Youth and Precarious Life in Iran (1979-present)

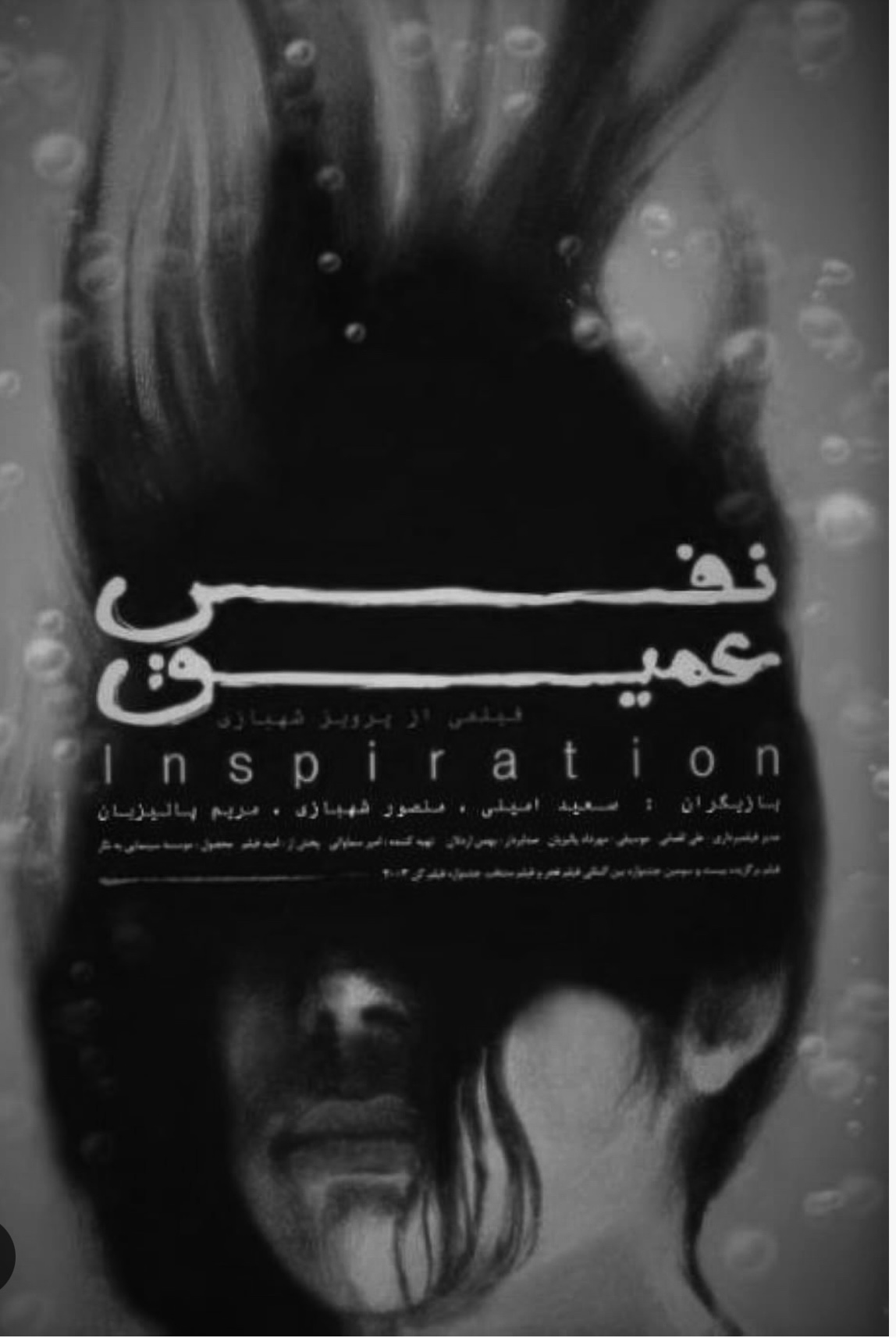

Figure 1: A still from the film Deep Breath (Nafas-i ‛Amīq, 2003) Parvīz Shahbāzī, Accessed via https://www.imvbox.com/en/movies/deep-breath-nafase-amigh (00:03:34)

Introduction

To demonstrate the inadequacy of the popular category “postrevolutionary Iranian cinema,” Blake Atwood introduced the term and genre of “Reform Cinema” to describe the significant shift in the politics of cinema in Iran influenced by the reformist discourse and movement of the 1990s.1Blake Atwood, Reform Cinema in Iran: Film and Political Change in the Islamic Republic (Columbia University Press, 2016), 4. This period, marked by a close relationship between the reformist movement and the film industry, produced films that often addressed social issues such as women’s rights and youth culture. These films reflect the broader reformist agenda of advocating for civil liberties and social justice.2Atwood, Reform Cinema in Iran, 20-21; Hamid Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema. Volume 4, The Globalizing Era, 1984-2010 (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 2012), 367. Despite differences in cinematic style, genre, and themes, these films share a common thread: advocating for hope and sociopolitical change.

However, Reform Cinema itself is not a monolithic category. Initially, it was imbued with a strong belief in the possibility of social and political change, marking a shift from wartime martyrdom discourse to celebrating such diverse yet important elements as the banality of everyday life, women’s agency and public presence, and youth culture. Over time, however, the genre soon began to reflect a growing sense of collective despair and discontentment. While the initial phase of Reform Cinema depicts hope, agency, and resistance, the final phase, coinciding with the last years of Muhammad Khātamī’s second presidential term (1997-2005), reveals the pervasive sense of despair and the elusive nature of hope of this era, particularly among youth and women.

This article traces this trajectory by situating Parvīz Shahbāzī’s Deep Breath (Nafas-i ‛Amīq, 2003) within the context of Reform Cinema. Deep Breath is a noir film following the lives of two young men, Kāmrān and Mansūr, as they drive around Tehran in a nihilistic manner. The film explores themes of disillusionment, social disparity, and the struggles of youth, for Kāmrān and Mansūr in particular but indeed the struggles of all youth in Iran at that time.3By “youth,” I refer to individuals approximately between the ages of eighteen and thirty. In Deep Breath, for instance, Kāmrān, Mansūr, and Āydā are all in their early twenties, Āydā and Kāmrān, specifically, are university students. On the one hand, Kāmrān, a university student, comes from a wealthy family but is emotionally detached and dissatisfied with his privileged life. Mansūr, on the other, comes from a poor background and faces numerous hardships, including an unstable family situation and a lack of financial support. Alongside this main narrative, Āydā, a university student from a middle-class background, also struggles to negotiate the tribulations of this era and shares a romance with Mansūr. As they embark on a journey in a stolen car, the film delves into their internal and external struggles, portraying a stark picture of the last years of the reform period in the early 2000s. Notably, the film’s narrative structure is circular rather than linear, depicting the vicious cycle in which youth are trapped. In what follows, I argue that Deep Breath is a poignant commentary on the transition from the initial euphoria of reform to the eventual, widespread discontentment and growing belief in the futility of reform efforts. I first offer reflections on Reform Cinema as a non-monolithic concept. I then explore youth marginalization, absentee families, and the breakdown of social dialogue in Shahbāzī’s Deep Breath, revealing the pervasive despair and frustration among the youth of this period. By outlining the genre and Shahbāzī’s expert depiction and treatment of this era, this article highlights the pressing need to better understand the causes of youth marginalization and to provide meaningful reforms to address this issue.

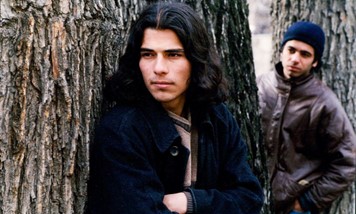

Figure 2: A Still from the film Deep Breath (Nafas-i ‛Amīq, 2003), Parvīz Shahbāzī.

Reflections on Reform Cinema

The reform period in postrevolutionary Iran, marked by the presidency of Muhammad Khātāmī from 1997 to 2005, began with high political hopes and promises. With the subsidence of revolutionary fervor, the end of the prolonged Iran-Iraq War in 1988, and the death of Rūhallāh Khumaynī, the first Supreme Leader of Iran, in 1989, reformist and moderate political elites began to criticize the limits of the revolutionary model of citizenship and its failure as a unifying and inclusive national narrative. Particularly in post-1997, during Khātāmī’s reformist government, political figures emphasized citizenship rights to highlight the inability of citizenship based on pious and revolutionary commitments to establish an inclusive legal and moral system.4Historians like Ervand Abrahamian even call this period Iran’s Thermidorian reaction to the 1979 Revolution. See Ervand Abrahamian, A History of Modern Iran (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008), 183. Reformist discourse stressed citizen rights—particularly those of women and youth—tolerance, democracy, inclusivity, and dialogue among civilizations, garnering widespread support across various demographics. Women’s and youth rights, suppressed by the state’s harsh modesty policy in the decade following the Revolution, were central to the reformist movement. The immediate impact of reformist discourse and policies was a significant increase in social and political participation among youth and women. NGOs focused on youth and women’s issues emerged, and women and youth showcased their public presence and modern way of life in public spaces, such as colleges, shopping malls, parks, and cultural centers.5Asef Bayat, Life as Politics: How Ordinary People Change the Middle East, 2nd edition (Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 2013), 23.

However, it did not take long for these great hopes to turn into profound disappointments. By Khātāmī’s second term, it became evident that many of the reformists’ promises would face significant obstacles within the restrictive political framework of the Islamic Republic, leading to their eventual halt. University students’ movements were suppressed by security police, brutally cracking down on student protests in 1999. Thousands of activists—journalists, teachers, students, women, and members of labor, civil, and cultural organizations—were arrested and faced court charges or dismissed from their positions. Dozens of dailies and weeklies were shut down under the pretext of being the “fifth column of the enemy” or “threatening national security.”6Bayat, Life as Politics, 113. Due to the failure of the reformist government and parliament to uphold their promises and protect citizens’ rights, despair about the possibility of reform grew. The middle class felt betrayed by the stagnation of political reform, while the lower classes suffered from unfulfilled economic promises. This sense of disappointment was especially acute among the youth who had aspired to reclaim their very youthfulness during this era.

These vicissitudes are abundantly reflected in the cinema of the reform period. For instance, Muhsin Makhmalbāf’s Time for Love (Nubat-i Āshiqī, 1991) was a pioneer of Reform Cinema, advocating for carnal love instead of divine love and martyrdom valorized by Sacred Defense Cinema. The film openly depicts a married woman’s affair and explores shifting morality through three episodes with different endings. In the first, Güzel’s affair is discovered by her husband who kills her lover and is then sentenced to death. In the second, her lover kills her husband and is sentenced to death with the roles reversed. Güzel commits suicide in both episodes. In the third, the lover spares the husband who then recognizes their love and arranges their wedding with the judge from the previous episodes as a guest. In addition to advocating for sensual love, the film suggests that morality is circumstantial rather than universal, contrasting with the regime’s restrictive morality policies.7Atwood, Reform Cinema in Iran, 31. What is even more interesting is that Time for Love utilizes mysticism—emphasizing individual experiences of religion, morality, and ethics—to propose an alternative to the government’s stringent morality and modesty policies. The controversy and public debates over the movie alluded to the discourse of reform that would emerge more fully a few years later, marking a pivotal moment in the transition from revolution to reform, both politically and cinematically.8Atwood, Reform Cinema in Iran, 30.

Figure 3: A still from the film Time for Love (Nubat-i Āshiqī, 1991), Muhsin Makhmalbāf.

Equally in sharp contrast to the genre that preceded it, it is ‛Abbās Kīyārustamī’s cinema, specifically Taste of Cherry (Ta‛m-i Gīlās, 1997), that represents the high hopes of this period by celebrating the banality of life. During and after the Iran-Iraq War, postrevolutionary cinema was dominated by Sacred Defense Cinema. In Sacred Defense Cinema, the figures of Basījī (literally meaning self-mobilized) and Shahīd (martyr) were created as new heroes and ideal masculinities, mobilizing support for the war effort. Basījī and Shahīd, who were often humble Iranian men from lower-class backgrounds, sacrificed their lives to protect the country and the Islamic Republic.9Roxanne Varzi, “The Cinema of Iranian Sacred Defense,” in The New Iranian Cinema: Politics, Representation, and Identity, ed. Richard Tapper (New York: I. B. Tauris, 2002), 154-66. These new figures replaced the masculinity of Jāhil and Lūtī (i.e., different terms for “tough guy”) of prerevolutionary Fīlmfārsī cinema while also introducing the ideal Islamic citizens.10Kaveh Bassiri, “Masculinity in Iranian Cinema,” in Global Encyclopedia of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer History, ed. Howard Chiang (Charles Scribner’s Sons, 2019), 1018-1023. For a Basījī, material life was too worthless to preserve his life for; self-sacrifice and martyrdom for transcendental ideals were his ultimate goal.11Pedram Partovi, “Martyrdom and the ‘Good Life’ in the Iranian Cinema of Sacred Defense,” Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa, and the Middle East 28, no. 3 (2008): 513–32.

In contrast, Taste of Cherry, the story of a middle-aged man who wants to commit suicide and the several other people who variously try and eventually succeed to convince him to change his mind, depicts life as a precious gift worth living, even if only for the sake of the sour taste of a cherry or the sweet taste of a mulberry. In addition, the protagonist, Mr. Badī‛ī, is an ordinary man with no lofty ideals or pursuit of heroic deeds. His life is, in fact, filled with doubt rather than certainty, and if he contemplates death, it is out of desperation, not self-sacrifice for societal ideals.

Reform Cinema also specifically emphasized women’s issues in line with the reformist movement advocating for women’s rights. For instance, Rakhshān Banī-i‛timād’s May Lady (Bānū-yi Urdībihisht, 1998) perfectly represents the dominant discourse of this time, and both the director and the protagonist represent this optimism for the possibility of improving women’s rights. Throughout the 1980s, women were almost absent from the cinema, often relegated to off-screen roles as assistants and in minor positions. However, Banī-i‛timād emerged as a prominent director in this male-dominated field12See Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema In May Lady, the protagonist is a woman whose characteristics do not match the ideals that the government has promoted for years. The protagonist, Furūgh, perhaps a reincarnated figure of Furūgh Farrukhzād, who is vailed in colorful māntu (overalls), not in a black chādur that the government promoted as part of its modesty policy, is a professional, educated divorcee, mother, and lover who struggles with a patriarchal system in life and work. This representation symbolizes the reform period, allowing the public presence of women who did not match the ideals of the government’s official ideology. While struggling to balance her traditional assumed role with her modern role, Furūgh is resilient and persistent in asserting her new identity. She pushes against traditional norms by offering a new definition of the ideal woman and mother, symbolizing the possibility of change for women’s civil rights.

Figure 4: The character of Furūgh in May Lady (Bānū-yi Urdībihisht,1998), Rakhshān Banī-i‛timād.

These are not just random examples of a few movies; they represent the trend of the time. Indeed, these films embody various elements of the reform discourse, highlighting political hope for sociopolitical change aimed at improving and empowering “citizens”—a popular term at the time reflecting the dominant discourse of reform. These movies shaped what I call the early phase of Reform Cinema, reflecting a period of high hopes for political reform.

However, during Khātāmī’s second term, as public perception grew that the reform project was at a stalemate, Reform Cinema likewise shifted toward a more pessimistic tone. This shift is evident in several of Banī-i‛timād’s films, where she moves from the optimism of Furūgh in May Lady to the cynicism of Tūbā in Under the Skin of the City (Zīr-i pūst-i shahr, 2001). Set during Khātāmī’s second-term presidential campaign, Under the Skin of the City portrays the harsh realities faced by a family headed by a woman factory worker named Tūbā and is filled with social criticism. Tūbā, the lynchpin of her family, relies on the deed to her house as a source of stability during crises. However, her disabled husband conspires with their oldest son, ‛Abbās, who works for a shady firm and dreams of finding employment in Japan, to sell the house without her knowledge. Meanwhile, Tūbā’s eldest daughter, Hamīdah, suffers abuse from her husband who is frustrated by economic hardships. Her youngest son, ‛Alī, and another daughter, Mahbūbah, are independent-minded teenagers active in the reform movement and their own struggles for individuation.13Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema, 163. The film opens during a parliamentary election, with Tūbā being interviewed and looking into the documentary team’s camera, energetically and optimistically explaining the problems faced by women workers and expressing hope that the candidates will address these issues. The film ends on presidential election day, with Tūbā once again in front of the documentary team’s lens. This time, however, Tūbā appears miserable. Exhausted, heartbroken, and disillusioned at a voting center, she looks into the camera and says, “I have lost my house. My son ran away. People are filming all the time. I wish someone would video what is in here [in my heart]. Who watches these films anyway?”14Under the Skin of the City, directed by Rakhshan Banietemad (2001; Tehran, Iran: Umīd-Fīlm, 2012, IMVBOX), 01:30:02-01:31:02, https://www.imvbox.com/en/movies/under-the-skin-of-the-city-zire-pooste-shahr. All translations are mine unless indicated otherwise.

Figure 5: Tūbā with her son, Under the Skin of the City (Zīr-i pūst-i shahr, 2001), Rakhshān Banī-i‛timād.

The despair, frustration, and disillusionment experienced by Tūbā, her daughters, and her sons, reflecting the political and social conditions of many women, youth, and political and social activists, manifest in various ways and around different themes in the films of this period of Reform Cinema. Examples include Rasūl Sadr-‛Amilī’s I Am Taraneh, 15 (Man Tarānah 15 sāl dāram, 2002), Dāryūsh Mihrjū’ī’s To Stay Alive (Bimānī, 2002), Asghar Farhādī’s Beautiful City (Shahr-i Zībā, 2004), and Parvīz Shahbāzī’s Deep Breath, among many others. Among these films, Deep Breath perfectly represents this period, both cinematically and politically. The movie begins with the discovery of two bodies in a lake, setting a foreboding tone, and follows the lives of Kāmrān, Mansūr, and Āydā caught up in their grim realities, portraying a stark picture of contemporary Iran. Ultimately, Deep Breath culminates in a suspenseful and tragic finale that leaves the audience reflecting on the pervasive sense of despair among the youth.

Youth Marginalization: “Personal Troubles” vs. “Public Issues”

Since the early 1980s, the criminalization of youth culture has become a cornerstone of state policies. The prevailing discourse, particularly in official media, has portrayed youth as troublemakers and reduced their issues to personal problems. Through this discourse, particularly in the post-war period, the representation of young people as “immoral,” “deceitful,” “untrustworthy,” and “irresponsible” has been widely reproduced. Such narratives often adopt psychological, pathological, or criminal lenses, stigmatizing youth behaviors as acts of vandalism, deviance, and delinquency. However, the prevalence of “youth issues,” which will be explored in the context of the movie here, demonstrates that these issues extend beyond personal troubles. As American sociologist C. Wright Mills posits, understanding personal experiences within a broader historical and social framework allows us to uncover profound social meanings and implications behind these experiences.15Wright Mills and Todd Gitlin, The Sociological Imagination, 40th anniversary edition (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000).

In Deep Breath, nearly every character engages in actions that defy societal norms, symbolizing expressions of dissent and a cry for help from marginalized youth. For example, Mansūr breaks the windows of a phone booth when it swallows Kāmrān’s coin. In another scene, a motorcyclist snatches Kāmrān’s cell phone. Kāmrān and Mansūr then steal a cell phone themselves while riding a motorcycle borrowed from a mechanic without the owner’s knowledge, casually breaking the side mirrors of parked cars as they pass by. On a bus, Kāmrān smokes despite objections from the driver and other passengers. Driving a stolen car, they go the wrong way down a one-way street, skip tolls, steal gas, and pilfer a car cover to hide their vehicle. A passerby, pretending to need money for a prescription, pulls out a wad of cash and buys the stolen phone from Kāmrān and Mansūr. To save money on a shabby motel room, identical twins, Ārmīn and Ārash, seeking jobs in Tehran deceive the owner by claiming they are one person.

Figure 6 (top): Mansūr and Kāmrān ride a motorcycle, with Mansūr calmly knocking off the side mirrors of parked cars. Deep Breath (Nafas-i ‛Amīq, 2003), Parvīz Shahbāzī, Accessed via https://www.imvbox.com/en/movies/deep-breath-nafase-amigh (00:07:52)

Figure 6 (bottom): Kāmrān smokes on a bus, seemingly oblivious to the driver and passengers urging him to put out his cigarette. Deep Breath (Nafas-i ‛Amīq, 2003), Parvīz Shahbāzī. Accessed via https://www.imvbox.com/en/movies/deep-breath-nafase-amigh (00:06:12)

The prevalence of these behaviors across various social groups suggests that interpreting them solely through theories of vandalism, social pathology, and criminology is overly simplistic and fails to consider the deeper social causes. This situation underscores the marginalization of youth rather than highlighting youth delinquency and deviance. Kāmrān and Mansūr’s rebellious actions represent the unheard voices of a generation constrained by the political system’s ideological rigidity despite promises of reform. Their behavior reflects the collective despair and frustration of a generation whose presence and way of life were neither heard nor recognized by the government. Instead, as Shahram Khosravi demonstrates, the government and its affiliated media labeled them “without pain” (bī dard), “careless” (bī khīyāl), “without goals” (bī hadaf), “devoid of ideology” (bī ārmān), “without identity” (bī huvīyat), and “without culture” (bī farhang). In contrast, the youth self-identify as “forgotten,” “burnt,” and “fucked up,” feeling they have lost everything.16Shahram Khosravi, Precarious Lives: Waiting and Hope in Iran (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2017), 64, 94. Marginalized and disillusioned, the youth in the film, much like those in Iran of the period, find themselves as the “other,” unheard by both the government and their families, grappling with their identity. Kāmrān, Mansūr, and Āydā’s expressions of dissent should thus be understood as part of a broader issue among the youth—one which eventually spread to other social groups and age brackets. In the political arena, this dissatisfaction and disillusionment among the youth manifested in the short term with the hardline president Mahmūd Ahmadīnizhād’s rise to power in the 2005 election. In the long term, as this sentiment spread to other age groups, it led to a significant decline in voter turnout in recent presidential and parliamentary elections in Iran, which have dropped to unprecedented lows of around 40 percent nationwide and less than 30 percent in Tehran.17“Low Turnout as Conservatives Dominate Iran Parliamentary Election,” Al Jazeera, March 4, 2024, accessed June 23, 2024, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2024/3/4/voter-turnout-hits-new-low-as-conservatives-dominate-irans-parliament

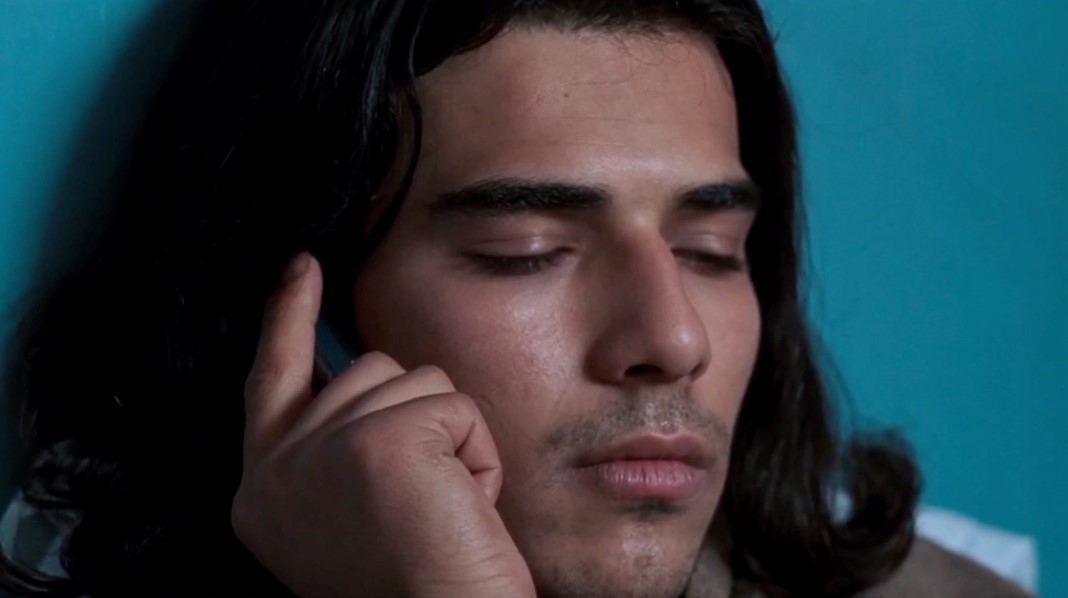

Similarly, Shahbāzī’s depiction of Kāmrān’s depression reflects a broader and quite dire social issue rather than a mere individual problem. After several days of refusing to eat, Kāmrān is hospitalized and falls into a coma, leading to his presumed death. His resistance to eating resembles a hunger strike. Along this heartbreaking journey, he also stops attending college classes. He ignores his mother’s attempts to reach out, including her offer to send him to Europe and purchase him a popular Korean car (a Daewoo), a luxury beyond the reach of ordinary people and even beyond many of the middle class at the time. The reasons for Kāmrān’s departure from home, his refusal to eat, and his rejection of his affluent family’s offerings remain unknown. What is clear is that his depression transcends personal struggles; it is instead a prevalent social issue among his generation.18See Orkideh Behrouzan, Prozak Diaries: Psychiatry and Generational Memory in Iran (Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 2016). Director Shahbāzī underscores this societal perspective on depression through various cinematic techniques and forms. The film portrays Tehran’s bleakness with a grayish filter overlaying the camera lens, capturing scenes during cold, cloudy seasons when trees are bare. Silence pervades much of the movie, with a significant portion featuring no dialogue exchanged. Kāmrān carries a palpable burden throughout, particularly evident in scenes where he and Mansūr aimlessly drive through the city in a moving car, comprising a substantial percentage of the film. In a symbolic scene, Kāmrān’s professor, who attempts to help him, offers him a book from renowned social psychologist Erich Fromm. This act suggests that Shahbāzī views Kāmrān’s problem not as purely individual and psychological, but rather as rooted in a social and political context. The professor’s choice of Fromm’s work implies that systemic factors within the political structure contribute significantly to these psychological challenges. Thus, the remedy must also be social and political, rather than solely psychological.

Figure 7: Kāmrān’s professor recommends a book by Erich Fromm to him. Deep Breath (Nafas-i ‛Amīq, 2003), Parvīz Shahbāzī. Accessed via https://www.imvbox.com/en/movies/deep-breath-nafase-amigh. (00:05:06)

Moreover, the movie’s title, “Deep Breath,” signifies the overwhelming pressure of social issues on the youth, framing suicide as a widespread social problem among them, not merely a psychological one. The opening sequence shows a rescue team retrieving the bodies of a young boy and possibly a girl from Karaj Dam Lake. They have succumbed to the water’s pressure, unable to hold a deep breath, leading to their deaths. This scene transitions into one where Kāmrān, holding his breath underwater in a swimming pool, resurfaces just in time, gasping for air as if escaping drowning. The motif of water and drowning metaphorically represents the various and heavy social pressures faced by the youth, making life suffocating. The entire film extends this moment of Kāmrān holding his breath by depicting the numerous challenges he and his friends face. The only suggested solution within this society seems to be holding their breath as long as possible to survive, a futile strategy for the drowned and drowning youths. Though Kāmrān manages to resurface in the pool, he eventually descends into his coma, presumably dying due to his refusal to eat. As sociologist Emil Durkheim argues, suicide is not merely an individual act of desperation or psychological distress, but a social phenomenon influenced by the structure and organization of society.19See Emile Durkheim, Suicide: A Study in Sociology, ed. George Simpson, trans. John A. Spaulding, Reissue edition (Free Press, 1997). It is not a coincidence that the rate of suicide in Iran increased almost fivefold between 1984 and 2004.20Khosravi, Precarious Lives, 85.

Figure 8: Divers recover the body of a young person from the depths of Karaj Dam Lake. Deep Breath (Nafas-i ‛Amīq, 2003), Parvīz Shahbāzī, Accessed via https://www.imvbox.com/en/movies/deep-breath-nafase-amigh (00:01:35)

Relatedly, the film’s narrative structure is circular rather than linear, depicting the vicious cycle in which the youth are trapped. The film opens with the scene of two young bodies being pulled from Karaj Dam Lake and ends with the same scene, now including Mansūr and Āydā fleeing their families in a stolen car. The final scenes show Mansūr driving recklessly on a narrow, dangerous road by the lake, implying that a collision with a truck has thrown them into the water. The sweater on the first body found matches the one Mansūr is wearing, suggesting that the bodies are theirs. However, this is not the case. In the final scene, without seeing Āydā and Mansūr, we hear their voices asking a passerby about the incident, who replies that two bodies have been found in the water. Although the bodies are not Āydā and Mansūr, they represent other young people from their generation. At the beginning of the film, the first body pulled from the water is wearing a blue sweater with a yellow stripe. Later, Kāmrān is seen wearing the same sweater, which is passed to Mansūr when Kāmrān presumably dies. Later, Mansūr wears the sweater when he arrives at the scene by the lake. The passing of the blue sweater among the youth serves as a generational object, symbolizing the pervasive bleakness faced by and linking their generation together.

Figure 9: Kāmrān sits by Karaj Dam Lake, wearing a blue sweater with a yellow stripe—the same sweater worn by Mansūr and the body found in the lake throughout the film. Deep Breath (Nafas-i ‛Amīq, 2003), Parvīz Shahbāzī, Accessed via https://www.imvbox.com/en/movies/deep-breath-nafase-amigh (00:01:35)

Absentee Family

Deep Breath cleverly uses spatial politics to depict the uncertainty and instability in the lives of youth. Although one of the film’s main themes is family and the relationships between youth and their families, not a single scene is set inside a house. The home, traditionally a private and safe space for rest, confiding in one another, and emotional support, is categorically absent. Instead, everything occurs in public spaces such as parks, restaurants, and city streets. In three scenes, the camera approaches a house but stops at the door or in the yard, the characters and thus the audience never going inside. This spatial representation and restriction suggest the problematic nature of home and family which have lost their assumed function of providing stability and comfort.

In addition, the main characters have all fled domestic spaces for public and temporary ones. Āydā, a university student in Tehran, prefers dormitory life rather than staying with her family—a common practice in Iran until marriage—to experience more freedom. Kāmrān, from a wealthy background with all financial means at his disposal, refuses to return home. Several scenes occur outside Kāmrān’s house, but, again, the camera never goes inside. The twin brothers have left their home in another city and live in a shabby motel in Tehran, hoping to find better opportunities. Mansūr, from a lower socioeconomic background, cannot afford his small, damp basement in a poor neighborhood. As a result, his landlady denies him access to the house and retrieves the keys because of the unpaid rent. Kāmrān and Mansūr sleep in their stolen car or a tacky motel, paying for their stay there with money from their sale of the stolen cell phone.

Figure 10: Kāmrān sits by Karaj Dam Lake, wearing a blue sweater with a yellow stripe—the same sweater worn by Mansūr and the body found in the lake throughout the film. Deep Breath (Nafas-i ‛Amīq, 2003), Parvīz Shahbāzī Accessed via https://www.imvbox.com/en/movies/deep-breath-nafase-amigh (00:19:08)

Thus, these young people’s living arrangements are not characterized by the stability and security typically associated with home but rather by transience and impermanence. While a home is traditionally a place of permanent residence and stability, a car serves primarily as a means of transport for movement from one place to another. Kāmrān and Mansūr spend their days and nights in a stolen vehicle, which, by its nature, lacks permanence and is intended for mobility rather than stability. Kāmrān and Mansūr also spend their nights in a rundown motel located in a bustling commercial area. Unlike a home, a motel is designed for temporary accommodation, catering for travelers passing through from one point to another, staying temporarily to rest before continuing their journey. However, Kāmrān and Mansūr futilely attempt to find permanence in these transient spaces.

Figure 11: Kāmrān and Mansūr in a rundown motel after a long day on the streets. Deep Breath (Nafas-i ‛Amīq, 2003), Parvīz Shahbāzī, Accessed via https://www.imvbox.com/en/movies/deep-breath-nafase-amigh (00:47:08)

In the value system of the Islamic Republic, the traditional patriarchal and heterosexual family is regarded as the most important social unit, often promoted and referred to in official rhetoric as the “warm nucleus of the family.” According to the Iranian Constitution (1979; revised in 1989), the family is “the fundamental unit of society,” and the Islamic Republic of Iran uses kin-related tropes and family, both as a metaphor and a sacred entity, to promote its religious values.21See Rose Wellman, Feeding Iran: Shi‘i Families and the Making of the Islamic Republic (Oakland, California: University of California Press, 2021). However, in Deep Breath, almost all family members are absent, and the family nucleus is cold. The first sign of this is the absence of the father. The father, who is supposed to provide emotional and financial support, discipline, and role modeling for children, is entirely absent from the film, which explains in part Kāmrān and Mansūr’s lack of direction.22For the impact of a father’s absence on the lives of children, see David Blankenhorn, Fatherless America: Confronting Our Most Urgent Social Problem (Harper Perennial, 1996). They don’t know what to do or which way to go, symbolized by the vehicle that the two young men aimlessly drive along winding roads. Situating this personal issue in a larger social context, anthropologists describe it as related to a “fatherless society,” metaphorically referring to the government’s failure in its paternal role.23Mehrdad Arabestani, “The Fatherless Society: Discourse of the Hysteric in Iran,” Psychoanalysis, Culture & Society 24, no. 4 (2019): 520–36. The reformist government failed to provide even the youth’s most basic needs and civil rights and was unable to protect their lifestyle against the suppression of appointed offices such as the judicial system, the police, the paramilitary group of the Basiji, and the vigilante group Hezbollah. Throughout the film, there is only one trace of a father. In a brief dialogue in the dormitory, Āydā’s roommate informs her that her father called and left a message. This is the only instance of a father’s presence, whose voice we don’t hear, commanding Āydā to leave the dormitory and return home because the residence authorities informed him that Āydā is secretly friends with a boy (Mansūr) and often returns late. In collaboration, her biological father and the metaphorical father (i.e., the dormitory officials) deprive Āydā of her basic civil rights.

Figure 12: Āydā, wearing a red hoodie, in Mansūr’s stolen car on a rainy night, Deep Breath (Nafas-i ‛Amīq, 2003), Parvīz Shahbāzī. Accessed via https://www.imvbox.com/en/movies/deep-breath-nafase-amigh (00:29:33)

The mother’s situation is no better than the father’s; she is either powerless or chronically ill. Kāmrān’s mother, in complete desperation, repeatedly tries to contact him via his cell phone but fails. We never see her; we only hear her voice, pleading for Kāmrān to talk to her. In one instance, when Kāmrān calls her and remains silent, she faintly says, “Talk to me, my son. How long are you planning to give us the silent treatment? My son, if you want to leave university, that’s OK. You want to move out and live on your own? Fine, do that. Live separately. Do you want us to send you abroad? We’ve always told you….”24Deep Breath, directed by Parviz Shahbazi (2003; Tehran, Iran: Bih-Nigār, 2012, IMVBOX), 00:16:28-00:16:53, https://www.imvbox.com/en/movies/deep-breath-nafase-amigh. The mother’s faint, barely audible voice suggests that her efforts to bring Kāmrān home are doomed to fail. Before she can finish her sentence, the cell phone’s battery dies, symbolically indicating the failure of their communication and connection. Throughout the film, no dialogue forms between them, and even when a message gets through, it has no impact on Kāmrān.

Figure 13: Mansūr listens to one of the many messages from his mother on his mobile phone, pleading with him to come home. Deep Breath (Nafas-i ‛Amīq, 2003), Parvīz Shahbāzī, Accessed via https://www.imvbox.com/en/movies/deep-breath-nafase-amigh (00:17:32)

Mansūr’s mother is also absent, but in his case it is due to illness. In the only scene where we see her, she and Mansūr are sitting on a bench in the yard of a psychiatric hospital. The mother, silent and staring blankly, is revealed to be suffering from a severe mental illness. Unlike Kāmrān’s relationship with his mother, here it is Mansūr who tries to communicate, but his mother is unable to respond. In contemporary Iranian nationalism, Iran is represented as the “motherland” (mādar-i/mām-i vatan), and the image of a dying mother in need of immediate care frequently appears in the press to symbolize the country’s ailing condition.25See Mohamad Tavakoli-Targhi, Refashioning Iran: Orientalism, Occidentalism, and Historiography (Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2001). Thus, Mansūr’s sick mother quite easily can be seen to metaphorically represent a sick Iran in need of care and protection. In another scene, when Mansūr and his sister discuss their mother’s situation, Mansūr says, “I want to bring mom home,” to which his sister responds despairingly, “Why? Do you plan to bring her home, leave her in a corner, and then continue with your aimless wanderings?”26Deep Breath, 00:26:07-00:26:13. Overall, the portrayal of fathers and mothers in the film suggests that, whether using the masculine metaphor of the provider state or the feminine metaphor of the homeland, neither the state nor the homeland is in good condition, and neither are its children.

What is more, regardless of their social or economic backgrounds, all three characters experience despair and detachment from their homes that transcend social classes. Kāmrān comes from an upper-class, wealthy family living in a large villa in northern Tehran, enjoying the economic privileges of affluent youth. His mother purchases an expensive car for him and offers to provide him with a separate house if he desires. She even suggests sending him abroad if he wishes to drop out of college. However, Kāmrān rejects all these privileges. He refuses the car his mother bought for him and scratches its entire body with a piece of metal to damage it. He pays no attention and remains indifferent to any of his mother’s offerings. Economic and class privilege is unable to resolve his problem. In contrast, Mansūr hails from a lower-class family. His father is absent, and his mother suffers from mental illness, leaving them impoverished in a small, damp basement in a disadvantaged neighborhood of Tehran. Unable to afford rent, Mansūr becomes homeless, wandering the streets without a university degree or stable employment. Between the two young men, Āydā represents the middle class, characterized by her cultural capital and social skills. Despite her advantages, she chooses to stay in a dormitory rather than at home, reflecting a similar sense of abandonment.

Figure 14: Kāmrān scratches the car his parents bought for him with a metal key. Deep Breath (Nafas-i ‛Amīq, 2003), Parvīz Shahbāzī, Accessed via https://www.imvbox.com/en/movies/deep-breath-nafase-amigh (00:19:53)

The Breakdown of Social Dialogue

Dialogue, tolerance, democracy, and even the dialogue between civilizations were among the key components of the reformist discourse. However, factional conflicts between reformists and conservatives, and between elected and appointed offices, escalated to such an extent that Khātāmī lamented his radical rivals in the military, intelligence, and security institutions, which were under the Supreme Leader’s supervision, creating crises for Khātāmī’s government every nine days. This failure to foster dialogue between political factions and to acknowledge one another even led to the notorious chain murders by the government of scores of dissident intellectuals.27On the chain murders, see Muhammad Sahimi, “The Chain Murders: Killing Dissidents and Intellectuals, 1988-1998,” PBS Frontline, January 5, 2011. Accessed October 11, 2024, https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/tehranbureau/2011/01/the-chain-murders-killing-dissidents-and-intellectuals-1988-1998.html A dozen reformist newspapers and magazines were shut down. The dormitory of Tehran University students, who had gathered to protest the closure of the reformist newspaper Sālām, was ransacked by the police, Basījīs, and the Hizballāh vigilante group. Many political and student activists were arrested and imprisoned.

The film thus reflects the breakdown of dialogue at the macro level of the political system in the microcosm of daily life. As already mentioned, silence shapes a significant portion of the film, highlighting the inability or reluctance of characters to engage in meaningful conversation. When dialogue does occur, it tends to be brief and cryptic, with individuals struggling to express their thoughts and emotions. It is as if verbal suppression has taken hold, stifling genuine communication. Āydā stands out as an exception, openly sharing her views and feelings, but she faces consequences for this, such as expulsion from the dormitory. Mansūr, on the other hand, falters in connecting with others. Despite Āydā’s encouragement to talk about himself, his interests, and his life, he repeatedly responds, “I don’t know what to say.”28Deep Breath, 00:30:58-00:30:59. Similarly, Kāmrān remains mostly silent, burdened by deep sorrow. When prompted by Mansūr to speak, Kāmrān offers minimal responses, contributing to their strained relationship. As with his mother, attempts at communication with Kāmrān by people other than Mansūr often fail completely; he disregards pleas not to smoke on the bus, appearing disconnected from those around him. Further, instances of clear communication in the film often reveal misunderstandings or deceit rather than fostering genuine connections. For instance, a man posing as a needy beggar can suddenly afford to buy Kāmrān and Mansūr’s stolen phone at a low price, intending to resell it himself for profit. Another individual, seeking a cheaper call to Japan, uses Mansūr’s stolen phone under false pretenses.

Even communication tools like cell phones or public telephones, designed to foster connection, fail in their intended purpose. Kāmrān’s attempt to use a public phone is thwarted when it devours his coin without connecting him. Throughout the film, cell phones are either stolen, suffer from signal issues that hinder communication, or run out of credit at crucial moments. When Kāmrān’s phone is stolen, and, in return, he steals another person’s phone, he says: “You see, Mansūr. The good thing about this phone is that my relatives can’t call me anymore.”29Deep Breath, 00:09:10-00:09:13. These instances of malfunctioning technology symbolize broader societal challenges: the difficulty in establishing meaningful dialogue among individuals, the failure to listen to differing voices and opinions, and the struggle to recognize diverse perspectives.

Figure 15: Two motorcyclists steal Kāmrān’s phone, interrupting his conversation with his mother. Deep Breath (Nafas-i ‛Amīq, 2003), Parvīz Shahbāzī, Accessed via https://www.imvbox.com/en/movies/deep-breath-nafase-amigh. (00:05:26)

Figure 16: Mansūr breaks the glass of the public phone kiosk after it devours Kāmrān’s coin. Deep Breath (Nafas-i ‛Amīq, 2003), Parvīz Shahbāzī, Accessed via https://www.imvbox.com/en/movies/deep-breath-nafase-amigh (00:06:53)

Conclusion

Parvīz Shahbāzī’s Deep Breath serves as a profound commentary on the pervasive sense of despair and marginalization among Iranian youth during the early 2000s. Through its circular narrative structure and the portrayal of Kāmrān and Mansūr’s aimless journey, the film encapsulates the broader social and political disillusionment that characterized the end of the reformist era in Iran. The characters’ actions, which defy societal norms, reflect their desperate attempts to assert their presence in a society that has largely ignored their struggles and aspirations.

Further, the film’s depiction of Tehran’s bleak urban landscape, coupled with the recurring motif of water and drowning, metaphorically represents the suffocating pressures faced by the youth. The symbolic passing of the blue sweater among the characters also underscores the generational continuity of this despair. Moreover, the absence of stable familial structures in the film highlights the breakdown of traditional support systems, leaving the youth to navigate their challenges in transient and precarious spaces.

Ultimately, Deep Breath not only illustrates the personal struggles of its characters but also critiques the systemic failures that contributed to the widespread sense of hopelessness of the early 2000s. By situating individual experiences within a broader social and political context, Shahbāzī’s film calls for a deeper understanding of the underlying causes of youth marginalization and the urgent need for meaningful reforms to address these issues.

Cite this article

Abstract: This article examines youth marginalization, absentee families, and the breakdown of social dialogue in Parvīz Shahbāzī’s film Deep Breath (Nafas-i ‛Amīq, 2003). The film serves as a poignant representation of the transition from the initial euphoria of Iran’s “reform era” to the eventual widespread discontent and growing belief in the futility of such reform efforts. The reform period in postrevolutionary Iran, marked by the presidency of Muhammad Khātamī (1997-2005), commenced with high hopes and swiftly descended into disappointment. Khātāmī’s campaign slogans emphasized citizen rights, particularly those of women and youth, tolerance, democracy, inclusivity, and dialogue among civilizations, garnering widespread support across various demographics. However, by the middle of his second term, optimism had turned to disillusionment: the middle class felt betrayed by the stagnation of political reform while the lower classes suffered from unfulfilled economic promises. This sense of disillusionment was especially acute among the youth who had aspired to reclaim their youthfulness during this era. By situating Deep Breath within the context of Reform Cinema—a genre both influenced by and reflective of the reformist discourse—this article traces this trajectory. Initially, Reform Cinema was imbued with a strong belief in the possibility of socio-political change, marking a shift from wartime martyrdom discourse to celebrating the banality of everyday life, women’s public presence, and youth culture. However, it soon began to reflect everyday citizens’ growing collective despair and discontentment, exemplified by Deep Breath, especially represented in the precarious lives of youth from diverse social classes and backgrounds.

Key Words: Reform Cinema; youth culture; youth marginalization; social discontent; generational despair; postrevolutionary Iran