Tehran in Iranian Post-Revolutionary Films

Introduction

Cities and urban spaces have always provided a leading geographical platform for cinematic narratives. Iranian cities are no exception. The city of Tehran, its neighborhoods, monuments, natural and artificial features, public places, and even interior spaces have been the location of most films in the history of Iranian cinema. Even though one can find movies set in Isfahan, Shiraz, Mashhad, Bushehr, Abadan, Kish Island, etc., when selecting an urban location, Tehran is still the filmmaker’s first choice. The number of academic writings and publications on the relationship between the city and Iranian cinema has been increasing in the past ten years.1Hamed Goharipour and G. Latifi, City and Cinema: An Analysis of Tehran’s Image in Iranian Narrative Cinema (Tehran: Negarestan-e Andisheh, 2018), City and Cinema in Iran, ed. Baharak Mahmoudi (Tehran: Elmi va Farhangi, 2021), Ahmad Talebinejad, Tehran in Iranian Cinema (Tehran, Iran: Rozaneh, 2012) However, an interpretation of the city in Iranian cinema based on urban theory is still scarce.

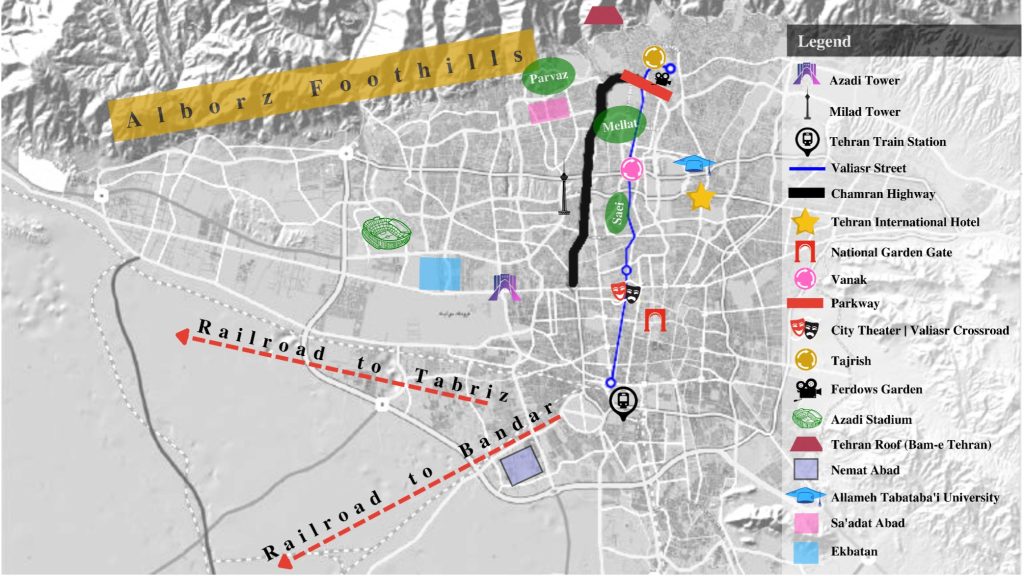

Kevin A. Lynch was an influential American urban planner. In the 1950s, he performed a five-year research project to study what elements constitute an observer’s mental map of a city. Lynch took Boston, Jersey City, and Los Angeles as case studies and conducted countless interviews with ordinary people to answer this question: What does the city’s form actually mean to the people who live there? Lynch concluded that people formed mental maps of their surroundings consisting of five basic elements: landmark, path, node, edge, and district. His work of urban theory, The Image of the City, has been one of the most distinguished writings on cities since its publication. This chapter uses Lynch’s approach of creating an image of the city as the theoretical basis to look into and interpret the cinematic representation of Tehran in Iranian post-Revolution feature films. Figure 1 illustrates the geographical location of urban elements discussed in the chapter.

Figure 1. The geographical location of urban elements (the size of icons does not correspond to actual elements)

Landmark

According to Lynch:

Landmarks, the point references considered to be external to the observer, are simple physical elements which may vary widely in scale. There seemed to be a tendency for those more familiar with a city to rely increasingly on systems of landmarks for their guides—to enjoy uniqueness and specialization, in place of the continuities used earlier.2Lynch, The Image of the City, 78.

Tehran is an approximately 700 km² metropolis, including 22 municipal wards and more than 110 neighborhoods. Each district, zone, or neighborhood has its own points of reference that signify Lynch’s definition of ‘landmark.’ From a telephone box to a tree, a statue, or a unique building, one can count an endless number of urban landmarks represented in Iranian cinema. However, the Azadi and Milad towers are well-known ‘urban-scale’ landmarks of Tehran that have repeatedly been featured in Iranian films, along with some more minor landmarks. Lynch argues that “spatial prominence can establish elements as landmarks in either of two ways: by making the element visible from many locations or by setting up a local contrast with nearby elements.”3Lynch, The Image of the City, 80. The Azadi and Milad towers meet both conditions.

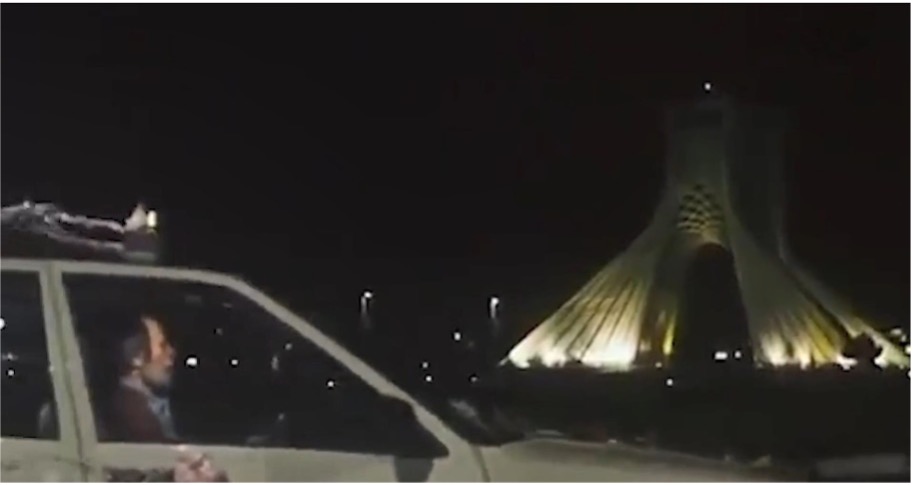

Azadi Tower, formerly known as Shahyad Tower, is a monument located at the center of the elliptical Azadi square that once was the westernmost point of Tehran. The construction of this monument was completed in 1971, about six years before the 1979 Revolution, when this urban space, which was once built and named as a literal monument to commemorate the 2,500th anniversary of the Iranian monarchy, played an iconic role in providing a context for protests and demonstrations.4Annelies van de Ven, “(De-)Revolutionising the Monuments of Iran,” Historic Environment 29, 3 (2017): 16-29; Khashayar Hemmati, A Monument of Destiny: Envisioning A Nation’s Past, Present, and Future Through Shahyad/Azadi (Thesis, Arts & Social Sciences, Department of History, Simon Fraser University, 2013) https://summit.sfu.ca/item/15619. While Azadi Tower has repeatedly been represented as the visual symbol of Iran in news items and reports, it in particular signifies an entrance gate to the capital city for most of the country’s population who live in the western provinces.

Canary Yellow (Zard-e Ghanari; dir. Rakhshan Banietemad, 1989) narrates Nasrullah’s journey to Tehran to pursue a fraud case, but his wife’s family scams cause him a lot of problems. Unlike in his small town, where social ties are substantial, Nasrullah cannot even trust his relatives in Tehran. The sequence of his arrival in Tehran is set in Azadi Square (Figure 2, left). The hustle and bustle, the passing of crowded minibuses and buses, and the boarding and disembarking of passengers all signal a new world. Similar to the role that the Statue of Liberty plays in demonstrating the entry point of America in several movies like The Legend of 1900 (dir. Giuseppe Tornatore, 1998), Azadi Square and Tower function as the landmark of Tehran. This tradition of depicting Azadi Tower as a gateway landmark has also been followed in other films. Redhat and Cousin (Kolah Ghermezi va Pesar Khaleh; dir. Iraj Tahmasb, 1995), a top Iranian movie by theatre attendance, narrates a puppet character migrating from his village to Tehran to work as a showman in a kid’s show. Azadi Tower is portrayed as a landmark for the inception of Kolah Ghermezi’s journey in Tehran (Figure 2, right).

Figure 2. Azadi Tower is the first point of reference for migrant in Canary Yellow (left) and Redhat & Cousin (right)

Still, no other film in Iranian cinema has emphasized the landmark function of Azadi Square and Tower as much as The Scent of Joseph’s Coat (Bu-yi pirahan-i Yusuf; dir. Ebrahim Hatamikia, 1995). Returning from Europe, Shirin meets Dayi Ghafur, an airport taxi driver, and the two go together searching for their missing-in-action loved one. Her first encounter with the city is depicted in Azadi Square, where she asks Dayi Ghafur to run around the square several times (Figure 3). Flitting/fluttering around something means worshipping and loving it in Iranian culture, like Muslims performing tavaf around the Kaʻbah during the Hajj. Beyond an urban-scale landmark, Azadi Tower represents the soil and the homeland in The Scent of Joseph’s Coat. It shines in the darkness of night and becomes a symbol of hope to find loved ones.

Lynch takes the Duomo of Florence as a prime example of a distant landmark and enumerates its features: “visible from near and far, by day or night; unmistakable; dominant by size and contour; closely related to the city’s traditions; coincident with the religious and transit center; paired with its campanile in such a way that the direction of view can be gauged from a distance.”5Lynch, The Image of the City, 82. The films discussed here represent all such features attributed to the Azadi Tower in a much larger city than Florence.

Figure 3. Azadi Tower is the landmark of Tehran, the soil and the homeland in The Scent of Joseph’s Coat

Milad Tower is the highest monument in Iran and one of the tallest structures in the world. Located in the mid-northwest of the city, the construction of this multi-purpose tower was completed in 2007 and immediately became the modern landmark and brand of Tehran.6Zahra Ahmadipour, Abdolvahab Khojamli, and Mohamadreza Pourjafar, “Geopolitical Analysis of Effective Factors on the Symbolization of Geographical Spaces of Tehran (Case Study: Symbolization of Milad Tower),” International Quarterly of Geopolitics 13, 46 (2017): 35-66, http://journal.iag.ir/article_55687.html; Mehrdad Karimi Moshaver, “Towers and Focal Points: The Role of Milad Tower in Urban Façade of Tehran.” Manzar (Journal of Landscape) 4, 20 (2012): 74-77; Mana Khoshkam and Mohammad Mahdi Mikaeili, “Brand Equity Model Implementation in the Milad Tower as a Tourist Destination.” Business Law, and Management (BLM2): International Conference on Advanced Marketing (ICAM4): An International Joint e-Conference-2021. Department of Marketing Management, Faculty of Commerce and Management Studies, University of Kelaniya, Sri Lanka, 2021, http://repository.kln.ac.lk/handle/123456789/23692. Accordingly, Milad Tower has been depicted as the point reference to demonstrate the geographical location of the subject(s) and the setting in several Iranian films and has seldom played the role of something more than a visual point of reference, which is the initial function of an urban landmark.

In Salve (Marham; dir. Alireza Davoudnejad, 2010), a grandmother rises from an old neighborhood to support her runaway granddaughter and finds her searching for drugs in Parvaz Park, at the northernmost point of the city. An extreme long shot of the dusty landscape of Tehran and Milad Tower, which, like a not-so-attractive structure, defines the upper border of the mise-en-scène, confronts the viewer with a city where a non-traditional young girl has no choices but to escape and become displaced. As a remnant of old Tehran, Grandmother looks at the new and vast but monster metropolis (Figure 4). Milad Tower represents the landmark of a gray and polluted-with-ugliness city. This scene is like a sequence in Mainline (Khun Bazi; dir. Rakhshan Banietemad and Mohsen Abdolvahab, 2006), where a mother is waiting while her drug-addict daughter Sara takes drugs. Similarly, construction sites and cranes in the background are confronted by a mother and daughter struggling in a modernizing Tehran.

Figure 4. Milad Tower is the landmark of a modernizing, ugly Tehran in Salve

In Oblivion Season (Fasl-i Faramushi-i Fariba; dir. Abbas Rafei, 2014), Milad Tower is depicted in the distant background of the mise-en-scène to characterize the setting and determine Fariba’s geographical and class distance from what is known as the symbol of modern Tehran (Figure 5, left). In contrast, Felicity Land (Saʻadat Abad; dir. Maziar Miri, 2011) narrates a gathering night of three upper-class couples in a well-known northern neighborhood of Tehran where the filmmaker, beyond local streets and stores, depicts Milad Tower to characterize the setting and economic class of the main characters (Figure 5, right).

Figure 5. Milad Tower is a geographical point of reference in Oblivion Season (left) and Felicity Land (right)

Subdued (Rag-i Khab; dir. Hamid Nematollah, 2017) refers to Milad Tower as the point of reference to characterize the urban setting of the disappointing love story of Mina, who needs financial and emotional support (Figure 6, left). I’m Not Angry! (Asabani Nistam!; dir. Reza Dormishian, 2014) depicts the joys and pastimes of Navid and Setareh in the middle of a mise-en-scène where Milad Tower forms the background (Figure 6, right). The fact that they are at the same level as the upper part of the Tower signifies the height of their dream, which eventually has a bitter end.

Figure 6. 6 Milad Tower is the background landmark of love stories in Subdued and I’m Not Angry!

However, in Wing Mirror (Ayneh Baghal; dir. Manouchehr Hadi, 2017), a high-grossing comedy, Milad Tower is portrayed as a place belonging to the rich class of society. An incredibly wealthy couple and the film’s two main characters go to Milad Tower due to several random events. The film represents a glamorous image of the Tower’s structures and interiors. “The activity associated with an element may also make it a landmark,”7Lynch, The Image of the City, 81. and these activities, according to Wing Mirror, do belong to the upper class. It is unlikely that a viewer from the lower strata of society who has never been to this place will find the Milad Tower, as depicted in this film, an inviting space.

As mentioned, the depiction of urban landmarks in Iranian films is not limited to the Azadi and Milad towers. While these two monuments play iconic roles in making people’s perception and mental image of Tehran, other landmarks have occasionally been portrayed in movies. The Iran-Iraq War was a protracted armed conflict that began on September 22, 1980 with the invasion of Iran by Iraq and lasted for approximately eight years. The War caused displacement and the migration of thousands of Iranians from southern and western provinces to big cities. Tehran was the main destination.8Ali Madanipour, “City Profile: Tehran,” Cities 16, 1 (1999): 57-65. Three years before Nasrullah’s migration to Tehran in Canary Yellow, The Kindness Territory (Harim-i Mehrvarzi; dir. Naser Gholamrezaei, 1986) had depicted a structure that was home to war victims, as well as the sign of the Iran-Iraq War in Tehran for a few years. Formerly known as Tehran International Hotel, this building not only becomes a visual and urban landmark in the film but also forms the narrative’s setting (Figure 7). Unlike Canary Yellow, there is no representation of Azadi Tower as a point reference of Tehran for migrants. The city’s landmark for them is a hotel that is now their dormitory, called Hejrat Residence, where they count the days to get rid of the capital city and return to their homeland. A few years after the War, The Abadanis (Abadani-Ha; dir. Kianoush Ayari, 1993) narrates another story about the War victims at the same place.

Figure 7. Tehran International Hotel is the sign of Iran-Iraq War in Tehran in The Kindness Territory

The National Garden’s Gate (Sardar-i Bagh-i Milli) is a structure left from the Qajar era, now one of the southern landmarks of Tehran. Although this Gate defined one of Tehran’s urban paths and was an urban-scale landmark for many years, it is only a visual point of reference today. A local landmark, according to Lynch, is “visible only in restricted localities,” and this is the role that Sardar-i Bagh-i Milli plays these days. The National Garden’s Gate is depicted in three scenes in Mother (Madar; dir. Ali Hatami, 1991). A mother returns from the nursing home to their old courtyard house to spend the last days of her life with her children, each of whom lives in a corner of the city. The film depicts the passage of three children through the National Garden’s Gate to Taranjabin Banu’s house in different scenes. The Gate signifies the return to old Tehran, family, and traditional values (Figure 8). Children who are either engaged in business or living in the modern spaces of the city find their past and roots as they pass through this Gate and arrive at the old house.

Figure 8. National Garden’s Gate is the landmark of old Tehran in Mother

As mentioned before, The National Garden’s Gate once defined one of the most central routes in Tehran. In today’s expanded and modernizing Tehran, however, other paths have replaced it.

Path

According to Lynch:

Paths are the channels along which the observer customarily, occasionally, or potentially moves. They may be streets, walkways, transit lines, canals, railroads. For many people, these are the predominant elements in their image. People observe the city while moving through it, and along these paths the other environmental elements are arranged and related.9Lynch, The Image of the City, 47.

In addition to unknown neighborhood networks and random local allies, highways and main arterial streets represent Tehran’s paths in cinema. With the increasing population of Tehran, the construction of several highways has been the primary strategy of Tehran’s urban management in recent decades, which, like similar experiences in the world, not only failed to solve the traffic problem but has also led to environmental, transportation and safety issues.10Ali Moradi, Hamid Soori, Amir Kavousi, Farshid Eshghabadi, Ensiyeh Jamshidi, and Salahdien Zeini. 2016. “Spatial Analysis to Identify High Risk Areas for Traffic Crashes Resulting in Death of Pedestrians in Tehran.” Medical Journal of the Islamic Republic of Iran (MJIRI) 30, 450 (2016): 1-10, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5307606/pdf/mjiri-30-450.pdf; S. Hosein Bahreini and Behnaz Aminzadeh, “Urban Design in Iran: A New Attitude,” Journal of Fine Arts [Honar-Ha-Ye-Ziba Memari-va-Shahrsazi] 26 (2006): 13-26. https://journals.ut.ac.ir/article_12317_60a4188dffe41dda029a85077e880426.pdf; Mehdi Arabi, “Tehran’s Traffic Flows; Capacity and Power of Crisis Production: The Case Study of Shahid Hemmat Highway,” Geography 13, 46 (2015): 271-300. www.sid.ir/FileServer/JF/40813944613.pdf. The cinematic image of these highways has not been sweeter and more optimistic than the findings of academic studies.

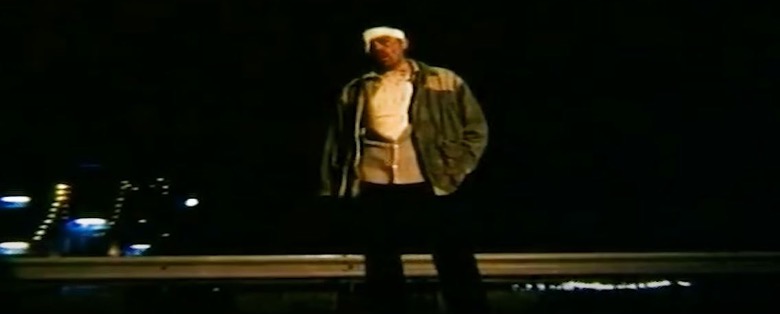

In ‘I’m Not Angry!’, Navid recounts all his complaints about his helplessness and the state of society while lying on the grass along the Chamran Highway, where no sound is louder than the passing of cars (Figure 9, right). He is a hardworking talented student who has been suspended from school for political reasons and can no longer arrange the necessary conditions for marriage with his lover. The highway’s roaring noise reflects all the annoying environmental conditions that Navid laments about. Similarly, Mina’s dream of emancipation at the beginning of Subdued leads to her struggle for “the right to the city,”11Henri Lefebvre, “The Right to the City,” in Writings on Cities, trans. Eleonore Kofman and Elizabeth Lebas (Oxford: Blackwell, 1996), 147-59. and, finally, leaves her placeless and helpless in the middle of the highway (Figure 9, left). In Mainline, the highways of Tehran and their bridges become the arena of Sara’s struggle to find drugs and her mother’s effort to convince Sara to go to their summer villa with her. Nights of Tehran (Shab-ha-yi Tehran; dir. Dariush Farhang, 2001), too, depicts Tehran’s highways as a slaughterhouse for Mina’s murderer.

Figure 9. The ruinous image of highways in Subdued (left) and I’m Not Angry (right)

However, no film has criticized the highway and high-rise constructions and modernization more furiously than Soltan (dir. Masoud Kimiai, 1996). Soltan’s friend randomly steals Maryam’s documents, including the title of an old house-garden in which she has a share. This causes Soltan and Maryam to meet, and Soltan helps her protect their property against other shareholders, jerry builders, and speculators.12Hamed Goharipour, “A Review of Urban Images of Tehran in the Iranian Post-revolution Cinema,” in Urban Change in Iran: Stories of Rooted Histories and Ever-accelerating Developments, eds. Fatemeh Farnaz Arefian and Seyed Hossein Iradj Moeini (Cham: Springer, 2016), 47-57. In an urban scene (Figure 10), Soltan stands in the middle of a highway, saying Here was our home. A courtyard house with five rooms, two small gardens, and a piscina at the center … When they decided to construct this highway, they purchased all those houses. We never could become homeowners again. Take good care of your home if they let you do so. Houses are being demolished, and better and more beautiful houses are being built in their place. But I don’t know why I fear these highways and towers. They make the world bigger. The city has become like paradise, but … And we hear the roaring noise of vehicles and see their annoying lights.

Figure 10. The destructive role and influence of highway as a path in Soltan (down)

The Girl in the Sneakers (Dukhtari Ba Kafsh-ha-yi Katani; dir. Rasoul Sadrameli, 1999) is an example of an Iranian street film. Originating in 1920s Germany, ‘street film’ refers to the importance in films of urban street scenes.13Encyclopaedia Britannica, “Street Film.” Accessed 06 28, 2022, www.britannica.com/art/street-film. While German movies were mostly filmed on studio sets, Italian Neorealist films14Mark Shiel, Italian Neorealism: Rebuilding the Cinematic City (New York: Wallflower Press, 2006), Ben Lawton, “Italian Neorealism: A Mirror Construction of Reality,” Film Criticism 3, 2 (1979): 8-23. and French New Wave cinema15Richard Neupert, A History of the French New Wave Cinema (Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press, 2002), Kristin Thompson and David Bordwell, Film History: An Introduction, 2nd ed. (New Yor: McGraw-Hill, 2002). used real streets to narrate the lives of ordinary people in the 1940s and 1960s, respectively. Tadai, the girl in the sneakers, is fed up with the pressures of her family and sees the city’s street as her refuge to get rid of these conditions. The story is reminiscent of François Truffaut’s The 400 Blows (Les quatre cents coups, 1959), where Antoine prefers urban sightseeing and playing in the city to the stress of school and home. Although the fate of none of them is promising, Tadai, unlike Antoine, does not feel free and happy in the city and cannot even fulfill her urban dream of walking on the Valiasr street curb from the south (the train station) to the north (Tajrish) (Figure 11). Mahparah, a gypsy woman, warns her that there is no safe place for a girl in this dirty city to spend a night! Valiasr and other streets of Tehran do not create a physical and mental environment for Tadai to relax and enjoy, so she eventually chooses to spend a night among slum dwellers. Similarly, Boutique (dir. Hamid Nematollah, 2003) depicts Eti’s fruitless wanderings in the streets of Tehran, during which the film condemns not only urbanites but also the city itself. One of the final shots only shows the frantic movement of the subway, which reflects the soulless machine life in the metropolis. However, years later, in the opening scene of Pig (Khuk; dir. Mani Haghighi, 2018), four high school girls enjoy walking down Valiasr St. as if the whole street is theirs, a generation that no longer lives in urban spaces but has drowned in the social media.

Figure 11. Streets of Tehran as brutal spaces in The Girl in the Sneakers

Valiasr Street, formerly known as Pahlavi Street, is the longest tree-lined street in Tehran which connects the central train station (Rah-Ahan) in south Tehran to Tajrish Square in the north. As a critical path in the spatial organization of Tehran, Valiasr’s narratives, form and functions, design, quality of life, cafés, etc., have been the topics of several studies and publications.16Valiasr Street of Tehran, ed. Kaveh Fooladinasab (Tehran: Sales, 2021); Naser Barakpour, Hamed Goharipour, and Mehdi Karimi, “The Evaluation of Municipality Performance Based on Citizen Satisfaction with Urban Public Services in the City of Tehran (Case Study: Districts 1 and 11),” Urban Management 8, 25 (2010): 203-218, www.sid.ir/FileServer/JF/28713892514.pdf; Hazhir Rasoulpour, Iraj Etesam, and Arsalan Tahmasebi, “Evaluation of the Effect of the Relationship between Building Form and Street on the Human Behavioral Patterns in the Urban Physical Spaces; Case Study: Valiasr Street, Tehran.” Armanshahr Architecture and Urban Development 13, 32 (2020): 113-130; Bahareh Motamed and Azadeh Bitaraf, “An Empirical Assessment of the Walking Environment in a Megacity: Case Study of Valiasr Street, Tehran,” International Journal of Architectural Research 10, 3 (2016): 76-99; Haniyeh Mortaz Hejri and Atoosa Modiri, “Evaluation of third place functions of cafes for the youth in Enghelab and Valiasr streets,” Journal of Arcitecture and Urban Planning 11, 22 (2019): 37-52. Its cinematic representation, however, signifies more of Lynch’s definition of a path: a channel along which the observer customarily, occasionally, or potentially moves. In Mother, we see Mohammad Ebrahim and his mentally ill brother, Gholamreza, driving to their mother’s house on Valiasr Street (Figure 12, left). This street is also depicted as an arterial path in the opening scene of The Tenants (Ejarah-Nishin-ha; dir. Dariush Mehriui, 1986). In Oblivion Season, Valiasr street is filmed only to show the route from the south to the north of Tehran, an area Fariba does not know; thus, Valiasr is barely a ‘path’ for her (Figure 12, right). Nevertheless, this long, historical, and diverse street has pause spaces and intersections that sometimes dominate its primary function as a path and become what Lynch calls ‘nodes.’ “Proximity to special features of the city,” Lynch argues could “endow a path with increased importance.”17Lynch, The Image of the City, 51. In the case of Valiasr street, proximity to urban-scale features like the main rail station, the City Theater, Parkway Bridge, and several roundabouts (Valiasr, Vanak, Tajrish, etc.) turns different sections of the street into nodes.

Figure 12. Valiasr St. is simply a path in The Tenants (left) and Oblivion Season (right)1

Node

According to Lynch:

Nodes are points, the strategic spots in a city into which an observer can enter, and which are the intensive foci to and from which he is traveling. They may be primarily junctions, places of a break in transportation, a crossing or convergence of paths, moments of shift from one structure to another. Or the nodes may be simply concentrations, which gain their importance from being the condensation of some use or physical character.18Lynch, The Image of the City, 47.

Tehran is a capital city with around nine million inhabitants within its limits and fifteen million residents in the metropolitan area. From neighborhood centers to cinema and theater halls, and from transits hubs to sporting venues, malls, and local markets, one can find hundreds of what is categorized as a node, according to Lynch’s conceptualization. Following the discussion about Valiasr St., a few nodes along this path have been represented in Iranian cinema. In Mercedes (dir. Masoud Kimiai, 1998), Yahya’s friends meet him performing a street show for dozens of people gathered in front of the City Theater (Figure 13, left), a cultural focal point on Valiasr Crossroad (Chahar-Rah-i Valiasr). While cars and buses pass by in the background, the City Theater creates a pause space and, like a heart, softens the flow of movement in the city. It is also the place where the characters get to know each other in Pink (Surati; dir. Fereydoun Jeyrani, 2003) and creates a knot in the story.19Mahsa Sheydani, “Footprints on the Street: Iranian Films and the Representation of the Valiasr Street Image,” Dalan Media, n.d. Accessed 07 01, 2022. www.dalan.media/Article/54. We see several shots of the interior and exterior of this node. The closing credits of Please Do Not Disturb (Lotfan Mozahem Nashavid; dir. Mohsen Abdolvahab, 2010) represent different shots of Valiasr Crossroad as a part of the whole of Tehran where accidental encounters change the life routine (Figure 13, right).

Figure 13. City Theater and Valiasr Crossroad are nodes in Mercedes (left) and Please Do Not Disturb (right)

Figure 14. Ferdows Garden is Tehran’s another cultural node in Hello Cinema

Ferdows Garden (Bagh Ferdows) is another recreational, cultural node along Valiasr street. Located in one of the northernmost neighborhoods of Tehran, this node not only hosts the Cinema Museum of Iran but has created a spatial context for filmmakers to deepen the characterization and inject a geographical structure into their movies. In preparation for producing his new film on the centenary of cinema, Mohsen Makhmalbaf publishes an advertisement in the newspapers and invites acting enthusiasts to gather at Bagh Ferdows. About five thousand people show up at the filming location on the promised day (Figure 14) and, without knowing, play roles in Hello Cinema (Salam Cinema; dir. Mohsen Makhmalbaf, 1995) and forever attach this urban space to Iranian cinema.

In Unruled Paper (Kaghaz-i Bi-Khat; dir. Naser Taghvai, 2002), Roya, a dreamy housewife, enrolls in a screenwriting class at Bagh Ferdows, where the atmosphere and her conversations with the teacher change her personal and marriage life (Figure 15). This public space becomes so much of a character in Bagh Ferdows, 5 PM (Bagh Ferdows, 5 Ba’d-az-Zohr; dir. Siamak Shayeghi, 2006) that it forms part of the movie’s title. Darya visits Bagh Ferdows on several occasions. Being in this place makes her feel relaxed and better. After a failed suicide attempt, she walks in Bagh Ferdows and reminisces with her late father.20Sheydani, “Footprints on the Street.” This place separates her from the city, the world, and everyday life to walk in her dreams. Bagh Ferdows becomes a node, not for collective activities but for returning to oneself.

Iran’s biggest urban node, where approximately 100,000 people can gather, is located west of Tehran. Azadi Stadium, formerly known as Aryamehr Stadium, was designed for the 1974 Asian Games and was inaugurated in 1971. It is still the largest football (soccer) arena by capacity in the Western Asia region. Even though Azadi stadium is the main venue for international games and is considered the home ground for two famous clubs, Persepolis FC and Esteghlal FC (formerly known as Taj), women have been banned from entering it since the Iranian Revolution in 1979. The discrimination against Iranian women’s right to this urban node has been the topic of several socio-political news items and academic writings.21Homa Hoodfar, “Kicking Back: The Sports Arena and Sexual Politics in Iran,” in Sexuality in Muslim Contexts: Restrictions and Resistance, ed. Anissa Hélie and Homa Hoodfar (New York: Zed Books, 2012), 208-33; Spyros Sofos and Nazanin Shahrokni, “Mobilizing Pity: Iranian Women on the Long Road to Azadi Stadium,” Jadaliyya. Arabic Studies Centre for Advanced Middle Eastern Studies MECW: The Middle East in the Contemporary World, Lund University, 2019. 10 23. Accessed 07 01, 2022, www.jadaliyya.com/Details/40131/Mobilizing-Pity-Iranian-Women-on-the-Long-Road-to-Azadi-Stadium. Women’s struggle to attend the stadium has not been left out of the eyes of Iranian cinema too.

Offside (dir. Jafar Panahi, 2006) tells the story of girls who bravely do anything to enter Azadi Stadium and watch Team Melli, the Iran national football team’s match. The film that has never been officially released in Iran depicts how six girls dressed as boys try to hide their gender identities in order to enter a gendered urban space (Figure 16). Offside is an Iran-ized cinematic representation of what Lefebvre calls “cry and demand,”22Lefebvre, “The Right to the City.” and Marcuse explains as below:

Figure 15. Ferdows Garden is an urban node and life’s turning point in Unruled Paper

“An exigent demand by those deprived of basic material and legal rights, and an aspiration for the future by those discontented with life as they see it around them and perceived as limiting their potential for growth and creativity…the demand is of those who are excluded, the aspiration is of those who are alienated; the cry is for the material necessities of life, the aspiration is for a broader right to what is necessary beyond the material to lead a satisfying life.”23Peter Marcuse, “From Critical Urban Theory to the Right to the City,” City: Analysis of Urban Change, Theory, Action 13, 2-3 (2009), 190.

Figure 16. Azadi Stadium is a gendered node in Offside

Although their struggle for the right to the city does not open the doors of the stadium, they are able to partially experience the taste of emancipation and pleasure in urban spaces at the end of the game, leaving Iranian women optimistic that their cry and demand would eventually help them appropriate spaces that they deserve to touch, feel, see, and experience.

Edge

According to Lynch:

Edges are the linear elements not used or considered as paths by the observer. They are the boundaries between two phases, linear breaks in continuity: shores, railroad cuts, edges of development, walls. They are lateral references rather than coordinate axes.24Lynch, The Image of the City, 47.

Several linear green spaces, highways, walls, etc., define the boundaries between neighborhoods, districts, and wards in Tehran. However, massive human-made and natural features shape the city’s edges on the metropolitan scale. The first 25-year Master Plan of Tehran, approved in 1966, suggested a linear extension of the city by defining new cultural, social, and residential centers or “urban towns” along its western-eastern corridor.25AbdolAziz Farmanfarmaian and Victor Gruen Associates, “Tehran Master Plan, Vols. 4 & 5.” (Tehran, 1968). Even though various plans, strategies, and projects have been prepared for and implemented in the city of Tehran in the past 50 years,26Ali Madanipour, Tehran: The Making of a Metropolis (Chichester: Wiley, 1998), and “Urban Planning and Development in Tehran,” Cities 23, 6 (2006): 433-438. the city’s spatial organization still reflects the influences of the old Master Plan. In fact, the natural barriers, namely the northern and northwestern mountains and the undeveloped southern desert, have limited the development directions of Tehran and defined the city’s edges. These edges, however, have not been immune from the consequences of the ever-increasing population growth and expansion of Tehran. This issue has been depicted in Iranian cinema from time to time.

In the 1980s, excessive population growth due to the Revolution and War caused many problems with regards to sufficient and affordable housing, and to the extent that the housing issue was no longer only related to immigrants. The unregulated housing market and constructions, uncontrolled city expansions, lack of community services and infrastructure, and mental problems caused by housing concerns were among the topics depicted in films. The Tenants shows what happened to the natural and historical edges and limits of Tehran in the ‘80s and how an unplanned horizontal expansion of the city caused irreversible issues. A shot shown in the film’s first sequence during the conversations between the municipal agent and the building’s tenants is a unique visual urban document (Figure 17). We see an extreme long shot of the northern mountains of Tehran and their foothills that, according to the agent, will soon be turned into a freeway. He optimistically explains that they have made good plans for here; This area has a promising future! Paradoxically, the following sequence shows breakdowns and instability inside one of the apartments. The Tenants narrates a comic and, simultaneously, a bitter image of the invasion of Tehran’s northern natural edge.

Figure 17. The invasion of Tehran’s natural edge in The Tenants

While these massive foothills are resisting urban development pressures, walking through their twists and turns, and watching the cityscape from their height is a breather for the captive city dwellers. Sitting on the top of Tehran’s Roof (Bam-i Tehran), the city’ highest spot, Amir Ali and Nooshin sanguinely talk about the results of their Lottery (dir. M. Hossein Mahdavian, 2018) application and sing about the future unaware that the metropolis has woven a different fate for them (Figure 18).

Figure 18. Tehran Roof (Bam-e Tehran) defines the city’s northern edge in Lottery

The Trans-Iranian Railway, completed in 1938, is Iran’s main railroad that links Tehran to Imam Khomeini Port (Bandar-i Imam Khomeini), formerly known as Bandar Shahpur, on the Persian Gulf in the south, and Torkaman Port (Bandar Torkaman), formerly known as Bandar Shah, on the Caspian Sea in the north of Iran.27Ervand Abrahamian, A History of Modern Iran (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008), Patrick Clawson, “Knitting Iran Together: The Land Transport Revolution, 1920–1940,” Iranian Studies 26, 3-4 (1993): 235-250. This system has more or less developed in the last eighty years. The system’s main station in Tehran is located at the southernmost point of Valiasr Street; therefore, the railroad lines coming out of it define an important section of Tehran’s southern edge. A few filmmakers have depicted this railway as a sign to visualize the geography of outsiders against the city’s residents.

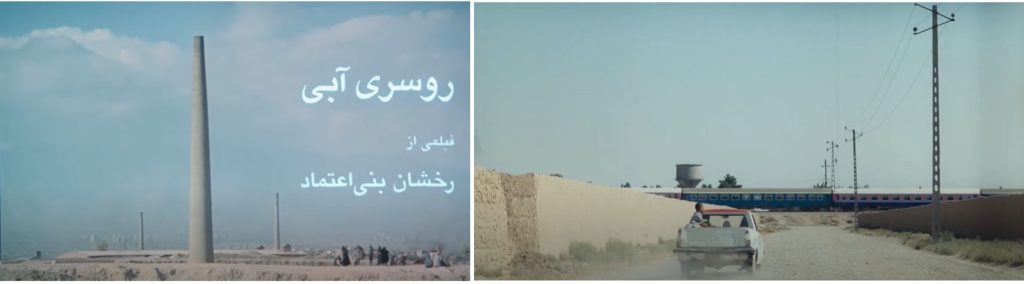

The Blue-Veiled (Rusari-Abi; dir. Rakhshan Banietemad, 1995) narrates the life of a community living and working in brick-making areas in the southern skirt of Tehran. The opening credits include a shot of the brick kilns, later revealed to be Nemat-Abad, while the city of Tehran can be seen in the distant background (Figure 19). The Blue-Veiled is perhaps one of the first popular films that features and is set in an impoverished neighborhood and its informal settlements. Determining the boundaries of this area by depicting the railway line and the movement of the train is the common point of The Blue-Veiled and Beautiful City (Shahr-i Ziba; dir. Asghar Farhadi, 2004). It is as if the train’s passing with its ear-splitting sound reminds the residents at every moment that the city has not yet accepted them.

Figure 19. Brick-making areas and a railroad define the southern edge of Tehran in The Blue-Veiled

Urban dwellers do not usually enter these marginalized areas. Otherwise, according to Firuzah, the main character of Beautiful City, they come to buy drugs. The contrast between the title and what is depicted in the film signifies Saussure’s Paradigmatic Semiotics in that the title involves signs that could replace what the city now is.28Ferdinand de Saussure, Course in General Linguistics, ed. Perry Meisel and Haun Saussy, trans. Wade Baskin (New York City: Columbia University Press, 1916/1959). The first shot of Firuzah’s home is from behind metal fences. The city seems to have expanded, but there is still no place for the marginalized. The fast movement of the train that passes in front of Firuzah’s small home tells of the continuation of life within the defined limits (Figure 20).

Figure 20 Railroad defines an edge and separates insiders from outsiders in Beautiful City

District

According to Lynch:

Districts are the medium-to-large sections of the city, conceived of as having two-dimensional extent, which the observer mentally enters ‘inside of,’ and which are recognizable as having some common, identifying character. Always identifiable from the inside, they are also used for exterior reference if visible from the outside.29Lynch, The Image of the City, 47.

One can divide a large city like Tehran into hundreds of districts based on geographical location, land use, economic and social characteristics, etc. Medium-to-large parks, for example, are among the districts used as filming locations. Saei Park becomes a romantic location for Javad and Maryam in Chrysanthemums (Gol-ha-yi Davoudi; dir. Rasoul Sadrameli, 1984) to meet, walk, and signal each other (Figure 21, left). In Being a Star (Setarah Ast; dir. Fereydoun Jeyrani, 2006), a park around Shoosh neighborhood in the south of Tehran is a real-world location for a filmmaking group to document drug dealing and drug use. Millat Park is where twin Strange Sisters (Khaharan-i Gharib; dir. Kiumars Pourahmad, 1996) meet each other and make a game-changing decision that eventually helps them become a family again (Figure 21, right). Parks in Iranian cinema are places for strangers to meet and get to know each other.

Figure 21. Parks are districts to meet strangers in Chrysanthemums (left) and Strange Sisters (right)

University campuses are educational districts in Tehran that, in contrast to similar spaces in many countries, are usually surrounded by walls and other barriers; therefore, non-affiliated people are not allowed to enter them. A review of the history of Iranian cinema shows a direct relationship between the popularity of the representation of colleges and campus lives and concerns in films and the national political climate. The inceptions of Iran’s ‘reform era,’ when Mohammad Khatami was elected as the president of Iran in 1997, opened a new space for making films about the concerns of college students and the new generation. Protest (Eteraz; dir. Masoud Kimiai, 2000) and Born Under Libra (Motivalid-i Mah-i Mehr; dir. Ahmadreza Darvish, 2001) were popular movies made in the early 2000s, surprisingly using the same cinematic couple, reflecting on the reformist sociocultural transformations of Iranian society and their challenges from different perspectives. Set in the Allameh Tabataba’i University’s College of Social Sciences campus, Born Under Libra begins with the confrontation of groups of students over the gender segregation policy in classes and educational spaces (Figure 22, left). Not surprisingly, about a decade later, this university was the first higher-education institute to actually implement this policy in the post-Khatami era.30Ali Entezari, “Effects and Implications of Gender segregation in Allameh Tabataba’i University Compared to Other Universities,” Quarterly Journal of Social Sciences 81 (2018): 211-246; Zahra Kamal, “Gender Separation and Academic Achievement in Higher Education: Evidence from a Natural Experiment in Iran,” BERG Working Paper Series 171 (Bamberg University, Bamberg Economic Research Group, 2021). http://hdl.handle.net/10419/242824; Nazanin Shahrokni, “Protecting Men and the State: Gender Segregation in Iranian Universities,” in Women, Islam, and Education in Iran, ed. Goli M. Rezai-Rashti, Golnar Mehran, and Shirin Abdmolaei (New York: Routledge, 2019), 84-102. Nights of Tehran (2001), a psychological crime thriller, takes a college campus as a context to inject a feminist social justice look into the patriarchal atmosphere of society. Influenced by the Green Movement of Iran that arose after the 2009 Iranian presidential election, I’m Not Angry! (2014) narrates the dreams and disappointments of a suspended college student and extends student union issues to a broader economic and structural shortcoming in the country (Figure 22, right). Inspired, therefore, by sociopolitical changes, Iranian cinema has taken college campuses as avant-garde platforms and vibrant urban districts to critically reflect on the “cry and demand”31Lefebvre, “The Right to the City.” of a new generation.

Figure 22. College campuses as vibrant urban districts in Born Under Libra (left) and I’m Not Angry! (right)

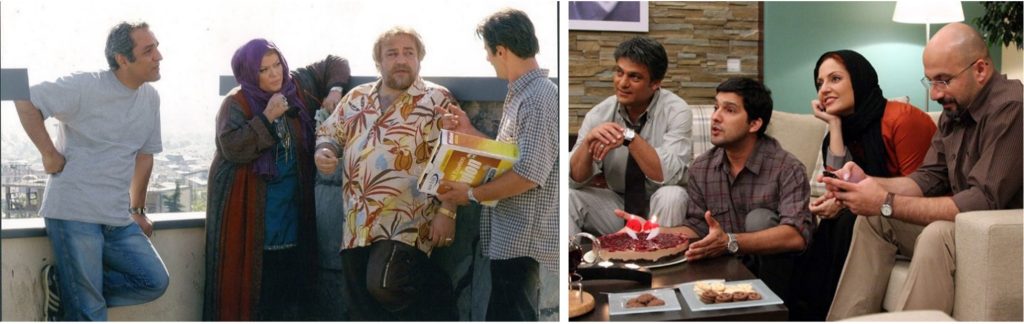

A residential neighborhood is also a large district, mainly when its people belong to a unique socio-cultural and economic class. For example, as mentioned above, Felicity Land (Saʻadat Abad) refers to a newly developed district of Tehran where the upper-middle-class lives and the film challenges their lifestyle, relationships, and emerging issues (Figure 23, right). The problems of pseudo-modern life of the uptown dwellers can also be seen in Tambourine (Dayerah-i Zangi; dir. Parisa Bakhtavar, 2008), where disputes between building residents, the lack of apartment-living ethics, paradoxes between neighbors’ priorities, etc. are issues they are struggling with (Figure 23, lest). The film criticizes their utilitarian behavior and unethical decisions.

Figure 23. Tehran’s northern districts and their people, conflicts, and challenges in Tambourine (left) and Felicity Land (right)

On the other hand, many movies have portrayed the challenges and beauties of life in the southern districts of Tehran. Contrary to Tambourine, Mum’s Guest (Mahman-i Maman; dir. Dariush Mehrjui, 2004) narrates the collaborative works of neighbors in a central courtyard house; a semi-private space that is lost in today’s architecture and urban design and is taking its last breaths in some southern neighborhoods of Tehran,32Hamed Goharipour, “Narratives of a Lost Space: A Semiotic Analysis of Central Courtyards in Iranian Cinema,” Frontiers of Architectural Research 8, 2 (2019): 164-174. where ‘mother’ still plays a central role in providing a comfortable environment for the family (Figure 24, left). Café Setarah (dir. Saman Moghadam, 2006) tells the story of three women in one of the old neighborhoods of Tehran. The film creatively connects the spirit of living in an old neighborhood with its physical features. Old houses’ windows open toward each other. Alleys are portrayed under lightning in the winter, where one hears dogs barking. Following the style of film noir, a café owned by a woman is the location of meetings and story encounters. The café, an auto repair shop, an Imamzadah, old houses, and, of course, the neighborhood’s people make up the story’s atmosphere. Poverty and unemployment are the most critical issues that disrupt the normal life of the residents and make them involved in crime. Life and a Day (Abad va Yek Ruz; dir. Saeed Roustayi, 2016) portrays the bitterness and provides the audience of cinema with an acclaimed story of a family who lives in an old neighborhood where poverty, drug addiction, and violence are key characteristics (Figure 24, right). Still, a woman is at the center of the family whose decision determines the death and life of her relatives.

Figure 24. Tehran’s southern districts and their people, inspirations, and issues in Mum’s Guest (left) and Life and a Day (right)

“The physical characteristics that determine districts are thematic continuities which may consist of an endless variety of components: texture, space, form, detail, symbol, building type, use, activity, inhabitants, degree of maintenance, topography.”33Lynch, The Image of the City, 67. Thematic continuities of Ekbatan make it an eligible Lynchian district in Tehran. This modern apartment building complex is a semi-gated planned community located in Municipal Ward 21 in the west of Tehran.34Mohamad Sedighi, “Megastructure Reloaded: A New Technocratic Approach to Housing Development in Ekbatan, Tehran,” ARENA Journal of Architectural Research 3,1 (2018): 1-23. doi:https://doi.org/10.5334/ajar.56. Designed by an American architecture firm, Ekbatan (Shahrak-i Ekbatan) was one of the first mass housing projects in Iran, which was built and completed in the 1970s. Contrary to the reputation of this district due to its architecture, mixed-use design, and safety, the cinema of Iran has not represented it as an inviting and desirable area. In Nights of Tehran, Shirin’s fears are depicted in connection with the environmental characteristics of Ekbatan and contextualized in the spatial atmosphere of this district. The reflection of the shadows on the white walls at night and her movement between the rectangular pillars of the buildings that resemble an enclosed labyrinth are accompanied by eerie music and this creates a cinematic spatial experience of Ekbatan that is not at all attractive (Figure 25, left). In another dark representation of the district in a movie titled Ekbatan (dir. Mehrshad Karkhani, 2012 ), living within the high walls of this modern complex is not the peaceful life that Alborz is looking for after getting out of prison. 13 (dir. Houman Seyyedi, 2014), too, portrays an Ekbatan that is more like the geography of Martin Scorsese’s New York gangster movies. A teenager gets involved in a street gang to escape family disputes, loneliness, and despair (Figure 25, right). This takes him out of the apartment and into Ekbatan, where there are no signs of a normal life, safety, beauty, and hope.

Figure 25. The dark, uninviting image of Ekbatan in Noghts of Tehran (left) and 13 (right)

Conclusion

A theory-based interpretation of the city in Iranian cinema is not limited to one urban theory. One can explain transformations of the city and people’s lives by using Georg Simmel’s The Metropolis and Mental Life35Georg Simmel, “The Metropolis and Mental Life,” in The Sociology of Georg Simmel, ed. Kurt H. Wolff (New York: The Free Press, 1950), 409-24. or by critically reflecting on them through a Lefebvrian Right to the City perspective. One might employ Jacobs’ urban theory36Jane Jacobs, The Death and Life of Great American Cities (New York: Random House, 1961). or focus on the theoretical thoughts around elements and topics such as trees, transportation, housing, etc. This chapter opens up an urban theory-based discussion of Iranian cinema by reviewing a limited number of films. Accordingly, one can name many other Iranian movies portraying a landmark, path, node, edge, or district.

Moreover, some films depict and mention Tehran in the big picture, not in details and its elements.37Parviz Ejlali and Hamed Goharipour, “Depicting The ‘City’ In Iranian Films: 1930-2011.” Social Sciences 68 (2015): 229-278. Looking at Tehran from their new place, Emad in The Salesman (Furushandah; dir. Asghar Farhadi, 2016) says, what are they doing with this city? I wish I could bring a loader and ruin all of it. Inversion (Varunigi; dir. Behnam Behzadi, 2016) refers to Tehran as ‘Smoky City.’ Retribution (Kiyfar; Hassan Fathi, 2010) takes the audience to unknown, scary, and underground places of Tehran. Under the Skin of the City (Zir-i Pust-i Shahr; dir. Rakhshan Banietemad, 2001) narrates the sufferings of a low-income family in the south of Tehran. From Travelers of Moonlight (Musafiran-i Mahtab; dir. Mehdi Fakhimzadeh, 1988) to Trapped (Darband; dir. Parviz Shahbazi, 2013), Iranian films have dramatized the plight of immigrants who were either swallowed up in the jungle of the metropolis or were forced to return to their homeland. Among the new generation of filmmakers, Just 6.5 (Metri Shish va Nim; dir. Saeed Roustayi, 2019), Sheeple (Maghz-ha-yi Kuchak-i Zang Zadah; dir. Houman Seyyedi, 2018), and Drown (Shina-yi Parvanah; dir. Mohammad Kart, 2020) reveal places and criminal activities in and around Tehran that one would not become aware of unless trough cinema. The image one gets of Tehran from all these films would be in conversation with how Lynch described his research findings. “Rather than a single comprehensive image for the entire environment, there seemed to be sets of images, which more or less overlapped and interrelated.”38Lynch, The Image of the City, 85. Just as cities, like texts, are written and read by millions of people, their cinematic images must be interpreted and reread by different researchers.

Cite this article

This article explores the cinematic representation of Tehran in Iranian post-revolutionary films, analyzing the city as both a physical space and a cultural symbol through Kevin Lynch’s concept of urban imagery. The study examines how landmarks such as Azadi Tower and Valiasr Street, alongside the city’s edges, nodes, and districts, are used to reflect social, political, and cultural shifts since the revolution. Films like Canary Yellow, The Scent of Joseph’s Coat, and Offside highlight themes of alienation, modernity, displacement, and community. By interpreting the evolving urban landscape as a narrative tool, this article positions Tehran as a dynamic character that embodies the transformations in Iranian society.