The Decolonization of Collective Self-Criticism in Iranian Cinema

Introduction

On April 30, 1907, an Iranian writer, likely Mu’ayyid al-Islām Kāshānī, published in the newspaper Habl al-Matīn the question: “Is Iran ill?” and answered in the affirmative. This 44-year-old intellectual, who had spent 14 years publishing one of the most popular journals before and during the Constitutional era and played a key role in the Constitutional Revolution by writing critical articles on political despotism and advocating for freedom and the rule of law, believed that Iran was afflicted by a chronic disease.1Īraj Pārsīnizhād, “Habl al‑Matīn Matīnī,” Iran‑Namag, year 28, no. 2 (Summer 2013), accessed December 11, 2025, https://www.irannamag.com/article/حبل¬المتین-متینی/ He believed that Iran’s worsening condition was the result of a deliberate disregard by its people, himself included: “Every day, we saw Iran getting weaker… its face growing pale… yet we were too full of pride to notice.” He went on to suggest: “We need to bring the doctors to the sick mother’s bedside so that anyone who knows how to heal her can share their knowledge.”2Habl al-Matīn, April 30, 1907, 1.

The metaphor of the “mother” to describe the homeland, used in the early stages of modern Iran’s formation, coupled with the portrayal of each Iranian as a child who, through indifference, witnesses the suffering and violation of their mother, evoked a profound sense of shame. This deeply influenced the “modern Iranian psyche” and the collective emotional consciousness of Iranians at the dawn of modernity.3Mostafa Abedinifard, “Iran’s ‘Self-Deprecating Modernity’: Toward Decolonizing Collective Self-Critique,” International Journal of Middle East Studies 53, no. 3 (2021), 17. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020743821000131. Iranian modernity fundamentally emerged from the emotional responses of various Iranian elites to the country’s military confrontations with imperialist Western powers in the early 19th century.4Firoozeh Kashani-Sabet, “Hallmarks of Humanism: Hygiene and Love of Homeland in Qajar Iran,” American Historical Review 105, no. 4 (2000): 1171. The defeats of Iran in two series of wars with Russia, followed by the humiliating treaties of Gulistān (1813) and Turkamānchāy (1828), fostered a sense of collective shame and inferiority among Iranian elites in the face of Europe’s technological and military superiority. At the same time, these events framed the West as a mocking and judgmental “Other.”5Mostafa Abedinifard, “Iran’s ‘Self-Deprecating Modernity’: Toward Decolonizing Collective Self-Critique,” International Journal of Middle East Studies 53, no. 3 (2021), 3. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020743821000131.

In this context, the West gradually emerged as an idealized “Other” for Iranians, its reproachful gaze ever-present, while Iranians became increasingly preoccupied with the fear of being “mocked and ridiculed by the world.”6Sur-i Israfil, September 19, 1907, 5; “Iftitāh-i Majlis va Jaryān-i Intikhābāt,” Jārchī-i Millat, August 27, 1915, 2. According to Abedinifard, the fear of being ridiculed was central to the formation of modern Iranian identity, leading to the discourse of “self-deprecating modernity,” which stemmed from mid-19th-century intellectuals’ anxieties about Europe and the self-monitoring encouraged by the European gaze.7Mostafa Abedinifard, “Iran’s ‘Self-Deprecating Modernity’: Toward Decolonizing Collective Self-Critique,” International Journal of Middle East Studies 53, no. 3 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020743821000131. Within this framework, Iranian modernists viewed the critique, reproach, and self-deprecation of Iranian practices and discourse as crucial for advancing Iran and its people toward progress and modernization.8Mohamad Tavakoli-Targhi, Refashioning Iran: Orientalism, Occidentalism and Historiography (New York: Palgrave, 2001. “Mockery based on shame” became a central theme in much of the elite and popular social satire and critique produced by modernist writers such as Muhammad ‛Alī Jamālzādah, Sādiq Hidāyat, Īraj Pizishkzād, and Ja‛far Shahrī.9Mostafa Abedinifard, “Iran’s ‘Self-Deprecating Modernity’: Toward Decolonizing Collective Self-Critique,” International Journal of Middle East Studies 53, no. 3 (2021): 17, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020743821000131.

Over the past century and a half, the belief that social problems are rooted in individual characteristics—be they psychological, racial, personal, or identity-related—has shown itself to be a double-edged sword. On one hand, it has allowed conservative forces to dismiss the possibility of social reform by attributing societal problems to these traits. On the other hand, it has given progressive forces an opportunity to demonstrate the practicality of their ideals, even while acknowledging that these same traits could cause ruptures or stagnation in realizing those ideals. Following each setback in idealistic modernization—be it the unrealized reforms of Nāsir al-Dīn Shah (1848–96), the unfulfilled promises of the Constitutional Revolution (1905–11), the unachieved aims of the 1950s nationalist movement and the 1979 Revolution, or later reform efforts under the Islamic Republic—a renewed discourse on Iran’s national characteristics emerged. While these discourses vary in their assumptions and approaches, they all involve comparison with an idealized “Other” and evoke a sense of collective shame.10Ibrāhīm Tawfīq, Sayyid Mahdī Yūsifī, Hisām Turkamān, and Ārash Haydarī, Bar’āmadan-i zhānr-i khulqiyyāt dar Īrān (The Emergence of the Folk Characteristics Genre in Iran) (Tehran: Pazhūhishgāh‑i Farhang, Hunar va Irtibātāt, 2019), 57.

A key insight from Abedinifard, which underpins this article, is that this mocking and shame-inducing perspective, despite its historical functions, comes at the cost of “othering” or marginalizing specific identities within Iranian society—such as rural versus urban populations, non-Persian versus Persian groups, and women versus men. From this perspective, a self-deprecating literature is produced within a complex network of power relations in Iranian society and culture. Regardless of the intentions of its creators, it inevitably reinforces and regulates social norms—norms that, paradoxically, were the very impetus for the creation of these critical works.11Ibrāhīm Tawfīq, Sayyid Mahdī Yūsifī, Hisām Turkamān, and Ārash Haydarī, Bar’āmadan-i zhānr-i khulqiyyāt dar Īrān (The Emergence of the Folk Characteristics Genre in Iran) (Tehran: Pazhūhishgāh‑i Farhang, Hunar va Irtibātāt, 2019), 57. Abedinifard introduces the concept of “decolonizing collective self-criticism,” arguing that in non-colonial forms of self-reflection, there is no trace of collective shaming or self-deprecation in relation to the idealized Western Other. Instead, self-reflection serves to prevent inhumane actions and promote humane behavior.12Mostafa Abedinifard, “Iran’s ‘Self-Deprecating Modernity’: Toward Decolonizing Collective Self-Critique,” International Journal of Middle East Studies 53, no. 3 (2021): 17, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020743821000131. This study seeks to reexamine Iranian social cinema through the lens of its role in challenging self-deprecating attitudes and fostering non-colonial self-criticism.

Research Problem and Theoretical Lens

Since the Green Movement in 2009, and especially after the November 2017 uprisings advocating equality-focused politics, Iran has experienced a significant social shift.13Ibrāhīm Tawfīq and Sayyid Mahdī Yūsifī, “Zan, Zindagī, Āzādī: Inqilāb‑i Millī yā Inqilāb‑i Mardum?” (Woman, Life, Liberty: National Revolution or People’s Revolution?), Naqd-i Iqtisād-i Siyāsī (December 21, 2022), accessed December 11, 2025, https://pecritique.com/2022/12/21/. According to Ibrāhīm Tawfīq, following these uprisings, there was an increase in self-blame and an emphasis on the negative traits and values of Iranians that hindered social change. This trajectory ultimately gave rise to a “movement against humiliation” in 2022, under the slogan Women, Life, Liberty.14Ibrāhīm Tawfīq and Sayyid Mahdī Yūsifī, “Zan, Zindagī, Āzādī: Inqilāb‑i Millī yā Inqilāb‑i Mardum?” (Woman, Life, Liberty: National Revolution or People’s Revolution?), Naqd-i Iqtisād-i Siyāsī (December 21, 2022), accessed December 11, 2025, https://pecritique.com/2022/12/21/.

The formation of a “movement against humiliation” in a society that has historically regarded self-deprecation as a means of pursuing the long-held dream of “joining the caravan of civilization” is a significant phenomenon, warranting in-depth sociological and social-psychological study. However, it is clear that this shift did not occur suddenly; rather, it emerged from the gradual actions of social forces, each representing a distinct and insightful area for research. Social cinema, as a powerful cultural and social force, has played a role in reshaping Iranians’ critical self-deprecation. From this perspective, cinema is understood as a force that, by critically reflecting on the present, reveals the fragility of the social order, promotes dialogue and the questioning of normalized values, and contributes to the formation of collective meaning while generating new ideas.

To enhance theoretical and methodological precision, this study focuses on the thirteen-year interval between the Green Movement and the Women, Life, Liberty Movement—a period marked by intermittent uprisings that provides a context for examining shifts in social attitudes. During this time, the psychological and social conditions of Iranian society gave rise to numerous films exploring themes of protest, critiques of the existing order, and challenges to long-standing social beliefs—many of them comedies with a sharply satirical tone. Focusing on social cinema and using criteria related to authorship, festival recognition, public dialogue, reflective discourse, and potential for change, four films were selected as case studies: Tales (Qissah’hā, Rakhshān Banī-i‛timād, 2011), Sofa (Kānāpah, Kiyānūsh ‛Ayyārī, 2016), A Hero (Qahramān, Asghar Farhādī, 2021), and Leila’s Brothers (Barādarān-i Laylā, Sa‛īd Rūstā’ī, 2022). These films were analyzed using an ethnographic-methodological approach to examine how they contributed to strengthening critical self-deprecation.

This approach understands every society as possessing an internal order that is produced and sustained by its members. Although this order appears stable, it is historically contingent and inherently fragile. Individuals may resist it, but such resistance is typically met with pressures aimed at restoring conformity. Over time, gradual shifts and new values emerge through the actions of “order-breakers,” who bear the social costs of challenging established norms. Social order is thus continuously and creatively reconstructed, and the ethnographic-methodological analyst demonstrates how new orders arise from the dynamic interplay between “order-breakers” and “order-pursuers.” As Harold Garfinkel argues, the sociologist’s proper object of study is the real world of everyday life: the organized, ongoing performance of coordinated activities carried out by individuals who not only know how to accomplish them routinely but do so with considerable skill and practical subtlety.15Harold Garfinkel, Studies in Ethnomethodology (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1967), 3.

Drawing on Abedinifard’s distinction between “colonial self-deprecation” and “non-colonial self-criticism,” this article analyzes Tales, Sofa, A Hero, and Leila’s Brothers. “Colonial self-deprecation” refers to a form of collective shaming grounded in comparison with an idealized Other that reinforces a self-deprecating order, whereas “non-colonial self-criticism” avoids such idealized Othering while recognizing both the fragility of self-deprecation and the potential for creating new forms of order.

Tales

Rakhshān Banī-i‛timād’s Tales (2011) came more than a century after Mu’ayyid al-Islām lamented in his newspaper that Iran was “sick.” Two years after the suppression of the Green Movement, Banī-i‛timād turned her camera to the lives, dreams, and struggles of ordinary Iranians, revealing the enduring fragility of both the nation and its people.

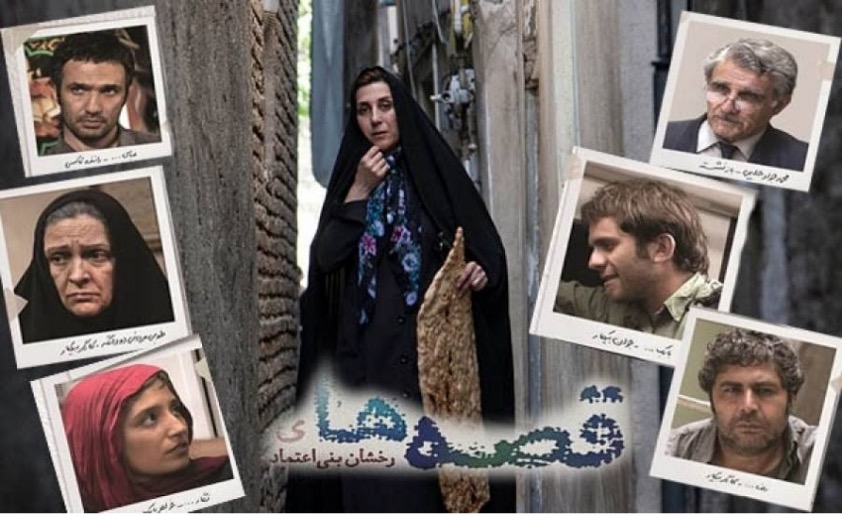

Figure 1: Poster for the film Tales (Qissah’hā), directed by Rakhshān Banī-i‛timād, 2011.

Tales opens at night in the confined space of a taxi. The driver, ‛Abbās (Muhammad Rizā Furūtan), speaks to an inattentive passenger about his dream of leaving Iran to seek refuge with the “ideal Other.” Years earlier, he had sold his home and handed the proceeds to swindlers who promised him a work visa abroad—a deception that led to profound suffering for his mother, Tūbā Khānum (Gulāb Ādīnah). Yet the mother never shames him or adds to his pain. In the film, Tūbā embodies the figure of “Mother Iran” in historical memory: despite enduring numerous hardships, she remains devoted to the welfare of her children.

Figure 2: A still from the film Tales (Qissah’hā), directed by Rakhshān Banī-i‛timād, 2011.

Tūbā has another son who was arrested during street protests and requires a substantial bail. To raise the necessary funds, she turns to a charity for a loan. When asked what crime her son committed, she replies, “He took to the streets to make his voice heard, like other young people.”16Tales, directed by Rakhshān Banī-i‛timād (Iran, 2011), 00:41:30. The charity worker, however, tells her that she should not have allowed her son to join the protests and that the charity cannot help with the bail. Just as her son—like many young people—could not make the authorities listen, Tūbā cannot persuade the charity worker. The scene ends with her crying, coughing, and collapsing as others look on without concern.

In another scene, Tūbā tries to claim her unpaid wages but becomes lost in bureaucratic confusion. She asks a polite elderly man (Mahdī Hāshimī), who has also been waiting for hours, to help her write an administrative letter. The man begins helping her by writing the letter, but before he can finish it, through a sudden turn of events, he manages to force his way into the manager’s office—the very office he had been waiting hours to enter. The manager shirks his administrative responsibility and rudely refuses the man’s request, expelling him from the office. Frustrated, the elderly man shouts in the crowded hallway, yet none of the onlookers, including Tūbā, offers a word of support or empathy; they merely watch, worried and helpless.

Figure 3: A still from the film Tales (Qissah’hā), directed by Rakhshān Banī-i‛timād, 2011.

The film highlights the difficulties Iranians face in conducting effective dialogue and fostering constructive communication. It portrays the loneliness and confusion of individuals who are unable either to express themselves to others or to listen attentively to others’ narratives. People—whether managers or clients, protesting workers or security personnel, couples, or parents and children—become frustrated when their words are misunderstood and attempt to compel others to listen through angry outbursts. In this context, those with greater power can ultimately impose their will, while those with less power have no recourse other than “escape” or “deception.” Over time, “cunning” emerges as a fundamental mode of communication, without which social interactions cannot function.17William O. Beeman, Language, Status, and Power in Iran (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1986), 54.

According to William Beeman, in Iranian culture, “cunning” is a strategy employed by those with less power to shape how others perceive a situation, thereby prompting them to act in ways that advance the cunning individual’s goals.18William O. Beeman, Language, Status, and Power in Iran (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1986), 54. Aware of this subtle cultural nuance, Banī-i‛timād, after depicting Tūbā’s failed dialogue in the domestic sphere and the elderly man’s unsuccessful interaction in the public sphere, presents a pivotal scene featuring a conversation between a sister (Nigār Javāhiriyān) and a brother (Bābak Hamīdiyān) on the subway. They discuss the details of their plan to extort their father by pretending that his daughter has been taken hostage. Hoping that he will pay the demanded sum out of concern for his “reputation,” they plan to use the money to settle the son’s debts and extricate him from his difficult situation.

Figure 4: A still from the film Tales (Qissah’hā), directed by Rakhshān Banī-i‛timād, 2011.

An analysis of these three scenes, from an ethnographic perspective, clearly illustrates the methods and logic through which order based on cunning is established in everyday interactions among Iranians. In a context where reliance on deceptive cleverness becomes a central strategy for achieving one’s goals, trust and empathy are difficult to sustain, as individuals cannot reliably discern which narratives are genuine and which are fabricated. This, in turn, generates a vicious cycle of “powerlessness–deceptive cunning–distrust,” fostering cautious and isolated social behavior and reinforcing corrupt and ineffective social systems.

What distinguishes this film from works exploring a theme of colonial-induced self-deprecation is that it does not leave the audience feeling helpless and humiliated in the face of this tragic cycle. Instead, by depicting a conversation between Hāmid (Paymān Ma‛ādī) and Sara (Bārān Kawsarī) at the end of the film, Banī-i‛timād demonstrates that being trapped in this situation is neither inevitable nor unchangeable for Iranians. Individuals can, if they choose, break free from this cycle and create a new order in their relationships. In this key scene, Banī-i‛timād shows both the ability to move beyond othering and the personal and cultural obstacles to successful dialogue, emphasizing the individual’s capacity to overcome them.

Hāmid was a talented student who was expelled from university due to his political activities and is now forced to make a living by driving for a non-governmental center that supports vulnerable women. Sara, on the other hand, was formerly addicted but, with her family’s help, managed to recover and has now devoted her life to volunteering at the same private center, assisting women and girls struggling with addiction. In this sense, Hāmid and Sara are examples of people who, caught in a corrupt and inefficient structural system, are either “abandoned” or “punished,” and, feeling bitter and wounded, keep their distance from one another while simultaneously suffering from their tense relationship. In the final scene, Hāmid ultimately decides to attempt to change the grim situation they have both been experiencing through dialogue with Sara.

|

|

Figures 5-6: Stills from the film Tales (Qissah’hā), directed by Rakhshān Banī-i‛timād, 2011.

In the confined space of the car at night, they engage in an emotionally tense conversation. By assigning labels to each other and belittling one another, they slip into mockery and hurtful words, eventually withdrawing into frustrated silence. Yet their shared desire to communicate pushes them to try again, and they eventually manage to recognize each other’s preconceived ideas. By creating an honest and equal space, they make genuine dialogue possible. However, this possibility is portrayed as fragile—easily lost with even a small mistake. Realizing they cannot escape their difficult situation—where their “positions are unclear”—without talking, Hāmid and Sara work together to keep their interaction honest and free of power struggles.

Both care about helping others and improving society, but they disagree on how change should be brought about. Hāmid sees Sara’s efforts as limited and superficial, while Sara accuses Hāmid of being overly ideological and out of touch with reality. In the end, Hāmid tells her: “Let me talk. You’ve built a wall around yourself; you neither look beyond it nor at yourself… just live your normal life.”19Tales, directed by Rakhshān Banī-i‛timād (Iran, 2011), 01:18:30. These words, and the way the idea of a “normal life” arises in the conversation, reveal another truth about everyday interactions among Iranians: whether focused on their own problems or trying to help others and bring about social change, they often pay little attention not only to others but also to themselves. It is only through careful attention to “the self, the other, and the relationship” that the absence of a normal life within daily routines and collective practices can be discerned. In Tales, Banī-i‛timād, alongside Sara and Hāmid, invites the audience to engage in this same attentive reflection.

Reflecting on what truly matters in life pushed Hāmid and Sara to talk about love and being loved. Sharing their feelings helped them come out of their shells, open up, and engage in an honest conversation. Hāmid told Sara that, even though he knew she was HIV-positive, he loved her and wanted to be close. By releasing the burden of keeping this secret, Sara was able to dismantle the walls she had built around herself. Breaking free from their “isolating distrust” also freed them from the fear of judgment and the “fear of losing face,” paving the way for their story to come together and for them to become active participants in a shared narrative. Though night still lingered and the space remained confined, a faint hope began to take root.

Sofa

In Iranian culture, “reputation” shapes one of the most dominant social patterns, and the fear of losing it affects not only everyday decisions but also many of life’s more fundamental choices.20Farzad Sharifian, “L1 Cultural Conceptualisations in L2 Learning: The Case of Persian‑Speaking Learners of English,” in Applied Cultural Linguistics: Implications for Second Language Learning and Intercultural Communication, ed. Farzad Sharifian and Gary B. Palmer (Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company, 2007), 36, https://doi.org/10.1075/celcr.7.04sha. In this culture, the expression “keeping your face red with slaps” refers to someone who goes to great lengths to hide their illness or poverty, even slapping their own face to make it appear healthy and conceal any signs of paleness. Kiyānūsh ‛Ayyārī built his film Sofa (2016) around this idea, using it to reveal how truth is concealed and how life in Iranian culture often becomes a complex performance.

Figure 7: Poster for the film Sofa (Kānāpah), directed by Kiyānūsh ‛Ayyārī, 2016.

The film opens with Hūshang (Farhād Āyīsh), a middle-aged, well-respected man, staring at a few relatively intact couches left beside a park trash bin and pretending they belong to him. Moments later, when no one is around, he and a street cleaner carry one of the couches to his home to replace his old, worn-out one. Unable to afford a new couch, Hūshang does this because a suitor is coming to propose to his daughter, and it is important that the house appear respectable so the suitor’s family will not notice his poor financial situation.

As soon as his wife (Ātūsā Anvāriyān) sees the second-hand couch, she panics and accuses him of bringing “other people’s trash” into their home. She is distressed that even the street cleaner, who often receives food and tea from them, now knows how “poor” they are, and she believes her husband has ruined their “reputation.” Hearing her shouting, the daughters rush in, worried that someone might have seen their father carrying “other people’s trash” into the house. Vīdā (Fargul Farbakhsh), for whom her father brought the couch to impress her suitor, exclaims, “If even one neighbor saw it, we should all kill ourselves.”21Sofa, directed by Kiyānūsh ‛Ayyārī (Iran, 2016), 00:09:15. In the end, however, they agree that if they wash and clean the couch and replace the old one, it will at least look more respectable. Finally, the old couch—symbolizing all that Iranians consider shameful and spend enormous amounts of time, energy, and stress trying to hide from others—is moved to the bedroom, the “backstage” of the home.

Figure 8: A still from the film Sofa (Kānāpah), directed by Kiyānūsh ‛Ayyārī, 2016.

With an emphasis on two domains of symbolic cultural opposition that play a fundamental role in Iranian life—namely, the opposition between appearance and reality (andarūnī and bīrūnī) and the opposition between hierarchy and equality22 William O. Beeman, Language, Status, and Power in Iran (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1986), 35.—‛Ayyārī portrays the exhausting complexity of hidden and performative social relations. At the engagement party, the groom’s mother (Farībā Kāmrān) notices that the old couch, left next to a street trash bin, has ended up in her future daughter-in-law’s home. Until then, the bride’s family had tried to conceal their financial inferiority, and both families had pretended to be equal. But when it becomes clear that the bride’s family valued a couch the groom’s family considered trash, the balance of status between the two families is completely disrupted. The groom’s mother, at the first opportunity, indirectly made Vīdā understand what had happened, thereby turning the nightmare of disgrace into reality for Vīdā and her family. Vīdā became short of breath; in a desperate attempt to escape the situation, she tore the couch with a kitchen knife. When Vīdā’s mother realized what had happened, she said: “I want to stick this knife in my heart.”23Sofa, directed by Kiyānūsh ‛Ayyārī (Iran, 2016), 00:31:34.

Figure 9: A still from the film Sofa (Kānāpah), directed by Kiyānūsh ‛Ayyārī, 2016.

Figure 10: A still from the film Sofa (Kānāpah), directed by Kiyānūsh ‛Ayyārī, 2016.

The two families never openly discussed the couch issue and were unable to resolve the distressing situation through dialogue. Vīdā did not answer the calls of her fiancé, Mustafā (Bābak Hamīdiyān), and Mustafā was likewise unable to create a space for honest and constructive conversation about the matter. Each character in the film suffers alone from the situation, and their inability to express or share this suffering—or to work together to overcome it—manifests as aggressive anger, expressed through the violent tearing apart of couches, reckless driving, shouting, insults, and humiliation, ultimately culminating in the father’s tragic death in isolation and rejection.

The film goes beyond a humiliating portrayal of secrecy and fear of disgrace in Iranian culture, as the director not only shows the high costs of resisting the social order but also turns the making of the film itself into an act of defiance against filmmaking norms in Iran. The female actors wear wigs instead of veils, making the film a violation of the mandatory hijab law—a law that, ironically, has long been tied to preserving the honor of women, families, and the Islamic regime.

Figure 11: A still from the film Sofa (Kānāpah), directed by Kiyānūsh ‛Ayyārī, 2016.

In films produced under the Islamic Republic, women—even when portraying a wife alone at home with a man cast as her husband—are required to wear the hijab, a rule that continually reminds Iranian audiences of the staged nature of both the scene and the human relationship it depicts. In this way, ‛Ayyārī sought to ease the discomfort of performing artificial scenes imposed by social rules. Rather than requiring female actors to wear hijabs, he had them wear wigs, thereby reducing the sense of forced artificiality—much as the film’s father figure navigates social pressure to appear financially secure at minimal cost. Yet it seems that an unseen hand punished them both for not fully adhering to social constraints: the father dies alone in the film, and ‛Ayyārī’s film did not receive state permission for screening. ‛Ayyārī suggests that challenging a rigid social order—one that generates isolation, anger, exhaustion, and a profound inability to communicate or solve problems—demands an exceptionally high cost. But instead of frightening or discouraging people, leaving them helpless and humiliated before rigid social rules, he encourages the audience to persist on this path.

Figure 12: A still from the film Sofa (Kānāpah), directed by Kiyānūsh ‛Ayyārī, 2016.

After the father’s death, Vīdā moves the old couch from the bedroom to the living room. Her younger sisters try to stop her, saying, “This couch is terrible” and “This will ruin Dad’s honor,” but their mother, the protector of family honor in the film, does not resist. Mustafā’s family comes to offer condolences for the father’s death, and Vīdā asks them to sit on the old, worn, and dirty couch—the very one that had caused all the earlier trouble. In this moment, the heavy cost of concealing private matters in everyday life—so evident at the beginning of the film—suddenly seems to disappear. Mustafā’s family sits on the couch they were never meant to see; the mother watches them indifferently, and Mustafā, like an audience member, sits calmly and smiles, as if finally relieved of a great burden.

By avoiding clichéd comparisons of negative Iranian cultural patterns with an idealized superior culture and emphasizing the flexibility of rigid traditions, the film offers a successful example of non-colonial self-criticism in Iranian social cinema.

A Hero

Moral perfectionism has deep roots in Iranian culture, nourished both by the Manichean notions of right and wrong and the utopian beliefs of ancient Iran, as well as by the doctrine of infallibility (‛ismat) in Twelver Shi’ism.24Simon Theobald, “The Perils of Utopia: Between ‘Ethical Static’ and Moral Perfectionism in Iran,” Critique of Anthropology 43, no. 2 (2023): 140, https://doi.org/10.1177/0308275X231175986. Within this framework, moral perfection is regarded as a real and achievable goal rather than a distant ideal; consequently, it is not unusual to expect people’s words and actions to align in daily life and for them to act honestly and transparently in their social relationships.25Simon Theobald, “The Perils of Utopia: Between ‘Ethical Static’ and Moral Perfectionism in Iran,” Critique of Anthropology 43, no. 2 (2023): 134, https://doi.org/10.1177/0308275X231175986. In this context, contradictory behavior is seen not as a normal part of everyday ethics but as serious wrongdoing, casting doubt on a person’s honesty and warning those around them of possible deceit.26Simon Theobald, “The Perils of Utopia: Between ‘Ethical Static’ and Moral Perfectionism in Iran,” Critique of Anthropology 43, no. 2 (2023): 133, https://doi.org/10.1177/0308275X231175986.

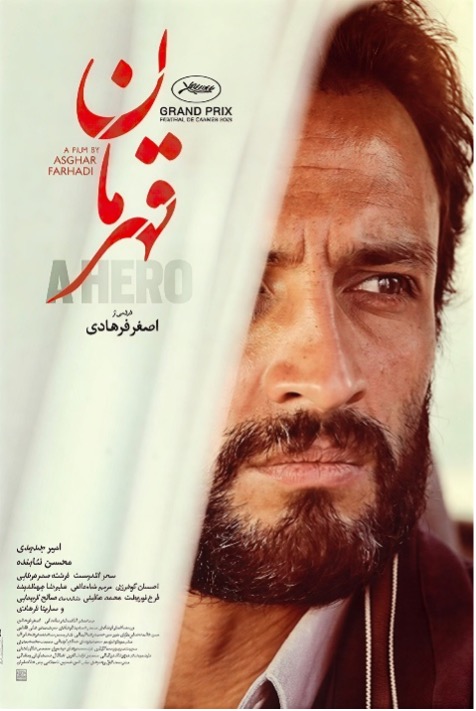

Figure 13: Poster for the film A Hero (Qahramān), directed by Asghar Farhādī, 2021.

Moral perfectionism increases distrust because, in real life, no one is as pure and honest as Siyāvash, the exemplary legendary Iranian hero who passed the test of fire unharmed. In a society that demands moral perfection, people hold heroes to unrealistically high standards. When those heroes display even minor flaws, it leads to disappointment and a loss of trust. As a result, people begin to doubt everyone’s intentions and search for selfish or manipulative motives, even behind actions that appear good or admirable. As Beeman notes, such a society can only interpret any ordinary social situation as part of a dynamic continuum rather than as a single, isolated event.27William O. Beeman, Language, Status, and Power in Iran (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1986), 115. Against this backdrop, Iranians tend to judge a specific behavior by looking at a person’s entire life history, their choices in other areas of life, the consequences of those choices, and more broadly, anything connected to the individual and their actions. Asghar Farhādī, focusing on “moral perfectionism” in A Hero (2021), uses this issue as a tool to critique corrupt structures and the collective reproduction of the vicious cycle of “powerlessness—cunning deception—distrust.”

Figure 14: A still from the film A Hero (Qahramān), directed by Asghar Farhādī, 2021.

A Hero begins with the release of Rahīm (Amīr Jadīdī) from prison, where he had been incarcerated due to a debt owed to his former brother-in-law, Bahrām (Muhsin Tanābandah). Rahīm has secretly befriended a woman named Farkhundah (Sahar Guldūst), who is his son’s speech therapist, and plans to marry her after his release. Farkhundah finds seventeen gold coins on the street, and the two decide to sell them and use part of the money to pay Rahīm’s debt to Bahrām. Rahīm seeks temporary leave from prison and asks his brother-in-law Husayn (‛Alīrizā Jahāndīdah) to act as an intermediary with Bahrām.

Bahrām, however, tells Husayn that he cannot trust Rahīm, believing that Rahīm has previously used cunning to deceive him and that he himself has suffered greatly from his own naïve trust. He says: “I got fooled once by his apparently innocent act and pleading look—never again.”28A Hero, directed by Asghar Farhādī (Iran, 2021), 00:13:29. Then, Husayn asks Bahrām to show lutf (favor or kindness)—a behavior typically extended by superiors to subordinates within the social hierarchy. Bahrām’s response marks the beginning of a process in which Rahīm’s actions are continuously interpreted and judged throughout the film: “He hasn’t even shown mercy to his own wife and child, so he doesn’t deserve lutf.”29A Hero, directed by Asghar Farhādī (Iran, 2021), 00:13:17. For reasons not explained in the film, Rahīm is divorced and has a son, Siyāvash (Sālah Karīmāyī), who has a speech disorder and lives with Rahīm’s sister Malīhah (Maryam Shāhdā‛ī) and her family. From Bahrām’s perspective—which seems understandable and acceptable to others—Rahīm’s inability to maintain a successful marriage suggests that he is also likely to fail professionally and be unable to repay his debt.

Figure 15: A still from the film A Hero (Qahramān), directed by Asghar Farhādī, 2021.

Figure 15: A still from the film A Hero (Qahramān), directed by Asghar Farhādī, 2021.

A Hero begins in a climate of suspense and distrust. This tension escalates when Rahīm and Farkhundah go to a jeweler to sell the coins and discover that coin prices have dropped, preventing them from raising the full amount promised to Bahrām. Farkhundah asks the jeweler if the coins might regain their previous value, and he replies, “Anything is possible.” The worried expressions on Rahīm and Farkhundah’s faces as they leave the shop reveal their doubts about whether their plan will succeed. Bahrām agrees to accept part of the debt only if Husayn provides a guarantee check, but Malīhah objects to issuing the check.

A Hero presents the unpredictable reality of contemporary Iranian life, with its painful sense of insecurity and distrust, which even infiltrates sibling relationships. That night, Malīhah finds the coins in Rahīm’s bag and anxiously tells him: “I hope you haven’t done anything to bring shame upon yourself or your family, so that we can still hold our heads high in the city.”30A Hero, directed by Asghar Farhādī (Iran, 2021), 00:18:44. Her fear is not that her brother has stolen, but that his actions could bring shame; as Beeman notes31William O. Beeman, Language, Status, and Power in Iran (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1986), 115., an individual’s behavior influences how their relatives are socially judged.

Figure 16: A still from the film A Hero (Qahramān), directed by Asghar Farhādī, 2021.

The next day, Rahīm tells Farkhundah that he does not want to sell coins that aren’t his to pay off his debt, explaining the reasons behind his decision: “Just imagine yourself in the place of that poor man who lost his bag.”32A Hero, directed by Asghar Farhādī (Iran, 2021), 00:23:15. In this scene, Rahīm encourages Farkhundah to exercise empathy and compassion toward a stranger within an unpredictable and untrustworthy social context. From an ethnographic perspective, this decision represents the initial moment in which the fragility of the film’s distrust-inducing social order is revealed. Although the decision appears to have collective approval, Farhādī’s direction highlights it as a key moment that exposes the hidden complexities of Iranian culture and the tragic transformation of a hero into an anti-hero under the pressures of moral perfectionism.

The first signs of admiration for Rahīm appear when he goes to a bank near where the bag was found, asks the staff to contact him in prison if the coins’ owner comes forward, and provides them with his prison phone number. The second sign of admiration comes from Mr. Tāhirī, the prison’s cultural deputy. A woman claiming to own the coins calls the prison. After hearing Rahīm speak on the phone, Tāhirī learns what he has done and informs the prison warden. Because Rahīm had not told anyone in the prison about the incident, others are encouraged to support his noble act. From their perspective, keeping a good deed secret is an important standard, as it reassures people that the action was neither selfish nor premeditated. This contrasts with hypocritical behavior, in which a person waits for an opportunity to reveal their actions to gain praise from others. Farhādī here highlights an important cultural issue: The fewer people who know about a good act, the less it is evaluated within the social sphere, and the smaller its social impact. Conversely, a public good deed, while more effective at creating social change, invites judgment from a wider range of people across different social backgrounds, and any deviation from moral perfection is scrutinized with greater precision and severity.

Figure 17: A still from the film A Hero (Qahramān), directed by Asghar Farhādī, 2021.

Tāhirī quickly asked others to prepare a report on Rahīm and publicize it on television and in newspapers. As a result, an act that had previously been judged by only a few people rapidly came under widespread public scrutiny, expanding to overwhelming proportions through digital media. The striking shift in societal judgment is evident in the reactions of Rahīm’s fellow inmates after watching his interview on television. Some deeply admired him and even decided to help pay his debt, while one prisoner sneered: “Well, you fooled everyone.” In his view, Rahīm had skillfully deceived others and, by publicizing his actions, helped the warden cover up the recent suicide of an inmate who had been protesting poor prison conditions, thereby benefiting from his collaboration.

From an ethnographic perspective, this sequence vividly illustrates the complex and unpredictable nature of social actions, as well as the cultural expectation that individuals consider the consequences of their actions. Those who believe Rahīm knowingly collaborated with the warden to cover up the suicide judge him as a “dishonorable trickster,” while those who believe he was unaware of the suicide and its media consequences call him “naïve and foolish.” Thus, A Hero repeatedly portrays the everyday, exhausting struggle of Iranians to escape the binary of “naïve/duped” versus “cunning/deceptive” and their desire to be recognized simply as good people—not as heroes or anti-heroes.

Figure 18: A still from the film A Hero (Qahramān), directed by Asghar Farhādī, 2021.

In a society constantly under scrutiny, individuals must carefully conceal their undesirable traits to avoid giving critics any reason for doubt. A Hero illustrates this cultural awareness through the seemingly well-meaning advice given to Rahīm about altering the truth, as well as his appearance and behavior. Tāhirī advises him to dress appropriately for the camera, shave, and avoid mentioning in the TV interview that his girlfriend, rather than he, found the bag. The cameraman instructs him to conceal the fact that he borrowed money from a loan shark and instead claim he took a bank loan, while Malīhah tells him not to smoke in front of others because it is “no longer good” for him. Rahīm, who receives attention and encouragement precisely because he has defied the established order, becomes obedient and receptive under the intoxicating pleasure of social approval, embracing all advice about secrecy and concealing the truth.

However, despite his obedient compliance, Rahīm soon succumbs to society’s moral perfectionism and its insatiable desire to replace the “real Rahīm” with a more believable “heroic Rahīm.” Unlike the fabricated heroic version, the real Rahīm has vulnerabilities, and exposing any of them only deepens collective distrust. The tension escalates to the point where even the prison warden begins to doubt Rahīm. This is the same warden who had previously exploited Rahīm to conceal his own corruption and whose initial doubts about Rahīm’s honesty stemmed from fears of collusion. Now, he suspects that Rahīm, by providing his prison number to help identify the bag’s owner, may have cleverly engineered a way to subtly showcase his actions and hypocritically gain the admiration and praise of others.

In his film, Farhādī portrays the prison as a microcosm of society, showing that in this distrustful and unhealthy cultural environment, everyone—even the warden—is trapped in the suffocating binary of being either “duped and naïve” or “deceptive and cunning.” Farhādī takes the audience, along with his characters, deep into the dark and unsettling world of the prison. However, instead of abandoning them in that humiliating and shameful darkness, he opens a window onto the possibility and importance of facing social expectations responsibly and consciously. In doing so, he breaks free from the “obsessive cycle of character-driven genre”33Ibrāhīm Tawfīq, Sayyid Mahdī Yūsifī, Hisām Turkamān, and Ārash Haydarī, Bar’āmadan-i zhānr-i khulqiyyāt dar Īrān (The Emergence of the Folk Characteristics Genre in Iran) (Tehran: Pazhūhishgāh‑i Farhang, Hunar va Irtibātāt, 2019), 298. and the “colonially induced self-deprecation” that tries to enforce change by shaming people and highlighting the gap between Iranians and the idealized “Other.” He thus moves toward a path of “non-colonial self-critique.”

After learning of Rahīm’s decision, the prison warden granted him ten days of commendatory leave. During this period, amid the turbulence of social tests of honesty, Rahīm experienced both the dignity of being a hero and the humiliation of being perceived as an anti-hero. On the final night of Rahīm’s temporary release from prison, Tāhirī visited him and asked him to make a video statement. In the video, Rahīm would claim that he personally requested the charity to use the money collected for his own release to help save a father from being executed. He would also assert that any delay or failure in using this money to secure his release was not related to rumors that the story about him and the charity had been fabricated.

However, Rahīm, at the end of the film, unlike the Rahīm at the beginning, firmly refuses, saying that since he did not do this, he will not make such a video online just so “people take his side again.” Disappointed with Rahīm, Tāhirī turns to his young son, Siyāvash, and asks him, despite his stammer, to talk about how sad he is that his father is going back to prison—so that anyone watching his grief “feels bad” and things tip back in Rahīm’s favor. In this scene, Farhādī brilliantly shows that stammering, along with Iranians’ difficulty in expressing their thoughts and decisions clearly and decisively, creates the very fertile ground in which authoritarian selfishness takes root.

At the end of the film, however, Rahīm stands firm and speaks without stammering before Tāhirī, saying: “I don’t want anyone to see my son like this.” Rahīm’s clear expression inevitably forces Tāhirī to step out from behind the mask of hypocritical benevolence and reveal his self-interest. He says to Rahīm: “Is it just your wish? Our reputation and honor are at stake.” Rahīm goes even further, and with unexpected courage exposes the selfish perspective embedded in society’s stammering, saying: “You want to buy your reputation and honor with my child’s stammer?” Tāhirī deletes the video but, in a threatening tone, says to Rahīm: “I’ll see you tomorrow.”34A Hero, directed by Asghar Farhādī (Iran, 2021), 01:58:15.

Rahīm must return to prison the next day, behind those tall walls where Tāhirī has the power to do whatever he wishes with him. Rahīm’s sister and brother-in-law are unsettled by the threat, but Rahīm possesses the calm of someone who has spoken clearly, chosen his actions without fear, and is ready to take responsibility for those choices. His young son, Siyāvash, watches his father with an admiring and worried gaze, seeing a man freed from fear and from the fleeting praise of an unpredictable, untrustworthy society. It is night, and the quiet sound of crying comes from the house. Everyone knows that Rahīm will pay dearly for this defiance.

The next day, Rahīm returns to prison. Sitting at the threshold of the long, dark corridor, waiting for permission to enter, he is neither hero nor dishonorable—he is simply Rahīm. Discovering this Rahīm through the journey from prison to society and back is a remarkable achievement, allowing him both to be brave and afraid, to make choices and to accept responsibility for them. In this sense, Rahīm serves as a successful example of challenging shameful self-deprecation and fostering constructive, non-colonial self-critique.

Leila’s Brothers

An old man, dressed in black and disheveled, sits in a worn-out house, smoking as he sinks into troubling thoughts and imagination. Gradually, the scene fills with the deafening noise of a busy factory. Security forces violently enter the factory and force the workers to leave quickly, without demanding their unpaid wages. ‛Alīrizā (Navīd Muhammadzādah) is in a corner of the hall, wearing large headphones and completely absorbed in his work. He hears neither the threats of the security forces nor the workers’ protests. An officer roughly yanks the headphones off his ears and shouts, “Are you deaf? The factory is closed!” For a few moments, ‛Alirizā stares at him, dazed and confused. Then, terrified, he runs away as fast as he can. While fleeing—through angry workers, shattered glass, fire, and batons—one of his coworkers says to him, “A shameless coward is someone who drops everything and leaves because he feels comfortable knowing his miserable friends will stay here and fight to get their wages.”35Leila’s Brothers, directed by Sa‛īd Rūstā’ī (Iran, 2022), 00:10:40. But ‛Alīrizā keeps running, as if he never heard the words.

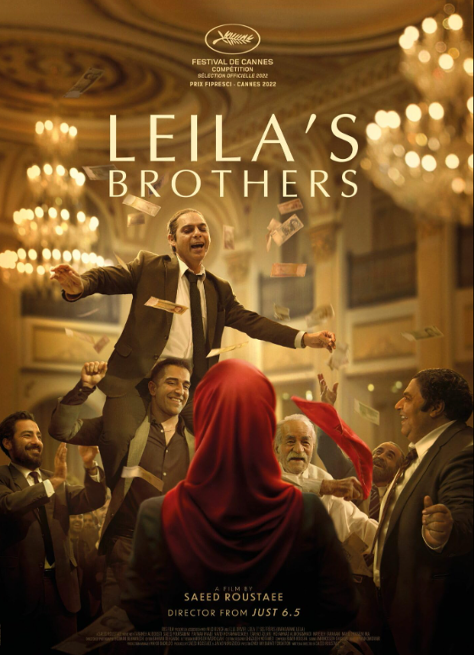

Figure 19: Poster for the film Leila’s Brothers (Barādarān-i Laylā), directed by Sa‛īd Rūstā’ī, 2022.

When Sa‛īd Rūstā’ī finished making Leila’s Brothers (2022), he screened the film at the 2022 Cannes Film Festival without waiting for an official screening permit in Iran. After that, not only was the film banned in Iran and denied a release permit to this day, but a legal case was also opened against Rūstā’ī, and he was ultimately convicted.

At first glance, Leila’s Brothers can be considered one of many intellectual works produced within the framework of the “powerful discourse of Iranian despotism,” aimed at explaining and condemning it. In this view, the mutual influence between Iranian dispositions (a character inclined to accept despotism) and despotism itself (as a label for all the crises of the present moment) forms a regressive process that traps Iranians in stagnation and an inescapable continuity. From any angle or point in time, one sees nothing but the repeated cycle of despotism–revolt–despotism.36Ibrāhīm Tawfīq, Sayyid Mahdī Yūsifī, Hisām Turkamān, and Ārash Haydarī, Bar’āmadan-i zhānr-i khulqiyyāt dar Īrān (The Emergence of the Folk Characteristics Genre in Iran) (Tehran: Pazhūhishgāh‑i Farhang, Hunar va Irtibātāt, 2019), 296.

Figure 20: A still from the film Leila’s Brothers (Barādarān-i Laylā), directed by Sa‛īd Rūstā’ī, 2022.

While addressing the issue of despotism, Rūstāʾī skillfully manages to free his film from the powerful confines of clichéd repetition. By showing the logic and mechanisms through which despotic order is reproduced in the everyday lives of Iranians, he reminds us of the possibility of resisting this order and challenging it. From this perspective, Leila’s Brothers is a successful example of refusing futile self-contempt and strengthening constructive self-criticism.

In this film, Rūstāʾī, through the allegorical narrative of the family life of a poor, tyrannical, and delusional old man named Ismāʿīl Jūrāblū (Saʿīd Pūrsamīmī), depicts the complex condition of the individual caught in the grip of “his own personality and psychological traits,” “the pressure of despotism,” and “the plunder of colonialism.” He also portrays the undeniable entanglement of all three in producing Iran’s present condition.

“The Jūrāblū clan” functions as Ismāʿīl’s idealized yet humiliating Other. His obsession with gaining their approval and being accepted into their complex network of power and wealth leaves him no room to attend to the interests and well-being of his own family. He gives the land he inherited from his father—land that could have become capital for his children to build a better life—to the head of the clan as a gift. To please the latter, he becomes addicted to opium, and, in the hope that one of the Jūrāblūs will propose marriage to his daughter, he deceitfully prevents her from marrying the young man she loves.

This same humble and submissive Ismāʿīl, deferential before the head of the Jūrāblū clan, becomes a harsh and calculating father toward his own family, willing to take his children to court on various pretexts. In a key scene of the film, when Ismāʿīl discovers that his eldest son has disobeyed his order to name the newborn after the recently deceased head of the Jūrāblū clan, he humiliates him and his family by throwing them out of the house and publicly searching Parvīz’s pockets to show everyone that he has stolen two eggs and a sausage from his parental home.

Figure 21: A still from the film Leila’s Brothers (Barādarān-i Laylā), directed by Sa‛īd Rūstā’ī, 2022.

Ismāʿīl’s poor decisions directly affect his children’s quality of life, but Rūstāʾī explains to the audience that each of them, according to their personality and psychological traits, has responded differently to the undesirable situation their father has created. However, none of their behavioral choices are aimed at weakening their father or changing the despotic relationship. Parvīz (Farhād Aslānī) turns to alcohol; Manūchihr (Payman Ma‛ādī) tries to build a comfortable life for himself through fraud; Farhād (Muhammad ‛Alī Muhammadī) spends all his time on sports and bodybuilding. These three have accepted the family’s adverse situation and neither try to improve it nor change it—they only attempt to minimize the costs of being trapped in it for themselves.

‛Alīrizā, like the others, has accepted the undesirable situation and has no motivation to change it. The difference is that, guided by individualist ethics, he feels obliged to keep a deliberate distance from his family while treating everyone kindly and respectfully, constantly reminding himself and others to respect the rights of others—from turning off running water to encouraging men’s participation in household chores. ‛Alīrizā firmly believes that one must respect the choices of others, even if those choices harm him, the family, or themselves, and he reproachfully says, “We’re a bunch of cows who never learned not to interfere in each other’s lives.”37Leila’s Brothers, directed by Sa‛īd Rūstā’ī (Iran, 2022), 00:49:18. He supports his father and all of his father’s poor decisions under the principle of “it’s his right,” while insisting on keeping his distance because he finds the family’s “angry outbursts” and “chaotic behavior” stressful. He works in a distant city and sends money to his family, thereby, in his view, both improving their situation through financial and psychological support and reducing the personal costs of being part of this family.

Figure 22: A still from the film Leila’s Brothers (Barādarān-i Laylā), directed by Sa‛īd Rūstā’ī, 2022.

Laylā (Tarānah ‛Alīdūstī), however, makes a very different choice: she pays no attention to protecting herself and devotes herself entirely to her family, particularly to improving the lives of her brothers. She hates her father and mother and wishes they would die, yet she is the one who takes care of them, providing their medication. Without Laylā’s care and self-sacrifice, the family would long since have collapsed under the combined weight of the father’s incompetence and cruelty and the indifference of the other members. She not only refuses to distance herself from the family but insists that others also accept their shared fate. When ‛Alīrizā says of the family, “They’ve been stuck in the same place for years,” Laylā corrects him: “Don’t say ‘they’; say ‘we.’ We’ve been stuck in the same place.”38Leila’s Brothers, directed by Sa‛īd Rūstā’ī (Iran, 2022), 00:28:15.

Laylā is wise and compassionate, and she seeks a practical solution to change their situation, eventually arriving at a clear and reasonable proposal: If all the children pool their resources, they could pre-purchase a shop in a thriving mall and change their lives. She succeeds in persuading her brothers to agree to this risky collective plan. Ismāʿīl’s children, caught between despair and hope, are busy gathering the initial capital for the shop when Bāyrām, Ismāʿīl’s cousin’s son (Mahdī Husaynīniyā), tells him that his father has stipulated in his will that, after him, Ismāʿīl may become head of the clan—provided he can give 40 gold coins as a wedding gift at Bāyrām’s son’s wedding.

Ismāʿīl, whose greatest aspiration is to gain the attention and respect of the Jūrāblūs, gratefully accepts the proposal. His children realize that their father has the financial means to pay the 40 gold coins—the exact amount they need to purchase the shop—but he chooses instead to spend the money to win the temporary, self-interested approval and respect of the Jūrāblūs (his idealized Other) rather than to build a dignified life for his own family (his true Self).

The children’s arguments and opposition cause the old man to suffer a stroke. Fearing his father’s death and guided by the ethical principle that everyone has the right to decide over their own property, ‛Alīrizā defends him against the other children. As a result, Ismāʿīl is able to attend the Jūrāblū wedding as head of the clan. However, when it comes time to present the gold coins as a gift, it is revealed that Laylā has sold them, and Ismāʿīl is humiliatingly stripped of his position.

Figure 23: A still from the film Leila’s Brothers (Barādarān-i Laylā), directed by Sa‛īd Rūstā’ī, 2022.

Unlike ‛Alīrizā, Laylā interprets her father’s decision through the lens of his responsibilities to others and the “ethics of care,”39Carol Gilligan, In a Different Voice: Psychological Theory and Women’s Development (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1982), 23-64. and so sees no reason to respect it. From her perspective, the coins are not her father’s personal property but “the children’s rightful share.” Laylā’s courage in resisting her father’s demands made it possible for them to purchase the shop. Yet, just as her efforts were bearing fruit, and despite having invested all her savings and assets in the purchase alongside her brothers, she refused to have her name listed as a partner on the title. In doing so, she voluntarily gave up her legal right to participate in future decisions regarding the shop.

Rūstāʾī depicts a subtle cultural logic here, one that can be understood through an ethnographic lens. Laylā had managed to overcome her fear of her father, yet years of living under a patriarchal system—repeatedly emphasized throughout the film—had deeply instilled in her the belief that women should prioritize caring for others over their own needs. This made it impossible for her both to assert herself and to fully claim her brothers’ rights. She was devoted to them and challenging this deeply ingrained belief required a level of courage and boldness far greater than that needed to stand up to her father.

The father stubbornly demands that his sons sell the shop and return his coins. After he suffers another stroke, the brothers gather at ‛Alīrizā’s invitation to decide what to do about selling the shop. Laylā enters without being invited. This intense scene reveals the hidden mechanisms and coordination that, from an ethnographic perspective, each member of a society employs—following unwritten agreements—to reproduce habitual order and preserve the status quo. Each brother offers a justification for supporting the sale of the shop, and within the framework of this habitual order, their reasoning appears self-evident. Laylā, however, questions each brother’s reasoning, challenging what they take for granted and surprising the audience. ‛Alīrizā says, “We have to give him back the coins. He won’t stop. He’ll keep going until he dies,” to which Laylā simply responds, “Then let him die.” Parvīz adds, “This shop carries the weight of father’s sighs; his curse won’t let it succeed,” and Laylā just gives him a knowing look, as if what he said makes no sense.

Figure 24: A still from the film Leila’s Brothers (Barādarān-i Laylā), directed by Sa‛īd Rūstā’ī, 2022.

In this scene, Rūstāʾī boldly transforms the symbolic certainty of the father’s authority—from a sacred, unquestionable status—to something contestable. This boundary-breaking reaches its peak when Laylā, in a revealing act, exposes her father’s lies and slaps him in front of her brothers. Rūstāʾī touches on a sensitive point—not only in Iranian culture but in the broader human cultural framework—and much of the discussion and controversy surrounding his film in Iran arose in response to this transgressive confrontation with the father figure. For example, the Iranian film critic Mas‛ūd Farāsatī, in a long-running series of debates, described Leila’s Brothers as “anti-family” and, in particular, “anti-father.”40Masʿūd Farāsatī, “Barādarān-i Laylā yak fīlm-i ziddah khānavādah va siyāh ast,” Fararu, December 16, 2025, https://fararu.com/fa/news/621685.

Rūstāʾī does not tell the audience that the brothers had no choice but to sell the shop and return their father’s money; rather, he shows that they selected this path from among other possible options. Similarly, Laylā, exercising her own agency, refused to have her name added to the shop’s title and, in response to her brothers’ decision, could only warn them: “You’ve started your eternal misery tonight yourselves.”41Leila’s Brothers, directed by Sa‛īd Rūstā’ī (Iran, 2022), 02:01:39.

From an ethnographic perspective, the remainder of the film constitutes a sophisticated depiction of the ways in which individuals, through their everyday life choices, generate social order while simultaneously being shaped by the actions of others, both near and distant. Within this framework, the reciprocal influence between agents and the structure of social life—with its own particular characteristics—becomes observable and analytically tractable.

At the same time that the brothers were deciding whether to sell the shop, policymakers in Iran and the United States were making decisions regarding international relations. The sale of the shop coincided with rising tensions between Iran and the United States, and after a single tweet from President Donald Trump, the Iranian currency devalued so dramatically that the brothers lost not only their father’s coins but all of their assets, leaving them in a far worse situation than before. The father asked in bewilderment, “Trump tweeted—does that mean he dropped a bomb?” ‛Alīrizā replied, “No, but even if he had, it still shouldn’t have gotten this bad.”42Leila’s Brothers, directed by Sa‛īd Rūstā’ī (Iran, 2022), 02:05:50.

Amid this profound setback, ‛Alīrizā reflected on himself and realized that his show of morality had been hiding his deep fear of making choices and taking responsibility for them. He returned to the factory, and when told he had to sign a form to receive three months’ wages as if it were for a full year, he refused to stand passively in line and shouted: “I want all my rights, in proportion to the work I’ve done!”43Leila’s Brothers, directed by Sa‛īd Rūstā’ī (Iran, 2022), 02:22:30. and defiantly broke the glass of the personnel office—a glass that had been previously shattered by another protesting worker and only recently repaired. Rūstāʾī, like Kiyānūsh ‛Ayyārī, emphasizes that real change doesn’t happen all at once—it emerges from repeated small acts that challenge established rules and norms. By continually breaking these norms, even in minor ways, the cumulative effect gradually weakens the fear and control that maintain the old order.

Conclusion

This article seeks to understand the role of Iranian social cinema in gradually transforming society’s self-deprecating mindset and in fostering what Abedinifard terms “decolonizing collective self-criticism.” Building on Tawfīq’s idea that Iranian society, after each failed attempt at idealistic reform, is flooded with reminders of its negative traits, this study focuses on the thirteen years between the Green Movement and the Women, Life, Liberty Movement. This period, marked by repeated uprisings and accumulated reformist experiences, provides a rich context for analyzing the cultural and semantic dimensions of social transformation.

Given that many analyses have characterized the 2022 movement as “a movement against humiliation,” the central question was how, within a historical context shaped over more than a century by patterns of “idealized othering of the West” and “shaming self-criticism,” the cultural and semantic conditions for such a movement emerged, and what role cinema played in this process. Accordingly, this study examines how cinema, as an active social force in the public sphere, has contributed to collective transformation and the reconfiguration of a self-deprecating mindset.

Focusing on social cinema and applying criteria such as directorial authorship, international recognition, capacity to spark public dialogue, and potential to influence critical discourse, four films—Tales, Sofa, A Hero, and Leila’s Brothers—were purposefully selected and analyzed using an ethnographic theoretical-methodological approach combined with content analysis. The ethnographic perspective, which emphasizes everyday actions and moments of reproduction or disruption of social order, provides an effective lens for understanding how negative traits are represented and potentially transformed in these films.

The analysis shows that, unlike the dominant tradition of portraying negative traits—which for decades reinforced feelings of helplessness, shame, and self-deprecation in relation to an idealized Other—these films present a more hopeful and nuanced perspective. Four recurring issues—failure to communicate, reputation anxiety, moral perfectionism, and authoritarianism—are depicted not as immutable characteristics but as fragile and changeable social norms. This shift is significant, as it moves the focus from “fixed traits” to “changeable norms,” highlighting the potential for individual and collective agency and recognizing cultural dynamism.

In all four films, the narratives emphasize moments of rupture, disobedience, creativity, and transgression—small, costly, yet meaningful acts that reveal social order as historically contingent, conventional, and fragile. These depictions encourage “constructive self-criticism,” a form of reflection that, instead of reproducing humiliation, highlights individual and collective responsibility to change inhumane behaviors and promote humanizing actions.

In sum, cinema functions not as a passive mirror but as an active force in reshaping society’s self-understanding. By showing that norms can change, emphasizing moments of individual and collective agency, and avoiding a shaming gaze toward the self in relation to the idealized Other, these films help create the cultural conditions for a shift from self-deprecation to “decolonizing collective self-criticism.” Over the past thirteen years, Iranian social cinema has thus played an influential role in shaping the collective imagination in preparation for a movement that challenged humiliation.

Finally, it should be noted that the study is limited by examining only four films, whereas Iranian cinema during this period clearly offered a broader and more diverse set of relevant examples. Moreover, cultural analysis alone cannot account for all social and political mechanisms. Future research could investigate the roles of social media, literature, music, and everyday narratives in shaping semantic transformations within Iranian society. Comparative studies of films produced after the 2022 movement with those from earlier periods could shed light on whether the observed trends have deepened constructive self-criticism or require further reassessment.

Cite this article

Influenced by Mostafa Abedinifard’s “Iran’s ‘Self-Deprecating Modernity’: Toward Decolonizing Collective Self-Critique,” this article examines the role of Iranian social cinema in reshaping this perspective and reinforcing what Abedinifard terms “decolonizing self-criticism.” Given that the 2022 “Women, Life, Liberty” movement emerged from a shift in Iranian perceptions of self-deprecation, as well as from the gradual efforts of diverse social forces, this study examines how social cinema—both as a cultural and social force—has contributed to reshaping critical self-deprecation in contemporary Iran. For this purpose, the article analyzes four films—Tales (Qissah’hā, 2011), Sofa (Kānāpah, 2016), A Hero (Qahramān, 2021), and Leila’s Brothers (Barādarān-i Laylā, 2022)— produced during the thirteen-year period between the Green Movement and the Women, Life, Liberty Movement. Focusing on themes of agency and transformation, this study examines these films using an ethnographic content analysis method. The analysis shows that four negative traits often linked to Iranians—trouble having meaningful conversations, fear of losing face, moral perfectionism, and supporting autocracy—are shown in these films as changeable and fragile, not fixed and natural. It can be argued that social cinema during this period played a significant role in strengthening the decolonization of collective self-criticism, a process that helped shape the cultural and psychological conditions enabling the 2022 movement to emerge as a “movement against humiliation.”

Keywords:

Modernity; Self-deprecation; Colonialism; Women, Life, Liberty Movement; Iranian Social behaviors.