The Cycle of Violence as a Path to Justice in the Film Bī hamah chīz

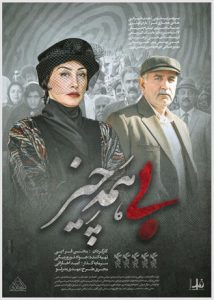

Figure 1: Poster of the film Bī hamah chīz, directed by Muhsin Qarā’ī, 2021.

Introduction

Violence has consistently served as one of humanity’s primordial responses to the challenges of engaging with the external world. Violence is a key part of human existence, shaping history and playing a major role in human development throughout time. The origin of all forms of violence is anthropogenic. Throughout history, humans have repeatedly turned to violence in their pursuit of what they see as the highest state of human existence. Violence has traditionally been viewed negatively and condemned in cultural discussions. Given the ever-evolving nature of global conditions, various motivations for vengeance and violence have historically emerged among human beings. Acts of vengeance and violence are shaped by the time, place, and prevailing beliefs of each era, influencing how individuals perceive their responsibilities within social and political contexts. It is possible that, in certain instances, violence may be used as a means of pursuing justice; consequently, in today’s world, not all acts of violence are categorically criticized or condemned as inherently reprehensible. However, thinkers, such as Slavoj Žižek, have strongly criticized the ideological legitimization of violence, arguing that such narratives allow individuals to excuse violent actions under the pretense of pursuing justice—even when such violence does not establish or uphold the law. 1Slavoj Žižek, Violence: Six Sideways Reflections (New York: Picador, 2008), 1–3.

Violence can manifest in various forms, whether overt or covert, and can occur through different means, such as verbal, emotional, or physical methods. All humans inevitably experience violence, whether personal or societal, as a threat or a form of power, ranging from symbolic violence to murder and conflict. People react to violence in different ways, but a common response is ignoring their own needs to prioritize other concerns in violent situations.

For numerous philosophers, ranging from Plato and Spinoza to Freud, Nietzsche, Wittgenstein, Derrida, Levinas, and Aron, violence is regarded as an inseparable aspect of human existence. Numerous works have been dedicated to the study of violence, with some thinkers arguing that revolutionary violence represents its highest form. They argue that this form of violence is not an impulsive reaction to a threat, but rather a calculated, strategic response.2For an examination of Philosophical perspectives on violence, see Richard Bernstein, Violence: Thinking Without Banisters (Cambridge: Polity, 2013), chap. 4, 90-130; James Dodd, Violence and Phenomenology (London: Routledge, 2009), chap. 3 & 4, 120-180; Wolfgang Sofsky, Violence: Terrorism, Genocide, War (London: Granta, 2003), 45-70; Slavoj Žižek, Violence: Six Sideways Reflections (New York: Picador, 2008), 30-60; Friedrich Nietzsche, On the Genealogy of Morals, trans. Walter Kaufmann (New York: Vintage, 1989), Essay II, §§ 11-12, 65-70; Raymond Aron, Peace and War: A Theory of International Relations (New York: Doubleday, 1966), 150-160; Emmanuel Levinas, Totality an Infinity, trans. Alphonso Lingis (Pittsburgh: Duquesne University Press, 1969), 21-30; Jacques Derrida, Of Grammatology, trans. Gayatri Spivak (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997), 112-120; Ludwig Wittgenstein, Philosophical Investigations, trans. G. E. M. Anscombe (Oxford: Blackwell, 2001), §19 & § 23; Sigmund Freud, Civilization and Its Discontents, trans. James Strachey (New York: Norton, 2010), 58-65; Walter Burkert, Greek Religion (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1985), 62-65; Edwin Curley, Ethics (London: Penguin, 1996), 155-160; Frantz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth (New York: Grove Press, 2004), 50. Michel Foucault views violence as an inherent aspect of human existence, embedded within mechanisms of control; Mario Vargas Llosa regards violence as a tool for extending power; and Manes Sperber interprets the rise of tyranny as a product of specific social conditions.3Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, trans. Alan Sheridan (New York: Vintage Books, 1995), 195-210; Mario Vargas LIosa, The Time of the Hero, trans. Lysander Kemp (New York: Grove Press, 1966), 120-150; Manes Sperber, The Psychology of Power, trans. Joachim Neugroschel (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1988), 50-70. Karl Popper argues that violence suppresses both individual and social freedoms, and that in an open society, reforms should be implemented through dialogue, with the ultimate goal being the achievement of justice.4Karl Popper, The Open Society and Its Enemies: Volume 1: The Spell of Plato. 5th ed. (London: Routledge, 1966), 157-158. Hannah Arendt argues that “violence can be justifiable, but it never will be legitimate.”5Hannah Arendt, On Violence (New York: Harcourt, 1970), 52. Niccolò Machiavelli views violence as a necessary tool for political change, particularly in establishing or maintaining power, while Jean-Paul Sartre, in his existentialist philosophy, identifies the “Other” as a source of alienation—a notion that underpins the justification of revolutionary violence.6Niccolò Machiavelli, The Prince, trans. Harvey C. Mansfield, 2nd ed. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998), 66-70; Jean-Paul Sartre, Being and Nothingness, trans. Hazel E. Barnes (New York: Washington Square Press, 1992), 340-345. Philosophical discourse on violence often leads to its rejection rather than its endorsement.

Violence plays a significant role in representing societal realities, consistently serving as a dramatic and striking element in Iranian cinema, often depicted through social, familial, and political conflicts. The portrayal of violence in Iranian cinema reflects the realities of Iranian society and serves as a lens through which certain aspects of it can be analyzed. In pre-revolutionary cinema of the 1960s and 1970s, violence was primarily physical, often used to attract audiences and create excitement, such as in street fights. In post-revolutionary cinema, shaped by various developments, violence was more commonly depicted through political, religious, social, and class conflicts. In recent decades, Iranian cinema has moved toward a more realistic representation of violence; therefore, violence is not necessarily physical but sometimes manifests in the internal and external conflicts of characters, or as psychological and emotional violence within familial and social relationships. In Iranian cinema, violence is sometimes used to critique social and political issues, while at other times, it highlights deeper struggles related to morals, culture, and identity within society.

The element of violence in the film Bī hamah chīz (Without Anything, 2021) manifests as a deep-seated revenge disguised as justice. Justice is defined as equality, fairness, and the just distribution of resources and opportunities in a society. As one of the fundamental concepts in philosophy and psychology, Justice has always been discussed and examined as a moral and social principle. Philosophers such as John Rawls, Friedrich Nietzsche, and Plato have offered various interpretations of justice. Plato defines it as harmony between society’s classes, where each person fulfills their rightful role and duties.7John Rawls, A Theory of Justice, rev. ed. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1999), 10-15; Friedrich Nietzsche, On the Genealogy of Morality, trans. Maudemarie Clark and Alan J. Swensen (Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing, 1998), 65-70; Plato, The Republic, trans. Allan Bloom, 2nd ed. (New York: Basic Books, 1991), 433a-435b. This concept plays a crucial role not only in political and social spheres but also in individual life and interpersonal relationships. When neglected, it can result in negative emotional states, including anger, dissatisfaction, despair, and anxiety.

From a psychological standpoint, justice is regarded as one of the fundamental human needs. Humans possess an inherent inclination towards equality and fairness because injustice has the potential to undermine the sense of security within society and foster psychological distress. Social psychologists, such as Melvin Lerner, with his “Just-World Hypothesis,” have demonstrated that individuals tend to believe in the inherent justice of the world, assuming that people receive what they deserve.8Melvin J. Lerner, The Belief in a Just World: A Fundamental Delusion (Springer, 1980), 34-60. This belief gives individuals a sense of control over their lives. As a result, justice is not only a social construct but also a vital psychological necessity, both on an individual and collective level. John Locke argued that the role of justice is to protect fundamental natural rights, including life, liberty, and property.9Steven Forde, “John Locke and the Natural Law and Natural Rights Tradition,” National Leadership Resource and Curriculum, accessed May 27, 2025, https://www.nlnrac.org/earlymodern/locke.html. In today’s societies, achieving justice requires continuous efforts in legal reform, reducing discrimination, and raising public awareness. Justice is integral not only to societal stability and progress but also to the establishment of peaceful coexistence and the fulfillment of human rights.

The film Bī hamah chīz (2021), directed by Muhsin Qarā’ī and loosely based on Friedrich Dürrenmatt’s play Der Besuch der alten Dame (The Visit), is set in a rural context. The film examines whether violence in the form of revenge can serve as an ethical response and a means of achieving justice, or if it is inherently incompatible with justice. In other words, can violence serve as an appropriate means of achieving justice? Does Līlī, the female protagonist, achieve justice through revenge, or does she become a symbol of a new injustice?

Figure 2: Amīr Khan, standing on the execution platform, tells Ahad—a young boy who raised his hand in protest against Amīr Khan’s execution—that he is content with his death. Still from the film Bī hamah chīz, directed by Muhsin Qarā’ī, 2021. Accessed via https://youtu.be/wxFcJ8eXVho?si=l3v-DzgfRTnoWeSi (01:50:11).

By raising questions about the legitimacy of violence and whether it can be seen as a just or morally right act, the film prompts the audience to reflect on these concepts. The audience will then examine the concept of justice through the lens of violence. This article will analyze the film Bī hamah chīz through the lens of one of the most significant concepts—violence—using an interdisciplinary approach and drawing on a combination of philosophical and sociological theories.

Film Synopsis

In a village before the 1979 Revolution, under the feudal system and long trapped in poverty, losing its former prosperity, a landowner, named Amīr Khan, worked as the local judge and head of the local House of Justice. Because of his good reputation, the people trusted him completely and, in a way, were indebted to him, with many of the village’s important tasks falling under his responsibility. Together with his wife Nasrīn, he ran a grocery store. His daughter Āsiyah was a schoolteacher and was in love with Mr. Sultānī, another teacher at the school.

One of the villagers, named Līlī, who had been driven out of the village years ago because of an accusation of prostitution, returns as a wealthy woman. At the request of the village headman, she arrives back to the village. Believing that she has come to save them from their misfortune, the villagers place their hopes on her. Upon her arrival, Līlī was warmly greeted by the villagers. To exact revenge on Amīr Khan, the man she once loved, she assures the villagers that, in exchange for Amīr Khan’s death, she promises the villagers a big fortune, locust-free fields, and the reopening of the ancient mine. It doesn’t take long for the villagers’ attitude toward Amīr to change. Līlī’s tempting offer stirs their greed, and they turn against him. Aware of Līlī’s intentions, Amīr initially denies everything and tries to warn the villagers about the plot. In the meantime, horrifying secrets from both Līlī’s and Amīr’s pasts are revealed, completely altering the fate of both the villagers and themselves.

Figure 3: Līlī arrives at the train station amidst the villagers’ celebrations, invited to resolve the village’s problems. Still from Bī hamah chīz, directed by Muhsin Qarā’ī, 2021. Accessed via https://youtu.be/wxFcJ8eXVho?si=l3v-DzgfRTnoWeSi (00:17:38).

A young man named Farrukh, who is with Līlī, turns out to be her and Amīr’s illegitimate son, unaware that Līlī is his real mother. Years ago, Amīr had denied responsibility for Līlī’s pregnancy and, following the Khan’s orders—who was a figure of traditional authority—he married the village chief’s daughter. The villagers are now seeking help from someone they had expelled years ago for being pregnant with Amīr’s illegitimate son. Now that she has become very wealthy, the village headman writes a letter, forging Amīr’s signature, allowing her to return and save her hometown from its miseries. Now, Līlī represents the upper class—a wealthy and educated woman who was once oppressed by the lower class. She uses her wealth as a tool for violence, revenge, and the reclamation of her repressed rights. Within three days, the famished villagers who had earlier sworn allegiance to Amīr Khan would consent to his murder in return for cash and assistance, defending their acts as the application of justice that had been denied.

However, the villagers do not act spontaneously. The village leaders, including the headman, the district officer Ustuvār Dashtakī, Dr. Adhamī, and even Qāsim, Amīr’s brother, who owes him his life after a mining accident, each encourage the villagers to kill Amīr for their own personal benefits. Līlī intends to settle scores not only with Amīr but with the entire village, making them all complicit in his bloodshed. The villagers, in turn, believe that by carrying out this so-called justice, they can rebuild their ancestral village.

As the film progresses to the scene of Amīr’s execution, all the villagers, except for a disabled boy named Ahad, support the execution. Meanwhile, Āsiyah leaves her hometown forever, taking a train, and Mr. Sultānī, who has been driven away by the villagers, remains in his classroom. In this scene, the village headman gathers the people to sign an execution warrant to avoid any future controversy, asking everyone to sign it. After the villagers sign the warrant, Amīr is led to the gallows, passing among those who signed it, their tears falling as he walks towards his fate. However, when Līlī’s car arrives at the execution scene, the villagers cheer for her arrival. This implies that they are not ignorant, but rather choose to act in this manner deliberately and selfishly. In the end, the only person who wants to spare Amīr’s life is Līlī. She orders Amīr to be taken down from the gallows, but Amīr appears to be at peace with himself as he quietly knocks the stool off under his feet and ends his life. This is where Sophocles ironically says: “Count no man happy till he dies, free of pain at last.”10Sophocles, Oedipus The King, trans. Robert Fagles (London: Allen Lane, 1982), 327.

Figure 4: From the gallows, Amīr Khan casts a final glance at Līlī, who is leaving the village by car. Still from Bī hamah chīz, directed by Muhsin Qarā’ī, 2021. Accessed via https://youtu.be/wxFcJ8eXVho?si=l3v-DzgfRTnoWeSi (01:54:27).

The Nature of Violence

Violence, in its diverse manifestations, is depicted in this film in a starkly realistic and grim way, emerging both overtly and covertly through various forms—verbal, psychological, and physical—carried out by different agents. This kind of violence degrades the human side of the film characters; personal revenge turns into collective punishment, showing how quickly violence can spread through society.

The film opens with a scene in a barn housing a black cow, while a grasshopper perches on the barn window. The cow, which has a newborn calf, is slaughtered that very day—just like the fate awaiting Amīr Khan. The image of the cow is shown from a high angle shot, which makes the subject appear increasingly weak and vulnerable. Apparently, for several years, the village’s fields have been plagued by locusts, which have ravaged all the crops.

Figure 5: Villagers fight locusts destroying their crops as Amīr Khan arrives to protest against Līlī with the village head. Still from the film Bī hamah chīz, directed by Muhsin Qarā’ī, 2021. Accessed via https://youtu.be/wxFcJ8eXVho?si=l3v-DzgfRTnoWeSi (00:43:48).

In this film, the locusts symbolize the relentless collective violence and the destructive, indifferent, and complacent behavior of a morally weak community. Without considering the consequences of their actions, this community makes irreversible decisions based solely on short-term interests, resulting in social violence. These locusts serve a similar function to the flies in Jean-Paul Sartre’s play The Flies (Les Mouches) in the city of Argos, symbolizing the pervasive guilt and torment of the people who must atone for their past sins. In the film, the remote village can be seen as a symbol of Iranian society, grappling with economic hardship, corruption, and injustice, where moral values are shaken, and public trust has diminished. According to political philosopher John Elster, a crisis-ridden society easily gravitates towards violence because its members seek a quick fix to restore balance, thus leading to the weakening of collective ethics.11Jon Elster, The Cement of Society: A Study of Social Order (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989), 123-125.

In the film Bī hamah chīz, it appears that Amīr Khan, the village’s Nietzschean Übermensch, was the first to have committed violence against Līlī years ago. Fearing the wrath of the Khan, he gave up the possibility of living with Līlī and their unborn child. By refusing to admit he was the father, he is responsible for her expulsion from the village and the profound emotional harm she endured. This injustice—caused by the Khan and his nephew Amīr—led the villagers to treat Līlī violently and drive her out. In this way, violence grows out of rebellion and injustice.

At first, the audience perceives Līlī’s revenge as a rightful claim, seeing her as Nemesis—the goddess of retribution and vengeance—returning to her hometown. After being kicked out of her village because of Amīr’s betrayal, she became rich and famous and seems justified in getting revenge on those who hurt her. Yet, the film skillfully shifts the viewer’s perception of revenge and justice away from lawful frameworks and instead insists on their assertion through violence.

In the scene of Amīr Khan’s execution, the village headman asks if anyone doubts his guilt. When no one responds, he urges those who signed the execution warrant to raise their ink-stained fingers. Here, poverty and famine fuel the people’s violence, compelling them to raise their inked fingers and, despite tearful eyes, consent to Amīr Khan’s unlawful execution.

Figure 6: The village head confronts the people who signed in favor of Amīr Khan’s execution, yet they cry for him. He is angered by their contradictory behavior. Still from the film Bī hamah chīz, directed by Muhsin Qarā’ī, 2021. Accessed via https://youtu.be/wxFcJ8eXVho?si=l3v-DzgfRTnoWeSi (01:48:09).

It is as though we are faced with a dark comedy, akin to Wild Tales (2014), directed by Damián Szifron, which depicts people trapped and suspended on the brink between civilization and savagery. The climax of violence in the film occurs during the execution scene, where collective brutality is portrayed as an expression of primal instincts. In this situation, the villagers’ greed and dishonesty lead them to execute Amīr Khan. Without any sense of right or wrong, they have already forced an innocent girl out of the village as a prostitute because the Khan told them to. The next day, under the orders of the same innocent girl—now wealthy—they decide to hang the penniless nephew of that very Khan. The final scene of the film echoes Friedrich Nietzsche’s view that many, cloaked in the guise of judges, wield the concept of “justice” as a weaponized rhetoric, using it against those who resist societal norms and remain unaffected by prevailing power structures.12Friedrich Nietzsche, Zur Genealogie der Moral (Berlin, New York: Walter de Gruyter, 1988), 369.

At the film’s climax, where the vote turns entirely against Amīr Khan, it becomes evident how, in a corrupt and decaying society, the concept of justice can be manipulated to destroy a life, transforming a once-heroic figure into a powerless individual through mechanisms of violence and deceit. On the other hand, the injustice Amīr committed in the past established a precedent for violence as normalized behavior among the villagers, and his actions are now bearing consequences for him. The night before Amīr’s execution, as he sits alone in a cell, ants swarm a grasshopper, likely symbolizing the people who once attacked Līlī on Amīr’s behalf. Now, in a changed situation, they are attacking Amīr on Līlī’s behalf.

Figure 7: A scene of ants attacking a locust inside Amīr Khan’s cell, where he was held the night before his execution. Still from the film Bī hamah chīz, directed by Muhsin Qarā’ī, 2021. Accessed via https://youtu.be/wxFcJ8eXVho?si=l3v-DzgfRTnoWeSi (01:43:28).

Only a disabled boy among them dares to oppose the injustice, symbolizing the silent voice marginalized and ignored in a brutal and corrupt society. The presence of this disabled child—resembling a Gandhi-like figure in the village—within the corrupt adult community illustrates how deeply rooted violence among people obstructs the expression of humanity, freedom, and progress.

Figure 8: Ahad, a disabled boy in the village, is the only one to protest Amīr Khan’s execution by raising his hand. Still from the film Bī hamah chīz, directed by Muhsin Qarā’ī, 2021. Accessed via https://youtu.be/wxFcJ8eXVho?si=l3v-DzgfRTnoWeSi (01:50:04).

Violence can be seen as a necessary tool in a world ruled by force, but only if it serves the goal of achieving lasting nonviolence. Simone Weil believed that a society can only last if it meets people’s deep human needs—like justice, order, and love—and if it solves conflicts through understanding and shared responsibility, not by using force.13Simone Weil, The Need for Roots: Prelude to a Declaration of Duties Towards Mankind (London: Routledge, 2002), 43-47. In this village, however, everyone is filled with concealed anger and resentment, making them estranged and hostile towards each other. Their violence resembles what Friedrich Engels described as a means of achieving economic gain.14Friedrich Engels, The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State (New York: International Publishers, 1972), 71-73.

At the very moment Amīr Khan tries to defend himself against violence, he ends up committing further injustice. He uses his daughter as a bargaining chip to save his own life. As the film’s main character confronts injustice, he transforms into someone who is the complete opposite of his true nature. It is as though all the ideals and values he once upheld are undermined by the pervasive influence of violence, leading him to even estrange himself even from his own family. Amīr’s struggle becomes a violent fight for survival rather than an effort to atone for the injustice he caused Līlī—whom he never truly regarded as a decent human being. “There are always the men with whom I am or can be in communication, and with them what is for me authentic being stands firm.”15Harold John Blackham, Six Existentialist Thinkers (UK: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1952), 57-58.

Figure 9: Āsiyah and her mother, shocked as they witness Amīr Khan attempting to flee the village with Asad’s help. Still from the film Bī hamah chīz, directed by Muhsin Qarā’ī, 2021. Accessed via https://youtu.be/wxFcJ8eXVho?si=l3v-DzgfRTnoWeSi (01:31:19).

Līlī, as the ruling class, resembles Hegel’s concept of the master, in that she is dependent on the servant or the lower class for the recognition of her identity. However, she is also wounded by the actions of all the villagers. From this perspective, the villagers cannot stand on their own without her financial support, and she, in turn, cannot take revenge on Amīr Khan without their violent actions. Thus, the master and servant are caught in a conflict where neither can achieve their goal without the other, yet both are each other’s worst enemies.16Alexandre Kojève, Introduction to the Reading of Hegel: Lectures on the Phenomenology of Spirit, ed. Allan Bloom, trans. James H. Nichols Jr. (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1980), 16–19.

In various scenes of the film, we witness different forms of violence. The day after Līlī arrives in the village, a woman named Nūrī creates a scene in front of Amīr Khan’s house, dragging the neighbors out and claiming her cow was killed. She verbally attacks Amīr Khan, trying to ruin his reputation, even though he is innocent in the matter.

Figure 10: Nūrī, angry about the killing of her ox at the train station, comes to Amīr Khan’s house the day after Līlī’s arrival in the village, intending to disgrace him in front of the neighbors. Still from the film Bī hamah chīz, directed by Muhsin Qarā’ī, 2021. Accessed via https://youtu.be/wxFcJ8eXVho?si=l3v-DzgfRTnoWeSi (01:50:11).

The violence depicted here ranges from physical acts, like throwing stones and injuring Amīr Khan, to verbal abuse, shown through threatening messages written on the wall across from his house. A form of symbolic violence in the film occurs when Asad, Āsiyah’s former and rejected suitor, demands her from Amīr Khan in exchange for sparing Amīr’s life, as Amīr tries to flee the village. He even demands a written agreement from Amīr Khan, fully aware that Āsiyah neither reciprocates his feelings nor is aware of his abusive demands. Additionally, other forms of violence include the forced taking of goods on credit, the looting of Amīr Khan’s shop, and coercing villagers to sign petitions to reopen the out-of-operation mine. Following Līlī’s request and in collaboration with Ustuvār Dashtakī, the villagers prevent Amīr Khan and his family from leaving the village. Amīr Khan’s daughter is beaten at school by two of the other students’ mothers, and while being physically assaulted, she is subjected to harsh verbal abuse, being labeled a “slut”—the same label that was once placed on Līlī many years ago.

Figure 11: With Līlī’s arrival in the village, the mothers of the schoolchildren begin insulting Āsiyah—Amīr Khan’s daughter and the schoolteacher—and physically assault her at the school. Still from the film Bī hamah chīz, directed by Muhsin Qarā’ī, 2021. Accessed via https://youtu.be/wxFcJ8eXVho?si=l3v-DzgfRTnoWeSi (01:20:29).

The threats and insecurity experienced by the village’s most trusted individual and his family exemplify psychological and emotional violence in a society that stagnates both spiritually—towards God—and introspectively—towards enhancing the lives of its people. Instead, this society strives to fulfill its existence through money and financial gain. As a representative of a different social class, Līlī presents a form of structural violence through which individuals must face the ethical consequences of their choices—similar to the concepts described by Nietzsche, who argued that “the elite were entirely right to be selfish, to sweep aside the weak and unable and simply seize for themselves whatever they wanted.”17Bryan Magee, The Great Philosophers: An Introduction to Western Philosophy (UK: Oxford University Press, 2000), 242.

In such a closed and violent society, it is unsurprising that balanced individuals are marginalized, a consequence of pervasive social violence. Mr. Sultanī, the only seemingly enlightened member of the local House of Justice, is beaten and rejected by the people after he tells the members in a meeting: “You are like locusts, going wherever the wind blows.”18Bī hamah chīz, dir. Muhsin Qarā’ī (Iran, 2021), 1:16:18.

Figure 12: The villagers beat Mr. Sultānī, the village teacher, after he asks Līlī to leave and voices his opposition to Amīr Khan’s execution. Still from the film Bī hamah chīz, directed by Muhsin Qarā’ī, 2021. Accessed via https://youtu.be/wxFcJ8eXVho?si=l3v-DzgfRTnoWeSi (01:18:53).

On the other hand, Amīr Khan, without any fair trial, is sent to the gallows simply based on the inked fingers and the consent of ungrateful people. This represents a blatant violation of human rights and a form of social violence—not imposed by the government on the people, but by the people on one another. In this case, it is the starving people who betray someone to whom they once paid allegiance.

The Interconnection of Justice and Violence

The film Bī hamah chīz explores the concepts of justice and violence through symbolism, complex character development, and thought-provoking dialogue. It delves into profound themes such as morality, judgment, and the influence of power and wealth on human decision-making. In Plato’s philosophy, justice is conceived as a state of harmony both within the individual—among the tripartite elements of the soul (reason, spirit, and desire)—and within society—among its distinct classes; consequently, personal revenge is seen as a potential disruptor of this equilibrium.Plato, Republic, trans. G.M.A. Grube (Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing, 1992), 441d-442a. Aristotle regards justice as involving proportional retribution in cases of wrongdoing, emphasizing that such responses must be guided by rational and ethical principles rather than personal vengeance.19Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics, trans. Terence Irwin (Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing, 2019), 1132a-1132b. Emphasizing the primacy of law and reason, Immanuel Kant conceives of punishment not as an act of revenge, but as a rational response aimed at restoring the moral and legal order, as well as deterring future violations.20Immanuel Kant, The Metaphysics of Morals, trans. Mary Gregor (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 331-333.

Līlī symbolizes revenge, power, and wealth—a woman who was wrongly accused years ago and has now returned to turn her personal revenge into a public act and to satisfy her desire for justice. Once seen as a victim, she now assumes the role of a judge, attempting to purchase justice with money. But is justice truly for sale? Are there things that should never be sold? Are there things money can buy, but morally shouldn’t? American philosopher Michael Sandel argues that in societies marked by inequality and weakened moral boundaries, market values can extend into all areas of life, leading to the commodification of goods and social practices that should not be for sale.21Michael J. Sandel, What Money Can’t Buy: The Moral Limits of Markets (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2012), 85-90. Līlī does not see her actions as revenge or violence, but as a way of reclaiming her rights. She expresses the depth of her pain in this sentence, addressed to Amīr Khan while they are in the mine: “My pain is that my child doesn’t call me mom, he calls me Līlī Khānum.”22Bī hamah chīz, dir. Muhsin Qarā’ī (Iran, 2021), 0: 54: 55. Nietzsche warns that when justice is driven by resentment, it risks becoming a justification for revenge, perpetuating violence rather than bringing it to an end.23Friedrich Nietzsche, On the Genealogy of Morality, trans. Walter Kaufmann and R. J. Hollingdale (New York: Vintage Books, 1967), 45.

Figure 13: In the mine, Līlī tells Amīr Khan that Farrukh is his son. Shocked, Amīr Khan asks if Farrukh knows, and Līlī replies that he does not. Still from Bī hamah chīz, directed by Muhsin Qarā’ī, 2021. Accessed via https://youtu.be/wxFcJ8eXVho?si=l3v-DzgfRTnoWeSi (00:53:34).

When Līlī arrives at the village, tension is unavoidable. The music builds as she walks from the train station towards the village elders, making the moment feel suspenseful and full of uncertainty. As the camera cuts to a close-up of her face, the music reaches an ominous crescendo—sharply contrasting with Līlī’s faint smile. The irregular rhythms of the soundtrack reflect the arrival of a character who embodies both power and vulnerability. As soon as she arrives at the station, a cow is brought forward in her presence. Despite assurances made to Nūrī, its owner, that the cow would not be sacrificed, it is brutally slaughtered as a qurbānī nonetheless. This occurs in front of another woman who, like Līlī, has just arrived—and whom the villagers mistakenly take for Līlī. People have always seemed to misunderstand events, see things the wrong way, and stay caught between guilt, violence, and their conscience. We are faced with a society lacking reflection and balance—a society where Nūrī’s brother is accidentally killed at the village checkpoint, and her cow is mistakenly slaughtered at the train station for the wrong woman. Līlī walks over the blood of the cow, entering a space where violence and injustice are deeply intertwined, arriving as a harbinger of both.

Figure 14: Upon arriving in the village, Līlī steps over the blood of Nūrī’s ox, mistakenly slaughtered instead of being returned to its owner. Still from the film Bī hamah chīz, directed by Muhsin Qarā’ī, 2021. Accessed via https://youtu.be/wxFcJ8eXVho?si=l3v-DzgfRTnoWeSi (00:18:55).

Although Amīr Khan is supposed to represent law and justice, he is in fact responsible for the injustice Līlī suffered in the past. Formerly the village judge, he now faces a challenge upon Līlī’s return: Should he stop Līlī’s personal revenge and stand by the law he once believed in, or go along with what the people want? The village stands as a metaphor for a traditional society grappling with shifting values, and Līlī’s proposal shakes the entire village like an earthquake, confronting its inhabitants with a moral dilemma between the temptations of financial gain and the imperatives of ethical integrity.

American philosopher John Rawls argues that justice should be structured to ensure that social and economic arrangements provide the greatest benefit to the least advantaged members of society.24John Rawls, A Theory of Justice (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1971), 75. Yet in this film, justice is shown in the opposite way. Instead of truly seeking justice, Līlī leads the villagers further into moral wrongdoing. Even Amīr Khan’s brother signs the petition to have him executed and plots against him.

In just three days, the villagers are convinced to kill their own hero, Amīr. The people Līlī was once afraid of are now the ones Amīr fears. When characters act self-righteously and are determined to deliver justice, they often resort to the harshest words and actions. At a pivotal moment in the film, the village headman confronts Amīr Khan, hands him a gun, and urges him to commit suicide—so that he may be remembered as a hero by the villagers. Amīr Khan refuses the request, and his confused look at the village headman—whom he himself had appointed—meets no shame, exposing the village’s deep drift from justice and honor.

Figure 15: Amīr Khan looks shocked as the village head brings him a weapon and suggests he commit suicide. Still from the film Bī hamah chīz, directed by Muhsin Qarā’ī, 2021. Accessed via https://youtu.be/wxFcJ8eXVho?si=l3v-DzgfRTnoWeSi (01:25:46).

In a society where violence is common, verbal violence—disguised as goodwill and friendship—flows freely from people’s mouths. Before Līlī’s train arrives, the village chief confesses to Amīr Khan that, after receiving no response, he forged Amīr Khan’s signature on the final letter to convince Līlī to come. When Amīr Khan reacts with anger, the chief dismissively responds, “You’ve given the people so much—add this to the list.”25Bī hamah chīz, dir. Muhsin Qarā’ī (Iran, 2021), 0: 15: 05. Now, that same man suggests that Amīr Khan’s suicide could appease the villagers. In this context, Hannah Arendt’s words come to mind: “If this were true, revenge would be the cure-all for most of our ills.”26Hannah Arendt, On Violence (New York: Harcourt, 1970), 20. The so-called moral logic is flawed and self-defeating; its contradictions reveal its fundamental irrationality.

In another scene, when Āsiyah, Amīr Khan’s daughter, prepares to leave the village for good, her mother weeps and begs her to stay, insisting she had no part in Līlī’s expulsion years earlier. Āsiyah, however, confronts her with quiet clarity: “You married him—you put your name on the mistakes he made.”27Bī hamah chīz, dir. Muhsin Qarā’ī (Iran, 2021), 1: 35: 52. Āsiyah’s departure scene, like Līlī’s arrival in the village, unfolds in slow motion, as if she is also stepping into danger, destined to share Līlī’s fate: exiled by the very people of her hometown—a reflection of the recurring cycle of disgrace and rejection.

Figure 16: After being beaten by her students’ mothers and her father’s escape plan is exposed, Āsiyah confronts her mother and leaves the village permanently. Still from the film Bī hamah chīz, directed by Muhsin Qarā’ī, 2021. Accessed via https://youtu.be/wxFcJ8eXVho?si=l3v-DzgfRTnoWeSi (01:35:18).

On the night before Amīr Khan’s execution, the village elders gather around a fire in the nearby mountains to decide how he should be killed. Each one tries to pass the responsibility onto someone else. The doctor tells the officer to shoot him and make it look like an accident. The officer responds that the doctor should give him a painless lethal drug instead. They even ask his own brother to kill him. In the end, everyone finds a way to avoid the burden of taking his life—a portrait of a society unwilling to face responsibility through conscious choice and action. It fails to realize that bearing responsibility is, in and of itself, an exceptional privilege—what Nietzsche calls a “rare and exceptional freedom” (seltene Freiheit). Finally, the village headman proposes, “We should do it collectively—so no single person is held accountable.”28Bī hamah chīz, dir. Muhsin Qarā’ī (Iran, 2021), 1: 38: 17. The community agrees to use violence together, claiming it’s for everyone’s benefit. This happens in a society that fails to truly see or respect people as individuals, especially because it doesn’t experience or acknowledge important human feelings like shame that help us recognize and care about others.

Figure 17: The night before Amīr Khan’s execution, the village elders gather in the mountains to discuss the best way to execute him, and Nūrī volunteers to knock the stool out from under his feet. Still from the film Bī hamah chīz, directed by Muhsin Qarā’ī, 2021. Accessed via https://youtu.be/wxFcJ8eXVho?si=l3v-DzgfRTnoWeSi (01:40:08).

Nūrī, the owner of the sacrificed cow who declares at the beginning of the film, “We would even give our lives to Amīr Khan,” also attends the elders’ gathering.29Bī hamah chīz, dir. Muhsin Qarā’ī (Iran, 2021), 0: 03: 03. She says she is willing to pull the stool away from under Amīr Khan’s feet, ensuring he hangs. This terrible moment shows a facet of human nature, where claims to moral entitlement are eventually linked to economic concerns.

The Protagonist’s Suicide and the Cycle of Violence

Līlī draws the vulnerable villagers into conflict for two reasons: to atone for her own painful past and to punish the villagers who oppressed and harshly judged her years earlier. Therefore, she forces them to face responsibility for their past actions while also humiliating them, undermining their human dignity. In fact, “it is the subjects who make the tyrant; they enable him to see no human being anymore, surrounded as he is by nothing but subjects.”30“Die Untertanen aber machen den Tyrannen, sie setzen ihn instand, vor lauter Untertanen keinen Menschen mehr zu sehen.” see Manès Sperber, Wie eine Träne im Ozean, vol. 1 (Frankfurt am Main: Fischer Verlag, 1955), 134. Thus, the subjects—who are themselves victims of the system—bear equal responsibility for this heinous act alongside Līlī. In the face of violence, neither silence nor withdrawal offer protection from its moral stain.

Figure 18: At noon prayer, the villagers gather in the square for Amīr Khan’s execution. Still from the film Bī hamah chīz, directed by Muhsin Qarā’ī, 2021. Accessed via https://youtu.be/wxFcJ8eXVho?si=l3v-DzgfRTnoWeSi (01:45:25).

Amīr Khan is so heavily affected by what others think of him that he lacks insight into the underlying complexities of life and society until he faces death. In this context, “Hume’s point is that when life has become a burden that cannot be borne, one is justified in taking it.”31Simon Critchley, “Notes on Suicide,” Naked Punch, accessed May 15, 2025, https://nakedpunch.com/notes-on-suicide/. According to David Hume, a person will not end their life unless they perceive it as no longer worth living.32Simon Critchley, “Notes on Suicide,” Naked Punch, accessed May 15, 2025, https://nakedpunch.com/notes-on-suicide/. Also see Simon Critchley, Notes on Suicide (London: Fitzcarraldo Editions, 2015), 25-30. For Amīr Khan, suicide becomes inevitable, and his calm demeanor at the execution—walking steadily through the crowd—reflects his submission to this systemic injustice. The shock of being separated from a treacherous community has already transformed him into a dead man, making any attempt at dialogue futile. At the beginning of the film, in the cemetery scene, Līlī extended an opportunity for dialogue to Amīr, but he perceived that it was already too late for conversation to resolve the matter: “Don’t you want to tell me something?”33Bī hamah chīz, dir. Muhsin Qarā’ī (Iran, 2021), 0: 22: 20. Amīr avoids it: “No.”34Bī hamah chīz, dir. Muhsin Qarā’ī (Iran, 2021), 0: 22: 28. Līlī offered him another chance when Amīr came to the old mine (once their secret meeting spot) to voice his complaints about the villagers’ harshness. There, Līlī tells him that Farrukh is his son and asks him: “Go tell the people you were wrong, tell them I wasn’t a prostitute. Tell them that child is yours…”35Bī hamah chīz, dir. Muhsin Qarā’ī (Iran, 2021), 0: 51: 03. But Amīr refuses: “You were sleeping with ten men… who knows what happened back then?”36Bī hamah chīz, dir. Muhsin Qarā’ī (Iran, 2021), 0: 51: 50.

Figure 19: In the mine, Līlī asks Amīr Khan to publicly acknowledge Farrukh as his son to spare his life, but Amīr Khan denies it and refuses to claim Farrukh as his son. Still from the film Bī hamah chīz, directed by Muhsin Qarā’ī, 2021. Accessed via https://youtu.be/wxFcJ8eXVho?si=l3v-DzgfRTnoWeSi (00:51:23).

Once again, Amīr Khan loses the opportunity to correct the past. The villagers make him the “scapegoat” to ease their collective guilt. René Girard argues that this kind of justice is only an illusion, turning violence into a repeating cycle shared by both the crowd and the scapegoat.37René Girard, Violence and the Sacred (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1977), 79-85. Amīr Khan’s suicide does not redeem the villagers from their collective guilt. He refuses to bear the sins of others in a Christ-like fashion. In committing suicide, he places a heavy burden of guilt on the villagers. His suicide will neither save him nor cleanse the community, offering no salvation for either him or the villagers. His voluntary death appears to be driven more by pressure from the people than by his own past or determination. Thus, it unleashes violence upon himself and others. Amīr Khan’s suicide deepens the cycle of violence instead of ending it. It deepens the village’s social divisions, preventing the villagers from achieving unity, peace, and resolving their problems. This is how a society moves towards destruction, as Rawls argues: “Any society which explains itself in terms of mutual egoism is heading for certain destruction.”38John Rawls, A Brief Inquiry into Meaning of Sin and Faith (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2009), 14, 189.

Amīr Khan’s death redefines moral concepts and acts as a wake-up call for a corrupt society, making the villagers realize that scapegoating and revenge only perpetuate a cycle of violence and hostility. His approach to justice, aimed at exposing the villagers’ evils, culminates in his suicide. He refuses to accept the fate his enemy has chosen for him, either execution or release. While standing on the execution platform, he asks the people, “Was I the only one who made a mistake? Did none of you make any mistakes?”39Bī hamah chīz, dir. Muhsin Qarā’ī (Iran, 2021), 1: 51: 32. Regarding social justice, Rawls argues that “the way to think about justice is to ask what principles we would agree to in an initial situation of equality.”40John Rawls, “The Case for Equality,” in Justice: What’s the Right Thing to Do? edited by Michael J. Sandel (New York: Macmillan, 2009), 140. He suggests that the fairest way to think about justice is to imagine a scenario in which people begin from a state of equality.

Figure 20: Standing on the execution platform, Amīr Khan’s last words reveal that Līlī came to the village because of his signature on the letter requesting help from her. Still from the film Bī hamah chīz, directed by Muhsin Qarā’ī, 2021. Accessed via https://youtu.be/wxFcJ8eXVho?si=l3v-DzgfRTnoWeSi (01:51:24).

Amīr Khan’s execution scene features a simple set design, emphasizing the harshness and starkness of rural life. Framed at the center, Amīr is portrayed as a victim of a profoundly unjust system. Gray and blue tones in the background highlight the villagers’ emotional detachment. In the execution scene, Līlī appears calm and emotionally distant and is sitting separately from the rest of the villagers, as if she doesn’t want to be part of what is happening. At the last moment, she risks herself helping Amīr Khan. She asks the village headman to bring him down from the gallows. The headman replies that everyone has approved the execution, and if it doesn’t take place, chaos will erupt in the village. He continues, “Why did you do this to us? How will we face Amīr tomorrow?”41Bī hamah chīz, dir. Muhsin Qarā’ī (Iran, 2021), 1: 53: 39. Līlī responds, “The same way you looked me in the eyes now.”42Bī hamah chīz, dir. Muhsin Qarā’ī (Iran, 2021), 1: 53: 50. However, constantly contemplating an evil act, as Līlī did, even without carrying it out, can deeply corrupt a person’s character or soul. As Simone Weil believes, “to go on for a long time contemplating the possibility of doing evil without doing it effects a kind of transubstantiation.”43Simone Weil, Gravity and Grace, trans. Arthur Wills (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press,1952), 95. Amīr Khan’s closest friends, and even his own brother, are already dressed in black mourning clothes, ready to witness his death. Even Līlī wears mostly black in this scene, a color that symbolizes anger and revenge.

Figure 21: Līlī tells the village head to take Amīr Khan down from the gallows, having decided to spare him. The village head protests her unexpected decision. Still from the film Bī hamah chīz, directed by Muhsin Qarā’ī, 2021. Accessed via https://youtu.be/wxFcJ8eXVho?si=l3v-DzgfRTnoWeSi (01:53:19).

In the final scene of the film, Āsiyah’s train enters a dark tunnel, and the film ends while her mother stands stunned at the station, and her father’s head is seen hanging on the gallows. Amīr’s suicide, driven by social pressure and revenge, marks the continuation of the cycle of violence. In the slow-motion scene of Amīr’s suicide, where the camera angle moves from the gallows to Līlī’s shocked face and then to others’, the viewers might wonder if anyone will rush to save him. Immediately after, the scene shifts to Līlī leaving the village, her face showing no sign of power or satisfaction from Amīr’s death or the fulfillment of her revenge. This is followed by Āsiyah’s departure on a train entering a tunnel. Just as Amīr commits suicide single-mindedly and out of revenge, Āsiyah also leaves with a single purpose—turning her back on her parents, seemingly driven by revenge. The tunnel symbolizes the illness of “tunnel vision” that all these people suffer from—that is, a narrow, linear way of seeing issues without awareness of the wider context or other perspectives. Even Amīr seems only to see the tunnel’s end, which is death. This vision symbolizes a society that favors violence and avoids responsibility.

Figure 22: While Līlī, having decided to spare Amīr Khan, gets into a car to leave the village, Amīr Khan voluntarily knocks the execution platform from under his feet. Still from the film Bī hamah chīz, directed by Muhsin Qarā’ī, 2021. Accessed via https://youtu.be/wxFcJ8eXVho?si=l3v-DzgfRTnoWeSi (01:54:40).

The soundtrack, a blend of classical and modern music, begins just before Amīr’s suicide and continues until the end of the film, when Līlī and Āsiyah depart. The music is dramatic, tragic, and suspenseful, accompanying Līlī’s, Amīr’s, and Āsiyah’s acts of revenge against the villagers, each in their own way. During Amīr’s suicide, the music acts as a silent narrator, its rhythm synchronized with the editing to convey a sense of collective guilt and the accelerating moral decline of the community.

Conclusion

A comprehensive understanding of the various forms of violence can help answer numerous questions regarding its origins and inherent nature. Violence is not only a product of a specific social condition but is also a part of human nature. Violence is an inhumane act rooted in an inner deficiency that causes individuals to perceive “evil” in the Other. By depicting the blurred boundary between justice and violence, the film Bī hamah chīz raises the question of whether violence can ever be justified as a means of achieving justice. Many philosophers, including Friedrich Nietzsche, would answer negatively. When Līlī uses her wealth to compel the villagers to confront their past and pursue revenge against them all, that revenge ultimately results in greater injustice, plunging an already unjust society deeper into a cycle of violence and moral decay.

The film shows that while revenge may sometimes be viewed as a form of justice, it is often accompanied by violence and injustice, which can destabilize society. Administering justice based on personal judgment turns ordinary people into morally corrupt beings, leading them towards moral decay. In this moral decay, the people accept Līlī’s proposal and turn justice into a commodity that can be bought and sold. In a society where the economy determines moral principles, justice becomes purchasable as well. The film illustrates how, in a fragile and morally decaying society, guilt is magnified and the line between violence and justice blurs.

What unites these people in killing Amīr Khan is not a social contract, but violence rooted in what Nietzsche calls “slave morality” —a moral system where the weak advocate for equality and justice, yet are primarily driven by jealousy, hatred, and resentment towards their masters. This hatred becomes the Achilles’ heel of justice. The villagers in this film are those who, by silence and acceptance of rumors, condemned Līlī to a bitter fate in the past and are now drawn into a new test by her proposal. Such people have the potential to repeatedly sacrifice morality.

Līlī’s proposal to share her wealth with the villagers in exchange for killing Amīr symbolizes a clear form of inverted justice—that is, justice at the cost of morality, reflecting the collapse of ethical principles under pressure. American philosopher Martha Nussbaum argues that anger and revenge are human emotions that, if uncontrolled, can lead to more injustice.44Martha C. Nussbaum, Anger and Forgiveness: Resentment, Generosity, Justice (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016), 45-50. The film Bī hamah chīz shows how Līlī’s anger ultimately leads to a cycle of violence and forces people to face moral contradictions, bringing neither balance nor harmony to the small community. Amīr’s death may not fulfill Līlī’s sense of revenge, but it will certainly force the villagers to confront the consequences of their actions and inflict new wounds on this troubled society.

Figure 23: Līlī arrives at Amīr Khan’s execution ceremony, where the crowd greets her with joy. Still from the film Bī hamah chīz, directed by Muhsin Qarā’ī, 2021. Accessed via https://youtu.be/wxFcJ8eXVho?si=l3v-DzgfRTnoWeSi (01:46:56).

Punishing individuals in a society requires structural legal reforms and human rights-based discussions to replace violent approaches. Justice must be pursued in ways that ensure fairness, stop the cycle of violence, and help build a more just society. Historically and socially, in Iran, relying on legitimized violence and staged trials as means of justice has neither been effective in the short term nor sustainable in the long run. Such instability erodes moral values and drives society towards social collapse.

Cite this article

This article analyzes Muhsin Qarā’ī’s Bī hamah chīz (Without Anything, 2021) through an interdisciplinary lens, examining how the film blurs the boundaries between justice and violence. Drawing on philosophical and sociological theories—from Nietzsche and Arendt to Rawls and Zizek—it explores how personal revenge, disguised as justice, becomes a collective moral failure. Set in a rural village, the narrative follows Līlī, a wealthy woman returning to seek retribution, and how her actions expose the villagers’ ethical vulnerabilities. The film critiques the commodification of justice in a corrupt society where violence becomes normalized, even rationalized. Through symbolic imagery, psychological nuance, and social allegory, Bī hamah chīz challenges viewers to reconsider the legitimacy of violence when justice is manipulated for personal or communal gain. The article ultimately argues that in morally unstable societies, the pursuit of justice without ethical grounding only deepens cycles of violence and division.