The Buttressing Gaze: Neopatriarchal Unconscious and the Biopolitics of Female Visibility in Iranian Cinema

Introduction

In the aftermath of Mahsa Amini’s untimely death in September 2022, following her arrest by the morality police for allegedly wearing an improper hijab, Iranian women took center stage in the Women, Life, Freedom movement. Powerful and poignant protest videos circulated widely, showing women defiantly removed their headscarves and casting them into bonfires, dancing in solidarity and determination. One of the first images of Iranian women protesting against the obligatory hijab in recent decade appeared on the My Stealthy Freedom Facebook page, where women, mainly with their backs to the camera, tossed aside their headscarves in defiance.1For more on My Stealthy Freedom, see Elnaz Nasehi, “The Question of Hijab and Freedom: A Feminist Critical Discourse Analysis of the Facebook Page My Stealthy Freedom,” in If You Wish Peace, Care for Justice, ed. Tuğrul İlter et al. (Famagusta: Eastern Mediterranean University Press, Center of Research and Communication for Peace, 2017), 15–24; Melissa Stewart and Uli Schultze, “Producing Solidarity in Social Media Activism: The Case of My Stealthy Freedom,” Information and Organization 29, no. 3 (2019): 1–23; Grace Yukich Koo, “To Be Myself and Have My Stealthy Freedom: The Iranian Women’s Engagement with Social Media,” Revista de Estudios Internacionales Mediterráneos 21 (2016): 141–57. Later, a widely circulated video from Tehran’s Inqilāb Street showed a young woman stood boldly atop a platform, hair uncovered, waving her white headscarf on a stick.

The Women, Life, Freedom movement foregrounded Iranian women’s resistance against compulsory veiling, linking contemporary protest to a longstanding history of gender-based social activism in Iran. From its inception, confronting the gender-based restrictions has been central to Iran’s social activism. The mid-19th century Babi movement,2Janet Afary and Kevin Anderson, “Woman, Life, Freedom: The Origins of the Uprising in Iran,” Dissent 70, no. 1 (2023): 82–98. Iran’s first significant modern social movement, challenged traditional Shi’i rituals underpinning social and gender hierarchies, particularly compulsory veiling.3The Bábí Faith originated in 1844 as a monotheistic religion founded by the Báb, serving as the foundational precursor to the Bahá’í Faith. Followers of the Bahá’í Faith view the Bábí movement as integral to their religious heritage. The teachings introduced by the Báb significantly disrupted Persian society at the time, as his advocated principles and values directly contested established societal norms, prompting fierce resistance from authorities. Tāhirah Qurrat al-‛Ayn, a prominent female figure in the Babi and later Bahá’í faiths, “is considered the first Iranian woman to preach equality of the sexes and religious freedom.”4Annemarie Schimmel, “Qurrat Al-ʿAyn Ṭāhirah,” Encyclopedia of Religion, accessed January 30, 2024, https://www.encyclopedia.com/environment/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/qurrat-al-ayn-tahirah. Her public unveiling at the 1848 Conference of Badasht symbolized a new era. Her subsequent execution by strangulation and the disposal of her body in a well by Qājār authorities, set a historical precedent for women’s rights activism in Iran.

Under the Pahlavī regime, unveiling symbolized modern progress, while in the Islamic Republic, the veil became a symbol of resistance to Western influence. In both eras, women’s visibility has been contested and politicized through efforts to regulate and redefine their appearance and societal roles.5Elnaz Nasehi, “Ambivalence of Hostility and Modification: Patriarchy’s Ideological Negotiation with Women, Modernity and Cinema in Iran,” International Journal of Advanced Research 8, no. 10 (2020): 542–52. This regulation functions as a form of “biopolitical control”6Michel Foucault, Society Must Be Defended: Lectures at the Collège de France, 1975–76, vol. 1 (New York: Picador, 2003), 239–64. over the female body, where state power operates through managing visibility, dress, and bodily conduct.

In the aftermath of Women, Life, Freedom, the issue of veiling has become more relevant than ever in Iran’s struggle for freedom. While focusing on mandatory hijab might appear to reduce a broader social problem to a single issue, the movement strikes at the core of Iran’s “neopatriarchal unconscious,” an ideological and biopolitical structure that governs which bodies can appear in public and under what conditions. This “buttressing unconscious,” as Nasehi and Kara term it,7Elnaz Nasehi and Nazlı Kara, “Buttressing Strategy: A Theory to Understand the Neopatriarchal Unconscious of Iranian Society/Cinema,” Revista de Cercetare si Interventie Sociala 60 (2018): 157–73. operates as a mechanism of biopower and sustains the patriarchal order by framing women as inherently destabilizing and thus requiring containment through moral, legal, and aesthetic means.

This biopolitical unconscious extends into the realm of cultural production, particularly cinema, where it not only governs what can be shown, but also how female bodies are allowed to materialize on screen. It manifests through buttressing strategies and the buttressing gaze, which regulate empowered female characters by limiting their visual and narrative agency.

This research reviews the previously theorized “buttressing unconscious” of neopatriarchal Iranian society and expands it by tracing its cinematic inscriptions. Through analysis of narrative structure, cinematography, and mise-en-scène, it reveals how Iranian cinema participates in a biopolitical apparatus that shapes the visibility, desirability, and legibility of femininity. It introduces the buttressing gaze as a specific form of neopatriarchal visual governance, aligning with Kordela’s description of cinema’s role in the materialization of potential bodies through the logic of control.8Kiarina Kordela, “The Gaze of Biocinema,” in European Film Theory, ed. Temenuga Trifonova (London: Routledge, 2009), 151–64.

Neopatriarchal Unconscious of Iranian Society

In her analysis of the Islamic Republic’s stance on women’s femininity and sexuality in Iran, Moradiyan Rizi describes “cinematic interdictions” as “the visual part of a general strategy, authorized by the government, regarding gender segregation and sexual hierarchy.”9Nayereh Moradyan Rizi, “Iranian Women, Iranian Cinema: Negotiating with Ideology and Tradition,” Journal of Religion & Film 19, no. 1 (2015): 7. According to her, “the Islamic regime buttressed, and still buttresses, this gender segregation by claiming to protect women’s virtue and integrity from Western commodification.”10Nayereh Moradyan Rizi, “Iranian Women, Iranian Cinema: Negotiating with Ideology and Tradition,” Journal of Religion & Film 19, no. 1 (2015): 7.

While Moradiyan Rizi identifies a “general strategy” that reinforces gender segregation within the Islamic regime, she does not fully theorize its structural depth. This is further developed by Nasehi and Kara, who conceptualize it as the “neopatriarchal unconscious of Iranian society.” They argue that “under the obligatory wearing of hijab, veiling is coerced through […] ‘buttressing strategy,’ which is used to justify the existence of the veil as a protector of society from corruption.”11Elnaz Nasehi and Nazlı Kara, “Buttressing Strategy: A Theory to Understand the Neopatriarchal Unconscious of Iranian Society/Cinema,” Revista de Cercetare si Interventie Sociala 60 (2018): 164.

Before delving further into this theory, the concept of “buttress” warrants closer attention. According to Merriam-Webster, as a noun, “buttress,” means “a projecting structure of masonry or wood for supporting or giving stability to a wall or building” and “something that supports or strengthens.” As a verb, it means “to give support or stability to (a wall or building) with a projecting structure of masonry or wood: to furnish or shore up with a buttress.” It also means “to support and strengthen.”12Merriam-Webster, “Buttress,” Accessed April 15, 2025. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/buttress. In architectural terms, a buttress holds up a wall and “serving either to strengthen it or to resist the side thrust created by the load on an arch or a roof.”13Britannica, “Buttress,” Accessed April 15, 2025. https://www.britannica.com/technology/buttress-architecture.

According to the definitions cited above, a buttress—or the act of buttressing—has a two-fold functions: to support a wall and prevent it from collapsing. Therefore, while a buttress ‘empowers’ a valuable part of the structure, it also implies a potential ‘threat’ of failure. Drawing on some of the most repeated promoted slogans about hijab in Iran, Nasehi and Kara use the metaphor of “buttress” to theorize neopatriarchal unconscious of Iranian society, particularly its buttressing perspective on femininity. This perspective carries the same dual implication: to empower and to disarm a threat.

From this neopatriarchal standpoint, the obligatory practice of veiling is not a benign mechanism for protecting women’s inner virtue or a tool for empowerment, as suggested by official hijab propaganda. In contrast, when imposed coercively, veiling becomes a buttressing tool “to protect the patriarchal power and sovereignty through buttressing [disarming] the posited threatening women’s corrupted-to-be self. For, it is assumed that when an ‘unveiled’ woman –read as empowered and unconfined- unavoidably transgresses the boundaries and falls down, the whole structure of male-dominated family and society would fall down and become morally corrupted.”14Elnaz Nasehi and Nazlı Kara, “Buttressing Strategy: A Theory to Understand the Neopatriarchal Unconscious of Iranian Society/Cinema,” Revista de Cercetare si Interventie Sociala 60 (2018): 167-68. The problem lies not only in the fact that mandatory veiling denies women freedom of choice, but more deeply in the buttressing view of femininity that constructs womanhood as a structural risk; a threat that must be managed to keep the edifice of “women’s honor” from collapse. As Moradiyan Rizi suggests, the Islamic regime’s strategy for enforcing gender segregation is only one element of a broader ideological apparatus surrounding femininity. Within this framework, women are buttressed through compulsory veiling to contain their perceived danger.

Understanding this neopatriarchal unconscious is essential for analyzing its cinematic manifestations, specifically, how it shapes the portrayal of “unveiled” female characters and reflects broader social structures, gendered relationships, and the institutionalization of patriarchal authority. While Nasehi and Kara have theorized Iranian neopatriarchy at both societal and cinematic levels, I will focus on the specific implications of this phenomenon in the realm of cinema.

Neopatriarchal Unconscious of Iranian Cinema

The Islamic Revolution of 1979 marked a profound rupture in Iranian society, transforming its socio-economic and cultural landscape. One of the cultural domains most immediately affected was Iranian cinema, which underwent a dramatic shift in response to the Islamic Republic’s policies of Islamization and anti-Western orientation. As a result, cinema was compelled to conform to newly enforced codes of modesty, particularly impacting the portrayal of women and heterosexual relationships.

Despite these restrictions, post-revolutionary Iranian cinema did not devolve into mere propaganda. Filmmakers responded to the new censorship regime in various ways. Some embraced the ideological codes—what Naficy terms “populist cinema,” which “affirms post-revolutionary Islamic values more fully at the level of plot, theme, characterization, portrayal of women and mise-en-scène.”15Hamid Naficy, “Islamizing Film Culture in Iran: A Post-Khatami Update,” in The New Iranian Cinema: Politics, Representation and Identity, ed. Richard Tapper (London and New York: I.B. Tauris, 2002), 30. Others, like ‛Abbās Kiyārustamī, avoided depicting bodies, relationships, and spaces that, as Khosrowjah puts it, had to be “misrepresented in order to be represented.”16Hossein Khosrowjah, “Neither a Victim nor a Crusading Heroine: Kiarostami’s Feminist Turn in 10,” Situations: Project of Radical Imagination 4, no. 1 (2011): 57. Other filmmakers sought ways to negotiate with and survive within these constraints.

The divergent responses of Iranian filmmakers gradually loosened the rigidity of the censorship codes, opening fissures within the regime’s ideological apparatus and allowing room for negotiation and subtle resistance. As Zeydabadi-Nejad observes, the ambiguity surrounding censorship definitions and the absence of a “unitary censorship mechanism” offer filmmakers with the space to maneuver within, and even subvert the system.17Saeed Zeydabadi-Nejad, The Politics of Iranian Cinema: Films and Society in the Islamic Republic (New York: Routledge, 2010), 30. It is in this negotiated space that the genre of social films emerged. Naficy refers to these as ‘art cinema’—films that aim to critique “social conditions under the Islamic government.”18Hamid Naficy, “Iranian Cinema under the Islamic Republic,” in Images of Enchantment: Visual and Performing Art of the Middle East, ed. Sherifa Zuhur (Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press, 1998), 230.

As Iranian cinema sought to redefine itself under newly imposed codes of modesty, it began to distinguish itself from dominant cinematic traditions, particularly those of the West. To navigate the restrictions, such films often use metaphor and symbolism as creative strategies to circumvent the imposed boundaries. A notable instance is the employment of children as symbolic figures who, unlike adults, are permitted to freely dance, sing, and express heterosexual emotions on screen, serving also as a vehicle for critiquing a restrictive society.

Directors developed a range of allusive techniques, such as “creating allegorical figures, displacing plots and deferring cinematic closure.”19Negar Mottahedeh, “New Iranian Cinema: 1982–Present,” in Traditions in World Cinema, ed. R. B. Badley (New Brunswick and New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 2006), 180. Over time, the repeated use of these strategies became standardized, forming a distinct set of cinematic conventions within post-revolutionary Iranian cinema.

Mottahedeh highlights how the deliberate rejection of the “conventionalized language of Hollywood realism” influenced not only narrative structures, but also the visual and formal aspects of filmmaking. Consequently, directors in the 1980s and 1990s faced the challenge of reimagining the “cinematic grammar and language of film”20Negar Mottahedeh, “New Iranian Cinema: 1982–Present,” in Traditions in World Cinema, ed. R. B. Badley (New Brunswick and New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 2006), 180. within the constraints of the Islamic Republic’s ideological and aesthetic mandates. She cites a scene from ‛Alī Hātamī’s Dil-Shudagān (The Enamored, 1992), set during the Qājār Dynasty, where a couple’s emotional farewell is portrayed. In this scene, symbolic elements—a cat and a musical instrument—are used to stand in for representations of heterosexual love and intimacy on screen:

The musician and his wife then sit down by a round table on which rests a set of book, a santoor (a string instrument) and a cat. The couple discuss the things that join them in their affections for one another and review the promises and sacrifices they have made in their devotion to music. The wife speaks to her husband with an averted gaze while she strokes the musical instrument-the signifier of their common love- with her palm… the close up frames the cat, who we first see being stroked by the musician’s hand, and then by his wife’s hand.21Negar Mottahedeh, “New Iranian Cinema: 1982–Present,” in Traditions in World Cinema, ed. R. B. Badley (New Brunswick and New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 2006), 180-82.

This allegorical language of allusion in post-revolutionary Iranian cinema enables filmmakers to subvert censorship codes while still operating within the regime’s ideological framework. As this visual and narrative strategy emerges from a broader structure of veiling and containment, it inadvertently perpetuates the very neopatriarchal logic it seeks to evade.

Kiarina Kordela’s notion of the subtractive gaze in biocinema is particularly illuminating here. Kordela argues that biocinema often denies the spectator an “unambiguous gaze to identify with,” leaving the body in a state of potentiality—unmaterialized and thus symbolically immortal.22Kiarina Kordela, “The Gaze of Biocinema,” in European Film Theory, ed. Temenuga Trifonova (London: Routledge, 2009), 161. This subtractive or absent gaze becomes a site of resistance precisely because it obstructs any clear stable mapping of power relations or fixed ideological positions. In the context of Iranian cinema, this absence emerges through veiled female figures, deferred closures, and fragmented narrative resolutions—strategies that both enable survival under censorship and render femininity in ambiguous, non-totalizing terms. However, while these strategies resist overt interpellation by state ideology, they are also symptomatic of the “buttressing unconscious”—a structure that sustains femininity as enigma and reinforces patriarchal legibility through its very gestures of refusal.

To further elaborate the buttressing unconscious, we can again turn to Kordela’s theorization of the gaze of biocinema, which builds on Foucault’s concept of biopolitics and Lacanian psychoanalysis. For Kordela, biocinema is not concerned with representation, but rather with the production and regulation of life itself, where visibility and biological existence are interwoven as sites of control, where “the body finds its flesh” only through the construction of gazes.23Kiarina Kordela, “The Gaze of Biocinema,” in European Film Theory, ed. Temenuga Trifonova (London: Routledge, 2009), 153-55. In this sense, the buttressing strategies in Iranian cinema function as biopolitical techniques —not only of veiling, but also of life regulating life, governing women’s visibility to neutralize their political and affective power. “Since capitalism calls into question the materiality of the body, biopolitics’ primary concern is not so much the control of pregiven material bodies, but the materialization of potential bodies through the bestowal of a gaze.”24Kiarina Kordela, “The Gaze of Biocinema,” in European Film Theory, ed. Temenuga Trifonova (London: Routledge, 2009), 155. The buttressing unconscious, then, may be read as a culturally specific articulation of the broader biocinematic regime—one that surveils, regulates, and instrumentalizes gendered bodies through aesthetic means.

With this new perspective in mind, the concept of “veiling/unveiling” also requires closer examination. A “veiled” woman is not necessarily one who practices the sartorial aspect of the hijab, nor does “unveiling” always imply the absence of the sartorial practice. Nasehi and Kara identify three distinct aesthetic functions of veiling in Iranian cinema: first, sartorial practice; second, behavioral codes of modesty; and third, sex segregation. What these functions share in common is the presence of a barrier, a curtain that serves to hide, segregate, and buttress. In contemporary Iranian cinema, where women must appear in accordance with Islamic dress codes, “unveiling” pertains to the other two dimensions of veiling: behavioral codes and segregation in public spaces. Therefore, I define an “unveiled” woman as one who is empowered, unconfined, and uncontained—even if appears onscreen with the sartorial signifiers of hijab mandated by the Islamic Republic.

Cinematic Inscription: Buttressing the Empowered Threat

The neopatriarchal unconscious of Iranian society operates as a biopolitical apparatus, continuously reproduced and reshaped through cultural forms—particularly cinema. Within this framework, women are viewed not only as morally precarious, but also as bodies whose visibility and conduct must be tightly regulated to preserve a male-dominated social order. As Nasehi and Kara argue, this unconscious manifests in film through two primary narrative mechanisms. First, the ‘corrupted-to-be’ view of women inevitably portrays ‘empowered/unveiled’ female characters as those who, in attempting to break free from patriarchal constraints, disrupt the initial equilibrium and ultimately cause catastrophe.

Second, as the narrative moves toward a state of reparation and a new order is established, the female unveiled characters are buttressed, controlled, or made to bear the consequences of their transgressive or empowerment.25Elnaz Nasehi and Nazlı Kara, “Buttressing Strategy: A Theory to Understand the Neopatriarchal Unconscious of Iranian Society/Cinema,” Revista de Cercetare si Interventie Sociala 60 (2018): 168.

This buttressing of femininity takes cinematic form in three ways. The first concerns the sartorial aspect of veiling: does the representation of women in film challenge the mandatory hijab or merely reproduce the officially sanctioned ideal? Secondly, regarding behavioral modesty, the buttressing unconscious restricts female characters from enacting subversive gestures that might unsettle patriarchal norms. Thirdly, the function of sex segregation gives rise to a distinct visual strategy in Iranian cinema: the emergence of a buttressing gaze.

Buttressing Gaze: Theory

As noted, the three functions of veiling in Iranian cinema involve barriers, curtains that conceal, divide, and “buttress.” These barriers underpin a new gaze that is veiled, mediated, segregated, and as Hamid Naficy describes, “averted.”

Naficy’s notion of the “averted gaze” refers to a distinct cinematic mode shaped by “modesty and the psychology and ideology of the dual self.”26Hamid Naficy, “The Averted Gaze in Iranian Postrevolutionary Cinema.” Public Culture 3, no. 2 (1991): 35. Within Western feminist film theory, the female figure is marked by ambiguity, simultaneously desirable and threatening—often through the trope of castration. Iranian cinema presents a parallel, yet culturally specific, tension: women evoke not castration but potential disgrace and corruption. In this context, Naficy contrasts the gaze in Western and Islamic traditions. While Western feminist theory positions the gaze as a “controlling, sadistic agent that supports phallocentric power relations,” in the Islamic framework, Naficy argues, “the aggressive male gaze impacts not so much the female target who receives it but the male owner of the gaze… due to the male’s inherent weakness in the face of sexual temptation.”27Hamid Naficy, “The Averted Gaze in Iranian Postrevolutionary Cinema.” Public Culture 3, no. 2 (1991): 34. This, the unveiled woman—resistant, unconfined, and empowered—poses a direct challenge to patriarchal authority.

Naficy suggests that the “sadistic pleasure” traditionally associated with the gaze in Western feminist theory is, in Islamic discourse, replaced by a “masochistic pleasure” experienced by men, who become “humiliated” and “abject” in the presence of women. He introduces the concept of the “averted gaze” as a mechanism “to prevent such humiliation and abjection and to avoid or, alternatively, to encourage the resulting masochistic pleasure.” This form of looking, he explains, is “anamorphic,” distorted by the voyeuristic desires and underlying anxieties of the viewer.28Hamid Naficy, “The Averted Gaze in Iranian Postrevolutionary Cinema.” Public Culture 3, no. 2 (1991): 35. The desexualization—or as Naficy terms it, the androgynization—of the cinematic gaze through the averted gaze results from the new cinematic language developed in post-revolutionary Iranian cinema, as previously discussed.

Building on Naficy’s notion of the averted gaze, Ghorbankarimi contends that while this framework may have been relevant to certain films from the early post-revolutionary period, it does not hold for works produced after the first decade. She argues, first, that Islamic ideology has not been uniformly or fully implemented in Iranian cinema, and second, that “the individuals in the film industry are not necessarily amongst the most religious Iranians.”29Maryam Ghorbankarimi, “A Colourful Presence: An Analysis of the Evolution in the Representation of Women in Iranian Cinema since the 1990s,” (PhD diss., University of Edinburgh, 2012), 49. She further notes that “a few years after the revolution, especially after the end of the Iran-Iraq war, a close-up or a two shot of a man and woman on screen was no longer taboo,” suggesting a relaxation of earlier visual restrictions in Iranian cinema.30Maryam Ghorbankarimi, “A Colourful Presence: An Analysis of the Evolution in the Representation of Women in Iranian Cinema since the 1990s,” (PhD diss., University of Edinburgh, 2012), 51. Finally, she challenges Naficy’s framing of the veil as a source of mystery and curiosity that inadvertently reinforces a voyeuristic gaze. In contrast, she presents an alternative view, conceptualizing the veil as “an inherent aspect that should not outshine the whole film industry.” Indeed, as Ghorbankarimi points out, Naficy’s notion of the averted gaze cannot be universally applied to all post-revolutionary Iranian films, and it tends to present a monolithic view of how the institutionalized practice of veiling is reflected on screen. However, her argument overlooks the risk of normalizing veiling as merely “an inherent aspect” of Iranian cinema and dismissing its influence on narrative, aesthetic, and stylistic dimensions of filmmaking.

Ghorbankarimi further argues that “to the people living in Iran, the veil is no longer a priority for change; if the audience makes it past the surface of the veil, underneath is not so different to what they are used to either. The headscarf has become part of Iranian culture.”31Maryam Ghorbankarimi, “A Colourful Presence: An Analysis of the Evolution in the Representation of Women in Iranian Cinema since the 1990s,” (PhD diss., University of Edinburgh, 2012), 53. Such a stance not only proves to be flawed in light of decades of resistance by Iranian women and the recent ‘Women, Life, Freedom’ uprising, but also risks reinforcing the existing ideological status quo. For this reason, I propose a reconceptualization of the averted gaze by taking into account the three distinct functions of veiling in Iranian cinema. Accordingly, the term buttressing gaze describes the new visual regime shaped by the cinema’s allegorical language and its underlying buttressing approach to femininity.

Compared to the concept of the averted gaze, the buttressing gaze is more appropriate for analyzing Iranian cinema, as it captures a broader range of veiling strategies—including covered, mediated, averted, and segregated forms. These varying modes of the buttressing gaze emerge from the differing degrees of permeability and penetrability of the metaphorical veil they establish. Based on this, the buttressing gaze can be divided into three main categories: first, the full-covering gaze, which entirely erases women from the visual field, leaving no room for access or visibility; second, the mediating or deferring gaze, which places women behind a barrier that allows only limited permeability; and third, the spatial-segregating gaze, which constructs gendered spaces within the mise-en-scène. These forms are not rigidly separate but often intersect and coexist within cinematic representation. The following section explores how these different manifestations of the buttressing gaze operate in Asghar Farhādī’s selected films: Dancing in the Dust (Raqs dar ghubār, 2003); The Beautiful City (Shahr-i zībā, 2004); Fireworks Wednesday (Chahārshanbah-sūrī, 2006); About Elly (Darbarah-yi Ilī, 2009); and A Separation (Judā’ī-i Nādir az Sīmīn, 2012).

Veiled Behind the Walls

While reflecting on the origins of Dancing in the Dust, Farhādī describes his initial motivation with the following remark:

I always used to pass by some place where there was a bridge under which there was a very poor house for immigrants. When I passed on the bridge, I could see everything in their house. It was a naked house. You could see everything, even their bedroom. It was like a naked woman sitting under the bridge. When I wrote the story about the prostitute, I thought her residence could be that house.32Tina Hassannia, Asghar Farhadi: Life and Cinema (New York: The Critical Press, 2014), 18.

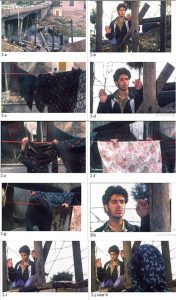

When translated into Asghar Farhādī’s cinematic language, this initial, vivid image that inspired the story becomes obscured—the “naked” woman, once central in the imagination, is rendered veiled and nearly invisible on screen. In Dancing in the Dust, Rayhānah’s mother, despite functioning as a key narrative catalyst, is visually marginalized. Her appearance is limited to just two brief scenes, both framed through the full-covering gaze. The first occurs in the opening sequence of the film, where Rayhānah and Nazar encounter each other for the first time aboard a minibus. (Figure 1).

The mother does not have a visible presence within the minibus. However, she is framed as she disembarks, following Rayhānah. From the moment she steps out of the minibus (1-a) until her swift exit from the frame (1-b cont’d), she is only briefly visible in a long shot for about five seconds. Rayhānah and her mother are then followed by Nazar, who finds them beneath a bridge. Through a point-of-view shot from Nazar’s perspective, Rayhānah and her mother are seen entering their home (1-c).

Figure 1

In the second scene, where Rayhānah’s mother engages in a dialogue with Nazar, they are spatially segregated, even though Nazar is now married to Rayhānah and, therefore, considered mahram to his mother-in-law (Figure 2). The full-covering gaze intersects with the mediating gaze in this scene, as the audience can still hear Rayhānah’s mother’s voice. Despite her limited visual presence, her spatial presence is suggested, albeit through the filter of the full-covering gaze.

Figure 2

The first shot of this scene shows Rayhānah’s mother from a distance in a very long shot, hanging laundry on the roof of her house, which is positioned at the same level as the highway and the bridge. In this frame, she is obscured behind barbed wire (2-a). The following shot shifts to Nazar, approaching the barbed wire in a medium shot (2-b). The rest of the scene continues to depict Rayhānah’s mother from behind the laundry, as she engages in dialogue with Nazar, who is framed in medium close-up and close-up shots, still positioned behind the barbed wire (2-c to 2-h). The final shot of this sequence spatially positions Nazar and Rayhānah’s mother together in one frame. In a medium over-the-shoulder shot, Nazar is initially framed alone on the left (2-i), and after a moment, Rayhānah’s mother enters the frame from the right side, her face turned away from the camera (2-j cont’d). Throughout this shot, Nazar remains the primary subject, maintaining visual dominance until the scene concludes.

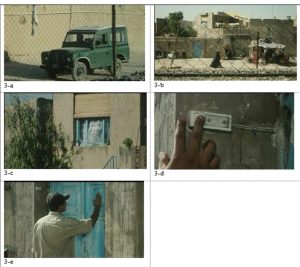

While the last analyzed scene incorporates all three forms of buttressing gaze, it still maintains Rayhānah’s mother as fully veiled. A similar scene appears in Beautiful City, where Fīrūzah, Akbar’s sister, and her home are introduced for the first time (Figure 3). However, unlike the previous scene, this one does not employ a full-covering gaze. Instead, it creates a mediating gaze, which defers Fīrūzah’s presence, keeping her visually distant and obscured.

Figure 3

After A‛lā is released from the rehabilitation center, the manager gives him a ride to Akbar’s sister’s house. In the first shot following his release, the manager’s old jeep is shown in a pan shot from behind a fence (3-a), which separates the railroad zone from the rest of the city. Fīrūzah’s house lies on the other side of this fence. Her home is distanced both from the broader urban area and the male-dominated world of the rehabilitation center, which functions almost like a prison. Consequently, A‛lā must cross these boundaries in order to enter Fīrūzah’s domain.

The next shot presents Fīrūzah’s point-of-view of her house from behind the fence (3-b). The house is an old two-story structure with a blue entrance door. To the right of the frame, there is a small, shabby kiosk that belongs to Fīrūzah’s addicted husband, though it is not yet revealed that they are divorced. Unlike Rayhānah’s mother’s house, Fīrūzah’s house is not fully visible from the inside. The most noticeable features include a line of laundry on the second-floor balcony and a blue wooden window, behind which a white lace curtain moves gently in the wind. The second shot of Fīrūzah’s house (3-c) emphasizes the curtain’s movement. Despite the rundown exterior of the house, the space is feminized through various elements in the mise-en-scène, such as a tall, lively tree in the yard, plant vases on the staircase and beside the window, the elegant lace curtain, the laundry line, and the choice of blue for the door, window, and Fīrūzah’s scarf when she first appears in this scene.

A‛lā’s entry into Fīrūzah’s feminized space does not occur immediately; rather, it is mediated through a deferring gaze. The director underscores this separation by highlighting the act of pressing the doorbell in a deliberate insert shot (3-d), which is then followed by a medium shot of A‛lā knocking on the door (3-e). These choices deliberately delay the narrative progression and reinforce the spatial and symbolic separation between A‛lā and Fīrūzah.

Iranian society is deeply rooted in a longstanding tradition of gender segregation. As Naficy notes, “Every social sphere and every artistic expression must be gendered and segregated by some sort of veil or barrier inscribing the fundamental separation and inequality of the sexes.”33Hamid Naficy, A Social History of Iranian Cinema: Volume 4. The Globalizing Era, 1984–2010 (Durham: Duke University Press, 2012), 102. Following the revolution, sex segregation in public spaces—including schools, beaches, sports facilities, and public transportation—was systematically mandated and enforced. These gender-based divisions have had far-reaching implications, as they “deprived Iranian women of access to high-ranking positions, such as the presidency and judgeships. Women are also barred from attending certain public spaces such as sports stadiums.”34Layla Mouri, “Gender Segregation Violates the Rights of Women in Iran,” Iran Human Rights Documentation Center, September 3, 2014, accessed April 5, 2016, https://www.iranhumanrights.org/2014/09/gender-segregation/.

This gendered division of space is also reflected in traditional Iranian architecture, which, as Mottahedeh argues, is “symptomatic of cultural perception of veiling and visuality.”35Negar Mottahedeh, Representing the Unpresentable: Historical Images of National Reform from the Qajars to the Islamic Republic (New York: Syracuse University Press, 2008), 3. Mottahedeh highlights the traditional Iranian architectural model that organizes domestic space into two distinct zones: the andarūnī (interior) and the bīrūnī (exterior). The andarūnī functioned as a harem-like space designated for preserving women’s privacy, while the bīrūnī served as a semi-public area within the home where guests and outsiders could be received. This gendered spatial segregation is not only reflected in architectural design but also becomes embedded in cinematic representation, shaping how space and gender roles are portrayed on screen.

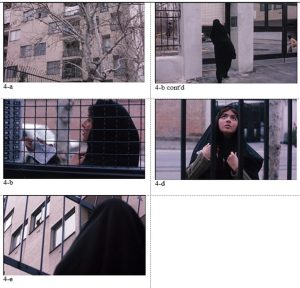

In Fireworks Wednesday, the moment Rūhī arrives at Muzhdah and Murtazā’s building is introduced through a developing shot (4-a) in which the camera simultaneously tracks in and tilts downward, eventually settling into an eye-level full shot as Rūhī enters from the left and approaches the entrance door (4-b cont’d). Although the building lacks a solid boundary wall, it is surrounded by barred enclosures that function analogously to the fences in Beautiful City and the barbed wire in Dancing in the Dust. The subsequent medium close-up frames Rūhī from behind the bars as she presses the doorbell (4-c). Much like A‛lā’s deferred entry into Fīrūzah’s domain, Rūhī’s access is also delayed—the broken doorbell obstructs immediate communication. This malfunction symbolically reinforces the couple’s isolation from the outside world. However, this delay—produced by the mediating gaze—grants Rūhī the opportunity to notice the broken window of Muzhdah and Murtazā’s apartment through the barred wall (4-d/4-e), offering an initial glimpse into the domestic unrest she is about to encounter.

Figure 4

Unlike the scenes in Beautiful City and Dancing in the Dust, where gender-based spatial segregation is foregrounded, the scene from Fireworks Wednesday highlights Rūhī’s separation from Murtazā and Muzhdah primarily through class distinctions. With the exception of About Elly, which transports a group of Tehranis to a remote northern region of Iran, the films analyzed are predominantly set in Tehran—a city dense with symbolic significance as the epicenter of Iran’s political tensions and social transformations.

In recent decades, rapid population growth, internal migration, and urban expansion have profoundly transformed Iran’s class structures. Tehran, as a sprawling metropolis, reflects these shifts most vividly, with a pronounced class hierarchy shaped by cultural, economic, and social factors—each of which is spatially inscribed across the city. Home to a large population of migrants from other regions, Tehran reveals a complex pattern of socio-spatial segregation. As Mehryar and Sabet observe, “Segregation in Tehran has taken different shapes in different ways, evolving hand in hand with certain social changes.”36Sara Mehryar and Sara Sabet, “Socio-Spatial Segregation Dimensions in the City of Tehran: Measurement and Evaluation of Current Segregated Areas,” paper presented at Urban Change in Iran, International Conference, University College London, November 8–9, 2012, https://www.academia.edu/3411397/Socio_Spatial_Segregation_Dimensions_in_the_city_of_Tehran. Despite undergoing significant transformations over time, the city’s urban landscape still adheres to a geophysical hierarchy that mirrors its class divisions.

This spatially segregated mise-en-scène provides Farhādī with a powerful narrative device to explore themes of division and disconnection. In A Separation, the contrast between the lives of Nādīr and Sīmīn—a middle-class couple living in a central Tehran neighborhood—and Rāziyah and Hujjat—residents of a modest, likely rented home on the lower socioeconomic periphery of the city—highlights entrenched class disparities. Farhādī depicts not only the physical and emotional demands imposed on Rāziyah, who must commute daily from the suburb while pregnant with her young daughter, but also the emotional burdens exacerbated by her husband’s unemployment and volatility. Her miscarriage, which occurs while she is secretly working, becomes a turning point that reveals the psychological toll of this divide. Rather than appreciating her efforts, Hujjat responds with anger, intensifying her emotional isolation.

Spatial segregation in A Separation is thus more than a setting; it serves as a symbolic and physical space that embodies broader societal rifts: between men and women, spouses, generations, individuals and institutions, tradition and modernity, and most starkly, between the lower and middle classes, as well as conflicting notions of justice and morality.

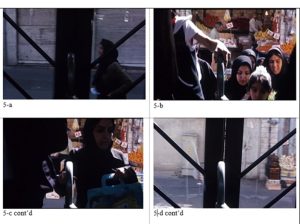

In Firework Wednesday, Farhādī similarly engages the spatially segregating gaze through a sequence of three shots that depict Rūhī’s commute to work (Figure 5). The scene opens with a static, symmetrically framed interior shot of a bus, its door forming a central axis.

Figure 5

As Rūhī runs to catch the bus (5-a), the next shot cuts to the bus door opening, showing both male and female passengers boarding through gender-segregated entrances. Each group briefly touches the dividing metal bar as they enter, symbolizing the fragility of this imposed separation (5-b/5-c). Once boarded, the door closes, and the bus departs (5-d). In the following shot (Figure 6), Rūhī opens a window and extends her hand, along with part of her scarf and chador, into the air. The compositional parallel to the previous shot—each frame split into two vertical halves—highlights the symbolic act of opening a barrier (the window). In the context of gender segregation, this gesture becomes a quiet but pointed active resistance, signaling a desire to breach confined boundaries.

Figure 6

While gender and class segregation pervade both private and public spheres, female characters respond to these constraints in distinct ways across Farhādī’s films. In Dancing in the Dust, the sex-segregating gaze renders Rayhānah’s mother invisible. In contrast, Fīrūzah in Beautiful City asserts her control over the boundaries of her domestic space.

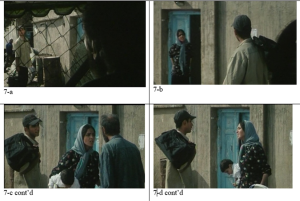

In one scene from Beautiful City (Figures 3 and 7), no one answers the door. Fīrūzah’s ex-husband, seated in a kiosk separated from her house by a barred window (7-a), tells A‛lā that she is not home. After A‛lā buys a drink, Fīrūzah opens the door when her baby, left by his father, crying (7-b). While taking her child inside, she scolds the father his negligence. When A‛lā asks if she is Akbar’s sister, her ex-husband attempts to interject, asserting that no one can enter without his permission. However, the film makes clear that Fīrūzah has agency and controls the boundaries of her private sphere.

Figure 7

In a three-shot sequence involving Fīrūzah and the two men, she is positioned between them, engaging in a verbal confrontation with her ex-husband, telling him that the situation has nothing to do with him (7-c cont’d). In the same shot, she forces him to return to his kiosk, and the dialogue continues between her and A‛lā in a two-shot (7-d cont’d).

Fīrūzah’s control over her private and public boundaries is further illustrated in other scenes. For instance, the lace curtain on her window acts as a form of surveillance, providing Fīrūzah with a panoptical view of the outside world—allowing her to observe without being seen (Figure 7-a/b). The curtain serves as a permeable veil through which Fīrūzah, though veiled, can penetrate and surveil the outside world. However, when she leaves the curtain open, it facilitates communication by blurring the boundaries between the public and private spheres.

The interplay of veiling and surveillance speaks to broader visual and psychoanalytical dynamics. The inscription of female figures into invisibility through the buttressing gaze aligns with psychoanalytic suspicion regarding the realm of the visible. Although psychoanalysis often treats the visible with suspicion, this skepticism does not inherently align with feminist concerns. Mary Ann Doane highlights this issue, arguing that the instability of vision is frequently projected onto representations of women or the feminine:

The veil functions to visualize (and hence stabilize) the instability, the precariousness of sexuality. At some level of the cultural ordering of the psychical, the horror or threat of that precariousness (of both sexuality and the visible) is attenuated by attributing it to the woman, over and against the purported stability and identity of the male. The veil is the mark of that precariousness.37Mary Ann Doane, Femmes Fatales: Feminism, Film Theory (New York: Routledge, 1991), 46.

Laura Mulvey asserts that “cinema is ‘about’ seeing and the construction of the visible by filmic convention. What is represented is inevitably affected.”38Laura Mulvey, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” in Issues in Feminist Film Criticism, ed. Patricia Erens (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1990), 28–40. What remains unrepresented is equally impactful, carrying an affective function akin to that of what is visible. Absence itself stimulates curiosity and invites connotations. In this way, women in Farhādī’s cinema transform into enigmatic, unfathomable figures, where their invisibility becomes as significant as their presence.

Rayhānah’s mother, Elly, and other buttressed female figures are mysterious ciphers who raise curiosity. In themselves, women are of slightest importance as their desires and feelings have no place within the diegesis. They are faceless female figures whose presence provokes a strong feeling—a haunting mystery. Mulvey draws on Budd Boetticher, the American film director, to summarize this view: “what counts is that the heroine provokes, or rather what she represents. She is the one, or rather the love or fear she inspires in the hero, or else the concern he feels for her, who makes him act the way he does. In herself the woman has not the slightest importance.”39Laura Mulvey, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” in Issues in Feminist Film Criticism, ed. Patricia Erens (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1990), 33.

As in About Elly, the character of Elly herself is inconsequential. What matters is that her absence drives the narrative forward. Elly’s subjective perspective is effaced by the film, which aligns itself with the group’s gaze rather than hers. Elly is continually segregated from the rest of the group. While everyone gathers on the picnic mat (8-a), Elly tends to the children (8-b). When the group begins discussing the matchmaking purpose of the trip, each person shares their thoughts and judgments about Elly. As she returns to the group, she is framed through a mediating gaze, seen from behind a barrier of bushes.

Figure 8

In the volleyball scene, Elly is the only female character who participates in the game, and the camera predominantly focuses on her, albeit through a mediating gaze (Figure 9). The first shot of the scene begins with the camera tilting down from the sky, following the ball until it frames Elly in a medium shot as she jumps to hit it (9-a).

In a series of subsequent shots, Elly is depicted behind the volleyball net, with her face not fully visible (9-b to 9-d). When she announces that she has to leave, the camera follows her in a long shot as she exits the yard (9-e to 9-g cont’d). This prolonged, veiled image of Elly serves two functions: on one level, it prompts the audience to unravel her as an enigma, and on another, it creates a moment of suspense, signaling a potential unspoken message.

Figure 9

Drawing on Susan Stewart, Doane explores the prevalence of close-ups of women in cinema, which she argues reflect the male gaze—where a woman’s face becomes a text to be read by others. Expanding this argument, Doane examines how women’s faces in close-ups are often “masked, barred, shadowed, or veiled,” creating an additional layer between the camera and the spectator.40Mary Ann Doane, Femmes Fatales: Feminism, Film Theory (New York: Routledge, 1991), 48. She identifies several functions of the veil, noting its dual role as both “protective” and “hiding”: it shields a woman’s face from light, heat, and the gaze; conceals secrets or unwanted features like aging or scars; and hides an absence. In the volleyball scene discussed above, the mediating gaze, though it veils the female figure, invites the viewer to uncover the hidden secret, fueling a voyeuristic desire to unravel the mystery. As Doane points out, “the question of whether the veil facilitates vision or blocks it can receive only a highly ambivalent answer, as the veil, in its translucence, both allows and disallows vision.”41Mary Ann Doane, Femmes Fatales: Feminism, Film Theory (New York: Routledge, 1991), 48.

Doane’s concept of the “second screen” is especially relevant to Farhādī’s cinema, where women are veiled behind walls or rendered through a mediated gaze. This visual strategy is tied to a buttressing strategy, where women are depicted as having a dangerous potential to be corrupted. As Doane states, “The veil incarnates contradictory desires –the desire to bring her closer and the desire to distance her. Its structure is clearly complicit with the tendency to specify the woman’s position in relation to knowledge as that of the enigma.”42Mary Ann Doane, Femmes Fatales: Feminism, Film Theory (New York: Routledge, 1991), 54. Farhādī’s women, similarly, remain veiled has a enigmas: knowable only through mediated, partial views.

Through the veiling of women’s visuality, which prompts the decoding of their secrets and the pursuit of truth, Farhādī’s films fail to disrupt the persistent association between femininity and unknowability. His female characters remain unrecognized, portrayed as too dangerous to be fully understood, and are consistently denied subjectivity. The veiled figure becomes one whose presence and demands—under the buttressing logic—lead to catastrophe or punishment. In acting as a “second surface,” the veil not only obscures the face, but it also undermines the depth of women’s motivations and agency.

Conclusion

This article expands the theorization of Iran’s neopatriarchal unconscious—a deeply rooted system that governs not only social conduct but also cinematic representation. Through the analysis of post-revolution Iranian films, particularly the works of Asghar Farhādī, it becomes evident that female characters are often framed through what I have termed buttressing strategies: visual and narrative techniques that manage women’s visibility, limit their mobility, and redirect their agency into symbolic or ambiguous forms.

Central to this dynamic is the concept of the buttressing gaze, introduced in this article as a critical tool for understanding how cinema visually reproduces patriarchal power. Unlike Mulvey’s classic male gaze, the buttressing gaze is defined by its logic of containment. It does not simply objectify women; it veils, displaces, and fragments their presence in order to preserve social order. Through this gaze, the neopatriarchal unconscious materializes on screen, shaping the aesthetic and narrative conditions under which women may appear, act, or disappear.

Such strategies operate across three primary cinematic functions: sartorial veiling, behavioral modesty, and sex-based spatial segregation. While these forms of representation may initially appear as products of ideological censorship, a deeper reading reveals their biopolitical dimension. As Kordela suggests in her theorization of biocinema, the cinematic gaze does not merely reflect life but regulates and constructs it through the production of potential bodies.43Kiarina Kordela, “The Gaze of Biocinema,” in European Film Theory, ed. Temenuga Trifonova (London: Routledge, 2009), 151–64. The Iranian female figure on screen becomes a managed potentiality—present but not fully materialized, empowered yet structurally contained.

The case analyses in this article demonstrate how these biopolitical operations are embedded in both the narrative logic and visual form of contemporary Iranian cinema. Farhādī’s films do not overtly transgress modesty codes, yet they reproduce the buttressing gaze by rendering female characters narratively absent, visually fragmented, or morally ambiguous. These cinematic gestures reflect the unconscious reproduction of power structures that seek to control femininity not by erasure, but by orchestration.

Ultimately, by conceptualizing the buttressing gaze as a biopolitical dispositif, I have offered a framework that connects the formal elements of cinema with broader regimes of gendered governance. Returning to the framing of the female body as a site of cultural, political, and moral struggle, particularly in the wake of the Women, Life, Freedom movement, this analysis shows how Iranian cinema participates in that same contest—through images, absences, and frames. The buttressing gaze thus not only interprets cinema’s response to censorship, but also reveals how cinematic form becomes a vehicle for negotiating the boundaries of female agency.

Bibliohraphy

Afary, Janet, and Kevin Anderson. “Woman, Life, Freedom: The Origins of the Uprising in Iran.” Dissent 70, no. 1 (2023): 82–98. https://dx.doi.org/10.1353/dss.2023.0032.

Althusser, Louis. “Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses: Notes Towards an Investigation.” In Lenin and Philosophy and Other Essays, edited by Louis Althusser, 127–86. New York: Monthly Review Press, 1971.

Britannica. “Buttress.” Accessed April 15, 2025. https://www.britannica.com/technology/buttress-architecture.

Doane, Mary Ann. Femmes Fatales: Feminism, Film Theory. New York: Routledge, 1991.

Foucault, Michel. Society Must Be Defended: Lectures at the Collège de France, 1975–76. Vol. 1. New York: Picador, 2003.

Ghorbankarimi, Maryam. “A Colourful Presence: An Analysis of the Evolution in the Representation of Women in Iranian Cinema since the 1990s.” PhD diss., University of Edinburgh, 2012.

Hassannia, Tina. Asghar Farhadi: Life and Cinema. New York: The Critical Press, 2014.

Khosrokhavar, Farhad. “Post-Revolutionary Iranian Youth: The Case of Qom and the New Culture of Ambivalence.” In Gender in Contemporary Iran: Pushing the Boundaries, edited by Roksana Bahramitash and Eric Hooglund, 99–120. New York and London: Routledge, 2011.

Khosrowjah, Hossein. “Neither a Victim nor a Crusading Heroine: Kiarostami’s Feminist Turn in 10.” Situations: Project of Radical Imagination 4, no. 1 (2011): 53–65.

Koo, Grace Yukich. “To Be Myself and Have My Stealthy Freedom: The Iranian Women’s Engagement with Social Media.” Revista de Estudios Internacionales Mediterráneos 21 (2016): 141–57. https://doi.org/10.15366/reim2016.21.011.

Kordela, Kiarina. “The Gaze of Biocinema.” In European Film Theory, edited by Temenuga Trifonova, 151–64. London: Routledge, 2009.

Mehryar, Sara, and Sara Sabet. “Socio-Spatial Segregation Dimensions in the City of Tehran: Measurement and Evaluation of Current Segregated Areas.” Paper presented at Urban Change in Iran, International Conference, University College London, November 8–9, 2012. https://www.academia.edu/3411397/Socio_Spatial_Segregation_Dimensions_in_the_city_of_Tehran

Merriam-Webster. “Buttress.” Accessed April 15, 2025. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/buttress.

Mottahedeh, Negar. “New Iranian Cinema: 1982–Present.” In Traditions in World Cinema, edited by R. B. Badley, 176–89. New Brunswick and New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 2006.

Mottahedeh, Negar. Representing the Unpresentable: Historical Images of National Reform from the Qajars to the Islamic Republic. New York: Syracuse University Press, 2008.

Mouri, Layla. “Gender Segregation Violates the Rights of Women in Iran.” Iran Human Rights Documentation Center. September 3, 2014. Accessed April 5, 2016. https://www.iranhumanrights.org/2014/09/gender-segregation/.

Mulvey, Laura. “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” In Issues in Feminist Film Criticism, edited by Patricia Erens, 28–40. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1990.

Naficy, Hamid. “The Averted Gaze in Iranian Postrevolutionary Cinema.” Public Culture 3, no. 2 (1991): 29–40.

Naficy, Hamid. “Iranian Cinema under the Islamic Republic.” In Images of Enchantment: Visual and Performing Art of the Middle East, edited by Sherifa Zuhur, 229–46. Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press, 1998.

Naficy, Hamid. “Islamizing Film Culture in Iran: A Post-Khatami Update.” In The New Iranian Cinema: Politics, Representation and Identity, edited by Richard Tapper, 26–65. London and New York: I.B. Tauris, 2002.

Naficy, Hamid. A Social History of Iranian Cinema: Volume 4. The Globalizing Era, 1984–2010. Durham: Duke University Press, 2012.

Nasehi, Elnaz. “The Question of Hijab and Freedom: A Feminist Critical Discourse Analysis of the Facebook Page My Stealthy Freedom.” In If You Wish Peace, Care for Justice, edited by Tuğrul İlter et. al. 15–24. Famagusta: Eastern Mediterranean University Press, Center of Research and Communication for Peace, 2017.

Nasehi, Elnaz. “Ambivalence of Hostility and Modification: Patriarchy’s Ideological Negotiation with Women, Modernity and Cinema in Iran.” International Journal of Advanced Research 8, no. 10 (2020): 542–52. https://doi.org/10.21474/IJAR01/11879.

Nasehi, Elnaz, and Nazlı Kara. “Buttressing Strategy: A Theory to Understand the Neopatriarchal Unconscious of Iranian Society/Cinema.” Revista de Cercetare si Interventie Sociala 60 (2018): 157–73.

Rizi, Nayereh Moradyan. “Iranian Women, Iranian Cinema: Negotiating with Ideology and Tradition.” Journal of Religion & Film 19, no. 1 (2015): 1–26.

Schimmel, Annemarie. “Qurrat Al-ʿAyn Ṭāhirah.” Encyclopedia of Religion. Accessed January 30, 2024. https://www.encyclopedia.com/environment/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/qurrat-al-ayn-tahirah.

Stewart, Melissa, and Uli Schultze. “Producing Solidarity in Social Media Activism: The Case of My Stealthy Freedom.” Information and Organization 29, no. 3 (2019): 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infoandorg.2019.04.003.

Zeydabadi-Nejad, Saeed. The Politics of Iranian Cinema: Films and Society in the Islamic Republic. New York: Routledge, 2010.

Cite this article

This article introduces the concept of the buttressing unconscious of Iranian cinema as a theoretical framework to understand how neopatriarchy inscribes itself into cinematic representation of women. Building on psychoanalytic film theory, feminist critique, and biopolitical discourse, this paper explores how post-revolutionary Iranian cinema—shaped by religious censorship and modesty codes—manages female visibility through a set of narrative and visual strategies. It argues that this process does not merely reflect ideology but operates as part of a biopolitical apparatus that governs which lives, bodies, and desires are allowed to materialize on screen.

Building on Kiarina Kordela’s concept of biocinema, the research demonstrates that these cinematic strategies operate not merely as reflections of ideology, but as biopolitical mechanisms that materialize gendered bodies as sites of governance. Through close readings of key films—particularly from the works of Asghar Farhādī—this article analyzes how unveiled/empowered female characters are represented through techniques of veiling, spatial segregation, and deferred narrative closure. These mechanisms, referred to here as buttressing strategies, contribute to a cinematic gaze that both acknowledges and neutralizes feminine potential.

By identifying three core cinematic functions of veiling and linking them to broader theoretical frameworks, the article offers a transferable model for analyzing gendered representation under ideological and biopolitical constraints. It thus contributes to feminist film theory and Middle Eastern media studies by bridging textual analysis and structural critique.1Parts of the theoretical framework discussed in this article are drawn from my doctoral dissertation, completed in 2018 at Eastern Mediterranean University, North Cyprus, under the supervision of Professor Nurten Kara. I am grateful for her invaluable guidance and mentorship throughout the development of that work.

Keywords: Iranian Cinema, Neopatriarchy, Buttressing Unconscious, Biocinema, Feminist Film Theory, Visibility, Veiling, Buttressing Gaze