Self-Reflexivity in Iranian New Wave Cinema

Introduction

In Khirs nīst (translated into English as No Bear [2022]), the acclaimed filmmaker Ja‛far Panāhī, banned from making films stands in a somber mood on the Iranian side of the border separating the country from its western neighbor, Turkey, contemplating the advantages and disadvantages of departure, illegally and in the night.1Ja‛far Panāhī, dir. No Bear (Iran, 2021). A court verdict in 2010, in the wake of the Green Movement, had banned the director from making movies and leaving the country for film festivals, where he had been frequently invited not only as a director but as a jury member as well. In No Bear, like his other post-ban films, Panāhī appears in front of the camera publicly showing his ordeal, revealing his trials and tribulations, and at the same time struggling with the decision to either leave a country where his engagement in what he loves and his source of income is forbidden to him, or to stay and bear the brunt of his verdict. Ironically, at the time of his film screenings in festivals in 2023, Panāhī was incarcerated at the notorious Evin prison. Thus, the question of leaving the country, for him, was not only a philosophical dilemma but also one imbued with personal and political significance. No Bear served as a remarkable example of a self-reflexive film in which the director, the production crew, and the filmmaking process itself became the subject matter of the film.

This article examines the self-reflexive technique in the works of ‛Abbās Kīyārustamī, Muhsin Makhmalbāf, and Ja‛far Panāhī, and questions how the employment of this technique aids the filmmakers to create a movie with multiple layers of meaning, in a political sense. Self-reflexive technique here refers to occasions where directors demonstrate on camera the film making apparatus, and/or themselves, as a subject of the filmic enterprise. We see this technique repeatedly appearing in the experimental cinema of Iranian film directors such as ‛Abbās Kīyārustamī, Muhsin Makhmalbāf, Ja‛far Panāhī, as well as Bahrām Bayzā’ī, Rakhshān Banī-i‛timād, Tahmīnah Mīlānī, and Dāryūsh Mihrjū’ī. By analyzing the works of Kīyārustamī, in this article, we see how the self-reflexive characteristics of Close-Up, for instance, allow the director to become a sympathetic interlocutor throughout the film, seeing things differently from the judicial and political lens, and finding creative and idiosyncratic ways to solve societal problems. Likewise, Makhmalbāf’s self-reflexive forays in the autobiographical film Nūn u Guldūn (A Moment of Innocence, 1996), show the necessity of re-visiting the political past through personal memory, and providing a revisionist reading of it. Makhmalbāf’s early movies grapple with the idea of the role of film in re-defining the past, offering a revisionist reading of history. The last section of this article examines the works of Ja‛far Panāhī in the period when he was banned from filmmaking, and how his metacinematic attempts re-define the meaning and role of cinema, which has become a powerful medium to tell astounding stories with social and political significance.

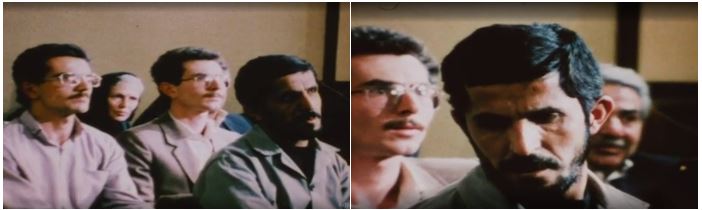

Figure 1: from left: ‛Abbās Kiyārustamī, Muhsin Makhmalbāf, and Ja‛far Panāhī,

Siska defines reflexivity in “Metacinema: A Modern Necessity,” as a “consciousness turning back on itself.” This reflexivity appears in aesthetic media in two varied ways: “1) in the artist reflecting upon his medium of expression; and 2) in the artist as a creator reflecting upon himself, meaning that reflexivity is manifested in films on movie making, or on the movie-maker, or both.”2William C. Siska, “Metacinema: A Modern Necessity,” Literature/Film Quarterly 7, no. 4 (1979): 285–89, 286. Self-reflexivity in Iranian cinema generally disrupts narratives, transcends set boundaries, and functions in a subversive manner. In a metacinematic representation, the aesthetic representation takes a foray into the cultural, social and political realms, and the viewer is pushed to think differently, rather, more critically about the subject matter. Therefore, the use of metacinema is generally accompanied with a “narrative intransitivity,” referring to a break in the linear progression of film. While disrupting the linear progression, this narrative intransitivity makes room for a more critical and nuanced interpretation of the film, transcending the superfluous.

Siska believes that “instances of narrative intransitivity seldom occur in traditional cinema, though they are by far the most commonly used reflexive techniques in modernist films.” He further defines narrative intransitivity by explaining that “Narrative is rendered intransitive when the chain of causation that motivates the action and moves the plot is interrupted or confused, through spatial and temporal fragmentation or the introduction of alien forms and information.”3Siska, “Metacinema: A Modern Necessity.” 285–89, 286. Resnais’s films, and later Buñuel films seek to mystify in this fashion. Godard and Makavejev have made the interpolation of literary texts, skits, speeches, and printed slogans such an integral part of their style that we now regard it as conventional. In their work, reflexive techniques cause the films to “lose their transparency and become themselves the object of the spectator’s attention.”4Lúcia Nagib, “2. Jafar Panahi’s Forbidden Tetralogy: This Is Not a Film, Closed Curtain, Taxi Tehran, Three Faces,” In Realist Cinema as World Cinema: Non-Cinema, Intermedial Passages, Total Cinema, (Amsterdam University Press, 2020) 63-86, 66. In the films of multiple Iranian filmmakers, we encounter instances of narrative intransitivity as an integral part of their style, where reflexive techniques cause the film to themselves become the object of the spectator’s attention.

Self-reflexivity, as well as the Verfremdung/Entfremdung (alienation) techniques initially introduced by Bertolt Brecht in theater, have turned film into an aesthetically different “political” project. During his “militant period,” Jean Luc Godard embarked on making self-reflexive movies where he could show the means of production through the course of the film, and he announced that he did not just want to make “political films,” but to make them “politically,” for the sole purpose of “politicizing the viewers.”5Ewa Mazierska, “Introduction: Marking Political Cinema.” Framework: The Journal of Cinema and Media 55, no. 1 (2014): 35-44. Godard had followed in the footsteps of others including Bertolt Brecht, who had theorized the technique of Verfremdung/Entfremdung, an act of alienation, wherein the actor came out of the performance in the midst of production and thus made the viewers feel closer to the performance, a sort of self-reflexive technique.6See Kent Carroll, “Film and Revolution: Interview with the Dziga-Vertov Group,” in Focus on Godard, ed. R. S. Brown (Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall, 1972), 50–64. The literature on Godard’s political cinema is huge. For Godard’s original views see also Jean Luc Godard, “Towards a Political Cinema,” in Godard on Godard, ed. Tom Milne (New York: Da Capo Press, 1972). For a concise discussion, see Julia Lesage, “Godard and Gorin’s left politics, 1967–1972,” Jump Cut, no. 28 (April 1983): 51–58. Brecht’s alienation effects aimed “to disrupt narrative illusionism” and brought the reality of the medium and its corresponding ideology to the audience’s awareness.7Nagib, “2. Jafar Panahi’s Forbidden Tetralogy,” 63-86.

Impersonating a Filmmaker: Kīyārustamī’s Close-Up

Close-Up (Nimā-yi nazdīk, 1990), directed by ‛Abbās Kīyārustamī, is considered today to be one of the most widely acclaimed movies in world cinema in terms of both form and content. Close-Up chronicles the true story of an individual who impersonated the renowned filmmaker Muhsin Makhmalbāf, when the family’s mother mistook him for the director on a public bus.8‛Abbās Kīyārustamī, dir. Close-up (Iran, 1990). She introduced the fake filmmaker to her family, a husband and two sons, and they wholeheartedly embraced the spurious claims of this imposter filmmaker, in a state of gullibility. Subsequently, the family unearths the true nature of the fake filmmaker, Husayn Sabzīyān. They promptly summon the authorities seeking his arrest and a journalist accompanies the police during the apprehension. This event is then chronicled in the daily newspaper.

Upon reading the news in the newspaper, Kīyārustamī considered this incident to be a remarkable subject matter to document, and he pursued the matter by visiting with the impersonator in police detention. Subsequently, in Close-Up, he recreated the story, embedded his actual questioning of the perpetrator in the documentary film, and filmed the actual trial as it happened. In the course of the trial, the turbaned judge, who did not see the added value of this legal case compared to others, reluctantly starts asking Sabzīyān to explain his motives for introducing himself as the filmmaker Makhmalbāf. His line of questioning focuses mainly on determining whether he can find Sabzīyān culpable by questioning his “intent,” which would legally make him responsible.

But the director, Kīyārustamī, is not satisfied with the line of legal questioning, and he starts his own line of questioning to uncover the psychological and social motives of this individual’s actions. In an unusual turn of events, the trial judge allowed the film director to probe the defendant in the court. The socio-psychological questions Kīyārustamī poses differ from the legal ones in that they try to get deeper into the inherent roots of the seemingly criminal act. The director’s embeddedness in the court case allows matters to come into light, such as Sabzīyān’s state of being, his poverty level, his veteran status, as well as his working-class milieu, that otherwise would not have been revealed. It also opens up issues fundamental for the viewer’s understanding of the character of the defendant and his motives, shedding light on the context of the society in which he lives. Kīyārustamī’s line of questioning reveals more than the obvious, as he had hoped, and at the same time opens the line of scrutiny to go beyond the defendant himself, implicitly critiquing the political conditions in post-revolutionary Iran.

Figures 2-3: Sabzīyān is in court alongside the plaintiff’s family. Close-Up (Nimā-yi nazdīk, 1990), ‛Abbās Kīyārustamī, accessed via https://www.aparat.com/v/j53425n (00:31:56-00:38:26)

Before the trial scene, however, Kīyārustamī had shown his presence, and the contour of his face, as an involved filmmaker in a brief meeting with Sabzīyān in jail. By seeing and hearing Kīyārustamī, the director broke from the linear narrative that the documentary was trying to create. In an intriguing dalliance with the camera, Kīyārustamī showed himself, inserted his voice, and alerted the spectator about the significance of Sabzīyān’s case for understanding the society in contemporary Iran. When in the trial scene, Kīyārustamī disrupts the court session—and his own documentary narrative—by questioning the defendant as if he were the judge. The director seeks to shed light on Sabzīyān as a person, delving into his background and historical context, seeking to understand his human needs, and eventually his intentions. While the legal interrogation concentrated on finding out intent (mal-intent or not), the director’s questioning concentrated on understanding the defendant’s subjectivity.

By interjecting himself in the trial, Kīyārustamī turns himself into a sympathetic interlocutor, one who elucidates social malaise with his camera. The director is more interested in Sabzīyān’s mental state, seeking to know what went on in his mind that made him impersonate a filmmaker, and why he wanted to create such a rapport with this middle-class family. As a sympathetic interlocutor, he is not there to judge, but to observe, document, and report—and maybe more. The metacinematic characteristic of these scenes revolves around designating a role for the filmic enterprise in solving social malaise, through empathy rather than discipline.

Why is the working-class Sabzīyān impersonating a filmmaker? What significance does this hold for the cinematic enterprise with which he wants to connect himself? What does Kīyārustamī’s questioning show us about the role of film in a post-war society?

In the trial, Kīyārustamī asks pointed questions to show his in-depth interest not necessarily in the legal matters of the case, but rather in the way this case sheds light on how the culprit’s acts are interlaced with issues related to unemployment, social malaise, and the post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) of war veterans. In his thorough questioning, Kīyārustamī repeatedly pushes Sabzīyān to bluntly reveal and explain to the viewer, as well as to his court attendees, any links between his perceived crime and the post-revolutionary circumstances that led to it. Is this hence a commentary on life in post-war Iran? And how is Close-Up a tribute to the power of film in underscoring major social ills?

After getting the answers that Kīyārustamī pursues, can the viewer still blame Sabzīyān solely for what transpired? Is he the culprit, or rather the victim of the culmination of years of mistaken social policies and decision making? At one point, Sabzīyān identifies himself with the protagonist, Hājī, of Makhmalbāf’s ‛Arūsī-i Khūbān (Marriage of the Blessed, 1989), who was a PTSD survivor of the eight-year war between Iran and Iraq.9Muhsin Makhmalbāf, dir. ‘Arūsi-i Khūbān (Iran, 1989). Could the affinity Sabzīyān felt with the character of Hājī, whose physical resemblance is also striking, suggest that Sabzīyān suffered from PTSD as well? Has he also returned from the “sacred war,” the Iran-Iraq war of 1980-1988, only to be left alone to his own devices, without any assistance from outside, perishing in impoverishment, suffering from trauma? Could such a striking social and political commentary be gleaned from this documentary had Kīyārustamī not embedded himself as an interrogator in the trial scene? The director asks his unusual questions precisely to get to a point where it reveals and divulges the deeper reasons behind the alleged criminal act.

As mentioned above, in the court, the judge needs to establish criminal intent to successfully move forward with the case. However, for Kīyārustamī, criminal intent is not of interest, rather, of interest are the actual reasons behind the criminal act. As Matthew Abbott states in Abbas Kiarostami and Film-Philosophy, Kīyārustamī’s interjection, “is a call to present-ness; it demands you wake up and pay attention.”10Mathew Abbott, Abbas Kiarostami and Film-Philosophy (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2016), 812. It is indeed Kīyārustamī’s way to make the spectator look at what is going on, particularly to pay attention to social malaise in post-war Iran, but also to pay attention to the role of film and the apparatus of filmmaking.

In Close-Up, ingenious self-reflexivity disrupts the traditional narrative in many ways as it disrupts the form as well as content of the film. With his inquiry, Kīyārustamī unabashedly goes further to delve into the intent of the defendant. The line of questioning that Kīyārustamī adopts divulges a whole array of new information that would have otherwise remained unknown to the court. In this case, the new information helps to establish our understanding and sympathy for the accused not as a common criminal but rather as an unfortunate victim of circumstances: a victim of war, trauma, unemployment, and family and marital conflicts.

Figure 4: Sabzīyān, accompanied by Muhsin Makhmalbāf, is on the way to the plaintiff’s family home. Close-Up (Nimā-yi nazdīk, 1990), ‛Abbās Kīyārustamī, accessed via https://www.aparat.com/v/j53425n (01:34:04)

In this film, the filmmaker’s role is more than a sympathetic interlocutor. The filmmaker becomes not only one who listens neither to judge nor be judgmental, but also one who seeks to pay attention to root causes. Kīyārustamī’s self-reflexivity plays a great role in highlighting what he could not otherwise have told had he not pursued that line of questioning. He disrupted the court and disrupted the spectator’s notion of how this trial would go, and he also disrupted the traditional role film plays in order to create an intimacy between the subject and the spectator. In other words, narrative intransitivity allowed him to establish a close connection with the spectator, and at the same time to express his social and political commentary.

The director’s final statement on the role of film occurs predominantly in the last scene when Makhmalbāf meets Sabzīyān in front of the detention center, an encounter that has an element of surprise, both for the spectator and Sabzīyān himself. In this encounter between the real Makhmalbāf and the fake one, the spectator becomes aware of the filmic process when the audio is suddenly cut off and we hear Kīyārustamī telling his crew about the age of their filming equipment. Ironically, the long shot of the encounter turns into a closeup on the challenges of filmmaking in Iran, juxtaposed with the closeups of earlier footage. In turn, this becomes a critique of the equipment used since the seventies, before the Revolution, highlighting how the film industry was struggling to make films. Many have asked why Kīyārustamī actually includes this sequence in his finished film. How does this add to the film? No doubt, by bringing up the issue of the equipment at a crucial stage of the film, the role of film and filmmakers present a jab at the social situation that has left them—the filmmaker, Sabzīyān, and the entire filmic enterprise—in such dire straits. Therefore, while the film is not “political” per se, in a Godardian sense, it was made “politically” to question and reflect upon contemporary circumstances.

Close-Up was an experimentation with forms for Kīyārustamī, and in his other films he continues to do other experiments. For instance, in Ta‛m-i Gīlās (The Taste of Cherry, 1997),11‛Abbās Kīyārustamī, dir. Ta’m-i Gīlās (Iran, 1997). we see a digital sequence of the director filming the crew at the very end of the film. In an earlier movie, Zīr-i Dirakht-i Zaytūn (Through the Olive Trees, 1994),12‛Abbās Kīyārustamī, dir. Zīr-i Dirakht-i Zaytūn (Iran, 1994). while we do not see Kīyārustamī himself, we see an actor playing a film director engaged in the prolonged process of filmmaking. In all these films, Kīyārustamī, wittingly or unwittingly, provides a space that disrupts linearity and increases the intransitivity.

Figure 5: A digital sequence of the director filming the crew at the very end of the film. Ta‛m-i Gīlās (The Taste of Cherry, 1997), ‛Abbās Kīyārustamī, accessed via https://www.aparat.com/v/k62t9u0 (01:32:21)

Experimenting with Time and Memory: Makhmalbāf’s A Moment of Innocence

Like Kīyārustamī, Muhsin Makhmalbāf’s experimental style uses self-reflexive techniques in remarkable ways throughout his oeuvre. In the autobiographical documentary, A Moment of Innocence (1996), he repeatedly disrupts the narrative, showing the cinematic enterprise throughout this movie as it re-tells a significant historical incident that upturned his life and the lives of all around him.13Muhsin Makhmalbāf, dir. A Moment of Innocence (Iran, 1996). As an ideologically motivated 17-year-old, Makhmalbāf stabbed a police officer to steal his gun and engage in militant activism against the Shah in pre-revolutionary Iran. However, his plan did not pan out as he had envisioned, and he was arrested, tortured, and held in the notorious Evin prison. It was because of the 1979 Revolution that Makhmalbāf was released from Evin and was able to join the ranks of revolutionaries.

In the early nineties, Makhmalbāf set out to re-cast this major event in his life, giving each of those involved a separate camera to film their own account: one camera for the stabbed police officer; one camera for the young actor playing the police officer; one camera for the director himself; and one camera for the actor playing the younger Makhmalbāf. Interestingly, each account turns out to be considerably different from the others.

In order to find the right cast for his experimental movie, Makhmalbāf held casting auditions for actors to play his younger self as a militant revolutionary. At the same time, he held a parallel audition for the policeman he had stabbed twenty years earlier. The entire movie is seemingly about Makhmalbāf, the director, and how he interjects himself in the process of filmmaking in one way or another. At the same time the narrative repeatedly breaks the rules by juxtaposing multiple points of view. Here, Makhmalbāf’s narrative is interrupted, a narrative intransitivity that according to Siska happens when the chain of causation motivating the action in film is either interrupted or confused “through spatial and temporal fragmentation.”14Siska. “Metacinema: A Modern Necessity.” 285–89, 286. In terms of form, therefore, Makhmalbāf parts with traditional linear filming, and transforms filmmaking into a series of narrative intransitivities.

What is even more astounding is Makhmalbāf’s insistence on giving a voice to the downtrodden by providing the means of filmmaking to his former opponent, an enemy whose life was truly upturned due to the young Makhmalbāf’s ideological militancy. The stabbed policeman, now in his forties, lost the livelihood he had imagined in his youth as a result of the young Makhmalbāf’s ideologically motivated folly. In the beginning of the film, the police officer—the actual officer himself—had come looking for the celebrity Makhmalbāf, with the hope that he could get an acting position from him in recompense for what he had done twenty years earlier. A few sequences later, we see that Makhmalbāf has offered a camera to the policeman and has allowed him to choose the young actor who will play him in the upcoming film. However, he does not entirely give him carte blanche. When the policeman selects a young modern youth with starkly different physical appearances, Makhmalbāf, unsatisfied with the former policeman’s choice, changes the young actor without the policeman’s approval. This unwelcome interjection by the director not only disrupts the narrative but upsets the former policeman and causes him to leave the scene.

Figure 6: A police officer is standing next to a young actor who has been chosen to play a young version of him. Nūn-u guldūn (A Moment of Innocence, 1996), Muhsin Makhmalbāf, accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kmlH673_jnM (00:12:34)

In an attempt to solve this sudden turn of events, once again we hear the director, Makhmalbāf, instructing his cameraman, Zaynāl, to fetch the former policeman. Zaynāl walks down a snowy, white alley way, shown in a long take. While the director initially intended to give free reign to the policeman he once wronged, he soon realized that they have differing assumptions and different versions of how this history should be reconstructed. The director, Makhmalbāf, enforces his ways as much as he can, but at some point he himself realizes that his version and his ways may not be the only correct way to remember the past. As a result, the outcome is fascinating in that Makhmalbāf and the policeman offer different versions of what really transpired.

We know that the historical moment at the center of A Moment of Innocence is considered a turning point in the lives of both the director and the stabbed policeman, a dramatic and traumatic exit from the age of innocence for both individuals. But how should this past be narrated, and from whose perspective? By recounting history in this way, we understand that the director does not wish for this autobiography to be re-told unilaterally or dogmatically, but rather that it is essential to be generous about including the perspective of the other sides, which means he intends to include the perspective of the policeman and that of his female cousin, who appeared as an accomplice in the stabbing ordeal. By shedding light on the narrative of opposing parties, however, the dissonance of these narratives becomes more pronounced. In other words, Makhmalbāf employs the self-reflexive technique not to extoll his past political engagement and ideological beliefs, or merely show them as they were. Rather, he disrupts the unilateral narrative to create a new multi-faceted narrative about the past. At the same time, he is offering a new reading of history—which is a political endeavor per se, but without making an explicit political statement.

Figure 7: A reconstructed scene from Makhmalbāf’s past, where he and his cousin are discussing their plan about the police officer. Nūn-u guldūn (A Moment of Innocence, 1996), Muhsin Makhmalbāf, accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kmlH673_jnM (00:38:42)

The plot thickens with the realization that the new generation of 17-year-old boys cast to play the older men’s former selves also feel agency, and offer a revisionist reading of how they should act their roles. The final moments of the film entail a freeze scene in which the younger Makhmalbāf and the younger policeman exchange bread (nūn) and a flowerpot (guldūn) instead of stabbing one another (which is the actual thing that happened). Is the film thus showing the new generation’s advocacy of a different message? Are they adopting a non-violent method over that of previous generations in the past? Interestingly, the final scene shows how the new generation disrupts the narrative by changing the outcome, by exchanging bread for a flowerpot instead of a knife for a gun, and through this revisionist interpretation they offer a non-violent reading of the past—for the sake of the future. As such, Makhmalbāf’s self-reflexive experimental style can be seen as a political critique. By inserting himself into this historical project, Makhmalbāf disrupts the linearity of a presumably autobiographical film, not to highlight his point of view as the only correct way of seeing the world, but rather to make several “political” statements about his personal past, and more broadly about how history is recounted—or should be recounted and revisited.

Clearly, self-reflexivity in Makhmalbāf’s film upends the traditional narrative, and opens the door for a remarkable political reading necessary for understanding the past, present, and the future. The new generation of actors are reconstructing a militant, violent past, to which they do not adhere, and thus they offer a completely new ending, namely the freeze scene with which Makhmalbāf’s film ends. Makhmalbāf’s self-reflexivity thus led to an ending that defies expectations, a reading that values the social and political necessity for revisiting, and transforming, the ways of the past, and at the same time acknowledging the new generation’s different and, perhaps, better choices.

Figure 8: In the final scene of the film, when the girl asks the officer what time it is, he gives her a flowerpot. Nūn-u guldūn (A Moment of Innocence, 1996), Muhsin Makhmalbāf, accessed via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kmlH673_jnM (01:12:42)

In addition to A Moment of Innocence, Makhmalbāf has also made several other self-reflexive documentaries. Salām Sīnimā (Salaam Cinema) was entirely a film about cinema, the role of the director, and the cinematic process.15Muhsin Makhmalbāf, dir. Salaam Cinema (Iran, 1995). When thousands of people showed up to an audition announcement he published in a daily newspaper, he recorded that enthusiasm for movies in this documentary.

Likewise, in Rūzī rūzigārī sīnimā (Once Upon a Time Cinema), Makhmalbāf pays tribute to a hundred years of cinema in Iran by creating a collage of different clips from cinema’s history.16Muhsin Makhmalbāf, dir. Once Upon a Time Cinema (Iran, 1992).

Panāhī’s Re-visionist Re-definition of Film

After the Iranian judiciary issued a verdict against the filmmaker Ja‛far Panāhī in 2010, in the wake of the Green Movement, the celebrated director was forbidden from making movies for twenty years. While that inconceivable verdict was a disruption to his illustrious career, it did not deter the artist from continuing his creative oeuvre. Before the ban on filmmaking, Panāhī had created some remarkable works with wide international circulation such as Bādkunak-i sifīd (White Balloon, 1995), Āynah (The Mirror, 1997), Dāyarah (The Circle, 2000), Talā-yi surkh (Crimson Gold, 2003), and Offside (2005), among others.17Ja‛far Panāhī, dir. The White Balloon (Iran, 1995); Ja‛far Panāhī, dir. The Mirror (Iran, 1997); Ja‛far Panāhī, dir. The Circle (Iran, 2000); Ja‛far Panāhī, dir. Crimson Gold (Iran, 2003); Ja‛far Panāhī, dir. Offside (Iran, 2005).

While these earlier other films follow a rather linear fictional narrative (except in a brief segment in The Mirror), Panāhī’s post-ban films are almost entirely self-reflexive. For example, Panāhī’s Īn yik fīlm nīst (This is Not a Film, 2011), is an autobiographical documentary that situates the filmmaker and the process of filmmaking at the crux of the work.18Ja‛far Panāhī, dir. This is not a Film (Iran, 2011).

In This is Not a Film (2011), we hear a director speaking mainly in a monologue, defying all legally imposed restrictions. There is a defiance felt from the beginning, as the title of his film itself is also in negation: This is Not a Film! Lúcia Nagib argues that, “Panāhī’s films could be seen as a late bloomer of a long modernist tradition in political art whose agenda draws on its own rejection as art.”19Nagib, “2. Jafar Panahi’s Forbidden Tetralogy,” 66. This is Not a Film is a clear allusion to Rene Magritte’s famous surrealist quip, “Ceci n’est pas une pipe,” or “this is not a pipe,” as Nagib also reiterates, which is “a handwritten caption appended to a faithful, even hyperrealist depiction of a pipe, in [Rene Magritte’s] 1929 drawing La Trahison des images (The Treachery of Images).” This negation, which is hard to ignore, has a political provenance, namely originating from his judicial ban from making movies, and his defiance in accepting this injustice. This is Not a Film is filmed thus to oppose those regulations, but at the same time feigning to be within the acceptable parameters of law. Aside from the filming which was itself a defiant act, Panāhī further sent the film to the Cannes Film Festival on a USB hidden inside a cake—another major oppositional move. As such, the very act of filmmaking in Panāhī’s case, and the act of sending it abroad to be seen in major international festivals, was an act protesting the political enterprise that deemed his creative work impermissible.

Hence, This is Not a Film is a movie entirely about his creativity and the process of movie making that Panāhī had to go through during a time of political uncertainties. It is set in his personal apartment—in his living room, his kitchen, his bedroom and even his elevator, with his pet iguana featuring a background role throughout the film. The director offers an up-close and personal glimpse into his everyday life, having been confined to house arrest until the finalizing of his verdict.

This film is also not a traditional film insomuch as the director is making a film in which he is also the narrator of what the film is about. Within it he narrates the story of another one of his films (presumably the one he was forbidden to make) while roaming around on the living room rug and drawing imaginary lines. By narrating the storyline, he thus immortalizes it in film. Panāhī’s narration seems innocuous, but in reality, there is more to this simple tour of a filmmaker’s house. The spectator is required to ask, why is Panāhī filming in his apartment, rather than on a film set? Why is he narrating his film rather than making it? Why is he in front of the camera rather than behind it? Interestingly, Panāhī himself answers these questions in the film itself. In a telephone conversation with his lawyer, we learn that Panāhī is awaiting a verdict on appeal, and in this phone conversation it becomes clear that his restriction from filmmaking, for the duration of twenty years, will not be entirely lifted—maybe only shortened.

Figures 9-10: Panāhī while roaming around on the living room rug and drawing imaginary lines. Īn yik fīlm nīst (This is Not a Film, 2011), Ja‛far Panāhī, accessed via https://www.newyorker.com/video/watch/dvd-of-the-week-this-is-not-a-film (00:00:38-00:01:34)

While Panāhī is restricted from making movies, he uses every medium possible to visually record his predicament. From his conversation with Mujtabā Mīrtahmāsb we see how the cameraman’s semi-professional camera is invited to record the filmmaker’s agonizing solitude, as he is awaiting a harrowing verdict. Mīrtahmāsb walks with the director around his house and provides the necessary solace for an otherwise depressing situation. Further, This is Not a Film was also partially filmed with his son’s camcorder, while another part was taken with his own iPhone camera, amounting to three different mediums that thus highlight the difficulties he went through in making his films. The final product is therefore an edited version of footage taken with all three mediums, with the intention of showing the resilience of activism and political engagement at a tumultuous time in Iran’s contemporary history, immediately following the 2009 unrest. What is significant is the nature of this new activism, which deliberates on its moves, circumnavigates its ways, and patiently heralds a new socio-political consciousness to the new generation. As Nagib mentions, “This is not a Film ends literally with the ‘pyrotechnics’ Adorno and Lyotard describe as the ‘only truly great art,’ as the director observes the defiant Nawrūz bonfire and fireworks from behind the gate of his building where he and his film are confined.”20Nagib, “2. Jafar Panahi’s Forbidden Tetralogy,” 83. In other words, Panāhī’s plight feels compounded with Chahār’shanbah Sūrī (the last Tuesday night of the year before Nawrūz) fireworks that we hear towards the end of the movie. While the pyrotechnics are signs of celebrations which the director cannot attend, at the same time they signal an uneasy and tumultuous public sphere. Confining the director to his private spaces, however, has not deterred him from demonstrating dissatisfaction with the political situation, which is exactly what the censors tried to stop. In other words, censors wanted him to stop creating films that show this public dissatisfaction in society, but Panāhī defies that order and continues to use his camera to tell the story of his own subjectivity in confinement—a theme that he continues not only in This is not a Film, but also in the following movies where he plays himself as the main protagonist, namely, Taxi, Pardah (Closed Curtain), Sih rukh (Three Faces), and finally No Bear.21Ja‛far Panāhī, dir. Taxi (Iran, 2015); Ja‛far Panāhī, dir. Closed Curtain (Iran, 2013); Ja‛far Panāhī, dir. Three Faces (Iran, 2019); Ja‛far Panāhī, dir. No Bear (Iran, 2021).

Figures 11: Panāhī is inside the house, using his mobile phone to film the Chahār’shanbah Sūrī celebrations. Īn yik fīlm nīst (This is Not a Film, 2011), Ja‛far Panāhī, accessed via https://www.newyorker.com/video/watch/dvd-of-the-week-this-is-not-a-film (00:03:34)

Self-reflexivity is the common denominator in all Panāhī’s post-ban films. In Taxi, Panāhī acts as an impartial driver, taking different rides and getting to know the society through the lens of a taxi driver. He is not taking a fare for the ride, but instead he gets their stories which become the subject matter of the film. The process of filmmaking thus becomes a social phenomenon, with strong political undertones. At the same time, the process of filmmaking remains in a vague state. Is the director, who is banned from filmmaking, making a film here, or is he just documenting the ins and outs of the taxi rides? For a lay spectator, the taxi rides and the driver seem real, whereas in reality everything is staged.

The position of the director in the place of a taxi driver, and serving as the film’s protagonist, also further questions the role of film and filmmaking in contemporary Iran. While Taxi seems to be a linear narrative, the intransitivity of the narrative comes to the fore every time we see the director/driver in the close-up and long shots.

In No Bear, Panāhī speaks more openly about his conflicted state and his impossible predicament remaining in his homeland as a filmmaker. Banned from making movies, in No Bear , the director travels to a remote village on the border between Iran and Turkey. His main objective is not clear throughout the film, whether he is there to make another autobiographical documentary, film a romantic feature, find a serene spot to direct his movie online in Turkey, or merely document the customs and traditions of the folks on the border, or all of the above. Throughout the film, Panāhī juxtaposes his philosophical predicament of whether he should stay or leave (albeit illegally), with the stories he hears in the village. In the romantic story he follows, of a couple who decide to elope due to their families’ opposition, we see them dead at the end, shot by border patrols before they could unite in love. Is this meant to be an alarming incident for the director, who may be contemplating crossing the border, in the depth of the night without papers. Panāhī is clearly divided. Should he make a decision that could have fatal consequences, or should he remain in fear in Iran—like the villagers’ fear of a bear that proves to be non-existent. This film remarkably allows the spectator to empathize with the director’s anxieties and fears, and question Panāhī’s conflicted psyche.

Ironically, in the midst of the Women, Life, Freedom uprisings in Tehran, Panāhī went to the Evin prison in support of his friend, Muhammad Rasūluf, was detained. At the prison, the administrators notice Panāhī’s pending sentence and— to everyone’s utter surprise they hold him. Rasūluf and Panāhī spent frightful nights in Evin, for example, as they witness a major fire that happened very close to their ward. They became acquainted with a large number of individuals who were arrested in the aftermath of the Mahsā Amīnī protests after September 2022. Panāhī was released in 2023, and continues making movies. His post-ban movies are significant in their metacinematic characteristics and his experimentations in independent filmmaking. The self-reflexivity in Panāhī’s films clearly disrupt linearity, and provides a political critique.

Conclusion

In the given examples of self-reflexivity from ‛Abbās Kīyārustamī, Muhsin Makhmalbāf, and Ja‛far Panāhī, we see how their films create narrative intransitivity that disrupts traditional narrative, and how these films may not necessarily be named as “political” films, yet they were indeed made “politically” in the Godardian sense. The aforementioned directors have put themselves in the center of an aesthetically subversive representation that narrates their stories, while at the same time posing questions about cultural, economic, and social issues. Most importantly, these films explore the impact of art and cinema in a volatile society. Self-reflexivity—putting oneself and the art creation process at the center of the narration—thus evolves as a signature technique for Iranian filmmakers to traverse the personal and the political.

Examples such as those discussed in this article demonstrate how Iranian filmmakers have used self-reflexive cinema in order to create both thought-provoking and insightful works that challenge traditional narrative structures and offer deeper insights into the complexities of human existence and the art of filmmaking itself. It is important to note that these films have not only earned critical acclaim, both nationally and internationally, but they have also contributed to the rich and diverse landscape of Iranian cinema on both the national and the global stage.

Cite this article

Self-reflexivity, a hallmark of Iranian New Wave cinema, offers a profound means of engaging with political and social issues. Directors like Abbas Kiarostami, Mohsen Makhmalbaf, and Jafar Panahi employ metacinema to blur the boundaries between reality and fiction, creating works that are deeply layered and thought-provoking. By analyzing films such as Close-Up (1990) and A Moment of Innocence (1996), this article demonstrates how self-reflexivity challenges traditional narrative forms and critiques societal constraints. This approach enables filmmakers to navigate censorship while crafting deeply personal and political works that resonate both locally and globally.