“Primitive Apparatus”: The Dramaturgy of Hyperrealism in the Digital Cinema of ‛Abbas Kiarostami

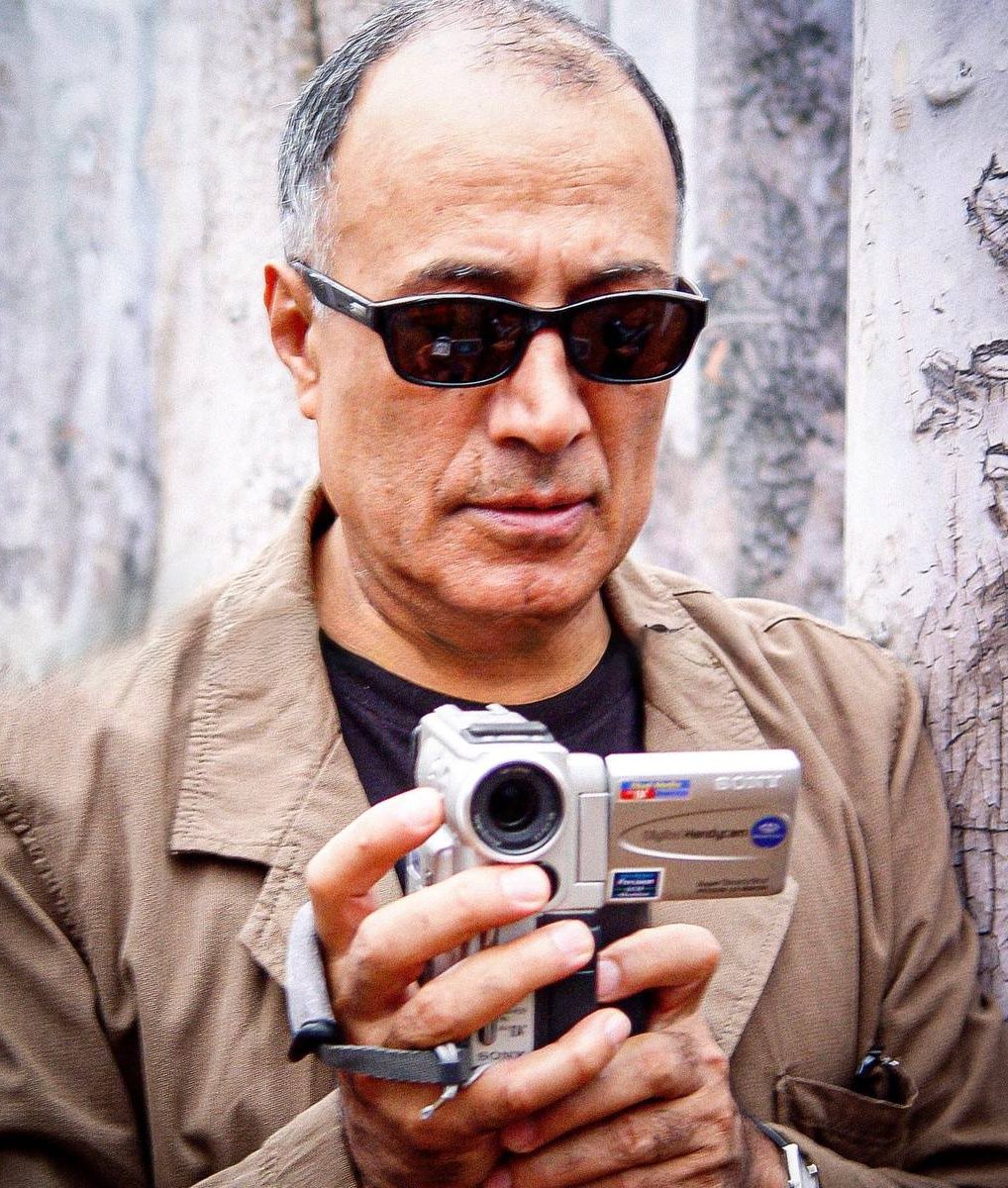

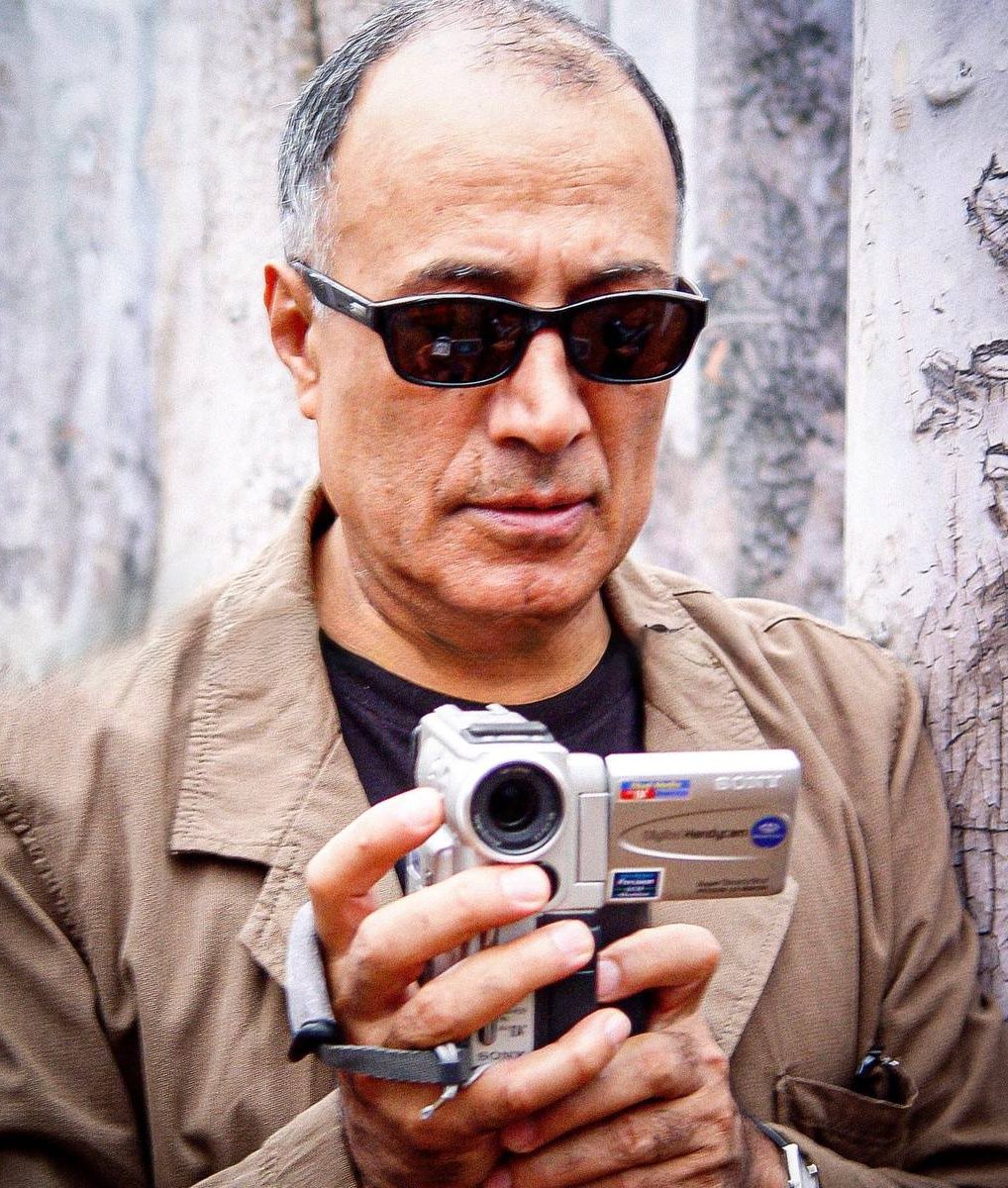

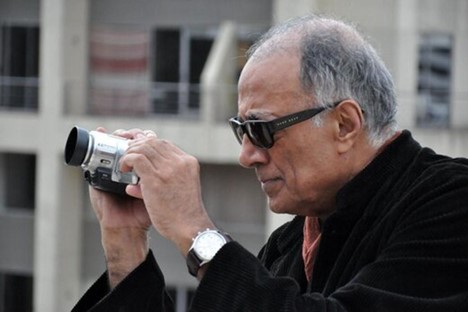

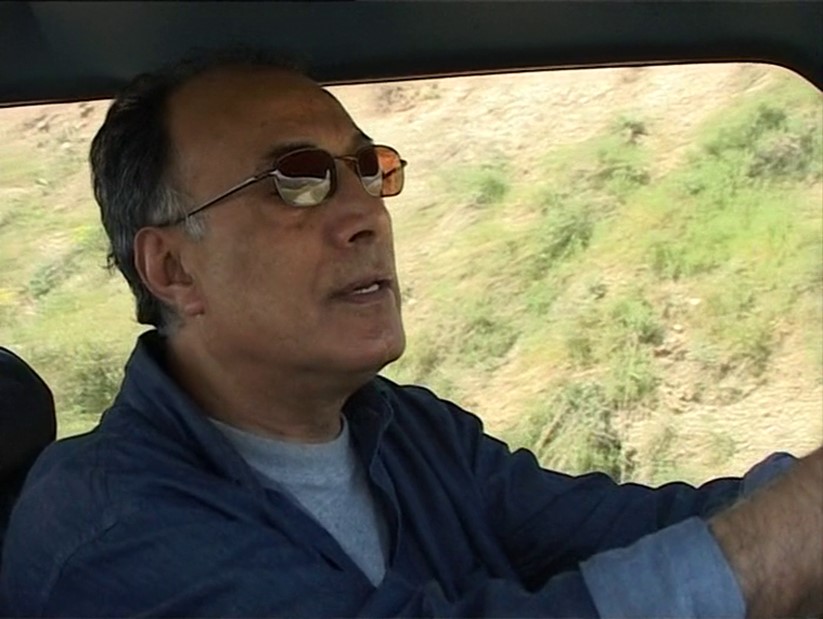

Figure 1: Portrait of ‛Abbās Kiarostami using a digital camera

The transformations brought about by the use of digital tools in cinema have opened at least two opposing trajectories. On one side lies the “complex apparatus”: big-budget Hollywood productions—from Star Wars: Attack of the Clones1Star Wars: Episode II – Attack of the Clones, dir. George Lucas (Beverly Hills, CA: 20th Century Fox, 2002), was the first major feature film shot entirely using digital high-definition cameras (Sony HDW-F900). Widely seen as a turning point in the transition to digital cinema, the film accelerated industry-wide shifts in cinematography, post-production, and projection. For further discussion, see Scott Higgins, Harnessing the Technicolor Rainbow: Color Design in the 1930s (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2007), 185–88; and Michael Allen, “Digital Cinema,” in The Oxford Handbook of Film and Media Studies, ed. Robert Kolker (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), 426–28. to contemporary Marvel franchises—construct visual worlds so saturated with CGI spectacle and layers of post-production that they imply external reality is never reasonably sufficient. On the other side, a group of independent filmmakers—from David Lynch and Lars von Trier to ‛Abbās Kiarostami—have proposed a new path enabled by lightweight video cameras. This approach emphasizes simplified equipment, minimal crews, and a physical closeness between the camera and the subject.

Focusing on Kiarostami’s later digital works—Ten (Dah, 2002), 10 on Ten (2004), Five (2003), and 24 Frames (2017)—this essay argues that he pioneers what I call the primitive apparatus of digital cinema: a deliberately lightweight dispositif whose handheld camera, natural light, and two-person crew lend an air of raw immediacy while quietly scripting what can be seen and heard. The term retools Jean-Louis Baudry’s apparatus theory, shifting attention from the projector–screen complex to a mobile camera–laptop ensemble that still positions the spectator in an ideologically charged field. Conceptually, the primitive apparatus revives Plato’s cave: just as shadows once displaced the Forms, the digital image here precedes its referent, enacting what Jean Baudrillard terms the precession of simulacra. Apparent imperfections—lens flare, clipped highlights, unrehearsed pauses—are therefore not flaws but deliberate signs that circulate as reality itself, setting the stage for what I later describe as primitive hyperrealism. Put differently, in Baudrillardian terms, the primitive apparatus realizes the precession of the simulacrum—the sign that outruns its referent—echoing the Platonic distinction between an archetypal form and its cave-shadow simulacrum.2Plato, Republic VII (514a 517c); Sarah Moss, Plato on the Forms (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 83–90. See also Jean Baudrillard, Simulacra and Simulation, trans. Sheila Faria Glaser (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1994), 1–7.

The roots of this approach lie in Kiarostami’s dramaturgical treatment of the real, which, from his earliest works, arranges events that seem accidental: the dog blocking a boy’s path home in Bread and Alley (Nān u Kūchah, 1970); the sudden fall of a water bucket from a rooftop in Through the Olive Trees (Zīr-i Dirakhtān-i Zaytūn, 1994), seemingly breaking the illusion of directorial control; the pauses and hesitations in conversations throughout Ten (2002); the deliberate procession of ducks in an episode of Five (2003); and even in his final experiment, 24 Frames (2017), in which digitally animated still photographs depict wind, birds, or falling snow as if these occurrences happen on their own. But how can we draw a clear boundary between the precise dramaturgy of seemingly accidental events—meticulously designed to appear objective—and filmed reality itself? What is the relationship between this aesthetic strategy and the historical evolution of cinematic realism? And how does the digital apparatus serve that evolution?

Figure 2: Scenes from the film Bread and Alley (Nān u Kūchah), directed by ‛Abbās Kiarostami, 1970.

Kiarostami, who, from his earliest 16mm films, sought to blur the line between documentary and fiction, can now, with digital tools, take the “engineered accident” to its fullest expression—crafting a reality that appears “more real” than the real itself. This condition recalls the concept of the simulacrum in the thought of the French philosopher Jean Baudrillard, where the image becomes not a mirror of reality, but its self-sufficient substitute.3Jean Baudrillard, Simulacra and Simulation, trans. Sheila Glaser (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1994), 6. On this basis, the central question of the present study may be formulated as follows: how does the use of a lightweight digital camera in Kiarostami’s later cinema give rise to a “primitive hyperrealism” that stands both in contrast to the complex apparatus of Hollywood blockbusters and, at the same time, embodies an alternative expression of the very same cinematic desire to capture and possess the real?

Figure 3: Scenes from the film Where Is the Friend’s House? (Khānah-yi dūst kujāst), directed by ‛Abbās Kiarostami, 1987.

From a historical perspective, the present discussion fills a significant gap: existing scholarship on Kiarostami’s cinema has primarily focused on three distinct domains. The first is the classical Bazinian realism approach, which emphasizes elements such as the use of nonprofessional actors, on-location shooting, and long takes. A key example of this perspective can be found in the work of Mehrnaz Saeed-Vafa and Jonathan Rosenbaum, who, in their book, identify “the astonishing honesty of recording everyday details” as central to their reading of the Koker Trilogy.4Mehrnaz Saeed-Vafa and Jonathan Rosenbaum, Abbas Kiarostami (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2003).

The second group comprises self-reflexive and simulacral interpretations that examine Kiarostami’s works in the context of the crisis of representation and the blending of documentary and fiction. In Volume IV of his A Social History of Iranian Cinema, Hamid Naficy identifies Ten and ABC Africa as key turning points in Kiarostami’s digital cinema, where the boundary between recording and constructing reality is deliberately destabilized.5Hamid Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema, vol. 4, The Globalizing Era, 1984–2010 (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2012), 183. Hossein Khosrowjah, in his doctoral dissertation, describes Close-Up (Nimā-yi Nazdīk, 1990) as a “courtroom metafiction” that invites the viewer to rethink the position of the apparatus and the mechanisms of representation.6Hossein Khosrowjah, “Unthinking the National Imaginary: The Singular Cinema of Abbas Kiarostami” (PhD diss., University of Rochester, 2010), 19.

The third category consists of studies that focus specifically on Kiarostami’s late digital period and his embrace of minimalism. For instance, the chapter titled “The Emergence of Absolute Truth” in Abbas Kiarostami and Film-Philosophy argues that from ABC Africa to 10 on Ten, the small digital camera virtually becomes an active character, thereby challenging “the presumed passivity of the apparatus.”7Brian Price, “The Emergence of Absolute Truth,” in Abbas Kiarostami and Film-Philosophy, ed. Mathew Abbott (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2019), 157-175. Similarly, James Slaymaker, in his analysis of 24 Frames, describes the film as “the apex of the ontology of the originless digital image”—an image nourished not by reality but by digital codes and simulacral logic.8James Slaymaker, “Cinema Never Dies: Abbas Kiarostami’s 24 Frames and the Ontology of the Digital Image,” Senses of Cinema, no. 92 (October 2019). https://www.sensesofcinema.com/2019/feature-articles/cinema-never-dies-abbas-kiarostamis-24-frames-and-the-ontology-of-the-digital-image/. Along the same lines, Justine Remes, in his analysis of Five, describes it as a work that foregrounds the “sleeping spectator” and, through its static images, calls into question the notion of “unmediated perception.”9Justin Remes, “The Sleeping Spectator: Nonhuman Aesthetics in Abbas Kiarostami’s Five: Dedicated to Ozu,” in Slow Cinema, ed. Tiago de Luca and Nuno Barradas Jorge (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2015), 231–242.

Despite the richness of these three lines of inquiry, none has systematically and coherently examined the relationship between Kiarostami’s primitive mode of production—beginning with ABC Africa—and apparatus theory. This article situates itself precisely within this gap and, by introducing the concept of the “digital primitive apparatus,” argues that Kiarostami’s approach is not a lack of technique, but rather a deliberate strategy aimed at critically questioning cinematic reality.

To articulate and assess this concept, Section I offers a brief analysis of the emergence of digital technology and the bifurcation of its two dominant trajectories. Section II, drawing upon three theoretical foundations—André Bazin’s realism, Jean Baudrillard’s theory of the simulacrum, and Jean-Louis Baudry’s apparatus theory—lays out the conceptual framework of the “digital primitive apparatus” and identifies its core features. Section III, through a close analysis of selected scenes from Kiarostami’s four later digital films—Ten (2002), 10 on Ten (2004), Five (2003), and 24 Frames (2017)—demonstrates how lightweight cameras, minimal production crews, and limited/unlimited post-production interventions give rise to a form of “primitive hyperrealism” that guides and reorganizes reality in the moment. The conclusion synthesizes the notion of “primitive hyperrealism.” It proposes this aesthetic as a new critical horizon for apparatus studies, as well as for rethinking the boundary between recording and constructing reality in the digital era.

I. Hyperrealist Cinematic Approaches

Kiarostami once stated explicitly: “Whether in documentary or fiction film, everything we say is nothing but a grand lie we deliver to the audience. Our art lies in telling this lie in a way that makes it believable. Which part is documentary and which part is reconstructed—all of that depends on our method.”10Jean-Michel Frodon and Agnès Devictor, ʿAbbās Kiarostami: Āsār-i bāz [Abbas Kiarostami: L’œuvre ouverte], trans. Tūfān Garakānī (Tehran: Nazar, 2023), 58. This declaration lays bare the dual nature of cinema: on the one hand, the claim of unmediated reflection of reality; on the other, the magical sleight of the image itself.

The roots of this duality can be traced back to the earliest years of cinema. The Lumière brothers, in Workers Leaving the Factory (1895), showcased what might be called “mechanical realism” by fixing the camera in front of everyday reality. In contrast, Georges Méliès, in A Trip to the Moon (1902), replaced external reality with “imagined reality” through optical trickery.11Ulrich Gregor and Enno Patalas, Tārikh-i Sīnimā-yi Hunarī [Geschichte des Films], trans. Hūshang Tāhirī (Tehran: Māhūr, 1989), 27. Despite all subsequent developments in film history, these two approaches remain dominant visual discourses in twenty-first-century cinema. The first, typified by Méliès, manifests in story-driven cinema characterized by montage, narrative manipulation, and the unrestrained distortion of reality—its most prominent expression being the sci-fi genre and Hollywood blockbusters. The second, associated with the Lumières, includes works that present a less distorted representation of reality and fall under documentary cinema, docufiction, or reflexive realist traditions.

Yet what unites both strands are their shared impulse to appropriate and distort reality in favor of their respective discursive systems. With the expansion of the film industry, this appropriation has grown increasingly paradoxical and complex, giving rise to distinct dramaturgical strategies in the construction of cinematic reality.12Richard Rushton, in his dedicated study on cinematic reality that published in 2011 by Manchester University, arrives at a fluid and dynamic concept of filmic reality after critically revisiting the ideas of key thinkers in cinema and philosophy—such as André Bazin, Christian Metz, Stanley Cavell, Gilles Deleuze, Slavoj Žižek, and Jacques Rancière—who have all attempted to theorize the relationship between film and reality, and ultimately, the ontology of cinematic reality. According to Rushton, filmic reality is not merely a representation or reproduction of what we commonly recognize and understand as “reality”; rather, it constitutes a unique mode of creation—an aesthetic and culturally embedded construction of reality that possesses its own logic and expressive power. Hence, the Reality of Film in discussions of digital cinema must be understood as oriented toward the film’s singular visual and sonic grammar, which—when coupled with digital tools—becomes increasingly powerful. Today, these two paradigms have crystallized into what this essay terms the “complex apparatus” and the “primitive apparatus.”

II. The Complex Apparatus: Industrial Hyperrealism

A well-known quote by Georges Méliès captures his attitude toward cinema: “It’s only at the end that I think about a script, a story, or a plot. I can say that the script in itself has no real importance, since I use it merely as a pretext to create visual effects, tricks, or beautifully composed scenes.”13Scott McQuire, “Khiyālpardāzī’hā-yi Hizārah [Millennial Fantasies],” trans. ‛Alī ‛Amirī Mahābādī, in Zībā’ī-shināsī-i Sīnimā-yi Dījītāl [The Aesthetics of Digital Cinema] (Tehran: Fārābī Foundation, 2006), 58.

The complex apparatus is the ultimate expression of this Mélièsian approach in the age of cloud computing: a chain composed of expensive 4K/8K cameras, heavy CGI render farms, motion-capture engines, and graphics-driven sets that together generate such richly detailed worlds that the external world begins to seem insufficient. In Spider-Man 3,14Spider-Man 3, dir. Sam Raimi (Culver City, CA: Columbia Pictures, 2007). for instance, the superficial moral narrative merely serves as scaffolding for the aerial battle sequences; the viewer’s experience centers not on following the drama but on sensory immersion in visual data. Lev Manovich, a leading theorist of contemporary cinema, accordingly describes “digital-age blockbusters” as direct products of computational power, arguing that in such films “data flow replaces narrative event.”15Lev Manovich, “What is Digital Cinema?” in Post-Cinema: Theorizing 21st-Century Film, ed. Julia Leyda, Shane Denson (Reframe books, 2016), https://reframe.sussex.ac.uk/post-cinema/1-1-manovich/. These films are saturated with ungrounded imagery—images produced not to reference reality but to maximize the seductive spectacle of filmic reality, crafted by large-scale image-processing teams.

The world these films portray is not so much an alternate reality as it is a simulacrum of the present one: a fabricated version of our actual world, born within cyberspace and capable of reshaping our belief in what constitutes reality. This apparatus functions as an immediate visual reflection of what Baudrillard termed “the third order of simulacra,”16A detailed discussion of Baudrillard’s theory of the simulacrum will follow in the subsequent sections. in which the image is no longer a reflection of the original, but rather a self-sufficient reality.17Jean Baudrillard, Simulacra and Simulation, trans. Sheila Faria Glaser (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1994), 11.

The Matrix,18The Matrix, dir. Lana Wachowski and Lilly Wachowski (Burbank, CA: Warner Bros., 1999). one of the earliest but most successful cinematic expressions of this hyperreal condition—which is itself a product of its own simulation codes—stands as a theoretical metaphor for this situation: a network of signs that suspends any original referent and compels the viewer to “take the red pill” in order to break from the illusion.19Sarah Wirth, “Realities of the Fake: Baudrillard in the Matrix,” in The Matrix Trilogy: Cyberpunk Reloaded, ed. Stacy Gillis (London: Wallflower, 2005), 159–75.

The reach of the complex apparatus in digital cinema now extends to fully re-creating the bodies and voices of actors who are no longer alive. One early example of this trend was the digital reproduction of Marlon Brando in Superman Returns,20Superman Returns, dir. Bryan Singer (Burbank, CA: Warner Bros., 2006). in which archival footage of the actor was reassembled using advanced CGI techniques to generate an entirely new persona, crafted within a cybernetic space. Whereas two decades ago, the digital removal of Gary Sinise’s legs in Forrest Gump21Forrest Gump, dir. Robert Zemeckis (Los Angeles: Paramount Pictures, 1994). could astonish audiences, Brando’s return to the screen years after his death testified to the growing power of digital simulation.

Technicians at the visual effects company Rhythm and Hues reconstructed his likeness using available footage and software environments, producing a version of Brando that blurred the boundaries between physical presence and computer-generated simulation. This extreme instance of seizing voice and body within cyberspace—enabled by artificial intelligence—demonstrates the extent to which the complex apparatus empowers cinema and visual media to expand the realm of simulacra and replace physical reality with digital models.

III. The Primitive Apparatus: Conscious Minimalism

In contrast to the expensive machinery of CGI, the primitive apparatus relies on technical minimalism and micro-scale production: lightweight MiniDV/HDV cameras or compact but powerful mobile phone cameras, two- or three-person crews, natural lighting, and the omission of post-production effects. This strategy was first articulated in the Dogme 9522On Monday, March 13, 1995, Danish filmmakers Lars von Trier and Thomas Vinterberg met at a café in Copenhagen to draft a cinematic manifesto titled Dogme 95. This ten-point declaration promoted a distinctive mode of filmmaking that, above all, defined its aesthetic in deliberate opposition to the “invisibilizing” apparatus of Hollywood cinema. At the time, few believed that Dogme 95 would, with unexpected speed and reach, become one of the dominant discourses in world cinema, influencing even Hollywood’s visual culture through its radical formal constraints—such as the prohibition of non-diegetic music, lens filters, and special effects; on-location sound recording; and the deliberate avoidance of genre conventions. The manifesto’s insistence on the use of lightweight video-digital cameras—operated exclusively handheld at all times—was one of its most compelling features for young, low-budget filmmakers across the globe, who adopted these tools to create raw, documentary-like cinema. In effect, Dogme 95 not only embraced the limitations and distinctive visual qualities of such cameras, but also helped inaugurate the first signs of what would later emerge as the “primitive apparatus” of digital cinema. see Amin Azimi, “Pīshdar’āmadī bar Kālbadshināsī-i Yak Jaryān-i Sīnimā’ī-i Muʿāsir: Dogme 95 [An Introduction to the Anatomy of a Contemporary Cinematic Movement: Dogme 95],” Farhang va Hunar Quarterly, no. 1 (2005). manifesto by Danish filmmakers Lars von Trier and Thomas Vinterberg in the late twentieth century, but it gained a new philosophical foundation through the digital cinema of ‛Abbās Kiarostami and his approach to reality. By employing lightweight video cameras, Kiarostami managed to disrupt the hegemony of the classical apparatus while preserving—though now at a more creative and reflective level—the “engineered accident” as the central axis of his dramaturgy.

In Ten (2002), two fixed video cameras mounted on the dashboard capture the intense conversations between a divorced mother and her young son. What appears documentary-like is, in fact, the result of a montage of deliberate pauses and the strategic omission of reverse shots—precisely the “believable lie” the filmmaker had described. In Five (2003), Kiarostami takes this approach a step further: five continuous long takes—of crashing waves, a duck parade, the moon’s reflection in water—present seemingly unmediated and everyday images, yet the selection of camera angle, patient waiting, and subtle editing reinsert reality into a mise-en-scène that has been predesigned. The most paradoxical expression of this apparatus culminates in 24 Frames (2017), which begins with Pieter Bruegel’s famous painting and animates it through layers of digital enhancement—wind sounds, birds, falling snow—fabricating a “before” and “after” around the still image to simulate movement. This is a perfect instance of what Baudrillard calls a self-sufficient sign that no longer refers to any original referent.23Jean Baudrillard, Simulacra and Simulation, trans. Sheila Glaser (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1994), 11.

Based on this framework, Kiarostami’s dramaturgical approach within the primitive apparatus can be analyzed on three distinct levels:

First, at the level of pre-filmic staging, the lightweight camera and minimal crew allow real environments—such as a car interior, a beach, or a mountain road—to function as fully realized scenes without transforming into artificial sets. In this approach, natural spaces become the grounds for drama without recourse to set design or conventional cinematic intervention, as if reality itself were appearing directly on screen. Yet this very sense of “immediacy” is the result of a carefully crafted dramaturgy that reduces the visibility of the filmmaking apparatus to a minimum—paradoxically rendering it both visible and invisible at once, thereby intensifying the illusion of the scene’s natural presence.

Second, at the level of temporal composition, Kiarostami eliminates frequent cuts and minimizes camera movement to capture the continuous duration of a given situation. In doing so, he achieves what Gilles Deleuze calls “image-time” in his Cinema 2: The Time-Image,24Gilles Deleuze, Cinema 2: The Time-Image, trans. Hugh Tomlinson and Robert Galeta (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1989), 37. where, after World War II, cinema shifted from privileging action and movement to representing the endurance of time and ruptures in action. The opening shot of Five—featuring a piece of driftwood gently moving with the waves—exemplifies this aesthetic. With no narrative intervention on the surface, the scene invites the viewer not to follow a plot, but to contemplate the extension of time. Here, time becomes its own dramaturgical agent—image-time lived, not narrative time compressed. And yet, this does not preclude poetic, narrative, or even existential interpretations of the shot; indeed, the subtle drift of the wood back into the sea may serve as a quiet metaphor for death, separation, or the cyclical nature of life.

Third, at the level of apparatus visibility, the MiniDV camera—unlike the heavy 35mm camera—does not disappear into a polished cinematic image. Instead, it retains its presence through subtle markers: the reflection of the lens in the glass, the gentle shakiness caused by the car’s movement, and the raw ambient audio that, lacking multichannel boom recording, transmits a soundscape layered with noise. This gentle exposure of the apparatus draws the viewer’s attention to the process of image-making itself. As Hamid Naficy puts it, the lightweight camera becomes an “invisible agent,” no longer passively recording but actively shaping its embedded presence within the scene25Hamid Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema, Volume 4: The Globalizing Era, 1984–2010 (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2012), 311.⸺a tool situated within reality, but without domination or effacing its own trace.

This redefinition of the apparatus responds directly to classical apparatus theory as articulated by Jean-Louis Baudry in his influential essay “The Apparatus: Metapsychological Approaches to the Impression of Reality in Cinema.” Baudry argued that the material conditions of cinematic projection—the darkened theatre, the fixed position of the spectator, the singular perspective of the camera, and the silver screen—are not neutral elements but ideological constructs.26Jean-Louis Baudry, “The Apparatus: Metapsychological Approaches to the Impression of Reality in Cinema,” in Narrative, Apparatus, Ideology: A Film Theory Reader, ed. Philip Rosen (New York: Columbia University Press, 1986), 299–318. The classical apparatus, by masking its technical mechanisms, creates the illusion of unmediated access to reality. Kiarostami, by contrast, challenges this ideology through his commitment to primitive production aesthetics: a lightweight video camera instead of 35mm film, the windshield as a screen, and ambient noise instead of professional sound design. In his films, the apparatus is not erased but remains subtly—yet perceptibly—within the viewer’s sensory experience, thus provoking a critical awareness of how cinematic reality is produced.

At this point, it becomes clear how Kiarostami’s dramaturgical primitivism is inevitably entwined with Jean Baudrillard’s concept of the simulacrum. The image, here, is not an unmediated reflection of reality, but a constructed, self-sufficient, and unreferenced structure that—through its coupling with digital tools—appears so convincingly real that it is mistaken for reality itself. As Baudrillard explains, simulacra emerge when the image no longer functions as a sign of reality, but rather becomes its autonomous substitute.27Jean Baudrillard, Simulacra and Simulation, trans. Sheila Faria Glaser (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1994), 12. Thus, Kiarostami’s primitive apparatus—through its minimalist spatial registration, durational temporalities, and subtle exposure of the filmmaking apparatus—produces a form of minimalist hyperrealism that holds the viewer in suspense between reality and simulation. Table 1 summarizes the fundamental distinctions between these two strategies.

This reliance on primitive production economies—micro-budgets and small crews—also enables a mode of authorship and creative autonomy within this kind of filmmaking. The unvarnished recording of drifting, fragmentary conversations in Ten, or the filmmaker’s calm, reflective articulation of his thoughts and methods in 10 on Ten, demonstrate how Kiarostami’s “digital notebook” allowed him to film extensively and, through the simplest of edits, construct—or discover—precisely the engineered accident he desired. Such primitivism stands in sharp contrast to the constraints imposed by the high-cost production models of the complex apparatus. Yet, it may, in its power to render what never happened entirely believable, succeed even more effectively than large-scale blockbusters. Reexamining Kiarostami’s later cinema thus offers an opportunity to pose more profound questions about the aesthetics, ethics, and potential of the primitive apparatus.

Table 1. Fundamental Differences Between the Complex and Primitive Apparatus

|

Index |

Complex Apparatus |

Primitive Apparatus |

|

Recording Technology |

4K/8K large-sensor cameras, crane rigs, motion capture |

Mini DV/HDV, mobile phone, handheld stabilization |

|

Post-production |

CGI render farms, multilayered compositing |

Light editing, minimal color correction |

|

Apparatus Politics |

Concealing the camera within the spectacle |

Revealing the trace of the camera |

|

Realism Strategy |

Data excess and exaggeration → “Extended Reality” |

Simplicity and engineered chance → “Minimal Reality” |

|

Ideological Function |

Fixing the viewer in immersion (spectacle) |

Engaging the viewer in doubt and reflection (self-reflexive) |

Baudrillard, Kiarostami’s Cinema, and the Simulacra: Hyperreality28Hyperreality refers to a condition in which signs derived from reality (the signifiers) overpower and ultimately replace reality itself (the signifieds). At the same time, these signs refer endlessly to one another, creating a perpetual circulation that conceals the absence of any actual referent—substituting a world built of illusions and fabrications. These illusions are not only of our own making but are also produced by powers capable of generating “images,” “fantasies,” and “concepts” on our behalf. This includes everything we constantly consume, from Coca-Cola and chewing gum to toothpaste, as well as the images of women on magazine covers and advertisements, or of “movie stars” that become imprinted on our minds. As a result, the perceptions we hold about “society,” “beautiful men and women,” “heroes,” “happiness,” “pleasure,” “science,” “art,” and virtually everything else are mere images—void of any anchoring in actual reality.

Following the delineation of the two opposing forms—the primitive and the complex apparatus—this section seeks to explain how, despite their stark differences in scale and technology, both logics in ‛Abbās Kiarostami’s digital films converge at a single semiotic point. To understand this convergence, Jean Baudrillard’s concepts of the “simulacrum” and “hyperreality” offer the most effective analytical framework. In Baudrillard’s postmodern logic, the implosion of the boundaries between image and reality proceeds to such an extent that signs detach from external referents and begin to operate within a self-contained system, wherein the image no longer reflects reality but replaces it.

In Simulacra and Simulation, Baudrillard outlines four stages in the collapse of the real into the simulacrum: (1) the faithful reflection of reality; (2) a distorted but still referential representation; (3) a simulation that appears real but has no objective referent; and (4) the complete dominance of the sign over reality—what Baudrillard terms hyperreality, wherein the image appears “more real than the real.”29Jean Baudrillard, Simulacra and Simulation, trans. Sheila Faria Glaser (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1994), 10-12. At this final stage, truth is no longer external, but rather the product of an internal play of signs.

This structure allows us to understand why both Kiarostami—through the simplification of the apparatus and the creation of engineered accidents—and Hollywood blockbusters—through the most elaborate digital effects—ultimately produce experiences that seem “more real than reality” to the viewer. Both arrive, by opposing means, at the very hyperreality Baudrillard describes.

The nature of hyperreality in the visual and technological arts—particularly cinema—emerges from a dual process: on the one hand, the disappearance of reality, and on the other, the erasure of the boundary between image and phenomenon. Baudrillard insists that in the contemporary world, everyday life, political conflict, and even natural phenomena are increasingly perceived first as images, before they are directly experienced. In this condition, signs, detached from their referents, become self-sufficient, and the image precedes the event. The result of this severed referentiality is the collapse of the indexical validity of the image:30Jean Baudrillard, Simulacra and Simulation, trans. Sheila Faria Glaser (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1994), 9-13. the image no longer serves as a trace of reality. However, it operates autonomously, governed by its own internal rules and regulations. As Khalili Mahani puts it, in such a condition, images are “released into a dizzying desert” where no historical evidence of authenticity remains.31Najmeh Khalili Mahani, “The Work of Cinema in the Age of Digital (Re)production,” Offscreen 7, no. 10 (October 2003): 14.

This gradual decline in the authority of reality within the image corresponds to the history of cinema’s technological transformations—from rear projection and glass matte painting in classical cinema, to blue screens, composited special effects, and finally full-scale CGI rendering. Cinema has consistently evolved toward reducing its dependence on external reality. In digital cinema, as Lev Manovich explains “reality can now be endlessly reconstructed and edited anew.”32Lev Manovich, The Language of New Media (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2001), 48. Consequently, the relationship between image and reality is reversed: cinema, once understood as a mirror of the world, has transformed into a system of digital codes that no longer reflects reality but instead precedes and replaces it—a condition Baudrillard identifies as the very essence of hyperreality.

This hyperreal logic—whether through the complex apparatus of photorealistic rendering or the minimalist apparatus of lightweight digital cameras—provides a new space for the suspension of reference and the stabilization of self-contained signs. One can trace this approach even in Kiarostami’s pre-digital period. Close-Up (1990) is a paradigmatic example: a film that reconstructs the real-life case of Husayn Sabziyān—who impersonated director Muhsin Makhmalbāf—and merges real courtroom footage with the actual individuals performing as themselves, thereby erasing the boundary between documentary and fiction so thoroughly that representation becomes more compelling and more convincing than the event itself. In such a case, representation becomes a medium for accessing a more profound truth.

Digital tools amplify this representational logic through the boundless simulation of signs. In Kiarostami’s digital cinema—from Ten to 24 Frames—we encounter a cinema of simulation that, through its dramaturgical processes, seeks to generate new experiential encounters with the real. This is a cinema that suspends the external referent, renders its signs autonomous, and invites the viewer’s perception to participate in hyperreality.

In what follows, we will examine four of Kiarostami’s digital-era films through the lens of their dominant dramaturgical strategies—approaches that, while formally and technically distinct, all operate toward producing a hyperrealist experience of reality.

Primitive Dramaturgies

The spark that marked Kiarostami’s transition to the primitive digital apparatus was struck in ABC Africa (2001), when he first referred to lightweight MiniDV cameras as his “daily notebook” and began experimenting with unmediated image-making.33Jean-Michel Frodon and Agnès Devictor, ʿAbbās Kiarostami: Āsār-i bāz [Abbas Kiarostami: L’œuvre ouverte], trans. Tūfān Garakānī (Tehran: Nazar, 2023), 180–182. This experience, by abandoning the expensive infrastructure of classical filmmaking—lighting, booms, dollies—enabled him to bypass the professional production network and reduce the vast machinery of cinema to a pocket-sized camera. From the perspective of apparatus theory, particularly in the reading of Jean-Louis Baudry, such a shift is not merely a change in tools; it is a redefinition of a material–ideological system that organizes the viewer’s gaze. In this tradition, the apparatus is more than the camera and the screen—it is a system whose technical operations regulate the spectator’s subject position, the possibility of perceiving reality, and even the very concept of representation.

Here, the lightweight camera becomes not just a recording device, but a sign of the transformation in the relationship between reality and media. When Kiarostami uses a car windshield as a framing device or substitutes raw environmental sound for professional audio mixing, what is altered is not only the form but the structure of perception and the regime of truth proposed by the primitive apparatus. This condition, described in Table 1 as “minimal reality,” forms the cornerstone of the primitive dramaturgy in his late cinema.

To evaluate this minimalist hyperrealism in Kiarostami’s work, we now examine four of his digital films, each analyzed through the lens of its dominant dramaturgical orientation:

- Ten (2002) and 10 on Ten (2004) – The dramaturgy of direction and performance;

- Five (2003) – The dramaturgy of observation and waiting;

- 24 Frames (2017) – The dramaturgy of post-production animation.

In each case, we will first describe the tools and production economy, then demonstrate how the executional design either eliminates the referent or controls it so precisely as to produce a self-sufficient sign—and finally, how this process elevates the “sense of reality” to a hyperreal level. This analytical path will reveal that the primitive apparatus, without recourse to complex effects, nonetheless fulfills cinema’s enduring desire to possess the real—only now through a minimalist and dramaturgical simulacrum.

Methodological note: To test my claim that Kiarostami’s digital oeuvre pivots between complex and primitive apparatuses, I adopt a purposive sampling strategy. I analyze selected scenes from Ten (2002), 10 on Ten (2004), Five (2003), and 24 Frames (2017) that satisfy four criteria: (i) explicit minimalist technique (handheld camera, natural light, long takes); (ii) varying degrees of authorial intervention, from direct on-camera dialogue (Ten / 10 on Ten) to near-total effacement (Five); (iii) availability of corroborating materials such as production interviews, scripts, or behind-the-scenes footage; and (iv) retention of “raw” visual artifacts—unrehearsed action, lens flares, overexposed highlights—that signal a refusal to reshoot or correct. These scenes chart inflection points along a continuum from industrial complexity to portable minimalism, demonstrating how hyperreal dramaturgy emerges when the primitive apparatus exposes, rather than conceals, its imperfections.34All timecodes refer to the Artificial Eye DVD editions unless otherwise noted.

Ten: Invisible Direction and the Performance of Engineered Accident

Ten (2002), Kiarostami’s first fully digital film, interweaves the experience of invisible direction, minimalist micro-budget production, and the carefully constructed representation of chance. Its dramaturgy lies at the intersection of docufiction and cinéma vérité, dissolving the boundary between reality and performance. Two MiniDV cameras are mounted on the dashboard of a white Pride (a compact Iranian car), capturing a series of episodes featuring a divorced woman in conversation with her young son, her sister, a heartbroken friend, an elderly pilgrim en route to a shrine, a sex worker, and a young woman yearning for her lover. During filming, Kiarostami reportedly squeezed himself into the back seat or, in some instances, took the driver’s place, directing the flow of scenes and guiding the actors from within the car.35Abbas Kiarostami, “Kiarostami on Ten,” in Ten DVD Booklet (London: BFI, 2003). https://zeitgeistfilms.com/media/films/89/presskit.pdf

He likened this method to stage direction in theatre: “You have to prepare everything in advance… You can’t intervene in the middle of the performance as a director, but you can whisper things to them, and maybe now and then remind them what else they should say…”36Colin Grant, “Interview with Abbas Kiarostami on Ten,” trans. Farshīd ‛Atā’ī, Gulistānah Magazine, no. 44 (2002): 76-77. Kiarostami also emphasized that all the dialogue in Ten was improvised—none of it was prewritten.37In improvisational theatre training, one common technique involves the director or instructor providing the actor only with the starting point and endpoint of a dramatic situation. The actor is then asked to improvise the trajectory of action from beginning to end, based on the psychological, social, and motivational characteristics of the role. This method, rooted in modern theatre pedagogy, allows actors to explore and experience dramatic relationships and emotional pathways within a defined space—free from reliance on a written script. For further reading, see Viola Spolin, Improvisation for the Theatre (Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 1999); Keith Johnstone, Impro: Improvisation and the Theatre (London: Routledge, 1981). Weeks before shooting, he would discuss the scenarios with the actors and encourage them to respond spontaneously within the framework of their roles.38Colin Grant, “Interview with Abbas Kiarostami on Ten,” trans. Farshīd ‛Atā’ī, Gulistānah Magazine, no. 44 (2002): 77. Accordingly, every improvised line or action is, in effect, the product of live dictation and precise directorial control. Deliberate pauses—such as the child peering outside, the mother shifting gears, or the sister staring into the void—are best understood as “engineered accidents.”

This method of direction eliminates the documentary status of the off-screen referent and renders the performance self-sufficient. In the final part of episode 10,39Ten, dir. ‛Abbās Kiarostami (Paris: MK2, 2003), DVD, 00:17:55–0018:45. for example, the woman gestures and converses with a man who is pulling his car out of a parking spot. In this scene, deliberate pauses coincide with ambiguous, off-screen movements. The use of in-car digital cameras and the absence of a 35mm camera crew surrounding the actors result in performances that, in line with the film’s primitive dramaturgy and hyperreal aesthetic, frequently verge on genuine, unsimulated behavior. A striking example occurs in episode 9,40Ten, dir. ‛Abbās Kiarostami (Paris: MK2, 2003), DVD, 00:28:52–0029:03. when the sister predicts, just seconds before it happens, that the car will hit a bump in the road. When it does, exactly as foretold, both she and the woman smile—a subtle acknowledgment of a mistake likely repeated during previous takes.

Mehrnaz Saeed-Vafa, in her aesthetic analysis of the film’s visual style, notes that Kiarostami’s use of DV cameras gives Ten “some of the intimacy of home video and some of the covertness of surveillance footage—people behave as if there is no camera, resulting in moments that seem candid and unmediated, even though everything is pre-planned.”41Mehrnaz Saeed-Vafa and Jonathan Rosenbaum, Abbas Kiarostami (Urbana: University of Illinois Press,2003):45. This performative quality, coupled with the visual texture of the film and elements like the crescendo of the car engine or the unintelligibility of the friend’s sobbing dialogue,42Ten, dir. ‛Abbās Kiarostami (Paris: MK2, 2003), DVD, 00:66:00–00:72:00. creates a sensory layer that stems from a process where reality is not represented but simulated for the camera. This aesthetic quality is precisely what generates the suspended space between the real windshield and the cinematic screen.

Indeed, it is these physical slippages and sensory impressions—combined with the sunlight that continually enters the frame as overexposed, and at times green-tinted, patches (see Figures 4 and 5)—that render the frame’s boundary perceptible, seize the viewer’s perceptual reality, and activate what might be called the apparatus’s index of “reality-effect.”

Figure 4: Frame grab from Ten (Dah), directed by ‛Abbās Kiarostami, 2002. Courtesy of MK2.

Figure 5: Frame grab from Ten (Dah), directed by ‛Abbās Kiarostami, 2002. Courtesy of MK2.

Figures 4 and 5 are examples of lens flares preserved by Kiarostami during both shooting and editing; these flares recur throughout the film as part of its primitive aesthetic.

Kiarostami frequently disregards the conventional shot–reverse shot grammar in this film—a technique typically used in dialogue scenes to alternate between the speaker and the listener. Instead, he often lingers on the listener’s face for extended periods, while the speaker remains offscreen. This approach focuses the viewer’s attention on subtle, unspoken, and internal reactions, encouraging the audience to imagine the offscreen presence of the other character. For instance, in the film’s opening argument between the mother and son, we see only the boy’s face for a considerable duration as he shouts, while the mother’s voice is heard from the driver’s seat. This deliberate composition amplifies our empathy with the child’s psychological turmoil and simultaneously produces an illusion of realism—after all, in everyday life, when we sit in the front passenger seat, we often look straight ahead or out the window, rather than directly at the person next to us. These compositional choices eschew theatrical conventions and instead simulate the visual experience of an actual car ride, reinforcing the film’s realist effect.

The film’s lighting is based entirely on natural sources—daylight or streetlamps filtering into the car. Rather than correcting for exposure, Kiarostami embraces these conditions. What is preserved in the image is the atmospheric light of Tehran, even if the frame is slightly blown out or oversaturated. In nighttime sequences, Kiarostami even allows the image to fall into near-blackness, foregrounding the dialogue as something to be heard rather than seen. This dramaturgical choice extends to the use of blurred or out-of-focus imagery during moments of heightened emotional intensity.

Figure 6: Frame grab from Ten (Dah), directed by ‛Abbās Kiarostami, 2002. Courtesy of MK2.

In episode 243Ten, dir. ‛Abbās Kiarostami (Paris: MK2, 2003), DVD, 00:87:00–00:90:12.—chronologically the penultimate scene of the film—a young woman, devastated by the impossibility of reuniting with her lover, has shaved her head. She is filmed in an out-of-focus shot that produces a blurred, amateurish, and primitive image—visually distinct from the rest of the film (see Figure 6). It is as though, for Kiarostami, this deliberate shift toward visual primitivism reflects a nuanced gradation of directorial intervention during both filming and editing. In this moment, the blurred image becomes a powerful conduit for conveying the girl’s emotional devastation—transmitting her inner opacity to the viewer on an unconscious level.

This effect is amplified by the film’s invisible editing and the deliberate pacing of its cuts. The camera lingers on the girl’s face for an extended period as she cries with a bitter smile and removes her headscarf, revealing her shaved scalp as a reaction to heartbreak. The shot remains uninterrupted, allowing her emotional arc to unfold without cinematic interference. Only when she lapses into silence does Kiarostami cut away—allowing the silence to resonate. In such moments, the absence of overt technique—no dramatic cuts, no music—intensifies the hyperrealist effect. The viewer appears to witness something raw and unfiltered. The characters use their real names and express real emotions, yet they do so within a situation carefully constructed by Kiarostami. The result is a dissolution of the boundary between reality and performance—a distinction that becomes irrelevant to the viewer. What we see are signs of reality that no longer refer to anything beyond themselves: they are the reality we come to associate with these individuals.

In Baudrillard’s logic, hyperreality arises when the sign overtakes the referent and conceals that displacement. The car-interior segment in Ten (episode 3, 00:22:30–00:23:17) illustrates the point: two dashboard-mounted DV cameras record roughly forty-seven near-unbroken seconds of everyday dialogue, accompanied only by the ambient hum of traffic. By eschewing single-camera shot/reverse-shot editing, non-diegetic music, and conspicuous cuts, the scene leads the viewer to accept the camera’s narrow digital window—rather than any verifiable Tehran street beyond the frame—as the ground of truth. The result is an image that stands in for itself and thus becomes more real than the objective reality. Moments later (c. 00:23:50) a sudden engine rev exposes the recording circumstance and briefly restores the referent, showing that hyperreality depends not merely on subtracting classical filmic cues but on keeping the sign decisively ahead of the real without leaks.

André Bazin once wrote: “Realism in art can only be achieved through artifice.”44André Bazin, What Is Cinema? Vol. 2, trans. Hugh Gray (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1971), 26. Ten is a prime example of this principle: artifice hidden within improvisation, in a controlled location and tightly edited structure, strips away the cinematic frame and places fragments of life before us. What the viewer experiences is an encounter with invisible structures of direction and the removal of external referents: a full-fledged strategy of simulating the real. With the use of minimalist digital tools, Kiarostami transforms the ordinary interior of a car into a philosophical stage—one in which reality is not only reconstructed but, through dramaturgy and simulacra, newly created.

10 on Ten: An Intratextual Manifesto

One year later, in 10 on Ten (2003),4510 on Ten, dir. ‛Abbās Kiarostami (Paris: MK2, 2004), DVD. Kiarostami documented the process of invisible direction in a self-reflexive format. While driving a car through the winding dirt roads of the final location used in Taste of Cherry (Ta‛m-i Gīlās, 1997), he appears to speak extemporaneously about his filmmaking method in Ten. However, in many moments, his assistant feeds him lines through a hidden earpiece, reading from a prewritten text—thereby engineering the realism of the situation. The clearest evidence of this occurs around minute 54 of the film (see Figure 7), when Kiarostami, mid-explanation of his views on the use of props, suddenly pauses. In the silence that follows, a voice can be heard whispering the next line into his ear before he repeats it aloud.

This technique echoes a method widely used in documentary and particularly in verbatim theatre,46Verbatim theatre is a form of documentary theatre in which the performer often listens to interview recordings through an earpiece and delivers the exact words in real time. This technique, popularized by companies such as London’s Recorded Delivery and practitioners like Alecky Blythe, shifts emphasis from interpretation to replication, producing a sense of immediacy while subtly foregrounding the constructed nature of representation. See Carol Martin, Dramaturgy of the Real on the World Stage (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010), 9–12. in which actors receive lines through an earpiece and perform them immediately, without rehearsal or interpretation. In this format, representation is no longer based on repetition or recreation, but on real-time enactment. This method alters the “precision” of reality by generating an imperceptible distance between the origin and its representation.

The convergence of invisible direction and the minimalist production economy in Ten, and its theoretical reflection in 10 on Ten, produces what Baudrillard describes as the “third stage of the simulacrum”: the moment when the image no longer reflects reality but replaces it.47Jean Baudrillard, Simulacra and Simulation, trans. Sheila Glaser (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1994), 6. Primitive dramaturgy—through the elimination of the technical crew, the fixation of the frame, and the engineering of real time—stages the performance in such a way that the viewer’s experience of the external world is, in that moment, subsumed by the image. This is why, as Duclos observes, the scene of the mother-son argument is “disturbingly accurate and precise.”48Gilles Duclos, “Ten ou la vérité inattendue,” Positif 507 (September 2003): 44–47. In an interview with Le Monde, Kiarostami explicitly states: “I don’t find reality—I construct it. But the audience must forget that I constructed it.”49Jacques Mandelbaum, “Abbas Kiarostami: ‘Je ne trouve pas la réalité, je la fabrique’,” Le Monde, May 2, 2003. This admission, reinforced by the scene that occurs at the film’s fifty-fourth minute, shows how the “believable falsehood” functions dramaturgically: the off-screen prompter who feeds Kiarostami lines through an earpiece is never shown, and we, unwittingly, step into that guiding role; the brief silence forces us to supply the following line and thus complete the simulacrum.

Figure 7: Frame grab from 10 on Ten, directed by ‛Abbās Kiarostami, 2004. Courtesy of MK2.

In Baudrillard’s terms, this moment exemplifies the third order of simulacra, in which “signs no longer point to any reality whatever; they are their own pure simulacrum.”50Jean Baudrillard, Simulacra and Simulation, trans. Sheila Glaser (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1994), 6. The whispered prompt is precisely such a sign: it sounds improvised, yet its source is a pre-written text relayed through an earpiece. Mistaking this scripted direction for spontaneous speech, the spectator is drawn into a dramaturgy of improvisational illusion—a paradigmatic instance of minimalist hyperrealism.

Ten and 10 on Ten together embody the “direction/performance” dramaturgy of the primitive apparatus: total control over the event with the simplest tools. They exemplify how lightweight cameras and micro-production economies can fulfill cinema’s long-standing desire to seize the real—through the construction of a self-sufficient simulacrum. In the next section, we will see how Kiarostami continues this same pursuit in Five, through a dramaturgy of “observation and waiting.”

Five: The Dramaturgy of Observation and Waiting

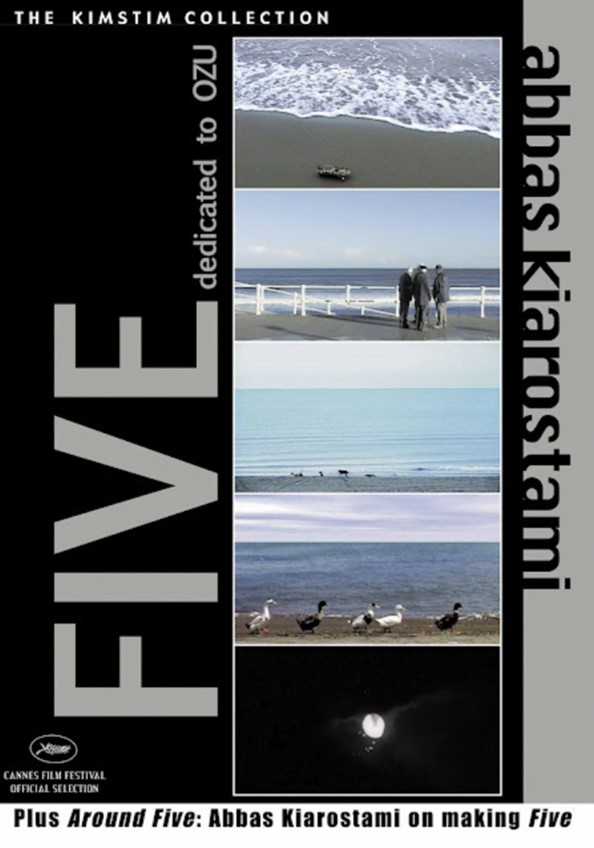

After his experiment with invisible direction in Ten, Kiarostami takes a more radical step in Five: Dedicated to Ozu (see Figure 8), eliminating actors, dialogue, and camera movement. Using a small digital video camera, he constructs five long takes devoid of any post-production layering, featuring only raw ambient sound. This minimalist choice, as Jean-Louis Baudry would argue, transforms the “material conditions of projection”: the viewer, instead of following narrative action, is compelled to observe time itself.51Jean-Louis Baudry, “The Apparatus: Metapsychological Approaches to the Impression of Reality in Cinema,” in Narrative, Apparatus, Ideology: A Film Theory Reader, ed. Philip Rosen (New York: Columbia University Press, 1986), 299. In this context, the digital primitive apparatus becomes a device for observation and waiting—a camera that does not conceal itself, but through its stillness, invites the viewer to engage perceptually.

Episode 1 – The Driftwood and the Waves

A piece of driftwood repeatedly washes ashore, only to be pulled back by the retreating tide. Beneath the apparent stillness, the simplicity of the scene produces a subtle kind of digital dynamism: is this repetition natural, or the result of invisible editing? It was later revealed that a thin string had been attached to the wood and digitally removed in post-production—an instance of the “engineered accident” that erases the referent and renders the sign self-sufficient: in the driftwood shot of Five (00:00:00–00:06:28), the floating plank is transfigured into a metaphorical sign that serves Kiarostami’s conceptual design, while its material referent—grain, weight, smell—slips from awareness until only the hypnotic shimmer of light on water endures. In the behind-the-scenes documentary Around Five,52Around Five (bonus documentary on Five Dedicated to Ozu), dir. ‛Abbās Kiarostami (Paris: MK2 Éditions, 2003), DVD. included as a bonus on the MK2 DVD release, Kiarostami explains the process: a small amount of explosive material was embedded in the wood to break it in half at a predetermined moment; one half was discreetly pulled out to sea using a transparent fishing line controlled by the crew, while the other half was arranged to remain on the shore (00:7:45–00:9:20). Kiarostami states that his goal was “to deceive the eye while remaining truthful to the viewer.”

Jonathan Rosenbaum, in his analytical note on the same documentary, writes: “What appears completely natural is in fact the product of a precise and invisible engineering hidden behind the calmness of the image.”53Jonathan Rosenbaum, “Abbas Kiarostami’s Five Is Finally Available,” jonathanrosenbaum.net, December 29, 2006, https://jonathanrosenbaum.net/2024/11/abbas-kiarostamis-five-is-finally-available-chicago-reader-blog-post-122906/. In another section of the documentary, Kiarostami emphasizes that his method was experimental, and that at times he would simply turn on the camera, leave the scene, or even fall asleep (00:19:19–00:19:40), allowing the moment to unfold on its own. This attitude toward time echoes Andy Warhol’s technique of recording real time with minimal intervention. Yet, as the driftwood episode illustrates, Kiarostami would subtly intervene when necessary to ensure that nature performed according to his vision. Thus, this first episode is not only a testament to the filmmaker’s patience and observational stance but also a clear example of minimalist intervention toward the construction of a hyperreal simulacrum—one that seamlessly fuses reality with mise-en-scène.

Figure 8: DVD cover of Five: Dedicated to Ozu (2003), directed by ‛Abbās Kiarostami, released as part of The KimStim Collection. The composite image shows five key shots from the film: the sea, passing figures, ducks, and the moon reflected on water. (Source: The KimStim Collection, DVD cover)

Episode 2 – Beachside Passersby

In this episode, the camera is placed in a fixed position beside a seaside walking path. In the documentary About Five, Kiarostami remarks: “I just found the right spot for the camera and waited for people to come and go.”54Around Five (bonus documentary on Five Dedicated to Ozu), dir. ‛Abbās Kiarostami (Paris: MK2 Éditions, 2003), DVD, 00:12:30–00:13:05. “Finding the right spot” here means engineering a visual angle that transforms the landscape into a performative scene: the wooden planks of the boardwalk form linear perspective lines, and passersby—mostly middle-aged and elderly men and women—enter the frame at nearly regular intervals, then exit from the opposite corner. The compositional rhythm of “pause – emptiness – entrance” creates an invisible tempo that recalls Ozu’s mise-en-scène, where minimal character movement acquires dramatic significance solely due to the stability of the frame.

The dominant sound of ocean waves (slightly enhanced in the sound mix) provides a musical sense of cohesion, making all movements before the camera—including the entry of two pigeons and their slow circling—feel like part of a dreamlike sequence observed from a distance. In the absence of narrative, the viewer constantly wonders: Is this orderly repetition, this steady flow of pedestrians, merely accidental, or is it the filmmaker’s orchestrated invitation? Or perhaps both?

Here again, by focusing on the smallest of actions—in this case, walking—we become pure observers. The dramaturgy of waiting evolves into an open-ended anticipation for something to happen—a collision, an anomaly—but the film merely extends the texture of everyday life, even when a small gathering of elderly men eventually forms at the episode’s end. This suspense in eventfulness produces a corresponding suspension of reality: ordinary life is rendered theatrical, as if each passing moment might reveal a hidden meaning.

From the Deleuzian perspective of the time-image, this is a pure image-time: a frame that shows time directly, without the mediation of dramatic action. Instead of following narrative progression, we experience the flow of time and its minute internal variations. The sheer duration of the fixed shot invites a form of perceptual meditation, making each seemingly insignificant moment feel charged with significance.

Episode 3 – Dogs on the Shore

In this episode, a static camera observes a quiet corner of the beach, where a few stray dogs gently roam through the sand, lie down, or move in and out of the frame without any apparent purpose. The soft waves in the background, the mellow sunlight—which eventually, through visual gradation, fades into a complete whiteout—and the continuous sound of the sea compose an image devoid of any dramatic action, yet one that invites the viewer to linger and reflect. Nothing decisive happens within the frame, and yet time flows in a way that evokes a sense of life’s continuity in the absence of narrative.

Here, as in the other episodes, Kiarostami removes the human element and centers dramaturgical control around pure observation. With the frame locked, every small change—dogs repositioning themselves, subtle shifts in the angle of light, or the faint murmur of waves—becomes a potential event. The final composition is the result of spatial engineering and patience: patience with nature, in waiting for something to happen that perhaps never will.

Episode 4 – The Ducks’ Procession

In the duck sequence, Kiarostami deploys the same “dramaturgy of observation and waiting,” this time infused with a touch of gentle humor. A fixed camera frames a shallow strip of beach; in the background, waves gently roll forward and back, and the monotonous sound of water fills the entire soundscape. Suddenly, a single duck enters from the left, walks across the frame, and exits. A moment later, two more ducks follow the same path; then three or four more. Each time a small group crosses, the frame remains empty for a few seconds, and this “empty interval” creates a subtle suspense: the viewer, held in stillness and silence, waits without knowing what might happen next.

Finally, after a longer pause, a large flock—more than ten ducks—suddenly rushes in from the right, moving in the opposite direction. It is a surprising and whimsical moment, simultaneously amusing and disruptive to the previously established rhythm.

The entire charm of the scene lies in this playful manipulation of “unrewarded anticipation”: empty time becomes content itself, and each new entrance is simply another chance to extend duration. Kiarostami need not intervene overtly—except to amplify the ducks’ footsteps slightly in the audio mix, enhancing the humor of the setup. The chosen angle, the sound, and the duration of the shot are enough to transform the animals’ seemingly random movements into a hidden narrative structure.

Episode 5 – The Reflection of the Moon on the Lake

The fifth episode—“The Inverted Moon”—is the final and longest shot in Five, running nine minutes and two seconds in the MK2 DVD release, and it pushes the dramaturgy of observation and waiting to its extreme. In the vast darkness of night, the static camera frames only the still surface of a pond; what we see is not the moon itself, but its shimmering reflection, and the slow movement of clouds. With the first croak of a frog, the scene begins to take shape: both sound and image serve as mediators, yet neither offers a direct referent. The sky and the shoreline—like some unspoken origin—are excluded from the frame. Kiarostami deliberately directs the viewer’s gaze toward a “representation of representation,” suspending the indexical function of the image from the outset. Each subtle ripple—whether caused by the leap of an unseen frog or an imperceptible breeze—fractures the moon’s reflection into abstract patterns of light and shadow. The viewer, unaware of what to expect, is compelled to watch the microscopic variations on the water’s surface and the gradual passage of time.

This still sequence also embodies what André Bazin called the “ontological duration of the shot;”55In his seminal essay “The Ontology of the Photographic Image,” André Bazin argues that, unlike painting—or even photography—the cinematic image sustains an ontological relationship with the real world. For Bazin, the long take, by avoiding successive cuts, is uniquely capable of preserving what he calls the “continuity of being.” This continuity encompasses not only physical time, but also the unbroken presence of reality itself—especially evident in unedited shots of everyday life, where no marked dramatic action occurs. See André Bazin, What Is Cinema? Vol. 1, trans. Hugh Gray (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1971), 13–21. but in the digital realm, duration acquires a new significance. The absence of narrative cuts and the presence of pure time render observation itself the subject. Environmental sounds—whether diegetic or reconstructed—blur the referent and construct a sign that no longer requires an original. The viewer, moment by moment, hovers between doubt and belief: have the waves and ducks actually appeared as they seem, or have they been digitally orchestrated?

The dramaturgy of Five is grounded in waiting: the filmmaker ceases to “direct” and steps aside to “let the world perform itself.” Yet this withdrawal is only apparent; it is the act of waiting itself that defines the mise-en-scène, turning real time into performative substance. In this way, the primitive apparatus demonstrates that one can reach hyperreality without elaborate CGI: through the maximal removal of mediation and the subtle engineering of chance, a “minimal” reality is constructed that is as much a simulacrum as the most intricate spectacle.

In the next stage, we will see how Kiarostami extends this drive toward the simulacrum in 24 Frames, pushing the dramaturgy of “post-production animation” to the very limits of reality’s dissolution.

24 Frames: The Dramaturgy of Post-production Animation5624 Frames, dir. ‛Abbās Kiarostami (MK2, 2017), DVD.

In his final cinematic work, ‛Abbās Kiarostami moves beyond live mise-en-scène and steps directly into the realm of post-production. In 24 Frames (2017), there are no actors, no shooting locations, and not even a camera shutter. The entire process unfolds in the editing suite, built upon pre-existing visual material—photographs or paintings. What remains is a “dramaturgy of digital animation”: an effort to generate time and motion within a still image.

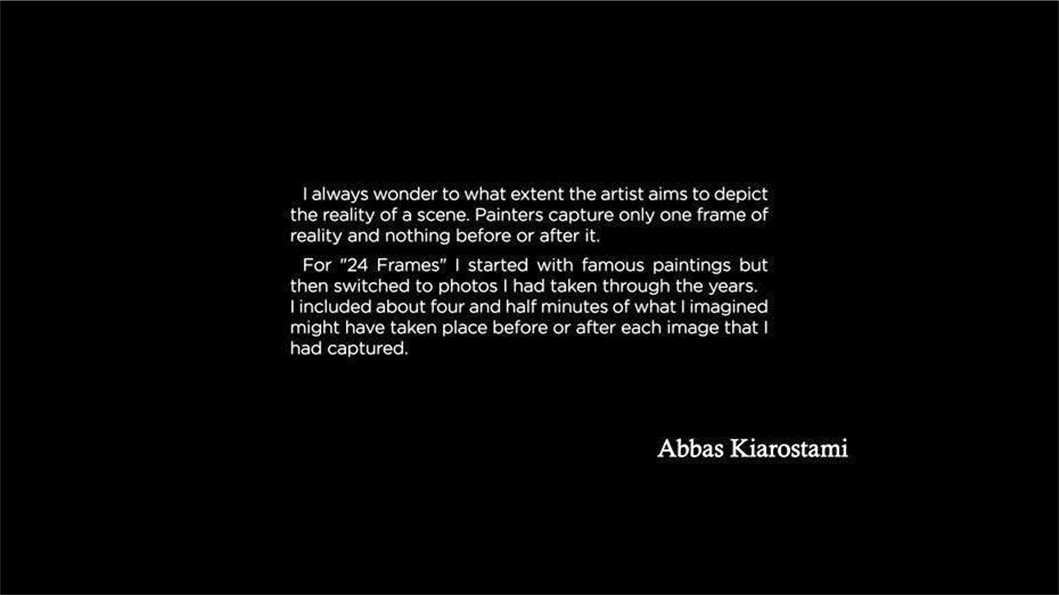

In the film’s opening title, Kiarostami plainly states Painters capture only one frame of reality—what happened before or after. I tried to add something—perhaps what might have occurred before or after the image was taken. This statement signals a shift from classical realism to a form of intelligent simulation: images that never actually happened, yet are engineered so precisely that they feel like a natural extension of reality.

Each of the 24 frames undergoes a complex process of digital animation: layers of the original image are separated in Photoshop; rotoscoping and depth maps are used to construct a simulated three-dimensional horizon. By adding elements like snowflakes or dust particles (via Trapcode Particular), and using ambient sounds recorded with binaural microphones, Kiarostami simulates a world that invites the viewer not to witness a moving photograph, but to experience “a reality in the act of unfolding.”

Figure 9: The opening frame of ‛Abbās Kiarostami’s 24 Frames (2017) displays the director’s own statement. In this reflective note, Kiarostami questions the extent to which an artist can capture reality, emphasizing that painters only depict a single frame and omit what comes before or after. He explains that 24 Frames emerged from his imagination of the moments surrounding still images he had collected over the years.

Within this framework, three dramaturgical types of animation emerge. The first is the extension of a moment—for example, a frame in which a deer stands in the rain, and with the subtle rustling of leaves and artificially generated droplets, time elongates, drawing the viewer into a digital reverie. The second is sudden intrusion—as in a flock of pigeons abruptly bursting into the scene, shattering the stillness with a spectacular explosion of particles and three-channel sound rotation. The third is creation from nothing—frames with no photographic origin at all, such as mist over rocks or waves on a dark sea, where the entire scene is painted digitally: a pure simulacrum with no external referent. A notable instance is Frame 6: a few dark blotches and a white line, blended with a masked sky, directional snowfall, and micro-adjustments to the position of cows on a separate animation layer, are transformed into a blizzard-swept landscape—so seamlessly that only the most careful observer might detect its artificiality. It is precisely here that “the extension of a moment” and the “sense of reality” become indistinguishable.

In 24 Frames, Kiarostami moves beyond the self-reflexivity of his earlier works and enters the realm of apparatus self-exposure:57“Self-exposure” is a step beyond “self-reflexivity”. While self-reflexivity merely reveals the mechanisms of the medium, self-exposure not only makes the cinematic apparatus visible but also turns the incompleteness of any attempt to recover the “original” into the very subject of the drama. The film deliberately exposes the fact that there is no backstage outside the stage—no hidden reality behind the image. the film not only reveals the process of image construction, but deliberately stages a moment in which the viewer becomes aware that even this unveiling is meticulously choreographed. There is no visible camera on screen, yet the traces of masks, pixels, and layered sound—the marks of the digital primitive apparatus—remain embedded in the image’s texture, confronting the spectator with the impossibility of accessing the original. This shift from self-reflexivity to self-exposure suggests that the camera no longer needs to pretend it is absent; the software itself becomes the director, algorithmically timing blinks, gusts of wind and sound pans with a precision no human operator could match—an authorship Lev Manovich calls “automation of vision.”58Lev Manovich, The Language of New Media (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2001), 253. In this sense, Kiarostami’s primitive hyperrealism becomes a lesson in image spectatorship: the image is neither a mirror of reality nor simply a reminder of its constructedness, but instead presents a fluctuating threshold—one in which any effort to locate the “originary referent” is destined to fail. In Baudrillard’s terms, this indeterminate zone—where the image oscillates between reference and invention, rendering the quest for an ‘original’ futile—marks the third stage of the simulacrum.59Jean Baudrillard, Simulacra and Simulation, trans. Sheila Glaser (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1994), 6-7.

Historically, 24 Frames belongs to the tradition of the moving photograph, from Chris Marker’s La Jetée (1962)60La Jetée (1962) by Chris Marker is a seminal experimental short film composed almost entirely of still photographs, often described as a “photo-roman.” It is considered a foundational work in postwar cinematic essay form and a precursor to later digital photo-based moving images. La Jetée, directed by Chris Marker (Argos Films, 1962; streamed on Kanopy, accessed May 2025), For critical analysis, see Janet Harbord, Chris Marker: La Jetée (London: Afterall Books, 2009). to the video art of Bill Viola.61Bill Viola is one of the most influential pioneers of video art, renowned for creating immersive installations that explore slow motion, sensory perception, and metaphysical themes. His works explore duration, stillness, and transformation within the video image. See John G. Hanhardt, ed. Bill Viola: The Passions (Los Angeles: Getty Publications, 2003). Nevertheless, it departs from them in one key respect: Kiarostami takes the Lumière-style static frame and rewrites it through the logic of the pixel. As Gilles Deleuze would describe it, this is a case of the pure time-image—a movement that is not driven by field action, but by the digital continuity within the image itself.

Ultimately, the three-stage trajectory of the primitive apparatus comes full circle: live direction in Ten → observational waiting in Five → software-based animation in 24 Frames. While these approaches differ in their tools and stages of production, they are unified by a common goal: the application of hyperreal dramaturgy to the real world.

24 Frames is Kiarostami’s radical farewell to celluloid, demonstrating how hyperreal dramaturgy culminates in digital animation—the moment when there is no longer even a camera to hide, and yet the primitive apparatus still fabricates a reality that feels more real than everyday life. In this way, the article’s central question—whether reality can still be seized in the digital age—finds its multilayered answer: whether through live direction (Ten), observational patience (Five), or pixel-based post-production (24 Frames), what we are ultimately confronted with is a simulacrum—one that, in Baudrillard’s terms, is “not a reflection of reality, but a self-sufficient replacement for it.”

Drawing together the three case studies above, I use the term primitive hyperrealism to name the point at which a drastically pared-down apparatus produces a third-order simulacrum. Its hallmarks are: (i) engineered accidents that substitute contingency for mise-en-scène, as in the live earpiece prompts of Ten; (ii) long-take duration that allows signs to supersede their referents, exemplified by the six-minute driftwood shot in Five; and (iii) software-driven micro-events that automate vision, visible in the layered animations of 24 Frames—all sustained by the absence of industrial spectacle. In short, this modest camera–software pair achieves the same ontological coup—“being more real than the real”62Jean Baudrillard, Simulacra and Simulation, trans. Sheila Glaser (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1994), 7.—that Hollywood pursues through technological excess.

Conclusion

Drawing this enquiry to a close, I return to the historical lacuna outlined in the introduction: although Kiarostami’s digital turn is frequently praised for its austere minimalism, scholarship has yet to connect that aesthetic to the analytical tradition of apparatus theory. To bridge this gap, I have proposed the concept of a primitive apparatus—a lightweight, mobile dispositif whose handheld camera, two- or three-person crew, natural lighting, and absence of post-production effects create a seemingly modest simulacrum. Set against the opposite pole of the complex apparatus—with its 4K resolution, massive data capture, and photorealistic rendering that engulf the spectator and bury the referent—the primitive apparatus appears simple, yet its dramaturgy remains precisely engineered, choreographing every “random” pause and chance event. By linking this strategy to Baudry’s and Baudrillard’s accounts of spectatorship, I have shown how hyperreal dramaturgy arises not in spite of, but through, the apparatus’s deliberate self-effacement. For Iranian-cinema studies, this reframing positions Kiarostami as a media theorist as well as an auteur; for screen-media theory more broadly, it suggests that the apparatus is not rendered obsolete by digital lightness but reborn in portable form, anticipating current debates on algorithmic vision and machine authorship.

In his late digital works—from Ten to Five to 24 Frames—‛Abbās Kiarostami reveals how this primitive apparatus, despite its humble appearance, can achieve the very same aim that the complex Hollywood apparatus pursues through technological excess: the total appropriation of the real and the substitution of a self-sufficient image in its place.

The analysis of Kiarostami’s three key digital films shows that this appropriation occurs through three distinct dramaturgical strategies. In Ten, the invisible direction of actors via earpiece and the fixation of the camera on the car dashboard creates a sense of immediacy so convincing that the viewer perceives the mother-son conflict as entirely real—though every glance and pause is a live dictation from the director. In Five, the camera becomes a silent observer; long patience for a wave breaking a piece of driftwood or ducks parading across the frame invites the world itself to perform. Yet the recorded reality—through hidden threads or imperceptible edits—is still the result of an engineered accident. In 24 Frames, the camera disappears altogether, and the editing table becomes the site of creation: still photographs are animated with layers of digital effects and binaural sound to transform the captured instant into an extended event—an image that never existed in time yet appears more convincing than reality itself.

Thus, the three Baudrillardian markers—erasure of the referent, self-sufficiency of the sign, and the induction of a sense of reality—are each activated in a different mode: first through live direction, then through patient observation, and finally through post-production animation.

The theoretical value of this trajectory lies in showing that reducing the physical scale of the camera and production crew does not, contrary to expectation, lead to greater transparency in the representation of reality. On the contrary, it renders the process of manipulation more invisible and the simulacrum more effective. Kiarostami’s primitive apparatus, by eliminating technical formalities, does not enhance the “truthfulness” of the image; rather, it introduces a new kind of illusion—one that unfolds not through spectacle, but through silence and simplicity, and is therefore all the more persuasive. If the Hollywood spectacle dazzles the eye with light and motion, Kiarostami’s minimalism mesmerizes the mind with void and stillness. Both, in the end, replace the world with the image. From this perspective, hyperreality is not merely a descriptor for CGI excess, but a quality of any image that succeeds in concealing its referent behind a veil of sensation or ambiguity.

In this light, the boundary between the “expanded reality” of the complex apparatus and the “minimal reality” of the primitive apparatus collapses; both are expressions of the same underlying desire: cinema’s long-standing dream of being more real than the real, a desire already sketched in André Bazin’s claim that film seeks “the total recreation of the world in its own image.”63André Bazin, “The Myth of Total Cinema,” in What Is Cinema? vol. 1, trans. Hugh Gray (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1967), 17.

Building on these findings, the contribution of this article can be articulated on three levels. First, from a media-historical perspective, we showed that the lightweight video camera continues the original impulse of the Lumière brothers’ invention—yet under the shadow of digital technology, the same simple device becomes a tool for producing a referentless simulacrum. Second, in the realm of film theory, we proposed the concept of hyperreal cinematic dramaturgy, in which acts of direction, observation, or post-production—even in their most minimal form—replace traditional narrative and draw the viewer into the process of constructing reality. Third, from the vantage of Iranian cinema studies, we argued that Kiarostami’s late digital films should not be viewed as peripheral to the global digital turn, but rather as a foundational laboratory for exploring contemporary realism—offering even Hollywood blockbusters a crucial insight: that expensive technique is not a prerequisite for simulacral affect; it is enough to arrange the narrative apparatus in such a way that the emotional void left by the absent referent is convincingly filled.