Poetic Pictures: The Feminization of Iranian Cinema

Introduction

In a nation where poetry permeates common parlance, is used to justify arguments, offer guidance, honor patrons, condemn adversaries, and confront authority, its influence naturally extends to various art forms, including cinema. The evidence of this connection between poetry and the moving picture is tangible, albeit slowly established and sporadic, embracing diverse methods and techniques over time.1For historical and analytical studies of Iranian poetic cinema see Khatereh Sheibani, The Poetics of Iranian Cinema: Aesthetics, Modernity and Film After the Revolution (London: I.B. Tauris, 2011) and Michelle Langford, Allegory in Iranian Cinema: The Aesthetics of Poetry and Resistance (London: Bloomsbury, 2019). Such films have come in various forms—some are inherently poetic, some are based on poetry, and others merely incorporate poetic elements. Additionally, the growing prominence of poetry in film aligns with women’s rising representation and productivity. Furūgh Farrukhzād and Shahrzād were two notable women who engaged in cinema and literature to different degrees before and around the 1979 Islamic Revolution. In the post-revolutionary era, there has been a surge in women’s participation in both fields. Notable figures such as Grānāz Mūsavī, Marzīyah Vafāmihr, Andīshah Fūlādvand, and Āzādah Bīzārgītī have significantly contributed to both domains. Through the works of these poets and filmmakers, this article analyzes the interplay between cinema and poetry, highlighting a common emphasis on women’s issues. It argues that women literary authors, filmmakers, and feminist discourse have, in recent decades, played a significant role in the production of movies that poetically focus on women or integrate poetry while delving into gender issues. This genre, which has little precedent in the pre-revolutionary era, reflects a unique intersection of artistic expression and social commentary. Furthermore, this paper argues that pre-revolutionary cinematic discourse, primarily a response to modernity and the shah’s top-down feminism and progressive reforms, aimed at protecting masculinity, which was perceived to be under threat. Conversely, the post-revolutionary movement and oppositional cinematic movement has seen the emergence of a dominant female-friendly cinematic discourse and has sought to safeguard femininity as a response to the current state’s systemic misogyny.2In today’s Iran, discussions around women’s rights, femininity, and feminism intersect and often overlap. While the feminine is universally associated with grace and elegance, it conveys a women-friendly approach. Feminism, on the other hand, focuses on gender equality. Labeling a film or any other art as feminine has a better chance of surviving censorship.

Figure 1: A still from Laylā (1997), directed by Dāryūsh Mihrjū’i.

Words and Pictures

The connection between cinema and literature is not new or exclusive to Iran. Spanish, French, and American cinema industries have long been making poetic films, and Italian director and poet Pier Pasolini even conceptualized the cinema of poetry in 1965.3Paolo Pasolini, Heretical Empiricism, ed. Louise Barnett, trans. Ben Lawton and Louise Barnett (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1988). In the context of Iranian cinema, it can be added that cinematic surrealism, employed to depict the struggle with the harsh realities of daily life, has developed a necessary affinity with poetry. There, a discursive imagination serves as the framework, with rearranged pieces of reality comprising the content.

In exploring the connection between poetry, cinema, and gender issues in Iranian film, this analysis looks for various techniques and elements that can enhance the viewer’s experience. One dimension involves the use of metaphors and symbols to construct and present multiple layers of meaning in scenes and the narrative. This is complemented by the deliberate incorporation or subtle echoes of poetic lines and expressions, adding a lyrical quality that resonates throughout the film. Poetic pictorial patterns can also be manifested through a direct use of rhymes and refrains, creating a visual rhythm that attracts the audience’s attention further. The dynamic interplay of movement, characterized by moments of go/stop, compels viewers to pause, ponder, and wonder, encouraging a deeper engagement with the plots. Furthermore, adopting minimalism also becomes a powerful tool, directing the audience to venture beyond the frame and participate in the act of imagination. Poetic films can thus adopt a more global language of images, transcending cultural boundaries to seek a universal emotional impact, thus the global success of many Iranian movies. The narrative flow can also maintain a delicate balance, with minimal control over the ebb and flow of textual or cinematic sequences, allowing for a more sophisticated and immersive journey through the intricacies of storytelling.

By employing the term “poetic (moving) pictures,” we can circumvent the challenges associated with defining Iranian poetic cinema. A visual composition is not confined to conventional prose or dialogue. Rather, these pictures have the ability to condense a concept, a dream, a memory, or an experience with the brevity, vibrancy, urgency, and turbulence reminiscent of a poem or a poetic picturesque allusion. This distinction is a reminder of the use of distinct sign systems by the two genres. As Pasolini emphasizes, “Instead, cinema does communicate. This means that it, too, is based on a patrimony of common signs.”4Paolo Pasolini, Heretical Empiricism, ed. Louise Barnett, trans. Ben Lawton and Louise Barnett (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1988), 167.

So, why has this meaning, this desire for literariness, become a feature, a fixation, for Iranian cinema? Should we deem the poetic a standard attribute of the Iranian film? It might be an unfair characterization or even a stereotypical designation to say that American cinema is entirely fascinated with violence. Equally, it might be half true to characterize French cinema by its obsession with sex, or British cinema with history. However, if such reductionism would prove helpful to our understanding, what would be the core characteristic of Iranian cinema? The cautious answer is that Iranian cinema has undergone a few representational metamorphoses due to the changing ideological and social discourses that have affected cultural production since the beginning of the twentieth century including nationalist, Marxist, Islamic, and feminist discourses. More particularly, many such changes were wrought upon the country in the dreadful year of the 1979 Revolution. In the post-revolutionary era and specifically after the 1990s when a reformist movement appeared in politics and religion, poetry lost its prominent spot to the novel but also became an attribute of Iranian cinema. From that period onward, films have been almost obsessed with poetry.

During the pre-revolutionary era, two women navigated between the realms of cinema, poetry, and the feminine (the three components of this discussion): Furūgh Farrukhzād, a poet who ventured into documentary filmmaking, and Shahrzād, who transitioned from the masculine world of cinema to the less gendered realm of poetry. In recent decades, the works of Grānāz Mūsavī, Marzīyah Vafāmihr, Āzādah Bīzārgītī, and Andīshah Fūlādvand are among the films made by women that demonstrate a poetic quality. These works might have been influenced by Farrukhzād’s work but are also inspired by the works of male filmmakers such as ‛Abbās Kīyārūstāmī, Dāryūsh Mihrjū’ī, Suhrāb Shāhīd Sālis, and Amīr Nādirī, who have all strengthened the poetic aspect of Iranian film.5By its conviction and messages, and unlike the commercial movies of the time, which often featured dance, nudity, and a morbid plot, Gav (The Cow) was not concerned with gender, sexuality, and entertainment, and thus, unsurprisingly, it did not do well at the box office. However, its critical and artistic approach paved the way for additional New Wave films. It gave rise to a generation of filmmakers in the 1970s who many see as the masters of Iranian cinema. Some of Iran’s greatest directors, including Suhrāb Shāhīd Sālis (Tabī‛at-i Bījān [Still life]), Dāryūsh Mihrjū’ī (Gāv), ‛Abbās Kīyārūstāmī (Khānah-i Dūst Kujāst [Where is Friend’s House]), Amīr Nādirī (Davandah [The runner]), and Bahrām Bayzā’ī (Bāshū, Gharībah-i Kūchak [Bashu, the little stranger]) began their careers in this period and have continued to be active after the revolution. Their works, one may conclude, have provided the context for the success of postrevolutionary cinema. New Wave filmmakers were less interested in featuring women characters and more interested in advocating social change. They adhered to a leftist discourse that sought more than anything else to change the political arrangement by criticizing the unpleasant realities of Iranian life under Mohammad Reza Shah (1941–79). Of those pioneering directors, some continue their poetic works. All of this indicates that poetic moving pictures, whether or not featuring gender issues, are not produced only when a poet makes a movie, or a moviemaker depicts poetry or poetic concepts. As will be further noted, some filmmakers made movies based on centuries-old classical romances and epics, meaning that filmmakers’ connections to classical literature or mythology can also lead to poetic films.

Overall, the more profound reason for the poetic quality of Iranian films pertains to the cultural history, social condition, and the necessity of expressing ideas through metaphors, allegories, or even shattered stanzas. Before 1979, intellectual and literary activities that supported violence against the Pahlavi dynasty’s aspiration for modernity were censored and had to use symbolic and allegorical constructs to convey their revolutionary and often somber messages. In the troubling, turbulent post-revolutionary period under a religious autocracy, liberals, feminists, and civil society activists are mostly limited to surrealism and symbolism in film and literature. Moreover, the rise of feminist literary discourse at the end of the 1980s in response to the fundamentalist state discourse and restrictive Sharia laws also affected the nature of Iranian cinema, which sought to fight back.

Poetry and Cinema Before the Revolution

Numerous pre-revolutionary movies (including all commercial movies and even Mas‛ūd Kīmīyā’ī’s acclaimed 1969 Qaysar) tacitly and sometimes boldly questioned or mocked the social bravery required of men and women to achieve a modern life, which itself required the exploration of sexuality.6Generally, Filmfarsi movies helped Iranian men to boost an image of masculinity that had been threatened by the Shah’s reforms. The stereotypical man in these movies is a strong man with a formidable mustache who speaks loudly and carries a knife. He often wears a large hat, does not laugh, and always looks handsome and well-groomed. He is always superior to the women, thinks ahead of the game, makes decisions, and takes action. The woman dances in a cabaret, cheats on the man, is poor, drinks, or takes drugs. There is a constant attempt to fend off fundamental questions about womanhood. They asked women to sacrifice, to safeguard gender boundaries, and to uphold tradition so men might protect and cherish their masculinity. Such depictions did not require much poetry; indeed, such films flew in the face of attempts to achieve modernity and helped the rise of a revolutionary culture and normalization of political violence in the late 1970s. Even the movies’ meager portrayal of women and sexuality was tainted with violence. In fact, based on an analysis of the broader dearth of the portrayal of sexuality and eroticism in pre-revolutionary Iranian arts and media, the book Modernity, Sexuality, and Ideology in Iran: The Life and Legacy of a Popular Female Artist (See Figure 2) argues that modernity never indeed fully unfolded in that period and that any attempt to promote the discourse of modernity was hampered by numerous obstacles, resulting in what the book conceptualizes as modernoid society, a society that resembles a modern one in some areas but lacks other essential modern structures. The book further argued that the reason for the absence of a successful modernization process and a pervasive discourse of modernity in Iran, particularly in the seventies, was that any public and theoretical discussion of modern ideas and philosophies lacked the necessary academic, intellectual, and national debate over the seminal subjects of gender and sexuality in poetry and film.7In particular, see chapters one and two in Kamran Talattof, Modernity, Sexuality, and Ideology in Iran: The Life and Legacy of a Popular Female Artist (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2011).

Figure 2: Book cover of Modernity, Sexuality, and Ideology in Iran: The Life and Legacy of a Popular Female Artist (Syracuse University Press, 2011)

Nevertheless, tracing and discussing the evolution of poetic traits within cinema should begin with a few rare movies of that period. Before the revolution, a few films experimented with literature. One was Siyavash in Persepolis (1963) directed by the poet Farīdūn Rahnamā. The film script clearly points to a few classical poetry sources such as the twelfth century Nizāmī’s Laylī va Majnūn (Layli and Majnun).8For a comparative exploration of the beauty, refined handling of gender relations, and the intricate narrative complexity in Nizāmī’s tale of Laylī va Majnūn, refer to Chapter six in Kamran Talattof, Nezami Ganjavi and Classical Persian Poetry: Demystifying the Mystic (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2023). Examples of such movies that were based on classical Persian narrative poetry include Layli and Majnun (1937), Layli and Majnun (1956), Layli and Majnun (1970) , Shīrīn u Farhād (1934), Shīrīn u Farhād (1970), Firdawsī (1934), , Yūsif u Zulaykhā (1956), Yūsif u Zulaykhā (1968), and Sīyāvush dar Takht-i Jamshīd (1968).9For more information see, http://www.golistan.org/ They lacked the intricacies of classical representation and advanced cinematic technology. Tajikistan, then under the restrictions of socialism but enjoying more advanced Soviet film and musical technologies, produced somewhat more successful films such as A Poet’s Fate (1957) based on Rūdakī’s life and Firdawsī’s poetic tragedies (e.g., The Story of Rustam, The Story of Rustam and Suhrāb, and The Story of Sīyāvush).

Later in the 1960s, and within the world of contemporary free verse poetry, Furūgh Farrukhzād creatively married pictures and poems in a twenty or so minute documentary titled Khānah Sīyāh ast (The House is Black, 1962). Her film has been the subject of several studies and presentations. Maryam Ghorbankarimi, Farzaneh Milani, Hamid Dabashi, and others have described her films as poetic.10See Nasrin Rahimieh and Dominic Brookshaw. Forugh Farrokhzad, Poet of Modern Iran (London: I.B. Tauris, 2010), 35. See also Maryam Ghorbankarimi, “The House Is Black, A Timeless Visual Essay,” in Forough Farrokhzad, Poet of Modern Iran: Iconic Woman and Feminine Pioneer of New Persian Poetry (New York: I.B. Tauris, 2010), 137–148; Hamid Dabashi, Masters and Masterpieces of Iranian Cinema (New York: Mage, 2007), 39–70. Mohammad Salemy writes, “Forough Farrokhzad’s The House Is Black stands tall, somewhere between moving images and words, sound and music, cinema and poetry, documentary and experimental film; between Realism, Surrealism and Magical Realism, while being none in particular.11See “It is Only Sound That Remains: Reconstructing Forough Farrokhzad’s The House is Black,” June 9, 2020, https://tripleampersand.org/sound-remains-reconstructing-forough-farrokhzads-house-black-2/. Gholam Haydari also writes, The House Is Black is “a cinematic poem and Farrokhzad’s first experiment in explicitly merging cinema and poetry.”12Gholam Heydari, Furūgh Farrukhzād va Sīnimā (Tehran: ‛Ilm, 1999), 36, 62. Of course, the film at the time seems to have contributed to the consistently negative discourse of the political opposition as it too was perceived as a criticism of the government which doubted the sincerity of its reforms. However, it is the poetic quality of the pictures that endures and not its social commentary. Her film contains rhythmic, somewhat balanced “stanzas” as regards its dialogue and the sequencing of the scenes. Whether considering aesthetics or chronology, Furūgh Farrukhzād’s work influenced Ibrāhīm Gulistān, Suhrāb Shahīd Sālis, Amīr Nādirī, and ‛Abbās Kīyārustamī—all men producing contemporaneously with or after Farrukhzād—rather than the commonly propagated notion that it was the other way around.13See Kamran Talattof, “Personal Rebellion and Social Revolt in the Works of Forugh Farrokhzād: Challenging the Assumptions,” in Forugh Farrokhzad, Poet of Modern Iran, ed. Dominic Brookshaw & Nasrin Rahimieh (London: I.B. Tauris, 2010).

Figure 3: A still from Khānah sīyāh ast (The House is Black, 1962). Furūgh Farrukhzād, Accessed via https://www.entekhab.ir/002GjO

Shahrzād’s Career in Cinema

Kubrā Sa‛īdī, known as Shahrzād, represents another connection between cinema and poetry around the 1979 Revolution. She acted in more than sixteen movies in the 1960s and ‘70s, and although she never had the leading role, her performances were occasionally praised, and she received two awards. She also wrote three volumes of poetry, a book of prose, a screenplay, and several commentaries for film journals. Nevertheless, in all those sixteen movies, men subjugated women and commodified their bodies. Then, the minute the leading lady became the protagonist’s exclusive woman, his property, she needed to leave the public space, the dancing scene, or anywhere other men’s gazes could fall on her. For women’s sanctity to be wholly redeemed, she had to be confined in a veil and within walls. There was no poetry, and there was nothing poetic at all about the subjugation of women. However, on some occasions, particularly in Farār az talah (Escape from the Trap, 1969), the shortest role she ever had, Shahrazād’s performance can be considered a moving moment merging storytelling, unspoken poetry, and dance.14In Farār az talah, the director Jalāl Muqaddam decides to simply have Shahrzād lounge around seductively, listening to a conversation between two men. She performs superbly. Shahrzād’s short part is peripheral to the film’s story; she does not utter a word. She does her usual erotic dance, however. Her character is passive and only an accommodation to her man, but she conveys this meaning very well with the movements of her eyes, hands, neck, and head. One can argue that she offers one of her best performances in this movie. She is genuinely confident and in control. Before and around the time of the Revolution, Shahrzād wrote and published three volumes of poetry.

Figure 4: A still from Farār az talah (Escape from the Trap, 1969). Kubrā Sa‛īdī, Accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8nRFeCLAs-A (00:58:42)

In her final year in cinema, she penned and directed Maryam va Mānī (Maryam and Mani, 1978), a film whose sole reel canister vanished amidst the chaos of the 1979 Revolution. Miraculously, a poorly digitized, shabby-looking version emerged online more than four decades later. The movie’s story is about an unconventional love affair between Maryam, a morally upright yet financially troubled woman resorting to theft from Mānī, a reserved figure who had extended a helping hand by offering her a ride. Besides a contentious scene about the quality of a poem, there is a trace of Shahrzād’s poetic chaos in the film and a reflection of her experience with dancing. In her poetry, we can always see differences and shifts between the poems and within each of her poems. This is because she seemed to be improvising in a way she improvised her dances. And when she danced, there was no choreography or predetermined structure that she adhered to. In fact, historically, dance in Iran, especially non-classical dance, did not have much organized and codified methodology, and only in recent decades, particularly in the diaspora communities, have we witnessed burgeoning compilations. Therefore, Shahrzād consciously or unconsciously used the same dance improvisation as the basis of her poetic constructs, and for this reason, we cannot find much fluidity and fluency in her poetic style but plenty of ambiguity and irregularity. We cannot predict the subject of the next stanza and its form, but at the same time, unlike her dance, her poetry is veiled, which adds to the difficulty of reading. Of what can be understood about Maryam and Mani, all this unruliness is present in the different parts and scenes of the movie. What an allegory of the uncertainties that defined the last year of the otherwise stable Pahlavi era!

Figure 5: A still from Maryam and Mani (1978). Kubrā Sa‛īdī, Accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0f4NVJl7p1g

The prevalence of a Marxist/Islamic revolutionary discourse, emphasizing mass mobilization against the monarchy and Western liberalism, effectively constrained the emergence of a poetic film genre so natural for a nation obsessed with prosody. This hindered the development of a progressive exploration of femininity in literature and cinema. Farrukhzād received acclaim primarily for her later works, particularly her social poems, before being killed in a car accident in February 1967 at the age of 32. Shahrzād faced social ostracization due to her performance of half-nude dancing in movies and cabarets, and she was imprisoned after the 1979 Revolution for participating in a rally against the mandatory veiling decree. Additionally, a lack of interest, investment, and technological resources further impeded a thorough and imaginative examination of the abundant classical Persian poetry repertoire.

The Post-revolutionary Rise of Feminist Cinema and a Cinematic Poesy

The 1979 Revolution gradually changed the agenda for oppositional intellectuals in literature, arts, and cinema, shifting the target of their criticism away from modernity and the West. It also brought a shift in the world of cinema, altering its priorities and possibilities, leading to the disappearance of dance and, more broadly, representations of the female body from the big screen. Dance has held a significant historical presence in Iran, dating back to the fifth and sixth millennium BCE and in the last century, the artform was often intertwined with popular movies and television shows. Despite the repressive and sexist stance of the Islamic government, which resulted in the banning of dance in cinema and public spaces, the art form has persisted within society, thriving in clandestine dance schools and private settings. Even the suppression of dance by arresting dancers and instructors (such as Muhammad Khurdādīyān, who on his 2002 visit to Iran was arrested, interrogated, and tried), has not deterred its growth. People continue to dance in unconventional spaces—streets, picnic areas, and roads—while being vigilant and dispersing when confronted by the Guidance Patrol Forces. Men have adapted some of women’s dance styles, some drawing inspiration from Khordadian, aligning them more closely with the restrictions on women’s bodies. However, this ancient Iranian art remains absent from post-revolutionary cinematic representations, save for occasional metaphorical depictions, such as symbolizing emotions and desires through the interaction of birds, flowers, or shadows. Occasionally, the absence of physical dance is compensated for by poetic verses that capture the essence of dance or simply by the movements of hands which is highly reductive. The cinematic realm, therefore, lacks the vibrant richness and narrative potential that dance could, in combination with lyrics, offer, and can only bring to the fore the rhythm of the words.

The absence of the body is also occasionally offset by the prominence of poetic expression, serving as a means to resist complete control by state ideology. Through the veiling code and other restrictions on social interactions, the Islamic regime in power in Iran tried to control every aspect of social behavior, especially women’s social and even private conduct. They banned the showing of the female body and hair, female singing, in life and on screen. Most new filming guidelines were designed to restrict female participation, particularly as a character with control over her body. Islamic Republic dress codes require women to cover their hair in public places (and the screen is considered a public space), and while in the presence of a man who is not related by marriage or blood. Women are required to wear loose-fitting outer garments to cover their curves. The word veil thus signifies more than the veil as a head covering (hijab). It suggests that women’s bodies and voices are also the subjects of ideological control and that women’s social conduct and even eye contact must be regulated in their relations with men. And such regulations even apply to the fictional world of films. This often results in the production of very artificial scenes where, for instance, a woman must wear the same outfit and a veil even in bed. Film directors must remember that the actors who play couples are not allowed to touch each other, get too close, or exchange words of deep intimacy. In doing so, cinematic artists draw upon the nation’s cultural wealth, using poetry as a tool of resistance—a device honed throughout Persian civilization.

The poetic device as a means of resistance thus gained existential significance in post-revolutionary movies, particularly burgeoning in movies concerned with women and gender issues. The development can be observed in the comparison between the pre- and post-revolutionary works of Dāryūsh Mihrjū’i. Before the revolution, he made a few political and psychological films, including Gāv (The Cow, 1969), the underlying perspective of which no doubt was rooted in Marxist class and alienation theory. In the post-revolutionary period, he made many movies that focused on gender issues, featured women prominently, and were concerned with culture rather than class.15Ijārah-nishīn-hā (The Lodgers, 1987), Hāmūn (1990), Bānū (The Lady, 1991), Sara (1993), Parī (1995), Laylā (1996), Mihmān-i Māmān (Mum’s Guest, 2004), Santūrī (2007). Several of his films bear female names as titles. In Laylā (1997), the young barren Laylā and her husband are going through difficult times trying to get pregnant. Their lives are turned upside down when the man marries another woman to bear offspring. Laylā’s inner feelings, internal conflicts, and degradation are portrayed through nothing but what can be conceptualized as poetic pictures focusing on the mundane items in one kitchen or the characters walking alone by a row of cypresses in the street.

Figure 6: A still from Laylā (1997). Dāryūsh Mihrjū’ī, Accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FSqBPr3PF04 (01:27:47)

Two of Kīyārustamī’s film titles draw inspiration from lines of poetry. Khānah-i dūst kujāst (Where Is the Friend’s Home? 1987) reflects a verse from Suhrāb Sipihrī’s poem, Sidāy-i pāy-i āb, “Water’s Footsteps” (1964). The film depicts a young boy, deeply concerned about his classmate’s forgotten notebook, embarking on a journey to find his friend in another village and return the notebook so he can do his next day’s homework and prevent his expulsion from school. It is also speculated that the title may have been indirectly influenced by the short story Cherā khānum mu‛allim giryah kard? (Why Ms. Teacher Cried?), by B. Tājvar.

Another film, Bād mā rā khvāhad burd (The Wind Will Carry Us, 1999), drives its title from a line in Furūgh Farrukhzād’s poem by the same title. This cinematic work incorporates visual elements and symbols reminiscent of the poem’s themes. The narrative follows a group of individuals posing as engineers who travel to a village for various reasons. The film explores cultural disparities between urban and rural life, as well as the dynamics in the interactions between men and women, featuring impressively strong female characters.

Although the films do not explicitly recite the poems, actions and images are skillfully intertwined to create an atmosphere that resonates with and echoes the sentiments of the contemporary Persian literary portrayals. In Kīyārustamī’s movies, the protagonists’ attitudes also evoke the essence of classical literature. All these brief examples indicate that poesy, poetic pictures, and poignant humor all help to focus on women’s concerns, particularly the devastating effect of state condoned (yet unpopular) polygamy forced upon the movie’s heroine.

Figure 7: A still from Bād mā rā khvāhad burd (The Wind Will Carry Us, 1999). ‛Abbās Kīyārustamī, Accessed via https://www.aparat.com/v/c573117 (00:00:05)

Another example of a movie that focuses on the condition of women under the Islamic regime, is Shukarān (Hemlock, 2000), by Bihrūz Afkhamī, a movie about a high-level manager’s affair with a nurse, ending in a tragedy. In this film, like in Laylā, pictorial melodies help portray feelings, love, and even some aspects of sexuality that cannot be depicted straightforwardly. In such movies, the characters use mild body language that is suggestive and completes the task of conveying a sense of a sexual relationship without contact or words. The directors employ symbolic language to convey physical intimacy. Instances include the overlapping of characters’ shadows, attire, or dialogue, serving as subtle cues for physical intimacy. Additionally, the camera strategically zooms in and freezes on the bedroom door without crossing the threshold, encouraging viewers to let their imaginations roam freely.

Figure 8: A still from Shukarān (Hemlock, 2000). Bihrūz Afkhamī, Accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VxGqzmIF4Jk (00:31:04)

In other cases, the protagonist’s emotions are expressed through highly metaphorical or symbolic dialogue. For example, actors use suggestive language to discuss something related to their faith, items, or personal situations, avoiding directly hinting at their lover. Boutique (2003), which portrays the problematic relationship between a bored boutique worker and a defiant and charming young student, provides such a technique. The young female character, played by Gulshīftah Farahānī, shows much excitement about her male friend’s car and sunglasses, which, under any ordinary situation, away from the camera or watching eyes, would have been expressed about aspects of the male character himself.16For a discussion of this topic and more examples of the treatment of hijab in the movies, see Norma Claire Moruzzi, “Women’s Space/Cinema Space: Representations of Public and Private in Iranian Films,” Middle East Report, No. 212 (Autumn, 1999): 52–55. In reality, the brand of that car is indeed highly despised.

Santūrī (The Music Man, 2007), another film by Mihrjū’ī, portrays the clashes between modernity and outdated, yet persisting, religious norms. While much of the film is about a musician and music, replete with meaningful and pertinent lyrics, it attempts to convey the female predicament and intimacy through innovative, clever techniques. In a car ride scene, the female and male characters suggestively touch each other’s clothes. In another scene, the woman asks a Mullah who is marrying them to kiss the groom for her, a statement that may not make much sense in the context of the film but becomes a social statement outside the cinematic text about the illegality of public display of intimacy.

Figure 9: A still from Santūrī (The Music Man, 2007). Dāryūsh Mihrjū’ī, Accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3fv0UJFe2cY (00:45:40)

The newest generation of female film directors have become more preoccupied with poetry while particularly focusing on the presentation of the female. Women must, of course, abide by a few more codes of conduct in the production of their films, on or off screen, but they have found lyrical ways to address some sexual, social, and cultural issues, albeit subtly and not so suggestively.

Poetic subtlety in articulating desire and sensual love has a significant legacy in classical Persian poetry. For example, one might mention the long narrative romances of the twelfth-century Persian poet Nizāmī Ganjavī. In works such as Haft Paykar (The Seven Beauties) and Khusraw va Shīrīn (The Tale of King Khosrow and Queen Shirin), Nizāmī portrays love and intimate moments with such finesse that certain sections of these narratives might be deemed a “book of lust.” Despite the explicit nature of these themes, Nizāmī’s narrative finesse managed to navigate through the centuries without inciting many objections from religious leaders. All these leaders and the religious and literary critics, who, for centuries, have assumed a self-appointed authority over linguistic “purity” in the Persianate world, remained unperturbed by the artful expressions of Nizāmī’s poetic sensibility by reading them as mystical expressions of love for god or deity.17See Talattof, Nezami Ganjavi and Classical Persian Poetry (London, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2022).

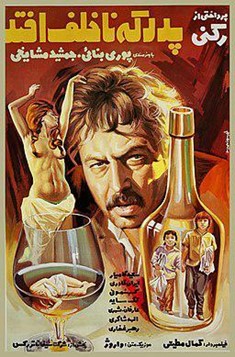

Nizāmī’s work, a testament to the romance genre, has been a world apart from cinematic adaptations of such literary works. When subjected to the pressures of the screen and censor, these adaptations raise the question of whether they can maintain the essence of their genre and the discourse of modernity that has supported it. This phenomenon was particularly evident in the pre-revolutionary Filmfarsi genre (see figure 3), where sex was often portrayed merely as a tool for asserting masculinity, which had been threatened by the King’s forward-looking reforms and state feminism. There, cinema succumbed to the dark force of the past. The music, songs, and dances were, however, highly entertaining, some mediocre and some phenomenal. Understanding the highly complex Filmfarsi genre helps explain the lack of a strong poetic cinema, the use of poetry in film, and the absence of the modern approach to sex and eroticism in the pre-revolutionary cinema.

Figure 10: Poster for the film Pidar ki nā-khalaf uftad (1972).

Popular journals used the photos, stories, and scandals related to these films to sell more copies but did not address the anti-modern messages of these films; instead, they indirectly and falsely condemned the Shah and the West for “spreading” these films. One of the many articles in the influential and intellectual Firdawsī Magazine entitled “The Miracle of Narcotizing People’s Thoughts through Pictures is the Most Traitorous Activity Going On.”18Mehrangiz Kar, “Mu‛jizah-i Takhdīr-i Afkār.” Firdawsī Magazine 25, no. 1130 (24 Shahrīvar): 14–15. The author was very determined to work on women’s issues after the revolution and before she was harassed by the Islamic regime and forced into exile. The author laments that many new female stars emulate Mahvash, who was one of the first Iranian women to dance and sing in cabarets and in the movies.19For more discussion of this film genre and pre-revolutionary female dancers see Talatoff, Modernity, Sexuality, and Ideology in Iran (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2011). He refers to this emulation as Mahvash-zadigī (a phenomenon also termed “struck by Mahvash” or “Mahvashism,” implicates other artists, such as Shah-par, Āfat, and even Shahrzād). But while Mahvash used her style of dancing and singing trivial, funny folk songs to create excitement and try to engage the audience in the singing, these new female stars pretend to be intellectual and interested in philosophy. The problem, the article explains, is that they really are just used to increase the profit of investors in show business. These corrupt Mahvashes, the article maintains, prevent a serious rapprochement of questions about women’s problems. Although the author does not explain those problems, the article finally gets to the point:

We are different from the U.S. society where people do not forget their social responsibilities and daily work when they see the naked body of Raquel Welch. Here in Iran, men will go nuts when seeing such nudity. They go nuts seeing a woman’s accidental winks. Seeing naked bodies, they become mentally unstable, and psychologically ill. As a result, men who are sexually deprived are living with a psychological crisis and women who are delirious about freedom are living with different psychological complexes. All this will result in crimes, murders, and possibly even honor killings. 20See Talatoff, Modernity, Sexuality, and Ideology in Iran, 85.

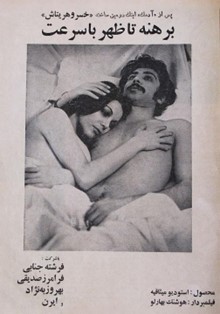

There is one truth in this analysis about the effect of such movies on deprived men, but the solution the article offers was part of the discourse that led to the rise of the 1976-79 revolutionary movement that replaced the king’s secular rule with the guardianship of the Islamic jurist. Moreover, the article looks at sexuality only from the male point of view; there is no discussion of what movie actresses and singers faced in their jobs as entertainers, and there is no reference to the documented effect of these movies on women or on their families. In fact, these popular journals avoided any serious discussion of women’s issues and hardly translated or published any serious articles related to universal women’s movements. They never addressed the fundamental question of whether Iran should try to be like a Western society where men no longer go “crazy” upon catching a glimpse of a woman’s body. It never occurred to those intellectuals that the millennium-old Persian poetry had illustrated sex and eroticism in realistic and allegorical forms. Nizāmī’s “pictorial allegories” of love and sexuality would have been perfect to feature even more eroticism and sexuality on screen without fearing that Iran is “different” from US society.21For the definition and discussion of “Nezami’s Pictorial Allegory” see Talattof, Nezami Ganjavi and Classical Persian Poetry (London, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2022). Michelle Langford reveals that many Iranian filmmakers have, historically, discovered allegorical methods to address forbidden topics and issues in their films, employing allegory as a purpose beyond merely circumventing censorship rules. The author demonstrates that his practice draws inspiration from the rich history of allegorical expression in Persian poetry and the arts, establishing itself as a fundamental aspect of the poetics of Iranian cinema.22Langford, Allegory in Iranian Cinema (London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2019). It should be added that the grossly exaggerated pre-revolutionary censorship mostly targeted the baseless social criticism that sought to prompt a socialist revolution. Using allegory to portray love and sexuality would not have been censored, as exemplified in the rare Birahnah tā zuhr bā sur‛at (Speeding Naked till High Noon, 1975), which, despite its highly Western orientation, can bring some of the tales of Nizāmī’s Haft Paykar (The Seven Beauties) to mind.

Figure 11: Poster for the film Birahnah tā zuhr bā sur‛at (Speeding Naked till High Noon, 1976).

Khatereh Sheibani aptly clarifies how the process evolved when she writes, “The poetic cinema that emerged in the pre-revolutionary period became the main artistic form of expression after the revolution. Post-revolutionary Iranian cinema, as represented in Bahram Bayzai’s and Abbas Kiarostami’s films, has drawn on long-established themes in Persian literature and the performing arts.”23Sheibani, The Poetics of Iranian Cinema (London: I.B. Tauris, 2011). How has the poetic approach influenced the portrayal of women and women’s issues under a misogynistic state ideology?

New Post-revolutionary Poetic Expression by Iranian Women Filmmakers

To begin, in the post-revolutionary era, a boutique, a brand-new car, the booming resonance of music from a sound system, or well-designed train stations are not simply portrayed as symbols of modernity. Instead, they further serve as the locale where tensions over gender and sexuality may either intensify or dissipate. Today, because Iranian films are not able to show flesh and dancing, they do depict, rather more seriously, the subjects of sexuality, gender roles, and women’s place in contemporary society—sometimes as bleak and sometimes hopeful, reflecting the way that these tensions run through the social fabric itself. A significant part of this new cinematic interest in gender issues is rooted in and assisted not only by the rise of feminist discourse but also the late 1980s interest in poetic and allegorical depictions in cinema.24As has been the case with literary movements, cinematic communities have also always shaped the way their consumers interpret their cinema products. The dominant mode of film reception in Iran has also changed every time a new movement or a new mode of expression appears. Each movement encourages its own way of reception. The elements that constitute this discursive relationship between the filmmakers and their audience include cinematic techniques, sarcastic language, symbolism, and metaphor, all being worked into the context of the relationship between the regime’s dominant ideological discourse, censorship, and the country’s desire for change, progress, and simple functionality. By encouraging an understanding of the nuances of the plots, filmmakers also promote a subjective reception. Through all this, they shape the viewers’ tastes and teach them to place the importance of political or sexual meaning over any symbolic, cinematic, entertaining scene. The response to a successful movie is sometimes long lines at the box office, praise and positive reviews in cinematic weblogs, or the banning and punishment of the filmmakers.

Grānāz Mūsavī’s award-winning Tihrān-i man harāj (My Tehran for Sale, 2009) is a powerful portrayal of the struggles of a modern woman in Iran’s contemporary political climate. The movie is also groundbreaking in its portrayal of sexuality in the post-revolutionary period. Before directing this movie, Mūsavī was already an established poet.25Grānāz Mūsavī’s My Tehran for Sale best represents the connection between cinema, poetry, and feminism. Mūsavī is considered a filmmaker and an avant-garde poet with a few published collections, including the noticeable Sketching on Night. Her My Tehran for Sale, banned for a while after being screened, is interconnected with poetry in several ways. In 2015, she published a bilingual (Persian and French) poetry collection entitled Les rescapés de la patience. Her film, a blend of cinema, poetry, and feminist ideas, challenges traditional restrictions in Iranian society and the cinema industry. The story, told through a collection of mini episodes, a combination of collages, and a nonlinear poetic narrative, portrays people who are different and cannot find their place. The film is a bit creative in storytelling and quite Western in its cinematic techniques, yet deeply Iranian in the type of tensions it builds nonstop. To make this movie, Mūsavī and some of her friends from her original country, Iran, and her new home, Australia, collaborated to tell an empathetic and intensely personal story familiar to middle-class Iranian intellectuals. Marzīyah, played by Marzīyah Vafāmihr, is a tough woman who nevertheless seems unable to resolve the contradictions between her lifestyle and her family; between her love for theatrical performance and the cultural restrictions on performance; between leaving the country for Australia and staying in Iran. The more she tries, the more she stumbles into predicaments. It has been criticized for being low budget, having fractured scenes, uneven editing, and for being vulgar and anti-religious establishment; however, one can see these flaws as representative of an underground culture that no perfect camera can see. Moreover, the reviews missed the most impressive aspects of the movie: its daring portrayal of couples in bed or kissing in public, perhaps the features that caused its ban, and its actress’s arrest. And no matter what, this movie is an excellent example of how poetry and pictures interact. It is worth examining in detail the diverse ways this has been done.

Poetry and Pictures in My Tehran for Sale: Names, Reciting, and Signing Poetry

Marzīyah meets a young man named Sāmān at an underground party held in a stable. When security forces attack the gathering, Marzīyah and Sāmān, who are alone in a separate area of the stable, manage to escape the chaos. Marzīyah shows Tehran to her friend, starting with the outside of the cemetery where several poets are buried. The scene above where Marzīyah recites/sings a couple of lines of a song by Qamar in honor of Īraj Mīrzā refers to a more historical connection between performance and poetry, past and present.

Furthermore, a poet, played by the poet/director Mūsavī herself, reads her work in two other scenes, depicted to evoke a sense of a leftist gathering. This is strange given the fallacies that leftist and Marxist discourse promoted prior to the Revolution and the contrast they exhibit with the struggle for modernity in this movie. The verses from the first scene explicitly reference the story of the film, particularly the story of Marzīyah (played by Marzīyah Vafāmihr featuring a young female actress whose theatre work is banned and she is forced to lead a secret life), conveying a sense of crashed, forbidden eroticism. The poet/actress sits behind a small table in a small room surrounded by several men and women sinking in sofas around her, some smoking, some drinking, and others languorous. She reads,

کیفم را بگردید

چه فایده؟

ته جیبم آهی پنهان است که مدام شنیده: ایست

ولم کنید!

اصلا با بوته ی تمشک میخوابم و از رو نمی روم

چرا همیشه زنی را نشانه می گیرید

که دل از دیوار می کند

قلبی به پیراهنش سنجاق کند؟

در چمدانم چیزی نیست

جز گیسوانی که گناهی نکرده اند

ولم کنید!.26As recited in the movie My Tehran for Sale (2009), Director: Grānāz Mūsavī, 60. The poem is translated by the author of this article.

Yeah, search my purse

But for what?

My lament, which has heard you constantly yelling ‘halt.’

is hidden in the depths of my pocket.

Leave me alone!

Frankly, I sleep with the raspberry bushes

And I will not be outstared.

Why do you always target a woman who

has not done anything but give up the walls

or attaching a heart to her clothes?

There is nothing in my suitcase except

My hair who has not committed a sin.

Leave me alone!

Figure 12: The female poet sitting at a small table in a small room, reading poetry. Tihrān-i man harāj (My Tehran for Sale, 2009). Grānāz Mūsavī, Accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zM0bzfePaA4 (00:42:37)

This portrayal of the harrowing consequences of the regime’s oppression of women is executed poetically, captivating not only the characters within the scene but also resonating powerfully through the lens of the camera. In this mixed militant-hedonistic performance, a symbolic allegory unfolds as the female narrator ambiguously places her (innocent) strands of hair, that are supposed to be under the hijab, into a suitcase, another confinement. The lines of the poem gradually refer to the significance of a broader emotional spectrum where the evocative act of sleeping with a “raspberry bush” serves as a reminder of concealed erotic undertones reminiscent of some of the poet’s other verses.

Grānāz Mūsavī (who acts in and directs the movie), has published a few books of poetry, including a French-Persian bilingual collection. As you can see, the poem is as daring as the movie itself. In another scene, one can hear a performance of Farrukhzād’s “My whole being is a dark verse.”27My Tehran for Sale (2009), Director: Grānāz Mūsavī, timeline starts at 1:05:28 with: همه هستی من آیه تاریکیست This scene can perhaps explain the poem’s enduring relevance as it reflects women’s current condition more than the progressive condition of the 1960s.

One more example is a poem recitation that starts when Marzīyah rides in the back of a truck out of the country clandestinely and with the help of smugglers. There is a flashback to when she was with her friend wandering in the Tehran foothills, and together singing a poem by Hāfiz (a 14th century Persian poet).

الا ای آهوی وحشی کجایی

مرا با توست چندین آشنایی

دو تنها و دو سرگردان دو بیکس

دد و دامت کمین از پیش و از پس

بیا تا حال یکدیگر بدانیم

مراد هم بجوییم ار توانیم

که میبینم که این دشت مشوش

چراگاهی ندارد خرم و خوش28See, “Ilā ay āhū-yi vahshī” in Hāfiz, Dīvān (Tehran, Zavār, Sīnā, 1941), 354

O Wild Deer, where are you today?

So much like each other, we have come all this way.

Lonely and wandering, we two cannot last;

we are both prey stalked by our future and past.

So let us into one another inquire

and discover therein our deepest desire.

Why cannot these depths of our wild desert land

offer safety and joy sometimes in its sand?29Feb. 3, 2013 (9:21 PM) “Wild Deer” by Hāfiz, Seawrack’s Song at: https://momentoftime.wordpress.com/2013/02/03/wild-deer-hafez/

The recitation of Hāfiz’s lines is followed by the sound of the call to prayers coming from down below and a few of Marzīyah’s primal screams. The poetic quality of the sequences, the dialogues, and the scenes is so well established that the plot indeed evokes other Perian poems. Two lines from Rumi (13th century Persian poet) read,

یک خانه پر ز مستان مستان نو رسیدند

دیوانگان بندی زَنجیرها دَریدند

جانهای جمله مستان دلهای دلپَرستان

ناگه قَفس شکستند چون مرغ بَرپریدند30My Tehran for Sale (2009), Director: Grānāz Mūsavī, quoting from Mulānā, Dīvān-i Shams (Tehran: Amīr Kabīr, 1997), no. 850, and rendered by the author of this article.

In a house filled with wine and intoxication, the drunks arrived anew,

The entrapped madmen broke free from their chains.

The souls of the intoxicated, the hearts of the lovers,

Suddenly broke the cage and flew like birds.

Figure 13: Marzīyah and her friend murmuring Hāfiz’s poetry in the foothills of Tehran. Tihrān-i man harāj (My Tehran for Sale, 2009). Grānāz Mūsavī, Accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zM0bzfePaA4 (01:26:33)

The poem is recited in a new setting but is nevertheless reminiscent of an earlier scene in which the poet shared her verses with her seemingly intoxicated, revolutionary-looking companions. The last line is an allegory of the protagonist’s escape from her besieged nation, the “cage.” Because of the universality of its message, contemporary Persian singers have used it for the lyrics of their songs. The poem conveys an unattainable desire for liberation and freedom from constraints. The imagery of a house filled with wine and intoxication, similar to some of the scenes portrayed in the movie, suggests a setting of revelry against abandonment and inhibitions. The arrival of new drunks and the liberation of entrapped madmen symbolize a release, or desire for release, from societal or personal restrictions. The intoxicated bodies and the hearts of lovers break free like birds from a cage. However, in this story, the women’s emancipation feels elusive and unlikely, making the scream inevitable.

The poems used for My Tehran for Sale become even more specific to the story. At a certain point during Marzīyah’s truck ride, a melancholic murmur echoes two lyric lines from the 13th-century Persian poet Sa‛dī Shīrāzī. This poetic moment, however, overlaps with a flashback scene in which her mother appears unable to communicate with her. She is apparently burdened by the perception that Marzīyah has become a disgrace to her father because of her open sexuality.

ای گنج نوشدارو بر خستگان گذر کن

مرهم بدست و ما را مجروح میگذاری

عمری دگر بباید بعد از وفات ما را

عمری دگر بباید بعد از وفات ما را

کاین عمر طی نمودیم…

کاین عمر طی نمودیم…

اندر امیدواری، اندر امیدواری،

اندر امیدواری، اندر امیدواری31My Tehran for Sale (2009), Director: Grānāz Mūsavī, referring to Sa‛dī Shīrāzī’s Ghazal no. 559 (https://ganjoor.net/), and rendered by the author of this article.

O you, the wealth of antidotes,

Come to the desperate, jaded ones.

You have the remedy, but you leave us wounded

We need another lifetime after our death

We need another lifetime after our death

Because we lived this life

Because we lived this life

Wistfully, wistfully

Wistfully, wistfully

This poem, inspired by Sa‛dī Shīrāzī’s poetry, conveys a sense of disappointment and frustration with life. It suggests that while life offers remedies for human suffering, it fails to provide one for the speaker, highlighting the stark contrast between the general and abstract, and the specific and personal. The repetition of the lines “We need another lifetime after our death” suggests the lack of a second chance in this life. The repetition of “Because we lived this life” and “wistfully” emphasizes the impact of unfulfilled desires and aspirations in current existence. The overall tone appears melancholic and reflective and combined with the sadness in the vocal performance, conveys a sentiment of unmet expectations and the vain desire for a chance at a more fulfilling “life” after this life. The flashback scene conveys the message that even her loved ones cannot be of any support. Perhaps in the next life, she will not be a “disgrace.” The melancholic murmur of those few lines in the scene during a truck ride succinctly describes a poignant moment in Marzīyah’s life, where pondering the painful past and bleak future leads to despair and regrets.

Songs and Music

In fact, vocal performances and musical tones within film enhance the meaning of disappointment, relationships, and at times utter despair in regard to social issues. Songs in these films are generally based on recognizable poetry and aim to describe the mood and the action. It is possible that both the music and the lyrics are radical in form and content, as has been the case most recently with the underground mélange of rock, blues, and traditional Persian music, using new or classical poetry. Of note is the song sung by Bābak Mīrzākhānī starting with the line “امشب زنی که خنده غریبه ای را دید تا صبح بیدار ماند” (Tonight, a woman who saw a stranger’s smile stayed awake till morning).32The lyrics of the song by Bābak Mīrzākhānī Music Group. “Emshab” [Tonight] – Babak Mirzakhani, Cassandra Wilson on SoundCloud, https://soundcloud.com/roozname-sobh/emshab_babak_mirzakhani

Signs and Poetry

Other scenes in My Tehran for Sale, even those portraying locations outside Iran are also replete with other poetic significations. When Marzīyah is in a refugee camp in Australia awaiting the hearing for her asylum case, she is depicted in her bed reading the translation of a collection of poetry by Sylvia Plath. Before her departure for Australia, Marzīyah liquidates her furniture and other possessions to fund the smuggler who facilitated her exit from Iran. While she chooses to gift two Persian poetry books to a friend, the circumstances surrounding her decision to bring Sylvia Plath’s work to the camp in Adelaide remain unclear. The scene might remind viewers of Sylvia Plath’s poetic exploration of psychological and emotional struggles, the intense and raw expression of personal experiences, including themes of mental illness, identity, death, and the complexities of relationships. Furthermore, both the movie and Plath’s poems reflect a profound sense of despair but also reveal a keen intellect and a powerful, confessional, autobiographical voice.

Moreover, in an earlier scene, Marzīyah is sitting on a staircase, very depressed (see figure 4). Near her, a portrait of Furūgh Farrukhzād is hanging against a colorful but faded wall and in front of her, six rows of staircase railing stand prominently. The picture, taken by Nāsir Taqvā’ī, was published in the 1960s in a journal called Hunar va Adabīyāt-i Junūb (Arts and Literature of the South), edited by Mansūr Khāksār, and it is telling that it shows up in this film. In the background, we hear a song by the underground group of Bābak Mīrzākhānī. Farrukhzād’s poems (and more so her prose writings) are also autobiographical, portraying a young, idealist, aspiring, hopeful person seeking seemingly unattainable happiness. She too had to maneuver between strong family traditions regarding marriage and her desire to be a free woman in charge of her own destiny.33Talattof, “Personal Rebellion and Social Revolt in the Works of Forugh Farrokhzād: Challenging the Assumptions.”

Figure 14: Marzīyah sitting on a staircase next to a photo of Furūgh Farrukhzād. Tihrān-i man harāj (My Tehran for Sale, 2009). Grānāz Mūsavī, Accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zM0bzfePaA4

Finally, even the movie trailer features mostly scenes replete with poetry or singing, further enforcing the existence of the connections between the genres rather uniquely but also signaling to the critic that this quality sells. In it, there is no attempt to persuade consumers that the movie offers action, drama, or a captivating love story.

But why does a movie that features underground art scenes and communities of Tehran, that focuses on the life and predicaments of a young actress who has been banned from performing in theater, infected with HIV, rejected by her family, and abandoned by her boyfriend have to be so closely connected to poetry? Why can a highly modern woman’s struggle to remain relevant in her pursuit of her passion in a context conducive to her lifestyle be considered a poetic subject? The answer is that leading a secret lifestyle under a religious state is not only a social dilemma but also deadly. Even talking about her constant difficulty with decision making in a strange moment in the contemporary history of Iran and with her identity is dangerous and can only be done through the powerful ambiguity of Persian poetry.

Marzīyah’s story, like many others, has not been easy to feature. There are many more that have yet to be written. These are contemporary tragedies about unfulfilled dreams, shattered hope, detention, torture, and death. They are stories of suffocation that leave no breath for their narrators to tell them. Only metaphorical constructs, allegorical ambiguity, and symbolic signification can narrate them and portray their heroic resistance. Restrictions on freedom of expression paradoxically contribute to how the plots are treated implicitly, mythically, and poetically.

Thus, Marzīyah Vafāmihr was praised by film critics, condemned by conservative journals, and imprisoned by the Islamic Republic for her role in My Tehran for Sale. The attacks became more personal because many of the incidents, experiences, and particularly poems in the film reflect the real-life experiences of Vafāmihr and Mūsavī. It was no coincidence that the fictional character’s name was Marzīyah. Marzīyah, in the film, and Marzīyah, the actor in her teenage years, share many traits: they are both unruly, art students, actresses, secular, and ambitious. They both went to the nearby mountains to shout at the darkness of the city below them. Marzīyah, the film character, also reflects some of Mūsavī’s traits: love of poetry, desire to run away, to migrate, and familiarity with the lives of refugees.34Marzīyah Vafāmihr, a key figure in this analysis, co-presented a Zoom seminar with the author of this article at the University of Arizona in 2021. In the subsequent correspondence, her insights shed light on the personal aspects of this film. Conservative journals heavily criticized the film as another example of underground movies aimed at undermining the foundation of the Islamic Republic. For instance, it was the subject of intense scrutiny in “Sīnimā-yi Zīrzamīnī: Chūb-i Harāj-i Rushanfikrān bar Īrān, Mazhab va Sunnat,” [Underground Cinema: Iranian Intellectuals’ Auctioning Iran, Religion, and Tradition], Mashriq, March 21, 2011, C 40525. These attacks contributed to the eventual arrest and imprisonment of Vafāmihr.

Poetics of Vafāmihr’s Films

More and more filmmakers, including those from younger generations, delve into a poetic tradition spanning over a millennium to illuminate the origins of pain or suggest remedies for the constraints and repression that give rise to such pain. This breathes new life into Iranian cinema whenever it appears constrained and undermined by the ruling elite.

The lead actress of My Tehran for Sale (2009), Marzīyah Vafāmihr, has contributed to the poetic development of films by writing and directing. Her film Bād, Dah-sālah (Wind, Ten-Year-Old, 2006) exemplifies Iranian poetic pictures in its sense of elusiveness and urgency. In this short film, she ponders the roots of some psychological programs conducted during the 1980s war that were seen as affecting young elementary students. Wind, Ten-Year-Old might even be perceived as an attempt at Fellini’s style or reminiscent of the 1978 documentary Le Vent des Amoureux by Albert Lamorisse.

Because the movie is unavailable for public viewing, its analysis here will only include comments on its pertinence to the subject at hand. By featuring a day in the life of a 10-year-old girl, the film emphasizes the Iran-Iraq war, its effects on children’s lives, and how the related cultural propaganda installed turmoil, fear, and doubt in the minds of a generation.

Like many Iranian films made about children, it entails complexity and nested layers of meaning. Each scene consists of metaphors and allusions with double meanings (if not more). Directing and managing a children’s play is admirable and tender. It is no doubt challenging to portray war and trauma in poetic cinematic language. The film opens with a female teacher telling her female students, in an authoritative voice, to place their books on their desks. A student immediately shouts, “The heater is on fire,” prompting everyone to run away from what seems to be a large corner kerosene heater and evacuate the small classroom, i.e., everyone except for a defiant young girl who, for a while, continues to stare at a point in front of her. This sets up an allegory for the rest of the film which is about the Iran-Iraq war (1980-1988) focusing on how children witnessed violence and chaos and how they coped or did not cope with it.

The soundtrack features religious chanting and the voice of Ruhollah Khomeini, the leader of the Revolution, evoking sad memories and fear. In one scene, an older man watches an old Soviet war movie. Soon, the defiant student is cast as the lead female actress of that movie skipping in her neighborhood street. Another scene shows an older woman working on her sewing machine in a Basīj (paramilitary) Troop Station. She has some direct, disheartening words, but her utterance is soon eclipsed by the heartbreaking complexity of the background, where the sewing machine sounds and feels like a gigantic machine, a tank. The sound of the wheels no longer feels like the soothing whisper that used to come from the mother’s five-door room into the courtyard: its sound now pierces the ear and challenges consciousness. If you watch the scenes closely, you might remember Furūgh Farrukhzād’s lines,

ستارههای عزیز

ستارههای مقوایی عزیز

وقتی در آسمان، دروغ وزیدن میگیرد

35Furūgh Farrukhzād, Īmān Bīyāvarīm bih Āghāz-i Fasl-i Sard [Let Us Believe in the Beginning of a Cold Season] (Tehran: Morvarid,1974).دیگر چگونه میشود به سورههای رسولان سر شکسته پناه آورد؟

Dear stars,

Dear Paper Stars,

How can we take shelter in the verses of disgraced prophets?

When lies blow like a wind in the skies?

In the end, the film connects viewers so very honestly with their recent historical experience, using memory, nostalgia, and a choice to create a eulogy for the lost logical stability of time and space, which could not be best defined in an ordinary prose dialogue. The film appears to be divided into several stanzas, each tasked with conveying one aspect of the impact of war and its leaders’ praises of the war on the minds and bodies of young girls. Similar to My Tehran for Sale, the short film Wind, Ten-Year-Old reflects the filmmaker’s childhood experiences. Vafāmihr grew up during the war, and when she was ten, she aspired to fight on the front lines. Before facing harassment from the “pious” professors at the university, she endured the pressure of indoctrination, which had become a policy in the students’ education under the Islamic Republic.

Conclusion

The genre of poetic cinema in Iran is established, and a field of study that can be named Iranian poetic cinema studies is in the making. In her book, The Poetics of Iranian Cinema: Aesthetics, Modernity, and Film after the Revolution, Khatereh Sheibani believes that Iranian film has replaced Persian poetry as the dominant form of cultural expression in that country.36Sheibani, The Poetics of Iranian Cinema (London: I. B. Tauris, 2011). Even if one doubts that such a significant replacement is possible, the fact is that Persian films are the second most important cultural exports in the recent era. In Allegory in Iranian Cinema: The Aesthetics of Poetry and Resistance, Michelle Langford sees trauma as a formative factor in both Iranian poetry and Iranian cinema.37Langford, Allegory in Iranian Cinema (London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2019). Similarly, in her dissertation, Poetic Cinema: Trauma and Memory in Iranian Films, Proshot Kalami ponders the problematics of the representation of the reality of those who have been victimized and traumatized in the post-revolutionary period.38Proshot Kalami, Poetic Cinema: Trauma and Memory in Iranian Films. Dissertation, University of California, Davis, 2008. Such social, generational, and severe trauma might indeed be better detailed and portrayed in film or in novels than in poetry. While none of these works have focused on My Tehran for Sale, in 2011, two years after screening her movie, Grānāz Mūsavī, the director, completed a doctoral dissertation entitled My Tehran for Sale: A Reflection on the Aesthetics of Iranian Poetic Cinema.39Other publications analyzed Mūsavī’s work, e.g., Etienne Forget, L’univers symbolique et son écriture chez Granaz Moussavi (Paris: DEA thesis at Sorbonne University (Paris III), 2004). It explores the relationship between Persian poetry and “the internationally celebrated and inspiring Iranian art-house cinema; and an experimentation of applying such poetic aesthetics in My Tehran for Sale as a reflection on a native poetics.”40Granaz Mousavi, “My Tehran for Sale: A Reflection on the Aesthetics of Iranian Poetic Cinema,” University of Western Sydney, 2011.

Moreover, the movie Vaqt-i Jīgh-i Anār (When Pomegranates Howl, 2020), written and directed by Grānāz Mūsavī and produced by Marzīyah Vafāmihr, renders another wartime story and it uses numerous poetic features to unfold its story. It was selected for Tokyo’s 2021 Film Festival.

Andīshah Fūlādvand has played in several movies and television series and has published two collections of poetry, further connecting the two artforms.41Including, Andīshah Fūlādvand, ‛Atsah-hā-yi Nahs [Portentous Sneezes] (Tehran: Sālis, 2015) and Shilīk Kun Rafīq [Comrade, Shoot] (Tehran, Sālis, 2014). ۳ Āzādah Bīzārgītī, an actor and documentary filmmaker, comes to cinema with profound expertise in literature and literary studies.42See, Āzādah Bīzārgītī, Girīlī, Hadīs-i Bīqarārī-i Laylī (Tehran: Būtīmār, 2016). گریلی، حدیث بیقراری لیلی

Still, the rich reservoir of literary gems provided by Firdawsī, Gurgānī, and no doubt Nizāmī Ganjavī have yet to be artistically explored. Shīrīn by Kīyārustamī was only a small step in that direction, in portraying what this triangle love story can offer cinematically.

With the increasing number of women and women poets entering cinematic fields, with the postrevolutionary focus on women resulting in the feminization of film, the genres of poetry and film become more entangled with one another. Today, one can distinguish a poetic dimension in a film, which is more rooted in the much-revered Persian poetic tradition than in the influence of Italian Neorealism or the French New Wave, as was the case in the pre-revolutionary Iranian New Wave cinema.

Poetry and cinema have also gained a new epistemic aspect in the expression of gender issues. They have become more concise and craftier at the concealment of personal aspiration and pain in social uncertainty, linguistic ambiguity, gender discrimination, and the imposed, damaging duality of public and private life. These features have also shifted the focal motifs from the social toward the individual, to survival, and even escapism. A similar process has occurred in cinema; it is no longer a mere medium for entertaining the consumers or advocating for their cause. It has become a symbolic, metaphorical tool to break the silence and society’s chains. Thus, cinematic production and the representation of fundamental themes regarding gender issues, children, nature, and cultural problems using poetic styles became and continues to be an influential and successful mode.

Cite this article

This article examines the integration of poetry and feminist discourse in Iranian cinema, focusing on the works of Grānāz Mūsavī and Marzīyah Vafāmihr. It traces how directors have used poetic metaphors to critique systemic gender inequality and navigate censorship. The article situates poetic cinema as a hybrid form of resistance, exploring its evolution from sporadic use in pre-revolutionary films to a vital feminist tool in post-revolutionary Iran.