted with a moment starkly different from anything we have seen before (Figure 10). In this shot, Rūy’bakhayr’s body becomes part of the environment, blending with the rain and the forest. These elements are not just background; they shape how she exists in the space and the feelings she expresses. She sits with her back to the camera, and her body no longer acts as an object of desire, but blends into the image itself. The lack of dramatization makes this effect clear: the long duration and stillness of the shot, where “nothing happens,” separates the body from its role in driving the drama and shifts the focus from the body as a central, active part of the narrative to something that’s simply observed in the moment. The camera neither moves closer nor fragments her body; instead, it keeps its distance and stillness, placing her within time and space.

Figure 10: As the rain begins, Rūy’bakhayr removes her dress. Still from The Sealed Soil (Khāk-i sar bih muhr), directed by Marvā Nabīlī, 1977.

3. Poetic Justice of the Mise-en-scène17The term is derived from Jacques Rancière’s analysis of Béla Tarr’s cinema. He believes that the poetic justice of the mise-en-scène means that even when, at the level of the story, power and victory belong to the schemers, the mise-en-scène and visual language of the film reverse this equation: the schemers appear insignificant and hollow, while the victims and marginalized characters—such as Valuska and Eszter in Werckmeister Harmonies (2000)—become the center of attention, powerful, and dignified. In this way, the film, through its imagery and rhythm, grants new value and stature to those who have been defeated or pushed to the margins in the narrative, and allows the viewer to feel their dignity and potential. See Jacques Rancière, “Béla Tarr: The Poetics and the Politics of Fiction,” in Slow Cinema, ed. Tiago de Luca and Nuno Barradas Jorge (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2016), 245–260.

Throughout the film, we see the pressure from the villagers on Rūy’bakhayr to marry and accept modern life gradually increase. In the end, she gives in to these pressures, which is clearly shown in the final scene: Rūy’bakhayr sets aside the branches and leaves she has collected, enters the kitchen in the yard, brings a tray and a pot, and begins preparing the rice. Her mother sits beside her, kneading dough, and talks about the suitor who is expected to arrive. Rūy’bakhayr responds that she has no objection. She then puts the rice in the pot, adds water, and continues with similar tasks. Finally, she places the pot on her head and, in a long take, walks toward the gate; the camera, positioned outside, follows her. This time, however, she is heading not towards the forest, but towards the township she had previously avoided. The static camera watches her from behind as the film ends. In this way, her submission to the pressures of the villagers and the modern way of life is unveiled through the seemingly ordinary moments of her daily routine.

The story concludes with her submission, yet the film’s form—through the establishment of a kind of poetic justice—transforms the meaning of her defeat. Poetic justice is a concept in literary criticism where the outcome of a story brings a moral balance, with characters receiving rewards or punishments that match their actions. However, there is another kind of justice in cinema, which can be called the poetic justice of the mise-en-scène.18Here, mise-en-scène refers to the deliberate organization of visual, spatial, and temporal elements in a film, which conveys meaning, impact, and the agency of characters beyond the narrative. This includes the arrangement of characters, objects, and settings; the rhythm and duration of actions; and the precise composition of movement within the frame. Jacques Rancière, “Béla Tarr: The Poetics and the Politics of Fiction,” in Slow Cinema, ed. Tiago de Luca and Nuno Barradas Jorge (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2016), 258–260. Unlike traditional narrative justice, this concept refers to using visual and cinematic elements to convey reward or punishment for characters, regardless of the linear storyline. Even when the story shows the oppressors victorious and the victims defeated, which could be called apparent or logical narrative justice, power is redistributed through the mise-en-scène. Even though the victimized characters fail in the story, they stand out through their presence and the meaning of the scenes. By emphasizing their movements, reactions, and experiences, the film enables the audience to perceive their capacities and be affected in a tangible, meaningful way.

As discussed earlier, The Sealed Soil creates a duality between the narrative plot and the lived world of the character Rūy’bakhayr. On one hand, the story is deterministic and exerts intense pressures on her, so that, despite her resistance, she eventually loses her power to act and influence. On the cinematic level, however, she is allowed to affect the frame, time, space, and environment, revealing her ability to move beyond and diverge from the linear narrative and chronological time. Here, time plays a key role in shaping Rūy’bakhayr’s agency. The length of time allows her the opportunity to not merely follow the predetermined plot of the story. This is particularly evident in extended sequences of walking or engaging in everyday tasks, where Rūy’bakhayr is able to step outside the predetermined trajectory of the narrative and forge a new course. From this perspective, time serves as a tool for Rūy’bakhayr to redefine freedom and agency. Within this extended temporal space, she is able to explore alternative ways of being and acting. Even in a story whose conclusion is marked by defeat and submission, she is afforded the opportunity to assert her agency, with justice emerging at the level of cinematic experience.

Conclusion

The Sealed Soil is regarded as a prominent example of Iranian slow cinema. In producing this film, Marvā Nabīlī deliberately set aside many traditional dramatic elements typically associated with classical cinema, such as heavy dialogue, close-ups, and frequent cuts. At the same time, she foregrounded numerous long takes that capture ordinary, everyday moments in the main character’s life, despite the fact that these shots do not directly advance the narrative.

When we view the film as part of slow cinema, we can address critiques of Nabīlī’s stylistic choices, which argue that her “approach may alienate the very audiences whose problems are dealt with in the film. By refusing to communicate with them in a more conventional cinematic language, the film becomes an inaccessible visual experience for an average audience.”19Jamsheed Akrami, “The Blighted Spring: Iranian Cinema and Politics in the 1970s,” in Film & Politics in the Third World, ed. John D. H. Downing (New York: Autonomedia, 1987), 143. However, the significance of this stylistic choice lies in its ability to compel the viewer to engage in a different mode of seeing. In contrast to classical cinema, where audiences passively await incidents or narrative progression, this approach urges them to adopt a new mindset: patience, attention to small details, and an active engagement through sustained observation. The shift in the viewer’s role—from a passive consumer of events to a careful, patient observer—fills the film’s slowness with meaning. Slowness becomes a tool for transforming the act of viewing, and this transformation is only fully realized when the viewer alters how they watch movies. It also opens new avenues for future research, including the question of whether slowness in cinema can serve a political function.20To examine the political potential of slow cinema (specifically the works of Antonioni), see: Roland Barthes, “Dear Antonioni…,” trans. G. Nowell-Smith in his L’avventura (London: British Film Institute, 1997), 67-68; Karl Schoonover, “Wastrels of Time: Slow Cinema’s Labouring Body, the Political Spectator and the Queer,” in Slow Cinema, ed. Tiago de Luca and Nuno Barradas Jorge (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2016), 161.

Society typically dictates the duration and manner in which we attend to objects, people, or events. In other words, the length and type of our attention are regulated by unwritten rules of behavior, forming a part of the social order. When someone focuses on something longer than usual, particularly something socially or aesthetically marginalized, it can challenge established social orders. When attention is prolonged beyond customary social norms, the usual controls over how we observe and perceive can be temporarily suspended, disrupting habitual modes of perception. Slow cinema filmmakers slow down the rhythm of the film and extend shots to encourage this sustained attention. Through slowness, they not only slow the narrative but also challenge social norms and how we typically engage with what we see.

Cite this article

This article explores the characteristics of Slow Cinema in the film The Sealed Soil (Khāk-i sar bih muhr, 1977), focusing on its use of extended long takes to emphasize everyday activities often overlooked in classical cinema. The use of such elements disrupts linear and causal narration, highlighting the character’s lived experience in the immediacy of real time. From this perspective, we argue that The Sealed Soil works through two distinct yet interdependent levels: narrative structure and visual form. In the narrative, the main character (Rūy’bakhayr) tries to make her own life choices against others’ expectations, but the pressures from those around her ultimately force her to conform. This article focuses on the film’s emphasis on Rūy’bakhayr’s continuous visual presence, captured through long takes that document the rhythms of everyday life. In doing so, the film downplays the narrative of Rūy’bakhayr’s defeat, instead highlighting her enduring presence. This process will be analyzed using a formalist approach, focusing on the aesthetic elements of Slow Cinema.