Parviz Goes to College: A 1930s Missionary Film in Context

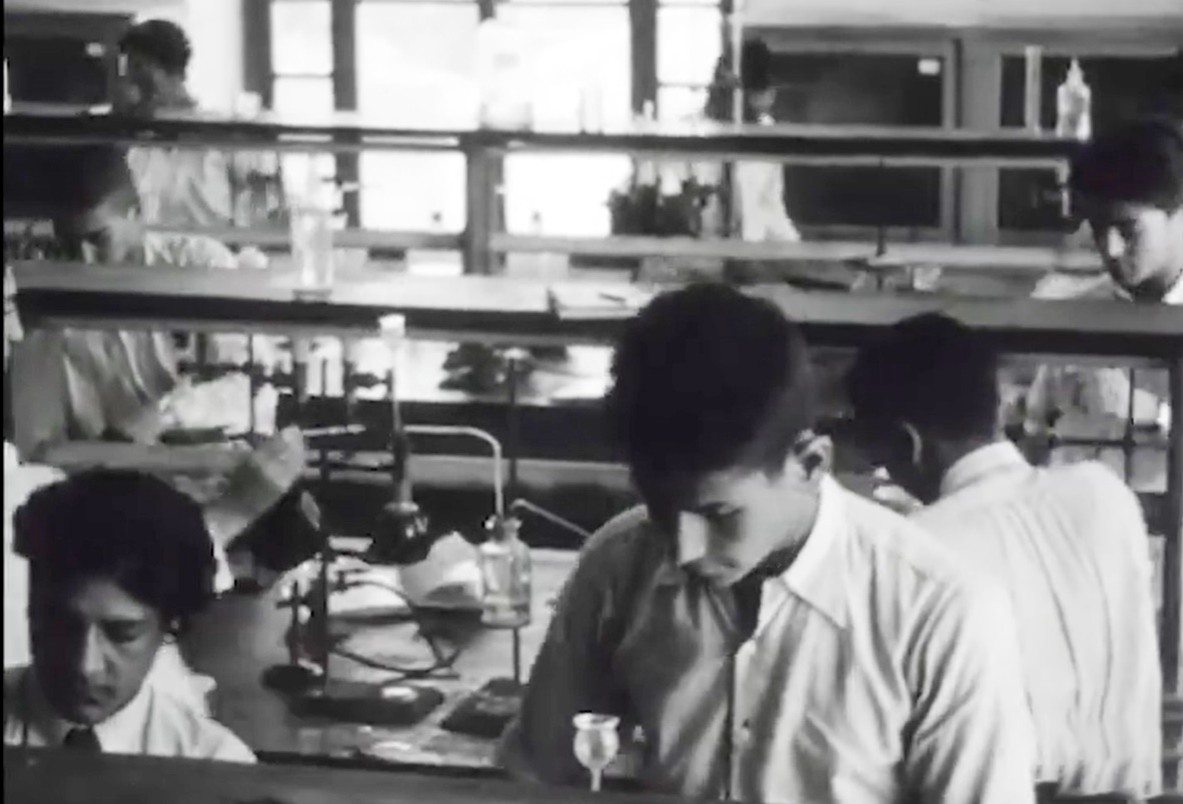

Figure 1: Alborz College, a still from the film Parviz Goes to College, 1932-34

Introduction

This article explores Parviz Goes to College, a 1930s silent film produced by American Presbyterian missionaries at Alburz College in Tehran. Intended both to attract Iranian students and to reassure American benefactors, the film blends staged scenes of school life with documentary-style footage of Iranian society. Close analysis shows that the filmmakers carefully orchestrated the portrayal of modernization and Western influence, while downplaying religious evangelism until the film’s concluding minutes. By examining the film’s production context, technological features, and especially the strategic use of intertitles, including several added in the United States, after initial filming, the article reveals how the film catered to two different audiences and advanced missionary objectives under the guise of promoting education. The article concludes that Parviz Goes to College was not a neutral depiction of reality, but a crafted advertisement designed to reinforce the missionaries’ dual mission of educational modernism and religious conversion. Its significance lies not only in what it shows about Alburz College and Iran’s “modernization,” but also in how it reflects broader patterns of Orientalist framing and missionary self-presentation. By studying this rare example of early missionary filmmaking in Iran, the article contributes to our understanding of the intersections between religion, education, and Western cultural expansion during a pivotal era in Iranian history. This thought-provoking film encourages in-depth analysis; This article will focus specifically on certain visual footage and intertitles that were added later in Philadelphia for a different audience. It will explore how these elements shaped audience perception by strategically appealing to two distinct groups of viewers.

Production Background and Filmmaking Techniques

Parviz Goes to College is a two-reel, 16-millimeter, black-and-white silent motion picture produced in Iran between 1932 and 1934.1Parviz Goes to College. Produced by: Alborz College. Tehran, 1932-34. Black and White. 35min. Digitized by the Presbyterian Historical Society (P.H.S.), Philadelphia, Pennsylvania in 2020. Accessed April 28, 2025.

https://digital.history.pcusa.org/islandora/object/islandora%3A169213. Also available on YouTube: “Parviz Goes To College, about 1930,” posted February 2, 2021, by Presbyterian Historical Society, 34 min., 43 sec., https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=obKIYcPo4KM. The Presbyterian Historical Society (P.H.S.) in Philadelphia digitized the reels in 2020 at the request of Matthew K. Shannon, a history professor and research fellow at Emory and Henry College. The film lacks an opening or closing credit sequence that would typically specify production details and personnel. It appears to have been filmed by a single individual using one camera, either placed on a tripod or handheld for the most part. During the 1930s, Cine-Kodak silent movie cameras were popular among amateurs and American missionaries for their affordability and accessibility.2Joseph Ho, Developing Mission: Photography, Filmmaking, and American Missionaries in Modern China (Cornell University Press, 2022), 95–96. Joseph Ho, a historian of modern East Asia and professor at the University of Michigan, notes that in 1930, a Presbyterian Church in Rye, New York, purchased a Cine-Kodak Model B camera for Harold Henke, a missionary in North China, and his wife, Jessie Mae Henke, to film local scenes and people. These cameras were widely advertised, and Kodak established offices in major cities such as Shanghai, encouraging users to send their films for processing.3Joseph Ho, Developing Mission: Photography, Filmmaking, and American Missionaries in Modern China (Cornell University Press, 2022), 105-6. Given these factors, it is plausible that Parviz Goes to College was filmed using a similar Cine-Kodak camera.

During the production of Parviz Goes to College, Samuel Martin Jordan (1871-1952), a Presbyterian missionary, presided over Alburz College. He and his wife, Mary Park Jordan, were dispatched to Iran in 1898 to establish and manage the school according to the Church’s principles.4Michael Zirinsky, “Jordan, Samuel Martin,” Encyclopaedia Iranica Online,

https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/jordan-samuel-martin/. Similar to the case of Harold and Jessie Mae Henke, it is likely that the Church appointed Samuel and Mary Jordan to manage the camera. Ho includes records that indicate several women missionaries in China were the ones who took photographs and filmed the occasions.5Joseph Ho, Developing Mission: Photography, Filmmaking, and American Missionaries in Modern China (Cornell University Press, 2022), 101–2. It is highly probable that some of the filming was done by Mary.

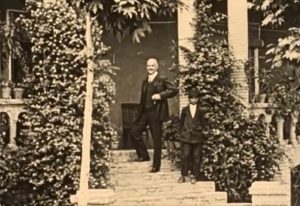

Figure 2: President S.M. Jordan, head of the College, a still from the film Parviz Goes to College, 1932-34

The Dual Audiences: Iranian Families and American Patrons

Shannon describes the film as a promotional piece intended for church benefactors in the United States and, probably, for recruiting students in Iran.6Matthew K. Shannon, “The Iran Mission on Film,” Presbyterian Historical Society Blog, May 16, 2022. Accessed April 28, 2025. https://pcusa.org/news-storytelling/blogs/historical-society-blog/iran-mission-film. Shannon’s newly published book, Mission Manifest: American Evangelicals and Iran in the Twentieth Century (Cornell University Press, 2024), also explores the role of American missionaries in Iran during the 1940s to 1960s. Therefore, the film’s primary audience consisted of donors who funded the Presbyterian Church’s overseas educational activities and Iranian families considering sending their sons to Alburz College. Shannon uncovered several documents showing that, other than in Philadelphia, the motion capture was screened at a church in Pottstown, Pennsylvania, in 1935 and again in 1936 by The Scranton Republican in Scranton, Pennsylvania. Those two churches borrowed the reels from the Church’s office, “in the Witherspoon Building, Philadelphia.”7The institution was originally known as The American Presbyterian College of Tehran (A.P.C.T.), also referred to as The American College of Tehran (A.C.T.). In 1932, it was renamed Alburz College, which is the name we see in this film. American Protestant missionaries began their religious and secular activities in Iran in 1829. Like missionaries from other Western nations and Christian denominations, they were largely unsuccessful in converting Iranian Shiʿi and Sunni Muslims, Jews, Armenians, Assyrians, other Christian sects, Zoroastrians, or other cultural and religious minorities. While the Iranian communities and governments largely disregarded the missionaries’ religious teachings, they did appreciate their contributions to education, technology, and science. The missionaries aimed to demonstrate the superiority of their religion and culture through both their words and actions. Michael Zirinsky, a historian and a student at Alburz College in the 1950s, notes: “Characterizing their secular work as ‘bait for the gospel hook,’ Presbyterian missionaries in Iran sought to improve Iranian access to modern medicine and education.” See Michael Zirinsky, “Inculcate Tehran: Opening a Dialogue of Civilization in the Shadow of God and the Alborz,” Iranian Studies 44, no. 5 (2011): 658. There was probably a second copy kept at the school to recruit students. The version currently available is the one preserved by the P.H.S., and the present copy of Parviz Goes to College suggests that this copy and the one kept at Alburz College were not precisely the same.

Figure 3: A portrait of Parviz, a still from the film Parviz Goes to College, 1932-34

Another possibility is that only a single copy of the film existed, and it was initially shown to Iranian families in Tehran, as well as to the authorities responsible for reviewing and censoring all forms of media. Afterward, this copy was taken to the United States in 1934, where it was revised to include additional footage and intertitles for church patrons. Either way, the existence of two unidentical copies or one revised copy implies that the motion picture was designed to inform and attract two distinct groups of spectators.

The original film focuses on Alburz College as a modernized space, where students have access to Western technologies, advanced teaching methods, and a fruitful upper-class lifestyle. This could encourage Iranian families to send their boys to Alburz College. The promotion of Christianity and gospel lessons is reserved for near the end of the film and is not as extensive as the advertising of Western “modern” education.

The revised copy of the reels sent to the United States and now held by P.H.S. Archives underlines the idea that Iran’s “modernization” was directly attributable to the introduction of Christianity, which was also presented by this particular group of missionaries. Consequently, the funds provided by American patrons were needed to continue the mission. To bring attention to this initiative, the Presbyterian Church enhanced the copy sent to the United States with a new title sequence and additional footage filmed in Tehran. They also included three new intertitles aimed at church patrons, showcasing the missionaries’ success in preaching the gospel and promoting Christianity at Alburz College, and the fact that they still required financial support and prayers from these patrons. Accordingly, the original version, which lacks these elements, downplayed its evangelical mission, focusing instead on highlighting the American missionaries’ contributions to “modernization” and Western education, making the film more appealing to Iranian families, less overtly religious, and acceptable for the Iranian state.

Creating these promotional reels was crucial for Jordan and his team to maintain the school’s operational success, as tuition and donations from parents and American patrons covered expenses. The film emphasizes this necessity by including two illustrative scenes. Approximately one minute of the film is devoted to the visit of a donor, Mrs. Moore. This sequence commences with an intertitle: “Mrs. Moore, donor of Moore Science Hall, leaves Teheran by plane.”8Parviz Goes to College, 00:06:46. Subsequently, she, along with two other women and two men, is shown conversing with Jordan in front of an airplane. Jordan takes Mrs. Moore’s arm and guides her toward the camera, looking directly at the camera and smiling. The following two sequences show Jordan speaking with the three women, assisting them as they board the plane, and again smiling at the camera.9Parviz Goes to College, 00:06:50. The film also indicates that students pay tuition through an intertitle: “Next Parviz pays his fees to Bursar Barseghian and registers with Mr. Chaconas.”10Parviz Goes to College, 00:11:53. In the next sequence, Parvīz meets with Mr. Barseghian, counts several bills, and places them on the table, whereupon Mr. Barseghian provides Parvīz with a receipt.11Parviz Goes to College, 00:12:00.

Even after 1940, when American missionaries were asked to leave Iran during World War II and Alburz College started functioning under the Iranian government, it continued to operate using tuition and donations from students’ parents.12John H. Lorentz, “Educational Development in Iran: The Pivotal Role of the Mission Schools and Alborz College,” Iranian Studies 44, no. 5 (2011): 650. According to Lorentz, the Iranian government forced Jordan and his team to leave Tehran in 1940 during World War II. The official reason given was that Alburz College was situated in a military zone, and the missionaries needed to leave for their own safety. Nevertheless, Lorentz argues that this was essentially a strategic move to reduce the risk of internal rebellion and to reinforce national loyalty. None of the Iranian governments during the reigns of Rizā Shah (1925-1941) and Muhammad Rizā Shah (1941-1979), nor those following the 1979 Revolution, provided funding to the school.13Habib Ladjevardi, Memoirs of Mohammad Ali Mojtahedi (Harvard University Center for Middle Eastern Studies and Oral History Project, 2000), 40-41. Mujtahidī notes the one occasion when the government provided a small fund to cover some expenses during the reign of Muhammad Rizā Shah. Most students came from affluent families, political elites, or the educated upper-middle class. Alburz College offered work scholarships to students under Jordan’s leadership. The students, who were already enrolled in the school, could take jobs and receive payment.14Yahya Armajani, “Alborz College,” Encyclopædia Iranica Online, https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/alborz-college/. And, it offered free education to a few low-income students during Muhammad ‛Alī Mujtahidī’s tenure, with donors covering their tuition at his request.15Habib Ladjevardi, Memoirs of Mohammad Ali Mojtahedi (Harvard University Center for Middle Eastern Studies and Oral History Project, 2000), 30. In a 2000 interview with Habib Lajevardi, Mujtahidī clarified on multiple occasions that parents covered all expenses, that he sometimes solicited donations from wealthy families, and that he explained how these funds were spent during meetings of the Home and School Society (Anjuman-i Khānah va Madrasah).16Habib Ladjevardi, Memoirs of Mohammad Ali Mojtahedi (Harvard University Center for Middle Eastern Studies and Oral History Project, 2000), 48-49. Also, Homa Katouzian, a scholar of Iranian Studies who attended Alburz College in the latter half of the 1950s, mentions the Home and School Society that Mujtahidī initiated, maintained, and “tried to use the wealth and influence of its notable members in the interest of the school.”17Homa Katouzian, “Alborz and its Teachers,” Iranian Studies 44, no. 5 (2011): 745.

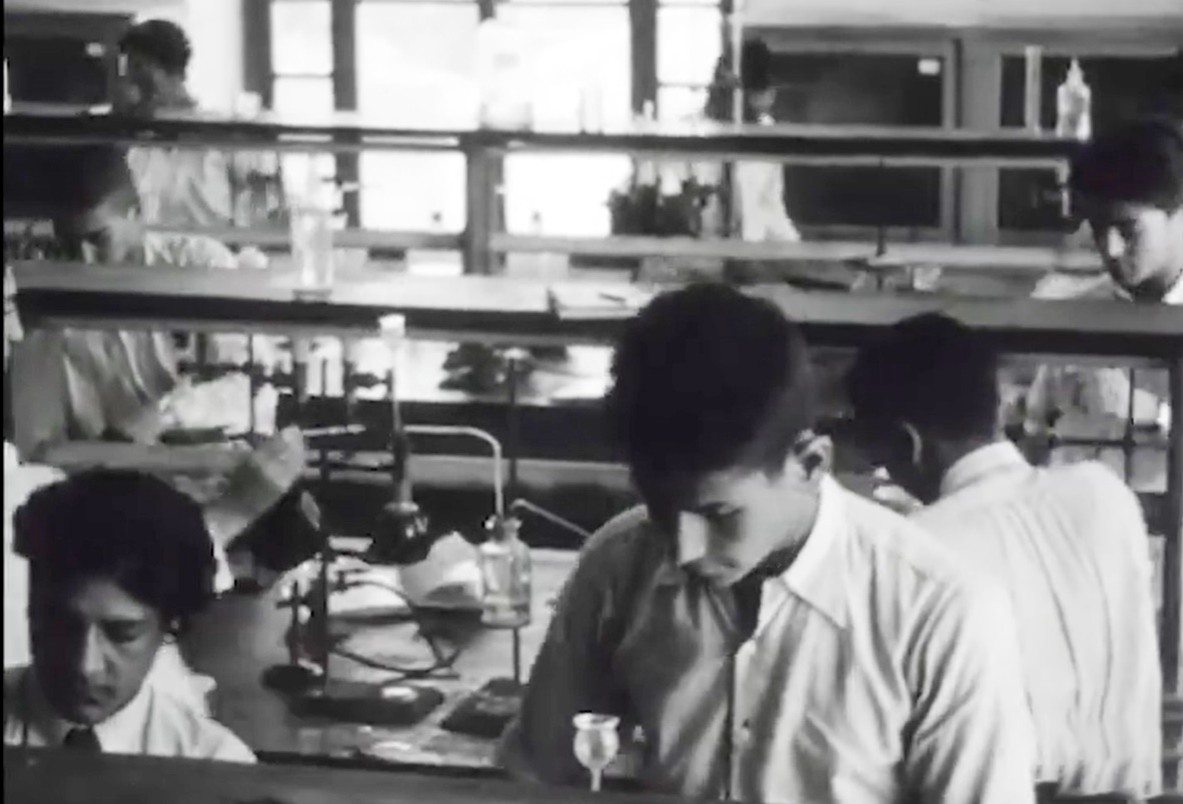

Figure 4: Students in the College laboratory, a still from the film Parviz Goes to College, 1932-34

The Role of Material Culture: Modernization Through Western Technology

The first thirty-one minutes of the film present various locations and people in Iran and illustrate Alburz College as a westernized and sophisticated institution. It showcases the school’s curriculum and the upper-class American Christian lifestyle offered to Iranian male students from families who could afford it.18Yahya Armajani, a member of the Alburz staff in the 1930s, notes that four women graduated with a B.A. from Alburz in 1940. But, he does not provide further details about these women. He writes, “The first graduating class of the elementary school in 1891 numbered five, three Armenians and two Jews. In the last commencement of the college held in 1940 there were 106 junior college graduates, and twenty B.A.s, including four women.” See Yahya Armajani, “Alborz College,” Encyclopædia Iranica Online, https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/alborz-college/.

The camera follows Parvīz, the film’s main protagonist, from his initial entry into the school, shadowing his progression through the registration process. The film proceeds to depict the students’ daily routines, classes, activities, staff, educators, resources, and technologies. It also introduces locations beyond the school’s campus and other individuals.

The film serves as a valuable source of information, offering remarkable examples of architecture, government-regulated and Western-style clothing,19In the film, Iranian men, including a farmworker, are seen wearing Pahlavī hats, which had been declared the official headgear for men by the government during that period. See Elahe Saeidi and Amanda Thompson, “Using Clothing to Unify a Country: The History of Reza Shah’s Dress Reform in Iran,” International Textile and Apparel Association Annual Conference Proceedings 70, no.1 (2013): 31, https://www.iastatedigitalpress.com/itaa/article/id/2160/. For example, at minute 00:02:16, although the poor quality of the surviving footage makes it hard to distinguish facial features, the Iranian driver can be identified by his Pahlavī hat, setting him apart from the European visitors. working-class labor, upper-class privileges, transportation, tourism, Western technologies, and the connotations that missionaries working in the 1930s Iran correlated with terms such as “primitive,” “an awakening land,” and “modern.” In the film, “primitive” is associated with poverty, hardship, and a non-Western lifestyle that many Iranians experienced at that time, whereas “awakening” and “modern” are linked to prosperity and Western practices.

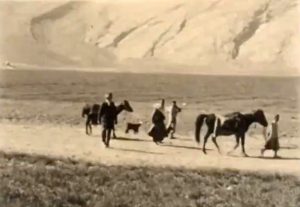

Throughout Parviz Goes to College, instances of what the filmmakers considered “primitive” are evident, most notably in the footage depicting a tribe—likely one of the Bakhtiyāri tribes 20Jordan accompanied a Bakhtiyāri tribe on multiple occasions during their migration.—during its migration. As Hamid Naficy states, “Tribes and their ‘exotic’ ways of life” were one of the most fascinating phenomena for Westerners from the 1920s to the 1970s.21Hamid Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema, Volume 1: The Artisanal Era, 1897-1941 (Duke University Press, 2011), 106-113. Naficy briefly discusses several documentaries made by both Iranian and Western filmmakers about these communities. One of his examples is from the 1970s: “Tribes and their ‘exotic’ ways of life, colorful customs, and arduous annual migrations, which had been memorably documented in the 1920s by American filmmakers Merian Cooper, Ernst Schoedsack, and Marguerite Harrison in Grass, became subjects for Iranian documentarians.” Naficy explains that these documentaries typically focused on the story of one tribe, highlighting their unique cultures. In contrast, Parviz Goes to College does not provide any information about the community featured in the film. Instead, the camera focuses primarily on Jordan, not the tribe itself. The 13th sequence of the motion capture features an intertitle that reads: “President Jordan joins nomads on their spring migration.”22Parviz Goes to College, 00:06:01. This intertitle is immediately followed by a long shot of a small group of men, women, horses, a dog, and a sheep walking and exiting the frame. As they leave the frame, Mr. Jordan separates from the group, approaches the camera, removes his hat, and smiles at the viewers.23Parviz Goes to College, 00:06:10. The inclusion of this community’s migration was sufficiently important for the producers to travel from Tehran to the Zagros Mountains in western Iran, the site of numerous tribal migrations, to capture footage of Mr. Jordan walking with them for a brief duration.

Figure 5: Mr. Jordan approaches the camera, removes his hat, and smiles, a still from the film Parviz Goes to College, 1932-34

In contrast, Western clothing, inventions, machinery, and even the presence of Western tourists and the American staff at Alburz College are presented as indicators of Iran’s “awakening land” and the modernization afforded to upper-class Iranians. For example, the film directs viewers to observe cars and airplanes outside the school, and it explicitly highlights Western equipment and material objects within the school, including a telephone, an electric generator, a recording device, a microscope, a typing machine, lab supplies, a desk lamp, musical instruments, and English-language books. One illustrative example is the chemistry lab supplies and equipment. At the 00:18:03 mark, the intertitle reads: “Parviz majors in Science in Moore Hall.” Next, the film shows students working in a chemistry lab, where jars of chemicals are arranged on tables and shelves. A slow camera pans from left to right displays the room and the students, including Parvīz, at work. The following sequence is a medium shot of Parvīz taking samples and measuring liquid with an advanced scale, followed by a close-up of Parvīz engaged in his experiment.24Parviz Goes to College, 00:18:23.

The Women Behind the Scenes

The couple, Samuel and Mary Jordan, who were instrumental in the making of Parviz Goes College and were behind the camera, also appeared in front of it. However, Mary is almost invisible in this film. According to Michael Zirinsky, Mary was “overshadowed in public by her husband;” and, despite being very active at the school, she often remained in the background and let her husband speak for both of them.25Michael P. Zirinsky, “Harbingers of Change: Presbyterian Women in Iran, 1883-1949,” American Presbyterians 70, no. 3 (Fall 1992): 181-82. In the film, Samuel Jordan appears fourteen times, and except once, always looks directly at the camera and smiles. His major role in leading Alburz College is highlighted in many ways. There is even an intertitle dedicated to him: “Headed by President S. M. Jordan.”26Parviz Goes to College, 00:05:51. Mary, on the other hand, is in five sequences, accompanying her husband in group shots. In another scene, she may or may not be one of the women listening to students performing a music recital.27Parviz Goes to College, 00:23:42. (Figure 1) Zirinsky adds, “Her contributions were of equal importance to the mission enterprise.”28Michael P. Zirinsky, “Harbingers of Change: Presbyterian Women in Iran, 1883-1949,” American Presbyterians 70, no. 3 (Fall 1992): 180-181. Zirinsky wrote: During her forty years in Iran, Mary chaired the music committee of the Evangelical Church in Tehran. She published several writings, initiated after-school events to empower Alborz College students in their non-academic pursuits, and taught singing to interested Iranians. Additionally, she arranged game nights and Sunday school classes at her home for students and hosted evangelistic meetings for Iranian women. Mary also served as an advisor for English textbooks with the Iranian Ministry of Education. When Reza Shah outlawed the Hijab for women, she wrote: “In late years, this outdoor covering has been no hindrance to education or progress, though resented by some … as a badge of ignorance and servitude and an insult to the men of Persia. One of the leaders of what might be called the feminist movement in Persia has frequently said: We are working for the lifting of the veil of ignorance and superstition. The removal of the chuddar is of no great importance.” Yet, even when some of the instructors and staff are introduced in close-up shots of their faces and in intertitles, showing their names and the subjects they taught, Mary, who was the English and Music instructor, is not included.29Parviz Goes to College, 00:19:36.

Apart from Mary, several wives of American instructors and staff were either teaching at Alburz or engaging in activities. For example, Mrs. Boyce, the vice president’s wife, played a key role in the publication of ‛Alam-i Nisvān, one of the first magazines dedicated to women in Iran.30Yahya Armajani, “Alborz College,” Encyclopædia Iranica Online, https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/alborz-college/. Samuel Jordan was a strong advocate for women’s social activism and education. He and Mary decided to involve the wives of the staff as faculty members to demonstrate to their male students that “Girls too can be educated… By the example of husbands and wives working together, and by definite teaching, we have convinced our students… The young men are insisting on educated wives.”31Michael Zirinsky, “Inculcate Tehran: Opening a Dialogue of Civilization in the Shadow of God and the Alborz,” Iranian Studies 44, no. 5 (2011): 662. Despite their significant contributions, none of the women faculty members found themselves in front of the camera in Parviz Goes to College.

Figure 6: Families listening to students’ music recital, a still from the film Parviz Goes to College, 1932-34

Staging and Performance: Fictional Elements in a Promotional Film

Parviz Goes to College should not be considered an observational documentary, as it is heavily staged. It is obvious that the camera operator directs Parvīz and the other participants inside the school to act, perform tasks, smile, and appear delighted. The film was intended as an advertisement for Alburz College. Therefore, like any advertising project, most scenes are theatrical. In some sequences, the participants even look at the camera operator, who guides them through their next actions for a few seconds. Moreover, it is sometimes evident that they are merely pretending. For instance, the student telephone operator pretends to receive phone calls,32Parviz Goes to College, 00:24:53. or Parvīz feigns illness and is taken to the school’s hospice, where another student is lying in bed, looking at the camera and smiling.33Parviz Goes to College, 00:29:52.

The staged nature extends to the step-by-step registration process. The film depicts this process until Parvīz is settled in the dormitory and joins other students in the dining room. The film intends to convince viewers that this process transpired within a single day. Certain details suggest that the filming occurred over several days, that Parvīz was not a new student, and that he was already familiar with the school. Parvīz adheres to the school’s regulations from the moment he enters Alburz College. He produces various documents from his pocket to present to the staff in each room he visits. He is seen in multiple outfits, consistent with the school’s dress code, as observed elsewhere in the film.

Initially, Parvīz is seen wearing a white shirt, a dark hat, a polka dot tie, and a dark jacket while standing in front of the school’s brick wall, already inside the premises.34Parviz Goes to College, 00:09:07. Yet, in the subsequent scene, he enters the school, feigning the demeanor of a new student, dressed in a light jacket and light pants, without a tie, but wearing the same hat.35Parviz Goes to College, 00:10:18. Later, when he is taken to the dormitory, he is wearing light pants and a dark jacket.36Parviz Goes to College, 00:15:55. Parvīz’s glances around Dean Groves’s office also fail to convey the impression that he is unfamiliar with the school.37Parviz Goes to College, 00:13:50. In contrast, the Iranian people filmed in locations outside the school appear unscripted, engaged in daily activities, generally aware of the camera, and occasionally looking directly at it. Therefore, the film should be analyzed as a short fiction, incorporating documentary footage of actual events.

This does not imply that the film presents a false depiction of Alburz College or that its students experienced a dissimilar reality. Based on published memoirs and interviews from both Alburz staff and students, from the school’s inception, Alburz maintained a rigorous curriculum, enforced discipline, and fostered a staff that was both firm and approachable. Katouzian describes the school as an exception compared to many others in Iran: “The generally fair and polite behavior of the students towards one another, and the cordial, if not warm, relationship between teacher and student was far from representative of what went on outside the school, at other schools or in much of the society at large… teachers at the College had been held to exceptionally high standards, and discipline and manners had been strict, although not harsh.”38Homa Katouzian, “Alborz and its Teachers,” Iranian Studies 44, no. 5 (2011): 743. This ethos is palpable in Parviz Goes to College. The friendliness and politeness of the staff, along with a well-rounded curriculum designed to empower students, are palpable in the film.39See, for example, Parviz Goes to College, 00:10:50.

Under the supervision of Jordan (from 1918 to 1940), Muhammad ‛Alī Mujtahidī (from 1941 to 1978), and continuing after the 1979 Revolution, Alburz became one of Iran’s most successful and prestigious educational organizations. It has consistently ranked among the top schools with high acceptance rates at universities in Iran and abroad. Although the school’s location, name, curriculum, and teaching philosophy have undergone several changes, it has remained capable of training highly educated young minds whose academic and professional achievements and contributions continue to be celebrated by the school and by Iranians.40See Khānah-i Alburz, “Alborz House | Khānah-i Alburz,” YouTube video, 7:52, posted September 11, 2016, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DBlUqPdvasU&list=PL1hTDDqomX6voRVuzUafeNhFpsHxH2tmC.

Visualizing Iran: Orientalism and Persophilia in the Film

Another significant aspect of this film is its portrayal of Iran to its American audience. Approximately five minutes of the film show several places and people from different social classes outside the school. This would have provided context for patrons and donors, most of whom had not traveled to Iran and were likely curious about this foreign place. Moreover, this part of the film amplifies the perceived importance of Alburz College in making American Christian values and Western technology accessible in Tehran to those who, from the missionaries’ perspective, were deemed to be in dire need. Yahya Armajani, who appears in Parviz Goes to College and is introduced as the housemaster of Lincoln Hall, recounts a quote from Jordan that attests to the American missionaries’ perspective on Iranians and Jordan’s vision for Alburz College. Armajani writes: In 1906, eight years after Jordan and his wife, Mary, arrived in Tehran, Jordan said in an interview:

The young oriental educated in Western lands as a rule gets out of touch with his home country… Too often, he discards indiscriminately the good and the bad of the old civilization and fails to assimilate the best of the West. He loses all faith in his old religion and gets nothing in its stead… We adapt the best Western methods to the needs of the country while we retain all that is good in their own civilization.41Yahya Armajani, “Alborz College,” Encyclopædia Iranica Online, https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/alborz-college/.

Jordan genuinely cared about his mission; yet the idea of ‘Us’ against ‘Them’ and the ideology promoting the superiority of white Western upper-class over people of color, referred to as “Orientals,” greatly contrasted with his preaching of equality and impartiality. This is stated by Shannon, too. He emphasizes that the film is deeply infused with themes of “Orientalism” and “Persophilia,” crafting an “imagined Iran.”42Matthew K. Shannon, “The Iran Mission on Film,” Presbyterian Historical Society Blog, May 16, 2022. Accessed April 28, 2025. https://pcusa.org/news-storytelling/blogs/historical-society-blog/iran-mission-film. This portrayal gives a thought-provoking look at Iran seen through the Western lens. It shows how Western views shaped ideas about Iran during that time, presenting it as both exotic and artificially constructed.

Religious Messaging: Evangelism Embedded in Modernization

The producers edited the film so that all footage and intertitles related to religion are placed at the end, thereby amplifying the film’s intended message. At minute 19:32, through six consecutive intertitles and close-up shots, the film introduces Professor Farhī, the Persian literature professor, and Professor Nakhustīn, the Arabic teacher, before presenting Dr. Wysham, the religion teacher, whose remarks, which we don’t hear, are much longer than the other two professors. Furthermore, the religious activities at the school are revealed during the final four minutes of the film. Therefore, it becomes evident that the producers intended to emphasize missionaries’ sponsorship of Western education and modernization for both Iranian and American viewers before disclosing their efforts to evangelize the students.

Nevertheless, they needed to convince their supporters in the United States that the mission’s success was attributable to the funding provided by patrons. As a result, the final four minutes of the film, including the three added intertitles, were edited to fulfill this expectation. Armajani explains that the missionaries’ primary objective was to evangelize Iran, but they were unsuccessful. “Hence, they offered the Iranians the ‘best’ of American civilization, which, in their view, was the direct result of Christianity.”43Yahya Armajani, “Alborz College,” Encyclopædia Iranica Online, https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/alborz-college/. This is precisely what is conveyed in Parviz Goes to College. It presents Alburz College’s contributions to westernization, which at the time were considered synonymous with the modernization of third-world countries.

The Added Intertitles: Reframing the Film’s Message

The film was created to present the American missionaries as representatives of modernity, Western technologies and materials as instruments of modernization, and the students as recipients of modernity from its Western Christian architects. To achieve this goal, the film mainly relies on intertitles. The film was produced in the early 1930s, a few years after the beginning of Talkies in 1926,44Unlike silent films, talkie films feature recorded dialogues, monologues, or voiceover narrations that are captured during filming and editing. when films with diegetic and non-diegetic synchronized sound began to gradually replace silent moving images.45Diegetic synchronized sounds are those that originate from within the film’s world, recorded simultaneously with the visuals and directly matching what is seen on screen. In contrast, non-diegetic sounds are added during editing and postproduction, such as voiceover narrations, which come from outside the film’s world. Parviz Goes to College lacks both diegetic or non-diegetic voiceover narration, dialogue, monologue, background sound, or music, which suggests the use of a Kodak camera, as these cameras were unable to record sound before 1937. As a result, storytelling and communication with the audience are delivered entirely through moving images and intertitles. The intertitles are even more critical than the moving images in conveying the film’s purpose and vitalizing its message. Without intertitles, the audience could interpret most visual sequences differently. Intertitles prepare the spectators for what to see, how to see it, and what to contemplate about the visual sequences. Therefore, most serve as more than narrative and descriptive texts, guiding the audience to understand the visual footage from its producers’ standpoint.

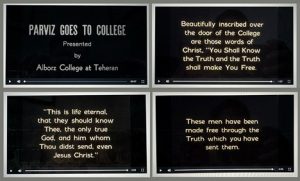

The film has thirty-nine intertitles, a substantial number for a 35-minute short film. The duration of these intertitles ranges from four to eleven seconds, providing the audience with ample time to read each one. Like other silent moving images, a few are descriptive and provide basic information about the setting and theme. Examples include [Alburz College is] “Headed by President S. M. Jordan,”46Parviz Goes to College, 00:05:47. “Prof. Farhi teaches Parviz Iranian literature,”47Parviz Goes to College, 00:19:32. and “Prof. Nakhosteen teaches Arabic.”48Parviz Goes to College, 00:19:49. Nonetheless, the fact that intertitles occupy approximately four minutes of this short project confirms their essential function. Nonetheless, four of these intertitles were added later. Those four consist of the title sequence and three intertitles that appear in the final two minutes of the film; their font and color differ from the rest. Shannon cites a note by Mary Jordan published in the Alburz College Newsletter in Philadelphia on October 10, 1934, in which she stated that they possessed a film about the College’s activities and were willing to send it to the interested parties. She added: “There are two 16 mm reels which have been improved by recent additions.”49Matthew K. Shannon, “The Iran Mission on Film,” Presbyterian Historical Society Blog, May 16, 2022. Accessed April 28, 2025. https://pcusa.org/news-storytelling/blogs/historical-society-blog/iran-mission-film. It is highly probable that the ‘additions’ she mentioned are these intertitles, the title sequence, and the visual footage appearing at the end of the film. They were likely added in Philadelphia by the Church’s staff under the supervision of Mary Jordan (Figure 2).

Figure 7: The title sequence and three intertitles, distinguished by different fonts and colors, were added at a later stage.

The film opens with the title sequence, “Parviz Goes to College, Presented by Alborz College at Teheran.” The font used for this title varies from that of the second title sequence, which appears immediately after. The second title sequence reads, “A great college in an awakening land,”50Parviz Goes to College, 00:00:15. and its background is slightly lighter than the first. While beginning a promotional film with a title that provides basic information about the location appears logical (Figure 3), the question remains as to why it was added later. The answer may lie in the second title sequence and the phrase “an awakening land.” In the 1930s, all publications and media, including those produced by foreign entities for consumption in Iran or abroad, were subject to review, censorship, and approval by the police.51Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema, Volume 1: The Artisanal Era, 1897-1941 (Duke University Press, 2011), 152-155. According to Hamid Naficy, during the early years of the Pahlavī monarchy, the government established an organization called Sāzmān-i Tablīghāt va Intishārāt (The Propaganda and Publication Organization). This body was responsible for granting permission for the production and distribution of all forms of media, as well as for reviewing their content. Media created by foreign entities had to be submitted to this organization for approval before being published, screened, or distributed both within Iran and internationally. All media were expected to portray Iran as a developing and modern nation. Discussions of poverty and socio-economic challenges were forbidden. Although the westernization of Iran started in the late sixteenth century by Shah ‛Abbās I (the fifth shah of the Safavīd Dynasty, reigned 1587-1629), it was important for the newly established Pahlavī monarchy to be recognized as the architects of westernized and modern Iran. Initiating the film with the title “A great college in an awakening land” would have satisfied Iranian authorities while simultaneously highlighting Alburz College’s contributions to Iran’s “awakening.”52See Mohammad Ali Issari, “A Historical and Analytical Study of the Advent and Development of Cinema and Motion Picture Production in Iran (1900-1965)” (PhD diss., University of Southern California, 1979); And, Mohammad Ali Issari, Cinema in Iran, 1900-1979 (Scarecrow Press, 1990), 82–89. Issari published the full text of the 1936 regulations for films in his PhD dissertation and the book. He notes that these regulations were formalized into law in 1936. The police were given full authority to censor, reject, and confiscate films that did not comply with the established regulations.

Figure 8: This image highlights the contrasting fonts used in specific letters in the two title sequences, suggesting a potential difference in their production timeline.

During the film, two other intertitles refer to Iran as a modern country.53Rev. J. N. Hoare, who served in Iran from 1933 to 1936, submitted a report to the Church Missionary Society in London in 1937 regarding his mission. Hoare argues that Iran’s “new life movement” and modernization will not endure without the growth of the Church. He points to an example of an Iranian woman who converted to Christianity, gaining a “modern voice” and emerging “from the darkness of the veil into the light of God’s sunshine,” a phenomenon he describes as “new in Iran.” Hoare asserts that this transformation is made possible by both the Church and the new government. See Rev. J.N. Hoare, Something New in Iran (London: Church Missionary Society, 1937). The report is also available online at: https://anglicanhistory.org/me/ir/hoare1937/. One is the 4th sequence, “Modern Iran is a country of curious contrasts,”54Parviz Goes to College, 00:01:27. and the other is the 26th sequence, “Outstanding in modern Iran is Alborz college.”55Parviz Goes to College, 00:05:03. The scene that follows the 4th sequence depicts a farmworker using a wooden plow pulled by a pair of cows. The labor, arid land, and the thatch wall in the background suggest challenging living conditions for the farmworker.56Parviz Goes to College, 00:01:35. Next, we see a row of camels carrying goods shown in front of a brick structure, probably a bazaar. Working-class people and children are sitting or walking in the background. The camera moves closer to the camels as they exit the frame.57Parviz Goes to College, 00:01:31. One element Western audiences often associated with the Middle East and expected to see was the everyday presence of camels. The film includes three brief appearances of camels, reinforcing what Shannon identifies as the film’s Orientalist framing and its evocation of an “exotic East.” At minute 00:02:50, an intertitle introduces their role, “Camels bring the winter’s wood,” followed by extended shots of camels carrying firewood through the city, eventually arriving at a residential home. In another scene (00:02:56), camels are shown resting on the ground. Alongside the camels, the film also depicts Iranian urban transportation using carts drawn by horses and mules. This is followed by a sequence in which a durushkah (cart) carrying one man and pulled by a pair of horses enters the frame. The coachman signals the horses with a long wooden stick, stopping them to allow a man in a European-style outfit to look at a brick building.58Parviz Goes to College, 00:01:15. This intertitle is the only ambiguous one in this film. Was the intention to accentuate the poverty of the Iranian working class versus the wealth of the Westerners, to compare urban versus rural life, or to contrast comfort versus hardship? Furthermore, what does “curious” signify in this context? It seems the producers adopted a cautious approach by including “modern” before “Iran” while presenting it as a country of “contrasts.”

The 26th sequence, “Outstanding in modern Iran is Alborz college,” is followed by approximately 25 minutes of intertitles and footage that highlight the school’s contributions to the modernization process and the advanced Western lifestyle available to Iranian students at the school. The film particularly emphasizes Western machinery and material objects as indicators of modernity. For example, the 51st sequence features the intertitle, “Prof. Young makes his room assignment in the dormitory and arranges his scholarship work.”59Parviz Goes to College, 00:14:08. Three thick books with English titles are visible behind the door. In the accompanying footage, Parvīz is shown entering Professor Young’s office and presenting him with an envelope. In the following sequence, the medium shot of Professor Young and Parvīz transitions to a close-up of the professor’s head framed in such a way that the viewers can see the recording device he uses while reading from a sheet of paper. The content of the paper remains unclear, as the camera focuses on the device rather than the text. A black telephone is also visible next to the recording device.60Parviz Goes to College, 00:14:45. Black telephones reappear in two additional offices,61Parviz Goes to College, 00:11:10. and again following an intertitle that reads, “Other students do other jobs such as operating telephone switchboard,”62Parviz Goes to College, 00:24:46. which is followed by approximately one minute of shots from various angles depicting a student smiling and operating a telephone switchboard.63Parviz Goes to College, 00:25:28. In contrast to the intertitles discussed above, the three intertitles added to the end of the film at a later date are not informational in nature.

The font and color of the three intertitles appearing in the final four minutes of the film differ from those of the earlier intertitles, including the one in the opening title sequence. These three intertitles appear before and between eleven long and medium shots. The shots depict students and the staff moving toward the two-story chapel,64A woman, likely Mary, Jordan’s wife, appears briefly in this footage. preparing to stand or sit in front of it, settling on the balcony, attending the school’s Christian Conference—described as the “high point of each school year”65Parviz Goes to College, 00:30:53. The full intertitle is: “The high point of each school year is the student Christian Conference.” It is one of the original intertitles. —posing for the camera, and walking in front of the Chapel (Figure 4). The orange hue of the three long shots of the chapel also contrasts with the rest of the film and matches the color of the three added intertitles. It is therefore plausible that these scenes, like the three intertitles, were added to the original version of the film at a later stage in Philadelphia.

Figure 9: Students and staff assembled in front of the chapel, a still from the film Parviz Goes to College, 1932-34

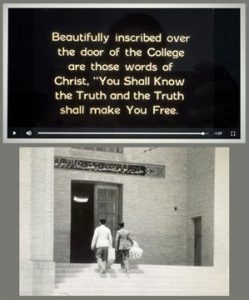

These shots are interrupted by another intertitle, “Student leaders prayerfully draw up a Christian challenge to students of Iran.”66Parviz Goes to College, 00:33:17. This is also one of the original intertitles with the same font and color. This is followed by two brief shots of five students, leading into the next added intertitle, “Beautifully inscribed over the door of the College are those words of Christ, ‘You Shall Know the Truth and the Truth shall make You Free.’”67Parviz Goes to College, 00:33:53. This refers to a decorative tile frame installed above the door of the main building at the school. The inscription on the tile is written in Persian, using a Quranic calligraphy style known as naskh, and is adorned with traditional Iranian-Islamic non-figurative patterns. The style of both the tile and the inscription closely resembles that of tiles displaying verses of the Quran or Hadith,68Ahādīs (singular: hadīs) are recorded sayings or actions attributed to the Prophet Muhammad or, in the Shiʿi tradition, also to the Imams. typically found in mosques, takiyahs, 69Tekeyehs (or takiyahs) are religious structures in Iran traditionally used for mourning rituals, especially during Muharram to commemorate the martyrdom of Imam Husayn. They serve as gathering spaces for theatrical reenactments, sermons, and other Shiʿi ceremonies. and shrines.70This tile is a rare example, though not unique. Iranian-Islamic decorative motifs were used by Christians in Iran both before and during this period. Some churches incorporated similar patterns into their design. A prominent example is Vank Cathedral in Isfahan, where the interior walls and ceilings feature biblical murals framed by intricate Iranian-Islamic ornamentation. See Mahshid Modares, “Religious Art in Iran During the Qajar Period,” Hunar-i Āgāh Magazine 6-7, (April-May 2016): 55-66. The fact that the words of Christ appear in Quranic calligraphy and that the Christian missionaries, who sought to convert students by preaching the Gospel, commissioned this Islamic artistic style and tilework, is a particularly striking choice.

The tile frame appears for the first time at timestamp 00:10:74. A long shot shows Parvīz seated in a durushkah as he approaches and enters the school. Upon his arrival at the entrance, the camera lingers for nine seconds, capturing a two-story brick building, a tall arch decorated with Iranian-Islamic patterns, and the tile frame positioned between a wooden window and a wooden door.71Interestingly, the interior and exterior of the two-story chapel differ noticeably from the main building and resemble a traditional church in both structure and design. This long shot is followed by a brief sequence in which Parvīz pays the driver. In the next sequence, Parvīz and his guide are seen walking toward the stairs and the main entrance. This time, the camera is positioned closer to the stairs, and the handheld camera slowly tilts upward to reveal the main door as Parvīz and his guide enter the building. This is the only moment in the film where the title frame is shown clearly (Figure 5).

Figure 10: The intertitle presents the translated inscription above the entrance. Below it is a still from the film showing the original Persian text, a still from the film Parviz Goes to College, 1932-34

Interestingly, there is no visual sequence between this intertitle and the next, which is “These men have been made free through the Truth which you have sent them.”72Parviz Goes to College, 00:33:41. In the following sequence, the scene returns to the two-story chapel scene, where students and staff are seen waving their hands or hats to the camera.73Parviz Goes to College, 00:34:18. Furthermore, one original intertitle appealing to patrons for support and prayers and one added intertitle containing the words of Christ are reserved for the very end of the film. These read: “They invite you to visit – support – pray for The Alborz College of Teheran,”74Parviz Goes to College, 00:34:26. and, “This is life eternal, that they should know Thee, the only true God, and him whom Thou didst send, even Jesus Christ.”75Parviz Goes to College, 00:34:36.

Conclusion: The Legacy of Parviz Goes to College

Parviz Goes to College stands as one of the most valuable missionary films produced during a period when few comparable examples existed in Iran or elsewhere. The film reveals the perspective of the missionaries toward the communities they sought to convert and westernize. It relies heavily on intertitles to guide the viewers’ interpretation of the moving images and to communicate its core message from the producers’ point of view. The missionaries present themselves as agents of modernity, with Western technologies positioned as instruments of progress, and Iranians depicted as recipients of a Western, Christian, upper-class lifestyle and belief system.

The footage, alongside the three added intertitles that emphasize the mission of the Evangelist educators, raises important questions regarding viewership and the differential treatment of audiences. The intended audience for the P.H.S. copy comprised the Church’s patrons, who expected the school to promote Christian conversion among Iranian students. The inclusion of the chapel scene and the three added intertitles served to enhance the film’s religious tone and likely aimed to encourage greater financial support. In contrast, the original version of the film, which lacks these elements, downplayed its evangelical mission, focusing instead on highlighting the American missionaries’ contributions to modernization and Western education, thereby making the film more appealing to Iranian families and less overtly religious in nature.

Acknowledgment

The author would like to express gratitude to Matthew Shannon for his request to digitize the 16mm reels and for introducing this film to researchers, and to Peter Limbrick, who supervised the writing of this article. A special thanks is extended to the Presbyterian Historical Society in Philadelphia for granting permission to include several still images from the film in this article.

Bibliography

Armajani, Yahya. “Alborz College.” Encyclopædia Iranica Online. Last modified July 6, 2018. https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/alborz-college/.

Ho, Joseph. Developing Mission: Photography, Filmmaking, and American Missionaries in Modern China. Cornell University Press, 2022.

Hoare, Rev. J.N. Something New in Iran. London: Church Missionary Society, 1937. Available online: https://anglicanhistory.org/me/ir/hoare1937/.

Issari, Mohammad Ali. Cinema in Iran, 1900-1979. Scarecrow Press, 1990.

Issari, Mohammad Ali. “A Historical and Analytical Study of the Advent and Development of Cinema and Motion Picture Production in Iran (1900-1965).” PhD diss., University of Southern California, 1979.

Katouzian, Homa. “Alborz and its Teachers.” Iranian Studies 44, no. 5 (2011): 743-754. https://doi.org/10.1080/00210862.2011.570483.

Ladjevardi, Habib. Memoirs of Mohammad Ali Mojtahedi. Harvard University Center for Middle Eastern Studies and Oral History Project, 2000.

Lorentz, John H. “Educational Development in Iran: The Pivotal Role of the Mission Schools and Alburz College.” Iranian Studies 44, no. 5 (2011): 647-655. https://doi.org/10.1080/00210862.2011.570424.

Modares, Mahshid. “Religious Art in Iran During the Qajar Period.” Hunar-i Āgāh Magazine 6-7 (Farvardīn and Urdībihisht 1395/April and May 2016): 55-66.

Naficy, Hamid. A Social History of Iranian Cinema, Volume 1: The Artisanal Era, 1897-1941. Duke University Press, 2011.

Saeidi, Elahe, and Amanda Thompson. “Using Clothing to Unify a Country: The History of Reza Shah’s Dress Reform in Iran.” International Textile and Apparel Association Annual Conference Proceedings 70, no. 1 (2013): 31. http://dx.doi.org/10.31274/itaa_proceedings-180814-621.

Shannon, Matthew K. “The Iran Mission on Film.” Presbyterian Historical Society Blog. Presbyterian Church, USA, May 16, 2022. Accessed April 28, 2025, https://pcusa.org/news-storytelling/blogs/historical-society-blog/iran-mission-film.

Shannon, Matthew K. Mission Manifest: American Evangelicals and Iran in the Twentieth Century. Cornell University Press, 2024.

Zirinsky, Michael. “Harbingers of Change: Presbyterian Women in Iran, 1883-1949.” American Presbyterians 70, no. 3 (Fall 1992): 173–86.

Zirinsky, Michael. “Inculcate Tehran: Opening a Dialogue of Civilization in the Shadow of God and the Alborz.” Iranian Studies 44, no. 5 (2011): 657-669. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00210862.2011.570425.

Zirinsky, Michael. “Jordan, Samuel Martin.” Encyclopaedia Iranica Online. Last modified December 12, 2014. https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/jordan-samuel-martin/.

Mediagraphy

“Alborz House | Khānah-i Alburz.” YouTube video, 7:52. Posted September 11, 2016. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DBlUqPdvasU&list=PL1hTDDqomX6voRVuzUafeNhFpsHxH2tmC.

Parviz Goes to College. Produced by Alborz College. Tehran, 1932-34. Black and White. 35 min. Digitized by the Presbyterian Historical Society (P.H.S.), Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 2020. Accessed April 28, 2025. https://digital.history.pcusa.org/islandora/object/islandora%3A169213.

Presbyterian Historical Society. “Parviz Goes to College, about 1930.” YouTube video, 34:43. Posted February 2, 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=obKIYcPo4KM.

Index: Order of Intertitles in the Film

- Title (First) Sequence: “PARVIZ GOES TO COLLEGE, Presented by Alborz College at Teheran”

- (min 00:00:04 to 00:00:15)

- Second Sequence: “A great college in an awakening land”

- (min 00:00:15 to 00:00:19)

- Fourth Sequence: “Modern Iran is a country of curious contrasts”

- (min 00:01:27 to 00:01:32)

- Eighth Sequence: “Ordinary travel is by motorcar, however”

- (min 00:02:08 to 00:02:12)

- Tenth Sequence: “Trucks carry the freight”

- (min 00:02:26 to 00:02:32)

- Thirteenth Sequence: “Camels bring the winter’s wood”

- (min 00:02:50 to 00:02:55)

- Nineteenth Sequence: “Iranian gardens and architecture have been famous for centuries”

- (min 00:04:26)

- Twenty-Sixth Sequence: “Outstanding in modern Iran is Alborz College”

- (min 00:05:03 to 00:05:08)

- Twenty-Eighth Sequence: “Headed by President S.M. Jordan”

- (min 00:05:47)

- Thirteenth Sequence: “President Jordan joins nomads on their spring migration”

- (min 00:06:01)

- Thirty-Fifth Sequence: “Mrs. Moore, donor of Moore Science Hall, leaves Tehran by plane”

- (min 00:06:45)

- Thirty-Ninth Sequence: “Students come from all parts of the land of the Medes and the Persians”

- (min 00:08:52)

- Fortieth Sequence: “The arrival of Parviz to begin his college course is typical”

- (min 00:08:59)

- Forty-Fourth Sequence: “Vice-President Boyce receives Parviz”

- (min 00:10:49)

- Forty-Seventh Sequence: “Next, Parviz pays his fees to Bursar Barseghian and registers with Mr. Chaconas”

- (min 00:11:48)

- Fiftieth Sequence: “Dean Groves approves his program”

- (min 00:13:24)

- Fifty-First Sequence: “Prof. Young makes his room assignment in the dormitory and arranges his scholarship work”

- (min 00:14:08)

- Fifty-Second Sequence: “Mr. Armajani, housemaster of Lincoln Hall, arranges his accommodations in the dormitory”

- (min 00:15:18)

- Fifty-Eighth Sequence: “End of PART ONE”

- (min 00:16:57)

- Fifty-Ninth Sequence: “PART TWO”

- (min 00:16:58)

- Sixtieth Sequence: “Parviz joins boarders at lunch”

- (min 00:17:00)

- Twenty-Second Sequence: “Parviz majors in Science in Moore Hall”

- (min 00:18:03)

- Sixty-Seventh Sequence: “Prof. Farhi teaches Parviz Iranian literature”

- (min 00:19:32)

- Sixty-Ninth Sequence: “Prof. Nakhosteen teaches Arabic”

- (min 00:19:49)

- Seventy-First Sequence: “Dr. Wysham teaches Religion”

- (min 00:20:15)

- Seventy-Third Sequence: “Parviz is eager to use the library”

- (min 00:20:49)

- Seventy-Sixth Sequence: “Other courses round out his program”

- (min 00:21:33)

- Eighty-Sixth Sequence: “Daily chapel and student orchestra”

- (min 00:23:22)

- Ninetieth Sequence: “Parviz operates college generator to earn his fees”

- (min 00:24:01)

- Ninety-Third Sequence: “Other students do other jobs such as operating telephone switchboard”

- (min 00:24:46)

- Ninety-Fifth Sequence: “Physical education is not neglected”

- (min 00:25:29)

- One Hundred Fifth Sequence: “Parviz learns lifesaving in college pool”

- (min 00:29:09)

- One Hundred Eighth Sequence: “When he is ill, the infirmary is ready”

- (min 00:29:48)

- One Hundred Tenth Sequence: “The high point of each school year is the student Christian Conference”

- (min 00:30:51)

- One Hundred Sixteenth Sequence: “Student leaders prayerfully draw up a Christian challenge to students of Iran”

- (min 00:33:20)

- One Hundred Eighth Sequence: “Beautifully inscribed over the door of the College are those words of Christ, ‘You Shall Know the Truth and the Truth Shall Make You Free’”

- (min 00:33:32)

- One Hundred Nineteenth Sequence: “These men have been made free through the Truth which you have sent them”

- (min 00:33:41)

- One Hundred Twenty-First Sequence: “They invite you to visit, support, and pray for The Alborz College of Tehran”

- (min 00:34:26)

- One Hundred Twenty-Second Sequence: “This is life eternal, that they should know Thee, the only true God, and him whom Thou didst send, even Jesus Christ”

- (min 00:34:26)

Cite this article

Parviz Goes to College is a short silent film produced between 1932 and 1934 in Tehran by Presbyterian missionaries under the supervision of Samuel and Mary Jordan. The film was created to promote Alborz College and was primarily aimed at two audiences: American donors who funded the Church’s educational initiatives overseas and Iranian upper-class families considering sending their sons to the College. This article examines the film’s title, intertitles, and various visual elements to analyze their significance in conveying two main objectives. First, the missionaries present a message of modernization, showcasing advanced technologies and a Western upper-class lifestyle for students. Second, they effectively promote Christianity. While the second message was directed toward American patrons, it was downplayed for Iranian viewers.